Abstract

Transition-metal-catalyzed direct site-selective functionalization of arene C–H bonds has emerged as an innovative approach for building the core structure of pharmaceutical agents and other versatile complex compounds. However, para-selective C–H functionalization has seldom been explored, only a few examples, such as steric-hindered arenes, electron-rich arenes, and substrates with a directing group, have been reported to date. Here we describe the development of a ruthenium-enabled para-selective C–H difluoromethylation of anilides, indolines, and tetrahydroquinolines. This reaction tolerates various substituted arenes, affording para-difluoromethylation products in moderate to good yields. Results of a preliminary study of the mechanism indicate that chelation-assisted cycloruthenation might play a role in the selective activation of para-CAr–H bonds. Furthermore, this method provides a direct approach for the synthesis of fluorinated drug derivatives, which has important application for drug discovery and development.

Selective para-functionalization of substituted arenes is a formidable challenge in homogeneous catalysis. Here, the authors achieved the para-selective C-H difluoromethylation of anilides, indolines and tetrahydroquinolines with a ruthenium catalyst in good yields and apply it to the synthesis of bioactive compounds.

Introduction

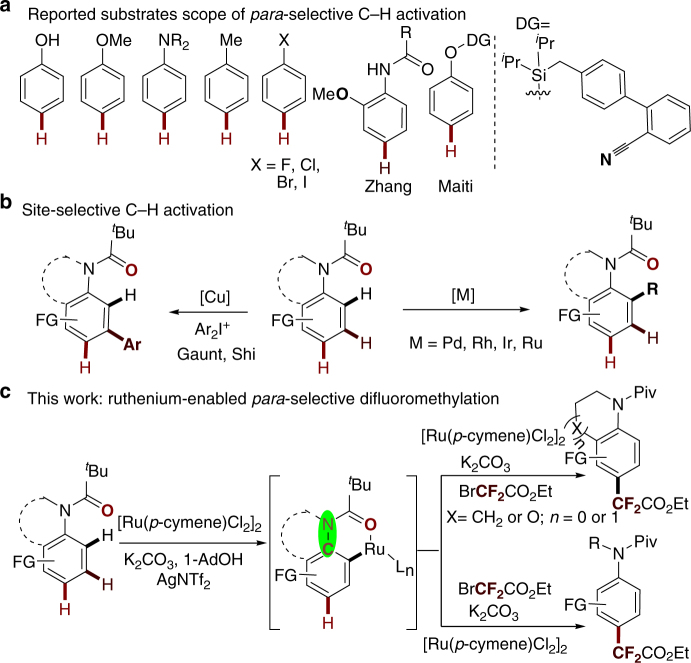

Over the past decade, transition-metal-catalyzed direct site-selective functionalization of arene C–H bonds has emerged as an innovative approach for building the core structure of pharmaceutical agents and other versatile complex compounds. In this context, various ortho-selective C–H functionalization reactions have been well-developed through the σ-chelation-directed cyclometalation strategy1–9. However, remote C–H functionalization still remains a great challenge. Compared with recently developed meta-selective C–H functionalization10–26, para-selective C–H functionalization is less explored;27–34 only a few examples, such as steric-hindered arenes35,36, electron-rich arenes37–43, and substrates with a directing group44, have been reported to date. For instance, Zhang and co-workers reported in 2011 a Pd(II)-catalyzed para-selective amination of ortho-methoxy-substituted anilide. Interestingly, substrate blockage of both orthopositions was also tolerated (Fig. 1a). In 2015, Maiti’s group independently developed a D-shaped template for the highly selective olefination of the para-C–H bond using a palladium catalyst (Fig. 1a)45. Very recently, a variety of para-selective functionalizations of less-activated arenes via nickel/aluminum46, gold47, and palladium48 catalyzes have been reported. Despite such major advances, most para-selective C–H functionalizations suffer from serious drawbacks such as limited substrate scope and relatively poor regioselectivity, which significantly restrict their applications (Fig. 1a)27–34. Therefore, a catalyst-controlled strategy for para-selective C–H functionalization of arenes is highly desired.

Fig. 1.

Site-selective C–H activation reactions. a Reported substrate scope of para-selective C–H activation. b Site-selective C–H activation. c Our work on ruthenium-enabled para-selective difluoromethylation

Fluorine-containing compounds are widely applied in pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals, and life sciences49,50. Specifically, the installation of a difluoromethylene (CF2) group into organic compounds is of particular value because it can cause significant changes in the chemical and physical properties of biologically active compounds51,52. As a consequence, there is a continued strong demand for methods that enable the selective synthesis of difluoromethylated molecules53–56.

Despite the development of various approaches to ortho- and meta-selective C–H functionalizations of anilides, indolines, and tetrahydroquinolines, which are significantly important molecular skeletons in medicinal chemistry (Fig. 1b)57–62, the general strategy for highly para-selective C–H functionalization is still elusive. Herein, we report a ruthenium(II)-enabled para-selective difluoromethylation of anilides, indolines, and tetrahydroquinolines. This reaction tolerates a wide variety of functional groups, affording the corresponding para-difluoromethylated products in moderate to good yields. Preliminary experimental results suggest that chelation-assisted cycloruthenation might play a role in the selective activation of para-CAr–H bonds.

