Abstract

Background

Stigma is widely recognized as a significant barrier to the prevention, management and treatment of sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections (STBBIs) in Canada. Despite major advances in STBBI prevention and treatment, and global efforts to reduce stigma, people living with or affected by STBBIs continue to experience stigma within health and social service settings in Canada.

Objective

To describe the development, content and evaluation of knowledge translation resources and training workshops designed to equip health and social service professionals with the knowledge and skills needed to provide more respectful and inclusive sexual health, harm reduction and STBBI services.

Methods

After conducting a literature review, environmental scan and key informant interviews, and developing a conceptual framework, the Canadian Public Health Association (CPHA) developed four knowledge translation resources and three training workshops in partnership with a number of community-based organizations and experts. The resources were drafted and reviewed by both service providers and individuals affected by STBBIs. The workshops were developed, piloted and then evaluated using post-workshop questionnaires.

Results

The four resources developed were a self-assessment tool related to STBBIs and stigma; a service provider discussion guide to facilitate respectful and inclusive discussions on issues related to sexuality, substance use and STBBIs; a toolkit focused on stigma reduction, privacy, confidentiality and the criminalization of HIV non-disclosure; and an organizational assessment tool related to STBBIs and stigma for health and social service settings. These knowledge translation resources were subsequently integrated into the content of three face-to-face trainings that were piloted and evaluated across the country. Post-workshop evaluation had an overall 85% response rate; 88% of participants noted increased awareness of various forms of stigma, 87% noted increased comfort discussing sexuality, substance use and harm reduction with their clients/patients, 90% reported increased awareness of organizational strategies to reduce stigma, and 93% reported being able to integrate workshop learnings into practice. In addition, there was strong support for professional development on issues related to STBBI stigma reduction.

Conclusion

These knowledge translation resources and training workshops represent a comprehensive set of tools developed in Canada that service providers can use to help reduce stigma when caring for clients/patients with STBBIs and related conditions. Evaluation indicates there is a strong willingness among health and social service providers to engage in educational opportunities in this area and that participation in the training workshops led to increased awareness and a willingness to adopt best practices.

Introduction

Stigma, defined as a dynamic process of devaluation that significantly discredits an individual in the eyes of others, is widely recognized as a barrier to the prevention, management and treatment of sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections (STBBIs), such as HIV, hepatitis B and C, human papillomavirus, genital herpes and syphilis (1). For individuals affected by STBBIs, stigma can lead to poor health and well-being, including mental health problems, social withdrawal, fear of disclosure of STBBIs and reduced sexual well-being (2), (3), (4), (5). Despite major advances in STBBI prevention and treatment, and global efforts to reduce stigma, numerous Canadian studies have identified health and social service settings as significant sources of stigma for people affected by STBBIs and, in particular, people living with HIV (3), (6), (7), (8). Stigma experienced within health and social service settings can affect an individual’s access to and usage of STBBI prevention, treatment and support services as well as adoption of preventative behaviours, including adherence to antiretroviral treatment for HIV (2).

A number of factors may contribute to stigma within service settings, all of which overlap to produce the complex and layered nature of STBBI stigma. These include providers’ discomfort in discussing sexuality and/or substance use; social norms stipulating that individuals affected by STBBIs are to blame due to participation in activities deemed morally disreputable, such as sexual promiscuity or substance use; and organizational policies and procedures that inadvertently contribute to stigma. For example, within health and social service settings, intake forms do not always use inclusive language; there are often penalties for missed appointments; and staff sometimes lack training on issues related to cultural safety (practices designed to make the client/patient feel comfortable) and stigma reduction (3), (9), (10), (11), (12), (13). Moreover, STBBI stigma does not occur in isolation and can compound other forms of stigma and oppression, including stigma against injection drug use, stigma against sex work, racism, sexism and homophobia (5), ultimately resulting in experiences of layered stigma for individuals with more than one stigmatized identity.

Between April 2014 and March 2017, the Canadian Public Health Association (CPHA), in partnership with many professionals and organizations, developed knowledge translation (KT) resources and training workshops to assist health and social service providers in offering safer and more inclusive sexual health, harm reduction and STBBI services. The objective of this paper is to describe the development, content and evaluation of these resources and workshops.

