Abstract

Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndMT) is a process in which endothelial cells lose polarity and cell-to cell contacts, and undergo a dramatic remodeling of the cytoskeleton. It has been implicated in initiation and progression of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). However, the characteristics of cells which have undergone EndMT cells in vivo have not been reported and so remain unclear. To study this, sugen5416 and hypoxia (SuHx)-induced PAH was established in Cdh5-Cre/Gt(ROSA)26Sortm4(ACTB-tdTomato,EGFP)Luo/J double transgenic mice, in which GFP was stably expressed in pan-endothelial cells. After 3 wk of SuHx, flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry demonstrated CD144-negative and GFP-positive cells (complete EndMT cells) possessed higher proliferative and migratory activity compared with other mesenchymal cells. While CD144-positive and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA)-positive cells (partial EndMT cells) continued to express endothelial progenitor cell markers, complete EndMT cells were Sca-1-rich mesenchymal cells with high proliferative and migratory ability. When transferred in fibronectin-coated chamber slides containing smooth muscle media, α-SMA robustly expressed in these cells compared with cEndMT cells that were grown in maintenance media. Demonstrating additional paracrine effects, conditioned medium from isolated complete EndMT cells induced enhanced mesenchymal proliferation and migration and increased angiogenesis compared with conditioned medium from resident mesenchymal cells. Overall, these findings show that EndMT cells could contribute to the pathogenesis of PAH both directly, by transformation into smooth muscle-like cells with higher proliferative and migratory potency, and indirectly, through paracrine effects on vascular intimal and medial proliferation.

Keywords: cell transformation, endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition, paracrine effects, pulmonary arterial hypertension, vascular remodeling

pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is characterized by a spectrum of structural changes in the pulmonary arteries: intimal proliferation, medial hypertrophy, and adventitial fibrosis (30). Although the primary trigger of PAH is still unknown, pulmonary vascular endothelial cells (PVECs), which are located in the innermost intimal layer, are suspected to be a key initiator of remodeling, since they are directly exposed to the bloodflow, circulating factors, and oxygenation (22). Accumulating evidence suggests that endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndMT) plays a pivotal role in initiation and progression of this disease (12, 14, 24, 30). EndMT describes a process in which endothelial cells lose their endothelial cell phenotype/cell surface markers and gain a mesenchymal or smooth muscle cell phenotype (2, 29, 38). EndMT was initially studied in the context of embryonic heart valve formation (17). In addition to its role in development, however, EndMT can initiate pathological tissue fibrosis in response to persistent damage and inflammation. Recent studies have provided convincing experimental evidence that EndMT occurs in the setting of PAH in both humans and animal models (12, 14, 24, 25).

However, it could be argued that EndMT is a secondary phenomenon in the PAH-remodeled pulmonary vasculature, without significant clinical or pathological relevancy (30). Immunohistochemical analyses of lungs from patients with systemic sclerosis-associated PAH and from the Sugen+hypoxia (SuHx) murine model revealed the presence of endothelial marker/α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) double positive transitioning cells in ~5% of PVECs (8). This prevalence might be too low to drive the pathogenesis of PAH. We still need to examine how EndMT contributes to the pathogenesis of PAH.

One problem is that, once endothelial cell markers are lost, the cells cannot be distinguished from other mesenchymal cells (30). Most previous reports identified EndMT cells as α-SMA double positive endothelial cells (8, 20, 24), which were defined as partial EndMT (pEndMT) cells (32, 36), since they still retained endothelial markers. pEndMT cells in PAH were reported to have prominent proliferative activity, and a role for pEndMT in neointimal thickening has been suggested. Similarly, we recently reported microvascular endothelial cells transitioning into mesenchymal cells (pEndMT cells) in response to lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury, which led them to become proliferative endothelial progenitor-like cells (32). However, evidence is lacking about the features of complete EndMT (cEndMT) cells in PAH. Qiao et al. (23) first reported the presence of cEndMT cells in PAH by using endothelial lineage tracking, but they mainly evaluated the presence of cEndMT cells by immunohistochemistry, and there have been no reports to the best of our knowledge that evaluated their function or characteristics when they are isolated from in vivo.

In the present study, we generated Cdh5-Cre/CAG-GFP double transgenic (Cdh5-Cre/GFP) mice, in which green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression stably labels the Cdh5 promoter-activated cells. In a murine study with the SuHx PAH model, we aimed to identify the presence of both pEndMT cells and cEndMT cells and to investigate changes in these two cells. In addition, we isolated cEndMT cells from the lungs of SuHx mice and tested our hypothesis that cEndMT cells contribute to the pathogenesis of PAH with their direct transformation into proliferative smooth muscle-like cells and paracrine effect on proliferation in other mesenchymal and endothelial cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Genetic lineage marking.

We generated double transgenic mice with endothelial genetic lineage marking by intercrossing vascular endothelial-cadherin (Cdh5) Cre (1) with mTomato/mGFP floxed dual fluorescent Cre reporter mice (19).

Mouse model of PAH.

Fifteen- to twenty-week-old female Cdh5-Cre/GFP mice were continuously exposed to 10% oxygen and administered once weekly SU5416 (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN) at 20 mg/kg body wt per dose for 3 wk (SuHx mice), and control mice were injected with the same volume of vehicle alone, as previously described (3). All animal experiments were conducted under protocols approved by the Review Board for animal experiments of Chiba University and the Intramural Animal Care and Use Committee at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Fluorescent immunohistochemistry and immunocytochemistry.

For immunohistochemistry staining, slides were processed and stained as described before (32). Primary antibodies used in immunohistochemistry were anti-VE-cadherin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX), anti-GFP (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), and anti-α-SMA (Dako, Santa Clara, CA) and for immunocytochemistry (ICC), anti-α-SMA (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Lung single cell suspension.

At the time of harvest, the lungs were perfused blood free with 30 ml of PBS containing 10 U/ml heparin (Novo-Heparin, Mochida, Tokyo, Japan) from the right ventricle and then minced and digested in an enzyme cocktail of DMEM (Sigma) containing 1% BSA (Wako, Osaka, Japan), 2 mg/ml collagenase (Wako), 100 µg/ml DNase (Wako), and 2.5 mg of Dispase II (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) at 37°C for 60 min and then meshed through a 100-µm nylon cell strainer.

Flow cytometry of lung cells.

