Abstract

Background

Enteric outbreak investigation in Canada is performed at the local, provincial/territorial (P/T) and federal levels. Historically, routine surveillance of outbreaks did not occur in all jurisdictions and so the Public Health Agency of Canada, in partnership with P/T public health authorities, developed a secure, web-based Outbreak Summaries (OS) Reporting System to address this gap.

Objective

This analysis summarizes the foodborne outbreak investigations reported to the OS Reporting System between 2008 and 2014.

Methods

Finalised reports of investigations between 2008 and 2014 for all participating jurisdictions in Canada were extracted and descriptive analysis was carried out for foodborne outbreaks on etiological agent, severity of illness, outbreak duration, exposure setting and outbreak source.

Results

There were 115 reported foodborne outbreaks included in the analysis. This represents 11.2% of all outbreaks reported in the enteric module of the OS Reporting System between 2008 and 2014. Salmonella was the most commonly reported cause of foodborne outbreak (40.9%) and Enteritidis was the most common serotype reported. Foodborne outbreaks accounted for 3,301 illnesses, 225 hospitalizations and 30 deaths. Overall, 38.3% of foodborne outbreaks were reported to have occurred in a community and 32.2% were associated with a food service establishment. Most foodborne outbreak investigations (63.5%) reported a specific food associated with the outbreak, most frequently meat.

Conclusion

The OS Reporting System supports information sharing and collaboration among Canadian public health partners and offers an opportunity to obtain a national picture of foodborne outbreaks. This analysis has demonstrated the utility of the OS Reporting System data as an important and useful source of information to describe foodborne outbreak investigations in Canada.

Introduction

It is estimated that approximatively four million episodes of domestically acquired foodborne illness occur every year in Canada (1). Some of these illnesses will lead to hospitalizations and death. Recent estimates indicate that there are 11,600 hospitalizations and 238 deaths associated with domestically acquired foodborne illness every year in Canada (2). There are many reasons to investigate foodborne outbreak illness, in particular to identify and eliminate the source and prevent additional cases. Furthermore, results of an investigation may lead to recommendations for preventing future outbreaks (3).

Enteric outbreak investigation in Canada is performed at the local, provincial/territorial (P/T) and federal levels. In the past, routine surveillance of outbreaks did not occur in many Canadian jurisdictions and so, in response to this identified information gap and the recognized need for a Canadian outbreak surveillance system, the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) partnered with P/T public health authorities in 2008 to implement the Outbreak Summaries (OS) Reporting System.

The OS Reporting System was designed as a national surveillance tool and all of its data is accessible to participating jurisdictions. Local, provincial/territorial and federal users can query and summarize data and generate reports on the results of any outbreak investigation that has been reported through the OS Reporting System. Information can be used to inform current outbreak investigations by providing historical information about outbreaks of certain pathogens to help generate potential hypotheses as to the etiology of current outbreaks, thus informing public health interventions. The Reporting System also supports information sharing and collaboration among a variety of Canadian public health partners.

The objective of this report is to summarize the foodborne outbreak investigations carried out by participating provinces between 2008 and 2014.

Methods

Data sources

The OS Reporting System is a secure, web-based application that can be used by local, P/T and federal public health professionals to summarize and share the results of outbreak investigations in a standard format. The Canadian Network for Public Health Intelligence (CNPHI) provides the platform on which the OS Reporting System resides. The system currently has two modules: one for enteric, foodborne and waterborne diseases and one for respiratory and vaccine-preventable diseases. Currently, six provinces (British Columbia, Manitoba, Ontario, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland and Labrador) and the Centre for Food-borne, Environmental and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases (CFEZID) at PHAC have progressively implemented the enteric module of the OS Reporting System and routinely report outbreaks. Each participating jurisdiction inputs data into the OS Reporting System and each province has its own guidelines for outbreak reporting. PHAC reports multijurisdictional outbreaks led by the Agency.

Finalised reports for investigations between 2008 and 2014 for all participating jurisdictions in Canada were extracted on May 7, 2015 from the enteric, foodborne and waterborne diseases module in the OS Reporting System.

