Abstract

Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) have unlimited expansion potential and the ability to differentiate into all somatic cell types for regenerative medicine and disease model studies. Octamer-binding transcription factor 4 (OCT4), encoded by the POU domain, class 5, transcription factor 1 gene, is a transcription factor vital for maintaining ESC pluripotency and somatic reprogramming. Many studies have established that the cell cycle of ESCs is featured with an abbreviated G1 phase and a prolonged S phase. Changes in cell cycle dynamics are intimately associated with the state of ESC pluripotency, and manipulating cell-cycle regulators could enable a controlled differentiation of ESCs. The present review focused primarily on the emerging roles of OCT4 in coordinating the cell cycle progression, the maintenance of pluripotency and the glycolytic metabolism in ESCs.

Keywords: embryonic stem cells, cell cycle, pluripotency, octamer-binding transcription factor 4, self-renewal, cell fate, glycolytic metabolism

1. Introduction

Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) are characterized by unlimited proliferation (self-renewal) and the ability to differentiate into three primary germ layers, namely the endoderm, mesoderm and ectoderm (pluripotency) (1–4). It has been established that complicated regulatory networks are present in ESCs that critically maintain the state of self-renewal and pluripotency for later development (5,6). Several transcription factors (TFs), including octamer-binding transcription factor 4 (OCT4), SRY-box 2 (SOX2) and homeobox protein NANOG (NANOG) are known to sit at the top of the regulatory hierarchy, regulating the expression of various downstream target genes (7,8). Among them, OCT4 serves an indispensable role in maintaining the pluripotency of ESCs (9,10) and in reprogramming the terminally-differentiated somatic cells back into the ESC-like cells (11–13). Furthermore, OCT4 can mediate the differentiation of murine ESCs induced by retinoic acid or Wnt/β-catenin in a manner that is independent of and distinct from other core TFs (14), indicating that OCT4 may have unique and non-substitutable roles in controlling the self-renewal, pluripotency and differentiation of ESCs.

Cell cycle progression is required for ESCs to proliferate and avoid staying in a quiescent state. Multiple studies have demonstrated that cell cycle-associated proteins can regulate various core TFs or differentiation markers (15). In a reciprocal manner, several TFs, such as NANOG and c-MYC proto-oncogene protein, can control the expression levels of multiple cell cycle-associated target genes (16,17). This review will be focused on reciprocal interplays between OCT4 and cell cycle checkpoints and their connections with the ESC pluripotency.

2. Cell cycle and pluripotency in ESCs

Cell cycle comprises four different phases; the S phase for DNA replication, the M phase for cell mitosis, and two gap phases between S phase and M phase (G1 phase for synthesis of proteins and lipids, and G2 phase for checking DNA integrity). Ample evidence has revealed that the duration of cell cycle in murine somatic cells is relatively long (>16 h), which is dominated by the G1 phase (18); in contrast, the cell cycle of murine ESCs progresses faster (~8–10 h) (19), which is characterized by a truncated G1 phase and a prolonged S phase (20). Although the duration of cell cycle in human ESCs is significantly lengthened (~32–38 h) (21), the time spent at G1 phase is minimal (3 h in human ESCs vs. 10 h in human somatic cells) (15,22), indicating that the cell cycle dynamics may crucially impact on the differentiation potential of pluripotent stem cells. Indeed, ~1–5% of the total proteins differ their expression levels between ESCs and induced pluripotent (iPS) cells, and the majority of them are cell cycle proteins (23).

There is mounting evidence demonstrating that lengthening the G1 phase in ESCs contributes to inducing differentiation (24–27), and distinct G1 phase profiles will lead to different lineage fates. Human ESCs in early G1 phase can only differentiate into endoderm, whereas in late G1 phase they were limited to neuroectodermal differentiation (28). In fact, all-trans retinoic acid, a common differentiation inducer, can regulate the gene expression of Cyclin D1 (29,30) and result in G1 phase accumulation (31–33). It is therefore reasonable to propose that during the G1 phase, ESCs sense and integrate various extracellular and intracellular signals to make the decisions on the timing and the fate of differentiation. A shortened G1 phase may minimize the exposure of ESCs to various signals, thereby preserving their pluripotency. In addition, it was demonstrated in a recent study that G2 cell cycle arrest is also required for endodermal development (34); furthermore, specific disruption of S and G2 phases will affect the pluripotent state of human ESCs in a G1 phase-independent way (35–37). Gamma-ray-induced DNA damage induces G2/M blockage and the differentiation of ESCs (38,39). It is important that ESCs have a long enough G2 phase to check and restore the fidelity of the genome as a result of G1/S checkpoint deficiency.

3. OCT4 and G1/S transition

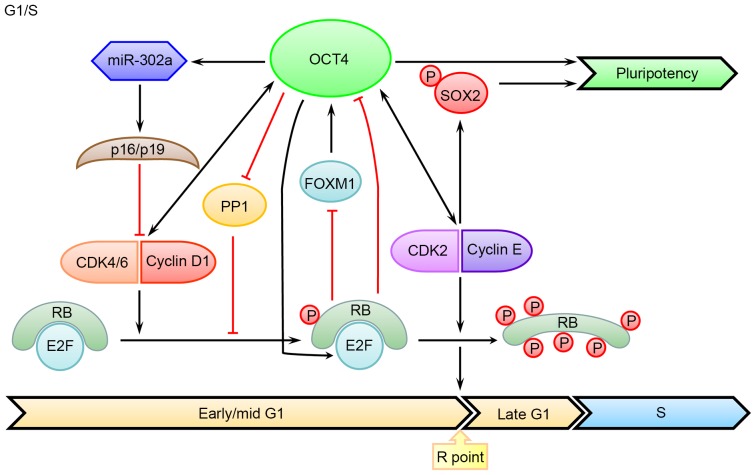

The expression of Cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 (CDK4/6) and Cyclin D is increased in early G1 phase in somatic cells. Although the lack of Cyclin D expression was reported in murine ESCs (40), the mRNA levels of CDK4 and Cyclin D2 were increased in human ESCs (22,41). Further studies demonstrated that Cyclin D expression is enhanced in late G1 and G1/S phases in human ESCs. Notably, knocking down Cyclin D induces endodermal differentiation, whereas its overexpression promoted neuroectodermal differentiation by inhibiting mothers against decapentaplegic (SMAD) 2/3 nuclear translocation (28). In addition, Cyclin D can also recruit transcriptional co-regulators to development-assocaited gene loci and modify the epigenetics of target genes (42). There is evidence demonstrating that a proper level of Cyclin D is necessary for maintaining the pluripotent state of ESCs, while overexpression of them may induce reprogramming of epidermal cells into stem-like cells with higher expression levels of OCT4 and NANOG (43). In contrast, in adult stem cells or cancer cells, OCT4 can directly bind to the promoter region of Cyclin D1, thereby regulating its transcription and controlling G1/S transition (44–46). Meanwhile, OCT4 can bind with the conserved promoter of microRNA (miR)-302 (47), increasing the level of p16(Ink4a)/p19(Ink4d) and inhibiting the interaction between CDK4/6 and Cyclin D (48). Furthermore, OCT4 can also interact with SMAD2/3 to control the pluripotent state of ESCs (49,50). Taken together, these studies suggested that OCT4 is involved in the transcriptional regulation of Cyclin D as well as other target genes (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

