Abstract

p66Shc is one of the three adaptor proteins encoded by the Shc1 gene, which are expressed in many organs, including the kidney. Recent studies shed new light on several key questions concerning the signaling mechanisms mediated by p66Shc. The central goal of this review article is to summarize recent findings on p66Shc and the role it plays in kidney physiology and pathology. This article provides a review of the various mechanisms whereby p66Shc has been shown to function within the kidney through a wide range of actions. The mitochondrial and cytoplasmic signaling of p66Shc, as it relates to production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and renal pathologies, is further discussed.

Keywords: adaptor protein p66Shc, kidney diseases, oxidative stress, signal transduction

INTRODUCTION

Renal pathologies, including chronic kidney disease (CKD) and acute kidney injury (AKI), are a continuing health concern both in the US and worldwide. According to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, upwards of 14% of the US population suffers from some form of CKD, with diabetes and hypertension being the major causes (72). Approximately half of US patients with CKD are reported to have diabetes and/or cardiovascular disease (CVD) (72). It is of note that each year more patients die from kidney disease than either prostate cancer or breast cancer (72). Thus, understanding not only the causes of kidney disease but also the mechanisms by which kidney damage occurs is critical for development of therapeutic treatments and potential cures. In this review, we will focus on the Src homology 2 (SH2) domain-containing adaptor protein p66Shc and recent findings of its role in several forms of kidney disease and renal injury. Oxidative stress is a principal player in renal pathologies, and since p66Shc is generally considered to serve as a regulator of sensitivity to oxidative stress (112), p66Shc signaling appears to be relevant for progression of multiple kidney diseases.

Shc PROTEINS

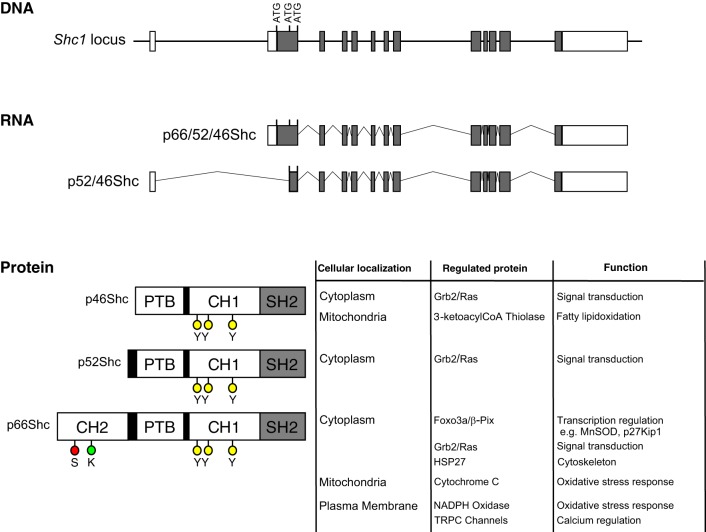

The Shc family of adaptor proteins in mammals includes four members named ShcA (also termed Shc1, Shc adaptor protein 1), ShcB, ShcC, and ShcD, which share the sequential arrangement of NH2-terminal phosphotyrosine domain (PTB), followed by COOH-terminal SH2 domain (30). Whereas ShcB, ShcC, and ShcD proteins are expressed predominately in cells of the nervous system and function in neural development, Shc1 isoforms (products of Shc1 gene) are expressed in a wide variety of tissues, including renal cells (77). The isoforms p66Shc, p52Shc, and p46Shc are named to match their mobility in SDS-PAGE analysis: 66, 52, and 46 kDa. Isoform p66Shc is the largest of three protein isoforms derived from the Shc1 gene (584 vs. 474 amino acids of p52Shc and 429 amino acids of p46Shc in humans). Isoforms p52Shc and p46Shc arise from the utilization of alternative mRNA transcript and additional ATG start codons within the Shc1 gene (Fig. 1) (57, 65, 107). All three Shc isoforms include identical PTB, collagen-homologous (CH) domain-termed CH1, and SH2 domain, whereas only the p66Shc isoform contains a unique second NH2-terminal CH domain-termed CH2 (Fig. 1) (65). Adaptor properties of Shc proteins are due to their capabilities, through PTB and SH2 domains, to bind phosphorylated tyrosine residues within activated growth factor receptors and intracellular dock proteins (104, 106).

Fig. 1.

Structure of Shc1 locus, 2 alternative transcripts, and 3 Shc isoforms, with location, regulated proteins, and assigned function indicated. The Shc1 gene locus consists of 13 exons (white and gray boxes) located on chromosome 1 in humans. Gray boxes indicate coding exons, whereas white boxes represent noncoding regions. The p66Shc, p52Shc, and p46Shc ATG start sites are indicated in exon 2. Use of alternative promoters drives the expression of 2 RNA transcripts, termed the p66/52/46Shc transcript and the p52/46Shc transcript. The p66/52/46Shc transcript contains all 3 ATG start codons for the 3 respective Shc proteins, whereas the p52/46 Shc transcript contains only the ATG start codons for the p52Shc and p46Shc transcripts. Translations of these 2 RNA transcripts yield 3 proteins: p66Shc, p52Shc, and p46Shc. All 3 proteins contain PTB (phosphotyrosine binding), CH1 (collagen homologous region 1), and SH2 (Src homology domain 2), whereas p66Shc contains an additional CH2 (collagen homologous region 2) domain. Relevant serine (red circles; S), lysine (green circle; K), and tyrosine (yellow circles; Y) are indicated. Listed with the protein isoforms are known cellular localizations: regulated proteins and assigned cellular functions.

Shc proteins were initially identified as adaptor proteins associated with action of growth factors and mitogenic signaling, such as Src kinases, members of EGF receptor family, and adaptor protein Grb2 (78, 105, 106), and their link to Ras activation has been the subject of a number of reviews (12, 27, 61). It was in 1997, when Migliaccio et al. (65) described the opposing function of the Shc isoform p66Shc that the mitogenic signaling function of Shc became assigned mostly to the p52Shc isoform, whereas p66Shc started to be recognized for its unique functions in mitochondrial oxidative stress response and changes in lifespan (62, 64, 71, 79, 88).

POSTTRANSLATIONAL MODIFICATIONS OF p66Shc

Crucial for its protein-protein interactions, Shc proteins are phosphorylated on several tyrosine residues in the CH1 domain (diagramed in Fig. 1) (105). Within the CH2 domain unique to p66Shc, the serine residue 36 (Ser36) is phosphorylated, and this regulatory event appears to be critical for p66Shc-specific functions (4, 5, 18, 21, 46, 51, 64, 99). Ser36 phosphorylation has been shown to be imperative for translocation to mitochondria, where p66Shc interacts with cytochrome c (Cyt C), driving increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (35, 73), as reviewed in Refs. 15, 22, 42, and 114. Serine phosphorylation of p66Shc also results in p66Shc association, with cytosolic proteins containing the serine-binding motif, such as adaptor protein 14-3-3 (31).

Most recently, PKCβ isoform of the protein kinase C (PKC) has been shown to regulate p66Shc function in human embryonic kidney (HEK)-293 and primary mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cultures as well as in mouse intestine, liver, lung, and heart tissues under both intestinal ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) and high-dose alcohol conditions (40, 108–110). In mouse tissues, inhibition of PKCβ activity with pharmaceutical inhibitor LY-333531 significantly attenuates p66Shc Ser36 phosphorylation (108, 109). In human fibroblasts, inhibition of PKCβ with hispidin results in decreased Ser36 phosphorylation and decreased ROS production (110). Surprisingly, Haller et al. (40) were unable to confirm the role of Ser36 phosphorlyation in regulating mitochondrial ROS production in HEK-293 and primary MEF cells but indicated that phosphorylation of other sites within the PTB domain, Ser213, and Ser139 was required for mitochondrial ROS production. The differences observed in Haller et al. (40) may reflect tissue or species-specific regulation of p66Shc or could reflect the complexities of observing phosphorylated p66Shc in fully differentiated cell types (108–110). And although the exact mechanism of PKCβ regulation of p66Shc is questionable, the overall impact of PKCβ signaling on p66Shc can be appreciated.

The formation of signaling complex, including guanine exchange factor βPix, ERK1/2, transcription factor FOXO3a, and p66Shc, provides additional mechanistic insight into the network of signaling pathways mediated by p66Shc in the cytoplasm (18). βPix, a molecule possessing both scaffolding and enzymatic properties, facilitates Ser36 phosphorylation of p66Shc in this complex by means of ERK1/2 recruitment (98).

Other posttranslational modifications of p66Shc are also beginning to be explored. In aortic endothelial tissue, p66Shc expression is upregulated and is responsible for increased ROS production and endothelial dysfunction in streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic mice (49, 52). In these studies, p66Shc mitochondrial-mediated ROS production and Ser36 phosphorylation were dependent on acetylation on lysine 81 (Lys81) (49). The NAD(+)-dependent histone deacetylase SIRT1 is capable of deacetylating Lys81 and attenuating p66Shc-dependent ROS production, thus providing further evidence of posttranslational modifications other than Ser36 phosphorylation (49) that are capable of regulating p66Shc function. These data indicate that regulation of p66Shc function is more complex than just Ser36 phosphorylation.

