Abstract

Fatty liver disease (FLD), the most common chronic liver disease in the United States, may be caused by alcohol or the metabolic syndrome. Alcohol is oxidized in the cytosol of hepatocytes by alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH), which generates NADH and increases cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio. The increased ratio may be important for development of FLD, but our ability to examine this question is hindered by methodological limitations. To address this, we used the genetically encoded fluorescent sensor Peredox to obtain dynamic, real-time measurements of cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in living hepatocytes. Peredox was expressed in dissociated rat hepatocytes and HepG2 cells by transfection, and in mouse liver slices by tail-vein injection of adeno-associated virus (AAV)-encoded sensor. Under control conditions, hepatocytes and liver slices exhibit a relatively low (oxidized) cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio as reported by Peredox. The ratio responds rapidly and reversibly to substrates of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and sorbitol dehydrogenase (SDH). Ethanol causes a robust dose-dependent increase in cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio, and this increase is mitigated by the presence of NAD+-generating substrates of LDH or SDH. In contrast to hepatocytes and slices, HepG2 cells exhibit a relatively high (reduced) ratio and show minimal responses to substrates of ADH and SDH. In slices, we show that comparable results are obtained with epifluorescence imaging and two-photon fluorescence lifetime imaging (2p-FLIM). Live cell imaging with Peredox is a promising new approach to investigate cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in hepatocytes. Imaging in liver slices is particularly attractive because it allows preservation of liver microanatomy and metabolic zonation of hepatocytes.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY We describe and validate a new approach for measuring free cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in hepatocytes and liver slices: live cell imaging with the fluorescent biosensor Peredox. This approach yields dynamic, real-time measurements of the ratio in living, functioning liver cells, overcoming many limitations of previous methods for measuring this important redox parameter. The feasibility of using Peredox in liver slices is particularly attractive because slices allow preservation of hepatic microanatomy and metabolic zonation of hepatocytes.

Keywords: alcohol, alcohol dehydrogenase, fluorescent biosensor, liver slice, NADH

INTRODUCTION

Fatty liver disease (FLD) is the most common cause of chronic liver disease in the United States, and its incidence is increasing in the rest of the world (25). FLD may be caused by alcohol (alcoholic fatty liver disease, AFLD) or by the metabolic syndrome consisting of obesity, insulin resistance, hypertension, and dyslipidemia (nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, NAFLD). Due to the increasing incidence of obesity and diabetes, NAFLD has reached epidemic proportions in the United States, with as many as one-third of Americans estimated to have NAFLD (5). Management of FLD is based on modification of risk factors, as there are no effective therapies. There is a critical need to understand the underlying mechanisms of FLD to devise effective treatments.

Alcohol is oxidized in the cytosol of hepatocytes by alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH), which converts NAD+ to NADH and leads to increased cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio (23). The increased ratio promotes triglyceride accumulation in hepatocytes by inhibiting fatty acid β-oxidation (23) and may thus contribute to development of AFLD. Furthermore, data from patients and animal models suggest that cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in hepatocytes is also increased in NAFLD (26, 36), and manipulations that increase NAD+ content may improve NAFLD (11, 34). However, whether cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio is increased in the setting of chronic alcohol exposure remains somewhat controversial (10, 22, 24, 31, 32, 35). Ultimately, the precise significance of increased cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in the pathogenesis of FLD remains unresolved.

The ability to examine this question is limited by methodology, as current approaches (chiefly biochemical and autofluorescence-based) do not permit direct measurements of free cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in living, functioning hepatocytes. Commercially available enzymatic assay kits can be used for direct biochemical detection of NADH and NAD+, but they require destruction of cells under study, precluding dynamic measurements in living cells or in vivo. The assay conditions are usually denaturing such that the protein-bound pool of NADH and NAD+ is released and detected, obscuring the smaller but physiologically relevant free pool. Finally, such assays cannot distinguish cytosolic from mitochondrial NADH/NAD+ ratio (unless subcellular fractionation is previously performed) and therefore yield measurements that are heavily weighted toward the larger and substantially more reduced mitochondrial pool of NADH/NAD+ (38). Indirect biochemical approaches are based on measurement of a redox couple assumed to be in equilibrium with the cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio via a cytosolic enzyme; classically, the lactate/pyruvate couple via lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). Although this does reflect the free cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio, and thus yields a more meaningful measurement, it still necessitates destruction of cells or tissue, again precluding dynamic measurements in living cells or in vivo.

In addition, biochemical approaches cannot provide ratio measurements in a cell-specific or microanatomic context, which is an important shortcoming since the mammalian liver exhibits microanatomic “zones” of hepatocytes with distinct metabolic programs: for example, fatty acid β-oxidation and oxidative phosphorylation occur predominantly in the periportal region (zone 1), whereas glycolysis and lipogenesis occur predominantly in the centrilobular or perivenous region (zone 3) (16, 19, 20, 33). Many liver diseases in humans show zonal predilection; specifically, FLD preferentially affects zone 3. Among existing approaches, direct optical measurements of NADH autofluorescence can be performed in living cells and in a microanatomic context. However, autofluorescence measurements cannot reliably distinguish between NADH and NADPH, or between cytosolic and mitochondrial pools of NAD(P)H; some strategies are available for approximating these pools, but the characterizations are imperfect. Autofluorescence measurements are thus primarily an indication of mitochondrial NAD(P)H, which is the larger pool.

These limitations can be overcome by using a genetically encoded fluorescent sensor (Peredox) that enables specific measurement of free cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio directly and dynamically, in intact, physiologically relevant systems (9, 17, 18, 28). In the present study, we have used live cell imaging with Peredox to directly examine cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in liver cells, which had not been previously accomplished. We examine the ratio as reported by Peredox in dissociated rat hepatocytes, in the human hepatocyte-derived cell line HepG2, and in mouse liver slices, using epifluorescence imaging and two-photon fluorescence lifetime imaging (2p-FLIM). We find that live cell imaging with Peredox is a promising new approach to investigate hepatocyte cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio, particularly in liver slices, which allow preservation of liver microanatomy and metabolic zonation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Experiments were conducted on male C57Bl/6N mice (aged 2–6 wk) and adult female Lewis rats (Charles River, Wilmington, MA). Animals were held in a 12-h:12-h light-dark cycle at room temperature (20–25°C) and fed ad libitum. Peredox was expressed in mouse liver by tail-vein injection of adeno-associated virus (AAV) 2/8 or 2/9 encoding Peredox under control of the CAG promoter (titer: 3.48 × 1011–2.97 × 1013 GC/ml). Mice were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane and euthanized by decapitation. Animal procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Harvard University and Massachusetts General Hospital. All chemicals and reagents were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise indicated.

Isolation, transfection, and culture of rat hepatocytes.

Rat hepatocytes were freshly isolated by collagenase digestion, as described (27). Hepatocytes were plated on fibronectin-coated glass coverslips (0.75 M cells/well in a 6-well plate) and incubated for 4 h in C+M medium (DMEM-high glucose with 10% FBS, 0.5 U/ml insulin, 7 ng/ml glucagon, 20 ng/ml epidermal growth factor, 7.5 μg/ml hydrocortisone, 200 U/ml penicillin, 200 μg/ml streptomycin, and 50 μg/ml gentamycin) at 37°C and 5% CO2. Hepatocytes were transfected with 1.0 µg Peredox-mCherry in pcDNA3.1 using Effectene transfection reagent (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following manufacturer’s instructions. After 12–14 h, the transfection reaction was removed and fresh C+M medium was added. Experiments were carried out 24–32 h afterward (36–48 h after isolation).

Transfection and culture of HepG2 cells.