Methods

Scoping activities

Prior to developing project resources, CPHA undertook numerous scoping activities, including:

A literature review to identify the various forms of stigma and the factors that contribute to stigma

An environmental scan to identify the continuing education resources available to health and social service providers in Canada

Twenty interviews with key informants from various disciplines, including education and advocacy, research, health promotion and harm reduction program planning, community outreach, medicine, social work, law, nursing and pharmacy. Key informants worked in both rural and urban settings across the country (Ontario: n=8; Manitoba: n=3; Alberta: n=2; British Columbia: n=2; Quebec: n=2; Nova Scotia: n=2; Nunavut: n=1) and had various levels of expertise in providing services to individuals disproportionately affected by STBBIs

Three focus groups (in Fredericton, New Brunswick [n=9], Toronto, Ontario [n=6], and Thunder Bay, Ontario [n=12]) with individuals living with or affected by STBBIs to gather their insights into how service settings could be made safer and more inclusive. Focus group participants described experiencing internalized stigma in response to an STBBI diagnosis, and echoed findings from the literature on the factors that contribute to stigma, for example, moral judgment from service providers, particularly in relation to gender and sexual diversity and substance use; service provider discomfort in discussing sexual activity and substance use; a lack of services tailored to culture and community; a lack of time to discuss broader issues that impact health, such as housing and transportation; cost of treatment; and a dearth of harm reduction and anonymous STBBI testing services in the community

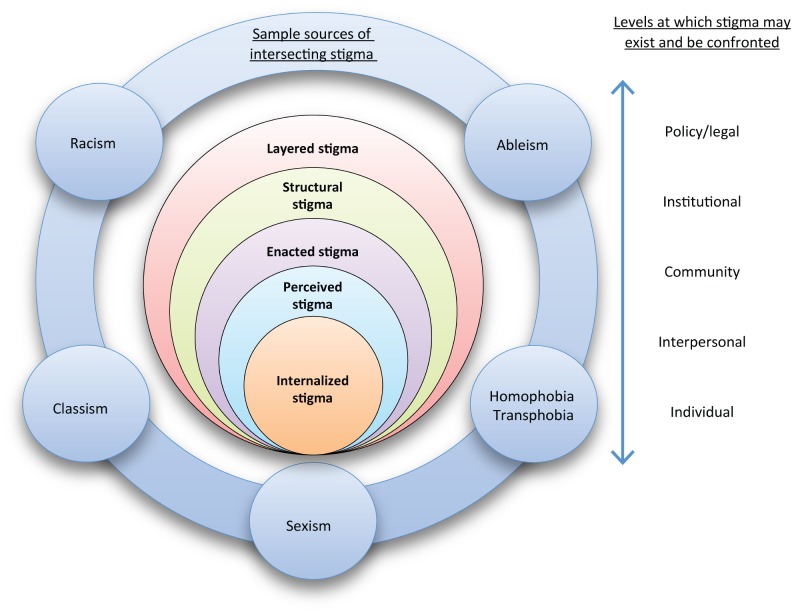

Development of a conceptual framework

The scoping efforts led to the development of a conceptual framework of STBBI stigma that was then used to guide the development of project resources (Figure 1). This framework highlights the various forms of stigma identified in the literature, including internalized, perceived, enacted, structural and layered stigma; some examples of intersecting sources of stigma, such as racism, classism and heterosexism are also identified as well as the various levels in society (e.g. individual, community, policy/legal) at which stigma may be experienced and confronted.

Figure 1. Defining STBBI stigmaa.

a This image was adapted from previously developed resources (14), (15), (16), (17)

Development of resources

Although the scoping activities described above identified a number of resources that focused on sexual health and harm reduction, there was a paucity of Canadian continuing education resources that focused on reducing STBBI stigma. To address this gap, the CPHA partnered with various experts and community-based organizations to develop four KT resources: a tool for health and social service providers to self-assess attitudes and beliefs about STBBIs and stigma; a discussion guide to facilitate respectful and inclusive discussions on issues related to sexuality, substance use and STBBIs; a toolkit focused on stigma reduction, privacy, confidentiality and the criminalization of HIV non-disclosure; and an organizational assessment tool related to STBBIs and stigma for health and social service settings. These KT resources were subsequently integrated into three face-to-face training workshops, developed in partnership with the Calgary Sexual Health Centre (CSHC) and piloted and evaluated to ensure relevancy and utility.

