Abstract

Background

With Canada’s senior population increasing, there is greater demand for family physicians with enhanced skills in Care of the Elderly (COE). The College of Family Physicians Canada (CFPC) has introduced Certificates of Added Competence (CACs), one being in COE. Our objective is to summarize the process used to determine the Priority Topics for the assessment of competence in COE.

Methods

A modified Delphi technique was used, with online surveys and face-to-face meetings. The Working Group (WG) of six physicians acted as the nominal group, and a larger group of randomly selected practitioners from across Canada acted as the Validation Group (VG). The WG, and then the VG, completed electronic write-in surveys that asked them to identify the Priority Topics. Responses were compiled, coded, and tabulated to identify the topics and to calculate the frequencies of their selection. The WG used face-to-face meetings and iterative discussion to decide on the final topic names.

Results

The correlation between the initial Priority Topic list identified by the VG and that identified by the WG is 0.6793. The final list has 18 Priority Topics.

Conclusion

Defining the required competencies is a first step to establishing national standards in COE.

Keywords: priority topics, key features, enhanced skills, care of the elderly, core competencies

INTRODUCTION

The average age of Canada’s population is changing dramatically. The number of seniors has increased from 8% of the population in 1971 to 14.8% in 2012.(1,2) By 2020, family physicians can expect at least 30% of outpatients, 60% of inpatients, and 95% of nursing home patients to be aged over 65 years.(3,4)

Family physicians provide the largest share of care for older patients, but have variable training and experience with this population.(3,5) The College of Family Physicians of Canada (CFPC) has accredited enhanced skills training in ‘Care of the Elderly’ (COE) since 1992. Two hundred and forty-five family physicians had successfully completed this training by 2014, either as residents or via re-entry to training from practice.(6) These physicians provide both comprehensive care to seniors and advanced care to frail patients, often in collaboration with geriatric medicine specialists and geriatric psychiatrists. Given the well-recognized shortage of physicians trained in geriatric care, there will be an increasing demand for family physicians with enhanced skills and added competency in COE.(7)

There has been a shift towards competency-based medical education (CBME) of residents. A core competency (CC) is a fundamental knowledge, ability or expertise in a subject area or skill-set within a specific field of care.(8) Competencies relate to the skills, behaviours, and knowledge that are gained through training or practice, and explicitly define what a capable physician should be able to do to practise safely and effectively. The use of competencies, to guide curriculum and assessment in post-graduate medical education, is a significant model change from a focus on clinical knowledge and numerical ratings on In-training Evaluation Reports (ITERs). (9) Professional competence is more than factual knowledge and ability to solve problems. It is defined by the ability to manage ambiguous problems, tolerate uncertainty, and make decisions with limited information.(10)

Competencies in Care of the Elderly/Geriatrics for Family Medicine training have been described in two publications. Williams et al.(11) published 26 defined competencies. The development process excluded any that were not feasible in current educational environments, or that were not endorsed by the educational institutions. Charles et al.(12) reported 85 competencies, developed with input from academic educators.

The CFPC is not an educational institution, but is a certifying body for core Family Medicine training and for enhanced skills level in certain domains. The CFPC needs to determine what competencies residents must attain for the purposes of certification and practice, and to be able to grant certification based on effective and efficient resident evaluation. Assessment of specific clinical competencies and of overall competence is a challenge, as assessment time and resources are always limited. We must make “a plausible inference of overall competence from a limited number of observations.”(13) It is therefore important to select the observations that will be most predictive of competence.

“Priority Topics” and “Key Features” are an approach to assessment(14) which focuses on the most critical clinical elements and issues. Each domain of competence is described by a set of Priority Topics, and the competencies themselves are described by Key Features and by observable behaviours for the more generic essential skills of family medicine, such as professionalism and communication skills.(15–19)

Given the importance of having family physicians with skills in COE, it is desirable to increase the number of physicians at the Enhanced Skills level of expertise. The CFPC hoped to develop a clear framework for assessing the competence of residents training in COE and of practicing physicians (in a practice-eligible route of certification) to improve access and to standardize a shared competence to expert care of frail and healthy seniors. This paper describes the development of Priority Topics, which is the first step of the process to establish competence in COE at the Enhanced Skills level.

