Abstract

Background: The evidence for and our understanding of community-level strategies such as policies, system, and environmental changes that support healthy eating and active living is growing. However, researchers and evaluation scientists alike are still not confident in what to recommend for preventing or sustaining declines in the prevalence of obesity.

Methods: The Systematic Screening and Assessment (SSA) methodology was adapted as a retrospective process to confirm obesity declines and to better understand what and how policies and programs or interventions may contribute as drivers. The Childhood Obesity Declines (COBD) project's adaptation of the SSA methodology consisted of the following components: (1) establishing and convening an external expert advisory panel; (2) identification and selection of sites reporting obesity declines; (3) confirmation and review of what strategies occurred and contextual factors were present during the period of the obesity decline; and (4) reporting the findings to sites and the field.

Results/Discussion: The primary result of the COBD project is an in-depth examination of the question, “What happened and how did it happen in communities where the prevalence of obesity declined?” The primary aim of this article is to describe the project's methodology and present its limitations and strengths.

Conclusions: Exploration of the natural experiments such that occurred in Anchorage, Granville County, New York City, and Philadelphia is the beginning of our understanding of the drivers and contextual factors that may affect childhood obesity. This retrospective examination allows us to: (1) describe targeted interventions; (2) examine the timeline and summarize intervention implementation; (3) document national, state, local, and institutional policies; and (4) examine the influence of the reach and potential multisector layering of interventions.

Keywords: : community interventions, evaluation, methods, natural experiments, obesity prevention, obesity, policy

Introduction

Obesity has become a public health crisis.1 Fortunately, there has been a growing number of reports of obesity declines in states and communities.2 However, why or how these changes are occurring are not well understood. While surveillance data provide information on prevalence and trends, it does not explain the contextual factors and mechanisms associated with the changes in obesity prevalence. There have been a number of calls from the Health and Medicine Division of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, previously the Institutes of Medicine, for the field of obesity prevention to focus on multisetting and population-based research and evaluation.3,4 Although the evidence and our understanding of it is growing, the depth and breadth of evidence have not evolved to the point where researchers and evaluation scientists alike are confident that they know what to do to prevent or sustain declines in the prevalence of obesity. There is much attention given to broad-based community level strategies such as policies, system, and environmental changes that support healthy eating and active living. However, to date there is no singular formula for the mix of strategies, the level of intensity, or the scope of implementation that is required to improve obesity prevalence and population health. The Systematic Screening and Assessment (SSA) has gathered attention as one approach that recognizes the need for rigor and expert opinion in building the evidence base for complex fields where the evidence is difficult to be ascertained by traditional clinical trials.5

The SSA was originally developed as a prospective process to assess the evaluability of promising interventions, with recommendations and guidance provided to sites as its primary product. The method answered the question, “Is this intervention ready to be evaluated?” At that time, there was a great need to identify sites or communities that had enough infrastructure to conduct an evaluation of an obesity prevention intervention in various settings within a community. SSA allowed the identification of interventions worthy of full-scale rigorous evaluation investment and offered the promise of being easily adapted to other fields where there is little evidence or evidence that is questionable and evaluation is needed. However, during its development no one considered using the method to answer a different type of question, specifically a retrospective vs. a prospective inquiry.

For the Childhood Obesity Declines (COBD) project, an advisory committee of the National Collaborative on Childhood Obesity Research (NCCOR) adapted the SSA methodology to explore the question, “What happened and how did it happen in communities where the prevalence of obesity measured by body mass index (BMI) declined?” SSA was adapted as a retrospective process to confirm obesity declines and to better understand what some communities that reported declines were doing, including how policies and programs or interventions may have contributed to these declines as drivers. Our primary aim is to share what we learned from communities that have had declines with those that would like to engage in obesity prevention efforts and interventions. In addition, this adaptation of the SSA may serve to inform the field of obesity prevention research and evaluation scientists as a potential method of investigation that complements other study designs such as traditional randomized control trials, cohort, and/or case–control studies.

