Abstract

Background

Few studies reported the outcomes of minimally invasive esophagectomy (MIE) in treating patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (nCRT). The aim of the study was to investigate the feasibility and efficacy of nCRT plus MIE (RM) strategy in treating locally advanced resectable ESCC.

Methods

This retrospective study included 175 patients with ESCC undergoing surgical resection after neoadjuvant therapy in our institution from 2010 to 2016. Patients were stratified into three groups: RM, [neoadjuvant chemotherapy (nCT) plus MIE] (CM) and [nCT plus open esophagectomy (OE)] (CO).

Results

Seventy-six (43.4%), 42 (24%) and 57 (32.6%) patients received RM, CM and CO approach, respectively. Compared with CO approach, RM or CM approach had shorter operation duration (188±39, 185±37 vs. 209±45 minutes, P=0.004, P=0.009) and less blood loss (124±88, 122±79 vs. 166±92 mL, P=0.001, P=0.003). There was a trend with lower risk of postoperative non-surgical complications in RM and CM approach [odds ratio (OR) 0.45, 0.200–1.040; P=0.062; OR 0.41, 0.150–1.160; P=0.093]. There were no differences in 30- and 90-day mortality among all groups. RM approach was more likely to achieve pathological complete regression (27.6% vs. 4.8%, 1.8%, P=0.001, P=0.001) and fewer lymph node metastasis (25.0% vs. 57.1%, 61.4%, P=0.001, P=0.001) than CM or CO approach. Survival analysis revealed a potential trend towards improved overall survival in RM approach compared with CM or CO approach (P=0.098, P=0.166).

Conclusions

RM approach was a safe and efficient strategy in treating locally advanced resectable ESCC.

Keywords: Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (nCRT), minimally invasive esophagectomy (MIE), complications, survival

Introduction

Neoadjuvant therapy, both neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (nCRT) and neoadjuvant chemotherapy (nCT), has been proved to improve survival for patients with esophageal cancer. A landmark supporting nCRT in treatment of locally advanced esophageal cancer was the CROSS trial performed by van Hagen et al. (1), which showed better R0 rate, lower node-positive rate and longer survival without increasing severe postoperative morbidity and mortality. However, accumulating evidences suggested nCRT may result in higher incidence of postoperative mortality for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) (2,3). Thereafter, nCT, a safe approach (3-6) showing improved survival compared with surgery alone, is being applied as the standard approach for ESCC in the east.

As is known to all, minimally invasive esophagectomy (MIE) had great advantages in improving short-term outcomes without compromised long-term survival (7-9). Recently, it is also demonstrated MIE is an acceptable surgical therapy for advanced-stage esophageal malignancies after nCRT (10-13). Nevertheless, the studies available included majorities of patients with adenocarcinoma located in the distal esophagus, which might be more favourable for MIE. As for locally advanced bulky ESCC, it is dangerous to resect as is mainly located in upper or middle-third of esophagus and closely adjacent to the tracheobronchial tree. The safety of MIE after neoadjuvant therapy in treating such patients has never been evaluated in a relative large sample size. Moreover, as patients with ESCC suffered from high incidence of postoperative mortality after nCRT, it is worthwhile to investigate whether MIE could lower the risk of mortality after neoadjuvant therapy, whether nCRT plus MIE (RM) approach could be rendered as a safe and efficient approach for locally advanced ESCC.

This retrospective study was performed to compare outcomes in patients with locally advanced resectable ESCC undergoing RM, nCT plus MIE (CM) or [nCT plus open esophagectomy (OE)] (CO) approach and aims to illustrate the value of RM approach in treatment of locally advanced resectable ESCC.

