Abstract

It is well known that endurance training is effective to attenuate skeletal muscle atrophy. Succinate is a typical TCA metabolite, of which exercise could dramatically increase the content. The present study aimed to investigate the effect of succinate on protein synthesis in skeletal muscle, and try to delineate the underlying mechanism. The in vitro study revealed that succinate dose-dependently increased protein synthesis in C2C12 myotube along with the enhancement of phosphorylation levels of AKT Serine/Threonine Kinase 1(Akt), mammalian target of rapamycin, S6, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E, 4E binding protein 1 and forkhead box O (FoxO) 3a. Furthermore, it was demonstrated that 20 mM succinate markedly increased [Ca2+]i. Then, the phospho-extracellular regulated kinase (Erk), -Akt level and the crosstalk between Erk and Akt were elevated in response to succinate. Notably, the Erk antagonist (U0126) or mTOR inhibitor (rapamycin) abolished the effect of succinate on protein synthesis. The in vivo study verified that succinate dose-dependently increased the protein synthesis, in addition to phosphorylation levels of Erk, Akt and FoxO3a in gastrocnemius muscle. In summary, these findings demonstrated that succinate promoted skeletal muscle protein deposition via Erk/Akt signaling pathway.

Keywords: succinate, Erk, mTOR, skeletal muscle, protein synthesis

Introduction

Skeletal muscle is the most abundant tissue in the body, the mass of which represents a determinant of strength, endurance, and physical performance (1). Skeletal muscle is a plastic tissue to be hypertrophy or atrophy with the dynamic balance between protein synthesis and degradation (2–4). Muscle atrophy has been characterized as decreased protein content, decreased insulin sensitivity and increased fatigability (2,5). It is noteworthy that the protein level in skeletal muscle is dependent on mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and forkhead box O (FoxO) family. mTOR plays a critical role in promoting the protein synthesis of skeletal muscle through its downstream S6, P70S6K1, 4E-BP1, and eIF4E (6–8), while FoxO1 and FoxO3a induce the degradation of protein by regulating expression of MuRF1 and MAFbx (9).

Though skeletal muscle growth was regulated by hormone signals (10,11) and nutrients availability (12,13), endurance training has been proven to be the most effective method to attenuate the skeletal muscle atrophy. Several evidences showed that only one session of raise exercise could dramatically increase the content of TCA metabolites, such as octanoylcarnitine, glutamate, succinate and rotenone (14). In addition, both high-intensity interval training and moderate-intensity continuous training significantly increased citrate synthase activity and succinate content (15). Succinate, a vital intermediate in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, is downstream product of the α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex, which has been reported to play a crucial role in the process of cell metabolism, substrate-level phosphorylation, ketone bodies utilization and heme metabolism (16). However, the effects of succinate on skeletal muscle hypertrophy and protein synthesis was rarely excavated.

Recently, a series study delineated that succinate could induce intracellular Ca2+ by G protein coupled receptor and PLCβ (17,18). In skeletal muscle, [Ca2+]i is a vital second messenger to active Erk1/2 and promote the differentiation and protein synthesis of myotubes (19,20). So, the present evidences led to the hypothesis that succinate might be involved in skeletal muscle protein synthesis and muscle hypertrophy. To test this hypothesis, we first examined the effect of succinate on skeletal muscle protein turnover signaling pathway. We found succinate could dose-dependently promote skeletal muscle protein synthesis in vitro and in vivo, which was mediated by Erk/Akt signaling pathway. Therefore, our investigation initiates the identification of succinate in promoting skeletal muscle protein synthesis and highlights its nutrition value and biological significance.

Materials and methods

Animals

C57BL6/J male mice were purchased from the Animal Experiment Center of Guangdong Province [permission no. 8 SYXK (Yue) 2016–0136). All experiments were conducted in accordance with ‘The Instructive Notions with Respect to Caring for Laboratory Animals’ issued by the Ministry of science and Technology of the Peoples Republic of China. All experimental protocols were approved by the College of Animal Science, South China Agricultural University. The mice were maintained under constant light for 12 h and a 12 h dark cycle at a temperature of 23±3°C during the experimental period. The mice were given access to standard pellets (crude protein 18%, crude fat 4%, and crude ash 8%). In the acute experiment, 30 8-week-old male mice were randomly divided into three groups (n=10) and injected by intraperitoneal with saline, 150 and 300 mg/kg of succinate (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 3 h. The animals were sacrificed after 3 h injection to collect gastrocnemius samples.

