Abstract

The hematological malignancies classified as Mixed Lineage leukemias (MLL) harbor fusions of the MLL1 gene to partners that are members of transcriptional elongation complexes. MLL-rearranged leukemias are associated with extremely poor prognosis and response to conventional therapies and efforts to identify molecular targets are urgently needed. Using mouse models of MLL-rearranged acute myeloid leukemia (AML), here we show that genetic inactivation or small molecule inhibition of the protein arginine methyltransferase PRMT5 exhibit anti-tumoral activity in MLL-fusion protein driven transformation. Genome wide transcriptional analysis revealed that inhibition of PRMT5 methyltransferase activity overrides the differentiation block in leukemia cells without affecting the expression of MLL-fusion direct oncogenic targets. Furthermore, we find that this differentiation block is mediated by transcriptional silencing of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 (CDKN1a) gene in leukemia cells. Our study provides pre-clinical rationale for targeting PRMT5 using small molecule inhibitors in the treatment of leukemias harboring MLL-rearrangements.

Introduction

MLL-fusion leukemias represent a paradigm for determining how epigenetic dysregulation leads to the corruption of transcriptional programs in cancer initiating cells. In these types of leukemia, the DNA binding domain of the histone methyltransferase MLL1 is fused with one of several possible partners that are part of transcriptional complexes (1, 2). MLL1 is the founding member of a family of histone methyltransferases and it directs the expression of genes essential for hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) maintenance and homeostasis (3). Hence, MLL fusions lead to deregulated expression of stem cell genes and this corrupted gene expression program enforces a differentiation block characteristic of these leukemias. Both HSCs and committed myeloid precursors are targets for MLL-fusion transformation and the gene signatures of these leukemic initiating cells combine features of both HSC and myeloid precursor gene expression (1, 2). It has become clear that tight and intricate epigenetic regulation takes place during transformation and several studies have focused on histone lysine methylation aiming at identifying epigenetic targets for the treatment of MLL-translocated leukemias (4). For example, we previously found that the histone methyltransferase MLL4 (KMT2D) is required for stem cell activity and an aggressive form of MLL-fusion acute myeloid leukemia (AML) harboring the MLL-AF9 oncogene (5). However, less is known about the second major type of protein methylation, arginine methylation, in MLL-fusion protein driven transformation.

Arginine methylation is a prevalent post-translational modification found on both nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins. Three distinct types of methylation are found on the guanidine group of arginine residues in mammalian cells: monomethylated (MMA), symmetrically dimethylated (SDMA) and asymmetrically dimethylated (ADMA), with potential different functional consequences for each methyl state. These methyl states are catalyzed by a family of protein arginine methyltransferases, termed PRMTs. There are nine PRMTs – type I and type II enzymes catalyze the formation of a MMA intermediate, then type I PRMTs (PRMT1, 2, 3, 4, 6 and 8) further catalyze the production of ADMA, while type II PRMTs (PRMT5 and 9) catalyze the formation of SDMA (6). Of the nine PRMTs encoded in mammalian genomes, the type II protein arginine methyltransferase PRMT5 has been extensively characterized as a histone methyltransferase that modifies H4R3, H2AR3 and H3R8(7–11). PRMT5 also methylates several non-histone proteins(12–17), thereby potentially affecting multiple signaling pathways. Lowering the levels of PRMT5 is associated with reduced cell growth, whereas PRMT5 overexpression causes cellular hyperproliferation (10, 18). Overexpression or increased PRMT5 enzymatic activity is observed in several cancers, including lymphoma and leukemia (10, 18, 19). A recent study suggested an important role for PRMT5 in lymphomagenesis triggered by multiple oncogenic drivers with knockdown experiments showing evidence for a strong selection to maintain PRMT5 expression in MLL-AF9 cells (20). In vitro and in vivo efficacy of a selective PRMT5 inhibitor (PRMT5i), EPZ015666 (also called GSK3235025) in mouse models of mantle cell lymphoma was recently reported (21). Yet another recent study using a small molecule inhibitor of PRMT5, describes a positive feedback loop between PRMT5 and BCR-ABL in chronic myeloid leukemia (22). Although we have recently described the effects of conditional deletion of PRMT5 in mouse hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells and characterized the role of PRMT5 in normal hematopoiesis (23), similar studies have not been performed in the context of MLL-rearranged leukemia. Using mouse models of these aggressive leukemias, here we establish that genetic deletion of PRMT5 or inhibition of PRMT5 methyltransferase activity with a small molecule inhibitor impairs MLL-rearranged leukemia in vitro and in vivo, without affecting the expression of MLL-fusion direct oncogenic targets. Furthermore, we show that PRMT5 is required to enforce the differentiation block characteristic of these leukemias by mediating silencing of CDKN1a (p21). Our study suggests that PRMT5 inhibition holds a therapeutic potential in MLL-rearranged leukemia.

Materials and Methods

Animal studies

CB17 SCID or NOD SCID from Jackson Laboratory were injected with 1 X 105 MLL-ENL/RasG12D cells by intravenous tail-vein injection and were treated with 150 mg/kg EPZ015666 formulated in 0.5% methylcellulose (Sigma-Aldrich) solution in water or 0.5% methylcellulose solution in water (vehicle) by oral gavage administration twice a day. For whole-body bioluminescent imaging, mice were injected with 150 mg/kg D-luciferin (Goldbio) intraperitoneally and after 10-15 minutes, analyzed using an IVIS Sectrum system (Caliper LifeSciences).

For transplantation experiments using PRMT5flox/flox Mx1Cre animals (23), recipient mice were sub-lethally irradiated at 4.75Gy. For each mouse in primary transplants, approximately 0.5 to 1x106 total fetal liver cells with 10 to 20% of GFP+ (expressing MLL-AF9) cells were injected (the total number of cells was adjusted according to the GFP percentage, so that every mouse received the same number of GFP+ cells). For secondary transplants, 1x104 spleen cells with >90% GFP were injected per mouse.

Mice used for all experiments were 8 to 12 weeks of age.

All animal experiments were approved by the IACUC of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and the University of Miami.

Cell culture

Mouse MLL-ENL/NrasG12D cells were kindly provided by I. Zuber. MLL-AF9 cells were derived from bone marrow obtained from terminally ill recipient mice, and were cultured in RPMI-1640 (Gibco-Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 mg/ml streptomycin. BOSC cells were grown in DMEM (Gibco-Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 mg/ml streptomycin. All human leukemic cell lines were cultured in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 5% penicillin/streptomycin and 5% L-glutamine (100 mM), except Kasumi-1 cells, which were cultured in 20% FBS. Human leukemia lines were provided by the IACS (Institute for Applied Cancer Science) at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. To generate knockdown cell lines, BOSC cells were grown to 80% confluence and transfected with shRNA (Transomic Technologies) targeting the gene required by the experiment and helper plasmid (pCL-Eco). Transfection was done using XtremeGene9 DNA transfection reagent (Roche). After 48 hours, the viral supernatant was collected and infected into MLL-ENL/RasG12D cells using 5 ng/ml IL3, 5 ng/ml IL6, 100 ng/ml SCF and 10 μg/ml polybrene in the culture media. After 24 hours, virus was removed and media was replaced with fresh media. Cells were allowed to grow for 72 hours and selection was performed with Geneticin (G418, Life Technologies) at 1 mg/ml for 5 days. After selection cells were subsequently cultured with 0.2 mg/ml G418. To perform proliferation assays, cells in log phase were cultured at a seeding density of 0.25 million cells/ml in 2-4 ml of media depending on the yield required at the end of the experimental period. The PRMT5 inhibitor was dissolved in DMSO at the concentration of 5 mM and the cells were treated with the compound at the final concentration of 5 μM. The andcells for control were treated with equal concentration of DMSO. The cells were treated again on Day 2. At the end of each treatment period, cells were counted using the Nexcelom Cellometer and AOPI staining. Relative proliferation rates were calculated by normalizing to the rate of DMSO-treated cells.

May-Grünwald-Giemsa cytospin staining and Microscope imaging acquisition

Cells at the end of the experimental period were harvested by centrifugation (1500 rpm, 5 minutes) and cell pellets were re-suspended in PBS with 5% FBS. 75,000 cells were cytospun onto glass slides at 800 rpm for 5 minutes. May-Grünwald (Sigma) and Giemsa (Sigma) stainings were performed according to manufacturer’s protocols. Images were collected using Aperio CS imaging platform (Leica Biosystems) with a X20 objective at a spatial sampling of 0.47 um per pixel. Whole-slide images (WSI) were viewed and processed using Spectrum™ ImageScope software (Version 10.2.2.2315).

Flow Cytometry

For all flow cytometry analysis cells were stained in PBS (Corning Cellgro) supplemented with 2% of inactivated FBS (Gemini BioProducts). The following antibodies were used: B220 PE, CD11b PE or APC, CD11C PE or APC, CD4 PE, CD8 PE, NK1.1 PE, Ter119 PE, CD3 PE, c-Kit APC or biotin-conjugated (BD Biosciences). Sca-1 PEcy7, streptavidin-APC (eBiosciences) and streptavidin Pacific blue (Invitrogen). DAPI was used to exclude dead cells. Edu incorporation assays were performed according to manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen, Click-iT Edu Alexa Fluor 647 Imaging kit), with cells pulsed with Edu for 30 minutes. Cells were co-stained with DAPI for DNA content measurement. Annexin V apoptosis staining was performed according to manufacturer’s protocol (BD Pharmingen, APC Annexin V). All flow cytometry was performed on a LSR Fortessa (BD Biosciences).