Methods

Patients

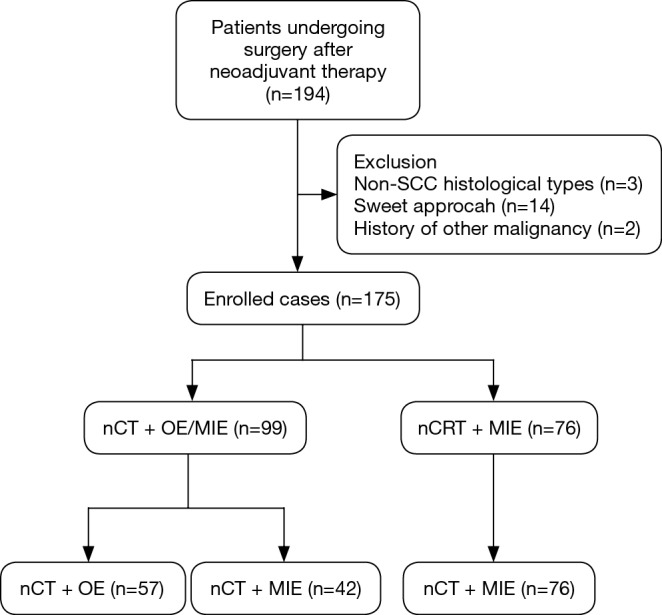

Between January 2010 to December 2016, patients completing neoadjuvant therapy followed by esophagectomy (n=194) were selected and their medical records were reviewed. The inclusion criteria were (I) thoracic ESCC; (II) McKeown or (III) Ivor-Lewis approach, no history of concomitant or previous malignancy. Therefore, 175 patients were eligible for analysis. The flow chart was shown in Figure 1. Pretreatment examinations, including endoscopy with biopsies, thoracoabdominal enhanced computed tomography (CT), cervical ultrasonography, endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) and/or positron emission tomography (PET) were used to determine the clinical stage. Patients were evaluated in a multidisciplinary procedure and those with locally advanced resectable carcinoma (clinical stage T3/T4a, any N) were considered for neoadjuvant therapy in our institution. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhongshan Hospital of Fudan University (No. 2017236) and informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Figure 1.

The flow diagram. SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; nCT, neoadjuvant chemotherapy; nCRT, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy; MIE, minimally invasive esophagectomy; OE, open esophagectomy.

Treatment

nCRT

nCRT was based on the CROSS regimen (1). Radiotherapy with 40 Gy was delivered in 20 fractions with 2 Gy per time on days 1–5, days 8–12, days 15–19 and days 22–26. Chemotherapy consisted of 4 cycles of carboplatin [2 mg/mL/min area under the curve (AUC)] and paclitaxel 50 mg/m2 on day 6, 13, 20, 27.

nCT

NCT comprised 2 cycles of chemotherapy with cisplatin 75 mg/m2 or oxaliplatin 130 mg/m2 plus paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 every 3 weeks.

Surgery

Patients were evaluated and scheduled for surgery if they were medically suitable for esophagectomy 4–6 weeks after the completion of neoadjuvant therapy. The operation was performed using an open or minimally invasive approach. Any surgery with thoracotomy was identified as OE approach, the other as MIE. Decisions regarding the type of surgery administered were left to the discretion of the surgeon. MIE was administrated in 2004 in our department. Surgeons were well experienced in MIE. The detailed procedure of MIE was described in previous literature (14). More specifically, McKeown procedure was used for upper, middle or lower esophageal tumors, and Ivor-Lewis procedure for middle or lower tumors. If tumor is located in upper third of the esophagus, cervical lymph nodes must be dissected. All patients received at least two-field lymphadenectomy and en bloc dissection of regional lymph node was performed, including the paraesophageal, paratracheal, right tracheobronchial, subcarinal, pulmonary ligament, diaphragmatic, and paracardial, as well as those located along the lesser gastric curvature, the origin of the left gastric artery, the common hepatic artery, and the splenic artery. The histological diagnosis was determined by the World Health Organization classifications. Pathological staging was performed according to the latest ypTNM classification (8th edition) of the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC, 2017) (15).

Follow-up

The medical records were used to collect demographic data, tumor information and hospital courses. The classification of complications was recorded according to International Consensus of Esophagectomy Complications Consensus Group (ECCG) (16) and the severity of complications was classified according to the Clavien-Dindo scoring system (17). Follow-up visits were carried out every 3 months in the first 2 years and every 6 months in the following years. Follow-up was terminated in December 31st, 2016 and two patients were lost to follow up.

Statistical analysis

The SPSS 23.0 software was used for data analysis. Categorical variables in any two groups were compared by χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test and continuous variables by Mann-Whitney U test. Logistic regression was used to compare various complication rates between any two groups and adjusted by potential confounding effects of covariates [age, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade, clinical T stage (cT), clinical N stage (cN), tumor location]. Overall survival was analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test in 80 patients following up for at least 3 years. The significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

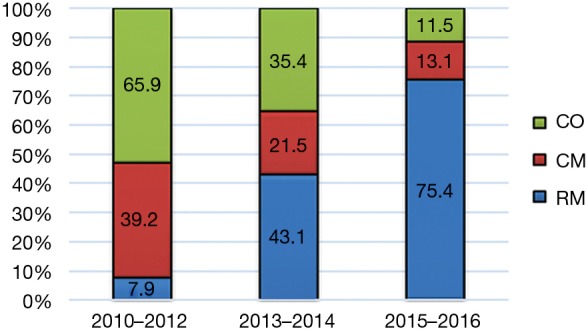

The study included 175 patients with ESCC undergoing surgery after neoadjuvant therapy (flow chart shown in Figure 1). RM approach was given to 76 patients (43.4%) and the other 99 patients (56.6%) received nCT, including 42 patients (24%) undergoing MIE (CM group) and 57 patients (32.6%) undergoing OE (CO group). Sixty-eight patients (89.5%) in the RM group completed the planning neoadjuvant scheme, while 36 (85.7%) and 50 (87.7%) in the CM and CO groups, respectively. The overall postoperative morbidity rate was 44.5%, and the 30- and 90-day mortality rates were 1.71% and 2.86%, respectively. It was shown that CO and CM approach was practiced more frequently in the early years, whereas RM increased over time. In the last 2 years, RM accounted for 75.4% in Figure 2. The median follow-up time was 19, 43, and 44 months in RM, CM, CO group, respectively. The overall 1-, 3- and 5-year survival rate was 81%, 53.8% and 36.7%, respectively.