RENAL EXPRESSION OF p66Shc

As indicated in the Human Protein Atlas, Shc1 isoforms are highly expressed in 23 (out of 45 analyzed) organs, including thyroid gland, bone marrow, tonsil, spleen, pancreas, rectum, colon, and small intestine (103). A majority of other organs, including kidney, is listed with a medium level of expression. It must be considered that immunohistochemistry data, as a rule, do not distinguish between the three Shc isoforms. It is generally accepted that isoforms p52Shc and p46Shc are ubiquitously expressed, whereas p66Shc expression is more restricted, which is likely due to utilization of an alternative promotor for p66Shc transcript expression (65, 107). Renal expression of p66Shc has been reported to be higher in male compared with female mouse kidney, presumably because of upregulation of p66Shc by testosterone (92). This testosterone dependency could explain higher sensitivity of the male kidney to AKI (92).

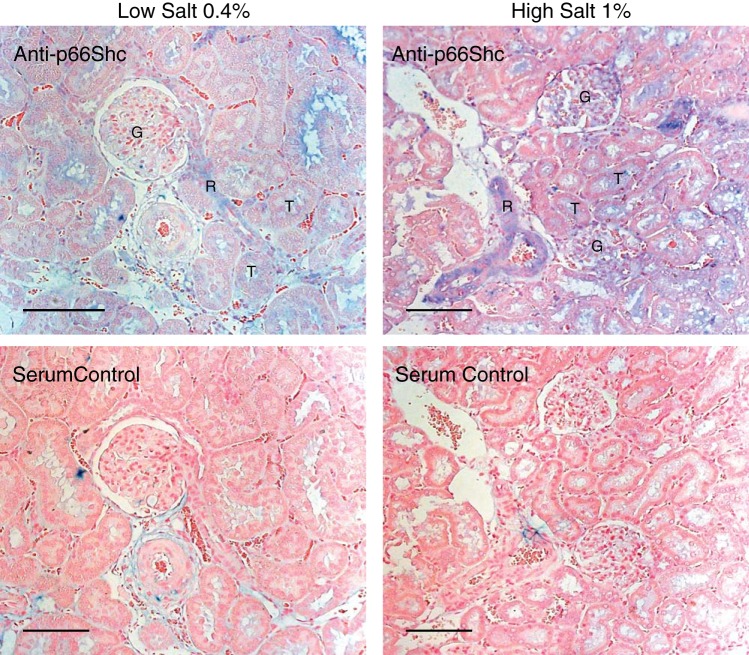

Increased p66Shc expression in a wide variety of cell types within the diseased kidney is the prerequisite for involvement in a number of renal functions and pathologies. Using antibodies specific for p66Shc, expression can be observed in glomerular cells, smooth muscle cells of renal vessels, and tubular cells of hypertensive rats (see Fig. 2). In vitro cultures of primary glomerular mesangial cells, podocytes, renal arteriole smooth muscle cells, and proximal tubule cells all express significant amounts of p66Shc (11, 18, 19, 31, 66). It should be of note, however, that although under cell culture conditions p66Shc is constitutively expressed in all of these cell types of human, rat, and mouse origin (5, 11, 18, 31, 66), in in vivo renal tissues from healthy organisms, p66Shc expression is either low or undetectable by immunohistochemistry (11, 66, 99, 112). Western blot (WB) analysis of whole kidney lysates revealed weak p66Shc expression and some p66Shc Ser36 phosphorylation in normal mouse tissues (21). However, specific cell type cannot be determined by WB in such preparation. It appears that multiple renal tissues and cells have the potential to express p66Shc, but in vivo p66Shc expression, as a rule, is significantly elevated only when some renal injury takes place (4, 99).

Fig. 2.

p66Shc protein expression in salt-sensitive (SS) rats on low- and high-salt diet. p66 Shc protein expression in SS rats on low- and high-salt diet. The level of p66Shc expression (blue) in 15-wk-old Dahl SS rats detected by immunohistochemistry using anti-p66Shc antibody (DaignoCure) was higher in rats fed 1% salt diet (12 wk of diet) than in rats fed 0.4% salt diet. p66Shc is expressed in renal vessels (R), glomeruli (G), and some tubules (T). No staining was seen in serum negative control either at 0.4 or 1% salt diet (bottom). Scale bars, 100 µm.

Dahl salt-sensitive (SS) rats when fed a high-salt diet exhibit many traits associated with human salt-sensitive hypertension and are a regularly used model for the study of salt-sensitive hypertension and accompanying cardiovascular disorders (17). Expression of p66Shc in SS rats is increased in rats fed a 1% salt diet in parallel with development of hypertension-induced nephropathy when compared with rats maintained on low-salt (0.4%) diet (66). The Shc1 gene is located on chromosome 2 in rats, and replacement of rat chromosome 2 of SS rats with a corresponding chromosome from the salt-resistant Brown Norway (BN) rats (hereafter referred to as SS/BN2) increased survival rate and protected the animals from the development of hypertension-induced renal injury when the rats were fed a 1% salt diet (66). Consomic SS/BN2 rats express little p66Shc in the vascular smooth muscle cells (SMC) of the renal interlobar arteries or afferent arterioles (as revealed by immunohistochemistry). The presence of a number of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the Shc1 promoter region may account for the differential expression of p66Shc in SS and SS/BN2 rats (66). Additionally, in humans with diabetic nephropathy and in mice with experimentally induced diabetes, p66Shc expression also is significantly increased in renal proximal tubules in a response to the oxidative damage, whereas it is almost undetectable in normal control tissues (99, 112). It appears that in vitro cultures of the various cell types experience constant stress, which drives p66Shc expression up. The constitutive in vitro expression of p66Shc allows for the study of p66Shc functions under pathological conditions but may hinder evaluation of p66Shc functions in normal, healthy cells. To this end, the development of p66Shc knockout mice, and more recently, p66Shc knockout rats, is invaluable, as these models will allow for the examination of p66Shc in an in vivo context in both healthy and disease states (64, 66, 101).

ANIMAL MODELS WITH MODIFIED Shc1 GENE

In initially developed p66Shc-knockout mice, the depletion of p66Shc increased the lifespan of laboratory mice by ∼30%, which was attributed to increased resistance to oxidative stress, changes in mitochondrial biogenesis, and decreased apoptosis (64, 70, 102). The role of p66Shc in oxidative stress has been further confirmed in experiments utilizing in vitro cultures of various renal cell types (4, 5, 11). Furthermore, it was found that loss of p66Shc results in reduction of oxidative stress that accompanies diabetic nephropathy and that there was an overall net protective effect (62).

Potentially confounding the role of p66Shc in longevity in this initial p66Shc-knockout mouse strain, however, is the fact that p46Shc expression is more than fourfold upregulated compared with control mice, accompanied by a decrease in p52Shc expression (101). Furthermore, the second independently generated line of p66Shc-knockout mice exhibited normal levels of p52Shc and p46Shc (101) but failed to display the increased lifespan (90). The above-mentioned p66Shc-knockout mice, however, were susceptible to fatty diets, were fatter, and their adipose was more insulin sensitive than controls, suggesting that Shc locus regulates insulin signaling and adiposity in mammals (101). Interestingly, the increased lifespan of the p66Shc-knockout mice, developed by Napoli et al. (70), was observed under laboratory conditions. When the same p66Shc-knockout mice (101) were tested in “natural” conditions, p66Shc-knockout mice were naturally selected against compared with wild-type cohorts (34).

Recently, we have reported the generation of p66Shc-knockout rats on the genetic background of Dahl SS (66). With the use of zinc finger nuclease (ZFN) technology, deletions were introduced into the Shc1 gene locus that was unique for p66Shc, resulting in predicted truncation and loss of p66Shc protein. The deletions are upstream of the initiating codons for p52Shc and p46Shc transcript, and we do not observe changes in p52Shc and p46Shc isoforms (66). These rats do not have an extended lifespan, as observed in the initial p66Shc-knockout mice. There are data to suggest that loss of p66Shc in SS rats does have a protective effect against increased oxidative stresses, i.e., hypertension-induced renal injury (66). This paired with the data from the second independently generated p66Shc-knockout mice suggests that p66Shc is not a longevity protein but suggests, rather, that the perturbations of p46Shc and p52Shc expressions accompanied by loss of p66Shc result in the increased lifespan. However, a lot can still be learned about p66Shc and its role in sensing and potentiating oxidative stress responses in cells.

