Abstract

Background

Suicide is a leading cause of death and a complex clinical outcome. Here we summarize the current state of research pertaining to suicidal thoughts and behaviours in youth. We review their definitions/measurement and phenomenology, epidemiology, potential etiological mechanisms, and psychological treatment and prevention efforts.

Results

We identify key patterns and gaps in knowledge that should guide future work. Regarding epidemiology, the prevalence of suicidal thoughts and behaviours among youth varies across countries and sociodemographic populations. Despite this, studies are rarely conducted cross-nationally and do not uniformly account for high-risk populations. Regarding etiology, the majority of risk factors have been identified within the realm of environmental and psychological factors (notably negative affect-related processes), and most frequently using self-report measures. Little research has spanned across additional units of analyses including behaviour, physiology, molecules, cells, and genes. Finally, there has been growing evidence in support of select psychotherapeutic treatment and prevention strategies, and preliminary evidence for technology-based interventions.

Conclusions

There is much work to be done to better understand suicidal thoughts and behaviours among youth. We strongly encourage future research to: (1) continue improving the conceptualization and operationalization of suicidal thoughts and behaviours; (2) improve etiological understanding by focusing on individual (preferably malleable) mechanisms; (3) improve etiological understanding also by integrating findings across multiple units of analyses and developing short-term prediction models; (4) demonstrate greater developmental sensitivity overall; and (5) account for diverse high-risk populations via sampling and reporting of sample characteristics. These serve as initial steps to improve the scientific approach, knowledge base, and ultimately prevention of suicidal thoughts and behaviours among youth.

Keywords: Suicide, risk factors, correlates, treatment, prevention

Introduction

Each year, approximately 800,000 people die by suicide worldwide (WHO, 2017). Whereas suicide is a leading cause of death across all age groups, suicidal thoughts and behaviours among youth warrant particular concern for several reasons. First, the sharpest increase in the number of suicide deaths throughout the lifespan occurs between early adolescence and young adulthood (Nock et al., 2008a; WHO, 2017). Second, suicide ranks higher as a cause of death during youth compared to other age groups. It is the second leading cause of death during childhood and adolescence, whereas it is the tenth leading cause of death among all age groups (CDC, 2017). Third, many people who have ever considered or attempted suicide in their life first did so during their youth, as the lifetime age of onset for suicidal ideation and suicide attempt typically occurs before the mid-20s (Kessler, Borges, & Walters, 1999). Finally, suicide death is preventable, with adolescence presenting a key prevention opportunity resulting in many more years of life potentially saved. By gaining a better understanding of how and why suicide risk emerges during youth, we can offer opportunities to intervene on this trajectory earlier in life.

Here we will review the current state of the literature on suicidal thoughts and behaviours among youth. Suicidal thoughts and behaviours include suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, and suicide death. We begin by defining and describing each of these outcomes, and then summarize their known epidemiology, mechanisms, and related treatment and prevention efforts. Importantly, the literature on suicidal thoughts and behaviours is vast yet still in its nascent form. We will conclude the review by outlining limitations and caveats, with corresponding recommendations for future research.

Definitions and phenomenology

This review uses the following definitions of suicidal thoughts and behaviours. Suicidal ideation is the consideration of or desire to end one’s own life. Suicidal ideation typically ranges from relatively passive ideation (e.g., wanting to be dead) to active ideation (e.g., wanting to kill oneself or thinking of a specific method on how to do it). Studies using self-report measures and real-time monitoring techniques have demonstrated that community-based adolescents who experience suicidal ideation typically do so at a moderate frequency (e.g., 1 thought per week), with thoughts often ranging between mild to moderate in severity (Miranda, Ortin, Scott, & Shaffer, 2014; Nock, Prinstein, & Sterba, 2009).

Suicide attempt is an action intended to deliberately end one’s own life. The most common method among youth is typically overdose or ingestion, followed by hanging/suffocation and the use of a sharp object (e.g., cutting; Cloutier, Martin, Kennedy, Nixon, & Muehlenkamp, 2010; Parellada et al., 2008). Suicide attempt among adolescents often occurs in the context of a plan, though a substantial minority of adolescents (20–40%) attempt suicide in the absence of a plan (Nock et al., 2008b; Witte et al., 2008).

