Abstract

Okadaic acid (OKA) is a protein phosphatase-2A inhibitor that is used to induce neurodegeneration and study disease states such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Lanthionine ketimine-5-ethyl ester (LKE) is a bioavailable derivative of the naturally occurring brain sulfur metabolite, lanthionine ketimine (LK). In previously conducted studies, LKE exhibited neuroprotective and neurotrophic properties in murine models but its mechanism of action remains to be clarified. In this study, a recently established zebrafish OKA-induced AD model was utilized to further elucidate the neuroprotective and neurotrophic properties of LKE in the context of an AD-like condition. The fish were divided into 3 groups containing 8 fish per group. Group #1= negative control, Group #2= 100nM OKA, Group #3= 100nM OKA + 500μM LKE. OKA caused severe cognitive impairments in the zebrafish, but concomitant treatment with LKE protected against cognitive impairments. Further, LKE significantly and substantially reduced the number of apoptotic brain cells, increased brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and increased phospho-activation of the pro-survival factors pAkt (Ser 473) and pCREB (Ser133). These findings clarify the neuroprotective and neurotrophic effects of LKE by highlighting particular survival pathways that are bolstered by the experimental therapeutic LKE.

Keywords: Zebrafish, Okadaic acid, Lanthionine ketimine-5-ethyl-ester, BDNF, CREB, PKB/Akt

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a chronic neurodegenerative disease associated with progressive cognitive decline. Research has shown that the main neuropathological hallmarks of AD are the formation of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) [1]. Current animal models used in the research of AD do not provide us with quick nor cost-effective approaches to collecting data and screening for potential drug candidates. Alternative animal models need to be utilized so that the research on AD is more efficient in this way. The zebrafish has emerged as a promising tool in modeling AD. Several AD models using zebrafish have been created but none of them are able to recreate both molecular and behavioral hallmarks of AD [2]. To fill this need, we have been exploring the use of the protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) and 2A (PP2A) inhibitor, okadaic acid (OKA) [3], to induce AD-like pathology in zebrafish. Using carefully treated OKA zebrafish we were able to demonstrate many of the phenotypes of AD in zebrafish. Zebrafish treatment with OKA resulted in learning and memory impairments, increased Aβ fragment deposition, senile plaque induction, and hyperphosphorylated tau protein [4]. Furthermore, we used this OKA-treatment as a paradigm to test the efficacy of an experimental therapeutic, lanthionine-ketimine-5-ethyl-ester (LKE), to reduce AD-like molecular and behavioral effects in the zebrafish model.

Lanthionine ketimine (LK) is a natural sulfur amino acid metabolite which is formed through alternative reactions of the transsulfuration pathway followed by subsequent transamination [5, 6]. The exact physiological function(s) of LK is unknown and was perceived as being metabolic waste. However, recent findings suggest that LK has neurotophic and neuroprotective properties through its interaction with collapsin response mediator protein 2 (CRMP2). A synthetic derivative of LK, LKE, designed to be cell-penetrating and readily bioavailable also demonstrated neurotrophic and neuroprotective properties [6, 7].

The present study was designed to investigate the therapeutic potential and mechanism of LKE in the OKA-induced AD model in zebrafish. LKE was able to rescue the cognitive decline caused by OKA which was corroborated by a decrease in apoptotic cells. LKE also induced a significant increase in the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), the phosphorylation/activation of protein kinase B (PKB/Akt), and the phosphorylation/activation of cAMP response element binding protein (CREB).

Materials and Methods

Animals

All animal experiments were approved by the University of Toledo Health Science Campus Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. AB zebrafish (Danio rerio) used in the various experiments were between the ages of twelve to fifteen months. The fish were divided into 3 groups, and each group contained 4 male and 4 female fish. They were housed at 26–28°C with a 14:10 h light/dark cycle with feeding twice a day. The fish were purchased from Zebrafish International Resource Center (Eugene, OR) (Catalog ID: ZL1).

Drug Treatment

Okadaic acid (OKA) sodium salt (product # O-5857) ˃98% pure was purchased from LC Laboratories (Woburn, MA, USA). The OKA was dissolved in 95% ethanol and further diluted in fish water to a concentration of 100nM. LKE was synthesized at the University of Toledo (Toledo, OH, USA) as previously described [7]. LKE was dissolved in water, and diluted to the final concentrations of 500μM. 3 different groups of fish were established; Group #1= negative control, Group #2= 100nM OKA, Group #3= 100nM OKA + 500μM LKE. For the negative control group, an ethanol volume equivalent to that used in dissolving the OKA was added to the water. The exposure period lasted for 9 days and the water along with the various treatments were refreshed every other day as described previously [4]. Before and after the treatments were conducted, the fish were subject to a learning & memory function test.

