Abstract

The present study aimed to discriminate different subsets of cultured dendritic cells (DCs) to evaluate their immunological characteristics. DCs offer an important foundation for immunological studies, and mouse bone marrow (BM) cells cultured with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) have been used extensively to generate CD11c+/major histocompatibility complex II+ BM-derived DCs (BMDCs). Immature DCs are considered to have strong migration and phagocytic antigen-capturing abilities, whereas mature DCs are thought to activate naive T cells and express high levels of costimulatory cytokines and adhesion molecules. In most culture systems, non-adherent cells are collected as mature and qualified DCs, and the remaining adherent cells are discarded. The output from GM-CSF cultures comprises mostly adherent cells, and only a small portion of them is non-adherent. This situation has resulted in ambiguities in the attempts to understand results from the use of cultured DCs. In the present study, DCs were divided into three subsets: i) Non-adherent cells; ii) adherent cells and iii) mixed cells. The heterogeneous features of cultured DCs were identified by evaluating the maturation status, cytokine secretion and the ability to activate allogeneic T cells according to different subsets. Results from the study demonstrated that BMDC culture systems were a heterogeneous group of cells comprising non-adherent cells, adherent cells, mixed cells and firmly adherent cells. Non-adherent cells may be used in future studies that require relatively mature DCs such as anticancer immunity. Adherent cells may be used to induce tolerance DCs, whereas mixed cells may potentiate either tolerogenicity or pro-tumorigenic responses. Firmly adherent cells were considered to have macrophage-like properties. The findings may aid in immunological studies that use cultured DCs and may lead to more precise DC research.

Keywords: dendritic cells, differentiation, discrimination, heterogeneity

Introduction

Dendritic cells (DCs), which differentiate to highly competent antigen-presenting cells, are pivotal elements of immune response in processing and presenting antigens (1). DCs present immunogenic or tolerogenic effects in subsequent immune reactions according to their maturation and functional and molecular expression (2). The current method of DC generation is based on bone marrow (BM) culture and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) supplementation, and is used worldwide. However, the DC lineage is complex due to the DC cell derivation and differentiation, and there are many similarities and diversities compared with other hematopoietic cells, including monocytes and macrophages (3,4).

A previous study has demonstrated that BM cells are able to differentiate to classical (or conventional) DCs (cDCs) in an in vitro mouse models (5). cDCs are considered the most important and distinct lineage for stimulating naive T cell activation (3), although the identification of other DC subsets, such as plasmacytoid DCs, Langerhans cells and monocyte-derived DCs, has markedly improved. However, cultured DCs have been demonstrated to be a heterogeneous group of cells resulting in variations in the usage of DCs (6,7). This heterogeneous state may be explained as follows: i) The source of DCs is highly variable, including from BM, peripheral blood mononuclear cells or monocytes, or from rodents or humans; and ii) DCs may be modulated by cultural environments and stimulating factors, and the differentiation of stem cells or progeny DCs is extremely complex, which results in numerous subsets. Another problem is that at the end of the culture process, different DC subsets are selected for subsequent experiments, including non-adherent mature DCs, all non-adherent cells, loosely adherent clusters, both non-adherent and loosely adherent cells or all cells (8–11). Several previous studies have not provided information on the DC subsets that were examined (12,13). This phenomenon reflects a widespread lack of information regarding the heterogeneity of cultured DCs, which has resulted in a lack of clear understanding of the findings related to their usage (14–16). Therefore, efforts are still required to optimize DC culture systems and to discriminate the heterogeneity of DC culture subsets.

In the present study, DCs were divided into three subsets: i) Non-adherent; ii) adherent; and iii) mixed. Cytokine secretion from progeny DCs and DCs was evaluated on culture days 3, 6 and 8. In addition, the maturation state of the three subsets in the presence of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation was detected. Accordingly, at the end of the culture process, mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR) was used to analyze the ability of each subset to stimulate T cell proliferation by alloantigen presentation. This study provided a promising BM-derived DC culture system in regards to the quantity and quality of the final DC products. Notably, to the best of our knowledge, this was the first study to divide cultured DCs into three subsets to observe their heterogenic immunological properties based on their adherent status. These aspects may be emphasized in immunological investigations when using cultured DCs.

Materials and methods

Animals

The commonly used mouse strains C57BL/6 (H2b) (n=8) and BALB/c (H2d) (n=32) were used in the present study. A total of 40 male mice (age, 6–8 weeks; weight, 20±1 g) were obtained from Beijing HFK Bioscience Co. Ltd. (Beijing, China), and kept under specific pathogen-free conditions, at 25°C in 55% humidity and under 12-h light/dark cycles, with free access to food and water. All experiments in this protocol were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology (Wuhan, China).