Cell culture and treatment

Murine skeletal muscle cell line C2C12 was cultured in high glucose DMEM (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 100,000 U/l of penicillin sodium, and 100 mg/l of streptomycin sulfate (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere that contained 5% CO2. The C2C12 myoblasts were induced differently to myotubes by a medium that contained high glucose DMEM and 2% horse serum (HS; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 6 days. The C2C12 cells were treated with the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin and Erk inhibitor U0126 for 24 h, respectively.

Total protein content

C2C12 cell were treated with 0.5 and 2 mM succinate for 48 h. Cells were washed twice with cold PBS and lysed using 200 µl radio immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer that contained protein phosphatase inhibitor complex (Biosino Bio-Technology and Science Inc., Beijing, China) and 1 mM PMSF. The total protein of the cell lysate was detected using a commercial kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and normalized through DNA content.

Myotubes diameter

C2C12 cell were treated with 0.5 and 2 mM succinate for 48 h. Cells were washed twice with cold PBS. Analyze using Nikon Eclipse Ti-s microscopy with Nis-Elements BR software (Nikon Instruments, Tokyo, Japan). Ten images were randomly captured on each coverslip (replicate sample). The diameter of each myotube (6–10) in each image was measured and used to calculate the mean myotube diameter for each sample replicate (n=5).

Puromycin assay

SUnSET method was used to measure protein synthesis in vitro and in vivo. For the in vitro study, 10 µg/ml puromycin was added to the medium 1 h before C2C12 was collected. For the in vivo study, 100 µg/ml puromycin was injected 1 h before gastrocnemius muscle tissue collection. The incorporation of puromycin in the total protein was analyzed by western blotting.

Western blot assay

C2C12 Cells were lysed in RIPA lysis buffer. And total protein concentration was tested using BCA protein assays. After separation on 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-poliacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel, the protein was transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane and blocked with 5% (wt/vol) non-fat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline that contained Tween-20 for about 2 h at room temperature. The PVDF membranes were then incubated with the indicated antibodies, including rabbit anti-β-actin (Bioss, Beijing, China) and mouse puromycin antibody 12D10 (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA); rabbit anti-phospho-mTOR (Ser2481) and mTOR, rabbit anti-phospho-S6 (Ser235/236) and S6, rabbit anti-phospho-4E-BP1 (Thr37/46) and 4E-BP1, rabbit anti-Akt, rabbit anti-phospho-Akt (Ser473), rabbit anti-phospho-Akt (Thr308), rabbit anti-eIF4E, rabbit anti-phospho-eIF4E (Ser209), rabbit anti-eIF4E, rabbit anti-phospho-eIF4E (Ser251), rabbit anti-phospho-FoxO3a, rabbit anti-FoxO3a, rabbit anti-phospho-Erk, rabbit anti-Erk. The primary antibodies were incubated at 4°C overnight and followed by the incubations of the appropriate secondary antibody (Bioss) for 1 h at room temperature. Protein expression was measured using a FluorChem M Fluorescent Imaging System (ProteinSimple, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and normalized to β-actin expression.

Immunohistochemistry

C57BL6/J mice gastrocnemius was sliced to 8–10 µm by a frozen slicer (LEICA CM 1850, Germany). The sections were rinsed 3 times in PBS and then blocked for 1 h at room temperature. Subsequently, the sections were incubated in rabbit anti-phospho-S6 (Ser235/236) overnight at room temperature. The sections were rinsed 3 times by PBS. The next day, the sections were transferred to FITC second antibody (Bioss). Sections were then observed using Nikon Eclipse Ti-s microscopy with Nis-Elements BR software (Nikon Instruments). Up to four fields of view were captured from every group.

