Abstract

Males and females have different fitness optima but share vast majority of their genomes, causing an inherent genetic conflict between the two sexes that must be resolved to achieve maximal population fitness. We show that two tandem duplicate genes found specifically in Drosophila melanogaster are sexually antagonistic, but rapidly evolved sex-specific functions and expression patterns that mitigate their antagonistic effects. We use copy-specific knockouts and rescue experiments to show that Apollo is essential for male fertility but detrimental to female fertility, in addition to its important role in development, while Artemis is essential for female fertility but detrimental to male fertility. Further analyses show that Apl and Art have essential roles in spermatogenesis and oogenesis. These duplicates formed ~200,000 years ago, underwent a strong selective sweep and lost most expression in the antagonized sex. These data provide direct evidence that gene duplication allowed rapid mitigation of sexual conflict to evolve essential gametogenesis functions.

Males and females share the vast majority of their genomes but must satisfy different requirements for reproduction and survival. Differential sex-specific selection on traits with a shared genetic basis can move the two sexes away from their phenotypic optima1, causing intralocus sexual conflict (ISC) that reduces mean population fitness until the conflict is mitigated or resolved. Sexual conflict has been widely documented in metazoans, prompting the development and empirical tests of several mechanistic models of ISC resolution2–4. Gene duplication was recently proposed as a mechanism to resolve ISC because duplicate copies can separately optimize male- or female-beneficial functions without affecting the opposite sex5–7. Despite having no direct evidence that duplicate genes mediated or currently mediate ISC or its resolution, these models provide clear hypotheses about how ISC resolution occurs and how selection to resolve ISC may drive rapid functional divergence between new duplicate copies8–10. Much of the Drosophila melanogaster genome has been clearly demonstrated to be subject to sexual conflict, particularly genes involved in reproduction11–13, and thus provides a distinct opportunity to examine both the role of gene duplication in ISC resolution and the role of sexually antagonistic selection in the evolution of new gene functions. We report here that a pair of young duplicate genes found specifically in D. melanogaster rapidly evolved essential functions in spermatogenesis or oogenesis and that this was driven by selection to resolve ancestral ISC. Functional and expression pattern divergence between the duplicates largely mitigates their sexually antagonistic effects caused by their different cellular requirements in males and females. This case analysis provides a clear example of how a surprisingly short process is adequate for duplicates to evolve divergent, even essential, functions from initially indistinguishable gene copies, despite involving conflicting selective pressures.

Results

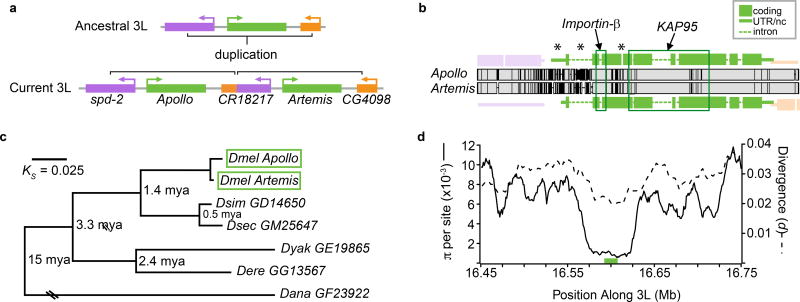

We investigated the evolution of a pair of D. melanogaster-specific tandem duplicate genes, CG32164 (Artemis) and CG32165 (Apollo). Apl and Art formed by duplication of a 7.7 kb region on chromosome arm 3L containing the Apl/Art ancestor and fragments of two nearby, unrelated genes CG4098 and spd-2 (Fig. 1). We identified a single copy of this region in 20 D. simulans and 20 D. yakuba individuals, but two copies in 97 African D. melanogaster individuals, demonstrating that the duplication occurred and fixed, i.e. spread to all D. melanogaster individuals, specifically in D. melanogaster after this species diverged from the D. simulans group ~1.4 million years ago (mya) (Fig. 1c; Methods)14. Divergence at synonymous sites in Apl and Art (Fig. 1c) suggests that the duplication occurred 208,000 years ago (95% confidence interval, CI95: 243,000 ya – 180,000 ya, based on ref. 15). Furthermore, previous work showed that the Apl/Art duplication underwent a strong selective sweep ~50,000 years ago16. We also found that the duplicates contain a significant deficiency of polymorphic sites relative to diverged sites according to the Hudson-Kreitman-Aguadé test (p = 4.6 × 10−4)17, 18, strongly supporting the conclusion that this region swept very recently (Fig. 1d). Finally, Apl has accumulated more synonymous (4) and non-synonymous substitutions (10) than Art (3 each), gained a novel intron, and accumulated unique deletions relative to Art and its orthologs in D. simulans and D. yakuba (Fig. 1b). Apl is therefore a derived copy while Art has a more conserved structure and sequence with its orthologs in other Drosophila species.

Fig. 1. Apollo and Artemis are Drosophila melanogaster-specific duplicate genes.

a) Apl and Art were formed by a tandem duplication on chromosome arm 3L. The duplication also generated a chimeric pseudogene, CR18217. b, Pairwise alignment of the tandem duplicate copies, with gene models. Vertical black lines are divergent sites. Regions of high divergence between Apl and Art (5’ UTR, intron 1, and a new Apl intron) and protein domains, annotated using BLASTp, are marked (*). c, Maximum likelihood phylogeny of the coding sequences of Apl, Art, and their single-copy orthologs in D. melanogaster subgroup species. Branch lengths are proportional to synonymous site divergence (KS), except GF23922 (Ks = 0.556) and mean speciation times are shown on internal nodes. See Obbard et al. (2012)14 for further details on speciation time estimates. Dmel: D. melanogaster; Dsim: D. simulans; Dsec: D. sechellia; Dyak: D. yakuba; Dere: D. erecta; Dana: D. ananassae. d, The Apl/Art duplication (green bar) is located in the middle of a large selective sweep, indicated by a deep trough of nucleotide diversity (π) relative to divergence to D. simulans and D. yakuba that extends ~25 kb beyond the duplicated regions. The trough is in the lowest 0.5% of genome-wide Hudson-Kreitman-Aguadé-like test statistics in this dataset (Methods)17, 18.

