Abstract

Objective:

Development of a core outcome set (COS) for clinical effectiveness trials in esophageal cancer resection surgery.

Background:

Inconsistency and heterogeneity in outcome reporting after esophageal cancer resection surgery hampers comparison of trial results and undermines evidence synthesis. COSs provide an evidence-based approach to these challenges.

Methods:

A long list of clinical and patient-reported outcomes was identified and categorized into outcome domains. Domains were operationalized into a questionnaire and patients and health professionals rated the importance of items from 1 (not important) to 9 (extremely important) in 2 Delphi survey rounds. Retained items were discussed at a consensus meeting and a final COS proposed. Professionals were surveyed to request endorsement of the COS.

Results:

A total of 68 outcome domains were identified and operationalized into a questionnaire; 116 (91%) of consenting patients and 72 (77%) of health professionals completed round 1. Round 2 response rates remained high (87% patients, 93% professionals). Rounds 1 and 2 prioritized 43 and 19 items, respectively. Retained items were discussed at a patient consensus meeting and a final 10-item COS proposed, endorsed by 61/67 (91%) professionals and including: overall survival; in-hospital mortality; inoperability; need for another operation; respiratory complications; conduit necrosis and anastomotic leak; severe nutritional problems; ability to eat/drink; problems with acid indigestion or heartburn; and overall quality of life.

Conclusions:

The COS is recommended for all pragmatic clinical effectiveness trials in esophageal cancer resection surgery. Further work is needed to delineate the definitions and parameters and explore best methods for measuring the individual outcomes.

Keywords: Delphi technique, esophageal neoplasms, operative, outcome assessment, randomized controlled trial, surgical procedures

Clinical effectiveness trials are designed to evaluate the performance of an intervention under pragmatic or real-world conditions, rather than the ideal and controlled circumstances often observed in efficacy trials.1 The results of clinical effectiveness trials may therefore be more readily applied to everyday practice and are likely to influence clinical decision making and health policy.2,3 Integral to the design and applicability of effectiveness trials is the selection, measurement and reporting of outcomes, which are required to evaluate clinical benefit from the view point of the patient and health provider in addition to assessing risks and harms (often the focus of the surgeon).3 Systematic reviews have shown, however, that there are often inconsistencies in the way in which outcomes are defined, selected, measured, and reported in trials of esophageal cancer surgery.4,5 This makes the robust evaluation of esophageal cancer surgery difficult.4

Outcomes that may be relevant to effectiveness trials of esophageal cancer surgery include long-term morbidity, disease recurrence, symptom alleviation and quality of life.6,7 However, the heterogeneity of outcomes measured and reported across such trials hampers comparison of centers and trial results, thereby compromising evidence synthesis.8 It also means that outcome reporting bias (the selective reporting of some outcomes but not others) may occur.8 Core outcome sets (COSs), which define a minimum set of key outcomes to be measured and reported in all trials of specific conditions, provide an evidence-based approach to standardize outcome selection and reporting.9,10 Their development and application has the potential to increase the quality of usable data generated by clinical effectiveness trials, thereby reducing research waste.11 These sets of standardized outcomes do not preclude the measurement of additional outcomes of specific interest to investigators or studies. Instead, they outline the core set of outcomes that should be routinely measured and reported as a minimum.10

A COS for effectiveness trials of esophageal cancer surgery that includes both clinical and patient-centered outcomes has the potential to reduce reporting bias, increase homogeneity in outcome reporting and improve the value of research in this area.8,11–13 This article describes the development of a COS for esophageal cancer resection surgery.

METHODS

Details of the COS development process are reported in accordance with recommendations of the Core Outcome Set-STAndards for Reporting (COS-STAR) checklist.14 The COS was developed in 3 phases: (i) Phase 1—identification of a ‘long list’ of outcomes and development of survey questionnaire; (ii) Phase 2—prioritization of outcomes using Delphi survey; and (iii) Phase 3—consensus meeting to finalize COS.

Phase 1: Identification of Long List of Outcomes and Development of Survey Questionnaire

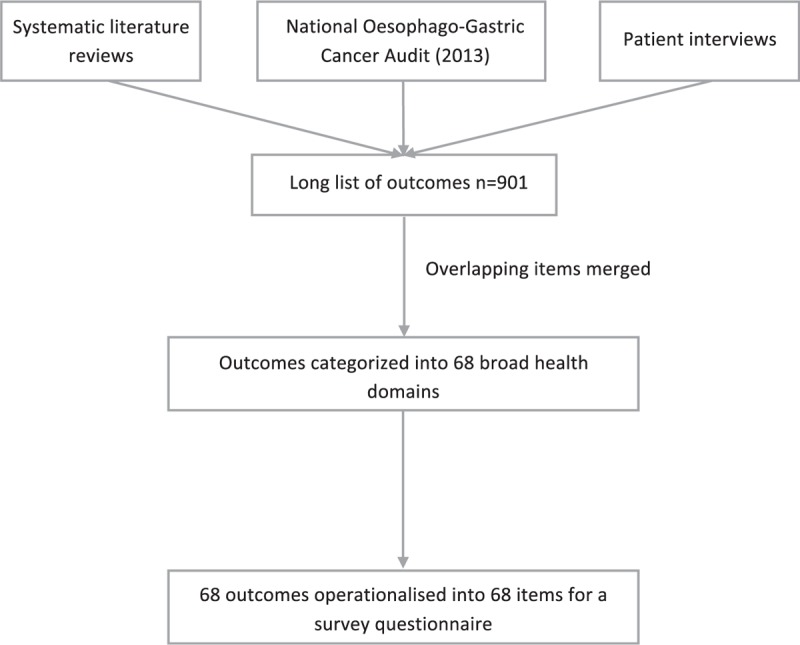

The identification of an exhaustive long list of outcomes of esophageal cancer resection surgery has been previously reported4,5,15,16 and included systematic reviews, a national register/audit of outcomes and patient interviews (Fig. 1). Overlapping outcomes were merged and outcomes categorized independently by 2 study researchers into broader health domains, defined as areas of health within the same theme (eg, 30- and 90-day mortality were grouped into a “mortality” domain) and, in the absence of established definitions,4 agreed after discussion between the study team. A patient representative assisted in the process of categorizing the patient-reported outcomes.5 Domains were formulated as items for a survey questionnaire. Each item was written in lay language with the clinical terminology included in parentheses. The draft survey was piloted by four lay people and one patient representative to examine face validity, comprehension, and acceptability.

FIGURE 1.

Data sources and steps involved in the development of the core outcome set.

Phase 2: Prioritization of Outcomes

Stakeholders

Professionals from relevant disciplines and clinical backgrounds (esophagogastric surgeons and clinical nurse specialists) were identified from the membership of the Association of Upper Gastro Intestinal Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland. Consecutive patients who had undergone primary esophagectomy or esophagectomy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy between 1 month and 5 years previously (January 2015 to January 2009) were sampled in descending chronological order from lists of patients at 2 United Kingdom hospital trusts with which the research team was collaborating (University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust and Plymouth Hospitals NHS Trust). Professionals and patients were asked to complete 2 rounds of questionnaires.

Round 1

Professionals were contacted by email about the study and notified that they would receive the first questionnaire through the post with a prepaid return envelope. One postal reminder was sent if necessary. Patients were posted an invitation letter and information leaflet, asking them to return a completed consent form. Patients who returned consent were posted the round 1 survey questionnaire with a pre-paid return envelope. Patients who did not return their consent forms within four weeks were sent a reminder (Bristol patients only). Respondents were asked to rate the importance of retaining each item in the COS on a 9-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not important) to 9 (extremely important).17–20 The round 1 item scores were summarized and items to retain for round 2 identified using prespecified criteria (see analyses section). The team reviewed retained items to see if any could be further merged because of overlapping content. The participants were not made aware of the prespecified cutoff criteria when completing the questionnaire.

