Summary

The incidence of West Nile virus (WNv) has waxed and waned in Canada over the past 12 years, but it is unlikely to disappear. Climate change models, which suggest warming temperatures and changing patterns of precipitation, predict an expansion of geographic range for WNv in some regions of Canada, such as the Prairie provinces. Such projected changes in WNv distribution might also be accompanied by genetic changes in the virus and/or the range of bird and insect host species it infects. To address this risk, emphasis should be placed on preventing exposure to infected mosquitoes, conducting high-quality surveillance of WNv and WNv disease, controlling mosquito vectors, and promoting public and professional education.

Introduction

West Nile virus a globally distributed member of the genus Flavivirus, infects a wide range of mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians, as well as a variety of mosquito species, including members of the genus Culex. The virus is primarily maintained in bird populations through transmission by mosquitoes, and zoonotic transmission occurs when a mosquito that has fed on an infected bird subsequently bites a human host. WNv infection can also be transmitted from person to person through medical procedures, particularly blood transfusion and organ transplantation (1,2). Since 1999, when human WNv disease was first recognized in humans in North America, the virus has spread continent-wide in both Canada and the USA, with annual outbreaks of varying intensity and regional distribution.

The goal of this commentary is to suggest that, although the impact of WNv has waxed and waned over the past decade or more, the virus will continue to have significant individual and public health consequences for the foreseeable future, and concerted action is required to minimize these consequences. We will review the epidemiology of WNv and WNv disease, provide a brief overview of the WNv epidemic in North America and then close by highlighting the need for ongoing vigilance regarding this public health challenge.

Epidemiology

Although it remains unknown what proportion of individuals who are bitten by a mosquito carrying WNv become infected, serological surveys and studies of viremic blood donors suggest that 70%–80% of infections are asymptomatic and/or unrecognized (3,4). Symptomatic disease, which usually emerges 2–15 days after infection, ranges in severity from transient febrile illness with headache, chills, skin rash, nausea and muscle aches in the majority of cases to severe and sometimes fatal neurological disease in the form of meningitis, encephalitis or poliomyelitis/acute flaccid paralysis in approximately 1% of those infected (5). Most affected individuals recover fully from acute illness with presumably lifelong immunity to re-infection, but recovery can be prolonged, with sequelae of weakness, fatigue, neurologic and cognitive deficits, and psychiatric problems, some of which may be permanent. Individuals with underlying medical conditions and those over 70 years of age appear to be particularly susceptible to such effects (2,6). There are currently no approved WNv vaccines or specific treatments for WNv disease in humans.

West Nile virus in North America

Historically, the first recorded case of WNv disease occurred in Uganda in 1937. Since then, local or regional WNvepidemics of relatively mild disease were reported intermittently from Africa and Israel until the 1990s, when outbreaks of severe disease emerged in western Russia as well as southern and eastern Europe (2). Such scattered epidemics continue to occur in Europe, possibly through repeated introductions by migratory birds (7). The first autochthonous North American cases of WNv disease were recorded in New York City in August 1999 (8). Strikingly, by 2001 WNv had spread to eastern Canada, the southeastern USA, Mexico and the Caribbean; by 2003 to the west coast of the USA; by 2005 to South America; and by 2008 to the west coast of Canada (9).The virus is now considered firmly established in the Americas.

WNv was first detected in Canada in 2001 in birds and mosquitoes collected from Ontario (10). Beginning with the first documented cases the following year, human WNv disease has now been reported from 10 Canadian provinces and territories (including travel-related cases in NB, NS, PE and YK). In total, 5,454 cases of WNv disease and asymptomatic infection were reported to the Public Health Agency of Canada between 2002 and 2013, including 1,072 cases of WNv neurological disease. Using the above rates it can therefore be estimated that in the range of 18,000–27,000 human WNv infections have occurred in Canada since 2002, possibly with a proportional rate of neurological disease higher than that reported from the USA. Several serosurveys have been conducted in Canada to estimate rates of human exposure to WNv, with resulting estimates typically of 3%–5%. However, in rural Saskatchewan following the 2003 WNv season, the seroprevalence was nearly 17% (11).