METHODS

A modified Delphi technique was used with a small Working Group (WG) of six family physicians. This group was selected from members of the CFPC Health Care of the Elderly Committee (HCOE – http://www.cfpc.ca/CareOfTheElderly/). A Validation Group (VG) was comprised of 140 physicians selected randomly from a CFPC register of members with an interest in COE, and a convenience sample of 72 others identified as experienced practitioners/teachers in COE by the WG. Randomization was performed after stratification to optimize regional representation, gender parity, and a mix of experienced and newer practitioners.

The WG, and then the VG, completed electronic write-in surveys (Appendix 1) that asked them to identify Priority Topics for the assessment of competence in Enhanced Skills level of COE. Responses were compiled, coded, and tabulated to calculate the frequencies of topics selected by respondents. The WG then used face-to-face meetings and iterative discussion to confirm which topics identified by WG and VG would be the final Priority Topics. Consensus topics that all members of the Working Group agreed to as being appropriate were retained, and those that were not were discarded. Topics that did not reach consensus were identified and discussed formally with all members of the WG. Those topics were revised until there was consensus or discarded because there was lack of agreement.

In order to avoid potential “contamination” of data or loss of quality ideas due to peer pressure, the members of the WG and VGs were instructed to respond independently and to base their answers on their personal experience only, rather than on input from colleagues or the literature. They were asked to choose only those topics that they deemed most important to the assessment of competence. The participants were also advised to not limit their choices by the feasibility of evaluation at this stage.

DATA ANALYSES

Descriptive Statistics

Demographics of the VG respondents; frequencies of citation for Priority Topics; and Pearson correlations between ranking of the Priority Topics by the WG and by the VG were collected and reported.

Ethics

This study was approved by the Health Research Ethics Board at the Universities of Alberta and Queen’s University. The CFPC paid for the travel expenses for meetings of the WG, but members received no honoraria or grants.

RESULTS

Nineteen per cent (19%) (41/212) of the VG responded and 37 of these submissions were complete. The respondents were distributed nationally, but 37% came from Ontario. Eighty-one per cent (81%) reported some involvement in teaching, and one quarter were University Department of Family Medicine Enhanced Skills in COE Program Directors. Forty-nine percent (49%) had more than 10 years of experience, and 55% had a mixed or broad-based clinical practice. Eighty-four per cent (84%) of respondents were from urban areas. Respondents spent on average 60% of their total practice focused on seniors’ care.

