Abstract

Several proteins endogenously produced during the process of intestinal wound healing have demonstrated prorestitutive properties. The presence of serum amyloid A1 (SAA1), an acute-phase reactant, within inflamed tissues, where it exerts chemotaxis of phagocytes, is well recognized; however, a putative role in intestinal wound repair has not been described. Herein, we show that SAA1 induces intestinal epithelial cell migration, spreading, and attachment through a formyl peptide receptor 2–dependent mechanism. Induction of the prorestitutive phenotype is concentration and time dependent and is associated with epithelial reactive oxygen species production and alterations in p130 Crk-associated substrate staining. In addition, using a murine model of wound recovery, we provide evidence that SAA1 is dynamically and temporally regulated, and that the elaboration of SAA1 within the wound microenvironment correlates with the influx of SAA1/CD11b coexpressing immune cells and increases in cytokines known to induce SAA expression. Overall, the present work demonstrates an important role for SAA in epithelial wound recovery and provides evidence for a physiological role in the wound environment.

Intestinal epithelial cells lining the alimentary tract mucosa play a key role in forming a barrier that prevents resident immune cells and the systemic circulation from direct exposure to commensal microorganisms and luminal antigens. This epithelial barrier, however, becomes disrupted in several pathologic and clinical conditions. Infectious agents, such as Clostridium difficile, inflammatory diseases, including ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease, and traumatic insults all lead to barrier disruption and local inflammation with the potential for systemic infection. These epithelial defects, encompassing ulcerations and erosions, are resealed through a process known as restitution, in which epithelial cells adjacent to wounds migrate over exposed denuded tissue.1 Occurring within minutes to hours, the process of restitution is followed by proliferation of epithelial cells to replace those lost to injury.

Although the molecular events involved in epithelial restitution are complex and incompletely understood, several proteins endogenously produced during wound healing have demonstrated prorestitutive properties. One such protein, annexin A1, activates formyl peptide receptor 1 (FPR1), a member of a class of G-protein–coupled pattern recognition receptors expressed on colonic epithelium.2 When activated, FPR1 leads to low-level, physiological, intracellular generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by epithelial NADPH-oxidase 1, inhibition of specific regulatory phosphatases, and subsequent increases in epithelial migration. Formyl peptide receptor 2 (FPR2) is the second member of the formyl peptide receptor group, and its tissue expression patterns are similar to those of FPR1. One endogenously produced ligand for FPR2 is an acute-phase reactant, serum amyloid A1 (SAA1), that is released during an inflammatory or tissue injury response.3 However, the contribution of SAA1 in activation of FPR–NADPH-oxidase 1 signaling to influence intestinal mucosal wound repair has not been defined.

SAA1 is a small (11.7-kDa) secreted protein first characterized for its role in the acute-phase response to inflammation, tissue trauma, and infection.4 During the acute-phase response, serum SAA1 levels may increase >1000-fold as a result of cytokine-induced synthesis [tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-1, and IL-6, among others] and secretion by hepatocytes.5 Although the liver has traditionally been recognized as the predominant site of SAA1 production, additional sites of extrahepatic expression include epithelial cells lining the mucosa of the gastrointestinal tract and immune cell populations.6, 7, 8, 9 In humans, three SAA genes, SAA1, SAA2, and SAA4, are expressed, with SAA3 considered to be a nonexpressed pseudogene. SAA1 and SAA2 protein products are the predominant circulating forms present during the acute-phase response, whereas SAA4 is constitutively expressed and its protein product is a normal component of circulating non–acute-phase high-density lipoprotein. In mice, all four SAA genes are expressed in the liver, with extrahepatic sites showing variable expression of SAA1, SAA2, and SAA3.9, 10

Expression of SAA in cell types outside of the liver raises the possibility that localized tissue damage and inflammation may result in induced SAA expression that is limited to the site of injury. Accordingly, SAA levels have been shown to be elevated at localized sites of inflammation, such as in synovial fluid of rheumatoid arthritis patients.11 In this context, production of SAA from injured synovium has been shown to promote migration of inflammatory cells as well as synovial and endothelial cells.12, 13 Intestinal ulceration has been observed in inflammatory diseases, including chronic active inflammatory bowel disease, and represents an additional example of localized tissue damage and inflammation. In this context, the role of SAA in orchestrating mucosal repair has not been explored.

Herein, we present evidence that SAA1 promotes intestinal epithelial cell migration that is mediated by FPR2 signaling with generation of ROS and changes in the localization of p130 Crk-associated substrate (CAS) in focal cell-matrix associations. Additional studies demonstrate SAA1 regulates cell attachment to specific components of the extracellular matrix and shows an ability to promote FPR2-dependent cell spreading. Furthermore, we show that murine SAA1 is released into the colonic wound environment in a time-dependent manner, where its levels correlate with the influx of SAA1/CD11b coexpressing immune cells and increases in known SAA1 expression-inducing cytokines. These findings provide novel insight on mechanisms by which an inflammatory acute-phase reactant protein serves to promote mucosal wound closure in intestinal epithelial cells.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

SK-CO15 and Caco-2 model human intestinal epithelial cells were used and grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Cellgro, Manassas, VA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 2 mmol/L l-glutamine, 100 IU of penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 15 mmol/L HEPES, and 1% nonessential amino acids (Cellgro). Cells were harvested with 0.05% trypsin in Hanks' balanced salt solution.

Antibodies and Reagents

Recombinant SAA1 was purchased from Prospec (Ness-Ziona, Israel) and reconstituted in cell culture grade water; its 104 amino acids are identical to the residues (19 to 122) making up human SAA1 after signal peptide cleavage.14 WRW4 was purchased from Tocris (Bristol, UK; inhibitory concentration of 50% = 0.23 μmol/L for inhibiting effects of FPR2 agonist WYKMVm), with concentrations tested of 2.3, 10.0, and 23.0 μmol/L (results for 23.0 μmol/L shown). Cyclosporine H was obtained from Enzo Life Sciences (Farmingdale, NY) and tested at 1 μmol/L.2, 15 FPS-ZM1 was obtained from Millipore (Billerica, MA), and A 438079 was obtained from Tocris. As the reported inhibitory constant for FPS-ZM1 is 25 nmol/L against the amyloid-related peptide Aß40, concentrations of 0.25 μmol/L (250 nmol/L), 2.5 μmol/L, and 25 μmol/L were tested (results shown for 2.5 μmol/L). Concentrations of 10.0 and 100 μmol/L were tested for A 438079 (inhibitory concentration of 50% = 6.9). Dimethyl sulfoxide was used as vehicle for all inhibitors, except for WRW4, which was dissolved in 25% ethanol/H2O. ROSstar 550 was purchased from LI-COR (Lincoln, NE). Goat polyclonal antibody raised against mouse SAA1 was obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN); this antibody also reportedly cross-reacts with SAA2 in direct enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) and Western blots. Rat anti-mouse CD11b was obtained from eBiosciences (San Diego, CA). Rabbit phosphorylated specific antibodies to p130 CAS Y410, PAX Y118, Src Y416, and total Src were obtained from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). Rat monoclonal antibody against E-cadherin was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Mouse antibody against total CAS was obtained from BD Transduction (San Jose, CA). Alexa Fluor 488– and 647–conjugated secondary antibodies and phalloidin stain used for immunofluorescence experiments were obtained from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR).

Scratch Wound Assay

Tissue culture 24-well plates were seeded at densities of 5 × 105/mL to provide monolayers the following day. After aspirating media, epithelial monolayers were scratched once using a plastic micropipette tip attached to a 2-mL glass cell culture aspirator under gentle vacuum. Cells were treated with various concentrations of SAA (0.1, 1.0, and 10 μmol/L)/inhibitor/vehicle dissolved in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium and incubated at 37°C for 6, 12, and 18 hours. Images, both at time of treatment and end point, were taken of the epithelial front relative to a line drawn on the backs of wells, and the difference in area was determined using ImageJ software version 1.51p (NIH, Bethesda, MD; http://imagej.nih.gov/ij). Accurate relocation of the initial image site was informed from calibrating the apex of the convexity of the individual wells to the apex of the convexity of the field of view. Area covered was determined at four sites (two from each wound front) per well, and average change in area covered was determined. For immunofluorescence staining of focal adhesion proteins, cells were seeded onto coverslips in 24-well plates, scratched, and then incubated with SAA (1.0 μmol/L)/vehicle for 1 hour. Coverslips were fixed with fresh 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100. Coverslips were then incubated with phosphorylated specific primary antibodies to p130 CAS Y410, PAX Y118, or Src Y416, diluted 1:250 for 2 hours at room temperature. Next, species-specific secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 and anti-goat Alex Fluor 647 antibodies, each diluted 1:1000, along with phalloidin Alexa Fluor 555 conjugate at 1:1000, were applied at room temperature for an additional 1 hour. After several phosphate-buffered saline washes, coverslips were mounted with Prolong (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and visualized by fluorescence microscopy (Olympus FV1000 confocal microscope; Olympus, Pittsburgh, PA). Lamellipodia with peripheral phosphorylated p130 CAS staining were counted along both sides of the scratch wounds (expressed per 40 high-power fields). Staining experiments were performed three times, with n = 3 each.

Cell Spreading

Twenty-four–well plates containing glass coverslips were seeded at densities of 5 × 104/mL to provide dispersed cell clusters with room to spread during the treatment period. SAA (1.0 μmol/L)/WRW4 (23.0 μmol/L)/vehicle was added to cells suspended in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium before plating. After 18 hours, coverslips were fixed and permeabilized with 100% ice-cold ethanol at −20°C for 20 minutes and then stained as described above (Scratch Wound Assay). Cells were successively immunolabeled with anti–E-cadherin (1:250) and then secondary antibody (anti-rat Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate at 1:1000) to delineate the outer membranes of cells. Quantitative digital area measurements (ImageJ) were obtained on five representative micrographs from each well. Average cell diameter in representative cell clusters was calculated by determining the average diameter of 10 randomly selected cells, with four separate diameter measurements performed per cell (to prevent bias). The assay was performed in triplicate, each n = 3.