An overview of the roles of OCT4 in coordinating the G1/S transition and the maintenance of pluripotency. OCT4 promotes the phosphorylation of hypo-phosphorylated RB (a prerequisite for the R-point transition) by downregulating PP1 and upregulating CDK4/6-Cyclin D in early and mid G1 phase. At this point, phosphorylated RB still binds to E2Fs and blocks their transcription-activating domains, leading to suppressed expression of several cell-cycle promoting genes, including OCT4. OCT4 can further promote RB hyperphosphorylation by upregulating CDK2-Cyclin E complex, which leads to the E2F release, the R-point transition, and the entry into the S phase. CDK2 can also phosphorylate SOX2 to enhance reprogramming efficiency. Black arrows indicate positive regulation, while red bar-headed lines indicate negative regulation. PP1, protein phosphatase 1; CDK, cyclin-dependent kinase; FOXM1, forkhead box protein M1; RB, retinoblastoma; E2F, E2F transcription factor 1; OCT4, octamer-binding transcription factor 4; p, phosphorylated.

CDK2-Cyclin E is constitutively expressed and involved in the progression of G1/S transition (26). In human ESCs, inhibition of CDK2 will lead to G1 phase arrest, which is accompanied with apoptosis or differentiation. Inhibition of CDK2 can induce sustained genomic damage and elicit DNA damage response, thus contributing to apoptosis of impaired ESCs (51,52). As demonstrated in further studies, OCT4 expression can be suppressed by downregulating CDK2 (53,54), while CDK2 can enhance reprogramming efficiency by phosphorylating SOX2 at Ser-39 and Ser-253 sites (55). Although the regulation of CDK2-Cyclin A/E by OCT4 in ESCs has not been reported, OCT4 can promote tumor proliferation by activating Cyclin E (56). Thus, it remains possible that OCT4 may regulate the expression of CDK2-Cyclin A/E in ESCs.

Retinoblastoma (RB) protein is a downstream target of CDK4/6-Cyclin D, which can inhibit the transcription activity of E2F transcription factor 1 (E2F) in its hypophosphorylated state. After being hyperphosphorylated by CDK2-Cyclin E, RB can release E2F for the ultimate regulation of a number of targets involved in G1 phase progression and S phase entry (Fig. 1). Therefore, it came as no surprise that the activity of RB-E2F can influence the ESC self-renewal and pluripotency (57,58). In fact, activated RB can directly bind to the promoter regions of OCT4 and SOX2, leading to their transcriptional suppression and a declined reprogramming efficiency (59); in contrast, the inactive RB allows for generation of iPS cells in the absence of exogenous SOX2 expression (60). Furthermore, RB can also regulate OCT4 level by suppressing the expression of forkhead box protein M1, which is a transcription factor promoting OCT4 expression (61,62). In addition, E2f will switch from an active state in stem cells to a suppressed state in differentiated cells through forming a complex with RB (63). Conversely, in murine ESCs, OCT4 maintains the hypo-phosphorylated state of RB by inhibiting the activity of protein phosphatase 1 (64), which is well-known for its role in triggering mitotic exit (65). Additionally, OCT4 can also directly bind to the promoter region of E2f3a and increase its expression level in murine ESCs, which contributes to relieving the cell growth retardation caused by OCT4 knockdown (66). As inhibition of E2F2 can impair self-renewal and cell cycle progression in human ESCs, the pluripotency is preserved in E2F2 silencing cells (67). Therefore, the effects of RB on the pluripotency of ESCs are unlikely mediated by E2F. The other roles of RB in ESCs will be discussed later.