Bone marrow preparation and DC culture system

Balb/c were euthanized and rinsed liberally in ethanol for 5 min. The hindlimbs were severed and the attached soft tissues were rubbed from the femurs and tibias with sterile gauze. Both ends of the epiphyses were cut from the marrow cavity and the marrow was flushed out with RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) into a dish. The medium was filtered through a 74-µm aperture nylon mesh to a 15 ml centrifuge tube in order to remove small pieces of bone and debris. The tube was centrifuged at 300 × g at room temperature for 5 min and the supernatant was discarded. Red blood cells were collected and lysed with 1 ml Red Blood Cell Lysis buffer (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) for 2 min to obtain BM-derived mononuclear cells (BMDMCs). A total of 5 ml RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% FBS was added to dilute the lysis buffer at room temperature and the mixture was centrifuged at 300 × g at room temperature for 5 min. Cells (1×106 cells/ml) were cultured (5% CO2, 37°C) in 10 ml fresh RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% FBS. Subsequently, recombinant murine (rm) GM-CSF (20 ng/ml) and rm-interleukin (IL)-4 (10 ng/ml; both from PeproTech, Inc., Rocky Hill, NJ, USA) were added and the culture dish was incubated in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C.

Following 3 days incubation, the medium (including non-adherent cells) was aspirated and discarded. Fresh complete RPMI-640 medium (10 ml) containing rmGM-CSF (20 ng/ml) and rmIL-4 (10 ng/ml) was added and the cells were returned to the incubator. On day 6, the medium was collected, centrifuged at 300 × g at room temperature for 5 min, and the cell pellet was resuspended in 10 ml complete RPMI-1640 medium containing 20 ng/ml rmGM-CSF and 10 ng/ml rmIL-4. The resuspended cells (~2.5×106 cells) were returned to the incubator for further culture. On day 7, LPS (500 ng/ml; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) was added to the culture dish to stimulate DC maturation for 24 h, and on day 8, the different subsets of cultured cells were collected, as described below, for further investigation.

Isolation of different DC subsets

Cultured cells were divided according to their different adherent features: Non-adherent, loosely adherent, dislodgeable adherent and firmly adherent. Non-adherent cells were the cells floating in the medium following a gently swirling the dish. Loosely adherent cells were obtained following 3 min digestion with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and gentle pipetting at 37°C. Dislodgeable adherent cells were defined as the cells that fell to the bottom of the culture dish following 0.25% trypsin-EDTA digestion for 5 min with vigorous pipetting at 37°C. Firmly adherent cells were the cells that remained on the wall following hard trypsin-EDTA digestion and vigorous pipetting, as have been confirmed as vacuolated macrophages, as previously described (17). In the present study, DCs were collected and analyzed in the following subsets: i) Non-adherent cells; ii) adherent cells, which comprised loosely adherent + dislodgeable adherent cells; and iii) mixed cells, which comprised non-adherent cells + adherent cells. As firmly adherent cells do not contribute to cDC population, they were not used in subsequent investigations. Cells were harvested, centrifuged at 300 × g for 5 min at room temperature and a single-subset suspension of the purified cells was prepared for further experiments.

Phenotypic analysis

To analyze phenotypic markers of the different DC subsets, the cells were stained in the dark at 4°C for 30 min with the following monoclonal antibodies from eBioscience (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.): Allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated anti-CD11c (cat no. 17-0114, 1:800), phycoerythrin (PE)/cyanine (Cy)5-conjugated anti-CD40 (cat no. 15-0401, 1:800), fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-CD80 (cat no. 11-0801, 1:2,000), PE/Cy5-conjugated anti-CD86 (cat no. 15-0862, 1:3,333); PE-conjugated anti-major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II; act no. 12-5321, 1:10,000), APC-conjugated anti-F4/80 (cat no. 17-4801, 1:100) and PE-conjugated anti-CD11b (cat no. 12-0118, 1:1). Corresponding isotype-matched irrelevant specificity controls were performed in parallel, using Armenian hamster immunoglobulin (Ig) G isotype control (cat no. 11-4888; eBioscience; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) in the same dilutions as the target antibodies. A total of 10,000 events were collected for each test by BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and cells with large forward scattering and side scattering were analyzed by FlowJo software version 7.6 (FlowJo LLC, Ashland, OR, USA).