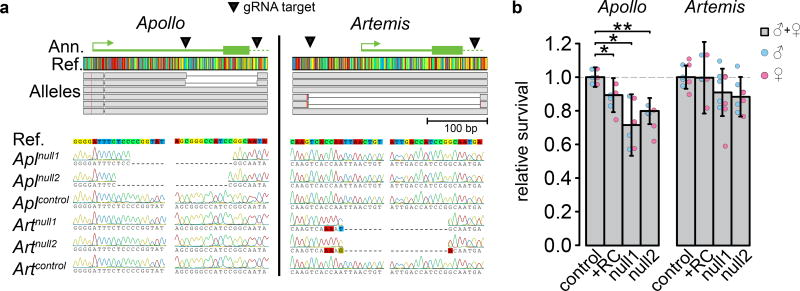

We first tested the viability effects of each duplicate using constitutive RNAi. We found that specifically silencing Apl caused a mean 33% reduction in survival to adulthood relative to controls (Welch’s t5.7 = 4.80, p = 0.003), while silencing Art had no detectable effect on survival (mean +5.0%, t5.9 = −0.760, p = 0.476; Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). Thus, our initial results suggested that Apl had rapidly evolved a strong be neficial effect(s). To further explore this hypothesis and better understand how these species-specific duplicates evolved diverged functions, we generated copy-specific knockouts of Apl and Art using CRISPR/Cas9 (Fig. 2a; Supplementary Table 1). First, two unique CRISPR/Cas9 mutants of each gene recapitulated our RNAi results (Fig. 2b). An average of 29% and 20% fewer Aplnull homozygotes survive to adulthood than expected (Aplnull1 t3.4 = 4.68, p = 0.014; Aplnull2 t3.5 = 7.61, p = 0.003), but survival of Artnull flies is not significantly reduced (Artnull1 t3.4 = 1.65, p = 0.158 and Artnull2 t3.0 = 2.65, p = 0.051; Supplementary Tables 4 and 5). Apl and Art knockouts did not have significantly different effects on male and female survival (Fig. 2b). Furthermore, we rescued 62% (CI95: 30.4% – 95.6%) of the Aplnull1 lethal effect by inserting a wild-type Apl copy under the control of its native promoter into chromosome 2 (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 2). Thus, Apl, more so than Art, plays an important role in fly development.

Fig. 2. Apollo and Artemis CRISPR/Cas9 knockouts and their viability effects.

a, Apl and Art CRISPR/Cas9 alleles aligned to the reference gene sequence and structure. Bottom: Sequencing traces of the same alleles near the breakpoints. Control lines were isolated in the same way as null lines, but contain no deletions in either gene. b, Egg-to-adult survival of homozygous Apl or Art mutant flies relative to control lines. Bars show the mean survival of all flies (males and females). Error bars indicate 95% CIs. Overlaid points indicate relative survival of males or females specifically for each replicate cross. We rescued Aplnull1 (Artnull1) effects by inserting a wild-type copy of Apl (Art) under the control of its native promoter into chromosome 2 (+RC lines; Supplementary Fig. 2). Welch’s t-tests between pooled data sets *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Full results and statistical analyses are shown in Supplementary Tables 4 and 5.

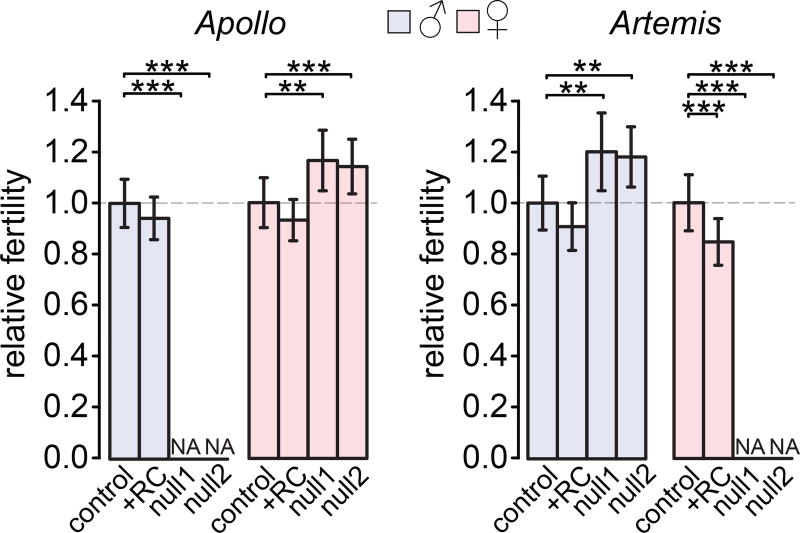

Most Aplnull and Artnull flies survive to adulthood but we could not generate true-breeding mutant stocks for either gene, suggesting that the fertility of Aplnull and Artnull flies was affected. We next tested whether Apl or Art knockout affected male or female reproduction by crossing individual flies to a wild-type stock, Oregon-R (Fig. 3, Supplementary Tables 6 and 7). We observed that, surprisingly, all Aplnull males are sterile, but Aplnull females produced an average of 18.0% or 20.0% more offspring than controls. In stark contrast, all Artnull females are sterile, but Artnull males sire 14.1% or 16.5% more offspring than controls. Aplnull1 and Artnull1 fly fertility was rescued by insertion into chromosome 2 of wild type Apl and Art, respectively, under the control of their native promoters (Fig. 3; Supplementary Fig. 2), suggesting the fertility defects are specifically caused by the mutations in these genes. These results clearly show that both Apl and Art have complementary sexually antagonistic fitness effects: normal Art function benefits females but harms males, while normal Apl function benefits males but harms females.