Data analysis

This report provides descriptive analysis of the etiological agent, severity of illness, outbreak duration, outbreak source and exposure setting. Community and institutional outbreaks were defined as per the text box below.

| Definition of community and institutional outbreak for the Outbreak Summary Reporting System |

|---|

|

Community outbreak: two or more unrelated cases with similar illness that can be epidemiologically linked to one another (i.e., associated by time and/or place and/or exposure). Institutional outbreak: three or more cases with similar illness that can be epidemiologically linked to one another (i.e., associated by exposure, within a four-day period in an institutional setting). |

Data were reviewed for inconsistencies and redundancies prior to analysis. Clostridium difficile and vancomycin resistant Enterococcus (VRE) outbreaks were not analyzed as they are usually healthcare-associated infections and are typically managed quite differently than enteric outbreaks. Duplicate summaries where two (or more) different jurisdictional levels (e.g., PHAC and a province; a province and a health unit [HU] or Regional Health Authority [RHA]) reported on a jointly investigated outbreak were also removed from the analysis. In these cases, the report from the lead jurisdiction was retained for analysis and the other report(s) were excluded.

The year of investigation used in the analysis was derived from the date the outbreak investigation began. Descriptive analysis of the location of cases, principal etiologic agents, number of laboratory-confirmed and clinical cases, severity of illness and exposure/transmission settings involved were performed. The number of cases, hospitalizations and deaths by etiologic agent was determined. Outbreak duration was also assessed and was calculated using the difference between the symptoms onset dates of the first and last case identified. Reports with missing values in either of these fields were excluded. More focused analyses of transmission settings by etiologic agent, as well as details about the sources identified in outbreaks with foodborne transmission were performed.

Analyses were carried out using Microsoft Excel 2010.

Results

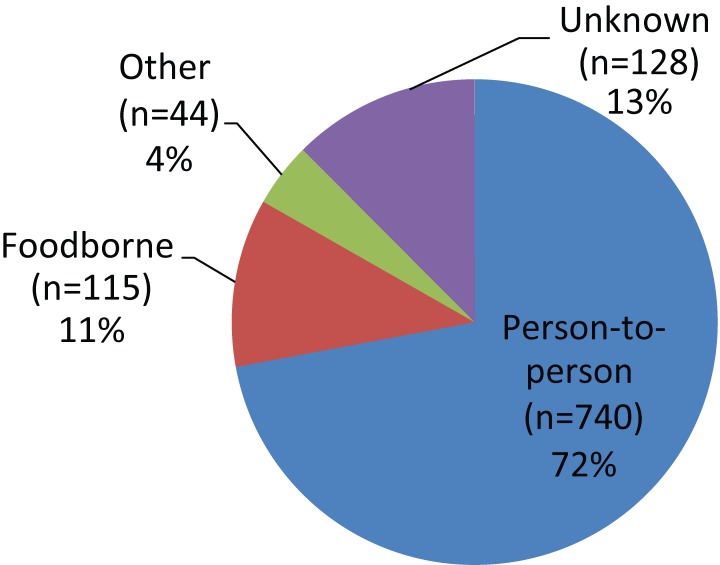

There were 1,027 outbreaks entered into the OS Reporting System between 2008 and 2014. Of these, 115 were outbreaks related to a food source and were included in this analysis (Figure 1). These foodborne outbreaks represent 11.2% of all outbreaks reported in the OS Reporting System between 2008 and 2014, making them the second most common mode of transmission for enteric outbreaks reported, after person-to-person transmission. Other modes of transmission included environment-to-person, animal-to-person, waterborne and multiple modes of transmission.

Figure 1.

Proportion of outbreak investigations reported to the Outbreak Summaries Reporting System by mode of transmission, 2008-2014 (n=1,027)

Foodborne outbreaks were the most commonly reported mode of transmission for PHAC-posted summaries (37/46 or 80.4%). British Columbia (BC) reported more than half of the foodborne outbreaks in the OS Reporting System (67/115 or 58.3%).

