Abstract

Background: Vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) is characterized by vaginal/vulvar dryness, irritation, dyspareunia, or dysuria. The objective of this study was to examine the efficacy and safety of a very low-dose estradiol vaginal cream (0.003%) applied twice per week in postmenopausal women with VVA-related vaginal dryness.

Materials and Methods: In this phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study, postmenopausal women with moderate–severe vaginal dryness as the most bothersome VVA symptom were randomized (1:1) to estradiol cream 0.003% (15 μg estradiol; 0.5 g cream) or placebo (0.5 g cream). Treatments were applied vaginally once daily for 2 weeks followed by two applications/week for 10 weeks. Coprimary outcomes were changes in severity of vaginal dryness, percentage of vaginal superficial and parabasal cells, and vaginal pH at final assessment. Additional outcomes comprised changes in severity of other VVA signs and symptoms. Adverse events (AEs) were assessed.

Results: Of the 576 randomized participants, most were white and had an average age of 59 years. At final assessment, estradiol reduced vaginal dryness severity, decreased vaginal pH, increased superficial cell percentage, and decreased parabasal cell percentage versus placebo (p ≤ 0.05, all). Estradiol also reduced vaginal dryness severity at Weeks 4–12 and dyspareunia at Week 8 versus placebo (p ≤ 0.05, all). Improvements in vaginal/vulvar irritation/itching severity and dysuria were similar between estradiol and placebo. Estradiol had comparable rates of treatment-emergent AEs to placebo. No deaths occurred.

Conclusions: Very low-dose estradiol vaginal cream (0.003%) dosed twice weekly is an effective and well-tolerated treatment for VVA symptoms and dryness associated with menopause.

Keywords: : vaginal estrogen, genitourinary syndrome of menopause, vulvovaginal atrophy

Introduction

Vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) is a chronic condition associated with reduced estrogen levels that occurs after the onset of menopause and is characterized by thinning of the vaginal and lower genitourinary epithelial lining, loss of vaginal elasticity, and increased vaginal pH.1–3 Symptoms include vaginal dryness, irritation, itching, burning, dyspareunia, and dysuria.1,2,4 In the large U.S. REVIVE survey of postmenopausal women, the most commonly reported VVA symptom was vaginal dryness (55%) followed by dyspareunia (44%) and vaginal irritation (37%).3 Lower urinary tract symptoms can also occur after menopause onset in addition to these vulvovaginal symptoms, which led to the 2014 proposal to replace VVA with the more inclusive term genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM).1 For the purposes of this article, the term VVA will be utilized to avoid inconsistencies in terminology as U.S. prescribing inserts of treatments discussed herein commonly refer to vulvar and vaginal atrophy rather than GSM.

While the prevalence of postmenopausal women experiencing VVA is over 50%,2 only 56% of postmenopausal participants with vulvovaginal symptoms in the REVIVE survey reported a discussion of their problem with a healthcare provider,3 demonstrating that these symptoms are typically underdiagnosed and undertreated. The frequency of vasomotor symptoms such as hot flashes, flushes, and night sweats declines over time without treatment, but vulvovaginal symptoms are chronic and progressive.5 Nonhormonal treatments such as moisturizers and lubricants can relieve mild symptoms, but fail to reverse many atrophic signs and have a brief window of effectiveness (<24 hours per use).2 The 2017 position statement from the North American Menopause Society (NAMS) recommends that estrogen for vulvovaginal symptoms be individualized, offering the most appropriate dose, regimen, duration of use, and route of administration, maximizing benefit and minimizing risk.5 This approach is consistent with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidance on estrogen treatment for menopause symptoms that recommends using appropriately low vaginal doses.6 Topical, localized estrogen treatments using delivery modalities such as vaginal tablets, rings, or creams reduce systemic estrogen exposure.2,7 Estradiol vaginal cream 0.01% (Estrace [Allergan USA, Inc., Irvine, CA], 0.1 mg estradiol/g) is an FDA-approved topical treatment for postmenopausal VVA.8 The objective of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a very low-dose estradiol vaginal cream (0.003% estradiol; 15 μg estradiol in 0.5 g cream) compared with placebo vaginal cream (consisting of the same ingredients as above with the exception of estradiol) dosed two times per week in postmenopausal women with VVA signs and vaginal dryness.