Suicide death is a fatal action to deliberately end one’s own life, as frequently determined by a medical examiner, coroner, or proxy informant. The most common methods among youth are hanging/suffocation, overdose or ingestion, and firearm (Beautrais, 2003; CDC, 2017; Li, Phillips, Zhang, Xu, & Yang, 2008). There are some distinct patterns across geographical regions, likely associated with variable access to lethal means (Colucci & Martin, 2007). Suicide death by jumping in front of a moving object (e.g., trains), for instance, is more common among adolescents in countries with highly developed railway systems (e.g., Belgium, Germany, Netherlands, Switzerland; Hepp, Stulz, Unger-Koppel, & Ajdacic-Gross, 2012). In contrast to the common practice of suicide by pesticide ingestion in more rural China, metropolitan regions such as Hong Kong and Singapore observes less pesticide ingestion and more medication ingestion and jumping from heights (Kolves & de Leo, 2017; Wai, Hong, & Heok, 1999).

For the purpose of this review, we exclude self-injurious actions in the absence of suicidal intent (e.g., non-suicidal self-injury, suicide gesture). While there is frequent co-occurrence and association between non-suicidal and suicidal thoughts and behaviours among youth, non-suicidal and suicidal thoughts and behaviours remain phenomenologically distinct. Of note, the term deliberate self-harm is sometimes used to describe self-injurious acts without assuming suicidal intent, as individuals may have instead had intent to escape rather than end one’s life (Kreitman, 1977; Skegg, 2005). Because these terms describe behaviours that may be in the absence of suicidal intent, they remain outside the scope of the present review. Finally, we also exclude suicide plans due to the lack of standard definition and the documented inconsistency of individuals reporting planned versus unplanned attempts (Conner, 2004; Millner, Lee, & Nock, 2015; Wyder & De Leo, 2007).

Epidemiology

Below we summarize the known prevalence, onset, and course of suicidal thoughts and behaviours, as well as patterns observed across specific demographic populations of youth. Much of what is known about suicidal thoughts and behaviours among youth around the world draws from individual country-level studies. Whenever possible, data from the World Health Organization (WHO) and cross-national studies are featured.

Prevalence

Prevalence rates for suicidal ideation range between 19.8% and 24.0% among youth (Nock et al., 2008b). Suicide attempt is less widespread, with lifetime prevalence rates between 3.1% and 8.8% (Nock et al., 2008b). This is largely aligned with other cross-national studies (e.g., Kokkevi, Rotsika, Arapaki, & Richardson, 2012).

Suicide death accounts for 8.5% of all deaths among adolescents and young adults around the world (15–29 years), and is a leading cause of death among youth worldwide (WHO, 2017). Suicide death rates are strikingly elevated in post-Soviet countries (e.g., Lithuania, Latvia, Uzbekistan), with rates ranging from 14.5–24.3 per 100,000 for adolescents and young adults, and 0.3–2.8 per 100,000 for children and young adolescents (Table 1). Additional countries with elevated suicide rates among youth include New Zealand, Finland, and Japan. Of note, trends among youth do not uniformly represent trends overall. For instance, New Zealand ranks high compared to other countries according to its youth suicide rates (i.e., across ages 5–29, #2), but has a relatively low suicide rate overall (i.e., across all age groups; #22). As another example, Hungary ranks high compared to other countries according to its overall suicide rate (#4) but has a relatively low youth suicide rate (#23). Countries such as Lithuania and Latvia rank high for both youth and overall suicide rates.1

Table 1.

Youth suicide rates per 100,000 persons in selected countries by age

| Year | 5–14 years | 15–29 years* | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Lithuania | 2015 | 1.3 | 24.3 |

| New Zealand | 2012 | 1.4 | 20.7 |

| Finland | 2014 | 0.2 | 17.7 |

| Japan | 2014 | 0.8 | 15.8 |

| Latvia | 2014 | 0.3 | 15.5 |

| Uzbekistan | 2014 | 2.8 | 14.5 |

| Sweden | 2015 | 0.8 | 13.3 |

| Iceland | 2015 | - | 13.1 |

| United States of America | 2014 | 1.0 | 13.0 |

| Ireland | 2013 | 0.3 | 13.0 |

| Republic of Korea | 2013 | 0.8 | 12.9 |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 2010 | 1.1 | 12.7 |

| Mauritius | 2014 | 1.6 | 12.6 |

| Belgium | 2013 | 0.4 | 12.4 |

| Estonia | 2014 | 1.5 | 12.3 |

| Canada | 2012 | 0.8 | 11.0 |

| Chile | 2014 | 1.1 | 10.3 |

| Australia | 2014 | 0.7 | 10.2 |

| Colombia | 2013 | 1.1 | 9.6 |

| Costa Rica | 2014 | 1.0 | 9.3 |

| Austria | 2014 | 0.4 | 9.2 |

| Norway | 2014 | 0.3 | 9.2 |

| Hungary | 2014 | 0.2 | 9.0 |

| Czech Republic | 2015 | 0.7 | 9.0 |

| Slovenia | 2015 | 0.5 | 8.8 |

| Switzerland | 2013 | 0.4 | 8.6 |

| Republic of Moldova | 2015 | 0.7 | 8.1 |

| Romania | 2015 | 0.7 | 7.6 |

| Netherlands | 2015 | 0.4 | 7.3 |

| Slovakia | 2014 | 0.1 | 7.2 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 2015 | 2.3 | 7.2 |