HepG2 cells were plated on protamine-coated glass coverslips and incubated in DMEM-high glucose with 10% BCS (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA), 2 mM HEPES, and 100 U/ml penicillin plus 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) at 37°C and 5% CO2. The following day, cells were transfected with 0.4 µg Peredox-mCherry in pcDNA3.1 using Effectene transfection reagent. The following day, the transfection reaction was removed and fresh medium was added. Experiments were carried out 1 to 2 days afterward (3 to 4 days after plating). Cell line authentication and testing for mycoplasma contamination were not performed.

Preparation of mouse liver slices.

Two weeks after tail-vein injection of AAV-encoded Peredox, mice were euthanized, and the liver was dissected and submerged in ice-cold Krebs-Henseleit bicarbonate (KHB) buffer with 10 mM glucose [KHB (in mM): 115 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 1 MgCl2, pH 7.4 when bubbled with 95% O2-5% CO2]. Two ~0.2 × 0.2 × 0.2 cm fragments of liver from the left lobe or the left middle lobe were cut with a scalpel and placed on a block of agar that served as “backstop” during slicing. The base of the tissue fragments and the agar block were glued onto the metal platform of a 7,000-smz2 vibrating slicer (Campden Instruments, Lafayette, IN). The slicing chamber was filled with ice-cold KHB with 10 mM glucose bubbled with 95% O2-5% CO2. Approximately 10–15 slices were cut (200-µm thickness, 80-Hz frequency, 2-mm amplitude, 0.04 mm/s speed) and immediately transferred to a recovery chamber, filled with KHB with 10 mM glucose at 37°C bubbled with 95% O2-5% CO2, in which slices rested on a mesh. The entire procedure took ~20–30 min. Slices were used for imaging experiments between 30 min and 4 h after slicing.

Epifluorescence imaging of Peredox in rat hepatocytes and HepG2 cells.

Wide-field time-lapse epifluorescence experiments were performed in a diamond-shaped solution chamber mounted on the headstage of an inverted microscope (Nikon, Tokyo) under continuous perfusion (1.2 ml/min flow rate) heated at 37°C. Glass coverslips containing plated cells were cracked with a diamond-tip pen, and shards were placed in the recording chamber. Bath solution contained (in mM) 140 NaCl, 10 HEPES, 5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2; pH 7.4 with 1 M NaOH. Glucose and substrates of cytosolic dehydrogenases were added as indicated. Glass shards were preincubated in bath solution plus 10 mM glucose at 37°C for 10 min before placing in the recording chamber. Emitted light was collected with an Andor Revolution DSD spinning disk unit (Andor, Belfast, UK) using a ×20/0.75NA objective illuminated with a LED light source (Lumencor, Beaverton, OR). Peredox-mCherry consists of Peredox (based on a green fluorescent protein) plus a red fluorescent protein (mCherry) fused to its COOH terminus to serve as a control for sensor expression. The green and red fluorophores of Peredox-mCherry were excited using 405/10 nm and 578/16 nm band-pass filters, emission was collected through 525/50 nm and 629/56 nm band-pass filters, and excitation and emission light were separated with 490-nm and 590-nm short pass dichroics, respectively. Images were acquired with iQ (Andor) every 15 s at 50-ms exposure and 4 × 4 binning. Fluorescence intensity was quantified with ImageJ as the mean over a region of interest (ROI) drawn around each analyzed cell.

Peredox signal was obtained by dividing green fluorescence by red fluorescence. For each cell, the signal was then normalized with an internal calibration approach as follows: the minimum value or “floor” was obtained in 10 mM pyruvate, and the maximum value or “ceiling” was obtained in 10 mM ethanol for hepatocytes or 10 mM lactate for HepG2 cells. Normalized Peredox signal was then expressed as a percent scale of 0–100, where 0 is the “floor” and 100 is the “ceiling.” Where indicated, red fluorescence was ignored in the data analysis and normalized Peredox signal was obtained from the green fluorescence alone.

Epifluorescence imaging of Peredox in mouse liver slices.

Wide-field time-lapse epifluorescence experiments were performed in a dual-perfusion chamber mounted on the headstage of an upright Olympus BX51WI microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA) and heated at 34–36°C. Each slice was placed on a metal grid (Supertech Instruments, Zurich, Switzerland) and held down by a slice anchor or “harp” (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT). The chamber contains two solution inputs, one above and one below the slice, so that the slice receives continuous perfusion from above and below. Each line contained KHB bubbled with 95% O2-5% CO2 at a flow rate of 2.5 ml/min (total flow rate 5 ml/min). Glucose and substrates of cytosolic dehydrogenases were added as indicated. Peredox (containing the green fluorophore only) was excited using a Xenon lamp and monochromator with a 12.5 nm Polychrome IV band-pass (TILL Photonics, Hillsboro, OR) at 405 nm. A triple-band dichroic (69002, Chroma Technology, Bellows Falls, VT) was used to separate emission light that was collected with a CCD camera (IMAGO-QE, TILL Photonics) using a ×4/0.13NA objective. Images were acquired with TILLVision v4.0.1 (TILL Photonics) every 15 s at 10-ms exposure and 4 × 4 binning. Fluorescence intensity was quantified with ImageJ as the mean over a ROI drawn around each analyzed slice. The strings from the slice anchor or “harp” were deliberately excluded from the ROI.

Peredox signal was obtained as green fluorescence. For each slice, the signal was then normalized with an internal calibration approach as follows: the minimum value or “floor” was obtained in 10 mM pyruvate, and the maximum value or “ceiling” was obtained in 10 mM ethanol. Normalized Peredox signal was then expressed as a percent scale of 0–100, where 0 is the “floor” and 100 is the “ceiling.”

Two-photon fluorescence lifetime imaging of Peredox in liver slices.

Two-photon fluorescence lifetime imaging (2p-FLIM) experiments were performed in a single-perfusion chamber mounted on the headstage of a modified Thorlabs Bergamo II microscope (Thorlabs Imaging Systems, Sterling, VA) with hybrid photodetectors R11322U-40 (Hamamatsu Photonics, Shizuoka, Japan) under continuous single perfusion (5 ml/min flow rate) heated at 34°C. The light source was a Chameleon Vision-S tunable Ti-Sapphire mode-locked laser (80 MHz, ∼75 fs; Coherent, Santa Clara, CA). The photodetector signals and laser sync signals were preamplified and then digitized at 1.25 gigasamples/s using a field-programmable gate array board (PC720 with FMC125 and FMC122 modules, 4DSP, Austin, TX) with custom firmware. Each slice was attached to a poly-lysine-coated glass coverslip and placed in the chamber. The chamber was perfused with KHB bubbled with 95% O2-5% CO2. Glucose and substrates of cytosolic dehydrogenases were added as indicated.

For each slice, 8–10 hepatocytes expressing Peredox were selected for analysis within a single 20× field (360 × 360 µm). The fields were located in the centrilobular (zone 3) region, since the higher levels of Peredox expression in that region resulted in higher photon counts and thus more robust lifetime measurements. Images were acquired every 15–20 s. Laboratory-built firmware and software performed time-correlated single photon counting to determine the arrival time of each photon relative to the laser pulse; the distribution of these arrival times indicates the fluorescence lifetime (28). Lifetime histograms were fitted using nonlinear least-squares fitting in MATLAB (Mathworks, Natick, MA), with a two-exponential decay convolved with a Gaussian for the IRF (42). Microscope control and image acquisition were performed by a modified version of the ScanImage software written in MATLAB (29) (provided by Bernardo Sabatini, and modified by G.Y.). Image analysis was performed using MATLAB software developed in the Yellen laboratory. ROIs were defined around individual hepatocytes, and photon statistics were calculated for all pixels within the ROI. Typical ROIs encompassed 100–900 image pixels, in images of 128 × 128 or 256 × 256 pixels acquired at a scanning rate of ~2 ms per line. Most data points in the time series plots of lifetimes are for the mean value of 20 sequentially acquired frames.