Etiologic agents

Table 1 presents the etiologic agents attributed to foodborne outbreaks reported in the OS Reporting System. Among the 115 foodborne outbreaks reported from 2008 to 2014, 106 outbreaks (92.2%) reported an etiologic agent. The majority (73%) of outbreaks were attributed to bacterial agents and viral etiology accounted for 14.8%. The most frequently reported etiologic agents were Salmonella (40.9%), Escherichia (14.8%) and norovirus (12.2%). A serotype was reported for 46 of the 47 Salmonella outbreaks. Enteritidis was the most common serotype reported and was responsible for 22 of the 47 Salmonella outbreaks (46.8%). All reported Escherichia outbreaks were caused by E. coli O157 VTEC.

Table 1. Number of foodborne outbreak investigations reported to the Outbreak Summaries (OS) Reporting System with the total number of cases by etiologic agent, 2008-2014 (n=115).

| Etiologic agent |

Outbreaks n (%) |

Total cases n (%) |

Cases | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lab-confirmed n (%) | Clinical n (%) | |||

| Bacterium | 84 (73) | 2,588 (78.4) | 2,076 (91.8) | 512 (49.2) |

| Salmonella | 47 (40.9) | 2,041 (61.8) | 1,776 (78.5) | 265 (25.5) |

| Escherichia | 17 (14.8) | 201 (6.1) | 199 (8.8) | 2 (0.2) |

| Clostridium botulinum | 3 (2.6) | 3 (0.1) | 3 (0.1) | - |

| Clostridium perfringens | 3 (2.6) | 111 (3.4) | 0 (0) | 111 (10.7) |

| Listeria | 3 (2.6) | 67 (2) | 67 (3) | - |

| Campylobacter | 2 (1.7) | 40 (1.2) | 16 (0.7) | 24 (2.3) |

| Staphylococcus | 2 (1.7) | 23 (0.7) | 2 (0.1) | 21 (2) |

| Bacillus | 2 (1.7) | 24 (0.7) | - | 24 (2.3) |

| Shigella | 1 (0.9) | 14 (0.4) | 9 (0.4) | 5 (0.5) |

| Cronobacter | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | - |

| Other | 1 (0.9) | 16 (0.5) | 3 (0.1) | 13 (1.3) |

| Unknown | 2 (1.7) | 47 (1.4) | - | 47 (4.5) |

| Virus | 17 (14.8) | 422 (12.8) | 52 (2.3) | 370 (35.6) |

| Norovirus | 14 (12.2) | 352 (10.7) | 25 (1.1) | 327 (31.4) |

| Hepatitis A | 2 (1.7) | 27 (0.8) | 27 (1.2) | - |

| Unknown | 1 (0.9) | 43 (1.3) | - | 43 (4.1) |

| Toxin / chemical poison | 6 (5.2) | 88 (2.7) | 12 (0.5) | 76 (7.3) |

| Shellfish poisoning | 2 (1.7) | 66 (2) | 4 (0.2) | 62 (6) |

| Histamine poisoning | 2 (1.7) | 8 (0.2) | 8 (0.4) | - |

| Fiddlehead toxin | 1 (0.9) | 9 (0.3) | - | 9 (0.9) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.9) | 5 (0.2) | - | 5 (0.5) |

| Other | 4 (3.5) | 128 (3.9) | 121 (5.4) | 7 (0.7) |

| Cyclospora | 3 (2.6) | 121 (3.7) | 121 (5.4) | - |

| Yeast / Fungi | 1 (0.9) | 7 (0.2) | - | 7 (0.7) |

| Unknown | 4 (3.5) | 75 (2.3) | 0 (0) | 75 (7.2) |

| Grand total | 115 (100) | 3,301 (100) | 2,261 (100) | 1,040 (100) |

There were a total of 3,301 cases (2,261 lab-confirmed and 1,040 clinical) associated with the 115 foodborne outbreak investigations. The largest proportion (2,041/3,301 or 61.8%) of total cases was attributed to Salmonella infections and 87% of these cases were laboratory-confirmed. The second highest proportion (352/3,301 or 10.7%) of total cases was observed for norovirus, 92.9% of which were clinical cases.

