Abstract

Markers of sleep drive (<10Hz; slow wave activity and theta) have been identified in the course of slow wave sleep (SWS) and wakefulness. So far, higher frequencies in the waking electroencephalogram have not been examined thoroughly as a function of sleep drive. Here, we measured EEG dynamics in epochs of active wake (AW; wake characterized by high muscle tone) or quiet wake (QW; wake characterized by low muscle tone). We hypothesized that the higher beta oscillations (15-35Hz, measured by local field potential and electroencephalography) represent fundamentally different processes in AW and QW.

In AW, sensory-stimulation elevated beta activity in parallel with gamma (80-90Hz) activity, indicative of cognitive processing. In QW, beta activity paralleled slow wave activity (1-4Hz) and theta (5-8Hz) in tracking sleep need. Cerebral lactate concentration, a measure of cerebral glucose utilization, increased during AW whereas it declined during QW. Mathematical modeling of state-dependent dynamics of cortical lactate concentration was more precisely predictive when QW and AW were included as two distinct substates rather than a uniform state of wakefulness. The extent to which lactate concentration declined in QW and increased in AW was proportionate to the amount of beta activity.

These data distinguish QW from AW. QW, particularly when characterized by beta activity, is permissive to metabolic and electrophysiological changes that occur in SWS. These data urge further studies on state dependent beta oscillations across species.

Keywords: sleep homeostasis, vibrissal sensory activation, sleep deprivation, insomnia

INTRODUCTION

Synchronous firing of neurons is a key feature of brain activity (Steriade et al. 1993, Buzsaki and Draguhn 2004, Wisor et al. 2013) and is used to distinguish wakefulness from sleep. Waking behavior can be further segregated into an active state associated with alertness and active exploration to a quiet state devoid of locomotion. During active wake (AW) the electroencephalogram (EEG) and local field potentials (LFP) show a desynchronized state dominated by fast frequencies, whereas quiet wake (QW) show mixed frequencies with spontaneous activity in the lower frequencies, although the amplitude of these slow oscillations is smaller than those observed during slow wave sleep (SWS) (Crochet and Petersen 2006, Niell and Stryker 2010).

Sleep drive rises progressively with time spent awake and declines during sleep. The classic marker of the homeostatic sleep drive has been slow wave activity (SWA; 0.5 - 4Hz) in the course of SWS (Borbely 1982). Markers of sleep drive (SWA and theta; 4-8 Hz) have also been identified in the course of wakefulness (Aeschbach et al. 1997, Vyazovskiy and Tobler 2005). So far, higher frequencies in the waking EEG have not been examined thoroughly as a function of sleep drive. This may be based on literature suggesting that activity in the higher beta (15-35Hz) and gamma (35-45Hz in humans) frequencies is associated with sensory events and information processing during wakefulness (Bouyer et al. 1981, Basar-Eroglu et al. 1996). Interestingly, polysomnographic studies in insomniacs report elevated beta activity, but not gamma activity, prior to sleep onset (Freedman 1986, Perlis et al. 2001, Perlis et al. 2001, Strijkstra et al. 2003). Abnormally high beta activity has been hypothesized to indicate a hyperaroused central nervous system (Perlis et al. 2001, Perlis et al. 2001). Another way to interpret these findings is that beta activity represents a distinct process when measured in the context of quiet wakefulness prior to sleep onset.

We hypothesized that beta oscillations represent fundamentally different processes depending on whether they occur in AW or QW. Specifically, we propose that beta oscillations measure sensory processing during AW, but track sleep drive during QW. To test this hypothesis in a mouse model, we subdivided the waking epochs during a 6h sleep deprivation (SD) protocol into QW and AW. The SD protocol consisted of cycles of systematically varying sensory input (active whisker stimulation vs gentle handling) alternating with periods of recovery. Effects of sensory processing and sleep drive on waking EEG dynamics were identified by measuring SWA, theta, alpha (9-12Hz), beta and gamma (80-90Hz) activity in QW and AW across SD and recovery cycles. The data demonstrate a dichotomy in beta EEG dynamics in AW and QW. Different EEG dynamics in AW and QW raised the possibility that there may be a metabolic difference between the waking states. To address this possibility, we investigated whether changes in cerebral lactate concentration vary as a function of waking substate, and whether these cortical metabolic changes vary as a function of beta oscillations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the institutional animal care and use committee of Washington State University (Protocol Number: 3932) and conducted in accordance with National Research Council guidelines and regulations controlling experiments in live animals (Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, 1996).

Animals and surgery procedures

Male mice (B6.Cg-Tg(Thy1-COP4/eYFP)18Gfng/J X CD1(Thy1×CD1)) expressing the blue light-activated cation channel Channelrhodopsin2 in cortical pyramidal neurons (Arenkiel et al. 2007) were anaesthetized with isoflurane (5% induction; 1-3 % to maintain 0.5-1 Hz respiration rate) for implantation of stainless steel EEG electrode (right frontal cortex; bregma coordinates: A=3.0, L=1.5). LFP and lactate concentration were recorded in the left vibrissal somatosensory cortex (P=1.7, L=3.0, H=−1.0; Aronoff et al., 2010). For dual LFP and lactate recording, a stainless steel polyimide-insulated depth electrode (Plastics One part #E363/1/SPC, diameter: 0.280mm) was glued to the shaft of the guide cannula for the lactate sensor (Plastics One part #C312GSPC) with the tip of the guide cannula resting on the dura (Clegern et al. 2012, Wisor et al. 2012). Successful targeting of vibrissal somatosensory cortex was verified by optogenetic stimulation during surgery, resulting in contralateral whisker twitching. Reference electrode was placed over the cerebellum (P=3.0). Electromyogram (EMG) electrodes were implanted bilaterally in the nuchal muscle. Analgesic (Buprenorphine; 0.1mg/kg, s.c.) and anti-inflammatory (flunixin meglumine; 0.1mg/kg, s.c.) agents were given two days post-surgery. At least two weeks were allowed following surgery for recovery. Mice were kept on a 12h light/12h dark schedule with lights on at 06:00h (zeitgeber, ZT0).

