Abstract

Background

A number of phenols and parabens are added to consumer products for a variety of functions, and have been found at detectable levels in the majority of the U.S. population. Among other functions, thyroid hormones are essential in fetal neurodevelopment, and could be impacted by the endocrine disrupting effects of phenols/parabens. The present study investigated the association between ten maternal urinary phenol and paraben biomarkers (bisphenol S, triclosan, triclocarban, benzophenone-3, 2,4-dichlorophenol, 2,5-dichlorophenol, and ethyl, butyl, methyl and propyl paraben) and four plasma thyroid hormones in 439 pregnant women in a case-control sample nested within a cohort study based in Boston, MA.

Methods

Urine and blood samples were collected from up to four visits during pregnancy (median weeks of gestation at each visit: Visit 1: 9.64, Visit 2: 17.9, Visit 3: 26.0, Visit 4: 35.1). Linear mixed models were constructed to take into account the repeated measures jointly, followed by multivariate linear regression models stratified by gestational age to explore potential windows of susceptibility.

Results

We observed decreased total triiodothyronine (T3) in relation to an IQR increase in benzophenone-3 (percent change [%Δ] = −2.07; 95% confidence interval [CI] = −4.16, 0.01), butyl paraben (%Δ = −2.76; 95% CI = −5.25, −0.26) and triclosan (%Δ = −2.53; 95% CI = −4.75, −0.30), and triclocarban at levels above the LOD (%Δ = −5.71; 95% CI = −10.45, −0.97). A 2.41 % increase in T3 was associated with an IQR increase in methyl paraben (95% CI = 0.58, 4.24). We also detected a negative association between free thyroxine (FT4) and propyl paraben (%Δ = −3.14; 95% CI = −6.12, −0.06), and a suggestive positive association between total thyroxine (T4) and methyl paraben (%Δ = 1.19; 95% CI = −0.10, 2.47). Gestational age-specific multivariate regression analyses showed that the magnitude and direction of some of the observed associations were dependent on the timing of exposure.

Conclusion

Certain phenols and parabens were associated with altered thyroid hormone levels during pregnancy, and the timing of exposure influenced the association between phenol and paraben, and hormone concentrations. These changes may contribute to downstream maternal and fetal health outcomes. Additional research is required to replicate the associations, and determine the potential biological mechanisms underlying the observed associations.

Keywords: Parabens, Phenols, Thyroid Hormones, Pregnancy, In-utero

1. Introduction

There are thousands of chemicals found in personal care products (PCP) and household items to which humans could potentially be exposed (Egeghy et al., 2012; Guo and Kannan, 2013). Usage of PCPs continues during pregnancy, and this may have unique effects on the mother and/or her developing fetus (Braun et al., 2014; Lang et al., 2016).

Phenols and parabens are among the chemicals used in PCPs, and are regularly found at detectable levels in the U.S. population (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017). Phenols regularly detected in exposure biomonitoring studies include triclosan (TCS), triclocarban (TCB), benzophenone-3 (BP-3), bisphenol-A (BPA), bisphenol-S (BPS), 2,4-dichlorophenol (2,4-DCP) and 2,5-dichlorophenol (2,5-DCP). Parabens, TCS and TCB are used in PCPs such as soaps and makeup for their anti-microbial properties (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017). The phenol BP-3 is a UV-filter, and is used in sunscreen, cosmetics and some plastic products (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017). BPS is a common alternative to BPA, and is found in foods, plastics and paper products (Rochester and Bolden, 2015). 2,4-DCP and 2,5-DCP are biomarkers of a compound used in mothballs and room deodorizers; 2,4-DCP is also a metabolite of a herbicide used as a weed killer (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017).

Although results have been conflicting, in vitro, animal and human studies have linked a range of phenols and parabens with changes in thyroid hormones (Andrianou et al., 2016; Guignard et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2017; Koeppe et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2017; H. Wang et al., 2017; X. Wang et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2017). Studies have also linked these exposures to a series of adverse health effects that could potentially be mediated through the thyroid hormone system, including changes in pubertal development (Wolff et al., 2015), adverse birth outcomes (Philippat et al., 2012; Tang et al., 2013), male infertility (Den Hond et al., 2015), diminished female fecundity (Vélez et al., 2015), increases in oxidative stress (Watkins et al., 2015), and childhood adiposity (Buckley et al., 2016), among other health effects.

Thyroid hormones, triiodothyronin (T3) and thyroxine (T4), are produced in the thyroid gland, and their levels are negatively controlled by thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) from the pituitary gland via the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis (Tingi et al., 2016). The fetal thyroid only begins to produce hormones at 10–12 weeks gestation, and is completely dependent on maternal thyroid hormones for neurodevelopment in its first weeks of life, particularly T4 (Mastorakos et al., 2007; Williams, 2008; Zoeller et al., 2002). Additionally, thyroid hormones (maternal and fetal) are essential to the development of fetal tissues, and fetal growth promotion (Forhead and Fowden, 2014). Given this, and the complexity in the hypothalamic–pituitary–thyroid axis, even slight alterations in thyroid hormones could lead to adverse effects in the child (Alemu et al., 2016; Mead, 2004). In fact, subclinical maternal thyroid dysfunction has been associated with low birth weight, low Apgar scores, and neurological disabilities (Braun, 2017; Chen et al., 2014; Saki et al., 2014). It is, therefore, important to understand the effects of in-utero exposure to chemicals such as phenols and parabens on maternal thyroid hormones.

Our group recently reported associations between phenols and parabens and maternal thyroid hormones in pregnancy in a small prospective cohort study in Puerto Rico (Aker et al., 2016). The present study aimed to test these relationships in a larger study of pregnant women recruited in Boston, USA. We published a study on the effects of BPA on thyroid hormones in this same cohort since BPA was initially the only phenol measured in our samples (Aung et al., 2017); the analytical method was recently expanded to include additional phenols and parabens, which are the focus of this study.

2. Methods

2.1 Study Population

The study population includes pregnant women who were participants in a case-control study nested within the longitudinal birth cohort study in Boston, MA, Lifecodes (Ferguson et al., 2014, 2015). Lifecodes enrolled 1,600 women from 2006–2008, of whom 1,181 were followed until delivery to live singletons. Women ages ≥18 years old were recruited early in pregnancy (< 15 weeks of gestation) between 2006 and 2008 and were eligible for participation if they were carrying a singleton, non-anomalous fetus and planned to deliver at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Additional information regarding recruitment and eligibility criteria are described in detail elsewhere (Ferguson et al., 2014; McElrath et al., 2012). Women were followed through the duration of their pregnancy and relevant health information as well as urine and blood samples were collected at initial study visit (Visit 1: median 9.64 weeks of gestation [range = 5.43–19.1 weeks]) as well as three subsequent visits: Visit 2 (median = 17.9 weeks of gestation [range = 14.9–32.1 weeks]), Visit 3 (median = 26.0 weeks of gestation [range = 22.9–36.3 weeks]), and Visit 4 (median = 35.1 weeks of gestation [range = 33.1–38.3]). The study protocols were approved by the ethics and research committees of the participating institutions, and all study participants provided written informed consent.

From the parent birth cohort, 130 women who delivered preterm (<37 weeks gestation) and 352 randomly selected women who delivered after a full term pregnancy (≥37 week gestation) were included in the case-control study. From these, we excluded participants who had pre-existing thyroid conditions such as thyroid cancer, Graves’ disease, and hyper- or hypothyroidism (N=41), and excluded those who did not provide any blood samples at any visit (N=2). Our final study population (N=439) included 116 preterm birth cases and 323 controls.

