Abstract

Urine haptoglobin (uHP) level prospectively predicts diabetic kidney disease (DKD) progression. Here, we aim to identify genetic determinants of uHP level and evaluate association with renal function in East Asians (EA) with type 2 diabetes (T2D). Genome-wide association study (GWAS) among 805 [236 Chinese (discovery) and 569 (57 Malay and 512 Chinese) (validation)] found that rs75444904/kgp16506790 variant was robustly associated with uHP level (MetaP = 1.21 × 10−60). rs75444904 correlates well with plasma HP protein levels and multimerization in EA but was not in perfect LD (r2 = 0.911 in Chinese, r2 = 0.536 in Malay) and is monomorphic in Europeans (1000 G data). Conditional probability analysis indicated weakening of effects but residual significant associations between rs75444904 and uHP when adjusted on HP structural variant (MetaP = 8.22 × 10−7). The rs75444904 variant was associated with DKD progression (OR = 1.77, P = 0.014) independent of traditional risk factors. In an additional validation-cohort of EA (410 end-stage renal disease (ESRD) cases and 1308 controls), rs75444904 was associated with ESRD (OR = 1.22, P = 0.036). Furthermore, increased risk of DKD progression (OR = 2.09, P = 0.007) with elevated uHP level through Mendelian randomisation analysis provide support for potential causal role of uHP in DKD progression in EA. However, further replication of our findings in larger study populations is warranted.

Introduction

Diabetes kidney disease (DKD) is the leading cause of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) globally. More than 50% of type 2 diabetes (T2D) patients in Asia have renal complications compared to 40% in Caucasians1. In Singapore, the prevalence of DKD is more than 50% in T2D patients and varies within subpopulation2. This is further complicated by the wide spectrum of renal progression in DKD patients, from very fast to moderate decline3. Therefore, this necessitates the need for prospective studies to identify biomarkers that allows stratification of DKD patients at high risk for rapid decline in renal function.

Haptoglobin (HP), an abundant serum protein, facilitates the removal of free haemoglobin (Hb) from circulation via macrophage-specific receptor CD163, preventing oxidative damage in tissues4–7. In observational studies, urine haptoglobin (uHP) has been associated with DKD, independent of other classical risk factors. For example, a study among Veterans Affairs Diabetes Trial (VADT) subjects demonstrated that increased uHP level is associated with early renal function decline in DKD patients8. In Asian cohorts, we confirmed that uHP predicted rapid DKD progression as good as, if not better than, albuminuria in T2D patients with preserved renal function (estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) > 60 mL/min/1.73 m2)9. In a recent study in Chinese cohort with median follow-up of 5.3 years, Yang et al., showed that T2D individuals with microalbuminuria and elevated uHP level are most susceptible to development of CKD, as defined by eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 10. However, whether this association of uHP and renal function is causal remains unclear. For example, unmeasured lifestyle factors such as smoking habits and physical activities might confound observational studies11,12. Furthermore, reverse causality could similarly lead to a statistically robust but non-causal relationship13.

Mendelian randomisation (MR) approach using genetic markers as instrumental variable (IV), allows for the assessment of causal relationship14. MR is analogous to a randomized clinical trial as genetic variants are randomly assorted at conception, precede any disease and less likely to be affected by confounding or reverse causality. The human HP (haptoglobin) gene has two common alleles, HP1 and HP2, which differs by the absence (HP1) or presence (HP2) of a 1.7 kbp intragenic duplication resulting in three potential HP genotypes (HP 1-1, HP 2-1 and HP 2-2) and corresponding proteins that are functionally distinct5,15,16. To our knowledge, the genetic determinant of uHP has not been explored although series of studies have shown that HP 2-2 genotype and rs2000999 in the HP gene were associated with serum haptoglobin levels17–21. However, the association between HP polymorphism and DKD remains conflicting among different ethnic populations22–27. Given that urine is an important potential source of kidney biomarker28, we aimed to first identify genetic determinant of uHP level and subsequently examine its association with decline in renal function to assess causality between uHP and DKD in East Asians.

Results

Baseline characteristic of the study participants

Table 1 summarises the baseline characteristics of participants, subjected to GWAS and HP structural variants (HP1/HP2) genotyping stratified by ethnicity. Considerable differences in median or mean values for BMI, HDL-C, eGFR and uACR were observed between ethnic groups. Malays had a higher proportion of female and DKD progressors (rapid decline in eGFR) as compared to Chinese. However, the distribution of HP genotype, median uHP and plasma haptoglobin (pHP) was comparable between Chinese and Malay.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical and biochemical characteristic of subjects stratified by ethnicity.

| Total (n = 327) | Chinese (n = 250) | Malay (n = 77) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| uHaptoglobin (ng/ml) | 203 (14–1828) | 157 (20–1442) | 365 (10–2790) | 0.229 |

| pHaptoglobin (µg/ml) | 1077 (766–1511) | 1074 (732–1487) | 1132 (893–1600) | 0.131 |

| Entry Age (years) | 56.9 ± 12.2 | 57.4 ± 12.5 | 55.2 ± 11.1 | 0.173 |

| Gender (Female, %) | 150(45.9) | 104 (41.6) | 46 (59.7) | 0.005 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 26.8 ± 4.9 | 26.1 ± 4.3 | 28.8 ± 6.0 | <0.001 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 66.3 ± 21.1 | 64.9 ± 19.5 | 70.8 ± 25.3 | 0.065 |