Experimental protocol

Mice were acclimatized to the cylindrical recording cage for one night (diameter 25cm×height 20cm). A precalibrated enzymatic lactate sensor was inserted immediately prior to 24-hr baseline recording. At the end of the 24-hr baseline, one group of mice were restrained by hand for approximately 1-min and subjected to bilateral whisker trim to eliminate vibrissal sensory input during gentle handling thereafter (‘GH’, n=10). The other group was restrained for an equivalent duration but not subjected to whisker trim (‘WHISK’, n=10). These manipulations were followed immediately by 6 cycles of 30-min SD and 30-min spontaneous sleep/wake (recovery), in total 6h (ZT4 to ZT10). Sleep deprivation (SD) was performed by whisker stimulation in WHISK mice and by gentle handling (GH) in vibrissal sensory-deprived mice. The investigator was assigned to gently brush the vibrissae, bilaterally (WHISK) or gently stimulate the posterior half of the body (GH) at a rate of about 30 times per minute. Recovery sleep was recorded for 18-hrs.

Data collection, processing and analysis

Frontal EEG, somatosensory LFP, lactate concentration and EMG were simultaneously monitored and sampled with rate of 400 Hz. Signals were fed into a PCB-based preamplifier (Pinnacle Technology part #8406-SL), amplified by 100-fold and conveyed to a commutator (Pinnacle Technology part #8401).

Sleep and wakefulness states

Sleep stages were classified and power spectral analysis was performed offline with Neuroscore software (version 2.0.1, DataSciences Inc.,US). Sleep stages were scored in 10-sec epochs by use of frontal EEG signal filtered with high-pass: 0.5Hz, low pass: 30Hz. EMG signal was high-pass filtered at 10Hz using standard EEG and EMG criteria (Wisor et al. 2012).

Power spectral analysis was performed offline by fast Fourier Transform (FFT) analysis on unfiltered EEG and LFP signals on each 10-sec epoch segregated into 2-sec intervals with a Hamming window and 50% overlap, yielding an average power value for the 10-sec epoch. Artifacts were removed in two steps: 1) visual inspection of EEG signals where all epochs containing electrical artifacts were excluded; and 2) automated algorithm detecting epochs with EEG power values exceeding the mean value by >8 standard deviations. In all files, <5% of epochs were eliminated from analysis.

Lactate concentration data

For real-time cerebral lactate measurements an enzyme-based amperometric biosensor was used with a sampling rate of 1Hz. See detailed descriptions of the protocol including calibration (Clegern et al. 2012), averaging and artefact handling (Wisor et al. 2012, Rempe and Wisor 2014).

For the state-specific lactate dynamics of each vigilance state (AW, QW, SWS and REMS) in Figure 7, current was averaged across 2-min intervals of each single state. Lactate dynamics in the transitions QW-to-AW and QW-to-SWS were assessed by identifying all 1-min intervals of QW followed by either 1-min of AW or 1-min of SWS (Figure 8). Lactate concentration was normalized to the mean of values across each specific interval. These normalized curves were averaged across all such intervals for each animal.

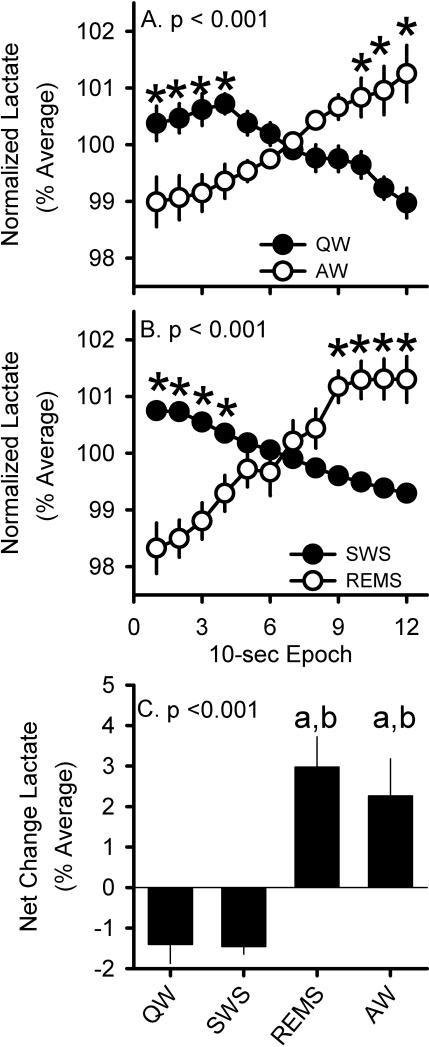

Figure 7.

State-dependent changes in lactate concentration. A) Across 2-min intervals of AW (white circles) or QW (black circles). B) Across 2-min intervals of REMS (white circles) or SWS (black circles). C) Net change across 2-min intervals of each state. ‘a’ denotes significant difference from QW and ‘b’ significant difference from SWS, n=20.

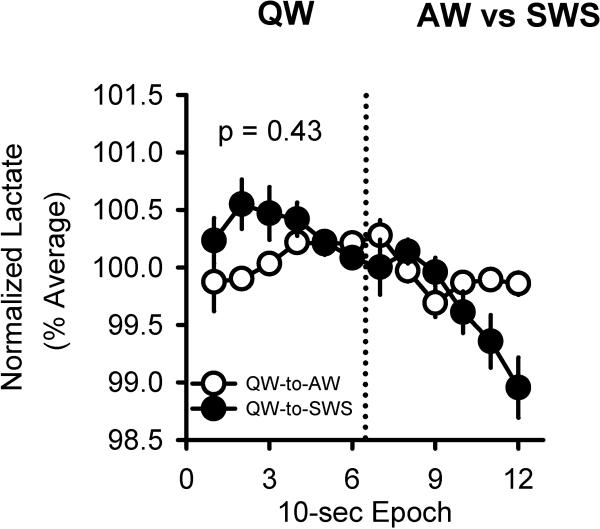

Figure 8.