Round 2

All participants who returned a round 1 questionnaire and were still contactable were mailed a round 2 questionnaire with a prepaid return envelope. The round 2 questionnaire contained all items retained from round 1. All participants received anonymized feedback for each item, from each stakeholder group (patients, surgeons, nurses).21 Feedback consisted of median round 1 scores calculated separately for each stakeholder group. Participants were asked to rerate the items’ importance on the same 9-point scale. In a further attempt to encourage prioritization, the survey instructions in round 2 requested that respondents prioritize and rate highly only the items that they believed to be essential, intended to be “about 10 items.” Round 2 questionnaire responses were summarized to identify a list of items that should be retained and discussed at the consensus meetings using pre-specified criteria.

Phase 3: Consensus Meetings

All participants who responded to the round 2 questionnaire were invited to a consensus meeting where the results of the Delphi survey were summarized. At the meeting, participants were asked to vote on the list of items carried forward from round 2 using an anonymized system (TurningPoint software22) with 3 keypad options: “in” (the item should be included in the COS), “out” (the item should not be included in the COS) or “unsure.” Items for which consensus was not reached (see “Statistical analyses” section) were discussed further and additional voting conducted until the final list of items was agreed.

Statistical Analyses

Items in round 1 were categorized as “essential” and eligible to be retained for round 2 if they met the following cutoff criteria defined a priori: (i) rated 7–9 by ≥70% and 1–3 by < 15% of either patients or professionals (surgeons and nurses combined). The same criteria were specified for identifying items to retain from round 2 for the consensus meetings. In both rounds, items were discarded if they did not meet these criteria. There are no universally agreed consensus criteria in Delphi surveys and examples vary widely; the criteria used here follow published recommendations.9

Prespecified criteria for the consensus meetings were that items voted “in” by ≥70% of participants would be included in the COS. Items voted “in” by <60% and “out” by ≥15% of participants would be discarded. Any other items were discussed further and revoted on until consensus was reached.

Sample Size

There are currently no agreed sample size guidelines for the number of participants necessary for consensus methods when developing a COS,17 though the numbers of participants sampled for this study is in keeping with that of similar studies.23,24 An opportunistic approach was used with the intention of recruiting 200 patients with experience of esophageal cancer resection surgery across two different hospital trusts and a range of 100 professionals involved in the care of esophageal cancer surgery patients. All patients who responded to the round 2 survey were invited to the consensus meeting to encompass a range of patients’ experiences.

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the South-West Frenchay Research Ethics Committee (12/SW/0161).

RESULTS

Phase 1: Identification of Long List of Outcomes and Development of Survey Questionnaire

The systematic reviews, audit, and patient interviews4,5,15,16 identified 901 outcomes, which were categorized into 68 health domains and 68 items for the survey (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Domains Identified From Initial Long List (Survey Questionnaire Items)

| Broad Health Domain | Domain |

| Quality of life after discharge from hospital (n = 38 items) | |

| Activities of daily living and work/employment | 1 Able to carry out usual activities |

| 2 Able to participate/enjoy physical activities | |

| Eating and drinking | 3 Able to eat/drink more easily (dysphagia) |

| 4 Able to swallow without pain (odynophagia) | |

| 5 Able to enjoy healthy/balanced eating pattern | |

| 6 Problems with acid indigestion/heartburn including at night (reflux) | |

| 7 Problems eating socially | |

| 8 Problems with regurgitation and/or vomiting | |

| 9 Belching, bloating or gas (flatulence) | |

| 10 Feeling out of breath/difficulties breathing (dyspnea) | |

| 11 Problems choking when eating/drinking | |

| 12 Problems with appetite loss | |

| 13 Problems with sense of taste | |

| 14 Sudden dizziness, sweating and/or feeling drained after eating (dumping) | |

| Physical health | 15 Problems with feeling sick (nausea) |

| 16 Problems with diarrhoea, including frequent bowel movements | |

| 17 Having good general health | |

| 18 Problems with general pain/discomfort | |

| 19 Problems with weak voice/hoarseness | |

| 20 Problems with constipation | |

| 21 Problems with coughing | |

| 22 Problems with a dry mouth | |

| 23 Problems with sleeping | |

| 24 Problems with tiredness (fatigue) | |

| Physical appearance | 25 Problems with weight |

| 26 Feeling in control of weight and appearance | |

| 27 Feeling satisfied/confident with one's body | |

| 28 Problems with hair loss | |

| Social life and relationships | 29 Interested in and able to enjoy sex |

| 30 Able to have relationships with friends | |

| 31 Able to have relationships with family members | |

| Mental health | 32 Problems with concentration and memory (cognitive function) |

| 33 Problems with anxiety | |

| 34 Problems with depression | |

| 35 Problems with changes in general mood | |

| Overall health, wellbeing and life | 36 Money worries due to loss of earnings (finances) |

| 37 Overall quality of life | |

| 38 Spiritual or faith issues | |

| Benefits of esophageal cancer surgery (n = 4 items) | |

| Improving problems of esophageal cancer | 39 Improving patient's ability to eat and drink (dysphagia) |

| Survival and controlling cancer | 40 How long a patient will live (overall survival) |

| 41 How long a patient may live free of esophageal cancer (Cancer-specific survival) | |

| 42 The chances that the cancer will come back (recurrence) | |

| In-hospital events (n = 18 items) | |

| Events during surgery | 43 Inoperability |

| 44 Organ injury | |

| 45 Hemorrhage | |

| Post-operative events related to esophagectomy | 46 Chyle/pleural leak |

| 47 Anastomotic leak | |

| 48 Conduit necrosis | |

| 49 Re-insertion of chest/abdominal/stomach drain | |

| 50 Laryngeal nerve palsy | |

| Other postoperative events | 51 Wound infection or dehiscence |

| 52 Cardiac complications | |

| 53 Renal complications | |

| 54 Severe urine infection (septicaemia) | |

| 55 Cerebral complications | |

| 56 Liver failure | |

| 57 Respiratory complications | |

| 58 Blood clots in the legs or lungs (deep vein thrombosis; pulmonary embolism) | |

| 59 Reventilation | |

| 60 Inhospital mortality | |

| Events after discharge (n = 8 items) | |

| Events related to eating and drinking | 61 Esophageal stricture |

| 62 Pyloric dilatation | |

| 63 Total parenteral nutrition | |

| Complications needing reoperation or reintervention | 64 Need for further surgery for a build-up of fluid around the lung (empyema) |

| 65 Need for further stomach surgery due to abdominal hernia | |

| 66 Colonic interposition | |

| 67 Diaphragmatic hernia repair | |

| 68 Need for another operation | |

Phase 2: Prioritization of Outcomes

Stakeholders

A total of 94 professionals [esophagagastric surgeons (n = 72) and clinical nurse specialists (n = 22)] from 38 different United Kingdom hospital trusts and 200 patients from 2 United Kingdom hospital trusts participated in round 1.