Western Blot analysis

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer with Protease Inhibitor Cocktail tablet (Roche), sonicated on ice and spun at 4°C. The supernatant was assayed for protein concentration by BCA (Pierce). 30μg protein was resolved by SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to nitrocellulose for blotting. Blots were blocked with 3% milk in PBST solution at room temperature and then incubated with primary antibody (SDMA: Cat#13222S; Cell Signaling Technologies, p21: Cat# SC6246; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, p53: Cat# SC126; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, PRMT5: Cat# 61001; Active motif, β-actin: Cat# A1978; Sigma. All antibodies were prepared at dilutions according to manufacturer’s protocol in blocking buffer) at 4°C overnight and secondary antibody (Sheep Anti-Mouse: Cat# NXA931; GE Healthcare and Goat Anti-Rabbit: Cat# NA934; GE Healthcare; prepared at 1:10000 in blocking buffer) at room temperature for 2 hours.

qPCR

Cells were spun down and washed once with cold PBS, then RNA isolated with a QIAGEN RNeasy kit (Cat# 74104; QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. 1μg of total RNA was treated with amplification-grade DNaseI (Cat# 79254; QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and reverse-transcribed with the SuperScriptIII Supermix system (Cat# 11752-250; Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. mRNA levels were analyzed via qPCR analysis using the BIORAD Supermix according to manufacturer’s protocol. Reactions were performed on an ABI 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR system. Samples were normalized to transcripts encoding Gapdh.

p21: 5’ CTGGGAGGGGACAAGAG and GCTTGGAGTGATAGAAATCTG 3’ Gapdh: 5’ TGACGTGCCGCCTGGAGAAA and AGTGTAGCCCAAGATGCCCTTCAG 3’

RNA-Seq

RNA-Seq sequencing libraries were made from MLL-ENL/RasG12D cells following Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The libraries were sequenced using 2x75 bases paired end protocol on Illumina HiSeq 2000 instrument. The libraries were sequenced using 2x75 bases paired end protocol on Illumina HiSeq 2000 instrument. Totally 6 libraries (three biological replicates per condition) were sequenced in one lane, generating 17-26 million pairs of reads per sample. Each pair of reads represents a cDNA fragment from the library. Mapping: The reads were mapped to the mouse genome (mm10) by TopHat (version 2.0.10) (24). By reads, the overall mapping rate is 85-96%. 76-94% fragments have both ends mapped to the mouse genome. Differential Expression: The number of fragments in each known gene from RefSeq database (downloaded from UCSC Genome Browser on July 17, 2015) was enumerated using htseq-count from HTSeq package (version 0.6.0) (25). Genes with less than 10 fragments in all the samples were removed before differential expression analysis. The differential expression between conditions was statistically assessed by R/Bioconductor package DESeq (version 1.16.0) (26). Genes with FDR (false discovery rate) ≤ 0.05, fold change ≥ 2 and length > 200bp were called as differentially expressed. Landscape profile of RNA-Seq signal: For the fragments that have both ends mapped, the first reads were kept. Together with the reads from the fragments that have only one end mapped, every read was extended to its 3' end by 200 bp in exon regions. For each read, a weight of 1/n was assigned, where n is the number of positions the read was mapped to. The sum of weights for all the reads that cover each genomic position was rescaled to normalize the total number of fragments to 1M and averaged over 10bp resolution. The normalized values were displayed using UCSC genome browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/). Gene Clustering and Heatmap: Hierarchical clustering was performed by hclust function in R using gene expression values estimated by DESeq. The expression values of each gene across samples were centered by median and scaled by standard deviation before clustering. Euclidean distance and ward.D2 clustering method were used. The heatmap was plotted by heatmap.2 function in R. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis: Gene set enrichment analysis was performed by GSEA software (version 2.2.1) (27). The expression values estimated by DESeq for all the genes were taken as the expression dataset. The permutation type was set as "gene_set" and all the other parameters were set as default.

TCGA data analysis

To get a whole landscape of CDKN1a gene expression in different cancers, we extracted its gene expression values across thirty two different cancer types from the TCGA database, sorted the gene expression mean values based on each tumor type in an increasing order, then boxplot gene expression for each tumor.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Analysis

Cells were grown to 80% confluence, washed twice in warm PBS, trypsinized, and re-suspended in warm media containing 0.1 volume crosslinking solution (Kondo et al., 2004). ChIP reactions were performed as described previously (Martens et al., 2005) followed by DNA purification with a Qiaquick PCR Cleanup kit (Cat# 28106; Qiagen). Antibodies used include: anti-H4R3me2s (Cat# ab5823; Abcam), anti-H3K4me3 (Cat# 04-745; Millipore), anti-H3K27me3 (Cat# 07-449; Millipore), and anti-p53 (Cat#2524, Cell Signaling Technology). Antibodies for modified histones and p53 were added at 1ug to 5ug/ChIP reaction. The concentration of IgG (Cat# 12-370; Millipore) was adjusted from 1μg to 5μg as appropriate. For qPCR analysis, real-time PCR was performed with the iTaq SYBRgreen Supermix (Cat# 172-5121; Biorad) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Primer sequences were derived from the enhancer and promoter regions of CDKN1a. Reactions were performed on an ABI 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR system.

Statistical analyses

Multiple independent biological experiments were performed to assess the reproducibility of experimental findings. Each group is presented by mean ± s.d. To compare two experimental groups, statistical tests were conducted using R statistical language (http://r-project.org). Unpaired, two-tailed t-tests were used for all analyses. For ex vivo experiments, multiple independent biological replicates were used. For leukemia transplantation, six to eight recipients per group were used since variation among experiments was low. Animals were placed in different experimental groups and disease development was assessed blindly without prior knowledge of genotype. The significance between the longevity of cohorts was assessed by Kaplan–Meier survival analysis and log-rank (Mantel–Cox) tests. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant to reject the null hypothesis. No randomization was used in any experiment. Statistical analysis of RT-qPCR and ChIP-qPCR data: for analysis of gene expression, the measured cycle threshold (CT) experimental values for each transcript were compiled and normalized to the reference gene glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh—NM_008084). Normalized expression levels were calculated using the DDCT method described previously (Schmittgen and Livak, 2008). Values from these calculations were transferred into the statistical analysis program GraphPad (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA) and unpaired, two-tailed t-tests were run to assay differences between control and treated cells. For samples with p-values < 0.05, we have marked statistically significant differences with asterisks. For quantitative analysis of candidate gene regulatory region enrichment in MLL-ENL/NrasG12D AML cells, ChIP samples were normalized to 1% input, and data were analyzed using the formula previously described (Mukhopadhyay et al., 2008). The cumulative mean from each of the 3 independent experiments was calculated and the standard error of the mean derived. The statistical analysis package GraphPad was used to measure statistical significance between the percent input for the control and PRMT5i-treated samples using unpaired, two-tailed t-tests to assay differences between control and treated cells.

Results

Loss of PRMT5 impairs the initiation and maintenance of MLL-rearranged leukemia

Homozygous deletion of PRMT5 results in early embryonic lethality (28). In order to investigate the role of PRMT5 in MLL-fusion leukemia, we developed a conditional knockout mouse model by crossing mice that carry loxP sites flanking exon 7 of PRMT5 (PRMT5flox/flox) (23), with transgenic mice expressing interferon-inducible MxCre (Mx1-Cre) or estrogen receptor (ER)-inducible cre (ER-Cre). Deletion of PRMT5 can be induced by polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (poly:IC) or tamoxifen administration, respectively.