Cell Adhesion Assay

Tissue culture 96-well flat-bottom plates were coated with collagen I, collagen IV, or fibronectin at 25 μg/mL overnight at 4°C and then blocked in 2% bovine serum albumin/phosphate-buffered saline for 1 hour. Cells were first washed in phosphate-buffered saline, then incubated with calcium-free medium for 20 minutes to disrupt cells. The cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and briefly treated with trypsin/EDTA to detach cells. Cells were then washed, centrifuged, and resuspended in Hanks' balanced salt solution supplemented with 0.2% bovine serum albumin. Cells were added at 5 × 104/96-well plate and incubated for 45 minutes with 1.0 μmol/L SAA or vehicle control at 37°C. Cells were washed five times in Hanks' balanced salt solution and then fixed with ethanol and stained with crystal violet. Cell adhesion was assessed using a microplate reader with absorbance at A570. The experiment was performed in duplicate, each experiment with n = 3.

ROS Production

Tissue culture 24-well plates containing glass coverslips were seeded and scratched as described above (Scratch Wound Assay). Cells were washed and incubated with ROSstar 550 for 30 minutes at 37°C. Cells were then washed three times, and SAA (1.0 μmol/L)/vehicle dissolved in serum-free media was added and incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes. Cells were briefly washed, and 70% glycerol was applied to a glass slide to which the coverslip was added. ROS production was visualized by fluorescence microscopy (Olympus FV1000 confocal microscope). Three micrographs per well were obtained for subsequent relative fluorescent intensity measurements using ImageJ. The experiment was performed three times, each n = 2.

Ex Vivo Intestinal Wound Culture

Bl6 mice, aged 8 to 10 weeks, were anesthetized using appropriate xylazine/ketamine dosing, and colonic wounds were generated using a veterinary endoscope and 2-mm biopsy forceps. On days 1, 2, 4, and 6 after biopsy, mice were euthanized and wounds were excised so as to only include the wound bed and minimal adjacent mucosa. Mucosa within approximately 1 cm of each wound was obtained as control nonwounded tissue. Tissue was incubated for 5 hours at 37°C in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, after which supernatant was obtained and assayed by both SAA ELISA (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) and V-PLEX Proinflammatory Panel 1 (interferon-γ, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, KC/GRO (CXCL1), IL-10, IL-12p70, and TNF-α) mouse kit sandwich immunoassay (Meso Scale Diagnostics, Rockville, MD) (day 2 wounds assayed only), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

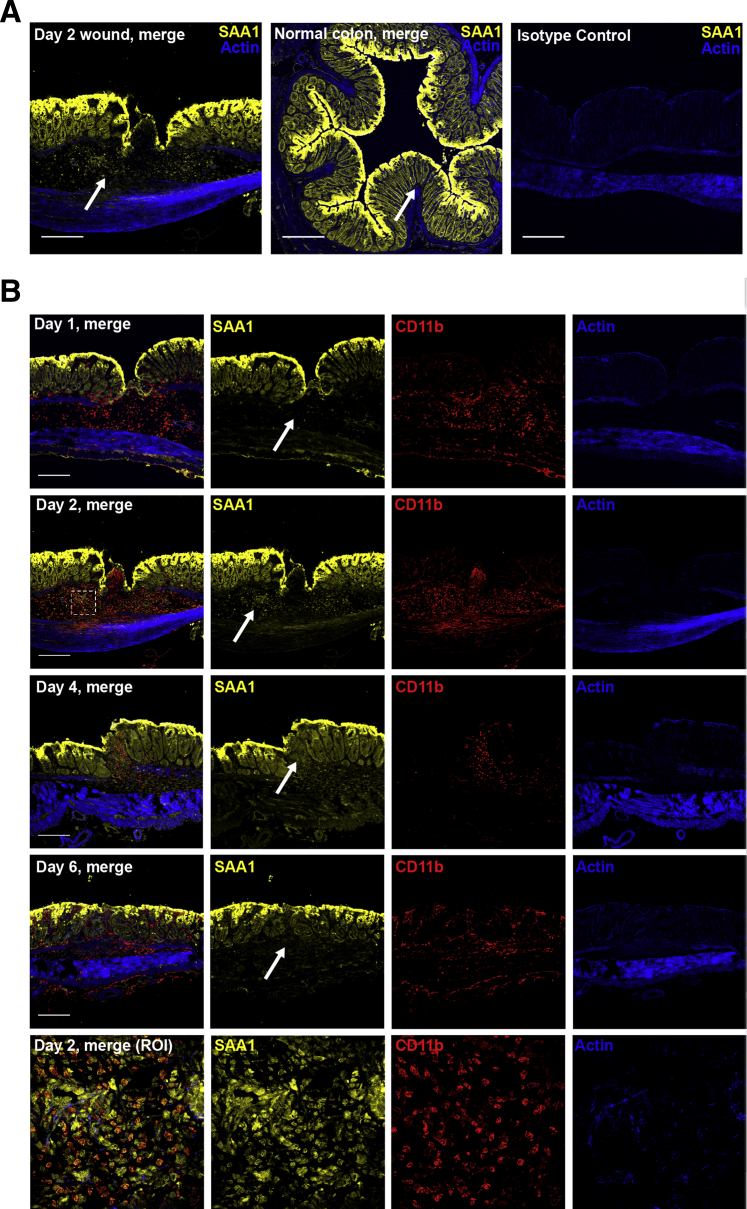

Immunofluorescence Staining of Wound Beds

Bioptic colonic wounds on days 1, 2, 4, and 6 after biopsy were excised, oriented, and embedded in OCT. Tissue sections were fixed with fresh 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100. Primary antibody (rabbit anti-SAA1, 1:100; rat anti-CD11b, 1:250) was incubated for 2 hours at room temperature, followed by the appropriate incubation with species-specific secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 and 647, each diluted 1:1000, along with phalloidin Alexa Fluor 555 conjugate, diluted at 1:1000. Images show representative findings from multiple biopsies (two to three per mouse) obtained from four mice in each time point.

Western Blots

Cell lysates were prepared by scraping cells into SDS-sample buffer containing dithiothreitol, along with protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails, and then sonicated for 10 seconds, before adding heat-denaturing proteins at 100°C for 2 minutes. SDS-PAGE and immunoblots were performed by standard methods using approximately 20 μg of total protein per lane. Primary antibodies were diluted 1:2000 and incubated with membranes overnight at 4°C. Either anti-mouse or rabbit secondary horseradish peroxidase–conjugated antibodies (diluted 1:10,000, incubated for 1 hour at room temperature) were used with standard electrochemiluminescence detection/development protocols to reveal protein/phosphorylation levels.

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as means ± SEM for each treatment group. Statistical significance was evaluated using two-tailed t-test and one-way analysis of variance with Tukey's multiple comparison test (GraphPad Prism version 6.0; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