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted in compliance with the International Conference on Harmonization Harmonized Tripartite Guideline for GCP guidelines and in accordance with the ethical principles originating from the Declaration of Helsinki and the US FDA Code of Federal Regulations Title 21, parts 50, 56, and 312. The protocol was reviewed and approved by institutional review boards and all participants provided written informed consent.

Study design

This was a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study in postmenopausal women reporting vaginal dryness due to VVA as the most bothersome symptom. Following screening and baseline assessments, participants were randomized (1:1) to estradiol vaginal cream 0.003% (15 μg estradiol; 0.5 g of cream) or placebo cream (0.5 g of cream). During the 2-week initial treatment period, estradiol and placebo creams were applied vaginally every day for 2 weeks to rapidly maximize the vaginal response. Dosages for both treatments were then reduced to two maintenance applications per week for 10 weeks. After completing the 12-week trial, those participants who had an intact uterus at baseline were provided a progestin for 14 days; the type and dose of progestin were determined at the discretion of the investigator.

Participants

Postmenopausal women were recruited if they met at least one of the following criteria: (1) ≥35 years of age with bilateral oophorectomy and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels >40 mIU/mL; (2) ≥40 years of age following hysterectomy with FSH levels >40 mIU/mL; (3) ≥40 years of age with 12 months of amenorrhea; or (4) ≥40 years of age with 6 months of amenorrhea with FSH levels >40 mIU/mL. Participants were also required to self-identify as having vaginal dryness of moderate–severe intensity that was considered by the participant to be the most bothersome VVA symptom. Additional inclusion criteria included vaginal pH >5.0; ≤5% superficial cells on a vaginal cytology smear; normal clinical breast examination before enrollment; and documentation of a negative mammogram if >40 years of age.

Exclusion criteria for the study were as follows: porphyria; untreated hypertension; abnormal Pap smear at screening suggestive of at least a low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; or history of or suspected genetic component for thrombophlebitis or thromboembolic disorders. Participants could not be using vaginal (e.g., creams, gels, rings) or transdermal estrogen products within 4 weeks, hormonal intrauterine devices or oral estrogen products within 8 weeks, progestin implants or estrogen injections within 3 months, or estrogen pellet or progestin injections within 6 months of screening.

Assessments

Vaginal dryness severity was determined by a self-assessment 4-point scale: 0 = none (symptom is not present); 1 = mild (symptom is present but may be intermittent and does not interfere with activities/lifestyle); 2 = moderate (symptom is present and only occasionally interferes with activities/lifestyle); and 3 = severe (symptom is present and bothersome and activities/lifestyle have been modified because of it). Vaginal pH was measured via pH paper (values <4 or >7 were recorded as 4 or 7, respectively) at screening and Week 12; participants were asked to abstain from sexual intercourse for 48 hours before assessment. Vaginal cytology was assessed at screening and Week 12 to determine the percentage of superficial and parabasal cells. Vaginal and/or vulvar itching and dysuria were participant assessed on a 4-point scale (0 = none; 1 = mild; 2 = moderate; 3 = severe), and vaginal bleeding associated with sexual activity was classified as present, not present, or not applicable due to lack of sexual activity. Extent of vaginal atrophy, pallor, vaginal dryness, friability, and petechiae was determined by the investigator via visual examination using a four-point scale (0 = none; 1 = mild; 2 = moderate; 3 = severe). These assessments occurred at screening and Weeks 2, 4, 8, and 12.

Safety was evaluated throughout the study, including via adverse event (AE) reporting and vital signs at each visit and at baseline and Week 12 via clinical laboratory tests and physical and gynecological examinations.