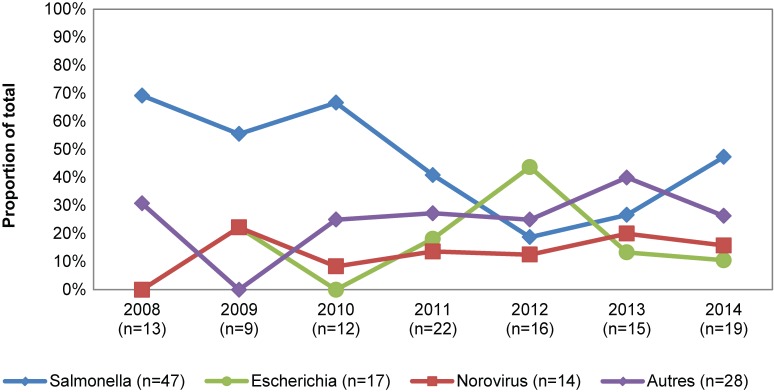

Figure 2 shows the proportion of total foodborne outbreak investigations by year for the three most frequently reported pathogens among the 106 foodborne outbreaks with an etiologic agent reported. Over the study period, the overall proportions of Salmonella outbreaks decreased sharply in 2011 and 2012 and were mainly reported by BC and PHAC. During the same period, PHAC encountered a proportional increase in E. coli-related outbreaks (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Proportion of total foodborne outbreak investigations reported to the Outbreak Summaries (OS) Reporting System by year by etiologic agents, 2008-2014 (n=106)

Severity of illness

Of the 3,301 total cases associated with foodborne outbreaks, 225 cases were hospitalized and 30 deaths were reported. The average number of cases, hospitalizations and deaths associated with each pathogen varied greatly. Known etiologic agents that caused the greatest number of cases per outbreak were Salmonella, Cyclospora, Clostridium perfringens and shellfish poisoning with an average of 43, 40, 37 and 33 cases per outbreak respectively.

Data on severity of illness, hospitalization and death is summarized in Table 2. Infections due to Salmonella and E. coli together accounted for the majority of hospitalizations (106 and 84 respectively), but the hospitalization proportion differs greatly between these two pathogens. Salmonella had an average hospitalization proportion of 12% while E.coli had an average of 41.8%. Clostridium botulinum, Listeria and histamine poisoning had the highest hospitalization proportions with 100%, 90%, and 75% respectively.

Table 2. Number of foodborne outbreaks reported to the Outbreak Summaries (OS) Reporting System with the total number of cases, hospitalizations and deaths by etiologic agent, 2008-2014 (n=115).

| Etiologic agent | Average no. cases by outbreak Avg. (range) |

Total cases n (%) |

Hosp. n (%1) |

Deaths n (%1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterium | 30.8 (1-1029) | 2,588 (78.4) | 205 (15) | 30 (1.2) |