| Mexico | 2014 | 0.9 | 7.1 |

| Croatia | 2015 | 0.7 | 6.9 |

| Germany | 2014 | 0.3 | 6.7 |

| Cuba | 2014 | 0.8 | 6.1 |

| United Kingdom | 2014 | 0.2 | 6.0 |

| St Vincent & the Grenadines | 2015 | 1.2 | 4.9 |

| Denmark | 2014 | 0.2 | 4.8 |

| Israel | 2014 | 0.4 | 4.2 |

| Italy | 2012 | 0.1 | 3.8 |

| Luxembourg | 2014 | 0.8 | 3.8 |

| Spain | 2014 | 0.2 | 3.8 |

| Macedonia | 2013 | 0.3 | 3.6 |

| Malta | 2014 | 1.7 | 3.2 |

| Brunei Darussalam | 2014 | - | 1.7 |

| Bahamas | 2013 | - | 1.6 |

Note. Countries selected by availability of vital registration data. Dash (-) used to indicate missing data.

Rank-ordered by 15–29 suicide rates (All).

Source of data: World Health Organization (2017)

Onset and course

Suicidal ideation is rare before the age of 10 and its prevalence rapidly increases between 12 and 17 years of age (Nock, Borges, & Ono, 2012; Nock et al., 2013). Many adolescents continue to experience suicidal ideation even after hospitalization (Czyz & King, 2015; Wolff et al., 2017). Adolescents who experience suicidal ideation (vs. non-suicidal adolescents) are approximately 12 times more likely to have attempted suicide by the age of 30 (Reinherz, Tanner, Berger, Beardslee, & Fitzmaurice, 2006), and over one third of adolescents who experience suicidal ideation go on to attempt suicide (Nock et al., 2013). Suicidal ideation that is especially frequent, serious, and chronic is associated with suicide attempt (Miranda et al., 2014; Czyz & King, 2015; Wolff et al., 2017). Of those adolescents who do transition to attempt, the majority do so within 1–2 years of ideation onset (Glenn et al., 2017), and are typically characterized by specific clinical presentations (e.g., depression/dysthymia, eating disorder, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder, intermittent explosive disorder; Nock et al., 2013). As expected, suicide attempt has a slightly later age of onset than suicidal ideation. Suicide attempt is rare before the age of 12, and its prevalence increases during early to mid/late adolescence (Glenn et al., 2017; Nock et al., 2013), and stabilize in the early 20s (Goldston et al., 2015). Among clinical populations, most suicide attempts after late adolescence have been found to be reattempts, with the amount of time between reattempts decreasing with greater frequency (Goldston et al., 2015). Even though suicide death is less frequent among children, suicides at ages as young as 5–8 years have been documented (e.g., Bridge et al., 2015; Grøholt, Ekeberg, Wichstrøm, & Haldorsen, 1998). Suicide death becomes increasingly common by 15–19 years (Kolves & de Leo, 2017).

Demographic patterns

There are distinct demographic patterns in the presentation, prevalence, and course of suicidal thoughts and behaviours. Some of the most distinguishing demographic characteristics include sex, age, race/ethnicity, as well as sexual orientation and gender identity.