Lactate concentration across 1-min of QW followed by 1-min of AW (white) or 1-min of QW followed by 1-min of SWS (black). P-value; interaction effect (transition typeXepochs) on lactate during QW (i.e., first minute shown). Note: lactate concentration has a time delay of minimum 30-sec relative to EEG changes (Wisor et al. 2012), n=20.

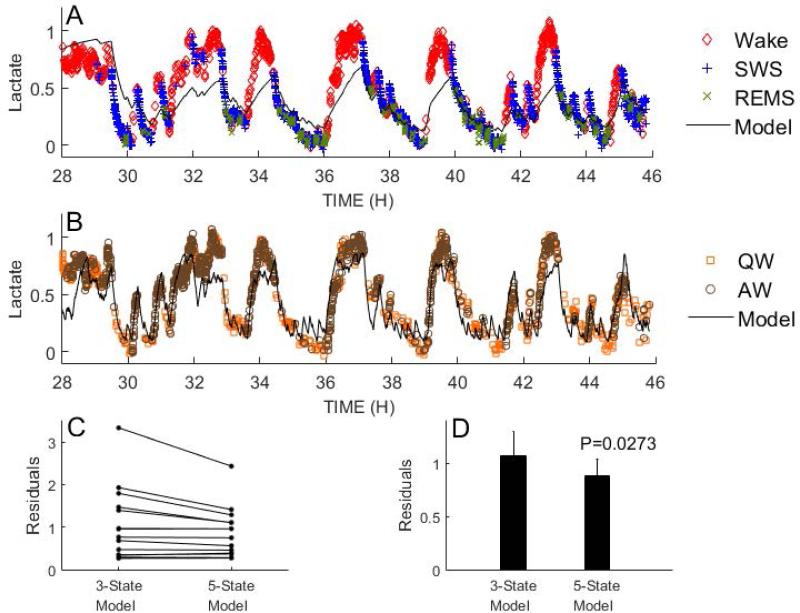

Temporal dynamics of lactate were modelled using the averaged current within each 10-sec epoch of wake, SWS and REMS (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

A 5-state homeostatic model (panel B) fits lactate data better than a 3-state model (panel A). Each data point is color-coded for state. In panel B, only epochs scored as quiet wake (QW) or active wake (AW) are plotted. In nearly every recording, the residuals (a measure of how well the model fits the data), were lower using the 5-state model than the 3-state model (panel C). Panel D shows the average residuals for the two models, n=14.

Quiet wake and active wake

All epochs of wakefulness were subdivided using EMG peak-to-peak values. QW epochs were defined as EMG≤33rd percentile. Wake epochs exhibiting EMG≥66th percentile were reclassified as AW. This criterion was sufficient to exclude epochs with high locomotor activity from QW and demonstrate unique electrophysiological changes between QW and AW, across frequency bands and cortices. See Figure 1 and 2, supporting information. Remaining wake epochs in between 33rd and 66th percentiles were not included in analyses of QW vs. AW.