| Salmonella | 43.4 (1-1029) | 2,041 (61.8) | 106 (12) | 4 (0.2) |

| Escherichia | 11.8 (1-30) | 201 (6.1) | 84 (41.8) | 3 (1.5) |

| Campylobacter | 20 (10-30) | 40 (1.2) | - | - |

| Clostridium botulinum | 1.0 (1-1) | 3 (0.1) | 3 (100) | 1 (50) |

| Clostridium perfringens | 37.0 (28-54) | 111 (3.4) | - | - |

| Listeria | 22.3 (5-57) | 67 (2) | 9 (90) | 22 (32.8) |

| Shigella | 14.0 (14-14) | 14 (0.4) | 2 (14.3) | - |

| Staphylococcus | 11.5 (7-16) | 23 (0.7) | 1 (4.3) | - |

| Bacillus | 12.0 (11-13) | 24 (0.7) | - | - |

| Cronobacter | 1.0 (1-1) | 1 (0) | - | - |

| Other | 16.0 (16-16) | 16 (0.5) | - | - |

| Unknown | 23.5 (4-43) | 47 (1.4) | - | - |

| Virus | 24.8 (6-99) | 422 (12.8) | 11 (2.8) | - |

| Norovirus | 25.1 (7-99) | 352 (10.7) | 1 (0.3) | - |

| Hepatitis A | 13.5 (6-21) | 27 (0.8) | 10 (47.6) | - |

| Unknown | 43.0 (43-43) | 43 (1.3) | - | - |

| Toxin / chemical poison | 14.7 (2-62) | 88 (2.7) | 7 (26.9) | - |

| Histamine poisoning | 4.0 (2-6) | 8 (0.2) | 6 (75) | - |

| Shellfish poisoning | 33.0 (4-62) | 66 (2) | 1 (25) | - |

| Fiddlehead toxin | 9.0 (9-9) | 9 (0.3) | - | - |

| Unknown | 5.0 (5-5) | 5 (0.2) | - | - |

| Other | 32.0 (7-85) | 128 (3.9) | 2 (1.6) | - |

| Cyclospora | 40.3 (11-85) | 121 (3.7) | 2 (1.7) | - |

| Yeast / Fungi | 7.0 (7-7) | 7 (0.2) | - | - |

| Unknown | 18.8 (6-41) | 75 (2.3) | - | - |

| Grand total | 28.7 (1-1029) | 3,301 (100) | 225 (11.4) | 30 (1) |

1 Data shown are the total number by etiologic agent with the proportion of total cases for respective etiologic agent in parenthesis. (Note: Outbreaks with missing data for hospitalization or death were excluded from the denominator.) The information about the number of hospitalizations is missing for 10/47 Salmonella outbreak reports; 1/14 norovirus reports and one each of the Listeria, Cronobacter, Hepatitis A and Shellfish poisoning outbreak reports. The number of deaths is missing for 8/47 Salmonella outbreak reports, 2/14 norovirus reports as well as for one each of Clostridium botulinum, Bacillus cereus and Hepatitis A outbreaks.

Listeria was the most common cause of outbreak-related deaths, accounting for 73.3% of total deaths (22/30). The case fatality ratio for Listeria was 32.8% among outbreak-related cases. All 22 Listeria-related-deaths reported in the OS Reporting System occurred during the same outbreak and involved immune-compromised and elderly individuals, most of whom were in hospitals or long term care facilities during their exposure period.

Duration

Data for symptoms onset date for both the earliest or the most recent case was available for 94 of the 115 (81.7%) foodborne outbreaks reported in the OS Reporting System. Outbreak duration ranged from less than one day to 1,689 days, with the median and mean being eight days and 52.7 days, respectively. The outbreak with 1,689 days duration was attributed to a S. Enteritidis outbreak in one province linked to eggs and was associated with 1,029 laboratory-confirmed cases.

Exposure

Overall, 44 (38.3%) foodborne outbreaks and 60.8% of total foodborne outbreak-related cases (n=2,006) were reported to have occurred in a community setting, while 37 outbreaks (32.2%) and 18.3% of total cases (n=604) were associated with a food service establishment. The etiologic agent was laboratory-confirmed in the majority of foodborne outbreaks (96/115 or 83.5%).

Table 3. Number of foodborne outbreak investigations with laboratory-confirmed etiologic agent reported to the Outbreak Summaries (OS) Reporting System by exposure/transmission setting, 2008-2014.

| Exposure/transmission setting | Number of outbreaks n (%) | Number of outbreaks with lab-confirmed etiologic agent n (%) |

Total cases n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Community | 44 (38.3) | 44 (38.3) | 2,006 (60.8) |

| Food service establishment | 37 (32.2) | 26 (22.6) | 604 (18.3) |

| Private function | 14 (12.2) | 10 (8.7) | 24 (0.7) |

| More than one setting | 5 (4.3) | 4 (3.5) | 145 (4.4) |

| Institutional - residential | 4 (3.5) | 3 (2.6) | 11 (0.3) |

| Institutional - non-residential | 4 (3.5) | 2 (1.7) | 1 (0) |

| Travel-related - outside Canada | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.9) | 33 (1) |