Round 1

In this study, 128/200 (64%) patients consented to participate, and 116/128 (91%) patients and 72/94 (77%) health professionals completed the questionnaire. Participants’ demographics are provided in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Demographics of Participants

| Patients | Round 1 SurveyN = 116 | Round 2 SurveyN = 94 | Consensus Meeting N = 20 |

| Center, N (%) | 116 (90.6) | 94 (87.0) | – |

| Bristol | 72 (90.0) | 56 (83.6) | 17 (85.0) |

| Plymouth | 44 (91.7) | 38 (92.6) | 3 (15.0) |

| Male, N (%) | 94 (81.0) | 74 (78.7) | 18 (90) |

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 66.1 (8.1) | 65.9 (7.9) | 65.6 (8.9) |

| Educational background N* (%) | |||

| GCSE (or equivalent) | 37 (33.3) | 31 (34.4) | 6 (30.0) |

| A level (or equivalent) | 19 (17.1) | 15 (16.7) | 5 (25.0) |

| University degree | 6 (5.4) | 5 (5.6) | 1 (5.0) |

| Vocational qualification | 18 (16.2) | 15 (16.7) | 3 (15.0) |

| Higher degree | 2 (1.8) | 2 (2.2) | 1 (5.0) |

| No qualifications | 9 (8.1) | 3 (3.3) | 1 (5.0) |

| Other | 20 (18.0) | 16 (17.8) | 3 (15.0) |

| Marital status†, N (%) | |||

| Single | 9 (7.8) | 7 (7.5) | 1 (5.0) |

| Married | 85 (73.9) | 66 (71.0) | 15 (75.0) |

| Cohabiting | 5 (4.3) | 5 (5.4) | 1 (5.0) |

| Separated | 2 (1.7) | 2 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Divorced | 8 (7.0) | 8 (8.6) | 2 (10.0) |

| Widowed | 6 (5.2) | 5 (5.4) | 1 (5.0) |

| Employment status, N (%) | |||

| Working full time | 18 (15.5) | 14 (14.9) | 5 (25.0) |

| Retired | 76 (65.5) | 61 (64.9) | 11 (55.5) |

| Housewife/husband | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Doing voluntary work | 2 (1.7) | 2 (2.1) | 1 (5.0) |

| Unemployed sickness/disability | 6 (5.2) | 5 (5.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Unemployed and seeking work | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 12 (10.3) | 10 (10.6) | 3 (15.0) |

| Time since surgery, months, mean (SD) | 20.3 (14.9) | 19.8 (15.0) | 17.4 (12.1) |

| Second operation needed†, N (%) | |||

| No | 92 (80) | 74 (79.6) | 12 (66.7) |

| Duration of hospital stay‡, N (%) | |||

| < 14 days | 72 (63.7) | 59 (64.1) | 10 (55.6) |

| 2–3 weeks | 21 (18.6) | 16 (17.4) | 4 (22.2) |

| 3–4 weeks | 10 (8.8) | 9 (9.8) | 1 (5.6) |

| More than 4 weeks | 10 (8.8) | 8 (8.7) | 3 (16.7) |

| Treatment before surgery§ | |||

| Chemotherapy | 87 (100) | 72 (90.0) | 15 (83.3) |

| Radiotherapy | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Other | 13 (13.0) | 8 (10.0) | 3 (16.7) |

| Health Professionals | Round 1 SurveyN = 72 | Round 2 SurveyN = 67 | COS Endorsement N = 61 |

| COS endorsement, N (%) | – | – | 61 (100.0) |

| Male, N (%) | 54 (75.0) | 49 (73.1) | 47 (77.1) |

| Age range in years, N (%) | |||

| ≤40 | 10 (13.9) | 10 (14.9) | 7 (11.5) |

| 41–59 | 33 (45.8) | 28 (41.8) | 26 (42.6) |

| 51–60 | 24 (33.3) | 24 (35.8) | 23 (37.7) |

| > 60 | 5 (6.9) | 5 (7.5) | 5 (8.2) |

| Job role, N (%) | |||

| Consultant surgeon | 53 (73.6) | 50 (74.6) | 47 (77.1) |

| Surgical registrar | 2 (2.8) | 1 (1.5) | 1 (1.6) |

| Clinical specialist nurse | 17 (23.6) | 16 (23.9) | 13 (21.3) |

| Length of consultant experience¶, years, N (%) | |||

| <5 | 5 (9.6) | 3 (6.1) | 2 (4.3) |

| 5–10 | 11 (21.2) | 11 (22.4) | 10 (21.7) |

| >10 | 36 (69.2) | 35 (71.4) | 34 (73.9) |

COS indicates core outcome set; SD, standard deviation.

*Data missing for 5 patients in round 1 and 4 patients in round 2.

†Data missing for 1 patient in both round 1 and round 2.

‡Data missing for 3 patients in round 1 and 2 patients in round 2.

§Data missing for 16 patients in round 1, 14 patients in round 2 and 2 patients at the consensus meeting.

¶Data missing for one consultant each at round 1, round 2 and COS endorsement.

Health professionals and patients all rated the same 28 items as essential with patients also rating another 25 items as essential (Table 3). Therefore, 53 items were retained for round 2. Ten of these were identified as overlapping with each other [eg, “choking when eating” (item 11) was covered by “able to eat and drink more easily” (item 3)] so they were combined and merged, meaning that 43 items were taken forward to round 2 (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Rating of items in Round 1∗

| Item | Item Description (n = 68) | Median (Range) | % of Patients Rating Item (n = 116) | Outcome | Median (Range) | % of Professionals Rating Item (n = 72) | Outcome | Eligible to be Taken Forward to Round 2 | ||

| 7–9† | 1–3† | 7–9† | 1–3† | |||||||

| 1 | Able to carry out usual activities | 9 (3–9) | 91.2 | 0.9 | essential | 8 (3–9) | 87.5 | 1.6 | essential | yes |

| 2 | Able to participate/enjoy physical activities | 9 (3–9) | 86.0 | 1.8 | essential | 8 (3–9) | 87.5 | 1.6 | essential | yes |

| 3 | Able to eat/drink more easily | 9 (3–9) | 87.8 | 1.7 | essential | 8 (5–9) | 89.1 | 0.0 | essential | yes |

| 4 | Able to swallow without pain | 9 (3–9) | 91.3 | 0.9 | essential | 8 (3–9) | 82.8 | 1.6 | essential | yes |

| 5 | Able to enjoy healthy/balanced eating pattern | 9 (3–9) | 86.8 | 1.8 | essential | 7 (3–9) | 60.9 | 1.6 | not essential | yes |

| 6 | Problems with acid indigestion/ heartburn including at night (reflux) | 8 (2–9) | 78.8 | 4.4 | essential | 7 (4–9) | 60.9 | 0.0 | not essential | yes |

| 7 | Problems eating socially | 8 (1–9) | 72.6 | 7.1 | essential | 7 (3–9) | 59.4 | 3.1 | not essential | yes |

| 8 | Problems with regurgitation and/or vomiting | 8 (1–9) | 75.9 | 5.4 | essential | 7 (3–9) | 76.6 | 1.6 | essential | yes |

| 9 | Flatulence | 7 (1–9) | 69.3 | 6.1 | not essential | 6 (3–9) | 43.8 | 1.6 | not essential | no |

| 10 | Difficulties breathing | 8 (1–9) | 78.9 | 6.1 | essential | 7 (3–9) | 54.7 | 1.6 | not essential | yes |

| 11 | Problems with choking when eating‡ | 8 (1–9) | 79.5 | 5.4 | essential | 8 (3–9) | 79.7 | 1.6 | essential | yes |

| 12 | Problems with appetite loss | 8 (1–9) | 73.2 | 7.1 | essential | 7 (3–9) | 64.1 | 3.1 | not essential | yes |

| 13 | Problems with sense of taste | 7 (1–9) | 59.5 | 11.7 | not essential | 6 (1–9) | 39.1 | 12.5 | not essential | no |

| 14 | Sudden dizziness, sweating and/or feeling drained after eating (dumping) | 8 (1–9) | 76.4 | 4.5 | essential | 7 (3–9) | 62.5 | 1.6 | not essential | yes |

| 15 | Nausea | 7 (1–9) | 69.6 | 7.1 | not essential | 7 (3–9) | 67.2 | 3.1 | not essential | no |

| 16 | Diarrhoea | 8 (2–9) | 73.0 | 1.8 | essential | 7 (3–9) | 60.9 | 4.7 | not essential | yes |

| 17 | Having good general health | 9 (3–9) | 89.4 | 1.8 | essential | 7 (2–9) | 73.4 | 1.6 | essential | yes |

