Abstract

Acute kidney injury (AKI) arising from diverse etiologies is characterized by mitochondrial dysfunction. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator-1alpha (PGC1α), a master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis, has been shown to be protective in AKI. Interestingly, reduction of PGC1α has also been implicated in the development of diabetic kidney disease and renal fibrosis. The beneficial renal effects of PGC1α make it a prime target for therapeutics aimed at ameliorating AKI, forms of chronic kidney disease (CKD), and their intersection. This review summarizes the current literature on the relationship between renal health and PGC1α and proposes areas of future interest.

Keywords: AKI, CKD, kidney, metabolism, PGC1α

INTRODUCTION

Among organs with the highest energy demands, the kidney is second only to the heart in mitochondrial abundance (54). The kidney requires a constant ATP supply to transport solutes against electrochemical gradients along the nephron. Mitochondria are densely localized to the renal tubular epithelium and are particularly abundant in the proximal tubule and medullary thick ascending limb of Henle (70), to aid in the critical functions of solute reabsorption and secretion. Mitochondria are the dynamic organelles responsible for energy production (ATP) in the cell via oxidative phosphorylation. The electron transport chain (ETC) pumps protons from the inner mitochondrial matrix to the intermembrane space, creating an electrochemical gradient across the inner mitochondrial membrane that powers the phosphorylation of ADP to ATP. The highly charged state of the inner membrane is prone to leakage of electrons along the ETC, becoming a source of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that can cause oxidative stress on the cell. Excess mitochondrial ROS production during ischemia or inflammation may accelerate injury in acute kidney injury (58, 77, 78).

Mitochondrial Injury and the Quality Control Cycle

Mitochondria form dynamic tubular networks, constantly undergoing fission and fusion to adapt to the ever-changing energy demands of the cell. Dynamin-related protein-1 (Drp1) mediates fission and translocates from the cytosol to the outer mitochondrial membrane, where it facilitates division of the mitochondrion into short rods or spheres. In fusion, the mitofusin proteins (Mfn1 and Mfn2) from the outer membrane interact with the inner membrane protein, optic atrophy 1 (Opa1), to produce elongated fusiform mitochondria (96). Fission may initiate autophagic degradation of defective mitochondria via mitophagy, promote apoptosis, and generate additional ROS (23). Fusion can enhance oxidative phosphorylation and mitigate the number of damaged mitochondria by combining their contents with healthy mitochondria through complementation (94). An intricate balance of these mitochondrial dynamics is necessary to maintain the mitochondrial network and overall organelle morphology and function. Dysregulation of mitochondrial dynamics has been implicated in neurodegenerative, cardiovascular, and genetic diseases (4).

Structural alterations in renal mitochondria have been observed in human and animal models of AKI. Electron microscopy of renal proximal tubule cells have revealed severe mitochondrial vacuolization and swelling with diffusely arranged cristae in septic (79, 80), ischemic (8, 55, 81), and toxin-mediated AKI (52, 99). Along with structural changes, diminished electron transport chain enzyme activity in the septic kidney confirms overall mitochondrial dysfunction (80).

Beyond overt changes in morphology, mitochondrial dynamics are also interrupted in the injured mitochondrion during AKI. Brooks et al. (8) observed mitochondrial fragmentation and Drp1 mobilization to the outer mitochondrial membrane in injured tubular cells. Drp1 activation recruited apoptogenic proteins such as Bax and Bak, leading to cytochrome c release and initiation of apoptosis. Utilizing dominant-negative mutants, RNA interference, and chemical inhibitors, the authors further demonstrated that Drp1 inhibition attenuated mitochondrial fragmentation, preserved mitochondrial integrity and function, and limited apoptosis following cisplatin or ischemic injury. In turn, kidney function was better preserved. Jiang et al. (36) showed that rapamycin treatment in mice enhanced mitophagy and ameliorated cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Conversely, pharmacological inhibition or genetic deletion of autophagy-related genes worsened renal injury. These and other studies suggest that excessive fission during AKI is deleterious to organ function, whereas safe clearance of damaged mitochondria via mitophagy may be protective (7, 32).

PGC1α Mechanisms in Mitochondrial Biogenesis and Quality Control

In conjunction with timely clearance of damaged mitochondria, generation of healthy mitochondrial mass may be important in recovery from AKI. PGC1α has emerged as a key regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis. PGC1α also has critical roles in essential metabolic processes such as fatty acid oxidation, oxidative phosphorylation, and ROS detoxification (61, 87, 92). The PGC-1 family of proteins includes PGC1α, PGC1β, and PGC-1 related coactivator. These proteins share functional overlap in non-kidney cells due to similarities in protein structure (44, 45). PGC1α has been the most extensively studied in renal cells and mammalian kidneys, with several isoforms identified from promoter and alternative splicing studies conducted in studies of skeletal muscle (14, 44, 45, 50, 66).

PGC1α was discovered by Spiegelman’s group (61) as a cold-inducible regulator of adaptive thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue. This group quickly thereafter demonstrated PGC1α’s role in mitochondrial biogenesis by activation of the transcription factor NRF-1 leading to transcription of Tfam and genes encoding respiratory chain proteins (92). As a transcriptional cofactor, PGC1α expression can be induced by various external and physiological stimuli such as exercise (33), nutrient deprivation (65), hypoxia (2), cAMP activation (91), and oxidant stress (74). PGC1α is also subject to posttranslational modifications that alter its activity. For example, phosphorylation by AMPK or deacetylation by Sirt1 increases PGC1α action (10, 33). AMPK, Sirt1, and PGC1α monitor and respond to the energy requirements of the cell in a highly coordinated fashion (9). PGC1α acts as a cofactor for yin-yang 1 (YY1) to promote mitochondrial biogenesis. This interaction with YY1 is positively modulated by the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), suggesting this particular pathway is induced only when there are available nutrients to create energy stores (19). Genes encoding proteins for mitochondrial processes such as fatty acid oxidation are regulated by estrogen-related receptors (ERRs) and PPARα, both of which can be activated by PGC1α (31, 84).

Beyond mitochondrial biogenesis, there is also evidence PGC1α plays a role in mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy. Soriano et al. (72) demonstrated PGC1α-mediated coactivation of estrogen-related receptor α-induced Mfn2 in skeletal muscle and brown adipose tissue. Vainshtein et al. (82) demonstrated loss of PGC1α decreased exercise-induced autophagic flux and mitophagy in skeletal muscle of C57BL/6 mice via decreased transcription of autophagy-related genes. This group also found PGC1α knockout mice had decreased lipid transport to the lysosome compared with their wild-type littermates secondary to downregulation of exercise-induced increases in Niemann-Pick C1.

PGC1α in Cardiometabolic Processes

Abundant PGC1α is found in metabolically active organs including the brain, skeletal muscle, heart, and the kidney (61). In skeletal muscle, PGC1α has been shown to promote angiogenesis following ischemia by inducing vascular endothelial growth factor in a manner independent of the transcription factor HIF (hypoxia-inducible factor) (2). In a trauma-hemorrhage rat model, Hsieh et al. (29, 30) demonstrated that upregulation of PGC1α by estrogen promoted cardiac recovery whereas loss of PGC1α prevented it. PGC1α may exert cardioprotective angiogenic effects in the heart during the stress of pregnancy (56). Recently, Craige et al. (17) showed that PGC1α overexpression decreased angiotensin II-mediated hypertension via increased endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression. PGC1α has also been found to play a role in the homeostasis of other organ systems. Several lines of investigation propose a link to neurological disorders. For example, PGC1α overexpression mitigates experimental models of Parkinson’s disease (98), Huntington’s disease (18, 74, 88), and Alzheimer’s dementia (62).