Outcomes

The coprimary outcomes of this study were change from baseline to final assessment (defined as the last available postbaseline assessment) in self-assessed severity of vaginal dryness, vaginal cytology (percentage of vaginal superficial and parabasal cells), and vaginal pH. Secondary outcomes comprised change from baseline to Weeks 2, 4, 8, and 12 in severity of vaginal dryness, and change from baseline to Weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, and final assessment in severity of vaginal/vulvar itching, dysuria, dyspareunia, and the number of participants with sexual activity-related vaginal bleeding at each visit. Change from baseline to Week 12 and final assessment in vaginal atrophy, pallor, dryness, friability, and petechiae were scored and analyzed.

Statistical analyses

The safety population comprised participants who were randomized and took ≥1 dose of study drug. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics, AEs, vital signs, clinical laboratory values, and gynecological examination results in the safety population were summarized by treatment with descriptive statistics. The modified intention-to-treat (mITT) population consisted of any participants in the safety population who had ≥1 postbaseline efficacy assessment and met all specific inclusion criteria. Efficacy analyses were performed using the mITT population. For the primary outcomes, normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test in conjunction with normality figures/plots and homogeneity of variance was determined using Levene's test; significance was set at 0.05 for both. If the assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance were met, an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was utilized with treatment and site as fixed effects and baseline value as the covariate. If the assumptions were not met, a ranked ANCOVA9 was used using the same model as above. In this analysis, each primary efficacy and baseline covariate was ranked from smallest to largest separately. The estradiol vaginal cream was considered efficacious compared with placebo if all three coprimary efficacy variables provided p values <0.05. No adjustment for multiple comparisons was made for this study.

Secondary efficacy outcomes were assessed via ANCOVA or ranked ANCOVA using the same methods as described for the primary outcomes, with the exception of vaginal bleeding associated with sexual activity. This outcome was analyzed using the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test with pooled site as a stratification factor. Responses of “not applicable” (NA) to dyspareunia severity with or without (including NA) the presence of vaginal bleeding were excluded.

It was estimated that a total of 500 enrolled participants were required to allow for a final population of 478 participants. This sample size would provide at least 85% power to find a difference between the estradiol vaginal cream and placebo treatment with an overall α-level of 0.05. A greater number of participants were randomized as all screened and randomized participants were later required to have ≤5% superficial cells on vaginal smear, a vaginal pH >5, and moderate–severe vaginal dryness as the most bothersome VVA symptom. All tests were two sided and significance was set at 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS (v 9.3).