Additionally, because it has been established that Ser36 phosphorylation is required for mitochondrial transport and function in oxidative stress response (4), we generated a point mutation in the Ser36 residue, substituting alanine for serine, termed S36A rats. To generate S36A rats, the template plasmid encoding a Ser36 Ala substitution (T > G transversion), was coinjected in one cell embryo along with ZFNs targeting exon 2 of the Shc1 gene in close proximity to the codon encoding p66Shc Ser36. The utilization of both the total p66Shc knockout and the S36A-knockin rats should enable further studies to characterize a role for p66Shc in the mitochondria and distinguish phenotypes associated with cytosolic p66Shc. Indeed, we were able to establish a role of non-Ser36-phosphorylated p66Shc in the regulation of transient receptor potential canonical (TRPC) channels in renal smooth muscle cells (SMC) (66). Whether Ser36 phosphorylation-mediated interaction of p66Shc with other signaling molecules in the cytoplasm (such as adaptor protein 14-3-3) is important for cellular reactions to stress signals remains to be determined. Nevertheless, it appears that there is a significant role for p66Shc in cytosol, where it can form multiunit signaling complexes. Therefore, ours as well as studies by others clearly indicate that p66Shc action is not limited only to ROS production (18, 66, 111, 115). Thus, rat strain expressing S36A p66Shc mutant can be helpful in understanding mechanisms of cytosolic vs. mitochondrial and oxidative vs. nonoxidative stress responses.

p66Shc AND OXIDATIVE STRESS AND APOPTOSIS

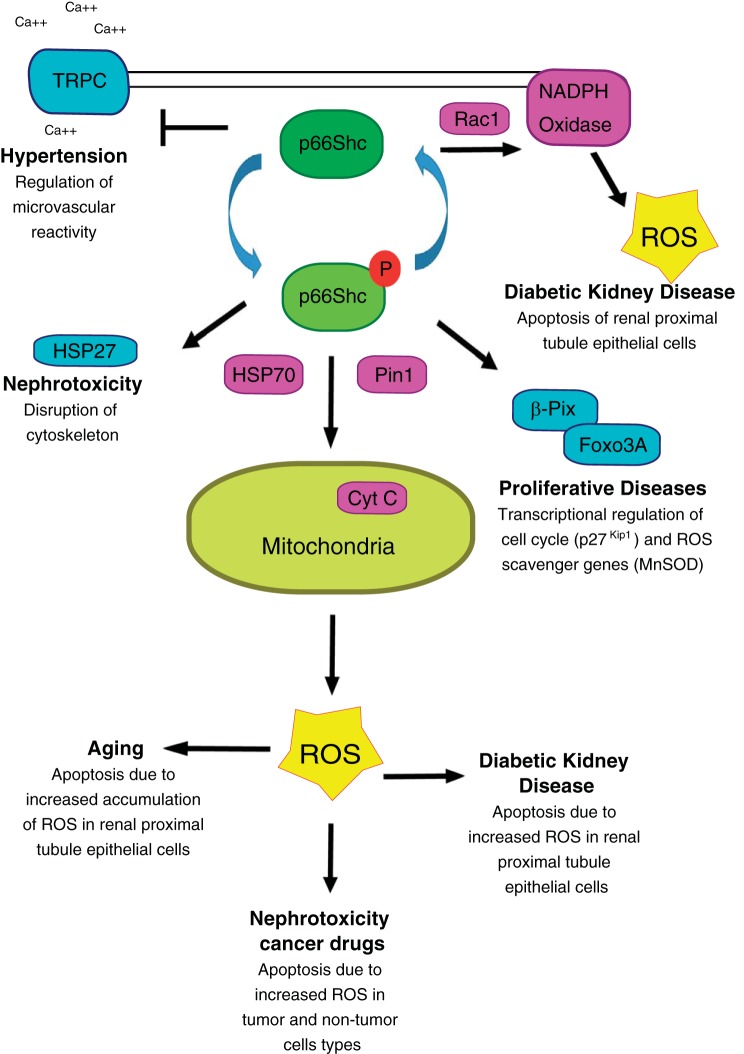

Because the role of p66Shc in the oxidative stress response and apoptosis has been widely studied (10, 32, 59, 66, 88, 114), it will be summarized only briefly here. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are highly reactive molecules because of the presence of unpaired electrons. ROS are formed by partial reduction in oxygen (91), and there are three major mechanisms by which a cell increases intracellular ROS levels: increased oxidase activity, decreased ROS scavenging, and mitochondrial production from the electron transport chain (33, 85, 91, 114). Remarkably, p66Shc has the potential to play an important role in all three mechanisms (Fig. 3). p66Shc is capable of regulating the activity of the plasma membrane-bound NADPH oxidase to generate ROS through Grb2-mediated activation of Rac1 (33, 74, 100). Conversely, p66Shc reduces ROS scavenging by downregulating the expression of the scavengers MnSod and glutathione peroxidase through interactions with βPix and FOXO3a. Under normal conditions, transcription factor FOXO3a is located in the nucleus driving transcription of the scavengers. Under oxidative stress, p66Shc forms a complex with βPix that is able to sequester FOXO3a in the cytosol, attenuating expression of scavenger genes as well as promoting proliferation (18, 33). The third mechanism of ROS production, mitochondrial production of ROS from the electron chain, is also influenced by p66Shc. Ser36 phosphorylation triggers a Pin1-mediated conformational change in p66Shc and consequent translocation of p66Shc into the mitochondria (86). Presumably, Pin1 activity on p66Shc induces a conformational change of p66Shc by causing cis-trans isomerization of p-Ser36 to Pro37 (86). This change allows p66Shc to interact with TIM/TOM and SHP70 proteins of the mitochondria (73). TIM/TOM proteins are mitochondrial membrane proteins responsible for transporting proteins from the cytosol into the mitochondrial matrix space. Once inside the mitochondria, p66Shc can act as an oxidoreductase transferring electrons from Cyt C to oxygen-producing ROS as reviewed in Ref. 114.

Fig. 3.

Involvement of p66Shc in renal pathologies. Schematic diagram of p66Shc function and key regulated proteins involved in indicated renal pathologies. Teal-colored proteins indicate p66Shc interactions that are not involved in the production of ROS, whereas pink-colored proteins indicate interactions that lead to the direct production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) within the cells. Non-Ser36-phosphorylated p66Shc has been shown to inhibit transient receptor potential canonical (TRPC) channels as well as regulate NAPDH oxidase activity in a Rac-1-dependent manner. Ser36 phosphorylated p66Shc is known to interact with HSP27 to disrupt cytoskeleton in some cases of nephrotoxicity as well as form a complex with β-Pix and Foxo3a to regulate cell cycle progression and regulate gene expression of ROS scavengers. The more commonly known function of Ser36-phosphorylated p66Shc is its heat shock protein 70 (HSP70)- and Pin1-dependent mitochondrial ROS production through interactions with cytochrome c (Cyt C). Increased ROS due to p66Shc translocations have been shown to be involved in age-related renal pathologies and diabetic kidney disease and are a source of nephrotoxicity in some anti-cancer treatments.

p66Shc action as an oxidoreductase and subsequent reduction of oxygen and increased ROS production can trigger the formation of a mitochondrial permeability pore, inducing swelling of the mitochondria and resulting in a release of Cyt C into the cytosol. Release of Cyt C is known to trigger activation of caspases, which forces the cell down the apoptotic pathway (35, 42).

p66Shc AND AGE-RELATED RENAL PATHOLOGIES

Aging is a complex process that all living organisms experience. As cells age, they accumulate damage and experience increased oxidative stress, resulting in decreased function. It is generally accepted that p66Shc protein serves as an oxidative stress sensor (33, 88, 114). In aged cells, accumulation of oxidative stress can activate p66Shc-dependent mitochondrial apoptotic response (Fig. 3) (102). The kidneys are particularly susceptible to aging (80–82). Tissues such as the proximal tubules have large amounts of mitochondria and are sensitive to oxidative injury (4), which may explain the sensitivity of the kidney to oxidative damage that accumulates with age. p66Shc plays significant role in signaling cascades mediated by vasoactive peptide endothelin-1 (ET-1), whose actions are associated with renal age-related pathologies (96). Thus, renal mesangial cells release ET-1 in response to a variety of factors, many of which are elevated in glomerular injury (97). ET-1 action leads to podocyte damage and induces tubular ER stress and apoptosis (25), the pathologies associated with old age (7, 16, 97).

p66Shc AND HYPERTENSION-INDUCED NEPHROPATHY

Hypertension often results in development of renal pathologies, with hypertension being one of the leading contributors of end-stage renal failure (13). The well-recognized contributor to vascular dysfunction in hypertension is increased oxidative stress (13, 67, 68). Increased vascular pressure increases ROS production primarily through increased NAPDH oxidase activity (48, 93). This increased ROS ultimately results in vascular hypertrophy and dysfunction.