Conversion of Peredox signal to cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio.

For epifluorescence experiments, the precise correspondence between Peredox signal and cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio is obtained from prior in vitro experiments where purified Peredox protein was incubated with known concentrations of NADH and NAD+, and the resulting fluorescence was measured (17). We compared the Peredox signal from our experiments to the signal from the in vitro experiments to obtain values of cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in hepatocytes. We adapted the equation from Hung and coworkers (17, 18), derived from the equilibrium constant for the LDH reaction, for a percent scale of normalized Peredox signal. For epifluorescence experiments in dissociated hepatocytes, we used the LDH equilibrium constant (Keq) at 37°C, yielding the following equation:

For epifluorescence experiments in liver slices, we used the LDH Keq at 35°C, yielding the following equation:

For 2p-FLIM experiments, the correspondence between Peredox lifetime and cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio is obtained from prior in vitro experiments where purified Peredox protein was incubated with LDH and known concentrations of lactate and pyruvate, and the resulting lifetime values were measured (28). The prior raw protein data (obtained in the same experimental setup) was reanalyzed in parallel with the liver slice data, to control for differences in the fits to lifetime histograms. The relationship between lifetime and cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio is obtained from fitting the lifetime data with the following Hill plot, using the LDH Keq at 35°C:

where Lifetimemax = 2.343 ns, Lifetimemin = 1.527 ns, K1/2 = 20.4 ns, and H = 1.774.

Throughout this paper, the term “cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio” specifically refers to the free cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio, which is the pool that is sensed by Peredox. A higher or increased cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio indicates a more reduced cytosolic redox state, and a lower or decreased cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio indicates a more oxidized cytosolic redox state. For convenience, the NADH/NAD+ ratio is reported as the inverse of the NAD+/NADH ratio (e.g., NADH:NAD+ = 1:200), given that cytosolic NAD+ far exceeds NADH in almost all conditions.

Data analysis.

Data analysis was performed using Excel 2010 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA). Data are shown as means ± SE. For dose-response curves, a Hill function was fit to the data using the Solver function in Excel. Statistical significance was assessed by Student’s t-test, with P < 0.05 considered significant. Figures were generated using Excel, PowerPoint 2010 (Microsoft), and Adobe Photoshop CS5 (Adobe, San Jose, CA).

RESULTS

Live cell imaging with Peredox reports cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in primary hepatocytes.

Peredox is a genetically encoded fluorescent sensor of cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio engineered by circular permutation of a green fluorescent protein to a bacterial protein (Rex) which binds NADH or NAD+ (17, 18). The structural conformation of Rex when bound to each species is transmitted to the green fluorescent protein, such that the NADH-bound form emits more fluorescence than the NAD+-bound form. Thus green fluorescence emitted by a cell expressing Peredox is directly dependent on the ratio of the two forms of the sensor (NADH- and NAD+-bound), which in turn is determined by the free NADH/NAD+ ratio in the cytosol. Live cell imaging with Peredox yields dynamic, real-time measurements of free cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in dissociated primary neurons and astrocytes in culture (17) and in acute brain slices (9, 28). This approach should in principle be applicable to hepatocytes and liver slices, offering important advantages over existing approaches to measure cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in the liver.

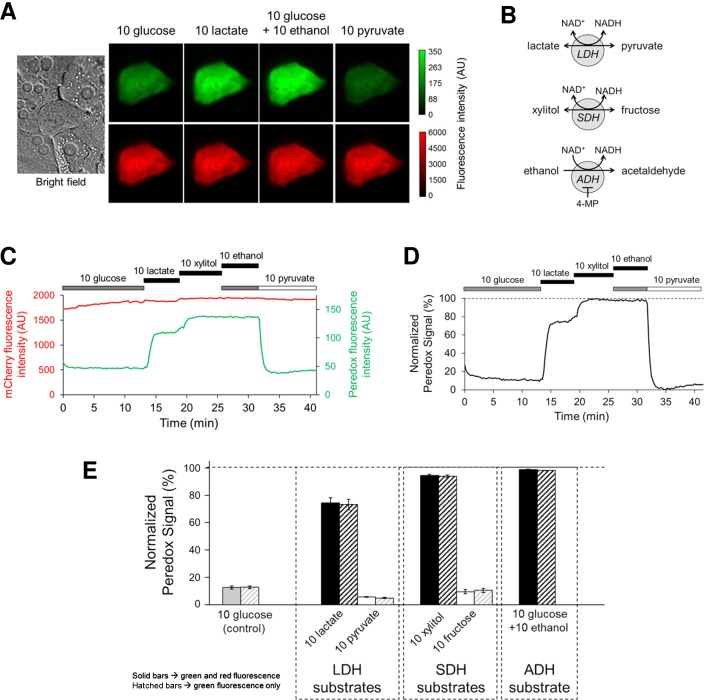

To investigate this, we first expressed Peredox-mCherry by transfection in dissociated rat hepatocytes in short-term culture (Fig. 1A), which are a convenient, widely used experimental model to study hepatocyte biology. We used wide-field epifluorescence microscopy in a flowing solution chamber to dynamically examine the cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio (as reported by Peredox fluorescence) of hepatocytes exposed to substrates of cytosolic dehydrogenases known to be highly expressed in hepatocytes (Fig. 1B). The green fluorescence of Peredox-mCherry is directly dependent on the cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio, while red fluorescence is unchanged and serves as a control for the level of sensor expression, allowing comparison between cells; thus Peredox signal is measured as green fluorescence divided by red fluorescence over time. For each cell, we drove Peredox signal to maximum and minimum values (“ceiling” and “floor,” respectively) to obtain a normalized Peredox signal with values between 0 and 100, allowing comparison between cells (Fig. 1, C and D). Values for cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio are then obtained by comparing the normalized Peredox signal in hepatocytes with that from prior experiments with purified Peredox protein and known NADH/NAD+ ratios (17, 18).

Fig. 1.

Peredox reports cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in dissociated rat hepatocytes. A: bright-field and epifluorescence images of cultured rat hepatocyte expressing Peredox-mCherry. B: cytosolic dehydrogenases of interest, with substrates. LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; SDH, sorbitol dehydrogenase; ADH, alcohol dehydrogenase. C and D: time course of Peredox-mCherry response in one hepatocyte exposed to substrates of cytosolic dehydrogenases. Fluorescence intensity of Peredox (green, at 405 nm excitation) and mCherry (red, at 578 nm excitation) was measured every 15 s (C). Peredox signal (green fluorescence over red fluorescence) is normalized to lowest value (“floor,” with 10 mM pyruvate) and highest value (“ceiling,” with 10 mM ethanol) and expressed as a percentage (0–100%) (D). Dividing green fluorescence by red fluorescence corrects Peredox response for small changes in sensor expression or cell shape during the time of the experiment, but is not essential. E: average Peredox response in hepatocytes (means ± SE, n = 9–43 hepatocytes). Solid bars were obtained using green and red fluorescence from Peredox-mCherry; hatched bars were obtained using green fluorescence only. All concentrations in mM.

