Abstract

Although the functionality of the lens water channels aquaporin 1 (AQP1; epithelium) and AQP0 (fiber cells) is well established, less is known about the role of AQP5 in the lens. Since in other tissues AQP5 functions as a regulated water channel with a water permeability (PH2O) some 20 times higher than AQP0, AQP5 could function to modulate PH2O in lens fiber cells. To test this possibility, a fluorescence dye dilution assay was used to calculate the relative PH2O of epithelial cells and fiber membrane vesicles isolated from either the mouse or rat lens, in the absence and presence of HgCl2, an inhibitor of AQP1 and AQP5. Immunolabeling of lens sections and fiber membrane vesicles from mouse and rat lenses revealed differences in the subcellular distributions of AQP5 in the outer cortex between species, with AQP5 being predominantly membranous in the mouse but predominantly cytoplasmic in the rat. In contrast, AQP0 labeling was always membranous in both species. This species-specific heterogeneity in AQP5 membrane localization was mirrored in measurements of PH2O, with only fiber membrane vesicles isolated from the mouse lens, exhibiting a significant Hg2+-sensitive contribution to PH2O. When rat lenses were first organ cultured, immunolabeling revealed an insertion of AQP5 into cortical fiber cells, and a significant increase in Hg2+-sensitive PH2O was detected in membrane vesicles. Our results show that AQP5 forms functional water channels in the rodent lens, and they suggest that dynamic membrane insertion of AQP5 may regulate water fluxes in the lens by modulating PH2O in the outer cortex.

Keywords: aquaporin (AQP), fiber cell membrane vesicles, hydrostatic pressure of the lens, lens, water permeability

INTRODUCTION

The aquaporin (AQP) family of water channels mediate the passive diffusion of water across cell membranes and, as such, play major roles in many physiological and pathological processes (32). Thirteen AQP isoforms have been identified in humans, and ongoing research has shown that differences in water permeability, transcriptional regulation, posttranslational modification, protein stability, and polarized membrane distribution between the different AQP isoforms account for the functional differences in water permeability observed at the cellular level in different tissues (1, 9, 25). In the ocular lens, AQPs are considered essential to the lens internal microcirculation system that generates circulating ionic and fluid fluxes, which, in the absence of a blood supply, delivers nutrients to and removes waste products from the lens center faster than would occur by passive diffusion alone (39, 40).

The microcirculation system and specialized architecture of the lens maintain its transparency and homeostasis. The lens anterior surface is covered with a single layer of epithelial cells while the bulk of the lens is formed of highly elongated fiber cells organized in concentric growth rings (4). The lens continues to grow throughout life by the addition of new fiber cells formed by the terminal differentiation of epithelial cells localized at the lens equator. In this way, the older and organelle-free mature fiber cells are encapsulated into the deeper core of the lens, whereas the youngest and metabolically active differentiating fiber cells are found in the peripheral outer cortex of the lens (38, 41). Superimposed on this gradient of lens development, differentiation, and growth are spatial differences in the expression and posttranslational modification of at least three AQP isoforms. AQP0 (19), AQP1 (50), and, most recently, AQP5 expression in the lens has been confirmed in multiple species (20, 34), and changes in the expression patterns during mouse lens development and growth have been mapped (44, 50).

AQP1 is abundantly expressed in a variety of tissues (2) and in the eye is found in the corneal endothelium, amacrine, and glial cells of the retina and in the lens epithelium (8, 24, 31). During development, AQP1 is first expressed in lens epithelial cells at embryonic day 17 in the mouse lens. AQP1 expression progressively increases during postnatal development, which coincides with an increase in the size of the lens (50). This increased expression of AQP1 translates into an increase in the mercury-sensitive water permeability of isolated lens epithelial cells (10, 50). Deletion of AQP1 in the lens epithelium resulted in an approximately threefold reduction of the water permeability of AQP1 knockout mouse lenses (46). Although lack of AQP1 expression did not affect lens morphology and transparency, it was found that incubation of lenses from AQP1 knockout mice in high-glucose solutions resulted in accelerated loss of lens transparency relative to that seen in wild-type lenses. Therefore, AQP1 is required to maintain the transparency of the lens, especially following exposure to stress conditions such as hyperglycemia and osmotic imbalance.

AQP0, previously known as major intrinsic protein 26 (MIP26), is a highly abundant protein that constitutes over 60% of the total membrane protein content of the lens (7). AQP0 was thought to be exclusively expressed in lens fiber cells, although recent reports show weak immunoreactivity in bipolar, amacrine, and ganglion cells of the retina (11, 23). AQP0 is a low-conductance water channel, with water permeability some 30- and 20-fold lower than AQP1 and AQP5, respectively (10, 42, 57). AQP0 can double its permeability in mildly acidic environments (48). Unlike AQP1 and AQP5, AQP0 is not sensitive to inhibition by mercury (42), owing to the absence of a cysteine residue contained within the water pore which, in other AQP isoforms, renders the water channel sensitive to mercurial inhibition (33, 47). As the lens grows and ages, AQP0 undergoes differentiation-dependent posttranslational modifications to its COOH-terminal domain, including phosphorylation, truncation, glycation, and deamidation (3). While the effect of glycation and deamidation on AQP0 water permeability is unclear, the most abundant modifications, phosphorylation and truncation, are thought to alter the regulation of its water permeability. Several sites of phosphorylation have been identified (36a), while extensive COOH-terminal truncation has been well characterized in the core of the lens (19, 54). Phosphorylation of AQP0 at serine 235, the most abundant phosphorylation site, occurs via PKA and is mediated by A-kinase anchoring protein 2 (AKAP2; 16). The phosphorylation of the COOH-terminal tail has been shown to disrupt calmodulin binding (36a) and therefore changes the regulation of AQP0 activity in the presence of elevated Ca2+. Structurally, AQP0 has been shown to exist in two conformations, suggesting a change of AQP0 function from a water pore in the periphery to an adhesion protein in the core of the lens through its identification within 11–13 nm “thin lens junctions” (17, 18, 21).

AQP5 is a water channel recently identified in epithelial and fiber cells of the ocular lens at the gene (43, 55) and protein (5, 54) levels. Most recently, its expression was verified not only in our laboratory (20) but also by other researchers (34). Interestingly, immunohistochemical mapping of AQP5 distribution across the lens radius (20) revealed a differentiation-dependent change in the subcellular localization of AQP5 from a cytoplasmic to membranous labeling pattern with fiber cell differentiation, and therefore radial position within the lens. Furthermore, the labeling pattern observed for AQP5 in the outer cortex of the lens was very different from that observed for AQP0, which is always membranous in the young, differentiating fiber cells present in this region (19). These differences in membrane localization of AQP5 relative to AQP0 raises questions about the relative functional roles of the two AQPs in the different regions of the lens, especially since AQP5 has a ~20-fold higher water permeability than AQP0 (57), although AQP0 is 100 times more abundant than AQP5 (5).

To determine whether AQP5 contributes to the water permeability of peripheral lens fiber cells, we have in this study employed a fluorescence dye dilution assay that utilizes fiber cell membrane vesicles isolated from the outer cortex of either the mouse or rat lens. In parallel we show species-specific differences in AQP5 membrane labeling levels, and hence differences in the potential contribution of AQP5 to overall water permeability. To distinguish the relative contributions of AQP5 and AQP0 to overall water permeability, vesicles from both species were incubated in the absence or presence of mercury (HgCl2), which blocks AQP5, but not AQP0 water channels. Our results suggest not only that AQP5 contributes to the water permeability of cortical fiber cells, but also that the water permeability in this region can be dynamically upregulated by the insertion of AQP5 from a cytoplasmic pool into the membranes of differentiating fiber cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

An affinity-purified anti-AQP5 antibody directed against the final 17 amino acids (rat sequence) of the COOH terminus of the protein, was obtained from Millipore (Billerica, MA, catalog no. AB15858). Affinity-purified anti-AQP0, directed against the final 17 amino acids (human sequence) of the COOH terminus of the protein, was obtained from Alpha Diagnostic International (San Antonio, TX, catalog no. AQP01-A). Secondary antibodies (goat anti-rabbit-Alexa 488), fluorophore-conjugated wheat germ agglutinin (WGA-Alexa Fluor 594) for labeling of cell membranes, and calcein acetoxymethyl ester (calcein-AM) used for fluorescent loading of epithelial cells and fiber cell membrane vesicles were each obtained from Thermofisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). DAPI, obtained from Sigma Aldrich (St Louis, MO), was used for fluorescent labeling of cell nuclei. Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) was prepared fresh from PBS tablets. Unless otherwise stated all other chemicals were from Sigma Aldrich.