Learning and Memory Test

Pre-treatment (learning) and post-treatment (memory) tests were performed as described previously [8]. Briefly, the fish were placed into individual 10 liter aquariums (N=1 per aquarium) and assigned random numbers to assure that testing personnel were blinded. Each 10 liter aquarium was filled with 26–28°C DI/RO water with 60 mg/L of Instant Ocean® sea salt (Instant Ocean, Blacksburg, VA). Each aquarium was divided into two equal sections by a central opaque divider that allows for adequate space for the fish to swim from one side to the other side of the aquarium. One end of the aquarium is colored red as a means for visually distinguishing the two sections of the aquarium as zebrafish have the ability to see red [9]. Before the test is to begin, the fish have their diet restricted for 48–72 hours and are introduced to their respective aquariums for at least 48 hours prior to testing. Trials were initiated with a light tap (discriminative stimulus) at the center of the aquarium. After the light tap, there was a 5 second delay followed by food presentation. To avoid satiation and to keep the fish positively motivated, only a small amount of food (approximately 5 brine shrimp nauplii) was dispensed per trial. In 20 minute intervals, food presentation continued on alternating sides for a total of 28 trials (14 trials per side). A response was analyzed as correct if the fish was physically present on the side of food presentation within 5 seconds of the discriminative stimulus. Zebrafish are deemed to have learned the task when 75% of the responses are correct [8].

Western Blotting

For Western blot analysis, brain tissue was lysed in tissue extraction reagent (ThermoFisher, cat # FNN0071) plus 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (ThermoFisher, cat # 88266) and incubated for 30 minutes on ice. The samples were then centrifuged at 14000 rpm (4°C) for 10 minutes, and the supernatant was assayed for protein concentration by the Bradford method [10]. Equal amounts of protein were mixed with reducing sample buffer (62.5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 10% glycerol, 0.002% bromophenol blue, and 5% β-mercaptoethanol) and boiled for 5 min. at 98°C. Proteins were subject to electrophoresis across 10–15% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to polyvinylidine difluoride membranes (pore size 0.2μM & 0.45μM, cat # ISEQ00010 and cat # IPVH00010 respectively). The blots were blocked for 1 h at room temperature (RT) in Tris-buffered saline blocking buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl) containing 5% bovine serum albumin, and incubated in different primary antibodies (listed in Table 1) overnight at 4°C. Finally, the blots were incubated in HRP-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 hr at RT and visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (Bio-Rad, cat # 1705060).

Table 1.

Antibodies Used In This Study

| Antibody | Source | Dilution | Supplier | Catalog Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDNF | Rabbit | 1:500 | Bioss | bs-4989R |

| β-Actin | Rabbit | 1:2000 | Cell Signaling | #4967 |

| Phospho-Akt | Rabbit | 1:2000 | Cell Signaling | #4060 |

| Akt | Rabbit | 1:1000 | Cell Signaling | #4691 |

| Phospho-CREB | Rabbit | 1:1000 | Cell Signaling | #9198 |

| CREB | Rabbit | 1:1000 | Cell Signaling | #9197 |

TUNEL Assay

After their respective exposures and behavioral task completion, the zebrafish were euthanized by placing in <4°C water and then into 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C. The brains of the zebrafish were then removed with the aid of a dissecting microscope and LED lighting. After washing with 1× PBS, the brains were processed for paraffin-embedded tissue sectioning and sectioned at 6μM increments. Sections were then dewaxed by immersing in xylene for 5 minutes at room temperature and rehydrated sequentially by immersing slides through graded ethanol washes (100%, 95%, 70%, and 50%) for 5 minutes each at room temperature. After rehydration the sections were washed in 1× PBS for 5 minutes at room temperature, and allowed to permeabilize in proteinase K for 15 minutes. Lastly, the sections were incubated with TUNEL reaction mixture at 37°C for 60 minutes and stained with DAPI. Analysis of TUNEL results was conducted on the dorsal lateral pallium of the zebrafish. The dorsal lateral pallium of the zebrafish is homologous to the mammalian hippocampus and is responsible for the formation of memories [11–13].

Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as means ± SEM. Western blot and TUNEL assay statistical analysis was carried out using one-way ANOVA with a Newman-Keuls post-hoc test. A value of p < 0.05 was reported as significant. Zebrafish learning and memory was analyzed as previously described [14]. The mathematical model for learning was formulated to measure the probability, P, of a correct response and the formula used is:

Where “b” is the amount of learning that takes place, “c” is the number of trials it takes to reach half-maximum learning, and “t” is the trial number. These parameters, “b” and “c”, were measured using the SAS nonlinear modeling procedure NLIN. The parameter “b” will be referenced in the paper as “maximum learning”. Plots of the final prediction for P and the success frequency as functions of trial for each treated group were overlaid and used to display the fit of the estimated model.