4. OCT4 and G2/M transition

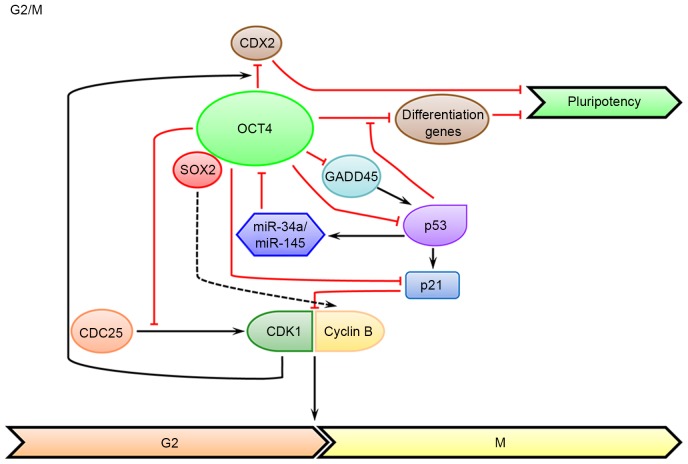

In somatic cells, CDK1-Cyclin A/B is a critical cell cycle regulator that can promote G2/M transition. As has been demonstrated in multiple studies, CDK1-Cyclins serve critical roles in the self-renewal and development of ESCs. The expression level of Cyclin A, the first cloned Cyclin protein, is higher in ESCs in G2 phase than that in fibroblast cells (68), and resetting its expression level in early-passage iPS cells can improve the pluripotency and reduce the tumorigenicity (23). In addition, the Cyclin B1 level is also upregulated in ESCs in G2 phase compared with that in somatic cells. Increased expression of Cyclin B1 in G2 phase can delay the dissolution of pluripotent state in human ESCs, while knockdown of Cyclin B1 induces markedly declined expression of pluripotent markers in human ESCs (36). The same is true for CDK1. In human ESCs, down-regulating CDK1 leads to loss of pluripotency, increased differentiation markers, accumulation of double-strand breaks, as well as the inability to arrest at G2 phase and commit to apoptosis (69,70). CDK1 can enhance the binding of OCT4 to the promoter and suppress the transcription of homeobox protein CDX2, a classic differentiation marker (71). Furthermore, several markers of G2/M are expressed during the meso- and endodermal differentiation (e.g., WEE1 G2 checkpoint kinase blocks entry into mitosis by phosphorylating CDK1 at Y15), rather than the ectodermal differentiation (34). In contrast, OCT4 can inhibit the activation of CDK1 by cell division cycle 25 phosphorylation, which is independent of its transcriptional activity (Fig. 2). Thus, ESCs have to express more CDK1 to overcome the inhibitory effect of OCT4. Inhibition of CDK1 by OCT4 will lead to a prolonged duration of G2 phase, which allows for subsequent checking of genome integrity and reducing chromosomal mis-segregation (72). Indeed, inhibition of CDK1 can activate the response to DNA damage and promote nuclear translocation and activation of p53, thereby maintaining the survival of ESCs (73). The potential connection between OCT4 and Cyclin A/B has not been elucidated in any study yet, but there is evidence that SOX2, a core TF frequently associated with OCT4, can promote the expression of Cyclin A/B in cancer cells (74–76). The direct regulation of CDK1-Cyclin by OCT4 warrants further investigation.

Figure 2.

An overview of the roles of OCT4 in coordinating the G2/M transition and the maintenance of pluripotency. At the G2/M phase, via a non-transcriptional mechanism, OCT4 can inhibit the activation of CDK1 and lead to a prolonged G2 phase, allowing for subsequent checking of genome integrity and reducing chromosomal mis-segregation. Reciprocally, CDK1 can enhance the binding of OCT4 to the CDX2 promoter and suppress its transcription, contributing to the maintenance of ESC pluripotency. Black arrows indicate positive regulation, while red bar-headed lines indicate negative regulation. CDX2, homeobox protein CDX2; CDC25, cell cycle division 25; miR, microRNA; CDK1, cyclin-dependent kinase 1; GADD45, DNA-damage-inducible protein 45; SOX2, SRY-box 2; OCT4, octamer-binding transcription factor 4.

Growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible protein 45 (GADD45), which includes several isoforms, is crucial for protecting genome stability in G2/M transition by suppressing cell cycle and repairing DNA. GADD45ag morpholino knockdown in Xenopus can induce differentiation of neural embryonic cells by inducing various cell cycle related inhibitors, such as p53, p21 and Cyclin G1. Additionally, GADD45ag morphants exhibit increased expression of Xenopus OCT4 homologs, indicating that GADD45ag is required for early embryonic cells to exit pluripotency and enter differentiation (77). In addition, GADD45a can bind to the OCT4 promoter and promote its demethylation in Xenopus oocytes, which is accompanied with DNA repair (78,79). Furthermore, studies in human cells indicated that GADD45 G is a downstream target of OCT4, which is significantly increased in the OCT4 knockdown system (80,81).

As discussed above, RB is a tumor-suppressor gene controlling the activity of transcription factor of E2F family, which serves an indispensable role in G1/S transition. Increased activity of RB can trigger cell cycle arrest, differentiation or death of ESCs (82). However, the inactivation of RB family in ESCs can also induce G2/M arrest and cell death (57), which may be attributed to the loss of its function in maintaining the genetic stability (83–85). These findings indicated that the expression level of RB needs to be tightly controlled at a proper level, so that the pluripotency and self-renewal of ESCs can be maintained. Furthermore, overexpression of RB in S phase can lead to G2 phase arrest (86). Additionally, RB can directly bind to cohesin and condensin II, which can regulate centromere functions and control mitosis (87–91).

5. OCT4 and p53-p21 checkpoints

The p53-p21 signaling pathway is a major checkpoint in cell cycle of G1/S and G2/M transition. The expression level of p53 is kept low in ESCs, which is predominantly present in the cytoplasm. The extremely low level of p53 in the nucleus is also inactivated. p53 will translocate to cell nucleus and initiate the transcription of its target genes in the event of DNA damage (92). In addition, p53 can promote the translocation of active Bcl-2-associated X protein from the Golgi to mitochondria to initiate apoptosis under DNA damage stresses (93). It is demonstrated that p53 deficiency will lead to genomic instability in ESCs (94). In contrast, the activated p53 in ESCs will result in differentiation (31,95,96) or apoptosis (73,97). However, it has also been demonstrated in other studies that p53 has anti-differentiation effects in ESCs (98), indicating that p53 exerts its functions in a context-dependent manner, and that proper intracellular levels and subcellular localization of p53 are critical for its roles in maintaining the pluripotent state in ESCs.

In addition, p53 can regulate the expression of various key TFs in ESCs. For example, knockdown of p53 can lead to downregulated NANOG expression (99). As a common differentiation inducer of ESCs, p53 expression is activated after exposure to retinoic acid, which drives the expression of miR-34a and miR-145 and reduces the OCT4 expression (31). In addition, the differentiation-activated p53 can recruit UTX and lysine-specific demethylase 6B (JMJD3), the H3K27me3-specific demethylases, bind to the promoter regions of developmental transcription factors that are repressed by OCT4, and increase the expression of various differentiation genes (100). p53 is also the downstream target of OCT4 (Fig. 2). Studies have revealed that silencing OCT4 will lead to p53 activation and induce differentiation (101–103). For instance, silencing OCT4 significantly reduces the expression of SIRT1, a deacetylase known to inhibit p53 activity and the differentiation of ESCs, leading to increased acetylation of p53 at lysine 120 and 164 that is required for its stabilization and functionality (104). In addition, OCT4 can bind to the promoter region of CD49f (integrin subunit α6), which can also decrease the level of p53 (105).

p21, a downstream target of p53, can inhibit the activation of CDKs and result in cell cycle arrest (Fig. 2); in addition, it can also be regulated in a p53-independent way. It has been revealed in studies that p21 is involved in DNA repair, transcriptional regulation, differentiation and apoptosis. In ESCs, the expression level of p21 is compromised due to epigenetic modification (106), and the lack of p21 function is required for maintaining the pluripotent state (107). Ionizing radiation-induced DNA damage can lead to elevated p21 mRNA level and cell cycle arrest at G2 phase (108). Upregulation of p21 in human ESCs will induce G1 phase arrest and subsequent differentiation into multiple lineages (109). This result is consistent with the finding that p21 has multiple fuctions in both G1/S and G2/M checkpoints (110,111). p21 can also mediate apoptosis in murine ESCs that are exposed to dihydrolipoic acid (112). In addition, increased p21 expression leads to decreased reprogramming efficiency in somatic cells (113). Conversely, OCT4 can inhibit the activity of p21 by directly binding to its promoter region or by indirectly up-regulating DNA (cytosine-5)-methyltransferase 1, a DNA methyltransferase, which can inhibit lineage differentiation (114–116).