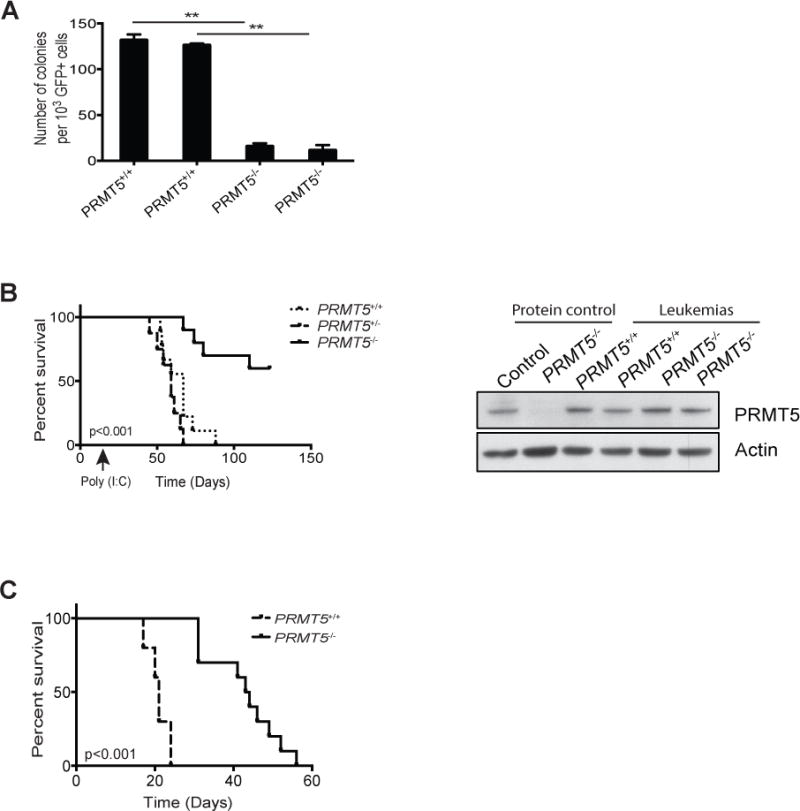

We have previously shown that the lysine methyltransferase MLL4 is required for the initiation and maintenance of AML in a mouse model of human AML containing a translocation between MLL1 and AF9 genes (5, 29). To determine whether the arginine methyltransferase PRMT5 modifies MLL-AF9 leukemia, we first introduced MLL-AF9 into PRMT5flox/flox and PRMT5flox/flox ER-Cre bone marrow hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells with a retrovirus marked with green fluorescent protein (GFP) (MLL-AF9-IRES-GFP) (29). After sorting, GFP+ cells were cultured in semi-solid media with 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT). We found that PRMT5 deletion in vitro (Supplementary Figure 1A) greatly decreased the number of colony forming units (CFU) scored after 7 days (Figure 1A). To evaluate the role of PRMT5 in leukemia development in vivo, we transplanted MLL-AF9-transduced fetal liver cells isolated from E14.5 PRMT5flox/flox, PRMT5flox/+Mx1Cre+ and PRMT5flox/floxMx1Cre+ embryos into sub-lethally irradiated recipient mice. Subsequently, PRMT5 was deleted by administering poly (I:C) injections two weeks after the transplant. All animals in the control and heterozygous groups died of AML in less than 90 days (Figure 1B left panel, Supplementary Figure 1B). However, more than half of the animals that received MLL-AF9 transformed PRMT5flox/floxMx1Cre+ cells survived more than 120 days without showing signs of leukemia (Figure 1B left panel). Leukemias that did develop in these animals were derived from cells that failed to completely delete PRMT5, as shown by the levels of PRMT5 protein present in the GFP+ leukemia cells isolated from these animals (Figure 1B right panel). Consistent with these results, mice receiving MLL-AF9-expressing PRMT5flox/flox and PRMT5flox/+Mx1Cre+ cells exhibited high white blood cell counts (WBC) and low red blood cell (RBC) and platelet (PLT) counts at eight weeks after poly (I:C) injection. The mice that received PRMT5flox/floxMx1Cre+ MLL-AF9 transformed cells had normal blood counts at that time (Supplementary Figure 1C). Moreover, mice that received PRMT5flox/floxMx1Cre+ cells had consistently lower levels of GFP+ cells in the peripheral blood. In contrast, the levels of GFP+ cells in the peripheral blood of PRMT5flox/flox control and PRMT5fl/+ MxCre+ heterozygous cell recipients increased from around 3% at week two to 60% at week eight (Supplementary Figure 1D & 1E). Thus, PRMT5 appears to play an essential role in the initiation of MLL-AF9 - mediated leukemia in vivo.

Figure 1. PRMT5 is required for the initiation and maintenance of MLL-AF9-induced leukemia.

A) Bone marrow cells isolated from PRMT5flox/flox (PRMT5+/+) and PRMT5flox/flox Mx1Cre+ (PRMT5-/-) mice previously injected with polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (poly (I:C)) were infected with retrovirus expressing the MLL-AF9 fusion gene and GFP as a mark. GFP+ cells were sorted by FACS and plated in methylcellulose medium supplemented with 0.5 μM hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT). Colonies were scored 7 days later. B) CD45.1 recipient mice were subject to sub-lethal irradiation and transplanted with MLLAF9-transduced fetal liver cells isolated from PRMT5flox/flox (PRMT5+/+) PRMT5flox/+Mx1Cre+ (PRMT5+/-) and PRMT5flox/floxMx1Cre+ (PRMT5-/-) embryos, together with 1x106 wild-type helper bone marrow cells. Poly (I:C) injections were administered two weeks after the transplant. The survival curve of the recipient mice is shown in the left panel. n=8 to 10. Bone marrow cells were isolated from moribund leukemic mice and the levels of PRMT5 and β-actin in these cells were determined by western blot (right panel). WT and PRMT5-deficient mouse bone marrow cells were used as protein controls. C) Spleen cells isolated from primary leukemic mice of PRMT5flox/flox (PRMT5+/+) and PRMT5flox/flox Mx1Cre+ (PRMT5-/-) groups (without poly (I:C) injection) were transplanted into sub-lethally irradiated mice and poly (I:C) injections were given to these mice when the peripheral blood GFP+ cells reached 10 to 20%. The survival curve of the secondary transplanted mice is shown. n=5 to 6. **p<0.01.

We next determined the role of PRMT5 in the maintenance of established MLL-AF9 leukemia. PRMT5flox/flox and PRMT5flox/floxMx1Cre+ AML was isolated from moribund mice (without poly (I:C) injections), and spleen cells from these primary leukemias (90% GFP+) were injected into sublethally irradiated secondary recipients. Deletion of PRMT5 was induced in transplanted animals when the frequency of GFP+ cells in the peripheral blood reached 1-30%. One week after poly (I:C) injection, mice that received PRMT5flox/floxMx1Cre+ cells had significantly lowered the levels of GFP+ cells in the peripheral blood (from 12% to 3%). In contrast, the levels of GFP+ cells in the peripheral blood of PRMT5flox/flox control cell recipients increased from 7% to 80%, and these animals succumbed to AML in the subsequent week (Supplementary Figure 1F & 1G and Figure 1C). PRMT5 deletion did prolong the average survival from 3 weeks in the control group to 7 weeks in the PRMT5flox/floxMx1Cre+ group. Together, our data demonstrate that PRMT5 is required for the initiation and maintenance of MLL-rearranged leukemia.

AML growth is sensitive to PRMT5 inhibition

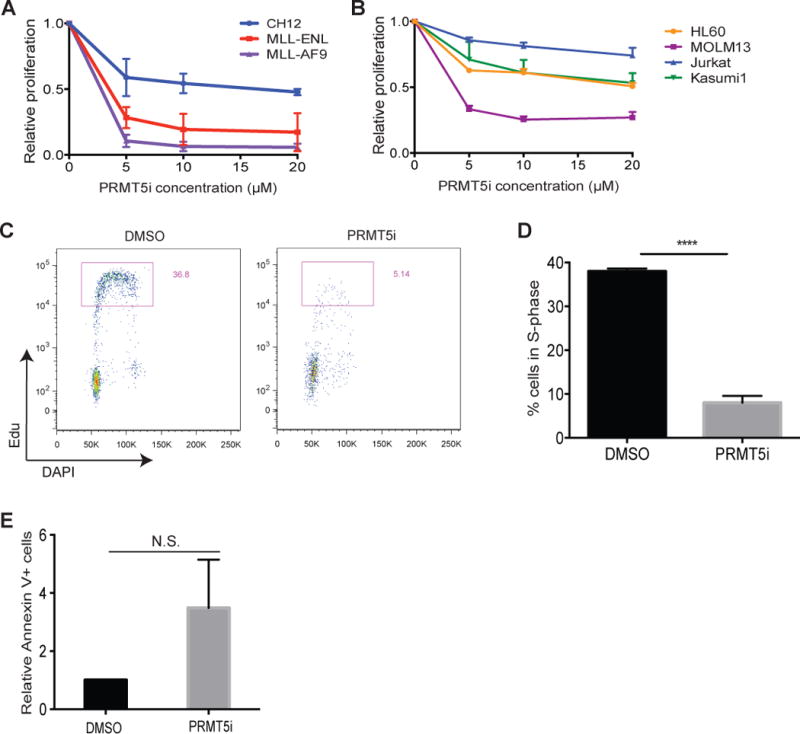

The recent identification of a potent small-molecule PRMT5 inhibitor, EPZ015666 (21), together with our data showing that genetic loss of PRMT5 impairs the initiation and maintenance of MLL-fusion AML (Figure 1) prompted us to investigate the sensitivity of leukemia cells to small molecule inhibition of PRMT5 activity. Proliferation of mouse myeloid leukemia cells was notably sensitive to PRMT5 inhibition, as compared to proliferation of murine CH12 B-cell lymphoma cells (Figure 2A). We also examined growth-inhibitory effects of EPZ015666 in established human AML leukemia lines representing diverse disease subtypes. We observed growth-suppressive activity in all AML lines, with MLL-fusion translocation positive MOLM13 cells showing the most sensitivity. We also tested a T cell–leukemia line (Jurkat) that showed minimal sensitivity to the compound (Figure 2B). Because leukemic cells expressing MLL-fusions appear more sensitive to the inhibition of PRMT5, we used a well characterized mouse model of AML induced by overexpression of the MLL-ENL fusion protein and oncogenic Ras (NrasG12D) (30–33) to further investigate the mechanism of dependency. EPZ 015666 treatment triggered cell cycle arrest (Figure 2C&D) and increased the frequency of apoptotic cells (though not enough to reach statistical significance in the apoptosis assays) in MLL-ENL/NrasG12D cells (Figure 2E). Small molecule inhibition of PRMT5 with EPZ0 15666 correlated well with inhibition of symmetric dimethylation of arginine-containing substrates (SDMA) as shown by immunoblot (Supplementary Figure 2A). Together, these data show a requirement for PRMT5 in AML growth that can be effectively inhibited by targeting the PRMT5 methyltransferase activity with EPZ 015666.

Figure 2. AML growth is sensitive to PRMT5 inhibition.

A, B) Proliferation rates of PRMT5 inhibitor (EPZ 015666)- or DMSO- treated cells after four days in culture. Graphs show mean and standard error of three independent experiments. C) Flow cytometry for cell cycle analysis showing the percentage of MLL-ENL/NRasG12D cells in S-phase (5-Ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine- EdU+) after treatment with 5μM of EPZ 015666 for three days. EdU was pulsed for 30 minutes. One representative of three experiments is shown. D) Bar graph represents the frequency of cells in S phase (measured as in C) with mean and standard error of three independent experiments. ****p<0.0001. E) Frequency of Annexin positive PI negative cells after treatment of MLL-ENL/NRasG12D cells with 5μM of EPZ 015666 for four days. Bar graphs show mean and standard deviation of three independent experiments.