SAA1 Promotes Intestinal Epithelial Cell Migration

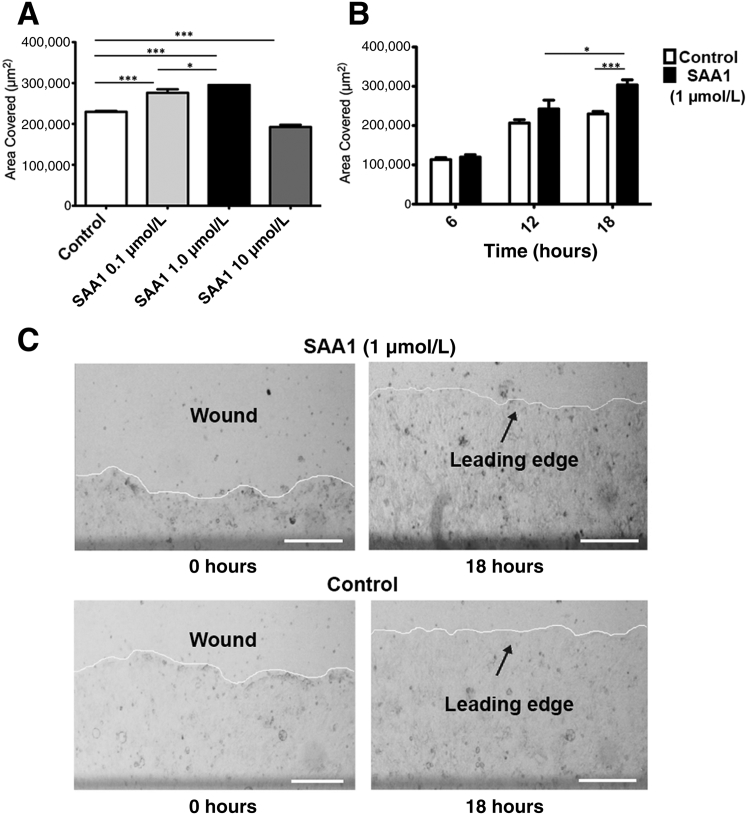

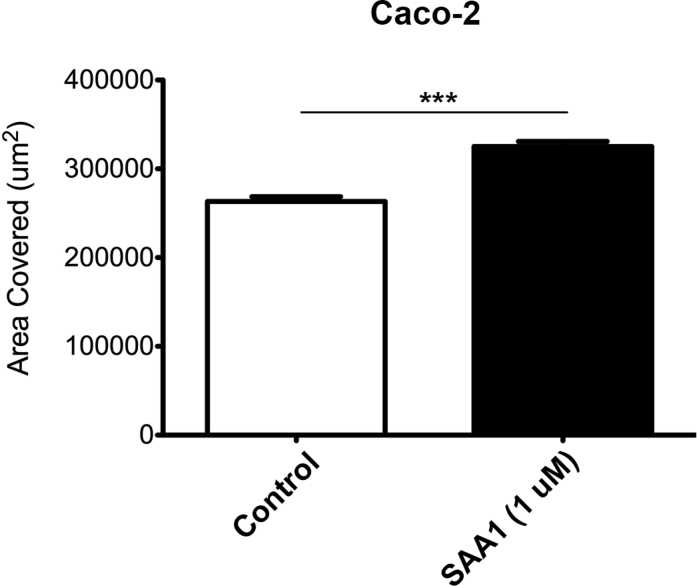

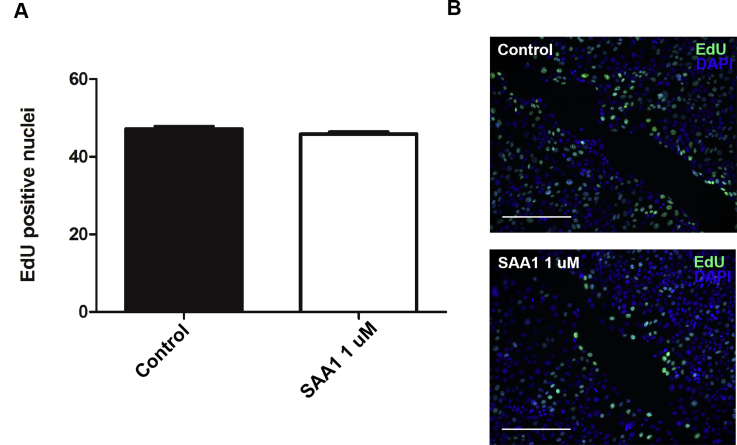

SAA1 is released in the acute phase of inflammation and has been proposed as a chemotactic agent for phagocytic cells as well as synovial and endothelial cells. Whether SAA1 can induce migration in epithelial cells, however, is an open question. To determine the role of SAA1 in intestinal mucosal wound closure, an in vitro scratch wound healing assay using the model intestinal epithelial cell line, SKCO-15, was used.16 Recombinant SAA1 incubation enhanced epithelial cell migration at scratch wound edges, with a peak response at 1.0 μmol/L SAA1 (Figure 1, A and C). In addition, time course studies revealed maximal increase in wound repair 18 hours after SAA1 treatment (Figure 1B). Although significant increases in cell migration were observed between SAA1 concentrations of 0.1 and 1.0 μmol/L, cells treated with 10 μmol/L SAA1 showed inhibited migration. Because collective epithelial migration mediates wound closure, wound closure in response to SAA1 was visualized using real-time video imaging of healing scratch wounds. Recordings at low magnification (×5) (Supplemental Videos S1, S2, and S3) confirmed increased collective migration of the epithelium in response to SAA1 treatment. Higher-power magnification recordings further confirmed SAA1-induced migration of epithelium (Supplemental Videos S4, S5, and S6). To ensure SAA1-induced migration was not cell line specific, wound closure was analyzed using another model intestinal epithelial cell line, Caco-2, that yielded similar results (Supplemental Figure S1). In addition to migration, cell proliferation also contributes to wound repair. However, SAA1 treatment did not influence epithelial proliferation, as determined by nuclear thymidine analog 5-ethyl-2ʹ-deoxyuridine incorporation (Supplemental Figure S2).

Figure 1.

SAA1 promotes epithelial wound closure. A: SAA1 significantly induces cell migration at concentrations of both 0.1 and 1.0 μmol/L, with maximal stimulation at 1.0 μmol/L. Cells show reduced migration at 10 μmol/L. B: SAA1-induced cell migration is time dependent, showing advanced wound closure at 18 hours after wounding (1 μmol/L SAA1; t-test). C: Representative photomicrographs of SAA1 (1 μmol/L) induced epithelial migration (white line denotes advancing cell front). All experiments were performed in triplicate. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (A and B). n ≥ 3 (A–C). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 (one-way analysis of variance, with Tukey's multiple comparison test). Scale bars = 250 μm (C).

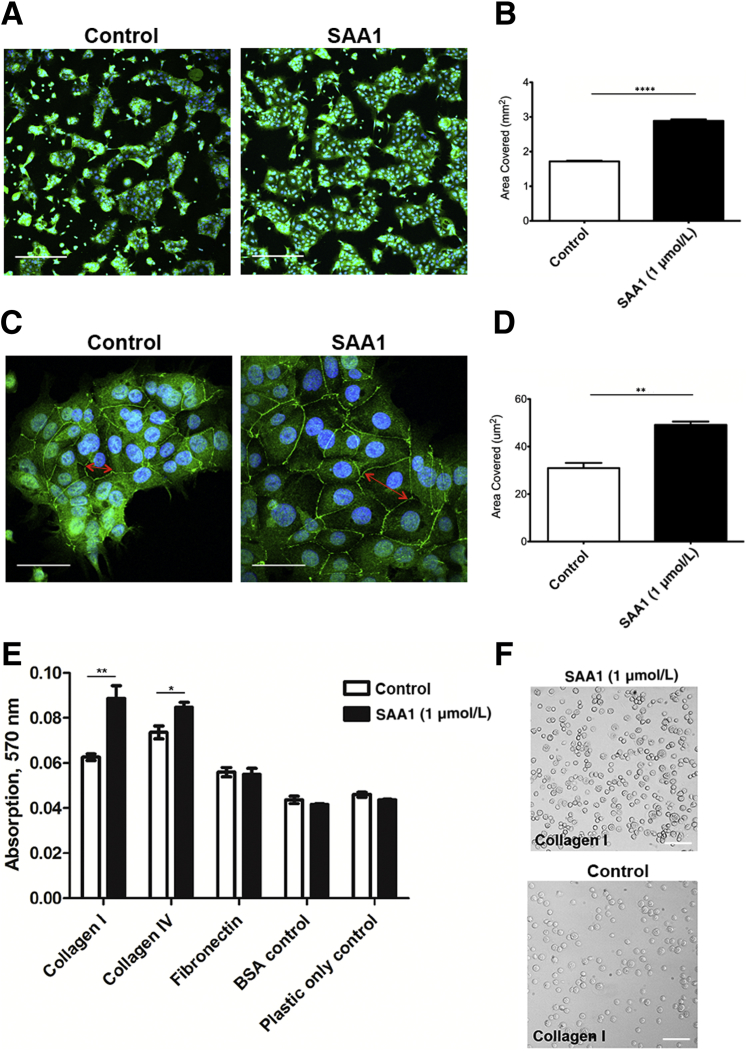

SAA1 Promotes Cell Spreading and Adhesion

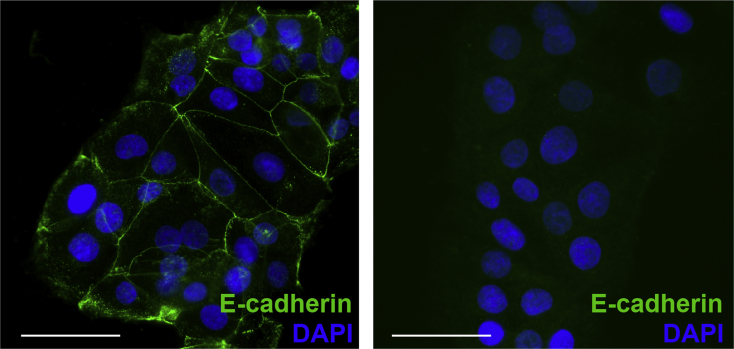

Cell spreading contributes to the forward movement of epithelial cells during wound closure. Because SAA1 promotes epithelial cell migration, the ability of SAA1 to promote epithelial cell spreading was evaluated. Subconfluent culture of cells was incubated with SAA1 overnight (18 hours), during which cells were allowed to spread. Epithelial cell colonies exposed to SAA1 covered significantly greater surface area than with vehicle alone (Figure 2, A and B). High-power magnification images show cells treated with SAA1 demonstrate greater degrees of spreading, as measured by multiple different averaged cell diameter measurements (Figure 2, C and D). Staining for E-cadherin was used to label the junction of cells and to highlight cellular borders (isotype control) (Supplemental Figure S3).

Figure 2.

SAA1 induces epithelial cell spreading and increases epithelial cell attachment. A: Representative low-power photomicrographs of SAA1-induced epithelial spreading (1 μmol/L, 18 hours). Immunofluorescence staining for E-cadherin (green) highlights cytoplasmic borders; nuclei are blue (DAPI). B: Summarized data for epithelial spreading is presented in the graph. C: Representative high-power images of SAA1 (1 μmol/L) treated cells with increased cell diameter. Red arrows show example of one cell diameter measurement, with four total measurements performed for each cell. D: Graph with summarized cell diameter measurements. Results summarize data from three experiments. Statistical significance was determined by t-test. E: Cells exposed to SAA1 (1 μmol/L) for 45 minutes show significantly increased rates of attachment to both collagen I– and collagen IV–coated wells. Assay was performed in duplicate. Statistical significance was determined by t-test. F: Representative phase-contrast micrographs demonstrating SAA1-induced increased cell attachment (collagen I shown). Data are expressed as means ± SEM (B, D, and E). n = 3 (D); n = 6 for each treatment group (E). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, and ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001. Scale bars: 100 μm (A); 50 μm (C and F). BSA, bovine serum albumin.

Wound closure is mediated by coordinated collective migration of the epithelial sheet that requires active turnover of cell-matrix adhesions. Thus, to investigate the mechanisms by which SAA1 promotes epithelial movement, the influence of SAA1 on cell-matrix adhesion was analyzed. SK-CO15 cell-matrix adhesion assays were performed using cell culture surfaces that were coated with the extracellular matrix components collagen I, collagen IV, or fibronectin. Forty-five–minute exposure to SAA1 enhanced adhesion of epithelial cells to collagen I and IV compared with control cells [absorption, 570 nm: 0.089 ± 0.006 versus 0.06267 ± 0.001 (P < 0.01); and 0.085 ± 0.002 versus 0.074 ± 0.003 (P < 0.05), respectively] (Figure 2, E and F).