Within the kidney, renal vasculature plays a key role in regulating blood flow and filtration through the glomerulus. Renal afferent and efferent arterioles maintain a pressure gradient between the large renal vessels and renal capillaries. The renal vasculature in the Dahl SS hypertensive rats has an impaired ability to respond to increased blood pressure. This increased pressure within the afferent arterioles is transmitted to the capillaries and results in glomerular damage (14, 66). As described above, we have reported that SS hypertensive rats exhibit increased p66Shc expression in the renal medulla compared with normotensive rats (66). Loss of p66Shc has been shown to restore vascular responsiveness within the afferent arterioles in response to high pressure and ATP, whereas the S36A substitution does not have the same effect (66). This is consistent with the potential role of p66Shc (and S36A mutation) maintaining NAPDH oxidase activity at the plasma membrane and continuing to produce damaging ROS (33, 74). These data provide further evidence that p66Shc functions outside the mitochondria to regulate oxidative stress.

Interestingly, a potentially non-ROS dependent function of p66Shc was also uncovered in studies of hypertension-induced nephropathy. Electrophysiological analysis of cultured renal smooth muscle cells from the p66Shc-knockout rats showed increased activation of TRPC channels and subsequent increases in intracellular calcium import compared with wild-type SMCs (66). Additionally, S36A mutant SMC exhibited decreased TRPC channel activity, suggesting that cytosolic retention of p66Shc functions as an inhibitor of TPRC channel activity (66). Increased calcium import is required for smooth muscle cell contraction. In wild-type smooth muscle cells, before stimulation, p66Shc, localized in cytosol, inhibits TRPC channel activity. Upon stimulation, translocation of p66Shc to the mitochondria releases inhibition of TRPC channel activity. Because hypertension stress causes upregulation of p66Shc expression in the renal SMC, it is possible that the increased p66Shc protein is further inhibiting TRPC channels, resulting in lack of responsiveness observed in the afferent arterioles of hypertensive rats (Fig. 3) (66). Autoregulatory control of preglomerular resistance is an essential component of normal renal hemodynamics and appropriate adjustments in this mechanism of control glomerular filtration pressure.

p66Shc AND DIABETIC NEPHROPATHY

Hyperglycemic conditions associated with diabetes have a profound effect on the kidney, including changes in glomerular mesangial cell functions resulting in increased matrix deposition, thickening of basement membrane, and expansion and proliferation of the mesangial cells, termed glomerular sclerosis (84). TRPC channels were shown to be expressed in mesangial cells (36–38, 58, 94) and are known to be critical for normal mesangial cell contractile function (28, 53) and proliferation (44, 47, 89). High-glucose conditions associated with hyperglycemia reduce TRPC6 channel expression in mesangial cells (37) and increase its expression in podocytes (43). At the same time, diabetic conditions are known to upregulate p66Shc protein expression in tissues such as renal tubules and in glomeruli (99, 112). Because it has been shown that p66Shc expression negatively regulates TRPC channel activity in SMC, it is likely that a similar mechanism exists in mesangial cells. The decrease in TRPC channel expression and the potential inhibition of TRPC channel activity by p66Shc most likely accounts for the net decrease in mesangial cell contraction observed under hyperglycemic growth conditions (28). Connections between p66Shc and TRPC6 channels in podocytes, if present, remain to be explored, as increased expression of both proteins appear counterintuitive. It is more likely that each protein in these cells may be acting independently, and p66Shc may be functioning primarily as a mediator of oxidative stress dysfunction and promoting apoptosis (11). Adding to the complexity of TRPC/p66Shc interactions under hyperglycemic conditions, increased p66Shc expression may influence proliferation. As discussed above, p66Shc is able to complex with βPix and FOXO3a in the cytosol. The sequestration of FOXO3a away from the nucleus downregulates the expression of p27Kip1 (18). p27Kip1 is a known regulator of proliferation, and its action as a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor is responsible for blocking cell cycle progression at G1 (26). Future experiments may provide further insights into p66Shc function in mesangial cell dysfunction in diabetic nephropathy and other proliferative diseases.

Increased oxidative stress within the kidney is also a well-known contributor to progression of diabetic nephropathy (32, 62, 112, 114). The role of p66Shc as a sensor and mediator of oxidative stress is highlighted by its reported increased expression in proximal tubule cells and podocytes in STZ-induced diabetic mice and other genetic models of diabetes (11, 99). Upregulation of both total and Ser36-phosphorylated p66Shc coincided with increased production of mitochondrial ROS and increased apoptosis (Fig. 3) (11, 99). Supporting the role of p66Shc as an inducer of ROS in diabetic nephropathy, STZ-induced p66Shc-knockout mice displayed decreased glomerular damage, decreased apoptosis, decreased Nox4 gene expression, and decreased ROS production (62, 63). It is of note that Nox4 protein is part of the plasma membrane NAPDH oxidase system, suggesting that both mitochondrial and plasma membrane ROS production provide a net ROS increase in diabetic nephropathy. Furthermore, p66Shc expression has recently been suggested as a biomarker for diabetic nephropathy in humans, as increased p66Shc expression in blood monocytes was shown to correlate with increased oxidative stress in diabetic patients compared with healthy controls (76, 114).

As described above, in aortic endothelial cells of diabetic mice, p66Shc is upregulated and its function regulated by Lys81 acetylation, whereas Sirt1 deacetylates and attenuates p66Shc function (49). Hyperglycemic conditions promote acetylation of p66Shc (49, 52). As part of a complex feedforward loop, it was recently described that increased p66Shc expression in hyperglycemic diabetic endothelial cells induces microRNA-34a expression, which in turn targets Sirt1 mRNA, decreasing Sirt1 protein (52). Decreased Sirt1 protein expression, along with increased p66Shc expression and acetylation, increases ROS production further in the endothelial cell, promoting increased cellular dysfunction. Additionally, probucol, a potent antixodant drug that can delay progression of diabetic nephropathy, was reported to ameliorate renal damage in diabetic nephropathy by epigenetically suppressing p66Shc expression via the AMP-activated protein kinase/SIRT1/acetyl/histone H3 pathway (113). Whether this complex feedforward loop is present in renal proximal tubular cells or within the glomerular mesangial cells within the kidney remains to be explored, but it may explain the progressive dysfunction of these cell types as well.

p66Shc AND RENAL TOXICITY OF ANTICANCER AGENTS

The involvement of p66Shc in the progression of nephrotoxicity associated with anticancer therapies is probable (Fig. 3). Renal toxicity was reported for a variety of anticancer therapies targeting members of the epidermal growth factors (EGF) and the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling cascades (23, 24, 87). Kidney is a highly vascularized organ, and agents against VEGF and VEGF receptors (VEGFRs) will affect renal microvasculature. As discussed above, p66Shc when overexpressed in SMC of renal vessels promotes vascular dysfunction, resulting in proteinuria (likely to be caused by vascular dysfunction-mediated glomerular damage) and other hypertension-induced renal injuries (66). It is of note that p66Shc was reported to act as a positive regulator for ROS-dependent VEGF signaling and is supposed to act downstream of VEGFR (74). Accordingly, renal toxicities, which appear to be quite common in cancer patients treated with anticancer drugs targeting VEGF and VEGFRs (23), could be mediated by p66Shc signaling which compensates for the inhibited VEGFR activity. The connection between anti-VEGF cancer treatments and p66Shc remains to be explored. Future research will establish whether p66Shc could serve as a therapeutic target to combat the renal toxicity associated with these types of cancer treatments. In contrast, the interaction of drugs targeting EGF and EGF receptors used in cancer treatment with p66Shc signaling has not been reported. Most of these drugs, as a single agent, do not induce nephrotoxicity, and in general, kidney toxicity is not very common with this class of agents (24). Thus, there is insufficient rationale to consider p66Shc as a therapeutic target when HER2 and EGFR inhibitors are used.

It has been observed that the epigenetic modifying anti-cancer drugs trichostatin A (TSA) and 5-aza-cytidine (5AZA) induce renal tubular injury in part by increasing mitochondrial ROS production (69) and that this ROS corresponds to increased expression and mitochondrial localization of p66Shc (2, 107). Interestingly, in a recent study by Arany et al. (6), it was observed that nicotine exposure augments the renal toxic effects of 5AZA. Whereas previous reports have indicated links of nicotine exposure to increased renal damage via p66Shc-mediated oxidative stress (1, 45), this study demonstrated further increased damage induced to the renal tubules due to the combination of 5AZA and nicotine. These data suggest both a mechanism to a phenomenon that has been plaguing physicians trying to treat cancer patients (39, 83) and also proposes that the antioxidant resveratrol could be used a therapeutic treatment to decrease the p66Shc-induced oxidative stress induced both by the anti-cancer treatment as well as nicotine exposure (6).