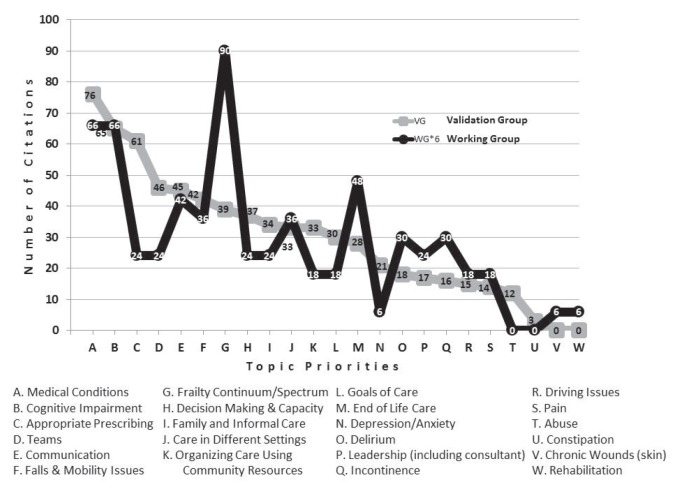

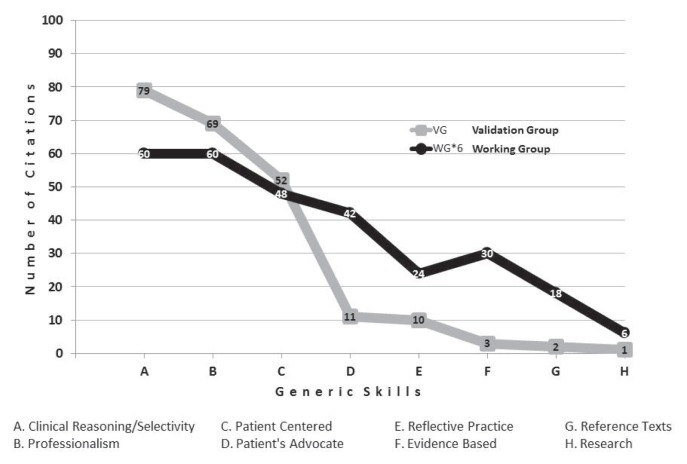

The finalized list of 18 priority topics is seen in Table 1. Five possible topics were not retained by the WG as being priorities after review of VG topics. The Pearson correlation between the results of the VG and the first iteration of Priority Topics frequencies done by the WG is 0.6793. Even though there are four topics with quite marked differences (Frailty, End-of life care, Depression, and Anxiety), the overall correlation was very good (see Figure 1). There is an even higher correlation (0.8597) for the generic skills of competence generated by VG and WG.

TABLE 1.

Priority Topics for the assessment of competence in Care of the Elderly (COE) for family physicians at the enhanced skills level

| The family physician with enhanced skills (added competence) in COE should be able to deal competently with the following clinical problems/situations for patients in all contexts of care, from basic through complex. The detailed expectations for each topic will be described by the Key Features. Priority topics (for the older patient) (by frequency of citation by Validation group)

|

Generic priorities for assessment of competence: the five most commonly identified priorities for generic competencies in Care of the Elderly (Enhanced skills level) were five of the six Essential Skills of Family Medicine (exception: Procedure skills):

|

FIGURE 1a.

Frequencies of citations by topic

DISCUSSION

Our goal is to share the process used to develop the Priority Topics, and to present the final list of topics (Table 1). This list represents the problems that a successfully certified COE practitioner should be able to deal with in practice. The Priority Topics are those which are more indicative of overall competence in COE for certification, which is relevant as time and resources for assessment means we cannot evaluate all topics and domains.

The approach we used differs from existing publications about core competencies in COE in that it focused on the practitioner and the patient population, rather than educational programs and curricula. The primary goal was to determine the priorities for the assessment and determination of competence, as opposed to the educational approaches and objectives that may be used to help to achieve competence. While these two goals are related, they are not identical. In particular, if there is a discrepancy between the competencies duly identified as priority for practice and the content of the educational programs, it is the educational programs that should be modified, not the competencies. Thus, it is practice that should dictate curriculum.

We decreased the emphasis on educational aspects by using specific instructions and directions, by the choice of participants, and by the design of the survey questionnaire and directed deliberations. The survey questionnaire was also designed to provide opportunities and several ways for the respondents to identify their assessment priorities. According to Soto,(20) “Task-oriented approaches examine problem-solving activities and outcomes, while person-oriented approaches emphasize the KSAs (Knowledge skills and attitudes) required for practice.” Questions 1 and 4 (Appendix 1) created a list of situations that could be qualified as a Task Inventory.(21) However, the context was patient- and encounter-centered, because competence in family medicine must be considered with reference to the clinical encounter.(16) Questions 2 and 3, on the other hand, focused on decision-making and cognitive skills, as well as personal attributes. This approach fits the Comprehensive Practice Analysis suggested by D’Costa(22) and Raymond.(23) The multiple approaches we used provide a richer and thicker definition of the Priority Topics associated with competence in this domain.

The number of topics produced using this approach is smaller than list of competencies developed using educators as the primary input for development; Williams et al.(11) reported 26 competencies and Charles et al.(12) reported 57 basic and 28 advanced competencies. Work is already underway to define competence at the resident level in internal medicine, family medicine, and emergency medicine, with the aim of integrating them with competencies at different levels of training and thereby decrease duplication of effort.(24) At the practitioner level, the American Geriatrics Society has defined 76 milestones to establish competence for graduating fellows.(25) As such, they all can serve as useful references to evaluate the success of programs, either for education or for certification, and the choice of which lists to use will depend on how effectively and efficiently they fit the specific needs of the educational setting.