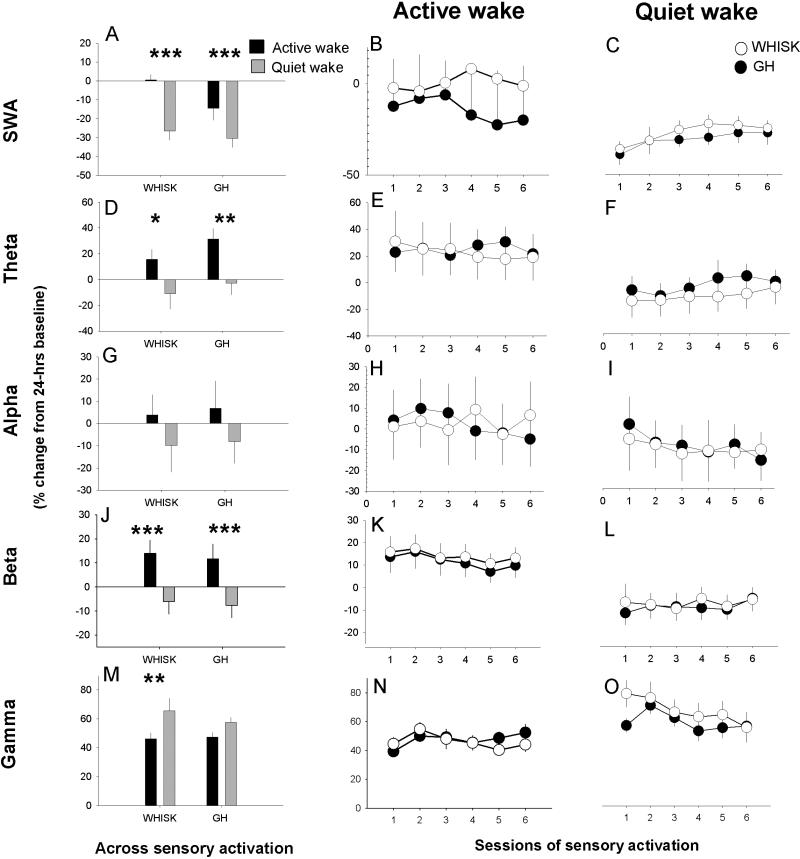

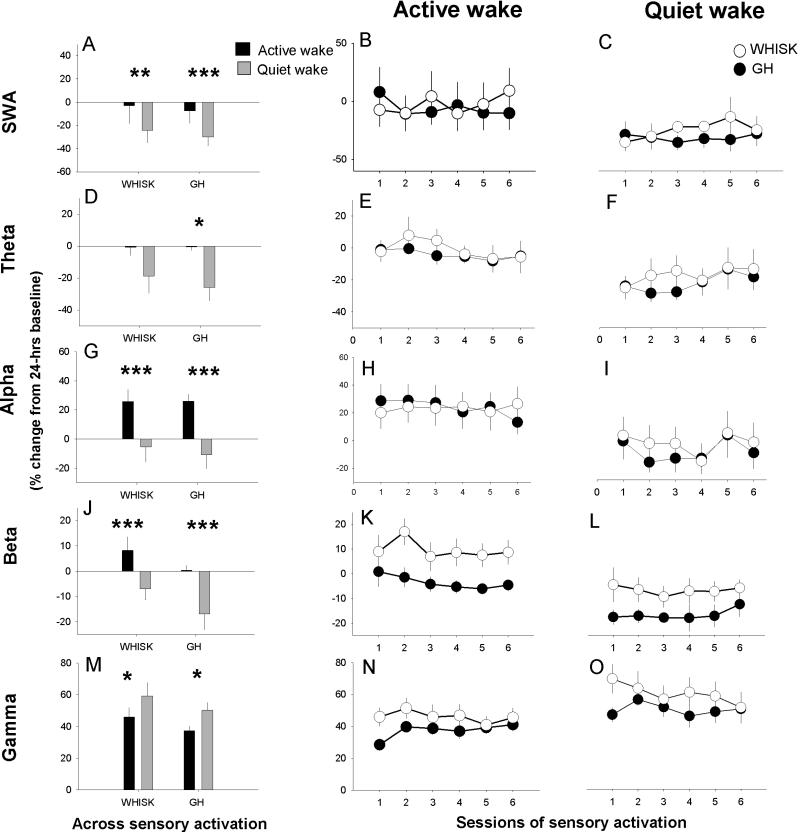

Figure 1.

Effects of sensory stimulation on EEG dynamics in frontal cortex. Left panels (A, D, G, J and M) indicate normalized and averaged values during active and quiet wake. Time course of EEG power during sessions of sensory activation are shown in the middle (active wake; B, E, H, K and N) and right panels (quiet wake; C, F, I, L and O) in WHISK mice (n=10) and gentle handled (GH) mice (n=10). Data are shown as percent change compared to 24h baseline. Asterisks indicate significant differences between active wake and quiet wake. Group differences were not detected.

Figure 2.

Effects of sensory stimulation on LFP dynamics in somatosensory cortex. Panels are analogous to Figure 1. See Figure 1 legend for further details.

High and low amount of beta power

QW and AW were further categorized based on beta activity in the somatosensory LFP as high amount of beta power (≥75th percentile) vs. low amount of beta power (≤25th percentile), resulting in four distinct classifications: Low Amount Beta-QW, High Amount Beta-QW, Low Amount Beta-AW and High Amount Beta-AW. Two-minute intervals in which the majority of epochs were categorized as one of these four classifications were identified.

Mathematical model for slow wave sleep and lactate dynamics

Temporal dynamics of lactate were modelled using a modification of a generalized homeostatic model (Rempe and Wisor 2014). In the previous 3-state model, it was assumed that lactate concentration increases exponentially across epochs of wake and REMS with time constant τi and decreases exponentially across epochs of SWS with time constant τd. Here, the model was modified to include AW and QW; 5-state model. It is assumed that in desynchronized states (AW, W and REMS) lactate concentration increases at a rate τi, while in synchronized states (SWS and QW) lactate concentration decreases at a rate τd The equations are as follows:

Lt: cerebral lactate concentration at time step t; UA: upper asymptote; LA: lower asymptote; Δt: time step; τi and τd : time constant for the rising and falling of L respectively. The variable L always remains between UA and LA. To account for decay in the lactate sensor readout over time, the upper and lower asymptotes (UA and LA, respectively), are functions of time rather than constants. The Nelder-Mead method (Nelder and Mead 1965) was utilized to find the optimal values of of τi and τd, minimizing the sum of squares residuals between the simulation and the data Rempe and Wisor (2014).

Statistics

All significant overall effects of repeated measures ANOVA were further tested with Fisher LSD post hoc test. Pearson's product-moment correlation coefficients were calculated to test for associations between change in SWA, beta and gamma across SD and recovery, in a pooled sample of WHISK and GH. Significance level was α≤0.05. Data are presented as mean±SEM. EEG dynamics are reported as %change relative to the 24-hr baseline recording.

The software package MATLAB (The Math Works, Inc., USA) was used for analysis and modelling and Statistica version 12 was used for statistics.

RESULTS

Statistical main effects are shown in Table 1 and 2, supporting information.

Table 1.

Association between cortical network oscillations across sessions of sleep deprivation and recovery

| Sensory activation | Recovery | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Somatosensory cortex | Frontal cortex | Somatosensory cortex | Frontal cortex | ||||||

| State | Freq Band | Beta | SWA | Beta | SWA | Beta | SWA | Beta | SWA |

| QW | SWA | NS | r = 0.62** | NS | r = 0.62** | ||||

| Gamma | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | r = −0.44* | r = −0.41¥ | r = −0.67*** | |

| AW | SWA | NS | NS | NS | r = 0.45* | ||||

| Gamma | r = 0.84*** | NS | r = 0.67*** | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | |

Pearsons correlation coefficients for EEG frequency bands during QW and AW.

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

indicate p=0.07, NS: non-significance.

Sensory activation drives beta activity in AW

Sensory activation affected electrophysiological dynamics differently in AW than QW, in both frontal and somatosensory cortex (SWA: F(1,18)>25.1, p<0.001; theta: F(1,18)>25.9, p<0.001; beta: F(1,18)>93.4, p<0.001; gamma: F(1,18)>13.2, p<0.002. Alpha dynamics differed only in somatosensory cortex: F(1,18)>17.4, p=0.007. See Fig.1-2).

In the frontal cortex EEG, sessions of sensory activation increased theta and beta activity in AW (Fig.1 D,E,J,K), irrespective of stimulation type (WHISK or GH). By contrast, when animals were in the state of QW during the sensory activation, theta and beta activity decreased (p<0.05, Fig.1 D,F,J,L). SWA was reduced in both QW and AW, albeit to a greater extent in QW compared to AW (p<0.0036, both stimulation types; Fig.1A-C) and gamma activity increased relative to baseline in both AW and QW irrespective of stimulation type (Fig.1M-O). Alpha activity in AW did not change significantly during sensory activation (Fig.1 G-I).