Assay of [Ca2+]i

[Ca2+]i was measured by calcium fluorometry using fluo-8 AM. The C2C12 cells were seeded in a 24-well plate and cultured in high glucose DMEM with 2% horse serum for 6 days. The cells were washed twice with Hanks Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS, pH=7.2–7.4) containing 8 g/l NaCl, 0.4 g/l KCl, 0.1 g/l mgSO4.7H2O, 0.1 g/l MgCl2.6H2O, 0.06 g/l Na2HPO4.2H2O, 0.06 g/l K2HPO4, 1 g/l Glucose, 0.14 g/l CaCl2 and 0.35 g/l NaHCO3, and then incubated with 10 µM fluo 8-AM at 37°C. After incubation for 1 h, the C2C12 cells were washed twice with HBSS and the calcium response assay was initiated by manual addition reagent equipped with Nikon Eclipse Ti-s microscopy. Intracellular calcium responses were measured at 37°C by quantification of the fluorescence emission intensity at 525 nm after excitation of the samples at 494 nm, with data collection every 5 sec over a 180 sec period.

Co-immunoprecipitation

Lysates containing 500 µg total protein were immunoprecipitated with antibodies specific to Erk overnight at 4°C. Immune complexes were collected by incubation with a mixture of protein A- and G-Sepharose for 6 h at 4°C, the immune complexes were then washed three times with wash buffer [50 mM HEPES-NaOH (pH 7.6), 150 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Triton X-100] before being eluted in 2X sodium dodecyl sulfate sample buffer. The immune complexes were subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane for further protein detection.

Statistical analysis

All data was expressed as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Significant differences between the control and the treated group were determined by Students t-test. One-way analysis of variance was used to test the dosage effect of succinate on protein synthesis (SPSS 18.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Succinate promoted protein synthesis in C2C12 myotubes

Our study demonstrated that succinate (0.5 and 2 mM) could dose-dependently increase cellular protein levels of C2C12 cells (Fig. 1A). Further, the puromycin test result showed that 2 mM succinate significantly increased the puromycin incorporation in myotubes (Fig. 1B and C). In addition, succinate (0.5 and 2 mM) significantly increased the myotube diameter (Fig. 1D and E). These data support the hypothesis that succinate promotes protein synthesis in skeletal muscle.

Figure 1.

Succinate dose-dependently promoted protein synthesis in C2C12 myotubes. C2C12 cells were cultured in a differentiation medium for 6 days. Then C2C12 myotubes were treated with different concentrations of succinate (0, 0.05, 0.5, 1, 2 and 5 mM) for 48 h. (A) Total protein levels. (B) Puromycin incorporation detected by western blotting. (C) The statistical analyses result of the western blotting of the Puromycin. (D) The morphology of C2C12 myotubes. (E) The statistical analyses result of the C2C12 myotubes diameter. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. a-cSignificant differences between groups (P<0.05). β-actin served as a loading control.

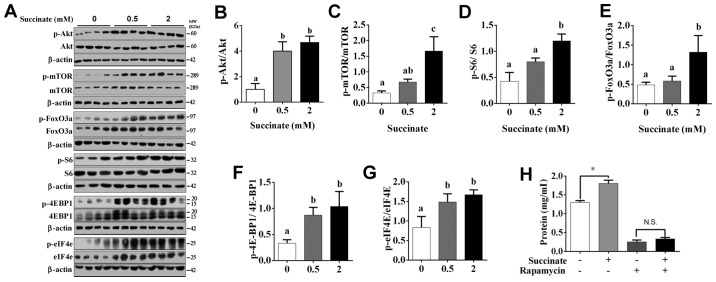

Succinate actived protein translation and suppressed protein degradation pathway in C2C12 myotubes

To further investigate the underlying mechanism, by which succinate promotes protein synthesis in C2C12 myotubes, we detected protein translation and degradation associated pathway. Western blot data showed the phosphorylation level of Akt, mTOR, S6, eIF4E, 4E-BP1 and FoxO3a were significantly increased in C2C12 myotubes when exposed to 2 mM succinate (Fig. 2A-G). Moreover, 0.5 mM succinate significantly increased the phosphorylation level of Akt, 4E-BP1, eIF4E (Fig. 2A, B, F and G). Compared to 0.5 mM succinate group, 2 mM succinate significantly increased the phosphorylation level of mTOR, S6, and FoxO3a (Fig. 2A and C-E). As expected, mTOR antagonist, rapamycin, effectively abolished succinate-induced protein synthesis (Fig. 2H). Together, the result indicates that succinate promoted protein synthesis was mediated by the activation of protein translation and inactivation of protein degradation in C2C12 myotubes.