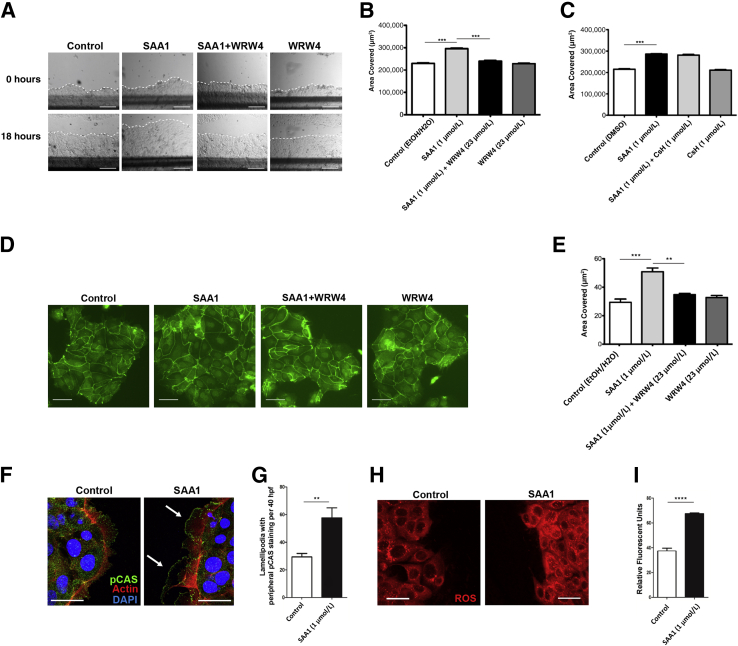

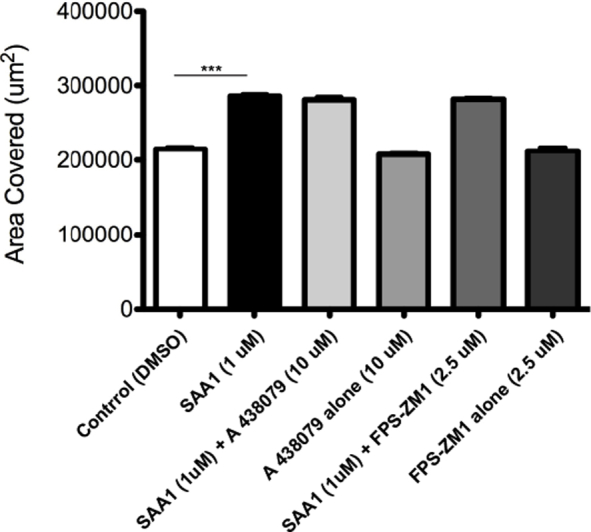

SAA1-Induced Intestinal Epithelial Wound Closure and Cell Spreading Is Mediated by FPR2 Signaling

To determine a mechanism by which SAA1 facilitates wound closure, healing wounds were treated with small-molecule competitive antagonists for receptors with putative roles in SAA1 signaling. Previous studies have demonstrated that SAA1 promotes chemotaxis in neutrophils through FPR2, rather than FPR1, signaling. Therefore, the FPR2-specific receptor antagonist WRW43, 17, 18 and the FPR1 receptor antagonist cyclosporine H15 were used. Cells treated with WRW4 demonstrated markedly reduced wound closure compared with control cells (Figure 3, A and B). The inhibitory effects of WRW4 were further visualized using time-lapse video microscopy, which showed reduced migration in real time (Supplemental Videos S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, and S6). Importantly, cyclosporine H treatment did not significantly reduce SAA1-induced cell migration (Figure 3C). Studies have shown additional receptors, such as nucleotide receptor P2X7 and receptor for advanced glycation end products, are capable of mediating the effects of SAA1 and amyloid-related peptides. However, competitive antagonists for these receptors, A 438079 and FPS-ZM1, respectively,17, 19, 20, 21 also failed to inhibit SAA1-induced cell migration (Supplemental Figure S4).

Figure 3.

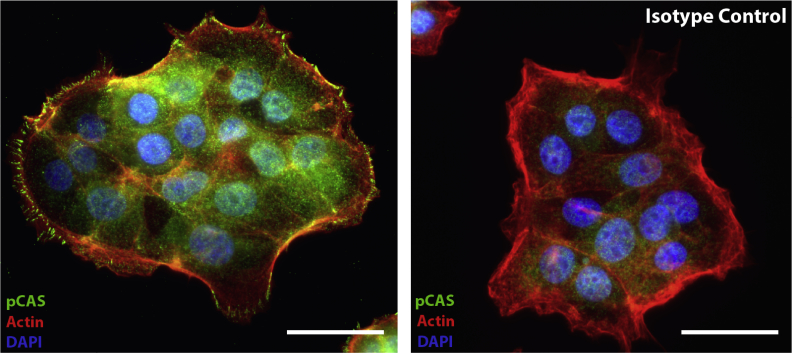

SAA1-induced epithelial cell migration and spreading is FPR2 dependent and involves specific epithelial restitutive signaling events. A: Representative images demonstrating significant inhibition of SAA1 (1 μmol/L) induced migration using the FPR2-specific inhibitor WRW4 (23 μmol/L; 18 hours). Dotted line demarcates leading edge of migrating cells. B: Histogram summarizing WRW4 (23 μmol/L) induced inhibition of SAA1-induced migration. No significant change in migration is observed with WRW4 treatment alone. C: The FPR1-specific inhibitor cyclosporine H (CsH; 1 μmol/L) shows minimal inhibition of SAA-induced migration (significance shown for SAA1 versus control). Experiments were performed in duplicate. Statistical significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance, with Tukey's multiple comparison test. D: Representative photomicrographs of cells treated with SAA1 (1 μmol/L) and WRW4 (23 μmol/L), either alone or in combination (18 hours), show WRW4 inhibits approximately 75% of SAA1-induced cell spreading. Cell cytoplasmic borders highlighted by E-cadherin (green) immunofluorescence staining. E: Summarized cell diameter measurements for effects of WRW4 (23 μmol/L) on SAA1 (1 μmol/L) induced cell spreading is presented in the graph. Results summarize data from two experiments. Statistical significance was determined by t-test. F: At 1 hour after wounding, SAA1 (1 μmol/L) treated cells at the scratch wound edge showed increased cytoplasmic extensions (lamellipodia) with peripheral phosphorylated p130 CAS (pCAS; green) staining compared with control. Arrows indicate two lamellipodia showing peripheral phosphorylated p130 CAS staining. Actin filaments (red) are highlighted by phalloidin, and nuclei (blue) are highlighted by DAPI. G: Histogram displaying increased frequency of lamellipodia with peripheral phosphorylated p130 CAS staining; total number of lamellipodia with peripheral pCAS were counted along both wound edges and expressed per 40 high-power fields (HPFs). H: SAA (1 μmol/L) induced epithelial ROS production at the scratch wound edge with ROSstar 550 fluorescence (red) detected by confocal microscopy (30 minutes). I: Histogram displaying SAA-induced change in relative fluorescence over treatment control. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (B, C, E, G, and I). n = 6 for each treatment group (C); n = 2 (E). ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, and ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001 (t-test). Scale bars: 250 μm (A); 50 μm (D); 25 μm (F and H). DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; EtOH, ethanol.

Given these results, the effects of FPR2 blockade on SAA1-induced epithelial spreading were determined. Samples treated with both SAA1 (1 μmol/L) and WRW4 (23 μmol/L) showed approximately 75% reduction in SAA1-induced increase in cell diameter (Figure 3, D and E). As before, cell diameters were determined from multiple different measurements per cell to prevent bias, and diameters from at least 10 randomly selected cells per cell cluster were obtained. Importantly, cells treated with WRW4 did not show significantly altered spreading compared with control. Taken together, these results indicate a significant role for FPR2 signaling in SAA1-induced cell spreading.

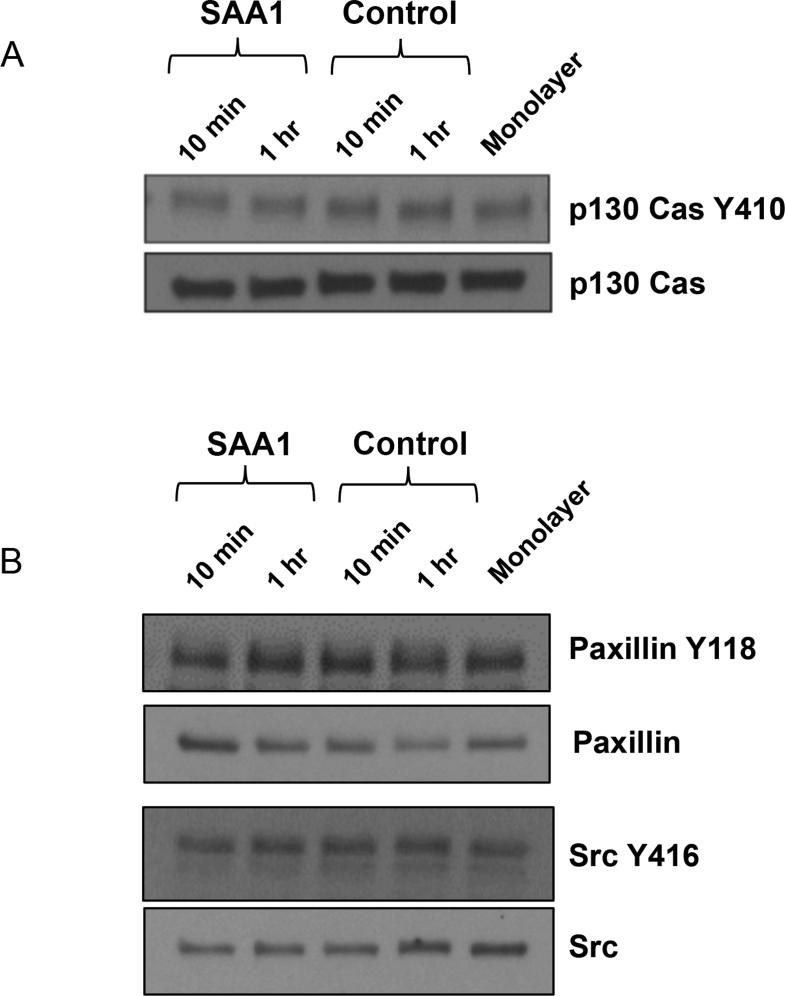

SAA1-Induced Intestinal Epithelial Wound Closure Is Associated with Alterations in p130 CAS Localization and ROS Induction

Focal adhesion protein signaling plays an important role in controlling dynamics of cell-matrix adhesion, which is required for forward cell migration. Thus, localization of focal adhesion proteins was examined in the migrating epithelial cells adjoining the wounds. The focal adhesion protein, p130 CAS, has been previously shown to contribute to forward lamellipodial extension and integrin-mediated cell motility.22 Furthermore, recent work by our group has demonstrated that p130 CAS phosphorylation is reduction-oxidation (redox) dependent and an important event regulating cell migration and spreading.23 Immunofluorescence labeling and confocal microscopy identified an increase in prominence and number of cellular protrusions, or lamellipodia, containing phosphorylated p130 CAS at the leading edge of migrating cells exposed to SAA1 (58 ± 7 versus 30 ± 3; P < 0.01) (Figure 3, F and G, and Supplemental Figure S5). This altered staining pattern is independent of detectable quantitative changes in total cellular phosphorylated p130 CAS, as seen by Western blotting (Supplemental Figure S6A). Additional focal adhesion proteins, including phosphorylated PAX (Y118) and phosphorylated Src (Y416), were also assessed, but did not show significant quantitative differences (Supplemental Figure S6B) or differences in pattern of cellular localization (data not shown).

