Abstract

The aim of this exploratory study was to assess the safety and clinical effects of autologous umbilical cord blood (AUCB) infusion in children with idiopathic autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Twenty‐nine children 2 to 6 years of age with a confirmed diagnosis of ASD participated in this randomized, blinded, placebo‐controlled, crossover trial. Participants were randomized to receive AUCB or placebo, evaluated at baseline, 12, and 24 weeks, received the opposite infusion, then re‐evaluated at the same time points. Evaluations included assessments of safety, Expressive One Word Picture Vocabulary Test, 4th edition, Receptive One Word Picture Vocabulary Test, 4th edition, Clinical Global Impression, Stanford‐Binet Fluid Reasoning and Knowledge, and the Vineland Adaptive Behavior and Socialization Subscales. Generalized linear models were used to assess the effects of the response variables at the 12‐ and 24‐week time periods under each condition (AUCB, placebo). There were no serious adverse events. There were trends toward improvement, particularly in socialization, but there were no statistically significant differences for any endpoints. The results of this study suggest that autologous umbilical cord infusions are safe for children with ASD. Tightly controlled trials are necessary to further progress the study of AUCB for autism. stem cells translational medicine 2018;7:333–341

Keywords: Stem cells, Umbilical cord blood, Autologous, Clinical trials, Autism, Language tests

Significance Statement.

There is no single medical cause for autism, and there are very few controlled studies. This research suggests that stem cells from autologous cord blood are safe and potentially have an impact on socialization for children with autism. The safety and observed changes warrant further investigation into the potential for cellular therapy as an intervention in pediatric neurologic conditions that do not require bone marrow replacement. This research provides insight and suggestions for future research conducted using stem cells from autologous umbilical cord to treat autism.

Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder that affects 1:68 children in the U.S. 1. While there are treatments for comorbid conditions as well as behavioral interventions for the core deficits, there is currently no cure. Based on its definition, ASD symptoms include deficits in communication and language as well as social reciprocity, and self‐stimulatory or perseverate type behaviors 2. These core features may all reflect a lack of integrative communication between the different brain regions that make up normal executive, social/emotional, and communicative behaviors that define normal development. ASD is a heterogeneous disorder and multiple risk factors including genetic predisposition, prenatal and postnatal environmental exposures, and immune dysregulation may contribute to its development 3, 4, 5. Twin studies have reported a higher concordance rate of ASD in monozygotic twins compared with dizygotic twins, however the monozygotic twin concordance rate is far less than 100% suggesting a distinct nongenetic contribution 6, 7. Current opinion suggests that ASD may result from the occurrence of several risk factors. Immune factors may be one important component of this theory.

Systemic immune dysfunction in individuals with ASD has been reported in several publications; however, the exact dysfunction has been variable 8. This variability is to be expected in a heterogeneous disease with multiple potential etiologies such as ASD. Maternal immune activation has been suggested as a potential environmental risk factor for developing ASD 3, 8. In addition, post‐mortem analysis of brains of individuals with ASD indicated microglial activation and neuroinflammation 9, 10. Historically, the brain has been considered to be immunologically privileged, however a recent study suggested that lymphatic endothelial cells line the dural sinuses in mice 11. This might explain findings from earlier studies suggesting that the central nervous system undergoes constant immune surveillance in the meningeal compartment 12, 13.

Brain structure and connectivity in ASD may also be abnormal. Post‐mortem and brain MRI imaging studies have suggested that a period of neuronal overgrowth and hyperconnectivity in early childhood may be followed by hypo‐connectivity later in life 9, 10. Other studies have suggested that the brains in individuals with ASD might have areas of both hypo and hyperconnectivity 14. Immune dysregulation including altered cytokine profiles, T‐cell and B‐cell dysfunction, and in utero stress factors may alter the fetal environment and change neuronal interaction and connectivity via glial cell activity 8, 9, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22. One study found that the ratio of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF‐α) in cerebrospinal fluid versus serum may be elevated 19. Other studies have shown activated microglia and elevation of cytokines such as IL‐6 and MCP‐1 9, 18., Maternal and ASD subject serum circulating autoantibodies have been described 20. Prior studies have examined the use of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), steroid therapy, and specific medication for anti‐inflammatory inhibition of cytokines for immune dysfunction associated with ASD 17, 23, 24, 25, 26. Experience with immune dysfunction and ASD therapies to date have highlighted the lack of consensus of what is the best approach with standard medications. Direct cytokine inhibition in animal models and in a human pilot study suggests a correlation of reduced TNF‐α and interleukin beta (IL‐1β) with improved outcomes 27.

Umbilical cord blood (UCB) contains a mixed population of cells and is rich in hematopoietic stem cells. Theoretically, UCB has the potential to regulate an abnormally activated immune system which may potentially improve neuronal function 28, 29, 30. Umbilical cord tissue and UCB have also been used to regulate immune dysfunction 31. Preclinical studies have reported that cells from intravenously infused human UCB can migrate to the parenchyma of injured brain and alleviate neurological impairment in animal models of perinatal brain injury 32, 33, 34. The demonstrated functional improvements were not due to cell differentiation and repopulation, but rather are hypothesized to be a transient paracrine effect of the infused cells upon the host cells. One proposed mechanism of action is that the donor cells secrete factors that might promote endogenous repair and angiogenesis 35.