NCCOR is a private/public partnership between the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF), the CDC, the NIH, and the USDA. The RWJF, one of the NCCOR partner agencies, funded ICF to carry out this project. This article describes in detail the adaption of the SSA methodology used to explore what happened in four communities in the United States that reported obesity declines during various periods between 2004 and 2012.

Methods

The steps of the original SSA methodology are described and compared to the steps used in this adaptation for this exploratory study of COBD in Table 1. The original SSA methodology was adapted in a variety of steps to meet the research question addressed by the COBD project. First, instead of conducting a landscape assessment of various interventions that had not previously been evaluated, we identified sites where obesity declines occurred using published literature and an expert panel external to the project team to facilitate the identification of sites. The selected sites did not focus on a singular intervention designed to address obesity (step 2), but included an array of other community specific policies, systems, and environmental changes that may have influenced or supported the success of that interventions' intention to improve healthy eating and active living in their effort to reduce obesity rates. Furthermore, site visit interviews were not limited to intervention staff as was the case in the original SSA step 5, but included a wide array of key stakeholders and individuals engaged in efforts directly and indirectly affiliated with any interventions that occurred. The COBD also did not include feedback and guidance to the sites, step 7, or sharing results of the study with national funders for evaluation funding, step 8, since these communities had already accomplished their goal of obesity prevention and declines.

Table 1.

Comparison of Original Systematic Screening and Assessment for Evaluability to the Adaptation Used by Childhood Obesity Declines Project

| Process steps | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study component | Original SSA for evaluability | Adaptation of SSA for COBD |

| Establishing an external expert advisory panel | Identification and selection of an EEP. | Identification and selection of an EEP. |

| Identification and selection of sites | Promising intervention | Reporting obesity declines |

| Identification of potential interventions that had not been previously evaluated based on suggestions and proposals from the field, including EEP. | Identification of sites with reported declines in obesity based on peer reviewed literature, media reports, and EEP suggestions. | |

| Review of potential interventions by project team relative to specific inclusion criteria and EEP for their opinion of an intervention's value to the field. | Review of potential sites by project team and EEP relative to specific inclusion criteria and selection process. | |

| Confirmation and review | Readiness and capacity for evaluation | Strategies and contextual factors |

| Preliminary preparation for evaluability assessment (interventions' document review, preliminary intervention logic model, site visit interview guides). | Preliminary preparation for site visit (reported decline in BMI verified and documentation reviewed, time line of policies and programs implemented, key informant interview guides). | |

| One to 3-day site visit with 4–6 key intervention staff. | Three to 5-day site visit with 16–30 key informants and stakeholders. | |

| Reporting the findings to sites and the field | Creation of site visit summary report reviewed by EEP and sites for clarification and accuracy. | Creation of site visit summary report reviewed by EEP and sites for clarification and accuracy. |

| Teleconference guidance to site with subject matter expert. | Not applicable. | |

| Recommendations for full evaluation by EEP shared with national funders. | Not applicable. | |

| Study results published and disseminated with the field. | Study results published and disseminated with the field. | |

COBD, Childhood Obesity Declines; EEP, External Expert Panel; SSA, Systematic Screening and Assessment.

The COBD project's adaptation of the SSA methodology consisted of the following components: (1) establishing and convening an external expert advisory panel; (2) identification and selection of sites reporting obesity declines; (3) confirmation and review of what strategies occurred and contextual factors present during the period of the obesity decline; and (4) reporting the findings to sites and the field.

Establishing and Convening an External Expert Advisory Panel

Beyond the COBD project advisory team that consisted of research and evaluation scientists from RWJF, the CDC, the NIH, and ICF, the project team established an external expert panel (EEP). One of the core reasons for this component of the SSA method's process is that in a field that does not have a comprehensive body of evidence there is the need for inclusion of thoughts and perspectives to ground the study in the best opinions the field has to offer. The 15 member EEP not only provided suggestions on additional sites for consideration but also they added depth and experience to the project team and served as a sounding board in the selection and review of what occurred in the sites that reported obesity declines. The EEP helped guide our work based on their wealth of expertise in evaluation, nutrition, physical activity, community measurement, and community-based obesity prevention (Table 2).