| 18 | Problems with general pain | 7 (1–9) | 75.0 | 5.4 | essential | 7 (2–9) | 68.8 | 4.7 | not essential | yes |

| 19 | Problems with weak voice/ hoarseness | 7 (1–9) | 60.0 | 12.7 | not essential | 7 (2–9) | 50.0 | 9.4 | not essential | no |

| 20 | Constipation | 7 (1–9) | 57.5 | 9.7 | not essential | 6 (2–9) | 32.8 | 7.8 | not essential | no |

| 21 | Coughing | 7 (1–9) | 64.9 | 12.6 | not essential | 6 (2–9) | 46.9 | 3.1 | not essential | no |

| 22 | Dry mouth | 7 (1–9) | 56.8 | 13.5 | not essential | 6 (1–9) | 26.6 | 15.6 | not essential | no |

| 23 | Problems with sleeping§ | 8 (1–9) | 74.1 | 5.4 | essential | 7 (2–9) | 62.5 | 6.3 | not essential | yes |

| 24 | Fatigue | 8 (1–9) | 77.3 | 6.4 | essential | 7 (2–9) | 56.3 | 4.7 | not essential | yes |

| 25 | Problems with weight | 7 (1–9) | 63.7 | 8.0 | not essential | 6 (3–9) | 48.4 | 4.7 | not essential | no |

| 26 | Feeling in control of weight and appearance | 8 (2–9) | 74.3 | 4.4 | essential | 6 (2–9) | 43.8 | 12.5 | not essential | yes |

| 27 | Feeling satisfied/confident with one's body | 8 (2–9) | 72.3 | 3.6 | essential | 6 (2–9) | 50.0 | 9.4 | not essential | yes |

| 28 | Hair loss | 5.5 (1–9) | 40.7 | 23.9 | not essential | 6 (1–9) | 28.1 | 17.2 | not essential | no |

| 29 | Interested in/able to enjoy sex | 7 (1–9) | 53.6 | 17.9 | not essential | 6 (2–9) | 48.4 | 7.8 | not essential | no |

| 30 | Relationships with friends | 8 (2–9) | 77.0 | 1.8 | essential | 7 (2–9) | 65.6 | 6.3 | not essential | yes |

| 31 | Relationships with family | 9 (1–9) | 84.8 | 1.8 | essential | 7 (2–9) | 76.6 | 4.7 | essential | yes |

| 32 | Cognitive function | 8 (1–9) | 72.6 | 6.2 | essential | 7 (2–9) | 56.3 | 6.3 | not essential | yes |

| 33 | Anxiety | 7 (1–9) | 61.1 | 10.6 | not essential | 7 (2–9) | 59.4 | 4.7 | not essential | no |

| 34 | Depression | 8 (1–9) | 68.1 | 13.3 | not essential | 7 (2–9) | 68.8 | 3.1 | not essential | no |

| 35 | Problems with changes in general mood | 7 (1–9) | 67.0 | 13.4 | not essential | 7 (2–9) | 65.6 | 4.7 | not essential | no |

| 36 | Money worries due to loss of earnings | 7 (1–9) | 52.2 | 18.6 | not essential | 7 (1–9) | 67.2 | 4.7 | not essential | no |

| 37 | Overall quality of life | 9 (1–9) | 85.8 | 1.8 | essential | 8 (2–9) | 93.8 | 1.6 | essential | yes |

| 38 | Spiritual or faith issues | 5 (1–9) | 34.5 | 38.1 | not essential | 6 (1–9) | 42.2 | 20.3 | not essential | no |

| 39 | Improving patient's ability to eat and drink‡ | 9 (3–9) | 94.7 | 0.9 | essential | 7 (2–9) | 73.0 | 1.6 | essential | yes |

| 40 | Overall survival | 9 (5–9) | 93.8 | 0.0 | essential | 9 (5–9) | 98.4 | 0.0 | essential | yes |

| 41 | Cancer-specific survival¶ | 9 (5–9) | 95.5 | 0.0 | essential | 9 (5–9) | 95.3 | 0.0 | essential | yes |

| 42 | Chance of cancer returning¶ | 9 (1–9) | 87.5 | 1.8 | essential | 9 (6–9) | 92.2 | 0.0 | essential | yes |

| 43 | Inoperability | 9 (1–9) | 85.6 | 2.7 | essential | 8 (3–9) | 89.1 | 3.1 | essential | yes |

| 44 | Organ injury | 9 (3–9) | 82.1 | 0.9 | essential | 7 (3–9) | 73.4 | 3.1 | essential | yes |

| 45 | Hemorrhage | 8 (1–9) | 79.6 | 4.4 | essential | 7 (4–9) | 76.6 | 0.0 | essential | yes |

| 46 | Chyle/pleural leak | 8 (1–9) | 80.7 | 4.4 | essential | 8 (4–9) | 84.4 | 0.0 | essential | yes |

| 47 | Anastomotic leak | 8 (1–9) | 89.3 | 1.8 | essential | 9 (5–9) | 95.3 | 0.0 | essential | yes |

| 48 | Conduit necrosis | 9 (1–9) | 89.3 | 0.9 | essential | 9 (5–9) | 95.3 | 0.0 | essential | yes |

| 49 | Need for insertion of further tubes | 8 (1–9) | 75.0 | 4.5 | essential | 6 (1–9) | 48.4 | 12.5 | not essential | yes |

| 50 | Laryngeal nerve palsy | 9 (1–9) | 82.7 | 1.8 | essential | 7 (2–9) | 68.8 | 4.7 | not essential | yes |

| 51 | Wound infection or dehiscence | 8 (1–9) | 82.1 | 4.5 | essential | 7 (2–9) | 51.6 | 4.7 | not essential | yes |

| 52 | Cardiac complications | 9 (1–9) | 77.7 | 3.6 | essential | 7 (3–9) | 64.1 | 1.6 | not essential | yes |

| 53 | Renal complications | 9 (1–9) | 76.8 | 3.6 | essential | 7 (3–9) | 50.0 | 3.1 | not essential | yes |

| 54 | Severe urine infection (septicaemia) | 8 (1–9) | 80.2 | 3.6 | essential | 6 (2–9) | 37.5 | 6.3 | not essential | yes |

| 55 | Cerebral complications | 9 (1–9) | 77.5 | 2.7 | essential | 7 (2–9) | 53.1 | 6.3 | not essential | yes |

| 56 | Liver failure | 9 (1–9) | 80.4 | 3.6 | essential | 6 (1–9) | 46.9 | 12.5 | not essential | yes |

| 57 | Respiratory complications | 9 (1–9) | 85.8 | 2.7 | essential | 7 (3–9) | 71.9 | 0.0 | essential | yes |

| 58 | Deep vein thrombosis; Pulmonary embolism | 9 (1–9) | 80.4 | 3.6 | essential | 7 (3–9) | 71.9 | 1.6 | essential | yes |

| 59 | Re-ventilation | 9 (1–9) | 84.1 | 1.8 | essential | 8 (4–9) | 89.1 | 0.0 | essential | yes |

| 60 | In-hospital mortality | 9 (1–9) | 84.8 | 5.4 | essential | 9 (7–9) | 100.0 | 0.0 | essential | yes |

| 61 | Esophageal stricture‡ | 9 (1–9) | 79.5 | 4.5 | essential | 7 (4–9) | 78.1 | 0.0 | essential | yes |

| 62 | Pyloric dilatation‡ | 8 (1–9) | 79.5 | 4.5 | essential | 7 (4–9) | 71.9 | 0.0 | essential | yes |

| 63 | Severe problems related to nutrition | 8 (1–9) | 81.4 | 2.7 | essential | 7 (4–9) | 81.3 | 0.0 | essential | yes |

| 64 | Empyema | 8 (1–9) | 78.2 | 3.6 | essential | 7 (3–9) | 67.2 | 3.1 | not essential | yes |

| 65 | Additional surgery due to abdominal hernia | 8 (1–9) | 74.5 | 6.4 | essential | 6 (2–9) | 40.6 | 7.8 | not essential | yes |

| 66 | Colonic interposition | 9 (1–9) | 86.2 | 1.8 | essential | 8 (2–9) | 75.0 | 7.8 | essential | yes |

| 67 | Diaphragmatic hernia repair | 9 (1–9) | 81.8 | 2.7 | essential | 7 (2–9) | 68.8 | 7.8 | not essential | yes |

| 68 | Need for another operation | 9 (1–9) | 85.5 | 3.6 | essential | 8 (1–9) | 78.1 | 6.3 | essential | yes |

*Items ordered as they appeared in the Round 1 questionnaire.