Results

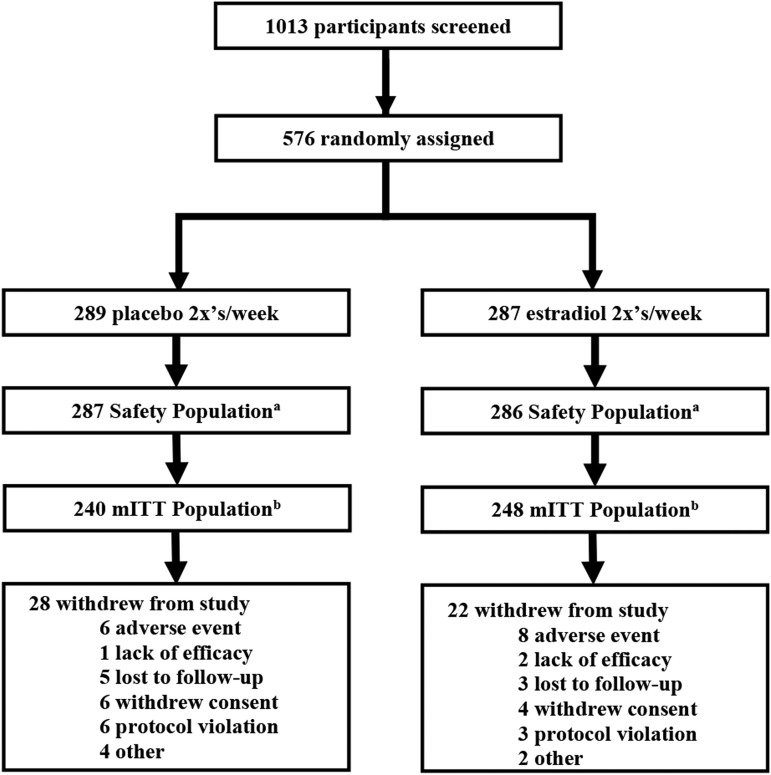

A total of 576 participants were randomized in the study: 573 were included in the Safety population and 488 in the mITT population (Fig. 1). The majority of participants were white and had an average age of 59 years (Table 1). The mean (standard deviation) number of study drug applications for both treatment groups combined was 13.7 (1.3) in Weeks 1 and 2 (daily applications) and 19.4 (2.6) after Week 2 (twice weekly applications for 10 weeks), for a total of 32.4 (5.1) applications.

FIG. 1.

Participant disposition. aIncludes all randomized subjects who received at least one dose of study drug. bIncludes safety population participants who had at least one postbaseline primary efficacy assessment and met all of the following inclusion criteria: ≤5% superficial cells on a vaginal wall smear; >5.0 vaginal pH; moderate–severe dyspareunia is the most bothersome symptom. mITT, modified intent-to-treat.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Randomized Participants

| Demographic variablesa | Placebo (n = 287) | Estradiol (n = 286) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 59.8 ± 6.1 | 59.5 ± 6.7 |

| Not Hispanic/Latino ethnicity, n (%) | 262 (91.3) | 255 (89.2) |

| Race, n (%)b | ||

| White | 241 (84.0) | 236 (82.5) |

| Black | 43 (15.0) | 42 (14.7) |

| Asian | 2 (0.7) | 6 (2.1) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 2 (0.7) | 4 (1.4) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0 | 0 |

| Height (m), mean ± SD | 1.62 ± 0.07 | 1.63 ± 0.07 |

| Weight (kg), mean ± SD | 72.4 ± 15.5 | 71.2 ± 15.4 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 27.6 ± 6.1 | 27.0 ± 6.1 |

| Clinical characteristics, mean ± SDc | Placebo (n = 240) | Estradiol (n = 248) |

|---|---|---|

| Vaginal drynessd | 2.5 ± 0.5 | 2.5 ± 0.5 |

| Vaginal pHd | 6.33 ± 0.65 | 6.34 ± 0.65 |

| Percentage of vaginal cellsd | ||

| Superficial | 0.3 ± 1.1 | 0.4 ± 1.1 |

| Parabasal | 46.5 ± 44.8 | 44.2 ± 42.3 |

| Vaginal and/or vulvar irritation/itching | 1.1 ± 1.0 | 1.1 ± 1.0 |

| Dysuria | 0.3 ± 0.7 | 0.4 ± 0.7 |

| Dyspareunia | 2.1 ± 0.9 | 2.1 ± 1.0 |

Vaginal dryness, vaginal/vulvar irritation/itching, dysuria, and dyspareunia severity scores: 0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe.

Safety population.

Three participants reported multiple races.

mITT population.

Coprimary assessments.

BMI, body mass index; mITT, modified intent-to-treat; SD, standard deviation.