For flow cytometry (FCM) staining, mouse lung cells were processed and stained as described before (21, 32). Primary antibodies used in immunohistochemistry were primary antibodies used in FCM: anti-CD144-PE/Cy7 (BioLegend), anti-CD45-Alexa 700 (BioLegend), anti-CD326-PerCP/Cy5.5 (BioLegend), biotin anti-CD133 (BioLegend), biotin anti-CD34 (BioLegend), biotin anti-CD117/c-kit-APC (BioLegend), anti-CD90-APC (BioLegend), anti-CD44-APC (BioLegend), anti-CD105-APC (BioLegend), anti-Sca-1-APC (BioLegend), anti-α-SMA (Thermo Scientific), and anti-S100A4 (Abcam). Secondary antibodies used in FCM were streptavidin-APC antibodies (BioLegend) and anti-rabbit IgG-PE (BioLegend). To detect proliferating cells, bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU; APC flow kit; BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA) was used for staining intracellular BrdU according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Cell fluorescence was measured using a FACSCantoTM II instrument (Becton-Dickinson, San Jose, CA) and analyzed employing FlowJo software (Tree Star, San Carlos, CA).

Isolation of mouse pulmonary vascular endothelial cells, mesenchymal cells, and cEndMT cells.

Mouse PVECs were defined as CD144+/CD45−/CD326− cells, cEndMT cells as GFP+/CD144−/CD45−/CD326cells, and non-endothelium-derived mesenchymal cells (NEMCs) as GFP−/CD144−/CD45−/CD326 cells. Each cell type was sorted using the BD FACS Aria II cell sorter as previously reported (27). Propidium iodide (PI) (0.5 μg/ml, Thermo Scientific) staining was used to exclude dead cells.

Cell culture.

PVECs, NEMCs, and cEndMT cells were isolated from SuHx mouse lungs. Isolated PVECs were cultured in endothelial cell basal medium-2 (EBM-2; Lonza, Walkersville, MD) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Logan, UT) and endothelial cell growth medium-2 (EGM-2; SingleQuots, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Isolated NEMCs and cEndMT cells were maintained in α-modified minimum essential medium (α-MEM; Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% FBS, l-glutamine, and penicillin-streptomycin. For the culture of smooth muscle cell differentiation, cells were transferred to fibronectin-coated chamber slides containing 1 ml of bronchial smooth muscle basal medium supplemented with epidermal growth factor, basic-fibroblast growth factor, 5%FBS, insulin, and antimicrobial agents, as followed by the published protocol (31). All cells were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. The medium was exchanged every other day.

Collection of conditioned medium.

Isolated NEMCs and cEndMT cells were cultured in basic α-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS, l-glutamine, and penicillin-streptomycin until 70% confluence. The culture medium was then replaced with serum-free DMEM, and the cells were incubated for an additional 24 h. The complete supernatant was collected and filtered through 0.2-µm filters to remove cellular debris; they are designated EndMT cells-conditioned medium (EndMT-CM) and NEMCs-NEMCs-CM. They were collected between passages III and V.

Cell migration assay.

The differences in migration of cells were evaluated using the Oris Cell Migration Assay (Platypus Technologies, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's protocol. In brief, isolated cEndMT cells and NEMCs from mouse lungs were grown to 90% confluence before removal by trypsinization, resuspension in appropriate medium, and seeding into Oris Pro Collagen 96-well plates with an Oris cell seeding stopper to restrict cell seeding to the outer regions of the wells. The plates were seeded with 300,000 cells in 100 µl of appropriate medium per well. The seeded plates were incubated for 24 h at 37°C in 5% CO2 to allow cell attachment, and the stoppers were then removed to create a 2-mm diameter detection zone into which cells could migrate. After removal of the stoppers, the 96-well plates were incubated for 48 h at 37°C in 5% CO2 to allow time for migration, and the number of cells that had migrated into the detection zone was determined.

Tube formation assay.

Isolated PVECs suspended in EBM-2 supplemented with single aliquots of 10% FBS EGM-2 MV (Lonza) were seeded at a cell density of 4×105 cells/well into 200 µl/well MatrigelTM (BD)-coated chamber slides. These were examined for network formation under microscope.

qRT-PCR analysis.

Total RNA from CD31+/CD45− cells was isolated with Nucleo Spin RNA XS (Macherey Nagel & Co. KG, Diiren, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was subjected to RT-PCR with SuperScript VILO (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and single-stranded cDNA was synthesized. The resultant cDNA samples were subjected to PCR for amplification using an ABI Prism 7300 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). Specific primers and probes were designed using the web software of Universal ProbeLibrary Assay Design Center (Roche Applied Science). The CT value of each sample was normalized with Hprt1 as the endogenous control gene, and the relative expression level was calculated using the 2(−ΔΔCT) method.

Statistical analysis.

Values are shown as means ± SE unless otherwise described, or median (25–75th %ile). The results were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney test for comparison between any two groups and by nonparametric equivalents of ANOVA for multiple comparisons. GraphPad Prism software (version 6.03; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) was used to analyze the data. The level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Generation of Cdh5-Cre/GFP double-transgenic mice.