Collection and preparation of lenses.

Adult mouse and rat lenses were removed from C57BL/6 mice or Wistar rats immediately following death, using procedures in accordance with the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research, which were approved by the University of Auckland Animal Ethics Committee (protocol no. 001303). Following extraction, lenses were either immediately placed in fixative and subsequently processed for immunohistochemistry, placed in warm PBS before preparation of isolated epithelial cells or fiber cell vesicles, or prepared for organ culturing from 2 to 17 h in Artificial Aqueous Humor (AAH: containing 125 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 4.5 mM KCl, 10 mM NaHCO3, 2 mM CaCl2, 5 mM glucose, 10 mM sucrose, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 300 mosM/l). At the end of the incubation period, organ cultured lenses were either immediately fixed in 0.75% paraformaldehyde and processed for immunohistochemistry, or used to isolate fiber cell vesicles.

Isolation of lens epithelial cells and fiber cell membrane vesicles.

Immediately following extraction from the eye, or after organ culture in AAH, a pair of sharpened forceps was used to separate and remove the lens capsule and adherent epithelial cells from the underlying fiber cell mass. Forceps were then used to peel off small clumps of differentiating fiber cells from the outer cortical fiber cell mass. The lens capsule was incubated in collagenase dissociation buffer (150 mM Na-gluconate, 4.7 mM KCl, 5 mM glucose, 5 mM HEPES, 0.125% Type IV collagenase, pH 7.4) for 30 min at 37°C to isolate lens epithelial cells. After the first 15 min of incubation, 4 µM calcein-AM was added to the dissociation buffer to label dissociated epithelial cells with fluorescent calcein during the remaining 15 min of the dissociation incubation period. Epithelial cells were pelleted at 150 g for 3–5 min using a bench-top microcentrifuge and washed twice with 300 mosM/l isotonic saline (139 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM glucose, 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 300 mosM/l). To form fiber cell membrane vesicles, clumps of differentiating fiber cells were isolated from the outer cortex of the lens with forceps and transferred to isotonic saline which contained 5 mM CaCl2. Clumps of fiber cells were incubated for 30 min at room temperature (20°C), which induced spontaneous formation of vesicles (51). To load these fiber cell-derived membrane vesicles with fluorophore, 6 µM calcein-AM was added to the Ca2+-containing isotonic saline for the duration of the 30-min incubation time. Membrane vesicles were then pelleted at 150 g for 3–5 min and washed twice in Ca2+-free isotonic saline for immediate use in the fluorescence dye dilution assay.

Immunolabeling of lens sections and fiber cell membrane vesicles.

Lenses, either immediately after extraction from the eye, or after organ culture, were fixed in 0.75% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 24 h, and prepared for cryosectioning using previously published protocols (28). For sectioning, whole lenses were mounted encased in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound (Tissue-Tek; Sakura Finetek, Zoeterwoude, The Netherlands), and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen for 15–20 s. Lenses were cryosectioned at −19°C using a cryostat (CM3050, Leica Microsystems, Germany), and 14 µm-thick equatorial cryosections were transferred onto plain microscope slides. Isolated fiber membrane vesicles were plated for immunolabeling experiments on plain microscope glass slides, before being fixed for 30 min in 2% paraformaldehyde. Both lens sections and fiber-derived membrane vesicles were subjected to the same established immunohistochemistry protocols (19). Briefly, fixed lens sections or fiber membrane vesicles were first incubated in blocking solution (3% bovine serum albumin, 3% normal goat serum in PBS pH 7.4) for 1 h at room temperature. After washing in PBS pH 7.4, samples were incubated in primary antibody in blocking solution (1:100) overnight at 4°C. Samples were washed in PBS pH 7.4 and incubated for 1.5 h, at room temperature in the dark with fluorescent secondary antibodies in blocking solution (1:200), or contained 0.125 µg/ml DAPI to stain cell nuclei of lens sections. Where necessary, sections were then incubated with WGA-Alexa Fluor 594 in PBS pH 7.4 (1:100) for 1 h (room temperature) to label cell membranes. Lens sections and membrane vesicles were coverslipped using VectaShield HardSet anti-fade mounting medium (Vector, Burlingame, CA). Immunofluorescent images were acquired using a laser scanning confocal microscope (Olympus FV1000, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with FluoView 2.0b software. For presentation, labeling patterns were pseudo-colored and combined using Adobe Photoshop CS6 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA).

Fluorescence dye dilution assay for water permeability.

Calcein-AM-loaded epithelial cells or fiber cell membrane vesicles were attached to the bottom of a custom-made recording chamber using Cell-Tak adhesive agent (Corning, Bedford, MA) for 30 min at room temperature. To remove loosely attached cells or vesicles, 300 mosM/l isotonic saline was washed through the recording chamber for 5 min using a gravity-fed perfusion system which allowed the composition of the bath to be completely changed with a time constant of 2 s. The chamber was mounted on a Nikon Eclipse TE 300 inverted epifluorescence microscope, equipped with a ×40 CFI Plan Fluor numerical aperture 0.75 objective and a filter set (Nikon, B-2A) that matched the excitation and emission spectra of calcein-AM. Differential interference contrast (DIC) and epifluorescence images were collected using an electron-multiplying CCD camera (Cascade II 512B emCCD, Photometrics, Tucson, AZ), suitable for imaging in low-light applications with rapid frame rates. Imaging protocols consisted of collecting an initial DIC image of epithelial cells or fiber cell membrane vesicles to allow accurate measurement of their initial cross-sectional area in isotonic saline. Subsequently, a series of fluorescence images were collected at 2 Hz to record the time course of change in fluorescence intensity in response to a 390 mosM/l hypertonic challenge, induced by switching incoming bathing solution from isotonic to hypertonic saline, which contained 185 mM NaCl (Fig. 1A). Images were acquired using Imaging Workbench 5.2 (Indec BioSystems, Los Altos, CA). Regions of interest were created within the boundaries of individual epithelial cells or fiber-derived vesicle, thereby enabling changes in fluorescence intensity in response to alterations in the volume of an epithelial cell or vesicle to be captured in real time (Fig. 1B). Hypertonic challenge was performed either in the absence or presence of 300 μM HgCl2, an irreversible inhibitor of AQP5 and AQP1 channels (33, 47), but not AQP0 water channels (42). The effect of mercury was examined by a 5-min preincubation of lens epithelial cells or fiber cell membrane vesicles in isotonic saline containing 300 μM HgCl2, before application of an identical hypertonic challenge in the presence of 300 μM HgCl2.

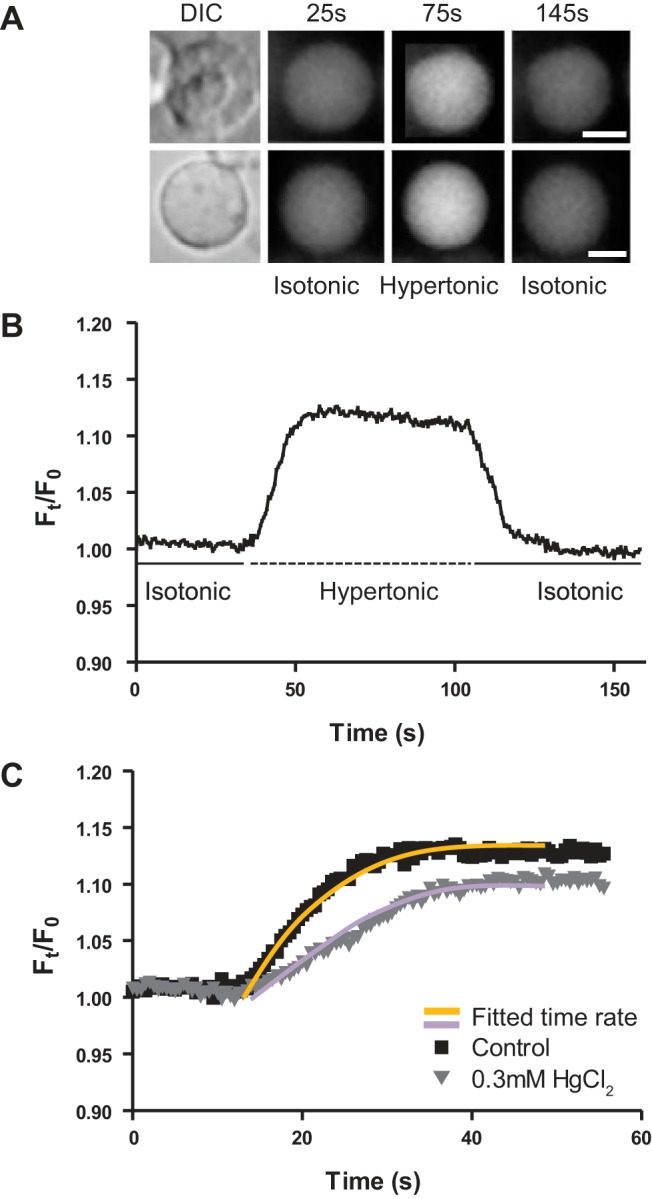

Fig. 1.