Fig. 3. Apollo and Artemis have sex-specific essential functions and are both sexually antagonistic.

Relative numbers of offspring produced by individual males or females homozygous for the indicated Apl allele (left) or Art allele (right). Raw counts are scaled to the mean counts from control lines for the appropriate gene and sex. We show means and 95% CIs from ≥30 crosses per bar. NA: no fertile flies. We rescued Aplnull1 (Artnull1) effects by inserting a wild-type copy of Apl (Art) under the control of its native promoter into chromosome 2 (+RC lines; Supplementary Fig. 2). Welch’s t-test *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Extended statistics are provided in Supplementary Tables 4–7.

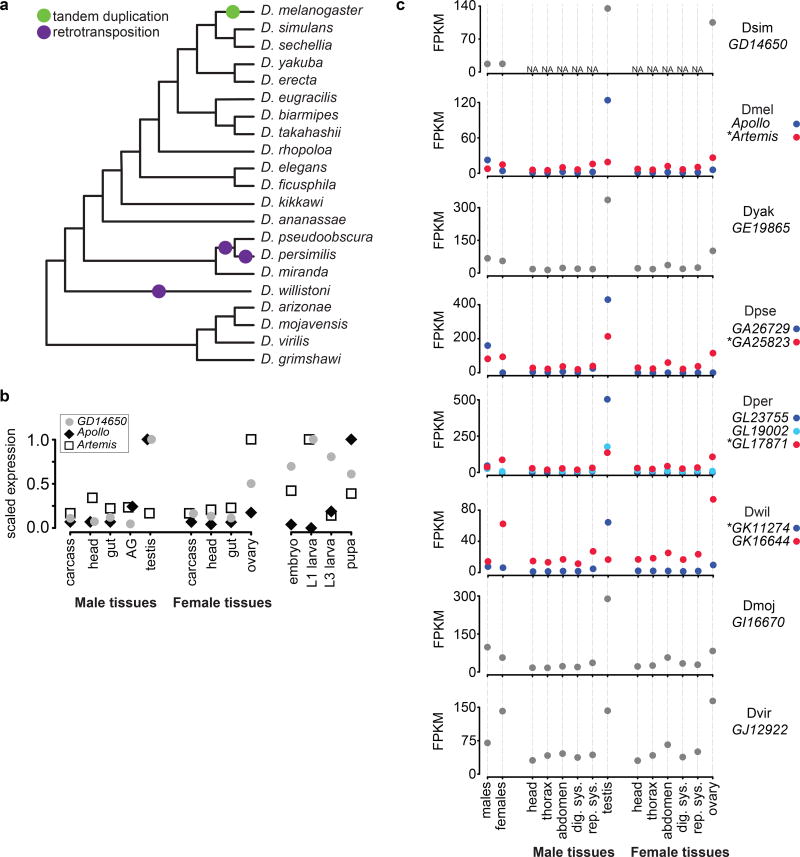

These fitness effects are consistent with Apl and Art expression patterns: Apl exhibits strong testis-biased expression, while Art exhibits strong ovary-based expression (Fig. 4). In comparison, single-copy Apl/Art orthologs in D. melanogaster’s closest relatives, including D. simulans GD14650 (Fig. 4b, c), have high expression in both ovary and testis. This suggests that Apl retained high testis expression and lost most ovary expression while Art retained ovary expression but lost most testis expression. Surprisingly, we found that the single copy Apl/Art ancestor underwent at least four independent duplications in different Drosophila lineages (Fig. 4a; Supplementary Fig. 3). In each case one duplicate copy retains high testis expression but loses most ovary expression while the other copy retains female-biased expression but loses most testis expression (Fig. 4c). These results invite speculation that the Apl/Art story has played out multiple times in fruit fly evolution, but we cannot fully support this hypothesis without phenotypic data in these other species.

Fig. 4. Expression pattern evolution of Apl, Art, and their homologs across Drosophila.

a, Drosophila species cladogram57 with duplications of the Apl/Art ancestor marked (see also Supplementary Fig. 3). b, Quantitative reverse-transcriptase PCR estimation of D. simulans GD14650, Apl, and Art expression levels across tissues and development. We measured expression relative to RpL32 using the ΔCT method (Supplementary Table 1, Methods). ΔCT values for a gene are scaled to the maximum value for that gene. Each point represents three biological replicates; all SEMs were less than 0.13 (not shown). AG: accessory gland; L1: first instar larva; L3: third instar larva. c, RNA-sequencing based expression levels of Apl, Art, and their orthologs (GEO Accessions GSE31302 a nd GSE99574). D. ananassae GF23922 has a nearly identical expression to D. yakuba GE19865 and is omitted. Species and gene names are shown to the right of their respective plots. Ancestral copies (*) were determined based on gene structure similarity to other single-copy orthologs. “Males” and “females” are whole body measurements except in D. simulans, which is carcass. FPKM: fragments mapped per kilobase of transcript per million fragments; rep. sys.: reproductive system except gonads; dig. sys.: digestive system; NA: no data available.

Altogether, CRISPR/Cas9-induced knockouts show that Apl and Art, species-specific tandem duplicate genes, are both essential for fly reproduction and that both genes are sexually antagonistic. While the duplicate copies have evolved essential functions specifically in male or female reproduction, each copy also significantly suppresses the fertility of the opposite sex. The complementary sexually antagonistic effects of Apl and Art suggest that the significant fitness cost of evolving their essential reproductive functions has been effectively mitigated by their evolution of divergent expression patterns in ovary and testis.