Figure 2.

Ratios of surgical approaches for different time periods. CO, nCT + OE; CM, nCT + MIE; RM, nCRT + MIE; nCT, neoadjuvant chemotherapy; nCRT, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy; MIE, minimally invasive esophagectomy; OE, open esophagectomy.

RM vs. CM

Patients in the RM and CM groups were comparable in demographic data (Table 1). There were no differences in operative features, severe toxic effects and various classifications of postoperative complications (Table 2). Logistic regression analysis of surgical and non-surgical complications, as well as severe complications (Clavien-Dindo IIIb or higher), did not significantly differ between these two groups (Table 3). There were no significant differences in 30- and 90-day mortality.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics according to preoperative treatment.

| Variables | nCRT + MIE (RM) (N=76) |

nCT + MIE (CM) (N=42) |

nCT + OE (CO) (N=57) |

P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RM vs. CM | RM vs. CO | CM vs. CO | |||||

| Median year of treatment | 2015 | 2013 | 2013 | − | − | − | |

| Median follow-up [range, months] | 19 [1–79] | 43 [3–73] | 44 [1–81] | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.623 | |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.443 | 0.380 | 0.135 | ||||

| Male | 64 (84.2) | 33 (78.6) | 51 (89.5) | ||||

| Female | 12 (15.8) | 9 (21.4) | 6 (10.5) | ||||

| Age (years) | 0.932 | 0.582 | 0.579 | ||||

| ≤60, n (%) | 35 (46.1) | 19 (45.2) | 29 (50.9) | ||||

| >60, n (%) | 41 (53.9) | 23 (54.8) | 28 (49.1) | ||||

| Median [range] | 61 [44–79] | 61 [46–73] | 60 [41–73] | ||||

| Smoking history, n (%) | 0.237 | 0.912 | 0.223 | ||||

| Yes | 22 (28.9) | 8 (19.0) | 17 (29.8) | ||||

| No | 54 (71.1) | 34 (81.0) | 40 (70.2) | ||||

| Drinking history, n (%) | 0.356 | 0.898 | 0.323 | ||||

| Yes | 14 (18.4) | 5 (11.9) | 11 (19.3) | ||||

| No | 62 (81.6) | 37 (88.1) | 46 (80.7) | ||||

| ASA grade, n (%) | 0.989 | 0.881 | 0.932 | ||||

| I | 24 (31.6) | 13 (30.9) | 19 (33.3) | ||||

| II | 48 (63.2) | 27 (64.3) | 36 (63.2) | ||||

| III | 4 (5.2) | 2 (4.8) | 2 (3.5) | ||||

| Tumor location, n (%) | 0.923 | 0.334 | 0.637 | ||||

| Upper | 13 (17.1) | 6 (14.3) | 5 (8.8) | ||||

| Middle | 44 (57.9) | 25 (59.5) | 34 (59.6) | ||||

| Lower | 19 (25.0) | 11 (26.2) | 18 (31.6) | ||||

| Clinical T stage, n (%) | 0.602 | 0.716 | 0.856 | ||||

| cT3 | 47 (61.8) | 28 (66.7) | 37 (64.9) | ||||

| cT4a | 29 (38.2) | 14 (33.3) | 20 (35.1) | ||||

| Clinical N stage, n (%) | 0.497 | 0.545 | 0.246 | ||||

| N0 | 32 (42.1) | 15 (35.7) | 27 (47.4) | ||||

| N+ | 44 (57.9) | 27 (64.3) | 30 (52.6) | ||||

nCT, neoadjuvant chemotherapy; nCRT, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy; MIE, minimally invasive esophagectomy; OE, open esophagectomy.

Table 2. Toxicity, intraoperative and postoperative events according to preoperative treatment.