Nephrotoxicity is one of the main side effects of the potent platinum-containing cytostatic drug cisplatin (60). Cisplatin, like most metals, is involved in generation of ROS and causes tubular damage, vascular injury, and inflammatory damage in the interstitium (75). Mechanisms of action of cisplatin, as well as many other anticancer drugs, include cytoplasmic organelle dysfunction (including mitochondrial damage), oxidative stress, and induction of apoptotic pathways (60). Accordingly, the involvement of p66Shc as a facilitator of ROS production and mediator of oxidative stress-dependent renal damage in renal toxicity of anticancer agents is probable. Indeed, overexpression of p66Shc exacerbates whereas its knockdown or mutation of the Ser36 site to alanine ameliorates cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity in cultured renal proximal tubule epithelial cells (21, 116). It was proposed that p66Shc accelerates cisplatin-dependent disorganization of the actin cytoskeleton through interacting with heat shock protein 27 (HSP27), which is responsible for the integrity of the actin cytoskeleton (Fig. 3) (3). It seems imperative to carry out experiments with rodent models of p66Shc-knockout to establish whether p66Shc-mediated cisplatin-dependent nephrotoxicity takes place not only in vitro in cell models but also in vivo in animals treated with cisplatin.

POTENTIAL THERAPEUTICS

Many of the renal diseases discussed in the current review exhibit deleterious effects on the kidney due to increased oxidative stress, and p66Shc protein expression plays a central role in this increase. As such, p66Shc is emerging as a target for therapeutic strategies to mitigate oxidative stress-induced damage. As theoretical proof of concept, Bock et al. (11) were able to show that activated protein C (aPC) silences p66Shc expression via epigenetic modification of the p66Shc promoter. The epigenetic silencing of p66Shc coincided with an aPC-mediated decrease in ROS production, as well as decreased p66Shc translocation to the mitochondria (11). Similarly, it has been shown that the NAD(+)-dependent histone deacetylase SIRT1 is able to not only suppress p66Shc expression but through lysine 81 deacetylation of p66Shc block normal p66Shc function and reduce ROS production in vascular endothelial cells (49, 117). Similarly, inhibiting translocation of p66Shc to the mitochondria using the Pin1 inhibitor juglone enabled the attenuation of intestinal I/R injuries in rat typified by p66Shc function in the intestines caused by I/R damage (29). These data provide intriguing evidence that inhibiting p66Shc could have therapeutic effects.

A promising new synthetic anti-cancer compound, Sulfur Het A2 (SHetA2), that induces apoptosis in a vast array of cancer cell types while having little effect on noncancerous cell types, has been described (8, 54–56). One of the mechanisms by which SHetA2 induces apoptosis was shown to be through direct interactions in the mitochondria and generation of increased ROS (54, 55). This compound was recently found to inhibit p66Shc and Hsp70 (mortalin/HSPA9) interactions (9). Hsp70 is predominately localized to the mitochondria and functions as a chaperone protein, mediating interactions with p66Shc and TIM/TOM proteins (see Ref. 114 for a review). Treatment of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells with SHetA2 induced mitochondrial swelling, increased Cyt C release from mitochondria, and increased apoptosis (20), which is consistent with increased p66Shc actions in the mitochondria when activated and released from the TIM/TOM complex. Surprisingly, in the kidney cancer cell lines, SHetA2 induced apoptosis, although it had no effect on renal tubule cells (56). Furthermore, treatment of kidney cancer xenografts with SHetA2 resulted in decreased growth over a range of SHetA2 dosages (20). These data suggest that SHetA2 could provide an effective treatment for some proliferative kidney diseases, such as renal cancers, and diabetic mesangial proliferative nephropathy. Whether SHetA2 could interfere with signaling of p66Shc in renal cells in other kidney pathologies and thus ameliorate renal function remains to be determined.

To date, there are no specific pharmaceutical inhibitors of the p66Shc protein. The similarity between the p66Shc isoform and p52Shc and p46Shc significantly reduces targetable regions of the p66Shc protein. Inhibition of all three isoforms is likely to have significant deleterious consequences, as a knockout of all three isoforms in mice was embryonic lethal (50). However, if one were to be able to specifically target p66Shc, either pharmaceutically or through permanent genetic modification of the Shc1 locus, the therapeutic potential is great. Recent advances in CRISPR-Cas9 system technology have opened the door to targeted genetic modification of gene loci as applications to treat human diseases (reviewed in Ref. 41). The potential to utilize nanoparticles or other delivery methods to deliver p66Shc loci CRISPR targeted constructs to diseased kidneys as a method of reducing p66Shc protein expression is intriguing. However, before this technology can be used, targeting efficiency, as well as limiting off-target effects, needs to improve.

CONCLUSIONS

To conclude, the kidney is particularly sensitive to increases in oxidative stress, be it caused by hypertension, diabetic-induced hyperglycemia, or even the normal aging process. As reviewed here, p66Shc appears to play a critical role in the progression and aggravation of the disease states (Fig. 3). Although work continues to show the importance of p66Shc in these and other kidney diseases, functional studies need to be expanded to further clarify where in the cells p66Shc is acting, i.e., at the plasma membrane with NADPH oxidase, in the mitochondria driving Cyt C-mediated apoptosis, or in the cytosol mediating downregulation of the FOXO3a-dependent genes such as MnSOD or p27Kip1. Although it is likely that each disease state is unique, and various combinations of p66Shc functions take place, understanding the mechanisms of p66Shc-mediated renal pathologies will further guide the development of therapeutic compounds targeting p66Shc actions and expression.

Finally, nonoxidative stress-inducing roles of p66Shc are just being recognized. The fact that p66Shc has been shown to negatively regulate TRPC channels in renal cells suggests that p66Shc is a node linking broader biological functions (66). Aberrant TRPC channel expression and dysregulated calcium import have been implicated in mesangial cell dysfunction and podocyte injury under hyperglycemic conditions (37, 38, 44, 58, 95). If p66Shc functions to regulate TRPC channels in these cells as seen in renal smooth muscle cells, therapeutic inhibition of p66Shc could not only help to decrease oxidative stress but also aid in other aspects of dysregulated cellular functions.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01-DK-098159 and R03-CA-182114 to A. Sorokin and R01-HL-122662 and R25-HL135749 to A. Staruschenko. This work was also supported by a Medical College of Wisconsin Cancer Center Independent Research Seed Grant to A. Sorokin.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