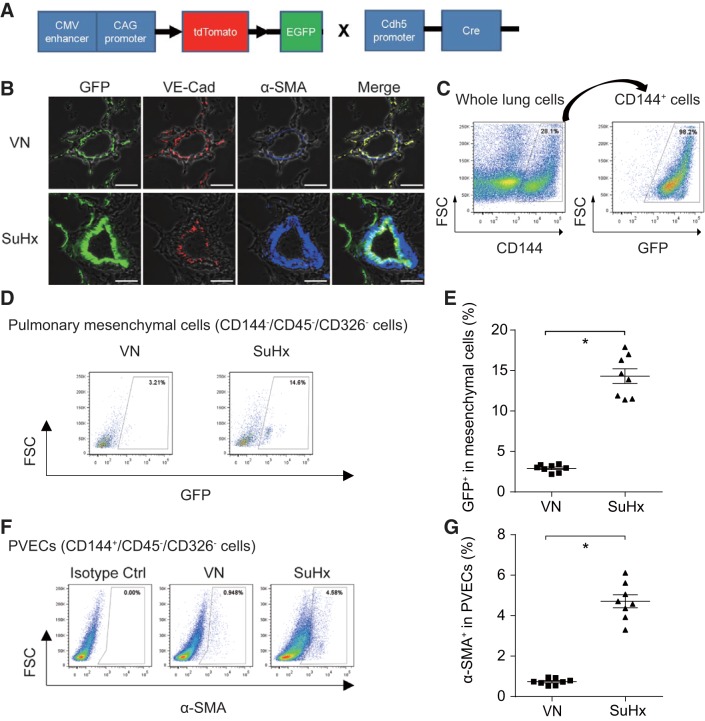

To enable endothelial fate mapping in vivo, dual fluorescent Cre recombinase reporter mice, mTomato/mGFP, were intercrossed with transgenic Cdh5-Cre driver mice (Fig. 1A). Immunohistochemistry staining showed the fidelity of Cdh5-Cre-directed endothelial genetic lineage marking; VE-cadherin immunostaining colocalized over green endothelial genetic lineage-marked cells in control mice (Fig. 1B). FCM analyses also revealed that GFP colocalized with CD144/VE-cadherin-positive cells in control mice (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Generation of Cdh5-Cre/GFP double transgenic mice and endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndMT) in sugen5416/hypoxia (SuHx)-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) model. A: schematic description of gene constructs in Cdh5-Cre/GFP mice. B: triple immunostaining for GFP (green), VE-cadherin (red), and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA; blue) was performed for lung tissues from control and SuHx mice. Scale bars, 50 μm. VN, vehicle + normoxia; SuHx, sugen + hypoxia. C: representative flow cytometry (FCM) panel with CD144+-gated whole lung cells and GFP+-gated CD144+ cells. D: representative FCM panels with GFP+-gated mesenchymal cells (CD144−/CD45−/CD326− cells) are shown. E: percentage of GFP+-gated mesenchymal cells significantly increased in SuHx-treated mice, indicating complete EndMT was observed in PAH model (*P < 0.05, n = 8). Values are means ± SE. F: representative FCM panels with α-SMA+-gated pulmonary vascular endothelial cells (PVECs: CD144+/CD45−/CD326− cells). G: percentage of α-SMA+-gated PVECs significantly increased in SuHx-treated mice, indicating partial EndMT was observed in PAH model (*P < 0.05, n = 8). Values are means ± SE.

EndMT in SuHx-induced PAH.

To identify cEndMT cells, we performed triple-immunofluorescence staining of lung tissue sections with GFP, VE-cadherin, and α-SMA. Although GFP-positive cells did not colocalize over α-SMA-positive cells in control mice, some GFP-positive cells, which did not colocalize over VE-cadherin-positive cells, colocalized over α-SMA-positive cells in SuHx mice, indicating cEndMT (Fig. 1B). These results were also confirmed by FCM analyses. The percentage of GFP+ in mesenchymal cells (CD144−CD45−CD326− cells), which was identical to the percentage of cEndMT cells, was 14.3 ± 1.8% in SuHx mice, and it was significantly higher than that in control mice (Fig. 1, D and E).

Second, we evaluated the existence of pEndMT cells, which were dual positive with endothelial marker and mesenchymal marker. Using confocal microscopy, we observed that SuHx induces pEndMT cells in pulmonary vascular intima (Fig. 1B). Consistent with a previous report (8), FCM experiments revealed that the percentage of α-SMA-positive PVECs (CD144+CD45−CD326− cells) was significantly increased and reached ~5% in SuHx mice, indicating partial EndMT (Fig. 1, F and G).

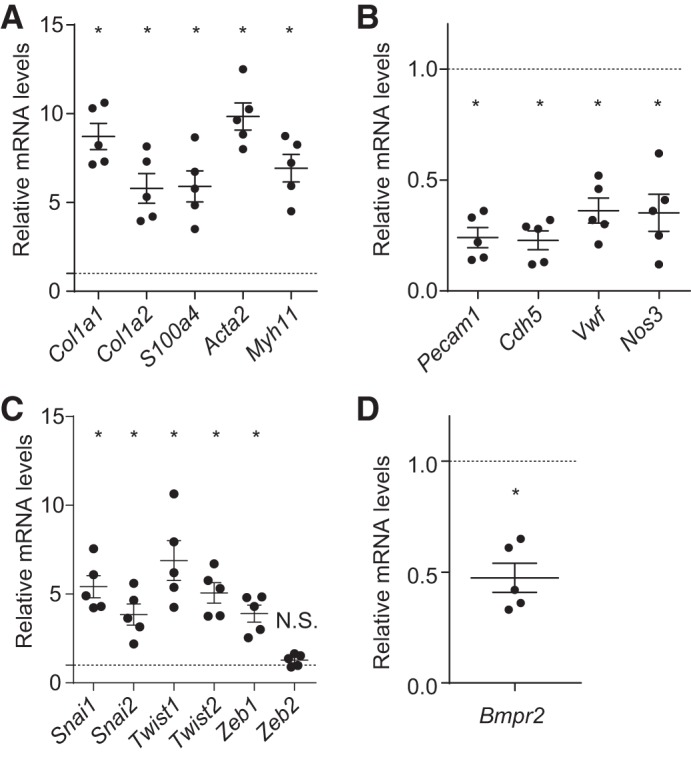

Gene expression pattern also supported EndMT in SuHx lungs.

We next isolated cEndMT cells (GFP+CD144−CD45−CD326−PI− cells) and PVECs (CD144+CD45−CD326−PI− cells) by FACS Aria and performed gene expression analysis by qRT-PCR. Gene expression results also supported the existence of EndMT; the expression of mesenchymal-specific markers significantly increased in cEndMT cells (Fig. 2A), the expression of endothelial-specific markers significantly decreased in cEndMT cells (Fig. 2B), and the expression of transcription factors related to EndMT was significantly increased in cEndMT cells (Fig. 2C). Interestingly, the gene expression of bone morphogenetic protein receptor type II (Bmpr2), whose mutation is linked to PAH (6, 7, 9), was significantly decreased in SuHx-induced cEndMT cells (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Gene expression in complete EndMT (cEndMT) cells. Gene expression analysis of isolated PVECs and cEndMT cells was performed by quantitative RT-PCR. The expression level in cEndMT cells is presented relative to the expression in PVECs (normalized to 1, dotted line). A: gene expression of mesenchymal-specific markers significantly increased in cEndMT cells. B: gene expression of endothelial-specific markers significantly decreased in cEndMT cells. C: gene expression of transcription factors related to EndMT was significantly increased in cEndMT cells. D: bone morphogenetic protein receptor type II (Bmpr2) expression was decreased in cEndMT cells (*P < 0.05, no. of mice from which cEndMT cells and PVECs were isolated = 5). Values are means ± SE.