| Diabetes Duration (years) | 10.6 ± 8.0 | 10.6 ± 8.0 | 10.5 ± 8.1 | 0.925 |

| Lipids profile | ||||

| TC (mM) | 4.70 ± 1.02 | 4.69 ± 0.96 | 4.75 ± 1.18 | 0.663 |

| HDL-C (mM) | 1.27 ± 0.37 | 1.30 ± 0.37 | 1.18 ± 0.34 | 0.016 |

| LDL-C (mM) | 2.83 ± 0.77 | 2.82 ± 0.73 | 2.89 ± 0.90 | 0.483 |

| Triglycerides (mM) | 1.48 (1.08–2.08) | 1.48 (1.07–2.09) | 1.47 (1.17–2.08) | 0.586 |

| Blood pressure (mmHg) | ||||

| SBP | 135 ± 20 | 135 ± 20 | 134 ± 20 | 0.620 |

| DBP | 78 ± 11 | 78 ± 10 | 77 ± 12 | 0.718 |

| Renal function (baseline) | ||||

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 80.6 ± 30.9 | 82.5 ± 29.9 | 74.5 ± 33.5 | 0.048 |

| uACR (µg/mg) | 49 (16–150) | 38 (13–131) | 107 (29–262) | <0.001 |

| Trajectory of eGFR | ||||

| Duration of follow-up (year) | 5.5 (5.0–6.7) | 5.7 (5.0–7.0) | 5.2 (4.3–6.0) | 0.001 |

| ml/min per 1.73 m2/year | −1.0 (−6.2 to 0.5) | −0.9 (−4.9 to 0.6) | −3.3 (−7.7 to 0.2) | 0.015 |

| percentage change/year | −1.3 (−8.0 to 0.6) | −1.1 (−6.4 to 0.8) | −4.3 (−11.2 to 0.2) | 0.012 |

| No of progressors (n, %) | 123 (37.6) | 83 (33.2) | 40 (51.9) | 0.003 |

| Use of Medication (n, %) | ||||

| Insulin | 113 (34.6) | 80 (32.0) | 33 (42.9) | 0.080 |

| RAS antagonist | 226 (69.1) | 166 (66.4) | 60 (77.9) | 0.056 |

| HP genotype | 0.447 | |||

| HP 1–1 | 35 (10.7) | 28 (11.2) | 7 (9.1) | |

| HP 2–1 | 130 (39.8) | 103 (41.2) | 27 (35.1) | |

| HP 2–2 | 162 (49.5) | 119 (47.6) | 43 (55.8) | |

Abbreviations: uHP, urine haptoglobin; pHP, plasma haptoglobin; BMI, body mass index; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; HDL-C, HDL cholesterol; LDL-C, LDL cholesterol; uACR, urine albumin creatinine ratio; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; RAS, renin-angiotensin system. Data are described as mean +/- SD or median (interquartile range) for skewed variables or proportion of participants (%) where appropriate. Bold values represent statistically significant data between ethnic groups.

Genetic determinant of haptoglobin levels

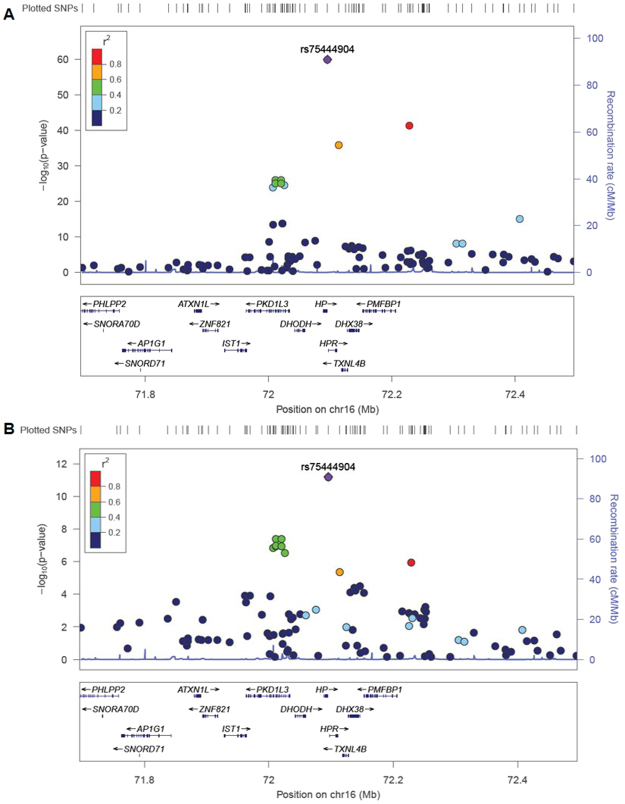

QQ-plots for urine and plasma z-HP levels in the discovery (DN Chinese) and validation (DN Malay and SMART2D Chinese) datasets are shown in Supplementary Figs S3 and S4. The genomic inflation factor (λ) at the discovery and validation stages of the study was observed to be minimal (λ between 0.990–1.027), indicating that quality control (QC) procedures had effectively excluded aberrant samples and SNPs, and analysis methods had effectively controlled for possible population stratification issues. A strong genotyped signal beyond the genome-wide significance threshold was observed at chromosome 16, corresponding to the HP gene locus for urine z-HP in the discovery stage (P = 1.07 × 10−16, Table 2). The top SNP for urine z-HP association, kgp16506790 (rs75444904) was highly polymorphic in EA populations but monomorphic in most other reference populations (1000 Genomes reference) and explained approximately 25.5% of phenotypic variance of uHP levels in our Chinese samples. The association of rs75444904 with urine z-HP levels was replicated in the Malay dataset (P = 1.80 × 10−3) and independent Chinese samples from SMART2D cohort (P = 3.98 × 10−41) (Fig. 1 and Table 2). Although rs75444904 was imputed in the SMART2D cohort, the SNP was observed with good imputation confidence score (info score = 0.86) and had comparable MAF (0.275). Repeating uHP association analyses at rs75444904 in discovery and validation stages using the mixed model association to further control for population substructure (GEMMA) or through the EIGENSTART method indicated similarly robust genome-wide associations (Supplementary Table S3). This same SNP also reached genome-wide significance level for plasma z-HP in the discovery Chinese samples (P = 2.08 × 10−10, Table 2), explaining approximately 14.7% of phenotypic variance of plasma HP levels in our Chinese samples. The identified rs75444904 associations with plasma z-HP levels also showed a similar trend in the Malay validation samples although this was not statistically significant (P = 0.087, Table 2).

