Abstract

IgA secretion at mucosal sites is important for host defence against pathogens as well as maintaining the symbiosis with microorganisms present in the small intestine that affect IgA production. In the present study, we tested the ability of 5 strains of lactic acid bacteria stimulating IgA production, being Pediococcus acidilactici K15 selected as the most effective on inducing this protective immunoglobulin. We found that this response was mainly induced via IL-10, as efficiently as IL-6, secreted by K15-stimulated dendritic cells. Furthermore, bacterial RNA was largely responsible for the induction of these cytokines; double-stranded RNA was a major causative molecule for IL-6 production whereas single-stranded RNA was critical factor for IL-10 production. In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial, ingestion of K15 significantly increased the secretory IgA (sIgA) concentration in saliva compared with the basal level observed before this intervention. These results indicate that functional lactic acid bacteria induce IL-6 and IL-10 production by dendritic cells, which contribute to upregulating the sIgA concentration at mucosal sites in humans.

Introduction

A variety of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) from fermented foods or human microbiota show multiple beneficial effects on human health1–4. Recent studies revealed that probiotic strains of LAB activate the innate immune system and then activate the acquired immune system, resulting in the prevention of immune diseases5–9 and protection against bacterial and viral infection10–13. Firstly, LAB stimulate the immune system via the induction of type I interferons (IFNs)14, which play an important role in anti-viral immune responses12,13. The production of type I interferons (IFNs), particularly IFN-α and IFN-β from dendritic cells (DCs) upon LAB-stimulation were reported beneficial for exerting an anti-viral effect against influenza virus5,15,16.

Another major mechanism of LAB to improve host defence in the gut is enhancement of production in specific antibodies (Ab) against pathogens, and the overall increase in total IgA5,15,17. Antigen-specific IgA Abs neutralise viruses or toxins and interfere with the ability of pathogens to adhere to or penetrate through the mucosal epithelial barrier. Thus oral administration of probiotic LAB strains accelerates the clearance of viruses by promoting the production of virus-specific IgA at mucosal sites. In addition to antigen/pathogen-specific targeting by immunoglobulin, secretory IgA is equipped with glycan-dependent innate immunity, which protects the gut from pathogen invasion by inhibiting the adherence of diverse and variable mucosal microorganisms, i.e. their glycan-moieties compete with epithelial receptors for pathogens18. Given that both Ag-specific and non-specific IgA protect mucosal surfaces from pathogen invasion and colonization, the probiotic effect of orally administered LAB to enhance IgA production contributes to repelling pathogens5,17.

How intestinal IgA production is maintained under steady-state conditions has been intensively studied. As evidenced by the much lower levels of IgA produced in the guts of germ-free mice, commensal bacteria play a critical role19. Follicular helper T cells (Tfh) in small intestinal Peyer’s patches (PPs) that express Bcl6, PD-1, ICOS, and CXCR5 are critical cell populations for inducing IgA class-switch recombination and somatic hypermutation in germinal center B cells to produce high-affinity IgA, and this requires luminal innate immune signals20. There is also evidence that most of the IgA Abs induced by Tfh cells are specific for microbiota antigens, regulating the composition of mucosa-associated microbiota21. Furthermore, one indigenous opportunistic bacterial genus, Alcaligenes, was reported to inhabit PPs and induce local antigen-specific Ab production22. Thus, intestinal bacteria are involved in IgA production and are thought to regulate gut microbiota composition via communication with intestinal immune cells. To this end, IgA production is required for maintaining intestinal homeostasis under steady-state conditions, in addition to its obligatory task of repelling pathogens23,24.

Although how the positive and negative effects of IgA act to regulate the selection of intestinal microorganisms is obscure at present, it is clear that an abundance of IgA is required for a healthy gut environment and protective immune homeostasis25. We recently clarified that IFN-β is secreted from mDCs, uniquely, in response to LAB; we also observed that double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) in LAB was the main active component for stimulating endosomal TLRs14,26. In the present study, we investigated if this innate pathway is also important to IgA production from B cells, using human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). As being major luminal commensal bacteria in the small intestine and common components of fermented foods in human diet, LAB indeed enhanced IgA production from B cells, and importantly, via their RNA. Furthermore, for IgA production in human system IL-10 is as important as IL-6, which has been reported in murine experimental system17.