| Other setting | 2 (1.7) | 2 (1.7) | 411 (12.5) |

| Unknown | 4 (3.5) | 4 (3.5) | 66 (2) |

| Grand total | 115 (100) | 96 (83.5) | 3,301 (100) |

Most investigations (73/115 or 63.5%) reported a specific food associated with the outbreak (data not shown). Meat was the most commonly reported source (26%), followed by eggs (15.1%) and vegetables (13.7%). Among the 47 foodborne Salmonella outbreaks, the foods associated with the outbreak were identified in 28 outbreaks (59.6%) and were mainly eggs (39.3%) and meat (28.6%). Twelve of the17 E. coli outbreaks (70.6%) had a food source identified and these were mainly related to meat products (50%). The remaining were related to raw vegetables, nuts or seeds, dairy product and fruit. Finally, ten of the14 norovirus outbreaks were associated with a specific food item, among which seafood, fruits, vegetables and mixed or other food were identified. One norovirus outbreak identified as foodborne was associated with an ill food handler.

Table 4. Number and proportion of food items associated with the outbreak by etiologic agents, 2008-2014.

| Food items associated with the outbreak | Escherichia n (%) | Norovirus n (%) | Salmonella n (%) | Other n (%) | Unknown n (%) | Total n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meat | 6 (50) | - | 8 (28.6) | 5 (27.8) | - | 19 (26) |

| Eggs | - | - | 11 (39.3) | - | - | 11 (15.1) |

| Vegetables | 2 (16.7) | 1 (10) | 4 (14.3) | 2 (11.1) | 1 (20) | 10 (13.7) |

| Seafood | - | 3 (30) | - | 5 (27.8) | 1 (20) | 9 (12.3) |

| Fruit | 1 (8.3) | 2 (20) | 3 (10.7) | 1 (5.6) | - | 7 (9.6) |

| Nuts/Seeds | 2 (16.7) | - | 1 (3.6) | - | - | 3 (4.1) |

| Dairy products | 1 (8.3) | - | - | - | - | 1 (1.4) |

| Mixed or other | - | 4 (40) | 1 (3.6) | 5 (27.8) | 3 (60) | 13 (17.8) |

| Grand total | 12 (100) | 10 (100) | 28 (100) | 18 (100) | 5 (100) | 73 (100) |

Discussion

This is the first national report published on foodborne outbreaks using data from the OS Reporting System. One hundred fifteen (11.2%) of the enteric outbreaks reported in the OS Reporting System were foodborne outbreaks, Salmonella (40.9%), Escherichia (14.8%) and norovirus (12.2%) were the most common etiologic agents. Surveillance data from the National Enteric Surveillance Program (NESP) also reflect the importance of Salmonella as an etiologic agent of enteric illness in Canada given that Salmonella was the most common pathogen (40.3%) reported to the NESP in 2013 (4). Of note, the NESP provides a wider picture as it also includes sporadic and travel-acquired cases.

The total number of locally-acquired, sporadic foodborne illnesses in Canada has also been estimated. The five most frequent pathogens are: norovirus (65.1%), Clostridium perfringens (11%), Campylobacter spp. (8.4%), non-typhoidal Salmonella spp., (5.1%) and Bacillus cereus (2.3%) (1). It is interesting to note the differences between the top five pathogens identified in this study, and the most commonly identified pathogens in the OS Reporting System. The under diagnosis and lack of laboratory confirmation for some infections like Campylobacter and toxins, as well as under-reporting and variable investigation practices for these pathogens in Canada may explain why these pathogens are not ranked as high in the OS Reporting System. Among foodborne outbreaks in the US in 2013 with a known etiologic agent, norovirus was the most common pathogen at 44.8%, followed by Salmonella (32.3%) and STEC E. coli (3.9%) (4). The relative frequency of these pathogens among foodborne outbreaks differs from Canada, especially for norovirus. This could be explained in part by differences in reporting and investigation practices between the two countries.

The proportion of hospitalized cases of Salmonella (12%) and norovirus (0.3%) in the OS Reporting System were relatively similar to those observed in the US (17.5% and 0.7%, respectively) (5). The proportion of hospitalized cases was higher for E. coli than Salmonella both in Canada (41.8%) and US (33.3%). A comparison between case fatality data in the OS Reporting System with US data could not be made due to the small number of deaths observed. The majority of all foodborne outbreaks involved laboratory-confirmed etiologic agents; however, the ratio of lab-confirmed to clinical cases was much higher for bacterial outbreaks than for viral or toxin/chemical related outbreaks. This is likely a result of differences in symptom presentation and severity between bacterial outbreaks versus other outbreaks and the subsequent likelihood if getting tested. It may also be related to the effectiveness of viral versus bacterial testing methods in identifying a pathogen.