Table 2.

SNP with genome-wide levels of associations for urine z-HP levels in the discovery stage of the study and their corresponding association levels in the validation datasets.

| SNP | Chr | Pos | TA | Discovery stage | Replication stage | Meta-analysis (N = 805) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DN Chinese (N = 236) | DN Malay (N = 57) | SMART2D Chinese (N = 512) | β (SE) | P | P_het | I2 | ||||||||||

| TAF | β (SE) | P | TAF | β (SE) | P | TAF | β (SE) | P | ||||||||

| urine z-HP | ||||||||||||||||

| rs75444904 | 16 | 72095650 | C | 0.307 | 0.732 (0.082) | 1.07 × 10−16 | 0.219 | 0.705 (0.214) | 1.80 × 10−3 | 0.275 | 0.807 (0.059) | 3.98 × 10−41 | 0.777 (0.047) | 1.21 × 10−60 | 0.717 | 0 |

| Plasma z-HP | ||||||||||||||||

| rs75444904 | 16 | 72095650 | C | 0.307 | 0.583 (0.088) | 2.08 × 10−10 | 0.219 | 0.438 (0.251) | 0.087 | NA | NA | NA | 0.567 (0.083) | 6.51 × 10−12 | 0.586 | 0 |

Data analysis was adjusted for age, sex and Principal Components (PC1 for Chinese and PC1–3 for Malay). Abbreviations: Chr, chromosome number; TA, test allele; TAF, test allele frequency, P_het: Cochran’s Q heterogeneity p-value, I2: heterogeneity index, NA: not available.

Figure 1.

Chromosomal plot of genome-wide signal at chromosome 16 for A) urine z-HP associations and B) plasma z-HP associations. Association p-values derived from meta-analysis of discovery stage and validation stage datasets. LD (r2) data of the SNPs are based on ASN panels of 1000 Genome Project database. Plots generated using LocusZoom (http://locuszoom.sph.umich.edu/).

In a pooled analysis of participants with both pHP and uHP measured, individuals with rs75444904 CC genotype had almost 10-fold increase in uHP compared to AA genotype (Supplementary Table S4). uHP levels were significantly higher in individuals with HP 1-1 genotype and HP 2-1 genotype as compared to HP 2-2 genotype, and HP 1-1 genotype compared to HP 2-1 genotype (HP 1-1 = 4292ng/ml, HP 2-1 = 511ng/ml, HP 2-2 = 41ng/ml, P < 0.0001) (Supplementary Table S4). In contrast, pHP levels were only significantly higher in individuals with HP 1-1 and HP 2-1 genotype when compared to HP 2-2 but not in HP 1-1 genotype as compared to HP 2-1 (Supplementary Table S4). In a sensitivity analysis, excluding patients with macroalbuminuria (uACR ≥ 300 µg/mg) and eGFR less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 at baseline did not materially change the significantly elevated level of uHP level in individuals with HP1 allele compared to HP2 allele (P < 0.0001, n = 244).

Linkage disequilibrium (LD) of rs75444904 and HP common polymorphism

HP structural variant (HP1 allele) and rs75444904 [C] allele were observed to be in LD in both the Chinese (r2 = 0.911) and Malay datasets (r2 = 0.536). Conditional probability analysis on rs75444904 and HP1 allele showed that individual associations with uHP were not completely abolished (HP 1; β = 0.264, P = 0.010 and rs75444904; β = 0.543, P = 8.22 × 10−7, Supplementary Table S5). Previous studies in European population suggested rs217181 as the best proxy for tagging HP allele (r2 = 0.44)29. Therefore, we looked at the association of rs217181 with haptoglobin levels in our study cohort. In combined analysis, the association of rs217181 with plasma (β = 0.384, P = 4.24 × 10−6) and urine (β = 0.621, P = 1.45 × 10−36) haptoglobin levels reached genome wide level but was weaker compared to rs75444094 (Supplementary Table S6). Moreover, conditioning on rs75444904 genotypes attenuated the genome wide association of rs217181 and urine HP (P = 0.003) while the association remained robustly significant at rs75444904 (P = 8.64 × 10−23) (Supplementary Table S7).

Association of genotype and renal functions

After meta-analysis, rs75444904 SNP was significantly associated with a 77% increased risk for DKD progression after adjustment for age, sex, principle components, BMI, HbA1c, diabetes duration, systolic blood pressure, HDL-C, LDL-C, TG, eGFR, uACR and intake of insulin and RAS antagonist (OR = 1.77, 95% CI 1.32–2.23, p = 0.014) (Table 3, Supplementary Table S8). We also observed significant association of HP1 allele with increased risk for DKD progression (OR = 1.91, 95% CI 1.45–2.37, p = 0.006) (Table 3, Supplementary Table S8).

Table 3.