In diabetes, PGC1α plays a complex role. PGC1α is involved in hepatic gluconeogenesis (60, 64). Thus PGC1α can worsen blood glucose (68). Overexpression of PGC1α in fetal pancreatic β-cells has been shown to decrease β-cell proliferation and function, which is not seen in isolated adult-onset PGC1α overexpression (83), leading to glucose intolerance. However, single-nucleotide polymorphisms influencing PGC1α expression may contribute to the development of type II diabetes mellitus (53), with overexpression of PGC1α perhaps protective in this case (46).

Renal Actions of PGC1α

In the kidney, PGC1α expression is localized to the cortex and outer stripe of the medulla, overlapping with regions of high mitochondrial activity (80). Given the relative abundance of mitochondria found in the kidney compared with other organs, it is perhaps of little surprise PGC1α is increasingly studied by the nephrology community. As damaged mitochondria are apparent in multiple forms of AKI, attention has focused on how PGC1α and mitochondrial biogenesis may promote recovery in the injured kidney. Several studies now demonstrate the key role PGC1α plays in mitigation of AKI, and there is increasing evidence that loss of PGC1α contributes to the development of renal fibrosis and subsequent CKD.

PGC1α in sepsis-associated AKI.

In a fluid-resuscitated endotoxemic model of sepsis, renal PGC1α levels corresponded to the severity of kidney dysfunction both at the nadir of kidney function and during functional recovery following volume expansion (80). Transcript levels of fatty acid oxidation and oxidative phosphorylation genes downstream of PGC1α were also proportionally suppressed relative to the severity of renal injury. This intimate relationship between kidney PGC1α expression and renal function was further confirmed in a complementary surgical model of polymicrobial sepsis. Applying the endotoxemic model to global and renal proximal tubule PGC1α knockout mice, loss of PGC1α exacerbated renal injury. Moreover, both the global and kidney-specific PGC1α-deficient mice sustained persistent renal impairment whereas their control counterparts recovered renal function following volume expansion. Together, these results suggested that renal PGC1α restoration may be necessary for functional recovery of the septic kidney.

Mechanistic studies by Smith et al. (71) have demonstrated a pathway by which lipopolysaccharide (LPS) leads to PGC1α suppression. The decrease in PGC1α and mitochondrial biogenesis in mice treated with intraperitoneal LPS was attenuated by both antibodies directed against toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway, thus suggesting that LPS stimulation of TLR4 leads to ERK activation and downstream PGC1α suppression seen in sepsis-related AKI. A preliminary study by Matejovic et al. (49) using a porcine model of sepsis found a possible genomic predisposition to AKI in sepsis. Pigs developing sepsis-related AKI had lower renal transcript levels of PGC1α, as well as lower cyclooxygenase-2 and angiotensin type II receptor, compared with those that did not develop AKI.

PGC1α in toxin-mediated AKI.

Reduced PGC1α levels have also been observed in the context of toxin-mediated AKI. Despite limited tubular necrosis, Portilla et al. (59) observed that PGC1α expression is diminished along the mouse proximal tubule and thick ascending limb within 24 h of cisplatin-induced AKI. In subsequent cellular studies, they found that cisplatin not only inhibits binding activity of transcription factors to the nuclear receptor (and PGC1α transcriptional partner) PPARα, but also downregulates PGC1α and fatty acid oxidation genes. In folate-induced nephrotoxicity, Ruiz-Andres et al. (67) found that the proinflammatory cytokine TWEAK suppressed PGC1α expression by histone deacetylation and activation of NF-κB signaling, providing other molecular targets to preserve PGC1α in the injured kidney. In nonrenal models, expression of PGC1α has been shown to be repressed by activators of NF-kB (12, 22, 27, 75, 76, 86).

As described above, PGC1α, AMPK, and sirtuin enzymes are tightly interconnected to modulate energy homeostasis. Morigi et al. (51) found that the mitochondrial-specific Sirt3 is suppressed in the kidneys of cisplatin-treated mice similar to PGC1α itself. Treatment with the AMP mimetic compound AICAR—which activates AMPK—attenuated renal injury and preserved PGC1α and Sirt3 levels. Conversely, Sirt3-deficient mice suffered worse kidney injury, which could not be ameliorated by AMPK activation. In vitro studies revealed that Sirt3 prevented Drp1-driven mitochondrial fragmentation and preserved mitochondrial integrity.

PGC1α in renal ischemia-reperfusion.

Renal ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI) disrupts mitochondrial homeostasis as evidenced by acquired defects in mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, the balance of mitochondrial fusion vs. fission, and the downregulation of PGC1α and its target transcription factors (24). Activation of pathways upstream of PGC1α has been shown to improve renal cellular health and renal function in models of IRI. For example, AICAR treatment attenuated nitrosative stress, tubular necrosis, and renal impairment in a rat IRI model (40). Analogously, treatment with the Sirt1 activator SRT1720 improved mitochondrial biogenesis and function in oxidant-stressed renal proximal tubule cells (24). Treatment with SIRT1720 was also shown to decrease renal injury scores, apoptosis, and serum creatinine when given intravenously to rats at the end of 60 min of bilateral renal ischemia (38). Further analysis of these samples revealed those treated with SIRT1720 had improved renal mitochondrial mass, ATP concentration, and PGC1α expression 24 h after reperfusion. Stimulation of Sirt1 via caloric restriction has also been shown to decrease IRI-induced AKI (41). Compared with control littermates, rats fed a 70% calorie-restricted diet for 2 wk before IRI have a smaller rise in serum creatinine, lower renal injury histopathology scores, enhanced Sirt1 induction, and attenuation of IRI-related decrease in PGC1α. The β-adrenergic agonist formoterol strongly induced mitochondrial biogenesis and protected against IRI, leading the team to hypothesize a renoprotective action for PGC1α (35). Collier et al. (15) found that inhibition of ERK1/2 with trametinib led to increased renal FOXO1 and PGC1α. In a mouse IRI model, pretreatment with trametinib before 18 min of bilateral IRI lessened the decrease in PGC1α and NRF1.

Studies directly testing PGC1α as a potential target in renal IRI reinforce the results obtained from the above upstream chemical activation studies. Rasbach and Schnellmann (63) demonstrated that PGC1α overexpression improved mitochondrial function and cell survival in culture models of oxidant injury. Recent work from our group applied both gain and loss of function strategies to study PGC1α in an organismic context. Tran et al. (81) found that PGC1a knockout mice suffered worse renal function and tubular injury, whereas tubule-specific PGC1a overexpressing transgenic mice exhibited less severe AKI, better renal perfusion, quicker restoration of renal function, increased survival, and less histological injury. To explore downstream effector mechanisms of PGC1α, RNAseq and metabolomic analyses of injured kidney tissue identified de novo NAD+ biosynthesis as the main mediator of PGC1α-dependent protection.