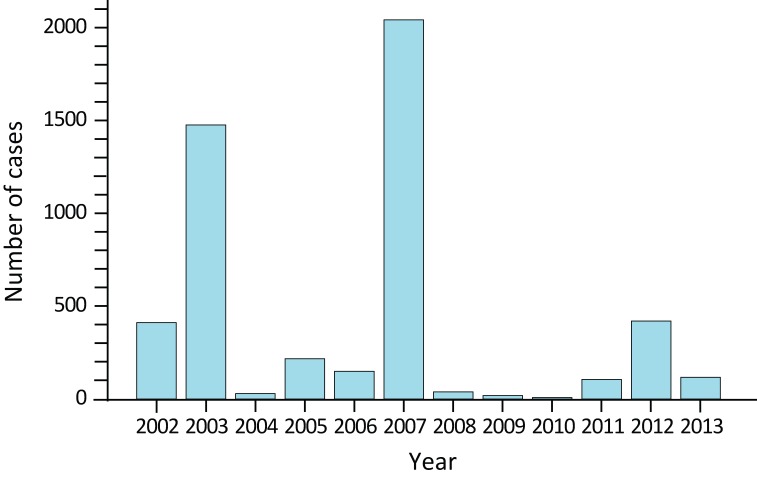

It should be noted that the reported annual national incidence of WNv disease has varied dramatically, from a total of 5 cases in 2010 and peaks of 1,495 and 2,401 cases in 2003 and 2007 respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Annual number of cases of human West Nile virus disease and asymptomatic infection reported to the Public Health Agency of Canada: 2002-2013

Regional variation has also been significant: for example, the majority of Canadian cases were reported from the Prairie provinces (AB, SK, MB) in 2003 and 2007, and from the Central provinces (ON, QC) in 2002 and 2012 (12). The long-term economic costs of acute care and persistent health effects in individuals affected by WNv disease can thus be assumed to be significant, although data that would support realistic estimates of these costs for Canada are lacking. A recent estimate of total cost to the US economy from 1999 through 2012 fell in the range of US $700M–1B (13).

West Nile virus variation and change

During its evolutionary history WNv has undergone considerable genetic diversification, resulting in the presence of four major lineages, of which two (Lineages 1 and 2) are known to cause disease in humans. Lineage 2,

which has not yet been identified in North America, has recently caused human WNv disease in Europe (7). Within Lineage 1, the most widespread lineage globally, a number of sub-lineages have been identified, and certain genetic changes have been associated with North American colonization and the biological behavior of the virus, particularly in birds and mosquitoes (14). For example, the NY99 WNv sub-lineage that initially colonized the Eastern USA shares a specific genetic change with a 1998 Israeli bird-derived strain that appears to confer on the virus an ability to replicate to higher levels in birds (15). The NY99 sub-lineage was also itself rapidly displaced by a derivative sub-lineage (WN02), which appears capable of faster invasion of the salivary glands of Culex mosquitoes after feeding, especially at higher temperatures, in turn suggesting a capacity to spread more rapidly during warmer weather (16).

Thus, by enhancing the reproductive potential and virulence of WNv in mosquitoes and birds respectively, genetic change appears to have facilitated the establishment and spread of WNv in North America, as well as its capacity to cause disease outbreaks. These effects are expected in turn to be amplified by human-driven environmental modification and change. For example, one recent California-based study found associations between per capita income and related factors (e.g. density of poorly maintained swimming pools) and the prevalence of WNv infection in both mosquitoes and humans (17). Another research group found that bird species diversity, often affected by human activity, was negatively correlated with local WNv infection rates of Culex mosquitoes in a Chicago suburb (18).

