Abstract

OBJECTIVES

The authors sought to evaluate the final 5-year safety and effectiveness of the platinum-chromium everolimus-eluting stent (PtCr-EES) in the randomized trial, as well as in 2 single-arm substudies that evaluated PtCr-EES in small vessels (diameter <2.5 mm; n = 94) and long lesions (24 to 34 mm; n = 102).

BACKGROUND

In the multicenter, randomized PLATINUM (PLATINUM Clinical Trial to Assess the PROMUS Element Stent System for Treatment of De Novo Coronary Artery Lesions), the PtCr-EES was noninferior to the cobalt-chromium everolimus-eluting stent (CoCr-EES) at 1 year in 1,530 patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention.

METHODS

Patients with 1 or 2 de novo coronary artery lesions (reference vessel diameter 2.50 to 4.25 mm, length ≤24 mm) were randomized 1:1 to PtCr-EES versus CoCr-EES. All patients in the substudies received PtCr-EES. The primary endpoint was target lesion failure (TLF), a composite of target vessel-related cardiac death, target vessel-related myocardial infarction, or ischemia-driven target lesion revascularization.

RESULTS

In the randomized trial, the 5-year TLF rate was 9.1% for PtCr-EES and 9.3% for CoCr-EES (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.97; p = 0.87). Landmark analysis demonstrated similar TLF rates from discharge to 1 year (HR: 1.12; p = 0.70) and from 1 to 5 years (HR: 0.90; p = 0.63). There were no significant differences in the rates of cardiac death, myocardial infarction, target lesion or vessel revascularization, or stent thrombosis. PtCr-EES had 5-year TLF rates of 7.0% in small vessels and 13.6% in long lesions.

CONCLUSIONS

PtCr-EES demonstrated comparable safety and effectiveness to CoCr-EES through 5 years of follow-up, with low rates of stent thrombosis and other adverse events. The 5-year event rates were also acceptable in patients with small vessels and long lesions treated with PtCr-EES. (The PLATINUM Clinical Trial to Assess the PROMUS Element Stent System for Treatment of De Novo Coronary Artery Lesions [PLATINUM]; NCT00823212; The PLATINUM Clinical Trial to Assess the PROMUS Element Stent System for Treatment of De Novo Coronary Artery Lesions in Small Vessels [PLATINUM SV]; NCT01498692; The PLATINUM Clinical Trial to Assess the PROMUS Element Stent System for Treatment of Long De Novo Coronary Artery Lesions [PLATINUM LL]; NCT01500434)

Keywords: coronary artery disease, drug-eluting stent(s), percutaneous coronary intervention, stent design

In multiple randomized trials, the cobalt chromium everolimus-eluting stent (CoCr-EES) (Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, California) resulted in lower rates of ischemia-driven revascularization (TLR), stent thrombosis (ST), and myocardial infarction (MI) when compared with first-generation drug-eluting stents (1–7). The platinum-chromium everolimus-eluting stent (PtCr-EES) (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, Massachusetts) uses the same polymer and everolimus concentration and elution rate as the CoCr-EES, but with a denser alloy and modified strut architecture designed to provide greater conformability, radial strength, radiopacity, and fracture resistance (8,9). In the large-scale, randomized PLATINUM (PLATINUM Clinical Trial to Assess the PROMUS Element Stent System for Treatment of De Novo Coronary Artery Lesions), the PtCr-EES was noninferior to CoCr-EES at 1 year with respect to the primary outcome of target lesion failure (TLF) (3.4% for PtCr-EES vs. 2.9% for CoCr-EES, pnoninferiority = 0.001) in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) (10). In 2 concurrent single-arm substudies, the PtCr-EES provided superior outcomes in small vessels (SV) and long lesions (LL) when compared with historical data from studies of platinum-chromium paclitaxel-eluting stents (11). It is important to describe the final long-term outcomes from these trials, because the favorable early safety and effectiveness profile of some coronary stents was not durable at late follow-up. The current report provides the final, 5-year follow-up results from the randomized PLATINUM trial and the single-arm SV and LL substudies.

METHODS

STUDY POPULATION

Patients were eligible for inclusion if they presented with unstable angina, stable angina, or documented silent ischemia, and required PCI of an atherosclerotic lesion with estimated stenosis of 50% to 99% and Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction flow grade >1. Patients with 1 or 2 lesions ≤24 mm in length and with reference vessel diameter (RVD) 2.50 to 4.25 mm, as visually assessed, were randomized in the main trial. Patients with a single lesion with RVD ≥2.25 to <2.50 mm and length ≤28 mm were enrolled in the SV study. Patients with a single lesion >24 to ≤34 mm long with RVD 2.5 to 4.25 mm were enrolled in the LL study. General exclusion criteria included acute or recent MI, recent PCI of the target vessel, left ventricular ejection fraction ≤30%, chronic total occlusions, left main or ostial lesions, major bifurcation disease, location of the target lesion in or access through a saphenous vein graft, and presence of thrombus. The studies were approved by the institutional review board at each participating center, and all subjects provided written informed consent.