Currently, UCB has been used as a source of hematopoietic stem cells in over 35,000 transplants worldwide for the treatment of hematological and immunological conditions 36, 37, 38. The use of autologous UCB (AUCB) offers little risk of immune system reactions. A pilot study assessing the safety of AUCB infusions in newborn infants with hypoxic‐ischemic encephalopathy reported that the infusions were well tolerated and no adverse events were reported 39. In a separate study, 76 children with hydrocephalus received up to four AUCB infusions and no infusion‐related adverse events were reported 40. A publication describing AUCB infusions in 184 infants and children with cerebral palsy, congenital hydrocephalus, or other brain injuries reported that 1.5% had only mild hypersensitivity reactions (hives and/or wheezing) with no additional adverse events reported up to 3 years later 41.

Considered overall, the research to date investigating AUCB infusions has established safety in a variety of pediatric populations, however, the question of efficacy remains unanswered because of a lack of studies conducted as randomized clinical trials or that include control groups. A recent meta‐review of four randomized‐controlled trials and one nonrandomized clinical trial compared the use of different cell types in patients with cerebral palsy. This analysis suggested a small statistically significant intervention effect on gross motor scales with UCB being the most effective compared with other cell types analyzed 42.

The current research and clinical experience has established a sound rationale to support investigation of AUCB in patients with ASD. 8, 30, 31, 43 The objective of this exploratory study was to assess the safety of a single infusion of AUCB in subjects with ASD and document changes in language, social behavior, and learning.

Materials and Methods

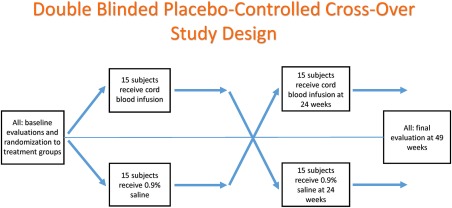

This study was a randomized, blinded, placebo‐controlled exploratory trial with treatment arm crossover at 24 weeks. Participants were infused with either AUCB or placebo, evaluated at baseline, 12, and 24, weeks, infused with the opposite product, then evaluated again at 12 and 24 weeks post infusion. (Fig. 1) This study was approved by the Sutter Health Sacramento Institutional Review Committee and registered at clinicaltrials.gov number NCT01638819.

Figure 1.

Study design for randomized, double‐blinded, placebo‐controlled, crossover study to assess the safety and efficacy of stem cells from autologous umbilical cord blood to improve core symptoms in children with autism spectrum disorder.

Participants

Eligible subjects were children ages 2 to 7 years with a diagnosis of ASD based on DSM‐IV‐TR and the Autism Diagnostic Observational Schedule (ADOS) administered by the neuropsychologist and corroborated by the Principal Investigator (PI). Participants were required to have AUCB cryopreserved at Cord Blood Registry (CBR, South San Francisco, CA) processed on the AutoXpress (AXP) Platform (Cesca Therapeutics, Rancho Cordova, CA). Children with a diagnosis of Asperger or Pervasive Developmental Disorder‐Not Otherwise Specified were not eligible to participate. Review of the potential subjects’ medical histories were completed to rule‐out genetic conditions or other potentially confounding medical diagnoses. Subjects were required to have documentation of a normal karyotype, Fragile X DNA testing, and chromosomal microarray analysis. Subjects were also required to have 24 hours EEG studies within 6 months of baseline in order to define the population better and determine if EEG abnormalities would change during the study.

Cord Blood Unit Criteria and Dosing

Cord blood units were required to meet the following criteria as documented at the time of storage at CBR: post‐processing total nucleated cell (TNC) count at least 10 × 106/kg, viability > 85%, negative sterility cultures, maternal infectious disease marker testing performed and negative (HIV, Hepatitis B and C, HLTV, syphilis) or, if not performed at time of unit storage, confirmed negative through prenatal medical record review. The cord blood unit identity was confirmed via HLA typing of a cord blood test aliquot and peripheral blood of the study subject prior to cord blood unit release. ABO and Rh status were also reviewed as part of identity verification. In addition, a cord blood aliquot was tested for TNC, viability, colony forming unit, and CD34+ cell count to confirm potency prior to cord blood unit release. Cord blood units were initially cryopreserved in a bag consisting of two compartments with an 80%/20% volume configuration. Based on the total available TNC count, only a portion of the cord blood unit was required to meet the minimum cell dose requirements of the study. Either the 80% or 20% compartment was released from CBR for use in the trial and the remainder of the unit remains in storage for potential future use.

Subject Enrollment and Randomization

After informed consent and screening for eligibility, subjects were enrolled in the study and randomized to a treatment arm. The computerized randomization program assigned subjects 1:1 in blocks of 4 to group A (infusion of AUCB first, infusion of 0.9% saline placebo second) or group B (infusion of 0.9% saline placebo first, infusion of AUCB second).