| Variables | nCRT + MIE (RM) (N=76) |

nCT + MIE (CM) (N=42) |

nCT + OE (CO) (N=57) |

P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RM vs. CM | RM vs. CO | CM vs. CO | |||||

| Toxicity of grade ≥3 in neoadjuvant phase, n (%) | |||||||

| Leukopenia/thrombocytopenia | 5 (6.6) | 3 (7.1) | 3 (5.3) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | 4 (5.3) | 3 (7.1) | 5 (8.8) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| Liver/renal disorder | 1 (1.3) | 1 (2.4) | 0 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| pneumonia | 1 (1.3) | 0 | 0 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| Operative features | |||||||

| Operation time (min) | 188±39 | 185±37 | 209±45 | 0.763 | 0.004 | 0.009 | |

| Blood loss (mL) | 124±88 | 122±79 | 166±92 | 0.645 | 0.001 | 0.003 | |

| Length of stay (days) | |||||||

| ICU median [range] | 2 [0–15] | 2 [0–16] | 2 [0–24] | 0.833 | 0.414 | 0.534 | |

| Hospital median [range] | 10 [8–96] | 11 [7–78] | 11 [8–95] | 0.679 | 0.350 | 0.858 | |

| Complications | |||||||

| Total complications, n (%) | 33 (43.4) | 19 (45.2) | 26 (45.6) | 0.849 | 0.801 | 0.970 | |

| Surgical complication, n (%) | 19 (25.0) | 12 (28.6) | 10 (17.5) | 0.673 | 0.303 | 0.192 | |

| Non-surgical complication, n (%) | 14 (18.4) | 7 (16.7) | 18 (31.6) | 0.811 | 0.079 | 0.091 | |

| Clavien-Dindo grade IIIb or higher, n (%) | 11 (14.5) | 6 (14.3) | 12 (21.1) | 0.978 | 0.321 | 0.388 | |

| Median Clavien-Dindo | IIIa | IIIa | IIIa | 0.859 | 0.463 | 0.498 | |

| Respiratory complications, n (%) | 9 (11.8) | 4 (9.5) | 11(19.3) | 0.769 | 0.234 | 0.180 | |

| Cardiac complications, n (%) | 4 (5.3) | 2 (4.8) | 3 (5.3) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| Anastomotic leakage, n (%) | 16 (21.1) | 10 (23.8) | 9 (15.8) | 0.729 | 0.442 | 0.317 | |

| Delayed conduit emptying, n (%) | 2 (2.6) | 1 (2.4) | 1 (1.8) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| Recurrent nerve palsy, n (%) | 2 (2.6) | 1 (2.4) | 1 (1.8) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| Wound infection, n (%) | 4 (5.3) | 2 (4.8) | 5 (8.8) | 1.000 | 0.497 | 0.695 | |

| Chyle leak, n (%) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (2.4) | 0 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| 30-day mortality, n (%) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (2.4) | 1 (1.8) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| 90-day mortality, n (%) | 2 (3.6) | 1 (2.4) | 2 (3.5) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

nCT, neoadjuvant chemotherapy; nCRT, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy; MIE, minimally invasive esophagectomy; OE, open esophagectomy; ICU, intensive care unit.

Table 3. Logistic regression analysis of complications and postoperative mortality.

| Variables | Odds ratio (95%CI)a (RM vs. CO) |

Odds ratio (95%CI)a (CM vs. CO) |

Odds ratio (95%CI)a (RM vs. CM) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO | RM | CO | CM | CM | RM | |||

| Surgical complications | 1 (reference) | 1.44 (0.600–3.450) | 1 (reference) | 1.73 (0.650–4.610) | 1 (reference) | 0.82 (0.350–1.940) | ||

| Nonsurgical complications | 1 (reference) | 0.45 (0.200–1.040) | 1 (reference) | 0.41 (0.150–1.160) | 1 (reference) | 1.06 (0.380–2.950) | ||

| Clavien-Dindo grade IIIb or higher | 1 (reference) | 0.54 (0.210–1.413) | 1 (reference) | 0.53 (0.170–1.670) | 1 (reference) | 1.00 (0.330–3.110) | ||

| 90-day mortality | 1 (reference) | 0.69 (0.090–5.470) | 1 (reference) | 0.53 (0.040–6.980) | 1 (reference) | 1.13 (0.100–13.080) | ||

a, adjusted for age, ASA grade, cT, cN and tumor location. nCT, neoadjuvant chemotherapy; nCRT, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy; MIE, minimally invasive esophagectomy; OE, open esophagectomy; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; cT, clinical T stage; cN, clinical N stage.