Results

Optimization of reaction conditions

At the outset, N-pivaloylaniline 1a was reacted with bromodifluoroacetate 2 in the presence of [Ru(p-cymene)Cl2]2 (5 mol%), 1-Ad-OH (0.2 equiv.), and K2CO3 (4 equiv.) in DCE at 120 °C to investigate whether the para-selective C–H difluoromethylation could be performed. We were pleased to observe that we generated the para-difluoromethylated product 3a in 45% yield (Table 1, entry 1). Encouraged by this result, we decided to further optimize the conditions to improve the efficiency. We investigated several additives, e.g., MesCO2H, Piv-Val-OH, Piv-OH, and KOAc, but none of them gave a noticeable enhancement (Table 1, entries 2–5). Subsequently, various silver salts that are known as facilitating to active the rhodium or iridium catalyst precursors were screened. To our great delight, dramatically improved yields of 3a were obtained (53–65%; Table 1, entries 6–8). We could further enhance the reaction efficiency by an increase in AgNTf2 (20 mol%) loading, which provided product 3a in 87% yield (Table 1, entry 9). In addition, the use of RuCl3, Pd(PPh3)4, or Cu2O, Ni(acac)2 or the obviation of [Ru(p-cymene)Cl2]2 failed to lead to para-selective transformation under otherwise identical conditions (Table 1, entries 10–14).

Table 1.

Optimization of para-C–H difluoromethylationa

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Catalyst | Silver salt | Additive | Yield (%)b |

| (5 mol%) | (10 mol%) | (20 mol%) | ||

| 1 | [Ru(p-cymene)Cl2]2 | No | 1-Ad-OH | 45 |

| 2 | [Ru(p-cymene)Cl2]2 | No | KOAc | 35 |

| 3 | [Ru(p-cymene)Cl2]2 | No | Piv-OH | 39 |

| 4 | [Ru(p-cymene)Cl2]2 | No | MesCO2H | 40 |

| 5 | [Ru(p-cymene)Cl2]2 | No | Piv-Val-OH | 32 |

| 6 | [Ru(p-cymene)Cl2]2 | AgBF4 | 1-Ad-OH | 51 |

| 7 | [Ru(p-cymene)Cl2]2 | AgSbF6 | 1-Ad-OH | 48 |

| 8 | [Ru(p-cymene)Cl2]2 | AgNTf2 | 1-Ad-OH | 65 |

| 9 | [Ru(p-cymene)Cl2]2 | AgNTf2 | 1-Ad-OH | 87c |

| 10 | RuCl3 | AgNTf2 | 1-Ad-OH | 21c |

| 11 | Pd(PPh3)4 | No | 1-Ad-OH | Trace |

| 12 | Cu2O | No | 1-Ad-OH | Trace |

| 13 | Ni(acac)2 | No | 1-Ad-OH | Trace |

| 14 | No | AgNTf2 | 1-Ad-OH | 0 |

a Reaction condition: 1a (0.20 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), 2 (3 equiv.), K2CO3 (4 equiv.), catalyst (5 mol%), additive (20 mol%), and Ag salt (10 mol%) in DCE (0.5 mL) for 48 h at 120 °C under argon in a sealed tube

b GC yield using biphenyl as the internal standard

c Ag salt (20 mol%)

Scope of the anilide derivatives

Having identified the optimal reaction conditions, we next investigated the substrate scope to explore the versatility of this para-selective difluoromethylation protocol (Table 2). First, a series of ortho-substituted N-phenylpivalamides (1a–1i) performed well under the standard conditions; the corresponding para-difluoromethylated products 3a–3i were exclusively obtained in yields of 38–84% along with the recovered starting material. Various functional groups, such as Me, Et, OMe, OPh, t-Bu, Cl, Br, and CO2Me, were fully tolerated. A sterically hindered functional group (tBu, 1e) and electron-withdrawing substituents (Cl, Br, CO2Me, 1g–1i) gave slightly inferior yields. It is noteworthy that o-methoxy-substituted N-phenylpivalamides (1d) were exclusively transformed into p-difluoromethylated products (3d) without formation of the product difluoromethylated at the C5 position. Subsequently, meta-substituted N-phenylpivalamides (1j–1p) were used in the reaction. Overall, the reaction tolerated a wide range of functional groups at the meta position and afforded a decent yield with excellent regioselectivity. The difluoromethylation was found to prefer sterically bulkier positions (C4) over the less sterically hindered positions (C5). Of note are the exceptions, the meta-substituted substrates 1o and 1p, which afforded a mixture of ortho- and para-difluoromethylated products, respectively. It is probable that the electron-donating effect of the methoxy or methylthio groups greatly influenced the reactivity of the C–Ru bonds. Thus, the ruthenium(II) complex could successively trap electrophilic ·CF2CO2Et radicals and undergo reductive elimination, affording ortho-difluoromethylated products (3o(6), 3p(6)). Moreover, the steric effect of the thiomethyl group resulted in a low yield of para-difluorometylated product 3p. Moreover, all of the disubstituted substrates 3q–3s performed well, providing the para-difluoromethylated products in good yields.

Table 2.