To better understand the similarities and differences between their molecular functions, we next investigated the effects of Apl and Art knockouts on gametogenesis. The functions of Apl and Art in D. melanogaster are unknown, but their protein sequences contain an importin-β N-terminal domain and HEAT repeats characteristic of importin-β proteins (Fig. 1b; Supplementary Fig. 4), a class of proteins involved in a wide range of cellular processes including import of cargo molecules into the nucleus, mitotic spindle assembly, and nuclear envelope assembly19–21. We next detected and compared the cellular biological effects of Apl and Art knockouts on spermatogenesis and oogenesis.

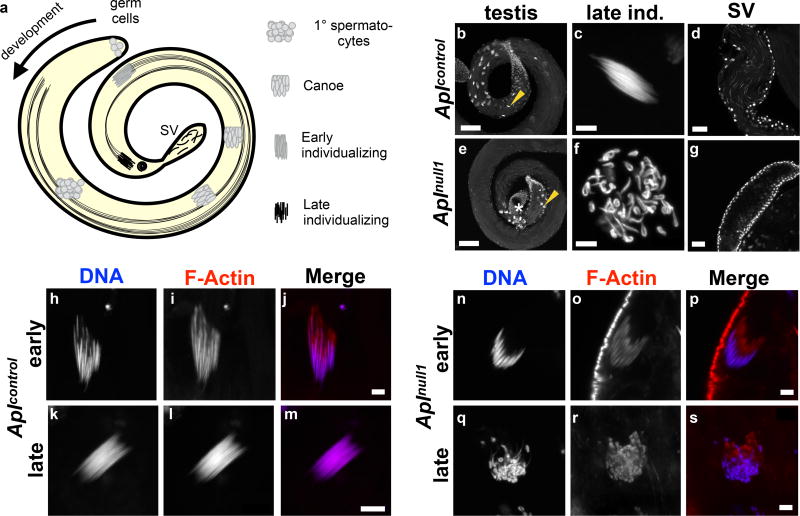

We first investigated spermatogenesis in Aplnull males (Fig. 5; Supplementary Fig. 5). During normal Drosophila spermatogenesis, a single germ cell gives rise to a cyst of 64 interconnected spermatids that proceed through development together until individualization, when spermatids are invested in their own membranes to produce independent, mature sperm. Using phalloidin and DAPI staining, we found that the majority of this process appears normal in Aplnull males, but mutants produce no mature sperm because the actin/myosin structures that drive individualization never dissociate from spermatid nuclei (Fig. 5; Supplementary Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Apl knockout prevents spermatid individualization.

a, Schematic of spermatogenesis in a D. melanogaster testis. A single germ cell produces a cyst of 64 spermatids after a mitotic and two meiotic divisions. Flagella are shown for individualizing cysts, but exist for canoe-stage cysts. Individualization occurs when an actomyosin complex (individualization cone) travels from the nuclei to the ends of the microtubule tails, investing each spermatid in its own membrane. b–g, DAPI nuclear stains of testis or seminal vesicles (SV) from 0 – 3 day old males. b, Spermatogenesis in rescue males is normal. Development proceeds counterclockwise from the bottom right corner. c, A late individualizing cyst, similar to that marked by an arrow in b. d, Seminal vesicle containing mature sperm. Large somatic nuclei delineate the vesicle. e–g, Same features as b–d, but in Aplnull1 mutants. e, Spermatogenesis proceeds counterclockwise from the top edge. *: seminal vesicle. f, An example of the most mature cysts, similar to that marked by an arrow in e. g, Seminal vesicle lacking mature sperm. Scale: b,e: 50 µm, c,f 5 µm, d,g 25 µm. h–s, Phalloidin and DAPI staining of individual cysts. Spermatogenesis proceeds downward in each image; the individualization cone is located above nuclei. Scale: 5 µm. j,p, Early individualizing cysts. m,s, Late individualizing cysts. While the individualization cone has departed wild-type cyst nuclei (m), it remains associated with cysts in Aplnull1 mutants (s).

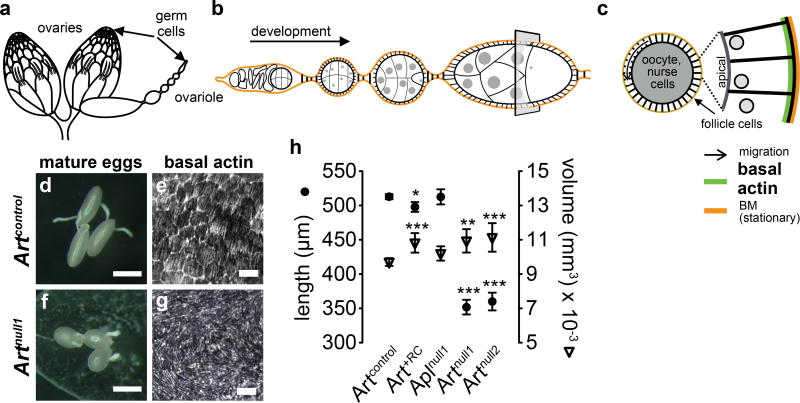

Conversely, we found that Artnull females produce round eggs with larger volumes than wild-type females and this appears to be due to disruption of actin networks that normally help restrict egg girth (Fig. 6, Supplementary Fig. 6)22. Furthermore, we never observed sperm in eggs produced by mated Artnull females using anti-tubulin stains (n = 53), suggesting that sperm may have difficulty entering the thickened micropyles of round eggs. The overall effect of Art knockout is female sterility.