Most foodborne outbreaks occurred in the community or involved a food service establishment. The most commonly reported outbreak source was meat (19/73 or 16.5%) followed by eggs (11/73 or 15.1%) and vegetables (10/73 or 13.7%). Interestingly, the US reported a slightly lower proportion of outbreaks with an identified source (46%, compared to 63.5% in the OS Reporting System), with fish as the most commonly identified commodity at 23.8%, followed closely by mollusk (11%), chicken and dairy (10% each) (5).

The strength of the OS Reporting System is that it provides a source of data to monitor the occurrence of and trends in enteric, foodborne and waterborne disease outbreaks at the national level. It provides F/P/T partners with a system that allows them to collect, query and summarize outbreak information in a systematic and standardized manner. These data have been used to support hypothesis generation in outbreak investigations led by PHAC and by participating jurisdictions for their own internal reporting and outbreak investigations. Data has also informed internal reports and projects conducted within PHAC and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA).

Several limitations associated with the analyses of OS Reporting System data have been identified. Reporting criteria and timelines are set by each participating province and can vary greatly which may potentially affect data completeness. Some jurisdictions that have made reporting of outbreaks mandatory have identified timeframes for reporting, while other partners have not, nor have such guidelines been set nationally. Reporting practices have also changed over time as provinces adapt to using the OS Reporting System in their jurisdictions which may have resulted in a change in the types of outbreaks that are reported. Further, as there are only six provinces as well as PHAC that report outbreaks through the OS Reporting System, the results of the current analysis are likely not nationally representative. Finally, issues with data quality and consistency have been identified. For example, interpretation of investigation start and end dates varies between jurisdictions and missing data for these variables, as well as for many other non-mandatory fields, limits the conclusions that can be drawn about these aspects of outbreaks investigations.

Future efforts will focus on continuing to enhance national representativeness by enrolling additional provinces and territories in the OS Reporting System. Based on the above limitations, discussion will continue among partners to increase the data quality and consistency of the system. Finally, existing data fields are undergoing review and additional variables are anticipated that will improve the description and characterization of outbreaks.

Conclusion

This analysis is the first national-level summary of outbreaks reported through the OS Reporting System. This system supports information sharing and collaboration among Canadian public health partners and offers the opportunity to obtain a national picture of foodborne outbreaks in Canada. As more jurisdictions join, the data will become more robust and will increase our national capacity to monitor trends and inform policy development and public health planning.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of our CNPHI and P/T epidemiology colleagues involved in the development and maintenance of the OS Reporting System and the hard work and dedication of Canadian public health professionals who diligently report enteric outbreak investigations in their jurisdictions.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None.

Funding: Funding for this program was provided by the Public Health Agency of Canada.

References

- 1.Thomas MK, Murray R, Flockhart L, Pintar K, Pollari F, Fazil A et al. Estimates of the burden of foodborne illness in Canada for 30 specified pathogens and unspecified agents, circa 2006. Foodborne Pathog Dis 2013. Jul;10(7):639–48. 10.1089/fpd.2012.1389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas MK, Murray R, Flockhart L, Pintar K, Fazil A, Nesbitt A et al. Estimates of foodborne illness-related hospitalizations and deaths in Canada for 30 specified pathogens and unspecified agents [2015 Aug 10. Epub ahead of print.]. Foodborne Pathog Dis 2015. Oct;12(10):820–7. 10.1089/fpd.2015.1966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reingold AL. Outbreak investigations—perspective. Emerg Infect Dis 1998. Jan-Mar;4(1):21–7. 10.3201/eid0401.980104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Public Health Agency of Canada. National Enteric Surveillance Program Annual Summary 2013. 2015. (Publication to follow: http://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/432850/publication.html)

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Surveillance for foodborne disease outbreaks, United States, 2013, Annual Report. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2015. [Google Scholar]