Cord Blood Unit Preparation and Administration

The cryopreserved cord blood units were shipped from CBR to the local cell therapy laboratory in a dry shipper validated to maintain appropriate temperature. Cord blood units remained cryopreserved until the scheduled infusion date as indicated in the randomization scheme. On the day of the AUCB infusion, the AUCB product arrived at the pediatric infusion outpatient clinic via courier from the cryopreservation lab in a temperature monitored dry‐shipper. Preparation of the product for infusion was conducted in a room separate from study subjects and parents. The blinded PI was not present for the infusion, but was present for pre‐infusion monitoring and post‐infusion safety monitoring on the following day.

In preparation for the AUCB infusion, authorized study personnel with knowledge and experience in transplant procedures removed the product bag from the dry shipper, washed the sealed product bag with chlorohexidine, and warmed the sample to 37°C in a sterile water bath. Once the AUCB product was thawed, the unblinded transplant physician extracted the AUCB product from the bag using a sterile syringe diluted with sterile saline to a total volume of 50 ml. After standard blood filtration, the diluted product was administered via peripheral IV site by direct injection via syringe. A small sample of the AUCB product was saved for post‐thaw testing. Premedication of 0.5 mg/kg IV diphenhydramine (Benadryl) was administered in 10 ml saline and dispensed as 50 mg/ml. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was used as a cryoprotectant agent for the AUCB during freezing and storage. Because DMSO has a garlic‐like odor, all subjects consumed garlic oil orally from a syringe or mixed with food to preserve blinding. In addition, small amounts of DMSO were placed in containers around the room to produce the odor of DMSO during the infusion. The IV bag and line were covered in cloth/tape to maintain blinding. Vital signs were taken within 30 minutes before start of the IV and every 15 minutes once the saline drip started until infusion (AUCB or placebo) was completed, which took between 5 to 15 minutes. Additionally, subjects were monitored for indications of adverse events and vital signs were monitored every 15 minutes for 1 hour following the infusion. Subjects were discharged after completion of the observation period if subjects were asymptomatic and showed no sign of allergic reaction or unstable vital signs. Subjects returned for an outpatient safety visit with the PI the day after the infusion to assess for infusion‐related side effects and obtain routine lab tests.

Post‐Thaw Cord Blood Unit Testing

A small sample of the cord blood unit was sent on ice by courier to the study laboratory to complete the following post‐thaw testing: sterility, % viability, CD34+ cell counts, and for most cases, CFU analysis. Toward the end of the study, the original lab used for all AUCB testing closed which required processing subsequent samples at a second lab. The second lab was unable to conduct CFU analysis.

Endpoint Testing

Safety

Evaluation of subject safety was conducted by obtaining a complete blood count, comprehensive chemistry panel, and urinalysis at the screening, safety, and follow‐up visits. Safety endpoints included documentation of adverse events as reported by the investigator at an office visit the day after the infusion. Parents were also asked to keep a diary of any observed changes in behavior, irritability, and language, which were discussed at the 12 and 24‐week follow‐up visits. Participants who had abnormal EEGs at baseline had repeat EEGs at 12 and 24 weeks. Abnormalities had to show specific bifrontal predominant generalized or focal spike wave activity predominantly in temporal central parietal regions.

Primary Endpoints

The primary outcome endpoints were the Expressive One Word Picture Vocabulary Test, 4th edition (EOWPVT‐4) and Receptive One Word Picture Vocabulary Test, 4th edition (ROWPVT‐4). The EOWPVT‐4 and ROWPVT‐4 are standardized measures of single word comprehension and expression respectively. These co‐normed tests are administered by a neuropsychologist and allow comparisons of a child's receptive and expressive vocabulary skills.

Secondary Endpoints

Secondary endpoints included: (a) Stanford Binet, 5th edition Fluid Reasoning (SBFR) and Knowledge (SBKN) subtests. These tests are administered by a neuropsychologist and provide a standardized assessment of verbal as well as nonverbal cognitive abilities across the life span; (b) Vineland Adaptive Behavior and Socialization Scales, 2nd edition for Communication, Daily Living Skills, Socialization, and Adaptive Behavior Composite (ABC). These are questionnaires completed by a parent or caregiver. Scores above 80 are classified using approximately the same ranges as IQ tests. Scores below 80 are categorized as borderline adaptive functioning (70–80); mildly deficient adaptive functioning (51–69); moderately deficient adaptive behavior (36–50); severely deficient adaptive behavior; (20–35); and markedly or profoundly deficient adaptive behavior (<20) 44. (c) Clinical Global Impression (CGI) subscales for Social, Receptive, and Expressive skills as rated by the PI based on clinical impressions. The baseline CGI is a measure of severity as rated on a Likert scale from 1 to 7. For this study, severity was categorized as minimal deficits (1–2.5), mild to moderate deficits (3–4.5), and severe deficits in social receptive and expressive speech functions (5.0+). At each subsequent visit, the PI rated patients on improvement from the previous visit on a scale of 1 to 7. For this study, improvement was categorized as improved (≤2.5), no change (3.0–3.5), and worse (4.0+). Subjects underwent in‐person testing for these study endpoints at baseline 12, and 24 weeks after infusion of each product.

Sample Size and Statistical Analysis

Fifteen patients in each treatment group were calculated as necessary to provide 84% power to detect a 7 (SD = 9.1) unit advantage for AUCB over placebo on the primary endpoint of ROWPVT (α = 0.05, two‐tailed) 45.

