Abstract

Introduction

The Guide to Community Preventive Services recommends combined built environment approaches to increase physical activity, including new or enhanced transportation infrastructure (e.g., sidewalks) and land use and environmental design interventions (e.g., close proximity of local destinations). The aim of this brief report is to provide nationally representative estimates of two types of built environment supports for physical activity: near-home walkable infrastructure and destinations, from the 2015 National Health Interview Survey.

Methods

Adults (n=30,453) reported the near-home presence of walkable transportation infrastructure (roads, sidewalks, paths or trails where you can walk; and whether most streets have sidewalks) and four walkable destination types (shops, stores, or markets; bus or transit stops; movies, libraries, or churches; and places that help you relax, clear your mind, and reduce stress). The prevalence of each, and the count of destination types was calculated (in 2017) and stratified by demographic characteristics.

Results

Overall, 85.1% reported roads, sidewalks, paths, or trails on which to walk, and 62.6% reported sidewalks on most streets. Among destinations, 71.8% reported walkable places to relax; followed by shops (58.0%); transit stops (53.2%); and movies, libraries, or churches (47.5%). For most design elements, prevalence was similar among adults aged 18–24 and 25–34 years, but decreased with age >35 years. Adults in the South reported a lower prevalence of all elements compared with those in other Census regions.

Conclusions

Many U.S. adults report walkable built environment elements near their home; future efforts might target areas with many older adult residents or those living in the South.

INTRODUCTION

The Guide to Community Preventive Services (Community Guide) recently recommended combined built environment approaches to increase physical activity, including new or enhanced transportation infrastructure (e.g., sidewalks) and land use and environmental design interventions (e.g., close proximity of destinations).1 Public health surveillance of these built environment elements is needed to monitor progress and identify targets for intervention, but nationally representative estimates have been sparse. The purpose of this report is to describe the national prevalence of perceived near-home walkable infrastructure and destinations from the 2015 National Health Interview Survey.

METHODS

The National Health Interview Survey is an in-person survey of U.S. households designed to be representative of the civilian, non-institutionalized U.S. population. Perceived walking infrastructure and destinations were assessed in the 2015 Cancer Control Supplement.2 From each household, a randomly selected adult (aged ≥18 years) was read the following: The next questions are about where you live, and told to answer for themselves, not other people. Walkable infrastructure questions included: Where you live…are there roads, sidewalks, paths or trails where you can walk? and …do most streets have sidewalks? Using the same format, four near-home walkable destination types were reported: shops, stores, or markets; bus or transit stops; movies, libraries, or churches; and places that help you relax, clear your mind, and reduce stress. As an assessment of perceptions, interpretation was left to the respondents.

For each item, the proportion (with 95% CI) reporting yes was calculated, and the number of destination types was summed (range zero to four). Results were stratified by sex, age, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, and Census region (30,453 respondents had complete data). When associations were detected via adjusted Wald tests, pairwise differences were tested and corrected for multiple comparisons. Linear trends were tested across ordered groups. All trends and differences highlighted in the text were statistically significant (p<0.05). Analyses were conducted in 2017 using Stata, version 13.1 survey procedures.

RESULTS

Overall, 85.1% reported roads, sidewalks, paths or trails and 62.6% reported sidewalks on most streets (Table 1). Men reported higher prevalence than women of both. For sidewalks, those aged 18–24 and 25–34 years reported similar prevalence, beyond which prevalence was lower with older age. Prevalence of sidewalks was lowest among non-Hispanic whites (whites) and highest among non-Hispanic respondents of other races. The prevalence of roads, sidewalks, paths, or trails was higher with greater education beyond high school. The prevalence of sidewalks was also highest among college graduates, but not monotonically higher with greater education. Respondents in the South reported the lowest prevalence of both infrastructure elements.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics and Reported Prevalence of Walkable Infrastructure Among U.S. Adults, NHIS 2015

| Characteristic | Weighted sample | Roads, sidewalks, paths, or trailsa | Sidewalks on most streetsa |

