Abstract

Background

Bone metastases and lytic lesions due to multiple myeloma are common in advanced cancer and can lead to debilitating complications (skeletal-related events [SREs]), including requirement for radiation to bone. Despite the high frequency of radiation to bone in patients with metastatic bone disease, our knowledge of associated healthcare resource utilization (HRU) is limited.

Methods

This retrospective study estimated HRU following radiation to bone in Austria, the Czech Republic, Finland, Greece, Poland, Portugal, Sweden and Switzerland. Eligible patients were ≥ 20 years old, had bone metastases secondary to breast, lung or prostate cancer, or bone lesions associated with multiple myeloma, and had received radiation to bone between 1 July 2004 and 1 July 2009. HRU data were extracted from hospital patient charts from 3.5 months before the index SRE (radiation to bone preceded by a SRE-free period of ≥ 6.5 months) until 3 months after the last SRE that the patient experienced during the study period.

Results

In total, 482 patients were included. The number of inpatient stays increased from baseline by a mean of 0.52 (standard deviation [SD] 1.17) stays per radiation to bone event and the duration of stays increased by a mean of 7.8 (SD 14.8) days. Outpatient visits increased by a mean of 4.24 (SD 6.57) visits and procedures by a mean of 8.51 (SD 7.46) procedures.

Conclusion

HRU increased following radiation to bone across all countries studied. Agents that prevent severe pain and delay the need for radiation have the potential to reduce the burden imposed on healthcare resources and patients.

Keywords: Bone pain, Bone metastases, Health resource utilization, Radiation to bone, Skeletal-related event

1. Introduction

Bone metastases affect approximately 35% of patients with advanced lung cancer [1], up to 73% of patients with advanced breast cancer [1] and more than 90% of patients with advanced prostate cancer [2]. In addition, lytic bone lesions affect almost all patients with multiple myeloma [1]. Bone complications or skeletal-related events (SREs; including radiation to bone, surgery to bone, pathologic fracture and spinal cord compression) can drastically reduce patients’ quality of life [1], and increase the risk of death [1].

Bone metastases secondary to solid tumours and bone lesions due to multiple myeloma are a common cause of cancer-related pain [1], and approximately half of patients with metastatic bone disease experience moderate–severe pain [3]. The World Health Organization's cancer pain ladder recommends that all patients experiencing moderate-to-severe pain should receive opioids [4]. Despite these recommendations, treatment of cancer pain is often inadequate [3]; indeed, an integrated analysis of three large clinical studies of patients with bone metastases showed that less than one-third of patients with moderate-to-severe pain were treated with strong opioids [3].

A frequent, effective and valuable treatment option for bone pain is palliative radiotherapy, which is recommended by clinical guidelines for the treatment of localized bone pain in patients with bone metastases [5]. Improvement in pain following radiation to bone is reported by up to 80% of patients [6]; however, it may take up to 12–20 weeks to achieve complete pain relief [7]. Palliative radiotherapy is also useful in preserving function and maintaining skeletal integrity and is often used to stabilize symptomatic pathologic fractures or spinal cord compressions [6]. It can also be used following surgery to bone to minimize disease progression and to improve functional status [8].

Data from placebo arms of randomized clinical trials of patients with prostate cancer or with lung cancer and other solid tumours (excluding breast and prostate) show that radiation to bone is the most common SRE [9], [10]. Despite the high frequency of radiation to bone in patients with metastatic bone disease, our knowledge of its impact on health resource utilization (HRU), particularly in Europe, is limited. A large multinational study in Germany, Spain, Italy and the United Kingdom (UK) demonstrated that the time following radiation to bone is associated with considerable HRU and costs [11], and single-centre studies in Portugal and Spain also showed that this SRE contributes considerably to HRU [12], [13]. However, data from other countries across Europe are scarce.

Determining the level of HRU associated with the time following radiation to bone will help to determine optimal patient management. The primary aim of this study was to provide estimates of HRU associated with all types of SRE in eight European countries; here, we report data specifically relating to the time following radiation to bone.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Patients and study design

This retrospective study involved patients from Austria, the Czech Republic, Finland, Greece, Poland, Portugal, Sweden and Switzerland. To be included in this analysis, patients had to be at least 20 years of age, have bone metastases secondary to breast, lung or prostate cancer, or bone lesions due to multiple myeloma, and have experienced an index SRE of radiation to bone between 1 July 2004 and 1 July 2009. An index SRE was defined as a radiation to bone event preceded by a SRE-free period of at least 6.5 months; this ensured that radiation to bone was only included as an index SRE when it occurred in isolation, and not when it was used as a follow-up procedure after a different type of SRE. Per protocol, patients who died within 2 weeks of their index SRE and those whose chart data were of insufficient quality were excluded to avoid a potential underreporting of HRU. In addition, patients were excluded if they had, at any time, participated in a denosumab clinical trial programme. Consecutive patient charts were screened and data for those fulfilling the inclusion/exclusion criteria were captured until the pre-specified target of 60 patients was reached in each country.

This study was approved in accordance with each country's official governmental and institutional ethical regulations. If requested by institutional ethics committees, patients were asked to provide informed consent; however, this was generally not required.

2.2. Data collection

Data were collected from individual hospital patient charts. Patients’ baseline demographics and disease characteristics were captured in addition to primary HRU outcome measures, including inpatient hospital stays (number and duration), procedures (number and type [e.g. imaging, outpatient surgery, etc.]), and the number of outpatient visits, emergency room visits and day-care hospital visits (patients who required more prolonged treatment or investigations than outpatients, but did not require an overnight stay).