Sex

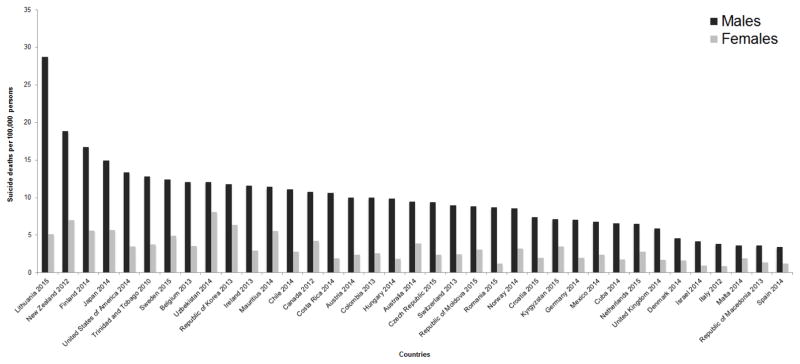

Sex presents a now well-established paradox in which adolescent girls are more likely to have experienced suicidal ideation and suicide attempt than boys, but adolescent boys are more likely to die by suicide (Brent, Baugher, Bridge, Chen, & Chiappetta, 1999; Fergusson, Woodward, & Horwood, 2000; Lewinsohn, Rhode, Seeley, & Baldwin, 2001; Kokkevi et al., 2012). There is no pronounced sex difference in prevalence or severity until approximately 11 years of age (Nock & Kazdin, 2002). Recent findings suggest slight differences in ages of onset (e.g., earlier age of onset for suicidal ideation among females, earlier age of onset for suicide attempt among males), though these patterns may vary across different levels of clinical severity (Glenn et al., 2017). There are mixed findings pertaining to the transition from adolescence into young adulthood, with some studies reporting more tempered sex differences (Lewinsohn et al., 2001) whereas others report persistent group differences (Fergusson et al., 2000). The sex difference in suicide death rates among youth tend to mimic those found among adults, such that boys and young men die by suicide at a rate of more than two times—and sometimes more than three times—that of girls and young women (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Youth suicide deaths by sex in selected countries (ages 5–29)

Note. Data were obtained from the World Health Organization for the most recent year available (2012–2015). Countries selected by availability of vital registration data by sex and age groups 5–14 and 15–29. The following countries were excluded due to missing data for any sex or age group: Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Iceland, Grenada, Brunei Darussalam, Bahamas, Latvia, Estonia, Slovenia, Slovakia, and Luxembourg.

Age

Older adolescents are more likely to die by suicide than children and younger adolescents (Brent et al., 1999; Grøholt et al., 1998). Typically across countries, suicide death rates for older adolescents and young adults (15–29 years) are at least ten times greater than children and young adolescents (5–14 years) (Table 1). This trend among older adolescents is at least somewhat attributed to greater prevalence of psychopathology such as substance abuse, and suicidal intent (Brent et al., 1999).2 Notable age patterns also exist in the use of methods. For instance, hanging/suffocation is more common among children compared to adolescents (Kolves & de Leo, 2017; Olfson et al., 2005; Sheftall et al., 2016), and the use of a sharp object is more common among adolescents compared to adults (Parellada et al., 2008). Adolescents and children who die by suicide, compared to adults, are less likely to have been intoxicated or to have made a previous suicide attempt (Grøholt et al., 1998).

Race/Ethnicity

The most consistent cross-national finding is the higher risk of suicide death among indigenous youth. This pattern has been observed throughout distinct parts of the world ranging from American Indian, Alaska Native, and Aboriginal youth in the United States and Canada (CDC, 2017; Mullany et al., 2009), to indigenous youth in Australia and New Zealand (Beautrais, 2001; Cantor & Neulinger, 2000), to Guaraní Kaiowá and Ñandeva communities in Brazil (Coloma, Hoffman, & Crosby, 2006). Substance use, poverty/unemployment, high accessibility to lethal means, intergenerational trauma, and loss of culture/identity have been cited as potential risk factors, and community/family connectedness and communication have been cited as potential protective factors (Borowsky, Resnick, Ireland, & Blum, 1999; Coloma et al., 1996; Wexler & Gone, 2012). Findings regarding other racial/ethnic minorities are nuanced and often specific to region, type of suicide-related outcome, and time. For instance, in the United States, Black Non-Hispanic adolescents are less likely to experience suicidal ideation compared to other adolescents (CDC, 2017; Nock et al., 2013), however there is a consistent trend of increasing suicide attempt and death rates over time among Black youth relative to same-aged White peers (Bridge et al., 2015; Joe & Kaplan, 2009; Shaffer, Gould, & Hicks, 1994), and higher death rates among Black children compared to Black adolescents (Sheftall et al., 2016). An additional and critical consideration is the local environment and whether this interacts with minority status. As an example, Swedish children were found to be at greater risk of suicide death if they had foreign-born parents and lived in an area deeming them to be a relative minority; in contrast, living in areas of Sweden where larger proportions of the population had foreign born parents protected against suicide risk (Zammit et al., 2014). Similar interactions between individual demographic characteristics and environment have been found in other countries such as England (Neeleman & Wesseley, 1999), and the United States as described below (Hatzenbuehler, 2011), and may help resolve inconsistent findings among other minority groups (e.g., Hispanic adolescents in the United States; South Asian adolescents in the United Kingdom; Bhui, McKenzie, & Rasul, 2007; CDC, 2017).