Results

LKE Rescues the OKA Induced Memory Impairments

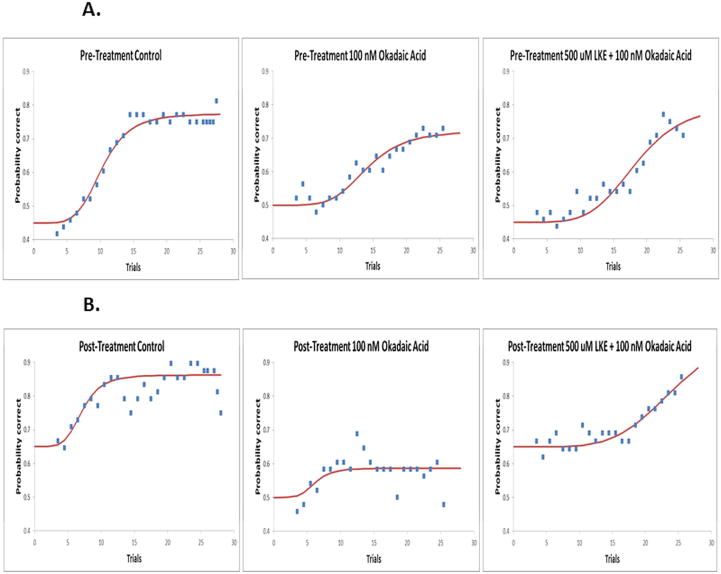

A pre-treatment test was conducted on all 3 groups, and then 10 days later, a post-treatment test was conducted. Even though Group #1 did not receive any treatment, a pre and post-treatment was still conducted on the group as a control. The 100nM OKA treated zebrafish (Group #2) showed no ability to remember; whereas the control zebrafish (Group #1) and the 500μM + 100nM OKA treated zebrafish (Group #3) both demonstrated evidence of memory (Fig. 1 A, B).

Figure 1.

Learning (pre-treatment) and memory (post-treatment) data of control, OKA treated, and LKE+OKA treated zebrafish. The dots on each graph represent the group’s running average at each trial point. The curved line represents a non-linear least-squares regression curve of the probability correct responses. A. Zebrafish were subject to the spatial alteration paradigm before being treated with their respective compounds. All 3 groups demonstrated the ability to learn by reaching 70–75% correct. B. After receiving their respective treatment, the zebrafish were again subject to the spatial alteration paradigm. The control and LKE+OKA groups demonstrated the ability to remember by starting the behavioral task at 65% instead of the random chance probability of 50%. In addition to memory demonstration, the control and LKE+OKA zebrafish increased performance demonstrated by reaching 85%–90% correct. The OKA group did not demonstrate memory retention by starting the post-treatment paradigm at random chance of 50%. They also did not increase performance, demonstrated by their max correct response of 55–60%. n= 8 (4 male and 4 female for both pre and post-treatment control), n= 8 (4 male and 4 female for both pre and post-treatment LKE+OKA), n= 8 (4 male and 4 female for both pre and post-treatment OKA)

Pre-treatment results

Group #1 demonstrated a pre-test maximum learning of about 77% which is 32% above the initial random chance of 45%. Measurement of half-maximal, which indicates a change in learning or memory of the fish, was established at around the 10th trial. Group #2 demonstrated a pre-test maximum learning of about 72% which is 22% above the initial random chance of 50%. Half-maximal learning was found to be at about the 14th trial. Group #3 had a maximum learning of about 77% which is 32% above the initial random chance of 50%. Half-maximal learning for Group #3 pre-test occurred around the 18th trial (Fig.1A).

Post-treatment results

Group #1 started the post-test at a 65% success rate which was already 20% higher than the pre-treatment test’s determined random chance of 45%. Group #1 performed at a maximum learning success rate of 86% and half of maximum learning (from the starting point of 65%) started at around the 7th trial. Group #2 started the post-treatment test at the random success rate of 50% and performed at a maximum success rate of around 58% with half maximum performance being around the 6th trial. Group #2 never reached a maximum performance of at least 70–75% and therefore it was concluded that memory was not demonstrated. Group #3 started the post-treatment test at a 65% success rate which was 15% higher than the pretest established random chance of 50%. Group #3, during the post-treatment test, established a maximum success rate of about 89% and half of maximum performance (from the starting point of 65%) was calculated to be around the 24th trial (Fig. 1B).