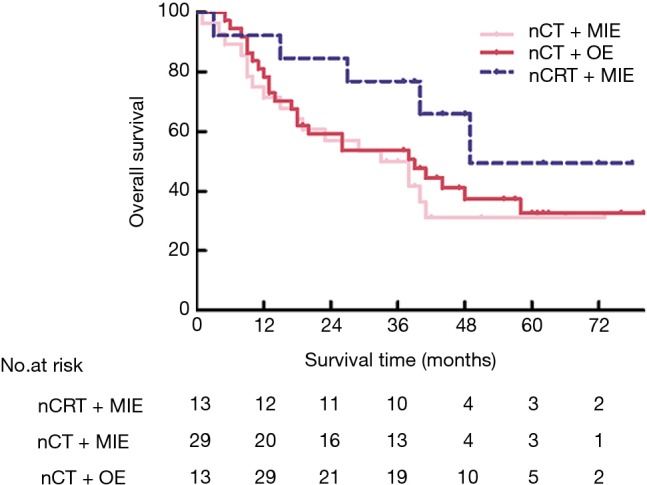

The results of pathologic examination of resected specimens were shown in Table 4. There was no statistically difference in R0 resection rates. The histological complete response was achieved in 21 patients (27.6%) in the RM group vs. 2 (4.8%) in the CM group (P=0.001). As for lymph node metastasis, 19 (25%) had lymph node metastases in the RM group vs. 24 (57.1%) in the CM group (P=0.001). Therefore, the RM group had a significant greater proportion of patients with lower ypStage (P=0.001). Additionally, there was a lower trend of lymphovascular/neural invasion in the RM group (P=0.047). Of note, more lymph nodes were harvested in the CM group than those in the RM group (P=0.005) though dissected stations were similar. The 3-year survival rate in RM group appeared to be improved (76.9% vs. 44.8%, P=0.067). The Kaplan-Meier and log-rank analyses showed potential overall survival benefits in patients following up for at least 3 years (P=0.098) shown in Figure 3.

Table 4. Pathological staging and survival of patients according to preoperative treatment.

| Variables | nCRT + MIE (RM) (N=76) |

nCT + MIE (CM) (N=42) |

nCT + OE (CO) (N=57) |

P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RM vs. CM | RM vs. CO | CM vs. CO | |||||

| R0 resection, n (%) | 71 (93.4) | 39 (92.9) | 54 (94.7) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.696 | |

| Tumor regression grade, n (%) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.688 | ||||

| 1: histological complete response | 21 (27.6) | 2 (4.8) | 1 (1.8) | ||||

| 2: 1–10% tumor cells | 22 (28.9) | 4 (9.5) | 9 (15.8) | ||||

| 3: >10–50% tumor cells | 13 (17.1) | 3 (7.1) | 4 (7.0) | ||||

| 4: >50% tumor cells | 20 (26.3) | 33 (78.6) | 43 (75.4) | ||||

| Lymph node metastasis | 19 (25.0) | 24 (57.1) | 35 (61.4) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.669 | |

| ypT0N0M0, n (%) | 19 (25.0) | 2 (4.8) | 1 (1.8) | 0.006 | 0.001 | 0.573 | |

| ypStage, n (%) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.801 | ||||

| ypStage I | 47 (61.8) | 7 (16.7) | 10 (17.5) | ||||

| ypStage II | 8 (10.5) | 10 (23.8) | 11 (19.3) | ||||

| ypStage III | 18 (23.7) | 21 (50.0) | 27 (47.4) | ||||

| ypStage IV | 3 (3.9) | 4 (9.5) | 9 (15.8) | ||||

| Lymphovascular/neural invasion, n (%) | 9 (11.8) | 11 (26.2) | 13 (22.8) | 0.047 | 0.092 | 0.698 | |

| Number of node harvested median | 23 | 27 | 23 | 0.005 | 0.095 | 0.309 | |

nCT, neoadjuvant chemotherapy; nCRT, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy; MIE, minimally invasive esophagectomy; OE, open esophagectomy.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier plot of overall survival according to treatment group in those following up for at least 3 years. P=0.098 (nCRT + MIE alone vs. nCT + OE), P=0.166 (nCRT + MIE vs. nCT + MIE), P=0.652 (nCT + OE vs. nCT + MIE) (log rank test). nCT, neoadjuvant chemotherapy; nCRT, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy; MIE, minimally invasive esophagectomy; OE, open esophagectomy.

RM vs. CO

Baseline characteristics were similar between the RM and CO groups (Table 1). There were no differences in the severe toxic effects, but the RM group had a significant reduction in the surgery time (P=0.004) and intraoperative blood loss (P=0.001) compared with the CO group. There was a tendency that patients in the RM group were less likely to have non-surgical complications than those in the CO group (P=0.079) (Table 2). The adjusted odds ratio (OR) for non-surgical complications in the RM group was 0.45 (95% CI: 0.200–1.040; P=0.062), also revealing its potential to lower the risk of such complications (Table 3). No differences were detected in 30- and 90-day mortality.

The pathological differences between these two groups were similar to that between RM and CM groups (Table 4). The RM group, compared with the CO group, had a greater proportion of patients with histological complete response (27.6% vs. 1.8%, P=0.001) and a lower percentage in lymph-node metastases (25% vs. 61.4%, P=0.001) as well as a higher proportion of early ypStages (P=0.001). No statistically significant difference was noted in rates of R0 resection. In addition, more lymph nodes also tend to be harvested (P=0.095). The 3-year survival rate was 76.9% and 50% in the RM and CO group, respectively (P=0.108). A trend towards improved overall survival in RM approach was observed in Figure 3, but no statistically significance (P=0.166).