Fluorescent assay used to calculate the rate of change in cell/vesicle volume. A: representative images of a single rat epithelial cell (top) and fiber cell membrane vesicle (bottom) loaded with calcein, before and after exposure to hypertonic (390 mosM/l) saline. A single differential interference contrast (DIC) image was taken before the exposure to hypertonic saline and subsequently used to calculate the initial area of the epithelial cell or membrane vesicle and also to differentiate between epithelial cells and vesicles by the presence or absence of a cell nucleus. Representative images from the initial exposure to isotonic (25 s), hypertonic (75 s), and back to isotonic (145 s) saline are shown. B: representative bleach-corrected time course, showing the normalized change in calcein fluorescence intensity in response to a hypertonic challenge. Fluorescence intensity was collected from a central region of interest within individual vesicles. C: the initial change in fluorescence intensity of two vesicles in response to hypertonic challenge, in either the absence or the presence of mercury, fitted with monoexponential equations to extract the rate of change in cell volume (τ), used to calculate the water permeability (PH2O, Eq. 2). Scale bar, 5 µm.

Calculation of water permeability.

The water permeability of epithelial cells and fiber cell-derived membrane vesicles has been determined by modifying the equation adopted from a paper published by Varadaraj et al. (51) in 1999:

| (1) |

Equation 1 is based on the assumption that water flows across a cell membrane in response to the gradient of osmolarity, established across the membrane, at a rate determined by the surface area, Sm, and rate of change of volume, . Since in our method we used a fluorescent tracer to follow the change in volume, instead of monitoring the change in cross sectional area, we modified the Eq. 1 to fit our assay system which measures the time course of the rate in change of fluorescence intensity in response to hypertonic challenge. This response is given by Eq. 2.

| (2) |

To calculate the water permeability, the membrane surface area (Sm) was measured using DIC images that captured the initial morphology of the epithelial cell or fiber cell membrane vesicles showing near perfect spherical shape for these objects (Fig. 1A), and then calculated using Eq. 3.

| (3) |

where the radius (r, in μm) was obtained using the cross-sectional area (A) calculated by tracing the pixels within the defined region of interest using ImageJ software (Eq. 4).

| (4) |

Imaging Workbench 5.2 software was used off-line to quantify the change in fluorescence intensity in response to hypertonic challenge within individual calcein-AM loaded epithelial cells or fiber membrane vesicles. Correction for photo-bleaching was applied by normalizing data against a monoexponential function fitted to the initial, prechallenge, region of the time course using Clampfit 9.2 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) to produce a bleach-corrected time course showing the change in fluorescence intensity caused in response to hyperosmotic challenge (Fig. 1B). A monoexponential of the form was fitted to the fluorescence response to challenge (Fig. 1C), and the time constant (τ) was extracted to quantify the rate of change of fluorescence using the best-fit values for the initial and final fluorescence F1 and F2 (Eq. 5):

| (5) |

The rate of change in fluorescence intensity (Eq. 5) along with the external osmotic gradient and initial resting area were fitted into Eq. 2 to calculate the relative water permeability of epithelial cells, and fiber cell membrane vesicles are expressed in arbitrary units (AU), where CH2O ≈ 55 M is the concentration of water and Ci(0) = 300 mosM/l is the initial bathing solution, assumed to be equal to the initial intracellular osmolarity, and C0 = 390 mosM/l. We applied this approach for calculation of the water permeability of epithelial cells and membrane vesicles since it has been shown that using monoexponential fits of normalized fluorescence data is more accurate and mathematically stable for calculation of a decay rate (30, 56), whereas usage of multiexponential and parameterized interpretation of fluorescent decays is inaccurate (35, 36, 56). Following this rationale, we have chosen to normalize our data set of change of fluorescence time course and use arbitrary units (AU) for our rate calculations.

Statistical analysis.

To evaluate the water permeability of lens epithelial cells or fiber cell membrane vesicles, data were obtained from at least three animals performed through at least three separate experiments. Mean data of experiments are given ± standard error of the mean (SE). Statistical significance was tested with the Mann-Whitney U-test, using GraphPad Prism (La Jolla, CA). Statistical significance was set at the α = 0.05 level.

RESULTS

Species differences in the membrane localization of AQP5 in rodent lenses and fiber cell-derived membrane vesicles.

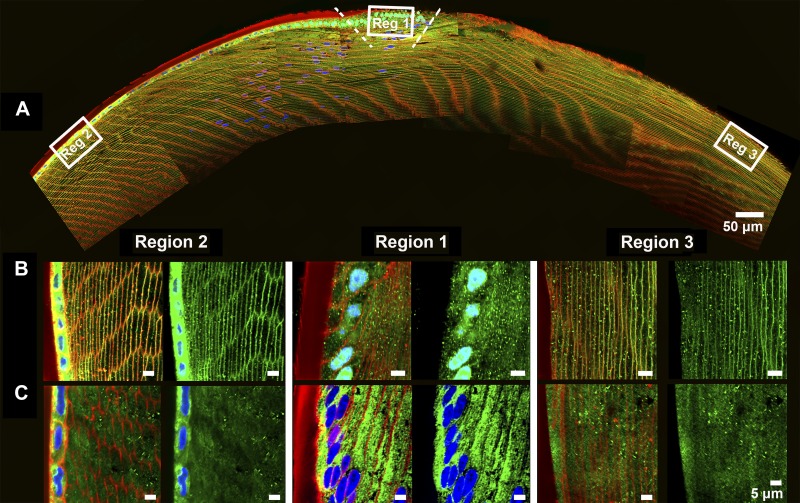

In previous studies, we have used immunohistochemistry to map the distribution of AQP0 in the rat lens (19) and AQP0 and AQP5 in the mouse lens (20, 44). In these previous studies we noted subtle species differences in the distribution of AQP5 in the outer cortex. In the present study, we applied our immunohistochemistry mapping approach to axial sections to examine more closely how these differences in distribution of AQP5 in the adult mouse and rat lens manifest as fiber cells proceed through the different stages of differentiation and elongation to reach the anterior and posterior poles of the lens (Fig. 2). We confirmed our previous observation that, in differentiating fiber cells, AQP5 is predominately cytoplasmic in peripheral fiber cells but undergoes a distinctive translocation to the membranes of elongating fiber cells at distinct stages of fiber cell differentiation. In the current study, we also show that the radial location of this transition is species dependent. In the mouse lens, the pool of cytoplasmic AQP5 labeling was confined to a narrow, superficial zone located to the lens modiolus at the equator (Fig. 2, region 1B). Either side of the modiolus region, AQP5 is inserted into the membranes of elongating fiber cells (Fig. 2A), with AQP5 labeling becoming strongly associated with the membranes of fiber cells that reach both the anterior (Fig. 2, region 2B) and posterior poles of the lens (Fig. 2, region 3B). In contrast, in the rat lens, AQP5 exhibited predominately cytoplasmic labeling throughout the entire equatorial region (Fig. 2, region 1C), remaining cytoplasmic in differentiating fiber cells as they elongated to reach both the anterior (Fig. 2, region 2C) and posterior (Fig. 2, region 3C) poles of the lens.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the subcellular localization of aquaporin isoform 5 (AQP5) in axial sections taken from mouse and rat lenses. A: a low-power overview of an axial mouse lens section, labeled with the general membrane marker wheat germ agglutinin (WGA; red) and the nuclear stain DAPI (blue) to define three regions where the subcellular location of AQP5 (green) is subsequently compared between mouse (B) and rat (C). B: higher-magnification images from the mouse lens reveal cytoplasmic labeling of AQP5 which is restricted to a narrow and superficial region localized around the equator, designated by the dotted line (region 1B). Beyond this region, AQP5 was found to be associated with the membrane at both the anterior (region 2B) and posterior (region 3B) poles of the lens. C: higher-magnification images from the rat lens showed that AQP5 labeling remained cytoplasmic in the equator (region 1C), in the anterior (region 2C) and posterior (region 3C) poles of the lens. For clarity of display a mirror image, in which WGA labeling is omitted, is presented on the right-hand side next to each double- or triple-labeled image.