|---|---|---|---|

| % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | |

| Overall | – | 85.1 (84.1, 85.9) | 62.6 (61.3, 63.9) |

| Sex | |||

| Women | 51.5 (50.7, 52.9) | 84.2 (83.2, 85.2) | 61.6 (60.1, 63.1) |

| Men | 48.5 (47.7, 49.3) | 85.9 (84.8, 87.0) | 63.6 (62.1, 65.1) |

| Age (years) | |||

| 18–24 | 12.6 (11.9, 13.3) | 87.5x (85.4, 89.5) | 72.6x (70.0, 75.1) |

| 25–34 | 17.5 (16.9, 18.1) | 87.4x (86.1, 88.6) | 71.3x (69.4, 73.1) |

| 35–44 | 16.5 (15.9, 17.1) | 87.2x (85.7, 88.5) | 66.5 (64.3, 68.5) |

| 45–64 | 34.3 (33.5, 35.1) | 83.5y (82.2, 84.8) | 57.5 (55.7, 59.3) |

| ≥65 | 19.1 (18.5, 19.8) | 82.2y (80.6, 83.7) | 53.8 (51.7, 56.0) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White, non-Hispanic | 65.6 (64.7, 66.5) | 83.7x (82.5, 84.8) | 54.7 (53.0, 56.3) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 12.0 (11.4, 12.6) | 85.1x,y (83.1, 86.9) | 72.9 (70.3, 75.4) |

| Hispanic | 15.8 (15.1, 16.5) | 87.2y (85.6, 88.6) | 79.6x (77.7, 81.4) |

| Other, non-Hispanic | 6.7 (6.3, 7.1) | 93.4 (92.0, 94.7) | 81.6x (78.0, 84.7) |

| Education | |||

| Less than high school | 12.6 (12.0, 13.2) | 80.3x (78.3, 82.1) | 61.9x (59.5, 64.3) |

| High school graduate | 24.8 (24.1, 25.5) | 81.4x (79.9, 82.9) | 57.8 (55.9, 59.6) |

| Some college | 31.2 (30.4, 32.0) | 84.9 (83.6, 86.1) | 61.3x (59.5, 63.2) |

| College graduate | 31.4 (30.5, 32.4) | 90.0 (89.0, 91.0) | 67.9 (66.1, 69.7) |

| Census regionb | |||

| Northeast | 17.5 (16.8, 18.3) | 87.1x (85.1, 88.9) | 63.4x (60.0, 66.8) |

| Midwest | 22.3 (21.4, 23.2) | 89.0x (87.4, 90.5) | 63.7x (60.9, 66.4) |

| South | 36.8 (35.7, 37.8) | 76.5 (74.4, 78.4) | 50.2 (48.0, 52.4) |

| West | 23.4 (22.6, 24.2) | 93.2 (92.1, 94.2) | 80.3 (78.2, 82.3) |

Notes: All sociodemographic subgroups are associated with roads, sidewalks, paths, or trails and sidewalks on most streets (Rao-Scott corrected χ2 p<0.05). Unweighted n=30,453 respondents with complete data.

Letters (x,y) indicate non-significant differences: within subgroups, values that share a letter are not significantly different (Bonferroni-corrected p≥0.05).

Northeast: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, and Vermont; Midwest: Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, and Wisconsin; South: Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Maryland, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Virginia, Tennessee, Texas, West Virginia, and District of Columbia; West: Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming.

NHIS, National Health Interview Survey

Places to help one relax were the most common destination type (71.8%), followed by shops (58.0%); transit stops (53.2%); and movies, libraries, or churches (47.5%; Table 2). Men reported higher prevalence than women of all destinations. Respondents aged 18–24 and 25–34 years reported similar prevalence of shops; transit stops; and movies, libraries, or churches; and each was progressively lower with increasing age ≥35 years. The youngest three age groups reported similar prevalence of places to relax. Whites reported the lowest prevalence of walkable shops; transit; and movies, libraries, or churches. Relaxing destinations were least common among those with a high school education or less; for other destination types, the least and most educated groups reported similar prevalence. Respondents in the South reported the lowest prevalence of all destinations.