6. OCT4 and ESC metabolism

A large amount of energy is generated in ESCs to meet the requirements for biosynthesis and cell cycle progression. The energy metabolism mode of primed ESCs is similar to that of other adult stem cells or cancer cells with a high glycolytic flux rather than oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), which is known as the ‘Warburg effect’ (117–121). This phenomenon can be partly attributed to the immature structure and function of mitochondria and a hypoxic niche (5% of physiological level) (122,123). Though glycolysis produces less ATPs than OXPHOS, it has faster rate of ATP generation, which makes it competent to support active cell proliferation. Additionally, pyruvate, the product of glycolysis, together with other intermediate products of tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, can be used for biosynthesis (such as DNA, protein and lipid) in ESCs as well as in cancer cells for shortening the G1 phase (123–125). A high glycolytic flux metabolism in hypoxia may reduce the damages to DNA caused by reactive oxide species (ROS), which may impair the pluripotency ESCs and induce their differentiation (126,127).

Initial evidence indicated OCT4 may be involved in regulating metabolism as its knockdown resulted in increases in TCA cycle activity and decreases in glycolytic flux (117). Further studies demonstrated that OCT4 can directly regulate the transcription of hexokinase 2 (HK2) and pyruvate kinase (PK) M2, the two key glycolytic enzymes that determine the rate of glycolysis. Overexpression of HK2 and PKM2 contributes to sustaining the high glycolysis level and preserving the pluripotency of ESCs (128). Notably, PKM2 can directly bind to OCT4 and enhance OCT4-mediated transcription (129,130).

7. Conclusion

It has been known for a while that ESCs are characterized by an abbreviated G1 phase and a prolonged S phase. However, the underlying mechanisms remain largely elusive. Emerging evidence has implicated a direct role of the master pluripotency factor OCT4 in controlling the transcription of several key cell cycle regulators. In general, OCT4 appears to directly or indirectly activate the transcription of cell cycle machineries that promote G1/S transition and avoid differentiation (Fig. 1). Meanwhile, by suppressing multiple cell cycle genes, OCT4 controls proper duration of G2 phase to ensure the genomic integrity via both the transcription-dependent and -independent mechanisms (Fig. 2). Reciprocally, the cell cycle regulators especially CDK1 can directly interact with OCT4 and promote its suppressive binding to the differentiation genes and thereby maintaining the ESC pluripotency.

Another important feature of ESCs is their high glycolytic metabolism under hypoxic conditions that may minimize the oxidative damage of ROS to genetic material. Recent studies revealed that OCT4 can promote glycolysis by transcriptionally upregulating the expression of several key glycolytic enzymes, directly linking ESC metabolism to their self-renewal and pluripotency. Given the convergence of ESC pluripotency and cell cycle control on OCT4, it would be of interest to investigate in future studies how OCT4 and other master pluripotency factors coordinate ESC metabolism with their cell cycle progression.

The rapid cell cycle progression of ESCs requires high-fidelity DNA replication and repair mechanisms. The investigation into the potential connection between ESC cell cycle control and DNA replication/repair is just at its infancy, and it remains to be seen if the master pluripotency factors such as OCT4 may also serve a role in these events.

Acknowledgements

The present review was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant no. 2016YFA0100303) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 31601103).