K.D.W. and A. Sorokin drafted manuscript; K.D.W., A. Staruschenko, and A. Sorokin edited and revised manuscript; K.D.W., A. Staruschenko, and A. Sorokin approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arany I, Clark J, Reed DK, Juncos LA. Chronic nicotine exposure augments renal oxidative stress and injury through transcriptional activation of p66shc. Nephrol Dial Transplant 28: 1417–1425, 2013. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arany I, Clark JS, Ember I, Juncos LA. Epigenetic modifiers exert renal toxicity through induction of p66shc. Anticancer Res 31: 3267–3271, 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arany I, Clark JS, Reed DK, Ember I, Juncos LA. Cisplatin enhances interaction between p66Shc and HSP27: its role in reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton in renal proximal tubule cells. Anticancer Res 32: 4759–4763, 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arany I, Faisal A, Clark JS, Vera T, Baliga R, Nagamine Y. p66SHC-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction in renal proximal tubule cells during oxidative injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298: F1214–F1221, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00639.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arany I, Faisal A, Nagamine Y, Safirstein RL. p66shc inhibits pro-survival epidermal growth factor receptor/ERK signaling during severe oxidative stress in mouse renal proximal tubule cells. J Biol Chem 283: 6110–6117, 2008. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708799200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arany I, Hall S, Faisal A, Dixit M. Nicotine exposure augments renal toxicity of 5-aza-cytidine through p66shc: prevention by resveratrol. Anticancer Res 37: 4075–4079, 2017. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.11793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barton M, Sorokin A. Endothelin and the glomerulus in chronic kidney disease. Semin Nephrol 35: 156–167, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benbrook DM, Kamelle SA, Guruswamy SB, Lightfoot SA, Rutledge TL, Gould NS, Hannafon BN, Dunn ST, Berlin KD. Flexible heteroarotinoids (Flex-Hets) exhibit improved therapeutic ratios as anti-cancer agents over retinoic acid receptor agonists. Invest New Drugs 23: 417–428, 2005. doi: 10.1007/s10637-005-2901-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benbrook DM, Nammalwar B, Long A, Matsumoto H, Singh A, Bunce RA, Berlin KD. SHetA2 interference with mortalin binding to p66shc and p53 identified using drug-conjugated magnetic microspheres. Invest New Drugs 32: 412–423, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s10637-013-0041-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhat SS, Anand D, Khanday FA. p66Shc as a switch in bringing about contrasting responses in cell growth: implications on cell proliferation and apoptosis. Mol Cancer 14: 76, 2015. doi: 10.1186/s12943-015-0354-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bock F, Shahzad K, Wang H, Stoyanov S, Wolter J, Dong W, Pelicci PG, Kashif M, Ranjan S, Schmidt S, Ritzel R, Schwenger V, Reymann KG, Esmon CT, Madhusudhan T, Nawroth PP, Isermann B. Activated protein C ameliorates diabetic nephropathy by epigenetically inhibiting the redox enzyme p66Shc. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 648–653, 2013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218667110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonfini L, Migliaccio E, Pelicci G, Lanfrancone L, Pelicci PG. Not all Shc’s roads lead to Ras. Trends Biochem Sci 21: 257–261, 1996. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(96)10033-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Briones AM, Touyz RM. Oxidative stress and hypertension: current concepts. Curr Hypertens Rep 12: 135–142, 2010. doi: 10.1007/s11906-010-0100-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burke M, Pabbidi MR, Farley J, Roman RJ. Molecular mechanisms of renal blood flow autoregulation. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 12: 845–858, 2014. doi: 10.2174/15701611113116660149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Camici GG, Sudano I, Noll G, Tanner FC, Lüscher TF. Molecular pathways of aging and hypertension. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 18: 134–137, 2009. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e328326093f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Camici M, Carpi A, Cini G, Galetta F, Abraham N. Podocyte dysfunction in aging—related glomerulosclerosis. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) S3: 995–1006, 2011. doi: 10.2741/204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campese VM. Salt sensitivity in hypertension. Renal and cardiovascular implications. Hypertension 23: 531–550, 1994. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.23.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chahdi A, Sorokin A. Endothelin-1 couples betaPix to p66Shc: role of betaPix in cell proliferation through FOXO3a phosphorylation and p27kip1 down-regulation independently of Akt. Mol Biol Cell 19: 2609–2619, 2008. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-05-0424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chahdi A, Sorokin A. Endothelin-1 induces p66Shc activation through EGF receptor transactivation: Role of beta(1)Pix/Galpha(i3) interaction. Cell Signal 22: 325–329, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chun KH, Benbrook DM, Berlin KD, Hong WK, Lotan R. The synthetic heteroarotinoid SHetA2 induces apoptosis in squamous carcinoma cells through a receptor-independent and mitochondria-dependent pathway. Cancer Res 63: 3826–3832, 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clark JS, Faisal A, Baliga R, Nagamine Y, Arany I. Cisplatin induces apoptosis through the ERK-p66shc pathway in renal proximal tubule cells. Cancer Lett 297: 165–170, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cosentino F, Francia P, Camici GG, Pelicci PG, Lüscher TF, Volpe M. Final common molecular pathways of aging and cardiovascular disease: role of the p66Shc protein. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 28: 622–628, 2008. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.156059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cosmai L, Gallieni M, Liguigli W, Porta C. Renal toxicity of anticancer agents targeting vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptors (VEGFRs). J Nephrol 30: 171–180, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s40620-016-0311-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cosmai L, Gallieni M, Porta C. Renal toxicity of anticancer agents targeting HER2 and EGFR. J Nephrol 28: 647–657, 2015. doi: 10.1007/s40620-015-0226-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Miguel C, Speed JS, Kasztan M, Gohar EY, Pollock DM. Endothelin-1 and the kidney: new perspectives and recent findings. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 25: 35–41, 2016. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dijkers PF, Medema RH, Pals C, Banerji L, Thomas NS, Lam EW, Burgering BM, Raaijmakers JA, Lammers JW, Koenderman L, Coffer PJ. Forkhead transcription factor FKHR-L1 modulates cytokine-dependent transcriptional regulation of p27(KIP1). Mol Cell Biol 20: 9138–9148, 2000. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.24.9138-9148.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Downward J. Control of ras activation. Cancer Surv 27: 87–100, 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Du J, Sours-Brothers S, Coleman R, Ding M, Graham S, Kong DH, Ma R. Canonical transient receptor potential 1 channel is involved in contractile function of glomerular mesangial cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 1437–1445, 2007. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006091067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feng D, Yao J, Wang G, Li Z, Zu G, Li Y, Luo F, Ning S, Qasim W, Chen Z, Tian X. Inhibition of p66Shc-mediated mitochondrial apoptosis via targeting prolyl-isomerase Pin1 attenuates intestinal ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. Clin Sci (Lond) 131: 759–773, 2017. doi: 10.1042/CS20160799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Finetti F, Savino MT, Baldari CT. Positive and negative regulation of antigen receptor signaling by the Shc family of protein adapters. Immunol Rev 232: 115–134, 2009. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Foschi M, Franchi F, Han J, La Villa G, Sorokin A. Endothelin-1 induces serine phosphorylation of the adaptor protein p66Shc and its association with 14-3-3 protein in glomerular mesangial cells. J Biol Chem 276: 26640–26647, 2001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102008200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Francia P, Cosentino F, Schiavoni M, Huang Y, Perna E, Camici GG, Lüscher TF, Volpe M. p66(Shc) protein, oxidative stress, and cardiovascular complications of diabetes: the missing link. J Mol Med (Berl) 87: 885–891, 2009. doi: 10.1007/s00109-009-0499-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Galimov ER. The role of p66shc in oxidative stress and apoptosis. Acta Naturae 2: 44–51, 2010. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giorgio M, Berry A, Berniakovich I, Poletaeva I, Trinei M, Stendardo M, Hagopian K, Ramsey JJ, Cortopassi G, Migliaccio E, Nötzli S, Amrein I, Lipp HP, Cirulli F, Pelicci PG. The p66Shc knocked out mice are short lived under natural condition. Aging Cell 11: 162–168, 2012. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Giorgio M, Migliaccio E, Orsini F, Paolucci D, Moroni M, Contursi C, Pelliccia G, Luzi L, Minucci S, Marcaccio M, Pinton P, Rizzuto R, Bernardi P, Paolucci F, Pelicci PG. Electron transfer between cytochrome c and p66Shc generates reactive oxygen species that trigger mitochondrial apoptosis. Cell 122: 221–233, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goel M, Sinkins WG, Zuo CD, Estacion M, Schilling WP. Identification and localization of TRPC channels in the rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F1241–F1252, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00376.