Results

IgA secretion by PBMCs in response to LAB via IL-6 and IL-10

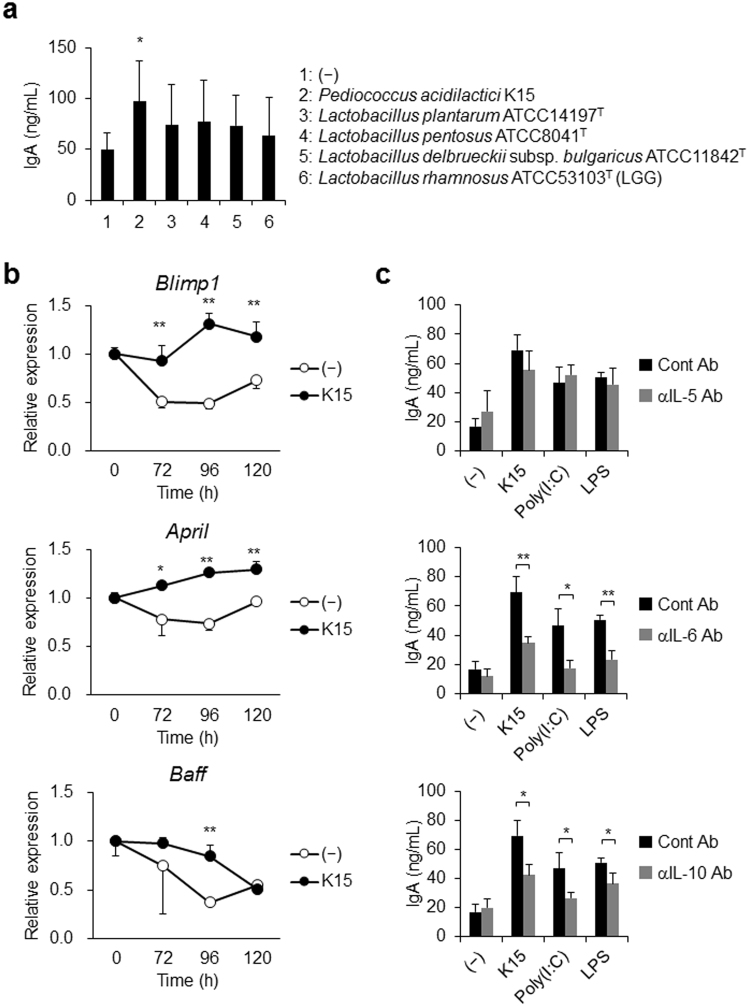

We evaluated the IgA secretion by PBMCs from 7 donors in response to some strains of LAB (described in Table S1). Among tested strains of LAB, Pediococcus acidilactici K15 significantly induced IgA production in PBMCs (Fig. 1a). The other strains of LAB failed to enhance IgA production in this experimental system (Fig. 1a). B lymphocyte-induced maturation protein 1 (Blimp-1) is a master regulator for plasma cell differentiation27, and B cell activating factor belonging to the TNF family (BAFF) and a proliferation inducing ligand (APRIL) are both known to promote this class switching28–30. In K15-stimulated PBMCs, the gene expression encoding Blimp-1 and APRIL was upregulated, whereas that encoding BAFF did not change, in comparison with unstimulated PBMCs (Fig. 1b). Reportedly, IgA secretion by B cells is activated by IL-5 or IL-6 in mouse PBMCs17,31 and by IL-6 and IL-10 in human PBMCs32. These cytokines promote the differentiation of IgA-producing plasma cells. We performed experiments in the presence of neutralizing Abs against IL-5, IL-6, and IL-10 to clarify which factor is involved in IgA production by human PBMCs in response to K15. Although a neutralizing Ab against IL-5 did not affect IgA secretion in response to K15 or to TLR ligands, both neutralizing Abs against IL-6 and IL-10 impaired IgA induction by their respective cytokines (Fig. 1c). As IL-5 was not involved in the induction of IgA secretion, the induction of IgA by LAB-stimulation likely occurs via a T cell-independent pathway. These results indicate that, in human PBMCs, the effects of LAB on activating IgA production are induced by IL-6 and IL-10, most likely secreted by DCs in response to LAB.

Figure 1.

IgA secretion from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) in response to lactic acid bacteria (LAB) (a) PBMCs from 7 donors were cultured in medium alone (−) or stimulated with various strains of heat-killed LAB in triplicates for 5 days. The tested strains of LAB are described in Table S1. The resulting IgA concentrations were measured by ELISA. Data are represented as mean ± SD of 7 donors. *p < 0.05 (vs medium alone, Student’s t-test). (b) PBMCs were cultured in medium alone (−) or simulated with heat-killed K15. The resulting mRNA expressions of Blimp-1, April, and Baff were measured by qPCR. Data are represented as mean ± SD of duplicates and are representative of two independent experiments from different individuals. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 (Student’s t-test). (c) PBMCs were cultured in medium alone (−) or stimulated with heat-killed K15, poly(I:C) (10 μg/mL), or LPS (10 μg/mL) for 5 days in the presence of control Ab (cont Ab), anti-IL-5 mAb (αIL-5 Ab), anti-IL-6 mAb (αIL-6 Ab), or anti-IL-10 mAb (αIL-10 Ab). The resulting IgA concentrations were measured by ELISA. Data are represented as the mean ± SD of triplicates and are representative of two independent experiments from different individuals. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 (Student’s t-test).