Figure 2.

Akt/mTOR/FoxO cascade was involved in succinate-induced protein deposition in C2C12 myotubes. C2C12 cells were cultured for 6 days in a differentiation medium. C2C12 myotubes were then exposed to succinate (0.5 and 2 mM) for 48 h. (A) Western blot analysis of p-Akt, Akt, p-mTOR, mTOR, p-FoxO3a, FoxO3a, p-S6, S6, p-4EBP1, 4EBP1, p-eIF4e and eIF4e. (B-G) The statistical analyses results of the western blotting of the phosphorylation level of Akt, mTOR, FoxO3a, S6, 4E-BP1 and eIF4e. (H) The total protein level after C2C12 cells were co-treated with succinate and rapamycin. a,bSignificant differences between groups (P<0.05). *P<0.05 compared with the control. β-actin was used as a loading control.

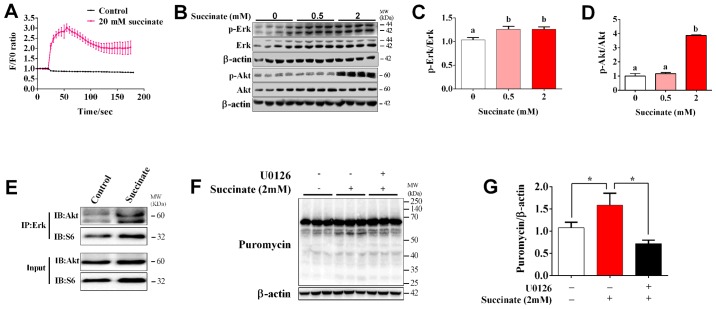

The role of Erk/Akt signaling pathway in succinate-induced protein synthesis in C2C12 myotubes

To determine whether Ca2+ and Erk signaling pathway are involved in succinate-induced protein synthesis, we first detected the dynamic change of intracellular Ca2+ concentration. The result showed that succinate dramatically increased [Ca2+]i and reached the maximal level at 30s post treatment (Fig. 3A). When compared to control, 2 mM succinate remarkably increased the phosphorylation level of Erk and Akt, while 0.5 mM succinate only remarkably increased the phosphorylation level of Erk (Fig. 3B-D). In addition, 2 mM succinate also significantly increased the phosphorylation level of Akt compared to 0.5 mM succinate group (Fig. 3D). We further test the crosstalk between Erk and Akt cascade by co-Immunoprecipitation. It was interesting to find that succinate obviously promoted the binding of Erk with Akt, but not that of Erk with S6 (Fig. 3E). Moreover, U0126, an Erk inhibitor, could reverse succinate induced protein synthesis in C2C12 myotubes (Fig. 3F and G). These data indicated that Erk is crucial for succinate-induced activation of Akt cascade and enhancement of protein synthesis.

Figure 3.

Succinate induced protein synthesis in C2C12 myotubes was mediated by Erk signaling pathway. C2C12 cells were cultured in a differentiation medium for 6 days. (A) [Ca2+]i in C2C12 cells in response to succinate (20 mM). (B-D) C2C12 myotubes were exposed to succinate (0.5 and 2 mM) for 48 h. Western blot analysis of p-Akt and p-Erk. (E) The binding of Erk with Akt was tested by co-Immunoprecipitation. (F and G) Erk inhibitor U0126 (10 µM) was co-treated with succinate (2 mM) for 48 h. Puromycin levels were detected. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. a,bSignificant differences between groups (P<0.05). *P<0.05 compared with the control or succinate group. β-actin was used as a loading control.