2.2 Phenol and paraben measurement

Spot urine samples were collected at each of the four visits. After collection, spot urine samples were divided into aliquots and frozen at −80°C until they were shipped overnight. The samples were analyzed at NSF International (Ann Arbor, MI) for six phenols (2,4-DCP, 2,5-DCP, BP-3, BPS, TCS, and TCB) and four parabens (ethyl-(EPB), methyl-(MPB), butyl-(BPB), and propyl-(PPB) paraben) using isotope dilution-liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (ID-LC-MS/MS). The analytical method was a modification of a method developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), as described previously (Lewis et al., 2013; Ye et al., 2005, 2006). Samples below the limit of detection (LOD) were assigned a value of LOD/√2 (Hornung and Reed, 1990). Urinary specific gravity (SG) was used to account for urinary dilution, and was measured using a digital handheld refractometer (AtagoCo., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). For descriptive, univariate data analysis, phenol and paraben concentrations were corrected for SG as follows: Pc = M [ (SGm − 1) / (SGi − 1) ], where Pc is the SG-corrected exposure concentration (ng/mL), M is the measured exposure concentration, SGm is the study population median urinary specific gravity (1.0196), and SGi is the individual’s urinary specific gravity. For bivariate and multivariate analysis, urinary specific gravity was included as a covariate in all models.

To minimize measurement error from the variability in urine dilution, we applied the method developed by O’Brien et al., 2016. In brief, we ran a linear mixed model (LMM) regressing SG on maternal age, extracted the predicted values of SG from that regression, calculated the ratio of SG and the predicted SG, and used this ratio to standardize the phenol and paraben measurements.

2.3 Thyroid hormone measurement

Blood samples were collected at each of the four visits. The samples were frozen at −80 °C until shipped overnight on dry ice to the analytical laboratory. Blood plasma was analyzed for free thyroxine (FT4), total thyroxine (T4), total triiodothyronine (T3), and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) at the Clinical Ligand Assay Service Satellite (CLASS) lab at the University of Michigan (Ann Arbor, MI). TSH, T3 and T4 were measured using an automated chemiluminescence immunoassay (Bayer ADVIA Centaur, Siemens Health Care Diagnostics, Inc.), and FT4 was measured using direct equilibrium dialysis followed by radioimmunoassay (IVD Technologies). Thyroid hormones were highly detected in the study population (Johns et al., 2017). TSH samples below the LOD (N=5) were assigned a level at the LOD level (0.01 μIU/mL). Given that the LOD for FT4 is not biologically feasible, samples <LOD for FT4 were regarded as missing values in our statistical analyses. The inter-assay coefficients of variation (CV) for all hormones ranged from 2.3% (for T3) to 10.4% (for FT4). The intra-assay CVs ranged from 1.2% (for T3) to 12.3% (for FT4). Volume limitations in some of the samples resulted in differences in the number of samples.

2.4 Statistical analyses

We applied inverse probability weighting to all statistical analyses in order to account for the study’s case-control design and over-representation of preterm birth cases in our sample. This ensures that the association observed between secondary outcomes (hormone levels) and biomarkers (phenols and parabens) in the present study population would be representative to the overall cohort population, and enhances the generalizability of our results (Richardson et al., 2007). We constructed the weights as the inverse of the selection probability for cases and controls from the set of eligible cases and controls in the entire cohort. Weighted distributions of key demographic characteristics were calculated. All biomarkers, and the hormones TSH and FT4, were positively-skewed, and were natural log-transformed. The distributions of T3 and T4 approximated normality and remained untransformed in all analyses. Geometric means and standard deviations were calculated for all SG-corrected biomarkers, hormones, and the ratio of T3/T4. The ratio between T3 and T4 provides an indication of thyroid homeostasis, specifically the peripheral conversion of T4 to T3 in tissues.

Two urinary biomarkers, BPS and TCB, were detected in less than 25% of the samples. Therefore, we categorized BPS and TCB into dichotomous variables for the statistical models, where 1 represented a detectable level (>LOD), and 0 was <LOD. The LOD for BPS and TCB was 0.1 ng/mL. BPS and TCB were analyzed as binary variables in all regression models, whereas all other biomarkers were analyzed continuously.

In our repeated measures analysis, we regressed one thyroid hormone on one urinary biomarker using Linear Mixed Models (LMM) with a subject-specific random intercept to account for intra-individual correlation of serial hormone measurements collected over time. The biomarker measures across time were treated as time varying variables in the model. Potential confounders were identified from the literature. They included socio-economic status, body mass index (BMI), alcohol and smoking during pregnancy, and age. The availability of private insurance was used as socioeconomic status indicator. Potential confounders that were found to change the main effect estimate by >10% were retained in the final models as covariates. Final models were adjusted for specific gravity, study visit, BMI at the first study visit, insurance provider, maternal age and gestational age at time of sample collection. To explore windows of susceptibility, we ran multiple linear regressions (MLR) stratified by gestational age, adjusted for the same covariates as those in LMMs. The gestational age groups were <15 weeks, 15–21 weeks, 21–30 weeks, and >30 weeks gestation. In addition to the visit-specific stratified analysis, to conduct a statistical test whether the associations between phenol and/or paraben biomarker varied by study visit of sample collection, we included in our repeated measures analysis interaction terms between urinary biomarkers and the study visit. We also re-ran our analyses in only term births status (>37 weeks gestation) as a sensitivity analysis. To make our results from these models including ln-transformed continuous biomarkers and/or outcomes more interpretable, we transformed regression coefficients to percent changes (and associated 95% confidence intervals) in hormone concentration in relation to the interquartile range (IQR) increase in urinary biomarker concentrations. Beta coefficients from models with categorical biomarkers (BPS and TCB) were transformed to percent changes (and associated 95% confidence intervals) in hormone concentration at biomarker levels above the LOD versus biomarker levels below the LOD. The alpha level was set at 0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted in R Version 3.2.2.

3. Results

The mean age of the study participants was 31.8 years, 66% attained at least some college education, 56% were White, and less than 20% depended on Medicaid (Table 1). The women also had low levels of smoking (7%) and alcohol use (4%) during pregnancy, and only 22% had a BMI level above 30 kg/m2.

Table 1.

Summary demographics of the 439 pregnant women in the sample

| N | % of cohort* | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–24 years | 54 | 12 |

| 25–29 years | 92 | 21 | |

| 30–34 years | 176 | 40 | |

| 35+ years | 117 | 27 | |

| Race/ethnicity | White | 247 | 56 |

| African-American | 75 | 17 | |

| Other | 117 | 27 | |

| Education | High school degree | 67 | 16 |

| Technical school | 76 | 18 | |

| Junior college or some college | 127 | 29 | |

| College graduate | 159 | 37 | |

| Health insurance provider | Private/HMO/Self-pay | 344 | 81 |

| Medicaid/SSI/MassHealth | 83 | 19 | |

| BMI at initial visit | < 25 kg/m2 | 227 | 52 |

| 25–29.9 kg/m2 | 113 | 26 | |

| ≥ 30 kg/m2 | 99 | 22 | |

| Tobacco use | Smoking during pregnancy | 31 | 7 |

| No smoking during pregnancy | 402 | 93 | |

| Alcohol use | Alcohol use during pregnancy | 18 | 4 |

| No alcohol use during pregnancy | 412 | 96 |

Weighted by case-control sampling probabilities to represent the general sampling population.

