Abstract

We describe the first case of Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) occurring 8 days after the first dose of a three‐dose rabies vaccination series. She had no history of vaccine‐related rash or other adverse drug reactions, nor had she received any other drug therapy. The temporal relationship between the development of SJS and the vaccination suggests that the rabies vaccination probably was the causal agent. This case serves as a warning of a distinct cutaneous reaction of rabies vaccination.

Keywords: primary hamster kidney vaccine, rabies vaccination, Stevens–Johnson syndrome

Rabies is an acute viral zoonosis that causes fatal encephalomyelitis, usually after the bite from an infected mammal 1. Timely and appropriate administration of modern rabies vaccines is a crucial method to prevent rabies virus infection post‐exposure. Common adverse effects of rabies vaccines include abdominal pain, headache, dizziness, fever, urticaria, gastrointestinal symptoms and anaphylaxis 2. Post‐marketing data have reported two cases of erythema multiforme in patients receiving immunization with rabies vaccines 3. Verma also described a case of rabies vaccine‐induced erythema multiforme in a 10‐year‐old boy 4. However, no formal report of Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) associated with rabies vaccines has ever been published. Here, we report a patient who developed SJS after exposure to the rabies vaccines.

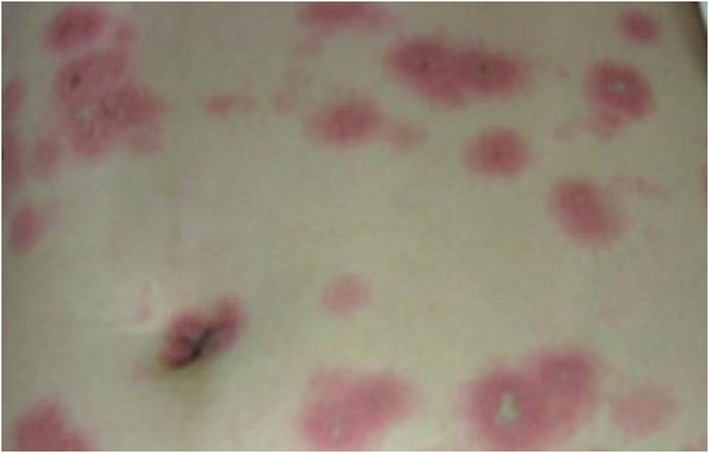

The case was a previously healthy 22‐year‐old woman, who received minor scratches, without bleeding (category II wound) following dog bite on left leg (day 0). She received three intramuscular injections of primary hamster kidney vaccine (PHKV) (Rabies Vaccine For Human Use; Zhong Ke Biopharm Co., Ltd, China) on days 0, 3 and 7. On the 8th day, rashes began to appear on her eyelid. On the 9th day, she had an erythematous rash over her face and chest, and her temperature reached 37.6°C. On the 11th day post‐operation, she had an elevation of temperature reached 38.8°C and the fever was persistent. More rashes, similar to herpes erosions, successively appeared on her torso, which spread to all four limbs (Figure 1). At night, she developed severe breathlessness and was unable to speak. Immediately, she was rushed to the emergency room. The patient denied any recent upper respiratory infection, febrile illness or a history of herpes simplex virus. She took no long‐term drug therapy and denied receiving any other recent vaccination or previous vaccine‐related rash or other adverse reactions. Her blood pressure was 80/60 mm Hg, and the heart rate was 98 beats/min. Blood tests revealed an elevated white blood cell counts (WBC) of 15.51 × 109 L−1 and an elevated neutrophil cells of 87.2%. Culture and serological tests were negative for bacteria, HIV and hepatitis A, B and C virus. Infectious diseases were excluded by whole‐body computed tomography and blood, urine and sputum cultures.

Figure 1.

Clinical picture on day 11 after administration of rabies vaccine

As her illness progressed, the rashes and erosions appeared on the mucous membranes of her vulva and anal. She was then diagnosed with Stevens–Johnson syndrome by dermatologist, which may have been caused by rabies vaccine. The appearance of erythematous maculopapular rash with a plausible time relationship to rabies vaccination, together with the absence of any other concurrent disease or risk factor, including drugs assumption and chemicals exposure, suggested an ‘indeterminate’ causality relationship with the administration of vaccine according to WHO causality assessment criteria for adverse events following immunization 5. Her ALDEN adverse drug reaction probability scale was 2, indicating a ‘probable link’. So prednisone (30 mg/day) and loratadine (10 mg/day) were prescribed as well as membrane and skin care was enhanced to avoid secondary infections.

On the 13th day, her body temperature returned to normal and no new rashes appeared, leaving behind hyperpigmentation. Laboratory tests showed the following: WBC 8.56 × 109 L−1; neutrophil cells 56.5%. The rest of her stay became normal. She continued to take prednisone and loratadine until discharged from the hospital on the 15th day. Although serious mucocutaneous reactions are rare during and after the administration of rabies vaccines, such reactions pose a serious dilemma for the patient and she refused consent for rechallenge with the vaccine. No recurrence was seen during a follow‐up of 3 months, after which the patient was lost to follow‐up.