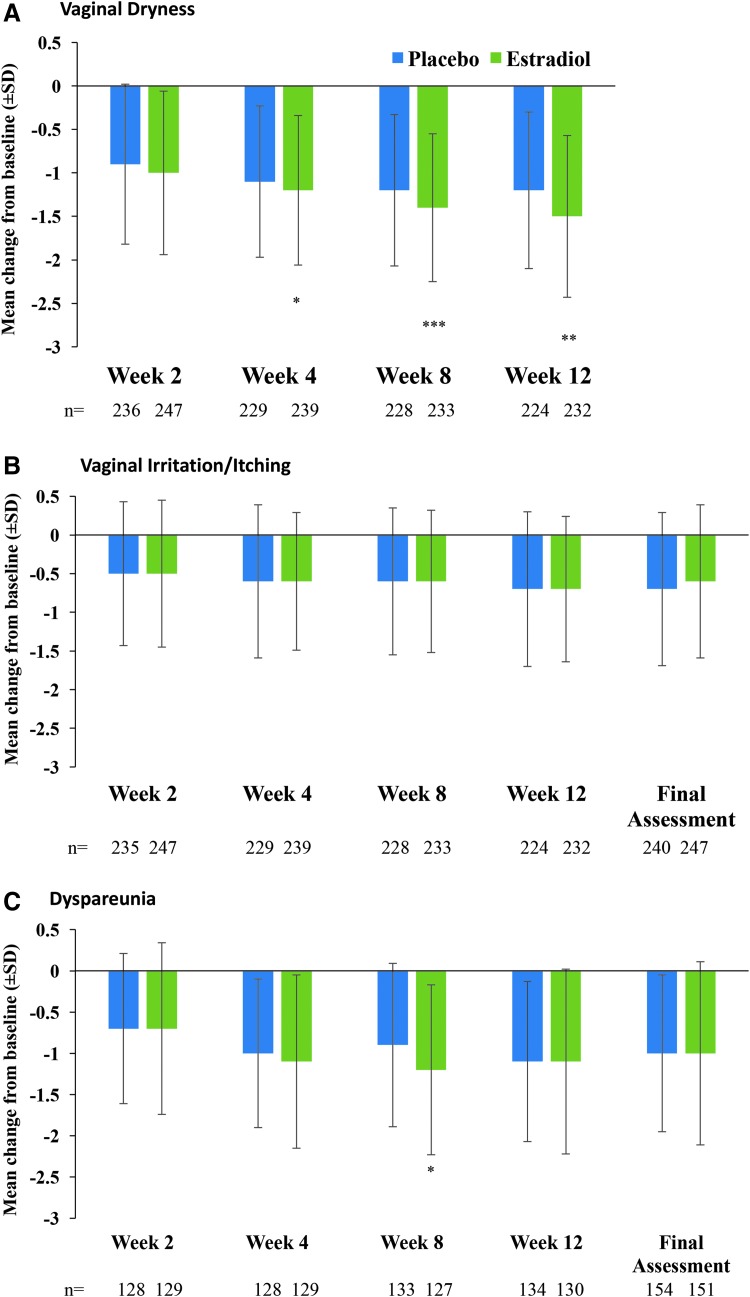

Estradiol significantly reduced the severity of vaginal dryness, decreased vaginal pH, increased the percentage of superficial cells, and decreased the percentage of parabasal cells compared with placebo at final assessment (p ≤ 0.05, all; Table 2). The severity of vaginal dryness was significantly reduced in the estradiol group compared with the placebo group beginning at Week 4 (p = 0.031), and remained lower than baseline through Week 8 (p < 0.001) and 12 compared with placebo (p = 0.006; Fig. 2A). Improvements in severity of vaginal/vulvar irritation/itching (Fig. 2B) or dysuria (data not shown) were similar between placebo and estradiol at all time points. Dyspareunia severity was significantly reduced in the estradiol group compared with the placebo group at Week 8 (p = 0.011; Fig. 2C).

Table 2.

Change from Baseline to Final Assessment in Primary Outcomes (Modified Intent-To-Treat Population)

| Mean ± SD | Placebo (n = 240) | Estradiol (n = 248) | pa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Severity of vaginal dryness | −1.2 ± 0.9 | −1.4 ± 0.9 | 0.013 |

| Vaginal pH | −0.31 ± 0.80 | −1.26 ± 0.99 | <0.001 |

| Percentage of vaginal cells | |||

| Superficial | 0.8 ± 5.7 | 8.6 ± 14.5 | <0.001 |

| Parabasal | −4.4 ± 42.9 | −37.4 ± 42.6 | <0.001 |

Vaginal dryness severity scores: 0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe. Bold indicates significance.

Analysis of covariance on rank versus placebo.

FIG. 2.

Mean (±SD) change from baseline in self-assessed severity of vaginal dryness (A), irritation/itching (B), and dyspareunia (C; mITT population). Vaginal dryness, vaginal/vulvar irritation/itching, and dyspareunia severity scores: 0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe. Data for final assessment for vaginal dryness were a coprimary endpoint and are reported in Table 2 above. ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05 versus placebo. SD, standard deviation.