Association between rs75444904 and HP1 allele with DKD progression under additive model in East Asians.

| Progressors | Non-Progressor | Meta-analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | P_het | |||

| rs75444904 (AA/CA/CC) | 45/53/10 | 107/59/19 | 1.77 (1.32–2.23) | 0.014 | 0.425 |

| HP1 (1–1/2–1/2–2) | 15/59/49 | 20/71/113 | 1.91 (1.45–2.37) | 0.006 | 0.084 |

Data represents odd ratios (OR) and 95% CI adjusted for age, gender, HbA1c, diabetes duration, Systolic BP, lipids (natural log-transformed HDL-C, LDL-C and TG), eGFR, uACR (natural log-transformed) and RAS antagonist and insulin usage. Abbreviations: P_het: Cochran’s Q heterogeneity p-value. Bold values represent statistically significant data.

We further examined the association of rs75444904 with ESRD cross-sectionally in independent samples from our Diabetic Nephropathy (DN), SMART2D cohorts30 and T2D samples from Chinese cohort from China. After meta-analysis, we observed modest but significant association of rs75444904 with 22% increased risk for ESRD (410 cases vs 1308 control; OR = 1.22, 95% CI 1.01–1.47, P = 0.036) after adjusting for age, gender and principle components (except in the China dataset where GWAS data was not available) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Association of rs75444904 with ESRD in independent samples in East Asians.

| DN | SMART2D | CH | Meta-Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | Malay | Chinese | Malay | Chinese | ||

| N | 881 | 224 | 391 | 105 | 117 | 1718 |

| rs75444904 (AA/CA/CC) | 441/346/94 | 132/78/14 | 210/153/28 | 59/30/16 | 59/42/16 | 901/649/168 |

| MAF (C allele) | 0.302 | 0.237 | 0.267 | 0.295 | 0.316 | 0.287 |

| ESRD (Case/Control) | 194/687 | 102/122 | 18/373 | 14/91 | 82/35 | 410/1308 |

| OR | 1.132 | 1.402 | 1.354 | 1.214 | 1.213 | 1.22 |

| P | 0.304 | 0.134 | 0.412 | 0.662 | 0.523 | 0.036 |

| 95% CI | 1.01–1.47 | |||||

| P_het | 0.898 | |||||

Abbreviations: MAF, minor allele frequency; P_het, Cochran’s Q heterogeneity p-value. ESRD case is defined as eGFR < 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 and control is defined as T2D patients with diabetes duration of more than 10 years and eGFR > 15 mL/min/1.73 m2. Data not adjusted for PCs in CH dataset without GWAS data.

Mendelian Randomisation analysis

Given the robust association with uHP level and significant association with renal decline, we used rs75444904 as an instrumental variable for uHP for MR analysis. We found a significant association between genetically increased uHP and risk for DKD progression in our study. After meta-analysis of all datasets, 1 SD increase in uHP was associated with DKD progression (OR = 2.09 95% CI 1.50–2.67, P = 0.007) (Table 5) after adjustment for DKD traditional risk factors. Given the LD between rs75444904, HP structural variant and rs217181, we found similarly significant observations using HP1 or rs217181 as instrumental variable (Table 5).

Table 5.

Mendelian Randomisation analysis on association of uHP with DKD progression in T2D patients.

| Instrumental variable | Linkage disequilibrium (r2) with HP 1 (Chinese/Malay) | Effect/Other allele | EAF (%) (Chinese/Malay) | beta (SE) of urine Haptoglobin level per allele | P | OR (95% CI) for DKD progression per allele | P | MR estimate of DKD progression per 1 SD increase in uHP | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HP 1 | — | HP1/HP2 | 0.291/0.267 | 0.727 (0.046) | 1.42 × 10−55 | 1.91 (1.45–2.37) | 0.006 | 2.42 (1.80–3.06) | 0.003 |

| rs75444904 | 0.91/0.54 | C/A | 0.285/0.219 | 0.777 (0.047) | 1.21 × 10−60 | 1.77 (1.32–2.27) | 0.014 | 2.09 (1.50–2.67) | 0.007 |

| rs217181 | 0.84/0.45 | T/C | 0.324/0.272 | 0.621 (0.048) | 1.45 × 10−36 | 1.83 (1.37–2.29) | 0.010 | 2.64 (1.90–3.38) | 0.005 |

Data were adjusted for age, gender, HbA1c, diabetes duration, Systolic BP, lipids (natural log-transformed HDL-C, LDL-C and TG), eGFR, uACR (natural log-transformed) and usage of medications.

HP1 allele has been associated with reduced level of LDL cholesterol29. Mediation analysis31 for DKD progression in our study, adjusted for traditional risk factors, suggested full mediation by uHP, and in contrast, lack for mediation by LDL-C (Supplementary Table S10).

Discussion

In this study, we identified a robust GWAS signal rs75444904 (upstream of HP gene) as an East Asian specific variant influencing uHP level. Genetic disposition to higher uHP level in T2D patients was associated with higher risk for DKD progression independent of traditional risk factors including hypertension, hyperglycemia, diabetes duration, dyslipidemia as well as baseline renal function and usages of medications. Individuals with rs75444904 risk variant allele were also at 22% increased risk for progression to ESRD. We further used a MR approach to provide genetic evidence to support the potential causal relationship of increased uHP level in DKD progression in East Asians. These are novel observations as no other studies have reported genetic markers for uHP and used MR approach to assess the casual association in East Asian populations.