Cutaneous drug eruptions are one of the most frequent manifestation of adverse drug reactions and can affect 2–3% of hospitalized patients 6. Among these, SJS is a rare, life‐threatening blistering mucocutaneous disease 7. The annual incidence of SJS is estimated to 1.1–7.7 cases per 1 million. It is considered that the syndrome is closely related to the application of antiepileptic drugs, such as carbamazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, oxcarbazepine, lamotrigine and other aromatic drugs 8. However, SJS caused by rabies vaccines has not, to our knowledge, been described.

PHKV was used widely throughout China and Russia, which uses the fixed Beijing strain cultured in primary hamster kidney cells 9. Nowadays, rabies vaccines are known as pure, potent, safe and efficacious biologics 10, but our patient had erythematous maculopapular rash involvement 8 days after immunization with PHKV. The risk of SJS is highest in the first week after drug administration, and faster reaction may probably occur in sensitized patients who have had previous milder cutaneous eruptions 8. During these 8 days, our patient took no other medicine except for PHKV. This time sequence fits well with her history, so it is believed that the cutaneous and systemic signs and symptoms in this patient represented SJS due to PHKV. The delayed hypersensitivity mechanism directed by drug‐specific T cells is probably the most important mechanism in SJS, but the physiological mechanisms of SJS are not well established yet 11, 12.

Although serious systemic, anaphylactic or neuroparalytic reactions after the administration of outdated nerve tissue vaccines have been well established 13, rabies biologics differ from one another in terms of types of adverse reactions. Despite the same origins of the vaccines, side effects may vary due to the manufacturer. Meanwhile, other ingredients may also be responsible for the serious adverse reactions, such as preservatives, stabilizers, culture media, active immunizing antigens and antimicrobial agents 14.

In the present report, we describe the first case of SJS that was caused by rabies vaccines, suggesting that clinicians should be vigilant of the possibility of SJS occurrence during applications.

Competing Interests

There are no competing interests to declare.

Ma, L. , Du, X. , Dong, Y. , Peng, L. , Han, X. , Lyu, J. , and Bai, H. (2018) First case of Stevens–Johnson syndrome after rabies vaccination. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 84: 803–805. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13512.

References

- 1. Hudson EG, Brookes VJ, Ward MP. Assessing the risk of a canine rabies incursion in Northern Australia. Front Vet Sci 2017; 4: 141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Peng J, Lu S, Zhu Z, Zhang M, Hu Q, Fang Y. Safety comparison of four types of rabies vaccines in patients with WHO category II animal exposure: an observation based on different age groups. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016; 95: e5049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. WHO . WHO pharmaceuticals newsletter [EB/OL]. (2015. –2005). Available at http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/255491/1/WPN‐2016‐05‐eng.pdf (last accessed May 2016).

- 4. Verma P. Erythema multiforme possibly triggered by rabies vaccine in a 10‐year‐old boy. Pediatr Dermatol 2013; 30: 297–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. WHO . Causality assessment of an adverse event following immunization (AEFI) [EB/OL]. (2013. –03). Available at http://www.who.int/vaccine_safety/publications/aefi_aide_memoire/en/ (last accessed March 2013).

- 6. Hoetzenecker W, Nägeli M, Mehra ET, Jensen AN, Saulite I, Schmid‐Grendelmeier P, et al Adverse cutaneous drug eruptions: current understanding. Semin Immunopathol 2016; 38: 75–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Goldblatt C, Khumra S, Booth J, Urbancic K, Grayson ML, Trubiano JA. Poor reporting and documentation in drug‐associated Stevens‐Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis—lessons for medication safety. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2017; 83: 224–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Letko E, Papaliodis DN, Papaliodis GN, Daoud YJ, Ahmed AR, Foster CS. Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a review of the literature. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2005; 94: 419–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wu T, Lu Y, Ge X. A study on efficacy of rabies vaccine prepared by primary hamster kidney cells in Guangxi. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi 1998; 32: 211–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rupprecht CE, Nagarajan T, Ertl H. Current status and development of vaccines and other biologics for human rabies prevention. Expert Rev Vaccines 2016; 15: 731–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jao T, Tsai TH, Jeng JS. Aggrenox (Asasantin retard)‐induced Stevens–Johnson syndrome. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2009; 67: 264–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Greenberger PA. Drug allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006; 117: S464–S470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Giesen A, Gniel D, Malerczyk C. 30 years of rabies vaccination with Rabipur: a summary of clinical data and global experience. Expert Rev Vaccines 2015; 14: 351–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chung EH. Vaccine allergies. Clin Exp Vaccine Res 2014; 3: 50–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]