Characterization of EndMT cells in SuHx mice.

As we previously reported that pEndMT cells in acute lung injury were enriched with endothelial progenitor cell (EPC) properties (32), we formed the hypothesis that EndMT is a dedifferentiating epiphenomenon; pEndMT suggests dedifferentiation to EPC-like cells, and cEndMT suggests dedifferentiation to much more mesenchymal-like cells and fibroblastic progenitor-like cells. We next planned to compare the expressions of cell surface stem/progenitor markers of cEndMT cells, pEndMT cells, and PVECs. In addition, we evaluated their proliferation and migration activities.

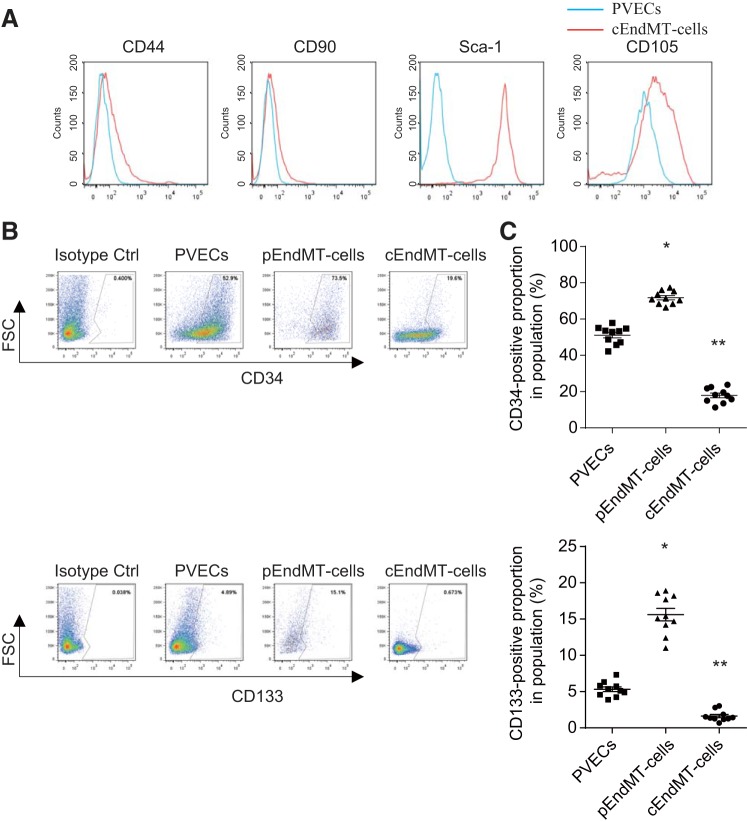

cEndMT cells are highly enriched in the Sca-1 positive cell fraction.

We compared expression of cell surface markers of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) on cEndMT cells and PVECs. Sca-1 and CD105 expression was higher in cEndMT cells (Fig. 3A). However, CD44 and CD90, which are also known as MSC markers, were not highly expressed in cEndMT cells.

Fig. 3.

Stem/progenitor cell marker expressions in SuHx-induced EndMT cells. A: FCM results are expressed as MFI in arbitrary units (x-axis) vs. number of cells (y-axis). Blue histograms represent endothelial cells; red histograms represent complete EndMT (cEndMT) cells. Percentage of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) markers such as CD105 and Sca-1 significantly increased in cEndMT cells (GFP+/CD144−/CD45−/CD326− cells) than in endothelial cells (CD144+/CD45−/CD326− cells). B: representative FCM panels with EPC marker+-gated partial EndMT cells and PVECs. C: percentage of endothelial progenitor cell (EPC) markers such as CD133 and c-kit significantly increased in partial EndMT (pEndMT) cells (α-SMA+/CD144+/CD45−/CD326− cells) than in PVECs (CD144+/CD45−/CD326− cells). Interestingly, expression of these markers significantly decreased in cEndMT cells (*P < 0.05 vs. PVECs, **P < 0.05 vs. PVECs and pEndMT cells, n = 10). Values are means ± SE.

Although Sca-1 was originally identified as a marker specifying murine hematopoietic stem cells, previous reports identified endogenous fibroblastic progenitor cells in the adult mouse lung as highly enriched in the CD31−/CD45−/Sca-1+ cell fraction (18). Since we defined cEndMT cells in the CD31−/CD45− cell fraction, these data might indicate that cEndMT cells are in the cell fraction where fibroblastic progenitor cells are highly enriched.

Some endothelial progenitor cell markers are highly expressed in pEndMT cells.

We next compared expression of cell surface markers of endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) on pEndMT cells, cEndMT cells, and PVECs. In agreement with our previous report (32), the expressions of EPC markers such as CD34 and CD133 were significantly higher in pEndMT cells than in PVECs. Expressions of these markers were reduced in cEndMT cells compared with either PVECs or pEndMT cells (Fig. 3, B and C).

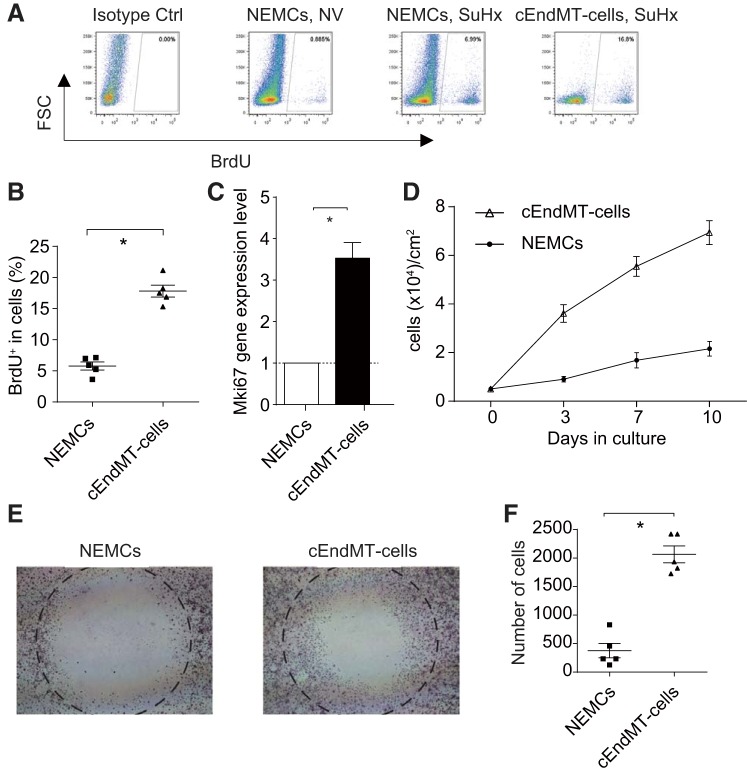

cEndMT cells showed higher proliferative activity than nonendothelial mesenchymal cells.