IgA production by B cells via the DC response to LAB

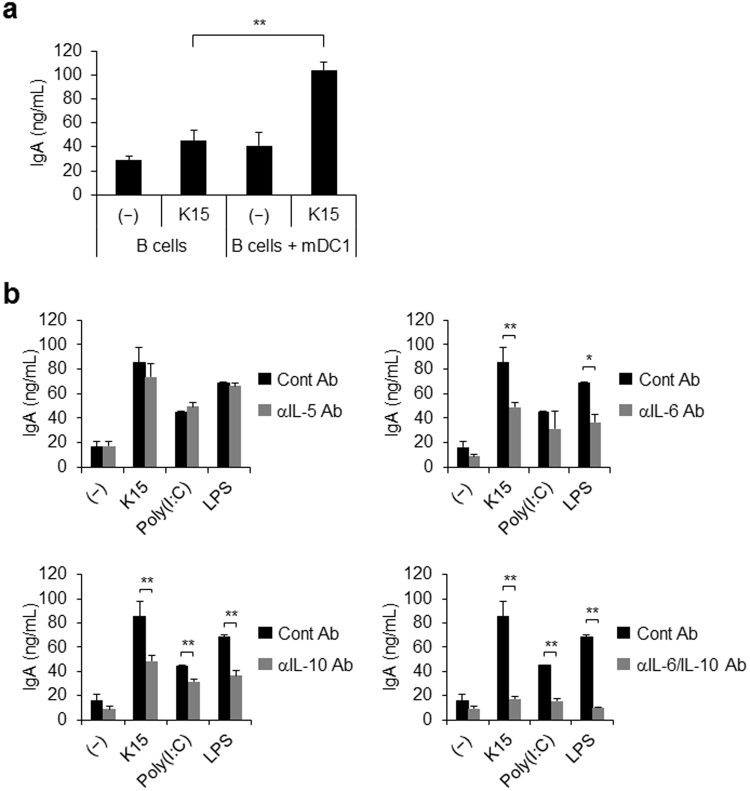

LAB contain many kinds of TLR ligands, such as bacterial cell walls, which are ligands for TLR2 and TLR4, dsRNA, which is a ligand of TLR3, and DNA, which is a ligand of TLR914,33–36. DCs are activated by these TLR ligands, and these cells, once activated, secrete many kinds of cytokines and IFNs. We isolated BDCA1+ DCs (mDC1s) and B cells from PBMCs and co-cultured them in the presence of neutralizing Abs against IL-5, IL-6, and IL-10. Following stimulation by K15, IgA production by B cells was slightly activated in the absence of mDC1s, whereas it was strongly activated in the presence of mDC1s (Fig. 2a). This indicates that DCs contribute to the activation of IgA secretion in response to LAB. When neutralizing Abs against IL-5, IL-6, and IL-10 were added to this co-culture system, the Abs against IL-6 and IL-10 significantly suppressed IgA production in response to LAB, and the combination of both of these Abs completely abolished IgA production (Fig. 2b). This result is in accordance with the observed IgA production by PBMCs described above (Fig. 1b). Together, these results strongly suggest that the IL-6 and IL-10 secreted by DCs in response to LAB activate IgA production by B cells. Previous reports identified IL-6 as a critical factor for IgA induction by LAB in mice17. However, our present research clearly demonstrates that IL-10 also makes a major contribution to this process in humans.

Figure 2.

IgA secretion from B cells in the presence of dendritic cells (DCs) and/or LAB (a) B cells and BDCA1+ DCs (mDC1s) were isolated from PBMCs. B cells were co-cultured with heat-killed K15 in the presence or absence of mDC1s for 5 days. The resulting IgA concentrations were measured by ELISA. (b) B cells and mDC1s were cultured with K15, poly(I:C) (10 μg/mL), or LPS (10 μg/mL) for 5 days in the presence of control Ab (cont Ab), anti-IL-5 mAb (αIL-5 Ab), anti-IL-6 mAb (αIL-6 Ab), and/or anti-IL-10 mAb (αIL-10 Ab). The resulting IgA concentrations were measured by ELISA. (a,b) Data are represented as the mean ± SD of triplicates and are representative of two independent experiments from different individuals. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 (Student’s t-test).

IL-6 and IL-10 secretion by DCs in response to bacterial RNA

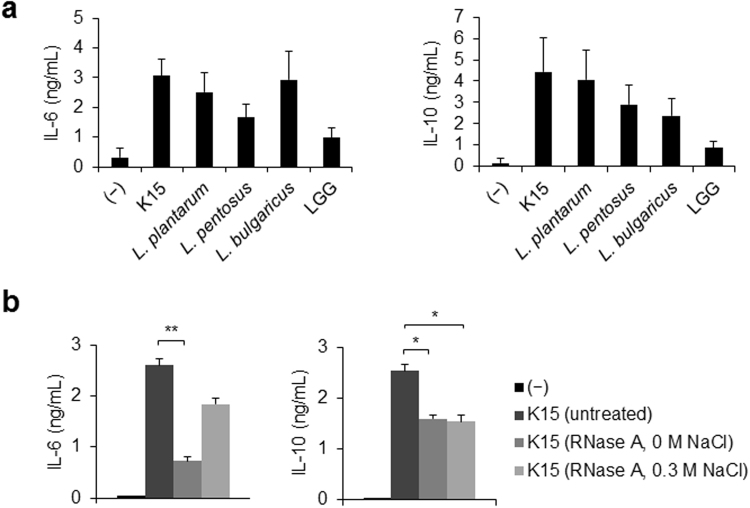

After finding that IL-6 and IL-10 are involved in the activation of IgA production that is induced by LAB, we investigated the levels of these cytokines secreted by mDC1s in response to several strains of LAB. K15 activated IL-6 and IL-10 production by DCs, and L. bulgaricus ATCC11842T strongly induced IL-6 production (Fig. 3a). We previously reported that LAB contain a larger amount of dsRNA than pathogenic bacteria14. To test if RNA in LAB is responsible for the activation of IL-6 and IL-10 production by mDC1s, and thus in inducing IgA secretion, heat-killed K15 were treated with RNase A under 0 M NaCl to degrade both ssRNA and dsRNA or under 0.3 M NaCl to degrade only ssRNA37. IL-6 production by mDC1s in response to K15 was strongly impaired by the degradation of both ssRNA and dsRNA (Fig. 3b) but not significantly by the degradation of ssRNA alone, indicating that bacterial dsRNA is the major component of LAB that induces IL-6 production. In contrast, IL-10 production was partially impaired by degradation under both conditions (Fig. 3b), indicating that ssRNA, but not dsRNA, contributes to IL-10 induction.