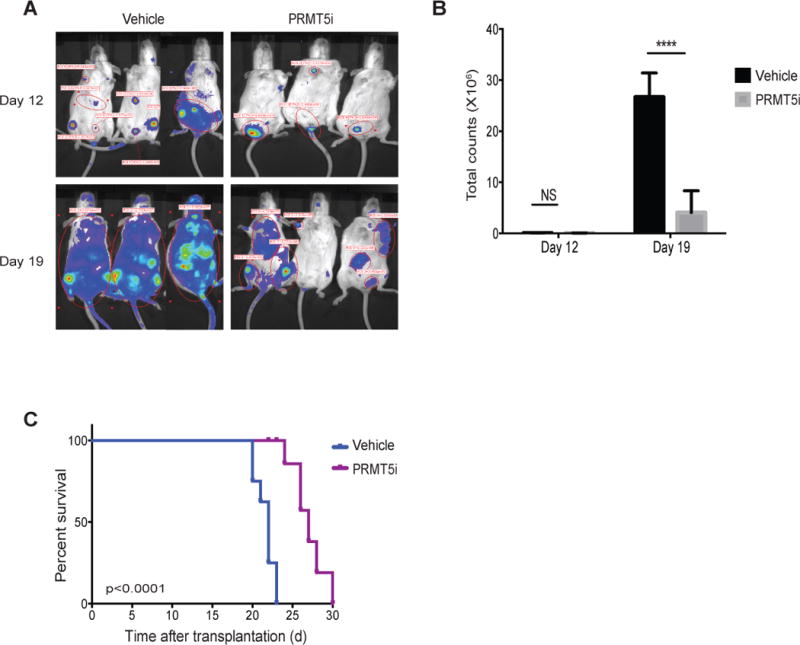

EPZ 015666 has anti-leukemia effects as a single agent in vivo

The MLL-ENL/NrasG12D model has proven particularly suitable to test the effect of small-molecule inhibitors of epigenetic pathways in MLL-fusion AML (33, 34). MLL-ENL fusions are co-expressed with enhanced green fluorescence protein (EGFP) and oncogenic NrasG12D is co-expressed with luciferase to enable imaging of the leukemias by bioluminescence (33). Since EPZ 015666 is orally bioavailable (21), mice transplanted with MLL-ENL/NrasG12D leukemia cells were administered by oral gavage a dose of 150 mg kg-1 B.I.D. of this drug. We chose this dose based on previous studies using EPZ015666 in mantle cell lymphoma models. Higher doses were shown to confer increased levels of toxicity in treated animals (21). EPZ 015666 administration resulted in a significant delay in disease progression and increased survival (Figure 3A–C). The advantage in median survival is similar to that reported using this aggressive AML mouse model following treatment with the bromodomain and extra terminal protein (BET) small molecule inhibitor JQ1 in similar settings (34). We observed a profound reduction in the symmetric dimethylation of arginine-containing substrates (SDMA) upon EPZ 015666 treatment, as shown by immunoblot of cells isolated from the spleens of moribund mice (Supplementary Figure 3A). Consistent with published findings, EPZ 015666 was well tolerated in mice at the indicated dose (21) and had no impact on hematopoiesis when administered to control animals (Supplementary Figure 3B,C & Supplementary Figure 4). We conclude that EPZ015666 has specific anti-leukemia effects as a single agent in vivo.

Figure 3. EPZ 015666 has anti-leukemia effects as a single agent in vivo.

A) Bioluminescent imaging of mice transplanted with 100,000 MLL-ENL/NrasG12D leukemia cells after treatment with EPZ 015666 (PRMT5i) at the indicated time points. Drug treatment was started one day after the injection of leukemia cells. B) Quantification of bioluminescent imaging responses after treatment. Mean values of three replicate mice are shown. ****p<0.0001. Error bars represent standard error. C) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of control and EPZ015666-treated mice. Statistical significance was calculated using a long-rank test. n=8 for 0.5% methylcellulose-treated and n=6 for EPZ 015666-treated animals.

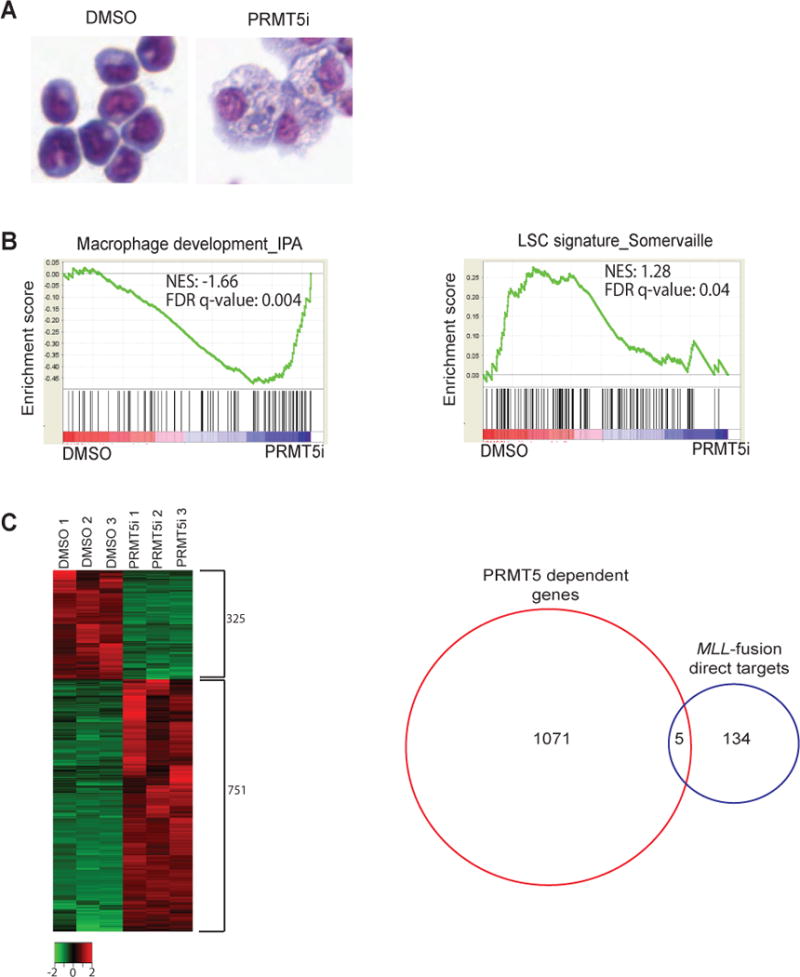

PRMT5 inhibition leads to myeloid differentiation and leukemic stem cell-depletion without affecting the expression of MLL-fusion oncogenic targets

A hallmark of MLL-fusion AML is the block in myeloid differentiation and the acquisition of aberrant self-renewal properties with a concomitant expression of stem cell markers. Previous studies have implicated PRMT5 in promoting cell cycle and inhibiting apoptosis (20, 35), therefore, we considered whether PRMT5 knockdown or PRMT5 inhibition affected the differentiation status of MLL-fusion leukemia cells. PRMT5-deficient MLL-ENL/NrasG12D leukemia cells (PRMT5 shRNAi, >90% efficiency, Supplementary Figure 5A) or treatment of MLL-ENL/NrasG12D leukemia cells with EPZ 015666 resulted in the morphologic change of monomyelocytic blasts to macrophage-like cells (Supplementary Figure 5B,C and Figure 4A). These morphologic changes were accompanied by increased expression of the myeloid differentiation marker Mac1 (Integrin αM) and decreased expression of c-Kit, a stem cell marker associated with MLL-fusion leukemic stem cells (LSCs) (36) (Supplementary Figure 5D). To further determine whether the inhibition of PRMT5 methyltransferase activity compromises the LSC compartment, we performed gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of RNA-seq data from 72h-treated DMSO and EPZ 015666 MLL-ENL/NrasG12D leukemia cells. We observed a significant up regulation of macrophage development-associated genes upon PRMT5 inhibition (Figure 4B left panel). MLL-fusion leukemia cells are comprised of LSCs and non self-renewing leukemia cells. These two populations can be discriminated based on a well-defined gene expression signature (36). GSEA revealed a global down regulation of this gene signature in cells treated with EPZ015666 compared to DMSO- treated cells (Figure 4B right panel). Together, our data show that PRMT5-dependent methylation is required to maintain a leukemic stem cell population and to enforce the myeloid differentiation block characteristic of MLL-fusion leukemias.

Figure 4. PRMT5 inhibition leads to myeloid differentiation and leukemic stem cell-depletion without affecting the expression of MLL-fusion direct oncogenic targets.

A) Light microscopy of May-Grünwald/Giemsa stained MLL-ENL/NRasG12D cells treated with EPZ 015666 (PRMT5i) for four days. One representative of at least three independent experiments is shown. B) GSEA plots evaluating changes in macrophage (left panel) and leukemic stem cell (LSC) gene signatures (right panel) upon EPZ 015666 treatment. C left panel) Heat map of genome wide transcriptome changes in DMSO vs EPZ 015666- treated cells (FDR</= 0.05). C right panel) Fewer than 4% of MLL-fusion direct targets are deregulated by PRMT5 treatment (FDR</=0.05). RNA for RNA-seq analysis was obtained from MLL-ENL/NRasG12D cells treated with DMSO or EPZ 015666 for 72h in three independent experiments.