To compare the proliferative characteristics between cEndMT cells and nonendothelial mesenchymal cells (NEMCs), we performed BrdU incorporation experiments. FCM analyses revealed significantly higher percentages of BrdU-positive cEndMT cells compared with NEMCs in SuHx mice (Fig. 4, A and B). We next examined the gene expression of Mki67, a marker of proliferation, by qRT-PCR analyses of cEndMT cells and NEMCs. As shown in Fig. 4C, a significant increase (3.5-fold) of Mki67 was observed in cEndMT cells, which supported the result of the BrdU incorporation assay.

Fig. 4.

Characterization of SuHx-induced cEndMT cells. A: representative FCM panels with BrdU+-gated cEndMT cells and non-endothelium-derived mesenchymal cells (NEMCs). B: percentage of BrdU was significantly higher in cEndMT cells than in NEMCs in SuHx-induced PAH model (*P < 0.05, n = 5). C: expression of Mki67 was also significantly higher in cEndMT cells than in NEMCs (*P < 0.05, n = 5). Values are means ± SE. D: growth curves of cEndMT cells and NEMCs over 10 days in culture (n = 3). Values are means ± SE. E: migration of cEndMT cells and NEMCs. Cells that migrated into the circle were measured in a wound healing assay. F: wound healing assays demonstrated that cEndMT cells significantly enhanced migration activity compared with NEMCs (*P < 0.05, n = 5). Values are means ± SE.

In addition, seeded cEndMT cells proliferated faster than NEMCs when seeded at 5,000 cells/cm2 in 12-well plates and reached full confluence after 10 days (Fig. 4D).

cEndMT cells showed higher migration ability than NEMCs.

To compare the cell migration abilities of cEndMT cells and NEMCs, wound-healing assays were performed. Wound-healing assays demonstrated that cEndMT cells had significantly higher migratory ability than NEMCs (Fig. 4, E and F).

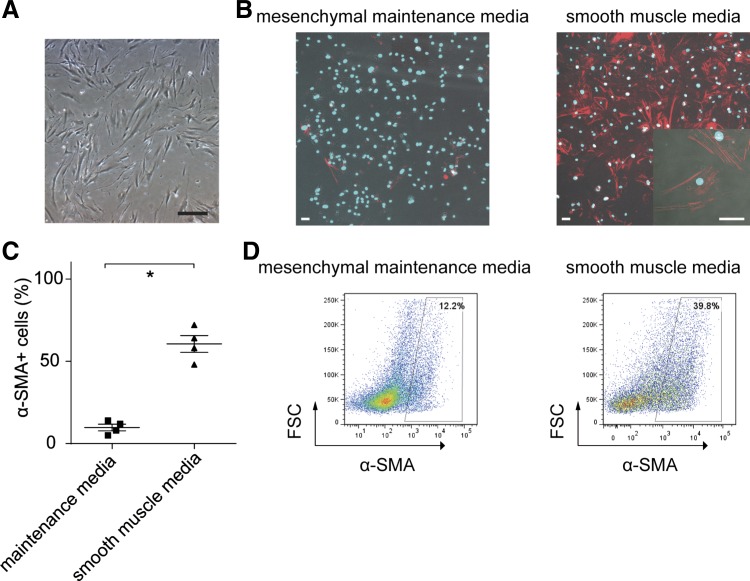

Differentiation of cEndMT cells.

Following collection of the lung cEndMT cells by cell sorting, the cells were plated in 30-mm dishes using α-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS. cEndMT cells displayed morphological features of mesenchymal cells: long, thin, and stellate (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

Differentiation of cEndMT cells. A: cEndMT cells proliferated in mesenchymal cell maintenance medium. Cells display morphological features of mesenchymal cells (long, thin, and stellate appearance). Scale bar, 50 μm. B: cultured in smooth muscle medium for 5 days, α-SMA was robustly expressed, wereas expression was small in mesenchymal maintenance medium. Red, α-SMA; Blue, DAPI. Scale bars, 50 μm. C: quantification of immunocytochemistry data (*P < 0.05, n = 4). Values are means ± SE. D: FCM analyses also revealed higher α-SMA expression in cEndMT cells cultured with smooth muscle medium.

To investigate whether cEndMT cells possessed the functional capability of transforming into smooth muscle cell populations, expanded cEndMT cells were transferred in fibronectin-coated chamber slides containing smooth muscle medium as previously reported (31). After 5 days, ICC staining and FCM analyses showed that α-SMA robustly expressed in these cells compared with cEndMT cells that were grown in maintenance medium (Fig. 5, B-D). These results might indicate that cEndMT cells in SuHx mice could transform into smooth muscle-like cells.

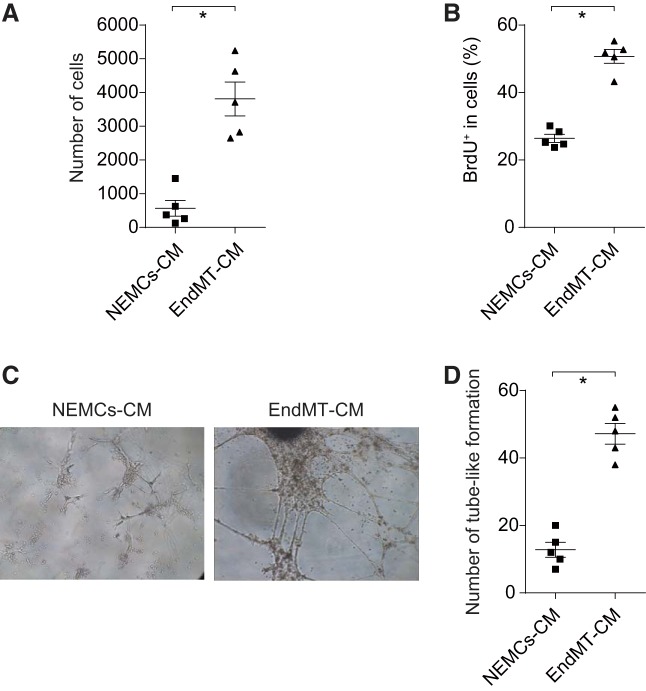

Paracrine effects of cEndMT cells to NEMCs.