In the current analysis, elevated uHP levels were observed in T2D individuals with rs75444904 [C] allele and HP1 allele as compared to rs75444904 [A] and HP2 allele respectively. Interestingly, rs75444904 is monomorphic in Europeans (1000 Genome database) but has minor allele frequency between 20–30% in the Chinese and Malays. Conditional probability analysis did not completely abolish the individual associations of rs75444904 [C] allele and HP1 allele with uHP. Moreover, the association of rs75444904 with uHP was stronger compared to HP 1 allele (HP 1; β = 0.264, P = 0.010 and rs75444904; β = 0.543, P = 8.22 × 10−7). Therefore, we cannot rule out that rs75444904 SNP may have some independent effect or may also tag to another causal mutation. A recent large scale study aimed to identify tagging SNPs for HP structural variant in Europeans found that HP allele is correlated with rs217181 (r2 = 0.44)29. In East Asians, we found that rs75444904 and HP allele is highly correlated (Chinese, r2 = 0.911; Malay, r2 = 0.536). More importantly, we observed that the association of rs217181 with uHP level is weaker compared to rs75444904 and driven mainly by rs75444904 at this locus. This suggests that rs75444904 may be a better surrogate as genetic marker for uHP level in T2D in East Asians.

Findings from this study provides genetic support to previous observational studies by us and others demonstrating association of uHP with decline in renal function in T2D patients8–10. For MR analysis, a strong link between the genetic variant used as the instrumental variable and the exposure (uHP level), as demonstrated in our study, is essential. Recent reports have shown that HP structural variant is associated with reduced LDL cholesterol levels29. However, the likelihood of horizontal pleiotropy is minimal in our study for 1) the SNP or copy number variant explains a significantly high proportion of phenotypic variability (20–30% of uHP variance); 2) the uHP is instrumented in MR by cis-acting variant in the vicinity of the encoding gene32; 3) the association of genetic instrument with the disease outcome (DKD progression) is mediated solely through the biomarker of interest (urine haptoglobin) and not LDL-C and 4) associations between the genetic instrumental variable and DKD progression remained significant after adjustments for traditional risk factors and measures of population structure (principle components). Nevertheless, it remains possible that pleotropic effects of the genetic instrument variable used in our study may still exist with other unknown and unmeasured factors and these may confound study results.

Most of the studies on evaluating the biological role of HP1 allele are in relation to its enhanced anti-oxidative function as compared to HP2 allele in cardiovascular disease33. Haptoglobin is also an angiogenic factor and is essential for functional role of endothelial cells in neovascular development34. Besides the liver, HP gene is also expressed in the kidney and inducible through cytokines such as interleukin-635. From our study, uHP level among HP2 individuals does not differ between subjects with impaired or preserved renal function, suggesting that increase in uHP level may probably be due to increase in-situ expression in renal tissues. Data from mouse models subjected to acute kidney injury with multiple agents revealed relatively greater and sustained increase in renal (proximal tubules) expression of HP as compared to hepatic HP expression36. While the focus of this study was to assess the causal relationship between uHP and renal function, undeniably, further mechanistic data, as well as evidence from prospective studies, are required to confirm the role of the rs75444904 in the pathophysiology of renal complications of diabetes. In line with this, recent studies have highlighted HP1 allele as a risk factor for white matter hyperintensities and stroke37,38. Compared to uHP, the genetic determinants of serum haptoglobin level has been previously reported with rs2000999, rs5472 variants in HP gene and HP structural variants affecting the serum haptoglobin level17,19,20. In our study, we also found that rs75444904 and HP1 allele are robustly associated with pHP level although the association was weaker as compared to that with uHP level. However, pHP level was not associated with DKD progression in T2D patients after adjusting for traditional risk factors. Serum haptoglobin level are modulated by various clinical disease such as inflammation, haemolysis and liver disease39,40 and thus may less likely be an ideal reflection of patients’ renal conditions. Therefore, our findings demonstrate the added advantages of using urine samples for identifying novel biomarker in pathologies of DKD.

Our study represents the first comprehensive search for genetic determinant of uHP levels using GWAS in East Asians with T2D. Additionally we compared both pHP and uHP level in the same individual to demonstrate the utility of uHP as a better predictor and causal factor for DKD progression. Moreover, DKD progression was defined by trajectory slope ensuring gradual decrease in T2D patients with a median follow-up of 5.5 years and more than 3 eGFR readings. However, we acknowledge limitations of our study. To efficiently analyses DKD progression biomarkers, we only included T2D patients with at least 3 eGFR readings to generate a trajectory slope to classify them as rapid progressors and non-progressors which resulted in a relatively small sample size for GWAS (n = 327). Despite the small sample size, robust signal was observed for association of common variants and uHP level. Our success in part could be due to 1) “enriched” phenotype study design used in the initial GWAS which may have increased the power of our study; 2) genetic variant identified (rs75444904) is in close proximity or within the gene coding the protein (HP copy number variant), suggesting fewer biological steps between genetic variant and protein synthesis and a larger signal to noise ratio41; 3) use of intermediate phenotype eGFR gradient as outcome; 4) relatively higher frequency of minor allele (MAF~0.33) among East Asians. While we validated the association of rs75444904 with ESRD cross-sectionally in larger independent East Asian samples, further large scale studies in independent East Asian population with long term follow-up data would be necessary to firmly confirm or dismiss the association at this locus.

In conclusion, we have identified East Asian specific common variant rs75444904 that influences uHP level and demonstrated that a genetic predisposition to increase uHP level was associated with increased risk of decline in renal function in T2D. These findings provide evidence supportive of a potential causal link between uHP and renal function in T2D. If further validated in independent cohorts, therapy targeting uHP may likely be effective in delaying DKD progression in East Asians.