Cytokine profiling in different subsets of DCs

During the process of differentiation and maturation, progeny DCs and parent DCs develop the ability to secrete cytokines based on their heterogenic immunological features (18). To explore their immune function, cytokine secretion profiles were studied on day 3, 6 and 8. At each time point the adherent, non-adherent and mixed cells were harvested at a density of 7×106. Following 2 washes with PBS (Hyclone; GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Logan, UT, USA), the cells were seeded in a 100 mm plastic tissue culture dish in 10 ml complete RPMI-1640 medium for an overnight incubation at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Subsequently, the medium was collected to measure the levels of IL-2 (cat no. BMS601), IL-12p70 (cat no. BMS6004), interferon (IFN)-γ (cat no. BMS606), IL-4 (cat no. BMS613) and IL-10 (cat no. BMS614/2) production by sandwich ELISA kits (Platinum ELISA, all by eBioscience; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Cytokine levels were measured as pg/ml and quantified by reference, according to the manufacturer's protocol.

CD3+ T cell isolation and culture

Male C57BL/6 (H2b) mice (n=8) were euthanized and their armpits, groin and mesenteric lymph nodes were harvested. The lymph nodes were placed in a 60×15 mm2 culture dish with 5 ml serum-free PBS. Lymph nodes were minced and the mixture was filtered through a 74-µm aperture nylon mesh to obtain allogeneic responder T lymphocytes. The freshly isolated lymphocytes were centrifuged for 5 min at 300 × g at room temperature and lymphocytes were purified using a Mouse CD3+ T Cell Enrichment Column (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Allogeneic T cell activation

MLR was performed to measure the proliferative response of allogeneic T cells that were stimulated by the cultured DCs. On day 8 of incubation, the adherent cells, non-adherent cells and mixed cells were collected and served as stimulators, and the CD3+ T cells isolated from lymph nodes of allogeneic C57BL/6 mice served as responders. The responder T cells were 92% CD3+ cells, and were labeled with a carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl amino ester tracer at 37°C for 10 min (CFSE; 1 µmol/l in PBS; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), as previously described (19). The labeling process was quenched by adding 800 µl FBS on ice for 5 min. The CFSE-labeled T cells were centrifuged at 300 × g at room temperature for 5 min. Stimulator DCs (non-adherent cells, adherent cells or mixed cells) at a density of 1×105 cells/well were co-cultured with CFSE-labeled T cells (5×105 cells/well) at a 1:5 ratio of DCs to T cells in 96-well rounded-bottom microtiter plates (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA) at a final volume of 200 µl of RPMI-1640 medium with 10% FBS, and incubated at 37°C for 4 days. CFSE-labeled T cells cultured alone served as the negative control. T cells treated with anti-mouse CD3e (cat no. 16-0031; 1:2,000, eBioscience, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and anti-mouse CD28 (cat no. 16-0281; 1:2,000, eBioscience, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) antibodies served as positive controls. A total of 5 groups of cells (negative control, positive control, T cells co-cultured with non-adherent cells, T cells co-cultured with adherent cells and T cells co-cultured with mixed cells) were collected separately and centrifuged twice for 5 min at 300 × g at room temperature with 2 ml cold FACS buffer (PBS supplemented with 5% FBS and 0.05% NaN3). Cells were stained with APC-labeled anti-CD4 (cat no. 17-0042; 1:600, eBioscience, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 30 min at 4°C in the dark and analyzed by flow cytometry (FlowJo software version 7.6; FlowJo LLC, Ashland, OR, USA). MLR was evaluated as follows: i) CD4+ T cells gathering to the y-axis with clear proliferation stripes following stimulation, and presenting a strong proliferative response to the stimulator (20); ii) the proliferative index, which was defined as the sum of the cells in all generations divided by the calculated number of original cells (21); and iii) the cell division index, which was defined as the average number of divisions undertaken by all T cells in the parent generation (22).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. All experiments were conducted four to eight times. Repeated measures analysis of variance was used to assess the statistical significance of the differences between groups, and the Bonferroni method was used to correct for multiple comparisons. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. All statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS software, version 19.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

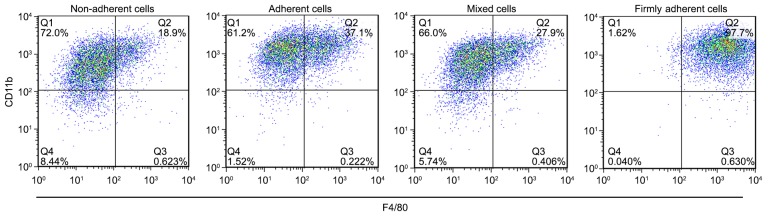

F4/80 and CD11b expression on the cell surface classifies firmly adherent cells as macrophages