Substrate scope of anilidesa

|

a Reaction conditions: [Ru(p-cymene)Cl2]2 (5 mol%), 1 (0.20 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), K2CO3 (4 equiv.), 1-Ad-OH (20 mol%), AgNTf2 (20 mol%), and 2 (3 equiv.) in DCE (0.5 mL) at 120 °C for 48 h under argon; isolated yield after chromatography

These results might indicate that site selectivity is controlled by ruthenium catalysis rather than by functional groups on the aromatic ring. This para-selective difluoromethylation protocol is also amenable to N-alkylanilines protected with pivaloyl amide. All of the substrates reacted well under standard conditions, affording the para-difluoromethylated products in satisfactory yields (3t, 3u). However, ortho- and meta-trifluoromethyl-substituted phenylpivalamides were less reactive, affording difluoromethylated products in only trace amounts (Supplementary Figs. 3-7). When acetyl- and benzoyl-protected aniline were subjected to standard reaction conditions, the difluoromethylated products were obtained in moderate to good yields (3v, 3w). We were puzzled as to how the substrates with a small, strongly electronegative fluorine substituted pivaloyl amide either at the ortho or meta position, providing exclusively ortho-difluoromethylated products (Supplementary Figs. 2, 3sa, 3sb) in good yields. We may attribute this to the electron-withdrawing effect of fluorine, which suppressed the directing ability of ortho cycloruthenation and thereby caused selectivity toward different sites (Supplementary Figs. 3–10).

Scope of the substrates indolines and tetrahydroquinolines

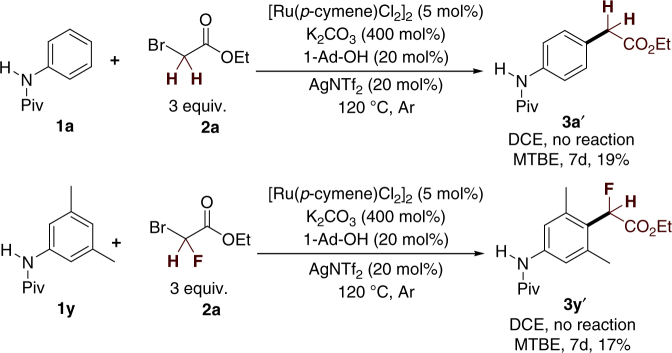

The structural units indoline and tetrahydroquinolines are highly important molecular skeletons in medicinal chemistry; they are widely found in several well-known drugs, such as indapamide, ajmaline, oxamniquine, and argatroban. To explore the generality of this protocol, a number of indoline and tetrahydroquinoline derivatives protected with pivaloyl amide were used as substrates for para-selective difluoromethylation. Gratifyingly, all of these substrates were also compatible with the reaction, delivering the desired para-difluoromethylated products in moderate to good yields (Table 3). A set of functional groups, such Me, Cl, Br, and Ph, were all tolerated by this procedure. It is worth mentioning that the single-crystal structure of product 5c confirms that the ruthenium-enabled difluoromethylation selectively occurs at the para position. In addition, we extended the reaction to monofluoromethylation and non-fluoromethylation, but we obtained only <20% yields of the corresponding products under harsh reaction conditions (Fig. 2). This result may be attributed to the stability of the corresponding free radicals.

Table 3.

Substrate scope of indolines and tetrahydroquinolinesa

|

a Reaction conditions: [Ru(p-cymene)Cl2]2 (5 mol%), 1 (0.20 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), K2CO3 (4 equiv.), 1-Ad-OH (20 mol%), AgNTf2 (20 mol%), and 2 (3 equiv.) in DCE (0.5 mL) at 120 °C for 48 h under argon; isolated yield after chromatography

Fig. 2.

Monofluoromethylation and non-fluoromethylation. a Ruthenium(II)-enabled para-selective non-fluoromethylation. b Ruthenium(II)-enabled para-selective monofluoromethylation

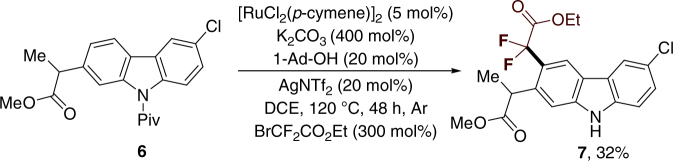

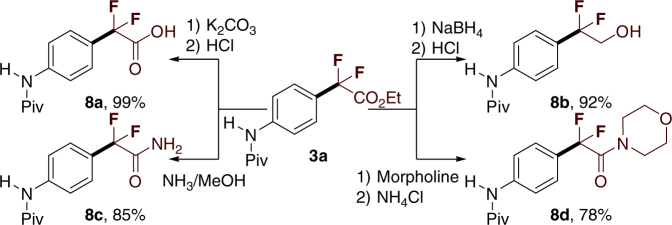

The importance and utility of this protocol can be highlighted by the synthesis of leflunomide (Supplementary Fig. 13), and a carprofen derivative (Fig. 3)63,64, which is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug. Because of the possible decomposition of carprofen protected with pivaloyl amide in the reaction, a relatively low yield of 7 was afforded. Furthermore, the aryldifluoroacetates could be used as precursors to access a variety of difluoromethyl-containing organic molecules such as carboxylic acid (Fig. 4, 8a), primary alcohol (Fig. 4, 8b), and amides (Fig. 4, 8c–8d) in high yields, through different known procedures, as illustrated in Fig. 3. As demonstrated earlier, this method may be a unique and highly efficient protocol for drug discovery and development (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

The application in organic synthesis. Synthesis of a carprofen derivative

Fig. 4.