CM vs. CO

There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between the two groups (Table 1). Operation time was shorter (P=0.009) and intraoperative blood loss was lower (P=0.003) in the CM group. The CM group had a lower tendency to occur non-surgical complications (P=0.091) (Table 2). Logistic regression analysis also revealed the same trend (adjusted OR 0.41; 95% CI: 0.150–1.160; P=0.093) (Table 3). Additionally, there were no significant differences in 30- and 90-day mortality.

These two groups received nCT treatment, so the pathology was similar and had no differences statistically (Table 4). The overall survival was also comparable shown in Figure 3.

Discussion

This present study was the first available analysis investigating values of MIE specifically for locally advanced resectable ESCC after nCRT. It showed RM approach significantly improved pathological regression rate, increased lymph-node negative rate and decreased lymphovascular/neural invasion rate compared with nCT approach. Short-term outcome analysis indicated RM approach did not increase the incidence and severity of morbidity and mortality compared with CM approach, what’s more, it had potential to reduce the incidence of non-surgical complications compared with CO approach. As for long-term outcomes, it displayed the potential of improving survival compared with the other two approaches in patients following up for at least 3 years. Therefore, RM approach might be a superior approach for locally advanced ESCC.

Multidisciplinary synthetic therapy, especially neoadjuvant therapy, is strongly recommended by clinical practice guidelines for the management of esophageal cancer (18). Although nCRT was the primary procedure in western world, nCT was the mainstream in eastern world due to nCRT’s high risk of postoperative mortality for ESCC, which may couteract its long-term survival benefits (2,3,19,20). Studies directly comparing the outcomes of nCRT with nCT were also performed. A retrospective study (21) showed a higher rate of postoperative morbidity and mortality in the nCRT group and Klevebro et al. (22) revealed higher severity grade of complications in the nCRT group. Nowadays, MIE has been demonstrated to be a feasible surgical procedure for advanced-stage esophageal malignancies after neoadjuvant therapy (11-13), but the studies available included majorities of patients with adenocarcinoma located in the distal esophagus, which might be more favourable for MIE. As for ESCC, due to its location in upper or middle-third of esophagus and closely adjacent to the tracheobronchial tree, it is dangerous to resect by MIE. Moreover, ESCC is quite different from esophageal adenocarcinoma in terms of biological behavior, and prognosis. Therefore, the issue whether the combination of nCRT with MIE could be a safe and efficient approach for locally advanced ESCC need investigating. In our study, MIE had advantages in reducing non-surgical complications compared with OE after neoadjuvant therapy. Additionally, there was no significant difference in the incidence of morbidity and mortality by neoadjuvant therapy type after MIE involving and the severity of complications was also comparable. RM approach was a safe option for locally advanced ESCC, which was consistent with the conclusion from previous studies mainly focusing on esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Previous studies have found that nCRT improved pathological complete response (pCR) rate and reduced lymph node metastases rate when compared to nCT (21,23-25). The latest NeoRes trial (26) also confirmed the outcomes in ESCC subgroups. The subgroup analysis for patients with ESCC showed nCRT achieved a higher pCR rate of 42% and lower metastatic rate of 25%, while nCT achieved 16% and 53%, respectively, which was consistent with our outcomes. In addition, ESCC was more likely to achieve an early ypTNM stage than adenocarcinoma by nCRT approach.

In the present study, fewer lymph nodes were harvested after nCRT than nCT, despite no difference in dissected regions. In other trials, lymph node retrieval after nCRT also appeared to be lower (1,20,27). Besides, it was reported that chemoradiotherapy reduced lymph node harvest from within the radiotherapy field in rectal cancer (28,29).

Most previous studies revealed nCRT was not associated with improved survival in spite of its apparent elevated pCR rate compared with nCT (3,20,21,25). It was worth mentioning that nCRT group carried an increased risk of postoperative mortality or had more deaths unrelated to disease progression in the first-year follow up period in these studies. Consequently, the reason of absence of a corresponding advantage in overall survival was assumed to be that the combined impact of chemotherapy and radiotherapy as well as open surgery took a heavy toll by significantly increasing deaths by serious adverse events during the first year after surgery. In our study, although there was no significant difference in overall survival, a trend towards improved survival in the RM group could been seen in patients following up for at least 3 years. A recent RCT also revealed and confirmed the potential of superior survival in the ESCC patients who received nCRT (26). In our view, the failure of achieving significantly better survival was due to the small sample size, but the results were also helpful, indicating that MIE had great advantages in reducing treatment-related deaths, and maybe a key factor accounting for our results.

Neoadjuvant strategies differ across the world. The nCRT regimen used in our study comprised 4 cycles of chemotherapy with carboplatin/paclitaxel and concurrent radiation with a total of 40 Gy. It was modified according to the CROSS trail (1) and showed improved overall survival compared with other nCRT regimens (30). Other chemotherapeutic agents, such as platinum and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and radiation dose ranging from 18.5 to 45 Gy (19,31,32) were also administered in other medical centers. Although cisplatin and 5-FU still remain the most well-documented chemotherapeutic regimen choices in nCT (5,23,33), our nCT regimen of paclitaxel plus cisplatin (TP) was widely applied in China and demonstrated to be an effective treatment strategy for ESCC (34). No agreement has been reached about neoadjuvant strategy, so further studies need to find a regimen with decreased risk of adverse events and better survival.