The relatively small final number of Priority Topics (18) has many advantages from a certification (and learning) point of view, as it clarifies the scope of expectations and will help ensure that assessment will concentrate on issues that have been identified as important. The small number is partly a function of the limited number of choices that were allowed in the survey responses, but there was a notable consistency in the individual responses and between the WG and VG. The majority of the topics or problems that were cited were included in this final list, and those that were not included were not suggested very frequently by participants. There was no standard format applied to the nomenclature—in most cases the WG retained the wording used by the majority of the respondents.

The WG reached consensus at face-to-face meetings for all Priority Topics listed, working from their own input and the input from the Validation survey, and refined through a total of four iterations until stability was reached. The work at the face-to-face meetings was guided by established principles for competency-based education. Although a formal Delphi procedure avoids situations in which more persuasive or dominant panel members might influence the consensus, according to Boulkedid et al.,(26) the “absence of a meeting may deprive the Delphi procedure of benefits related to face-to-face exchange of information, such as clarification of reasons for disagreements”. The first iteration of Priority Topics was created according to the frequency at which they appeared in the surveys. However, the fact that a problem is cited frequently does not necessarily mean that it requires a high level of competence. Epstein and Hundert(27) write that a “competent clinician possesses the integrative ability to think, feel and act like a physician.” The group efforts were guided by Schon,(10) who wrote, “Professional competence is more than factual knowledge and the ability to solve problems with clear-cut solutions: it is defined by the ability to manage ambiguous problems, tolerate uncertainty, and make decisions with limited information.”

One concern about our approach is that its validity and reliability may be compromised if assertive and dominant panel members imposed their opinion, and if the weak ones change their point of view in order to align with the majority. We tried to mitigate this by having a small working group with members known for their work on committees, using strong staff procedural lead at all meetings, and by first seeking independent opinions from all participants. In addition, topics were discarded when consensus was not reached.

A limitation of our study is that it was consensus-based and, as such, may not be as comprehensive as it could be. There were some items that had little support (few citations in surveys, little support in the group discussions), and were discarded. This, however, was consistent with our aim to generate Priority Topics that are highly predictive of overall competence and can be used for selective and concentrated assessment, rather than a longer and inclusive list of all items that could be considered.

A final limitation is the 19% response rate to the survey, with a total of 37 complete independent responses for the VG, and 6 from the WG. Respondents were, however, well distributed across the sampled demographic, and the consistency of the independent responses across the two groups (working and validation) suggests that the data are useful for qualitative purposes. Although the frequencies of the responses were calculated, they were not used in any quantitative sense, and all topics retained on the Priority Topic list are considered to be equal. Any future ranking for selection purposes would be done as an independent process.

The identification of the Priority Topics was the first step in planning for the assessment of competence in COE for family physicians at the Enhanced Skills level. The next step is to develop the Key Features for each topic and this is well underway. The reflections of Epstein & Hundert(27) and Schon(10) are even more applicable to this phase of the definition of competence. Once the Key Features are developed, the next phase will ask residency programs to review their current program objectives with respect to these Priority Topics and Key Features, identify gaps, and analyze the reasons for the gaps. It is hoped that these activities will occur in late 2017 and 2018.

CONCLUSION

Defining the required competencies is a first step to establishing national standards in COE, and these standards should become the basis for determining the granting of CACs. The methodology used, and the high correlation between the lists generated by the WG and the VG, suggest that this Priority Topic list is valid. The WG is currently refining the definition of expected competence for each of the priority topics using the Key Feature approach. The emphasis on specific competencies that are predictive of overall competence will facilitate the development of efficient and effective assessment strategies.

FIGURE 1b.

Frequencies of citations by generic skill

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Travel associated with this study was funded by The College of Family Physicians of Canada.

APPENDICES

Appendix 1. Survey Questionnaire

The first exercise is to respond to the following five questions about competence in your domain of interest, and to provide us with some basic demographic information. The latter will not be used for identification purposes, but simply to know what is the range of the overall practice profiles of all respondents.