Table 2 shows the results of the univariate analyses conducted on the urinary biomarkers and hormone levels. Little variation was observed in urinary biomarker concentrations across pregnancy, whereas all hormones showed varied levels across the four time points in pregnancy, as was described previously in greater detail (Johns et al., 2016, 2017). MPB was detected at the highest levels among all biomarkers, followed by BP-3 (Supplemental Figure 1). MPB was strongly correlated with PPB (Correlation coefficient= 0.83), whereas BPB and EPB (Correlation coefficient =0.57), and 2,4-DCP and 2,5-DCP (Correlation coefficient=0.59) were moderately correlated. No other biomarker concentrations strongly correlated with one another. T3 and FT4 were correlated with T3/T4 (Correlation coefficients=0.74, −0.44, respectively), but T4 was weakly correlated with T3/T4 (Correlation coefficient=0.2) (Supplemental Figure 2). T3 and T4 were also moderately correlated (Correlation coefficient=0.46).

Table 2.

Weighted distributions of SG-corrected urinary phenols and parabens and thyroid hormones by study visit of sample collection in pregnancy (N = 439 subjects). Median gestational weeks: Visit 1: 10, Visit 2: 18, Visit 3: 26, Visit 4: 35.

| All | Visit 1 | Visit 2 | Visit 3 | Visit 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % LOD (LOD) | GM (GSD) | GM (GSD) | GM (GSD) | GM (GSD) | GM (GSD) | |

| Urinary Biomarkers (μg/L) | ||||||

| 2,4-DCP | 15.7 (0.2) | 0.89 (3.51) | 0.95 (3.85) | 0.93 (3.50)* | 0.81 (3.52)* | 0.88 (3.14)* |

| 2,5-DCP | 3.1 (0.2) | 5.11 (6.42) | 5.35 (7.08) | 5.63 (6.63) | 4.69 (6.46)* | 4.77 (5.47)* |

| BP-3 | 0.1 (0.4) | 55.82 (8.48) | 52.62 (8.16) | 61.66 (8.11) | 51.62 (8.76) | 57.94 (9.02) |

| BPB | 29.3 (0.2) | 1.19 (7.14) | 1.21 (7.53) | 1.29 (6.71) | 1.18 (7.39) | 1.09 (6.96) |

| EPB | 38.1 (1) | 3.56 (5.82) | 3.73 (6.20) | 3.92 (6.05) | 3.45 (5.67)* | 3.15 (5.33)* |

| MPB | 0.1 (1) | 169.64 (4.31) | 152.43 (4.14) | 208.05 (4.07) | 161.80 (4.55) | 161.49 (4.45) |

| PPB | 1 (0.2) | 37.35 (5.71) | 33.90 (5.67) | 50.85 (5.04)* | 34.36 (5.82) | 32.63 (6.23) |

| TCS | 17.4 (2) | 16.63 (6.65) | 16.82 (6.98) | 17.44 (6.20) | 14.91 (6.49) | 17.35 (6.95) |

| TCB | 85.9 (2) | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| BPS | 73.8 (0.4) | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| Thyroid Hormones | ||||||

| FT4 (ng/dL) | 98.2 (0.1) | 1.10 (1.52) | 1.37 (1.48) | 1.08 (1.49)* | 0.99 (1.50)* | 0.96 (1.45)* |

| TSH (μIU/mL) | 99.5 (0.01) | 1.13 (2.12) | 0.77 (2.75) | 1.29 (1.92)* | 1.27 (1.68)* | 1.31 (1.71)* |

| T3 (ng/mL) | 100 (0.1) | 1.56 (1.30) | 1.35 (1.31) | 1.61 (1.27)* | 1.65 (1.27)* | 1.66 (1.29)* |

| T4 (μg/dL) | 100 (0.3) | 10.22 (1.21) | 9.98 (1.22) | 10.61 (1.18)* | 10.29 (1.20)* | 10.01 (1.23) |

| T3/T4 ratio | - | 0.15 (1.27) | 0.14 (1.21) | 0.15 (1.24)* | 0.16 (1.27)* | 0.17 (1.29)* |

GM: Geometric mean

GSD: Geometric standard deviation

Significant difference (p<0.05) in urinary biomarker metabolite or thyroid hormone compared to reference (visit 1) using linear mixed models with a random intercept

Table 3 shows the results from LMMs, which included measurements collected at up to four time points in pregnancy. 2,4-DCP and 2,5-DCP were not associated with any thyroid hormones, although an IQR increase in 2,4-DCP was suggestively associated with 1.4% decrease in the T3/T4 ratio (percent change [%Δ] = −1.44; 95% confidence interval [CI] = −3.11, 0.22). There were significant 2–3% decreases in T3 in relation to an IQR increase in BP-3 (%Δ = −2.07; 95% CI = −4.16, 0.01), and TCS (%Δ = −2.53; 95% CI = −4.75, −0.30). TCB at levels above the LOD were also negatively associated with T3 (%Δ = −5.71; 95% CI = −10.45, −0.97). While an IQR increase in TCS was associated with a 7.7% increase in TSH (95% CI = 0.01, 16.02), TCB levels above the LOD were associated with a suggestive 13% decrease in TSH (%Δ = −12.86; 95% CI = −25.6, 2.05).

Table 3.

Results of the linear mixed models regressing thyroid hormones versus phenols and parabens: % change in thyroid hormone per IQR change in urinary biomarker concentration

| TSH (N=1069) | FT4 (N=1240) | T4 (N=1230) | T3 (N=993) | T3/T4 Ratio (N=985) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2,4-DCP | % Δ/IQR (95% CI) | 0.24 (−5.71, 6.57) | −0.30 (−3.46, 2.96) | 0.31 (−0.96, 1.58) | −1.33 (−3.15, 0.49) | −1.44 (−3.11, 0.22) |

| p value | 0.94 | 0.85 | 0.63 | 0.15 | 0.09* | |

| 2,5-DCP | % Δ/IQR (95% CI) | −2.71 (−9.13, 4.16) | −1.64 (−5.05, 1.90) | −0.06 (−1.53, 1.40) | −0.52 (−2.60, 1.56) | −0.36 (−2.28, 1.55) |

| p value | 0.43 | 0.36 | 0.93 | 0.63 | 0.71 | |

| BP-3 | % Δ/IQR (95% CI) | 5.42 (−1.58, 12.9) | −0.62 (−4.11, 3.00) | −1.13 (−2.59, 0.34) | −2.07 (−4.16, 0.01) | −1.33 (−3.24, 0.59) |

| p value | 0.13 | 0.73 | 0.13 | 0.05* | 0.18 | |

| BPS⋄ | % Δ (95% CI) | 9.77 (−0.89, 21.6) | −1.11 (−6.27, 4.34) | −0.30 (−0.19, 0.20) | −0.68 (−3.68, 2.33) | −0.54 (−3.29, 2.21) |

| p value | 0.07* | 0.68 | 0.77 | 0.66 | 0.70 | |

| TCS | % Δ/IQR (95% CI) | 7.72 (0.01, 16.02) | 1.22 (−2.59, 5.18) | −1.20 (−2.76, 0.35) | −2.53 (−4.75, −0.30) | −0.80 (−2.84, 1.25) |

| p value | 0.05** | 0.54 | 0.13 | 0.03** | 0.45 | |

| TCB⋄ | % Δ (95% CI) | −12.86 (−25.6, 2.05) | 1.14 (−6.98, 9.96) | −0.95 (−0.35, 0.27) | −5.71 (−10.45, −0.97) | −3.99 (−8.30, 0.33) |

| p value | 0.09 * | 0.79 | 0.56 | 0.02** | 0.07* | |

| EPB | % Δ/IQR (95% CI) | 2.84 (−3.92, 10.1) | 0.50 (−3.06, 4.18) | 0.67 (−0.77, 2.11) | −0.86 (−2.92, 1.20) | −1.87 (−3.76, 0.02) |

| p value | 0.42 | 0.79 | 0.36 | 0.41 | 0.05* | |

| MPB | % Δ/IQR (95% CI) | 0.55 (−5.45, 6.93) | −2.13 (−5.24, 1.09) | 1.19 (−0.10, 2.47) | 2.41 (0.58, 4.24) | 0.79 (−0.90, 2.48) |

| p value | 0.86 | 0.19 | 0.07* | 0.01** | 0.36 | |

| BPB | % Δ/IQR (95% CI) | 6.85 (−1.67, 16.1) | 0.43 (−3.86, 4.92) | 0.76 (−0.98, 2.49) | −2.76 (−5.25, −0.26) | −3.70 (−5.98, −1.42) |

| p value | 0.12 | 0.85 | 0.39 | 0.03** | 0.002** | |

| PPB | % Δ/IQR (95% CI) | 0.87 (−5.02, 7.13) | −3.14 (−6.12, −0.06) | 0.99 (−0.25, 2.22) | 1.41 (−0.36, 3.18) | 0.26 (−1.36, 1.88) |

| p value | 0.78 | 0.05** | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.76 |

Phenol metabolite was transformed into a dichotomous variable.

represents a p value below 0.10, and

represents a p value below 0.05.