Decreased Apoptosis in LKE treated Zebrafish

Apoptosis, an indicator of cell death, was examined by conducting a TUNEL assay on the dorsal lateral pallium of the zebrafish. There was a 38% significant increase (p<.01) of the percentage of apoptotic cells in the zebrafish treated with 100nM OKA when compared to the control. In contrast, there was not a significant difference (p>0.05) between the zebrafish treated with 500μM LKE + 100nM OKA and the control zebrafish. When comparing the 500μM LKE + 100nM OKA to the 100nM OKA, a significant decrease (p<0.05) of 39% of apoptotic cells was observed. The TUNEL assay concludes that LKE is protecting the zebrafish dorsal lateral pallium from OKA induced cell death (Fig. 2 A, B).

Figure 2.

Pictures were taken of the dorsal lateral pallium located within the telencephalon of the zebrafish and analyzed by TUNEL assay. A. DAPI stain (blue) and TUNEL stain (green) and the overlay images taken using a 20× objective. B. DAPI stain (blue) and TUNEL stain (green) and the overlay images taken using a 100× objective. The images show an increase in apoptosis in the zebrafish dorsal lateral pallium treated with OKA which was analyzed and shown in C. Apoptosis was significantly increased in the dorsal lateral pallium of OKA treated zebrafish compared to the control and LKE+OKA treated zebrafish. No difference was found between the LKE+OKA and control group. The bar graphs are presented as means ± SEM; *p<0.05 **p<0.01, n= 4 (2 male and 2 female for control), n= 4 (2 male and 2 female for LKE+OKA), n= 4 (2 male and 2 female for OKA). D. Schematic overview of the whole adult zebrafish brain with sectioning scheme of the telencephalon. E. Schematic coronal section of the telencephalon indicating the specific area of interest, the dorsal lateral pallium. Zebrafish brain illustrations were adapted and modified from [48]. OB, Olfactory bulb; Ce, cerebellum; Dc, dorsal central pallium; Dl, dorsal lateral pallium; Dm, dorsal medial pallium; Dp, dorsal posterior pallium Tel, telencephalon; TO, tectum opticum.

The Neurotrophic Factor BDNF is increased in the LKE Treated Fish

BDNF is a neurotrophic factor that stimulates neuronal growth, differentiation, survival, regeneration, and repair. Its role in AD has been extensively studied, and it is believed that BDNF might protect against the progression of AD [15]. BDNF expression appears to be decreased by 40% in the OKA group when compared to the control, however, the post-hoc test determined there was no significant difference (p>0.05). When the 500μM LKE + 100 nM OKA group was compared to the control group, there is a 94% significant increase (p<0.05) of BDNF expression. A 135% significant increase (p<0.01) in BDNF expression when the 500μM LKE + 100 nM OKA group was compared to the 100 nM group (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

Zebrafish forebrain showcases an increase in neurotrophic signaling expression by western blot analysis. A. Immunoblotting with an anti-BDNF antibody shows an increase in the BDNF expression of LKE+OKA zebrafish when compared to the control and the OKA zebrafish. OKA zebrafish show a reduction of BDNF but no significant difference was found. B. Immunoblotting for pAkt (Ser473) with an anti-pAkt(Ser473) shows an increase in pAkt expression of LKE+OKA zebrafish when compared to the control and the OKA zebrafish. No significant difference found between the control group and OKA group even though pAkt seems to be reduced in the OKA group. C. Immunoblotting with an anti-pCREB (Ser133) antibody shows an increase in pCREB of LKE+OKA zebrafish when compared to the control and OKA treated zebrafish. No significant difference found between the control group and OKA group even though it appears that pCREB is reduced in the OKA group. The bar graphs are presented as means ± SEM; *p<0.05 **p<0.01, n= 4 (2 male and 2 female for control), n= 4 (2 male and 2 female for LKE+OKA), n=4 (2 male and 2 female OKA)

The Survival Protein, pAkt (Ser473), is increased in LKE treated Zebrafish

Akt, also known as protein kinase B, is a serine/threonine kinase that has a role in cell survival by inhibiting apoptosis. When the Ser473 epitope of Akt is phosphorylated, Akt is active and has the ability to further phosphorylate proteins such as Bcl-2-associated death promotor (BAD) resulting in a loss of pro-apoptotic function [16, 17]. It appears that expression of pAkt (Ser473) is reduced in the OKA group when compared to the control, however, the post-hoc test determined there was no significant difference (p>0.05). When compared to the control, the 500μM LKE + 100 nM OKA group had a 191% significant increase (p<0.05) in pAkt (Ser473) expression, and when compared to the 100 nM OKA group it had a significant increase (p<0.01) in pAkt (Ser473) expression of 255% (Fig. 3B).