Figure 3.

IL-6 and IL-10 production by mDC1s in response to LAB (a) mDC1s were isolated from PBMCs of 7 donors. mDC1s were stimulated with heat-killed LAB in duplicates for 24 h. The tested strains LAB and their abbreviations are described in Table S1. The resulting IL-6 and IL-10 concentrations were measured by ELISA. Data are represented as mean ± SD of 7 donors. (b) Heat-killed K15 cells were treated with RNase A under 0 M NaCl for digestion of ssRNA and dsRNA or under 0.3 M NaCl for digestion of ssRNA only. mDC1s were cultured with heat-killed K15 or RNase A-treated, heat-killed K15 for 24 h. The resulting IL-6 and IL-10 concentrations were measured by ELISA. Data are represented as the mean ± SD of duplicates and are representative of two independent experiments from different individuals. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 (Student’s t-test).

Activation of salivary sIgA production by K15 ingestion in a clinical trial

The effect of LAB on salivary IgA production was evaluated in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial using heat-killed K15. The secretion rate of salivary sIgA was significantly increased by ingestion of K15 for 8 and 12 weeks compared with baseline (p = 0.021 for 8 weeks, p = 0.002 for 12 weeks) and samples from participants who had ingested a placebo for 12 weeks (p = 0.036) (Table 1). The salivary sIgA concentration was significantly enhanced only in the K15 group (p = 0.003) (Table 1). These results indicate that K15 ingestion enhances salivary sIgA production, likely via IL-6 and IL-10 secreted by DCs, resulting in the activation of anti-viral or anti-bacterial immune responses. Any adverse reactions were not observed.

Table 1.

Salivary sIgA secretion rate, saliva flow rate, and salivary sIgA concentrations in placebo group (n = 25) and K15 group (n = 27).

| Group | Before | 4 weeks | 8 weeks | 12 weeks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salivary sIgA secretion rate (μg/min) | ||||

| Placebo | 160.6 ± 8.3 | 189.7 ± 18.3 | 205.3 ± 24.2 | 211.7 ± 21.9# |

| K15 | 148.6 ± 8.8 | 162.1 ± 18.9 | 195.8 ± 21.6# | 208.9 ± 20.2## |

| Saliva flow rate (g/min) | ||||

| Placebo | 0.619 ± 0.042 | 0.660 ± 0.034# | 0.655 ± 0.035 | 0.653 ± 0.027 |

| K15 | 0.623 ± 0.046 | 0.599 ± 0.044 | 0.646 ± 0.040 | 0.616 ± 0.041 |

| Salivary sIgA concentration (mg/dL) | ||||

| Placebo | 31.5 ± 4.3 | 30.9 ± 3.6 | 32.5 ± 4.3 | 34.1 ± 4.2 |

| K15 | 27.2 ± 2.7 | 28.4 ± 2.9 | 31.6 ± 3.6 | 37.4 ± 4.1## |

mean ± SE, #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 compared with baseline according to a Student’s t-test.

Discussion

It has been reported that probiotic strains of LAB activate IgA production by B cells; this molecular mechanism was revealed in mice17. In the present study, we elucidated the mechanism for the effect of a functional LAB strain, Pediococcus acidilactici K15, on IgA production, focusing on the role of bacterial RNA in the interaction between DCs and B cells from human peripheral blood. In fact, K15, which activated IgA secretion from PBMCs in vitro, upregulated salivary sIgA concentration in healthy adults.

In mice, IL-6 secretion by PP DCs in response to some strains of Lactobacillus sp. promoted IgA+ B cells to differentiate into IgA-producing plasma cells17. The present study found that in human PBMCs, IL-10 is another critical factor for activating IgA production from B cells. Moreover, we demonstrated via the use of a co-culture system composed of PBMC-derived mDC1s and B cells that the activation of IgA production by K15 is dependent on the function of DCs and their recognition of bacterial RNA.

A number of studies using animal models have revealed the beneficial effects of orally administered LAB, including Pedioccocus acidilactici5,6,14,17,38, suggesting that orally administered LAB are recognized in the intestine by antigen-presenting cells including DCs and macrophages. In our clinical trial, we confirmed that the salivary sIgA concentration was enhanced by K15 ingestion. Although we did not directly analyse the DCs in the guts of our human volunteers, our in vitro data and previous work on the immune events in the intestine suggest that the ingested K15 were probably recognized by DCs in PPs or the lamina propria, which then upregulated the IgA concentration in saliva. Arase et al. reported that a strong correlation is observed in humans between the levels of challenge-bacteria-specific IgA Ab in sublingual/submandibular secretions and those in gut lavages39.

