Making the right choices in life is an absolute. It is a given. The assumption that whatever decision we make is the correct one for us as an individual underpins and governs all aspects of our personal and our professional lives. This philosophy should, of course, apply to surgical practice. The Choosing Wisely initiative launched originally in the USA [1] poses the question as to whether or not we, as doctors—and our patients—can apply this philosophy in determining the most appropriate care pathway. As always, timing is everything, and it seems to me that, at least in the UK, there could never be a better opportunity to adopt the choosing wisely campaign.

There are several reasons pointing to this imperative. The majority of our health care is delivered by the public sector through our National Health Service which currently faces unprecedented pressures. Data from the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in 2015 [2] highlights the exponential growth on health care expenditure across Europe and the USA—and identifies the UK expenditure limping along towards the bottom of the league table. UK National statistics show a projected population increase from 64.6 to 72.7 million between 2019 and 2039 [3] along with a 14–29% increase in people living into their seventh, eighth and ninth decades [3]. This is unlikely to be significantly affected by Brexit. Clearly, if we are to cope with these demographic changes, our health care system will need to adapt especially in the light of eye-watering projections in funding shortfall in our health (9 billion by 2030) and social care (13 billion) budgets [4]. From a health care perspective, we are entering the perfect storm.

You might ask why this is relevant to surgeons practicing in India? It is clear from my conversations at ASICON 2017 in Jaipur that we all face similar problems—increasing demand balanced against finite human and financial resource—it is only the order of magnitude where we differ.

So how or indeed can initiatives like ‘Choosing Wisely’ help us all with some of these problems? To answer this question, we should first look at the campaign’s origins and purpose. The work began in 2009 as an initiative of the National Physicians Alliance, a US organisation looking to achieve high-quality affordable health care for all—especially relevant in a nation top of the leader board for health care expenditure where up to 37% of patients in various health care systems cannot afford to pay for parts or any of their health care episodes [5]. The work was taken forward by the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation who coined the term ‘Choosing Wisely’ (Fig. 1) with a core aim to ‘reduce waste in health care’ and to ‘avoid risks associated with unnecessary treatment’ [1]. Carotid endarterectomy (10% overuse) and hysterectomy (14% overuse) have been cited as good examples of procedures being used inappropriately [6]. Specialty associations in the USA were asked to provide ‘Top 5’ lists of procedures perceived as being of low value to patients and within months 70 organisations had come up with over 300 recommendations. An example of some of those proposed by the American College of Surgeons is shown in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Choosing Wisely: logo

Table 1.

American College of Surgeons list of five

| i) No CT for suspected appendicitis in children |

| ii) Avoid preoperative CXR if history/physical examination normal |

| iii) No colorectal screening in asymptomatic patients with less than 10 years life |

| expectancy |

| iv) Avoid whole body CT in minor/single system trauma |

| v) In stages I and II, breast cancer undertakes sentinel node biopsy before axillary lymph node staging |

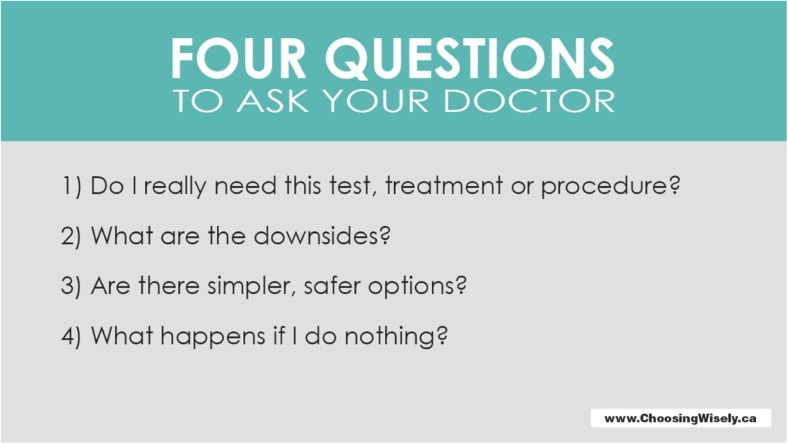

It is probably true to say that—as with many things—after the initial flush of enthusiasm, some momentum was lost until the project rekindled under the leadership of Professor Wendy Reid, a Toronto paediatric physician. Central to her approach was the avoidance of ‘low value care’ eliminating tests or procedures of limited value in the context of a particular patient need. Her triad of recommendations underpinning the project (Table 2) resonated with the profession, and since then, there has been no looking back. The campaign supported by a strong visual advertising campaign (Figs. 2 and 3) and wide stakeholder engagement (patients, doctors, media, institutions) regained momentum. With an active campaign running in America and Canada, earlier adopters beyond North America included the Netherlands, Switzerland, Japan, Australia and the UK.