GM-CSF was able to generate populations of macrophages and DCs in cell culture. The expressions of F4/80 and CD11b on the cell surface were used as specific markers to identify macrophages. The percent of F4/80+CD11b+ cells in each group was 21.00±2.59% in the non-adherent cells, 38.17±0.97% in the adherent cells, 28.60±1.04% in the mixed cells and 98.20±0.46% in the firmly adherent cells (P<0.0001, firmly adherent cells vs. non-adherent cells, adherent cells and mixed cells; Fig. 1), which indicated that the firmly adherent cells consisted of macrophages. These results are consistent with those described by Inaba et al (17) in 1992, which demonstrated that macrophages firmly adhered to the culture vessel, expressed high levels of the F4/80 antigen expressed little or no MHC-II and exhibit no MLR-stimulating activity. Because the firmly adherent cells did not contribute to the population of cDCs, they were not used for further investigations.

Figure 1.

F4/80 and CD11b expression on the cell surface of non-adherent, adherent, mixed and firmly adherent cells. On day 8, the cell subsets were analyzed for the expression of the macrophage-specific surface markers F4/80 and CD11b. The firmly adherent cells exhibited a positive expression of 98.20±0.46%, which indicated that the vast majority of the firmly adherent cells are macrophages.

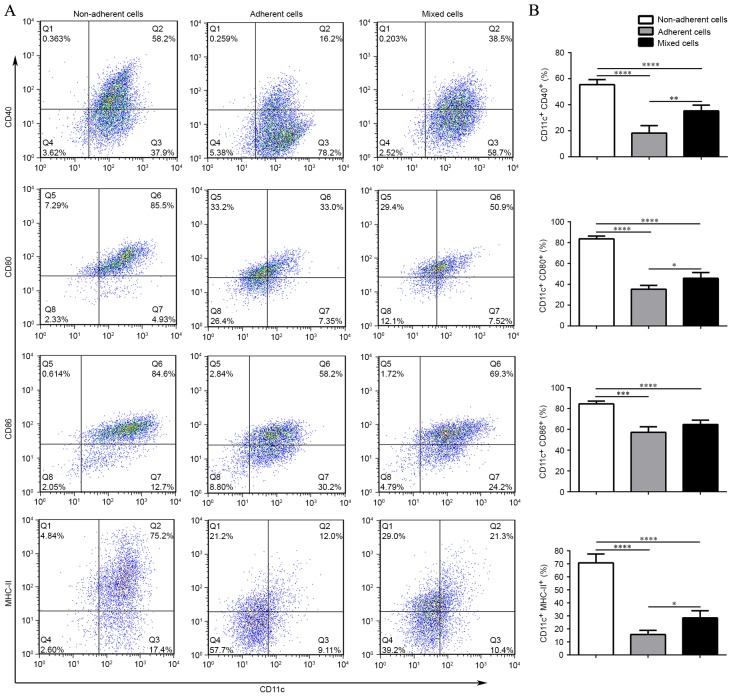

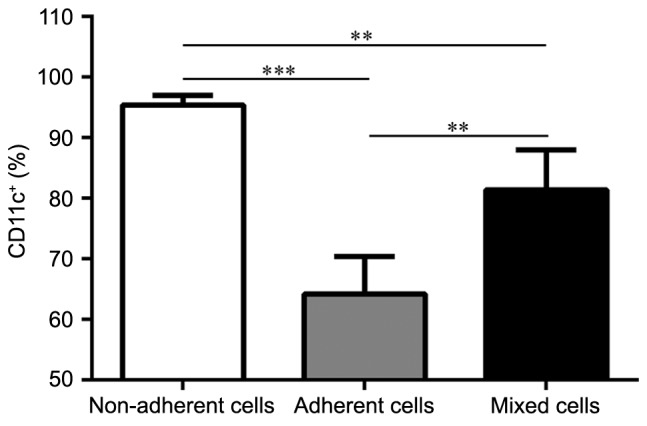

Each DC subset displays different purity and maturation states

In order to clarify the purity of the three DC subsets, the remaining three BM-derived DC subsets were probed CD11c+ expression. Populations of the non-adherent, adherent and mixed cells were purified on day 8. CD11c+ expression analysis from the cultures revealed that all three DC subsets were able to expand in GM-CSF and IL-4 cultures, and generated various levels of CD11c+ cells (Fig. 2): 95.43±1.57% for the non-adherent cells (P<0.001 vs. adherent cells; P=0.0046 vs. mixed cells); 64.20±6.18% for the adherent cells; and 81.43±6.59% for the mixed cells (P=0.0026 vs. adherent cells). On day 8, the maturation phenotype of three subsets was analyzed following LPS stimulation. The graphs in Fig. 3A and B demonstrate that the adherent cells expressed the lowest level of CD11c+CD40+, CD11c+CD80+, CD11c+CD86+ and CD11c+MHC-II+ compared with the non-adherent cells and mixed cells, which indicated their ability to induce immune tolerance or suppression. Conversely, the non-adherent cells displayed the highest expression levels of the costimulatory molecules, which indicated that the cultured DC population was homogeneous and that DCs with different degrees of adhesion may have different maturation status.

Figure 2.