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Graham S, Ding M, Sours-Brothers S, Yorio T, Ma JX, Ma R. Downregulation of TRPC6 protein expression by high glucose, a possible mechanism for the impaired Ca2+ signaling in glomerular mesangial cells in diabetes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F1381–F1390, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00185.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Graham S, Gorin Y, Abboud HE, Ding M, Lee DY, Shi H, Ding Y, Ma R. Abundance of TRPC6 protein in glomerular mesangial cells is decreased by ROS and PKC in diabetes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 301: C304–C315, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00014.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gritz ER, Dresler C, Sarna L. Smoking, the missing drug interaction in clinical trials: ignoring the obvious. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 14: 2287–2293, 2005. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haller M, Khalid S, Kremser L, Fresser F, Furlan T, Hermann M, Guenther J, Drasche A, Leitges M, Giorgio M, Baier G, Lindner H, Troppmair J. Novel Insights into the PKCβ-dependent Regulation of the Oxidoreductase p66Shc. J Biol Chem 291: 23557–23568, 2016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.752766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Higashijima Y, Hirano S, Nangaku M, Nureki O. Applications of the CRISPR-Cas9 system in kidney research. Kidney Int 92: 324–335, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hüttemann M, Pecina P, Rainbolt M, Sanderson TH, Kagan VE, Samavati L, Doan JW, Lee I. The multiple functions of cytochrome c and their regulation in life and death decisions of the mammalian cell: From respiration to apoptosis. Mitochondrion 11: 369–381, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ilatovskaya DV, Levchenko V, Lowing A, Shuyskiy LS, Palygin O, Staruschenko A. Podocyte injury in diabetic nephropathy: implications of angiotensin II-dependent activation of TRPC channels. Sci Rep 5: 17637, 2015. doi: 10.1038/srep17637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ilatovskaya DV, Staruschenko A. TRPC6 channel as an emerging determinant of the podocyte injury susceptibility in kidney diseases. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 309: F393–F397, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00186.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jaimes EA, Tian RX, Raij L. Nicotine: the link between cigarette smoking and the progression of renal injury? Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H76–H82, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00693.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khanday FA, Yamamori T, Mattagajasingh I, Zhang Z, Bugayenko A, Naqvi A, Santhanam L, Nabi N, Kasuno K, Day BW, Irani K. Rac1 leads to phosphorylation-dependent increase in stability of the p66shc adaptor protein: role in Rac1-induced oxidative stress. Mol Biol Cell 17: 122–129, 2006. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-06-0570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kong F, Ma L, Zou L, Meng K, Ji T, Zhang L, Zhang R, Jiao J. Alpha1-Adrenergic Receptor activation stimulates calcium entry and proliferation via TRPC6 channels in cultured human mesangial Cells. Cell Physiol Biochem 36: 1928–1938, 2015. doi: 10.1159/000430161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Konior A, Schramm A, Czesnikiewicz-Guzik M, Guzik TJ. NADPH oxidases in vascular pathology. Antioxid Redox Signal 20: 2794–2814, 2014. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kumar S, Kim YR, Vikram A, Naqvi A, Li Q, Kassan M, Kumar V, Bachschmid MM, Jacobs JS, Kumar A, Irani K. Sirtuin1-regulated lysine acetylation of p66Shc governs diabetes-induced vascular oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114: 1714–1719, 2017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1614112114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lai KM, Pawson T. The ShcA phosphotyrosine docking protein sensitizes cardiovascular signaling in the mouse embryo. Genes Dev 14: 1132–1145, 2000. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Le S, Connors TJ, Maroney AC. c-Jun N-terminal kinase specifically phosphorylates p66ShcA at serine 36 in response to ultraviolet irradiation. J Biol Chem 276: 48332–48336, 2001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106612200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li Q, Kim YR, Vikram A, Kumar S, Kassan M, Gabani M, Lee SK, Jacobs JS, Irani K. P66Shc-Induced MicroRNA-34a causes diabetic endothelial dysfunction by downregulating Sirtuin1. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 36: 2394–2403, 2016. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.308321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li W, Ding Y, Smedley C, Wang Y, Chaudhari S, Birnbaumer L, Ma R. Increased glomerular filtration rate and impaired contractile function of mesangial cells in TRPC6 knockout mice. Sci Rep 7: 4145, 2017. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-04067-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu S, Brown CW, Berlin KD, Dhar A, Guruswamy S, Brown D, Gardner GJ, Birrer MJ, Benbrook DM. Synthesis of flexible sulfur-containing heteroarotinoids that induce apoptosis and reactive oxygen species with discrimination between malignant and benign cells. J Med Chem 47: 999–1007, 2004. doi: 10.1021/jm030346v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu T, Hannafon B, Gill L, Kelly W, Benbrook D. Flex-Hets differentially induce apoptosis in cancer over normal cells by directly targeting mitochondria. Mol Cancer Ther 6: 1814–1822, 2007. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu T, Masamha CP, Chengedza S, Berlin KD, Lightfoot S, He F, Benbrook DM. Development of flexible-heteroarotinoids for kidney cancer. Mol Cancer Ther 8: 1227–1238, 2009. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Luzi L, Confalonieri S, Di Fiore PP, Pelicci PG. Evolution of Shc functions from nematode to human. Curr Opin Genet Dev 10: 668–674, 2000. doi: 10.1016/S0959-437X(00)00146-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ma R, Chaudhari S, Li W. Canonical transient receptor potential 6 channel: a new target of reactive oxygen species in renal physiology and pathology. Antioxid Redox Signal 25: 732–748, 2016. doi: 10.1089/ars.2016.6661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Magenta A, Greco S, Capogrossi MC, Gaetano C, Martelli F. Nitric oxide, oxidative stress, and p66Shc interplay in diabetic endothelial dysfunction. BioMed Res Int 2014: 193095, 2014. doi: 10.1155/2014/193095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Manohar S, Leung N. Cisplatin nephrotoxicity: a review of the literature. J Nephrol. doi: 10.1007/s40620-017-0392-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Margolis B, Skolnik EY. Activation of Ras by receptor tyrosine kinases. J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 1288–1299, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Menini S, Amadio L, Oddi G, Ricci C, Pesce C, Pugliese F, Giorgio M, Migliaccio E, Pelicci P, Iacobini C, Pugliese G. Deletion of p66Shc longevity gene protects against experimental diabetic glomerulopathy by preventing diabetes-induced oxidative stress. Diabetes 55: 1642–1650, 2006. [Erratum. Diabetes 67: 165, 2017. https://doi.org/10.2337/db18-er01a. 29066598] doi: 10.2337/db05-1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Menini S, Iacobini C, Ricci C, Oddi G, Pesce C, Pugliese F, Block K, Abboud HE, Giorgio M, Migliaccio E, Pelicci PG, Pugliese G. Ablation of the gene encoding p66Shc protects mice against AGE-induced glomerulopathy by preventing oxidant-dependent tissue injury and further AGE accumulation. Diabetologia 50: 1997–2007, 2007. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0728-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Migliaccio E, Giorgio M, Mele S, Pelicci G, Reboldi P, Pandolfi PP, Lanfrancone L, Pelicci PG. The p66shc adaptor protein controls oxidative stress response and life span in mammals. Nature 402: 309–313, 1999. doi: 10.1038/46311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Migliaccio E, Mele S, Salcini AE, Pelicci G, Lai KM, Superti-Furga G, Pawson T, Di Fiore PP, Lanfrancone L, Pelicci PG. Opposite effects of the p52shc/p46shc and p66shc splicing isoforms on the EGF receptor-MAP kinase-fos signalling pathway. EMBO J 16: 706–716, 1997. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.4.706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Miller B, Palygin O, Rufanova VA, Chong A, Lazar J, Jacob HJ, Mattson D, Roman RJ, Williams JM, Cowley AW Jr, Geurts AM, Staruschenko A, Imig JD, Sorokin A. p66Shc regulates renal vascular tone in hypertension-induced nephropathy. J Clin Invest 126: 2533–2546, 2016. doi: 10.1172/JCI75079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Montezano AC, Dulak-Lis M, Tsiropoulou S, Harvey A, Briones AM, Touyz RM. Oxidative stress and human hypertension: vascular mechanisms, biomarkers, and novel therapies. Can J Cardiol 31: 631–641, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Montezano AC, Touyz RM. Molecular mechanisms of hypertension—reactive oxygen species and antioxidants: a basic science update for the clinician. Can J Cardiol 28: 288–295, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2012.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nadasi E, Clark JS, Szanyi I, Varjas T, Ember I, Baliga R, Arany I. Epigenetic modifiers exacerbate oxidative stress in renal proximal tubule cells. Anticancer Res 29: 2295–2299, 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Napoli C, Martin-Padura I, de Nigris F, Giorgio M, Mansueto G, Somma P, Condorelli M, Sica G, De Rosa G, Pelicci P. Deletion of the p66Shc longevity gene reduces systemic and tissue oxidative stress, vascular cell apoptosis, and early atherogenesis in mice fed a high-fat diet. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 2112–2116, 2003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0336359100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Natalicchio A, Tortosa F, Perrini S, Laviola L, Giorgino F. p66Shc, a multifaceted protein linking Erk signalling, glucose metabolism, and oxidative stress. Arch Physiol Biochem 117: 116–124, 2011. doi: 10.3109/13813455.2011.562513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Kidney Disease Statistics for the United States. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-statistics/kidney-disease. [13 Aug 2017].