Self-assessment tool

The self-assessment tool was developed to help service providers reflect on their personal attitudes towards and beliefs about various STBBIs. This resource was adapted from the previously validated Healthcare provider HIV/AIDS stigma scale (18) in partnership with Dr. Anne Wagner, who led the research team that devised the original stigma scale, to incorporate a broader range of STBBIs and reflect the continual shift towards a more integrated approach to STBBIs (19). The revised tool was psychometrically validated following two rounds of pilot testing with 144 service providers from across Canada. Analysis of the pilot test findings demonstrated that the self-assessment tool has good to excellent internal consistency, as well as convergent and divergent validity with other measures of HIV stigma and social desirability. However, this second finding should be interpreted with caution due to the low reliability of the other measures of HIV stigma and social desirability in this sample.

Service provider discussion guide

This discussion guide highlights the communication strategies that service providers can use to ensure discussions related to sexuality, substance use and STBBIs are respectful and inclusive. The discussion guide was adapted from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention document A guide to taking a sexual health history (20) and revised based on best practices identified in the literature; key informant interviews with physicians, nurses, nurse practitioners, public health program managers, educators and researchers; pilot testing by physicians, nurses and nurse practitioners; and feedback from 14 individuals, including people living with HIV, people who use substances and sex workers, through three focus groups held in Victoria, British Columbia, Winnipeg, Manitoba and Toronto, Ontario. Following these consultations, changes were made to ensure the language used throughout the discussion guide was respectful and inclusive, and to include further dialogue examples.

Reducing stigma and discrimination through the protection of privacy and confidentiality

In partnership with the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network, this guidance was developed in response to key informants identifying the criminalization of HIV non-disclosure as a significant source of stigma in Canada and as an issue that service providers often have difficulty discussing with clients/patients. This resource explains the important role of privacy and confidentiality in reducing stigma related to STBBIs. It suggests several strategies that health and social service providers can use to deal with privacy, confidentiality, the criminalization of HIV non-disclosure and stigma reduction.

Organizational assessment tool for STBBIs and stigma

This tool includes 30 questions to help health and social service organizations assess their strengths and challenges relevant to the provision of welcoming and inclusive sexual health, harm reduction and STBBI services. The assessment tool was developed based on proven stigma reduction interventions described in the literature and following consultation with and piloting by experts in the field.

Training workshops

Three training workshops, founded on adult learning principles, were developed to help increase awareness and adoption of stigma reduction strategies within sexual health, harm reduction and STBBI services. To ensure the relevancy and utility of the workshops, CPHA and CSHC delivered 19 pilot workshops in 14 communities across Canada throughout 2015 and 2016. The 589 pilot workshop participants included nurses, nurse practitioners, social workers, physicians, counsellors, health educators, midwives, etc. They had varying levels of knowledge and experience in sexual health and harm reduction, although many provided specialized services to population groups disproportionately affected by STBBIs. The participants were asked to complete evaluation questionnaires before and after the pilot workshops, with the exception of a few workshops where there were time constraints. The findings were used to revise the workshop content and ensure relevance to the learning needs of service providers. Once validated for relevance and utility, the workshop materials, including facilitation manuals, participant workbooks and presentation slide decks, were made available to community organizations across the country to support their professional development efforts.

Evaluation

Measurement of the project impact focused primarily on immediate changes in awareness and knowledge via participation in the pilot workshops. Of the 589 health and social service providers who attended the pilot workshops, 483 were asked to complete pre- and post-workshop questionnaires, and an overall response rate of 85% was achieved. Participants were asked to rate what they learned, the applicability of the workshop content, and to identify areas for workshop improvement. Based on these evaluation findings, revisions were made to the workshop content. The large majority of participants self-reported an increase in knowledge through the pilot workshops; those that did not largely self-identified as experts in the area. Analyses of post-workshop questionnaire responses and sample participant comments are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Workshop participants’ feedback summary.