Although we confirmed a potential direct contribution of cEndMT cells to the pathogenesis of PAH, we next investigated whether they had paracrine effects on the migration and proliferation of NEMCs.

To examine the effect of EndMT-CM paracrine factors in proliferative and migrative activity of NEMCs, we cultured NEMCs in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and treated with EndMT-CM (5%) or NEMCs-CM (5%). We observed a dramatic increase in wound closure when cells were treated with EndMT-CM (Fig. 6A). Similarly, EndMT-CM significantly increased BrdU incorporation in NEMCs (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Paracrine effect of cEndMT cells. A: cEndMT cells conditioned medium (EndMT-CM) or NEMCs-CM was added to isolated NEMCs (GFP−/CD144−/CD45−/CD326− cells), and wound healing assays were performed. EndMT-CM significantly promoted migration activity of NEMCs. Values are means ± SE (*P < 0.05, n = 5). B: BrdU incorporation was analyzed by FCM. Proliferation activity of mesenchymal cells was also upregulated by EndMT-CM. Values are means ± SE (*P < 0.05, n = 5). C: EndMT-CM was added to endothelial cells, and tube formation was investigated by microscopy. D: EndMT-CM significantly promoted angiogenesis (*P < 0.05, n = 5). Data are given as means of tube length in µm ± SE.

Second, to examine cEndMT paracrine effects in vascular endothelial proliferation, we cultured isolated PVECs with EndMT-CM (5%) or PVECs-CM (5%). Tube formation assays revealed that EndMT-CM significantly promoted angiogenesis (Fig. 6, C and D). These results might suggest that the cEndMT cell secretome plays a role in hyper proliferative PVECs and disordered angiogenesis, which are characteristics of vascular remodeling in PAH (33, 35).

DISCUSSION

Reversible and/or irreversible remodeling of the pulmonary vasculature is the cause of increased pulmonary artery pressure in PAH (26). There are several mechanisms underlying pulmonary vascular remodeling, which include pulmonary vasoconstriction, in situ thrombosis, intimal proliferation, and medial hypertrophy (10, 13). With regard to intimal proliferation and medial hypertrophy, the past few years have seen a remarkable increase in our knowledge of the presence and the signaling mechanisms of EndMT in PAH. Although EndMT appears to be an attractive therapeutic target in PAH, little is known about the innate characteristics of EndMT cells in PAH and their exact roles in PAH pathogenesis. In addition, we do not have any knowledge about the functional differences between mesenchymal transitioned cells (cEndMT cells) and transitioning cells (pEndMT cells), since most previous reports studied transitioning cells, which coexpressed both endothelial and mesenchymal markers.

We herein demonstrate the presence of both cEndMT and pEndMT in a PAH model by using endothelial-specific lineage mice. Similar to our previous report on an acute lung injury model (32), pEndMT cells in the PAH model were enriched for EPC markers such as CD133/Prom1 and CD34. However, cEndMT cells were negative for these markers but significantly expressed Sca-1 and CD105, both of which are known MSC markers. Of these two markers, Sca-1 expression was particularly enriched, reaching ~90% of cEndMT cells. Since CD31−CD45−Sca-1+ lung cells were reported to be highly enriched with mesenchymal progenitor cells (18), we next evaluated whether cEndMT cells in PAH have a MSC-like phenotype. Interestingly, our studies revealed that cEndMT cells had higher proliferative and migratory activity than other mesenchymal cells and could be differentiated into smooth muscle-like cells when grown in appropriate media. On the other hand, our data demonstrated that cEndMT cells in PAH did not highly express CD44 and CD90, and we could not differentiate cEndMT cells into osteoblasts, chondrocytes, or adipocytes, which are required abilities for MSCs. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report to isolate EndMT cells and to demonstrate their characteristics in a PAH model. Taken together with our previous report (32), it would be interesting to evaluate whether EndMT could be an endothelial dedifferentiating system. In our SuHx model, most vascular intima cells expressed α-SMA. Further investigation should be performed to elucidate whether both pEndMT and cEndMT cells contribute directly or indirectly to the neointima.

In addition, we investigated the paracrine effects of c-EndMT cells on other mesenchymal cells or endothelial cells. Although we proposed the mechanism of PAH pathogenesis from proliferating EndMT cells through dedifferentiation, we must keep in mind that the absolute number of EndMT cells is small, indicating that other effects also likely account for the pathogenesis. Therefore, identifying the functional role of EndMT cells’ secreted factors seems an important step to develop our knowledge about the functional role of EndMT in PAH. To do so, we used cEndMT-conditioned media and NEMC-conditioned media for culture of mesenchymal cells and endothelial cells. Our results indicate that cEndMT cells had a paracrine effect both for mesenchymal proliferation and migration and for endothelial angiogenic capacity. Although accumulating evidence has demonstrated that EndMT is involved in various diseases in organs such as lung, heart, and kidney (11, 15, 28, 37, 38), to our knowledge this study is the first to describe the paracrine effect of EndMT. It would be very interesting to investigate the secretome of these cells. Investigation for the exact paracrine molecules could lead to the development of PAH treatment.

Beyond the finding that EndMT directly and indirectly contributes to the pathogenesis of PAH, we also must address the question of whether cEndMT cells have potential for retransformation into normal endothelial cells. The process of pEndMT is thought to be reversible, but less is known about the reversibility of cEndMT (2). To date, MEndT, which appears to be an attractive therapeutic modality for PAH, has not been reported in any PAH model. Ubil et al. (34) elegantly revealed that MEndT contributes to cardiac neovascularization using Col1a2-CreERT:R26RtdTomato mice. We need further investigation to apply mesenchymal cell-lineage system to PAH model for the accurate evaluation of MEndT as new treatment target.

Another novel point in our study is that this is the first to report the gene expression of cEndMT cells. Reynolds et al. (25) revealed that deficiency in BMPR2-induced pEndMT, and targeted adenoviral BMPR2 gene delivery to the pulmonary vascular endothelium inhibited pEndMT and subsequently inhibited pulmonary vascular remodeling. Interestingly, our study demonstrated that Bmpr2 gene expression was significantly decreased in cEndMT cells vs. in PVECs. It might be of worth to test whether targeting the BMP pathway, as suggested by Morell (Long et al., 16), may promote MEndT in PAH.