INTERVENTION AND FOLLOW-UP

In the main trial, patients were randomized 1:1 in open-label fashion after successful target lesion pre-dilatation to PtCr-EES or CoCr-EES. Randomization was stratified by site. The operator was aware of the treatment assignment, but the patient and other providers were blinded. In the SV and LL substudies, all patients received PtCr-EES. Patients were treated with loading doses of aspirin and clopidogrel. The choice of anticoagulant agent (unfractionated heparin, enoxaparin, or bivalirudin) and use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors were left to operator discretion. After PCI, all patients were required to take aspirin indefinitely and clopidogrel for at least 6 months (12 months in the absence of high bleeding risk). Prasugrel was an option for patients outside of the United States. Follow-up was performed at 1, 6, 12, and 18 months, and then annually from 2 to 5 years. Routine angiographic follow-up was not performed. Study monitors verified all case report form data. An independent, blinded clinical events committee adjudicated all death, MI, TLR, target vessel revascularization (TVR), and ST events. An independent core laboratory evaluated all angiographic data. An independent Data Safety and Monitoring Committee oversaw the trial performance and outcomes.

ENDPOINTS

The primary endpoint in each of the studies was TLF at 1 year, a composite of cardiac death related to the target vessel, MI related to the target vessel, or ischemia-driven TLR. Cardiac death included any death without a proven noncardiac cause. MI was defined as: 1) new Q waves lasting >0.04 s in ≥2 leads with biomarkers elevated above normal (creatine kinase-myocardial band [CK-MB] or troponin); 2) elevated CK levels (>2× normal if spontaneous, >3× normal if after PCI, >5× normal if after coronary artery bypass grafting [CABG]), with elevated CK-MB; or 3) elevated troponin levels (>2× normal if spontaneous, >3× normal if after PCI, >5× normal if after CABG) with electrocardiographic changes consistent with ischemia (ST-segment or T-wave changes, new left bundle branch block), imaging evidence of new loss of viable myocardium, and/or a new regional wall motion abnormality. Ischemia-driven revascularization was defined as revascularization for angiographic stenosis ≥70%, or stenosis ≥50% with clinical or functional evidence of ischemia. Secondary endpoints included target vessel failure (TVF), a composite of target vessel-related cardiac death, target vessel-related MI, or TVR; the components of TLF and TVF; all-cause death; and ST (defined using the Academic Research Consortium criteria).

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

For the randomized trial, principal analyses were performed in the intention-to-treat population; however, patients who did not receive a study stent were not followed beyond 1 year. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to determine time-to-event rates, which were compared using the log-rank test. Landmark analyses were performed to examine event rates from 1 to 5 years (after excluding events occurring before 1 year). Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using Cox’s partial likelihood method. Multivariable analysis was performed to determine the independent predictors of TLF at 5 years in the entire population. Candidate patient- and lesion-level predictors (Online Table 1) were entered into the model using entry/exit criteria of p < 0.10. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software, version 8.2 or above (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). For all tests, a p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

RANDOMIZED TRIAL

The PLATINUM trial randomized 1,530 subjects at 132 sites in the United States, Europe, Japan, and other Asia-Pacific countries to PtCr-EES (n = 768) versus CoCr-EES (n = 762). As previously reported (10), the patients were well-matched with respect to baseline demographic, lesion, and procedure characteristics (Table 1). A total of 23 patients who did not receive a study stent were not followed beyond the first year. After the exclusion of these patients, 5-year outcomes data were available for 94.6% (717 of 758) of the PtCr-EES group and 93.5% (700 of 749) of the CoCr-EES group (Online Figure 1).

TABLE 1.

Baseline and Procedural Characteristics of Patients in the Randomized PLATINUM Trial and the SV and LL Substudies

| Randomized CoCr-EES (n = 762) |

Randomized PtCr-EES (n = 768) |

SV Study (n = 94) |

LL Study (n = 102) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Age, yrs | 63.1 ± 10.3 | 64.0 ± 10.3 | 64.33 ± 11.03 | 65.94 ± 9.79 |

| Male | 542 (71.1) | 550 (71.6) | 68 (72.3) | 64 (62.7) |

| Caucasian | 644 (84.5) | 650 (84.6) | 80 (85.1) | 83 (81.4) |

| Hypertension* | 558 (73.2) | 544/767 (70.9) | 75 (79.8) | 84 (82.4) |

| Hyperlipidemia* | 579/760 (76.2) | 598/765 (78.2) | 77 (81.9) | 84 (82.4) |

| Diabetes* | 191 (25.1) | 169 (22.0) | 40 (42.6) | 30/100 (30.0) |

| Smoking, ever | 448/741 (60.5) | 493/751 (65.6) | 59 (62.8) | 64/100 (64.0) |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 160/760 (21.1) | 160/761 (21.0) | 28 (29.8) | 34 (33.3) |