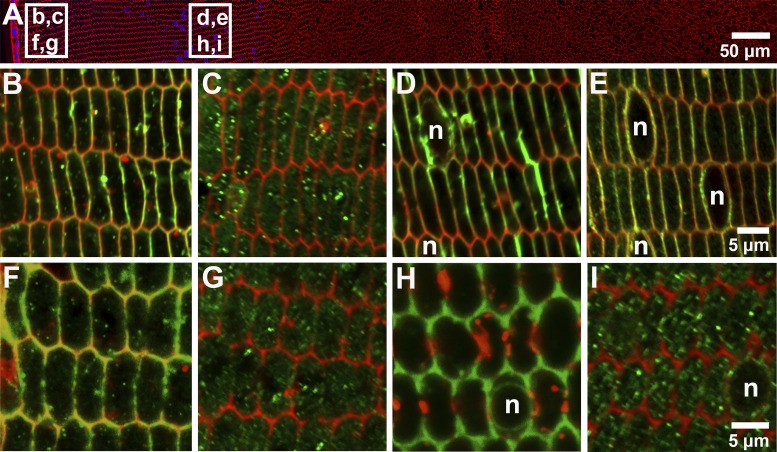

These observed differences of expression of AQP5 in the axial direction in rodent lenses reinforced earlier descriptions along the continuum of differentiation in the equatorial orientation (Fig. 3) (20). Mouse AQP5 labeling was cytoplasmic in peripheral fiber cells as they differentiated from epithelial into fiber cells at the equator of the lens (Fig. 3C). At deeper locations, associated with later stages of fiber cell differentiation, AQP5 labeling abruptly became associated with the plasma membrane, with this membranous labeling then being retained in the rest of the outer cortex of the mouse lens (Fig. 3E). In contrast, in the rat lens, AQP5 labeling remained predominately cytoplasmic in differentiating fiber cells throughout the outer cortex (Fig. 3, G and I). AQP0, on the other hand, at these locations, was always membranous in both the mouse (Fig. 3, B and D) and the rat lenses (Fig. 3, F and H). Based on these observed regional differences in the membrane distribution of AQP5 and AQP0 in the mouse and rat lenses we might expect that the relative contributions of the two water channels to the water permeability of peripheral fiber cells of the outer cortex would be different between the two species.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the membrane localization of AQP0 and AQP5 in the outer cortex of the mouse and rat lenses. A: an equatorial section of rat lens labeled with the membrane marker WGA (red) and the nuclear stain DAPI (blue) showing the regions (white boxes) from which high-magnification images of the subcellular location of AQP0 and AQP5 were obtained from the mouse (B–E) and rat (F–I) lens. To account for the differences of the sizes of the mouse and rat lenses, labeling for AQP0 and AQP5 was obtained from equivalent regions represented with an r/a ratio, where at r/a = 1 indicates a region adjacent to the capsule and r/a = 0 corresponds to the lens core. For both the mouse and rat lenses, r/a = 0.98 for the region next to the capsule (B, C, F, and G). In the deeper outer cortical region, r/a = 0.90 for the mouse lens (D and E), and r/a = 0.77 for the rat lens (H and I). In the mouse (B) and rat (F) lens, AQP0 (green) is expressed around the entire membrane of differentiating fiber cells localized adjacent to the capsule, while AQP5 (green), in the same region, in both the mouse (C) and rat (G) lenses, was localized only in the cytoplasm. In deeper regions of the outer cortex in both the mouse (D) and the rat (H) lenses, AQP0 continued to be membranous. In the same region, changes in the expression of AQP5 were observed since in the mouse lens (E), AQP5 labeling (green) was translocated exclusively to the membranes of differentiating fiber cells, while in the rat lenses (I), AQP5 labeling continued to be strongly cytoplasmic. n, Nuclei; blue, DAPI.

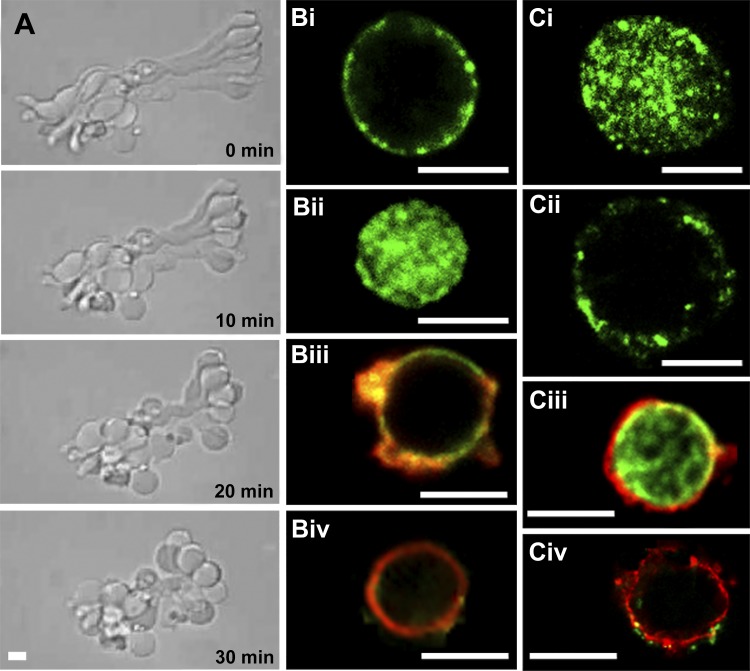

To test this hypothesis, the water permeability of mouse and rat fiber cells needed to be directly compared. However, because of the terminally differentiated state of lens fiber cells and their thin and extremely elongated morphology, measuring water permeability in fiber cells is difficult. Previous studies (6, 51, 52) have presented measurements of the water permeability of lens fiber cells using fiber cell-derived membrane vesicles, which are spontaneously formed when fiber cells are isolated from the lens in presence of Ca2+ ions. To illustrate this process, a series of DIC images is presented from an isolated cluster of rat lens fiber cells that undergoes cell swelling and subsequent formation of individual vesicles after 30 min of incubation in Ca2+-containing isotonic saline (Fig. 4A). To test whether the distribution of AQP5 and AQP0 observed in fixed lens sections remains preserved in fiber cell-derived vesicles, mouse and rat fiber vesicles were labeled with specific COOH-terminal anti-AQP5 and -AQP0 antibodies. Quantification of labeling distribution between cytoplasmic and membrane-bound AQP0/5 was compromised by collapse of the vesicles following paraformaldehyde fixation; however, the labeling distribution qualitatively observed in fiber cell membrane vesicles corresponded with results obtained from rat and mouse lens cryosections. Mouse vesicles showed a predominant membrane localization of AQP5 (Fig. 4Bi) although occasionally vesicles with cytoplasmic localization were also identified (Fig. 4Bii), while AQP0 labeling was always associated with the membrane (Fig. 4, Biii and Biv). In contrast, the majority of membrane vesicles derived from the rat lens displayed predominant cytoplasmic labeling (Fig. 4Ci), with a small number of vesicles displaying some membrane labeling (Fig. 4Cii). However, like the mouse, AQP0 labeling in fiber cell membrane vesicles derived from the rat lens was found associated with the membrane (Fig. 4, Ciii and Civ). Based on observed differences in the relative abundances, subcellular distributions, and relative permeability’s of AQP0 and AQP5 water channels, we would predict functional heterogeneity in water permeability in fiber-derived membrane vesicles, and furthermore that species differences may be apparent in the relative contribution of AQP5 conductance to overall water permeability.

Fig. 4.

The subcellular distribution of AQP0 and AQP5 in membrane vesicles formed from fiber cells isolated from the mouse or rat lens. A: a clump of fiber cells isolated from the rat lens undergoes a process of vesiculation to spontaneously form a cluster of membrane vesicles after 30 min of incubation in the presence of Ca2+. B: in membrane vesicles isolated from the mouse lens, AQP5 (green) was predominantly associated with the membranes (Bi), but could occasionally be also found in the cytoplasm (Bii). In double-labeled vesicles, AQP0 (red) was always membranous and could be found coexpressed with either higher (Biii) or lower levels of AQP5 labeling (Biv). C: in the rat, AQP5 was predominately cytoplasmic (Ci), although some vesicles exhibited membrane labeling for AQP5 (Cii). In double-labeled rat vesicles, AQP0 was always membranous, while AQP5 labeling was usually cytoplasmic (Ciii), although vesicles that coexpressed both AQP0 and AQP5 in the membrane were occasionally detected (Civ). Scale bar in A, B, and C is 5 µm.