Stimulus type affected beta activity in the somatosensory cortex LFP differentially compared to frontal EEG. Whisker stimulation increased LFP beta activity compared to GH, in AW only (F(1,18)=7.8, p=0.012; Fig.2J,K). This stimulus-specific difference was not significant during QW (F(1,18)<3.5, p>0.077; Fig.2J,L). Changes in SWA (decrease) and gamma activity (increase) were similar to frontal EEG. Both stimulation types increased alpha activity in AW (Fig.2G,H).

It may be argued that the stimulation types in the two SD procedures differed in intensity across sessions, affecting the movement of the animal. We did not find that stimulation type (GH vs WHISK) significantly affected the number of behavioral state shifts (AW-to-QW or QW-to-AW), during SD sessions (F(1,18)<0.3, p>0.57) or recovery sessions (F(1,18)<0.8, p>0.39). Moreover, the data demonstrate that somatosensory circuit-specific activation in the beta range is an exclusive characteristic of AW. Furthermore, the fact that only the somatosensory LFP and not frontal EEG (F(1,18)=0.2, p=0.67; Fig.1J,K) exhibited a stimulus type-specific effect during AW indicates that the stimulus types did not differ with respect to their overall arousing or stress-provoking effects.

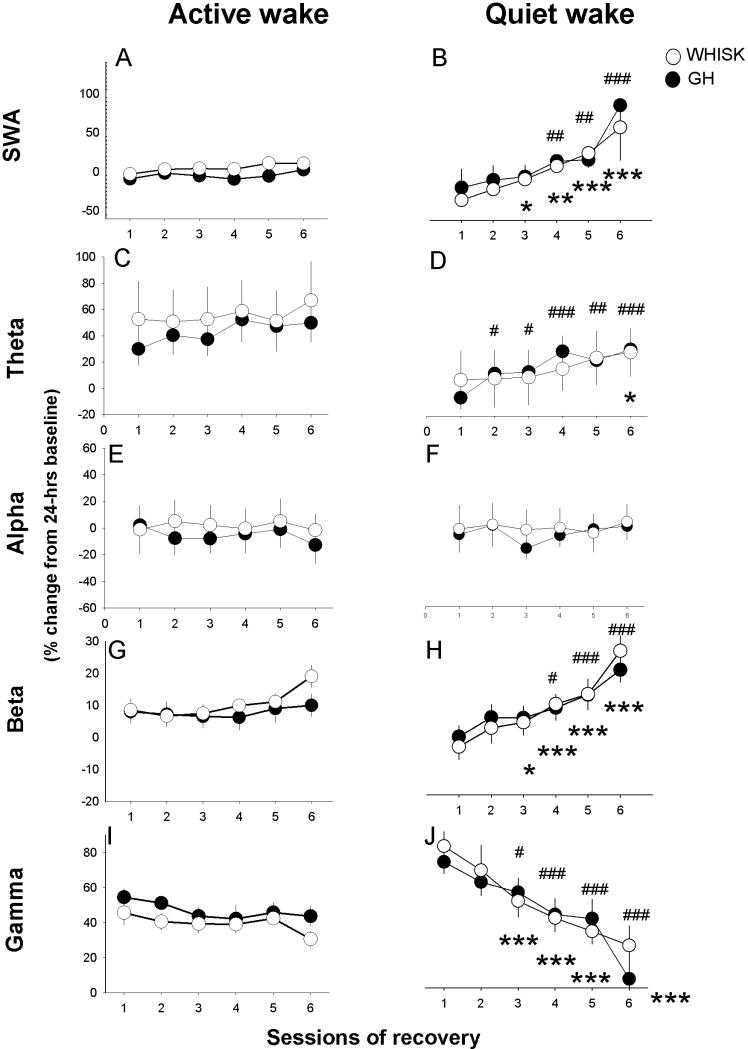

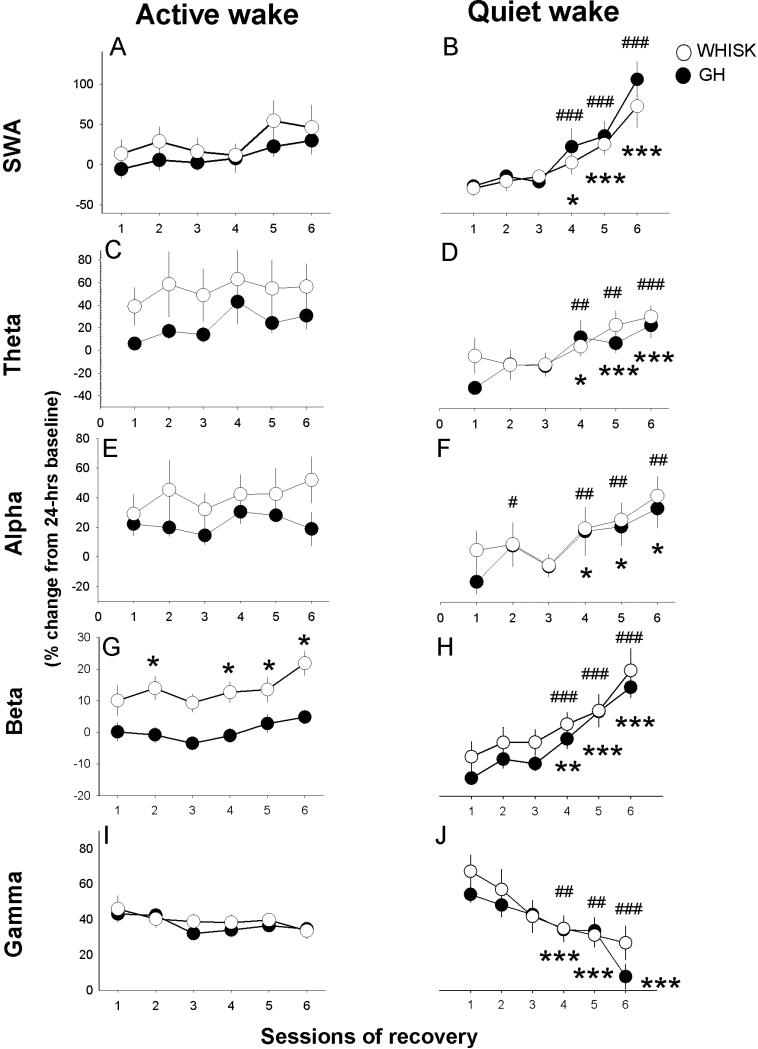

Increasing sleep drive affects SWA, theta and beta activity globally, during QW only