Fig. 6. Art knockouts disrupt actin networks required for egg elongation.

a, A pair of D. melanogaster ovaries, which are comprised of ovarioles and, b, developing egg chambers. c, Cross section of an egg chamber. BM: basement membrane. d,e, Follicle cell migration produces ordered basal actin structures that restrict egg girth during development to produce elongate mature eggs. f,g, Artnull females produce round eggs due to disruption of basal actin structures. We found no defects in border cell migration, ring canal formation, or nurse cell dumping that might otherwise explain the shape defect (Supplementary Fig. 6). Scale: d,f: 300 µm; e,g: 10 µm. h, Means and 95% CIs of egg lengths and volumes. Welch’s t-test *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, ***p <0.001 compared to wild-type Artcontrol. Full statistical test results are shown in Supplementary Table 9.

Altogether, Apl and Art knockouts show that both copies of this species-specific duplicate gene pair are essential for fly fertility through their effects on actin structures required for normal gametogenesis: the actomyosin individualization cones required for the terminal stage of spermatogenesis and the actin networks required throughout oogenesis. The detrimental effects of Apl and Art on females and males, respectively, are likely caused by their shared influence on these actin structures. These effects appear to have been largely mitigated through the evolution of testis- or ovary-biased expression of Apl and Art (Fig. 4), but the fact that the two copies have little protein sequence divergence between them (2% of their 1,080 amino acids), no obvious divergence in conserved domains (Fig. 1b; Supplementary Fig. 4), and residual expression in the harmed sex suggests a clear mechanism for the remaining sex antagonism.

Finally, we expected that any signatures of recent selection on Apl and/or Art would be obvious in the duplicate gene sequences or the regions flanking them because the duplication occurred so recently. Maximum likelihood estimates suggest that the single-copy Apl/Art ancestor was under strong purifying selection before duplication ~200,000 ya: the gene accumulated 0.071 substitutions per synonymous site (dS) but 0.016 substitutions per nonsynonymous site (dN/dS = 0.23, CI95: 0.19 to 0.42) between the D. melanogaster - D. simulans speciation event and the duplication event (Supplementary Table 8)23.

Discussion

Our data suggest a model in which the Apl/Art duplication was favored because it allowed the resolution of ISC that was present in the single-copy ancestral gene. 1) The single-copy ancestor was likely expressed in the gonads of both sexes and influenced the assembly or action of actin structures in both oogenesis and spermatogenesis (Figs. 4 – 6). Such a pleiotropic gene could not be optimized for its male and female effects simultaneously and was therefore subject to ISC5, 6, 24. 2) The ancestral gene was duplicated to produce two identical gene copies, both initially subject to ISC, Apl and Art. However duplication allowed Apl and Art to separately accumulate mutations that distinguished their expression patterns and protein sequences (Figs. 1 and 4)3, 5, 6. 3) Strong selection to resolve ISC (Fig. 1d) resulted in male-biased Apl and female-biased Art expression patterns that mitigate their antagonistic effects and allow optimization of their sex-specific essential functions through protein sequence changes (Figs. 1, 4 – 6). While Apl/Art ISC has been largely mitigated through expression pattern and sequence divergence between the two copies, both genes do still detrimentally affect one sex (Fig. 3, Supplementary Tables 6 and 7). The conflict may not be fully resolved because the appearance and subsequent resolution of SC in the two copies may occur until enough divergence in expression patterns and sequences has accumulated to provide them with non-overlapping molecular functions and expression patterns. These considerations form a process of co-evolution between the duplicate copies that echoes the co-evolution model in sexually antagonistic phenotypes and the selection-pleiotropy-compensation model of developmental evolution25, 26. Furthermore, tight linkage between the two duplicates has probably slowed the resolution process considerably because it prevents the independent evolution of Apl and Art. Even so, our data show that mitigation of ISC through the evolution of sexually dimorphic expression and sequence changes occurred rapidly, within ~200,000 years, much shorter than the evolutionary time scale predicted by many duplicate gene evolution models1, 6, 7, 10.

Apl and Art knockouts led to an average 19% and 15% increase in female and male reproduction, respectively, suggesting that extremely strong sexually antagonistic selection remains active on the two gene copies (Fig. 3). However, the strength of these effects may be influenced by other factors, including life history tradeoffs and laboratory conditions. For example, there are well-established negative correlations between egg production and female longevity27, and the unnatural setting of laboratory experiments, supported by ample food, adequate moisture, constant temperature, and consistent day length may considerably mask trade-offs and amplify the fitness effects of gene knockouts on the whole28. Thus, while there were significant differences between control and knockout experiments that were treated identically and these results strongly support the presence of residual sexually antagonistic selection, the actual fitness effects of the knockout lines may be lower than those we observed.

In conclusion, our analyses of Apl and Art provide strong support for theoretical models5–7 that predict gene duplication plays an important role in resolving ISC by allowing partitioning of sex-specific expression patterns and functions into different duplicate copies. Furthermore, our data clearly show that species-specific duplicate genes can serve essential roles in gametogenesis. Without phenotypic data we cannot know if the duplicate gene pairs in D. pseudoobscura, D. persimilis, and D. willistoni have evolved their functions similarly to Apl and Art, but the fact that each pair’s expression pattern divergence mirrors the D. melanogaster case provides tantalizing hints that the Apl/Art orthologs might have been repeatedly involved in ISC resolution (Fig. 4). Studies of these convergent duplication events will be important for understanding the generality of duplication based ISC resolution as well as for comparing how the duplication mechanism (i.e. DNA- vs. RNA-based) influences the duplicates in evolution. Finally, it is possible that ISC may appear de novo soon after gene duplication, ignited by initial neofunctionalization of male-beneficial functions in one copy, and subsequently be mitigated or resolved by divergence between duplicates. Such strong male-specific selection supports the many observations that genes with male-biased or male-specific expression originate more rapidly than genes with female- or unbiased expression10, 29, 30.