Sexual orientation and gender identity

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (LGBTQ) youth show elevated prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicide attempt than heterosexual youth (Fergusson, Horwood, & Beautrais, 1999; Wichstrøm, & Hegna, 2003; Haas et al., 2010). Related to the aforementioned point on race, the impact of sexual minority status may vary across social environments depending on degree of local LGB support. In a compelling example, Hatzenbuehler (2011) examined LGB youth across distinct counties within Oregon, USA and found that LGB youth were at 20% greater risk of attempting suicide if they lived in an “unsupportive county” (e.g., low proportion of registered Democrats, low presence of gay-straight alliances at school; low proportion of schools with anti-bullying and antidiscrimination policies specifically protecting LGB students) compared to supportive counties. Similarly, Raifman et al. (2017) recently demonstrated that same-sex marriage legislation at the state-level related to decreased rates of suicide among LGBQ youth in that respective state. The higher risk status of both sexual and gender minority youth (LGBT) may also be attributed to the consistently higher rates of victimization they experience both at home and school, relative to sexual nonminority youth (Friedman et al., 2011; D’Augelli, Grossman, & Starks, 2006; McGuire, Anderson, Toomey, & Russell, 2010). Increased attention on these higher risk populations is strongly encouraged.

Potential etiology: Risk factors and correlates

What is the pathway through which suicidal thoughts and behaviours develop? What confluence of unique factors lead youth to think about suicide and then act on their suicidal thoughts and attempt to end their lives? The short answer is that currently, we do not know as much as we need to know (Nock et al., 2009). In the absence of studies featuring experimental designs, the present section focuses on environmental, psychological, and biological factors that cannot automatically be assumed to play causal roles. Instead, we highlight correlates and risk factors, which are shown to be associated with suicidal thoughts and behaviours at the same time point (for the former term), or at a subsequent time point (for the latter term; Kraemer et al., 1997). These are distinct from causal risk factors, whose change at one time point precedes and corresponds with change in suicidal thoughts and behaviours. For these reasons, the current section pertains to potential (not actual) etiology.

Here we examine what is currently known about environmental, psychological, and biological risk factors and correlates of suicidal thoughts and behaviours. Particular attention is given to longitudinal studies, which are most appropriate for the identification of risk factors (Kraemer et al., 1997). Findings are largely organized by their degree of evidence, with those that have substantial amount of support through prospective studies and multivariate analyses qualifying as strong evidence (i.e., demonstrating a unique impact on subsequent suicidal thoughts and behaviours), and those largely supported by cross-sectional studies and/or bivariate associations qualifying as tentative or moderate evidence. Importantly, degree of evidence should not be equated with magnitude of effect, as ultimately all of these correlates and risk factors have fairly modest effects (Franklin et al., 2017).

Environmental risk factors and correlates

Below we discuss several environmental correlates and risk factors of suicidal thoughts and behaviours among youth. The strongest lines of evidence highlight the environmental risk factors of childhood maltreatment and bullying. There is mixed evidence around peer and media influence on suicide clusters. Relevant to these corresponding risk factors, there remains promising but tentative evidence pertaining to the timing of maltreatment early in life, non-traditional forms of peer victimization (i.e., cyber-bullying), and influence via the internet. These are each discussed below.

Childhood maltreatment

There is strong evidence indicating that various forms of childhood maltreatment such as sexual, physical, and emotional abuse predict future suicidal ideation and suicide attempt among youth. Prospective cohort studies and twin studies have demonstrated the unique impact of sexual abuse on suicide attempt and death among adolescents and young adults, independent of contextual factors such as parent and child characteristics and quality of family environment (e.g., Brown, Cohen, Johnson, & Smailes, 1999; Castellvi et al., 2017; Fergusson, Boden, & Horwood, 2008; Fergusson, Horwood, & Lynskey, 1996; Nelson et al., 2002). Sexual abuse has been shown to have longer-term effects than physical abuse (Fergusson et al., 2008), another potent risk factor for suicidal ideation and attempt (Dunn, McLaughlin, Slopen, Rosand, & Smoller, 2013; Gomez et al., 2017). Although less frequently studied, emotional abuse also has been shown to increase likelihood of suicidal ideation in older children and adolescents controlling for covariates such as history of suicidal ideation, depressive symptoms, and in some cases controlling for sexual and physical abuse (Gibb et al., 2001; Miller et al., 2016).