By alternating sensory stimulation and recovery, we tested the hypothesis that sleep drive is manifested in beta activity during QW. When wake was analyzed as a unitary state, only SWA showed a main effect of sessions during recovery, both in somatosensory and frontal cortex. Distinguishing AW and QW revealed effects of session number on SWA, theta, beta and gamma frequency bands, but only in the QW state (Fig.3,4). During QW, SWA, theta and beta activity progressively increased across sessions of recovery, in parallel with decreased gamma activity. This change was global, as it was seen in both the frontal EEG (Fig.3B,D,H) and the somatosensory LFP (Fig.4B,D,H). Alpha activity showed a progressive increase only in the somatosensory LFP (Fig.3F,4F). In addition to being restricted to QW, these effects were only detected in recovery sessions, when animals did not undergo experimenter-enforced sensory stimulation (Fig.1,2). In the state of AW, none of the frequency bands changed across sessions, in either cortical region, other than a modest increase in beta activity in somatosensory cortex (Fig.4G).

Figure 3.

Time course of EEG power in active wake (left panel) and quiet wake (right panel) during sessions of recovery from sensory activation in frontal cortex. Significant differences compared to the first session are indicated with asterisks for WHISK mice (n=10) and squares for GH mice (n=10). Data are shown as percent change compared to 24h baseline. Group differences were not detected.

Figure 4.

Time course of EEG power in active wake (left panel) and quiet wake (right panel) during sessions of recovery from sensory activation in somatosensory cortex. See Figure 3 legend for more details.

WHISK exhibited high beta activity in AW during sensory activation during recovery sessions as well (F(1,18)=7.8, p=0.012; Fig.2J,K and 4G). This demonstrates active sensory processing within the somatosensory cortex during AW exclusively, whether the stimulation is enforced by the experimenter or not.

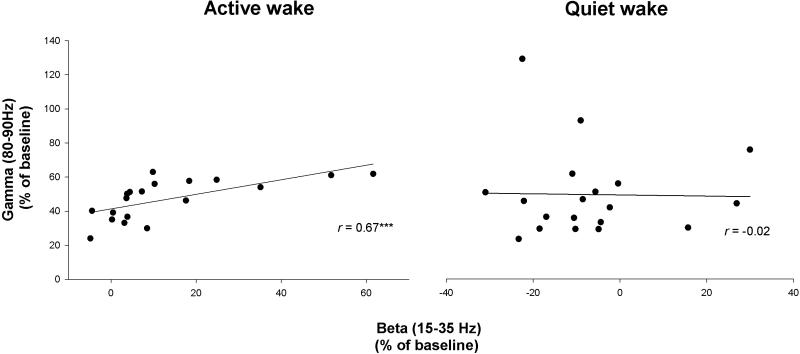

Co-occurrence of beta oscillations with other frequency ranges is distinct in AW and QW

That beta activity reflects fundamentally different processes in AW and QW was further demonstrated by linear regression analyses (Table 1, left panel). In AW during sensory activation, beta activity exhibited a strong positive correlation with gamma activity in both leads (r>0.67, p<0.001; Fig 5A) and no significant correlation with SWA. The association between beta and gamma activity was not significant in QW (r's<0.29, p>0.21, Fig.5B). Beta and gamma activity thus occur coordinately only in the state of AW.

Figure 5.

Scatter plot of the correlation between frontal beta (15-35Hz) and gamma (80-90Hz) activity in active and quiet wake during sensory stimulation, n=20.

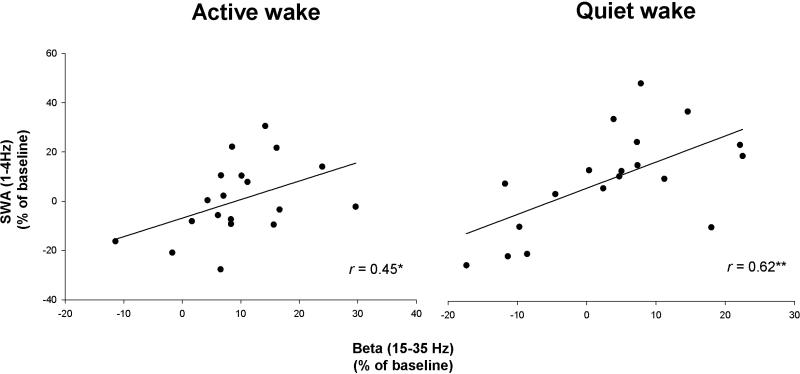

Our hypothesis of an association between beta activity and sleep drive in QW was tested using the EEG dynamics during sessions of recovery. Again, a clear distinction between AW and QW in the interrelationships of SWA, beta and gamma network oscillations was present (Table 1, right panel). Beta activity exhibited a significant positive correlation with the increase in SWA, in QW (r=0.62, p=0.004) and in AW (r=0.45, p=0.046). See Fig.6. This demonstrates that beta activity, like SWA, tracks sleep need. Gamma activity exhibited a significant inverse relationship with SWA in both leads (r<−0.4, p<0.05) during QW. Beta activity showed a strong trend similar to SWA, with an inverse relationship to gamma activity in QW (r=−0.41, p=0.072).

Figure 6.

Scatter plot of the correlation between the increase in frontal beta activity (15-35Hz) and the increase in SWA (1-4Hz) in active and quiet wake during recovery from sensory activation, n=20.