Under control conditions (glucose present), rat hepatocytes exhibit a relatively low (oxidized) cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio (Fig. 1E). The ratio we obtained (NADH:NAD+ = 1:391 ± 32, n = 43 hepatocytes) compares favorably with previous indirect measurements obtained from lactate/pyruvate ratios in freeze-clamped rat liver (15, 38). These measurements are based on the assumption that the lactate/pyruvate couple is in equilibrium with the cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio via lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). As expected for mammalian cells in general, the ratio in hepatocytes reported by Peredox responds rapidly and reversibly to substrates of LDH: lactate increases it (NADH:NAD+ = 1:54 ± 6, n = 9 hepatocytes), whereas pyruvate decreases it (NADH:NAD+ = 1:568 ± 25, n = 41 hepatocytes). Importantly, the ratio also responds to substrates of other cytosolic dehydrogenases that are highly expressed in hepatocytes: sorbitol dehydrogenase (SDH) and alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH). For SDH, xylitol increases the ratio and fructose decreases it, whereas for ADH, ethanol increases the ratio. At a concentration of 10 mM, both xylitol (NADH:NAD+ = 1:18 ± 2, n = 15 hepatocytes) and ethanol (NADH:NAD+ = 1:7 ± 0.3, n = 43 hepatocytes) drive the ratio to higher (more reduced) values than lactate.

The initial version of Peredox (Peredox-mCherry) included a red fluorescent protein attached at the COOH terminus to normalize for sensor expression, but we have since found that normalization is similarly achieved by obtaining the “floor” and “ceiling” for each experiment from internal calibration steps, as described. Since Peredox protein expression does not significantly change during the time course of experiments (30–60 min), the additional red fluorophore is not needed. To confirm this, we reanalyzed the dissociated hepatocyte data using only the green fluorescence from Peredox-mCherry (obviating the red fluorescence), which yielded the same results (hatched bars in Fig. 1E). Following the design and characterization of the initial version of Peredox (17, 18), the Yellen laboratory designed a simpler Peredox version containing only the green fluorophore (9, 28). This version is more versatile because it enables simultaneous imaging with other sensors based on red fluorescent proteins.

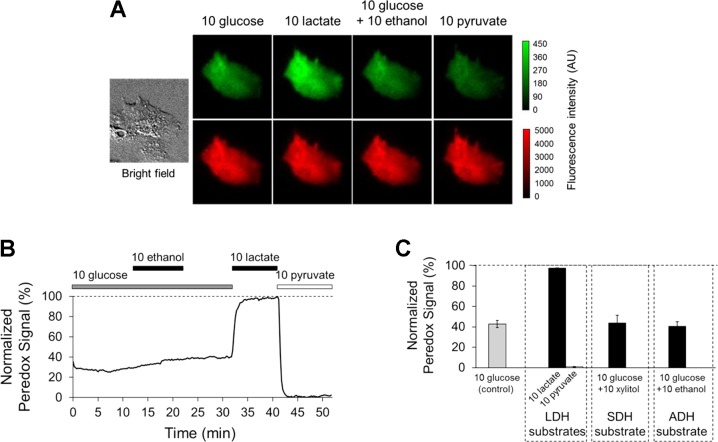

Peredox reports cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in HepG2 cells.

We used Peredox to examine cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in another convenient, widely used experimental hepatocyte model: HepG2 cells, a human hepatocyte-derived transformed cell line. As with rat hepatocytes, we expressed Peredox-mCherry in HepG2 cells by transfection (Fig. 2A) and carried out wide-field epifluorescence microscopy in a flowing solution chamber. The cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in HepG2 cells as reported by Peredox responds to LDH substrates (lactate and pyruvate), as expected (Fig. 2, B and C). However, HepG2 cells exhibit important differences with respect to primary hepatocytes. First, HepG2 cells exhibit a relatively high (reduced) cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio under control conditions (NADH:NAD+ = 1:136 ± 11, n = 33 cells). Second, HepG2 cells exhibit minimal responses to ethanol, consistent with known low levels of ADH expression in this cell line (40). Finally, we observed minimal responses to xylitol, suggesting that SDH is also expressed at low levels, although to our knowledge the expression of SDH in HepG2 cells has not been specifically examined. Overall, these results suggest that, compared with rat hepatocytes, HepG2 cells are a less suitable experimental model to investigate cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio.

Fig. 2.

Peredox reports cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in HepG2 cells. A: bright-field and epifluorescence images of HepG2 cell expressing Peredox-mCherry. B: time course of Peredox response in one HepG2 cell exposed to substrates of cytosolic dehydrogenases. Fluorescence was measured every 15 s. Peredox signal (green fluorescence over red fluorescence) is normalized to lowest value (“floor,” with 10 mM pyruvate) and highest value (“ceiling,” with 10 mM lactate) and expressed as a percentage (0–100%). C: average Peredox response in HepG2 cells (means ± SE, n = 5–13 cells). All concentrations in mM.

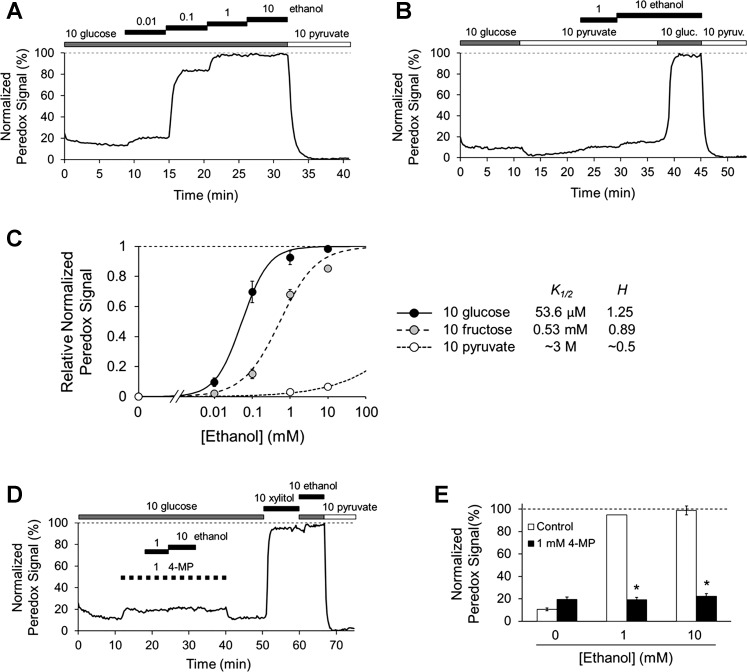

Ethanol oxidation by ADH robustly increases cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in rat hepatocytes.

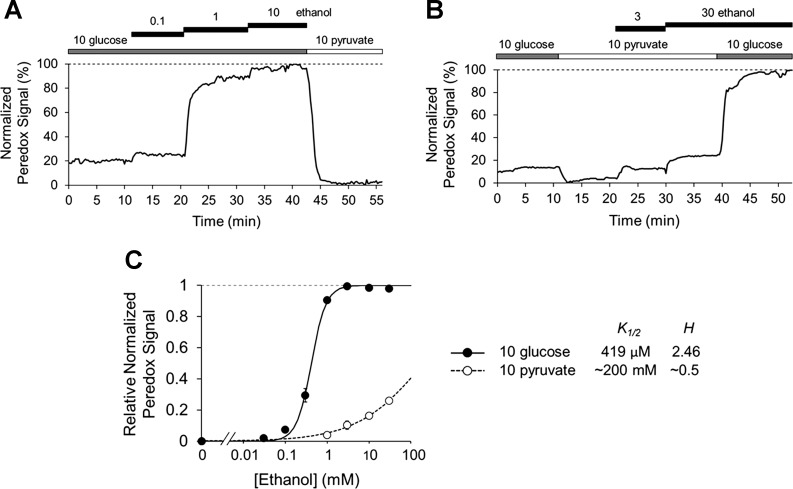

We examined in more detail the effects of ethanol on cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in rat hepatocytes. Ethanol causes a robust dose-dependent increase in cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio (Fig. 3, A and B) with an apparent half-maximal value (K1/2) of 68 ± 17 μM (n = 7 hepatocytes) (Fig. 3C). Ethanol at 1 mM yields essentially a maximal effect, consistent with perfused liver studies showing that the lactate/pyruvate ratio in the eluate saturates at ~1–2 mM ethanol (41). The effect of ethanol is prevented by the ADH inhibitor 4-methylpyrazole (4-MP) (Fig. 3, D and E), demonstrating that the increase in cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio is mediated by ADH.