Transformations of 3a. All the reactions were performed in 0.2 mmol scale. Isolated yields. a K2CO3, MeOH, 60 °C. b NaBH4, EtOH, r.t. c NH3, MeOH, 60 °C. d Morpholine, 60 °C

Mechanistic investigations

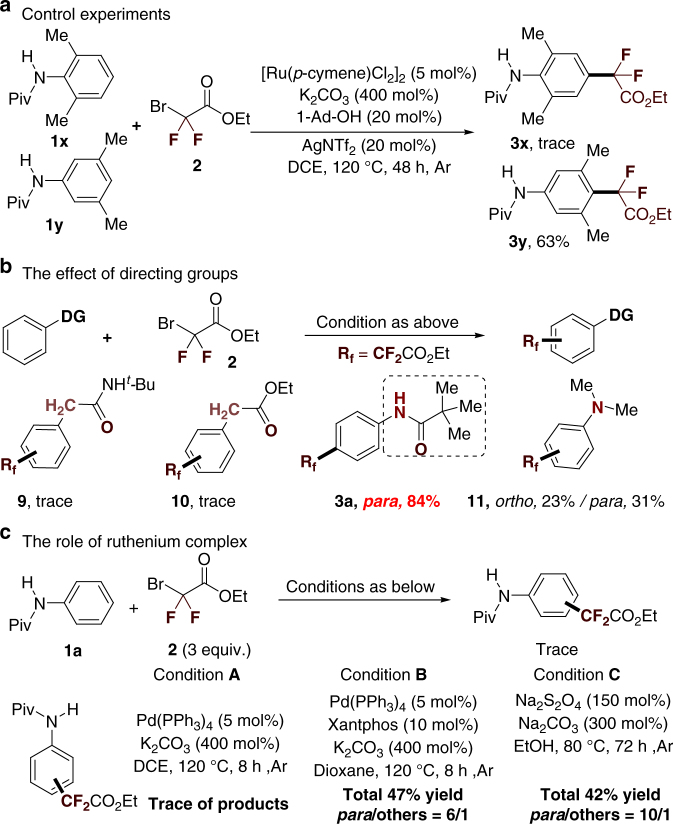

To understand the reaction pathway of this ruthenium-catalyzed site-selective difluoromethylation reaction, additional experiments were extensively performed. First, a control experiment was conducted by using 2,6-dimethyl-substituted aniline as a substrate under the standard conditions (Fig. 5, 1x). In this case, no desired product was formed and the starting material was completely recovered. In sharp contrast, the pivaloyl amide protected 3,5-dimethylaniline (Fig. 5, 1y) gave the para-difluoromethylated products 3y in 63% yield (Fig. 5a). Second, no formation of difluoromethylated products were obtained when ethylphenyl acetate and N-(tert-butyl)-2-phenylacetamide were coupled with 2 under standard conditions (Fig. 5b). Interestingly, the reaction of N,N-dimethylaniline37 as a substrate proceeded well but afforded a mixture of ortho- and para-difluoromethylated products 11 (ortho/para ratio = 1:1.4). These results indicate that ortho-CAr–H metalation plays an important role in accessing para-C–H functionalization reactions17. To further test this hypothesis, several other control experiments were performed (Fig. 5c). The ·CF2CO2Et radical can be generated from 2-bromo-2,2-difluoroacetates, as reported by the groups of Ackermann25, Wang26, and Kondratov65. Thus, we directly treated the substrate 1a with 2 in the presence of the radical initiator. Interestingly, we found that the difluoromehyl radical could be trapped by the substrate 1a. However, only a mixture of ortho-, meta-, and para-difluoromethylated products were obtained. These results suggest that the arylruthenium intermediate (Fig. 6c, IV) might play a role in realizing the para selectivity.

Fig. 5.

Preliminary studies on the mechanism. a Control experiments. b The effect of directing group. c The role of ruthenium complex