Our genome-wide analysis showed that EPZ 015666 treatment resulted in down regulation of 325 genes and up regulation of 751 genes (Figure 4C left panel, FDR ≤ 0.05, fold change ≥2). However, 96% of MLL-fusion direct targets (37) were not affected by PRMT5 inhibition (Figure 4C right panel), such as the master MLL-fusion oncogenic factors HOXA9 and MEIS1. This suggests that the LSC signature and LSC self-renewal are compromised by an alternative pathway.

PRMT5 inhibitor-induced differentiation of leukemic cells is dependent on p21

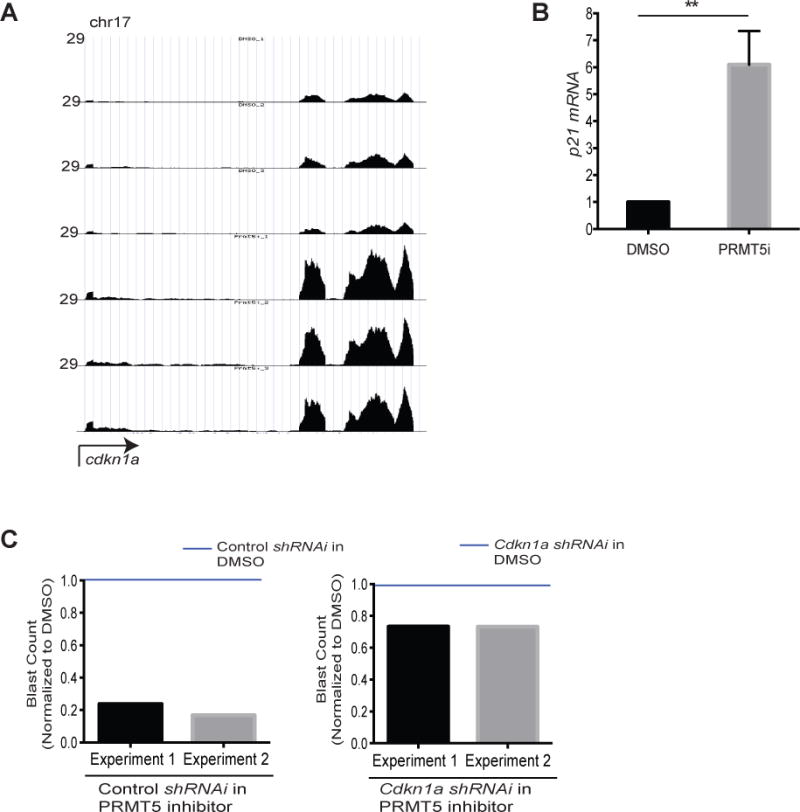

We previously uncovered a connection between cell cycle checkpoint pathways and the “stemness” vs. differentiation status of MLL-fusion cells (5). Using an MLL-AF9 mouse model, we showed that DNA-damage induces the differentiation of MLL-fusion leukemia blasts to myeloid cells and that cell-cycle exit and differentiation of MLL-AF9 cells is coupled to activation of the cell cycle inhibitor p21 (CDKN1a for gene name), as p21-deficient leukemia cells are resistant to DNA damage-induced differentiation (5). Moreover, previous studies have shown that knockdown of p21 in MLL-transformed cells significantly decreases leukemia latency, validating p21 as a biologically important target in vivo (38). Interestingly, the gene encoding p21, CDKN1a, was among the top 20 genes most significantly up regulated in our PRMT5-inhibitor RNA-seq dataset (for the list of the 50 most significantly up regulated and down regulated genes see tables 1 and 2 in supplementary data). We confirmed the up regulation of CDKN1a mRNA by RT-qPCR upon EPZ 015666 treatment (Figure 5A&B) which correlated with a significant increase in p21 protein levels (Supplementary Figure 6A). To directly determine if p21 is required for PRMT5 inhibitor-induced differentiation of leukemia cells, we treated MLL-ENL/NrasG12D p21-deficient cells (CDKN1a shRNA, >90% efficiency, Supplementary Figure 6B) with EPZ 015666 and found that p21-deficient MLL-ENL/NrasG12D cells were resistant to PRMT5-inhibitor-induced differentiation (Figure 5C).

Figure 5. PRMT5 inhibitor- induced differentiation of leukemic cells is dependent on p21.

RNA-seq (same as in Figure 4) read histograms at CDKN1a. The x-axis represents the linear sequence of genomic DNA; the y-axis represents the reads per million aligned reads (RPM). B) mRNA levels detected by qRT–PCR in MLL-ENL/NRasG12D cells treated with EPZ 015666 (PRMT5i) for three days. Bar graph represents mean and standard error of three independent experiments. C) Control and CDKN1a shRNAi MLL-ENL/NrasG12D cells were treated with 5μM EPZ 015666 for four days and the frequency of blasts was determined and normalized to DMSO treated cells in independent experiments. We counted the number of blasts in May-Grünwald/Giemsa stained MLL-ENL/NRasG12D cells (in cytospin slides as in Figure 4A) by microscopy. For each experimental condition we counted the number of blasts per 100 cells in three different fields of the cytospin slides. The bar graphs show the blast counts in PRMT5i-treated cells normalized to DMSO- treated cells (blue lines). **p<0.01.

Silencing of CDKN1a by PRMT5 in leukemia cells

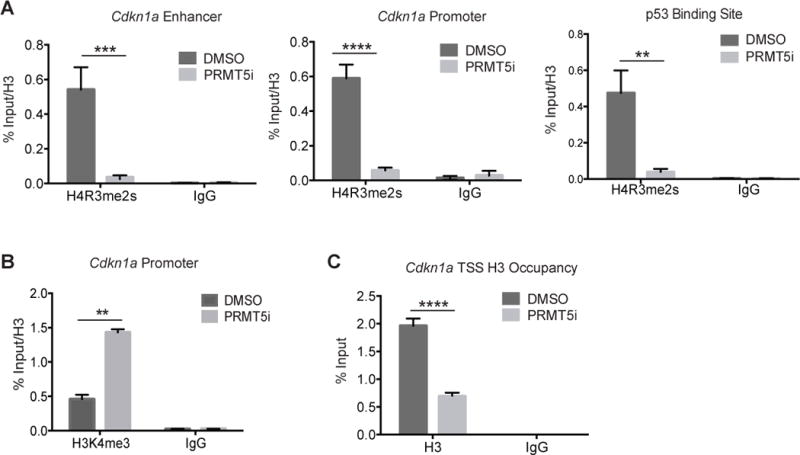

Using a mouse model of T cell lymphoma/leukemia driven by a constitutively nuclear mutant of Cyclin D1 (D1T286A), a recent study showed that PRMT5 overexpression cooperates with mutant Cyclin D1 to drive lymphomagenesis. Coexpression of PRMT5 with D1T286A antagonized induction of a majority of the genes induced by D1T286A alone, including CDKN1a (20). PRMT5 has also been associated with CDKN1a silencing in muscle stem cells (39). Based on these previous findings, we hypothesized that CDKN1a is silenced by PRMT5 in leukemia cells. To evaluate in vivo interactions taking place in well-characterized regulatory regions of the CDKN1a gene (40, 41) (Supplementary Figure 6C), we employed chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (ChIP-qPCR) to demonstrate the location of PRMT5-associated repressive H4R3 symmetric dimethylation marks (H4R3me2s) (7–10). We detected significant enrichment of H4R3me2s to the enhancer region, proximal promoter region and the p53-binding site of CDKN1a. Inhibition of PRMT5 methylation activity upon EPZ 105666 treatment resulted in a marked reduction of H4R3me2s in these regions (Figure 6A), correlating with a de-repression of the chromatin state evidenced by an increase in H3K4me3 at the promoter (Figure 6B) and decreased nucleosome occupancy at the transcriptional start site (TSS) (Figure 6C). Taken together, our data show that PRMT5 promotes epigenetic changes that result in transcriptional silencing of CDKN1a in leukemia cells.

Figure 6. Epigenetic silencing of CDKN1a by PRMT5 in leukemia cells.

Quantitative PCR analyses of ChIP using antibodies against H4R3me2s (A), H3K4me3 (B) and histone H3 (C) at the indicated regulatory regions of the CDKN1a gene locus in MLL-ENL/NRasG12D cells treated with EPZ 015666 (PRMT5i) for 48 hours. Bar graphs show mean and standard error of two independent experiments. **p<0.01; *** p<0.001; **** p<0.0001.