Measuring the water permeability of mouse and rat fiber cell membrane vesicles.

Two approaches were used to distinguish between the relative contribution of AQP5 and AQP0 to water permeability of lens differentiating fiber cells. First, we utilized the differential sensitivity of AQP5 and AQP0 to Hg2+ (33) as a pharmacological tool to delineate the relative contributes of the two water channels to overall water permeability. Second, we exploited the observed species-dependent distribution of AQP5 in the outer cortex of the mouse and rat lenses to make measurements where the Hg2+-sensitive AQP5 contribution would be expected to be lower (cytoplasmic AQP5) or higher (membranous AQP5) for fiber vesicles derived from the rat or mouse, respectively.

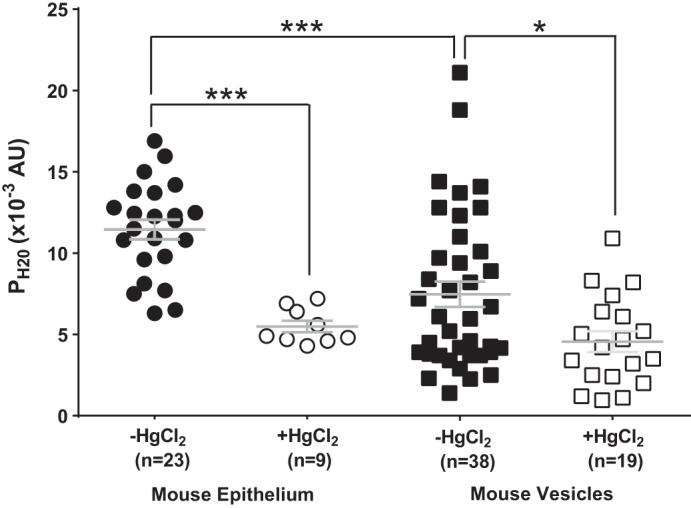

To validate the use of mercury as a pharmacological blocker of AQP5, it was first applied to mouse lens epithelial cells, which express the mercury-sensitive aquaporins AQP1 and AQP5. The average PH2O of mouse epithelial cells (11.45 ± 0.6 × 10−3 AU, n = 23) was halved (5.4 ± 0.3 × 10−3 AU, n = 9) after inhibition of AQP1/5 with 300 µM HgCl2 (Fig. 5). Relative to epithelial cells, fiber cell membrane vesicles from the mouse had an average PH2O (7.5 ± 0.8 × 10−3 AU, n = 38), some 32% less than the PH2O of epithelial cells. It was found that PH2O of mouse fiber cell vesicles displayed significant variability. While one third of mouse fiber-derived membrane vesicles gave PH2O values that were similar in magnitude to those measured in mouse lens epithelia, a second population showed a lower water permeability that was some 73% lower than the PH2O of epithelial cells, a result that was similar to what had previously been reported in the literature (50, 51). Preincubated mouse fiber-derived membrane vesicles exposed to Hg2+ significantly reduced the observed average PH2O (4.6 ± 0.6 × 10−3 AU, n = 19, P < 0.02) and eliminated the subgroup of vesicles with higher PH2O values seen in the absence of mercury (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Water permeability of epithelial cells and fiber cell membrane vesicles in the mouse lens. Scatterplots showing the water permeability (PH2O) of mouse epithelial cells and fiber cell membrane vesicles in the presence and absence of 300 µM HgCl2. The addition of HgCl2 significantly reduced the PH2O of mouse epithelial cells and fiber cell membrane vesicles. Bars show means ± SE; AU, arbitrary units. ***P < 0.0001, *P < 0.02; n, no. of cells or membrane vesicles.

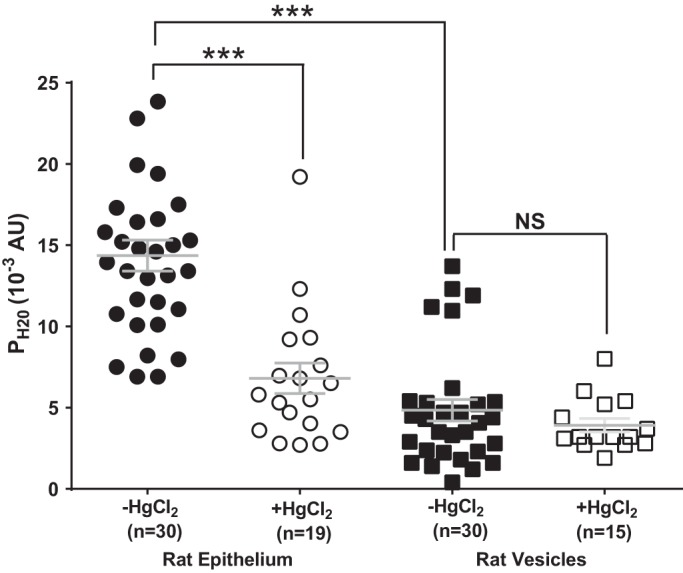

The same functional dissection of mercury-sensitive water permeability was performed on rat lenses (Fig. 6). As seen in the mouse, rat epithelial cells had a high PH2O (14.4 ± 0.9 × 10−3 AU, n = 30) that was inhibited (6.8 ± 0.9 × 10−3 AU, n = 19) in the presence of mercury (Fig. 6). The average PH2O of rat fiber-derived membrane vesicles (4.8 ± 0.6 × 10−3 AU, n = 30), was approximately threefold lower than the water permeability measured in rat lens epithelial cells. However, unlike the mouse, rat fiber-derived membrane vesicles consisted of one large group of vesicles exhibiting this low PH2O, with only 5 vesicles out of 30 that exhibited higher PH2O values that mirrored those seen in rat epithelial cells. Incubation with Hg2+ of rat fiber-derived membrane vesicles showed a small, but not significant, reduction in PH2O (3.9 ± 0.4 × 10−3 AU, n = 15) and the absence of the subgroup of vesicles which exhibited higher PH2O values. In summary, the comparative mercury sensitivities of mouse and rat fiber-derived membrane vesicles seem to be consistent with their immunohistochemical localizations within both fixed lens sections (Figs. 2 and 3) and membrane vesicles (Fig. 4). Taken together, it appears that AQP5 is present in the membrane and contributes, along with AQP0, to the overall water permeability of fiber cells in the outer cortex of the mouse lens. In the rat lens, where AQP5 exists predominately as a pool of cytoplasmic water channels, AQP5 does not appear to make a significant contribution to overall water permeability of cortical fiber cells, as evidenced by the Hg2+-insensitivity of the PH2O measured in rat fiber cell membrane vesicles. This suggests that, in the outer cortex of the rat lens, AQP0 mediates water permeability.

Fig. 6.

Water permeability of epithelial cells and fiber cell membrane vesicles in the mouse lens. Scatterplots showing the water permeability (PH2O) of rat epithelial cells and fiber cell membrane vesicles in the presence and absence of 300 µM HgCl2. The addition of HgCl2 significantly reduced the PH2O of rat epithelial cells but not rat fiber-derived membrane vesicles. Bars show means ± SE; n, no. of cells or membrane vesicles. ***P < 0.0001; NS, not significantly different.

Membrane insertion of AQP5 increases the mercury-sensitive water permeability of rat fiber-derived membrane vesicles.