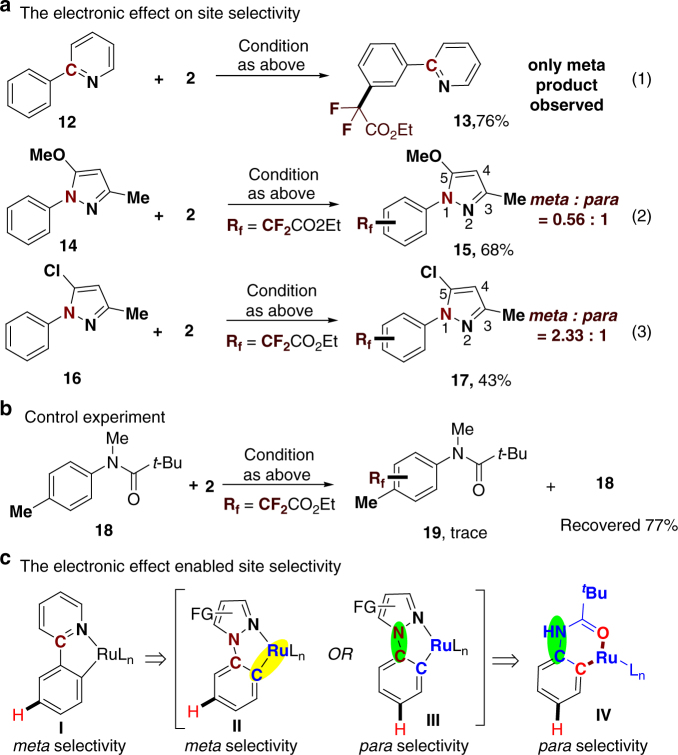

Fig. 6.

Preliminary studies on site selectivity. a The electronic effect on site selectivity. b Control experiment. c The electrionic enabled site selectivity

Third, a set of parallel experiments were performed in order to gain insights into the para selectivity (Fig. 6). We found that only the meta-difluoromethylated product 13 was generated in 76% yield when 2-phenylpyridine (12) and bromodifluoroacetate (2) were treated under standard conditions (Fig. 6a, Eq. (1)). This result is consistented with the reports of Ackermann and Wang on meta-selective difluoromethylation25,26. However, when the pyrazole derivative 14 was utilized in the reaction, a mixture of meta- and para-difluoromethylated products 15 (0.56:1) was obtained in 68% total yield (Fig. 6, Eq. (2)). Interestingly, a decrease in the electron-donating effect on N1 in the pyrazole ring significantly resulted in the regioselectivity shift from the para- to the meta-position (Fig. 6, Eqs. (2) and (3)). These results clearly indicate that the site selectivity could be elegantly tuned by modifying the electronic effect of N1. Finally, pivaloyl amide protected N-methyl-p-toluidine 18, in which the para position was blocked with a –Me group, only afforded <5% yield of difluoromethylated products, along with 77% recovery of the starting material (Fig. 6b), indicating that the ruthenium-catalyzed C–H functionalizations tend to occur at the para-CAr–H position of anilides.

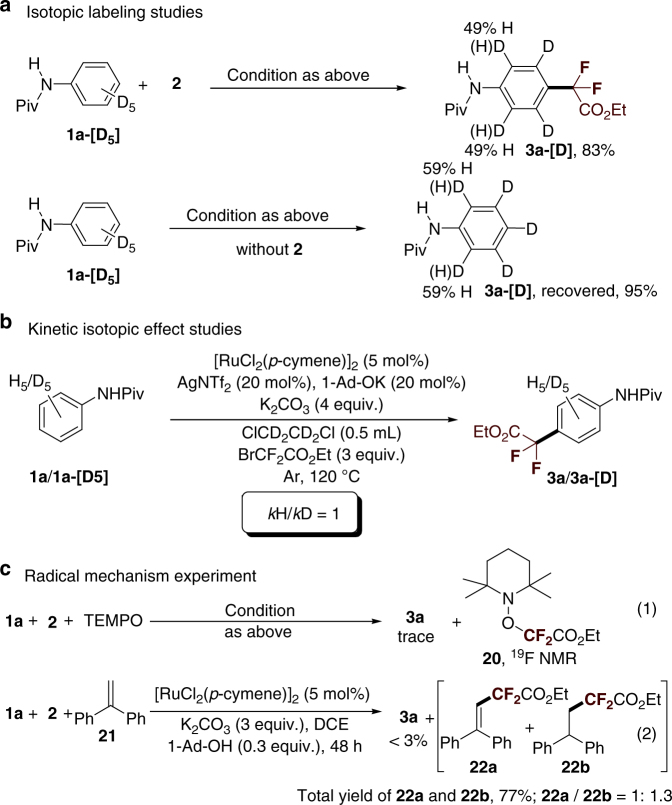

The para difluoromethylation of the isotopically labeled substrate was investigated (Fig. 7). We found that treating 1a-[D5] with 2 under standard reaction conditions afforded the product 3a-[D] in 83% yield, with significant D/H scrambling at the orthoposition. A similar D/H scrambling result was observed when 1a-[D5] was subjected to standard reaction conditions without 2 (Fig. 7a). This result indicates that orthocycloruthenation is reversible. The observed kinetic isotope effect value of 1.0 (Fig. 7b) suggests that CAr–H activation is not a kinetically relevant step. Next, we tried to explore the nature of the para-carbon–carbon bond formation using 2. The reaction conducted in the presence of the radical scavenger TEMPO resulted in complete inhibition of catalytic activity without formation of the desired product 3a. A further 19F NMR study revealed that 20 may have been generated in the reaction, in good agreement with the results of Ackermann et al.25,26. We subsequently introduced the radical scavenger, 1,1-diphenylethylene (21)66,67, which could trap the ·CF2CO2Et radical generated in situ in the reaction (Fig. 7c). As expected, the products 22 formed by coupling 21 with ·CF2CO2Et were predominantly obtained in 77% total yield, and only a trace amount of 3a was observed along with recovery of 1a (Fig. 7c). We further treated 21 with 2 directly in the presence of ruthenium catalysts and K2CO3 in 1,4-dioxane for 12 h in order to obtain a mixture of 22a and 22b in yields >40%. Taken together, all of the foregoing observations suggest the involvement of a free radical pathway for this para-selective difluoromethylation, in which the ruthenium(II) complex can release a ·CF2CO2Et radical through single-electron transfer with 2 as the oxidant.