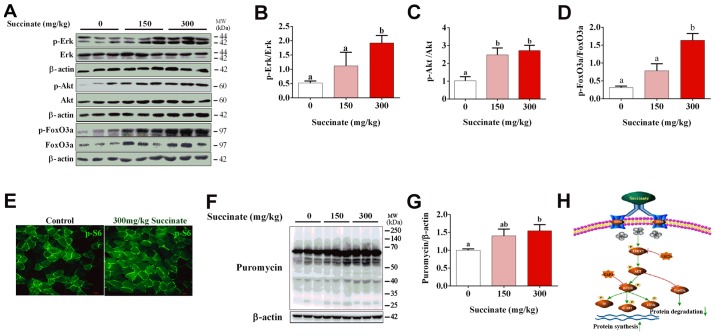

Succinate increased protein synthesis in the skeletal muscle of mice

To further confirm the effect of succinate on protein synthesis in vivo, C57BL6/J mice were injected with 150 and 300 mg/kg succinate, respectively. Consistent with previous in vitro data, 300 mg/kg succinate could significantly increase the phosphorylation level of Erk, Akt and FoxO3a in gastrocnemius muscle compared to control, while 150 mg/kg succinate could significantly increase the phosphorylation level of Akt (Fig. 4A-D), as well as protein synthesis (Fig. 4F and G). Further, 300 mg/kg succinate significantly increased the phosphorylation level of Erk and FoxO3a when compared to 150 mg/kg succinate group (Fig. 4A, B and D). Moreover, immunohistochemistry data illustrated that 300 mg/kg succinate increased phosphor-S6 levels in gastrocnemius tissue (Fig. 4E). The mechanism picture that succinate promotes the protein synthesis of skeletal muscle myotubes (Fig. 4H). These data verified that succinate increased protein synthesis and deposition in the skeletal muscle of mice.

Figure 4.

Succinate increased protein synthesis in the skeletal muscle of C57 BL mice. Thirty 8-week-old male mice were randomly divided into three groups (n=10). Different concentrations of succinate (0, 150 and 300 mg/kg) were injected in intraperitoneal for 3 h. (A-D) Expression of p-Erk, p-Akt and p-FoxO3a were detected by western blotting. (E) Expression of p-S6 in the gastrocnemius of mice by immunoflurescence. (F and G) Puromycin incorporation levels in gastrocnemius detected by western blotting. (H) The mechanism picture that succinate promotes the protein synthesis of skeletal muscle myotubes. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. a,bSignificant differences between groups (P<0.05). β-actin was used as a loading control.

Discussion

Classically, hormones and nutrients, for example insulin-like growth factors-1 (IGF-1) and amino acids, are crucial regulator for skeletal muscle protein synthesis (21). It should be emphasized that several metabolites of animo acids and TCA cycle, such as α-ketoisocaproate, β-hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate and α-ketoglutarate, have also been identified to enhance skeletal muscle growth by increasing protein synthesis and inhibiting protein degradation (3,22,23). Succinic acid is another key TCA cycle metabolite, of which exercise could dramatically increase the content (14). In this paper, we firstly identified that succinate could significantly promote protein synthesis in vitro and in vivo, accompanished with activation of Akt/mTOR/S6 cascade and inhibition of FoxO3a.

Succinate is the endogenous ligand for GPR91, which mediated the effect of succinate on muscle hypertrophy (24), protein deposition (25) and metabolism regulation (26). Both the mRNA and protein level of GPR91 are ubiquitously expressed in many tissues, including skeletal muscle (27), which indicates this receptor and its downstream signaling pathway might be involved in succinate induced skeletal hypertrophy. Once activated by succinate, GPR91 recruited Gαi protein to inhibit cAMP production and increase intracellular Ca2+ (17). As expected, we detected a dramatic elevation of [Ca2+]i of C2C12 myotubes in response to succinate treatment, which might be the explaination to elucidate effect of succinate on protein synthesis.

Skeletal muscle protein deposition is regulated by multiple signaling pathways (28,29). Among those, Erk1/2 pathway represented extracellular signal in protein synthesis (30,31), which was sensitive to transient elevation of [Ca2+]i (32). It has been reported activation of GPR91 triggered [Ca2+]i elevation and subsequently, the activation of Erk (33). In consistent with previous evidence, we confirmed that succinate dose-dependently increased phospho-Erk level in vitro and in vivo. Moreover, our co-IP data also found that succinate obviously promoted the binding of Erk with Akt. Notably, either Erk antagonist (U0126) or mTOR inhibitor (rapamycin) could abolish the effect of succinate on protein synthesis.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that succinate promoted skeletal muscle protein synthesis through Erk/Akt signaling pathway.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by National Basic Research Program of China (no. 2013CB127306), National Key Point Research and Invention Program (2016YFD0501205) and National Nature Science foundation of China (no. 31572480).