Prior studies have demonstrated that low-level physiological production of ROS, generated by the intestinal epithelial oxidase NADPH-oxidase 1, influences the phosphorylation status of focal adhesion proteins down-stream of FPR signaling.2 Because FPR signaling influenced SAA1-induced increase in epithelial migration and spreading, the role of redox signaling was examined using ROSstar 550, a redox-sensitive intracellular dye that fluoresces when oxidized. SAA1 exposure increased reactive oxygen species generation (Figure 3, H and I). These findings suggest that, similar to other FPR agonists, production of intracellular ROS may be an important intermediary signaling event mediating SAA1-induced cell migration.

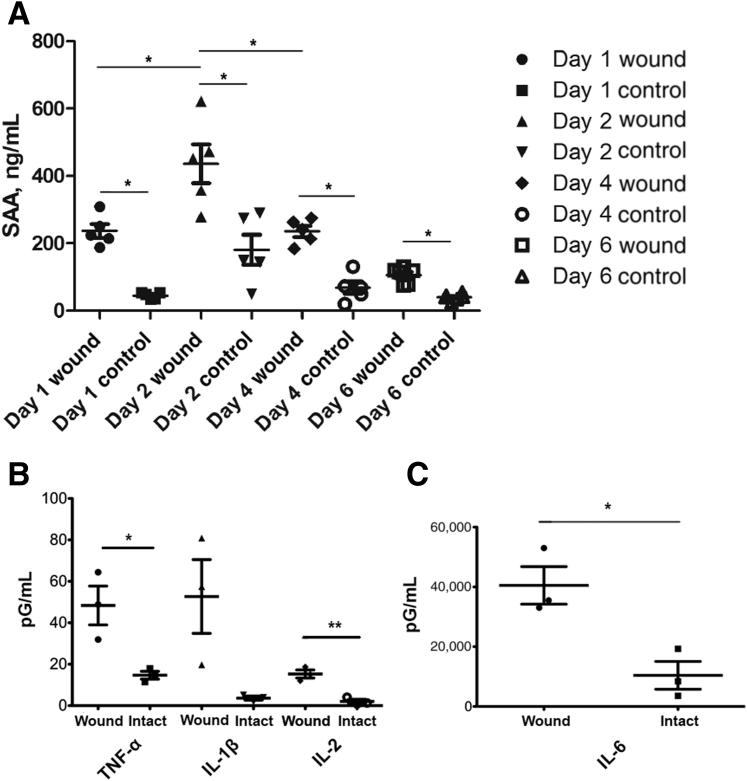

SAA1 Generation in Murine Colonic Mucosa ex Vivo and in Vivo

To further investigate the relevance of the in vitro results, SAA1 generation was analyzed in murine ex vivo healing wounds. Using a well-characterized model of wound healing with a veterinary endoscope to make reproducible mucosal wounds in the colon with biopsy forceps, healing wounds were harvested on days 1 to 6 after biopsy. Wounded and control intact colonic mucosa was cultured ex vivo, and SAA1 generation was analyzed in culture supernatants by ELISA assay. Colonic wounds elaborated significantly greater SAA1 than intact colonic mucosa, with maximally increased SAA1 detected in colonic wounds that were harvested 2 days after biopsy-induced injury (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

SAA1 and cytokine concentrations in ex vivo wound culture supernatants by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). A: Wounded murine colonic tissue demonstrates increased SAA1 elaboration when compared with nonwounded tissue at all days tested, as assessed by ELISA. Supernatants from wounded tissue shows maximal SAA1 concentration at day 2. Wounds and intact tissue were obtained from five mice per time point, with five supernatants assessed per time point. Statistical significance was determined by t-test. B and C: ELISA testing of day 2 wound culture supernatants shows increased levels of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α(B), IL-1β (nonsignificant, P = 0.0514; B), IL-2 (B), and IL-6 (C) compared with nonwounded tissue. n = 3 (B and C). ∗P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 (t-test).

Next, wound bed supernatants were assayed with an inflammatory murine ELISA cytokine panel to determine whether SAA1 elevation is a specific feature of wound healing or rather a general feature of an inflammatory response. Wound bed supernatants demonstrated significantly increased levels of TNF-α, IL-2, and IL-6, and nearly significant levels of IL-1β compared with nonwounded tissue (Figure 4, B and C). Specifically, average levels of TNF-α and IL-6 were increased greater than three times that of intact nonwounded tissue, whereas average IL-1β was substantially elevated, but not significantly. Importantly, prior reports indicate TNF-α and IL-1β show synergistic effects with IL-6 for the induction of SAA expression.24, 25, 26 Overall, these findings indicate that not only is the elevation of SAA1 within wound beds a general feature of an inflammatory response, but in addition shows that elevations of key SAA1 transcriptional inducers may be responsible for elevated levels of SAA1 in the immediate wound environment.

To further correlate the ex vivo results, healing wounds were analyzed for SAA1 protein by immunofluorescence labeling and confocal microscopy. Although SAA1 staining was identified in epithelial cells lining both wounded and nonwounded mucosa, healing wounds also demonstrated SAA1 staining within submucosal inflammatory infiltrates (Figure 5A). Interestingly, patterns of SAA1 expression within these submucosal inflammatory infiltrates changed chronologically (Figure 5B). Although day 1 wounds show histologic correlates of acute inflammation, including submucosal edema and an inflammatory infiltrate composed of neutrophils and macrophages, SAA1 expression is largely absent in the wound bed. However, on day 2, this submucosal infiltrate demonstrates areas of strong SAA1 staining. Subsequent days continue to show SAA1 expression in wound bed infiltrates; however, the degree of SAA1-expressing infiltrating cells within the wound bed becomes progressively less as the wound heals. To confirm that the visualized SAA1 expression in wound beds is present in infiltrating immune cells, tissues were colabeled with CD11b to identify myeloid cells. Colabeling of SAA1 and CD11b was observed in a large population of submucosal immune cells in healing mucosal wounds (Figure 5B). A decrease in these populations of CD11b-expressing cells, and a corresponding decrease in SAA1 expression in healing wound bed immune infiltrates, was seen on days 4 and 6 of wound healing. These observations support the presence of SAA1 expression in infiltrating mucosal immune cells during wound closure and show that SAA1 wound bed immune cell expression levels correlate with SAA1 levels detected in ex vivo wound tissue culture supernatants (Figure 4A). The epithelium flanking wound beds also expresses significant levels of SAA1 (Figure 5). However, epithelial SAA1 expression did not appear significantly changed between wounded and nonwounded tissues at any time point during the mucosal repair.

Figure 5.

SAA1 expression in colonic wound beds. A: Representative photomicrographs illustrate immunofluorescence staining of SAA1 (yellow) in wounded versus nonwounded tissue. Arrows show prominent SAA1-expressing submucosal cell infiltrates in wound beds, whereas submucosa in nonwounded mucosa lacks significant SAA1-expressing infiltrates. Isotype control is displayed (right panel). B: Immunofluorescence staining shows changing levels of SAA1 (yellow) expression in healing wound beds (arrows). Day 1 wound beds show histologic evidence of acute injury, including submucosal edema and an inflammatory cell infiltrate, but SAA1 expression is largely absent in submucosal wound bed immune cell infiltrates. Day 2 submucosal infiltrates show strong SAA1 staining, whereas healing wound beds on subsequent days show progressively less SAA1 expression. CD11b (red) staining was used to identify myeloid immune cells, and colabeling of SAA1 and CD11b was observed in a large population of submucosal cells, with a maximum density in day 2 healing mucosal wounds. A decrease in CD11b-expressing cells, and a corresponding decrease in SAA1 expression in healing wound beds, was seen on days 4 and 6 of healing. Bottom row: High-power images of SAA1/CD11b coexpression in day 2 wound beds [region of interest (ROI) marked by a dashed box in day 2 wound merge]. Photomicrographs are representative of three mice per time point, with at least two wounds per mouse. Scale bars = 100 μm (A and B).

Discussion

Using in vitro techniques examining effects of SAA1 on epithelial migration, spreading, and attachment, we present evidence that SAA1 plays a significant role in epithelial wound healing. Our results demonstrate SAA1 induces both cell migration and spreading via FPR2 signaling and is associated with intracellular increases in ROS production as well as alterations in phosphorylated p130 CAS localization in cells at the leading edge of the migrating epithelial sheet. In addition, we find SAA1 regulates cell attachment to specific components of the extracellular matrix. To investigate the relevance of the in vitro findings in the context of the intestinal wound environment, a well-accepted model of in vivo wound recovery was used and temporally dependent SAA1 elaboration from cultured healing wound beds was identified by ELISA testing. In turn, immunofluorescence staining of wound beds identified changing patterns of SAA1 expression in wound bed immune cell infiltrates. Absent in nonwounded tissues, the presence of the SAA1-expressing infiltrates in wounded tissues mirrors the significantly elevated elaboration of SAA1 in wounded compared with nonwounded tissue, as seen by ELISA. Moreover, the pattern of SAA1/CD11b coexpression in immune infiltrates correlates with the rise and fall of SAA1 supernatant elaboration seen across time points, providing evidence that this immune cell infiltrate represents a significant source of SAA1 to migrating epithelial cells.