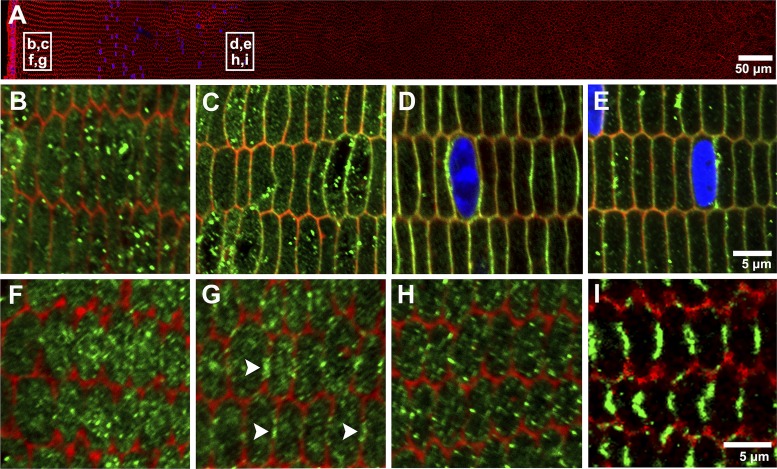

In other tissues, AQP5 has been shown to be a regulated water channel which, in response to osmotic challenge, increases water permeability through translocation to the plasma membrane (26, 27, 58). We therefore investigated whether the process of organ culturing lenses under conditions of osmotic challenge could also induce an insertion of AQP5 into the membranes of fiber cells in the outer cortex of the lens (Fig. 7), and whether such an insertion would subsequently increase the mercury-sensitive water permeability of fiber cell membrane vesicles isolated from organ cultured lenses (Fig. 8). Interestingly, we found that simply organ-culturing lenses in isotonic AAH was sufficient to induce an increase in the membrane localization of AQP5 in both the mouse (Fig. 7, B–E) and the rat (Fig. 7, F–I) lenses, relative to what was observed when lenses were fixed immediately following removal from the eye. Incubating mouse lenses for 2 h in isotonic AAH induced translocation of AQP5 to the membranes of superficial fiber cells in the localized bow region of the outer cortex (Fig. 7C) in comparison to immediately fixed lenses where AQP5 was only cytoplasmic (Fig. 7B). There was no additional change in the localization of AQP5 in the deeper regions of the outer cortex where AQP5 remained membranous in lenses that were fixed immediately upon removal from the eye (Fig. 7D) and organ cultured mouse lenses (Fig. 7E). As previously described, the subcellular distribution of AQP5 labeling in immediately fixed rat lenses was predominantly cytoplasmic throughout the outer cortex (Fig. 7, F and H). However, an overnight incubation of rat lenses in isotonic AAH resulted in a switch in AQP5 localization into the membrane in peripheral differentiating fiber cells (Fig. 7G), with this membrane localization becoming even more prominent in fiber cells located in the deeper regions of the outer cortical region (Fig. 7I). While we do not yet understand the signaling mechanisms responsible for this apparent insertion of AQP5 from a cytoplasmic pool into the membrane, we can use the observed phenomenon to investigate whether this increased membrane insertion of AQP5 alters the mercury-sensitive fraction of the water permeability measured in fiber-derived membrane vesicles. Unfortunately, it is technically challenging to derive fiber cell vesicles from the small (~1–5% of total outer cortex area) superficial outer cortical region of the mouse lens that exhibits membrane insertion of AQP5 in response to organ culture. Hence, measurements of water permeability post-organ culture were only performed on rat fiber-derived vesicles where the biggest increase in Hg2+-sensitive PH2O would be expected to be observed following organ culture.

Fig. 7.

Dynamic insertion of AQP5 in the cell membranes of organ-cultured rat and mouse lenses incubated in isotonic artificial aqueous humor (AAH). A: low-power overview of an equatorial section of a lens labeled with the membrane marker WGA (red) showing two regions (white boxes) in the outer cortex where high-magnification images were obtained from a mouse (B–E) or rat (F–I) lens, fixed either immediately after removal from the eye (B, D, F, H) or after organ culture in AAH (C, E, G, I). In immediately fixed mouse lenses, AQP5 labeling was predominately cytoplasmic in the superficial (B) region, but was membraneous in the deeper regions (D) of the outer cortex. In sections taken from mouse lenses organ cultured for 2 h, AQP5 labeling translocated to the membranes of differentiating fiber cells in the lens periphery (C), and retained its membraneous location in deeper (E) regions of the outer cortex. In immediately fixed rat lenses, AQP5 labeling was predominately cytoplasmic in both the superficial (F) and deeper regions (H) of the outer cortex. In contrast, in sections from rat lenses organ cultured for 17 h, AQP5 labeling was found in discrete punctae (arrowheads), which colocalized with the membranes of differentiating fiber cells in both peripheral (G) and deeper (I) regions of the outer cortex.

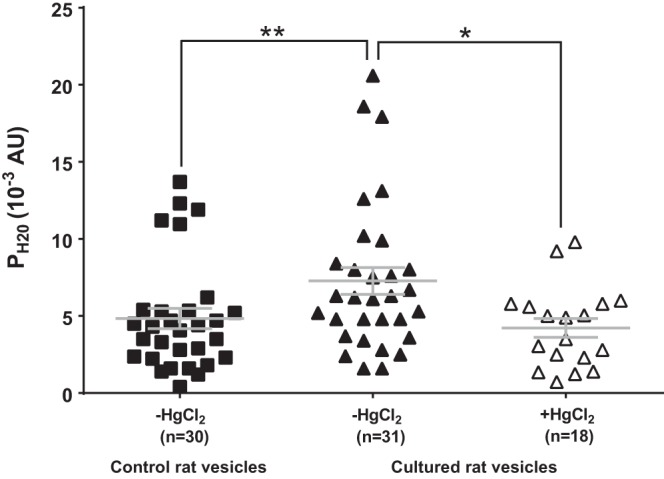

Fig. 8.

Effect of organ culture on the Hg2+-sensitive water permeability of rat fiber cell membrane vesicles. Scatterplots comparing the water permeability (PH2O) of fiber cell membrane vesicles prepared from lenses fixed either immediately after removal from the eye, or after organ culture in AAH for 17 h. The addition of 300 µM HgCl2 significantly reduced the PH2O of membrane vesicles prepared from organ cultured rat lenses. Bars show means ± SE; n, no. of cells or membrane vesicles. **P < 0.01; *P < 0.015.

Fiber-derived membrane vesicles were therefore prepared from the outer cortex of organ-cultured rat lenses, and their water permeability was tested using the fluorescence-based functional assay for water permeability (Fig. 8). We found that in comparison to native rat vesicles (PH2O = 4.8 ± 0.6 × 10−3 AU, n = 30), vesicles derived from organ-cultured rat lenses had a significantly higher average PH2O (7.2 ± 0.6 × 10−3 AU, n = 31, P < 0.01). The observed increase in average PH2O appeared to be due to AQP5 insertion, since the addition of Hg2+ to vesicles prepared from organ-cultured lenses produced a significant reduction in PH2O (4.2 ± 0.6 × 10−3 AU, n = 18, P < 0.015) to values that were found to be not significantly different from the average PH2O measured in acutely isolated lenses, where AQP5 was predominantly located in the cytoplasm of peripheral fiber cells. These results suggest that in the rat lens, AQP5 can be dynamically recruited to the membranes of differentiating fiber cells to increase water permeability in the outer cortex of the lens.

DISCUSSION

In this study we have extended our previous observations (20) of species differences in the subcellular location of AQP5 in mouse and rat lenses, and in addition have shown that AQP5 contributes to the water permeability of fiber cell membranes. Furthermore, we have shown that this contribution of AQP5 to overall water permeability can be increased by the trafficking of AQP5 from a cytoplasmic pool to the fiber cell membrane. In both rat and mouse lenses, AQP5 could be found in distinct cytoplasmic or membranous pools in the outer cortex, but the extent of cytoplasmic AQP5 labeling was more extensive in the rat than the mouse lens (Figs. 2 and 3). In contrast, AQP0 was always found to be associated with the membranes of cortical fiber cells in both species (Figs. 3 and 4). These species-specific differences in the subcellular distribution of AQP5 appeared to be maintained in the fiber cell membrane vesicles isolated from the outer cortex of the mouse and rat lens (Fig. 4). From this observation, we expected that the functional measurements of PH2O in the vesicles isolated from the mouse and rat lens would exhibit heterogeneity in PH2O values that reflect the differences in the subcellular location of AQP5, the higher protein abundance of AQP0 relative to AQP5, and the higher PH2O of water channels formed from AQP5 relative to AQP0.

Consistent with previous reports (50), measured PH2O in epithelial cells isolated from both mouse (Fig. 5) and rat (Fig. 6) lenses was significantly inhibited by Hg2+ and was higher than the measured PH2O of fiber-derived membrane vesicles. However, the current study revealed significant Hg2+-sensitive water permeability in fiber-derived membrane vesicles isolated from the mouse lens (Fig. 5). The observed range of PH2O values recorded in this study tends to mirror the heterogeneity in membrane versus cytoplasmic labeling of AQP5 and membrane labeling of AQP0 observed immunohistochemically in both lens sections, and in vesicles isolated from cortical fiber cells of the mouse lens. Since a subset of mouse fiber cell membrane vesicles displayed PH2O values equivalent to those observed in the morphologically distinct epithelial cells (Fig. 1A) and this subset of high vesicles with high PH2O was eliminated in the presence of Hg2+, we can conclude that these vesicles contain, in addition to AQP0, the Hg2+-sensitive water channels AQP1/5. Furthermore, since AQP1 expression has been shown to be restricted to the lens epithelium (46), we can assume that the high PH2O permeability observed in this subset of mouse vesicles is mediated by the presence of AQP5 in the membranes of these vesicles. The remaining vesicles exhibited a lower, Hg2+-insensitive PH2O, which we attribute to the sole presence of AQP0 water channels in these particular vesicles. Thus, relative to an earlier study that analyzed PH2O in the mouse lens using a small number of vesicles (51), the larger sample size of our current study provides a more accurate representation of the heterogeneity in abundance and membrane distribution of AQP0 and AQP5 now known to exist in the mouse lens. Our measurements appear to confirm that, in the mouse lens, AQP5 forms a functional water channel which, in combination with AQP0, makes a significant contribution to the water permeability of fiber cells in the outer cortex.