†Survey items in Round 1 were categorized as “essential” and retained for Round 2 if they met the following cutoff criteria: (i) rated between 7 and 9 by ≥70% of respondents, and; (ii) rated between 1 and 3 by <15% of respondents.

‡excluded – after discussion it was concluded that these items were covered by item number 3 “being able to eat/drink more easily.”

§excluded – after discussion it was concluded that this item was covered by item number 6 “Problems with acid indigestion/heartburn including at night (reflux).”

¶excluded – after discussion it was concluded that these items could be put under the generic survival term of item number 40 “overall survival.”

Items in italics were merged with the adjacent item in italics at the end of round 1.

Because of the high percentage of items rated essential by patients in round 1, more stringent criteria were agreed by the study team (J.B., S.B., N.B., K.A., K.C.) for round 2. These more rigorous pre-defined criteria were: items to retain would be rated 8–9 (rather than 7–9) by ≥70% and 1–3 by <15% of patients or professionals.

Round 2

Response rates were high with 108/116 (93%) patients who completed round 1 contactable, of whom 94/108 (87%) returned the questionnaire in addition to 67/72 (93%) professionals. Using the more rigorous (8–9 by ≥70%) criteria, 34 items (79%) were rated essential by patients with 12 (28%) of these also rated essential by professionals. There was concern that 34 items would be an unfeasible number to discuss at the consensus meetings. As further survey rounds were not possible, a post hoc decision was made to further restrict the criteria. Items were taken forward for the consensus meetings if: (i) rated 8–9 by ≥70% and 1–3 by <15% of patients, and (ii) rated 8–9 by >50% (a majority) and 1–3 by <15% of health professionals. This identified 19 items rated 8–9 by >50% professionals, all of which were rated 8–9 by ≥70% patients and taken to the consensus meeting (Table 4). As these were post-hoc criteria, the study team gave further consideration to the 15 discordant items. Many were related to less common adverse events that might require a reoperation (thus captured in that item) or were generic surgical complications that may not be considered as appropriate for a COS specific to esophageal cancer surgery. Other discordant items were covered by retained items (eg, relationships with family/friends overlapped with overall quality of life). Round 2 Delphi results showed that 5 of the 19 items were considered by both patients and professionals to be of very high priority, with >90% of both patients and professionals rating these items 8–9 (Table 5). The study team agreed that these items (overall survival, in-hospital mortality, overall quality of life, conduit necrosis, and anastomotic leak) should be presented at the consensus meetings as being in the final COS.

TABLE 4.

Rating of Items in Round 2∗

| Item | Item Description (n = 43) | Median (Range) | % of Patients Rating Item(n = 94) | Outcome | Median (Range) | % of Professionals Rating Item(n = 67) | Outcome | Taken Forward to Patient Consensus Meeting | ||

| 8–9† | 1–3† | 8–9† | 1–3† | |||||||

| 1 | Usual activities and enjoy physical activities | 9 (7–9) | 96.7 | 0.0 | essential | 8 (7–9) | 89.2 | 0.0 | essential | yes |

| 2 | Eat and drink more easily | 9 (7–9) | 94.6 | 0.0 | essential | 8 (5–9) | 84.6 | 0.0 | essential | yes |

| 3 | Swallow without pain | 9 (7–9) | 94.6 | 0.0 | essential | 8 (2–9) | 78.5 | 3.3 | essential | yes |

| 4 | Enjoy healthy balanced eating pattern | 9 (6–9) | 88.2 | 0.0 | essential | 8 (2–9) | 60.0 | 1.6 | essential | yes |

| 5 | Reflux | 8 (5–9) | 89.2 | 0.0 | essential | 8 (2–9) | 52.3 | 1.6 | essential | yes |

| 6 | Problems eating socially | 8 (1–9) | 68.8 | 3.3 | not essential | 7 (4–9) | 47.7 | 0.0 | not essential | no |

| 7 | Regurgitation/vomiting‡ | 8 (1–9) | 79.6 | 3.3 | essential | 8 (5–9) | 49.2 | 0.0 | not essential | no |

| 8 | Difficulties breathing‡ | 8 (4–9) | 76.3 | 0.0 | essential | 7 (5–9) | 39.1 | 0.0 | not essential | no |

| 9 | Appetite loss | 8 (1–9) | 60.2 | 3.3 | not essential | 7 (2–9) | 33.8 | 1.6 | not essential | no |

| 10 | Dumping | 8 (1–9) | 67.4 | 3.4 | not essential | 7 (5–9) | 43.1 | 0.0 | not essential | no |

| 11 | Diarrhoea | 8 (2–9) | 68.8 | 2.2 | not essential | 7 (2–0) | 40.0 | 1.6 | not essential | no |

| 12 | Good general health | 9 (5–9) | 88.0 | 0.0 | essential | 8 (4–9) | 75.4 | 0.0 | essential | yes |

| 13 | General pain discomfort | 8 (1–9) | 67.7 | 1.1 | not essential | 7 (4–9) | 30.8 | 0.0 | not essential | no |

| 14 | Fatigue‡ | 8 (2–9) | 73.1 | 1.1 | essential | 7 (4–9) | 44.6 | 0.0 | not essential | no |

| 15 | Feeling in control of weight/ appearance | 8 (2–9) | 67.0 | 1.1 | not essential | 7 (3–8) | 29.2 | 3.3 | not essential | no |

| 16 | Feeling satisfied and confident with one's body | 8 (4–9) | 59.6 | 0.0 | not essential | 7 (2–9) | 29.2 | 3.3 | not essential | no |

| 17 | Relationships with family/friends‡ | 8 (6–9) | 80.9 | 0.0 | essential | 8 (4–9) | 50.0 | 0.0 | not essential | no |

| 18 | Cognitive function‡ | 8 (1–9) | 75.3 | 4.4 | essential | 7 (5–9) | 35.4 | 0.0 | not essential | no |

| 19 | Overall quality of life | 9 (5–9) | 91.5 | 0.0 | essential | 9 (8–9) | 100.0 | 0.0 | essential | yes |

| 20 | Overall survival | 9 (7–9) | 97.8 | 0.0 | essential | 9 (7–9) | 98.4 | 0.0 | essential | yes |

| 21 | Inoperability | 9 (1–9) | 92.5 | 2.2 | essential | 9 (5–9) | 89.2 | 0.0 | essential | yes |

| 22 | Organ injury‡ | 8 (1–9) | 83.9 | 1.1 | essential | 7 (4–9) | 47.7 | 0.0 | not essential | no |

| 23 | Hemorrhage‡ | 8 (1–9) | 83.9 | 1.1 | essential | 7 (3–9) | 47.7 | 1.6 | not essential | no |

| 24 | Chyle/pleural leak | 8 (4–9) | 86.0 | 0.0 | essential | 8 (4–9) | 78.5 | 0.0 | essential | yes |

| 25 | Anastomotic leak | 9 (1–9) | 91.4 | 1.1 | essential | 9 (7–9) | 98.5 | 0.0 | essential | yes |