The ability for SAA to promote a prorestitutive phenotype in colonic epithelial cells has not been described to date; however, the current findings are supported by previous studies examining the effects of SAA on other cell types, mediated through various different receptors.3, 12, 13, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33 In these investigations, SAA has been shown to induce a promigratory phenotype in synovial and endothelial cells in both in vitro and tissue models of rheumatoid arthritis.12, 13 In this context, SAA has two well-established receptors, FPR2 (formerly FPRL-1) and scavenger receptor class B member 1, although additional evidence supports a role for toll-like receptor 2 signaling.27, 28, 29 SAA also serves as a chemoattractant for human and murine neutrophils, a process shown to be FPR2 dependent.3, 30, 31 On the basis of the finding that WRW4, an FPR2 antagonist, inhibits SAA1-induced migration and spreading, it is likely that a significant proportion of the prorepair effects of SAA1 are mediated by FPR2 signaling. In addition, studies have demonstrated that SAA induces migration of vascular smooth muscle cells, a process shown to be dependent on receptor for advanced glycation end products.32 Still, other studies have shown the existence of an additional SAA-responsive receptor, P2X7. SAA-induced stimulation of P2X7 expressed in human and mouse macrophages leads to, like in the cases of many of the aforementioned receptors, induction of cytokine production.33

To investigate a mechanism by which SAA1 facilitates colonic epithelial cell migration and spreading, wound healing models were treated with small-molecule competitive antagonists for several receptors with putative roles in SAA1 signaling. The results show significant inhibition of cell migration and spreading with WRW4, an FPR2-specific receptor antagonist. Although previous reports assessing dose-response of FPR-specific inhibitors using neutrophil-based assays have used WRW4 at 10 μmol/L for FPR2-specific inhibition,18 we believe the increase in dosage used herein (23 μmol/L) is modest. It is less than half the dose reportedly required to induce mild cross inhibition at the C5a receptor, a distinct G-protein–coupled receptor, during FPR antagonist testing.3, 15, 17 We also tested small molecule inhibitors that act on other putative SAA receptors. Minimal inhibition was observed using the FPR1-specific antagonist cyclosporine H, providing evidence that within colonic epithelial cells, SAA1 preferentially acts through FPR2. This finding is consistent with previous studies showing SAA promotes chemotaxis in neutrophils through FPR2, rather than FPR1, signaling.3 Inhibitors of receptor for advanced glycation end products and nucleotide receptor P2X7 showed no effect.17, 19, 20, 21 Although contributions from other receptors, such as scavenger receptor class B member 1 or toll-like receptor 2, were not assessed, the current findings support an important role for FPR2 in epithelial SAA1 signaling. They indicate SAA1 is able to induce migration in a broader range of cell types than previously appreciated.

Although enhanced epithelial cell migration was observed using SAA1 concentrations of 0.1 and 1.0 μmol/L, the highest concentration of SAA1 tested (10 μmol/L) showed decreased cell migration. The mechanism of the effect is unclear; however, published investigations have reported increased apoptosis in hepatic and hepatic stellate cells exposed to increased levels of SAA1.34 An increase in morphologically recognizable apoptosis in cells treated with lower concentrations of SAA1 was not observed; however, minimally increased apoptosis (<3%) was observed when cells were treated with the higher dose of 10 μmol/L SAA. As a corollary, increases in proliferation in SAA1-treated epithelial cells were not observed by 5-ethyl-2ʹ-deoxyuridine incorporation assay. Whether SAA1 treatment results in appreciable changes in proliferation rate may be cell type dependent.29, 32

Migrating cells adhere to the extracellular matrix via focal adhesions that contain several regulatory proteins, such as p130 CAS, Paxillin, and Src, that regulate dynamics of integrins involved in cellular adhesion to extracellular matrix components. In addition to dynamic turnover of focal cell matrix adhesions, cellular protrusions (lamellipodia) at the leading edge of the migrating cell front are needed to propel the forward movement of the cells.1 Remodeling of focal adhesions is regulated by phosphorylation events in p130 CAS, Paxillin and Src, among others. p130 CAS has been shown to play a pivotal scaffolding role during formation of focal adhesions.35 In addition, recent work by our group has shown that phosphorylation of p130 CAS regulates cell migration and spreading.23 In the present study, SAA1 treatment was associated with changes in phosphorylated p130 CAS localization with increases in labeling at the peripheral edge of lamellipodia extrusions of migrating cells, suggesting that SAA1 influences modifications in this protein that, in turn, influence epithelial movement into the wounded area.

Previous work has also shown that p130 CAS phosphorylation is redox dependent and may be stimulated by ROS generated in the wounded tissue by either infiltrating phagocytes or NADPH-oxidase 1 within epithelial cells themselves.23 The paradigm of low physiological levels of intracellular ROS acting as secondary messengers within signaling cascades important to epithelial restitution is well established. Previous studies in our laboratory as well as others have documented ROS production as a downstream signaling event of FPR activation by bacterially specific peptides and by endogenously produced mediators present in the immediate wound environment.2, 36 ROS has been shown to selectively and reversibly inhibit specific regulatory phosphatases that, under normal conditions, dephosphorylate their targets and result in the suppression of focal adhesion complex formation and extracellular signal regulated kinase–mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphorylation. ROS production, however, inactivates these phosphatases, leading to increased focal adhesion kinase and extracellular signal regulated kinase phosphorylation and subsequent increased cell migration as well as proliferation, respectively. The present study provides evidence that SAA1 is also capable of inducing intracellular ROS production. Coupled with our findings that SAA1 treatment activates FPR2 to increase epithelial cell migration and is associated with altered phosphorylated p130 CAS staining within lamellipodia, we propose that SAA1-stimulated ROS production is an additional example by which an endogenously produced mediator may lead to epithelial wound restitution through redox-dependent signaling.

Although in vitro work demonstrating SAA1's ability to induce prorestitutive phenotypes is compelling, whether SAA1 is actually present in the local intestinal wound environment to exact such effects is yet to be demonstrated. The liver has long been recognized as a site of significant SAA synthesis responsible for the >1000-fold serum elevations seen during the acute-phase response.4 However, additional sites of extrahepatic synthesis, including epithelial cells lining the mucosa of the gastrointestinal tract and in immune cell populations, are also recognized.6, 7, 8, 9 Interestingly, the ELISA assay results showing wounded tissues consistently elaborate significantly greater amounts of SAA1 compared with intact mucosa provides substantial evidence that SAA1 is differentially present during intestinal wound healing. Furthermore, the immunostaining findings indicate SAA1 is expressed by immune cell infiltrates and that the degree of SAA1/CD11b coexpression in the healing wound bed correlates with patterns of SAA1 elaboration detected by ELISA across time. These observations suggest immune cell populations unique to the wound environment may be an important source of SAA1, which may influence epithelial cell restitution and wound closure.

SAA1 immunostaining of wound beds also identified colonic epithelium itself as an additional potential source of SAA1. Indeed, the staining intensity for SAA1 within the superficial epithelium in closest proximity to luminal microbial contents is striking. Human and murine SAA1 expression within intestinal epithelium is recognized; however, its function in this microenvironment is still being elucidated.6, 8 Specifically, investigators have shown substantially enhanced expression of three murine SAA isoforms (SAA1, SAA2, and SAA3) after monocolonization of germ-free mice with segmented filamentous bacteria, indicating a critical role for intestinal microbiota in SAA expression.37 Other studies have shown colonic epithelial expression of SAA3 may also be induced by lipopolysaccharide.38 Consistent with these findings, the current immunostaining results clearly show SAA1 expression within colonic epithelium is strongest at the superficial colonic mucosal-luminal interface, with lower levels of staining in colonic crypts (Figure 5). Interestingly, however, epithelial SAA1 expression adjacent to wound beds was indistinguishable from epithelial SAA1 expression in samples of intact epithelium. Intact mucosa was harvested both from mice that had undergone biopsy wounding and mice without prior manipulation to rule out local-regional or systemic induction of SAA1 expression. Neither group showed epithelial SAA1 staining levels that differed appreciably from epithelium at the wound edge. Furthermore, staining intensity of SAA1 within epithelium adjacent to wound beds or otherwise did not change significantly during the wound healing time course. Although limitations of immunostaining for the detection of small changes in epithelial protein expression are acknowledged, the apparently stable epithelial SAA1 immunostaining levels flanking wound beds does not explain the clear change in SAA1 elaboration within wound bed culture supernatants, as seen by ELISA. SAA1 concentration in wound bed culture supernatants, however, appears to correlate with degrees of SAA1/CD11b coexpressing immune cells present within the submucosa of wound sites. Although relative levels of SAA1 expression within the most superficial single layer of epithelial cells appears greater than wound bed immune cells, the collective SAA1 expression among immune cells, of which only a small proportion are visualized at once in the two-dimensional images, may approach levels seen in the epithelium. The observation that immune cell expression of SAA1 is predominantly centered within the wound bed itself additionally suggests that this focally concentrated collection of SAA1-expressing immune cells may act as a directional gradient toward which epithelium may be attracted to migrate.