Table 2.

List of Childhood Obesity Declines Project External Expert Panel Members

| Rachel Ballard | Office of Chronic Disease Prevention, NIH |

| Nisha Botchwey | School of City and Regional Planning, Georgia Institute of Technology |

| Bridget Catlin | Population Health Institute, University of Wisconsin |

| Allen Cheadle | Center for Community Health and Evaluation, Group Health Research Institute |

| Jamie Chriqui | Institute of Health Research and Policy, University of Illinois at Chicago |

| Patricia Crawford | School of Public Health, University of California, Berkeley |

| Christina Economos | Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy, Tufts University |

| Karen Glanz | Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania |

| Shiriki Kumanyika | Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania |

| Cathy Nonas | New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, NYC, New York |

| Punam Ohri-Vachaspati | Arizona State University |

| Debra Rog | Westat |

| Brian Salaens | Seattle's Children's Hospital |

| Jay Variyam | Economic Research Service, USDA |

| Sallie Yoshida | The Sarah Samuel Center for Public Health Policy and Evaluation |

Identification and Selection of Potential Sites Reporting Obesity Declines

A search of peer-reviewed and gray literature, including media reports, identified potential sites for inclusion. The EEP was convened in the fall of 2012 to review the project design, including preliminary inclusion and exclusion criteria and suggestions for additional sites for consideration by the project team. Nineteen potential sites were identified.