Histograms and normal probability plots were used to screen the data for outliers and assess normality of individual variables. Scatterplots, correlation coefficients, and means were used to assess the association between post thaw CD34 and percent viability with the primary endpoints. Generalized linear models were used to compare differences between responses on primary and secondary endpoints under the AUCB versus placebo conditions using all available observations. Analyses included the repeated effects of the response variables at the 12‐ and 24‐week time periods after infusion of each product (AUCB, placebo). Group of administration (AUCB first or placebo first) and the group X treatment interaction were included in the model as fixed effects. The analysis was designed to compare the mean difference as: [12 and 24 week AUCB – baseline AUCB] − [12 and 24 week placebo – baseline placebo]

A statistically significant interaction indicated presence of a carryover effect, meaning that differences in the response variable depended on administration group. For these variables, differences between the subjects that received AUCB first were compared with the subjects who received placebo first and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to compare the 12‐week and 24‐week scores between the groups after adjusting for baseline scores. Multiplicity was corrected for by controlling the false discovery rate (FDR) at a level of 0.05 for groups of end points where there was at least one statistically significant finding at the p < .05 level 46. Because this was an exploratory trial, both the raw p‐values and FDR p‐values were reported.

Results

Thirty subjects were randomized and all except one received both infusions. One subject received the baseline infusion and was lost to follow‐up leaving 29 subjects with complete data on primary and secondary endpoints. Table 1 provides the demographics and information regarding the AUCB that was infused. Ninety five percent of units tested post‐thaw demonstrated CFU growth.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and autologous umbilical cord blood unit characteristics of subjects that completed the study (N = 29)

| n (%) | Mean (Min–Max) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 4.53 (2.42–6.80) | |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 4 (13.8) | |

| Male | 25 (86.2) | |

| Weight (kg) | 19.21 (13–34) | |

| Racial/Ethnicity | ||

| Asian | 4 (13.8) | |

| White | 24 (82.8) | |

| Hispanic | 5 (17.2) | |

| Other | 1 (3.4) | |

| Abnormal EEG at baseline | 9 (31.0) | |

| ADOS | ||

| Social affect | 15.14 (6.00–22.00) | |

| Restricted and repetitive behavior | 3.76 (0.00–8.00) | |

| Comparison | 7.75 (3.00–10.00) | |

| Compartment infused | ||

| 80% | 21 (72.4) | |

| 20% | 8 (27.6) | |

| Viable total nucleated cell (vTNC) count infused ×106 (n = 22) | 335.09 (103.00–1,024.10) | |

| TNC dose infused × 106/kg (n = 22) | 16.16 (6.20–31.82) | |

| Total colony forming units (per 1 × 105) | 20 | 137.0 (0–360.00) |

| Percent viability post‐thaw, (flow cytometry 7‐AAD) | 53.73 (30.00–70.00) | |

| Percent viable CD34 – post‐thaw (n = 28) | 0.47 ± (0.08–1.48) |

Abbreviations: ADOS, Autism Diagnostic Observational Schedule; EEG, electroencephalogram.

There was no association between 12‐ and 24‐week EOWPVT and ROWPVT scores and post thaw total viability or CD34 count based on correlation coefficients and scatterplots. Stratification of the post thaw CD34 at the median of 0.44 showed that subjects who received an infusion above the median had lower baseline scores than subjects who received an infusion that was below the mean. However, there was little change over time between participants within a stratum. For example, ROWPVT scores for participants who received an infusion that was below the median were 82.64 ± 30.55 at baseline, 81.71 ± 26.56 after 12 weeks, and 84.79 ±24.74 after 24 weeks. ROWPVT scores for participants who received an infusion with a CD34 percent above the median were 76.80 ± 21.26 at baseline, 76.40 ± 20.37 after 12 weeks, and 76.40 ±19.23 after 24 weeks.

Safety

Table 2 shows the reported AEs and the likely relatedness of the events to the AUCB infusion. No adverse events required treatment. There were no observed allergic reactions or serious adverse events associated with the administration of AUCB. Nine of the 29 participants had abnormal baseline 24 hours EEG ambulatory results within 6 months of baseline. This reflects about average the percent of abnormal EEG percentage range found in this age group in other studies (30%–60%). There were no observed changes in EEGs at 12 or 24 weeks for subjects when in either group for patients who had abnormal EEGs at baseline.

Table 2.

Adverse events and potential relatedness to autologous cord blood infusion

| Relatedness | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | Probable (n) | Possible (n) | Not likely (n) | |

| Constitutional symptoms | 37 | 43% | 1 | 2 | 34 |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 3 | 3% | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 26 | 30% | 0 | 8 | 18 |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Neurological disorders | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pain | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pulmonary/Upper respiratory disorders | 11 | 13% | 0 | 0 | 11 |

| Reproductive system and breast disorders | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Psychiatric disorders | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Renal and urinary disorders | 9 | 10% | 2 | 4 | 3 |

| Total | 86 | 100% | 3 | 14 | 69 |

Clinical Global Impression

Table 3 shows the CGI baseline severity scores and number and percent in each improvement category at the 12‐ and 24‐week visits. Baseline CGI severity and expressive, receptive, and social improvement were similar for both groups.