In the rat lens, immunolabeling in lens sections (Figs. 2 and 3) and fiber cell membrane vesicles (Fig. 4) showed that AQP5 was predominantly localized in the cytoplasm. Functional measurement of PH2O were consistent with this cytoplasmic location of AQP5, since PH2O measurements in rat fiber cell membrane vesicles were dominated by a lower Hg2+-insensitive basal PH2O, which can be assigned to AQP0 (Fig. 6). Interestingly, the magnitude of Hg2+-sensitive water permeability measured in rat fiber-derived membrane vesicles was altered by organ culturing rat lenses in isotonic AAH overnight, and this could be correlated with insertion of AQP5 into cortical fiber cell membranes (Fig. 7). AQP5 insertion increased the mean PH2O values, which were subsequently shown to be sensitive to Hg2+ (Fig. 8). Taken together, our localization and functional studies in lenses of two rodent species demonstrate that AQP5 located in the membrane contributes a Hg2+-sensitive component to the water permeability of cortical fiber cells, which is additional to the basal contribution of AQP0 to PH2O. Furthermore, we show that AQP5 exists in the rat lens as a cytoplasmic pool of water channels, which can be dynamically recruited to increase the PH2O of fiber cell membranes in the outer cortex of the lens.

These conclusions raise two questions that deserve further discussion. First, the observation that organ culture of lenses can stimulate the dynamic insertion of AQP5 into the membranes of differentiating fiber cells in both the mouse and rat lens (Fig. 7) raises questions over the pathways that regulate AQP5 membrane insertion in the lens. In other tissues, AQP5 has been found to insert into the apical plasma following phosphorylation of the channel through the cAMP-dependent PKA pathway (58). In addition, exposure to hypertonic challenge was shown to upregulate AQP5 protein expression through an extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)-dependent pathway in mouse lung epithelial (MLE-15) cells (22). Together, these studies suggest that phosphorylation of AQP5 might be an important molecular mechanism regulating AQP5 membrane insertion. Although phosphorylated AQP5 has been reported in the mouse lens (34), only one of the two predicted phosphorylation sites of AQP5 (serine 156, threonine 259) has been detected in lens tissue (53). Further investigation is required to establish the phosphorylation status of cytoplasmic and membranous pools of AQP5, to understand the mechanisms that control the dynamic insertion of AQP5 in specific regions of the lens.

Second, our demonstration that membrane insertion of AQP5 into the differentiating fiber cell membranes increases PH2O does not address the physiological requirement for the lens to dynamically modulate PH2O in the outer cortex. It is interesting to speculate that modulation of PH2O may be required to maintain the gradient in hydrostatic pressure that has been measured in all lenses studied to date (13). This hydrostatic pressure gradient is generated by the flow of water through gap junction channels and ranges from 0 mmHg in the periphery to 335 mmHg in the lens center (14). The pressure gradient is thought to drive intracellular flow of fluid from the lens core to the periphery and is remarkably preserved in lenses from several different species (13). This conservation of the pressure gradient among species has led to the suggestion that the gradient is actively modulated to control the water content in the lens core thereby setting the water/protein ratio which, in turn, determines the gradient of refractive index that contributes to the optical properties of the lens (13). Recently, Gao et al. (15) demonstrated a link between activation of transient receptor potential (TRP) channels, the alteration in Na/K ATPase activity, and the modulation of hydrostatic pressure in the mouse lens. Intriguingly, recent reports have revealed a synergistic association between the mechano-sensitive TRPV4 and aquaporin water channels to affect changes in fluid transportation to preserve cell volume (12, 29, 37). As a working hypothesis it is intriguing to speculate that the dynamic regulation of AQP5 membrane trafficking alters the water permeability of outer cortical fiber cells to modulate the hydrostatic pressure gradient and thereby maintain the optical properties of the lens. Testing this hypothesis should be the focus of future work.