Materials and Methods

Study design and participants

Participants for this study were recruited in the diabetes centres in Singapore as described previously in our Diabetic Nephropathy (DN) cohort9. Briefly, the exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) age below 21 years; 2) pregnancy; 3) manifest infectious disease, active cancer, and autoimmune diseases; or 4) type 1 diabetes (requirement for continuous insulin therapy within 1 year after diabetes onset or acute presentation with ketoacidosis). 327 participants (250 Chinese and 77 Malays) from the DN study were subjected to genome wide association study. Top index SNP was further validated in 512 independent Chinese samples from previously reported SMART2D cohort30.

Definition of Outcomes

Primary renal outcome in the prospective analysis was DKD progression as described previously in our DN study using the same cohort9. DKD progression was defined as decline in eGFR gradient > 3 mL/min/1.73 m2 per year by trajectory slope3. Non-progressors were defined as eGFR changes ± 2 mL/min/1.73 m2 per year and at least 5 years follow-up. In total, 327 T2D participants comprised of 83 progressors and 167 non-progressors in Chinese subjects and 40 progressors and 37 non-progressors in Malay subjects.

For secondary cross-sectional analysis on association of our candidate SNP with renal disease traits, ESRD patients at baseline were defined as T2D patients with eGFR < 15 mL/min per 1.73 m2 while the controls for ESRD were T2D patients with diabetes duration for more than 10 years with eGFR > 15 mL/min per 1.73 m2. The information on the DN and SMART2D cohorts used for secondary analysis has been detailed previously30. The Chinese samples consist of 82 T2D-related ESRD cases and 34 T2D-related controls, collected during the period from October 2015 to December 2016 from 7 different hospitals in China (Supplementary Methods). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. This study complies with Helsinki Declaration and has been approved by the Singapore National Health Group (NHG) domain specific ethical review board.

Clinical and biochemical measurement

Total urine and plasma haptoglobin was measured using a sandwich enzyme immunoassay (R&D Systems Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Urinary albumin: creatinine ratio (ACR) was determined by urinary creatinine measured by the enzymatic method on a cobas c system (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) and albumin measured by a solid-phase competitive chemiluminescent enzymatic immunoassay with a lower detection limit of 2.5 lg/mL (Immulite, DPC, Gwynedd,UK). The baseline and follow- up eGFR was calculated based on the widely used Modified Diet in Renal Disease equation in patients with diabetes.

Genotyping

Haptoglobin structural (copy number) variant

PCR followed by gel electrophoresis was used to genotype for the HP structural variant (HP1/HP2) in 327 subjects from DN cohort as reported previously42. This procedure produces unique PCR products for each HP alleles. We performed duplicates for selected samples to demonstrate 100% concordance.

Genome-wide association study

Genome-wide genotyping was performed for 2,664 samples from the DN cohort using the Illumina HumanOmniZhonghua Bead Chip. Quality control (QC) procedures of samples and SNPs are detailed in Supplementary Table 1. Briefly, samples with call-rate < 95.0% (N = 4), extremes in heterozygozity (>3 SD from mean, N = 55) and known duplicates (N = 12) were excluded from analyses. Identity-by-state measures were performed by pair-wise comparison of samples to detect 1st degree related samples (Supplementary Table 1) and one sample from each relationship was excluded from further analysis (N = 96). Principle component analysis (PCA) together with 1000 Genomes Projects reference populations was performed to identify possible outliers from reported ethnicity and 127 samples were excluded (Supplementary Figs 1 and 2). After GWAS sample QC procedures, 236 Chinese and 57 Malays with uHP and pHP information were available for subsequent statistical analysis (Supplementary Table S1).

For SNP QC, sex-linked and mitochondrial SNPs were removed, together with gross HWE outliers (p-value < 1 × 10-4) (Supplementary Table S2). SNPs that were monomorphic or with a MAF < 1.0% and SNPs with low call-rates (<95.0%) were excluded (Supplementary Table S2). Alleles for all SNPs were coded to the forward strand and mapped to HG19.

Statistical analysis

GWAS discovery stage urine and plasma Haptoglobin associations

To identify SNPs that influence urine and plasma HP levels, we first performed a discovery stage analysis using data from DN Chinese subjects. Raw urine and plasma HP levels were normalized by rank-based inverse normalization (z-scores). Linear regression analyses between SNPs and urine z-HP and plasma z-HP levels were performed using PLINK v1.9 in an additive model and adjusted for age, sex and population stratification (PC1). Genomic inflation factor (λ) of association results was used to evaluate levels of inflation of study results. SNPs with association p-values that reached genome-wide levels (p-value < 5 × 10−8) were followed up in the validation stage of the study. For lead SNPs with genome-wide association identified in our study, we estimated the proportion of the respective urine and plasma HP variance explained by evaluating adjusted R2 values of regression models before and after inclusion of the lead SNP into the model.

GWAS validation stage plasma and urinary Haptoglobin associations

uHP and pHP data from DN Malay subjects were utilized in the validation stage of the study. In addition, the uHP were measured in additional independent 512 Chinese samples (SMART2D cohort) with GWAS data from our previous study30. As in discovery samples, raw values were normalized as indicated above. Genome-wide linear regression analyses between SNPs and z-HP and urine z-HP were performed separately in the Malay and Chinese datasets and adjusted for age, sex and population stratification (PC1-3 for Malay and PC1 for Chinese). All genome-wide SNPs were replicated, in silico, in the validation datasets. Subsequently, association summary statistics from discovery and validation stages were combined using the inverse variance-weighted meta-analysis, assuming a fixed effects model to derive overall association values. Cochran’s Q p-value (<0.05) and/or I2 (>40.0%) were used to evaluate for heterogeneity during meta-analysis. GWAS association analyses in the discovery and replication stages were also repeated using Genome-wide Efficient Mixed Model Association (GEMMA) that accounts for population stratification and sample structure during analysis43 and through the EIGENSTRAT method that corrects for stratification using continuous axes of variation44.