Methods

Identification of the D. melanogaster-specific Apl/Art duplication

CG32165 (Apl) was identified as a D. melanogaster-specific gene in previous studies of new gene evolution in Drosophila31–33. We determined the precise coordinates of the duplicate copies to be 3L:16,593,391–16,601,090 and 3L:16,601,091–16,608,783 in the release 6 D. melanogaster reference genome assembly using syntenic alignments available from the UCSC Genome Browser (genome.ucsc.edu) and BLAT. We tested for the presence of the Apl/Art duplication in 20 D. yakuba and 20 D. simulans genomes34 by simulating the duplication in the D. simulans 2.01 or D. yakuba r1.3 reference genomes, mapping the paired-end sequencing reads to the simulated references using bwa mem 0.7.1235, and searching for read pairs correctly spanning the unique tandem duplication junction. We found no uniquely-mapped read pairs spanning the unique junction in any of the 40 genomes, supporting the conclusion that the Apl/Art tandem duplication is specifically found in D. melanogaster and is not simply missing from the D. yakuba and D. simulans reference genome assemblies. We checked if the duplication is segregating in D. melanogaster populations by analyzing whole genome re-sequencing data from the 97 primary core Drosophila Population Genomics Project phase 2 (DPGP2) genomes36. We required an individual to have at least three reads uniquely mapped (spanning) to each of the three unique breakpoints to be called as 'present'.

RNAi strain construction and screening

We generated RNAi lines specifically targeting Apl or Art following Dietzl et al. (2007)37. We designed RNAi hairpins using the E-RNAi server (http://www.dkfz.de/signaling/e-rnai3/; Supplementary Table 1). Constructs were injected into VDRC 60100 at 250 ng/µL with 500 ng/uL phiC31 recombinase mRNA and transformants isolated using Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (BDSC) stock 9325. We ensured that our RNAi constructs were inserted only at 2L:9,437,482 using PCR following Green et al. (2014)38. We drove RNAi using lines constitutively expressing GAL4 under control of the Actin5C or αTubulin84B promoters. Control crosses used VDRC 60100 flies crossed to driver strains. Five males and five virgin driver females were crossed for 9 days and F1s counted 19 days after crossing (Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). Apl and Art qPCR primers were designed using Primer-BLAST and confirmed using PCR and Sanger sequencing (Supplementary Table 1). We extracted RNA from sets of 16 flies (8 females and 8 males) in triplicate from each cross using TRIzol (Thermo Fisher, USA), treated ~2 µg RNA with RNase-free DNase I (Invitrogen, USA), and used 2 µL in cDNA synthesis with SuperScript III (Invitrogen, USA) using oligo(dT)20 primers. qPCRs used iTaq™ Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, USA) and 400 nM each primer and were run on a Bio-Rad C1000 Touch thermal cycler with CFX96 detection system (BioRad, CA). Expression levels were normalized using the ΔΔCT method and RpL32. qPCR primer efficiencies were tested using a 8-log2 dilution series (Supplementary Table 1).

CRISPR/Cas9-induced Apl and Art knockout, rescue, and analyses

We induced large deletions encompassing the Apl or Art translation start sites following Bassett and Liu (2014)39. We designed gRNAs using the FlyCRISPR Optimal Target Finder40 and injected gRNAs (500 ng/µL each) into BDSC 5459041. Mutants were isolated using BDSC 4534 (w*; Sb1 /TM3, P{w+mC, Act-GFP}, Ser1). F1 flies without deletions in Apl or Art were maintained as balanced lines and used as controls in fertility and lethality experiments. Rescue lines were constructed following Supplementary Fig. 2. Lethality was measured by crossing 20 balanced flies of each sex in at least triplicate and comparing the proportion of homozygotes recovered between deletion lines and controls (Supplementary Tables 4 and 5). Fertility effects were measured by crossing individual 3 – 5 day old virgin flies to two BDSC 54590 flies for 9 days and counting total F1 progeny at 19 days. At least 30 crosses were used for each line and all control and experimental crosses were performed identically (Supplementary Tables 6 and 7).

RNA-seq data analysis

We downloaded raw RNA-seq reads from the NCBI Short Read Archive. GEO Accessions GSE31302 and GSE99574 contain RNA-seq data from multiple Drosophila species created by Brian Oliver’s group at the National Institutes of Health’s Developmental Genomics Section, Laboratory of Cellular and Developmental Biology, NIDDK. Reads were unpacked using the SRA toolkit, and mapped to the appropriate reference genome using TopHat v2.1.142, 43. We then calculated relative expression levels using Cufflinks 2.2.144. Reference genomes and annotations were downloaded from FlyBase. We used the following reference genome versions and SRA files: D. melanogaster 6.18 (SRR5639563 – 610), D. simulans 2.02 (SRR330565 – 573), D. yakuba 1.04 (SRR5639521 – 562), D. ananassae 1.04 (SRR5639269 – 310), D. pseudoobscura 3.03 (SRR5639395 – 436), D. persimilis 1.3 (SRR5639353 – 394), D. willistoni 1.04 (SRR5639479 – 520), D. mojavensis1.03 (SRR5639311 – 352), and D. virilis 1.05 (SRR5639437 – 478). We are very grateful to Brian Oliver and his group for generating these data and making them available.

Testis and egg chamber staining and microscopy

Testis used for antibody staining were prepared following Kibanov et al. (2013)45. We used mouse α-core histone (EMD Millipore MAB3422; 1:3000), guinea pig α-Mst77F (1:200)46, rhodamine-phalloidin (Sigma-Aldrich P1951; 1:200), goat α-mouse Alexa Fluor 647 (1:500), and goat α-guinea pig Alexa Fluor 568 (1:1000). IF samples were visualized using a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope at the University of Chicago’s Department of Organismal Biology and Anatomy.