NAD+ is a critical cofactor involved in important cellular oxidation-reduction reactions in the Krebs cycle and oxidative metabolism. NAD+ levels are maintained by a balance between biosynthesis and consumption via cleavage enzymes. Three biosynthetic pathways include 1) the Preiss-Handler pathway from niacin, 2) de novo from amino acids including tryptophan, and 3) salvage from nicotinamide (Nam). Of these, NAD+ synthesis from Nam is considered the major mammalian source of NAD+ (16). Along with its role in redox reactions, NAD+ is cleaved to Nam and ADP-ribose by major cell-regulatory enzymes of different classes: sirtuins, poly(ADP ribose) polymerases (PARPs), and ectonucleotidases (85).

In our studies (81), NAD+ biosynthetic enzyme levels positively correlated with overall PGC1α expression. Injured mice had reduced levels of NAD+ and its precursor Nam, and decreased renal function compared with sham-operated controls. At baseline, PGC1α knockout exhibited lower renal levels of Nam and NAD+ than wild-type controls; following IRI, KO mice developed more severe renal function impairment. Conversely, tubule-specific PGC1α-overexpressing mice exhibited higher renal Nam and NAD+ levels at baseline and greater resistance to functional impairment after IRI. Remarkably, Nam supplementation in ischemic PGC1α-null mice was sufficient to augment renal NAD+ and normalize renal function. We also found Nam to be renoprotective when administered in wild-type mice after the onset of AKI and in a toxic AKI model. Notably, an independent study has validated this core finding by administering the direct biosynthetic product of Nam, NMN (nicotinamide mononucleotide), in mouse models of renal IRI and toxic AKI (25).

NAD+ itself is rate-limiting for oxidative metabolism (5, 6), so methods to defend its level in AKI should enhance energy metabolism. The fall in renal NAD+ associated with different kinds of AKI may relate both to decreased biosynthesis and increased consumption—e.g., via stress-activated PARPs. Nam may act as a PGC1α-mimetic by stimulating NAD+ biosynthesis chemically rather than transcriptionally. Consistent with a shared effect on NAD+ augmentation and improved energy metabolism between Nam and PGC1α, we found that either strategy reduced the accumulation of storage fats in the postischemic tubule and increased the level of renal β-hydroxybutyrate, a breakdown product of fatty acid oxidation, which in turn increased vasodilation by activating a G protein-coupled receptor that signals the secretion of prostaglandin E2. Indeed, blockade of either the hydroxybutyrate receptor or prostaglandin synthesis abrogated the renoprotection conferred by excess tubular PGC1α (81).

PGC1α and renal fibrosis.

PGC1α has been shown to be a key mediator in prevention of experimental renal fibrosis, contributing to excitement around its potential to target CKD. Kidney biopsy specimens derived from individuals with known CKD consistently demonstrate decreased PGC1α expression compared with healthy controls (37, 69, 81). To explore potential underlying mechanisms, Kang et al. (37) performed gene expression profiling on microdissected biopsy samples derived from a cohort of patients with CKD secondary to diabetes or hypertension, comparing those patients to controls without CKD. PGC1α-related fatty acid oxidation transcripts were found to be downregulated in those with CKD. This finding was further studied in a murine model of folate nephropathy where tubular epithelial cell PGC1α transcript levels were reduced and lipid accumulation increased in mice with nephropathy compared with control. They showed that the profibrotic cytokine, TGFβ-1, led to SMAD-3-dependent repression of PGC1α transcription in vitro (37). This study was followed up by Han and colleagues subsequently reported that proximal tubule expression of the AMPK regulator called protein liver kinase B1 (LKB1) helped defend PGC1a expression (27a). Recently, this group also found HES1, a downstream target of the potent regulator of kidney fibrosis, Notch1, directly binds to the PGC1α promoter region, negatively regulating its transcription (28). Additionally, overexpression of PGC1α in vitro or in an in vivo model of tubule-specific Notch1 overexpression decreased profibrotic gene expression and development of renal fibrosis, respectively.

PGC1α and diabetic kidney disease.

Comparing the urinary metabolome in individuals with diabetes both with and without kidney disease led Sharma’s group (69) to propose a role for renal PGC1α in diabetic kidney disease. They found decreased PGC1α mRNA expression in microdissected cortical tubulointerstitial samples in kidney biopsies from those with diabetic kidney disease vs. those with minimal change disease, supporting the argument that loss of renal PGC1α may be an important step in the pathogenesis of diabetic kidney disease.

Several studies have yielded evidence that PGC1α’s involvement in diabetic kidney disease may extend out of the tubule and into glomerular cells. Guo et al. (26) found that PGC1α overexpression decreased mesangial hypertrophy in a rat model of diabetic nephropathy, and Danesh’s group (47) has reported that the long noncoding RNA, Tug1—which enables PGC1α to bind its own promoter—is downregulated in the setting of hyperglycemic stress. Rescue with podocyte-restricted Tug1 overexpression prevented the mitochondrial changes associated with diabetic nephropathy and ameliorated the diabetic kidney phenotype. Although PGC1α’s renal expression is highest in the tubule (80), these results suggest that PGC1α may also mitigate forms of CKD through actions directly in the glomerulus.

Li and colleagues (43a) also found decreased PGC1α transcription and protein levels in the podocytes of microdissected biopsy samples from humans with known diabetic kidney disease as well as two different murine models of diabetic kidney disease. However, podocyte-specific inducible overexpression of PGC1α not only failed to improve outcomes in the murine models, but actually accelerated progression toward end-stage renal disease by inducing collapsing focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis, suggesting a critical window of PGC1α activity required for glomerular health.

PGC1α and uremic extrarenal manifestations.

Relatively less work has explored the role of PGC1α in the context of extrarenal manifestations of CKD or ESRD. One such study began with the premise that PGC1α may be a bellwether for general health. In their study of a cohort of peritoneal dialysis patients, Zaza et al. (95) found decreased PGC1α transcription in peripheral blood monocytes compared with healthy controls. Another study has proposed that fatty acid transport across the vascular endothelium may drive insulin resistance—a feature of progressive renal disease (73)—in a fashion modulated by PGC1α (34).

PGC1α as a drug target in AKI and CKD.

The preponderance of evidence points to loss of tubular PGC1α as a deleterious event in the kidney arising from different stimuli such as inflammatory and profibrotic cytokines. Conversely, enhanced PGC1α expression in the renal tubule has so far proven effective in models of AKI or fibrosis. Given the opportunity to mitigate AKI and CKD with a single target, PGC1α is a very attractive candidate for “kidney chemoprevention.” Indeed, the search for druglike molecules that can modulate PGC1α’s function is, itself, an area of active investigation (3, 97). The exact mechanisms of PGC1α’s protective effects in AKI are not yet fully elucidated. Additionally, no untoward short-term renal effects of increasing PGC1α have thus far been reported. Thus the short-term use of an agent to increase PGC1α expression or action may be a promising approach to prevent AKI in the setting of insults such as suprarenal vascular surgery, cardiothoracic surgery requiring cardiopulmonary bypass, or early in the setting of septic shock.