Fig. 3.

Ethanol oxidation by alcohol dehydrogenase increases cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in rat hepatocytes. A and B: effects of ethanol on cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in cultured rat hepatocytes in the presence of 10 mM glucose (A) or 10 mM pyruvate (B). C: Hill plot for ethanol effect. Data points are means ± SE for n = 6–8 hepatocytes. Lines are least-squares fits to data points (values for slope H and half-maximal concentration K1/2 are shown at right). D: time course showing effect of ADH inhibitor 4-methylpyrazole (4-MP) on ethanol response in one hepatocyte. E: average 4-MP data in hepatocytes (means ± SE, n = 7–8 hepatocytes, *P < 5 × 10−9 vs. control). All concentrations in mM unless otherwise indicated.

Since cytosolic dehydrogenases have access to the same pool of cytosolic NADH/NAD+, the effects of ethanol on the ratio should be affected by the activity of other cytosolic dehydrogenases. Indeed, the effect of ethanol on cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio is mitigated by the presence of NAD+-generating substrates of either LDH (pyruvate) or SDH (fructose) (Fig. 3C). Pyruvate, in particular, causes a remarkable right-shift of the ethanol dose response. The K1/2 in 10 mM fructose was 580 ± 85 μM (n = 8 hepatocytes, P = 0.0002 vs. 10 mM glucose). The K1/2 in 10 mM pyruvate could not be reliably calculated from individual experiments for statistical analysis, but was estimated at ~3 M from the fit to the average data (n = 6 hepatocytes).

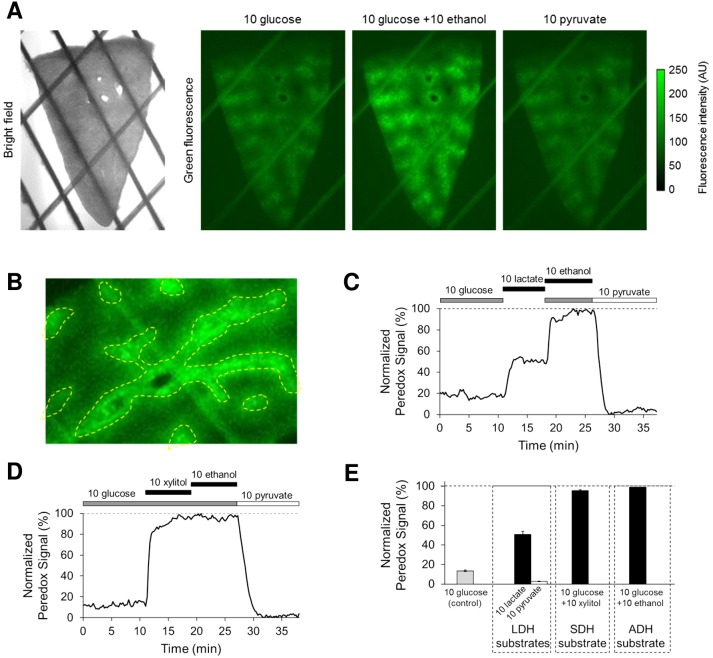

Peredox reports cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in mouse liver slices.

Liver diseases in humans tend to exhibit zonal distribution. In particular, FLD preferentially affects the centrilobular region (zone 3), where synthesis of fatty acids and triglyceride is highest (19, 20). To adequately examine the role of cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in the pathogenesis of FLD, it would be optimal to use an experimental system that, unlike dissociated hepatocytes, preserves liver architecture and zonal distribution of disease. To address this, we adapted live cell imaging with Peredox to acute liver slices from mice. AAV-encoded Peredox was injected via tail vein, and 200-µm liver slices were cut with a vibratome while submerged in ice-cold buffer. No agar embedding or tissue fixation was used. Slices were imaged in a flowing solution chamber with double perfusion (above and below the slice). For slice experiments, we used the simplified version of Peredox which contains the green fluorophore only.

We found that AAV-encoded Peredox delivered via tail-vein injection is broadly expressed in hepatocytes in liver slices, with preferential expression in zone 3 (Fig. 4, A and B). This pattern of expression is not unique to Peredox or fluorescent proteins: it is generally observed in mouse liver when proteins encoded by AAV capsid serotypes 8 or 9 are delivered via tail vein or portal vein (3, 7, 8). As expected, hepatocytes in liver slices exhibit a relatively low (oxidized) cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio as reported by Peredox (NADH:NAD+ = 1:416 ± 26, n = 53 slices from N = 18 mice) (Fig. 4, C–E). The ratio in slices also responds rapidly and reversibly to substrates of LDH, SDH, and ADH (Fig. 4, C and D). The preferential expression of Peredox in zone 3 facilitates identification of liver microanatomy in slices and allows for differential measurement of cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in zone 1 (the periportal region) vs. zone 3 (the centrilobular region). We found that the ratio under control conditions is very similar between zone 1 and zone 3 (NADH:NAD+ = 1:399 ± 22 vs. 1:365 ± 19, n = 17 slices from N = 9 mice). The ratio is slightly more reduced in zone 3, but the difference is not statistically significant (P = 0.225).

Fig. 4.

Peredox epifluorescence reports cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in mouse liver slices. A: bright-field and epifluorescence images of mouse liver slice expressing Peredox (simpler construct with green fluorophore only). B: Peredox expression in liver slices is higher in the centrilobular region or zone 3 (bounded by yellow dotted line). Darker areas correspond to the periportal region or zone 1. C and D: time course of Peredox response in two separate liver slices exposed to substrates of cytosolic dehydrogenases. Fluorescence was measured every 15 s. Peredox signal (green fluorescence) is normalized to lowest value (“floor,” in 10 mM pyruvate) and highest value (“ceiling,” in 10 mM ethanol) and expressed as a percentage (0–100%). E: average Peredox response in liver slices (means ± SE, n = 9–53 slices from N = 18 mice). All concentrations in mM.

As in dissociated hepatocytes, ethanol dose-dependently increases cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in slices (Fig. 5, A and B). The ethanol dose response in slices is somewhat right-shifted compared with dissociated hepatocytes (K1/2 = 378 ± 23 μM, n = 21 slices from N = 9 mice) (Fig. 5C), but, as in dissociated hepatocytes, it saturates in the expected range (~1–2 mM) based on perfused liver studies (41). Generation of NAD+ by pyruvate via LDH also mitigates the effects of ethanol in slices, causing a marked right-shift of the ethanol dose-response curve (K1/2 estimated at ~200 mM based on the fit to the average data, n = 11 slices from N = 7 mice). Thus the slice preparation yields dynamic measurements of cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in hepatocytes in the context of metabolic zonation, providing a more physiologically relevant experimental model for the study of cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in the liver.

Fig. 5.

Ethanol oxidation by alcohol dehydrogenase increases cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in mouse liver slices. A and B: effects of ethanol on cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in liver slices (assessed by epifluorescence imaging with Peredox) in the presence of 10 mM glucose (A) or 10 mM pyruvate (B). C: Hill plot for ethanol effect. Data points are means ± SE of n = 3–14 slices from N = 10 mice. Lines are least-squares fits (values for slope H and half-maximal concentration K1/2 are shown at right). All concentrations in mM unless otherwise indicated.