There were no consistent associations among the parabens. There were 2.4% (%Δ = 2.41; 95% CI = 0.58, 4.24), and 1.2% (%Δ = 1.19; 95% CI = −0.10, 2.47) increases in T3 and T4, respectively, with an IQR increase in MPB. BPB was associated with a 2.8% (%Δ = −2.76; 95% CI = −5.25, −0.26), and 3.7% (%Δ = −3.70; 95% CI = −5.98) decrease in T3 and T3/T4 ratio. EPB was also associated with a reduced T3/T4 ratio (%Δ = −1.87; 95% CI = −3.76, 0.02). PPB was inversely associated with FT4 (%Δ = −3.14; 95% CI = −6.12, −0.06).

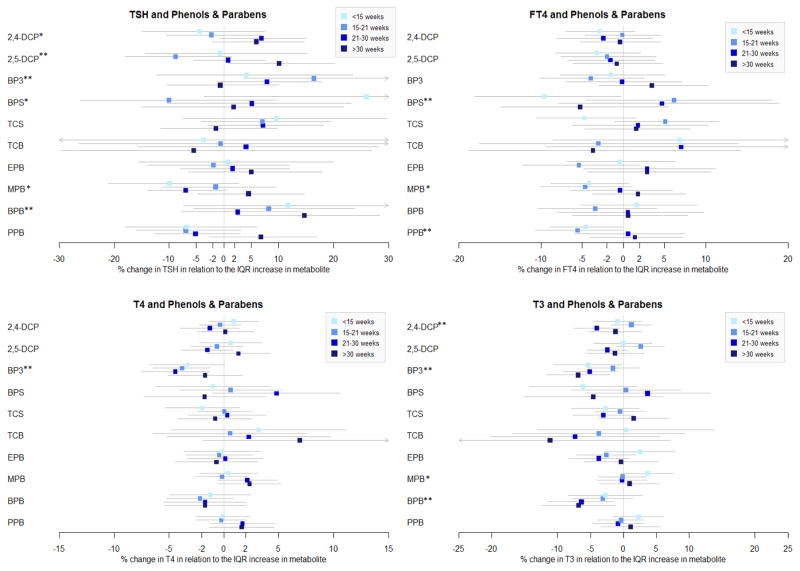

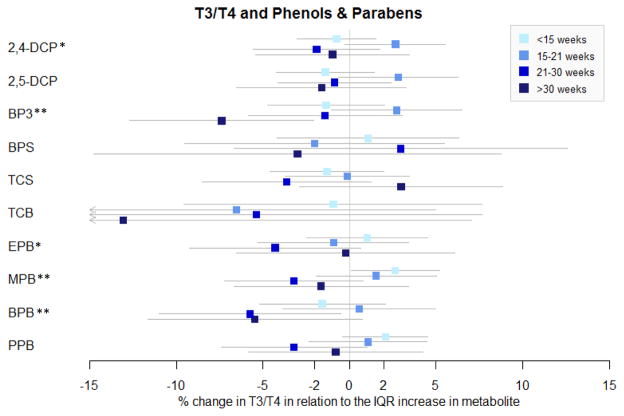

To further understand these associations and explore the relationships at specific time points, multiple linear regressions were conducted stratifying by GA (Figure 1 and Supplemental Table 1). 2,4-DCP was associated with a decrease in T3 (%Δ = −4.05; 95% CI = −7.49, −0.61), and a marginal increase in TSH (%Δ = 6.81; 95% CI = −0.74, 14.94) at 21–30 weeks. 2,4-DCP and 2,5-DCP were associated with decreases in TSH <21 weeks GA, and increases in TSH >21 weeks GA, although only the association between TSH and 2,5-DCP and >30 weeks GA reached statistical association (%Δ = 10.03; 95% CI = 0.74, 20.19). This change in the direction of the associations between 2,4-DCP and 2,5-DCP and TSH by timing in pregnancy was further reflected in the significant interaction terms between the phenol and visit in LMMs.

Figure 1.

Multiple linear regressions of thyroid hormone versus urinary concentrations of phenol/paraben stratified by gestational age. BPS and TCB are categorical variables. Associations with BPS and TCB are transformed to % changes in the hormone comparing urinary biomarkers above and below the LOD.

*represents at least one marginal association between the urinary concentration and the hormone across the four time points. ** represents at least one significant association between the urinary concentration and the hormone across the four time points.

In contrast to LMM results, BP-3 was associated with all thyroid hormones at at least one time point in MLR models. BP-3 was associated with 5–7% decreases in T3 at all gestational ages except at 15–21 weeks GA, 3–4% decreases in T4 at all gestational ages except at >30 weeks GA, and 8–16% increases in TSH at 15–21 and 21–30 weeks GA. BP-3 was additionally associated with a 7.4% decrease in the T3/T4 ratio at >30 weeks GA (%Δ = −7.37; 95% CI = −12.70, −2.04).

BPS was associated with an increase in FT4 (%Δ = −9.63; 95% CI = −18.10, −0.33), and a marginal decrease in TSH (%Δ = 26.02; 95% CI = −3.53, 64.63) at <15 weeks GA, indicating a potential window of vulnerability during early pregnancy. TCS and TCB showed no significant associations with any thyroid hormone in MLR models stratified by GA.

Associations between parabens and thyroid hormones also varied by gestational age. EPB was not associated with any thyroid hormones, except for a marginal 4% decrease in the T3/T4 ratio at 15–21 GA weeks (%Δ = −4.29; 95% CI = −9.24, 0.65). Later time points in pregnancy may be a vulnerable time point for associations with BPB, given that BPB was associated with 6–7% decreases in T3 at 15–21 and >30 weeks GA, 5–6% decreases in the T3/T4 ratio at 15–21 and >30 weeks GA, and a 14.7% increase in TSH at >30 weeks GA. In contrast, MPB and PPB were associated with changes in thyroid hormones during early pregnancy. An IQR increase in PPB was associated with 5–6% decreases in FT4 at <15 weeks and 15–21 weeks GA [(%Δ = −4.60; 95% CI = −8.88, −0.12), (%Δ = −5.57; 95% CI = −10.74, −0.10), respectively]. At <15 weeks GA, an IQR increase in MPB was associated with a 4.2% decrease in FT4 (95% CI: −8.84, 0.69), a 3.7% increase in T3 (%Δ = 3.67; 95% CI = −0.33, 7.67), and a 2.7% increase in T3/T4 ratio (%Δ = 2.65; 95% CI = 0.09, 5.21). MPB was also associated with a marginal 7.0% decrease in TSH at 21–30 weeks GA (%Δ = −6.98; 95% CI = −13.91, 0.51). In a sensitivity analysis conducted only among term births only, most of the results remained consistent, with the exception of the associations involving TCS and TCB with T3 and T4 which were no longer statistically significant Supplemental Table 2.