Association analysis with renal functions

Continuous variables with normal distribution were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), while non-normally distributed variables were presented as medians (25th-75th percentile). Categorical data were expressed as proportions. Comparison between ethnic groups or genotypes was performed by independent sample t-test for normally distributed variables or the Mann-Whitney U test or Kruskal-Wallis test for non-normally distributed variables (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S4). Comparisons of categorical variables were performed with chi-squared (χ2) test.

Binary logistic regression models were used to evaluate the association of SNP or HP allele (additive model) and DKD progression with the adjustment for age, gender, BMI, principle components, HbA1c, diabetes duration, systolic blood pressure, triglycerides, HDL-C, LDL-C, baseline eGFR and uACR and intake of RAS antagonist and insulin. Natural log transformed values for lipids and uACR was used for analysis (Table 3 and Supplementary Table S8). Association analysis of top SNP and ESRD were adjusted for age, sex, and PC components (PC1 for Chinese and PC1-3 for Malay, PCs not used for China samples without GWAS data) (Table 4). Statistical analyses were performed separately for the Chinese and Malay samples and a combined odd ratio was obtained using inverse-variance-weighted, fixed-effects meta-analysis (all P for heterogeneity > 0.05).

In the MR analysis, the causal estimate OR was derived using exp(β2/β1) as described by Burgess et al.45 where β1 = regression coefficient of IV and z transformed urine haptoglobin and β2 = regression coefficient of IV and DKD progression. The combined beta regression coefficients for association between instrumental variable (SNP and HP allele) and 1) uHP and 2) DKD progression was obtained from pool analysis of Chinese and Malay samples using the inverse variance-weighted meta-analysis, assuming a fixed effects model. A two-sided P values of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analysis were performed using SPSS version 22 and R software (version 3.3.2).

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the research team members from Clinical Research Unit and clinical doctors from diabetes centre at Khoo Teck Puat Hospital, Singapore for assistance with participant recruitment and data input for the DN and SMART2D and follow-up study. This study was supported by Alexandra Health Enabling Grant (AHEG1504) and Small Innovation Grants (AHPL SIG I/13031 & STAR17109).

Author Contributions

R.L.G., R.D., L.J.J. and L.S.C. designed the study. R.L.G. acquired and analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. R.D. preformed GWAS and analyzed the data. S.L. and Y.M. acquired data. L.W. performed GWAS analysis. All authors revised the manuscript and approved the final version.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Resham Lal Gurung and Rajkumar Dorajoo contributed equally to this work.

Change history

9/7/2018

A correction to this article has been published and is linked from the HTML and PDF versions of this paper. The error has not been fixed in the paper.

Contributor Information

Jian-Jun Liu, Email: liuj3@gis.a-star.edu.sg.

Su Chi Lim, Email: lim.su.chi@ktph.com.sg.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-23407-1.