Peredox lifetime imaging reports cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in mouse liver slices.

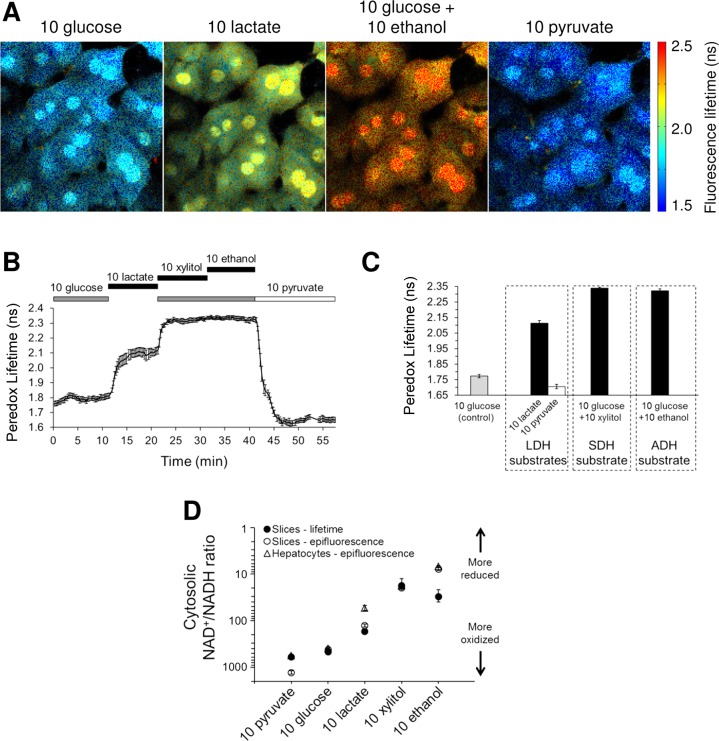

Our results thus far indicate that epifluorescence imaging with Peredox is a useful approach to measure cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in living hepatocytes. However, we decided to further validate the approach of live cell imaging with fluorescent biosensors in hepatocytes by carrying out two-photon fluorescence lifetime imaging (2p-FLIM) experiments with Peredox in liver slices. Fluorescence lifetime is the dwell time of a fluorescent protein in the excited state, i.e., the time between absorption of an excitation photon (or two photons, in the case of 2p-FLIM) and emission of a photon (43). Some fluorescent sensors exhibit a change in fluorescence lifetime upon analyte binding, in addition to a change in fluorescence intensity; the change in lifetime may be due to reduced quenching of the fluorophore in the analyte-bound configuration. Compared with epifluorescence (which measures fluorescence intensity), lifetime imaging is a more quantitative approach because it yields an absolute measurement of sensor state that is generally independent of sensor expression level or instrumentation (43). Peredox is amenable to 2p-FLIM because it exhibits a substantial increase in its lifetime when NAD+ is exchanged for NADH; thus an increase in Peredox lifetime indicates an increased (more reduced) cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio. 2p-FLIM is more technically challenging than epifluorescence imaging, but the Yellen laboratory has successfully developed an approach to carry out 2p-FLIM with Peredox in brain slices (9, 28). We thus applied the same approach to liver slices.

As expected, hepatocytes in mouse liver slices expressing Peredox exhibit a relatively low Peredox lifetime value under control conditions (1.77 ± 0.01 ns, n = 11 slices from N = 4 mice), which indicates a relatively oxidized cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio (NADH:NAD+ = 1:464 ± 16) (Fig. 6A). Peredox lifetime rapidly responds to substrates of LDH, SDH, and ADH in the expected manner: lactate, xylitol, and ethanol increase the lifetime, whereas pyruvate decreases it (Fig. 6, B and C). Either 10 mM xylitol or 10 mM ethanol are sufficient to achieve the maximum lifetime value (2.34 ns based on purified protein experiments), indicating a maximally reduced cytosolic ratio. The values for cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio obtained by 2p-FLIM are in close agreement with those obtained by epifluorescence imaging (Fig. 6D). Some divergence is observed at the extremes of cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio (ceiling and floor), which is due to the difficulty in obtaining precise values at the extremes since Peredox response “flattens out” at the extremes of the ratio (17), but there is close agreement in the more physiologically meaningful range of ratio values (for example, in the presence of glucose). The small difference in the 10 mM lactate values is likely due to the fact that ratio values from 2p-FLIM in the midportion of the range are slightly right-shifted compared with the ratio values from epifluorescence, with 2p-FLIM values being slightly more reduced; this is because lifetime measurements include low-occupancy states in the average. This quantitative difference between lifetime and ratiometric measurements is discussed in detail in the appendix to Mongeon et al. (28).

Fig. 6.

Peredox lifetime imaging reports cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in mouse liver slices. A: lifetime images of mouse liver slice expressing Peredox. Images are pseudocolored according to Peredox lifetime values (color scale bar at right shows range of lifetime values). B: time course of Peredox lifetime response in one mouse liver slice. Data points represent means ± SE of 9 hepatocytes in the imaging field. C: average Peredox lifetime response in liver slices (means ± SE of n = 8–11 slices from N = 4 mice). D: cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratios obtained in liver cells in the indicated conditions using live cell imaging with Peredox. For convenience, ratios are expressed as NAD+/NADH ratios, since NAD+ greatly exceeds NADH under most conditions. Data points are means ± SE of n = 8–11 slices from N = 4 mice (slices, lifetime), n = 9–53 slices from N = 18 mice (slices, epifluorescence), and n = 9–43 hepatocytes. All concentrations in mM.

DISCUSSION

In this study we describe and validate a new experimental approach to investigate free cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in experimental liver systems. We show that live cell imaging with the fluorescent biosensor Peredox yields dynamic, real-time measurements of cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in living, functioning rat hepatocytes and mouse liver slices. As described in introduction, use of Peredox overcomes several limitations of existing methods to assess cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio, in particular the destruction of cells or tissue under study; the inability to specifically detect the physiologically meaningful, smaller free pool of NADH/NAD+; and the confounding effects of the mitochondrial NAD(P)H pool. An additional advantage of Peredox is that it is well suited to lifetime imaging (2p-FLIM), which enables intrinsic quantitation of sensor state without need for internal normalization or calibration of each experiment (28, 43). We show that there is robust agreement between 2p-FLIM and epifluorescence measurements using Peredox in liver slices, particularly in the physiological range of cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio. This is valuable because, although 2p-FLIM is a more robust approach, epifluorescence is simpler and more accessible, and would likely be the choice of technique for most liver biology laboratories interested in using Peredox to investigate cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio.