2.3. SREs included

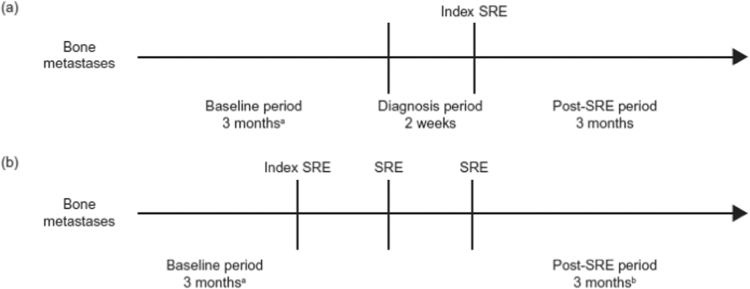

For patients with a single index SRE, data were extracted from hospital patient charts from 3.5 months before to 3 months after the index SRE (Fig. 1a). For patients with multiple SREs, the data extraction period was extended until 3 months after the last SRE experienced by the patient during the study period (Fig. 1b). There was no limit to the number of SREs included in the post-index SRE period.

Fig. 1.

Study design and data collection for patients with (a) one SRE and (b) multiple SREs. aTo ensure lack of carry-over of HRU from a previous SRE that occurred before the 3.5-month pre-SRE period, a clean window of an additional 3 months without an SRE was required. bFor multiple SREs, the post-index SRE observational period was extended to 3 months following the last observed SRE. To ensure that any HRU used to diagnose the SRE is included in the HRU burden for the SRE, there is a 2-week diagnosis period immediately before the SRE. Estimate of HRU associated with SRE = (post-SRE period + diagnosis period) − baseline period. Data were adjusted to allow for the different lengths of the baseline and post-baseline periods. When multiple SREs were observed at the same anatomical site and within a 21-day window, HRU was attributed to the index SRE. When multiple SREs were observed at the same anatomical site but outside a 21-day window, or multiple SREs were observed at different anatomical sites on the same or different days, the expert panel attributed HRU to the respective SRE. HRU, healthcare resource utilization; SRE, skeletal-related event.

2.4. Attribution of HRU to SREs

A period of 3 months, occurring 3.5 months before the index SRE, was used to establish baseline HRU and a 14-day (0.5-month) period was included immediately before the index SRE to allow for any diagnostic HRU. To ensure there was no carry-over of HRU from any SREs that occurred before the 3.5-month pre-index SRE period, a preceding SRE-free period of 3 months was required (Fig. 1). In line with time windows used in pivotal clinical trials [14], SREs that occurred at the same anatomical site but were at least 21 days apart were considered as separate events. To avoid underestimating HRU, if a SRE occurred as a result of another SRE, when multiple SREs were present at the same anatomical site and within a 21-day window, the total HRU was attributed to the index SRE. Unlinked SREs (i.e. those at different anatomical sites, or the same anatomical site but outside of the 21-day time window) were reviewed by an expert panel to ensure that HRU was attributed appropriately. Across the entire study, the expert panel was required to attribute HRU to unlinked SREs in only approximately 5% of the total number of cases.

2.5. Statistical analysis

After adjustment for differences in the lengths of the baseline and post-baseline periods, the change from baseline was used to estimate HRU associated with the SRE. Descriptive statistics for continuous data were summarized by the mean and standard deviation (SD) to indicate the total resources used at a population level.

3. Results

3.1. Study population

In total, 482 patients with an index SRE of radiation to bone were included (Table 1): 57 patients were enrolled in Austria, 59 patients were enrolled in each of the Czech Republic, Greece, Portugal and Switzerland, 60 patients in Finland, 62 patients in Sweden and 67 patients in Poland. Baseline demographics and disease characteristics were generally similar across countries, but there were some exceptions. The majority of patients were men in all countries apart from Austria (26.3%) and the Czech Republic (45.8%). Sweden had a considerably larger proportion of patients aged 75 years or older (35.5%) than the other seven countries (range: 6.8–16.7%). Overall, most patients had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) status of 1 (50.1%) or 2 (25.1%); patients in Austria were more likely to have an ECOG status of 0 (51.4%) than patients in the other countries (range: 3.1–29.1%). Breast cancer was the predominant cancer type among enrolled patients in Austria, the Czech Republic and Poland (41.8–63.2%), whereas in Finland, Sweden and Switzerland it was prostate cancer (39.0–56.7%), and in Greece and Portugal over half of the patients had lung cancer (57.6% and 50.8%, respectively). A minority of patients had multiple SREs (20.7% overall); however, this proportion was much higher in Sweden (50.0%) and Finland (41.7%) than in other countries (range: 6.0–22.0). The median time since diagnosis of bone metastases/bone lesions was 2.5 months in the overall population, with the longest median times in Switzerland (17.7 months) and Sweden (11.3 months), and the shortest times in Poland (1.4 months) and Portugal (1.3 months). In patients with solid tumours, across Austria, Greece, Poland and Portugal, almost all patients had bone metastases at only one or two anatomical sites (90.7–100%), whereas in the Czech Republic, Finland, Sweden and Switzerland, fewer patients had bone metastases confined to one or two sites (60.4–67.8%).