| Item assessed (Number of respondents)a | Number of respondents in agreement (%) | Sample participant comment |

|---|---|---|

| Increased awareness of various forms of stigma (n=397) | 349 (88%) | “Breakdown of different types of stigma and their impact was helpful.” |

| Increased comfort discussing sexuality, substance use and harm reduction with clients/patients (n=378) | 330 (87%) | “Role playing allowed people to practice using the skills learned and feel the discomfort a service user likely feels.” |

| Increased awareness of organizational strategies to reduce stigma (n=93) | 84 (90%) | “Good way of making us realize the effect of our language, build greater awareness of the types of comments we make and reflect on how to change structural problems.” |

| Able to integrate workshop learnings into practice (n=398) | 372 (93%) | “I hope to be able to make sustainable or at least start making steps in the right direction within my organization.” |

| General feedback | N/A | “It would be good if this was a mandatory workshop for all people who work with people on any level.” |

a Overall findings are from across the three training workshops; given the unique learning objectives of each, the post-workshop questionnaire varied slightly for each and therefore the sample size for each item assessed varies

Workshop materials as well as the complementary KT resources are available on the CPHA website at https://www.cpha.ca/sexually-transmitted-and-blood-borne-infections-and-related-stigma.

Discussion

This project demonstrated that considerable progress can be made in improving health and social service professionals’ capacity to reduce stigma when providing sexual health, harm reduction and STBBI services. Through project-scoping activities, CPHA was able to gather insight from both individuals affected by STBBIs as well as experts on optimal strategies for reducing stigma within health and social service settings. The CPHA was also able to leverage a great deal of knowledge and expertise by partnering with community-based organizations as well as professionals during resource development and piloting. The majority of the participants reported improved awareness of STBBI stigma reduction strategies following participating in the pilot workshops; they also indicated their intention to apply workshop learnings and share the workshop resources with colleagues.

Despite these successes, there were some limitations. Most notably, post-workshop measurement focused primarily on immediate changes to attitudes and knowledge. To assess changes in provider practices as well as changes within organizational policies and procedures, intermediate and longer-term follow-up is required. Also of note is that the project resources do not address the specific needs of the various populations disproportionately affected by STBBIs. The resources may therefore need to be adapted for working with specific population groups. Finally, further effort is needed to ensure these resources and other similar initiatives reach a broader audience of service providers in Canada interested in training resources related to STBBI stigma reduction.

The CPHA has recently been awarded a project to continue to develop training opportunities for health and social service providers, and to work with other organizations to support their use of workshop materials, particularly where training opportunities are scarce. Future efforts will also focus on assessing intermediate and longer-term changes (e.g. through six-month follow-up surveys) in provider- and organizational-level practices.

Conclusion

Reduction of STBBI stigma reduction represents an issue of continuing public health importance. This project demonstrated that evidence-based, user-friendly, culturally safe resources incorporated into training workshops can be effective in improving service provider capacity to reduce stigma. Our evaluation indicates a strong willingness among service providers in Canada to engage in these opportunities.

Acknowledgements

This project was made possible by the support and involvement of the many organizations and professionals who reviewed project resources and provided expert feedback through key informant interviews, community consultations and pilot testing. We are also indebted to the members of the project’s Expert Reference Group who offered expert guidance and support throughout various stages of the project. Finally, we would like to acknowledge the individuals from various communities who participated in focus groups and shared their stories, insight and wisdom.

Conflict of interest: None.

Funding: This project was funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada for the period April 2014 to March 2017. The CPHA has also been funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada to continue its efforts in this field from April 2017 to March 2022.

References

- 1.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). UNAIDS terminology guidelines, 2015. Geneva (CH): Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS; 2015. http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2015_terminology_guidelines_en.pdf