Although our approach has several advantages over prior methods, for the purposes of its validation we have compared our results to those obtained with existing techniques. Our results are very similar to previous results using lactate/pyruvate ratios in freeze-clamped rat liver (15, 38). Both dissociated hepatocytes and liver slices exhibit a relatively low (oxidized) ratio under control conditions and respond rapidly and robustly to substrates of cytosolic dehydrogenases known to be highly expressed in hepatocytes: LDH, SDH, and ADH. We have used substrates of these cytosolic dehydrogenases as experimental tools to acutely manipulate hepatocyte cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in a predictable manner, to validate our sensor-based approach. Although characterization of these cytosolic dehydrogenases is not the primary focus of the paper, the behavior we observed with our approach is generally in agreement with previous work. Biochemical studies of ADH have yielded Michaelis-Menten constants for ethanol that are very similar to our K1/2 value for ethanol effect on cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in slices: 480 μM for rat liver ADH (4, 6), 420 μM for C57BL/10 mouse liver ADH (30), and 530 μM for perfused rat liver (41). The right-shifted dose response for ethanol in liver slices compared with dissociated hepatocytes may be due to different rates of ethanol oxidation, perhaps due to relative hypoxia within slices (13), or other factors such as ethanol diffusing into dissociated hepatocytes more readily. When steady-state conditions for ethanol metabolism are carefully maintained, the lactate/pyruvate ratio in perfused rat liver saturates at ~1 to 2 mM ethanol (41), which is in agreement with our results. Since cytosolic dehydrogenases have access to the same pool of NADH/NAD+ in the cytosol (39), the effects of ethanol on the ratio are mitigated by generation of NAD+ via other cytosolic dehydrogenases. The robust ability of LDH to compete with ADH in the reverse direction (pyruvate provided) suggests a preferential directionality of LDH in hepatocytes, given that in the forward direction (lactate provided) LDH appears to be less powerful than SDH or ADH. Indeed, rat liver LDH is ~30-fold faster in the reverse direction, and has a ~50-fold higher affinity for pyruvate in the reverse direction than for lactate in the forward direction (1). The activity of the malate-aspartate shuttle and the glycerol-3-phosphate shuttle could also mitigate the effects of lactate on the ratio by shuttling reducing equivalents into mitochondria.

An attractive aspect of the sensor-based approach is that it is well suited to liver slices, which, unlike dissociated hepatocytes, allow for preservation of hepatic microanatomy and metabolic zonation of hepatocytes. This would be particularly relevant to FLD, which preferentially affects the centrilobular (zone 3) region. Using live cell imaging with Peredox, cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio can be simultaneously examined in separate metabolic zones in slices. We found that cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio under control conditions in mouse liver slices is similar in the centrilobular region (zone 3) compared with the periportal region (zone 1). This is in agreement with previous studies using the indirect method of redox couples from intact liver, which have shown no significant difference between the two zones (2, 12). Whether there are zonal differences in the ratio in the context of FLD is an interesting question that can be explored with Peredox in slices. Although dissociated hepatocytes in culture are not in a microanatomic context and experience time-dependent loss of hepatocyte phenotype, the fact that they behave very similar to slices in our study (after ~2 days in culture) suggests that they are a useful experimental model for at least some aspects of NADH/NAD+ biology. HepG2 cells, on the other hand, show a higher (more reduced) ratio under control conditions and exhibit minimal response to ethanol, making them less attractive as an experimental model.

Imaging with Peredox in perfused liver or in vivo may ultimately prove a superior experimental system, but both pose nontrivial technical challenges to overcome. Until such approaches are developed, the slice preparation shows promise as a relatively intact system that is fairly accessible from a technical standpoint. Liver slices exhibit high activity of key enzymes of alcohol metabolism (including ADH), exhibit redox changes comparable to perfused livers, and accumulate triglyceride when incubated with alcohol (21). Although we have focused on cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in the present study, we expect our sensor-based approach to be broadly applicable to other intracellular metabolites of interest in liver biology. For example, genetically encoded fluorescent biosensors for measuring ATP/ADP ratio (37) and reduced/oxidized glutathione ratio (14) are already available, and should in principle be adaptable to live cell imaging in liver slices.

In summary, we have adapted the technique of live cell imaging with fluorescent biosensors to liver cells by using Peredox to investigate cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio in hepatocytes and liver slices. As reported by Peredox, the ratio responds rapidly and reversibly to substrates of cytosolic dehydrogenases that are highly expressed in hepatocytes, in particular ADH. Peredox yields similar results whether used with epifluorescence imaging (which is a relatively simple approach but which requires internal calibration) or lifetime imaging (which does not require internal calibration but is technically more complex), demonstrating the robustness and versatility of the approach. The ability to use Peredox in slices is particularly promising because slices allow preservation of hepatic microanatomy and metabolic zonation of hepatocytes, thus providing a more physiologically relevant experimental system. Live cell imaging with Peredox and other biosensors in experimental liver systems has the potential to yield novel insight into hepatic redox biology.