References

- 1.Fanzani A, Conraads VM, Penna F, Martinet W. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of skeletal muscle atrophy: An update. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2012;3:163–179. doi: 10.1007/s13539-012-0074-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sandri M. Signaling in muscle atrophy and hypertrophy. Physiology (Bethesda) 2008;23:160–170. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00041.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cai X, Zhu C, Xu Y, Jing Y, Yuan Y, Wang L, Wang S, Zhu X, Gao P, Zhang Y, et al. Alpha-ketoglutarate promotes skeletal muscle hypertrophy and protein synthesis through Akt/mTOR signaling pathways. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26802. doi: 10.1038/srep26802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 4.Egerman MA, Glass DJ. Signaling pathways controlling skeletal muscle mass. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;49:59–68. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2013.857291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brooks NE, Myburgh KH. Skeletal muscle wasting with disuse atrophy is multi-dimensional: The response and interaction of myonuclei, satellite cells and signaling pathways. Front Physiol. 2014;5:99. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuentes EN, Einarsdottir IE, Paredes R, Hidalgo C, Valdes JA, Björnsson BT, Molina A. The TORC1/P70S6K and TORC1/4EBP1 signaling pathways have a stronger contribution on skeletal muscle growth than MAPK/ERK in an early vertebrate: Differential involvement of the IGF system and atrogenes. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2015;210:96–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2014.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schiaffino S, Dyar KA, Ciciliot S, Blaauw B, Sandri M. Mechanisms regulating skeletal muscle growth and atrophy. FEBS J. 2013;280:4294–4314. doi: 10.1111/febs.12253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.White JP, Gao S, Puppa MJ, Sato S, Welle SL, Carson JA. Testosterone regulation of Akt/mTORC1/FoxO3a signaling in skeletal muscle. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2013;365:174–186. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2012.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crossland H, Constantin-Teodosiu D, Gardiner SM, Constantin D, Greenhaff PL. A potential role for Akt/FOXO signalling in both protein loss and the impairment of muscle carbohydrate oxidation during sepsis in rodent skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2008;586:5589–5600. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.160150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Z, Long W, Fryburg DA, Barrett EJ. The regulation of body and skeletal muscle protein metabolism by hormones and amino acids. J Nutr. 2006;136(1 Suppl):212S–217S. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.1.212S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suryawan A, Davis TA. Regulation of protein degradation pathways by amino acids and insulin in skeletal muscle of neonatal pigs. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2014;5:8. doi: 10.1186/2049-1891-5-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sugden PH, Fuller SJ. Regulation of protein turnover in skeletal and cardiac muscle. Biochem J. 1991;273:21–37. doi: 10.1042/bj2730021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suryawan A, Davis TA. Regulation of protein synthesis by amino acids in muscle of neonates. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2011;16:1445–1460. doi: 10.2741/3798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Schaardenburgh M, Wohlwend M, Rognmo Ø, Mattsson EJ. Mitochondrial respiration after one session of calf raise exercise in patients with peripheral vascular disease and healthy older adults. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0165038. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsai HH, Chang SC, Chou CH, Weng TP, Hsu CC, Wang JS. Exercise training alleviates hypoxia-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in the lymphocytes of sedentary males. Sci Rep. 2016;6:35170. doi: 10.1038/srep35170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tretter L, Patocs A, Chinopoulos C. Succinate, an intermediate in metabolism, signal transduction, ROS, hypoxia, and tumorigenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1857:1086–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2016.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sundström L, Greasley PJ, Engberg S, Wallander M, Ryberg E. Succinate receptor GPR91, a Gα(i) coupled receptor that increases intracellular calcium concentrations through PLCβ. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:2399–2404. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.05.