4. Discussion

In the present study, phenols and parabens were associated with changes in maternal thyroid hormone levels during pregnancy. In particular, T3 was most strongly and consistently related to phenols and parabens as compared to the other studied thyroid hormones in our analysis. In general, BP-3, TCS, TCB, and BPB were associated with a decrease in T3, while MPB were associated with an increase in T3.

There was a general positive association between BPS, BP-3, TCS and BPB in relation to TSH, and a negative association between TCB in relation to TSH. Few associations between the urinary biomarkers and FT4 or T4 were observed, with the exception of MPB, PPB and BPS which were negatively associated with FT4 at <21 weeks GA, and the negative association between BP-3 and T4 at <30 weeks GA. Windows of vulnerability were identified. BPS, MPB and PPB were associated with thyroid hormone at earlier time points in pregnancy, whereas BPB was associated with thyroid hormone later in pregnancy.

An IQR increase in 2,5-DCP was associated with a suggestive 9% decrease in TSH at 15–21 weeks GA, and a 10% increase in TSH at >30 weeks GA. 2,4-DCP was associated with increases in T3/T4 ratio at 15–21 weeks GA and TSH at 21–30 weeks GA, and a decrease in T3 at 21–30 weeks GA. Few studies have looked into the effect of either phenol on thyroid hormones, and it is unclear why the associations between the dichlorophenols change direction from one time point to the next. No associations were observed between 2,4-DCP or 2,5-DCP and thyroid hormones in our previous small cohort study in Puerto Rico (Aker et al., 2016). 2,5-DCP was associated with increased TSH and hypothyroidism in a subsample of adolescents in NHANES, and negatively associated with FT4 among a large Belgian adolescent population (Croes et al., 2015; Wei and Zhu, 2016), while chlorophenols (including 2,5-DCP) were found to interfere with the T4 binding site of a T4 carrier in an in vitro study (van den Berg, 1990).

In the present study, there were consistent negative associations between BP-3 with T4 and T3, and positive associations with TSH. Given the concurrent negative associations between BP-3 and bound T4 and T3 hormones, it is possible that BP-3 could be reducing the thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG) level (Glinoer, 1997). The lower levels in T4 and T3 alongside the elevated level of TSH in association with BP-3 could also indicate a situation of slight hypothyroidism, stimulating an increase in TSH. While BP-3 has shown anti-estrogenic and anti-androgenic effects in vitro (Kunz and Fent, 2006), and caused cytotoxicity in yeast cells and developmental disorders in zebrafish (Balázs et al., 2016), few studies have studied the effect of BP-3 on thyroid hormones, and study designs, hormones measured, and results have varied. Our previous study of a smaller pregnancy cohort in Puerto Rico found a significant negative association of BP-3 and free T3, but no significant associations with TSH (Aker et al., 2016). After topical application of sunscreen containing BP-3, there were small changes in thyroid hormone levels in young men (n=15) and older women (n=17) after two weeks, but the authors concluded that this was a chance finding, and attributed no effect of sunscreen on thyroid hormone levels (N. r. Janjua et al., 2007).

BPS, which is used as a replacement chemical for BPA, was associated with a suggestive increase in TSH, particularly <15 weeks GA, as well as a decrease in FT4 at <15 weeks GA. BPS was observed to induce uterine growth in rats (Rattan et al., 2017), affect the feedback regulatory circuits in parental zebrafish hypothalamo-pituitary-gonadal axes, impair the development of offspring (Ji et al., 2013), and possibly play a role in gene expression on the reproductive neuroendocrine axis in zebrafish (Qiu et al., 2016). The parallel associations observed between BPS and TSH, and BPS and FT4 could be indicative of a change in the feedback regulatory circuits similar to the effects observed in zebrafish (Ji et al., 2013). However, no previous human studies were identified that have investigated the effect of BPS on thyroid hormones. In the same LifeCodes cohort, BPA was associated with a decrease in TSH and an increase in FT4, particularly at later time points in pregnancy (Aung et al., 2017). While BPS was also associated with TSH and FT4, the associations were in the opposite direction. BPA and BPS were not correlated in this study (Spearman correlation = 0.24), and structural variations among bisphenols may be sufficient to alter receptor-binding affinities (Sartain and Hunt, 2016). This structural variation partly explains the differences observed in our results; however, the mechanism of action leading to the opposite directions in hormone associations is unclear. Furthermore, our detection level for BPS is very low (<25%), which may potentially introduce some bias to our results. This makes the associations between BPS and BPA a little more difficult to interpret.

The impact of TCS on thyroid hormones has been the most commonly researched in the literature, primarily in animal studies. TCS is structurally similar to thyroid hormones (Ruszkiewicz et al., 2017), and a study in pregnant rats showed that the greatest accumulation of TCS was in the placenta as compared to six other rat tissues, indicating pregnancy may be a sensitive time period for TCS exposure (Feng et al., 2016). In this study, LMMs provided statistical power to observe a negative association between TCS and T3, and a positive association with TSH. This association with T3 is consistent with animal studies that also showed linear decreases in T3 with increased exposure to TCS (Ruszkiewicz et al., 2017), including in pregnant rats (Rodríguez and Sanchez, 2010) and pregnant mice (Wang et al., 2015). A study in pregnant mice observed an effect of TCS on signal pathways involved in placental growth through the activation of thyroid hormone receptors that trigger this signaling pathway (Cao et al., 2017). On the other hand, no previous studies have reported an association between TCS and TSH during pregnancy in humans (Aker et al., 2016), or in animals (Paul et al., 2012; Zorrilla et al., 2009). However, if TCS was indeed responsible for the decrease in T3, it would make biological sense that TSH levels would increase given the negative feedback loop. A short-term (n=12) and long-term (n=132) study of adult men and women found no effects on thyroid hormone levels following exposure to TCS-containing toothpaste (Allmyr et al., 2009; Cullinan et al., 2012). Other studies point to a decrease in T4 levels in relation to TCS exposure, including animal dams (Axelstad et al., 2013; Crofton et al., 2007; Johnson et al., 2016; Paul et al., 2010a, 2010b, 2013; Rodríguez and Sanchez, 2010; Wang et al., 2015; Zorrilla et al., 2009). In the present study we found a negative but not statistically significant association between TCS and T4 (%Δ = −1.04%; 95% CI = −2.55, 0.49; p value = 0.18).

We found numerous associations between urinary paraben concentrations and hormone levels in the present study, and the associations differed by gestational age. MPB was positively associated with T3 and T4 at <15 weeks GA, PPB was associated with a decrease in FT4 at <15 weeks GA, EPB was associated with a marginal decrease in the T3/T4 ratio at 15–21 weeks GA, and BPB was associated with a decrease in T3, T3/T4 ratio, and an increase in TSH during the second half of gestation. Few studies have looked into the effect of parabens on thyroid hormones in pregnant women. In our previous cohort study of pregnant women in Puerto Rico, BPB was positively associated with FT4 during pregnancy, which we did not observe in the present study (Aker et al., 2016). In the earlier study, MPB was positively associated with FT4 early in pregnancy, and negatively associated with FT4 later in pregnancy (Aker et al., 2016). In the present study MPB was negatively associated with FT4 earlier in pregnancy, and non-significant with FT4 later in pregnancy. This could indicate that impacts on thyroid signaling in relation to exposure to parabens is dependent on the timing of the exposure, although chance findings cannot be ruled out. In other research, a study on NHANES women over the age of 20 reported that all measured parabens were negatively associated with FT4, and BPB and EPB were negatively associated with T4 (Koeppe et al., 2013). Vo et al., 2010 found that MPB and PPB significantly decreased T4 levels in prepubertal female rats. However, two small human studies in men found no effect on thyroid hormones (N. R. Janjua et al., 2007; Meeker et al., 2011). It is unclear why the associations with hormones between parabens varied to this extent. This could be explained by the higher levels of MPB and PPB in our study, the differences in paraben concentrations by study visit, or true differences in the associations due to the structural differences between the parabens.