| Unstable angina | 188 (24.7) | 185/767 (24.1) | 23 (24.5) | 24/101 (23.8) |

|

| ||||

| Number of target lesions | ||||

| 1 | 684 (89.8) | 683 (88.9) | 94 (100) | 102 (100) |

| 2 | 77 (10.1) | 85 (11.1) | 0 | 0 |

|

| ||||

| Target lesion characteristics | ||||

| Reference vessel diameter, mm | 2.63 ± 0.49 | 2.67 ± 0.49 | 2.04 ± 0.26 | 2.56 ± 0.40 |

| Minimum lumen diameter, mm | 0.74 ± 0.34 | 0.75 ± 0.35 | 0.51 ± 0.21 | 0.73 ± 0.30 |

| Diameter stenosis, mm | 71.9 ± 11.5 | 71.8 ± 11.5 | 75.1 ± 9.5 | 71.7 ± 10.96 |

| Lesion length, mm | 12.5 ± 5.5 | 13.0 ± 5.7 | 14.15 ± 7.03 | 24.38 ± 8.21 |

|

| ||||

| Target vessel | ||||

| Left anterior descending | 343/813 (42.2) | 347/824 (42.1) | 32 (34.0) | 44 (43.1) |

| Left circumflex | 216/813 (26.6) | 217/824 (26.3) | 41 (43.6) | 22 (21.6) |

| Right | 254/813 (31.2) | 260/824 (31.6) | 21 (22.3) | 36 (35.3) |

|

| ||||

| Procedure characteristics | ||||

| No. of stents per patient | 1.20 ± 0.48 | 1.16 ± 0.44 | 1.00 ± 0.29 | 1.13 ± 0.36 |

| Total stent length per lesion, mm | 19.7 ± 8.9 | 20.5 ± 7.0 | 20.13 ± 7.38 | 37.51 ± 8.49 |

| Maximum dilation pressure, atm | 15.9 ± 3.2 | 16.3 ± 3.1 | 16.03 ± 3.39 | 17.50 ± 3.03 |

Values are mean ± SD, n (%), or n/N (%).

Requiring medication.

CoCr-EES = cobalt chromium everolimus-eluting stent(s); LL = long lesion; PLATINUM = PLATINUM Clinical Trial to Assess the PROMUS Element Stent System for Treatment of De Novo Coronary Artery Lesions; PtCr-EES = platinum-chromium everolimus-eluting stent(s); SV = small vessel.