For augmentation of sIgA production at mucosal sites, an IgA class switch recombination to IgA+ B cells induced by APRIL and BAFF is necessary28–30. In humans, it has been reported that APRIL, but not BAFF, is produced by monocyte-derived DCs following stimulation with CpG DNA or poly(I:C), although other TLR ligands were not able to induce either molecule40. In mice, all-trans-retinoic acid (RA) and IL-4 were shown to promote IgA class switching in cooperation with IL-541, but we found that this mechanism was not involved in the IgA induction in our culture system. Here, we observed that the mRNA expression levels for APRIL, BAFF, and Blimp-1 were increased in PBMCs in the presence of LAB, which suggests that LAB may be sufficient to activate B cells for class switching and may also directly activate Tfh in the intestine. We also demonstrated in the present study that LAB RNA is the active component inducing the cytokine production that is critical for the enhancement of IgA production by B cells; dsRNA is a major causative molecule for IL-6 production whereas single-stranded RNA is critical factor for IL-10 production. Further investigations are needed to determine if these bacterial ligands to TLRs also contribute to IgA class switching and the promotion of IgA production via DC and Tfh functions.

Here, we used mDC1s isolated from PBMCs in a co-culture system with B cells. In addition to mDC1s, BDCA3+ DCs (mDC2s) and pDCs are also part of the composition of PBMCs, and, among these DC subsets, mDC1s and pDCs are the more abundant cell populations42,43. mDC2s express a high level of TLR3, which recognizes the dsRNA in viruses and bacteria and secretes IFN-λ, a type III IFN44. pDCs express TLR7/8 and TLR9 and robustly secrete IFN-α during viral infections16,45–47. mDC1s expressing many kinds of TLRs have been found to secrete IFN-β and many kinds of cytokines, including IL-12 and IL-27, in response to poly(I:C), R848, and LPS43,48–50. Additionally, mDC1s secrete higher levels of IL-6 in response to Staphylococcus aureus, whose active ligand is TLR448. Furthermore, IL-10 and IL-6 secretion levels in response to poly(I:C) were also reported to be higher in mDC1s than in mDC2s51. Thus, mDC1s seem to make a greater contribution to immunity than other DC subsets in the case of IgA induction via IL-6 and IL-10 production upon stimulation with bacteria.

In addition to IgA induction, probiotic bacteria aid a variety of aspects relating to anti-infection immune functions. We previously reported that LAB contain large amounts of dsRNA, which induces IFN-β production via the TLR3 signalling pathway14. Type I IFNs, IFN-α and IFN-β, are well known to trigger a robust immune response against viral and bacterial infections13,52. LAB also activate IL-12 secretion from DCs or macrophages, which promotes Th1 cell differentiation, natural killer cell activation, and cytotoxic CD8+ T cell activation in concert with IL-27 and IL-18 production49,53. These subsets of cells protect against viral infection as well. Together, previous work and our current study suggest that functional strains of LAB, which has high safety for human and induce the production of IFN-β, IL-12, IL-6, and IL-10 by mDCs, protect the human body against viral and bacterial infection and maintain immune homeostasis by augmenting many of the pathways involved in protective immune responses.

Methods

Preparation of LAB for in vitro experiments

LAB were purchased from the Japan Collection of Microorganisms (JCM) or isolated from fermented foods (Table S1). Pediococcus acidilactici K15, Lactobacillus plantarum ATCC14197T, and Lactobacillus pentosus ATCC8041T were cultured at 30 °C for 24 h in MRS broth (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD, USA). Lactobacillus delbrueckii sup. bulgaricus ATCC11842T and Lactobacillus rahmnosus ATCC53103T (LGG) were cultured at 37 °C for 24 h in MRS broth. They were then heat-killed, washed twice with saline, and suspended in saline. For nuclease treatment of the heat-killed bacteria, treatment with RNase A from bovine pancreas (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was performed under low salt conditions (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0) or high salt conditions (10 mM Tris-HCl, 0.3 M NaCl, pH 8.0) at 37 °C for 2 h. RNase A-treated bacteria were washed twice with each buffer and used for subsequent experiments.

Preparation of PBMCs, B cells, and mDC1s

These in vitro experiments were carried out in accordance with the Ethics Committee of Kikkoman Corporation (Chiba, Japan, No. KC-RD9), and blood samples were acquired from healthy volunteers under informed written consent in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2013). PBMCs were isolated by using Ficoll-Paque PLUS (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA). B cells were isolated from PBMCs by using CD19 microbead labelling and the MACS system (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch-Gladbach, Germany). Cell purity was typically over >95% as assessed by staining with FITC-conjugated anti-CD19 Ab (Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA). mDC1s were isolated by using a CD1c (BDCA1)+ Dendritic Cell Isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cell purity was >98% as assessed by staining with FITC-conjugated anti-CD11c, BV421-conjugated anti-CD1c, and APC-conjugated HLA-DR.

Cell culture

Cell culture assays were performed in RPMI 1640 (Gibco, Paisley, UK) including 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (HyClone Laboratories, Logan, Utah), MEM Vitamin Solution (100×, Gibco), MEM Non-Essential Amino Acids (100×, Gibco), Penicillin Streptomycin (100×, Gibco), Sodium Pyruvate (100 mM, Gibco) and 2-Mercaptoethanol (1000×, Gibco) in a humidified incubator (5% CO2) at 37 °C. PBMCs were cultured in 96-well round-bottomed plates at 2 × 105 cells/well/250 μl in the presence or absence of 1 × 107 bacteria for 5 days. B cells were cultured at 4 × 104 cells/well/250 μl with 2 × 104 mDC1s in the presence or absence of 1 × 107 bacteria for 5 days. The level of IgA in culture supernatants was measured by ELISA using anti-human IgA mAb and biotin-conjugated anti-human IgA mAb (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA). mDC1s were cultured at 5 × 104 cells/well/200 μl with 1 × 107 bacteria, and the levels of IL-10 and IL-6 in culture supernatants were determined by corresponding ELISA kits (eBiosciences, San Diego, CA, USA).