Although a role for epithelial-produced SAA1 acting in either an autocrine or a paracrine manner cannot be ruled out entirely, it is also possible that epithelial-expressed SAA1 is a damage-associated molecular pattern protein. When released into the local environment as a result of epithelial cell damage, it may serve to both recruit inflammatory cells to the site of barrier disruption and modulate local immune responses. In support of this theory, in vitro studies have clearly established SAA as an FPR2-dependent chemotactic agent for neutrophils.3 In addition, studies using lung models of acute and chronic inflammation show administered SAA stimulates FPR2-dependent neutrophil chemotaxis, resulting in increased numbers of CD11b/CD11c coexpressing infiltrates at sites of SAA exposure.39 Interestingly, similar to our observations in intestinal wound beds, CD11b-expressing immune cell infiltrates also reach reported maximum numbers at 2 to 3 days after SAA treatment in these studies. SAA released from damaged epithelial cells may also exert immunoregulatory effects on local resident and recruited inflammatory populations. Indeed, intestinal epithelial SAA expression has been shown to be critically important to the promotion of IL-17A expression in resident RAR-related orphan receptor gamma (RORγt) expressing T-cell subsets.40 In addition, studies in murine models of lung inflammation also demonstrate macrophage populations exposed to SAA express markedly increased levels of IL-1β and IL-6.39 IL-1β and IL-6 are important inducers of SAA expression themselves. The current ELISA wound culture supernatant results show that these cytokines, in addition to TNF-α, another key inducer of SAA expression, are substantially elevated in wounded colon tissue. These findings indicate that not only is the elevation of SAA1 within wound beds a general feature of an inflammatory response, but in addition shows that elevations of key inducers of SAA1 expression may be responsible for elevated SAA1 expression in wound bed immune cell infiltrates. Overall, we speculate that epithelial-derived SAA1 released into the local wound environment as a result of epithelial cell damage serves to promote chemotaxis of neutrophils to the wound site and that IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α produced by the wound inflammatory reaction may, in turn, induce SAA1 expression in resident and recruited immune cells.9, 24, 25, 26

In conclusion, our findings indicate SAA1 is an important inducer of processes critical for epithelial wound recovery. In addition, SAA1 is specifically and dynamically expressed during the healing of intestinal mucosal injury. Although these findings suggest an important role for SAA1 in intestinal wound recovery, additional studies characterizing the effects of SAA1 on epithelial migration in vivo are required. In particular, our finding that higher doses of SAA1 (10 μmol/L) resulted in inhibited cell migration indicates that future in vivo studies should be designed cognizant of the need for careful SAA1 dose titration. In addition, because SAA1 expression is induced by inflammatory cytokines, an additional aspect not addressed in our study is how anti-inflammatory medications used to treat inflammatory bowel disease, such as 5-aminosalicylates and anti–TNF-α inhibitors, modulate SAA1 expression.24 Although elevated SAA1 levels may be detrimental to wound healing, given SAA1's ability to stimulate epithelial migration and spreading at lower concentrations, suppression of SAA1 production in the local wound environment as a consequence of broad anti-inflammatory treatment may have significant implications for the regulation of epithelial restitution. Often characterized as a protein with proinflammatory cytokine-like properties, our findings nevertheless provide evidence that this acute-phase reactant protein is important in driving reparative responses. In turn, although additional evidence is required, the current evidence suggests more selective anti-inflammatory treatments may allow for more efficient and expedient intestinal wound healing.

Acknowledgments

B.H.H. conceived the study and wrote the manuscript; B.H.H. and J.D.M. optimized and conducted the experiments; D.S. and M.N.O.L. performed video microscopy; B.J.S. and A.A.W. aided with statistical analysis; A.S.N. and A.N. designed experiments, interpreted results, wrote the manuscript, and provided funding; all authors had full access to the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis; all authors contributed to evaluating and interpreting the data.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH grants DK089763 (A.N. and A.S.N.) and DK055679 (A.N.), Crohn's and Colitis Foundation Career Development Award 451678 (J.D.M.), the German Research Foundation (DFG) (D.S.), and the Emory University Integrated Cellular Imaging Microscopy Core.

B.H.H. and J.D.M. contributed equally to this work, and A.N. and A.S.N. contributed equally to this work as senior authors.

Disclosures: None declared.

Current address of B.H.H., Department of Pathology, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2017.12.013.

Contributor Information

Asma Nusrat, Email: anusrat@med.umich.edu.

Andrew S. Neish, Email: aneish@emory.edu.

Supplemental Data

Supplemental Figure S1.

Caco-2 intestinal epithelial cells are induced to migrate with SAA1. Model human intestinal epithelial Caco-2 cells also demonstrate significantly induced migration when treated with SAA1 (1 μmol/L, 18 hours). Experiment was repeated twice. n = 3. ∗∗∗P < 0.001 (t-test).

Supplemental Figure S2.

Cell proliferation rate during SAA1-induced epithelial migration. A: SAA1 induces cell migration without significant effects on cell proliferation. B: Representative images of nuclear 5-ethyl-2ʹ-deoxyuridine (EdU) incorporation (green) at epithelial wound edge (nuclei, blue). Experiment was performed three times. Statistical significance was determined by t-test. n = 3 (A and B). Scale bars = 250 μm (B).

Supplemental Figure S3.

E-cadherin isotype control. Left panel: E-cadherin antibody stains cell membranes (green) and is used to aid in determination of cell diameter (nuclei, blue). Right panel: Isotype control shows absent membranous staining. Scale bars = 50 μm.

Supplemental Figure S4.

Effects of receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) and P2X7 inhibitors on SAA1-induced epithelial cell migration. Competitive inhibitors of other putative SAA receptors (A 438079 hydrochloride, P2X7 antagonist, 10 μmol/L; FPS-ZM1, RAGE antagonist, 0.25 μmol/L) did not inhibit SAA1-induced migration. Experiments were performed in duplicate. n = 6 for each treatment group. ∗∗∗P < 0.001 for SAA1 versus control (t-test). DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide.

Supplemental Figure S5.

Phosphorylated p130 Crk-associated substrate (pCAS) isotype control. Left panel: pCAS antibody staining highlights sites of cell-matrix adhesion (green) within cellular protrusions. Right panel: These complexes show no staining in the isotype control. Actin filaments (red) are highlighted by phalloidin, and nuclei (blue) are highlighted by DAPI. Scale bars = 30 μm.

Supplemental Figure S6.

SAA selectively regulates epithelial restitutive signaling events. A: Western blot showing no changes in phosphorylated p130 Crk-associated substrate (CAS) levels despite changes in p130 CAS localization. B: SAA1 treatment also does not result in significant changes in cellular phosphorylation levels of other focal adhesion proteins tested. Experiment was performed twice. n = 1 (A and B).

Real-time imaging of SAA1-induced epithelial cell migration (control). Video obtained at 0 to 24 hours. SAA1-treated cells concurrently incubated with WRW4 demonstrate inhibited migration. Original magnification, ×5.

Real-time imaging of SAA1-induced epithelial cell migration (SAA1, 1 μmol/L). Video obtained at 0 to 24 hours. SAA1-treated cells concurrently incubated with WRW4 demonstrate inhibited migration. Original magnification, ×5.

Real-time imaging of SAA1-induced epithelial cell migration (SAA1, 1 μmol/L, + WRW4, 23 μmol/L). Video obtained at 0 to 24 hours. SAA1-treated cells concurrently incubated with WRW4 demonstrate inhibited migration. Original magnification, ×5.

Real-time imaging of SAA1-induced epithelial cell migration (control). Video obtained at 6 to 24 hours. Cells concurrently treated with SAA1 and WRW4 demonstrate inhibited migration. Original magnification, ×20.

Real-time imaging of SAA1-induced epithelial cell migration (SAA1, 1 μmol/L). Video obtained at 6 to 24 hours. Cells concurrently treated with SAA1 and WRW4 demonstrate inhibited migration. Original magnification, ×20.

Real-time imaging of SAA1-induced epithelial cell migration (SAA1, 1 μmol/L, + WRW4, 23 μmol/L). Video obtained at 6 to 24 hours. Cells concurrently treated with SAA1 and WRW4 demonstrate inhibited migration. Original magnification, ×20.