Table 3.

Baseline severity Clinical Global Impression and improvement after 12 and 24 weeks under each condition

| Baseline severity (N = 29) |

12 week change from baseline (N = 29) |

24 week change from baseline (N = 29) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Mild to Moderate | Severe | Improved | No change | Worse | Improved | No change | Worse | |

| Expressive | |||||||||

| Placebo | 12(41.4) | 8(27.6) | 9(31.0) | 15(51.7) | 3(10.3) | 11(37.9) | 16(55.2) | 3(10.3) | 10(34.5) |

| AUCB | 14(44.8) | 7(24.1) | 8(27.6) | 15(51.7) | 4(13.8) | 10(34.5) | 16(55.2) | 5(17.2) | 8(27.6) |

| Receptive | |||||||||

| Placebo | 12(41.4 | 8(27.6 | 9(31.0) | 14(48.3) | 5(17.2) | 10(34.5) | 17(58.6) | 5(17.2) | 7(24.1) |

| AUCB | 13(44.8) | 5(17.2) | 11(37.9) | 17(58.6) | 2(6.9) | 10(34.5) | 18(62.1) | 3(10.3) | 8(27.6) |

| Social | |||||||||

| Placebo | 12(41.4) | 9(31.0) | 8(27.6) | 14(48.3) | 3(10.3 | 12(41.4 | 16(55.2) | 2(6.9) | 11(37.9) |

| AUCB | 13(44.8) | 6(20.7) | 10(34.5) | 16(55.2) | 1(3.4) | 12(41.4) | 18(62.1) | 3(10.3) | 8(27.6) |

Abbreviation: AUCB, autologous umbilical cord blood

Primary and Secondary Endpoints

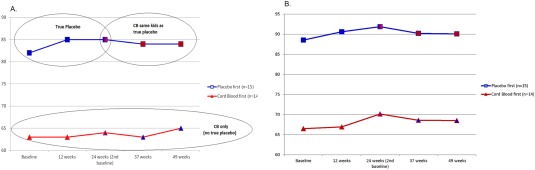

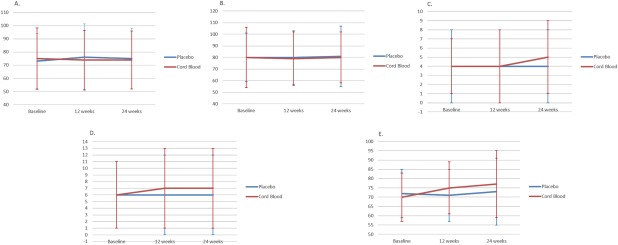

Figure 2A (EOWPVT) and 2B (ROWPVT) show the means for each group throughout their time in the study. Figure 3A through 3E display the means for the EOWPVT (Panel A), ROWPVT (Panel B) Stanford‐Binet Knowledge (Panel C), Stanford‐Binet Fluid Reasoning (Panel D), and Vineland Socialization (Panel E) over the study for all 29 subjects under both conditions. There were no statistically significant carryover effects for these endpoints. This allowed participants to be used as their own control and mean differences for all 29 subjects compared after infusions of AUCB and placebo at 12 and 24 weeks versus baseline.

Figure 2.

Mean Expressive One Word Picture Vocabulary Test (A) and Receptive One Word Picture Vocabulary Test (B) for all subjects over the entire study period. The crossover occurred at 24 weeks. Abbreviation: CB, cord blood.

Figure 3.

Mean Expressive One Word Picture Vocabulary Test (A), Receptive One Word Picture Vocabulary Test (B), Stanford Binet‐Knowledge (C), and Stanford Binet Fluid Reasoning subscales (D) and Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale for Socialization (E) at baseline, 12 weeks, and 24 weeks for all 29 subjects under each condition. Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale for Socialization: F 1,27 = 5.08; p = .032 (false discovery rate [FDR] adjusted p‐value = .025) after 12 weeks; F 1,27 =1.95; p = .174 (FDR adjusted p‐value = .045) after 24 weeks.

There were no statistically significant changes in the EOWPVT (Fig. 3A), ROWPVT (Fig. 3B), or Stanford Binet subscales (Fig. 3C, 3D) when subjects received placebo versus AUCB at 12 and 24 weeks post infusion. The score on the Vineland Socialization subscale was significant as scored per guidelines after 12 weeks for the AUCB group, but after applying the false discovery method for adjustment of multiple comparisons the scoring did not reach significance (Fig. 3E).

There were statistically significant (p < .05) group X treatment interactions for the Vineland ABC, Communication, Motor, and Daily subscales which indicated that changes over time between these scores depended on the order that AUCB was administered. For these endpoints, the means scores between the 14 participants who received AUCB first and 15 participants who received placebo first were compared at 12 and 24 weeks and adjusted for differences in baseline scores. The results of these ANCOVAs (Table 4) showed that all Vineland subscales had lower mean scores for the AUCB group than the placebo group at both 12 and 24 weeks. None of these differences were statistically significant after adjustment for baseline scores and using the FDR adjustment for multiplicity.

Table 4.