- 73.Orsini F, Migliaccio E, Moroni M, Contursi C, Raker VA, Piccini D, Martin-Padura I, Pelliccia G, Trinei M, Bono M, Puri C, Tacchetti C, Ferrini M, Mannucci R, Nicoletti I, Lanfrancone L, Giorgio M, Pelicci PG. The life span determinant p66Shc localizes to mitochondria where it associates with mitochondrial heat shock protein 70 and regulates trans-membrane potential. J Biol Chem 279: 25689–25695, 2004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401844200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Oshikawa J, Kim SJ, Furuta E, Caliceti C, Chen GF, McKinney RD, Kuhr F, Levitan I, Fukai T, Ushio-Fukai M. Novel role of p66Shc in ROS-dependent VEGF signaling and angiogenesis in endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 302: H724–H732, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00739.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pabla N, Dong Z. Cisplatin nephrotoxicity: mechanisms and renoprotective strategies. Kidney Int 73: 994–1007, 2008. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pagnin E, Fadini G, de Toni R, Tiengo A, Calò L, Avogaro A. Diabetes induces p66shc gene expression in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells: relationship to oxidative stress. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90: 1130–1136, 2005. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pelicci G, Dente L, De Giuseppe A, Verducci-Galletti B, Giuli S, Mele S, Vetriani C, Giorgio M, Pandolfi PP, Cesareni G, Pelicci PG. A family of Shc related proteins with conserved PTB, CH1 and SH2 regions. Oncogene 13: 633–641, 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pelicci G, Lanfrancone L, Grignani F, McGlade J, Cavallo F, Forni G, Nicoletti I, Grignani F, Pawson T, Pelicci PG. A novel transforming protein (SHC) with an SH2 domain is implicated in mitogenic signal transduction. Cell 70: 93–104, 1992. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90536-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pellegrini M, Baldari CT. Apoptosis and oxidative stress-related diseases: the p66Shc connection. Curr Mol Med 9: 392–398, 2009. doi: 10.2174/156652409787847254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Percy C, Pat B, Poronnik P, Gobe G. Role of oxidative stress in age-associated chronic kidney pathologies. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 12: 78–83, 2005. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Percy CJ, Brown L, Power DA, Johnson DW, Gobe GC. Obesity and hypertension have differing oxidant handling molecular pathways in age-related chronic kidney disease. Mech Ageing Dev 130: 129–138, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Percy CJ, Power D, Gobe GC. Renal ageing: changes in the cellular mechanism of energy metabolism and oxidant handling. Nephrology (Carlton) 13: 147–152, 2008. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2008.00924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Petros WP, Younis IR, Ford JN, Weed SA. Effects of tobacco smoking and nicotine on cancer treatment. Pharmacotherapy 32: 920–931, 2012. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-9114.2012.01117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Phillips A, Janssen U, Floege J. Progression of diabetic nephropathy. Insights from cell culture studies and animal models. Kidney Blood Press Res 22: 81–97, 1999. doi: 10.1159/000025912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Piantadosi CA, Suliman HB. Redox regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis. Free Radic Biol Med 53: 2043–2053, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pinton P, Rimessi A, Marchi S, Orsini F, Migliaccio E, Giorgio M, Contursi C, Minucci S, Mantovani F, Wieckowski MR, Del Sal G, Pelicci PG, Rizzuto R. Protein kinase C beta and prolyl isomerase 1 regulate mitochondrial effects of the life-span determinant p66Shc. Science 315: 659–663, 2007. doi: 10.1126/science.1135380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Porta C, Cosmai L, Gallieni M, Pedrazzoli P, Malberti F. Renal effects of targeted anticancer therapies. Nat Rev Nephrol 11: 354–370, 2015. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2015.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Purdom S, Chen QM. p66(Shc): at the crossroad of oxidative stress and the genetics of aging. Trends Mol Med 9: 206–210, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4914(03)00048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Qiu G, Ji Z. AngII-induced glomerular mesangial cell proliferation inhibited by losartan via changes in intracellular calcium ion concentration. Clin Exp Med 14: 169–176, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s10238-013-0232-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ramsey JJ, Tran D, Giorgio M, Griffey SM, Koehne A, Laing ST, Taylor SL, Kim K, Cortopassi GA, Lloyd KC, Hagopian K, Tomilov AA, Migliaccio E, Pelicci PG, McDonald RB. The influence of Shc proteins on life span in mice. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 69: 1177–1185, 2014. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ray PD, Huang BW, Tsuji Y. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) homeostasis and redox regulation in cellular signaling. Cell Signal 24: 981–990, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Reed DK, Arany I. p66shc and gender-specific dimorphism in acute renal injury. In Vivo 28: 205–208, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.San Martin A, Griendling KK. NADPH oxidases: progress and opportunities. Antioxid Redox Signal 20: 2692–2694, 2014. doi: 10.1089/ars.2014.5947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Soni H, Adebiyi A. TRPC6 channel activation promotes neonatal glomerular mesangial cell apoptosis via calcineurin/NFAT and FasL/Fas signaling pathways. Sci Rep 6: 29041, 2016. doi: 10.1038/srep29041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sonneveld R, van der Vlag J, Baltissen MP, Verkaart SA, Wetzels JF, Berden JH, Hoenderop JG, Nijenhuis T. Glucose specifically regulates TRPC6 expression in the podocyte in an AngII-dependent manner. Am J Pathol 184: 1715–1726, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sorokin A. Endothelin signaling and actions in the renal mesangium. Contrib Nephrol 172: 50–62, 2011. doi: 10.1159/000328680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sorokin A, Kohan DE. Physiology and pathology of endothelin-1 in renal mesangium. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 285: F579–F589, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00019.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Staruschenko A, Sorokin A. Role of βPix in the Kidney. Front Physiol 3: 154, 2012. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sun L, Xiao L, Nie J, Liu FY, Ling GH, Zhu XJ, Tang WB, Chen WC, Xia YC, Zhan M, Ma MM, Peng YM, Liu H, Liu YH, Kanwar YS. p66Shc mediates high-glucose and angiotensin II-induced oxidative stress renal tubular injury via mitochondrial-dependent apoptotic pathway. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 299: F1014–F1025, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00414.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tomilov AA, Bicocca V, Schoenfeld RA, Giorgio M, Migliaccio E, Ramsey JJ, Hagopian K, Pelicci PG, Cortopassi GA. Decreased superoxide production in macrophages of long-lived p66Shc knock-out mice. J Biol Chem 285: 1153–1165, 2010. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.017491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tomilov AA, Ramsey JJ, Hagopian K, Giorgio M, Kim KM, Lam A, Migliaccio E, Lloyd KC, Berniakovich I, Prolla TA, Pelicci P, Cortopassi GA. The Shc locus regulates insulin signaling and adiposity in mammals. Aging Cell 10: 55–65, 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00641.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Trinei M, Berniakovich I, Beltrami E, Migliaccio E, Fassina A, Pelicci P, Giorgio M. P66Shc signals to age. Aging (Albany NY) 1: 503–510, 2009. doi: 10.18632/aging.100057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, Sivertsson Å, Kampf C, Sjöstedt E, Asplund A, Olsson I, Edlund K, Lundberg E, Navani S, Szigyarto CA, Odeberg J, Djureinovic D, Takanen JO, Hober S, Alm T, Edqvist PH, Berling H, Tegel H, Mulder J, Rockberg J, Nilsson P, Schwenk JM, Hamsten M, von Feilitzen K, Forsberg M, Persson L, Johansson F, Zwahlen M, von Heijne G, Nielsen J, Pontén F. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 347: 1260419, 2015. doi: 10.1126/science.1260419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.van der Geer P, Pawson T. The PTB domain: a new protein module implicated in signal transduction. Trends Biochem Sci 20: 277–280, 1995. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(00)89043-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.van der Geer P, Wiley S, Gish GD, Pawson T. The Shc adaptor protein is highly phosphorylated at conserved, twin tyrosine residues (Y239/240) that mediate protein-protein interactions. Curr Biol 6: 1435–1444, 1996. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(96)00748-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.van der Geer P, Wiley S, Lai VK, Olivier JP, Gish GD, Stephens R, Kaplan D, Shoelson S, Pawson T. A conserved amino-terminal Shc domain binds to phosphotyrosine motifs in activated receptors and phosphopeptides. Curr Biol 5: 404–412, 1995. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(95)00081-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ventura A, Luzi L, Pacini S, Baldari CT, Pelicci PG. The p66Shc longevity gene is silenced through epigenetic modifications of an alternative promoter. J Biol Chem 277: 22370–22376, 2002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200280200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wang G, Chen Z, Zhang F, Jing H, Xu W, Ning S, Li Z, Liu K, Yao J, Tian X. Blockade of PKCβ protects against remote organ injury induced by intestinal ischemia and reperfusion via a p66shc-mediated mitochondrial apoptotic pathway. Apoptosis 19: 1342–1353, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s10495-014-1008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wang Y, Zhao J, Yang W, Bi Y, Chi J, Tian J, Li W. High-dose alcohol induces reactive oxygen species-mediated apoptosis via PKC-β/p66Shc in mouse primary cardiomyocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 456: 656–661, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wojtala A, Karkucinska-Wieckowska A, Sardao VA, Szczepanowska J, Kowalski P, Pronicki M, Duszynski J, Wieckowski MR. Modulation of mitochondrial dysfunction-related oxidative stress in fibroblasts of patients with Leigh syndrome by inhibition of prooxidative p66Shc pathway. Mitochondrion 37: 62–79, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2017.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wu RF, Liao C, Fu G, Hayenga HN, Yang K, Ma Z, Liu Z, Terada LS. p66Shc couples mechanical signals to RhoA through FAK-dependent recruitment of p115-RhoGEF and GEF-H1. Mol Cell Biol 36: 2824–2837, 2016. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00194-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Xu X, Zhu X, Ma M, Han Y, Hu C, Yuan S, Yang Y, Xiao L, Liu F, Kanwar YS, Sun L. p66Shc: a novel biomarker of tubular oxidative injury in patients with diabetic nephropathy. Sci Rep 6: 29302, 2016. doi: 10.1038/srep29302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Yang S, Zhao L, Han Y, Liu Y, Chen C, Zhan M, Xiong X, Zhu X, Xiao L, Hu C, Liu F, Zhou Z, Kanwar YS, Sun L. Probucol ameliorates renal injury in diabetic nephropathy by inhibiting the expression of the redox enzyme p66Shc. Redox Biol 13: 482–497, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Yang SK, Xiao L, Li J, Liu F, Sun L. Oxidative stress, a common molecular pathway for kidney disease: role of the redox enzyme p66Shc. Ren Fail 36: 313–320, 2014. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2013.846867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Yeh YT, Lee CI, Lim SH, Chen LJ, Wang WL, Chuang YJ, Chiu JJ. Convergence of physical and chemical signaling in the modulation of vascular smooth muscle cell cycle and proliferation by fibrillar collagen-regulated P66Shc. Biomaterials 33: 6728–6738, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Yuan Y, Wang H, Wu Y, Zhang B, Wang N, Mao H, Xing C. p53 contributes to cisplatin induced renal oxidative damage via regulating p66shc and MnSOD. Cell Physiol Biochem 37: 1240–1256, 2015. doi: 10.1159/000430247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Zhou S, Chen HZ, Wan YZ, Zhang QJ, Wei YS, Huang S, Liu JJ, Lu YB, Zhang ZQ, Yang RF, Zhang R, Cai H, Liu DP, Liang CC. Repression of P66Shc expression by SIRT1 contributes to the prevention of hyperglycemia-induced endothelial dysfunction. Circ Res 109: 639–648, 2011. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.243592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]