More recently, research has shifted toward identifying the temporal characteristics of maltreatment (i.e., onset of first exposure, occurrence of exposure during a specific developmental period) that are associated with suicidal thoughts and behaviours. There have been mixed findings regarding sensitive periods of maltreatment exposure, with some highlighting the impact of exposure during mid-adolescence (Khan et al., 2015), others underscoring exposure during preschool years and early childhood (Dunn et al., 2013; Khan et al., 2015), and finally some reporting no association at all (Gomez et al., 2017). Some of these factors may depend on sex or type of maltreatment (Khan et al., 2015). Of note, these individual studies largely rely on cross-sectional designs and/or retrospective recall of maltreatment.

Bullying

Strong evidence highlights bullying (i.e., peer victimization) as a risk factor for suicidal thoughts and behaviours among youth. Bullying consists of intentionally harmful or disturbing behaviour that is repeated, and invokes a power differential (Nansel et al., 2001). Longitudinal studies have demonstrated the impact of social exclusion, verbal/physical abuse, and coercion by peers during childhood and early adolescence on later suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, and suicide death (Kim, Leventhal, Koh, & Boyce, 2009; Goeffroy et al., 2016; Klomek et al., 2008; Klomek et al., 2009; Winsper, Lereya, Zanarini, Wolke, 2012). These associations largely hold up when controlling for depression and other psychiatric symptoms (Kim et al., 2009; Winsper et al., 2012), and are particularly robust for the impact of peer victimization on female adolescents (Klomek et al., 2009). Chronicity of victimization is a key consideration, as longer durations of exposure have been shown to increase likelihood of suicidal ideation and attempt (Geoffroy et al., 2016; Winsper et al., 2012). Importantly, any involvement in bullying—whether it is a perpetrator, victim, or especially both—heightens risk of subsequent suicidal thoughts and behaviours (Kim et al., 2009; Klomek et al., 2008; Winsper et al., 2012).

An emerging line of research has focused on cyberbullying, which is similar to and often co-occurring with traditional bullying (Wang, Iannotti, Luk, & Nansel, 2010) but specifically occurs through electronic devices such as cell phones or computers (Hinduja & Patchin, 2010). Other distinguishing features of cyberbullying include perpetrator’s anonymity, and the potential frequency and chronicity of victimization (e.g., potential to bully 24 hours a day vs. in select settings). Cross-sectional studies have demonstrated that both perpetration and victimization from cyberbullying were associated with suicidal ideation and attempts (Bauman, Toomey, & Walker, 2013; Hinduja & Patchin, 2010; Litwiller & Brausch, 2013). Cyberbullying has been shown to have comparable, or perhaps even stronger effects, than traditional forms of bullying (Hinduja & Patchin, 2010; Bauman et al., 2013; Van Geel, Vedder, & Tanilon, 2014).

Peer and media influence

Another consideration is whether other suicides have occurred in the environment. There have been multiple lines of evidence demonstrating time-space clustering of suicides (i.e., point clusters). Studies show that these point clusters are more common among adolescents (e.g., 15–19 years), and rare among populations older than 24 years-old (Gould, Petrire, Kleinman, & Wallenstein, 1994; Gould, Wallenstein, Kleinman, O’Carroll, & Mercy, 1990; McKenzie & Keane, 2007). Although the occurrence of point clusters is largely accepted by the field, there remain several interpretations of exactly how or why these clusters emerge (Joiner, 1999). Social learning theory is one possibility, and is supported by longitudinal studies that have explored the role of peer influence. These studies have demonstrated that having a friend who attempted or died by suicide predicts future suicide attempt in adolescence (Borowsky, Ireland, & Resnick, 2001). Additional explanations (Haw, Hawton, Niedzwiedz, & Platt, 2013) include complicated bereavement, social integration, as well as assortative relating (i.e., similarly vulnerable individuals becoming socially contiguous and susceptible to joint life stress; Joiner, 2003).

Mass clusters, which are defined by suicides occurring within a similar time and often through media influence, are related to but distinct from point clusters. Findings on mass clusters, relative to point clusters, are less supported. Some studies demonstrate mass clusters across countries following widely publicized media coverage of suicide (e.g., Niederkrotenthaler et al., 2012), whereas others challenge the notion that media has imitative effects (e.g., Kessler, Downey, Milavsky, & Stipp, 1988).

Relevant to media usage, the field has increasingly explored the potential influence of the internet, a common source of suicide-related information (Dunlop, More, & Romer, 2011). In a rare longitudinal study exploring various sources of suicide-related information, online discussion forum usage was shown to increase suicidal ideation over time controlling for prior history of suicidal ideation and depression, as well as exposure to peer influence (Dunlop et al., 2011). Other sources such as social networking sites and online news did not have as strong of an effect. Specific countries have taken steps to legally ban or block websites discussing practical aspects of suicide (Biddle, 2008). An additional consideration is that positive effects of the internet have been documented, including the offering of help and social support (Mars et al., 2015). This area of research is still emerging and requires greater and more rigorous study.