Table 2.

Choosing Wisely: key principles

| i) Use evidence-based lists |

| ii) 4 questions patients and doctors should consider before choosing a care pathway |

| iii) Avoid low value care |

Fig. 2.

Choosing Wisely: more is not always better

Fig. 3.

Choosing Wisely: four questions

The ‘Choosing Wisely in the UK’ campaign was launched by the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges (an umbrella organisation representing all the UK and Ireland Colleges) in 2015 [7] again with a focus on encouraging doctors to stop using interventions with no (or limited/unproven) benefit to patients. The Surgical Forum of Great Britain and Ireland (representing the Surgical Colleges and Specialty Surgical Societies) has taken a slightly different view with an emphasis upon the need for avoiding paternalistic approaches to choices in health care emphasising the value of joint decision-making with our patients. Instead of seeking out a top 5 list of procedures to avoid, we recommend looking to set thresholds for procedures—for example avoiding a surgical intervention on an asymptomatic but incidentally discovered inguinal hernia.

The implementation of ‘Choosing Wisely’ across the UK will differ taking into account the devolved health care of the four constituent nations—England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. While England embraces the term ‘Choosing Wisely’, Wales has adopted ‘Prudent Practice’ a variant suited to its own health care needs and in Scotland ‘Realistic Medicine’ embraces the core principles of ‘Choosing Wisely’ (Table 3; Fig. 4). Launched in 2015, ‘Realistic Medicine’ [8] has been an undoubted success with our patients, practitioners and politicians alike with over three million hits on the Realistic Medicine Website within the first 12 months.

Table 3.

Realistic Medicine: primary objectives

| i) Shared decision-making |

| ii) Reduce harm and waste |

| iii) Manage risk better |

| iv) Develop a personalised (bespoke) approach to a patients care |

| v) Reduce unnecessary variation in practice and outcomes |

| vi) Become improvers and innovators |

Fig. 4.

Realistic medicine

Earlier on, I mentioned the importance of timing. Part of the enthusiasm for the campaign may be explained by several additional drivers for change in the UK—the Montgomery Ruling [9] and several initiatives to reduce unwanted variation in clinical practice. In early 2015, Nadine Montgomery was awarded £5 million by the Supreme Court after a decade of legal wrangling. Her court case arose following delivery of her baby boy 16 years previously after a prolonged labour caused by shoulder dystocia. Her child was born with severe handicap as a consequence of the complicated delivery. The legal argument was based on Montgomery having been given insufficient information to make an informed decision and that had she been fully aware of the all of the risks she would have opted for a caesarean section. This ruling has set a legal precedent heralding an end of medical paternalism and in the UK changing for ever the style and content of informed decision-making and consent.

Another key strand of Realistic Medicine relates to the quality improvement agenda permeating UK clinical practice and a need to eliminate variation in outcomes. The very existence of an Atlas of Variation produced by NHS England [10] demonstrates the need for work in this area. Many examples of the problems we face are well documented. The tenfold variations in 30-day mortality rates following emergency laparotomy as reported by Saunders et al. in 2012 [11] led to the establishment of a UK emergency laparotomy network which reports through an annual audit cycle (National Emergency Laparotomy Audit, NELA). Its value clearly demonstrated by incremental improvements in many parameters including survival [12]. GIRFT (Get It Right First Time) is another initiative [13] which set out to improve outcomes in orthopaedic practice—for example, reducing hospital length of stay, reducing readmission rates and to tackle the complex problem of cost control over prosthesis supplied by different manufacturers. The success of this approach can be measured by the roll out of the GIRFT programme across all the other surgical specialties in England and has already shown a wide variation in stoma rates for colorectal surgery and day case surgery rates for laparoscopic anti-reflux procedures. So, there are many reasons why incorporating a ‘Choosing Wisely’ philosophy into health care delivery seems appropriate.