Our study had a few limitations. Even though we applied sampling weights in our analyses to account for the case-control study design, there may still be constraints to the generalizability of our results to other populations given our sampling methods. Additionally, our study population had older maternal ages, and high educational attainment as compared to the general public, which could reduce the generalizability of our results. Loss to follow up may introduce selection bias, although the sample size at study visit 4 was still relatively high as compared to the study population at study visit 1. Although our study design greatly improved upon the standard cross-sectional design by measuring urinary biomarkers at four separate time points, variation of phenols and parabens is relatively high, and the four time points may not be sufficient to eliminate potential bias stemming from random measurement error. Another limitation was the lack of data on iodine status of the women, given that deficiencies in these minerals could affect thyroid hormone function. However, controlling for iodine status could lead to bias, given that iodine may act as mechanistic intermediate between the exposure and thyroid hormone (Rousset, 1981). Further, iodine had no impact on the associations between phenols/parabens and thyroid hormones in our previous study of NHANES data (Koeppe et al., 2013). We also did not measure thyroperoxidase antibodies and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG). Thyroperoxidase antibodies may influence thyroid function in pregnancy (van den Boogaard et al., 2011), and hCG has similar homology to TSH, and may affect maternal thyroid function in pregnancy (Tingi et al., 2016). Finally, given the exploratory nature of the study, many comparisons were made, increasing the chance of Type I error.

Our study also had many strengths, including a robust sample size, sensitive and state-of-the-art biomarkers of exposure, and the collection of data at four time points during pregnancy to account for the chemicals’ short lifespan in the body, and the varying levels of thyroid hormones throughout pregnancy. The repeated measures allow us to control for intra-individual variability and increase statistical power, as well as explore potential windows of susceptibility for these associations.

5. Conclusion

Our results provide suggestive human evidence for associations between phenols and parabens with thyroid hormones during pregnancy. The strength of our associations may vary across pregnancy. Further studies are required to confirm our findings, determine the biological mechanisms involved, and better understand if and how these hormone changes may affect downstream maternal and infant health outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Phenol and paraben urinary biomarker concentrations were measured at four time points in pregnant women

Phenol and paraben urinary biomarker concentrations were associated with changes in thyroid hormone levels across women, particularly triiodothyronine

Some differences in the associations were observed across time points in pregnancy

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source: Subject recruitment and sample collection was originally funded by Abbott Diagnostics. Funding was also provided by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (Grant Numbers: R01ES018872, P42ES017198, P50ES026049, UG3OD023251), and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) (Grant Number: U2CES026553), and the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (Grant Number: U2CES026553). The funding sources had no involvement in the study design, collection, analysis & interpretation of data or writing of the report.

We thank K. Kneen, S. Clipper, G. Pace, D. Weller, and J. Bell of NSF International in Ann Arbor, Michigan, for the urine biomarker analysis, and D. McConnell of the CLASS Lab at University of Michigan for assistance in hormone analysis.

Footnotes

Competing Financial Interests: The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aker AM, Watkins DJ, Johns LE, Ferguson KK, Soldin OP, Anzalota Del Toro LV, Alshawabkeh AN, Cordero JF, Meeker JD. Phenols and parabens in relation to reproductive and thyroid hormones in pregnant women. Environ Res. 2016;151:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2016.07.002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alemu A, Terefe B, Abebe M, Biadgo B. Thyroid hormone dysfunction during pregnancy: A review. Int J Reprod Biomed. 2016;14:677–686. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allmyr M, Panagiotidis G, Sparve E, Diczfalusy U, Sandborgh-Englund G. Human exposure to triclosan via toothpaste does not change CYP3A4 activity or plasma concentrations of thyroid hormones. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2009;105:339–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2009.00455.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-7843.2009.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrianou XD, Gängler S, Piciu A, Charisiadis P, Zira C, Aristidou K, Piciu D, Hauser R, Makris KC. Human Exposures to Bisphenol A, Bisphenol F and Chlorinated Bisphenol A Derivatives and Thyroid Function. PLOS ONE. 2016;11:e0155237. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155237. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0155237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aung MT, Johns LE, Ferguson KK, Mukherjee B, McElrath TF, Meeker JD. Thyroid hormone parameters during pregnancy in relation to urinary bisphenol A concentrations: A repeated measures study. Environ Int. 2017;104:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2017.04.001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2017.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelstad M, Boberg J, Vinggaard AM, Christiansen S, Hass U. Triclosan exposure reduces thyroxine levels in pregnant and lactating rat dams and in directly exposed offspring. Food Chem Toxicol Int J Publ Br Ind Biol Res Assoc. 2013;59:534–540. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2013.06.050. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2013.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balázs A, Krifaton C, Orosz I, Szoboszlay S, Kovács R, Csenki Z, Urbányi B, Kriszt B. Hormonal activity, cytotoxicity and developmental toxicity of UV filters. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2016;131:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2016.04.037. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2016.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun JM. Early-life exposure to EDCs: role in childhood obesity and neurodevelopment. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2017;13:161–173. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2016.186. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2016.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun JM, Just AC, Williams PL, Smith KW, Calafat AM, Hauser R. Personal care product use and urinary phthalate metabolite and paraben concentrations during pregnancy among women from a fertility clinic. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2014;24:459–466. doi: 10.1038/jes.2013.69. https://doi.org/10.1038/jes.2013.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley JP, Herring AH, Wolff MS, Calafat AM, Engel SM. Prenatal exposure to environmental phenols and childhood fat mass in the Mount Sinai Children’s Environmental Health Study. Environ Int. 2016;91:350–356. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2016.03.019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2016.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Hua X, Wang X, Chen L. Exposure of pregnant mice to triclosan impairs placental development and nutrient transport. Sci Rep. 2017;7:44803. doi: 10.1038/srep44803. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep44803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fourth National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals, Updated Tables, January 2017. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); Atlanta, GA: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chen LM, Du WJ, Dai J, Zhang Q, Si GX, Yang H, Ye EL, Chen QS, Yu LC, Zhang C, Lu XM. Effects of subclinical hypothyroidism on maternal and perinatal outcomes during pregnancy: a single-center cohort study of a Chinese population. PloS One. 2014;9:e109364. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109364. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0109364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croes K, Den Hond E, Bruckers L, Govarts E, Schoeters G, Covaci A, Loots I, Morrens B, Nelen V, Sioen I, Van Larebeke N, Baeyens W. Endocrine actions of pesticides measured in the Flemish environment and health studies (FLEHS I and II) Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2015;22:14589–14599. doi: 10.1007/s11356-014-3437-z. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-014-3437-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crofton KM, Paul KB, Devito MJ, Hedge JM. Short-term in vivo exposure to the water contaminant triclosan: Evidence for disruption of thyroxine. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2007;24:194–197. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2007.04.008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.etap.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullinan MP, Palmer JE, Carle AD, West MJ, Seymour GJ. Long term use of triclosan toothpaste and thyroid function. Sci Total Environ. 2012;416:75–79. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.11.063. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.11.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Den Hond E, Tournaye H, De Sutter P, Ombelet W, Baeyens W, Covaci A, Cox B, Nawrot TS, Van Larebeke N, D’Hooghe T. Human exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals and fertility: A case-control study in male subfertility patients. Environ Int. 2015;84:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2015.07.017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2015.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egeghy PP, Judson R, Gangwal S, Mosher S, Smith D, Vail J, Cohen Hubal EA. The exposure data landscape for manufactured chemicals. Sci Total Environ. 2012;414:159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.10.046. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, Zhang P, Zhang Z, Shi J, Jiao Z, Shao B. Endocrine Disrupting Effects of Triclosan on the Placenta in Pregnant Rats. PloS One. 2016;11:e0154758. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154758. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0154758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson KK, McElrath TF, Chen YH, Mukherjee B, Meeker JD. Urinary phthalate metabolites and biomarkers of oxidative stress in pregnant women: a repeated measures analysis. Environ Health Perspect. 2015;123:210–216. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1307996. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1307996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson KK, McElrath TF, Ko YA, Mukherjee B, Meeker JD. Variability in urinary phthalate metabolite levels across pregnancy and sensitive windows of exposure for the risk of preterm birth. Environ Int. 2014;70:118–124. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2014.05.016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2014.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forhead AJ, Fowden AL. Thyroid hormones in fetal growth and prepartum maturation. J Endocrinol. 2014;221:R87–R103. doi: 10.1530/JOE-14-0025. https://doi.org/10.1530/JOE-14-0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glinoer D. The regulation of thyroid function in pregnancy: pathways of endocrine adaptation from physiology to pathology. Endocr Rev. 1997;18:404–433. doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.3.0300. https://doi.org/10.1210/edrv.18.3.0300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guignard D, Gayrard V, Lacroix MZ, Puel S, Picard-Hagen N, Viguié C. Evidence for bisphenol A-induced disruption of maternal thyroid homeostasis in the pregnant ewe at low level representative of human exposure. Chemosphere. 2017;182:458–467. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.05.028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Kannan K. A survey of phthalates and parabens in personal care products from the United States and its implications for human exposure. Environ Sci Technol. 2013;47:14442–14449. doi: 10.1021/es4042034. https://doi.org/10.1021/es4042034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornung RW, Reed LD. Estimation of Average Concentration in the Presence of Nondetectable Values. Appl Occup Environ Hyg. 1990;5:46–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047322X.1990.10389587. [Google Scholar]