GRANTS

R. S. Petrova was the recipient of a University of Auckland Doctoral Scholarship. The authors acknowledge the support of National Institutes of Health National Eye Institute Grant EY-13462 and a Royal Academy of Engineering/Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EP/G058121/1) Postdoctoral Fellowship (to K. F. Webb).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.S.P. and P.J.D. conceived and designed research; R.S.P. and K.W. performed experiments; R.S.P. and K.F.W. analyzed data; R.S.P., K.F.W., and E.V. interpreted results of experiments; R.S.P. prepared figures; R.S.P. drafted manuscript; K.F.W., E.V., K.W., K.L.S., and P.J.D. edited and revised manuscript; P.J.D. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agre P, King LS, Yasui M, Guggino WB, Ottersen OP, Fujiyoshi Y, Engel A, Nielsen S. Aquaporin water channels—from atomic structure to clinical medicine. J Physiol 542: 3–16, 2002. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.020818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agre P, Preston GM, Smith BL, Jung JS, Raina S, Moon C, Guggino WB, Nielsen S. Aquaporin CHIP: the archetypal molecular water channel. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 265: F463–F476, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ball LE, Garland DL, Crouch RK, Schey KL. Post-translational modifications of aquaporin 0 (AQP0) in the normal human lens: spatial and temporal occurrence. Biochemistry 43: 9856–9865, 2004. doi: 10.1021/bi0496034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bassnett S, Shi Y, Vrensen GFJM. Biological glass: structural determinants of eye lens transparency. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 366: 1250–1264, 2011. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bassnett S, Wilmarth PA, David LL. The membrane proteome of the mouse lens fiber cell. Mol Vis 15: 2448–2463, 2009. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhatnagar A, Ansari NH, Wang L, Khanna P, Wang C, Srivastava SK. Calcium-mediated disintegrative globulization of isolated ocular lens fibers mimics cataractogenesis. Exp Eye Res 61: 303–310, 1995. doi: 10.1016/S0014-4835(05)80125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bok D, Dockstader J, Horwitz J. Immunocytochemical localization of the lens main intrinsic polypeptide (MIP26) in communicating junctions. J Cell Biol 92: 213–220, 1982. doi: 10.1083/jcb.92.1.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bondy C, Chin E, Smith BL, Preston GM, Agre P. Developmental gene expression and tissue distribution of the CHIP28 water-channel protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 4500–4504, 1993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.10.4500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borgnia M, Nielsen S, Engel A, Agre P. Cellular and molecular biology of the aquaporin water channels. Annu Rev Biochem 68: 425–458, 1999. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chandy G, Zampighi GA, Kreman M, Hall JE. Comparison of the water transporting properties of MIP and AQP1. J Membr Biol 159: 29–39, 1997. doi: 10.1007/s002329900266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farjo R, Peterson WM, Naash MI. Expression profiling after retinal detachment and reattachment: a possible role for aquaporin-0. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 49: 511–521, 2008. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galizia L, Pizzoni A, Fernandez J, Rivarola V, Capurro C, Ford P. Functional interaction between AQP2 and TRPV4 in renal cells. J Cell Biochem 113: 580–589, 2012. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao J, Sun X, Moore LC, Brink PR, White TW, Mathias RT. The effect of size and species on lens intracellular hydrostatic pressure. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 54: 183–192, 2013. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-10217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao J, Sun X, Moore LC, White TW, Brink PR, Mathias RT. Lens intracellular hydrostatic pressure is generated by the circulation of sodium and modulated by gap junction coupling. J Gen Physiol 137: 507–520, 2011. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201010538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao J, Sun X, White TW, Delamere NA, Mathias RT. Feedback regulation of intracellular hydrostatic pressure in surface cells of the lens. Biophys J 109: 1830–1839, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gold MG, Reichow SL, O’Neill SE, Weisbrod CR, Langeberg LK, Bruce JE, Gonen T, Scott JD. AKAP2 anchors PKA with aquaporin-0 to support ocular lens transparency. EMBO Mol Med 4: 15–26, 2012. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201100184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonen T, Cheng Y, Sliz P, Hiroaki Y, Fujiyoshi Y, Harrison SC, Walz T. Lipid-protein interactions in double-layered two-dimensional AQP0 crystals. Nature 438: 633–638, 2005. doi: 10.1038/nature04321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gonen T, Sliz P, Kistler J, Cheng Y, Walz T. Aquaporin-0 membrane junctions reveal the structure of a closed water pore. Nature 429: 193–197, 2004. doi: 10.1038/nature02503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grey AC, Li L, Jacobs MD, Schey KL, Donaldson PJ. Differentiation-dependent modification and subcellular distribution of aquaporin-0 suggests multiple functional roles in the rat lens. Differentiation 77: 70–83, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grey AC, Walker KL, Petrova RS, Han J, Wilmarth PA, David LL, Donaldson PJ, Schey KL. Verification and spatial localization of aquaporin-5 in the ocular lens. Exp Eye Res 108: 94–102, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harries WE, Akhavan D, Miercke LJ, Khademi S, Stroud RM. The channel architecture of aquaporin 0 at a 2.2-A resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 14045–14050, 2004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405274101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoffert JD, Leitch V, Agre P, King LS. Hypertonic induction of aquaporin-5 expression through an ERK-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem 275: 9070–9077, 2000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.9070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iandiev I, Pannicke T, Härtig W, Grosche J, Wiedemann P, Reichenbach A, Bringmann A. Localization of aquaporin-0 immunoreactivity in the rat retina. Neurosci Lett 426: 81–86, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iandiev I, Pannicke T, Reichel MB, Wiedemann P, Reichenbach A, Bringmann A. Expression of aquaporin-1 immunoreactivity by photoreceptor cells in the mouse retina. Neurosci Lett 388: 96–99, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ishibashi K, Hara S, Kondo S. Aquaporin water channels in mammals. Clin Exp Nephrol 13: 107–117, 2009. doi: 10.1007/s10157-008-0118-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ishikawa Y, Eguchi T, Skowronski MT, Ishida H. Acetylcholine acts on M3 muscarinic receptors and induces the translocation of aquaporin5 water channel via cytosolic Ca2+ elevation in rat parotid glands. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 245: 835–840, 1998. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ishikawa Y, Skowronski MT, Inoue N, Ishida H. α(1)-adrenoceptor-induced trafficking of aquaporin-5 to the apical plasma membrane of rat parotid cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 265: 94–100, 1999. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacobs MD, Donaldson PJ, Cannell MB, Soeller C. Resolving morphology and antibody labeling over large distances in tissue sections. Microsc Res Tech 62: 83–91, 2003. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jo AO, Ryskamp DA, Phuong TTT, Verkman AS, Yarishkin O, MacAulay N, Križaj D. TRPV4 and AQP4 channels synergistically regulate cell volume and calcium homeostasis in retinal Müller glia. J Neurosci 35: 13525–13537, 2015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1987-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kierdaszuk B. From discrete multi-exponential model to lifetime distribution model and power law fluorescence decay function. J Spectrosc 24: 399–407, 2010. doi: 10.1155/2010/737980. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim I-B, Oh S-J, Nielsen S, Chun M-H. Immunocytochemical localization of aquaporin 1 in the rat retina. Neurosci Lett 244: 52–54, 1998. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(98)00104-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.King LS, Kozono D, Agre P. From structure to disease: the evolving tale of aquaporin biology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5: 687–698, 2004. doi: 10.1038/nrm1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krane CM, Melvin JE, Nguyen HV, Richardson L, Towne JE, Doetschman T, Menon AG. Salivary acinar cells from aquaporin 5-deficient mice have decreased membrane water permeability and altered cell volume regulation. J Biol Chem 276: 23413–23420, 2001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008760200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumari SS, Varadaraj M, Yerramilli VS, Menon AG, Varadaraj K. Spatial expression of aquaporin 5 in mammalian cornea and lens, and regulation of its localization by phosphokinase A. Mol Vis 18: 957–967, 2012. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ladokhin AS, White SH. Alphas and taus of tryptophan fluorescence in membranes. Biophys J 81: 1825–1827, 2001. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75833-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lakowicz JR. On spectral relaxation in proteins. Photochem Photobiol 72: 421–437, 2000. doi:. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36a.Lindsey Rose KM, Wang Z, Magrath GN, Hazard ES, Hildebrandt JD, Schey KL. Aquaporin 0-calmodulin interaction and the effect of aquaporin 0 phosphorylation. Biochemistry 47: 339–347, 2008. doi: 10.1021/bi701980t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu X, Bandyopadhyay BC, Nakamoto T, Singh B, Liedtke W, Melvin JE, Ambudkar I. A role for AQP5 in activation of TRPV4 by hypotonicity: concerted involvement of AQP5 and TRPV4 in regulation of cell volume recovery. J Biol Chem 281: 15485–15495, 2006. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600549200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lovicu FJ, McAvoy JW, de Longh RU. Understanding the role of growth factors in embryonic development: insights from the lens. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 366: 1204–1218, 2011. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mathias RT, Kistler J, Donaldson P. The lens circulation. J Membr Biol 216: 1–16, 2007. doi: 10.1007/s00232-007-9019-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mathias RT, Rae JL, Baldo GJ. Physiological properties of the normal lens. Physiol Rev 77: 21–50, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McAvoy JW, Chamberlain CG, de Longh RU, Hales AM, Lovicu FJ. Lens development. Eye (Lond) 13: 425–437, 1999. doi: 10.1038/eye.1999.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mulders SM, Preston GM, Deen PM, Guggino WB, van Os CH, Agre P. Water channel properties of major intrinsic protein of lens. J Biol Chem 270: 9010–9016, 1995. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.15.9010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patil RV, Saito I, Yang X, Wax MB. Expression of aquaporins in the rat ocular tissue. Exp Eye Res 64: 203–209, 1997. doi: 10.1006/exer.1996.0196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Petrova RS, Schey KL, Donaldson PJ, Grey AC. Spatial distributions of AQP5 and AQP0 in embryonic and postnatal mouse lens development. Exp Eye Res 132: 124–135, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ruiz-Ederra J, Verkman AS. Accelerated cataract formation and reduced lens epithelial water permeability in aquaporin-1-deficient mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 47: 3960–3967, 2006. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Savage DF, Stroud RM. Structural basis of aquaporin inhibition by mercury. J Mol Biol 368: 607–617, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Varadaraj K, Kumari S, Shiels A, Mathias RT. Regulation of aquaporin water permeability in the lens. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 46: 1393–1402, 2005. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Varadaraj K, Kumari SS, Mathias RT. Functional expression of aquaporins in embryonic, postnatal, and adult mouse lenses. Dev Dyn 236: 1319–1328, 2007. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Varadaraj K, Kushmerick C, Baldo GJ, Bassnett S, Shiels A, Mathias RT. The role of MIP in lens fiber cell membrane transport. J Membr Biol 170: 191–203, 1999. doi: 10.1007/s002329900549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang L, Bhatnagar A, Ansari NH, Dhir P, Srivastava SK. Mechanism of calcium-induced disintegrative globulization of rat lens fiber cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 37: 915–922, 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang Z, Han J, David LL, Schey KL. Proteomics and phosphoproteomics analysis of human lens fiber cell membranes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 54: 1135–1143, 2013. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-11168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang Z, Han J, Schey KL. Spatial differences in an integral membrane proteome detected in laser capture microdissected samples. J Proteome Res 7: 2696–2702, 2008. doi: 10.1021/pr700737h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wistow G, Bernstein SL, Wyatt MK, Behal A, Touchman JW, Bouffard G, Smith D, Peterson K. Expressed sequence tag analysis of adult human lens for the NEIBank Project: over 2000 non-redundant transcripts, novel genes and splice variants. Mol Vis 8: 171–184, 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Włodarczyk J, Kierdaszuk B. Interpretation of fluorescence decays using a power-like model. Biophys J 85: 589–598, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74503-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yang B, Verkman AS. Water and glycerol permeabilities of aquaporins 1-5 and MIP determined quantitatively by expression of epitope-tagged constructs in Xenopus oocytes. J Biol Chem 272: 16140–16146, 1997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.26.16140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang F, Kawedia JD, Menon AG. Cyclic AMP regulates aquaporin 5 expression at both transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels through a protein kinase A pathway. J Biol Chem 278: 32173–32180, 2003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305149200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]