But what may limit its success? Why do we, for example, organise an ‘unnecessary test’? Interesting data from a nationwide survey of 600 US physicians during the early roll out of ‘Choosing Wisely’ shows that, as expected, malpractice concerns top the list but patients insistence on investigation even when the clinician feels there is likely to be little benefit and the wish to keep a patient ‘happy’ are also a high priority [14]. A clear marker that there is an opportunity for better informed shared decision-making. These problems are not unique to the USA. Elsewhere, in Japan, demanding patients ask for expensive investigations and expect high end interventions and wherever there is the conflict of working in a fee for service payment system, the best intentions of a practitioner aiming to choose wisely may be undone.

So is there any evidence that adopting ‘Choosing Wisely’ does have an impact? It is probably too early to say. But there is some indirect evidence already. In Toronto, a toolkit for reducing unnecessary investigations in preoperative clinics ‘Drop the Preop Campaign’ has made significant inroads in the use of ‘routine’ radiology, haematology and biochemistry preoperative testing reducing requests by up to 40%. It may be a simplistic extrapolation to believe this will divert a limited resource to other areas of need within the health care system but there is certainly some logic to the argument. One thing seems clear ‘Choosing Wisely’ is not meant as a cost cutting strategy [15]. Inevitably, there will be a financial ‘glass ceiling’ beneath which we must all operate. ‘Choosing Wisely’ may help us to redistribute our precious resources within those confines and enable us to provide the best care for the greatest number of patients. As for the future of the programme, there will always be arguments [15] and counterarguments [16] as to the relative merits of individual procedures each corner strongly contested by their proponents and antagonists. For us as surgeons, it maybe that the greatest value of the ‘Choosing Wisely’ campaign will be to encourage all of us to engage in that broad conversation with our patients that will lead to a truly shared decision in their care. ‘Choosing Wisely’ is a timely reminder that we are much more than surgical technicians.

References

- 1.Levison W, Kallewaard M, Bhatia RS, et al. ‘Choosing Wisely’: a growing international campaign. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24:167–174. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Focus on health care spending @ OECD Health Statistics 2015 www.oecd.org

- 3.National Population Projections: 2014-based statistical bulletin. www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity

- 4.NHS funding shortfall set to widen while social care financing ‘unsustainable’; new report reveals. The Health Foundation. 2015. http://www.health.org.uk/news/nhs-funding-shortfall-set-widen-while-social-care-financing-unsustainable-new-report-reveals

- 5.Osborne R, Schoen C (2013) The Commonwealth Fund 2013 International Health Policy Survey in eleven countries. www.commonwealthfund.org

- 6.How many more studies will it take? A collection of evidence that our health care systems can do better. New England Healthcare Institute 2007 www.nehi.net

- 7.Mahotra A, Maughan D, Ansell J, et al. Choosing Wisely in the UK: the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges’ initiative to reduce the harms of too much medicine. BMJ. 2015;350:1–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calderwood C (2016) Realistic Medicine CMO Scotland Report. www.gov.scot/Publications/2016

- 9.Sokol DK. Update on the UK law of consent. BMJ. 2015;350:hi481. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tackling unwarranted variation in healthcare across the NHS. Public Health England 2015 www.gov.uk

- 11.Saunders DI, Murray D, Pitchel AC et al Variations in mortality after emergency laparotomy. BJA 109(3):368–375 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Third NELA Patient Audit report. www.nela.org.uk

- 13.Briggs R (2012) Getting it right first time. www.rhoh.nhs.uk

- 14.Born KB, Coulter A, Han A, Ellen M, Peul W, Myres P, Lindner R, Wolfson D, Bhatia RS, Levinson W. Engaging patients and the public in choosing wisely. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017;26:687–691. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-006595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malik HT, Marti J, Darzi A, Mossialos E. Savings from reducing low-value general surgical interventions. BJS. 2018;105:13–25. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patterson-Brown S. Cost effective surgery for better outcomes. BJS. 2018;105:11–12. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]