The Cognitive Enhancer pCREB is increased in LKE treated Fish

CREB is activated upon phosphorylation of Ser133 which signals for neuronal survival and long-term potentiation (LTP) which are both important in keeping and forming memories respectively [18, 19]. Just as the previous results were for BDNF and pAkt expression, it appears that pCREB (Ser133) expression is decreased by 54% in the 100 nM OKA group when compared to the control, however post-hoc analysis determined there to be no significant difference (p>0.05). The LKE treated fish (500μM LKE + 100 nM OKA) showed a 147% significant increase (p<0.01) when compared to the 100 nM OKA group and a 93% significant increase when compared to the control (p<0.05) (Fig. 3C).

Discussion

The present study, we were able to demonstrate that LKE exhibited neuroprotection against the behavioral and pathological symptoms of OKA-induced AD zebrafish model. These protective effects included improved cognitive function. This is the first time that the effects of LKE have been demonstrated in the zebrafish OKA-induced AD model. A 500μM dose of LKE concomitantly administered with a 100 nM dose of OKA proved to be an effective prophylactic agent against OKA-induced neurotoxicity.

OKA is a protein phosphatase (PP) inhibitor, particularly of PP2A and PP1 [3]. Even though it is not classified as a neurotoxin, OKA is being used to induce neurotoxicity to study various neurodegenerative diseases including AD [20]. Just as the pathology observed in AD, OKA is able to trigger neurodegeneration, tau hyperphosphorylation, the accumulation of NFTs, Aβ deposition, oxidative stress, neuronal inflammation, and learning and memory impairment [21–23]. A major advantage of using OKA to study neurodegenerative diseases that cause cognitive deficiencies is that OKA does not change motor function [23, 24], therefore, the cognitive deficiencies revealed after OKA administration can be attributed to learning and memory impairments and not motor impairments. A recent report revealed that when zebrafish are exposed to 100 nM of OKA they sustain learning and memory impairment in addition to increased expression of phosphorylated tau, the deposition of Aβ-fragment, and plaque formation [4].

The effect on cognitive function of OKA and LKE+OKA was studied by a spatial alternation paradigm [8]. Before treatment, the to-be-OKA-treated-fish did demonstrate evidence of learning by having their probability correct reach just under 75% and by having a linear regression curve that resembled both (pre-treatment) the control group and LKE+OKA group. Long-term memory was assessed in the behavioral paradigm by removing the fish from the testing apparatus for 10 days after proving their ability to learn in the initial testing round (before treatment). After 9 days of treatment the fish would be reintroduced to the testing apparatus for a second round of testing (after treatment). If the zebrafish remember the task from 10 days earlier, then they would start the task at a higher probability correct than the random probability of around 50%. Also the number of trials needed to reach 70–75% would be reduced in comparison to the initial test [8]. After 9 days of treatment with OKA, their linear regression curve stayed steadily around 55–60%, indicating their inability to remember after OKA exposure.

The LKE+OKA fish demonstrated evidence of learning and memory that strikingly resembled the control group. This shows that LKE, when concomitantly administered with OKA, is able to inhibit the cognitive impairment in zebrafish induced by OKA treatment. TUNEL assay results demonstrating a difference in the amount of cells undergoing apoptosis in the dorsal lateral pallium of OKA treated zebrafish versus LKE+OKA treated zebrafish supports the idea that LKE reduces OKA generated effects on the dorsal lateral pallium of the zebrafish. Not only did the OKA treated fish exhibit a higher fraction of apoptotic cells when compared to the LKE+OKA fish, but the LKE+OKA fish fraction of apoptotic cells resembled that of the control. The TUNEL assay analysis substantiates the spatial alternation paradigm data analysis. The observed TUNEL assay changes were done in the dorsal lateral pallium area of the zebrafish. The dorsal lateral pallium of the zebrafish is homologous to the mammalian hippocampus [11–13]. The hippocampus plays vital roles in forming long-term memories from short-term memory information, long-term-potentiation, and in spatial memory. AD manifests itself in the entorhinal cortex and the hippocampus and brain imaging analysis shows severe shrinking of the hippocampus in patients suffering from AD [25–27]. Therefore, it can be reasonably hypothesized that the improved cognitive function exhibited by the LKE+OKA treated fish is attributable to the decreased cell death in the dorsal lateral pallium of the LKE+OKA treated fish.