Psychological risk factors and correlates

Below we discuss prominent psychological correlates and risk factors of suicidal thoughts and behaviours among youth. These are organized into the domains of affective, cognitive, and social processes, and have primarily been measured through self-report, behaviour, and physiology. For the purpose of the present review, affective processes pertain to psychological factors that are emotionally valanced, and largely pertain to negative affect. Implications of positive affect (or lack thereof), as well as affect or emotion regulation, are also described. Cognitive processes pertain to impulse control (i.e., impulsivity) and select information processing biases. Social processes pertain to psychological processes oriented toward others, including the observed degree and engagement in interpersonal relationships. Overall, psychological processes have received varying degrees of evidence. Negative affect-related processes have been most strongly supported (with notable exceptions), and prominent cognitive and social processes have received moderate support. The present focus on psychological processes paper marks a departure from the more traditional focus on suicidal thoughts and behaviours as an outcome of psychiatric diagnoses. This approach represents an area in need of greater attention as described under future directions.

Affective processes

Evidence in support of negative affect-related processes ranges from strong to moderate, depending on the aspect of negative affect examined. Strong evidence supports worthlessness and low self-esteem as risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviours in youth. Self-reported worthlessness3 and low self-esteem, as well as behavioural measures of negative self-referential thinking, have been found to predict future suicidal ideation and suicide attempt controlling for other symptoms of depression and baseline suicidal thoughts and behaviours (e.g., Burke et al., 2016; Lewinsohn et al., 1994; Nrugham, Larsson, & Sund, 2008; Wichstrøm, 2000). Similar findings have been detected for neuroticism (i.e., tendency to respond to threat, frustration, and loss with negative affect; Enns, Cox, & Inayatulla, 2003; Fergusson et al., 2000). Other aspects of negative affect, such as hopelessness, may play a more nuanced role in predicting suicidal thoughts and behaviours. Multiple longitudinal studies involving adolescents have now demonstrated that hopelessness may be a more distal risk factor, as it does not predict suicidal ideation or attempt controlling for baseline factors such as suicide attempt history and depression (Ialongo et al., 2004; Myers et al., 1991; Prinstein et al., 2008). This contrasts with more promising findings detected among young adults (Miranda, Tsypes, Gallagher, & Rajappa, 2013; Smith, Alloy, & Abramson, 2006). Although hopelessness may not uniquely account for the occurrence of suicidal thoughts and behaviours within a single, fixed time point among adolescents, emerging work highlights the role it may play in identifying chronicity and trajectory of suicidal thoughts and behaviours over time. Specifically, controlling for baseline psychopathology, hopelessness has been shown to characterize adolescents whose suicidal ideation remained elevated over time compared to those who persistently endorsed sub-clinical levels of suicidal ideation (Czyz & King, 2015; Wolff et al., 2017).

Evidence in support of positive affect-related processes is promising, and particularly strong in the case of anhedonia, or the lack of positive affect or inability to experience pleasure. Building on cross-sectional findings that have identified greater levels of anhedonia among adolescent suicide attempters than controls (Auerbach, Millner, Stewart, & Esposito, 2015; Nock & Kazdin, 2002), anhedonia has also been shown to predict subsequent suicide-related events (e.g., suicide attempt or intervention to prevent a suicide attempt) controlling for baseline suicidal ideation, sexual abuse, borderline personality disorder (Yen et al., 2013). Other aspects of positive affect, including blunted reward responsivity and reward learning deficits, have been assessed using physiological and behavioural measures in cross-sectional studies.

The ability to observe and change emotions is highly relevant to the experience of negative and positive affect. There are few longitudinal studies showing that distinct facets of emotion dysregulation relate to suicidal ideation and attempt during adolescence. One longitudinal study demonstrated that difficulty identifying emotions and limited access to effective regulation strategies predicted subsequent suicide attempt controlling for baseline depressive symptoms (Pisani et al., 2013). Ultimately, it was shown that having limited emotion regulation strategies was more predictive than difficulty identifying emotions (Pisani et al., 2013), replicating prior longitudinal studies with young adults (Miranda et al., 2013), and cross-sectional studies in adolescents (e.g., Cha & Nock, 2009; Rajappa, Gallagher, & Miranda, 2012; Weinberg & Klonsky, 2009). Specific approaches of emotion regulation, largely maladaptive cognitive strategies such as rumination and suppression of negative thoughts and feelings, have been linked with suicidal ideation in adolescents and young adults as well (Burke et al., 2016; Miranda et al., 2013; Najmi, Wegner, & Nock, 2007; Smith et al., 2006). Emerging work on adaptive strategies among youth (e.g., distraction and problem-solving) points to promising alternatives that may buffer against suicide risk, and be even more predictive than maladaptive strategies (Burke et al., 2016). An additional consideration is the flexibility with which one implements emotion regulation strategies, such as suppression or expression of emotions (Bonanno & Burton, 2013).