Results of analysis of covariance comparing 12‐ and 24‐week placebo and autologous umbilical cord blood (AUBC) scores when adjusted for baseline scores for Vineland subscales with a statistically significant order by treatment interaction. Means ± standard deviations (SD) represent the 15 cases receiving placebo first and the 14 cases receiving AUCB first

| Baseline Mean ± SD | 12 weeks Mean ± SD | p‐value | FDR adjusted p‐value | 24 weeks Mean ± SD | p‐value | FDR adjusted p‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABC | |||||||

| Placebo | 74.27 ± 16.00 | 74.93 ± 12.40 | .025 | .015 | 75.00 ± 11.60 | .015 | .005 |

| Cord blood | 66.00 ± 12.20 | 66.15 ± 15.05 | 67.57 ± 16.52 | ||||

| Communication | |||||||

| Placebo | 79.60 ± 17.18 | 81.47 ± 14.63 | .045 | .035 | 83.33 ± 15.46 | .044 | .030 |

| Cord blood | 66.00 ± 15.56 | 67.79 ± 16.21 | 68.00 ± 18.82 | ||||

| Motor | |||||||

| Placebo | 77.67 ± 13.57 | 79.57 ± 11.51 | .029 | .020 | 76.67 ± 7.61 | .022 | .010 |

| Cord blood | 73.86 ± 13.17 | 73.50 ± 15.09 | 69.71 ± 15.10 | ||||

| Daily | |||||||

| Placebo | 77.13 ± 16.61 | 78.13 ± 14.21 | .203 | .050 | 77.33 ± 15.30 | .097 | .040 |

| Cord blood | 68.14 ± 15.55 | 68.13 ± 15.32 | 70.36 ± 17.73 |

Abbreviation: FDR, false discovery rate.

Discussion

This pilot study is the first randomized, double‐blinded, placebo‐controlled trial performed in the U.S. to assess the feasibility of treating children with ASD with AUCB. The results of this study showed that AUCB infusions are safe for this population. There were no reported serious adverse events, similar to other studies of AUCB infusions 39, 40, 41, 47. There were also no statistically significant differences between scores on the two primary or secondary endpoints after infusion with AUCB versus infusion of placebo.

The present study provides further evidence that treatment with AUCB is safe but there was minimal evidence of clinical effectiveness. Although the lack of significant results of this study are in contrast to the findings of an open‐label trial conducted by Dawson et al. 47 who reported improvements in behavior on parent reports of social communication skills, clinician ratings of autism symptoms, and standardized measures of expressive vocabulary in children with ASD after the infusion of AUCB, parents and investigators observed similar subjective improvements. While those findings show promise for AUCB as a potential treatment for ASD, the lack of both blinding and a control group do not allow for definitive conclusions. Both studies assessed change from baseline at 12 and 24 weeks and used some similar endpoints. However, the present study incorporated both blinding and a placebo treatment to minimize the potential for a placebo effect that may occur in open label studies and used standard scores for both objective and subjective endpoints. While raw scores may show more variation, standard scores reflect what is appropriate for children of a specific age and allow conversion of raw scores into meaningful expression of performance relative to age expectations.

Language testing in the ASD population is difficult due to often atypical developmental course. Use of raw scores or use of language tests other than the EOWPVT and ROWPVT could have potentially resulted in more precise measurement of function in these areas, specifying gain, stability, or loss. For example, with the current measures, standard scores above the 95th percentile limit the capture of gains in post‐treatment scores (ceiling effect). This, however, was not contributing factor in the current analysis. Standard scores below the 2nd percentile occurred frequently in this investigation and potentially limit capture of function (loss, stability, minor improvements) as well. While there is little room to measure loss, even opportunity for growth can be misleading. For example, stability in raw scores in each scenario (no loss of skill) could result in decreased standard score even with a 3‐month advance in age. In fact, minor improvements could translate into stability or decrease in standard scores upon conversion if the rate of growth is less than anticipated by the standardized data for demographic age‐expectations. This also pertains to a lesser degree to the Vineland and the Stanford‐Binet tests. The subjective measurement of CGI is commonly used in studies of ASD in part due to these challenges. Although not to be interpreted in isolation, the measurable change in CGI scores may be more meaningful than standardized scores.

In addition to the difficulty in measuring language in this population, there are other aspects of the present investigation that could have limited the ability to detect significant findings. These include a crossover design and lack of standardization of AUCB dose.

The study was designed as a crossover study. Repeated measures designs allow for greater power with fewer subjects than parallel groups trials. One reason for the choice of the crossover design was that there are few treatments for ASD so parents would be less likely to want to enroll children in a trial with a chance of only receiving a placebo, or in a trial with a wait list option where subjects randomized to placebo could potentially be aged out of the trial while waiting to be given AUCB. The design choice resulted in excellent compliance by parents so that complete data were available for all visits, on all endpoints, for 29 subjects. The disadvantage of this design is the potential for carryover of a treatment which means that only the first sequence of treatments can be used for analysis. The present study showed no carryover effect for the two primary endpoints but there were carryover effects for several secondary endpoints. There is the potential that 12 weeks was not a sufficient amount of time to detect potential changes. However, Figure 2A and 2B, which show the change over time for the 14 participants who received AUCB first and were followed for the full 24 weeks, suggest that this is likely not the reason for lack of effect.