Purity of the non-adherent, adherent and mixed cells. On day 8, the percentage of CD11c+ cells within the cell subsets were analyzed by flow cytometry. The non-adherent cells expressed the highest level of CD11c+ cells. n=5/group; **P<0.005 and ***P<0.001.

Figure 3.

Different maturation states in response to LPS stimulation among the non-adherent, adherent and mixed cells. (A) Representative flow cytometric graphs, obtained from the cell subsets stained with CD11c, CD40, CD80, CD86, and MHC-II on day 8. Non-adherent cells expressed the highest levels of CD11c+CD40+, CD11c+CD80+, CD11c+CD86+ and CD11c+MHC-II+. (B) Flow cytometric analysis demonstrating the different maturation status in response to LPS among the non-adherent, adherent and mixed cells. Error bars indicate the mean ± standard deviation; n=5/group; *P<0.05, **P<0.005, ***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001. LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MHC-II, major histocompatibility complex class II.

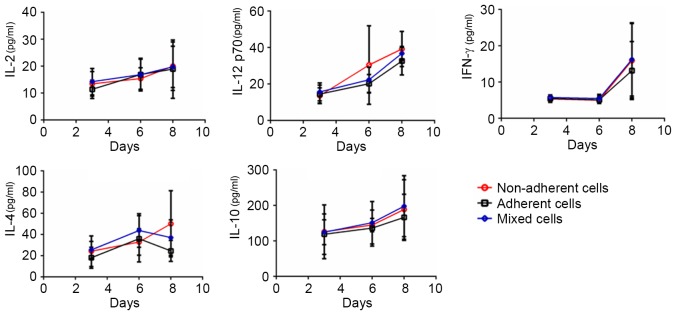

Each DC subset exhibits different cytokine secretion levels throughout the DC culture process

Protein expression levels of the secreted cytokines IL-2, IL-12p70, IFN-γ, IL-4 and IL-10 in the three subsets were examined on days 3, 6 and 8 (Fig. 4). In addition to IL-4 and IL-12 p70, the expression of IL-2, IL-10 and IFN-γ in non-adherent cells, adherent cells and mixed cells was not significantly different between days 3, 6 and 8. Notably, the cytokine secretion profiles revealed the heterogeneity of the cultured DCs: IL-4 expression from day 6 appeared to increase in the non-adherent cells, whereas it appeared to decrease in the adherent and mixed cells, indicating that DC polarization occurred and the DC reservoir was not homogenous. On day 8, the non-adherent cells secreted high levels of both T helper (Th)1-type (IL-12p70) and Th2-type (IL-4) cytokines, which indicated that the non-adherent DCs themselves were not homogenous. Furthermore, following day 6, the curves of the cytokine secretion profiles for IFN-γ, IL-12 p70 and IL-10 in the three DC subsets became steeper, suggesting rapid development of the immune function of DCs. Therefore, day 6 may be a pivotal time point in which to modulate the immunological characteristics of the cultured DCs.

Figure 4.

Cytokine secretion levels in the non-adherent, adherent and mixed cells throughout the dendritic cell culture process. On days 3, 6 and 8, cell subsets (7×106 cells) were harvested, reseeded following an overnight incubation, and the cell suspension was collected to quantify the cytokine levels of IL-2, IL-12p70, IFN-γ, IL-4 and IL-10 using sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits. IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin.