LKE is reported to be an effective protectant in several neurodegenerative disease models including 3× Tg-AD mouse modeling AD, permanent ischemia brain injury in mice, SOD1G93A mouse model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and an encephalomyelitis treated mice to model multiple sclerosis [6, 28–30]. However, its mechanism of action is not well understood. A proteomic study concluded that LK binds to 3 proteins selectively: Collapsin response mediator protein 2/dhydropyrimidinase-like protein 2 (CRMP2/DRP2/DPYSL2), syntaxin-binding protein (STXBP1/Munc18/nSec1), and lanthionine synthetase-like protein 1 (LanCL1) [7]. CRMP2, specifically, has been a central focus of investigation on how LKE is able to elicit its effects. CRMP2 has been an emerging target of discussion in regards to neurodegenerative diseases due to its role in axonal pathfinding and neuron polarization [31] and differential expression rates in disease states such as AD [32]. Therefore, most of the attributes or therapeutic benefits of LKE have been tied back to pCRMP2/CRMP2 in the literature. These investigations have determined an altered state of pCRMP2/CRMP2 expression after LKE intervention. However, it is possible that other partners of LKE exist. The previous proteomic analysis on LKE (mentioned above) would likely not have identified cell surface membrane receptors nor membrane associated proteins. Other brain protein binding partners could possibly exist that were not effectively canvassed by proteomics techniques thus far. Cell surface membrane receptors and strongly membrane associated proteins, in particular, likely would not have been identified in previous investigations [6]. Therefore, it is important to explore other potential mechanisms of action.

We were able to provide a possible mechanism behind the neuroprotective effects of LKE against OKA-induced neurodegeneration in the zebrafish. In the zebrafish group treated with OKA, LKE augmented the expression of the neurotrophic factor BDNF, the anti-apoptotic kinase pAkt (Ser473), and the transcription factor pCREB (Ser133). It is interesting to note that the levels of BDNF, pAkt, and pCREB were not significantly lowered in the OKA treated fish when compared to the control fish. This leads to the conclusion that LKE does not ameliorate OKA-induced neurodegeneration directly but rather through an indirect route. Several studies, including anecdotal evidence, show that LKE has the tendency to work better in systems under stress [33]. It is plausible, but needs to be further explored, that LKE has nootropic effects that act in a positive feedback loop when it is administered to a system that has been given an insult. This could be attributed to LKE being a derivative of the natural metabolite lanthionine ketimine, therefore, having minimal effects in a normal homeostatic state. This is corroborated by work done in 5 day old zebrafish exposed to up to 500μM LKE and no changes were observed (data not shown). In addition, a study of LKE and its neuroprotective qualities in an in vitro model of oxidative stress where LKE was given alone proved to have no effects [30].

Activation of neurotrophic signaling pathways promotes cognitive function through synapse formation, synaptic plasticity, neuronal survival, and neurogenesis [34, 35]. The investigation into neurotrophic pathways and their modulation in neurodegenerative diseases has been an increasing focal point as many other investigational leads have led to clinical failures, especially in combating AD.

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is a member of the neurotrophic family that promotes neuronal growth, differentiation, survival, regeneration, and repair by primarily interacting with tropmyosin receptor kinase B/tyrosine receptor kinase B (TrkB) [34–36]. This interaction stimulates the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-Akt pathway [37]. Akt, also known as protein kinase B, is a serine/threonine kinase that has a well-established role in numerous cellular functions including proliferation and survival. Akt activation is governed by phosphorylation at Ser473 and Thr308 which leads to Akt phosphorylating many subsequent downstream targets including the proapoptotic proteins BAD, MDM2, and caspase-9. The increase in pAkt (Ser473) seen in animals dosed with 500μM LKE + 100 nM OKA group is not attributed to OKA even though OKA is a PP2A inhibitor. PP2A dephosphorylates Thr308 while PH domain and leucine rich repeat protein phosphatases (PHLPP) dephosphorylate Ser473 of Akt [16, 17]. In addition, it was observed that OKA reduces the expression of pAkt (Ser473) in our studies which is consistent with other studies involving OKA and pAkt [38, 39].

The direct phosphorylation, by Akt, of BAD, MDM2, and caspase-9, negatively regulates their pro-apoptotic function leading to cellular survival [40]. Another important target of Akt is the transcription factor cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) which is phosphorylated at the Ser133 position [41]. Upon activation, CREB is able to promote neuron survival and long-term potentiation via regulating gene expression [18, 19]. Interestingly enough, CREB is able to regulate the expression of BDNF [42], suggesting that BDNF and CREB could be operating in a positive feedback loop.