What is less certain is the feasibility of long-term metabolic therapy for the prevention of chronic kidney disease development. First, little is known about long-term effects of systemic PGC1α upregulation in humans. In mice, in addition to possible development of focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis, it appears that unchecked cardiac PGC1α overexpression may actually be detrimental as such animals develop a dilated cardiomyopathy (39) and suffer decreased tolerance to ischemia (48). Second, although PGC1α’s location downstream of the intensively investigated drug targets, AMPK and sirtuins, should make it somewhat more specific, PGC1α itself has a multitude of downstream targets with varied functional consequences. For example, PGC1α in the skeletal muscle promotes angiogenesis after ischemia, an effect thus far not observed in the kidney and perhaps undesirable in a chronic context (2, 81). Additionally, it has been shown that inhibition of mTOR with rapamycin can decrease renal fibrosis in a KIM-1 overexpression model of CKD in zebrafish and mice (93). Although this study highlights the potential role of autophagy and mitophagy in the prevention of renal fibrosis and CKD, it also calls into question the salutary effects of PGC1α on CKD, as rapamycin would similarly inhibit the mitochondrial biogenesis derived from the mTOR-PGC1α-YY1 axis. Given these unknowns, further defining the critical salutary pathways downstream of PGC1α may offer therapeutic possibilities with better safety profiles. Our study linking PGC1α renal action to NAD+ biosynthesis may be one such example (81).

Another example may come from PGC1α’s effect on PPARα. Portilla’s group (42, 43) demonstrated striking renoprotection against AKI and CKD with PPARα overexpression in the tubule. Aquilano et al. (1) have demonstrated that the lipid accumulation and increased oxidative stress found in sarcopenia is secondary to the decline in adipose triglyceride lipase, regulated by PGC1α via PPARα. PPARα was also recently shown to be critical to the prevention of renal fibrosis in a murine model of diabetic kidney disease (11). Further exploration into the antioxidant and lipid metabolism from this pathway in broader studies may prove beneficial.

A third downstream target of PGC1α is nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2). Wu et al. found that mice given a single dose of the Nrf2 activator bardoxolone methyl 3 h before IRI had a smaller rise in creatinine and lower histopathology scores 24 h after reperfusion (90). Augmentation of Nrf2 with bardoxolone methyl has also been shown to minimize aristolochic acid-induced AKI (89). BEACON, a large clinical trial of bardoxolone methyl, examined whether Nrf2 activation could slow progression to end-stage renal disease or death from cardiovascular events in patients with diabetes and advanced chronic kidney disease (20). Unfortunately, BEACON was terminated early due to significantly more cardiac events, particularly heart failure, occurring in those receiving bardoxolone methyl. Post hoc analysis, however, found confounding factors such as poor patient selection and decreased bioavailability of angiotensin-2 receptor antagonists induced by enhanced Nrf2 expression that may have contributed to the negative overall result (13, 57). Thus further exploration of Nrf2 enhancement and its implications in renal health are merited.

Conclusions

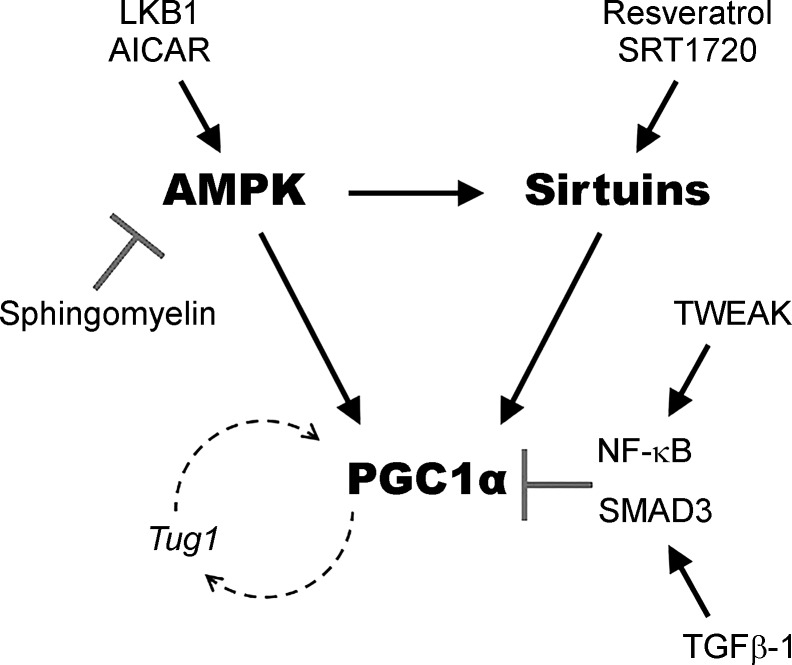

Decades of research applying techniques across biochemistry, molecular biology, physiology, and human genetics have carefully linked the health of mitochondria to the overall health of the kidney (21). As a master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis, PGC1α offers exciting possibilities for application to renal diseases. PGC1α has been found to be critical in protection from diverse AKI-inducing stressors, and loss of tubular PGC1α leads to enhanced susceptibility to AKI and long-term renal fibrosis. These findings make the PGC1α pathway an attractive target for AKI and CKD prevention and treatment, with several modulators of PGC1α currently identified (Fig. 1). As the effectors downstream of PGC1α are further elucidated, more targeted approaches may be unveiled in our ongoing efforts to decrease the burden of renal disease.

Fig. 1.

PGC1α and key modulators. AMP kinase, Sirtuin enzymes, and PGC1α comprise a circuit that senses and responds to stressors that affect energy metabolism. Depicted are biological and chemical modulators of this circuit that have been implicated in renal studies of PGC1α as described in the text. Arrows indicate positive interactions. “T” arrows indicate inhibitory interactions.

GRANTS

S. M. Parikh’s laboratory is supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants R01-DK-0950972, R01-HL-125275, and R01-HL-093234. M. R. Lynch is supported by NIH Grant T32-DK-007199.