- 2.Rueda S, Mitra S, Chen S, Gogolishvili D, Globerman J, Chambers L et al. Examining the associations between HIV-related stigma and health outcomes in people living with HIV/AIDS: a series of meta-analyses. BMJ Open 2016. Jul;6(7):e011453. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mill J, Edwards N, Jackson R, Austin W, MacLean L, Reintjes F. Accessing health services while living with HIV: intersections of stigma. Can J Nurs Res 2009. Sep;41(3):168–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foster LR, Byers ES. Predictors of the Sexual Well-being of Individuals Diagnosed with Herpes and Human Papillomavirus. Arch Sex Behav 2016. Feb;45(2):403–14. 10.1007/s10508-014-0388-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wagner AC, Girard T, McShane KE, Margolese S, Hart TA. HIV-related stigma and overlapping stigmas towards people living with HIV among health care trainees in Canada. AIDS Educ Prev 2017. Aug;29(4):364–76. 10.1521/aeap.2017.29.4.364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins E, Cain R, Bereket T, Chen YY, Cleverly S, George C et al. Living & serving II: 10 years later - the involvement of people living with HIV/AIDS in the community AIDS movement in Ontario. Toronto (ON): The Ontario HIV Treatment Network; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Worthington C, Jackson R, Mill J, Prentice T, Myers T, Sommerfeldt S. HIV testing experiences of Aboriginal youth in Canada: service implications. AIDS Care 2010. Oct;22(10):1269–76. 10.1080/09540121003692201 10.1080/09540121003692201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gagnon M. Rethinking HIV-related stigma in health care settings: a research brief. Ottawa (ON): uOttawa; 2014. https://www.cocqsida.com/assets/files/Research-Brief_RethinkingHIV-17juillet2014.pdf

- 9.Jaworsky D, Gardner S, Thorne JG, Sharma M, McNaughton N, Paddock S et al. ; CHIME Research Group. The role of people living with HIV as patient instructors - reducing stigma and improving interest around HIV care among medical students. AIDS Care 2017. Apr;29(4):524–31. 10.1080/09540121.2016.1224314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brener L, Von Hippel W, Kippax S, Preacher KJ. The role of physician and nurse attitudes in the health care of injecting drug users. Subst Use Misuse 2010. Jun;45(7-8):1007–18. 10.3109/10826081003659543 10.3109/10826081003659543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuzzell L, Fedesco HN, Alexander SC, Fortenberry JD, Shields CG. “I just think that doctors need to ask more questions”: sexual minority and majority adolescents’ experiences talking about sexuality with healthcare providers. Patient Educ Couns 2016. Sep;99(9):1467–72. 10.1016/j.pec.2016.06.004 10.1016/j.pec.2016.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gott M, Galena E, Hinchliff S, Elford H. “Opening a can of worms”: GP and practice nurse barriers to talking about sexual health in primary care. Fam Pract 2004. Oct;21(5):528–36. 10.1093/fampra/cmh509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nyblade L, Stangl A, Weiss E, Ashburn K. Combating HIV stigma in health care settings: what works? J Int AIDS Soc 2009. Aug;12(1):15. 10.1186/1758-2652-12-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Churcher S. Stigma related to HIV and AIDS as a barrier to accessing health care in Thailand: a review of recent literature. WHO South-East Asia J Public Health 2013. Jan-Mar;2(1):12–22. 10.4103/2224-3151.115829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loutfy MR, Logie CH, Zhang Y, Blitz SL, Margolese SL, Tharao WE et al. Gender and ethnicity differences in HIV-related stigma experienced by people living with HIV in Ontario, Canada. PLoS One 2012;7(12):e48168. 10.1371/journal.pone.0048168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stangl AL, Brady L, Fritz K. Measuring HIV stigma and discrimination: Technical Brief July 2012. Washington, DC: International Centre for Research on Women; 2012. http://strive.lshtm.ac.uk/system/files/attachments/STRIVE_stigma%20brief-A4.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corrigan PW, Markowitz FE, Watson AC. Structural levels of mental illness stigma and discrimination. Schizophr Bull 2004;30(3):481–91. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagner AC, Hart TA, McShane KE, Margolese S, Girard TA. Health care provider attitudes and beliefs about people living with HIV: Initial validation of the Health Care Provider HIV/AIDS Stigma Scale (HPASS). AIDS Behav 2014. Dec;18(12):2397–408. 10.1007/s10461-014-0834-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paquette D. Integrated approach to the prevention and control of sexually transmitted and blood borne infections. Ottawa (ON): Public Health Agency of Canada. http://www.catie.ca/sites/default/files/2-845-1-DanaPaquette.pdf

- 20.A guide to taking a sexual health history. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US National Center for HIV Viral Hepatitis STD and TB Prevention; 2011. http://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/SexualHistory.pdf