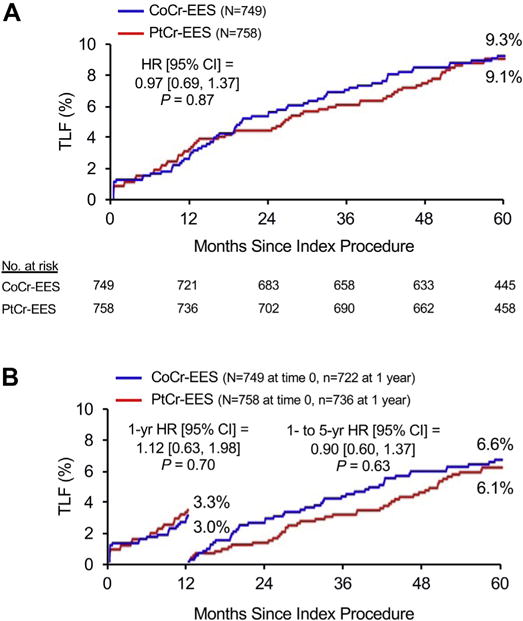

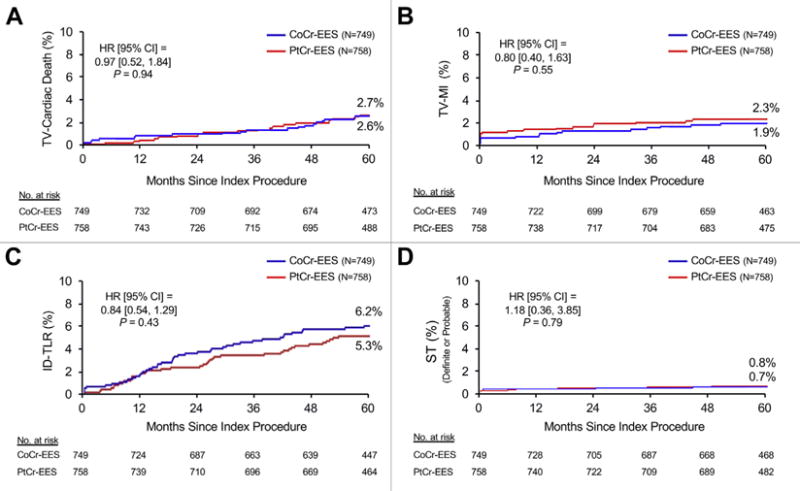

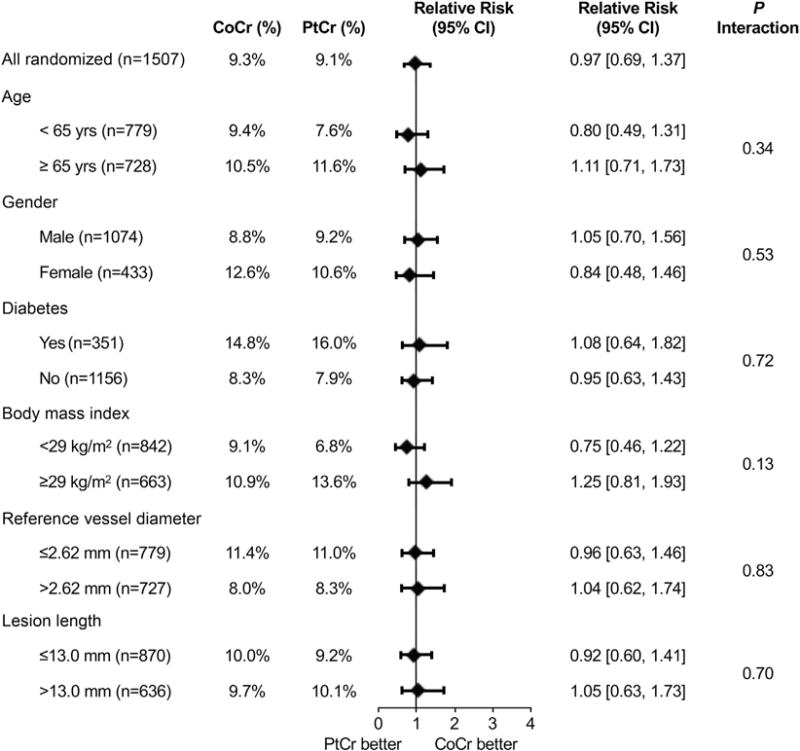

At 5 years, TLF occurred in 9.1% of patients assigned to PtCr-EES and 9.3% of patients assigned to CoCr-EES (HR: 0.97, 95% CI: 0.69 to 1.37; p = 0.87) (Figure 1A). Landmark analysis demonstrated similar relative TLF rates from discharge to 1 year (HR: 1.12; p = 0.70) and from 1 to 5 years (HR: 0.90; p = 0.63) (Figure 1B). The groups did not significantly differ in the rates of the components of the primary endpoint, or in any of the other pre-specified secondary endpoints (Table 2), both at 5 years (Figure 2) and in the landmark periods (Online Figure 2). ST at 5 years occurred in only 6 patients in the PtCr-EES group (0.8%) and in 5 patients in the CoCr-EES group (0.7%), with approximately one-half of these events occurring after 1 year in both groups. The use of antiplatelet agents was similar in both groups throughout followup (Online Figure 3A). Subgroup analysis did not demonstrate any statistically significant interactions between baseline factors and stent type with respect to the primary outcome of TLF at 5 years (Figure 3).

FIGURE 1. Primary Endpoint in the Randomized PLATINUM Trial.

The primary endpoint was target lesion failure (TLF), a composite of cardiac death related to the target vessel, MI related to the target vessel or ischemia-driven target lesion revascularization. (A) Five-year time-to-event curves. (B) Landmark analysis of event rates before and after 1 year of follow-up. CI = confidence interval; CoCr-EES = cobalt-chromium everolimus-eluting stent(s); HR = hazard ratio; MI = myocardial infarction; PLATINUM = PLATINUM Clinical Trial to Assess the PROMUS Element Stent System for Treatment of De Novo Coronary Artery Lesions; PtCr-EES = platinum-chromium everolimus-eluting stent(s).

TABLE 2.

5-Year Event Rates in the Randomized PLATINUM Trial

| PtCr-EES (n = 758) |

CoCr-EES (n = 749) |

Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target lesion failure | 9.1 (66) | 9.3 (66) | 0.97 (0.69–1.37) | 0.87 |

| Cardiac death | 2.6 (19) | 3.5 (25) | 0.74 (0.41–1.35) | 0.32 |

| Related to target vessel | 2.6 (19) | 2.7 (19) | 0.97 (0.52–1.84) | 0.94 |

| Not related to target vessel | 0.0 (0) | 0.8 (6) | – | 0.01 |

| Myocardial infarction | 3.4 (24) | 3.2 (23) | 1.02 (0.58–1.81) | 0.94 |

| Related to target vessel | 1.9 (14) | 2.3 (17) | 0.80 (0.40–1.63) | 0.55 |

| Not related to target vessel | 1.5 (10) | 1.2 (8) | 1.22 (0.48–3.10) | 0.67 |

|

| ||||

| Ischemia-driven TLR | 5.3 (38) | 6.2 (44) | 0.84 (0.54–1.29) | 0.43 |

|

| ||||

| All-cause death | 7.2 (52) | 7.8 (56) | 0.90 (0.62–1.32) | 0.60 |

|

| ||||

| All-cause death or MI | 10.3 (74) | 10.3 (74) | 0.98 (0.71–1.35) | 0.88 |

|

| ||||

| Ischemia-driven TVR | 9.9 (71) | 10.0 (70) | 0.98 (0.71–1.37) | 0.92 |

|

| ||||

| Ischemia-driven non-TL TVR | 5.8 (41) | 4.8 (33) | 1.21 (0.77–1.92) | 0.41 |

|

| ||||

| Target vessel failure | 13.1 (95) | 12.4 (88) | 1.05 (0.79–1.40) | 0.74 |

|

| ||||

| Stent thrombosis | ||||

| Definite | 0.8 (6) | 0.7 (5) | 1.18 (0.36–3.85) | 0.79 |

| Acute (<24 h) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Subacute (1–30 days) | 0 | 2 | ||

| Late (30 days to 1 yr) | 2 | 0 | ||

| Very late (>1 yr) | 3 | 2 | ||

| Probable | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | – | – |

| Possible | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | – | – |

Values are Kaplan-Meier estimated event rates expressed as % (n events) unless otherwise indicated.