On a broader scale, along with warming temperatures and changing patterns of precipitation, climate change models predict an expansion of geographic range for WNv in North America into regions with higher numbers of previously unexposed human and animal hosts (19). Some regions of Canada, such as the Prairie provinces, may be particularly subject to such effects (20). These changes in WNv distribution may also be accompanied by additional genetic changes in the virus and/or the range of bird and insect host species it infects. Combined with the known positive correlation between WNv prevalence and temperature, and the (somewhat unexpected) negative correlation with precipitation amounts, these considerations suggest that the public health risk of WNv disease may increase in North America in the coming decades (16,19).

The need for prevention

As discussed above, complex interactions occur among WNv, its numerous insect, bird and mammal hosts, and the environment, and for these reasons it has not yet proven possible to anticipate the occurrence of WNv or WNV disease at a level of spatial detail that would permit highly targeted local public health intervention. It is therefore clear that to minimize the impacts of WNv disease on the health of Canadians emphasis should be placed on primary prevention of human exposure to mosquitoes that may be carrying the virus, with the support of high-quality surveillance of WNv and WNv disease, control of mosquito vectors, and public and professional education. In Canada, a number of these preventive approaches are in place. For example, WNv disease is nationally notifiable and reportable, by statute, in all provinces and territories in Canada, and integrated national surveillance has been carried out through federal/provincial/territorial (F/P/T) partnership since 2002 (10,12). The national surveillance effort is based on weekly sharing of surveillance data on humans, horses, birds and mosquitoes with the Public Health Agency of Canada by diverse partners, including provincial/territorial ministries of health, Canadian Blood Services and Héma-Québec, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency and the Canadian Cooperative Wildlife Health Centre. This information is then assembled into weekly national reports (12) during the peak risk season, as determined by an F/P/T working group at the beginning of each summer. The weekly reports are supplemented with information regarding WNv activity in the USA and in Europe.

Municipalities often undertake targeted control of mosquito populations, based on information about mosquito activity, infection rates and the occurrence of human and/or animal WNv disease in the area. Other important, national, public health measures are routine testing of blood donations by Canadian Blood Services and Héma-Québec to prevent blood-borne WNv transmission and often to provide the earliest indication of WNv activity in a given season, and delivery of expert scientific, epidemiological and laboratory diagnostic support (federally, through the National Microbiology Laboratory and the Centre for Food-borne, Environmental and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases). There is also, of course, much that Canadians can do to protect themselves and their families from exposure to mosquitoes that could carry WNv. Such measures include minimizing standing water

to reduce local mosquito abundance, using insect repellents containing the active ingredient N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide (DEET), reducing outdoor activity when mosquitoes are most active and wearing protective clothing (21).

Conclusions

West Nile virus and the health problems it causes are likely to remain significant concerns for Canada in the foreseeable future. Surveillance, medical diagnosis and screening, mosquito control and public education programs have all been instituted in Canada. However, the dynamic nature of the pathogen, the complexity of its ecological interactions and the unpredictability of its detailed behaviour in time and space all indicate that additional efforts are required to maintain and improve the efficacy of primary prevention. Surveillance, research, logistic support and intervention measures undertaken by federal, provincial and territorial governments will continue to play key roles in these efforts. However, the issue of WNv is of importance to all Canadians, and access to up-to-date, scientifically based knowledge will continue to have a major positive impact.