In this study, decisions regarding the type of treatment administered were left to the discretion of the treating thoracic surgeons. MIE was administrated in 2004 in our department, and has become the mainstream therapeutic approach in patients with or without neoadjuvant therapy due to its advantages in reducing trauma nowadays. Similarly, in the early days, nCT was the predominant option, but it had poor pathological regression rates. Therefore, we began to use nCRT as induction therapy approach with the combination of MIE, and it exhibited high pathological regression rates with mild complications, so RM approach has become the mainstream for locally advanced esophageal cancer in our department in recent years.

The present study also had limitations. It was a relative small retrospective case series. The enrolled patients were not randomly assigned, resulting in potential selection bias. A small proportion of patient had developed metastatic or T4b disease progression after neoadjuvant therapy, so they received definitive chemoradiotherapy instead of surgery and the study did not enroll these cases for analysis. Besides, the follow-up time of some patients didn’t reach 3 years, so the overall survival analysis was carried out only in a small number. To compensate for that, we will continue our follow-up to confirm our conclusion. On the other hand, our group has launched CMISG1701 trial (NCT03001596). This trial is a multicenter prospective randomized trial investigating the safety and efficacy of RM in patients with locally advanced resectable ESCC (cT3–4aN0–1M0) compared with CM. We hope to obtain valid information that RM strategy has superior benefits for the curative treatment of ESCC.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that MIE could offer better perioperative outcomes to patients with locally advanced ESCC after neoadjuvant therapy. nCRT followed by MIE approach not only increased histological complete response rate and decreased lymph-node metastases rate, but also showed potential in improving overall survival without increasing the incidence and severity of postoperative morbidity and mortality. RM approach was a safe and efficient strategy in treating patients with locally advanced resectable ESCC.

Acknowledgements

Funding: This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81400681), Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (No. 16411965900) and Zhongshan Hospital (No. 2016ZSLC15).