GRANTS

R. Masia is supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Training Grant NCI-T32-CA-09216 and by a Pinnacle Research Award from the AASLD Foundation. R. T. Chung is supported by NIH Grant DK-078772. C. Lahmann is supported by NIH Fellowship Award F32-NS-093784. G. Yellen is supported by NIH Director’s Pioneer Award DP1-EB-016985.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.M., J.L., R.T.C., M.L.Y., and G.Y. conceived and designed research; R.M., W.J.M., and C.L. performed experiments; R.M. and C.L. analyzed data; R.M. and C.L. interpreted results of experiments; R.M. and C. L. prepared figures; R.M. drafted manuscript; W.J.M., C.L., J.L., R.T.C., M.L.Y., and G.Y. edited and revised manuscript; R.M., W.J.M., C.L., J.L., R.T.C., M.L.Y., and G.Y. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Univ. of Pennsylvania Vector Core (Philadelphia, PA) and the Boston Children's Hospital Viral Vector Core (Boston, MA) for the packaging and production of adeno-associated viruses used in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson SR, Florini JR, Vestling CS. Rat liver lactate dehydrogenase. III. Kinetics and specificity. J Biol Chem 239: 2991–2997, 1964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baraona E, Jauhonen P, Miyakawa H, Lieber CS. Zonal redox changes as a cause of selective perivenular hepatotoxicity of alcohol. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 18, Suppl 1: 449–454, 1983. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(83)90216-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bell P, Wang L, Gao G, Haskins ME, Tarantal AF, McCarter RJ, Zhu Y, Yu H, Wilson JM. Inverse zonation of hepatocyte transduction with AAV vectors between mice and non-human primates. Mol Genet Metab 104: 395–403, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bosron WF, Crabb DW, Li TK. Relationship between kinetics of liver alcohol dehydrogenase and alcohol metabolism. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 18, Suppl 1: 223–227, 1983. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(83)90175-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corey KE, Kaplan LM. Obesity and liver disease: the epidemic of the twenty-first century. Clin Liver Dis 18: 1–18, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2013.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crabb DW, Bosron WF, Li TK. Steady-state kinetic properties of purified rat liver alcohol dehydrogenase: application to predicting alcohol elimination rates in vivo. Arch Biochem Biophys 224: 299–309, 1983. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(83)90213-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dane AP, Cunningham SC, Graf NS, Alexander IE. Sexually dimorphic patterns of episomal rAAV genome persistence in the adult mouse liver and correlation with hepatocellular proliferation. Mol Ther 17: 1548–1554, 2009. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dane AP, Wowro SJ, Cunningham SC, Alexander IE. Comparison of gene transfer to the murine liver following intraperitoneal and intraportal delivery of hepatotropic AAV pseudo-serotypes. Gene Ther 20: 460–464, 2013. doi: 10.1038/gt.2012.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Díaz-García CM, Mongeon R, Lahmann C, Koveal D, Zucker H, Yellen G. Neuronal stimulation triggers neuronal glycolysis and not lactate uptake. Cell Metab 26: 361–374.e4, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Domschke S, Domschke W, Lieber CS. Hepatic redox state: attenuation of the acute effects of ethanol induced by chronic ethanol consumption. Life Sci 15: 1327–1334, 1974. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(74)90314-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gariani K, Menzies KJ, Ryu D, Wegner CJ, Wang X, Ropelle ER, Moullan N, Zhang H, Perino A, Lemos V, Kim B, Park Y-K, Piersigilli A, Pham TX, Yang Y, Ku CS, Koo SI, Fomitchova A, Cantó C, Schoonjans K, Sauve AA, Lee J-Y, Auwerx J. Eliciting the mitochondrial unfolded protein response by nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide repletion reverses fatty liver disease in mice. Hepatology 63: 1190–1204, 2016. doi: 10.1002/hep.28245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghosh AK, Finegold D, White W, Zawalich K, Matschinsky FM. Quantitative histochemical resolution of the oxidation-reduction and phosphate potentials within the simple hepatic acinus. J Biol Chem 257: 5476–5481, 1982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grunnet N, Thieden HI, Quistorff B, Devreux M, Vialle J, Anthonsen T. Metabolism of 1-3H-ethanol by isolated liver cells. Time-course of the transfer of tritium from R,S-1-3H-ethanol to lactate and beta-hydroxybutyrate. Acta Chem Scand B 30: 345–352, 1976. doi: 10.3891/acta.chem.scand.30b-0345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gutscher M, Pauleau A-L, Marty L, Brach T, Wabnitz GH, Samstag Y, Meyer AJ, Dick TP. Real-time imaging of the intracellular glutathione redox potential. Nat Methods 5: 553–559, 2008. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guynn RW, Pieklik JR. Dependence on dose of the acute effects of ethanol on liver metabolism in vivo. J Clin Invest 56: 1411–1419, 1975. doi: 10.1172/JCI108222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hijmans BS, Grefhorst A, Oosterveer MH, Groen AK. Zonation of glucose and fatty acid metabolism in the liver: mechanism and metabolic consequences. Biochimie 96: 121–129, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hung YP, Albeck JG, Tantama M, Yellen G. Imaging cytosolic NADH-NAD(+) redox state with a genetically encoded fluorescent biosensor. Cell Metab 14: 545–554, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hung YP, Yellen G. Live-cell imaging of cytosolic NADH-NAD+ redox state using a genetically encoded fluorescent biosensor. Methods Mol Biol 1071: 83–95, 2014. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-622-1_7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jungermann K, Kietzmann T. Zonation of parenchymal and nonparenchymal metabolism in liver. Annu Rev Nutr 16: 179–203, 1996. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.16.070196.001143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katz NR. Metabolic heterogeneity of hepatocytes across the liver acinus. J Nutr 122, Suppl: 843–849, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klassen LW, Thiele GM, Duryee MJ, Schaffert CS, DeVeney AL, Hunter CD, Olinga P, Tuma DJ. An in vitro method of alcoholic liver injury using precision-cut liver slices from rats. Biochem Pharmacol 76: 426–436, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kosenko EA, Kaminsky YG. A comparison between effects of chronic ethanol consumption, ethanol withdrawal and fasting in ethanol-fed rats on the free cytosolic NADP+/NADPH ratio and NADPH-regenerating enzyme activities in the liver. Int J Biochem 17: 895–902, 1985. doi: 10.1016/0020-711X(85)90173-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lieber CS. Alcoholic fatty liver: its pathogenesis and mechanism of progression to inflammation and fibrosis. Alcohol 34: 9–19, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lieber CS, Schmid R. Stimulation of hepatic fatty acid synthesis by ethanol. Am J Clin Nutr 9: 436–438, 1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loomba R, Sanyal AJ. The global NAFLD epidemic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 10: 686–690, 2013. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mascord D, Rogers J, Smith J, Starmer GA, Whitfield JB. Effect of diet on [lactate]/[pyruvate] ratios during alcohol metabolism in man. Alcohol Alcohol 24: 189–191, 1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCarty WJ, Usta OB, Yarmush ML. A microfabricated platform for generating physiologically-relevant hepatocyte zonation. Sci Rep 6: 26868, 2016. doi: 10.1038/srep26868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mongeon R, Venkatachalam V, Yellen G. Cytosolic NADH-NAD(+) redox visualized in brain slices by two-photon fluorescence lifetime biosensor imaging. Antioxid Redox Signal 25: 553–563, 2016. doi: 10.1089/ars.2015.6593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pologruto TA, Sabatini BL, Svoboda K. ScanImage: flexible software for operating laser scanning microscopes. Biomed Eng Online 2: 13, 2003. doi: 10.1186/1475-925X-2-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rex DK, Bosron WF, Li TK. Purification and characterization of mouse alcohol dehydrogenase from two inbred strains that differ in total liver enzyme activity. Biochem Genet 22: 115–124, 1984. doi: 10.1007/BF00499291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salaspuro MP, Mäenpää PH. Influence of ethanol on the metabolism of perfused normal, fatty and cirrhotic rat livers. Biochem J 100: 768–778, 1966. doi: 10.1042/bj1000768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salaspuro MP, Shaw S, Jayatilleke E, Ross WA, Lieber CS. Attenuation of the ethanol-induced hepatic redox change after chronic alcohol consumption in baboons: metabolic consequences in vivo and in vitro. Hepatology 1: 33–38, 1981. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840010106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schleicher J, Tokarski C, Marbach E, Matz-Soja M, Zellmer S, Gebhardt R, Schuster S. Zonation of hepatic fatty acid metabolism - The diversity of its regulation and the benefit of modeling. Biochim Biophys Acta 1851: 641–656, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.von Schönfels W, Patsenker E, Fahrner R, Itzel T, Hinrichsen H, Brosch M, Erhart W, Gruodyte A, Vollnberg B, Richter K, Landrock A, Schreiber S, Brückner S, Beldi G, Sipos B, Becker T, Röcken C, Teufel A, Stickel F, Schafmayer C, Hampe J. Metabolomic tissue signature in human non-alcoholic fatty liver disease identifies protective candidate metabolites. Liver Int 35: 207–214, 2015. doi: 10.1111/liv.12476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shin S, Park J, Li Y, Min KN, Kong G, Hur GM, Kim JM, Shong M, Jung M-S, Park JK, Jeong K-H, Park MG, Kwak TH, Brazil DP, Park J. β-Lapachone alleviates alcoholic fatty liver disease in rats. Cell Signal 26: 295–305, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shin SY, Kim TH, Wu H, Choi YH, Kim SG. SIRT1 activation by methylene blue, a repurposed drug, leads to AMPK-mediated inhibition of steatosis and steatohepatitis. Eur J Pharmacol 727: 115–124, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tantama M, Martínez-François JR, Mongeon R, Yellen G. Imaging energy status in live cells with a fluorescent biosensor of the intracellular ATP-to-ADP ratio. Nat Commun 4: 2550, 2013. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Veech RL, Eggleston LV, Krebs HA. The redox state of free nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide phosphate in the cytoplasm of rat liver. Biochem J 115: 609–619, 1969. doi: 10.1042/bj1150609a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vind C, Grunnet N. Interaction of cytoplasmic dehydrogenases: quantitation of pathways of ethanol metabolism. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 18, Suppl 1: 209–213, 1983. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(83)90173-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wolfla CE, Ross RA, Crabb DW. Induction of alcohol dehydrogenase activity and mRNA in hepatoma cells by dexamethasone. Arch Biochem Biophys 263: 69–76, 1988. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(88)90614-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yao CT, Lai CL, Hsieh HS, Chi CW, Yin SJ. Establishment of steady-state metabolism of ethanol in perfused rat liver: the quantitative analysis using kinetic mechanism-based rate equations of alcohol dehydrogenase. Alcohol 44: 541–551, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yasuda R, Harvey CD, Zhong H, Sobczyk A, van Aelst L, Svoboda K. Supersensitive Ras activation in dendrites and spines revealed by two-photon fluorescence lifetime imaging. Nat Neurosci 9: 283–291, 2006. doi: 10.1038/nn1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yellen G, Mongeon R. Quantitative two-photon imaging of fluorescent biosensors. Curr Opin Chem Biol 27: 24–30, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2015.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]