Beta oscillation is an electrophysiological marker of metabolic downregulation in QW

We asked whether changes in cerebral lactate concentration vary as a function of waking sub-state. In agreement with prior literature, lactate concentration increased during REMS and decreased during SWS (Fig.7A,C). Lactate concentration decreased in QW, similar to SWS. In contrast, lactate concentration increased in AW, similar to REMS (Fig.7B,C). To assure that the metabolic down state during QW was not a consequence of transition into SWS, we tested if the lactate dynamics in QW-to-SWS and QW-to-AW transitions was differently expressed. During the 1-min segment of QW prior to either AW or SWS, the lactate concentration remained stable (F(5,85)=1.82, p=0.43, Fig.8).

Our findings prompted us to test if predominance of beta activity could serve as an EEG marker for distinct metabolic dynamics in AW and QW. Indeed, high amounts of beta activity accelerated the increase in lactate concentration in AW relative to AW characterized by a paucity of beta activity (F(11,176)=2.5, p=0.006). In direct contrast, QW epochs containing high amounts of beta activity exhibited a steeper decline in lactate concentration than those characterized by a paucity of beta activity (F(11,176)=1.9, p=0.041). Lactate concentration only declined when beta activity predominated in QW. The net change of lactate was neutral in QW characterized by a paucity of beta activity. Predominance of beta oscillations thus serves as a QW-specific electrophysiological marker of a metabolic down state during wakefulness. Data is illustrated in Fig. 3, supporting information.

State dependent dynamics of lactate concentration differ across QW and AW

A 3-state homeostatic model (wake vs. SWS vs REMS) was modified to include AW and QW to test for a better prediction of the dynamics of lactate concentration across sleep and wake states. It was assumed that lactate concentration increased during desynchronized states (AW, W and REMS) and decreased across synchronized state (QW and SWS). The 5-state homeostatic model yielded a significant reduction in the residuals relative to the 3-state model and provided a better fit to the data for nearly every recording (Fig.9). These data demonstrate that lactate concentration dynamics behave differently in QW and AW.

DISCUSSION

Beta (15-35Hz) oscillations represent fundamentally different processes in QW and AW, both during sensory activation and during recovery in mice. In the state of AW, sessions of vibrissal sensory stimulation elevated beta activity consistently and gamma (80-90Hz) activity transiently in the somatosensory cortex, a region receiving sensory inputs via thalamocortical axons. In the frontal cortex, sensory stimulation (independently of the type of stimulation: WHISK or GH) elevated beta and gamma activity. The increase in beta and gamma oscillations during active wake was found to correlate in both cortex regions. In mammals, gamma activity is hypothesized to support multiple cognitive processes (e.g. selective attention, visual processing, memory, learning and response timing; reviewed in Bosman et al. 2014) and beta activity is similarly found to be elevated during sensory and information processing (Bouyer et al. 1981, Basar-Eroglu et al. 1996). Hence, the parallel changes of beta and gamma activity suggest that these oscillations track the processing of sensory information during AW.

By contrast, beta and gamma activity exhibited opposing dynamics when the mice were in the state of QW. In QW during continuous sensory activation, beta activity was reduced in both cortex regions, and the correlation with gamma activity was lost. This uncoupling from gamma activity in the behavioral state of QW was also visible in the absence of active sensory input. Wake EEG synchronization at low frequencies (<10Hz) has been shown to increase in proportion to time spent awake in rats (restricted to ‘low EMG’) and humans (subjects being in QW during the EEG monitoring), and is consequently interpreted as an electrophysiological marker of sleep need (Aeschbach et al. 1997, Borbely and Achermann 2004, Vyazovskiy and Tobler 2005). The present data show that this relationship also holds in a higher frequency range, as beta activity was coupled with SWA in tracking the sleep homeostatic drive. This commonality between beta and SWA was apparent only during QW and only when sensory activation was withdrawn (‘recovery sessions’). Notably, vibrissal sensory activation obscures sleep drive-dependent beta activity. The current novel finding of beta oscillations as a correlate to sleep drive in mice urge further studies to clarify whether beta oscillations exhibit similar state-dependence across species.

In humans, uncoupling of beta (abnormally high) from gamma (reduced) activity is observed in insomnia patients (Freedman 1986, Perlis et al. 2001, Perlis et al. 2001, Strijkstra et al. 2003) at bed time. Elevated beta activity before sleep onset has been interpreted as evidence of central nervous system hyperarousal (Perlis et al. 2001, Perlis et al. 2001). Still, an association between beta EEG and subjective sleepiness has been reported but discussed as counter-intuitive (Strijkstra et al. 2003). The current analysis demonstrates that the elevation of beta, if not accompanied by elevation of gamma activity and gross motor arousal, is a marker for sleep need. Thus, efforts to suppress beta activity (for instance, via biofeedback at bed time) to reduce information processing and facilitate sleep, may be counter-indicated in insomnia patients.

Accumulation of the sleep homeostatic drive is shown to be both time- and use dependent (Vyazovskiy et al. 2000, Borbely and Achermann 2004, Huber et al. 2004). The progressive increase in SWA, theta and beta activity is consistent with time-dependent sleep homeostasis (Borbely and Achermann 2004). However, neither SWA, theta nor beta activity differed between WHISK and GH (whisker cut) during the recovery sleep or in QW. In line with this, WHISK mice did not show higher lactate concentration than GH. Both findings are in contrast to the elevated gamma and beta activity in somatosensory cortex during active wake. Our data may reflect a species-specific phenomenon, or a more precise measurement may reveal a use-dependent change in SWA, beta and lactate in the mice somatosensory cortex.

Metabolic demand displayed a clear dichotomy in QW vs AW: lactate concentration (a readout of glucose utilization via glycolysis) declined in QW (similar to SWS) and increased in AW (similar to active sleep; REMS). Moreover, lactate concentration in QW was not distinct in the transition to SWS or transition to AW, indicating that metabolic demand measured is not a consequence of sleep onset. Moreover, beta activity was found to be a modulator of the metabolic demand. The positive association of beta activity with lactate concentration across AW intervals may be due to sensory information processing, as high frequency firing typical of information processing is metabolically demanding (Kann et al. 2014). On the other hand, when the beta activity is inversely proportionate to gamma activity, in QW, the resulting reduction in metabolic demand would be expected to reduce lactate production. However, it is not possible to attribute lactate dynamics to specific neuronal activities: lactate concentration is an integrative measure, reflecting both changes in synthesis and clearance, and is impacted by events 30-60 seconds prior to measurement (Wisor et al. 2012).