Reagents

To neutralize IL-5, IL-6, and IL-10, monoclonal antibody (mAb) against each cytokine (Biolegend) was added at 10 μg/ml. Rat IgG1 Ab (Biolegend) was used as an isotype control Ab. Poly(I:C) and LPS (both purchased from Invivogen, San Diego, CA, USA) were added at 10 μg/ml as representative TLR3 and TLR4 ligands, respectively.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from the cells with a NucleoSpin RNA Kit (Takara, Kyoto, Japan) following the manufacturer’s instructions. An equal amount of total RNA (300 ng) corresponding to each priming dose was reverse-transcribed using PrimeScript RT Reagent (Takara). The cDNA obtained after reverse transcription was amplified using specific primers for Blimp-1, APRIL, BAFF, and β-actin purchased from Takara and SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (Takara) following the protocols provided. The analysis of each gene expression was performed by normalizing to β-actin.

Preparation of clinical test foods

Test foods were prepared by Kikkoman Corporation. K15 was cultured in medium including soy peptone, yeast extract, and glucose. The cultured K15 were then heat-killed, washed with saline, concentrated, and spray-dried with dextrin. The test foods for the K15 and placebo groups were prepared using this K15 powder and a dextrin powder (Table S2). The subjects in the K15 group ingested 1 g of dextrin including 9.1 mg of heat-killed K15 (5 × 1010 bacteria) every day for 12 weeks, while the subjects in the placebo group ingested 1 g of dextrin alone. Bacterial number in K15 samples was counted by using Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope (400×, Japna) and Micro Slide Glass (Matsunami Glass Ind., Ltd, Japan). The participants and the researchers were not able to discriminate between placebo and K15 samples.

Clinical study design

This study took place at Ueno Clinic, Aisei Hospital (Tokyo, Japan) between June 2016 and March 2017. A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial was performed for 12 weeks. The trial was conducted by TTC Co. Ltd. funded by Kikkoman Corporation and approved by the Ethics Committee of Ueno Clinic, Aisei Hospital (Protocol No. 20160609–2) in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2013). The trial was registered in the UMIN Clinical Trials Registry as UMIN000022880 (date of registration 01/04/2017). All participants provided written informed consent approved by the ethics committee. Data for body height, body weight, BMI, blood pressure, pulse, and biochemistry tests (BML Co. Ltd., Saitama, Japan) were obtained for all subjects before treatment and every 4 weeks after treatment. All subjects were followed up until the physician confirmed they had no important harms, and any important harms related to test foods were not observed. All subjects answered Profile of Mood States 2 Adult Short Form (POMS 2-A) and questionnaires about their weekly life events to confirm their fatigue and psychological stress. The salivary sIgA secretion rate was the primary outcome, and the salivary sIgA concentration and T scores in POMS 2-A were the secondary outcomes. We confirmed that Fatigue–Inertia (FI) T scores and Vigor–Activity (VA) T scores were significantly improved in both groups and were not different between two groups (Table S3).

Subjects for a clinical trial

The subjects were recruited from volunteers enrolled in Medical Art Laboratory Co. Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan), and 60 subjects were selected from 382 volunteers by the selection and exclusion criteria. The selection criteria were as follows: subjects who (a) were 20–64 years old and healthy; (b) had a lower than average salivary sIgA secretion rate; and (c) had a FI T score of more than 50 with a VA T score of less than 50 as assessed by POMS 2-A. The exclusion criteria were follows: subjects who (a) consumed food containing lactic acid bacteria, such as yogurt and other fermented foods; (b) had an allergic disease; (c) had mouth or teeth issues or were under treatment of them; (d) routinely engaged in vigorous exercises; (e) were pregnant or lactating; or (f) were inappropriate cases for the trial as defined by physicians. The researcher independent of this study (TTC Co. Ltd.) performed simple randomized allocation of the subjects by using a computer-generated list of random numbers. The allocation sequence was concealed from the researcher enrolling and assessing participants in the sealed envelope. This allocation sequence was opened by the independent researcher described above only after the enrolled participants completed all assessments.

Determination of salivary sIgA secretion rate and concentration

Saliva samples were collected for measurement of sIgA concentration and saliva flow rate before and every 4 weeks after the start of K15 or placebo ingestion. Salivary sIgA concentration was determined by ELISAs performed by Daiichi Kishimoto Clinical Laboratories, Inc. (Hokkaido, Japan). The salivary sIgA secretion rate was calculated from the saliva flow rate and salivary sIgA concentration.