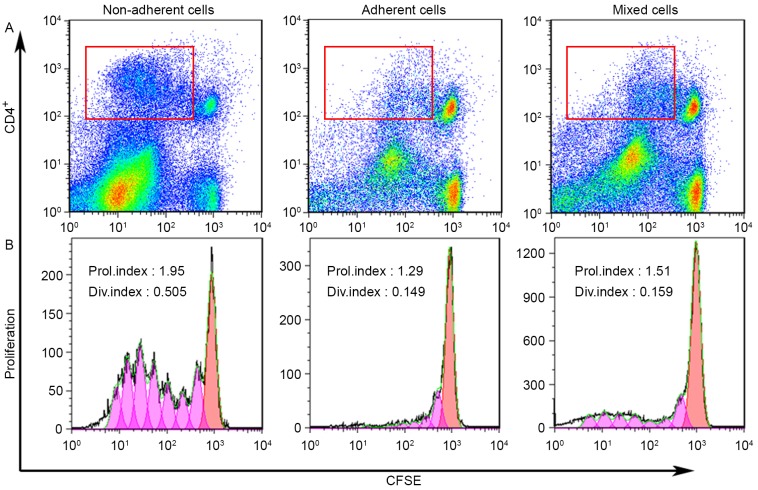

Each DC subset exhibits a different immunological reaction

The antigen-presenting ability of each DC subset was examined by MLR. Allogeneic T lymphocytes were stained with CFSE and cultured alone (negative control), with anti-mouse CD3e and anti-mouse CD28 (positive control groups), with non-adherent cells, with adherent cells and with mixed cells. After 4 days of incubation, cells were harvested and stained with anti-CD4 prior to analysis by flow cytometry. As presented in Fig. 5A, a bivariate dot-plot of CD4 expression and the level of CFSE fluorescence demonstrated that the non-adherent cells-treated T cells had undergone division and gathered on the y-axis, indicating high proliferation (red frame). The adherent cells-treated T cells exhibited limited division. The mixed cells-treated T cells demonstrated partial division. The proliferative index of the gated CD4+ T cells by stimulation of non-adherent cells, adherent cells and mixed cells was 1.69±0.33, 1.29±0.09 and 1.30±0.10, respectively, whereas the index of the negative and positive controls was 1.22±0.24 and 1.67±0.05, respectively. The cell division index of the gated CD4+ T cells of non-adherent cells, adherent cells and mixed cells was 0.33±0.21, 0.16±0.02 and 0.11±0.04, respectively, while the index of the negative and positive controls was 0.13±0.10 and 0.75±0.27, respectively (Fig. 5B). The MLR results demonstrated that the non-adherent DCs exhibited an strong ability to stimulate allogeneic T cell proliferation, whereas the ability of adherent DCs to stimulate T cell proliferation was weak.

Figure 5.

Proliferative response of allogeneic T cells among the non-adherent, adherent and mixed cell subsets. The ability of dendritic cells to stimulate allogeneic T cell proliferation was evaluated by (A) CD4+ T cell proliferation stripes (red frame) following stimulation and (B) proliferative index and cell division index. CFSE, carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl amino ester; Div, division; Prol, proliferative.

Discussion

Heterogeneity of the DC subsets emerges from the first day during the culture process, owing to complicated DC differentiation (23). Previous studies have reportedly observed the presence of: i) BM non-adherent MHC-II− progenitors attaching to the stroma or plastic; ii) growing aggregates arising from firmly adherent MHC-II+ DCs; iii) mature, proliferating MHC-II+ DCs being released by the loosely attached aggregate; and iv) non-proliferating, non-adherent MHC-II+ DCs suspended in the medium, much like many of the DCs released from the spleen (17,24). During the permanent differentiation process from BM cells and progeny DCs to mature DCs, the cultured cells dynamically expressed a specific molecular form and immunological function (25), which resulted in the co-existence of various subsets of DCs (26). To accurately understand the DC reservoir, the immunological identification of DC subsets is required. To achieve a certain immunological aim, the investigators should select the corresponding cultured subset from the DC reservoir based on its maturity status and immunological features. For example, for anti-tumor or infectious effects, the mature subset should be used to prime T cells (27–29), for tolerance induction or immunosuppressive effects, the immature DCs should be used (30) and to check the effects of immune modulation therapy administered in vivo, mixed cultured DCs should first be tested in vitro (31). Unfortunately, the differences between the cultured subsets have been largely ignored, leading to confusion.

In the present study, the three DC subsets were distinguished from macrophages by detecting the expression of F4/80 and CD11b. CD11c was used to detect the different purity of non-adherent cells, adherent cells and mixed cells. CD40, CD80, CD86 and MHC-II were used to detect the different maturation state of non-adherent cells, adherent cells and mixed cells. The present results demonstrated that the adherent cells expressed the lowest levels of CD11c+CD40+, CD11c+CD80+, CD11c+CD86+ and CD11c+MHC-II+ compared with the non-adherent cells and mixed cells. The non-adherent cells displayed the highest expression levels of the costimulatory molecules, which indicated that the cultured DC population was homogeneous.