| 26 | Conduit necrosis | 9 (1–9) | 93.5 | 1.1 | essential | 9 (7–9) | 96.9 | 0.0 | essential | yes |

| 27 | Reinsertion of drains | 8 (4–9) | 62.4 | 0.0 | not essential | 7 (3–9) | 18.5 | 1.6 | not essential | no |

| 28 | Laryngeal nerve palsy‡ | 8 (1–9) | 82.8 | 1.1 | essential | 7 (4–9) | 47.7 | 0.0 | not essential | no |

| 29 | Wound infection‡ | 8 (1–9) | 71.0 | 2.2 | essential | 7 (3–8) | 13.8 | 1.6 | not essential | no |

| 30 | Cardiac complications‡ | 9 (1–9) | 76.3 | 2.2 | essential | 7 (4–9) | 43.1 | 0.0 | not essential | no |

| 31 | Renal complications‡ | 8 (1–9) | 72.0 | 2.2 | essential | 7 (4–9) | 24.6 | 0.0 | not essential | no |

| 32 | Cerebral complications‡ | 9 (1–9) | 76.3 | 2.2 | essential | 7 (3–9) | 35.4 | 1.6 | not essential | no |

| 33 | Liver failure‡ | 9 (1–9) | 77.4 | 2.2 | essential | 7 (3–9) | 23.1 | 3.3 | not essential | no |

| 34 | Respiratory complications | 9 (1–9) | 81.7 | 1.1 | essential | 8 (4–9) | 55.4 | 0.0 | essential | yes |

| 35 | Deep vein thrombosis; Pulmonary embolism | 9 (1–9) | 83.7 | 2.2 | essential | 8 (4–9) | 56.9 | 0.0 | essential | yes |

| 36 | Re-ventilation | 9 (1–9) | 90.3 | 1.1 | essential | 8 (4–9) | 78.5 | 0.0 | essential | yes |

| 37 | In-hospital mortality | 9 (1–9) | 96.8 | 2.2 | essential | 9 (7–9) | 98.5 | 0.0 | essential | yes |

| 38 | Severe problems related to nutrition | 8 (3–9) | 78.3 | 1.1 | essential | 8 (4–9) | 60.9 | 0.0 | essential | yes |

| 39 | Empyema‡ | 8 (1–9) | 79.3 | 1.1 | essential | 7 (1–9) | 46.9 | 3.3 | not essential | no |

| 40 | Abdominal hernia | 8 (1–9) | 65.9 | 1.1 | not essential | 6 (1–9) | 15.6 | 3.3 | not essential | no |

| 41 | Colonic interposition | 9 (1–9) | 90.0 | 1.1 | essential | 8 (4–9) | 79.7 | 0.0 | essential | yes |

| 42 | Diaphragmatic hernia repair‡ | 9 (1–9) | 89.1 | 1.1 | essential | 7 (3–9) | 37.5 | 1.7 | not essential | no |

| 43 | Need for another operation | 9 (1–9) | 90.2 | 1.1 | essential | 8 (–9) | 64.1 | 0.0 | essential | yes |

*Items ordered as they appeared in the Round 2 questionnaire.

†Items were categorized as “essential” and retained for the consensus meeting if they met the following cutoff criteria: (i) rated 8–9 by ≥70% and 1–3 by <15% of patients, and; (ii) rated 8–9 by >50% and 1–3 by <15% of health professionals.

‡Discordant items, rated as essential by patients but not professionals.

TABLE 5.

Final Outcome of 19 Items Taken Forward to Consensus Meeting (in Descending Order of the Percentage of Patients Voting the Item IN the Final COS)

| Item Description | % Patients Voting Item IN, OUT, or UNSURE* | Decision After Voting | Final Decision Following Discussion and Second Vote | ||

| IN | OUT | UNSURE | |||

| Overall survival | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | IN |

| Inhospital mortality | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | IN |

| Overall quality of life | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | IN |

| Conduit necrosis | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | IN† |

| Anastomotic leak | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | IN† |

| Being able to carry out usual activities and participate /enjoy physical activities | 95 | 5 | 0 | IN | IN‡ |

| Having good general health | 75 | 0 | 25 | IN | IN‡ |

| Being able to eat/drink more easily | 90 | 0 | 10 | IN | IN§ |

| Being able to swallow without pain | 85 | 0 | 15 | IN | IN§ |

| Inoperability | 85 | 0 | 15 | IN | IN |

| Respiratory complications (infection, collapsed lung) | 85 | 5 | 10 | IN | IN |

| Need for another operation | 85 | 5 | 10 | IN | IN |

| Severe problems related to nutrition | 80 | 10 | 10 | IN | IN |

| Problems with acid indigestion/heartburn, including at night (reflux) | 70 | 5 | 25 | IN | IN |

| Reventilation (need to go to ITU on breathing machine) | 65 | 15 | 20 | UNSURE | OUT¶ |

| Colonic interposition | 60 | 5 | 35 | UNSURE | OUT|| |

| Chyle/pleural leak | 55 | 15 | 30 | OUT | OUT|| |

| Deep vein thrombosis; Pulmonary embolism | 45 | 20 | 35 | OUT | OUT |

| Able to enjoy healthy/balanced eating pattern | 45 | 30 | 25 | OUT | OUT |

COS, core outcome set; ITU, intensive treatment unit; n/a, ‘Top 5’ items rated 8–9 by >90% of patients and professionals in Round 2 and therefore not voted on at consensus meeting.

*IN: voted “in” by ≥70% of participants; OUT: voted “in” by <60% and “out” by ≥15% of participants; UNSURE: voted “in” by 60–69% of participants.

†Items combined to form a single item—conduit necrosis and anastomotic leak.

‡Items incorporated into overall quality of life.

§Items combined to form a single item—the ability to eat and drink.

¶Items incorporated into ‘respiratory complications’.

||Items incorporated in to ‘the need for another operation, at any time.

Phase 3: Consensus Meetings

The patient consensus meeting was held in Bristol, United Kingdom (September 2015) and attended by 20 (21%) patients from the South-West United Kingdom (Table 2). There were no objections to the five highly rated items presented as being in the COS.

Results from voting on the remaining 14 items are shown in Table 5. Nine of the 14 items were voted “in’ and 3 “out.” One of these (“reventilation”) was voted “out” on the basis that it could be incorporated into “respiratory complications.” Two items were voted “unsure” (“colonic interposition” and “chyle/pleural leak”) and were discussed in further detail during the meeting. It was agreed that, as both of these events commonly lead to the need for another operation, they could be incorporated into “need for another operation, any cause” and so were subsequently voted “out” as additional items. Further indepth discussion during the patient consensus meeting led to the merging of “conduit necrosis” and “anastomotic leak” into a single item, “being able to eat/drink more easily” and “being able to swallow without pain” were merged to become “the ability to eat and drink,” and “being able to carry out usual activities and participate/enjoy physical activities” and “having good general health” were incorporated into “quality of life.” This resulted in a proposed COS of 10 items (Table 6).

TABLE 6.

Final Core Outcome Set for Esophageal Cancer Resection Surgery

| 1. Overall survival |

| 2. Inhospital mortality |

| 3. Inoperability |

| 4. The need for another operation related to their primary esophageal cancer resection surgery |

| 5. Respiratory complications |

| 6. Conduit necrosis and anastomotic leak |

| 7. Severe nutritional problems |

| 8. The ability to eat and drink |

| 9. Problems with acid indigestion or heartburn |

| 10. Overall quality of life |

Although a professional consensus meeting was planned, it was agreed to be of little value as all items rated 8–9 by the majority of professionals (>50%) in round 2 were incorporated into the proposed final COS. It was agreed that it would be more informative to validate the final COS identified by the Delphi and the patient consensus meeting. Professionals responding to round 2 were therefore emailed information about the proposed COS, and asked to comment on its content and whether or not they would endorse it. Those who did not respond after 6 weeks were sent an email reminder. In total, 61/67 (91%) responded and endorsed the COS with some comments about how the outcome should be measured rather than questioning the outcomes themselves.