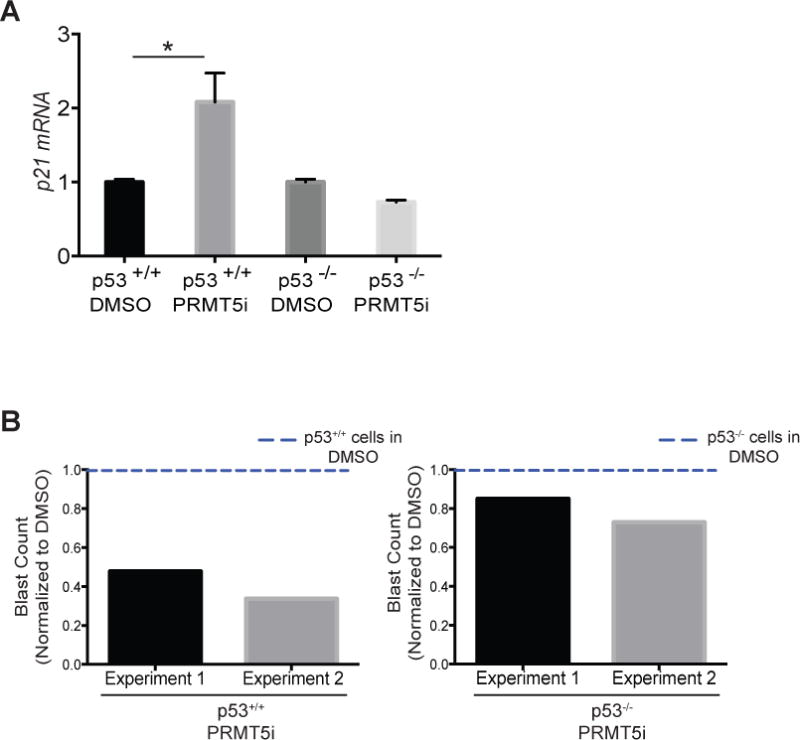

CDKN1a is a well-known target of p53 and PRMT5 has been shown to negatively regulate p53 function (17, 20, 42–44). We did not detect alterations in Trp53 mRNA (Supplementary Figure 7A) or protein levels upon EPZ015666 treatment (Supplementary Figure 7B), thus PRMT5-mediated repression of CDKN1a expression is not due to decreased Trp53 mRNA or protein levels. We next measured the levels of CDKN1a in MLL-fusion p53-deficient cells in the presence or absence of EPZ015666. Although in WT cells we could readily detect an increase in CDKN1a mRNA levels upon PRMT5 inhibition, the levels of CDKN1a remained the same in p53-deficient leukemia cells (Figure 7A). Moreover, the p53-deficient cells were refractory to EPZ015666-induced differentiation (Figure 7B), confirming that the block in differentiation upon PRMT5 inhibition is dependent on re-activation of CDKN1a and this is dependent on p53 activity. These data are in agreement with previous reports showing that PRMT5 negatively regulates p53 function (17, 20). Taken together, these data show that the effects of PRMT5 inhibition in MLL-leukemia cells are dependent on p53 activity and the transcriptional regulation of its target CDKN1a.

Figure 7. p53 is required for CDKN1a up regulation and blast differentiation upon PRMT5 inhibition.

A) mRNA levels of CDKN1a detected by qRT-PCR in p53+/+ and p53-/- MLL-AF9 leukemia cells treated with EPZ015666 (PRMT5i) for three days. B) p53+/+ and p53-/- MLL-AF9 leukemia cells were treated with 5μM EPZ015666 for four days and the frequency of blasts was determined and normalized to DMSO treated cells in independent experiments. We counted the number of blasts in May-Grünwald/Giemsa stained MLL-ENL/NRasG12D cells (in cytospin slides as in Figure 4A) by microscopy. For each experimental condition we counted the number of blasts per 100 cells in three different fields of the cytospin slides. The bar graphs show the blast counts in PRMT5i-treated cells normalized to DMSO- treated cells (blue lines). * p<0.05.

Discussion

Arginine methylation is becoming increasingly appreciated as an important regulator of cellular processes affecting cell growth, proliferation and differentiation (45). In recent years, multiple studies have implicated several members of the PRMT family in cancer (45). Importantly, a study using a MLL-rearranged AML mouse model to perform CRISPR-Cas9 screens identified PRMT1 and PRMT5 as epigenetic vulnerabilities in these leukemias (46). Other studies further revealed the role of PRMT1 in MLL-fusion leukemia and provided evidence for a therapeutic potential of small molecule inhibition of PRMT1 methyltransferase activity (47, 48). PRMT1 is necessary but not sufficient for transformation by MLL fusions and, together with KDM4C, an H3K9 demethylase, regulates the expression of MLL-fusion oncogenic targets (e.g. HoxA9) (48).

We have recently described the effects of conditional deletion of PRMT5 in mouse hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells and characterized the role of PRMT5 in normal hematopoiesis (23). These studies show that PRMT5 is essential to sustain adult hematopoiesis, as deletion of PRMT5 impairs steady state hematopoiesis, colony-forming capacity and bone marrow reconstitution. However, similar studies were not performed in the context of leukemia. We now show that conditional genetic deletion of PRMT5 or small molecule inhibition of PRMT5 activity with the small molecule inhibitor EPZ 015666 impair leukemia development in mouse models of MLL-rearranged AML. Our studies establish an important role for PRMT5 in enforcing the differentiation block characteristic of MLL-fusion leukemias. We found that this differentiation block imposed by PRMT5 is dependent on the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 and that PRMT5 inhibition in leukemia cells causes and up regulation of the gene encoding p21 (CDKN1a). We find that PRMT5 mediates chromatin modifications associated with transcriptional silencing of the CDKN1a locus. Moreover, we also find that differentiation of MLL-rearranged cells and up regulation of CDKN1a upon PRMT5 inhibition require p53 activity. The epigenetic silencing of CDKN1a by PRMT5-dependent H4R3me2 activity and the p53 dependency are not mutually exclusive. Rather, our data lead us to suggest that both mechanisms act in MLL-rearranged leukemia cells to enforce the differentiation block by repressing CDKN1a. Importantly, although PRMT5 inhibition leads to de-repression of CDKN1a, it does not affect the expression of MLL-fusion direct oncogenic targets, contrary to PRMT1 (48).

Several small molecule inhibitors have been developed to target the epigenetic machinery coopted by MLL-fusions (49–52) and some of these therapies are promising and currently being evaluated in clinical trials, for example small-molecule inhibitors of the histone methyltransferase DOT1L (49). Many of these epigenetic targets are required for the expression of MLL-fusion target genes. Since we found that PRMT5, however, enforces the differentiation block of MLL-fusion cells by an alternative mechanism, as PRMT5 inhibition did not affect the expression of MLL-fusion targets (Figure 4F), our studies suggest that combining PRMT5 inhibitors with other targeted drugs may have promising therapeutic applications.

In summary, we found an important role for PRMT5 in enforcing the differentiation block of MLL-rearranged leukemias trough transcriptional silencing of CDKN1a. In addition, our studies pave the way for the use of PRMT5 small molecule inhibitors in a clinical setting, as single agents or in combination with drugs that abrogate the transcription of MLL-fusion direct targets.

Supplementary Material

Table 1.

List of the 50 most significantly upregulated genes upon PRMT5 inhibition in MLL-fusion leukemia cells

| Locus | Gene | Fold increase | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| chr7:139978932-139992562 | Adam8 | 3.944602903 | 6.31E-242 |

| chr6:65590398-65634040 | Tnip3 | 5.048183803 | 9.59E-190 |

| chr19:21391307-21472661 | Gda | 3.915242362 | 1.67E-142 |

| chr9:47530352-47853385 | Cadm1 | 3.236602429 | 7.22E-141 |

| chr5:104435111-104441053 | Spp1 | 3.975551706 | 1.74E-130 |

| chr8:75093618-75100593 | Hmox1 | 3.126440228 | 3.68E-126 |

| chr1:135766085-135769134 | Phlda3 | 3.892319263 | 1.58E-110 |

| chr14:47373860-47386167 | Lgals3 | 3.126243929 | 5.45E-110 |

| chr10:120361275-120476935 | Hmga2 | 3.144494283 | 2.39E-109 |

| chr1:131688695-131713464 | Rab7b | 2.900542866 | 2.40E-109 |

| chr11:82035577-82037452 | Ccl2 | 4.62635232 | 1.10E-97 |

| chr1:74375203-74386051 | Slc11a1 | 3.887700314 | 1.61E-97 |

| chr4:141301221-141329384 | Epha2 | 3.116104894 | 9.57E-95 |

| chr3:90612894-90614414 | S100a6 | 3.227902555 | 1.21E-87 |

| chr4:11156441-11174377 | Trp53inp1 | 2.280236252 | 1.15E-85 |

| chr6:123262107-123275268 | Clec4d | 2.580013533 | 6.28E-83 |

| chr13:110395044-110400843 | Plk2 | 3.864400996 | 7.53E-82 |

| chr17:29090986-29100722 | Cdkn1a | 2.297297778 | 4.48E-79 |

| chr1:84036293-84284645 | Pid1 | 3.026303363 | 1.36E-78 |

| chr7:24462500-24475873 | Plaur | 2.608862789 | 7.33E-77 |

| chr3:105704599-105720842 | Fam212b | 3.538644455 | 1.01E-76 |

| chr5:138755081-138810063 | Fam20c | 4.574548183 | 1.18E-72 |

| chr6:135362931-135383173 | Emp1 | 3.187744673 | 7.33E-72 |

| chr11:40748552-40755286 | Ccng1 | 1.883285094 | 1.40E-70 |

| chr7:128062640-128118491 | Itgam | 1.920811588 | 2.34E-70 |

| chr10:117688875-117710758 | Mdm2 | 1.90221944 | 8.09E-68 |

| chr16:52248996-52452997 | Alcam | 2.01534872 | 3.30E-64 |

| chrX:106143275-106160493 | Tlr13 | 2.149506253 | 3.13E-62 |

| chr2:166073899-166155683 | Sulf2 | 5.042872877 | 9.81E-61 |

| chr1:167001417-167091302 | Fam78b | 2.831191233 | 2.54E-60 |

| chr12:52516077-52567851 | Arhgap5 | 2.305011794 | 3.66E-60 |

| chr1:182467259-182517483 | Capn2 | 2.071468705 | 1.86E-58 |

| chr19:20373434-20390671 | Anxa1 | 2.297104001 | 4.14E-57 |

| chr6:89316314-89362613 | Plxna1 | 3.271907501 | 3.55E-56 |

| chr2:164948219-164955849 | Mmp9 | 4.946432833 | 2.80E-55 |

| chr4:86656565-86670059 | Plin2 | 1.75166401 | 2.88E-55 |

| chr16:44820728-44839150 | Cd200r4 | 3.141009351 | 5.46E-55 |

| chr10:19847917-19851459 | Slc35d3 | 2.395689589 | 1.16E-53 |

| chr18:9707648-9877995 | Colec12 | 1.75604146 | 1.90E-52 |

| chr18:61105572-61131139 | Csf1r | 1.66313631 | 7.52E-52 |

| chr2:118111922-118127133 | Thbs1 | 3.006075338 | 3.46E-50 |

| chr6:40574898-40585805 | Clec5a | 3.388033971 | 9.56E-48 |

| chr15:6299789-6440709 | Dab2 | 2.148398661 | 1.23E-47 |

| chr2:24336860-24351491 | Il1rn | 3.56263109 | 2.64E-47 |

| chr5:137821952-137836278 | Pilra | 3.039277665 | 4.56E-46 |

| chr3:79885930-79946278 | Fam198b | 2.966075536 | 1.78E-45 |

| chr3:32334794-32365665 | Zmat3 | 2.003069361 | 2.55E-45 |

| chr9:54604997-54661885 | Acsbg1 | 4.462174155 | 5.06E-45 |

| chr7:45457944-45459886 | Ftl1 | 1.434957336 | 2.50E-44 |

| chr2:28193093-28230736 | Olfm1 | 2.387800044 | 3.75E-44 |

Table 2.