Population genomic data and analyses

We called SNPs in 17 primary core RG (Rwanda) samples from the DPGP2: RG2, RG3, RG4N, RG5, RG7, RG9, RG18N, RG19, RG22, RG24, RG25, RG28, RG32N, RG33, RG34, RG36, and RG38N. We downloaded raw sequencing reads from the NCBI Short Read Archive, mapped them to the release 6 assembly using bwa mem v0.7.12, and marked PCR duplicate reads with Picard Tools v1.95. We used GATK v3.4-0 with default parameters to recalibrate read base quality scores on individual sample alignment files47, 48, using DPGP SNP calls as known variant sites49. SNPs were called using the GATK's HaplotypeCaller in GVCF mode with default settings except sample ploidy was set to 1 and heterozygosity was set to 0.0075249. Samples were jointly genotyped with GATK's GenotypeGVCFs with default parameters except heterozygosity and ploidy listed above, then hard filtered by the following criteria: |BaseQRankSum| > 2.0, |ClippingRankSum| > 2.0, MQRankSum < - 2.0, ReadPosRankSum < - 2.0, a per-sample genotype phred score < 30, and called in < 9 individuals. This filtered VCF was used for all polymorphism and HKA analyses.

HKA-like calculations

We aligned the D. simulans release 2.01, D. sechellia release 1.3, D. yakuba release 1.04, and D. erecta release 1.04 genome assemblies to the release 6.09 D. melanogaster sequence following the UCSC Genome Browser pipeline for reference-guided multi-species alignments using roast v3 (part of the multiz 11.2 package)50, 51. Analyses requiring polarized SNP states only used SNPs where one of the D. melanogaster SNP states unambiguously matched the state in species from both the D. yakuba and D. simulans clades. HKAl statistics were calculated in sliding windows of 250 polarized sites with 50 site step to avoid low polymorphism and divergence in duplicate regions themselves17. The expected proportion of segregating to diverged sites (1.093) used in the HKAl test was calculated using the entirety of 3L. The 250-site window centered on the duplicated regions was used to represent them. The results were also significant using sliding windows of 100/50, 100/100, and 250/250 (χ2 p < 10−24 and empirical p < 10−3 in all cases).

dN/dS calculations

The longest Apl/Art ortholog coding sequences from D. simulans (GD14650), D. sechellia (GM25647), D. yakuba (GE19865), D. erecta (GG13567), and D. ananassae (GF23922) were collected from FlyBase release 2015_05 and aligned using TranslatorX v1.1 with MUSCLE v3.8.3152, 53. We estimated dN and dS for each branch under a free-ratio model using PAML4.7a23 and generated confidence intervals using bootstrapping the alignment and re-running the analysis 10,000 times

Statistical analyses and results

We verified the Welch’s t test54 assumption of normality using Shapiro-Wilk tests55 and present the results in Supplementary Tables 3, 5, 7, and 9 along with full t test data. All statistical analyses were performed in R 3.1.356. Confidence intervals reported in the main text and figures are means ± 1.96 standard deviations unless otherwise noted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Renkawitz-Pohl for providing antibodies; S. Horne-Badovinac, C. Stevenson, T. Davis, and I. Rebay for help with staining, microscopy, and discussion; G.Y-C. Lee for advice on population genomics analyses; and members of the Long lab, M. Kreitman, R. Hudson, E. Ferguson, and L. Harshman for valuable discussion. We are also indebted to an anonymous reviewer for suggesting the possibility of convergent evolution in D. pseudoobscura, and two other anonymous reviewers for their helpful criticisms. NWV was supported by NIH Genetics and Regulation Training Grant T32GM007197 and a NSF GRF. ML was supported by NSF1026200, NIH R01GM100768-01A1 and R01GM116113.

Footnotes

Data availability

All stocks, reagents, and scripts are available from the authors upon request.

Author contributions

NWV and ML designed the study, NWV collected and analyzed data with ML, NWV and ML wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information is available for this paper.