Of the participants who reported sexual activity at baseline (177 estradiol; 184 placebo), 24.3% (43/177) and 18.5% (34/184) of those in the estradiol and placebo groups, respectively, also reported the presence of sexual activity-related vaginal bleeding. By Week 12, fewer participants reported sexual activity (133 estradiol; 137 placebo) and related bleeding (3.8% [5/133] estradiol; 6.6% [9/137] placebo), although there were no statistically significant differences between the estradiol and placebo groups at any time point. The remaining secondary outcomes (severity of VVA symptoms, pH, and percentage of superficial and parabasal cells on vaginal smear) were significantly improved from baseline at Week 12 in the estradiol group versus the placebo group (p < 0.001, all; Table 3). Severity of VVA symptoms was also significantly improved from baseline at final assessment in the estradiol group versus the placebo group (p < 0.001, all; data not shown).

Table 3.

Change from Baseline to Week 12 in Secondary Outcomes (Modified Intent-To-Treat Population)

| Mean ± SD | Placebo (n = 240) | Estradiol (n = 248) | pa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atrophyb | −0.4 ± 0.7 | −0.7 ± 0.8 | <0.001 |

| Pallorb | −0.4 ± 0.8 | −0.9 ± 0.8 | <0.001 |

| Drynessb | −0.6 ± 0.8 | −1.1 ± 0.9 | <0.001 |

| Friabilityb | −0.5 ± 0.8 | −0.8 ± 0.9 | <0.001 |

| Petechiaeb | −0.4 ± 0.7 | −0.6 ± 0.8 | <0.001 |

| pH | −0.3 ± 0.8 | −1.3 ± 1.0 | <0.001 |

| Percentage of cells on vaginal smear | |||

| Superficial | 0.6 ± 3.4 | 9.3 ± 14.9 | <0.001 |

| Parabasal | −4.7 ± 43.4 | −38.7 ± 41.6 | <0.001 |

Secondary outcomes that were assessed at multiple time points, including Week 12 are shown in Figure 2. Bold indicates significance.

Analysis of covariance on rank versus placebo.

Visual inspection score: 0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, and 3 = severe.

Safety

The number of participants reporting at least one treatment-emergent AE (TEAE) was comparable between the placebo (45.3%) and estradiol groups (46.9%; Table 4). The most commonly reported TEAE with estradiol treatment (occurring in ≥5% of estradiol-treated participants) that had higher incidence than placebo was vulvovaginal mycotic infections (5.2% vs. 1.0%). TEAEs leading to study discontinuation occurred in slightly more participants in the estradiol group (2.8%) than in the placebo group (1.7%). The majority of reported TEAEs were mild or moderate (42.7% estradiol; 43.9% placebo). Serious TEAEs were reported by four participants, two in each treatment group; none led to study discontinuation and none was considered related to study drug (Table 4). No deaths occurred during the study. At study end, no clinically relevant trends in vital signs or laboratory values were observed, and no differences were seen on gynecological examinations between the two treatment groups (data not shown).

Table 4.

Treatment-Emergent Adverse Events (Safety Population)

| n (%) | Placebo (n = 287) | Estradiol (n = 286) |

|---|---|---|

| At least one TEAE | 130 (45.3) | 134 (46.9) |

| At least one treatment-related TEAE | 50 (17.4) | 52 (18.2) |

| TEAEs leading to discontinuation | 5 (1.7) | 8 (2.8) |

| Serious TEAEs | 2 (0.7) | 2 (0.7) |

| Deaths | 0 | 0 |

| TEAEs occurring in ≥5% of participants in the estradiol treatment group | ||

| Urinary tract infection | 17 (5.9) | 15 (5.2) |

| Vulvovaginal mycotic infection | 3 (1.0) | 15 (5.2) |

This table presents the no. (%) of subjects with at least one event in the respective category. Related TEAEs are events reported with “possible” or “probable” relationship to study drug.

TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that a very low-dose estradiol vaginal cream (0.003%/15 μg/application) met all three coprimary endpoints in postmenopausal women with VVA; it was efficacious in reducing the severity of vaginal dryness, decreasing vaginal pH, and improving the percentage of superficial cells while reducing parabasal cells on vaginal smears from baseline to final assessment when compared with placebo. The results also demonstrate that local low-dose delivery of estrogen directly to the vagina, even at 15 μg/dose, is a highly effective mode of treatment for postmenopausal women experiencing VVA-associated vaginal dryness. The advantage of this approach is the lack of appreciable increase in systemic estrogen exposure.5

Improvements in irritation/itching, vaginal bleeding associated with sexual activity, and dysuria were similar between estradiol and placebo. In addition, dyspareunia improved similarly in the estradiol and placebo groups (except for greater improvement with estradiol observed at Week 8). This may have been the result of enrolling participants with vaginal dryness as the most bothersome VVA-related complaint at baseline; thus, baseline ratings of sexual activity-related vaginal bleeding or dysuria were mild or absent in many participants. For example, while a systematic review of vaginal estrogen for VVA treatment found that patients using vaginal estrogen showed improvements in vulvovaginal signs compared with those using nonhormonal moisturizers, there was not enough evidence to conclude that the treatments differed in terms of individual vulvovaginal and urinary symptom improvement. Only patients who had two or more vulvovaginal symptoms showed statistically greater improvement with vaginal estrogen.10 Another possibility is that the estradiol and placebo used in the present study may have had similar symptom outcomes due to the moisturizing effects of both creams. Regular use of vaginal moisturizers has been shown to be similarly effective to topical vaginal estrogen treatments in relieving mild vulvovaginal symptoms.11 There is no evidence, however, that these products provide any long-term relief as they do not reverse many atrophic signs.2,11

In contrast to the FDA-approved vaginal estrogen creams currently on the market, Premarin® (0.625 mg/g)12 and Estrace® 0.01% (0.1 mg/g),8 estradiol 0.003% provides a lower vaginal dose of 30 μg/g (15 μg/0.5g in this study) per application, which is similar to the lower dose vaginal estradiol tablets currently available in the US (10–25 μg/tablet).13 This approach is congruent with the FDA and NAMS recommendations to use the lowest effective vaginal estrogen dose for VVA treatment to reduce systemic exposure.5,6 Additional justification to prescribe appropriately low estrogen doses is that many postmenopausal women with VVA using a prescription estrogen treatment report have concerns over long-term safety, hormone exposure, and general side effects,3 and as such, concerns may negatively impact medication adherence.14 Furthermore, local application of low-dose local estrogen may be an appropriate treatment for some women who have moderate–severe VVA and for whom systemic absorption of estrogen might present greater risk than benefit.5

Treatment with the estradiol cream was well tolerated as indicated by the similar rates of TEAEs and related discontinuations between the two treatment groups; one exception is that vulvovaginal mycotic infections were more frequent in the estradiol group. This finding was not unexpected and may reflect the impact of estrogen on decreasing vaginal pH, a shift in the vaginal biome,15 or a direct effect of estrogen on candida species.16 No serious TEAEs were considered treatment related or led to discontinuations and no deaths occurred. Due to the lack of long-term clinical trial data on endometrial safety with low-dose vaginal estrogen treatment for VVA symptoms, appropriate progestin doses were provided after study participation to those women who had an intact uterus.5

A limitation of this study is that the majority of the enrolled participants identified as white. Thus, the findings may not be generalizable to all racial/ethnic groups. In addition, estradiol levels were not measured in this study, and therefore, no conclusive statements can be made regarding the systemic exposure or lack thereof from the topical estradiol treatment. Low-dose vaginal estrogen treatments of ≤25 μg have been shown to reduce systemic estrogen exposure as opposed to higher doses (50–2000 μg estradiol)7 and, consequently, it is unlikely that the vaginal estradiol dose utilized in the current study (15 μg/0.5 g) produced significant systemic estrogen levels.

A strength of this study was the dosing regimen with local estradiol vaginal cream, which starts initially with a daily priming dose for 2 weeks and then decreases the dosing frequency to a lower maintenance level, reflecting current clinical practice.5 The very low dose contained in the estradiol cream was effective in reducing the severity of vaginal dryness suggesting that it may be a useful treatment option for women who have VVA with this primary complaint. Furthermore, the low vaginal dose may help ease patients' safety concerns regarding systemic hormonal exposure.