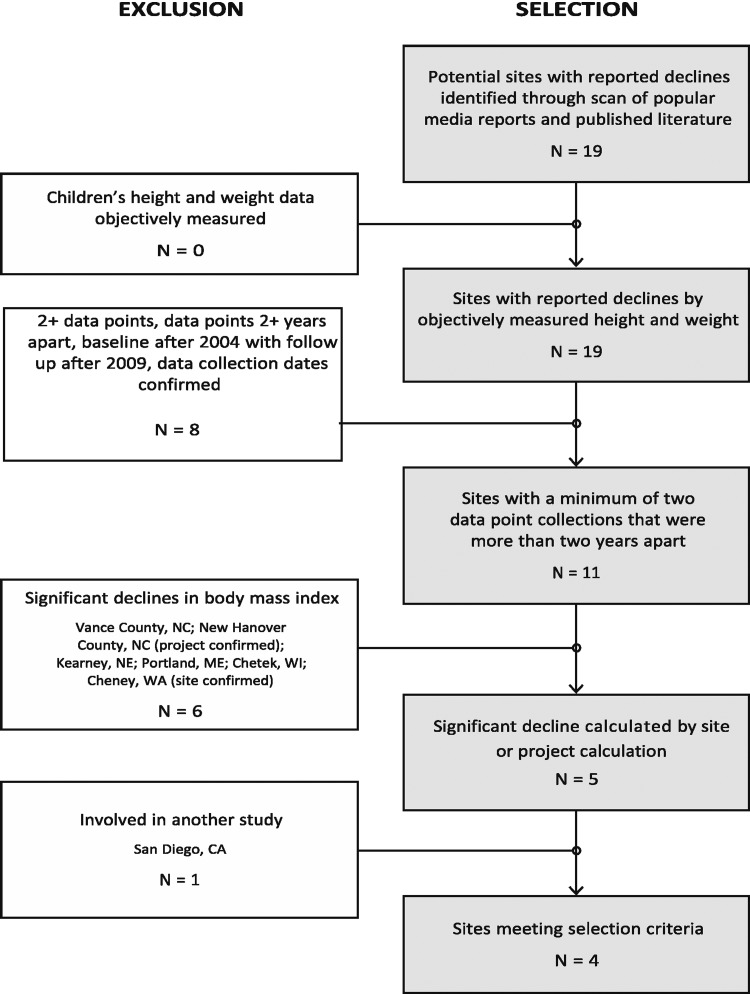

The COBD project team vetted and finalized the initial inclusion and exclusion criteria with the EEP to aid in site selection. The first inclusion criteria stated that the site must have documented a decline in obesity prevalence using objective measures of height and weight collected by trained staff for child BMI calculation. At least two data collection points were necessary. The baseline data collection had to occur in 2004 or later, and the follow-up data collection had to occur in 2009 or later, with a minimum of 2 years between data collection points. Seven sites were excluded because their data points were outside the data collection window of 2004 to 2009, were 2 or <2 years apart, or had only one data point. An eighth site was excluded because the data on obesity declines came from numerous school districts across the state, and it was unlikely that this project's methodology could document sufficiently what occurred in a single site visit (Fig. 1). Finally, the decline in BMI was required to be statistically significant. Project team members reviewed the results published in peer-reviewed or other articles to confirm the use of appropriate analytical methods to measure the decline. In some cases, project team members asked site researchers to conduct additional tests (e.g., separating age groups or districts), and in some cases COBD project team members requested data from sites to conduct the additional significance tests. Six sites were excluded because their reported declines in BMI were not statistically significant.

Figure 1.

Childhood Obesity Declines site exclusion and selection process.

The next step was to review the remaining sites and finalize their selection. Various additional factors were considered in the team's review of the potential sites for inclusion such as the type of community (e.g., urban vs. rural), the population make-up in terms of disparities and underserved populations, and the focal settings for targeted interventions. Upon review, a second site was excluded because other studies were currently underway examining the reported decline in obesity in that state. The final sites selected (n = 4) were Anchorage, AK; New York City, NY; Philadelphia, PA; and Granville County, NC.6–10

Review and Confirmation of What Strategies and Contextual Factors Occurred during the Period of the Obesity Decline

The project team identified a key contact or informant at each of the four sites. The key informant was contacted and invited to participate in this project. Upon agreement to participate, they were asked to identify additional individuals they thought relevant to interview and to complete a preliminary survey of potential strategies that had occurred during and before the time of the reported decline in obesity in children. In preparation for the site visit, any additional documentation or materials the site contact thought helpful was also requested.

To identify what strategies occurred in the communities before and during the period of reported obesity decline, ∼150 potential strategies were compiled. Potential strategies were identified from published reports such as the Institutes of Medicine3,4 and CDC recommendations11 for healthy eating and active living. These included strategies such as policies, system, and environmental changes and interventions for institutions and communities in key settings where children spend time such as schools, early care and education (ECE) facilities, healthcare facilities, and the community at large. The inventory of strategies documented whether respondents knew of the presence of strategies by setting. Sites also had the option to provide other examples. Key informants for each site shared the inventory with any relevant community stakeholders using a snowball sampling technique for completion. The inventory results provided information about types of strategies that might have been present in each site as a focal point for the interview discussions. The strategies were then discussed for greater understanding during the interviews to document more specific details related to the implementation and contextual factors that were in place during the period of the decline.

In preparation for each site visit, site visitors drafted a timeline of strategy implementation, including interventions and relevant national and state policies identified by the project team before the site visit. The draft timeline of events and policies was shared during each interview as a tool to assist in recall, as well as for review. Strategies, local policies, campaigns, or other relevant events were added based on the discussions with the key informants during the site visit. Interview guides were also developed and tailored to different types of stakeholders, such as community members, policy or program developers, policy or program implementers, or evaluators and/or researchers. Key informants helped identify an agreeable date for the weeklong visit and a schedule of interviews the sites thought appropriate. There were 16 individual interviews in Granville County, 19 interviews with 22 people in Anchorage (2 group interviews, 1 with 2 people and another with 3 people, and 17 individual interviews), 30 individual interviews in New York City, and 22 interviews with 23 people (1 group interview with 2 people and 21 individual interviews) in Philadelphia.

Once completed, the site visit interview data were analyzed using qualitative analysis software ATLAS.ti for common themes across interviews to summarize an overall picture of the events, programs, policies, and system and environmental changes that occurred.12 Site visitors also documented other contextual factors that the site key informants thought were critical to the declines in obesity, such as local champions, political issues, or local activities that could potentially enhance the community's awareness and willingness to engage in healthy eating and active living.