The other reason for the choice of the crossover design is that it allows for subjects to serve as their own control. The ASD population has widely variable levels of functioning and this was seen in the baseline differences in the endpoint scores between the groups who received AUCB first versus those who received placebo first. This is a potential problem in all randomized studies of autism and was one of the advantages of the crossover design where subjects are used as their own control. Perhaps stricter control on the level of initial baseline function required for study inclusion would have led to less variability among subjects and increased the ability for differences to be detected and is suggested for a future investigation. The advantage of strict inclusion criteria is better control and less variability but the disadvantage is that the results become generalizable to a smaller subset of the ASD population.

Dosage of AUCB may be a reason for lack of evidence of efficacy. Although all samples met the minimum requirement of a post thaw percent viable CD34+ of 20%, participants varied widely in percentage and number of CD34+ cells in samples infused. Furthermore, 27% of participants received 1/5th of their available AUCB based on parental choice to only use the minor compartment. Parents were reticent to use the entire banked sample on an investigational treatment but an analysis of dose response would be valuable in future studies.

Despite the limitations of the study, a core symptom of autism, socialization, showed trends in improvement on the Socialization Subscale of the Vineland. The strengths of this study were successful maintenance of blinding and excellent compliance by parents attending all follow up visits despite some having to travel long distances over several months.

We recognize that our results do not corroborate with the results of Dawson et al. 47. Such discrepant results between investigations of comparable design warrant careful consideration of the variables that potentially contributed to outcomes. Specific attention should be given to blind versus open designs. Lack of significant measurable benefit was observed only in the blinded scenario while significant change of any kind was observed only in the open scenario. There may be significant potential benefit, even if it occurs within a sub‐population of the larger ASD phenotype. As we begin to explore possible benefits from these new technologies we would benefit from not taking a position of controversy, but rather of collaboration and appreciation that these two investigations were vastly different studies. Dawson et al. 47 may well have discovered something that we missed, but any future studies should consider implementing a blinded investigation with a control group. We might also lack, at this time, tools that effectively capture real change in this population. Measurement of behavior is inherently more subjective than biometrics.

The goal of this pilot study was to assess safety and design the first U.S. based study of AUCB for treatment of ASD. This study demonstrates that infusion of AUCB in individuals with ASD is safe and feasible when studied in a rigorous trial design and revealed challenges that need to be addressed to advance the study of the AUCB.

Conclusion

Infusion of AUCB for children with ASD is safe but efficacy has yet to be determined. Tightly controlled trials are necessary to further progress the study of AUCB for autism.

Author Contributions

M.C.: conception and design, collection of data, manuscript writing, final approval of manuscript; C.L.: conception and design, collection of data, final approval of manuscript; C.P.: conception and design, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, final approval of manuscript; A.D.‐C.: collection of data; A.H.: data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing; M.C.: conception and design, collection of data.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

M.C. has received consulting and speaking fees from CBR Systems, Inc, the source of funding of the research grant. The other authors indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

This study was funded by CBR Systems, Inc.

References

- 1. Baio J. Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years‐Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2010. MMWR Surveillance Summary 2014, 2014. [PubMed]

- 2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

- 3. Onore C, Careaga M, Ashwood P. The role of immune dysfunction in the pathophysiology of autism. Brain, Behav Immun 2012;26:383–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Grabrucker AM. Environmental factors in autism. Front Psychiatry 2012;3:118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schaefer G. Clinical genetic aspects of ASD spectrum disorder. Int J Mol Sci 2016;17:1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Colvert E, Tick B, McEwen F et al. Heritability of autism spectrum disorder in a UK population‐based twin sample. JAMA psychiatry 2015;72:415–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tick B, Bolton P, Happe F et al. Heritability of autism spectrum disorders: A meta‐analysis of twin studies. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2016;57:585–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chez MG, Guido‐Estrada N. Immune therapy in autism: Historical experience and future directions with immunomodulatory therapy. Neurotherapeutics 2010;7:293–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vargas DL, Nascimbene C, Krishnan C et al. Neuroglial activation and neuroinflammation in the brain of patients with autism. Ann Neurol 2005;57:67–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Morgan JT, Chana G, Abramson I et al. Abnormal microglial‐neuronal spatial organization in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in autism. Brain Res 2012;1456:72–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Louveau A, Smirnov I, Keyes TJ et al. Structural and functional features of central nervous system lymphatic vessels. Nature 2015;523:337–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ransohoff RM, Engelhardt B. The anatomical and cellular basis of immune surveillance in the central nervous system. Nat Rev Immunol 2012;12:623–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shechter R, London A, Schwartz M. Orchestrated leukocyte recruitment to immune‐privileged sites: Absolute barriers versus educational gates. Nat Rev Immunol 2013;13:206–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bauman MD, Schumann CM. Is ‘bench‐to‐bedside' realistic for autism? An integrative neuroscience approach. Neuropsychiatry 2013;3:159–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stubbs EG, Crawford ML. Depressed lymphocyte responsiveness in autistic children. J Autism Child Schizophr 1977;7:49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Todd RD, Hickok JM, Anderson GM et al. Antibrain antibodies in infantile autism. Biol Psychiatry 1988;23:644–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Connolly AM, Chez MG, Pestronk A et al. Serum autoantibodies to brain in Landau‐Kleffner variant, autism, and other neurologic disorders. J Pediatr 1999;134:607–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pardo CA, Vargas DL, Zimmerman AW. Immunity, neuroglia and neuroinflammation in autism. Int Rev Psychiatry 2005;17:485–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chez MG, Dowling T, Patel PB et al. Elevation of tumor necrosis factor‐alpha in cerebrospinal fluid of autistic children. Pediatr Neurol 2007;36:361–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zimmerman AW, Connors SL, Matteson KJ et al. Maternal antibrain antibodies in autism. Brain Behav Immun 2007;21:351–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhang Y, Xu Q, Liu J et al. Risk factors for autistic regression: Results of an ambispective cohort study. J Child Neurol 2012;27:975–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kleinhans NM, Reiter MA, Neuhaus E et al. Subregional differences in intrinsic amygdala hyperconnectivity and hypoconnectivity in autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res 2016;9:760–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Plioplys AV, Greaves A, Kazemi K et al. Lymphocyte function in autism and Rett syndrome. Neuropsychobiology 1994;29:12–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gupta S, Aggarwal S, Heads C. Dysregulated immune system in children with autism: Beneficial effects of intravenous immune globulin on autistic characteristics. J Autism Dev Disord 1996;26:439–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chez MG, Buchanan C, Loeffel MF. Practical treatment with pulse‐dose corticosteroids in pervasive developmental disorder or autistic patients with abnormal sleep EEG and language delay. In: Perat M, ed. New Developments in Child Neurology. Bologna, Italy: Monduzzi Editore, 1998:695–698.