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics.

| All countries (N = 482) | Austria (n = 57) | Czech Republic (n = 59) | Finland (n = 60) | Greece (n = 59) | Poland (n = 67) | Portugal (n = 59) | Sweden (n = 62) | Switzerland (n = 59) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 63.2 (11.3) | 59.6 (12.4) | 64.5 (11.3) | 65.7 (9.2) | 60.5 (11.2) | 61.4 (11.1) | 61.9 (11.9) | 70.0 (10.8) | 62.2 (9.2) |

| Female, n (%) | 200 (41.5) | 42 (73.7) | 32 (54.2) | 16 (26.7) | 19 (32.2) | 31 (46.3) | 21 (35.6) | 16 (25.8) | 23 (39.0) |

| Age group, n (%) | |||||||||

| <65 years | 257 (53.3) | 35 (61.4) | 26 (44.1) | 29 (48.3) | 33 (55.9) | 44 (65.7) | 35 (59.3) | 19 (30.6) | 36 (61.0) |

| ≥65 years | 225 (46.7) | 22 (38.6) | 33 (55.9) | 31 (51.7) | 26 (44.1) | 23 (34.3) | 24 (40.7) | 43 (69.4) | 23 (39.0) |

| ≥75 years | 73 (15.1) | 5 (8.8) | 9 (15.3) | 10 (16.7) | 4 (6.8) | 9 (13.4) | 8 (13.6) | 22 (35.5) | 6 (10.2) |

| ECOG status, n (%) | |||||||||

| 0 | 62 (12.9) | 18 (31.6) | 5 (8.5) | 3 (5.0) | 8 (13.6) | 2 (3.0) | 3 (5.1) | 7 (11.3) | 16 (27.1) |

| 1 | 190 (39.4) | 13 (22.8) | 35 (59.3) | 25 (41.7) | 25 (42.4) | 31 (46.3) | 23 (39.0) | 10 (16.1) | 28 (47.5) |

| 2 | 95 (19.7) | 4 (7.0) | 15 (25.4) | 12 (20.0) | 12 (20.3) | 24 (35.8) | 9 (15.3) | 13 (21.0) | 6 (10.2) |

| 3 | 31 (6.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.4) | 7 (11.7) | 2 (3.4) | 7 (10.4) | 3 (5.1) | 5 (8.1) | 5 (8.5) |

| 4 | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Unknown | 103 (21.4) | 22 (38.6) | 2 (3.4) | 13 (21.7) | 12 (20.3) | 3 (4.5) | 20 (33.9) | 27 (43.5) | 4 (6.8) |

| Primary tumour diagnosis, n (%) | |||||||||

| Breast cancer | 151 (31.3) | 36 (63.2) | 30 (50.8) | 10 (16.7) | 15 (25.4) | 28 (41.8) | 13 (22.0) | 5 (8.1) | 14 (23.7) |

| Lung cancer | 112 (23.2) | 11 (19.3) | 4 (6.8) | 4 (6.7) | 34 (57.6) | 14 (20.9) | 30 (50.8) | 3 (4.8) | 12 (20.3) |

| Prostate cancer | 158 (32.8) | 2 (3.5) | 25 (42.4) | 34 (56.7) | 5 (8.5) | 21 (31.3) | 15 (25.4) | 33 (53.2) | 23 (39.0) |

| Multiple myeloma | 61 (12.7) | 8 (14.0) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (20.0) | 5 (8.5) | 4 (6.0) | 1 (1.7) | 21 (33.9) | 10 (16.9) |

| SRE status, n (%) | |||||||||

| Single | 382 (79.3) | 53 (93.0) | 54 (91.5) | 35 (58.3) | 47 (79.7) | 63 (94.0) | 53 (89.8) | 31 (50.0) | 46 (78.0) |

| Multiple | 100 (20.7) | 4 (7.0) | 5 (8.5) | 25 (41.7) | 12 (20.3) | 4 (6.0) | 6 (10.2) | 31 (50.0) | 13 (22.0) |

| Time since diagnosis of bone metastases, months | |||||||||

| n | 411 | 43 | 59 | 48 | 53 | 63 | 56 | 41 | 48 |

| Mean (SD) | 11.0 (17.0) | 9.8 (20.1) | 12.7 (16.5) | 17.3 (24.3) | 5.8 (8.8) | 3.8 (5.9) | 4.9 (8.8) | 16.8 (18.5) | 20.8 (19.8) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 2.5 (0.8, 14.3) | 2.1 (0.4, 6.3) | 4.5 (0.9, 17.8) | 5.1 (1.4, 23.5) | 1.8 (0.5, 7.7) | 1.4 (0.6, 4.9) | 1.3 (0.7, 5.6) | 11.3 (1.6, 26.0) | 17.7 (1.6, 35.2) |

| Bone metastases sites, n (%) | |||||||||

| 1–2 | 342 (71.0) | 47 (82.5) | 40 (67.8) | 29 (48.3) | 49 (83.1) | 63 (94.0) | 58 (98.3) | 26 (41.9) | 30 (50.8) |

| 3–4 | 35 (7.3) | 1 (1.8) | 11 (18.6) | 6 (10.0) | 3 (5.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (14.5) | 5 (8.5) |

| ≥5 | 44 (9.1) | 1 (1.8) | 8 (13.6) | 13 (21.7) | 2 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (9.7) | 14 (23.7) |

| Missing | 61 (12.7) | 8 (14.0) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (20.0) | 5 (8.5) | 4 (6.0) | 1 (1.7) | 21 (33.9) | 10 (16.9) |

ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; Q, quartile; SD, standard deviation; SRE, skeletal-related event.