Fig. 7.

Deuteration and radical experiments. a Isotopic labeling studies. b Kinetic isotopic effect studies. c Radical mechanism experiment

Discussion

In conclusion, we demonstrated the para-selective C–H difluoromethylations of various anilides and indolines using a ruthenium catalyst. In addition, this method provides an efficient approach to directly access fluorinated bioactive compounds derivatives, which is significant for the development of new drugs. Preliminary experimental results show that the catalyst provides para selectivity and that it can release the electrophilic ·CF2CO2Et radical from ethylbromodifluoroacetate. Further applications and mechanistic studies including DFT calculations are now underway.

Methods

Procedure for Ru-catalyzed para-C−H difluoromethylation

A mixture of 1 or 4 (0.2 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), BrCF2CO2Et (80 μL, 121.2 mg, 3 equiv.), [Ru(p-cymene)Cl2]2 (6 mg, 5 mol%), K2CO3 (108.8 mg, 400 mol %), 1-Ad-OH (7.2 mg, 20 mol%), AgNTf2 (14.4 mg, 20 mol%), and DCE (0.5 mL) in a 15 mL glass vial sealed under argon atmosphere was heated at 120 °C for 48 h. The reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature and concentrated in vacuo. The resulting residue was purified by column chromatography (PE/EA = 10: 1) on silica gel to give the product 3 or 5. Full experimental details and characterization of new compounds can be found in the Supplementary Methods.

Data availability

The authors declare that all relevant data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers 1513022. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

Electronic supplementary material

Description of Additional Supplementary Files(PDF 49 kb)

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 21772139, 21572149, 21772020, 21372266). The project of scientific and technologic infrastructure of Suzhou (SZS201708) and the PAPD Project are also gratefully acknowledged.

Author contributions

Y.Z. directed the research. C.Y. and C.C. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. X.C. performed the transformations of 3a. L.Z. and Y.L. performed the mechanism studies. Y.Z., Y.L., and Y.Y. prepared the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-018-03341-6.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yu Lan, Email: lanyu@cqu.edu.cn.