CI = confidence interval; MI = myocardial infarction; PLATINUM = PLATINUM Clinical Trial to Assess the PROMUS Element Stent System for Treatment of De Novo Coronary Artery Lesions; TL = target lesion; TLR = target lesion revascularization; TVR = target vessel revascularization.

FIGURE 2. Major Secondary Endpoints at 5 Years in the Main PLATINUM Trial.

Five-year time-to-event curves for (A) target vessel (TV)-related cardiac death, (B) target vessel-related myocardial infarction (TV-MI), (C) ischemia-driven target lesion revascularization (ID-TLR), and (D) definite or probable stent thrombosis (ST). Abbreviations as in Figure 1.

FIGURE 3. Subgroup Analyses for the Primary Outcome at 5 Years in the Randomized PLATINUM Trial.

Interaction effects between stent type and baseline findings were determined for TLF at 5 years. Diamonds indicate relative risk, and bars indicate 95% CIs. Abbreviations as in Figure 1.

By multivariable analysis, the independent predictors of TLF at 5 years were previous CABG (p = 0.0008), history of congestive heart failure (p = 0.002), history of peripheral vascular disease (p = 0.002), diabetes mellitus (p = 0.005), and left anterior descending coronary artery treatment (p = 0.02). Randomized stent type was not a significant predictor of 5-year TLF (p = 0.77).

SV SUBSTUDY

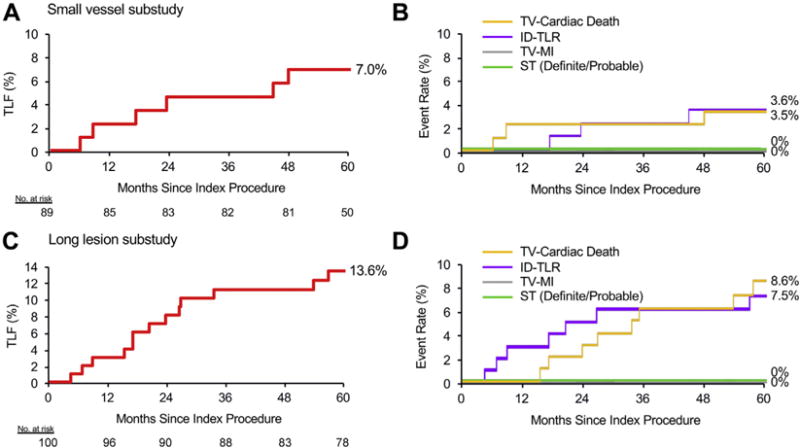

The SV substudy enrolled 94 patients at 23 sites in the United States, Europe, Japan, and New Zealand. The baseline patient, lesion, and procedure characteristics have been previously reported (11) and are summarized in Table 1. Five patients did not receive a study stent and were not followed beyond the first year. Five-year outcomes data were available for 93.3% (83 of 89) of the remaining patients. The 5-year TLF event rate was 7.0% (95% CI: 1.6% to 12.4%) (Figure 4A). The 5-year rates for the major secondary endpoints are shown in Figure 4B and Table 3. There were no definite or probable stent thromboses in this study cohort. At 5 years, the rates of aspirin and thienopyridine use were 92.1% and 39.5%, respectively (Online Figure 3B).

FIGURE 4. 5-Year Endpoints in the PLATINUM Substudies.

Five-year time-to-event curves for the primary and major secondary outcomes in the small vessel substudy (A and B) and long lesion substudy (C and D). Abbreviations as in Figures 1 and 2.

TABLE 3.

5-Year Event Rates in the PLATINUM Substudies

| SV Study (n = 89) |

LL Study (n = 100) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Target lesion failure | 7.0 (6) | 13.6 (13) |

| Cardiac death | 5.9 (5) | 8.6 (8) |

| Related to target vessel | 3.5 (3) | 8.6 (8) |

| Not related to target vessel | 2.5 (2) | 0.0 (0) |

| Myocardial infarction | 2.4 (2) | 1.3 (1) |

| Related to target vessel | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) |