The First Exercise

Certain elements in any domain of interest are more important to achieving/demonstrating clinical competence than others. The following five questions represent an attempt to begin to identify those elements most important to defining competence in your domain of interest, Care of the Elderly. Please answer each question independently, using the terminology with which you are most comfortable and which seems to you to be most appropriate.

We suggest that you read through all the questions and information before starting to answer. Do not be concerned if there appears to be some overlap between the questions - we are asking related questions in different ways so some overlap is inevitable.

The questionnaire should take only about 60 minutes to answer once you have reflected sufficiently on all the issues.

Some very important considerations:

The questions are being asked with reference to a practitioner who is a family physician with enhanced skills in the domain of Care of the Elderly (COE), at the start of their independent practice in this domain of interest. You must set aside your own practice profile, “put on the hat” of a family physician practitioner with enhanced skills in the domain of COE, and answer the questions from this point of view.

Base your answers only on your own experience, and do not consult any references or colleagues at this time, nor refer to previous work you may have done (these steps will come later).

We often think of assessment in terms of examination and testing instruments. You should not to do this, so give your answers as though you were not at all limited by possible future testing formats. This will come later.

We have intentionally allowed you a very limited number of responses to each question, so do not be frustrated by this, even though it may force you to make some difficult choices at this time. Do the best you can, and rest assured that the multiple sources of input and the multiple iterations will more than compensate for these individual limits while permitting us to really hone it on what is important for the determination of competence in HCOE

Question 1. Patient problems and clinical situations to be dealt with: (10 responses)

List the most important problems or clinical situations that a family physician with enhanced skills in COE should be competent to resolve or deal with, at the beginning of their independent practice.

List 10 problems or situations in the box below. Use one line per answer (i.e. change lines between answers).

Question 2. Decision-making and judgment: (5 responses)

List the five most important elements of decision-making (clinical or otherwise) and judgement that you would consider help to distinguish the competent from the not yet competent family physician with enhanced skills in COE, at the beginning of independent practice.

List 5 elements. Use one line per answer (i.e., change lines between answers).

Question 3. Other qualities or behaviours: (5 responses)

List five other qualities, behaviours or skills that are important elements of competence for the family physician with enhanced skills in COE, at the beginning of independent practice.

Question 4. Problem areas: (5 responses)

Please list five to ten problems or situations in which newly practicing family physician with enhanced skills in COE have the most difficulty performing competently. Your list can include non-clinical aspects of practice.

Question 5. Do you have any other questions or comments or contributions at this time? Please use one line per comment or question.

Demographic Questions

| Please leave the one best answer for each question, and erase the others | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Gender | F | M | |

| 2. | Region (where practicing) | Atlantic (NB, PEI, NS, NF) Quebec Ontario West and North (Manitoba to BC, Territories, Nunavut) |

||

| 3. | Location of practice (use your own definition: pick only one) | Rural | Urban | |

| 4. | Years in practice | less than 10 years | more than 10 yrs | |

| 5. | Breadth of practice Broad: the majority of your practice deals with the broad spectrum of family medicine; Focused: practice restricted to HOE; Mixed: significant time in both |

Broad | Mixed | Focused |

| 6. | Teaching or not Teaching: you have had at least one learner in family medicine in a structured program in your practice setting for four or more (≥4) weeks (total, not necessarily consecutive) in the past year. |

Teaching | Non-teaching | |

| 7. | Program director (or equivalent) in COE | Yes | No | |

| 8. | Other important descriptor (write in): _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ |

|||

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

The authors declare that no conflicts of interest exist.