Given that the discrimination of DC subsets practically depends on their adherent status, the cells used in the present study were segregated as non-adherent, adherent, and mixed. The heterogeneity of the cultured DCs was determined using phenotypic markers and kinetic analysis of cytokine secretion in response to LPS and MLR stimulation. Continuous IL-2 secretion by the three subsets throughout the culture process indicated that the cultured DCs were functional and that the culture strategy was promising. The present study also demonstrated DC polarization through the differences in expression of IL-4 in the adherent and non-adherent cells. However, the non-adherent cells secreted high levels of both Th1-type cytokines and Th2-type cytokines on day 8, and the different secretory function, for IFN-γ, IL-12 p70 and IL-10, of the adherent cells and non-adherent cells developed rapidly from day 6. Furthermore, the non-adherent cells appeared to acquire mature features, whereas the adherent cells exhibited immature features based on their Th1-type and Th2-type cytokine secretion and ability to stimulate allogeneic T cell proliferation. MLR results revealed that non-adherent cells could stimulate the proliferation and division of allogeneic T lymphocytes, whereas the ability of adherent DCs to stimulate T cell proliferation was limited. The mixed cells were demonstrated to partially stimulate the proliferation and division of T cells. These data indicated that at the end of DC differentiation and proliferation, the cultured DC reservoir possessed heterogeneity, and non-adherent cells were not homogenous.

Limitations of the present study included the small sample size and the lack of assessments of cell viability and apoptosis within the experimental groups; further studies are required to address these issues. In conclusion, the present study discriminated cultured DCs as subsets of non-adherent, adherent and mixed cells, and identified their heterogeneous immunological features. The findings may enhance the knowledge of DC culture techniques and promote DC research in a more precise manner.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from The National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 81570678 and 81373169 to Nianqiao Gong and Jun Yang, respectively), the National High-Tech Researching and Developing Program (Program 863) of Ministry of Science and Technology of China (grant no. 2012AA021010 to Changsheng Ming) and the Clinical Research Physician Program of Tongji Medical College, HUST (to Nianqiao Gong).