| Not related to target vessel | 2.4 (2) | 1.3 (1) |

|

| ||

| Ischemia-driven TLR | 3.6 (3) | 7.5 (7) |

|

| ||

| All-cause death | 8.1 (7) | 10.6 (10) |

|

| ||

| All-cause death or MI | 9.3 (8) | 11.7 (11) |

|

| ||

| Ischemia-driven TVR | 13.1 (11) | 11.6 (11) |

|

| ||

| Ischemia-driven non-TL TVR | 12.0 (10) | 7.5 (7) |

|

| ||

| Target vessel failure | 16.3 (14) | 17.7 (17) |

|

| ||

| Stent thrombosis | ||

| Definite | 0 | 0 |

| Probable | 0 | 0 |

| Possible | 0 | 1.0 (1) |

LL SUBSTUDY

The LL substudy enrolled 102 patients at 30 sites in the United States, Europe, Japan, and New Zealand. The baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Two patients did not receive a study stent and were not followed beyond the first year. Five-year outcomes data were available for 88.0% (88 of 100) of the remaining patients. The 5-year TLF event rate was 13.6% (95% CI: 6.7% to 20.6%) (Figure 4C). The 5-year event rates for the major secondary endpoints are shown in Figure 4D and Table 3. There were no definite or probable stent thromboses in this study cohort. At 5 years, the rates of aspirin and thienopyridine use were 93.6% and 38.5%, respectively (Online Figure 3C).

DISCUSSION

The 5-year data from the pivotal, multicenter PLATINUM trial demonstrate that: 1) PtCr-EES have comparable short-term and long-term safety and effectiveness to CoCr-EES; 2) both stents resulted in very low rates of adverse events in the types of patients and lesions studied, with no significant differences in the 5-year rates of cardiac death, MI, or ST in the randomized trial; and 3) 5-year event rates were also low after PCI with PtCr-EES of selected long lesions or lesions in small vessels.

The present report provides the longest follow-up to date of patients undergoing PCI with PtCr-EES. The 5-year rates of ischemia-driven TLR with both stents were favorable (6.2% for CoCr-EES and 5.3% for PtCr-EES), signifying long-term freedom from repeat TLR in ~19 of 20 patients. Of note, the rates of ischemia-driven TVR not related to the target lesion were also similar between stent types (4.8% and 5.8%, respectively), signifying that approximately as many non-TLR events as TLR events in the target vessel occur during long-term follow-up. These findings are consistent with prior research (12) demonstrating an increasing proportion of non-TLR events during long-term follow-up after stent implantation due to progressive atherosclerosis in non-treated coronary segments.

In the SPIRIT III (Clinical Evaluation of the XIENCE V Everolimus Eluting Coronary Stent System in the Treatment of Patients With De Novo Native Coronary Artery Lesions) trial (2), which enrolled a similar patient population to the PLATINUM study, the 5-year rate of ischemia-driven TLR with CoCr-EES was 8.6%, whereas in the all-comers COMPARE (A Trial of Everolimus-eluting Stents and Paclitaxel-Eluting Stents for Coronary Revascularization in Daily Practice), the 5-year TLR rate with CoCr-EES was 5.0%.

The 5-year rates of all-cause death or MI with both stents in this trial were also favorable, and similar to that previously reported (10.3% for both CoCr-EES and PtCr-EES in the PLATINUM study, 9.5% for CoCr-EES in the SPIRIT III trial, 14.6% for CoCr-EES in the COMPARE trial). Of note, the 5-year ST rates in the randomized PLATINUM trial were particularly low (<1% with both devices), consistent with the low rate of ST with fluoropolymer-based everolimus-eluting stents reported in prior meta-analyses (13,14).

In patients treated with PtCr-EES in the single-arm SV and LL substudies, the 5-year event rates were also acceptable, with no patients developing ST. Although prior studies have evaluated CoCr-EES in SV and LL (defined using similar criteria), none has provided 5-year follow-up. The single-arm SPIRIT SV trial (Spirit Small Vessel Registry) (15), which evaluated CoCr-EES in SV, reported a 1-year TLF rate of 8.1%, numerically higher than both the 1-year (5.6%) and 5-year (7.0%) TLF rates with PtCr-EES in the PLATINUM SV substudy.

Likewise, the LONG-DES III (Percutaneous Treatment of Long Native Coronary Lesions With Drug-Eluting Stent-III) trial (16) reported a 1-year TLF rate of 12.9% after CoCr-EES in LL, higher than the 1-year (3.1%) and 2-year (8.8%) rates, but comparable to the 5-year rate (13.6%) with PtCr-EES in the PLATINUM LL substudy. In the IVUS-XPL (Impact of IntraVascular UltraSound Guidance on Outcomes of Xience Prime Stents in Long Lesions) trial (17), which examined the relative efficacy of angiography and IVUS for guiding the treatment of LL using CoCr-EES, the 1-year TLF rate in the angiography arm was 5.8%. Of note, the average lesion length was longer in both the IVUS-XPL (34.7 mm) and LONG-DES III (34.0 mm) trials than the PLATINUM LL trial (24.4 mm), which may account for the higher event rates. Direct comparisons between these studies should be performed with caution, given the modest numbers of enrolled patients, which adds imprecision to the event rate estimates, and the differences in patient and lesion risk profiles and adjudication methods. Nonetheless, the findings from the randomized trials and SV and LL substudies suggest that PtCr-EES and CoCr-EES likely have approximately comparable performance in these lesion subtypes. Large randomized trials would be required for more meaningful comparisons.