- Janjua Nr, Kongshoj B, Petersen Jh, Wulf Hc. Sunscreens and thyroid function in humans after short-term whole-body topical application: a single-blinded study. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:1080–1082. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.07803.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.07803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janjua NR, Mortensen GK, Andersson AM, Kongshoj B, Skakkebaek NE, Wulf HC. Systemic uptake of diethyl phthalate, dibutyl phthalate, and butyl paraben following whole-body topical application and reproductive and thyroid hormone levels in humans. Environ Sci Technol. 2007;41:5564–5570. doi: 10.1021/es0628755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji K, Hong S, Kho Y, Choi K. Effects of bisphenol s exposure on endocrine functions and reproduction of zebrafish. Environ Sci Technol. 2013;47:8793–8800. doi: 10.1021/es400329t. https://doi.org/10.1021/es400329t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns LE, Ferguson KK, McElrath TF, Mukherjee B, Meeker JD. Associations between Repeated Measures of Maternal Urinary Phthalate Metabolites and Thyroid Hormone Parameters during Pregnancy. Environ Health Perspect. 2016:124. doi: 10.1289/EHP170. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Johns LE, Ferguson KK, McElrath TF, Mukherjee B, Seely EW, Meeker JD. Longitudinal Profiles of Thyroid Hormone Parameters in Pregnancy and Associations with Preterm Birth. PLOS ONE. 2017;12:e0169542. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169542. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PI, Koustas E, Vesterinen HM, Sutton P, Atchley DS, Kim AN, Campbell M, Donald JM, Sen S, Bero L, Zeise L, Woodruff TJ. Application of the Navigation Guide systematic review methodology to the evidence for developmental and reproductive toxicity of triclosan. Environ Int. 2016;92–93:716–728. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2016.03.009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Sujin, Kim Sunmi, Won S, Choi K. Considering common sources of exposure in association studies - Urinary benzophenone-3 and DEHP metabolites are associated with altered thyroid hormone balance in the NHANES 2007–2008. Environ Int. 2017;107:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2017.06.013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2017.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeppe ES, Ferguson KK, Colacino JA, Meeker JD. Relationship between urinary triclosan and paraben concentrations and serum thyroid measures in NHANES 2007–2008. Sci Total Environ. 2013;445–446:299–305. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.12.052. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.12.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunz PY, Fent K. Multiple hormonal activities of UV filters and comparison of in vivo and in vitro estrogenic activity of ethyl-4-aminobenzoate in fish. Aquat Toxicol. 2006;79:305–324. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2006.06.016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquatox.2006.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang C, Fisher M, Neisa A, MacKinnon L, Kuchta S, MacPherson S, Probert A, Arbuckle TE. Personal Care Product Use in Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period: Implications for Exposure Assessment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13:105. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13010105. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13010105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Kim C, Youn H, Choi K. Thyroid hormone disrupting potentials of bisphenol A and its analogues - in vitro comparison study employing rat pituitary (GH3) and thyroid follicular (FRTL-5) cells. Toxicol Vitro Int J Publ Assoc BIBRA. 2017;40:297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2017.02.004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tiv.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis RC, Meeker JD, Peterson KE, Lee JM, Pace GG, Cantoral A, Téllez-Rojo MM. Predictors of urinary bisphenol A and phthalate metabolite concentrations in Mexican children. Chemosphere. 2013;93:2390–2398. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.08.038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.08.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastorakos G, Karoutsou EI, Mizamtsidi M, Creatsas G. The menace of endocrine disruptors on thyroid hormone physiology and their impact on intrauterine development. Endocrine. 2007;31:219–237. doi: 10.1007/s12020-007-0030-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElrath TF, Lim KH, Pare E, Rich-Edwards J, Pucci D, Troisi R, Parry S. Longitudinal evaluation of predictive value for preeclampsia of circulating angiogenic factors through pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207:407.e1–407.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.08.010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2012.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead MN. Children’s Health: Mother’s Thyroid, Baby’s Health. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112:A612. doi: 10.1289/ehp.112-a612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeker JD, Yang T, Ye X, Calafat AM, Hauser R. Urinary concentrations of parabens and serum hormone levels, semen quality parameters, and sperm DNA damage. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119:252–257. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002238. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1002238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien KM, Upson K, Cook NR, Weinberg CR. Environmental Chemicals in Urine and Blood: Improving Methods for Creatinine and Lipid Adjustment. Environ Health Perspect. 2016;124:220–227. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1509693. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1509693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul KB, Hedge JM, Bansal R, Zoeller RT, Peter R, DeVito MJ, Crofton KM. Developmental triclosan exposure decreases maternal, fetal, and early neonatal thyroxine: a dynamic and kinetic evaluation of a putative mode-of-action. Toxicology. 2012;300:31–45. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2012.05.023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tox.2012.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul KB, Hedge JM, Devito MJ, Crofton KM. Developmental triclosan exposure decreases maternal and neonatal thyroxine in rats. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2010a;29:2840–2844. doi: 10.1002/etc.339. https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul KB, Hedge JM, DeVito MJ, Crofton KM. Short-term exposure to triclosan decreases thyroxine in vivo via upregulation of hepatic catabolism in Young Long-Evans rats. Toxicol Sci Off J Soc Toxicol. 2010b;113:367–379. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfp271. https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfp271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul KB, Thompson JT, Simmons SO, Vanden Heuvel JP, Crofton KM. Evidence for triclosan-induced activation of human and rodent xenobiotic nuclear receptors. Toxicol In Vitro. 2013;27:2049–2060. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2013.07.008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tiv.2013.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippat C, Mortamais M, Chevrier C, Petit C, Calafat AM, Ye X, Silva MJ, Brambilla C, Pin I, Charles MA, Cordier S, Slama R. Exposure to phthalates and phenols during pregnancy and offspring size at birth. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120:464–470. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1103634. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1103634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu W, Zhao Y, Yang M, Farajzadeh M, Pan C, Wayne NL. Actions of Bisphenol A and Bisphenol S on the Reproductive Neuroendocrine System During Early Development in Zebrafish. Endocrinology. 2016;157:636–647. doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1785. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2015-1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattan S, Zhou C, Chiang C, Mahalingam S, Brehm E, Flaws J. Exposure to endocrine disruptors during adulthood: consequences for female fertility. J Endocrinol. 2017 doi: 10.1530/JOE-17-0023. https://doi.org/10.1530/JOE-17-0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Richardson DB, Rzehak P, Klenk J, Weiland SK. Analyses of Case-Control Data for Additional Outcomes. Epidemiology. 2007;18:441–445. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318060d25c. https://doi.org/10.2307/20486400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochester JR, Bolden AL. Bisphenol S and F: A Systematic Review and Comparison of the Hormonal Activity of Bisphenol A Substitutes. Environ Health Perspect. 2015;123:643–650. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1408989. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1408989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez PEA, Sanchez MS. Maternal exposure to triclosan impairs thyroid homeostasis and female pubertal development in Wistar rat offspring. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2010;73:1678–1688. doi: 10.1080/15287394.2010.516241. https://doi.org/10.1080/15287394.2010.516241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousset B. Antithyroid effect of a food or drug preservative: 4-hydroxybenzoic acid methyl ester. Experientia. 1981;37:177–178. doi: 10.1007/BF01963218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruszkiewicz JA, Li S, Rodriguez MB, Aschner M. Is Triclosan a neurotoxic agent? J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 2017;20:104–117. doi: 10.1080/10937404.2017.1281181. https://doi.org/10.1080/10937404.2017.1281181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saki F, Dabbaghmanesh MH, Ghaemi SZ, Forouhari S, Ranjbar Omrani G, Bakhshayeshkaram M. Thyroid function in pregnancy and its influences on maternal and fetal outcomes. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2014;12:e19378. doi: 10.5812/ijem.19378. https://doi.org/10.5812/ijem.19378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartain CV, Hunt PA. An old culprit but a new story: bisphenol A and “NextGen” bisphenols. Fertil Steril. 2016;106:820–826. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.07.1114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.07.1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang R, Chen M-J, Ding G-D, Chen X-J, Han X-M, Zhou K, Chen L-M, Xia Y-K, Tian Y, Wang X-R. Associations of prenatal exposure to phenols with birth outcomes. Environ Pollut Barking Essex. 2013;1987–178:115–120. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2013.03.023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2013.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tingi E, Syed AA, Kyriacou A, Mastorakos G, Kyriacou A. Benign thyroid disease in pregnancy: A state of the art review. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2016;6:37–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jcte.2016.11.001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcte.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg KJ. Interaction of chlorinated phenols with thyroxine binding sites of human transthyretin, albumin and thyroid binding globulin. Chem Biol Interact. 1990;76:63–75. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(90)90034-k. https://doi.org/10.1016/0009-2797(90)90034-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Boogaard E, Vissenberg R, Land JA, van Wely M, van der Post JAM, Goddijn M, Bisschop PH. Significance of (sub)clinical thyroid dysfunction and thyroid autoimmunity before conception and in early pregnancy: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17:605–619. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmr024. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmr024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vélez MP, Arbuckle TE, Fraser WD. Female exposure to phenols and phthalates and time to pregnancy: the Maternal-Infant Research on Environmental Chemicals (MIREC) Study. Fertil Steril. 2015;103:1011–1020e2. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.01.005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vo TTB, Yoo YM, Choi KC, Jeung EB. Potential estrogenic effect(s) of parabens at the prepubertal stage of a postnatal female rat model. Reprod Toxicol Elmsford N. 2010;29:306–316. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2010.01.013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reprotox.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Ding Z, Shi QM, Ge X, Wang HX, Li MX, Chen G, Wang Q, Ju Q, Zhang JP, Zhang MR, Xu LC. Anti-androgenic mechanisms of Bisphenol A involve androgen receptor signaling pathway. Toxicology. 2017;387:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2017.06.007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tox.2017.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Chen X, Feng X, Chang F, Chen M, Xia Y, Chen L. Triclosan causes spontaneous abortion accompanied by decline of estrogen sulfotransferase activity in humans and mice. Sci Rep. 2015;5:18252. doi: 10.1038/srep18252. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep18252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Ouyang F, Feng L, Wang Xia, Liu Z, Zhang J. Maternal Urinary Triclosan Concentration in Relation to Maternal and Neonatal Thyroid Hormone Levels: A Prospective Study. Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125:067017. doi: 10.1289/EHP500. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins DJ, Ferguson KK, Anzalota Del Toro LV, Alshawabkeh AN, Cordero JF, Meeker JD. Associations between urinary phenol and paraben concentrations and markers of oxidative stress and inflammation among pregnant women in Puerto Rico. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2015;218:212–219. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2014.11.001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheh.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y, Zhu J. Para-Dichlorobenzene Exposure Is Associated with Thyroid Dysfunction in US Adolescents. J Pediatr. 2016;177:238–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.06.085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.06.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams GR. Neurodevelopmental and Neurophysiological Actions of Thyroid Hormone. J Neuroendocrinol. 2008;20:784–794. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01733.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witorsch RJ. Critical analysis of endocrine disruptive activity of triclosan and its relevance to human exposure through the use of personal care products. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2014;44:535–555. doi: 10.3109/10408444.2014.910754. https://doi.org/10.3109/10408444.2014.910754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff MS, Teitelbaum SL, McGovern K, Pinney SM, Windham GC, Galvez M, Pajak A, Rybak M, Calafat AM, Kushi LH, Biro FM. Breast Cancer and Environment Research Program. Environ Int. 84:174–180. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2015.08.008. Electronic address: http://www.bcerp.org/index.htm 2015 Environmental phenols and pubertal development in girls. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye X, Kuklenyik Z, Bishop AM, Needham LL, Calafat AM. Quantification of the urinary concentrations of parabens in humans by on-line solid phase extraction-high performance liquid chromatography-isotope dilution tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2006;844:53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.06.037. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye X, Kuklenyik Z, Needham LL, Calafat AM. Quantification of urinary conjugates of bisphenol A, 2,5-dichlorophenol, and 2-hydroxy-4-methoxybenzophenone in humans by online solid phase extraction-high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2005;383:638–644. doi: 10.1007/s00216-005-0019-4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-005-0019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang DH, Zhou EX, Yang ZL. Waterborne exposure to BPS causes thyroid endocrine disruption in zebrafish larvae. PloS One. 2017;12:e0176927. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176927. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0176927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoeller TR, Dowling ALS, Herzig CTA, Iannacone EA, Gauger KJ, Bansal R. Thyroid hormone, brain development, and the environment. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110(Suppl 3):355–361. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110s3355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorrilla LM, Gibson EK, Jeffay SC, Crofton KM, Setzer WR, Cooper RL, Stoker TE. The effects of triclosan on puberty and thyroid hormones in male Wistar rats. Toxicol Sci Off J Soc Toxicol. 2009;107:56–64. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn225. https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfn225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.