Table 2.

Reported Prevalence of Four Walkable Destination Types Among U.S. Adults, NHIS 2015

| Characteristic | Shops, stores, or marketsa | Bus or transit stopsa | Movies, libraries, or churchesa | Relax, clear one’s mind, or relieve stressa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (95% CI) | % 95% CI | % 95% CI | % 95% CI | |

| Overall | 58.0 (56.8, 59.2) | 53.2 (51.9, 54.5) | 47.5 (46.3, 48.6) | 71.8 (70.8, 72.8) |

| Sex | ||||

| Women | 56.2 (54.9, 57.6) | 51.7 (50.2, 53.1) | 46.2 (44.8, 47.5) | 69.6 (68.4, 70.8) |

| Men | 59.9 (58.4, 61.4) | 54.8 (53.2, 56.4) | 48.8 (47.3, 50.3) | 74.1 (72.9, 75.3) |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18–24 | 71.5x (68.8, 74.1) | 62.7x (59.7, 65.6) | 58.9x (56.0, 61.7) | 75.8x (73.3, 78.2) |

| 25–34 | 67.8x (65.6, 69.9) | 62.1x (59.7, 64.5) | 55.8x (53.5, 58.1) | 76.4x (74.7, 78.1) |

| 35–44 | 60.5 (58.3, 62.6) | 56.0 (53.6, 58.3) | 49.6 (47.6, 51.7) | 74.7x (72.7, 76.6) |

| 45–64 | 54.3 (52.5, 56.0) | 49.6 (47.9, 51.3) | 44.8 (43.3, 46.3) | 71.3 (69.9, 72.7) |

| ≥65 | 44.7 (42.8, 46.6) | 42.8 (40.8, 44.7) | 35.2 (33.5, 36.9) | 63.3 (61.5, 65.0) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 51.4 (49.8, 52.9) | 44.2 (42.6, 45.9) | 43.3 (41.7, 44.8) | 71.8x (70.5, 73.1) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 68.6x (66.2, 70.9) | 68.1x (65.6, 70.4) | 56.9x (54.2, 59.4) | 66.8 (64.4, 69.1) |

| Hispanic | 74.1 (72.2, 76.0) | 73.1 (70.7, 75.5) | 56.4x (54.3, 58.5) | 74.4x (72.7, 76.1) |

| Other, non-Hispanic | 66.4x (63.4, 69.2) | 67.3x (64.3, 70.2) | 50.7 (47.6, 53.7) | 74.4x (71.5, 77.1) |

| Education | ||||

| Less than high school | 61.2x (58.8, 63.4) | 56.8x (54.5, 59.0) | 48.1x,y (45.8, 50.5) | 65.6x (63.6, 67.5) |

| High school graduate | 55.5y (53.6, 57.3) | 48.2 (46.4, 50.1) | 45.2y (43.4, 47.0) | 66.3x (64.5, 68.0) |

| Some college | 58.9x (57.2, 60.6) | 52.8 (50.9, 54.6) | 48.5x (46.7, 50.3) | 72.0 (70.3, 73.5) |

| College graduate | 57.8x,y (55.9, 59.7) | 56.1x (54.1, 58.0) | 47.9x,y (46.1, 49.8) | 78.5 (77.1, 79.8) |

| Census regionb | ||||

| Northeast | 59.6x (56.4, 62.7) | 59.1 (55.8, 62.2) | 51.7x (48.6, 54.8) | 71.5 (69.5, 73.5) |

| Midwest | 58.6x (56.1, 61.2) | 46.6 (43.7, 49.6) | 51.7x (49.2, 54.2) | 76.8 (74.8, 78.8) |

| South | 47.6 (45.5, 49.7) | 39.3 (37.1, 41.6) | 36.6 (34.6, 38.7) | 62.8 (60.8, 64.9) |

| West | 72.5 (70.8, 74.1) | 76.8 (74.9, 78.7) | 57.2 (55.3, 59.1) | 81.2 (79.8, 82.6) |

Notes: All sociodemographic subgroups are associated with all destinations (Rao-Scott corrected χ2 p<0.05). Unweighted n=30,453 respondents with complete data.