PtCr-EES and CoCr-EES share the same polymer, with a similar concentration and elution rate of everolimus (8,9); however, differences in the underlying metal alloy and its configuration give rise to differences in radial and longitudinal strength and resistance to deformation, flexibility and deliverability, and radiopacity. The procedural and angiographic success rates were similar with both devices in the randomized trial (10), and the similar long-term outcomes in the present report suggest overall interchangeability with respect to clinical performance with both devices in noncomplex lesions.

STUDY LIMITATIONS

The major limitation of the PLATINUM randomized trial is the exclusion of high-risk patients and lesions, restricting the generalizability of the results. Recent data from trials of PtCr-EES in less selected patients, however, are consistent with the present results. In the DUTCH PEERS (Durable Polymer-Based Stent Challenge of Promus Element Versus Resolute Integrity in an All Comers Population) trial (18,19), which randomized 1,811 all-comer patients to slow-release cobalt-chromium zotarolimus-eluting stents or PtCr-EES, the rate of TVF after PtCr-EES was 5.0% at 1 year and 10.3% at 3 years, whereas the rate of definite/probable ST was 1% at 1 year and 1.1% at 3 years, with no significant differences from zotarolimus-eluting stents. The results were consistent in high-risk patients presenting with MI. In the PLATINUM PLUS trial (Trial to Assess the Everolimus-Eluting Coronary Stent System (PROMUS Element) for Coronary Revascularization) (20), which randomized 2,980 all-comer patients to PtCr-EES versus CoCr-EES, the 1-year TVF rates were 4.6% versus 3.2% (p = 0.08), whereas the 1-year rates of definite/probable ST were 0.8% and 0.5% (p = 0.44), respectively. Similar results were seen in the single-arm PROMUS Element European Post-Approval Surveillance Study (21), which enrolled 1,010 all-comers and reported a 1-year TVF rate of 6.2% and ST rate of 0.6%. Long-term data from these trials are required to provide further evidence of the clinical performance of PtCr-EES in high-risk patients.

CONCLUSIONS

The 5-year results from the PLATINUM randomized trial demonstrate comparable long-term safety and effectiveness of PtCr-EES and CoCr-EES, with notably low rates of ST with both devices. Patients with SV and LL treated with PtCr-EES also had high rates of event-free survival at 5 years.

Supplementary Material

PERSPECTIVES.

WHAT IS KNOWN?

The PtCr-EES had been previously shown in the PLATINUM trial to be noninferior to the CoCr-EES at 1 year in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. However, longer-term outcomes have not been reported.

WHAT IS NEW?

The 5-year outcomes from the PLATINUM trial demonstrate comparable event rates for PtCr-EES and CoCr-EES throughout the study period, with low rates of stent thrombosis and other adverse cardiac events. Landmark analyses between 1 and 5 years did not show a difference in very late events between the stent types. Long-term event rates were also acceptable in registries evaluating small vessels and long lesions treated with PtCr-EES.

WHAT IS NEXT?

Long-term data on PtCr-EES from ongoing trials of unselected patients are required to provide further evidence of the safety and efficacy of PtCr-EES in general clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

Funded by Boston Scientific Corp. Dr. Teirstein has been a speaker for and received consulting fees from Boston Scientific, Abbott, and Medtronic. Dr. Meredith is an employee and shareholder of Boston Scientific. Dr. Dubois serves on Boston Scientific’s scientific advisory board. Dr. Feldman has received honoraria from Boston Scientific; is stockholder of Boston Scientific; and serves on their scientific advisory board. Dr. Dens is a consultant for and has received a research grant from Boston Scientific. Dr. Saito is a consultant for and has received honoraria from Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and Terumo. Drs. Allocco and Dawkins are employees and shareholders of Boston Scientific.

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- CABG

coronary artery bypass grafting

- CI

confidence interval

- CoCr-EES

cobalt chromium everolimus-eluting stent(s)

- HR

hazard ratio

- LL

long lesions

- MI

myocardial infarction

- PCI

percutaneous coronary intervention

- PtCr-EES

platinum-chromium everolimus-eluting stent(s)

- RVD

reference vessel diameter

- ST

stent thrombosis

- SV

small vessels

- TLF

target lesion failure

- TLR

target lesion revascularization

- TVF

target vessel failure

- TVR

target vessel revascularization

APPENDIX

For supplemental tables and figures, please see the online version of this paper.