References

- 1.Wu J, Belmonte JC Izpisua. Dynamic pluripotent stem cell states and their applications. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;17:509–525. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith AG. Embryo-derived stem cells: Of mice and men. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2001;17:435–462. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, Waknitz MA, Swiergiel JJ, Marshall VS, Jones JM. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282:1145–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin GR. Isolation of a pluripotent cell line from early mouse embryos cultured in medium conditioned by teratocarcinoma stem cells; Proc Natl Acad Sci USA; 1981; pp. 7634–7638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yousefi M, Hajihoseini V, Jung W, Hosseinpour B, Rassouli H, Lee B, Baharvand H, Lee K, Salekdeh GH. Embryonic stem cell interactomics: The beginning of a long road to biological function. Stem Cell Rev. 2012;8:1138–1154. doi: 10.1007/s12015-012-9400-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang L, Chen YG. Signaling control of differentiation of embryonic stem cells toward mesendoderm. J Mol Biol. 2016;428:1409–1422. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martello G, Smith A. The nature of embryonic stem cells. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2014;30:647–675. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100913-013116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Das S, Levasseur D. Transcriptional regulatory mechanisms that govern embryonic stem cell fate. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;1029:191–203. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-478-4_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nichols J, Zevnik B, Anastassiadis K, Niwa H, Klewe-Nebenius D, Chambers I, Schöler H, Smith A. Formation of pluripotent stem cells in the mammalian embryo depends on the POU transcription factor Oct4. Cell. 1998;95:379–391. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81769-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niwa H, Miyazaki J, Smith AG. Quantitative expression of Oct-3/4 defines differentiation, dedifferentiation or self-renewal of ES cells. Nat Genet. 2000;24:372–376. doi: 10.1038/74199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu T, Wang H, He J, Kang L, Jiang Y, Liu J, Zhang Y, Kou Z, Liu L, Zhang X, Gao S. Reprogramming of trophoblast stem cells into pluripotent stem cells by Oct4. Stem Cells. 2011;29:755–763. doi: 10.1002/stem.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsai SY, Bouwman BA, Ang YS, Kim SJ, Lee DF, Lemischka IR, Rendl M. Single transcription factor reprogramming of hair follicle dermal papilla cells to induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells. 2011;29:964–971. doi: 10.1002/stem.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simandi Z, Horvath A, Wright LC, Cuaranta-Monroy I, De Luca I, Karolyi K, Sauer S, Deleuze JF, Gudas LJ, Cowley SM, Nagy L. OCT4 Acts as an integrator of pluripotency and signal-induced differentiation. Mol Cell. 2016;63:647–661. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kareta MS, Sage J, Wernig M. Crosstalk between stem cell and cell cycle machineries. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2015;37:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bretones G, Delgado MD, León J. Myc and cell cycle control. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1849:506–516. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang X, Neganova I, Przyborski S, Yang C, Cooke M, Atkinson SP, Anyfantis G, Fenyk S, Keith WN, Hoare SF, et al. A role for NANOG in G1 to S transition in human embryonic stem cells through direct binding of CDK6 and CDC25A. J Cell Biol. 2009;184:67–82. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200801009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.White J, Stead E, Faast R, Conn S, Cartwright P, Dalton S. Developmental activation of the Rb-E2F pathway and establishment of cell cycle-regulated cyclin-dependent kinase activity during embryonic stem cell differentiation. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:2018–2027. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-12-1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stead E, White J, Faast R, Conn S, Goldstone S, Rathjen J, Dhingra U, Rathjen P, Walker D, Dalton S. Pluripotent cell division cycles are driven by ectopic Cdk2, cyclin A/E and E2F activities. Oncogene. 2002;21:8320–8333. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh AM, Dalton S. The cell cycle and Myc intersect with mechanisms that regulate pluripotency and reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ohtsuka S, Dalton S. Molecular and biological properties of pluripotent embryonic stem cells. Gene Ther. 2008;15:74–81. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3303065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Becker KA, Ghule PN, Therrien JA, Lian JB, Stein JL, van Wijnen AJ, Stein GS. Self-renewal of human embryonic stem cells is supported by a shortened G1 cell cycle phase. J Cell Physiol. 2006;209:883–893. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McLenachan S, Menchón C, Raya A, Consiglio A, Edel MJ. Cyclin A1 is essential for setting the pluripotent state and reducing tumorigenicity of induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21:2891–2899. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sela Y, Molotski N, Golan S, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Soen Y. Human embryonic stem cells exhibit increased propensity to differentiate during the G1 phase prior to phosphorylation of retinoblastoma protein. Stem Cells. 2012;30:1097–1108. doi: 10.1002/stem.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Calder A, Roth-Albin I, Bhatia S, Pilquil C, Lee JH, Bhatia M, Levadoux-Martin M, McNicol J, Russell J, Collins T, Draper JS. Lengthened G1 phase indicates differentiation status in human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22:279–295. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Filipczyk AA, Laslett AL, Mummery C, Pera MF. Differentiation is coupled to changes in the cell cycle regulatory apparatus of human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cell Res. 2007;1:45–60. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coronado D, Godet M, Bourillot PY, Tapponnier Y, Bernat A, Petit M, Afanassieff M, Markossian S, Malashicheva A, Iacone R, et al. A short G1 phase is an intrinsic determinant of naïve embryonic stem cell pluripotency. Stem Cell Res. 2013;10:118–131. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pauklin S, Vallier L. The cell-cycle state of stem cells determines cell fate propensity. Cell. 2013;155:135–147. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Delacroix L, Moutier E, Altobelli G, Legras S, Poch O, Choukrallah MA, Bertin I, Jost B, Davidson I. Cell-specific interaction of retinoic acid receptors with target genes in mouse embryonic fibroblasts and embryonic stem cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:231–244. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00756-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jirmanova L, Afanassieff M, Gobert-Gosse S, Markossian S, Savatier P. Differential contributions of ERK and PI3-kinase to the regulation of cyclin D1 expression and to the control of the G1/S transition in mouse embryonic stem cells. Oncogene. 2002;21:5515–5528. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jain AK, Allton K, Iacovino M, Mahen E, Milczarek RJ, Zwaka TP, Kyba M, Barton MC. p53 regulates cell cycle and microRNAs to promote differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. PLoS Biol. 2012;10:e1001268. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giuliano CJ, Kerley-Hamilton JS, Bee T, Freemantle SJ, Manickaratnam R, Dmitrovsky E, Spinella MJ. Retinoic acid represses a cassette of candidate pluripotency chromosome 12p genes during induced loss of human embryonal carcinoma tumorigenicity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1731:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu YY, Tachiki KH, Brent GA. A targeted thyroid hormone receptor alpha gene dominant-negative mutation (P398H) selectively impairs gene expression in differentiated embryonic stem cells. Endocrinology. 2002;143:2664–2672. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.7.8906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Oudenhove JJ, Grandy RA, Ghule PN, Del Rio R, Lian JB, Stein JL, Zaidi SK, Stein GS. Lineage-specific early differentiation of human embryonic stem cells requires a G2 cell cycle pause. Stem Cells. 