REFERENCES

- 1.Statistics Canada. Seniors in Canada 2001. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Statistics Canada. The Canadian Population in 2011: Age and Sex. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2011. Available from: http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/as-sa/98-311-x/98-311-x2011001-eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reuben DB, Zwanziger J, Bradley TB, et al. How many physicians will be needed to provide medical care for older persons? Physician manpower needs for the twenty-first century. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41(4):444–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb06955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mold JW, Mehr DR, Kvale JN, et al. The importance of geriatrics to family medicine: a position paper by the Group on Geriatric Education of the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. Fam Med. 1995;27(4):234–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roos NP, Shapiro E. The Manitoba longitudinal study on aging: preliminary findings on health care utilization by the elderly. Med Care. 1981;19(6):644–57. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198106000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frank C, Seguin R. Care of the elderly training: implications for family medicine. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55(5):510–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited. Healthcare Strategies for an Aging Society. New York, NY: The Economist & PHILIPS; 2009. Available from: http://graphics.eiu.com/upload/eb/Philips_Healthcare_ageing_3011WEB.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.The College of Family Physicians of Canada. Specific Standards for Family Medicine Residency Training Programs Accredited by the College of Family Physicians of Canada. Mississauga, ON: The College; 2016. Available from: http://www.cfpc.ca/uploadedFiles/Red%20Book%20English.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oandasan I, Saucier D, editors. Triple C Competency-based Curriculum Report—Part 2: Advancing implementation. Mississauga, ON: The College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schon DA. Educating the Reflective Practitioner: Toward a New Design for Teaching and Learning in the Professions. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Inc. Publishers; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams BC, Warshaw G, Fabiny AR, et al. Medicine in the 21st century: recommended essential geriatrics competencies for internal medicine and family medicine residents. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2(3):373–83. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-10-00065.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charles L, Triscott JA, Dobbs BM, et al. Geriatric core competencies for family medicine curriculum and enhanced skills: care of elderly. CGJ. 2014;17(2):53–62. doi: 10.5770/cgj.17.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kane MT. The assessment of professional competence. Eval Health Prof. 1992;15(2):163–82. doi: 10.1177/016327879201500203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bordage G, Page G. An alternative approach to PMP’s: the “key features” concept. In: Hart IR, Harden RM, editors. Further Developments in Assessing Clinical Competence. Montreal, QC: Can-Heal; 1987. pp. 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allen T, Brailovsky C, Rainsberry P, et al. Defining competency-based evaluation objectives in family medicine: dimensions of competence and priority topics for assessment. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57(9):e331–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lawrence K, Allen T, Brailovsky C, et al. Defining competency-based evaluation objectives in family medicine: key-feature approach. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57(10):e373–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donoff M, Lawrence K, Allen T, et al. Defining competency-based evaluation objectives in family medicine: professionalism. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58(10):e596–604. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laughlin T, Wetmore S, Allen T, et al. Defining competency-based evaluation objectives in family medicine: communication skills. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58(4):e217–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wetmore S, Laughlin T, Lawrence K, et al. Defining competency-based evaluation objectives in family medicine: procedure skills. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58(7):775–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soto AC. A report prepared for the Medical Council of Canada. Ottawa: The Council; 2011. Practice Analysis Studies: A Literature Review of Definitions, Concepts, Features, and Methodologies. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Newman LS, Slaughter RC, Taranath SN. The selection and use of rating scales in task surveys: A review of current job analysis practice; Presented at the Annual meeting of the National Council of Measurement in Education; Montreal, QC. 1999; Philadelphia, PA: The National Council; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 22.D’Costa A. The validity of credentialing examinations. Eval Health Prof. 1986;9(2):137–69. doi: 10.1177/016327878600900202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raymond MR. A practical guide to practice analysis for credentialing examinations. Educ Meas–Issues Pra. 2002;21(3):25–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-3992.2002.tb00097.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Section for Enhancing Geriatric Understanding and Expertise Among Surgical and Medical Specialists (SEGUE) and the AGS. Retooling for an aging America: building the healthcare workforce. A white paper regarding implementation of recommendation 4.2 of this Institute of Medicine Report of April 14, 2008, that “All licensure, certification and maintenance of certification for healthcare professionals should include demonstration of competence in care of older adults as a criterion”. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(8):1537–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parks SM, Harper GM, Fernandez H, et al. American Geriatrics Society/Association of Directors of Geriatric Academic Programs curricular milestones for graduating geriatric fellows. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(5):930–35. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boulkedid R, Abdoul H, Loustau M, et al. Using and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: a systematic review. PloS One. 2011;6(6):e20476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Epstein RM, Hundert EM. Defining and assessing professional competence. JAMA. 2002;287(2):226–35. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]