References

- 1.Fearon MA. West Nile story: the transfusion medicine chapter. Future Virol 2011;6(12):1423–34. 10.2217/fvl.11.122 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petersen LR, Brault AC, Nasci RS. West Nile virus: review of the literature. JAMA 2013. Jul;310(3):308–15. 10.1001/jama.2013.8042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mostashari F, Bunning ML, Kitsutani PT, Singer DA, Nash D, Cooper MJ et al. Epidemic West Nile encephalitis, New York, 1999: results of a household-based seroepidemiological survey. Lancet 2001. Jul;358(9278):261–4. 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05480-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zou S, Foster GA, Dodd RY, Petersen LR, Stramer SL. West Nile fever characteristics among viremic persons identified through blood donor screening. J Infect Dis 2010. Nov;202(9):1354–61. 10.1086/656602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petersen LR, Carson PJ, Biggerstaff BJ, Custer B, Borchardt SM, Busch MP. Estimated cumulative incidence of West Nile virus infection in US adults, 1999-2010. Epidemiol Infect 2013. Mar;141(3):591–5. 10.1017/S0950268812001070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sejvar JJ. Clinical manifestations and outcomes of West Nile virus infection. Viruses 2014. Feb;6(2):606–23. 10.3390/v6020606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sambri V, Capobianchi M, Charrel R, Fyodorova M, Gaibani P, Gould E et al. West Nile virus in Europe: emergence, epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Clin Microbiol Infect 2013. Aug;19(8):699–704. 10.1111/1469-0691.12211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nash D, Mostashari F, Fine A, Miller J, O’Leary D, Murray K et al. ; 1999 West Nile Outbreak Response Working Group. The outbreak of West Nile virus infection in the New York City area in 1999. N Engl J Med 2001. Jun;344(24):1807–14. 10.1056/NEJM200106143442401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Artsob H, Gubler DJ, Enria DA, Morales MA, Pupo M, Bunning ML et al. West Nile virus in the New World: trends in the spread and proliferation of West Nile virus in the Western Hemisphere. Zoonoses Public Health 2009. Aug;56(6-7):357–69. 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2008.01207.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drebot MA, Lindsay R, Barker IK, Buck PA, Fearon M, Hunter F et al. West Nile virus surveillance and diagnostics: A Canadian perspective. Can J Infect Dis 2003. Mar;14(2):105–14. 10.1155/2003/575341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schellenberg TL, Anderson ME, Drebot MA, Vooght MT, Findlater AR, Curry PS et al. Seroprevalence of West Nile virus in Saskatchewan’s Five Hills Health Region, 2003. Can J Public Health 2006. Sep-Oct;97(5):369–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). West Nile virus MONITOR 2014. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/wnv-vwn/index-eng.php

- 13.Staples JE, Shankar MB, Sejvar JJ, Meltzer MI, Fischer M. Initial and long-term costs of patients hospitalized with West Nile virus disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2014. Mar;90(3):402–9. 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reisen WK. Ecology of West Nile virus in North America. Viruses 2013. Sep;5(9):2079–105. 10.3390/v5092079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brault AC, Huang CY, Langevin SA, Kinney RM, Bowen RA, Ramey WN et al. A single positively selected West Nile viral mutation confers increased virogenesis in American crows. Nat Genet 2007. Sep;39(9):1162–6. 10.1038/ng2097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kilpatrick AM, Meola MA, Moudy RM, Kramer LD. Temperature, viral genetics, and the transmission of West Nile virus by Culex pipiens mosquitoes. PLoS Pathog 2008. Jun;4(6):e1000092. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harrigan RJ, Thomassen HA, Buermann W, Cummings RF, Kahn ME, Smith TB. Economic conditions predict prevalence of West Nile virus. PLoS One 2010. Nov;5(11):e15437. 10.1371/journal.pone.0015437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamer GL, Chaves LF, Anderson TK, Kitron UD, Brawn JD, Ruiz MO et al. Fine-scale variation in vector host use and force of infection drive localized patterns of West Nile virus transmission. PLoS One 2011;6(8):e23767. 10.1371/journal.pone.0023767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harrigan RJ, Thomassen HA, Buermann W, Smith TB. A continental risk assessment of West Nile virus under climate change [First published: February 27, 2014]. Glob Change Biol 2014. Aug;20(8):2417–25. 10.1111/gcb.12534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen CC, Jenkins E, Epp T, Waldner C, Curry PS, Soos C. Climate change and West Nile virus in a highly endemic region of North America. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2013. Jul;10(7):3052–71. 10.3390/ijerph10073052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). West Nile virus - Protect Yourself! 2014. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/wn-no/index-eng.php