DISCUSSION

This study has established a COS for use in effectiveness trials of esophageal cancer resection surgery. A comprehensive list of 68 relevant clinical outcomes and patient-reported outcomes was generated from multiple and varied information sources as part of earlier work. In this study, robust survey methods using the Delphi technique were used to gain consensus among key stakeholders, including patients and health professionals, on the most important outcomes to include in a COS. Consensus was reached on a final core set comprising 10 items. The COS comprises health outcome domains related to overall survival; in-hospital mortality; inoperability; the need for another operation at any time; respiratory complications; conduit necrosis and anastomotic leak; severe nutritional problems; the ability to eat and drink; problems with acid indigestion or heartburn; and overall quality of life. It is recommended that future trials include measures of these outcomes and additional outcomes as particularly relevant to the research question.

Recently, a system for defining and recording in-hospital outcomes of esophageal cancer surgery has been developed.25 This is incredibly valuable and will go some way to address the current problem with outcome reporting. However, this system focuses on short term complications (some of which are included in the proposed COS described here—eg, respiratory complications, conduit necrosis and anastomotic leak and nutritional problems) and there remains a need for a clinical effectiveness outcome set to use in pragmatic trials, which includes the views of patients about long term outcomes. To our knowledge, this is the first COS to be developed for esophageal cancer resection surgery. It is recommended that the outcome domains included in the COS are measured and reported in all clinical effectiveness trials of esophageal cancer resection surgery. This includes studies of primary esophagectomy or esophagectomy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with esophageal, esophagogastric junctional adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, or high grade dysplasia (final pretreatment tumor stage between high grade dysplasia and T4aN1M0). The COS may also be suitable for other studies and audits of esophageal cancer resection surgery. There may be a place to develop a COS that can be used for other types of treatment for esophageal cancer (eg, chemotherapy or radiotherapy) or a generic core set with additional items for specific subsets of patients undergoing particular treatments. We would encourage further work in this area although the initial challenge is to promote the widespread use of the COS to improve data synthesis.

Although there is no universally agreed methodological approach to COS development, a recent review showed that studies are adopting a more structured approach, typically involving a systematic literature review and consensus methods (such as Delphi, nominal group) to assess and develop agreement among key stakeholders;26 methods that were used in the current study. The Delphi technique is frequently used to achieve consensus, enabling participants to vote anonymously and without direct interaction, thereby avoiding situations where the group may be dominated by specific individuals, and enabling participants to change their ratings in light of others’ opinions.17 Patient involvement in COS development is key to ensuring that clinical effectiveness trials evaluate the benefits and harms of treatment from both a clinical and patient perspective but is often overlooked.17 This may lead to the exclusion of important outcomes.9,26 In this study, stakeholders were sampled to include participants with knowledge of the benefits and harms of esophageal cancer resection surgery, including patients and specialist professionals. Participants’ characteristics reflected a typical broad range (eg, for patients: age, sex, educational background, marital status, length of hospital stay, experience of neoadjuvant treatment; and for professionals: age, sex, specialty/job title, experience). All participants had undergone primary esophagectomy or esophagectomy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy between 1 month and 5 years previously. It is likely that this sample would include participants with a range of experiences postoperatively, including participants who are healthy, those with varying types and severity of symptoms and those with recurrent disease, though it is possible that recruiting an even more diverse sample of participants (eg, patients’ partners or close family) may have resulted in different outcomes being included in the COS. The number of participants in this study is in keeping with that of similar studies,23,24 and response rates throughout the different phases of this study were high; a factor considered integral to maximizing the quality of studies that use the Delphi process to develop COSs.17

This study has some limitations. It did not involve international participants. However, a comprehensive long list of 901 possible outcomes that could be reported after esophageal cancer resection surgery was identified from multiple sources, including systematic reviews of clinical and patient-reported outcomes reported in the international literature.4,5,20 At present, this study provides the best evidence on which to base recommendations, but should be repeated in other countries and settings to validate the COS more widely. The COS developed in the present study is intended to complement the core information set (CIS). Similar items included in the CIS were long-term survival, in-hospital death, chances of inoperability, information about major complications, impact on eating and drinking in the longer term, and long-term overall quality of life.

Participants demonstrated difficulty prioritizing items after 2 survey rounds and therefore more stringent cutoff criteria were applied in round 2. It is possible that the use of different criteria in Rounds 1 and 2 may have impacted on the content of the final COS, although it was important to ensure that the consensus meeting was not overwhelmed with too many items for discussion. Items rated highly by patients but not professionals (and that were discarded when more stringent criteria were applied) were, however, predominantly related to outcomes that were covered by other retained items or to less common adverse events. Patients may have rated these items highly because they did not have the clinical knowledge that these items were less common. Items related to rarer adverse events were not considered to be of relevance to a COS intended for use as a minimum dataset for effectiveness trials of esophageal cancer resection surgery. One alternative to using more stringent cutoff criteria would have been to conduct a third survey round but this was outside of the scope of this study and was considered unlikely to result in many more items being discarded as participants had already demonstrated difficulty prioritizing. Finally, a decision was made not to hold a professionals’ consensus meeting because the patient meeting proposed a COS comprising 10 outcomes, which encompassed all items that >50% of professionals had rated highly (8–9). This is supported by the findings from the endorsement survey, in which all responding professionals indicated support for the content and use of the COS. Furthermore, seeking endorsement enabled a greater number of professionals to be surveyed than would have been possible to include in a consensus meeting.

The development of this COS seeks to promote the standardized selection and reporting of outcomes and thereby facilitate the robust evaluation of esophageal cancer resection surgery, which is currently inconsistent and lacks standard methodology.4 Further work is now needed to explore best methods for measuring the individual outcomes included in the COS, including work to delineate the definitions and parameters of the individual outcomes and to inform the selection of validated measurement instruments for the assessment of patient-reported outcomes. It will also be important in the future to evaluate the uptake and use of this COS in standardizing the selection and reporting of outcomes across clinical trials of esophageal cancer resection surgery.27

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the health professionals and patients who gave up their time to participate in the Delphi surveys and the patient consensus meeting. The authors would also like to thank Claudette Blake and Steve Beech for their administrative support throughout the study.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The ROMIO study group comprises co-applicants on the ROMIO feasibility study (funded by the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment Programme, project number 10/50/65) who contributed to the conception and design of the study and assisted in the acquisition and interpretation of data and who are listed here in alphabetical order: C. Paul Barham (University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom), Richard Berrisford (Plymouth Hospitals NHS Trust, United Kingdom), Jenny Donovan (University of Bristol, United Kingdom), Jackie Elliott (Bristol Gastro-Oesophageal Support and Help Group, United Kingdom), Stephen Falk (University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom), Robert Goldin (Imperial College London, United Kingdom), George Hanna (Imperial College London, United Kingdom), Andrew Hollowood (University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom), Sian Noble (University of Bristol, United Kingdom), Grant Sanders (Plymouth Hospitals NHS Trust, United Kingdom), Tim Wheatley (Plymouth Hospitals NHS Trust, United Kingdom).