Letters (x,y) indicate non-significant differences: within subgroups, values that share a letter are not significantly different (Bonferroni-corrected p≥0.05)

Northeast: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, and Vermont; Midwest: Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, and Wisconsin; South: Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Maryland, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Virginia, Tennessee, Texas, West Virginia, and District of Columbia; West: Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming.

NHIS, National Health Interview Survey

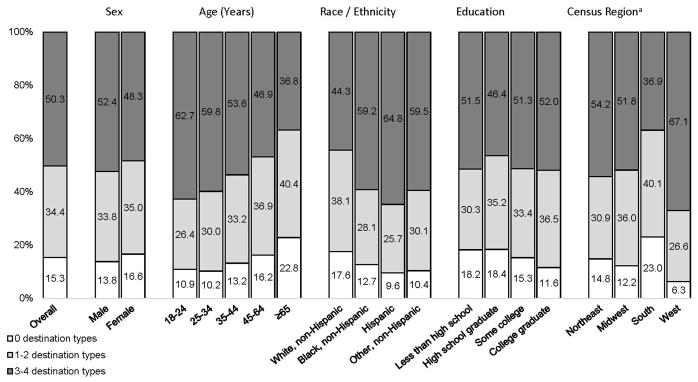

For destination counts, 15.3% reported none, 34.4% reported one to two, and 50.3% reported three to four (Figure 1). Men were less likely to report zero and more likely to report three to four destinations than women. Respondents aged 18–24 and 25–34 years reported similar numbers of walkable destinations. Among those aged ≥35 years, the proportion reporting zero destinations was higher with older age. Whites reported zero destinations more frequently than other racial/ethnic groups and Hispanics were the most likely to report three to four destinations. Adults with a college degree or higher reported zero destinations less frequently than other education groups. Respondents in the South reported zero or one to two destinations more frequently, and three to four destinations less frequently than respondents in other regions.

Figure 1.

Distribution of counts of reported walkable destination types among U.S. adults by selected demographic characteristics, NHIS 2015.

Notes: All covariates are associated with the count of destinations (adjusted Wald p<0.001).

aNortheast: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, and Vermont; Midwest: Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, and Wisconsin; South: Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Maryland, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Virginia, Tennessee, Texas, West Virginia, and District of Columbia; West: Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming.

NHIS, National Health Interview Survey

DISCUSSION

Many U.S. adults report living near walkable infrastructure and at least one walkable destination, but considerable differences exist by subgroup. Notably, the prevalence of most elements was lower with older age (more than 45 years), and lower in the South versus other regions. Areas with many older adult residents and those in the South may benefit from built environment approaches combining transportation system with land use and environmental design interventions, as recommended by the Community Guide.1

There are few comparable national-level data on perceived walkable built environment elements. The 2012 National Survey of Bicyclist and Pedestrian Attitudes and Behavior found 52% of respondents aged 16 years or older reported sidewalks along most or almost all neighborhood streets,3 compared with 62.6% in this analysis. In the 2012 ConsumerStyles survey, a nationwide telephone panel study of adult respondents, 26.4% reported transit stops (compared with 53.2% here) and 25.5% reported shops within a 10- to 15-minute walk from their home (compared with 58.0% here).4 These differences could be a result of differences in sampling, mode of administration, and question format or wording.5

Age was consistently inversely associated with prevalence of walkable built environment elements. One of several possible explanations is older adults walk shorter distances than younger adults,6 and might perceive fewer near-home amenities as walkable. Social support programs that encourage older adults to walk to nearby destinations might help expand their walking range. Additionally, designing communities with short distances and direct paths between residences and destinations can help encourage physical activity for all ages.1,6

Several factors may influence the lower prevalence of perceived walkable built environment elements in the South, including a larger rural population than the West or Northeast.7 Improving walkability may be particularly important in the South because of low physical activity levels and high chronic disease burden.8 Local- and state-level policy approaches, including Complete Streets, can encourage walkable built environment design elements across communities.9 Additionally, programs can promote awareness and use of new or existing walkable infrastructure.