Many reports state that the activation of BDNF/TrkB/CREB pathway enhances neuroprotection from multiple insults, especially within the hippocampus [19, 43–47]. We report that the expression levels of BDNF, pAkt (Ser473), and pCREB (Ser133) were all increased in the LKE+OKA treated fish. The activation of the BDNF/TrkB/CREB pathway by LKE reduced the cell death in the dorsal lateral pallium of the zebrafish which could lead to their normal cognitive function.

Highlights.

LKE rescued OKA-induced memory impairments.

LKE reduced OKA-induced cell death in the dorsal lateral pallium of the zebrafish.

Possible LKE mechanism of action is the activation of the BDNF/TrkB/CREB pathway.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Alexander Wisner and Kevin Nash for their intellectual support during the experimental set-up and data collection.

Funding: This work was supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NS093594, KH)

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

Analysis of Variance

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- NFT

Neurofibrillary tangles

- OKA

Okadaic acid

- PP1

Protein phosphatase 2

- PP2A

Protein phosphatase 2A

- LK

Lanthionine ketimine

- LKE

Lanthionine ketimine-5-ethyl-ester

- CRMP2

Collapsin response mediator protein 2

- BDNF

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- CREB

cAMP response element-binding protein

- PKB/Akt

Protein kinase B

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict(s) of interest: Dr. Hensley is inventor on a patent concerning composition and use of LKE for medical purposes, and holds equity in XoNovo Ltd., a company engaged in development of the compound.