Ethical Statement: The study was approved by the ethic committee of Zhongshan Hospital of Fudan University (No. 2017236) and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.van Hagen P, Hulshof MC, van Lanschot JJ, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for esophageal or junctional cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;366:2074-84. 10.1056/NEJMoa1112088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mariette C, Dahan L, Mornex F, et al. Surgery alone versus chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery for stage I and II esophageal cancer: final analysis of randomized controlled phase III trial FFCD 9901. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:2416-22. 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.6532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumagai K, Rouvelas I, Tsai JA, et al. Meta-analysis of postoperative morbidity and perioperative mortality in patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy for resectable oesophageal and gastro-oesophageal junctional cancers. Br J Surg 2014;101:321-38. 10.1002/bjs.9418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ando N, Kato H, Igaki H, et al. A randomized trial comparing postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy with cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil versus preoperative chemotherapy for localized advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the thoracic esophagus (JCOG9907). Ann Surg Oncol 2012;19:68-74. 10.1245/s10434-011-2049-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sjoquist KM, Burmeister BH, Smithers BM, et al. Survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy for resectable oesophageal carcinoma: an updated meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol 2011;12:681-92. 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70142-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baba Y, Watanabe M, Yoshida N, et al. Neoadjuvant treatment for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2014;6:121-8. 10.4251/wjgo.v6.i5.121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sihag S, Wright CD, Wain JC, et al. Comparison of perioperative outcomes following open versus minimally invasive Ivor Lewis oesophagectomy at a single, high-volume centre. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2012;42:430-7. 10.1093/ejcts/ezs031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang H, Shen Y, Feng M, et al. Outcomes, quality of life, and survival after esophagectomy for squamous cell carcinoma: A propensity score-matched comparison of operative approaches. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2015;149:1006-14; discussion 1014-5.e4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Biere SS, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Maas KW, et al. Minimally invasive versus open oesophagectomy for patients with oesophageal cancer: a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012;379:1887-92. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60516-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woodard GA, Crockard JC, Clary-Macy C, et al. Hybrid minimally invasive Ivor Lewis esophagectomy after neoadjuvant chemoradiation yields excellent long-term survival outcomes with minimal morbidity. J Surg Oncol 2016;114:838-47. 10.1002/jso.24409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bakhos C, Oyasiji T, Elmadhun N, et al. Feasibility of minimally invasive esophagectomy after neoadjuvant chemoradiation. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2014;24:688-92. 10.1089/lap.2014.0118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tapias LF, Mathisen DJ, Wright CD, et al. Outcomes With Open and Minimally Invasive Ivor Lewis Esophagectomy After Neoadjuvant Therapy. Ann Thorac Surg 2016;101:1097-103. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.09.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Warner S, Chang YH, Paripati H, et al. Outcomes of minimally invasive esophagectomy in esophageal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Ann Thorac Surg 2014;97:439-45. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.09.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shen Y, Wang H, Feng M, et al. The effect of narrowed gastric conduits on anastomotic leakage following minimally invasive oesophagectomy. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2014;19:263-8. 10.1093/icvts/ivu151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rice TW, Ishwaran H, Kelsen DP, et al. Recommendations for neoadjuvant pathologic staging (ypTNM) of cancer of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction for the 8th edition AJCC/UICC staging manuals. Dis Esophagus 2016;29:906-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Low DE, Alderson D, Cecconello I, et al. International Consensus on Standardization of Data Collection for Complications Associated With Esophagectomy: Esophagectomy Complications Consensus Group (ECCG). Ann Surg 2015;262:286-94. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 2004;240:205-13. 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ajani JA, D'Amico TA, Almhanna K, et al. Esophageal and esophagogastric junction cancers, version 1.2015. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2015;13:194-227. 10.6004/jnccn.2015.0028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bosset JF, Gignoux M, Triboulet JP, et al. Chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery compared with surgery alone in squamous-cell cancer of the esophagus. N Engl J Med 1997;337:161-7. 10.1056/NEJM199707173370304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klevebro F, Lindblad M, Johansson J, et al. Outcome of neoadjuvant therapies for cancer of the oesophagus or gastro-oesophageal junction based on a national data registry. Br J Surg 2016;103:1864-73. 10.1002/bjs.10304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luu TD, Gaur P, Force SD, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiation versus chemotherapy for patients undergoing esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 2008;85:1217-23; discussion 1223-4. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.11.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klevebro F, Johnsen G, Johnson E, et al. Morbidity and mortality after surgery for cancer of the oesophagus and gastro-oesophageal junction: A randomized clinical trial of neoadjuvant chemotherapy vs. neoadjuvant chemoradiation. Eur J Surg Oncol 2015;41:920-6. 10.1016/j.ejso.2015.03.226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burmeister BH, Thomas JM, Burmeister EA, et al. Is concurrent radiation therapy required in patients receiving preoperative chemotherapy for adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus? A randomised phase II trial. Eur J Cancer 2011;47:354-60. 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Markar SR, Noordman BJ, Mackenzie H, et al. Multimodality treatment for esophageal adenocarcinoma: multi-center propensity-score matched study. Ann Oncol 2017;28:519-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samson P, Robinson C, Bradley J, et al. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy versus Chemoradiation Prior to Esophagectomy: Impact on Rate of Complete Pathologic Response and Survival in Esophageal Cancer Patients. J Thorac Oncol 2016;11:2227-37. 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.07.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klevebro F, Alexandersson von Dobeln G, Wang N, et al. A randomized clinical trial of neoadjuvant chemotherapy versus neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for cancer of the oesophagus or gastro-oesophageal junction. Ann Oncol 2016;27:660-7. 10.1093/annonc/mdw010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stahl M, Walz MK, Stuschke M, et al. Phase III comparison of preoperative chemotherapy compared with chemoradiotherapy in patients with locally advanced adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:851-6. 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.0506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lykke J, Roikjaer O, Jess P, et al. Tumour stage and preoperative chemoradiotherapy influence the lymph node yield in stages I-III rectal cancer: results from a prospective nationwide cohort study. Colorectal Dis 2014;16:O144-9. 10.1111/codi.12521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taflampas P, Christodoulakis M, Gourtsoyianni S, et al. The effect of preoperative chemoradiotherapy on lymph node harvest after total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 2009;52:1470-4. 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181a0e6ac [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanford NN, Catalano PJ, Enzinger PC, et al. A retrospective comparison of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy regimens for locally advanced esophageal cancer. Dis Esophagus 2017;30:1-8. 10.1093/dote/dox025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burmeister BH, Smithers BM, Gebski V, et al. Surgery alone versus chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery for resectable cancer of the oesophagus: a randomised controlled phase III trial. Lancet Oncol 2005;6:659-68. 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70288-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Urba SG, Orringer MB, Turrisi A, et al. Randomized trial of preoperative chemoradiation versus surgery alone in patients with locoregional esophageal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:305-13. 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.2.305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allum WH, Stenning SP, Bancewicz J, et al. Long-term results of a randomized trial of surgery with or without preoperative chemotherapy in esophageal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:5062-7. 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.2083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zheng Y, Li Y, Liu X, et al. A phase III, multicenter randomized controlled trial of neo-adjuvant chemotherapy paclitaxel plus cisplatin versus surgery alone for stage IIA-IIIB esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Thorac Dis 2017;9:200-4. 10.21037/jtd.2017.01.44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]