DISCLOSURES

S. M. Parikh is listed as an inventor on patent applications filed by Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center regarding PGC1α and NAD+.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.R.L. and M.T.T. prepared figures; M.R.L. and M.T.T. drafted manuscript; M.R.L., M.T.T., and S.M.P. edited and revised manuscript; M.R.L., M.T.T., and S.M.P. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Due to space constraints, we are unable to cite and discuss many manuscripts.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aquilano K, Baldelli S, La Barbera L, Lettieri Barbato D, Tatulli G, Ciriolo MR. Adipose triglyceride lipase decrement affects skeletal muscle homeostasis during aging through FAs-PPARα-PGC-1α antioxidant response. Oncotarget 7: 23019–23032, 2016. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arany Z, Foo SY, Ma Y, Ruas JL, Bommi-Reddy A, Girnun G, Cooper M, Laznik D, Chinsomboon J, Rangwala SM, Baek KH, Rosenzweig A, Spiegelman BM. HIF-independent regulation of VEGF and angiogenesis by the transcriptional coactivator PGC-1alpha. Nature 451: 1008–1012, 2008. doi: 10.1038/nature06613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arany Z, Wagner BK, Ma Y, Chinsomboon J, Laznik D, Spiegelman BM. Gene expression-based screening identifies microtubule inhibitors as inducers of PGC-1alpha and oxidative phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 4721–4726, 2008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800979105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Archer SL. Mitochondrial dynamics—mitochondrial fission and fusion in human diseases. N Engl J Med 369: 2236–2251, 2013. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1215233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bai P, Canto C, Brunyánszki A, Huber A, Szántó M, Cen Y, Yamamoto H, Houten SM, Kiss B, Oudart H, Gergely P, Menissier-de Murcia J, Schreiber V, Sauve AA, Auwerx J. PARP-2 regulates SIRT1 expression and whole-body energy expenditure. Cell Metab 13: 450–460, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bai P, Cantó C, Oudart H, Brunyánszki A, Cen Y, Thomas C, Yamamoto H, Huber A, Kiss B, Houtkooper RH, Schoonjans K, Schreiber V, Sauve AA, Menissier-de Murcia J, Auwerx J. PARP-1 inhibition increases mitochondrial metabolism through SIRT1 activation. Cell Metab 13: 461–468, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brooks C, Cho SG, Wang CY, Yang T, Dong Z. Fragmented mitochondria are sensitized to Bax insertion and activation during apoptosis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 300: C447–C455, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00402.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brooks C, Wei Q, Cho SG, Dong Z. Regulation of mitochondrial dynamics in acute kidney injury in cell culture and rodent models. J Clin Invest 119: 1275–1285, 2009. doi: 10.1172/JCI37829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cantó C, Auwerx J. PGC-1alpha, SIRT1 and AMPK, an energy sensing network that controls energy expenditure. Curr Opin Lipidol 20: 98–105, 2009. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e328328d0a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cantó C, Gerhart-Hines Z, Feige JN, Lagouge M, Noriega L, Milne JC, Elliott PJ, Puigserver P, Auwerx J. AMPK regulates energy expenditure by modulating NAD+ metabolism and SIRT1 activity. Nature 458: 1056–1060, 2009. doi: 10.1038/nature07813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng R, Ding L, He X, Takahashi Y, Ma JX. Interaction of PPARα with the canonic Wnt pathway in the regulation of renal fibrosis. Diabetes 65: 3730–3743, 2016. doi: 10.2337/db16-0426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cherry AD, Suliman HB, Bartz RR, Piantadosi CA. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ co-activator 1-α as a critical co-activator of the murine hepatic oxidative stress response and mitochondrial biogenesis in Staphylococcus aureus sepsis. J Biol Chem 289: 41–52, 2014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.512483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chin MP, Wrolstad D, Bakris GL, Chertow GM, de Zeeuw D, Goldsberry A, Linde PG, McCullough PA, McMurray JJ, Wittes J, Meyer CJ. Risk factors for heart failure in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and stage 4 chronic kidney disease treated with bardoxolone methyl. J Card Fail 20: 953–958, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chinsomboon J, Ruas J, Gupta RK, Thom R, Shoag J, Rowe GC, Sawada N, Raghuram S, Arany Z. The transcriptional coactivator PGC-1alpha mediates exercise-induced angiogenesis in skeletal muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 21401–21406, 2009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909131106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collier JB, Whitaker RM, Eblen ST, Schnellmann RG. Rapid renal regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ Coactivator-1α by extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 in physiological and pathological conditions. J Biol Chem 291: 26850–26859, 2016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.754762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collins PB, Chaykin S. The management of nicotinamide and nicotinic acid in the mouse. J Biol Chem 247: 778–783, 1972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Craige SM, Kröller-Schön S, Li C, Kant S, Cai S, Chen K, Contractor MM, Pei Y, Schulz E, Keaney JF Jr. PGC-1α dictates endothelial function through regulation of eNOS expression. Sci Rep 6: 38210, 2016. doi: 10.1038/srep38210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cui L, Jeong H, Borovecki F, Parkhurst CN, Tanese N, Krainc D. Transcriptional repression of PGC-1alpha by mutant huntingtin leads to mitochondrial dysfunction and neurodegeneration. Cell 127: 59–69, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cunningham JT, Rodgers JT, Arlow DH, Vazquez F, Mootha VK, Puigserver P. mTOR controls mitochondrial oxidative function through a YY1-PGC-1alpha transcriptional complex. Nature 450: 736–740, 2007. doi: 10.1038/nature06322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Zeeuw D, Akizawa T, Audhya P, Bakris GL, Chin M, Christ-Schmidt H, Goldsberry A, Houser M, Krauth M, Lambers Heerspink HJ, McMurray JJ, Meyer CJ, Parving HH, Remuzzi G, Toto RD, Vaziri ND, Wanner C, Wittes J, Wrolstad D, Chertow GM; BEACON Trial Investigators . Bardoxolone methyl in type 2 diabetes and stage 4 chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 369: 2492–2503, 2013. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Emma F, Montini G, Parikh SM, Salviati L. Mitochondrial dysfunction in inherited renal disease and acute kidney injury. Nat Rev Nephrol 12: 267–280, 2016. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2015.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feingold KR, Wang Y, Moser A, Shigenaga JK, Grunfeld C. LPS decreases fatty acid oxidation and nuclear hormone receptors in the kidney. J Lipid Res 49: 2179–2187, 2008. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800233-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friedman JR, Nunnari J. Mitochondrial form and function. Nature 505: 335–343, 2014. doi: 10.1038/nature12985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Funk JA, Odejinmi S, Schnellmann RG. SRT1720 induces mitochondrial biogenesis and rescues mitochondrial function after oxidant injury in renal proximal tubule cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 333: 593–601, 2010. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.161992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guan Y, Wang SR, Huang XZ, Xie QH, Xu YY, Shang D, Hao CM. Nicotinamide mononucleotide, an NAD(+) precursor, rescues age-associated susceptibility to AKI in a sirtuin 1-dependent manner. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 2337–2352, 2017. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016040385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo K, Lu J, Huang Y, Wu M, Zhang L, Yu H, Zhang M, Bao Y, He JC, Chen H, Jia W. Protective role of PGC-1α in diabetic nephropathy is associated with the inhibition of ROS through mitochondrial dynamic remodeling. PLoS One 10: e0125176, 2015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haden DW, Suliman HB, Carraway MS, Welty-Wolf KE, Ali AS, Shitara H, Yonekawa H, Piantadosi CA. Mitochondrial biogenesis restores oxidative metabolism during Staphylococcus aureus sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 176: 768–777, 2007. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200701-161OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27a.Han SH, Malaga-Dieguez L, Chinga F, Kang HM, Tao J, Reidy K, Suzuki K. Deletion of Lkb1 in renal tubule epithelial cells leads to CKD by altering metabolism. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 439–453, 2016. doi: 10.168/ASN.2014121181.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han SH, Wu MY, Nam BY, Park JT, Yoo TH, Kang SW, Park J, Chinga F, Li SY, Susztak K. PGC-1α protects from notch-induced kidney fibrosis development. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 3312–3322, 2017. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2017020130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hsieh YC, Choudhry MA, Yu HP, Shimizu T, Yang S, Suzuki T, Chen J, Bland KI, Chaudry IH. Inhibition of cardiac PGC-1alpha expression abolishes ERbeta agonist-mediated cardioprotection following trauma-hemorrhage. FASEB J 20: 1109–1117, 2006. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5549com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hsieh YC, Yang S, Choudhry MA, Yu HP, Rue LW III, Bland KI, Chaudry IH. PGC-1 upregulation via estrogen receptors: a common mechanism of salutary effects of estrogen and flutamide on heart function after trauma-hemorrhage. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 289: H2665–H2672, 2005. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00682.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huss JM, Kopp RP, Kelly DP. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor coactivator-1alpha (PGC-1alpha) coactivates the cardiac-enriched nuclear receptors estrogen-related receptor-alpha and -gamma. Identification of novel leucine-rich interaction motif within PGC-1alpha. J Biol Chem 277: 40265–40274, 2002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206324200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ishihara M, Urushido M, Hamada K, Matsumoto T, Shimamura Y, Ogata K, Inoue K, Taniguchi Y, Horino T, Fujieda M, Fujimoto S, Terada Y. Sestrin-2 and BNIP3 regulate autophagy and mitophagy in renal tubular cells in acute kidney injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 305: F495–F509, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00642.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jäger S, Handschin C, St-Pierre J, Spiegelman BM. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) action in skeletal muscle via direct phosphorylation of PGC-1alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 12017–12022, 2007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705070104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jang C, Oh S, Wada S, Rowe GC, Liu L, Chan MC, Rhee J, Baca LG, Kim E, Ghosh CC, Parikh SM, Jiang A, Kasper D, Arany Z. A metabolite of branched chain amino acids drives vascular fatty acid transport and causes glucose tolerance. Nat Med 22: 421–426, 2016. doi: 10.1038/nm.4057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jesinkey SR, Funk JA, Stallons LJ, Wills LP, Megyesi JK, Beeson CC, Schnellmann RG. Formoterol restores mitochondrial and renal function after ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 1157–1162, 2014. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013090952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang M, Wei Q, Dong G, Komatsu M, Su Y, Dong Z. Autophagy in proximal tubules protects against acute kidney injury. Kidney Int 82: 1271–1283, 2012. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kang HM, Ahn SH, Choi P, Ko YA, Han SH, Chinga F, Park AS, Tao J, Sharma K, Pullman J, Bottinger EP, Goldberg IJ, Susztak K. Defective fatty acid oxidation in renal tubular epithelial cells has a key role in kidney fibrosis development. Nat Med 21: 37–46, 2015. doi: 10.1038/nm.3762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khader A, Yang WL, Kuncewitch M, Jacob A, Prince JM, Asirvatham JR, Nicastro J, Coppa GF, Wang P. Sirtuin 1 activation stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis and attenuates renal injury after ischemia-reperfusion. Transplantation 98: 148–156, 2014. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lehman JJ, Barger PM, Kovacs A, Saffitz JE, Medeiros DM, Kelly DP. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 promotes cardiac mitochondrial biogenesis. J Clin Invest 106: 847–856, 2000. doi: 10.1172/JCI10268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lempiäinen J, Finckenberg P, Levijoki J, Mervaala E. AMPK activator AICAR ameliorates ischaemia reperfusion injury in the rat kidney. Br J Pharmacol 166: 1905–1915, 2012. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01895.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lempiäinen J, Finckenberg P, Mervaala EE, Sankari S, Levijoki J, Mervaala EM. Caloric restriction ameliorates kidney ischaemia/reperfusion injury through PGC-1α-eNOS pathway and enhanced autophagy. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 208: 410–421, 2013. doi: 10.1111/apha.12120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li S, Mariappan N, Megyesi J, Shank B, Kannan K, Theus S, Price PM, Duffield JS, Portilla D. Proximal tubule PPARα attenuates renal fibrosis and inflammation caused by unilateral ureteral obstruction. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 305: F618–F627, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00309.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li S, Nagothu KK, Desai V, Lee T, Branham W, Moland C, Megyesi JK, Crew MD, Portilla D. Transgenic expression of proximal tubule peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha in mice confers protection during acute kidney injury. Kidney Int 76: 1049–1062, 2009. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43a.Li SY, Park J, Qiu C, Han SH, Palmer MB, Arany Z, Susztak K. Increasing the level of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator-1α in podocytes results in collapsing glomerulopathy. JCI Insight 2: pii: 92930, 2017. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.92930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin J, Handschin C, Spiegelman BM. Metabolic control through the PGC-1 family of transcription coactivators. Cell Metab 1: 361–370, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin J, Puigserver P, Donovan J, Tarr P, Spiegelman BM. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1beta (PGC-1beta), a novel PGC-1-related transcription coactivator associated with host cell factor. J Biol Chem 277: 1645–1648, 2002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100631200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ling C, Del Guerra S, Lupi R, Rönn T, Granhall C, Luthman H, Masiello P, Marchetti P, Groop L, Del Prato S. Epigenetic regulation of PPARGC1A in human type 2 diabetic islets and effect on insulin secretion. Diabetologia 51: 615–622, 2008. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0916-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Long J, Badal SS, Ye Z, Wang Y, Ayanga BA, Galvan DL, Green NH, Chang BH, Overbeek PA, Danesh FR. Long noncoding RNA Tug1 regulates mitochondrial bioenergetics in diabetic nephropathy. J Clin Invest 126: 4205–4218, 2016. doi: 10.1172/JCI87927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lynn EG, Stevens MV, Wong RP, Carabenciov D, Jacobson J, Murphy E, Sack MN. Transient upregulation of PGC-1alpha diminishes cardiac ischemia tolerance via upregulation of ANT1. J Mol Cell Cardiol 49: 693–698, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matejovic M, Valesova L, Benes J, Sykora R, Hrstka R, Chvojka J. Molecular differences in susceptibility of the kidney to sepsis-induced kidney injury. BMC Nephrol 18: 183, 2017. doi: 10.1186/s12882-017-0602-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miura S, Kai Y, Kamei Y, Ezaki O. Isoform-specific increases in murine skeletal muscle peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator-1alpha (PGC-1alpha) mRNA in response to beta2-adrenergic receptor activation and exercise. Endocrinology 149: 4527–4533, 2008. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morigi M, Perico L, Rota C, Longaretti L, Conti S, Rottoli D, Novelli R, Remuzzi G, Benigni A. Sirtuin 3-dependent mitochondrial dynamic improvements protect against acute kidney injury. J Clin Invest 125: 715–726, 2015. doi: 10.1172/JCI77632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mukhopadhyay P, Horváth B, Zsengellér Z, Zielonka J, Tanchian G, Holovac E, Kechrid M, Patel V, Stillman IE, Parikh SM, Joseph J, Kalyanaraman B, Pacher P. Mitochondrial-targeted antioxidants represent a promising approach for prevention of cisplatin-induced nephropathy. Free Radic Biol Med 52: 497–506, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oberkofler H, Linnemayr V, Weitgasser R, Klein K, Xie M, Iglseder B, Krempler F, Paulweber B, Patsch W. Complex haplotypes of the PGC-1alpha gene are associated with carbohydrate metabolism and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 53: 1385–1393, 2004. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.5.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pagliarini DJ, Calvo SE, Chang B, Sheth SA, Vafai SB, Ong SE, Walford GA, Sugiana C, Boneh A, Chen WK, Hill DE, Vidal M, Evans JG, Thorburn DR, Carr SA, Mootha VK. A mitochondrial protein compendium elucidates complex I disease biology. Cell 134: 112–123, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Parekh DJ, Weinberg JM, Ercole B, Torkko KC, Hilton W, Bennett M, Devarajan P, Venkatachalam MA. Tolerance of the human kidney to isolated controlled ischemia. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 506–517, 2013. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012080786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Patten IS, Rana S, Shahul S, Rowe GC, Jang C, Liu L, Hacker MR, Rhee JS, Mitchell J, Mahmood F, Hess P, Farrell C, Koulisis N, Khankin EV, Burke SD, Tudorache I, Bauersachs J, del Monte F, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Karumanchi SA, Arany Z. Cardiac angiogenic imbalance leads to peripartum cardiomyopathy. Nature 485: 333–338, 2012. doi: 10.1038/nature11040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pergola PE, Raskin P, Toto RD, Meyer CJ, Huff JW, Grossman EB, Krauth M, Ruiz S, Audhya P, Christ-Schmidt H, Wittes J, Warnock DG; BEAM Study Investigators . Bardoxolone methyl and kidney function in CKD with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 365: 327–336, 2011. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Plotnikov EY, Kazachenko AV, Vyssokikh MY, Vasileva AK, Tcvirkun DV, Isaev NK, Kirpatovsky VI, Zorov DB. The role of mitochondria in oxidative and nitrosative stress during ischemia/reperfusion in the rat kidney. Kidney Int 72: 1493–1502, 2007. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Portilla D, Dai G, McClure T, Bates L, Kurten R, Megyesi J, Price P, Li S. Alterations of PPARalpha and its coactivator PGC-1 in cisplatin-induced acute renal failure. Kidney Int 62: 1208–1218, 2002. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2002.kid553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Puigserver P, Rhee J, Donovan J, Walkey CJ, Yoon JC, Oriente F, Kitamura Y, Altomonte J, Dong H, Accili D, Spiegelman BM. Insulin-regulated hepatic gluconeogenesis through FOXO1-PGC-1alpha interaction. Nature 423: 550–555, 2003. doi: 10.1038/nature01667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Puigserver P, Wu Z, Park CW, Graves R, Wright M, Spiegelman BM. A cold-inducible coactivator of nuclear receptors linked to adaptive thermogenesis. Cell 92: 829–839, 1998. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81410-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Qin W, Haroutunian V, Katsel P, Cardozo CP, Ho L, Buxbaum JD, Pasinetti GM. PGC-1alpha expression decreases in the Alzheimer disease brain as a function of dementia. Arch Neurol 66: 352–361, 2009. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2008.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rasbach KA, Schnellmann RG. Signaling of mitochondrial biogenesis following oxidant injury. J Biol Chem 282: 2355–2362, 2007. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608009200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rhee J, Inoue Y, Yoon JC, Puigserver P, Fan M, Gonzalez FJ, Spiegelman BM. Regulation of hepatic fasting response by PPARgamma coactivator-1alpha (PGC-1): requirement for hepatocyte nuclear factor 4alpha in gluconeogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 4012–4017, 2003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730870100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rodgers JT, Lerin C, Haas W, Gygi SP, Spiegelman BM, Puigserver P. Nutrient control of glucose homeostasis through a complex of PGC-1alpha and SIRT1. Nature 434: 113–118, 2005. doi: 10.1038/nature03354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ruas JL, White JP, Rao RR, Kleiner S, Brannan KT, Harrison BC, Greene NP, Wu J, Estall JL, Irving BA, Lanza IR, Rasbach KA, Okutsu M, Nair KS, Yan Z, Leinwand LA, Spiegelman BM. A PGC-1α isoform induced by resistance training regulates skeletal muscle hypertrophy. Cell 151: 1319–1331, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ruiz-Andres O, Suarez-Alvarez B, Sánchez-Ramos C, Monsalve M, Sanchez-Niño MD, Ruiz-Ortega M, Egido J, Ortiz A, Sanz AB. The inflammatory cytokine TWEAK decreases PGC-1α expression and mitochondrial function in acute kidney injury. Kidney Int 89: 399–410, 2016. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sharabi K, Lin H, Tavares CD, Dominy JE, Camporez JP, Perry RJ, Schilling R, Rines AK, Lee J, Hickey M, Bennion M, Palmer M, Nag PP, Bittker JA, Perez J, Jedrychowski MP, Ozcan U, Gygi SP, Kamenecka TM, Shulman GI, Schreiber SL, Griffin PR, Puigserver P. Selective chemical inhibition of PGC-1α gluconeogenic activity ameliorates Type 2 diabetes. Cell 169: 148–160.e15, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sharma K, Karl B, Mathew AV, Gangoiti JA, Wassel CL, Saito R, Pu M, Sharma S, You YH, Wang L, Diamond-Stanic M, Lindenmeyer MT, Forsblom C, Wu W, Ix JH, Ideker T, Kopp JB, Nigam SK, Cohen CD, Groop PH, Barshop BA, Natarajan L, Nyhan WL, Naviaux RK. Metabolomics reveals signature of mitochondrial dysfunction in diabetic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 1901–1912, 2013. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013020126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sjöstrand FS, Rhodin J. The ultrastructure of the proximal convoluted tubules of the mouse kidney as revealed by high resolution electron microscopy. Exp Cell Res 4: 426–456, 1953. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(53)90170-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Smith JA, Stallons LJ, Collier JB, Chavin KD, Schnellmann RG. Suppression of mitochondrial biogenesis through toll-like receptor 4-dependent mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling in endotoxin-induced acute kidney injury. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 352: 346–357, 2015. doi: 10.1124/jpet.114.221085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Soriano FX, Liesa M, Bach D, Chan DC, Palacín M, Zorzano A. Evidence for a mitochondrial regulatory pathway defined by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator-1 alpha, estrogen-related receptor-alpha, and mitofusin 2. Diabetes 55: 1783–1791, 2006. doi: 10.2337/db05-0509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Spoto B, Pisano A, Zoccali C. Insulin resistance in chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 311: F1087–F1108, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00340.