References

- 1.Wu AY, et al. An alarmingly high prevalence of diabetic nephropathy in Asian type 2 diabetic patients: the MicroAlbuminuria Prevalence (MAP) Study. Diabetologia. 2005;48:17–26. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1599-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loh PT, Toh MP, Molina JA, Vathsala A. Ethnic disparity in prevalence of diabetic kidney disease in an Asian primary healthcare cluster. Nephrology (Carlton) 2015;20:216–223. doi: 10.1111/nep.12379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krolewski AS, Skupien J, Rossing P, Warram JH. Fast renal decline to end-stage renal disease: an unrecognized feature of nephropathy in diabetes. Kidney Int. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.10.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allison AC, Rees WA. The binding of haemoglobin by plasma proteins (haptoglobins); its bearing on the renal threshold for haemoglobin and the aetiology of haemoglobinuria. Br Med J. 1957;2:1137–1143. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5054.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Langlois MR, Delanghe JR. Biological and clinical significance of haptoglobin polymorphism in humans. Clin Chem. 1996;42:1589–1600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakhoul, F. M. et al. Pharmacogenomic effect of vitamin E on kidney structure and function in transgenic mice with the haptoglobin 2-2 genotype and diabetes mellitus. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 296, F830–838, 10.1152/ajprenal.90655.2008 90655.2008 [pii] (2009). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Kristiansen M, et al. Identification of the haemoglobin scavenger receptor. Nature. 2001;409:198–201. doi: 10.1038/35051594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhensdadia NM, et al. Urine haptoglobin levels predict early renal functional decline in patients with type 2 diabetes. Kidney Int. 2013;83:1136–1143. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu JJ, Liu S, Wong MD, Gurung RL, Lim SC. Urinary Haptoglobin Predicts Rapid Renal Function Decline in Asians With Type 2 Diabetes and Early Kidney Disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101:3794–3802. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang JK, et al. Urine Proteome Specific for Eye Damage Can Predict Kidney Damage in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: A Case-Control and a 5.3-Year Prospective Cohort Study. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:253–260. doi: 10.2337/dc16-1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hallan SI, Orth SR. Smoking is a risk factor in the progression to kidney failure. Kidney Int. 2011;80:516–523. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jafar TH, Jin A, Koh WP, Yuan JM, Chow KY. Physical activity and risk of end-stage kidney disease in the Singapore Chinese Health Study. Nephrology (Carlton) 2015;20:61–67. doi: 10.1111/nep.12355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith GD, Ebrahim S. ‘Mendelian randomization’: can genetic epidemiology contribute to understanding environmental determinants of disease? Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32:1–22. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyg070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawlor DA, Harbord RM, Sterne JA, Timpson N, Davey Smith G. Mendelian randomization: using genes as instruments for making causal inferences in epidemiology. Stat Med. 2008;27:1133–1163. doi: 10.1002/sim.3034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levy AP, et al. Haptoglobin: basic and clinical aspects. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;12:293–304. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melamed-Frank M, et al. Structure-function analysis of the antioxidant properties of haptoglobin. Blood. 2001;98:3693–3698. doi: 10.1182/blood.V98.13.3693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park KU, Song J, Kim JQ. Haptoglobin genotypic distribution (including Hp0 allele) and associated serum haptoglobin concentrations in Koreans. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57:1094–1095. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2004.017582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dalan R, et al. The haptoglobin 2-2 genotype is associated with inflammation and carotid artery intima-media thickness. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2016;13:373–376. doi: 10.1177/1479164116645247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soejima M, et al. Genetic factors associated with serum haptoglobin level in a Japanese population. Clin Chim Acta. 2014;433:54–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2014.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Froguel P, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies rs2000999 as a strong genetic determinant of circulating haptoglobin levels. PLoS One 7, e32327. 2012 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shahabi P, Siest G, Herbeth B, Ndiaye NC, Visvikis-Siest S. Clinical necessity of partitioning of human plasma haptoglobin reference intervals by recently-discovered rs2000999. Clin Chim Acta. 2012;413:1618–1624. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2012.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wobeto VP, Garcia PM, Zaccariotto TR, Sonati Mde F. Haptoglobin polymorphism and diabetic nephropathy in Brazilian diabetic patients. Ann Hum Biol. 2009;36:437–441. doi: 10.1080/03014460902960263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Conway BR, Savage DA, Brady HR, Maxwell AP. Association between haptoglobin gene variants and diabetic nephropathy: haptoglobin polymorphism in nephropathy susceptibility. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2007;105:e75–79. doi: 10.1159/000098563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bessa SS, Hamdy SM, Ali EM. Haptoglobin gene polymorphism in type 2 diabetic patients with and without nephropathy: An Egyptian study. Eur J Intern Med. 2007;18:489–495. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2007.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koda Y, et al. Haptoglobin genotype and diabetic microangiopathies in Japanese diabetic patients. Diabetologia. 2002;45:1039–1040. doi: 10.1007/s00125-002-0834-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakhoul FM, et al. Haptoglobin phenotype and diabetic nephropathy. Diabetologia. 2001;44:602–604. doi: 10.1007/s001250051666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moczulski DK, Rogus JJ, Krolewski AS. Comment to: F. M. Nakhoul et al. (2001). Haptoglobin phenotype and diabetes. Diabetologia 44: 602-604. Diabetologia. 2001;44:2237–2238. doi: 10.1007/s001250100035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McMahon GM, Waikar SS. Biomarkers in nephrology: Core Curriculum 2013. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62:165–178. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boettger LM, et al. Recurring exon deletions in the HP (haptoglobin) gene contribute to lower blood cholesterol levels. Nat Genet. 2016;48:359–366. doi: 10.1038/ng.3510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lim SC, et al. Genetic variants in the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) gene were associated with circulating soluble RAGE level but not with renal function among Asians with type 2 diabetes: a genome-wide association study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016 doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfw263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holmes MV, Ala-Korpela M, Smith GD. Mendelian randomization in cardiometabolic disease: challenges in evaluating causality. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2017;14:577–590. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2017.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Costacou T, Levy AP. Haptoglobin genotype and its role in diabetic cardiovascular disease. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2012;5:423–435. doi: 10.1007/s12265-012-9361-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cid MC, et al. Identification of haptoglobin as an angiogenic factor in sera from patients with systemic vasculitis. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:977–985. doi: 10.1172/JCI116319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sadrzadeh SM, Bozorgmehr J. Haptoglobin phenotypes in health and disorders. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121(Suppl):S97–104. doi: 10.1309/8GLX5798Y5XHQ0VW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zager RA, Vijayan A, Johnson AC. Proximal tubule haptoglobin gene activation is an integral component of the acute kidney injury “stress response”. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;303:F139–148. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00168.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Costacou T, Secrest AM, Ferrell RE, Orchard TJ. Haptoglobin genotype and cerebrovascular disease incidence in type 1 diabetes. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2014;11:335–342. doi: 10.1177/1479164114539713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Staals J, et al. Haptoglobin polymorphism and lacunar stroke. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2008;5:153–158. doi: 10.2174/156720208785425675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gabay C, Kushner I. Acute-phase proteins and other systemic responses to inflammation. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:448–454. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902113400607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carter K, Worwood M. Haptoglobin: a review of the major allele frequencies worldwide and their association with diseases. Int J Lab Hematol. 2007;29:92–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-553X.2007.00898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Swerdlow DI, et al. Selecting instruments for Mendelian randomization in the wake of genome-wide association studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45:1600–1616. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koch W, et al. Genotyping of the common haptoglobin Hp 1/2 polymorphism based on PCR. Clin Chem. 2002;48:1377–1382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou X, Stephens M. Genome-wide efficient mixed-model analysis for association studies. Nat Genet. 2012;44:821–824. doi: 10.1038/ng.2310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Price AL, et al. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2006;38:904–909. doi: 10.1038/ng1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Burgess S, Small DS, Thompson SG. A review of instrumental variable estimators for Mendelian randomization. Stat Methods Med Res. 2015 doi: 10.1177/0962280215597579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.