References

- 1.Lauffenburger D.A., Horwitz A.F. Cell migration: a physically integrated molecular process. Cell. 1996;84:359–369. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81280-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leoni G., Alam A., Neumann P.A., Lambeth J.D., Cheng G., McCoy J., Hilgarth R.S., Kundu K., Murthy N., Kusters D., Reutelingsperger C., Perretti M., Parkos C.A., Neish A.S., Nusrat A. Annexin A1, formyl peptide receptor, and NOX1 orchestrate epithelial repair. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:443–454. doi: 10.1172/JCI65831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liang T.S., Wang J.M., Murphy P.M., Gao J.L. Serum amyloid A is a chemotactic agonist at FPR2, a low-affinity N-formylpeptide receptor on mouse neutrophils. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;270:331–335. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cray C., Zaias J., Altman N.H. Acute phase response in animals: a review. Comp Med. 2009;59:517–526. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Urieli-Shoval S., Linke R.P., Matzner Y. Expression and function of serum amyloid A, a major acute-phase protein, in normal and disease states. Curr Opin Hematol. 2000;7:64–69. doi: 10.1097/00062752-200001000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meek R.L., Eriksen N., Benditt E.P. Serum amyloid A in the mouse: sites of uptake and mRNA expression. Am J Pathol. 1989;135:411–419. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ray B.K., Ray A. Induction of serum amyloid A (SAA) gene by SAA-activating sequence-binding factor (SAF) in monocyte/macrophage cells: evidence for a functional synergy between SAF and Sp1. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28948–28953. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.46.28948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Urieli-Shoval S., Cohen P., Eisenberg S., Matzner Y. Widespread expression of serum amyloid A in histologically normal human tissues: predominant localization to the epithelium. J Histochem Cytochem. 1998;46:1377–1384. doi: 10.1177/002215549804601206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Urieli-Shoval S., Meek R.L., Hanson R.H., Eriksen N., Benditt E.P. Human serum amyloid A genes are expressed in monocyte/macrophage cell lines. Am J Pathol. 1994;145:650–660. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meek R.L., Benditt E.P. Amyloid A gene family expression in different mouse tissues. J Exp Med. 1986;164:2006–2017. doi: 10.1084/jem.164.6.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Hara R., Murphy E.P., Whitehead A.S., FitzGerald O., Bresnihan B. Acute-phase serum amyloid A production by rheumatoid arthritis synovial tissue. Arthritis Res. 2000;2:142–144. doi: 10.1186/ar78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Connolly M., Marrelli A., Blades M., McCormick J., Maderna P., Godson C., Mullan R., FitzGerald O., Bresnihan B., Pitzalis C., Veale D.J., Fearon U. Acute serum amyloid A induces migration, angiogenesis, and inflammation in synovial cells in vitro and in a human rheumatoid arthritis/SCID mouse chimera model. J Immunol. 2010;184:6427–6437. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Connolly M., Veale D.J., Fearon U. Acute serum amyloid A regulates cytoskeletal rearrangement, cell matrix interactions and promotes cell migration in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1296–1303. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.142240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Howard B.A., Wang M.Z., Campa M.J., Corro C., Fitzgerald M.C., Patz E.F., Jr. Identification and validation of a potential lung cancer serum biomarker detected by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight spectra analysis. Proteomics. 2003;3:1720–1724. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wenzel-Seifert K., Seifert R. Cyclosporin H is a potent and selective formyl peptide receptor antagonist: comparison with N-t-butoxycarbonyl-L-phenylalanyl-L-leucyl-L-phenylalanyl-L-leucyl-L-phenylalanine and cyclosporins A, B, C, D, and E. J Immunol. 1993;150:4591–4599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lisanti M.P., Caras I.W., Davitz M.A., Rodriguez-Boulan E. A glycophospholipid membrane anchor acts as an apical targeting signal in polarized epithelial cells. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:2145–2156. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.5.2145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bae Y.S., Lee H.Y., Jo E.J., Kim J.I., Kang H.K., Ye R.D., Kwak J.Y., Ryu S.H. Identification of peptides that antagonize formyl peptide receptor-like 1-mediated signaling. J Immunol. 2004;173:607–614. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.1.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stenfeldt A.L., Karlsson J., Wenneras C., Bylund J., Fu H., Dahlgren C. Cyclosporin H, Boc-MLF and Boc-FLFLF are antagonists that preferentially inhibit activity triggered through the formyl peptide receptor. Inflammation. 2007;30:224–229. doi: 10.1007/s10753-007-9040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manigrasso M.B., Pan J., Rai V., Zhang J., Reverdatto S., Quadri N., DeVita R.J., Ramasamy R., Shekhtman A., Schmidt A.M. Small molecule inhibition of ligand-stimulated RAGE-DIAPH1 signal transduction. Sci Rep. 2016;6:22450. doi: 10.1038/srep22450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chatterjee S., Rana R., Corbett J., Kadiiska M.B., Goldstein J., Mason R.P. P2X7 receptor-NADPH oxidase axis mediates protein radical formation and Kupffer cell activation in carbon tetrachloride-mediated steatohepatitis in obese mice. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52:1666–1679. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deane R., Singh I., Sagare A.P., Bell R.D., Ross N.T., LaRue B., Love R., Perry S., Paquette N., Deane R.J., Thiyagarajan M., Zarcone T., Fritz G., Friedman A.E., Miller B.L., Zlokovic B.V. A multimodal RAGE-specific inhibitor reduces amyloid beta-mediated brain disorder in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:1377–1392. doi: 10.1172/JCI58642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fonseca P.M., Shin N.Y., Brabek J., Ryzhova L., Wu J., Hanks S.K. Regulation and localization of CAS substrate domain tyrosine phosphorylation. Cell Signal. 2004;16:621–629. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matthews J.D., Sumagin R., Hinrichs B., Nusrat A., Parkos C.A., Neish A.S. Redox control of Cas phosphorylation requires Abl kinase in regulation of intestinal epithelial cell spreading and migration. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2016;311:G458–G465. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00189.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thorn C.F., Lu Z.Y., Whitehead A.S. Regulation of the human acute phase serum amyloid A genes by tumour necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-6 and glucocorticoids in hepatic and epithelial cell lines. Scand J Immunol. 2004;59:152–158. doi: 10.1111/j.0300-9475.2004.01369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jensen L.E., Whitehead A.S. Regulation of serum amyloid A protein expression during the acute-phase response. Biochem J. 1998;334:489–503. doi: 10.1042/bj3340489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith J.W., McDonald T.L. Production of serum amyloid A and C-reactive protein by HepG2 cells stimulated with combinations of cytokines or monocyte conditioned media: the effects of prednisolone. Clin Exp Immunol. 1992;90:293–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb07945.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mullan R.H., McCormick J., Connolly M., Bresnihan B., Veale D.J., Fearon U. A role for the high-density lipoprotein receptor SR-B1 in synovial inflammation via serum amyloid-A. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:1999–2008. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee M.S., Yoo S.A., Cho C.S., Suh P.G., Kim W.U., Ryu S.H. Serum amyloid A binding to formyl peptide receptor-like 1 induces synovial hyperplasia and angiogenesis. J Immunol. 2006;177:5585–5594. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.8.5585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Connolly M., Rooney P.R., McGarry T., Maratha A.X., McCormick J., Miggin S.M., Veale D.J., Fearon U. Acute serum amyloid A is an endogenous TLR2 ligand that mediates inflammatory and angiogenic mechanisms. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:1392–1398. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Su S.B., Gong W., Gao J.L., Shen W., Murphy P.M., Oppenheim J.J., Wang J.M. A seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor, FPRL1, mediates the chemotactic activity of serum amyloid A for human phagocytic cells. J Exp Med. 1999;189:395–402. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.2.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Badolato R., Wang J.M., Murphy W.J., Lloyd A.R., Michiel D.F., Bausserman L.L., Kelvin D.J., Oppenheim J.J. Serum amyloid A is a chemoattractant: induction of migration, adhesion, and tissue infiltration of monocytes and polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J Exp Med. 1994;180:203–209. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Belmokhtar K., Robert T., Ortillon J., Braconnier A., Vuiblet V., Boulagnon-Rombi C., Diebold M.D., Pietrement C., Schmidt A.M., Rieu P., Toure F. Signaling of serum amyloid A through receptor for advanced glycation end products as a possible mechanism for uremia-related atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36:800–809. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Niemi K., Teirila L., Lappalainen J., Rajamaki K., Baumann M.H., Oorni K., Wolff H., Kovanen P.T., Matikainen S., Eklund K.K. Serum amyloid A activates the NLRP3 inflammasome via P2X7 receptor and a cathepsin B-sensitive pathway. J Immunol. 2011;186:6119–6128. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ji Y.R., Kim H.J., Bae K.B., Lee S., Kim M.O., Ryoo Z.Y. Hepatic serum amyloid A1 aggravates T cell-mediated hepatitis by inducing chemokines via Toll-like receptor 2 in mice. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:12804–12811. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.635763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abassi Y.A., Rehn M., Ekman N., Alitalo K., Vuori K. p130Cas couples the tyrosine kinase Bmx/Etk with regulation of the actin cytoskeleton and cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:35636–35643. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306438200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alam A., Leoni G., Wentworth C.C., Kwal J.M., Wu H., Ardita C.S., Swanson P.A., Lambeth J.D., Jones R.M., Nusrat A., Neish A.S. Redox signaling regulates commensal-mediated mucosal homeostasis and restitution and requires formyl peptide receptor 1. Mucosal Immunol. 2014;7:645–655. doi: 10.1038/mi.2013.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Atarashi K., Tanoue T., Ando M., Kamada N., Nagano Y., Narushima S., Suda W., Imaoka A., Setoyama H., Nagamori T., Ishikawa E., Shima T., Hara T., Kado S., Jinnohara T., Ohno H., Kondo T., Toyooka K., Watanabe E., Yokoyama S., Tokoro S., Mori H., Noguchi Y., Morita H., Ivanov I.I., Sugiyama T., Nunez G., Camp J.G., Hattori M., Umesaki Y., Honda K. Th17 cell induction by adhesion of microbes to intestinal epithelial cells. Cell. 2015;163:367–380. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reigstad C.S., Lunden G.O., Felin J., Backhed F. Regulation of serum amyloid A3 (SAA3) in mouse colonic epithelium and adipose tissue by the intestinal microbiota. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5842. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anthony D., McQualter J.L., Bishara M., Lim E.X., Yatmaz S., Seow H.J., Hansen M., Thompson M., Hamilton J.A., Irving L.B., Levy B.D., Vlahos R., Anderson G.P., Bozinovski S. SAA drives proinflammatory heterotypic macrophage differentiation in the lung via CSF-1R-dependent signaling. FASEB J. 2014;28:3867–3877. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-250332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sano T., Huang W., Hall J.A., Yang Y., Chen A., Gavzy S.J., Lee J.Y., Ziel J.W., Miraldi E.R., Domingos A.I., Bonneau R., Littman D.R. An IL-23R/IL-22 circuit regulates epithelial serum amyloid A to promote local effector Th17 responses. Cell. 2015;163:381–393. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Real-time imaging of SAA1-induced epithelial cell migration (control). Video obtained at 0 to 24 hours. SAA1-treated cells concurrently incubated with WRW4 demonstrate inhibited migration. Original magnification, ×5.

Real-time imaging of SAA1-induced epithelial cell migration (SAA1, 1 μmol/L). Video obtained at 0 to 24 hours. SAA1-treated cells concurrently incubated with WRW4 demonstrate inhibited migration. Original magnification, ×5.

Real-time imaging of SAA1-induced epithelial cell migration (SAA1, 1 μmol/L, + WRW4, 23 μmol/L). Video obtained at 0 to 24 hours. SAA1-treated cells concurrently incubated with WRW4 demonstrate inhibited migration. Original magnification, ×5.

Real-time imaging of SAA1-induced epithelial cell migration (control). Video obtained at 6 to 24 hours. Cells concurrently treated with SAA1 and WRW4 demonstrate inhibited migration. Original magnification, ×20.

Real-time imaging of SAA1-induced epithelial cell migration (SAA1, 1 μmol/L). Video obtained at 6 to 24 hours. Cells concurrently treated with SAA1 and WRW4 demonstrate inhibited migration. Original magnification, ×20.

Real-time imaging of SAA1-induced epithelial cell migration (SAA1, 1 μmol/L, + WRW4, 23 μmol/L). Video obtained at 6 to 24 hours. Cells concurrently treated with SAA1 and WRW4 demonstrate inhibited migration. Original magnification, ×20.