Yingsheng Zhao, Email: yszhao@suda.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Giri R, Shi BF, Engle KM, Maugel N, Yu JQ. Transition metal-catalyzed C–H activation reactions: diastereoselectivity and enantioselectivity. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:3242–3272. doi: 10.1039/b816707a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lyons TW, Sanford MS. Palladium-catalyzed ligand-directed C−H functionalization reactions. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:1147–1169. doi: 10.1021/cr900184e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wencel-Delord J, Glorius F. C–H bond activation enables the rapid construction and late-stage diversification of functional molecules. Nat. Chem. 2012;5:369–375. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ackermann L. Carboxylate-assisted ruthenium-catalyzed alkyne annulations by C–H/Het–H bond functionalizations. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014;47:281–295. doi: 10.1021/ar3002798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He G, Wang B, Nack WA, Chen G. Syntheses and transformations of α-amino acids via palladium-catalyzed auxiliary-directed sp3 C–H functionalization. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016;49:635–645. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moselage M, Li J, Ackermann L. Cobalt-catalyzed C–H activation. ACS Catal. 2016;6:498–525. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.5b02344. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daugulis O, Roane J, Tran LD. Bidentate, monoanionic auxiliary-directed functionalization of carbon–hydrogen bonds. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015;48:1053–1064. doi: 10.1021/ar5004626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wencel-Delord J, Glorius F. C–H bond activation enables the rapid construction and late-stage diversification of functional molecules. Nat. Chem. 2013;5:369–375. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeung CS, Dong VM. Catalytic dehydrogenative cross-coupling: forming carbon−carbon bonds by oxidizing two carbon−hydrogen bonds. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:1215–1292. doi: 10.1021/cr100280d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li J, Ackermann L. C–H activation: following directions. Nat. Chem. 2015;7:686–687. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Juliá-Hernández F, Simonetti M, Larrosa I. Metalation dictates remote regioselectivity: ruthenium-catalyzed functionalization of meta CAr−H bonds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:11458–11460. doi: 10.1002/anie.201306425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leow D, Li G, Mei TS, Yu JQ. Activation of remote meta-C–H bonds assisted by an end-on template. Nature. 2012;486:518–522. doi: 10.1038/nature11158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang RY, Li G, Yu JQ. Conformation-induced remote meta-C–H activation of amines. Nature. 2014;507:215–220. doi: 10.1038/nature12963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bera M, Maji A, Sahoo SK, Maiti D. Palladium(II)-catalyzed meta-C−H olefination: constructing multisubstituted arenes through homo-diolefination and sequential hetero-diolefination. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:8515–8519. doi: 10.1002/anie.201503112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Phipps RJ, Gaunt MJ. A meta-selective copper-catalyzed C–H bond arylation. Science. 2009;323:1593–1597. doi: 10.1126/science.1169975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duong HA, Gilligan E, Cooke ML, Phipps RJ, Gaunt MJ. Copper(II)-catalyzed meta-selective direct arylation of α-aryl carbonyl compounds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:463–466. doi: 10.1002/anie.201004704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fan Z, Ni J, Zhang A. Meta-selective CAr–H nitration of arenes through a Ru3(CO)12-catalyzed ortho-metalation strategy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:8470–8475. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b03402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu Q, Hu LA, Wang Y, Zheng S, Huang J. Directed meta-selective bromination of arenes with ruthenium catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:15284–15288. doi: 10.1002/anie.201507100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teskey CJ, Lui AYW, Greaney MF. Ruthenium-catalyzed meta-selective C–H bromination. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:11677–11680. doi: 10.1002/anie.201504390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paterson AJ, John-Campbell S, Mahon MF, Press NJ, Frost CG. Catalytic meta-selective C–H functionalization to construct quaternary carbon centres. Chem. Commun. 2015;51:12807–12810. doi: 10.1039/C5CC03951G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frost CG, Paterson AJ. Directing remote meta-C–H functionalization with cleavable auxiliaries. ACS Cent. Sci. 2015;1:418–419. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.5b00358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hofmann N, Ackermann L. meta-Selective C–H bond alkylation with secondary alkyl halides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:5877–5884. doi: 10.1021/ja401466y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saidi O, et al. Ruthenium-catalyzed meta sulfonation of 2-phenylpyridines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:19298–19301. doi: 10.1021/ja208286b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ackermann L, Hofmann N, Vicente R. Carboxylate-assisted ruthenium-catalyzed direct alkylations of ketimines. Org. Lett. 2011;13:1875–1877. doi: 10.1021/ol200366n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruan ZX, et al. Ruthenium(II)-catalyzed meta C−H mono- and difluoromethylations by phosphine/carboxylate cooperation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:2045–2049. doi: 10.1002/anie.201611595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li ZY, et al. Ruthenium-catalyzed meta-selective C−H mono- and difluoromethylation of arenes through ortho-metalation strategy. Chem. Eur. J. 2017;23:3285–3290. doi: 10.1002/chem.201700354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dey A, Maity S, Maiti D. Reaching the south: metal-catalyzed transformation of the aromatic para-position. Chem. Commun. 2016;52:12398–12414. doi: 10.1039/C6CC05235E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao Y, Yan H, Lu H, Huang Z, Lei AW. para-Selective C–H bond functionalization of iodobenzenes. Chem. Commun. 2016;52:11366–11369. doi: 10.1039/C6CC05832A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ciana CL, Phipps RJ, Brandt JR, Meyer FM, Gaunt MJ. A highly para-selective copper(II)-catalyzed direct arylation of aniline and phenol derivatives. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:458–462. doi: 10.1002/anie.201004703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ball LT, Lloyd-Jones GC, Russell CA. Gold-catalyzed oxidative coupling of arylsilanes and arenes: origin of selectivity and improved precatalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:254–264. doi: 10.1021/ja408712e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cambeiro XC, Boorman TC, Lu P, Larrosa I. Redox-controlled selectivity of C−H activation in the oxidative cross-coupling of arenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:1781–1784. doi: 10.1002/anie.201209007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ball LT, Lloyd-Jones GC, Russell CA. Gold-catalyzed direct arylation. Science. 2012;337:1644–1648. doi: 10.1126/science.1225709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosewall CF, Sibbald QA, Liskin DV, Michael FE. Palladium-catalyzed carboamination of alkenes promoted by N-fluorobenzenesulfonimide via C−H activation of arenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:9488–9489. doi: 10.1021/ja9031659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leitch JA, et al. Ruthenium-catalyzed para-selective C−H alkylation of aniline derivatives. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:15131–15135. doi: 10.1002/anie.201708961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng C, Hartwig JF. Rhodium-catalyzed intermolecular C–H silylation of arenes with high steric regiocontrol. Science. 