Disseminating the Findings to the EEP, Sites, and the Field

The project team developed Site Summary Reports for each site that were shared with the EEP for review and comment and then shared with the site key informant for content confirmation. The Site Summary Reports and findings were shared again with the EEP in Spring 2015. These companion articles and the Summary Reports serve as the final step in the SSA method to ensure that the study findings are shared with the site and other communities for their future work on community-level obesity prevention, as well as with the scientific research and evaluation community to expand the evidence base.

Discussion

The primary aim of this article is to describe the adaptation of the SSA method process. Using this process provided an in-depth examination of the question, “What happened and how did it happen in communities where the prevalence of obesity measured by BMI declined?” The information we obtained enhances our ability to understand and potentially disseminate the components necessary within communities that have undertaken obesity prevention efforts. The secondary aim is to recognize the limitations and strengths of using this methodology. The COBD and its use of this adaptation of the SSA methodology does not allow for broad generalizability because of the limited number of communities examined, but provides a preliminary window into the possible contextual factors and mechanisms associated with the changes in childhood obesity prevalence. The COBD was an exploratory assessment conducted post hoc so no attribution or causation can be inferred. The SSA method is retrospective in nature and therefore has the limitation of participants' lack of recall and specificity of memory, as well as program staff turnover that occurred since the implementation of the intervention(s). In addition, some details on interventions and strategies are lacking. In particular, there are no data on the intensity and reception or uptake sometimes referred to as “dose” by the community, and the fidelity of the policies and interventions is unknown.

However, there are many strengths to using the SSA method for this purpose. First, the decline in the prevalence of obesity was verified as statistically significant based on objectively measured heights and weights for BMI. Multiple individuals were interviewed and their collective memory of events can be seen as confirmatory, as a single individual's memory may be limited. The COBD project focused on population- vs. individual-level strategies for obesity prevention and is grounded in the social ecological model (SEM), considering multiple levels and settings, as well as recognizing the potential benefits from a spectrum of efforts needed to make population changes in individual behavior and health.13

The evidence of a decline in the prevalence of obesity was stronger in younger children, and across all four communities multiple strategies were used in settings where younger children spend a significant part of their day (e.g., elementary schools and preschools). Furthermore, a number of strategies the communities engaged in aligned with those recommended by the Institute of Medicine and/or CDC, even in low-income communities that generally have higher obesity rates and poorer health outcomes. Finally, in a field such as obesity prevention that has a limited evidence base for community-based strategies, the EEP expert opinions added strength to study protocol and interpretation of findings.

A secondary result of this project's methodology is introducing a different type of investigative process to the field of community-level or population-level obesity prevention. Examining the effects of natural experiments can be challenging methodologically. The complexity, unpredictability, and the lack of control, often termed rigor, are characteristic of natural experiment investigations. However, these considerations do not in themselves mean that natural experiments are not worthy of our attention. There remains a need to develop new methodologies that embrace and accommodate these factors as COBD has done by choosing to use the SSA method.

Conclusions

The COBD project was novel in the following respects. We followed a systematic process that incorporates existing techniques, adapted it in new ways, and used it as the framework to explore communities with evidence of communities reporting declines in obesity. The unique nature of the methodology used in this study is based on the question, “What happened and how did it happen?,” rather than “What happened that fits into our predetermined expectations?” Predetermined expectations often influence and limit our consideration of strategies, implementation designs, response categories or types, key informant or stakeholders to consult, and analytical requirements for specific types of data collected.

This retrospective, systematic, screening, and assessment of “What Happened and How” in communities reporting a decline in the prevalence of obesity allowed us to: (1) describe targeted intervention settings (e.g., school or ECE), age range of reported decline, population characteristics, community size, type, and location in the United States; (2) examine the timeline of events, policies, and interventions; (3) summarize national, state, local, and institutional policies by type and focus; and (4) suggest the potential influence within multiple SEM sectors of site obesity prevention efforts as described in the companion articles of this supplement.14–16 The implications for research and evaluation are also described.17

Exploration of the natural experiments that occurred in Anchorage, Granville County, New York City, and Philadelphia allows us to further understand what communities are doing and what may have contributed to declines in the prevalence of obesity. This study is only one piece in the large puzzle of questions in our understanding of “What happened and how.” Other questions include what follow-up studies are needed to further understand the drivers and contextual factors that are key to effective obesity prevention, and where should the findings of this study take us in designing better more appropriate studies of natural experiments of community-based obesity prevention. However, what we do know is that this adaptation of the SSA method allowed us to understand and confirm that promoting and supporting communities in their policy, system, and environmental change efforts at multiple levels are associated with obesity declines in young children in these four communities.