The CONSENSUS (Core Outcomes and iNformation SEts iN SUrgical Studies) Esophageal Cancer working group comprises health professionals who contributed to the design of the study, assisted in the acquisition of data (including participating in at least one round of the Delphi survey) and interpretation of data and are listed here in alphabetical order: Derek Alderson (University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom), Bilal Alkhaffaf (Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom), William Allum (The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom), Stephen Attwood (Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom), Hugh Barr (Gloucestershire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom), Issy Batiwalla (North Bristol NHS Trust, United Kingdom), Guy Blackshaw (University Hospital of Wales, United Kingdom), Marilyn Bolter (Plymouth Hospitals NHS Trust, United Kingdom), Abrie Botha (Guy and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom), Jim Byrne (University Hospitals Southampton NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom), Joanne Callan (Heart of England NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom), Graeme Couper (NHS Lothian, United Kingdom), Khaled Dawas (University College London Hospitals, United Kingdom), Chris Deans (NHS Lothian, United Kingdom), Claire Goulding (Plymouth Hospitals NHS Trust, United Kingdom), Simon Galloway (South Manchester University Hospitals NHS Trust, United Kingdom), Michelle George (Maidstone and Tunbridge Wells NHS Trust, United Kingdom), Jay Gokhale (Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom), Mike Goodman (The Royal Bournemouth and Christchurch Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom), Richard Hardwick (Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom), Ahmed Hassn (Princess of Wales Hospital, United Kingdom), Mark Henwood (Glangwili General Hospital, United Kingdom), David Hewin (Gloucestershire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom), Simon Higgs (Gloucestershire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom), Jamie Kelly (University Hospitals Southampton NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom), Richard Kryzstopik (Royal United Hospitals Bath NHS Trust, United Kingdom), Michael Lewis (Norfolk and Norwich University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom), Colin MacKay (NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde, United Kingdom), James Manson (Singleton Hospital, United Kingdom), Robert Mason (Guy and St. Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom), Ruth Moxon (Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom), Muntzer Mughal (University College London Hospitals, United Kingdom), Sue Osborne (Yeovil District Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom), Richard Page (Liverpool Heart and Chest Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom), Raj Parameswaran (Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, United Kingdom), Simon Parsons (Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust, United Kingdom), Simon Paterson-Brown (NHS Lothian, United Kingdom), Anne Phillips (Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom), Shaun Preston (Royal Surrey County Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom), Kishore Pursnani (Lancashire Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom), John Reynolds (St James’ Hospital, Dublin, Ireland), Bruno Sgromo (Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom), Mike Shackcloth (Liverpool Heart and Chest Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom), Jane Tallett (Norfolk and Norwich University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom), Dan Titcomb (University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom), Olga Tucker (Heart of England Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom), Tim Underwood (University of Southampton, United Kingdom), Jon Vickers (Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom), Mark Vipond (Gloucestershire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom), Lyn Walker (University Hospitals of North Midlands NHS Trust, United Kingdom), Neil Welch (Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust, United Kingdom), John Whiting (University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom), Jo Price (Royal United Hospitals Bath NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom), Peter Sedman (Hull and East Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust, United Kingdom), Thomas Walsh (Connolly Hospital, Dublin, Ireland), Jeremy Ward (Lancashire Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom).

W.A. receives speaker honoraria from Lilly, Nestle, and Taiho and honoraria for consulting/advising on trials for Lilly and Nestle.

This study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment Programme (project number 10/50/65). This work was supported by the Medical Research Council ConDUCT-II (Collaboration and innovation for Difficult and Complex randomised controlled Trials In Invasive procedures) Hub for Trials Methodology Research (MR/K025643/1) (http://www.bristol.ac.uk/social-community-medicine/centers/conduct2/). J.B. is an NIHR Senior Investigator. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the MRC, the NIHR, the NHS or the Department of Health (United Kingdom).

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Revicki DA, Frank L. Pharmacoeconomic evaluation in the real world. Effectiveness versus efficacy studies. Pharmacoeconomics 1999; 15:423–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singal AG, Higgins PDR, Waljee AK. A primer on effectiveness and efficacy trials. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2014; 5:e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gartlehner G, Hansen RA, Nissman D, Lohr KN, Carey TS. Criteria for distinguishing effectiveness from efficacy trials in systematic reviews. In: Technical Review. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blencowe NS, Strong S, McNair AG, et al. Reporting of short-term clinical outcomes after esophagectomy: a systematic review. Ann Surg 2012; 255:658–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Macefield RC, Jacobs M, Korfage IJ, et al. Developing core outcome sets: methods for identifying and including patient-reported outcomes (PROs). Trials 2014; 15:49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Briez N, Piessen G, Bonnetain F, et al. Open versus laparascopically-assisted oesophagectomy for cancer: a multicentre randomised controlled phase III trial - the MIRO trial. BMC Cancer 2011; 11:310–1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Avery KNL, Metcalfe C, Berrisford R, et al. The feasibility of a randomized controlled trial of esophagectomy for esophageal cancer - the ROMIO (Randomized Oesophagectomy: Minimally Invasive or Open) study: protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2014; 15:200–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirkham JJ, Gargon E, Clarke M, et al. Can a core outcome set improve the quality of systematic reviews? A survey of the Co-ordinating Editors of Cochrane Review Groups. Trials 2013; 14:21–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williamson PR, Altman DG, Blazeby JM, et al. Developing core outcome sets for clinical trials: issues to consider. Trials 2012; 13:132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clarke M. Standardising outcomes for clinical trials and systematic reviews. Trials 2007; 8:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Macleod MR, Michie S, Roberts I, et al. Biomedical research: increasing value, reducing waste. Lancet 2014; 383:101–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirkham JJ, Dwan KM, Altman DG, et al. The impact of outcome reporting bias in randomised controlled trials on a cohort of systematic reviews. BMJ 2010; 340:c365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The COMET (Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials) Initiative. Available at: http://www.comet-initiative.org/ Accessed on September 7, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirkham JJ, Gorst S, Altman DG, et al. Core outcome set-standards for reporting: the COS-STAR statement. PLoS Med 2016; 13:e1002148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Royal College of Surgeons of England. National Oesophago-Gastric Audit 2013 [NHS website]. 2013. Available at: http://digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB11093/clin-audi-supp-prog-oeso-gast-2013-rep.pdf Accessed on September 7, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McNair AG, MacKichan F, Donovan JL, et al. What surgeons tell patients and what patients want to know before major cancer surgery: a qualitative study. BMC Cancer 2016; 16:258–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sinha IP, Smyth RL, Williamson PR. Using the Delphi technique to determine which outcomes to measure in clinical trials: recommendations for the future based on a systematic review of existing studies. PLoS Med 2011; 8:e1000393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gillies K, Entwistle V, Treweek SP, et al. Evaluation of interventions for informed consent for randomised controlled trials (ELICIT): protocol for a systematic review of the literature and identification of a core outcome set using a Delphi survey. Trials 2015; 16:484–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Potter S, Holcombe C, Ward JA, et al. the BRAVO Steering Group. Development of a core outcome set for research and audit studies in reconstructive breast surgery. Br J Surg 2015; 102:1360–1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blazeby JM, Macefield R, Blencowe NS, et al. Core information set for oesophageal cancer surgery. Br J Surg 2015; 102:936–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brookes ST, Macefield RC, Williamson PR, et al. Three nested randomized controlled trials of peer-only or multiple stakeholder group feedback within Delphi surveys during core outcome and information set development. Trials 2016; 17:409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.TurningPoint [voting software]. Ohio: Turning Technologies. [Google Scholar]

- 23.van ’t Hooft J, Duffy JM, Daly M, et al. A core outcome set for evaluation of interventions to prevent preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol 2016; 27:49–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gerritsen A, Jacobs M, Henselmans I, et al. Developing a core set of patient-reported outcomes in pancreatic cancer: a Delphi survey. Eur J Cancer 2016; 57:68–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Low DE, Alderson D, Cecconello I, et al. International consesnsus on standardization of data collection for complications associated with esophagectomy. Ann Surg 2015; 262:286–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gorst SL, Gargon E, Clarke M, et al. Choosing important health outcomes for comparative effectiveness research: an updated review and user survey. PLoS One 2016; 11:e0146444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Copsey B, Hopewell S, Becker C, et al. Appraising the uptake and use of recommendations for a common outcome data set for clinical trials: a case study in fall injury prevention. Trials 2016; 17:131–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]