List of the 50 most significantly downregulated genes upon PRMT5 inhibition in MLL-fusion leukemia cells

| Locus | Gene | Fold decrease | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| chr17:35861318-35865400 | Nrm | −2.396304944 | 1.45E-65 |

| chr10:79781474-79788985 | Prss57 | −4.918450203 | 2.43E-41 |

| chr5:150522621-150570146 | Brca2 | −1.889662433 | 8.32E-40 |

| chr11:120635712-120643670 | Pycr1 | −2.583403013 | 4.87E-37 |

| chr17:34182099-34187330 | Psmb9 | −1.510779495 | 1.30E-35 |

| chr8:83900098-83941954 | Adgrl1 | −2.450309657 | 1.85E-35 |

| chr9:107587718-107593038 | Ifrd2 | −1.456177293 | 2.71E-35 |

| chr2:148404471-148408188 | Thbd | −1.38232309 | 4.70E-34 |

| chr2:29245116-29252993 | 6530402F18Rik | −1.809063243 | 7.79E-33 |

| chr11:115268025-115276969 | Fdxr | −1.779572846 | 1.01E-32 |

| chr7:30727701-30729534 | Tmem147 | −1.427247385 | 1.39E-31 |

| chr17:25875500-25877163 | 0610011F06Rik | −1.991285265 | 2.58E-31 |

| chr11:102189699-102194081 | G6pc3 | −1.857724226 | 6.99E-30 |

| chr15:79527696-79546741 | Ddx17 | −1.346434785 | 8.29E-29 |

| chr10:3973075-4167081 | Mthfd1l | −1.245975037 | 1.07E-28 |

| chr6:142350342-142387087 | Recql | −1.342557918 | 4.87E-28 |

| chr13:22002176-22009741 | Prss16 | −1.3452956 | 1.62E-27 |

| chr11:72961169-72993043 | Atp2a3 | −1.119737724 | 7.66E-27 |

| chr9:96196275-96323646 | Tfdp2 | −1.357695181 | 3.38E-26 |

| chr5:123973628-124003215 | Hip1r | −1.600463921 | 4.27E-26 |

| chr17:56009201-56016783 | Mpnd | −1.436005993 | 5.86E-26 |

| chr1:106720410-106759742 | Kdsr | −1.486231814 | 1.69E-25 |

| chr5:122209729-122242297 | Hvcn1 | −1.636990647 | 2.16E-25 |

| chr7:143005046-143019485 | Tspan32 | −1.43012066 | 2.93E-25 |

| chr2:32236683-32255005 | Pomt1 | −1.488716061 | 3.42E-25 |

| chr11:60417145-60445277 | Gid4 | −1.285732598 | 4.40E-25 |

| chr10:77032739-77050432 | Slc19a1 | −1.452729089 | 5.55E-25 |

| chr15:102176998-102189043 | Csad | −2.24698371 | 7.52E-25 |

| chr7:44532744-44548815 | Pold1 | −1.216038222 | 7.73E-25 |

| chr8:84956610-84966011 | Rnaseh2a | −1.290515313 | 1.35E-24 |

| chr17:25790500-25792394 | Fam173a | −1.406598015 | 3.34E-24 |

| chr5:147330742-147400489 | Flt3 | −1.125780537 | 4.23E-24 |

| chr15:61985341-61990361 | Myc | −1.067640492 | 2.52E-23 |

| chr14:30009000-30040466 | Chdh | −1.422381009 | 2.89E-23 |

| chr11:72498156-72550246 | Spns3 | −1.651153216 | 4.55E-23 |

| chr10:127677065-127701047 | Tmem194 | −1.358518022 | 7.35E-23 |

| chr13:56173703-56178885 | Tifab | −1.25333091 | 3.32E-22 |

| chr7:80094847-80115350 | Idh2 | −1.032632752 | 4.51E-22 |

| chr17:34996724-35000746 | D17H6S56E-5 | −1.088295771 | 6.81E-22 |

| chrX:51113494-51205832 | Mbnl3 | −1.31611171 | 7.13E-22 |

| chr17:34026033-34028055 | H2-Ke6 | −1.597809138 | 7.31E-22 |

| chr2:29869494-29882840 | Cercam | −1.494465734 | 8.83E-22 |

| chr19:7056768-7198062 | Macrod1 | −2.82427387 | 1.14E-21 |

| chr17:35512735-35516824 | Tcf19 | −1.355893663 | 2.37E-21 |

| chr7:44489938-44496513 | Emc10 | −1.133114341 | 3.28E-21 |

| chr14:55478758-55490340 | Dhrs4 | −1.638149023 | 3.83E-21 |

| chr7:106595549-106644645 | Gm1966 | −1.016607554 | 4.91E-21 |

| chr7:127296260-127335137 | Itgal | −1.088711782 | 2.45E-20 |

| chr3:157534397-157548339 | Zranb2 | −0.995216161 | 4.94E-20 |

| chr19:40222239-40271616 | Pdlim1 | −1.299536012 | 6.91E-20 |

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of the M.A. Santos’s laboratory; P. Jones for discussions, P. Whitney for flow cytometry; C. Perez for imaging; P. Huskey and all members of the Smithville animal facility for animal care; L. Coletta for RNA-seq and J. Zuber for MLL-ENL/NrasG12D cells. RASF-Smithville, Laboratory Animal Genetic Services, RHPI - Pathology and Imaging Services were supported by NIH CA16672; the Science Park NGS core by CPRIT RP120348. This work was supported by an American Cancer Society Institutional Research Grant to F.L. and a CPRIT Recruitment of First-time Tenure-Track Faculty Award (RR150039), a Sidney Kimmel Foundation - Kimmel Scholar Award (SKF-16-061) and a NCI Cancer Center Support Grant (CCSG) New Faculty Award to M.A.S.

Laboratory Animal Genetic Services and Pathology and Imaging Services were supported by NIH CA16672; the Science Park NGS core by CPRIT RP120348. This work was also supported by an American Cancer Society Institutional Research Grant to F.L. and a CPRIT Recruitment of First-time Tenure-Track Faculty Award (RR150039), a Sidney Kimmel Foundation - Kimmel Scholar Award (SKF-16-061) and a NCI Cancer Center Support Grant (CCSG) New Faculty Award to M.A.S.