References

- 1.De-Paula VJ, et al. Alzheimer’s disease. Subcell Biochem. 2012;65:329–52. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-5416-4_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xi Y, Noble S, Ekker M. Modeling neurodegeneration in zebrafish. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2011;11(3):274–82. doi: 10.1007/s11910-011-0182-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bialojan C, Takai A. Inhibitory effect of a marine-sponge toxin, okadaic acid, on protein phosphatases. Specificity and kinetics. Biochem J. 1988;256(1):283–90. doi: 10.1042/bj2560283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nada SE, Williams FE, Shah ZA. Development of a Novel and Robust Pharmacological Model of Okadaic Acid-induced Alzheimer’s Disease in Zebrafish. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2016;15(1):86–94. doi: 10.2174/1871527314666150821105602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooper AJ. The role of glutamine transaminase K (GTK) in sulfur and alpha-keto acid metabolism in the brain, and in the possible bioactivation of neurotoxicants. Neurochem Int. 2004;44(8):557–77. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hensley K, Venkova K, Christov A. Emerging biological importance of central nervous system lanthionines. Molecules. 2010;15(8):5581–94. doi: 10.3390/molecules15085581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hensley K, et al. Proteomic identification of binding partners for the brain metabolite lanthionine ketimine (LK) and documentation of LK effects on microglia and motoneuron cell cultures. J Neurosci. 2010;30(8):2979–88. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5247-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams FE, White D, Messer WS. A simple spatial alternation task for assessing memory function in zebrafish. Behav Processes. 2002;58(3):125–132. doi: 10.1016/s0376-6357(02)00025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Avdesh A, et al. Evaluation of color preference in zebrafish for learning and memory. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;28(2):459–69. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-110704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–54. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santana S, Rico EP, Burgos JS. Can zebrafish be used as animal model to study Alzheimer’s disease? Am J Neurodegener Dis. 2012;1(1):32–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng RK, Jesuthasan SJ, Penney TB. Zebrafish forebrain and temporal conditioning. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2014;369(1637):20120462. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bally-Cuif L, Vernier P. Organization and physiology of the zebrafish nervous system. In: Perry SF, et al., editors. Fish Physiology. Academic Press; 2010. pp. 25–80. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith LE, et al. Developmental selenomethionine and methylmercury exposures affect zebrafish learning. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2010;32(2):246–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong J. Neurotrophin Signaling and Alzheimer’s Disease Neurodegeneration – Focus on BDNF/TrkB Signali. In: Wislet-Gendebien S, editor. Trends in Cell Signaling Pathways in Neuronal Fate Decision. 2013. pp. 181–194. CC BY 3.0 license. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bayascas JR, Alessi DR. Regulation of Akt/PKB Ser473 phosphorylation. Mol Cell. 2005;18(2):143–5. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hemmings BA, Restuccia DF. PI3K-PKB/Akt pathway. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4(9):a011189. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a011189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mizuno M, et al. CREB phosphorylation as a molecular marker of memory processing in the hippocampus for spatial learning. Behav Brain Res. 2002;133(2):135–41. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00470-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walton MR, Dragunow I. Is CREB a key to neuronal survival? Trends Neurosci. 2000;23(2):48–53. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01500-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valdiglesias V, et al. Okadaic acid: more than a diarrheic toxin. Mar Drugs. 2013;11(11):4328–49. doi: 10.3390/md11114328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamat PK, et al. Okadaic acid (ICV) induced memory impairment in rats: a suitable experimental model to test anti-dementia activity. Brain Res. 2010;1309:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.10.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tunez I, et al. Protective melatonin effect on oxidative stress induced by okadaic acid into rat brain. J Pineal Res. 2003;34(4):265–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-079x.2003.00039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Z, Simpkins JW. An okadaic acid-induced model of tauopathy and cognitive deficiency. Brain Res. 2010;1359:233–46. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.08.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao L, et al. Original Research: Influence of okadaic acid on hyperphosphorylation of tau and nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in primary neurons. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2016;241(16):1825–33. doi: 10.1177/1535370216650759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bird CM, Burgess N. The hippocampus and memory: insights from spatial processing. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9(3):182–94. doi: 10.1038/nrn2335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bliss TV, Collingridge GL. A synaptic model of memory: long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Nature. 1993;361(6407):31–9. doi: 10.1038/361031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindberg O, et al. Hippocampal shape analysis in Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal lobar degeneration subtypes. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;30(2):355–65. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-112210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dupree JL, et al. Lanthionine ketimine ester provides benefit in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis. J Neurochem. 2015;134(2):302–14. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hensley K, et al. A derivative of the brain metabolite lanthionine ketimine improves cognition and diminishes pathology in the 3 × Tg-AD mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2013;72(10):955–69. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3182a74372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nada SE, et al. A derivative of the CRMP2 binding compound lanthionine ketimine provides neuroprotection in a mouse model of cerebral ischemia. Neurochem Int. 2012;61(8):1357–63. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2012.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goshima Y, et al. Collapsin-induced growth cone collapse mediated by an intracellular protein related to UNC-33. Nature. 1995;376(6540):509–14. doi: 10.1038/376509a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cole AR, et al. Collapsin response mediator protein-2 hyperphosphorylation is an early event in Alzheimer’s disease progression. J Neurochem. 2007;103(3):1132–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marangoni N, et al. Neuroprotective and neurotrophic effects of Lanthionine Ketimine Ester. Neurosci Lett. 2017;664:28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2017.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reichardt LF. Neurotrophin-regulated signalling pathways. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2006;361(1473):1545–64. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vilar M, Mira H. Regulation of Neurogenesis by Neurotrophins during Adulthood: Expected and Unexpected Roles. Front Neurosci. 2016;10:26. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2016.00026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Minichiello L. TrkB signalling pathways in LTP and learning. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10(12):850–60. doi: 10.1038/nrn2738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaplan DR, Miller FD. Neurotrophin signal transduction in the nervous system. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2000;10(3):381–91. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schubert KM, Scheid MP, Duronio V. Ceramide inhibits protein kinase B/Akt by promoting dephosphorylation of serine 473. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(18):13330–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.18.13330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benetti L, Roizman B. Protein kinase B/Akt is present in activated form throughout the entire replicative cycle of deltaU(S)3 mutant virus but only at early times after infection with wild-type herpes simplex virus 1. J Virol. 2006;80(7):3341–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.7.3341-3348.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Manning BD, Cantley LC. AKT/PKB signaling: navigating downstream. Cell. 2007;129(7):1261–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Du K, Montminy M. CREB is a regulatory target for the protein kinase Akt/PKB. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(49):32377–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tao X, et al. Ca2+ influx regulates BDNF transcription by a CREB family transcription factor-dependent mechanism. Neuron. 1998;20(4):709–26. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Almeida RD, et al. Neuroprotection by BDNF against glutamate-induced apoptotic cell death is mediated by ERK and PI3-kinase pathways. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12(10):1329–43. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bito H. A potential mechanism for long-term memory: CREB signaling between the synapse and the nucleus. Seikagaku. 1998;70(6):466–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hazra S, et al. Reversion of BDNF, Akt and CREB in Hippocampus of Chronic Unpredictable Stress Induced Rats: Effects of Phytochemical, Bacopa Monnieri. Psychiatry Investig. 2017;14(1):74–80. doi: 10.4306/pi.2017.14.1.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Silva AJ, et al. CREB and memory. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1998;21:127–48. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.21.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yoo JM, et al. Neuroprotective action of N-acetyl serotonin in oxidative stress-induced apoptosis through the activation of both TrkB/CREB/BDNF pathway and Akt/Nrf2/Antioxidant enzyme in neuronal cells. Redox Biol. 2017;11:592–599. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2016.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wullimann MF, Rupp B, Reichert H. Neuroanatomy of the Zebrafish Brain: A Topological Atlas. Birkhäuser Verlag; 1996. p. 27. [Google Scholar]