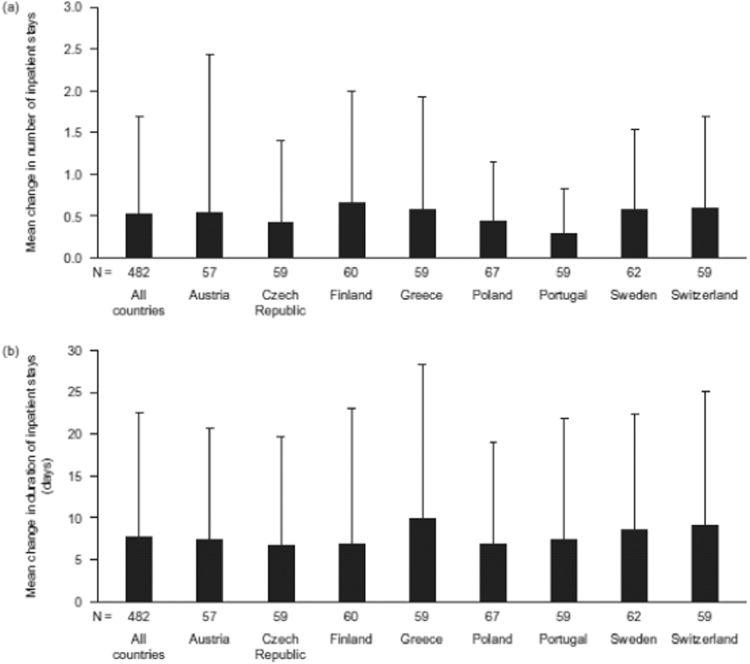

3.2. Change from baseline in the number and duration of inpatient stays

Across all countries, comparing the overall number of inpatient stays during the baseline period with the number of stays in the period after the index SRE, the number of inpatient stays increased in frequency by a mean of 0.52 (SD 1.17) stays following each radiation to bone event across the countries (Fig. 2a). The biggest increase was seen in Finland (0.67 [1.33]) and the smallest in Portugal (0.30 [0.54]). The rise in the number of inpatient stays was accompanied by a mean increase in the duration of stays of 7.8 (14.8) days (Fig. 2b), which was similar across all countries (range: 6.6–9.9 days).

Fig. 2.

Mean change from baseline in (a) the number and (b) the duration of inpatient stays per radiation to bone event. Data are shown as mean (+ standard deviation). N, number of patients enrolled from each country.

Similarly, increases in the number of inpatient stays were documented most frequently for oncology units across all countries, with a mean increase in frequency of 0.16 (SD 0.67). Large increases in the number of stays were also documented for radiation units (0.14 [SD 0.40]) and internal medicine units (0.10 [SD 0.54]). Similar patterns were seen for increases in the duration of stays, with the largest mean increases seen in radiation units (1.9 [SD 6.0]), followed by oncology units (1.8 [SD 7.3]) and internal medicine units (1.1 [SD 6.4]). Overall, urology, haematology and general units saw only small increases in the number and duration of inpatient stays (data not shown).