Footnotes

Author contributions

S.K., F.L., K.V., V. G., M.T.B., S.D.N. and M.A.S participated in the study design. S.K., F.L., G.G., P.D. and L.N. performed mouse breeding, HSC analysis, transplantation and leukemia experiments, and analyzed data. K.V. led all the ChIP experiments and analyzed data. K.L., Y.Z. and Y.L performed computational experiments. S.K., F.L., S. D.N. and M.A.S wrote the manuscript and all authors reviewed it. M.A.S. supervised the project.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Krivtsov AV, Armstrong SA. MLL translocations, histone modifications and leukaemia stem-cell development. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7(11):823–33. doi: 10.1038/nrc2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Somervaille TC, Cleary ML. Grist for the MLL: how do MLL oncogenic fusion proteins generate leukemia stem cells? Int J Hematol. 2010;91(5):735–41. doi: 10.1007/s12185-010-0579-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jude CD, Climer L, Xu D, Artinger E, Fisher JK, Ernst P. Unique and independent roles for MLL in adult hematopoietic stem cells and progenitors. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1(3):324–37. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernt KM, Armstrong SA. Targeting epigenetic programs in MLL-rearranged leukemias. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2011;2011:354–60. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2011.1.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santos MA, Faryabi RB, Ergen AV, Day AM, Malhowski A, Canela A, et al. DNA-damage-induced differentiation of leukaemic cells as an anti-cancer barrier. Nature. 2014;514(7520):107–11. doi: 10.1038/nature13483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bedford MT, Richard S. Arginine methylation an emerging regulator of protein function. Mol Cell. 2005;18(3):263–72. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pal S, Vishwanath SN, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Sif S. Human SWI/SNF-associated PRMT5 methylates histone H3 arginine 8 and negatively regulates expression of ST7 and NM23 tumor suppressor genes. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(21):9630–45. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.21.9630-9645.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao Q, Rank G, Tan YT, Li H, Moritz RL, Simpson RJ, et al. PRMT5-mediated methylation of histone H4R3 recruits DNMT3A, coupling histone and DNA methylation in gene silencing. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16(3):304–11. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen H, Lorton B, Gupta V, Shechter D. A TGFbeta-PRMT5-MEP50 axis regulates cancer cell invasion through histone H3 and H4 arginine methylation coupled transcriptional activation and repression. Oncogene. 2016 doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pal S, Baiocchi RA, Byrd JC, Grever MR, Jacob ST, Sif S. Low levels of miR-92b/96 induce PRMT5 translation and H3R8/H4R3 methylation in mantle cell lymphoma. EMBO J. 2007;26(15):3558–69. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aggarwal P, Vaites LP, Kim JK, Mellert H, Gurung B, Nakagawa H, et al. Nuclear cyclin D1/CDK4 kinase regulates CUL4 expression and triggers neoplastic growth via activation of the PRMT5 methyltransferase. Cancer Cell. 2010;18(4):329–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirino Y, Kim N, de Planell-Saguer M, Khandros E, Chiorean S, Klein PS, et al. Arginine methylation of Piwi proteins catalysed by dPRMT5 is required for Ago3 and Aub stability. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11(5):652–8. doi: 10.1038/ncb1872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vagin VV, Wohlschlegel J, Qu J, Jonsson Z, Huang X, Chuma S, et al. Proteomic analysis of murine Piwi proteins reveals a role for arginine methylation in specifying interaction with Tudor family members. Genes Dev. 2009;23(15):1749–62. doi: 10.1101/gad.1814809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wei H, Wang B, Miyagi M, She Y, Gopalan B, Huang DB, et al. PRMT5 dimethylates R30 of the p65 subunit to activate NF-kappaB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(33):13516–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311784110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsu JM, Chen CT, Chou CK, Kuo HP, Li LY, Lin CY, et al. Crosstalk between Arg 1175 methylation and Tyr 1173 phosphorylation negatively modulates EGFR-mediated ERK activation. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13(2):174–81. doi: 10.1038/ncb2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zheng S, Moehlenbrink J, Lu YC, Zalmas LP, Sagum CA, Carr S, et al. Arginine methylation-dependent reader-writer interplay governs growth control by E2F-1. Mol Cell. 2013;52(1):37–51. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jansson M, Durant ST, Cho EC, Sheahan S, Edelmann M, Kessler B, et al. Arginine methylation regulates the p53 response. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10(12):1431–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang L, Pal S, Sif S. Protein arginine methyltransferase 5 suppresses the transcription of the RB family of tumor suppressors in leukemia and lymphoma cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28(20):6262–77. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00923-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chung J, Karkhanis V, Tae S, Yan F, Smith P, Ayers LW, et al. Protein arginine methyltransferase 5 (PRMT5) inhibition induces lymphoma cell death through reactivation of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor pathway and polycomb repressor complex 2 (PRC2) silencing. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(49):35534–47. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.510669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Y, Chitnis N, Nakagawa H, Kita Y, Natsugoe S, Yang Y, et al. PRMT5 is required for lymphomagenesis triggered by multiple oncogenic drivers. Cancer Discov. 2015;5(3):288–303. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chan-Penebre E, Kuplast KG, Majer CR, Boriack-Sjodin PA, Wigle TJ, Johnston LD, et al. A selective inhibitor of PRMT5 with in vivo and in vitro potency in MCL models. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11(6):432–7. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jin Y, Zhou J, Xu F, Jin B, Cui L, Wang Y, et al. Targeting methyltransferase PRMT5 eliminates leukemia stem cells in chronic myelogenous leukemia. J Clin Invest. 2016;126(10):3961–80. doi: 10.1172/JCI85239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu F, Cheng G, Hamard PJ, Greenblatt S, Wang L, Man N, et al. Arginine methyltransferase PRMT5 is essential for sustaining normal adult hematopoiesis. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(9):3532–44. doi: 10.1172/JCI81749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim D, Pertea G, Trapnell C, Pimentel H, Kelley R, Salzberg SL. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 2013;14(4):R36. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-4-r36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W. HTSeq–a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(2):166–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 2010;11(10):R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(43):15545–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tee WW, Pardo M, Theunissen TW, Yu L, Choudhary JS, Hajkova P, et al. Prmt5 is essential for early mouse development and acts in the cytoplasm to maintain ES cell pluripotency. Genes Dev. 2010;24(24):2772–7. doi: 10.1101/gad.606110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krivtsov AV, Twomey D, Feng Z, Stubbs MC, Wang Y, Faber J, et al. Transformation from committed progenitor to leukaemia stem cell initiated by MLL-AF9. Nature. 2006;442(7104):818–22. doi: 10.1038/nature04980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neubauer A, Maharry K, Mrozek K, Thiede C, Marcucci G, Paschka P, et al. Patients with acute myeloid leukemia and RAS mutations benefit most from postremission high-dose cytarabine: a Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(28):4603–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.0418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pardee TS, Zuber J, Lowe SW. Flt3-ITD alters chemotherapy response in vitro and in vivo in a p53-dependent manner. Exp Hematol. 2011;39(4):473–85 e4. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2011.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schoch C, Schnittger S, Klaus M, Kern W, Hiddemann W, Haferlach T. AML with 11q23/MLL abnormalities as defined by the WHO classification: incidence, partner chromosomes, FAB subtype, age distribution, and prognostic impact in an unselected series of 1897 cytogenetically analyzed AML cases. Blood. 2003;102(7):2395–402. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zuber J, Radtke I, Pardee TS, Zhao Z, Rappaport AR, Luo W, et al. Mouse models of human AML accurately predict chemotherapy response. Genes Dev. 2009;23(7):877–89. doi: 10.1101/gad.1771409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zuber J, Shi J, Wang E, Rappaport AR, Herrmann H, Sison EA, et al. RNAi screen identifies Brd4 as a therapeutic target in acute myeloid leukaemia. Nature. 2011;478(7370):524–8. doi: 10.1038/nature10334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koh CM, Bezzi M, Low DH, Ang WX, Teo SX, Gay FP, et al. MYC regulates the core pre-mRNA splicing machinery as an essential step in lymphomagenesis. Nature. 2015;523(7558):96–100. doi: 10.1038/nature14351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Somervaille TC, Matheny CJ, Spencer GJ, Iwasaki M, Rinn JL, Witten DM, et al. Hierarchical maintenance of MLL myeloid leukemia stem cells employs a transcriptional program shared with embryonic rather than adult stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4(2):129–40. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bernt KM, Zhu N, Sinha AU, Vempati S, Faber J, Krivtsov AV, et al. MLL-rearranged leukemia is dependent on aberrant H3K79 methylation by DOT1L. Cancer Cell. 2011;20(1):66–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wong P, Iwasaki M, Somervaille TC, Ficara F, Carico C, Arnold C, et al. The miR-17-92 microRNA polycistron regulates MLL leukemia stem cell potential by modulating p21 expression. Cancer Res. 2010;70(9):3833–42. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang T, Gunther S, Looso M, Kunne C, Kruger M, Kim J, et al. Prmt5 is a regulator of muscle stem cell expansion in adult mice. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7140. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saramaki A, Banwell CM, Campbell MJ, Carlberg C. Regulation of the human p21(waf1/cip1) gene promoter via multiple binding sites for p53 and the vitamin D3 receptor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(2):543–54. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Siatecka M, Lohmann F, Bao S, Bieker JJ. EKLF directly activates the p21WAF1/CIP1 gene by proximal promoter and novel intronic regulatory regions during erythroid differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30(11):2811–22. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01016-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Andreu-Perez P, Esteve-Puig R, de Torre-Minguela C, Lopez-Fauqued M, Bech-Serra JJ, Tenbaum S, et al. Protein arginine methyltransferase 5 regulates ERK1/2 signal transduction amplitude and cell fate through CRAF. Sci Signal. 2011;4(190):ra58. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim S, Gunesdogan U, Zylicz JJ, Hackett JA, Cougot D, Bao S, et al. PRMT5 protects genomic integrity during global DNA demethylation in primordial germ cells and preimplantation embryos. Mol Cell. 2014;56(4):564–79. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scoumanne A, Zhang J, Chen X. PRMT5 is required for cell-cycle progression and p53 tumor suppressor function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(15):4965–76. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang Y, Bedford MT. Protein arginine methyltransferases and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13(1):37–50. doi: 10.1038/nrc3409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shi J, Wang E, Milazzo JP, Wang Z, Kinney JB, Vakoc CR. Discovery of cancer drug targets by CRISPR-Cas9 screening of protein domains. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(6):661–7. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cheung N, Chan LC, Thompson A, Cleary ML, So CW. Protein arginine-methyltransferase-dependent oncogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9(10):1208–15. doi: 10.1038/ncb1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cheung N, Fung TK, Zeisig BB, Holmes K, Rane JK, Mowen KA, et al. Targeting Aberrant Epigenetic Networks Mediated by PRMT1 and KDM4C in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2016;29(1):32–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Daigle SR, Olhava EJ, Therkelsen CA, Majer CR, Sneeringer CJ, Song J, et al. Selective killing of mixed lineage leukemia cells by a potent small-molecule DOT1L inhibitor. Cancer Cell. 2011;20(1):53–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dawson MA, Prinjha RK, Dittmann A, Giotopoulos G, Bantscheff M, Chan WI, et al. Inhibition of BET recruitment to chromatin as an effective treatment for MLL-fusion leukaemia. Nature. 2011;478(7370):529–33. doi: 10.1038/nature10509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grembecka J, He S, Shi A, Purohit T, Muntean AG, Sorenson RJ, et al. Menin-MLL inhibitors reverse oncogenic activity of MLL fusion proteins in leukemia. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8(3):277–84. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Harris WJ, Huang X, Lynch JT, Spencer GJ, Hitchin JR, Li Y, et al. The histone demethylase KDM1A sustains the oncogenic potential of MLL-AF9 leukemia stem cells. Cancer Cell. 2012;21(4):473–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.