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aguiar CJ, Andrade VL, Gomes ER, Alves MN, Ladeira MS, Pinheiro AC, Gomes DA, Almeida AP, Goes AM, Resende RR, et al. Succinate modulates Ca(2+) transient and cardiomyocyte viability through PKA-dependent pathway. Cell Calcium. 2010;47:37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Espinosa A, Leiva A, Peña M, Müller M, Debandi A, Hidalgo C, Carrasco MA, Jaimovich E. Myotube depolarization generates reactive oxygen species through NAD(P)H oxidase; ROS-elicited Ca2+ stimulates ERK, CREB, early genes. J Cell Physiol. 2006;209:379–388. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.May C, Weigl L, Karel A, Hohenegger M. Extracellular ATP activates ERK1/ERK2 via a metabotropic P2Y1 receptor in a Ca2+ independent manner in differentiated human skeletal muscle cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;71:1497–1509. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishida H, Ikegami A, Kaneko C, Kakuma H, Nishi H, Tanaka N, Aoyama M, Usami M, Okimura Y. Dexamethasone and BCAA failed to modulate muscle mass and mTOR signaling in GH-deficient rats. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0128805. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang Q, He L, Hou Y, Chen J, Duan Y, Deng D, Wu G, Yin Y, Yao K. Alpha-ketoglutarate enhances milk protein synthesis by porcine mammary epithelial cells. Amino Acids. 2016;48:2179–2188. doi: 10.1007/s00726-016-2249-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duan Y, Li F, Li Y, Tang Y, Kong X, Feng Z, Anthony TG, Watford M, Hou Y, Wu G, Yin Y. The role of leucine and its metabolites in protein and energy metabolism. Amino Acids. 2016;48:41–51. doi: 10.1007/s00726-015-2067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilissen J, Jouret F, Pirotte B, Hanson J. Insight into SUCNR1 (GPR91) structure and function. Pharmacol Ther. 2016;159:56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2016.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.He W, Miao FJ, Lin DC, Schwandner RT, Wang Z, Gao J, Chen JL, Tian H, Ling L. Citric acid cycle intermediates as ligands for orphan G-protein-coupled receptors. Nature. 2004;429:188–193. doi: 10.1038/nature02488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Littlewood-Evans A, Sarret S, Apfel V, Loesle P, Dawson J, Zhang J, Muller A, Tigani B, Kneuer R, Patel S, et al. Sarret GPR91 senses extracellular succinate released from inflammatory macrophages and exacerbates rheumatoid arthritis. J Exp Med. 2016;213:1655–1662. doi: 10.1084/jem.20160061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Castro Fonseca M, Aguiar CJ, da Rocha Franco JA, Gingold RN, Leite MF. GPR91: Expanding the frontiers of Krebs cycle intermediates. Cell Commun Signal. 2016;14:3. doi: 10.1186/s12964-016-0126-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ato S, Makanae Y, Kido K, Fujita S. Contraction mode itself does not determine the level of mTORC1 activity in rat skeletal muscle. Physiol Rep. 2016;4(pii):e12976. doi: 10.14814/phy2.12976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agergaard J, Bülow J, Jensen JK, Reitelseder S, Drummond MJ, Schjerling P, Scheike T, Serena A, Holm L. Light-load resistance exercise increases muscle protein synthesis and hypertrophy signaling in elderly men. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2017;312:E326–E338. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00164.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Osterweil EK, Krueger DD, Reinhold K, Bear MF. Hypersensitivity to mGluR5 and ERK1/2 leads to excessive protein synthesis in the hippocampus of a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. J Neurosci. 2010;30:15616–15627. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3888-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quan-Jun Y, Yan H, Yong-Long H, Li-Li W, Jie L, Jin-Lu H, Jin L, Peng-Guo C, Run G, Cheng G. Selumetinib attenuate skeletal muscle wasting in murine cachexia model through ERK inhibition and AKT activation. Mol Cancer Ther. 2017;16:334–343. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-16-0324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hegedũs L, Garay T, Molnár E, Varga K, Bilecz Á, Török S, Padányi R, Pászty K, Wolf M, Grusch M, et al. The plasma membrane Ca2+ pump PMCA4b inhibits the migratory and metastatic activity of BRAF mutant melanoma cells. Int J Cancer. 2017;140:2758–2770. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aguiar CJ, Rocha-Franco JA, Sousa PA, Santos AK, Ladeira M, Rocha-Resende C, Ladeira LO, Resende RR, Botoni FA, Melo M Barrouin, et al. Succinate causes pathological cardiomyocyte hypertrophy through GPR91 activation. Cell Commun Signal. 2014;12:78. doi: 10.1186/s12964-014-0078-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]