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.St-Pierre J, Drori S, Uldry M, Silvaggi JM, Rhee J, Jäger S, Handschin C, Zheng K, Lin J, Yang W, Simon DK, Bachoo R, Spiegelman BM. Suppression of reactive oxygen species and neurodegeneration by the PGC-1 transcriptional coactivators. Cell 127: 397–408, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Suliman HB, Carraway MS, Welty-Wolf KE, Whorton AR, Piantadosi CA. Lipopolysaccharide stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis via activation of nuclear respiratory factor-1. J Biol Chem 278: 41510–41518, 2003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304719200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sweeney TE, Suliman HB, Hollingsworth JW, Welty-Wolf KE, Piantadosi CA. A toll-like receptor 2 pathway regulates the Ppargc1a/b metabolic co-activators in mice with Staphylococcal aureus sepsis. PLoS One 6: e25249, 2011. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Szeto HH, Liu S, Soong Y, Seshan SV, Cohen-Gould L, Manichev V, Feldman LC, Gustafsson T. Mitochondria protection after acute ischemia prevents prolonged upregulation of IL-1beta and IL-18 and arrests CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 1437–1449, 2017. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016070761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Szeto HH, Liu S, Soong Y, Wu D, Darrah SF, Cheng FY, Zhao Z, Ganger M, Tow CY, Seshan SV. Mitochondria-targeted peptide accelerates ATP recovery and reduces ischemic kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 1041–1052, 2011. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010080808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Takasu O, Gaut JP, Watanabe E, To K, Fagley RE, Sato B, Jarman S, Efimov IR, Janks DL, Srivastava A, Bhayani SB, Drewry A, Swanson PE, Hotchkiss RS. Mechanisms of cardiac and renal dysfunction in patients dying of sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 187: 509–517, 2013. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201211-1983OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tran M, Tam D, Bardia A, Bhasin M, Rowe GC, Kher A, Zsengeller ZK, Akhavan-Sharif MR, Khankin EV, Saintgeniez M, David S, Burstein D, Karumanchi SA, Stillman IE, Arany Z, Parikh SM. PGC-1α promotes recovery after acute kidney injury during systemic inflammation in mice. J Clin Invest 121: 4003–4014, 2011. doi: 10.1172/JCI58662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tran MT, Zsengeller ZK, Berg AH, Khankin EV, Bhasin MK, Kim W, Clish CB, Stillman IE, Karumanchi SA, Rhee EP, Parikh SM. PGC1α drives NAD biosynthesis linking oxidative metabolism to renal protection. Nature 531: 528–532, 2016. doi: 10.1038/nature17184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Vainshtein A, Tryon LD, Pauly M, Hood DA. Role of PGC-1α during acute exercise-induced autophagy and mitophagy in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 308: C710–C719, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00380.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Valtat B, Riveline JP, Zhang P, Singh-Estivalet A, Armanet M, Venteclef N, Besseiche A, Kelly DP, Tronche F, Ferré P, Gautier JF, Bréant B, Blondeau B. Fetal PGC-1α overexpression programs adult pancreatic β-cell dysfunction. Diabetes 62: 1206–1216, 2013. doi: 10.2337/db12-0314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vega RB, Huss JM, Kelly DP. The coactivator PGC-1 cooperates with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha in transcriptional control of nuclear genes encoding mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation enzymes. Mol Cell Biol 20: 1868–1876, 2000. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.5.1868-1876.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Verdin E. NAD+ in aging, metabolism, and neurodegeneration. Science 350: 1208–1213, 2015. doi: 10.1126/science.aac4854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wang Y, Moser AH, Shigenaga JK, Grunfeld C, Feingold KR. Downregulation of liver X receptor-alpha in mouse kidney and HK-2 proximal tubular cells by LPS and cytokines. J Lipid Res 46: 2377–2387, 2005. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500134-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Weinberg JM. Mitochondrial biogenesis in kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 431–436, 2011. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010060643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Weydt P, Pineda VV, Torrence AE, Libby RT, Satterfield TF, Lazarowski ER, Gilbert ML, Morton GJ, Bammler TK, Strand AD, Cui L, Beyer RP, Easley CN, Smith AC, Krainc D, Luquet S, Sweet IR, Schwartz MW, La Spada AR. Thermoregulatory and metabolic defects in Huntington’s disease transgenic mice implicate PGC-1alpha in Huntington’s disease neurodegeneration. Cell Metab 4: 349–362, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wu J, Liu X, Fan J, Chen W, Wang J, Zeng Y, Feng X, Yu X, Yang X. Bardoxolone methyl (BARD) ameliorates aristolochic acid (AA)-induced acute kidney injury through Nrf2 pathway. Toxicology 318: 22–31, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wu QQ, Wang Y, Senitko M, Meyer C, Wigley WC, Ferguson DA, Grossman E, Chen J, Zhou XJ, Hartono J, Winterberg P, Chen B, Agarwal A, Lu CY. Bardoxolone methyl (BARD) ameliorates ischemic AKI and increases expression of protective genes Nrf2, PPARγ, and HO-1. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 300: F1180–F1192, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00353.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wu Z, Huang X, Feng Y, Handschin C, Feng Y, Gullicksen PS, Bare O, Labow M, Spiegelman B, Stevenson SC. Transducer of regulated CREB-binding proteins (TORCs) induce PGC-1alpha transcription and mitochondrial biogenesis in muscle cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 14379–14384, 2006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606714103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wu Z, Puigserver P, Andersson U, Zhang C, Adelmant G, Mootha V, Troy A, Cinti S, Lowell B, Scarpulla RC, Spiegelman BM. Mechanisms controlling mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration through the thermogenic coactivator PGC-1. Cell 98: 115–124, 1999. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80611-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yin W, Naini SM, Chen G, Hentschel DM, Humphreys BD, Bonventre JV. Mammalian target of rapamycin mediates kidney injury molecule 1-dependent tubule injury in a surrogate model. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 1943–1957, 2016. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015050500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Youle RJ, van der Bliek AM. Mitochondrial fission, fusion, and stress. Science 337: 1062–1065, 2012. doi: 10.1126/science.1219855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zaza G, Granata S, Masola V, Rugiu C, Fantin F, Gesualdo L, Schena FP, Lupo A. Downregulation of nuclear-encoded genes of oxidative metabolism in dialyzed chronic kidney disease patients. PLoS One 8: e77847, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zhan M, Brooks C, Liu F, Sun L, Dong Z. Mitochondrial dynamics: regulatory mechanisms and emerging role in renal pathophysiology. Kidney Int 83: 568–581, 2013. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zhang LN, Zhou HY, Fu YY, Li YY, Wu F, Gu M, Wu LY, Xia CM, Dong TC, Li JY, Shen JK, Li J. Novel small-molecule PGC-1α transcriptional regulator with beneficial effects on diabetic db/db mice. Diabetes 62: 1297–1307, 2013. doi: 10.2337/db12-0703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zheng B, Liao Z, Locascio JJ, Lesniak KA, Roderick SS, Watt ML, Eklund AC, Zhang-James Y, Kim PD, Hauser MA, Grünblatt E, Moran LB, Mandel SA, Riederer P, Miller RM, Federoff HJ, Wüllner U, Papapetropoulos S, Youdim MB, Cantuti-Castelvetri I, Young AB, Vance JM, Davis RL, Hedreen JC, Adler CH, Beach TG, Graeber MB, Middleton FA, Rochet JC, Scherzer CR; Global PD Gene Expression (GPEX) Consortium . PGC-1α, a potential therapeutic target for early intervention in Parkinson’s disease. Sci Transl Med 2: 52ra73, 2010. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zsengellér ZK, Ellezian L, Brown D, Horváth B, Mukhopadhyay P, Kalyanaraman B, Parikh SM, Karumanchi SA, Stillman IE, Pacher P. Cisplatin nephrotoxicity involves mitochondrial injury with impaired tubular mitochondrial enzyme activity. J Histochem Cytochem 60: 521–529, 2012. doi: 10.1369/0022155412446227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]