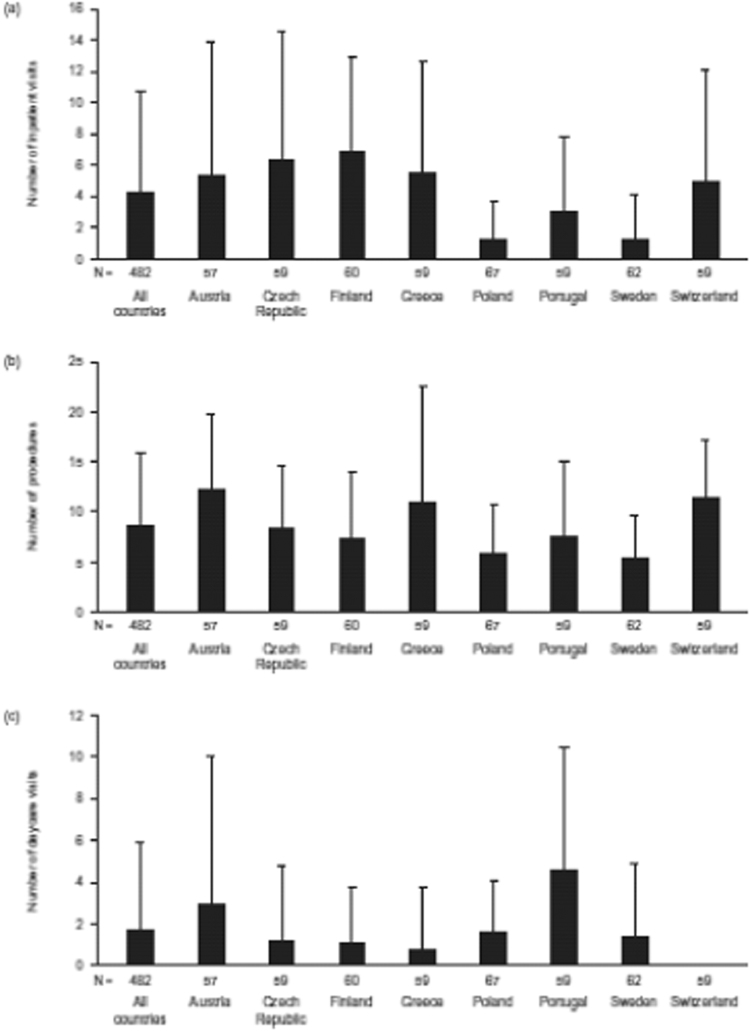

3.3. Change from baseline in the number of outpatient visits and procedures

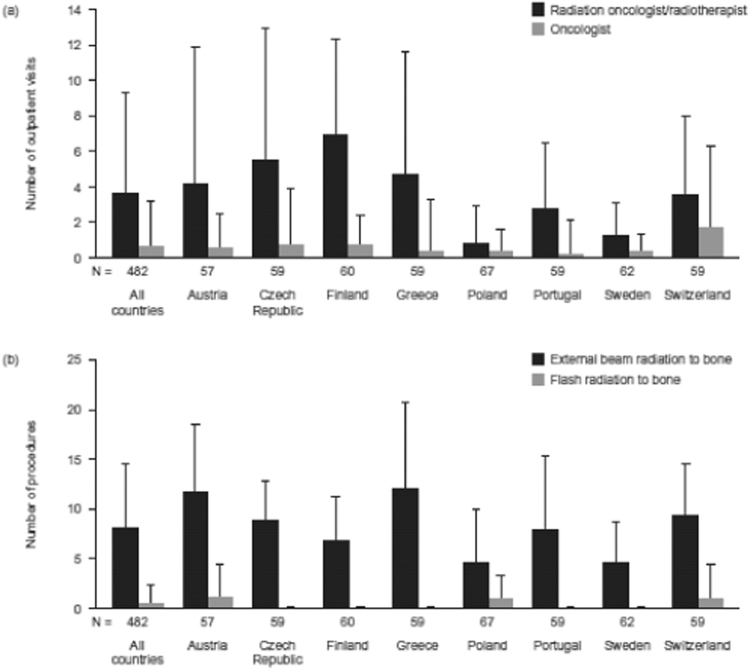

Collectively, the number of outpatient visits increased from baseline by a mean of 4.24 (SD 6.57) visits per radiation to bone event (Fig. 3a). Compared with the other countries participating in the study, Sweden (1.19 [2.80]) and Poland (1.23 [2.52]) reported smaller increases in the number of outpatient visits. The largest increases in the number of outpatient visits were seen in Finland (6.95 [5.95]) and the Czech Republic (6.33 [8.31]). ‘Visits to a radiation oncologist/radiotherapist’ was the most common reason for the increase in overall outpatient visits (mean increase of 3.65 [5.66] visits) and for each participating country (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 3.

Mean change from baseline in the number of (a) outpatient visits, (b) procedures and (c) day-care visits per radiation to bone event. Data are shown as mean (+ standard deviation). N, number of patients enrolled from each country.

Fig. 4.

Mean change from baseline in the number of (a) outpatient visits and (b) procedures per radiation to bone event by the most common provider types or procedures. Data are shown as mean (+ standard deviation). N, number of patients enrolled from each country.

Overall, the number of procedures (Fig. 3b) increased by 8.51 (SD 7.46). Austria (12.15 [7.57] procedures), Switzerland (811.41 [5.73]) and Greece (11.12 [11.36]) reported larger increases than the other countries included in the study. Again, increases were lowest in Sweden (5.32 [4.50]) and Poland (5.74 [4.88]). External beam radiation was the procedure type showing the greatest increase in frequency, with a mean increase of 8.07 (6.51) procedures (Fig. 4b).

3.4. Change from baseline in the number of day-care and emergency room visits

The number of day-care visits also rose, with an overall mean increase from baseline of 1.64 (SD 4.26) visits per radiation to bone event (Fig. 3c). Portugal (4.50 [6.03]) and Austria (2.97 [7.09]) reported larger increases than other countries, whereas no change from baseline was observed in Switzerland. Increases in the number of emergency room visits were generally infrequent, with an overall increase of 0.10 (0.74).

4. Discussion

This study of a cross-section of patients with bone metastases from eight European countries demonstrated that the time following radiation to bone is associated with an increased HRU burden. Compared with baseline, the largest increases in HRU were due to increases in the numbers of outpatient visits and procedures; however, considerable increases in the number and duration of inpatient stays were also seen.

Although radiation to bone is less frequently associated with a need for inpatient stays than other SREs [11], this study showed that both the number and the duration of inpatient stays increased from baseline following a radiation to bone event. This suggests that patients may have experienced complications requiring an overnight stay, or may have received treatment with multiple fractions that required one or more overnight stays. Alternatively, overnight hospital stays may have been necessitated by long distance travel to the clinic, old age or poor performance status.

Increases in HRU measures were seen across all eight countries included in this study, although there were some notable variations in the patterns of HRU. While the change in duration of inpatient stays was fairly consistent across the countries, there were some differences in the change in the number of stays. For example, the mean increase from baseline in Finland was over twice that reported in Portugal. These differences may reflect country-specific approaches to clinical practice, or they could be a result of variations across the countries in baseline patient characteristics. A change in the number of day-care visits was observed in all countries apart from Switzerland, reflecting the preference for alternative facilities in Switzerland.