Historically disadvantaged populations such as racial/ethnic minorities and those with low educational attainment have reported inequities in walkable built environment elements,10 but did not report uniformly low prevalence in this analysis. Future monitoring of the quality of these elements and the presence of barriers (e.g., crime) that could dissuade their use might provide a better understanding of environmental approaches to promote physical activity among historically disadvantaged populations.

Limitations

This report is subject to several limitations. First, perceptions may not match measures of the near-home environment and may be dependent on a person’s walking range, but such perceptions are important correlates of walking and bicycling.4,11 Second, only sidewalks were assessed separate from other infrastructure elements, which prevented analysis of the recommended combination of infrastructure and destinations.1 Third, urban and rural areas could not be examined separately because of confidentiality concerns, and should be a focus of future analyses. Finally, 9.0% of respondents had incomplete data. This is partially because of 5% dropping out before completing the cancer control supplement.

CONCLUSIONS

The prevalence of walkable built environment elements varies among U.S. adults. Older adults and those in the South report fewer infrastructure elements and destinations than their respective counterparts. These results may inform community efforts to increase physical activity through the promotion and implementation of built environment approaches, as recommended in the Community Guide.1

Acknowledgments

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

No external funding was used in this work, PJ receives general support from NIH (R00 CA201542).

Author roles were as follows: conception and design of study: GPW, SAC, DB, MAA, RB, PJ, JF; data analysis and interpretation: GPW, SAC, ENU, KBW, JEF; writing and revision of article: all; read and approve the final version: all.

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

References

- 1.Community Preventive Services Task Force. The Guide to Community Preventive Services website. Physical Activity: Built Environment Approaches Combining Transportation System Interventions with Land Use and Environmental Design; Atlanta, GA. May 4, 2017; www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/physical-activity-built-environment-approaches. [Google Scholar]

- 2.NIH. National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) Cancer Control Supplement (CCS) Bethesda, MD: 2017. https://healthcaredelivery.cancer.gov/nhis/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Department of Transportation National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Traffic tech: 2012 National survey on bicyclist and pedestrian attitudes and behavior. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paul P, Carlson SA, Fulton JE. Walking and the Perception of Neighborhood Attributes Among U.S. Adults, 2012. J Phys Act Health. 2017;14(1):36–44. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2015-0685. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2015-0685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.White E, Armstrong B, Saracci R. Principles of Exposure Measurement in Epidemiology: Collecting, Evaluating and Improving Measures of Disease Risk Factors. 2. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6.U.S. DHHS. Step it up! The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Promote Walking and Walkable Communities. Washington, DC: U.S. DHHS, Office of the Surgeon General; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.U.S. Census Bureau. Growth in Urban Population Outpaces Rest of Nation. Washington, DC: 2012. www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/2010_census/cb12-50.html. [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2015: With Special Feature on Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. U.S. DHHS; Hyattsville, MD: CDC; 2016. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus15.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smart Growth America. National Complete Streets Coalition website. Complete Streets Policy Adoption. 2016 https://smartgrowthamerica.org/app/uploads/2016/10/cs-policy-data-09022016.pdf.

- 10.Sallis JF, Slymen DJ, Conway TL, Frank LD, Saelens BE, Cain K, Chapman JE. Income disparities in perceived neighborhood built and social environment attributes. Health Place. 2011;17(6):1274–1283. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.02.006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kerr J, Emond JA, Badland H, et al. Perceived Neighborhood Environmental Attributes Associated with Walking and Cycling for Transport among Adult Residents of 17 Cities in 12 Countries: The IPEN Study. Environ Health Perspect. 2016;124(3):290–298. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1409466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]