- 26. Shenoy S, Arnold S, Chatila T. Response to steroid therapy in autism secondary to autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome. J Pediatr 2000;136:682–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chez M, Low R, Donnel T et al. Effect of lenalidomide on TNF‐alpha elevation and behavior in autism. Paper presented at: International Meeting for Autism Research; May 20–22, 2010; Philadelphia, PA.

- 28. Peterson DA. Umbilical cord blood cells and brain stroke injury: Bringing in fresh blood to address an old problem. J Clin Invest 2004;114:312–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Newman MB, Willing AE, Manresa JJ et al. Cytokines produced by cultured human umbilical cord blood (HUCB) cells: Implications for brain repair. Exp Neurol 2006;199:201–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sun JM, Kurtzberg J. Cord blood for brain injury. Cytotherapy 2015;17:775–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lv YT, Zhang Y, Liu M et al. Transplantation of human cord blood mononuclear cells and umbilical cord‐derived mesenchymal stem cells in autism. J Transl Med 2013;11:196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Taguchi A, Soma T, Tanaka H et al. Administration of CD34+ cells after stroke enhances neurogenesis via angiogenesis in a mouse model. J Clin Invest 2004;114:330–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Meier C, Middelanis J, Wasielewski B et al. Spastic paresis after perinatal brain damage in rats is reduced by human cord blood mononuclear cells. Pediatr Res 2006;59:244–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Drobyshevsky A, Cotten CM, Shi Z et al. Human umbilical cord blood cells ameliorate motor deficits in rabbits in a cerebral palsy model. Dev Neurosci 2015;37:349–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Baraniak PR, McDevitt TC. Stem cell paracrine actions and tissue regeneration. Regen Med 2010;5:121–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Butler MG, Menitove JE. Umbilical cord blood banking: An update. J Assist Reprod Genet 2011;28:669–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ballen KK, Gluckman E, Broxmeyer HE. Umbilical cord blood transplantation: The first 25 years and beyond. Blood 2013;122:491–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Munoz J, Shah N, Rezvani K et al. Concise review: umbilical cord blood transplantation: past, present, and future. Stem Cells Translational Medicine 2014;3:1435–1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cotten CM, Murtha AP, Goldberg RN et al. Feasibility of autologous cord blood cells for infants with hypoxic‐ischemic encephalopathy. J Pediatr 2014;164:973–979. e971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sun JM, Grant GA, McLaughlin C et al. Repeated autologous umbilical cord blood infusions are feasible and had no acute safety issues in young babies with congenital hydrocephalus. Pediatr Res 2015;78:712–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sun J, Allison J, McLaughlin C et al. Differences in quality between privately and publicly banked umbilical cord blood units: A pilot study of autologous cord blood infusion in children with acquired neurologic disorders. Transfusion 2010;50:1980–1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Novak I, Walker K, Hunt RW et al. Concise review: Stem cell interventions for people with cerebral palsy: Systematic review with meta‐analysis. Stem Cells Translational Medicine 2016;5:1014–1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Patterson P. Pregnancy, immunity, schizophrenia, and autism. Eng Sci 2006;69:10–21. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ray-Subramanian CE, Nan H, Ellis-Weismer E. J Autism Dev Disord. 2011;41:679–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Julious SA. Sample sizes for clinical trials with normal data. Stat Med 2004;23:1921–1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B Methodol 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dawson G, Sun JM, Davlantis KS et al. Autologous cord blood infusions are safe and feasible in young children with autism spectrum disorder: Results of a single‐center phase I open‐label trial. Stem Cells Translational Medicine 2017;6:1332–1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]