There are several limitations to our study. First, we did not assess whether pEndMT leads to cEndMT. The mechanisms determining whether cells undergo complete or partial EndMT is a question that must be answered in the future. To determine this, we might need to isolate live pEndMT cells. Since we used an intracellular antigen (α-SMA) as pEndMT markers, we would need to search for cell surface antigens specific to pEndMT. Second, the SuHx rodent model did not develop neointimal or plexiform lesions, as is seen in the confocal images. A more comprehensive analysis of EndMT in clinical PAH and other experimental models of pulmonary hypertension such as PHD2-deficient mice (4) should be explored in future. Third, we used double fluorescent reporter mice crossed with VE-cadherin/Cre to fate-map all endothelial cells. An inducible Cre should be used to fate-map in a model where an intervention is used several weeks later. Finally, our definition of NEMCs includes airway smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts. To date, there have been no reported specific superficial markers that distinguish vascular smooth muscle cells/fibroblasts from airway smooth muscle cells/fibroblasts; we could not isolate vascular smooth muscle cells/fibroblasts with the flowcytometric method. However, Dixit et al. (5) reported that airway smooth muscle cells/fibroblasts and vascular smooth muscle cells/fibroblasts have common progenitor cells. Thus, the comparison of cEndMT cells and NEMCs with the current definition would have some importance.

In conclusion, the present study has established the presence of transitioning EndMT (pEndMT) and transitioned EndMT (cEndMT). Whereas pEndMT cells highly expressed EPC markers, cEndMT cells had Sca-1-rich smooth muscle progenitor cell-like phenotype. Furthermore, cEndMT cells had the paracrine effect of enhancing proliferation and migration for both endothelial cells and mesenchymal cells. Our findings are the first elucidation of cEndMT characteristics and will be useful for further studies to search for a possible therapeutic strategy by MEndT.

GRANTS

This work was supported in part by NIH Grants P01 HL-108800 and R01 HL-095797, a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (JSPS KAKENHI Grant Nos. G16K19445 and 17H04181) from the Japanese Ministry of Education and Science, and another from GSK Japan Research Grant 2016 (Grant No. G-12).

DISCLOSURES

T. Suzuki received a research grant from GlaxoSmithKline and a research fellowship from the Uehara Memorial Foundation. R. Nishimura is a member of a department endowed by Actelion Pharmaceuticals.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