The change in the number of outpatient visits also varied across countries, with much smaller increases in Poland and Sweden than in the other countries. A similar pattern was seen for the change in the number of procedures. The numbers of visits and procedures can be used as a proxy to estimate the number of fractions each patient received. These differences may reflect country-specific preferences for single-fraction or multiple-fraction radiotherapy: it can be speculated that countries with fewer outpatient visits and procedures may use single-fraction radiotherapy more frequently than countries with higher levels of HRU. However, radiotherapy practices vary across countries [15]. The type of reimbursement system appears to influence the predominant fractionation regimen: countries that employ a budget and case financing reimbursement system, such as the UK, Spain and the Netherlands, use a lower total number of fractions than countries that use a fee-for-service system, such as Germany and Switzerland [16]. The low number of visits in Sweden could also reflect the preference for patients to be managed by nurses. In our study, visits to nurses were only included if medical care was provided, so routine follow-up visits may not be accounted for.

While our study is the first to describe in detail the HRU associated with the time following radiation to bone in Austria, the Czech Republic, Finland, Greece, Poland, Portugal, Sweden and Switzerland, studies in other countries have shown similar contributions to HRU in patients with bone metastases. A prospective, multicentre study in the United States of America in patients with bone metastases secondary to breast, prostate or lung cancer, and in patients with multiple myeloma and bone lesions, reported that each radiation to bone event resulted in a mean of 10 outpatient visits, 12 procedures and a duration of inpatient stay of 8 days [17]. In the European cohort (UK, Germany, Italy and Spain) of the same study, the time following radiation to bone was associated with a small increase in the number of inpatient stays (0.1–0.2). The duration of those stays, however, was considerable (10–22 days) [11]. Another study in Spain also found that inpatient stays attributed to the time following radiation to bone are lengthy (13–19 days) [13].

HRU resulting from the time following radiation to bone is associated with substantial costs to healthcare providers. Although the time following individual radiation to bone events is less costly than other SREs [11], radiation to bone is one of the most common SREs in patients with bone metastases [9], [10]; as such, it accounts for a large proportion of SRE-associated costs.

Despite its value, radiation to bone can also have an impact on patients. Across Europe, there is wide variation in the availability of radiotherapy facilities [18], and many patients and family members or carers are required to travel long distances for a relatively short radiotherapy session. Travel distance negatively correlates with uptake of radiotherapy [19], and it appears that this factor can impose an additional burden on patients. Given the number of procedures per radiation to bone event, it appears that the majority of patients in our study received multiple-fraction radiotherapy. A literature review confirmed that, despite evidence for the equivalent efficacy profile of single-fraction radiotherapy and lower medical costs, current practices and preferences favour multiple fractions for the treatment of bone metastases, both in Europe and in the USA [15]. Increasing the use of single-fraction treatment may decrease HRU by reducing the need for multiple outpatient visits and procedures, and could improve the convenience of treatment for patients.

In addition to difficulties in accessing treatment, like all treatment options, radiation to bone is also associated with some adverse effects. Although radiotherapy can effectively reduce bone pain [5], [6], it can often be associated with fatigue [20] and can cause pain flares immediately after treatment in approximately one-third of patients [21]. Patients may also experience radiation dermatitis, which can range from mild erythema to skin ulceration [20]. Vomiting and diarrhoea have been reported following radiation [20].

Such problems with travelling to treatment centres and experiencing adverse effects following treatment may reduce patients’ quality of life. Data from a placebo-controlled trial of zoledronic acid in patients with bone metastases secondary to prostate cancer indicated that, while radiation to bone decreased pain scores, it also resulted in a larger decrease in quality of life scores (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General [FACT-G]) than seen with other SRE types. Thus, radiation to bone negatively affected physical, functional and emotional well-being [22]; however, a smaller study of patients with bone metastases found that overall quality of life, as assessed by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C15-PAL questionnaire, improved in those whose pain improved following radiation to bone [23]. Clearly there is a need for further research to improve our understanding of the benefit and the impact of radiotherapy on patients’ well-being.

Bone-targeted treatments can reduce bone pain, improve quality of life and decrease the incidence of SREs, including radiation to bone, thereby reducing HRU. Studies have shown that bisphosphonates and the RANK ligand inhibitor denosumab alleviate bone pain and delay the need for radiation to bone in patients with bone metastases [3], [24]. An integrated analysis of three identically designed phase 3 trials showed that clinically relevant increases in pain were experienced by significantly fewer patients receiving denosumab than those receiving zoledronic acid, the most commonly used bisphosphonate in patients with bone metastases. This was true across a variety of tumour types (including breast cancer, prostate cancer or other solid tumours, and multiple myeloma) [3]. Radionuclide therapy is also an option for patients with bone metastases, especially if bone pain is not localized and tumour-specific treatment seems to be ineffective. The β-emitting radionuclides samarium-153 and strontium-89 reduce pain in patients with bone metastases [2]. The recently approved α-emitter radium-223 reduced the need for radiation to bone compared with placebo in a phase 3 trial of patients with prostate cancer [2]. Newer antineoplastic agents have also been shown to reduce the incidence of SREs in patients with prostate cancer: the anti-androgens enzalutamide and abiraterone acetate reduced pain in placebo-controlled phase 3 trials in patients with prostate cancer who had previously received docetaxel [9], [25]. Systemic agents may be particularly useful in patients with multiple bone metastases, and focal palliative radiation therapy can then be considered for specific painful lesions. Furthermore, many of these systemic agents also have the advantage of preventing or delaying other types of SRE [9], [14], [25], and therefore have the potential to reduce HRU and associated costs.