Conclusions

Estradiol vaginal cream (0.003%) dosed twice weekly with 15 μg/0.5 g per application is a well tolerated and effective treatment for VVA and dryness in postmenopausal women. This dosing regimen reflects current clinical guidelines for lower dose estrogen treatment. Very low-dose estradiol vaginal cream may provide another treatment option for patients who express concerns regarding the safety of systemic estrogen exposure or for those whom greater doses of estrogen are contraindicated.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing and editorial assistance for this article were provided by Lynn M. Anderson and Jacqueline Benjamin of Prescott Medical Communication Group (Chicago, IL) and funded by Allergan plc.

Author Disclosure Statement

D.F.A. reports grants from Actavis/Allergan; grants and personal fees from Bayer Healthcare, grants and personal fees from Endoceutics, personal fees and other from Agile Therapeutics, personal fees from Exeltis, grants from Glenmark, other from InnovaGyn, grants and personal fees from Merck, personal fees from Pfizer, grants and personal fees from Radius health, personal fees from Sermonix Pharmaceuticals, grants and personal fees from Shionogi, personal fees from TEVA Women's healthcare, grants, and personal fees from TherapeuticsMD outside the submitted work. T.D.K. is on the speakers bureau for Allergan plc. F.D.Y.L., S.B., and V.S. are employees of Allergan plc. J.H.L. is a consultant to Allergan and Pfizer. Dr. Liu is also involved in clinical trials funded by Ferring Pharmaceuticals, AbbVie, Bayer, Palatin, and Allergan.

References

- 1.Portman DJ, Gass ML. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: New terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women's Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society. Menopause 2014;21:1063–1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gandhi J, Chen A, Dagur G, et al. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: An overview of clinical manifestations, pathophysiology, etiology, evaluation, and management. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;215:704–711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kingsberg SA, Wysocki S, Magnus L, Krychman ML. Vulvar and vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: Findings from the REVIVE (REal Women's VIews of Treatment Options for Menopausal Vaginal ChangEs) survey. J Sex Med 2013;10:1790–1799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Family Physician, eds. Practice guidelines: ACOG releases clinical guidelines on management of menopausal symptoms. Am Fam Physician 2014;90:338–340 [Google Scholar]

- 5.The 2017 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause 2017;24:728–753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Food and drug Administration. Industry Guidance: Estrogen and estrogen/progestin drug products to treat vasomotor symptoms and vulvar and vaginal atrophy symptoms—Recommendations for clinical evaluation. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santen RJ. Vaginal administration of estradiol: Effects of dose, preparation and timing on plasma estradiol levels. Climacteric 2015;18:121–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Estrace® (estradiol USP, 0.01% vaginal cream). US prescribing information. Allergan USA, Inc, Irvine, CA, 2015. Available at: www.allergan.com/assets/pdf/estrace_pi Accessed November20, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conover WJ, Iman RL. Analysis of covariance using the rank transformation. Biometrics 1982;38:715–724 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rahn DD, Carberry C, Sanses TV, et al. Vaginal estrogen for genitourinary syndrome of menopause: A systematic review. Obstet Gynecol 2014;124:1147–1156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sinha A, Ewies AA. Non-hormonal topical treatment of vulvovaginal atrophy: An up-to-date overview. Climacteric 2013;16:305–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Premarin® (conjugated estrogens vaginal cream). US prescribing information. Philadelphia, PA: Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc., subsidiary of Pfizer, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vagifem® (estradiol vaginal inserts). US prescribing information. Plainsboro, NJ: Novo Nordisk Inc, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med 2005;353:487–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shen J, Song N, Williams CJ, et al. Effects of low dose estrogen therapy on the vaginal microbiomes of women with atrophic vaginitis. Sci Rep 2016;6:24380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng G, Yeater KM, Hoyer LL. Cellular and molecular biology of Candida albicans estrogen response. Eukaryot Cell 2006;5:180–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]