Footnotes

All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

References

- 1.Stone GW, Midei M, Newman W, et al. Comparison of an everolimus-eluting stent and a paclitaxel-eluting stent in patients with coronary artery disease: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2008;299:1903–13. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.16.1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gada H, Kirtane AJ, Newman W, et al. 5-year results of a randomized comparison of XIENCE V everolimus-eluting and TAXUS paclitaxel-eluting stents: final results from the SPIRIT III trial (clinical evaluation of the XIENCE V everolimus eluting coronary stent system in the treatment of patients with de novo native coronary artery lesions) J Am Coll Cardiol Intv. 2013;6:1263–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jensen LO, Thayssen P, Hansen HS, et al. Randomized comparison of everolimus-eluting and sirolimus-eluting stents in patients treated with percutaneous coronary intervention: the Scandinavian Organization for Randomized Trials with Clinical Outcome IV (SORT OUT IV) Circulation. 2012;125:1246–55. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.063644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jensen LO, Thayssen P, Christiansen EH, et al. Safety and efficacy of everolimus- versus sirolimus-eluting stents: 5-year results from SORT OUT IV. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:751–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stone GW, Rizvi A, Newman W, et al. Everolimuseluting versus paclitaxel-eluting stents in coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1663–74. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0910496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kedhi E, Joesoef KS, McFadden E, et al. Second-generation everolimus-eluting and paclitaxel-eluting stents in real-life practice (COMPARE): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;375:201–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62127-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smits PC, Vlachojannis GJ, McFadden EP, et al. Final 5-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of everolimus- and paclitaxel-eluting stents for coronary revascularization in daily practice: the COMPARE trial (A Trial of Everolimus-Eluting Stents and Paclitaxel Stents for Coronary Revascularization in Daily Practice) J Am Coll Cardiol Intv. 2015;8:1157–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2015.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Brien BJ, Stinson JS, Larsen SR, Eppihimer MJ, Carroll WM. A platinum-chromium steel for cardiovascular stents. Biomaterials. 2010;31:3755–61. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Menown IB, Noad R, Garcia EJ, Meredith I. The platinum chromium element stent platform: from alloy, to design, to clinical practice. Adv Ther. 2010;27:129–41. doi: 10.1007/s12325-010-0022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stone GW, Teirstein PS, Meredith IT, et al. A prospective, randomized evaluation of a novel everolimus-eluting coronary stent: the PLATINUM (a Prospective, Randomized, Multicenter Trial to Assess an Everolimus-Eluting Coronary Stent System [PROMUS Element] for the Treatment of Up to Two de Novo Coronary Artery Lesions) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1700–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teirstein PS, Meredith IT, Feldman RL, et al. Two-year safety and effectiveness of the platinum chromium everolimus-eluting stent for the treatment of small vessels and longer lesions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;85:207–15. doi: 10.1002/ccd.25565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cutlip DE, Chhabra AG, Baim DS, et al. Beyond restenosis: five-year clinical outcomes from second-generation coronary stent trials. Circulation. 2004;110:1226–30. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000140721.27004.4B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palmerini T, Biondi-Zoccai G, Della Riva D, et al. Stent thrombosis with drug-eluting and bare-metal stents: evidence from a comprehensive network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;379:1393–402. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60324-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palmerini T, Kirtane AJ, Serruys PW, et al. Stent thrombosis with everolimus-eluting stents: meta-analysis of comparative randomized controlled trials. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:357–64. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.111.967083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cannon LA, Simon DI, Kereiakes D, et al. The XIENCE nano everolimus eluting coronary stent system for the treatment of small coronary arteries: the SPIRIT Small Vessel trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;80:546–53. doi: 10.1002/ccd.23397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park DW, Kim YH, Song HG, et al. Comparison of everolimus- and sirolimus-eluting stents in patients with long coronary artery lesions: a randomized LONG-DES-III (Percutaneous Treatment of LONG Native Coronary Lesions With Drug-Eluting Stent-III) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv. 2011;4:1096–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2011.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hong SJ, Kim BK, Shin DH, et al. Effect of intravascular ultrasound-guided vs. angiography-guided everolimus-eluting stent implantation: the IVUS-XPL randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314:2155–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.15454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.von Birgelen C, Sen H, Lam MK, et al. Third-generation zotarolimus-eluting and everolimus-eluting stents in all-comer patients requiring a percutaneous coronary intervention (DUTCH PEERS): a randomised, single-blind, multicentre, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2014;383:413–23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62037-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Der Heijden L, Von Birgelen C, Kok M, et al. Safety and efficacy of treating all-comers with novel zotarolimus- and everolimus-eluting coronary stents: three-year outcome of the randomised DUTCH PEERS trial (abstr) EuroPCR. 2016 Available at: https://www.pcronline.com/eurointervention/AbstractsEuroPCR2016_issue/abstracts-europcr-2016/Euro16A-OP0361/safety-and-efficacy-of-treating-all-comers-with-novel-zotarolimus-and-everolimus-eluting-coronary-stents-three-year-outcome-of-the-randomised-dutch-peers-trial.html. Accessed February 20, 2017.

- 20.Fajadet J, Neumann FJ, Hildick-Smith D, et al. Twelve-month results of a prospective, multi-centre trial to assess the everolimus-eluting coronary stent system (Promus Element): the PLATINUM PLUS all comers randomised trial. EuroIntervention. 2017;12:1595–604. doi: 10.4244/EIJV12I13A262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomas MR, Birkemeyer R, Schwimmbeck P, et al. One-year outcomes in 1,010 unselected patients treated with the PROMUS Element everolimus-eluting stent: the multicentre PROMUS Element European Post-Approval Surveillance Study. EuroIntervention. 2015;10:1267–71. doi: 10.4244/EIJY15M01_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.