Statistical analysis

Error bars on figures indicate the standard deviation (SD) of duplicate or triplicate samples for cell culture assay experiments. Statistical analysis was performed by PASW Statistics Version 18.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). The statistical significance was determined with a two-tailed Student’s t-test for unpaired data, with p values of <0.05 considered significant (indicated on figures and tables as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01). In the clinical trial, the consumption of test samples was monitored via diaries kept by the subjects, and these reports indicated that all subjects consumed more than 90% of total test samples. Two subjects (placebo group: n = 1, K15 group: n = 1) were excluded from the analysis due to meeting the exclusion criteria during the test period (Fig. S1). The subjects whose saliva flow rate strongly changed during the test period (CV > 1.5 SD) were also excluded from the analysis (placebo group: n = 4, K15 group: n = 2) (Fig. S1). Error bars on the figures presenting these data indicate standard error (SE). The statistical significance between two groups was determined with a two-tailed Student’s t-test for unpaired data, with p values of <0.05 considered significant. The comparison between values from before and after the ingestion of test samples was performed by a paired t-test.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs A. Matsuyama and T. Horiba for their helpful advice, and Mrs T. Ishibashi, Mr. M. Adachi, and Ms. T. Taniguchi for their technical assistance.

Author Contributions

T. Kawashima and N.I. equally contributed to this work. T. Kawashima., N.I., T. Kouchi, Y. Kubota, N.S., and N.M.T. designed, performed, and analysed in vitro experiments. Y. Kowatari designed the clinical study protocol and provided clinical operations and analyses. T. Kawashima and N.I. wrote the paper.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-23404-4.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gorbach SL. Lactic acid bacteria and human health. Ann Med. 1990;22:37–41. doi: 10.3109/07853899009147239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drouault S, Corthier G. Health effects of lactic acid bacteria ingested in fermented milk. Vet Res. 2001;32:101–117. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2001115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parvez S, Malik KA, Ah Kang S, Kim HY. Probiotics and their fermented food products are beneficial for health. J Appl Microbiol. 2006;100:1171–1185. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.02963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nova E, et al. Immunomodulatory effects of probiotics in different stages of life. Br J Nutr. 2007;98:S90–S95. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507832983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kawashima T, et al. Lactobacillus plantarum strain YU from fermented foods activates Th1 and protective immune responses. Int Immunopharmacol. 2011;11:2017–2024. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masuda S, et al. Immunomodulatory effect of halophilic lactic acid bacterium Tetragenococcus halophilus Th221 from soy sauce moromi grown in high-salt medium. Int J Food Microbiol. 2008;121:245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nagao F, Nakayama M, Muto T, Okumura K. Effects of a fermented milk drink containing Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota on the immune system in healthy human subjects. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2000;64:2706–2708. doi: 10.1271/bbb.64.2706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishida Y, et al. Clinical effects of Lactobacillus acidophilus strain L-92 on perennial allergic rhinitis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Dairy Sci. 2005;88:527–533. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(05)72714-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nishimura I, et al. Clinical efficacy of halophilic lactic acid bacterium Tetragenococcus halophilus Th221 from soy sauce moromi for perennial allergic rhinitis. Allergol Int. 2009;58:179–185. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.O-08-548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shu Q, Gill HS. Immune protection mediated by the probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 (DR20) against Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection in mice. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2002;34:59–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2002.tb00603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corr SC, Gahan CG, Hill C. Impact of selected Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species on Listeria monocytogenes infection and the mucosal immune response. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2007;50:380–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2007.00264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang L, Yang L, Fikrig E, Wang P. An essential role of PI3K in the control of West Nile virus infection. Sci Rep. 2017;7:3724. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03912-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Samuel CE. Antiviral actions of interferons. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14:778–809. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.4.778-809.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawashima T, et al. Double-stranded RNA of intestinal commensal but not pathogenic bacteria triggers production of protective interferon-β. Immunity. 2013;38:1187–1197. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawase M, He F, Kubota A, Harata G, Hiramatsu M. Oral administration of lactobacilli from human intestinal tract protects mice against influenza virus infection. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2010;51:6–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2010.02849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maeda N, et al. Oral administration of heat-killed Lactobacillus plantarum L-137 enhances protection against influenza virus infection by stimulation of type I interferon production in mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 2009;9:1122–1125. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kotani Y, et al. Role of Lactobacillus pentosus strain b240 and the Toll-like receptor 2 axis in Peyer’s patch dendritic cell-mediated immunoglobulin A enhancement. PLoS One. 2014;9:e91857. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mestecky J, Russell MW. Specific antibody activity, glycan heterogeneity and polyreactivity contribute to the protective activity of S-IgA at mucosal surfaces. Immunol Lett. 2009;124:57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Masahata K, et al. Generation of colonic IgA-secreting cells in the caecal patch. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3704. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kubinak JL, et al. MyD88 signaling in T cells directs IgA-mediated control of the microbiota to promote health. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17:153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawamoto S, et al. Foxp3+ T cells regulate immunoglobulin a selection and facilitate diversification of bacterial species responsible for immune homeostasis. Immunity. 2014;41:152–165. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Obata T, et al. Indigenous opportunistic bacteria inhabit mammalian gut-associated lymphoid tissues and share a mucosal antibody-mediated symbiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:7419–7424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001061107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fagarasan S, Honjo T. Regulation of IgA synthesis at mucosal surfaces. Curr Opin Immunol. 