References

- 1.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392:245–252. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang J, Zhao LB, Chang S, Ming CS, Yang J, Gong NQ. Dynamic changes of phenotypes and secretory functions during the differentiation of pre-DCs to mature DCs. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 2017;37:191–196. doi: 10.1007/s11596-017-1714-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Satpathy AT, Wu X, Albring JC, Murphy KM. Re(de)fining the dendritic cell lineage. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:1145–1154. doi: 10.1038/ni.2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cortez-Retamozo V, Etzrodt M, Pittet MJ. Regulation of macrophage and dendritic cell responses by their lineage precursors. J Innate Immun. 2012;4:411–423. doi: 10.1159/000335733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merad M, Sathe P, Helft J, Miller J, Mortha A. The dendritic cell lineage: Ontogeny and function of dendritic cells and their subsets in the steady state and the inflamed setting. Annu Rev Immunol. 2013;31:563–604. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-074950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shurin MR, Pandharipande PP, Zorina TD, Haluszczak C, Subbotin VM, Hunter O, Brumfield A, Storkus WJ, Maraskovsky E, Lotze MT. FLT3 ligand induces the generation of functionally active dendritic cells in mice. Cell Immunol. 1997;179:174–184. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1997.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naik SH, Proietto AI, Wilson NS, Dakic A, Schnorrer P, Fuchsberger M, Lahoud MH, O'Keeffe M, Shao QX, Chen WF, et al. Cutting edge: Generation of splenic CD8+ and CD8+ dendritic cell equivalents in Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand bone marrow cultures. J Immunol. 2005;174:6592–6597. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.6592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yi HJ, Lu GX. Adherent and non-adherent dendritic cells are equivalently qualified in GM-CSF, IL-4 and TNF-α culture system. Cell Immunol. 2012;277:44–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2012.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalantari T, Kamali-Sarvestani E, Zhang GX, Safavi F, Lauretti E, Khedmati ME, Rostami A. Generation of large numbers of highly purified dendritic cells from bone marrow progenitor cells after co-culture with syngeneic murine splenocytes. Exp Mol Pathol. 2013;94:336–342. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delirezh N, Shojaeefar E. Phenotypic and functional comparison between flask adherent and magnetic activated cell sorted monocytes derived dendritic cells. Iran J Immunol. 2012;9:98–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdi K, Singh NJ, Matzinger P. Lipopolysaccharide-activated dendritic cells: ‘Exhausted’ or alert and waiting? J Immunol. 2012;188:5981–5989. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kushwah R, Wu J, Oliver JR, Jiang G, Zhang J, Siminovitch KA, Hu J. Uptake of apoptotic DC converts immature DC into tolerogenic DC that induce differentiation of Foxp3+ Treg. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:1022–1035. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pantel A, Teixeira A, Haddad E, Wood EG, Steinman RM, Longhi MP. Direct type I IFN but not MDA5/TLR3 activation of dendritic cells is required for maturation and metabolic shift to glycolysis after poly IC stimulation. PLoS Biol. 2014;12:e1001759. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Y, Cao Y, Meng Y, You Z, Liu X, Liu Z. The novel role of thymopentin in induction of maturation of bone marrow dendritic cells (BMDCs) Int Immunopharmacol. 2014;21:255–260. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2014.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li R, Zheng X, Popov I, Zhang X, Wang H, Suzuki M, Necochea-Campion RD, French PW, Chen D, Siu L, et al. Gene silencing of IL-12 in dendritic cells inhibits autoimmune arthritis. J Transl Med. 2012;10:19. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Song Q, Meng Y, Wang Y, Li M, Zhang J, Xin S, Wang L, Shan F. Maturation inside and outside bone marrow dendritic cells (BMDCs) modulated by interferon-α (IFN-α) Int Immunopharmacol. 2013;17:843–849. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2013.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inaba K, Inaba M, Romani N, Aya H, Deguchi M, Ikehara S, Muramatsu S, Steinman RM. Generation of large numbers of dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow cultures supplemented with granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J Exp Med. 1992;176:1693–1702. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.6.1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmid MA, Kingston D, Boddupalli S, Manz MG. Instructive cytokine signals in dendritic cell lineage commitment. Immunol Rev. 2010;234:32–44. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kunieda Y, Tamura Y, Sasaki H, Kurokawa Y, Miyagishima T, Ohae Y, Hige S, Gotohda Y, Tanaka J, Higuchi A, et al. Carcinoid of the papilla of Vater-somatostatinoma-a case report. Gan No Rinsho. 1986;32:831–836. (In Japanese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sela U, Olds P, Park A, Schlesinger SJ, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells induce antigen-specific regulatory T cells that prevent graft versus host disease and persist in mice. J Exp Med. 2011;208:2489–2496. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lyons AB, Parish CR. Determination of lymphocyte division by flow cytometry. J Immunol Methods. 1994;171:131–137. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)90236-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pinto LA, Galvão Castro B, Soares MB, Grassi MF. An evaluation of the spontaneous proliferation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells in HTLV-1-infected individuals using flow cytometry. ISRN Oncol. 2011;2011:326719. doi: 10.5402/2011/326719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haniffa M, Collin M, Ginhoux F. Ontogeny and functional specialization of dendritic cells in human and mouse. Adv Immunol. 2013;120:1–49. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-417028-5.00001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steinman RM, Cohn ZA. Identification of a novel cell type in peripheral lymphoid organs of mice. I. Morphology, quantitation, tissue distribution. J Exp Med. 1973;137:1142–1162. doi: 10.1084/jem.137.5.1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lutz MB, Kukutsch N, Ogilvie AL, Rössner S, Koch F, Romani N, Schuler G. An advanced culture method for generating large quantities of highly pure dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow. J Immunol Methods. 1999;223:77–92. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1759(98)00204-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Merad M, Manz MG. Dendritic cell homeostasis. Blood. 2009;113:3418–3427. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-180646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weigel BJ, Nath N, Taylor PA, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Chen W, Krieg AM, Brasel K, Blazar BR. Comparative analysis of murine marrow-derived dendritic cells generated by Flt3L or GM-CSF/IL-4 and matured with immune stimulatory agents on the in vivo induction of antileukemia responses. Blood. 2002;100:4169–4176. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dudek AM, Martin S, Garg AD, Agostinis P. Immature, Semi-Mature, and fully mature dendritic cells: Toward a DC-cancer cells interface that augments anticancer immunity. Front Immunol. 2013;4:438. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strome SE, Voss S, Wilcox R, Wakefield TL, Tamada K, Flies D, Chapoval A, Lu J, Kasperbauer JL, Padley D, et al. Strategies for antigen loading of dendritic cells to enhance the antitumor immune response. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1884–1889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beriou G, Moreau A, Cuturi MC. Tolerogenic dendritic cells: Applications for solid organ transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2012;17:42–47. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e32834ee662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim SJ, Diamond B. Modulation of tolerogenic dendritic cells and autoimmunity. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2015;41:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]