Acknowledgments

National Collaborative for Childhood Obesity Research (NCCOR) is a private and public partnership among the CDC, NIH, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF), and USDA that provided technical assistance for this project. FHI360 serves as the Coordinating Center for NCCOR. ICF served as the lead contractor for the project. The authors thank NCCOR members Melissa Abelev, Veronica Uzoebo, and Ruth Morgan of the Food and Nutrition Service of USDA for participation in the project advisory committee. The authors thank the many site key stakeholders for their time and cooperation with interviews and site program documentation and the project site visitors who conducted the interviews and drafted the site summary reports, specifically Stacey Willocks, MS, Stephanie Frost, PhD, Michael Greenberg, JD, MPH, Katherine Reddy, MS, and Joseph Fruh, BS. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the CDC, NIH, or any of the other project agencies. The RWJF funded this project (ID No. 71772—Analyzing the Signs of Progress in Childhood Obesity).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

The authors did not report any conflicts of interest or financial disclosures. The findings and conclusions of this report are those of the authors and do not represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, ICF, National Institutes of Health, or Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

References

- 1.Wang Y, Hyunjung L. The global childhood obesity epidemic and the association between socio-economic status and childhood obesity. Int Rev Psychiatry 2012;24:176–188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dietz WH, Economos CD. Progress in the control of childhood obesity. Pediatrics 2015;135:e559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine. Accelerating Progress in Obesity Prevention: Solving the Weight of the Nation. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute of Medicine. Evaluating Obesity Prevention Efforts: A Plan for Measuring Progress. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leviton LC, Kettel Khan L, Dawkins N. (eds). The Systematic Screening and Assessment Method: Finding Innovations Worth Evaluating. New Directions for Evaluation No. 125. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Granville-Vance District Health Department. Priority—Chronic Disease and Lifestyle Issues. 2012 State of the County Health Report. Oxford, NC: Granville-Vance District Health Department, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Obesity in K-7 students—Anchorage, Alaska, 2003–04 to 2010–11 school years. MMWR 2013;62:426–430 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Obesity in K-8 students—New York City, 2006–07 to 2010–11 school years. MMWR 2011;60:1673–1678 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robbins JM, Mallya G, Polansky M, et al. Prevalence, disparities, and trends in obesity and severe obesity among students in the Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, school district, 2006–2010. Prev Chronic Dis 2012;9:E145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robbins JM, Mallya G, Wagner A, et al. Prevalence, disparities, and trends in obesity and severe obesity among students in the School District of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2006–2013. Prev Chronic Dis 2015;12:E134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity Prevention Strategies. Available at www.cdc.gov/obesity/resources/strategies-guidelines.html (last accessed March15, 2017)

- 12.ATLAS.ti. Version 7.5. Berlin: Scientific Software Development, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 13.McLeroy K, Bibeau D, Steckler A, et al. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Behav 1988;15:351–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ottley PG, Dawkins-Lyn N, Harris C, et al. Childhood Obesity Declines Project: An exploratory study of strategies identified in communities reporting declines. Child Obes 2018;14:S12–S21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dooyema C, Jernigan J, Lowry Warnock A, et al. Childhood Obesity Declines Project: Review of state enacted policies. Child Obes 2018;14:S22–S31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jernigan J, Kettel Khan L, Dooyema C, et al. Childhood Obesity Declines Project: Highlights of community strategies and policies. Child Obes 2018;14:S32–S39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Young-Hyman D, Morris K, Kettel Khan L, et al. Childhood Obesity Declines Project: Implications for research and evaluation approaches. Child Obes 2018;14:S40–S44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]