2004;16:277–283. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsuji M, Suzuki K, Kinoshita K, Fagarasan S. Dynamic interactions between bacteria and immune cells leading to intestinal IgA synthesis. Semin Immunol. 2008;20:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lycke NY, Bemark M. The regulation of gut mucosal IgA B-cell responses: recent developments. Mucosal Immunol. 2017;10:1361–1374. doi: 10.1038/mi.2017.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kawashima T, et al. Double-stranded RNA derived from lactic acid bacteria augments Th1 immunity via interferon-β from human dendritic cells. Front Immunol. 2018;9:27. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ochiai K, Muto A, Tanaka H, Takahashi S, Igarashi K. Regulation of the plasma cell transcription factor Blimp-1 gene by Bach2 and Bcl6. Int Immunol. 2008;20:453–460. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxn005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tezuka H, et al. Regulation of IgA production by naturally occurring TNF/iNOS-producing dendritic cells. Nature. 2007;448:929–933. doi: 10.1038/nature06033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Castigli E, et al. TACI and BAFFR mediate isotype switching in B cells. J Exp Med. 2005;201:35–39. doi: 10.1084/jem.20032000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moore PA, et al. BLyS: member of the tumor necrosis factor family and B lymphocyte stimulator. Science. 1999;285:260–263. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5425.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mora JR, et al. Generation of gut-homing IgA-secreting B cells by intestinal dendritic cells. Science. 2006;314:1157–1160. doi: 10.1126/science.1132742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kanda N, Tamaki K. Ganglioside GT1b suppresses immunoglobulin production by human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Immunology. 1999;96:628–633. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00734.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hisbergues M, et al. In vivo and in vitro immunomodulation of Der p 1 allergen-specific response by Lactobacillus plantarum bacteria. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007;37:1286–1295. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rigaux P, et al. Immunomodulatory properties of Lactobacillus plantarum and its use as a recombinant vaccine against mite allergy. Allergy. 2009;64:406–414. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grangette C, et al. Enhanced antiinflammatory capacity of a Lactobacillus plantarum mutant synthesizing modified teichoic acids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:10321–10326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504084102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Asong J, Wolfert MA, Maiti K, Miller D, Boons GJ. Binding and cellular activation studies reveal that Toll-like receptor 2 can differentially recognize peptidoglycan from gram-positive and -negative bacteria. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:8643–8653. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806633200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ma YJ, Dissen GA, Rage F, Ojeda SR. RNase Protection Assay. Methods. 1996;10:273–278. doi: 10.1006/meth.1996.0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takata K, et al. The lactic acid bacterium Pediococcus acidilactici suppresses autoimmune encephalomyelitis by inducing IL-10-producing regulatory T cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27644. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aase A, et al. Salivary IgA from the sublingual compartment as a novel noninvasive proxy for intestinal immune induction. Mucosal Immunol. 2016;9:884–893. doi: 10.1038/mi.2015.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hardenberg G, et al. Specific TLR ligands regulate APRIL secretion by dendritic cells in a PKR-dependent manner. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:2900–2911. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tokuyama H, Tokuyama Y. The regulatory effects of all-trans-retinoic acid on isotype switching: retinoic acid induces IgA switch rearrangement in cooperation with IL-5 and inhibits IgG1 switching. Cell Immunol. 1999;192:41–47. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1998.1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kitcharoensakkul M, et al. Temporal biological variability in dendritic cells and regulatory T cells in peripheral blood of healthy adults. J Immunol Methods. 2016;431:63–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2016.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nizzoli G, et al. Human CD1c+ dendritic cells secrete high levels of IL-12 and potently prime cytotoxic T-cell responses. Blood. 2013;122:932–942. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-495424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yoshio S, et al. Human blood dendritic cell antigen 3 (BDCA3)+ dendritic cells are a potent producer of interferon-λ in response to hepatitis C virus. Hepatology. 2013;57:1705–1715. doi: 10.1002/hep.26182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bhardwaj N. Interactions of viruses with dendritic cells: a double-edged sword. J Exp Med. 1997;186:795–799. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.6.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ito T, Wang YH, Liu YJ. Plasmacytoid dendritic cell precursors/type I interferon-producing cells sense viral infection by Toll-like receptor (TLR) 7 and TLR9. Springer Semin Immunol. 2005;26:221–229. doi: 10.1007/s00281-004-0180-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Siegal FP, et al. The nature of the principal type 1 interferon-producing cells in human blood. Science. 1999;284:1835–1837. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5421.1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jin JO, Zhang W, Du JY, Yu Q. BDCA1-positive dendritic cells (DCs) represent a unique human myeloid DC subset that induces innate and adaptive immune responses to Staphylococcus aureus Infection. Infect Immun. 2014;82:4466–4476. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01851-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.de Groot R, et al. Viral dsRNA-activated human dendritic cells produce IL-27, which selectively promotes cytotoxicity in naive CD8+ T cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2012;92:605–610. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0112045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kreutz M, et al. Type I IFN-mediated synergistic activation of mouse and human DC subsets by TLR agonists. Eur J Immunol. 2015;45:2798–2809. doi: 10.1002/eji.201545583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schulte BM, et al. Enterovirus-infected β-cells induce distinct response patterns in BDCA1+ and BDCA3+ human dendritic cells. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0121670. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cella M, et al. Plasmacytoid monocytes migrate to inflamed lymph nodes and produce large amounts of type I interferon. Nat Med. 1999;5:919–923. doi: 10.1038/11360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zwirner NW, Ziblat A. Regulation of NK cell activation and effector functions by the IL-12 family of cytokines: the case of IL-27. Front Immunol. 2017;8:25. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.