References

- 1.Lande R. Sexual dimorphism, sexual selection, and adaptation in polygenic characters. Evolution. 1980;34:292–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1980.tb04817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Partridge L, Hurst LD. Sex and conflict. Science. 1998;281:2003–2008. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5385.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonduriansky R, Chenoweth SF. Intralocus sexual conflict. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2009;24:280–288. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parsch J, Ellegren H. The evolutionary causes and consequences of sex-biased gene expression. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2013;14:83–87. doi: 10.1038/nrg3376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gallach M, Betrán E. Intralocus sexual conflict resolved through gene duplication. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2011;26:222–228. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Connallon T, Clark AG. The resolution of sexual antagonism by gene duplication. Genetics. 2011;187:919–937. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.123729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wyman MJ, Cutter AD, Rowe L. Gene duplication in the evolution of sexual dimorphism. Evolution. 2012;66:1556–1566. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohno S. Evolution by Gene Duplication. Springer-Verlag; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Innan H, Kondrashov F. The evolution of gene duplications: classifying and distinguishing between models. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010;11:97–108. doi: 10.1038/nrg2689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Long M, VanKuren NW, Chen S, Vibranovski MD. New gene evolution: little did we know. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2013;47:307–333. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-111212-133301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chippindale AK, Gibson JR, Rice WR. Negative genetic correlation for adult fitness between sexes reveals ontogenetic conflict in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:1671–1675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041378098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morrow EH, Stewart AD, Rice WR. Assessing the extent of genome-wide intralocus sexual conflict via experimentally enforced gender-limited selection. J. Evol. Biol. 2008;21:1046–1054. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Innocenti P, Morrow EH. The sexually antagonistic genes of Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000335. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Obbard DJ, et al. Estimating divergence dates and substitution rates in the drosophila phylogeny. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2012;29:3459–3473. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keightley PD, et al. Analysis of the genome sequences of three Drosophila melanogaster spontaneous mutation accumulation lines. Genome Res. 2009:1195–1201. doi: 10.1101/gr.091231.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rogers RL, Hartl DL. Chimeric Genes as a Source of Rapid Evolution in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2012;29:517–29. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hudson RR, Kreitman M, Aguadé M. A Test of Neutral Molecular Evolution Based on Nucleotide Data. Genetics. 1987;116:153–159. doi: 10.1093/genetics/116.1.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ford MJ, Aquadro CF. Selection on X-linked genes during speciation in the Drosophila athabasca complex. Genetics. 1996;144:689–703. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Timinszky G, et al. The importin-β P446L dominant-negative mutant protein loses RanGTP binding ability and blocks the formation of intact nuclear envelope. J. Cell Sci. 2002;115:1675–1687. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.8.1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gorlich D, Seewald MJ, Ribbeck K. Characterization of Ran-driven cargo transport and the RanGTPase system by kinetic measurements and computer simulation. EMBO J. 2003;22:1088–1100. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harel A, Forbes DJ. Importin-β: Conducting a much larger cellular symphony. Mol. Cell. 2004;16:319–330. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gates J. Drosophila egg chamber elongation: insights into how tissues and organs are shaped. Fly. 2012;6:213–227. doi: 10.4161/fly.21969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang Z. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2007;24:1586–1591. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rice WR. Sex chromosomes and the evolution of sexual dimorphism. Evolution. 1984;38:735–742. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1984.tb00346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boughman JW. In: The Princeton Guide to Evolution. Losos JB, et al., editors. Princeton University Press; 2014. pp. 520–528. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pavlicev M, Wagner GP. A model of developmental evolution: selection, pleiotropy and compensation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2012;27:316–322. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zera AJ, Harshman LG. The physiology of life history tradeoffs in animals. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2001;32:95–126. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harshman LG, Hoffmann AA. Laboratory selection experiments in Drosophila: what do they really tell us? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2000;15:32–36. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5347(99)01756-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ranz JM, Castillo-Davis CI, Meiklejohn CD, Hartl DL. Sex-Dependent Gene Expression and Evolution of the Drosophila Transcriptome. Science. 2003;300:1742–1745. doi: 10.1126/science.1085881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ellegren H, Parsch J. The evolution of sex-biased genes and sex-biased gene expression. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2007;8:689–698. doi: 10.1038/nrg2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou Q, et al. On the origin of new genes in Drosophila. Genome Res. 2008;18:1446–55. doi: 10.1101/gr.076588.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang YE, Vibranovski MD, Krinsky BH, Long M. Age-dependent chromosomal distribution of male-biased genes in Drosophila. Genome Res. 2010;20:1526–1533. doi: 10.1101/gr.107334.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen S, et al. Frequent Recent Origination of Brain Genes Shaped the Evolution of foraging behavior in Drosophila. Cell Rep. 2012;1:118–132. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2011.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rogers RL, et al. Landscape of Standing Variation for Tandem Duplications in Drosophila yakuba and Drosophila simulans. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2014;31:1750–1766. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pool J, et al. Population Genomics of sub-saharan Drosophila melanogaster: African diversity and non-African admixture. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1003080. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dietzl G, et al. A genome-wide transgenic RNAi library for conditional gene inactivation in Drosophila. Nature. 2007;448:151–6. doi: 10.1038/nature05954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Green EW, Fedele G, Giorgini F, Kyriacou CP. A Drosophila RNAi collection is subject to dominant phenotypic effects. Nat. Methods. 2014;11:222–3. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bassett A, Liu JL. CRISPR/Cas9 mediated genome engineering in Drosophila. Methods. 2014;69:128–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2014.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. [Accessed: 1st January 2016];flyCRISPR Optimal Target Finder. Available at: http://tools.flycrispr.molbio.wisc.edu/targetFinder/.

- 41.Port F, Chen H-M, Lee T, Bullock SL. Optimized CRISPR/Cas tools for efficient germline and somatic genome engineering in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2014;111:E2967–76. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1405500111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:357–360. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim D, et al. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R36. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-4-r36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trapnell C, et al. Differential analysis of gene regulation a t transcript resolution with RNA-seq. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:46–53. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kibanov MV, Kotov AA, Olenina LV. Multicolor fluorescence imaging of whole-mount Drosophila testes for studying spermatogenesis. Anal. Biochem. 2013;436:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rathke C, et al. Distinct functions of Mst77F and protamines in nuclear shaping and chromatin condensation during Drosophila spermiogenesis. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2010;89:326–338. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McKenna A, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: A MapReduce framework for analyuzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20:1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van der Auwera GA, et al. Current Protocols in Bioinformatics. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Langley CH, et al. Genomic variation in natural populations of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2012;192:533–598. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.142018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Blanchette M, et al. Aligning Multiple Genomic Sequences With the Threaded Blockset Aligner. Genome Res. 2004;14:708–715. doi: 10.1101/gr.1933104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harris RS. Improved Pairwise Alignment of Genomic DNA. The Pennsylvania State University; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Edgar RC. MUSCLE : multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Abascal F, Zardoya R, Telford MJ. TranslatorX : multiple alignment of nucleotide sequences guided by amino acid translations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:7–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Welch BL. The generalization of ‘Student’s’ problem when several different population variances are involved. Biometrika. 1947;34:28–35. doi: 10.1093/biomet/34.1-2.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shapiro SS, Wilk MB. An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples) Biometrika. 1965;52:591–611. [Google Scholar]

- 56.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 57.van der Linde K, Houle D, Spicer DS, Steppan SJ. A supermatrix-based molecular phylogeny of the family Drosophilidae. Genet. Res. 2010;92:25–38. doi: 10.1017/S001667231000008X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.