T.S. and R.N. performed experiments; T.S., Y.T. and J.W. analyzed the data; T.S., E.J.C., Y.T. and J.W. interpreted results of experiments; T.S., Y.T. and J.W. prepared figures; T.S., E.J.C., M.T., A.R., X.C., R.N., Y.T., K.T., and J.W. drafted and revised manuscript; T.S. and J.W. conceptualized and designed this study; All authors approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Prof. Atsushi Iwama (Chiba University), Yaeko Nakajima-Takagi (Chiba University), and Yuki Yamamoto (Kyoto University) for generous advice about flow cytometry and stem cells. We also thank Linda Gleaves, Santhi Gladson, Sheila Shay (Vanderbilt University Medical Center), and Ikuko Sakamoto (Chiba University) for technical assistance in the experiments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alva JA, Zovein AC, Monvoisin A, Murphy T, Salazar A, Harvey NL, Carmeliet P, Iruela-Arispe ML. VE-Cadherin-Cre-recombinase transgenic mouse: a tool for lineage analysis and gene deletion in endothelial cells. Dev Dyn 235: 759–767, 2006. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arciniegas E, Frid MG, Douglas IS, Stenmark KR. Perspectives on endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition: potential contribution to vascular remodeling in chronic pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 293: L1–L8, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00378.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ciuclan L, Bonneau O, Hussey M, Duggan N, Holmes AM, Good R, Stringer R, Jones P, Morrell NW, Jarai G, Walker C, Westwick J, Thomas M. A novel murine model of severe pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 184: 1171–1182, 2011. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201103-0412OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dai Z, Li M, Wharton J, Zhu MM, Zhao YY. Prolyl-4 hydroxylase 2 (PHD2) deficiency in endothelial cells and hematopoietic cells induces obliterative vascular remodeling and severe pulmonary arterial hypertension in mice and humans through hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha. Circulation 133: 2447–2458, 2016. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.021494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dixit R, Ai X, Fine A. Derivation of lung mesenchymal lineages from the fetal mesothelium requires hedgehog signaling for mesothelial cell entry. Development 140: 4398–4406, 2013. doi: 10.1242/dev.098079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans JD, Girerd B, Montani D, Wang XJ, Galiè N, Austin ED, Elliott G, Asano K, Grünig E, Yan Y, Jing ZC, Manes A, Palazzini M, Wheeler LA, Nakayama I, Satoh T, Eichstaedt C, Hinderhofer K, Wolf M, Rosenzweig EB, Chung WK, Soubrier F, Simonneau G, Sitbon O, Gräf S, Kaptoge S, Di Angelantonio E, Humbert M, Morrell NW. BMPR2 mutations and survival in pulmonary arterial hypertension: an individual participant data meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med 4: 129–137, 2016. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00544-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghigna MR, Guignabert C, Montani D, Girerd B, Jaïs X, Savale L, Hervé P, Thomas de Montpréville V, Mercier O, Sitbon O, Soubrier F, Fadel E, Simonneau G, Humbert M, Dorfmüller P. BMPR2 mutation status influences bronchial vascular changes in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 48: 1668–1681, 2016. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00464-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Good RB, Gilbane AJ, Trinder SL, Denton CP, Coghlan G, Abraham DJ, Holmes AM. Endothelial to mesenchymal transition contributes to endothelial dysfunction in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Pathol 185: 1850–1858, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guignabert C, Bailly S, Humbert M. Restoring BMPRII functions in pulmonary arterial hypertension: opportunities, challenges and limitations. Expert Opin Ther Targets 21: 181–190, 2017. doi: 10.1080/14728222.2017.1275567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guignabert C, Dorfmuller P. Pathology and pathobiology of pulmonary hypertension. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 34: 551–559, 2013. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1356496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hashimoto N, Phan SH, Imaizumi K, Matsuo M, Nakashima H, Kawabe T, Shimokata K, Hasegawa Y. Endothelial-mesenchymal transition in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 43: 161–172, 2010. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0031OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hopper RK, Moonen JR, Diebold I, Cao A, Rhodes CJ, Tojais NF, Hennigs JK, Gu M, Wang L, Rabinovitch M. In pulmonary arterial hypertension, reduced bmpr2 promotes endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition via HMGA1 and its target slug. Circulation 133: 1783–1794, 2016. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.020617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huertas A, Tu L, Guignabert C. New targets for pulmonary arterial hypertension: going beyond the currently targeted three pathways. Curr Opin Pulm Med 23: 377–385, 2017. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leopold JA, Maron BA. Molecular mechanisms of pulmonary vascular remodeling in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Int J Mol Sci 17: 761, 2016. doi: 10.3390/ijms17050761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin F, Wang N, Zhang TC. The role of endothelial-mesenchymal transition in development and pathological process. IUBMB Life 64: 717–723, 2012. doi: 10.1002/iub.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Long L, Ormiston ML, Yang X, Southwood M, Gräf S, Machado RD, Mueller M, Kinzel B, Yung LM, Wilkinson JM, Moore SD, Drake KM, Aldred MA, Yu PB, Upton PD, Morrell NW. Selective enhancement of endothelial BMPR-II with BMP9 reverses pulmonary arterial hypertension. Nat Med 21: 777–785, 2015. doi: 10.1038/nm.3877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Markwald RR, Fitzharris TP, Smith WN. Sturctural analysis of endocardial cytodifferentiation. Dev Biol 42: 160–180, 1975. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(75)90321-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McQualter JL, Brouard N, Williams B, Baird BN, Sims-Lucas S, Yuen K, Nilsson SK, Simmons PJ, Bertoncello I. Endogenous fibroblastic progenitor cells in the adult mouse lung are highly enriched in the sca-1 positive cell fraction. Stem Cells 27: 623–633, 2009. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muzumdar MD, Tasic B, Miyamichi K, Li L, Luo L. A global double-fluorescent Cre reporter mouse. Genesis 45: 593–605, 2007. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nikitopoulou I, Orfanos SE, Kotanidou A, Maltabe V, Manitsopoulos N, Karras P, Kouklis P, Armaganidis A, Maniatis NA. Vascular endothelial-cadherin downregulation as a feature of endothelial transdifferentiation in monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 311: L352–L363, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishimura R, Nishiwaki T, Kawasaki T, Sekine A, Suda R, Urushibara T, Suzuki T, Takayanagi S, Terada J, Sakao S, Tatsumi K. Hypoxia-induced proliferation of tissue-resident endothelial progenitor cells in the lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 308: L746–L758, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00243.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pugliese SC, Poth JM, Fini MA, Olschewski A, El Kasmi KC, Stenmark KR. The role of inflammation in hypoxic pulmonary hypertension: from cellular mechanisms to clinical phenotypes. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 308: L229–L252, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00238.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qiao L, Nishimura T, Shi L, Sessions D, Thrasher A, Trudell JR, Berry GJ, Pearl RG, Kao PN. Endothelial fate mapping in mice with pulmonary hypertension. Circulation 129: 692–703, 2014. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.003734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ranchoux B, Antigny F, Rucker-Martin C, Hautefort A, Péchoux C, Bogaard HJ, Dorfmüller P, Remy S, Lecerf F, Planté S, Chat S, Fadel E, Houssaini A, Anegon I, Adnot S, Simonneau G, Humbert M, Cohen-Kaminsky S, Perros F. Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition in pulmonary hypertension. Circulation 131: 1006–1018, 2015. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.008750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reynolds AM, Holmes MD, Danilov SM, Reynolds PN. Targeted gene delivery of BMPR2 attenuates pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 39: 329–343, 2012. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00187310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sakao S, Tatsumi K, Voelkel NF. Reversible or irreversible remodeling in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 43: 629–634, 2010. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0389TR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sekine A, Nishiwaki T, Nishimura R, Kawasaki T, Urushibara T, Suda R, Suzuki T, Takayanagi S, Terada J, Sakao S, Tada Y, Iwama A, Tatsumi K. Prominin-1/CD133 expression as potential tissue-resident vascular endothelial progenitor cells in the pulmonary circulation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 310: L1130–L1142, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00375.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sohal SS. Endothelial to mesenchymal transition (EndMT): an active process in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)? Respir Res 17: 20, 2016. doi: 10.1186/s12931-016-0337-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sohal SS. Epithelial and endothelial cell plasticity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Respir Investig 55: 104–113, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.resinv.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stenmark KR, Frid M, Perros F. Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition: an evolving paradigm and a promising therapeutic target in PAH. Circulation 133: 1734–1737, 2016. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.022479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Summer R, Fitzsimmons K, Dwyer D, Murphy J, Fine A. Isolation of an adult mouse lung mesenchymal progenitor cell population. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 37: 152–159, 2007. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0386OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suzuki T, Tada Y, Nishimura R, Kawasaki T, Sekine A, Urushibara T, Kato F, Kinoshita T, Ikari J, West J, Tatsumi K. Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition in lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury drives a progenitor cell-like phenotype. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 310: L1185–L1198, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00074.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tuder RM, Groves B, Badesch DB, Voelkel NF. Exuberant endothelial cell growth and elements of inflammation are present in plexiform lesions of pulmonary hypertension. Am J Pathol 144: 275–285, 1994. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ubil E, Duan J, Pillai IC, Rosa-Garrido M, Wu Y, Bargiacchi F, Lu Y, Stanbouly S, Huang J, Rojas M, Vondriska TM, Stefani E, Deb A. Mesenchymal-endothelial transition contributes to cardiac neovascularization. Nature 514: 585–590, 2014. doi: 10.1038/nature13839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Voelkel NF, Douglas IS, Nicolls M. Angiogenesis in chronic lung disease. Chest 131: 874–879, 2007. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Welch-Reardon KM, Wu N, Hughes CC. A role for partial endothelial-mesenchymal transitions in angiogenesis? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 35: 303–308, 2015. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zeisberg EM, Potenta SE, Sugimoto H, Zeisberg M, Kalluri R. Fibroblasts in kidney fibrosis emerge via endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 2282–2287, 2008. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008050513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zeisberg EM, Tarnavski O, Zeisberg M, Dorfman AL, McMullen JR, Gustafsson E, Chandraker A, Yuan X, Pu WT, Roberts AB, Neilson EG, Sayegh MH, Izumo S, Kalluri R. Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition contributes to cardiac fibrosis. Nat Med 13: 952–961, 2007. doi: 10.1038/nm1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]