This study has a number of limitations. Although the study protocol provided clear guidance on how to select patient charts for inclusion, some selection bias may have occurred. A selection bias was observed at the centre in Finland, because patients with radiation to bone were enrolled only from palliative wards. Therefore, associated HRU may have been higher than expected due to the increasing levels of care required when patients neared end of life. Across all countries, the median time since diagnosis of bone metastases or bone lesions was 2.5 months, which correlates with the observation that the requirement for radiation to bone often coincides with the diagnosis of metastases or lesions. As such, data captured may have included the myriad of diagnostic and treatment procedures surrounding the diagnosis of bone metastases or bone lesions; however, given the before-after design of this study, it could be foreseen that our analysis would therefore be conservative because of the high HRU during the diagnosis period.

It is also possible that the sites selected for inclusion may not have been representative of the whole country. In addition, the data from this study are right-censored because SRE-related HRU could have occurred after the 3-month data collection period and our study may therefore have underestimated the HRU associated with time following radiation to bone. Finally, the exclusion of patients who died within 2 weeks of their index SRE could mean that levels of HRU are not representative of such end-stage patients.

5. Conclusions

Our study highlights the considerable burden that radiation to bone imposes on healthcare resources in Europe. Using agents to prevent SREs has the potential to reduce the number of inpatient hospital visits and procedures, benefiting healthcare systems and patients alike.

Acknowledgements

This study was sponsored by Amgen. We thank all of the investigators, coordinators and other staff who participated in this study.

Statistical support was provided by Tony Mossman who was a consultant employed by Amgen Ltd. Amgen is also grateful to Laurence Carpenter who was the study programmer for the present study.

Medical writing support was provided by Leon Adams from Watermeadow Medical and Kim Allcott from Oxford PharmaGenesis, funded by Amgen (Europe) GmbH. Editorial support was provided by Emma Booth, Sarah Petrig and Camilla Norrmen of Amgen (Europe) GmbH.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure of interest

Roger von Moos has received research grants from Amgen, Bayer, Merck Serono Roche, and participated in advisory boards with Amgen, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis and Roche. Jean-Jacques Body has received speaker and consulting fees from Amgen. Oliver Gunther was an employee of Amgen during this study. Evangelos Terpos has received honoraria from Amgen, Celgene, Janssen-Cilag and Medtronics. Yves Pascal Acklin and Jindrich Finek received consulting fees from Amgen. João Pereira has received honoraria from Amgen. Nikos Maniadakis has been a speaker for Amgen and received research grants from Abbott, AbbVie, Actelion, Amgen, Aventis, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen-Cilag, Novartis, Roche, Sevier and UCB. Guy Hechmati and Susan Talbot are employees of Amgen and own Amgen stock. Harm Sleeboom has received speaker fees from Amgen and Astellas.

Funding

Funding for this research was provided by Amgen (Europe) GmbH. Guy Hechmati, Oliver Gunther and Susan Talbot of Amgen were involved in the design of the study and the analysis and interpretation of the data. Funding for medical writing support was provided by Amgen (Europe) GmbH.

Contributor Information

Roger von Moos, Email: roger.vonmoos@ksgr.ch.

Jean-Jacques Body, Email: jean-jacques.body@chu-brugmann.be.

Oliver Guenther, Email: o.guenther@gmx.com.

Evangelos Terpos, Email: eterpos@hotmail.com.

Yves Pascal Acklin, Email: yvespascal.acklin@gmail.com.

Jindrich Finek, Email: finek@fnplzen.cz.

João Pereira, Email: jpereira@ensp.unl.pt.

Nikos Maniadakis, Email: nmaniadakis@esdy.edu.gr.

Guy Hechmati, Email: hechmati@amgen.com.

Susan Talbot, Email: sshepher@amgen.com.

Harm Sleeboom, Email: harm.sleeboom@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Coleman R.E. Metastatic bone disease: clinical features, pathophysiology and treatment strategies. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2001;27(3):165–176. doi: 10.1053/ctrv.2000.0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nilsson S. Radionuclide therapies in prostate cancer: integrating Radium-223 in the treatment of patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2016;18(2):14. doi: 10.1007/s11912-015-0495-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.von Moos R., Body J.J., Egerdie B., Stopeck A., Brown J.E., Damyanov D., Fallowfield L.J., Marx G., Cleeland C.S., Patrick D.L., Palazzo F.G., Qian Y., Braun A., Chung K. Pain and health-related quality of life in patients with advanced solid tumours and bone metastases: integrated results from three randomized, double-blind studies of denosumab and zoledronic acid. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(12):3497–3507. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1932-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO, WHO’s Cancer Pain Ladder for Adults. 〈http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/painladder/en〉. (accessed 26 January 2017).