2014;343:853–857. doi: 10.1126/science.1248042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saito Y, Segawa Y, Itami K. para-C–H borylation of benzene derivatives by a bulky iridium catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:5193–5198. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b02052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang X, Leow D, Yu JQ. Pd(II)-catalyzed para-selective C–H arylation of monosubstituted arenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:13864–13867. doi: 10.1021/ja206572w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yadagiri D, Anbarasan P. Rhodium catalyzed direct arylation of α-diazoimines. Org. Lett. 2016;16:2510–2513. doi: 10.1021/ol500874p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu DG, de Azambuja F, Glorius F. Direct functionalization with complete and switchable positional control: free phenol as a role model. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:7710–7712. doi: 10.1002/anie.201403894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jia S, Xing D, Zhang D, Hu W. Catalytic asymmetric functionalization of aromatic C–H bonds by electrophilic trapping of metal-carbene-induced zwitterionic intermediates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:13098–13101. doi: 10.1002/anie.201406492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu Z, et al. Highly site-selective direct C–H bond functionalization of phenols with α-aryl-α-diazoacetates and diazooxindoles via gold catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:6904–6907. doi: 10.1021/ja503163k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cong X, Zeng X. Iron-catalyzed, chelation-induced remote C–H allylation of quinolines via 8-amido assistance. Org. Lett. 2014;16:3716–3719. doi: 10.1021/ol501534z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hu X, Martin D, Melaimi M, Bertrand G. Gold-catalyzed hydroarylation of alkenes with dialkylanilines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:13594–13597. doi: 10.1021/ja507788r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bag S, et al. Remote para-C–H functionalization of arenes by a D-shaped biphenyl template-based assembly. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:11888–11891. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b06793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun K, Li Y, Xiong T, Zhang J, Zhang Q. Palladium-catalyzed C−H aminations of anilides with N-fluorobenzenesulfonimide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:1694–1697. doi: 10.1021/ja1101695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Okumura S, et al. para-Selective alkylation of benzamides and aromatic ketones by cooperative nickel/aluminum catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:14699–14704. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b08767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ma B, et al. Highly para-selective C−H alkylation of benzene derivatives with 2,2,2-trifluoroethyl α-aryl-α-diazoesters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:2749–2753. doi: 10.1002/anie.201611809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Luan YX, et al. Amide-ligand-controlled highly para-selective arylation of monosubstituted simple arenes with arylboronic acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:1786–1789. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b12907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meanwell NA. Synopsis of some recent tactical application of bioisosteres in drug design. J. Med. Chem. 2011;54:2529–2591. doi: 10.1021/jm1013693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Purser S, Moore PR, Swallow S, Gouverneur V. Fluorine in medicinal chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008;37:320–330. doi: 10.1039/B610213C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Müller F, Faeh C, Diederich F. Fluorine in pharmaceuticals: looking beyond intuition. Science. 2007;317:1881–1886. doi: 10.1126/science.1131943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O’Hagan D. Understanding organofluorine chemistry. An introduction to the C-F bond. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008;37:308–319. doi: 10.1039/B711844A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Campbell MG, Ritter T. Modern carbon–fluorine bond forming reactions for aryl fluoride synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2015;115:612–633. doi: 10.1021/cr500366b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nenajdenko VG, Muzalevskiy VM, Shastin AV. Polyfluorinated ethanes as versatile fluorinated C2-building blocks for organic synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2015;115:973–1050. doi: 10.1021/cr500465n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ni CF, Hu M, Hu JB. Good partnership between sulfur and fluorine: sulfur-based fluorination and fluoroalkylation reagents for organic synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2015;115:765–825. doi: 10.1021/cr5002386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liang T, Neumann CN, Ritter T. Introduction of fluorine and fluorine-containing functional groups. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;2013:8214–8264. doi: 10.1002/anie.201206566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wan XB, et al. Highly selective C−H functionalization/halogenation of acetanilide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;128:7416–7417. doi: 10.1021/ja060232j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bedford RB, Haddow MF, Mitchell CJ, Webster RL. Mild C−H halogenation of anilides and the isolation of an unusual palladium(I)–palladium(II) species. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:5524–5527. doi: 10.1002/anie.201101606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gao P, et al. Iridium(III)-catalyzed direct arylation of C–H bonds with diaryliodonium salts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:12231–12240. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b06758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xia Y, Liu Z, Feng S, Zhang Y, Wang JB. Ir(III)-catalyzed aromatic C–H bond functionalization via metal carbene migratory insertion. J. Org. Chem. 2015;80:223–236. doi: 10.1021/jo5023102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ackermann L. Robust ruthenium(II)-catalyzed C–H arylations: carboxylate assistance for the efficient synthesis of angiotensin-II-receptor blockers. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2015;19:260–269. doi: 10.1021/op500330g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li B, Dixneuf PH. sp2 C–H bond activation in water and catalytic cross-coupling reactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013;42:5744–5767. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60020c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kitson. SL, Jones S, Watters W, Chen F, Madge D. Carbon-14 radiosynthesis of 4-(5-chloro-2-hydroxyphenyl)-3-(2-hydroxyethyl)-6-(trifluoromethyl)-[4-14C]quinolin-2(1H)-one (XEN-D0401), a novel BK channel activator. J. Label. Compd. Radiopharm. 2010;53:140–146. doi: 10.1002/jlcr.1740. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dai. H, Yu C, Lu C, Yan H. RhIII-catalyzed C–H allylation of amides and domino cycling synthesis of 3,4-dihydroisoquinolin-1(2H)-ones with N-bromosuccinimide. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2016;2016:1255–1259. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201501551. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kondratov LS, et al. Radical reactions of alkyl 2-bromo-2,2-difluoroacetates with vinyl ethers: “Omitted” examples and application for the synthesis of 3,3-difluoro-GABA. J. Org. Chem. 2015;80:12258–12264. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.5b02171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Crossley SWM, Obradors C, Martinez R, Shenvi RA. Mn-, Fe-, and Co-catalyzed radical hydrofunctionalizations of olefins. Chem. Rev. 2016;116:8912–9000. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Streuff J, Gansäuer A. Metal-catalyzed β-functionalization of michael acceptors through reductive radical addition reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:14232–14242. doi: 10.1002/anie.201505231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files(PDF 49 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all relevant data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers 1513022. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.