Our data augment a growing literature demonstrating gradations in cortical function during wakefulness (e.g. Crochet and Petersen 2006, Reimer et al. 2014). Neuronal oscillations are modulators of both output spike timing and synaptic inputs, and produce temporal windows for communication (Fries 2005). The communication windows (for effective interaction) are open at the same times only in coherently oscillating neuronal groups. We hypothesize that in sensorimotor circuits, the mid-range beta oscillations represent distinct network interactions in AW vs QW. Beta coupled with gamma activity during AW is likely a manifestation of information processing. The coupling of beta and SWA during QW as a function of time spent awake could represent either a compensatory process, whereby communication among neurons is facilitated to counteract increasing sleep drive, or a state of synchronization that facilitates initiation of sleep and slow waves.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Research supported by National Institutes of Health grants RO3NS082973 and RO1NS078498.

Footnotes

Author contribution

JW and WC designed the study. WC, MS, JW and MR conducted experiments. All authors analysed the results and wrote the paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- Aeschbach D, Matthews JR, Postolache TT, et al. Dynamics of the human EEG during prolonged wakefulness: evidence for frequency-specific circadian and homeostatic influences. Neurosci Lett. 1997;239:121–124. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00904-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arenkiel BR, Peca J, Davison IG, et al. In vivo light-induced activation of neural circuitry in transgenic mice expressing channelrhodopsin-2. Neuron. 2007;54:205–218. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basar-Eroglu C, Struber D, Schurmann M, Stadler M, Basar E. Gamma-band responses in the brain: a short review of psychophysiological correlates and functional significance. Int J Psychophysiol. 1996;24:101–112. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8760(96)00051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borbely AA. A two process model of sleep regulation. Hum Neurobiol. 1982;1:195–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borbely AA, Achermann P. Sleep homeostasis and models of sleep regulation. In: Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, editors. Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. W.B. Saunders; Philadelphia: 2004. pp. 377–390. [Google Scholar]

- Bosman CA, Lansink CS, Pennartz CM. Functions of gamma-band synchronization in cognition: from single circuits to functional diversity across cortical and subcortical systems. Eur J Neurosci. 2014;39:1982–1999. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouyer JJ, Montaron MF, Rougeul A. Fast fronto-parietal rhythms during combined focused attentive behaviour and immobility in cat: cortical and thalamic localizations. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1981;51:244–252. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(81)90138-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsaki G, Draguhn A. Neuronal oscillations in cortical networks. Science. 2004;304:1926–1929. doi: 10.1126/science.1099745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clegern WC, Moore ME, Schmidt MA, Wisor J. Simultaneous electroencephalography, real-time measurement of lactate concentration and optogenetic manipulation of neuronal activity in the rodent cerebral cortex. J Vis Exp. 2012:e4328. doi: 10.3791/4328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crochet S, Petersen CC. Correlating whisker behavior with membrane potential in barrel cortex of awake mice. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:608–610. doi: 10.1038/nn1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman RR. EEG power spectra in sleep-onset insomnia. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1986;63:408–413. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(86)90122-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fries P. A mechanism for cognitive dynamics: neuronal communication through neuronal coherence. Trends Cogn Sci. 2005;9:474–480. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber R, Ghilardi MF, Massimini M, Tononi G. Local sleep and learning. Nature. 2004;430:78–81. doi: 10.1038/nature02663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann O, Papageorgiou IE, Draguhn A. Highly energized inhibitory interneurons are a central element for information processing in cortical networks. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34:1270–1282. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelder JA, Mead R. A Simplex Method for Function Minimization. The Computer Journal. 1965;7:308–313. [Google Scholar]

- Niell CM, Stryker MP. Modulation of visual responses by behavioral state in mouse visual cortex. Neuron. 2010;65:472–479. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlis ML, Merica H, Smith MT, Giles DE. Beta EEG activity and insomnia. Sleep Med Rev. 2001;5:363–374. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2001.0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlis ML, Smith MT, Andrews PJ, Orff H, Giles DE. Beta/Gamma EEG activity in patients with primary and secondary insomnia and good sleeper controls. Sleep. 2001;24:110–117. doi: 10.1093/sleep/24.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimer J, Froudarakis E, Cadwell CR, et al. Pupil fluctuations track fast switching of cortical states during quiet wakefulness. Neuron. 2014;84:355–362. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rempe MJ, Wisor JP. Cerebral lactate dynamics across sleep/wake cycles. Front Comput Neurosci. 2014;8:174. doi: 10.3389/fncom.2014.00174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steriade M, Contreras D, Curro Dossi R, Nunez A. The slow (< 1 Hz) oscillation in reticular thalamic and thalamocortical neurons: scenario of sleep rhythm generation in interacting thalamic and neocortical networks. J Neurosci. 1993;13:3284–3299. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-08-03284.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strijkstra AM, Beersma DG, Drayer B, Halbesma N, Daan S. Subjective sleepiness correlates negatively with global alpha (8-12 Hz) and positively with central frontal theta (4-8 Hz) frequencies in the human resting awake electroencephalogram. Neurosci Lett. 2003;340:17–20. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyazovskiy V, Borbely AA, Tobler I. Unilateral vibrissae stimulation during waking induces interhemispheric EEG asymmetry during subsequent sleep in the rat. J Sleep Res. 2000;9:367–371. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2000.00230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyazovskiy VV, Tobler I. Theta activity in the waking EEG is a marker of sleep propensity in the rat. Brain Res. 2005;1050:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisor JP, Rempe MJ, Schmidt MA, Moore ME, Clegern WC. Sleep slow-wave activity regulates cerebral glycolytic metabolism. Cereb Cortex. 2012;23:1978–1987. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisor JP, Rempe MJ, Schmidt MA, Moore ME, Clegern WC. Sleep slow-wave activity regulates cerebral glycolytic metabolism. Cereb Cortex. 2013;23:1978–1987. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.