- 5.Ripamonti C.I., Santini D., Maranzano E., Berti M., Roila F., Group E.G.W. Management of cancer pain: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann. Oncol. 2012;23(Suppl. 7) doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds233. (vii139–54) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lutz S., Berk L., Chang E., Chow E., Hahn C., Hoskin P., Howell D., Konski A., Kachnic L., Lo S., Sahgal A., Silverman L., von Gunten C., Mendel E., Vassil A., Bruner D.W., Hartsell W. Palliative radiotherapy for bone metastases: an ASTRO evidence-based guideline. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 2011;79(4):965–976. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tong D., Gillick L., Hendrickson F.R. The palliation of symptomatic osseous metastases: final results of the Study by the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group. Cancer. 1982;50(5):893–899. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820901)50:5<893::aid-cncr2820500515>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Townsend P.W., Rosenthal H.G., Smalley S.R., Cozad S.C., Hassanein R.E. Impact of postoperative radiation therapy and other perioperative factors on outcome after orthopedic stabilization of impending or pathologic fractures due to metastatic disease. J. Clin. Oncol. 1994;12(11):2345–2350. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.11.2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Logothetis C.J., Basch E., Molina A., Fizazi K., North S.A., Chi K.N., Jones R.J., Goodman O.B., Mainwaring P.N., Sternberg C.N., Efstathiou E., Gagnon D.D., Rothman M., Hao Y., Liu C.S., Kheoh T.S., Haqq C.M., Scher H.I., de Bono J.S. Effect of abiraterone acetate and prednisone compared with placebo and prednisone on pain control and skeletal-related events in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: exploratory analysis of data from the COU-AA-301 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(12):1210–1217. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70473-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saad F., McKiernan J., Eastham J. Rationale for zoledronic acid therapy in men with hormone-sensitive prostate cancer with or without bone metastasis. Urol. Oncol.: Semin. Orig. Investig. 2006;24(1):4–12. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2005.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hechmati G., Cure S., Gouepo A., Hoefeler H., Lorusso V., Luftner D., Duran I., Garzon-Rodriguez C., Ashcroft J., Wei R., Ghelani P., Bahl A. Cost of skeletal-related events in European patients with solid tumours and bone metastases: data from a prospective multinational observational study. J. Med. Econ. 2013;16(5):691–700. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2013.779921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Felix J., Andreozzi V., Soares M., Borrego P., Gervasio H., Moreira A., Costa L., Marcelo F., Peralta F., Furtado I., Pina F., Albuquerque C., Santos A., Passos-Coelho J.L. Hospital resource utilization and treatment cost of skeletal-related events in patients with metastatic breast or prostate cancer: estimation for the Portuguese National Health System. Value Health. 2011;14(4):499–505. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pockett R.D., Castellano D., McEwan P., Oglesby A., Barber B.L., Chung K. The hospital burden of disease associated with bone metastases and skeletal-related events in patients with breast cancer, lung cancer, or prostate cancer in Spain. Eur. J. Cancer Care. 2010;19:755–760. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2009.01135.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lipton A., Fizazi K., Stopeck A.T., Henry D.H., Brown J.E., Yardley D.A., Richardson G.E., Siena S., Maroto P., Clemens M., Bilynskyy B., Charu V., Beuzeboc P., Rader M., Viniegra M., Saad F., Ke C., Braun A., Jun S. Superiority of denosumab to zoledronic acid for prevention of skeletal-related events: a combined analysis of 3 pivotal, randomised, phase 3 trials. Eur. J. Cancer. 2012;48(16):3082–3092. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bradley N.M., Husted J., Sey M.S., Husain A.F., Sinclair E., Harris K., Chow E. Review of patterns of practice and patients' preferences in the treatment of bone metastases with palliative radiotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15(4):373–385. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0161-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lievens Y., Van den Bogaert W., Rijnders A., Kutcher G., Kesteloot K. Palliative radiotherapy practice within Western European countries: impact of the radiotherapy financing system? Radiother. Oncol. 2000;56(3):289–295. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(00)00214-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mahmood A., Ghazal H., Fink M.G., Patel M., Atchison C., Wei R., Suenaert P., Pinzone J.J., Slasor P., Chung K. Health-resource utilization attributable to skeletal-related events in patients with advanced cancers associated with bone metastases: results of the US cohort from a multicenter observational study. Community Oncol. 2012;9:148–157. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bentzen S.M., Heeren G., Cottier B., Slotman B., Glimelius B., Lievens Y., van den Bogaert W. Towards evidence-based guidelines for radiotherapy infrastructure and staffing needs in Europe: the ESTRO QUARTS project. Radiother. Oncol. 2005;75(3):355–365. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pagano E., Di Cuonzo D., Bona C., Baldi I., Gabriele P., Ricardi U., Rotta P., Bertetto O., Appiano S., Merletti F., Segnan N., Ciccone G. Accessibility as a major determinant of radiotherapy underutilization: a population based study. Health Policy. 2007;80(3):483–491. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berkey F.J. Managing the adverse effects of radiation therapy. Am. Fam. Physician. 2010;82(4):381–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loblaw D.A., Wu J.S., Kirkbride P., Panzarella T., Smith K., Aslanidis J., Warde P. Pain flare in patients with bone metastases after palliative radiotherapy--a nested randomized control trial. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15(4):451–455. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0166-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weinfurt K.P., Li Y., Castel L.D., Saad F., Timbie J.W., Glendenning G.A., Schulman K.A. The significance of skeletal-related events for the health-related quality of life of patients with metastatic prostate cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2005;16(4):579–584. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caissie A., Zeng L., Nguyen J., Zhang L., Jon F., Dennis K., Holden L., Culleton S., Koo K., Tsao M., Barnes E., Danjoux C., Sahgal A., Simmons C., Chow E. Assessment of health-related quality of life with the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C15-PAL after palliative radiotherapy of bone metastases. Clin. Oncol. (R. Coll. Radiol.) 2012;24(2):125–133. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saad F., Eastham J. Zoledronic Acid improves clinical outcomes when administered before onset of bone pain in patients with prostate cancer. Urology. 2010;76(5):1175–1181. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.European Medicines Agency, Xtandi (enzalutamide) Summary of Product Characteristics. 〈http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/002639/WC500144996.pdf〉. (accessed 26 January 2017).