2016;34:1765–1775. doi: 10.1002/stem.2352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gonzales KA, Liang H. Transcriptomic profiling of human embryonic stem cells upon cell cycle manipulation during pluripotent state dissolution. Genom Data. 2015;6:118–119. doi: 10.1016/j.gdata.2015.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gonzales KA, Liang H, Lim YS, Chan YS, Yeo JC, Tan CP, Gao B, Le B, Tan ZY, Low KY, et al. Deterministic restriction on pluripotent state dissolution by cell-cycle pathways. Cell. 2015;162:564–579. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Islam MS, Stemig ME, Takahashi Y, Hui SK. Radiation response of mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow and human pluripotent stem cells. J Radiat Res. 2015;56:269–277. doi: 10.1093/jrr/rru098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rebuzzini P, Pignalosa D, Mazzini G, Di Liberto R, Coppola A, Terranova N, Magni P, Redi CA, Zuccotti M, Garagna S. Mouse embryonic stem cells that survive γ-rays exposure maintain pluripotent differentiation potential and genome stability. J Cell Physiol. 2012;227:1242–1249. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rebuzzini P, Fassina L, Mulas F, Bellazzi R, Redi CA, Di Liberto R, Magenes G, Adjaye J, Zuccotti M, Garagna S. Mouse embryonic stem cells irradiated with γ-rays differentiate into cardiomyocytes but with altered contractile properties. Mutat Res. 2013;756:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fluckiger AC, Marcy G, Marchand M, Négre D, Cosset FL, Mitalipov S, Wolf D, Savatier P, Dehay C. Cell cycle features of primate embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2006;24:547–556. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Becker KA, Stein JL, Lian JB, van Wijnen AJ, Stein GS. Establishment of histone gene regulation and cell cycle checkpoint control in human embryonic stem cells. J Cell Physiol. 2007;210:517–526. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pauklin S, Madrigal P, Bertero A, Vallier L. Initiation of stem cell differentiation involves cell cycle-dependent regulation of developmental genes by Cyclin D. Genes Dev. 2016;30:421–433. doi: 10.1101/gad.271452.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao A, Yang L, Ma K, Sun M, Li L, Huang J, Li Y, Zhang C, Li H, Fu X. Overexpression of cyclin D1 induces the reprogramming of differentiated epidermal cells into stem cell-like cells. Cell Cycle. 2016;15:644–653. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2016.1146838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Su C. Survivin in survival of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2016;379:184–190. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bai M, Yuan M, Liao H, Chen J, Xie B, Yan D, Xi X, Xu X, Zhang Z, Feng Y. OCT4 pseudogene 5 upregulates OCT4 expression to promote proliferation by competing with miR-145 in endometrial carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2015;33:1745–1752. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.3763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Han SM, Han SH, Coh YR, Jang G, Ra J Chan, Kang SK, Lee HW, Youn HY. Enhanced proliferation and differentiation of Oct4- and Sox2-overexpressing human adipose tissue mesenchymal stem cells. Exp Mol Med. 2014;46:e101. doi: 10.1038/emm.2014.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Card DA, Hebbar PB, Li L, Trotter KW, Komatsu Y, Mishina Y, Archer TK. Oct4/Sox2-regulated miR-302 targets cyclin D1 in human embryonic stem cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:6426–6438. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00359-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lin SL, Ying SY. Mechanism and method for generating tumor-free iPS cells using intronic microRNA miR-302 induction. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;936:295–312. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-541-5_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sun LT, Yamaguchi S, Hirano K, Ichisaka T, Kuroda T, Tada T. Nanog co-regulated by Nodal/Smad2 and Oct4 is required for pluripotency in developing mouse epiblast. Dev Biol. 2014;392:182–192. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li P, Ma X, Adams IR, Yuan P. A tight control of Rif1 by Oct4 and Smad3 is critical for mouse embryonic stem cell stability. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6:e1588. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Neganova I, Vilella F, Atkinson SP, Lloret M, Passos JF, von Zglinicki T, O'Connor JE, Burks D, Jones R, Armstrong L, Lako M. An important role for CDK2 in G1 to S checkpoint activation and DNA damage response in human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2011;29:651–659. doi: 10.1002/stem.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bárta T, Vinarský V, Holubcová Z, Dolezalová D, Verner J, Pospísilová S, Dvorák P, Hampl A. Human embryonic stem cells are capable of executing G1/S checkpoint activation. Stem Cells. 2010;28:1143–1152. doi: 10.1002/stem.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Deshpande AM, Dai YS, Kim Y, Kim J, Kimlin L, Gao K, Wong DT. Cdk2ap1 is required for epigenetic silencing of Oct4 during murine embryonic stem cell differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:6043–6047. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C800158200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kallas A, Pook M, Trei A, Maimets T. Assessment of the potential of CDK2 inhibitor NU6140 to influence the expression of pluripotency markers NANOG, OCT4, and SOX2 in 2102Ep and H9 cells. Int J Cell Biol. 2014;2014:280638. doi: 10.1155/2014/280638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ouyang J, Yu W, Liu J, Zhang N, Florens L, Chen J, Liu H, Washburn M, Pei D, Xie T. Cyclin-dependent kinase-mediated Sox2 phosphorylation enhances the ability of Sox2 to establish the pluripotent state. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:22782–22794. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.658195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Koo BS, Lee SH, Kim JM, Huang S, Kim SH, Rho YS, Bae WJ, Kang HJ, Kim YS, Moon JH, Lim YC. Oct4 is a critical regulator of stemness in head and neck squamous carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2015;34:2317–2324. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Conklin JF, Baker J, Sage J. The RB family is required for the self-renewal and survival of human embryonic stem cells. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1244. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tsai SY, Opavsky R, Sharma N, Wu L, Naidu S, Nolan E, Feria-Arias E, Timmers C, Opavska J, de Bruin A, et al. Mouse development with a single E2F activator. Nature. 2008;454:1137–1141. doi: 10.1038/nature07066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kareta MS, Gorges LL, Hafeez S, Benayoun BA, Marro S, Zmoos AF, Cecchini MJ, Spacek D, Batista LF, O'Brien M, et al. Inhibition of pluripotency networks by the Rb tumor suppressor restricts reprogramming and tumorigenesis. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16:39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vilas JM, Ferreirós A, Carneiro C, Morey L, Da Silva-Álvarez S, Fernandes T, Abad M, Di Croce L, García-Caballero T, Serrano M, et al. Transcriptional regulation of Sox2 by the retinoblastoma family of pocket proteins. Oncotarget. 2015;6:2992–3002. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kelleher FC, O'Sullivan H. FOXM1 in sarcoma: Role in cell cycle, pluripotency genes and stem cell pathways. Oncotarget. 2016;7:42792–42804. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wierstra I, Alves J. Transcription factor FOXM1c is repressed by RB and activated by cyclin D1/Cdk4. Biol Chem. 2006;387:949–962. doi: 10.1515/BC.2006.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chong JL, Wenzel PL, Sáenz-Robles MT, Nair V, Ferrey A, Hagan JP, Gomez YM, Sharma N, Chen HZ, Ouseph M, et al. E2f1-3 switch from activators in progenitor cells to repressors in differentiating cells. Nature. 2009;462:930–934. doi: 10.1038/nature08677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schoeftner S, Scarola M, Comisso E, Schneider C, Benetti R. An Oct4-pRb axis, controlled by MiR-335, integrates stem cell self-renewal and cell cycle control. Stem Cells. 2013;31:717–728. doi: 10.1002/stem.1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Doonan JH, Morris NR. The bimG gene of Aspergillus nidulans, required for completion of anaphase, encodes a homolog of mammalian phosphoprotein phosphatase 1. Cell. 1989;57:987–996. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90337-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kanai D, Ueda A, Akagi T, Yokota T, Koide H. Oct3/4 directly regulates expression of E2F3a in mouse embryonic stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;459:374–378. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.02.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Suzuki DE, Nakahata AM, Okamoto OK. Knockdown of E2F2 inhibits tumorigenicity, but preserves stemness of human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2014;23:1266–1274. doi: 10.1089/scd.2013.0592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kalaszczynska I, Geng Y, Iino T, Mizuno S, Choi Y, Kondratiuk I, Silver DP, Wolgemuth DJ, Akashi K, Sicinski P. Cyclin A is redundant in fibroblasts but essential in hematopoietic and embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2009;138:352–365. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Neganova I, Tilgner K, Buskin A, Paraskevopoulou I, Atkinson SP, Peberdy D, Passos JF, Lako M. CDK1 plays an important role in the maintenance of pluripotency and genomic stability in human pluripotent stem cells. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1508. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Van Hoof D, Muñoz J, Braam SR, Pinkse MW, Linding R, Heck AJ, Mummery CL, Krijgsveld J. Phosphorylation dynamics during early differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:214–226. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li L, Wang J, Hou J, Wu Z, Zhuang Y, Lu M, Zhang Y, Zhou X, Li Z, Xiao W, Zhang W. Cdk1 interplays with Oct4 to repress differentiation of embryonic stem cells into trophectoderm. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:4100–4107. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhao R, Deibler RW, Lerou PH, Ballabeni A, Heffner GC, Cahan P, Unternaehrer JJ, Kirschner MW, Daley GQ. A nontranscriptional role for Oct4 in the regulation of mitotic entry; Proc Natl Acad Sci USA; 2014; pp. 15768–15773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Huskey NE, Guo T, Evason KJ, Momcilovic O, Pardo D, Creasman KJ, Judson RL, Blelloch R, Oakes SA, Hebrok M, Goga A. CDK1 inhibition targets the p53-NOXA-MCL1 axis, selectively kills embryonic stem cells, and prevents teratoma formation. Stem Cell Reports. 2015;4:374–389. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lee SH, Oh SY, Do SI, Lee HJ, Kang HJ, Rho YS, Bae WJ, Lim YC. SOX2 regulates self-renewal and tumorigenicity of stem-like cells of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2014;111:2122–2130. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tompkins DH, Besnard V, Lange AW, Keiser AR, Wert SE, Bruno MD, Whitsett JA. Sox2 activates cell proliferation and differentiation in the respiratory epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;45:101–110. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0149OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hou Z, Zhao W, Zhou J, Shen L, Zhan P, Xu C, Chang C, Bi H, Zou J4, Yao X, et al. A long noncoding RNA Sox2ot regulates lung cancer cell proliferation and is a prognostic indicator of poor survival. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2014;53:380–388. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kaufmann LT, Niehrs C. Gadd45a and Gadd45g regulate neural development and exit from pluripotency in Xenopus. Mech Dev. 2011;128:401–411. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Barreto G, Schäfer A, Marhold J, Stach D, Swaminathan SK, Handa V, Döderlein G, Maltry N, Wu W, Lyko F, Niehrs C. Gadd45a promotes epigenetic gene activation by repair-mediated DNA demethylation. Nature. 2007;445:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nature05515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schäfer A, Schomacher L, Barreto G, Döderlein G, Niehrs C. Gemcitabine functions epigenetically by inhibiting repair mediated DNA demethylation. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14060. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Awe JP, Crespo AV, Li Y, Kiledjian M, Byrne JA. BAY11 enhances OCT4 synthetic mRNA expression in adult human skin cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2013;4:15. doi: 10.1186/scrt163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jung M, Peterson H, Chavez L, Kahlem P, Lehrach H, Vilo J, Adjaye J. A data integration approach to mapping OCT4 gene regulatory networks operative in embryonic stem cells and embryonal carcinoma cells. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10709. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mushtaq M, Gaza HV, Kashuba EV. Role of the RB-interacting proteins in stem cell biology. Adv Cancer Res. 2016;131:133–157. doi: 10.1016/bs.acr.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zheng L, Flesken-Nikitin A, Chen PL, Lee WH. Deficiency of Retinoblastoma gene in mouse embryonic stem cells leads to genetic instability. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2498–2502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Eguchi T, Takaki T, Itadani H, Kotani H. RB silencing compromises the DNA damage-induced G2/M checkpoint and causes deregulated expression of the ECT2 oncogene. Oncogene. 2007;26:509–520. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.van Harn T, Foijer F, van Vugt M, Banerjee R, Yang F, Oostra A, Joenje H, te Riele H. Loss of Rb proteins causes genomic instability in the absence of mitogenic signaling. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1377–1388. doi: 10.1101/gad.580710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Karantza V, Maroo A, Fay D, Sedivy JM. Overproduction of Rb protein after the G1/S boundary causes G2 arrest. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:6640–6652. doi: 10.1128/MCB.13.11.6640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sage J, Straight AF. RB's original CIN? Genes Dev. 2010;24:1329–1333. doi: 10.1101/gad.1948010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kagey MH, Newman JJ, Bilodeau S, Zhan Y, Orlando DA, van Berkum NL, Ebmeier CC, Goossens J, Rahl PB, Levine SS, et al. Mediator and cohesin connect gene expression and chromatin architecture. Nature. 2010;467:430–435. doi: 10.1038/nature09380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hu G, Kim J, Xu Q, Leng Y, Orkin SH, Elledge SJ. A genome-wide RNAi screen identifies a new transcriptional module required for self-renewal. Genes Dev. 2009;23:837–848. doi: 10.1101/gad.1769609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ding L, Paszkowski-Rogacz M, Nitzsche A, Slabicki MM, Heninger AK, de Vries I, Kittler R, Junqueira M, Shevchenko A, Schulz H, et al. A genome-scale RNAi screen for Oct4 modulators defines a role of the Paf1 complex for embryonic stem cell identity. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:403–415. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Fazzio TG, Panning B. Condensin complexes regulate mitotic progression and interphase chromatin structure in embryonic stem cells. J Cell Biol. 2010;188:491–503. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200908026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Solozobova V, Rolletschek A, Blattner C. Nuclear accumulation and activation of p53 in embryonic stem cells after DNA damage. BMC Cell Biol. 2009;10:46. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-10-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dumitru R, Gama V, Fagan BM, Bower JJ, Swahari V, Pevny LH, Deshmukh M. Human embryonic stem cells have constitutively active Bax at the Golgi and are primed to undergo rapid apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2012;46:573–583. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Song H, Chung SK, Xu Y. Modeling disease in human ESCs using an efficient BAC-based homologous recombination system. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:80–89. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Maimets T, Neganova I, Armstrong L, Lako M. Activation of p53 by nutlin leads to rapid differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Oncogene. 2008;27:5277–5287. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hadjal Y, Hadadeh O, Yazidi CE, Barruet E, Binétruy B. A p38MAPK-p53 cascade regulates mesodermal differentiation and neurogenesis of embryonic stem cells. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e737. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Heo SH, Cha Y, Park KS. Hydroxyurea induces a hypersensitive apoptotic response in mouse embryonic stem cells through p38-dependent acetylation of p53. Stem Cells Dev. 2014;23:2435–2442. doi: 10.1089/scd.2013.0608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lee KH, Li M, Michalowski AM, Zhang X, Liao H, Chen L, Xu Y, Wu X, Huang J. A genomewide study identifies the Wnt signaling pathway as a major target of p53 in murine embryonic stem cells; Proc Natl Acad Sci USA; 2010; pp. 69–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Abdelalim EM, Tooyama I. Knockdown of p53 suppresses Nanog expression in embryonic stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;443:652–657. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Akdemir KC, Jain AK, Allton K, Aronow B, Xu X, Cooney AJ, Li W, Barton MC. Genome-wide profiling reveals stimulus-specific functions of p53 during differentiation and DNA damage of human embryonic stem cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:205–223. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zhen HY, Zhou J, Wu HN, Yao C, Zhang T, Wu T, Quan CS, Li YL. Lidamycin regulates p53 expression by repressing Oct4 transcription. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;447:224–230. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.03.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ng WL, Chen G, Wang M, Wang H, Story M, Shay JW, Zhang X, Wang J, Amin AR, Hu B, et al. OCT4 as a target of miR-34a stimulates p63 but inhibits p53 to promote human cell transformation. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1024. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 103.Chen T, Du J, Lu G. Cell growth arrest and apoptosis induced by Oct4 or Nanog knockdown in mouse embryonic stem cells: A possible role of Trp53. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39:1855–1861. doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-0928-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zhang ZN, Chung SK, Xu Z, Xu Y. Oct4 maintains the pluripotency of human embryonic stem cells by inactivating p53 through Sirt1-mediated deacetylation. Stem Cells. 2014;32:157–165. doi: 10.1002/stem.1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yu KR, Yang SR, Jung JW, Kim H, Ko K, Han DW, Park SB, Choi SW, Kang SK, Schöler H, Kang KS. CD49f enhances multipotency and maintains stemness through the direct regulation of OCT4 and SOX2. Stem Cells. 2012;30:876–887. doi: 10.1002/stem.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Itahana Y, Zhang J, Göke J, Vardy LA, Han R, Iwamoto K, Cukuroglu E, Robson P, Pouladi MA, Colman A, Itahana K. Histone modifications and p53 binding poise the p21 promoter for activation in human embryonic stem cells. Sci Rep. 2016;6:28112. doi: 10.1038/srep28112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Suvorova II, Grigorash BB, Chuykin IA, Pospelova TV, Pospelov VA. G1 checkpoint is compromised in mouse ESCs due to functional uncoupling of p53-p21Waf1 signaling. Cell Cycle. 2016;15:52–63. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2015.1120927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Filion TM, Qiao M, Ghule PN, Mandeville M, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Lian JB, Altieri DC, Stein GS. Survival responses of human embryonic stem cells to DNA damage. J Cell Physiol. 2009;220:586–592. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Zhu H, Hu S, Baker J. JMJD5 regulates cell cycle and pluripotency in human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2014;32:2098–2110. doi: 10.1002/stem.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Niculescu AB, III, Chen X, Smeets M, Hengst L, Prives C, Reed SI. Effects of p21(Cip1/Waf1) at both the G1/S and the G2/M cell cycle transitions: pRb is a critical determinant in blocking DNA replication and in preventing endoreduplication. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:629–643. doi: 10.1128/MCB.18.1.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Karimian A, Ahmadi Y, Yousefi B. Multiple functions of p21 in cell cycle, apoptosis and transcriptional regulation after DNA damage. DNA Repair (Amst) 2016;42:63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Chan WH, Houng WL, Lin CA, Lee CH, Li PW, Hsieh JT, Shen JL, Yeh HI, Chang WH. Impact of dihydrolipoic acid on mouse embryonic stem cells and related regulatory mechanisms. Environ Toxicol. 2013;28:87–97. doi: 10.1002/tox.20700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Tahmasebi S, Alain T, Rajasekhar VK, Zhang JP, Prager-Khoutorsky M, Khoutorsky A, Dogan Y, Gkogkas CG, Petroulakis E, Sylvestre A, et al. Multifaceted regulation of somatic cell reprogramming by mRNA translational control. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:606–616. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zhen HY, He QH, Li Y, Zhou J, Yao C, Liu YN, Ma LJ. Lidamycin induces neural differentiation of mouse embryonic carcinoma cells through down-regulation of transcription factor Oct4. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;421:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.03.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Tsai CC, Su PF, Huang YF, Yew TL, Hung SC. Oct4 and Nanog directly regulate Dnmt1 to maintain self-renewal and undifferentiated state in mesenchymal stem cells. Mol Cell. 2012;47:169–182. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lee J, Go Y, Kang I, Han YM, Kim J. Oct-4 controls cell-cycle progression of embryonic stem cells. Biochem J. 2010;426:171–181. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Abu Dawud R, Schreiber K, Schomburg D, Adjaye J. Human embryonic stem cells and embryonal carcinoma cells have overlapping and distinct metabolic signatures. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39896. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kondoh H, Lleonart ME, Nakashima Y, Yokode M, Tanaka M, Bernard D, Gil J, Beach D. A high glycolytic flux supports the proliferative potential of murine embryonic stem cells. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:293–299. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Margineantu DH, Hockenbery DM. Mitochondrial functions in stem cells. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2016;38:110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Folmes CD, Terzic A. Energy metabolism in the acquisition and maintenance of stemness. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2016;52:68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Folmes CD, Ma H, Mitalipov S, Terzic A. Mitochondria in pluripotent stem cells: Stemness regulators and disease targets. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2016;38:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.St John JC. Mitochondrial DNA copy number and replication in reprogramming and differentiation. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2016;52:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Lees JG, Rathjen J, Sheedy JR, Gardner DK, Harvey AJ. Distinct profiles of human embryonic stem cell metabolism and mitochondria identified by oxygen. Reproduction. 2015;150:367–382. doi: 10.1530/REP-14-0633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Heiden MG Vander, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: The metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009;324:1029–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Lunt SY, Heiden MG Vander. Aerobic glycolysis: Meeting the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2011;27:441–464. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Bigarella CL, Liang R, Ghaffari S. Stem cells and the impact of ROS signaling. Development. 2014;141:4206–4218. doi: 10.1242/dev.107086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Wanet A, Arnould T, Najimi M, Renard P. Connecting mitochondria, metabolism, and stem cell fate. Stem Cells Dev. 2015;24:1957–1971. doi: 10.1089/scd.2015.0117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Kim H, Jang H, Kim TW, Kang BH, Lee SE, Jeon YK, Chung DH, Choi J, Shin J, Cho EJ, Youn HD. Core pluripotency factors directly regulate metabolism in embryonic stem cell to maintain pluripotency. Stem Cells. 2015;33:2699–2711. doi: 10.1002/stem.2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Christensen DR, Calder PC, Houghton FD. GLUT3 and PKM2 regulate OCT4 expression and support the hypoxic culture of human embryonic stem cells. Sci Rep. 2015;5:17500. doi: 10.1038/srep17500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Lee J, Kim HK, Han YM, Kim J. Pyruvate kinase isozyme type M2 (PKM2) interacts and cooperates with Oct-4 in regulating transcription. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:1043–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]