Cognitive processes

The most frequently studied cognitive process in the youth suicide literature is impulsivity4 which has received moderate support as a risk factor for suicidal thoughts and behaviours. Trait impulsivity, typically assessed using self-report measures, has been shown to prospectively predict suicidal ideation and suicide attempt among adolescents and young adults (Kasen, Cohen, Chen., 2011; McKeown et al., 1998). But when assessed in multivariate models, it has been shown to only be predictive of select outcomes such as suicide plan, and not suicidal ideation and attempt (McKeown et al., 1998). Other investigations of impulsivity have been largely cross-sectional, and with mixed findings. This maps onto the adult literature, which increasingly suggests that the association between impulsivity and suicidal thoughts and behaviours alone is small (Anestis, Soberay, Gutierrez, Hernández, & Joiner, 2014). But when it is considered in combination with aggression, impulsivity (i.e., impulsive aggression) can be a more robust correlate and potential risk factor (Brent et al., 2002). Impulsive aggression has been shown to predict family transmission of suicide risk (Brent et al., 2003; Brent et al., 2015; McGirr & Turecki, 2007), and complements the research supporting anger and aggression as prospective risk factors for suicidal ideation and attempt (Myers et al., 1991; Yen et al., 2013), especially among male adolescents (Daniel, Goldston, Erkanli, Franklin, & Mayfield, 2009; Lambert, Copeland-Linder, & Ialongo, 2008). Of note, efforts to clarify impulsive aggression have been encouraged (García-Forero & Gallardo-Pujol, Maydeu-Olivares, Andrés-Pueyo, 2009), along with exploring its overlap with related constructs (e.g., emotion regulation, angry rumination, reduced self-control; Denson, Pederson, Friese, Hahm, & Roberts, 2011; Long, Felton, Lilienfeld, & Lejuez, 2014).

Another consideration regarding impulsivity is the way it is assessed. Direct comparisons between behavioural and self-report measures of impulsivity have shown that behavioural tasks better differentiate adolescent suicide attempters and non-attempters than self-report measures (e.g., Horesh, 2001). However, the same behavioural task (e.g., Iowa Gambling Task) has yielded conflicting results with adolescent suicide attempters sometimes performing better (Pan et al., 2013) and other times worse (Bridge et al., 2012) than non-suicidal control groups. Efforts to identify the neural circuitry related to response inhibition (i.e., during the Go/NoGo Task) show no difference between adolescent suicide attempters from a healthy control comparison group, with only remarkable group differences emerging among depressed non-attempters (i.e., greater activation in bilateral anterior cingulate gyrus and left insula; Pan et al., 2011). Another complicating factor within this construct is the high heterogeneity of effects detected in a recent meta-analysis examining the effects of cognitive control on suicidal ideation and suicide death (Glenn et al., in press).

Cross-sectional findings have emerged supporting the role of individual information-processing biases in relation to suicidal thoughts and behaviours, largely through cross-sectional studies. For instance, relevant to attentional biases, emerging evidence using the Attention Network Task suggests that adolescent suicide attempters show deficits in sustained attention and vigilance (i.e., alerting attention network) compared to non-attempters (Sommerfeldt et al., 2016). In contrast, this study showed that there are no group differences in other types of attention networks (i.e., orienting, executive). As another example, relevant to memory biases, adolescent suicide attempters have been shown to recall autobiographical memories in a manner that is overgeneralized and less specific compared to non-attempters (Arie, Apter, Orbach, Yefet, & Zalzman, 2008). This is the case regardless of whether memories are positive or negative (Arie et al., 2008), and may have effects that are specific to memory recall from the field or first-person perspective (Chu, Buchman-Schmitt, & Joiner, 2015).

Social processes

One of the most common social processes assessed longitudinally is interpersonal connectedness (e.g., loneliness). Despite the relatively high degree of attention received, there remains moderate evidence in support of loneliness as a direct and proximal risk factor for subsequent suicidal ideation and attempt during adolescence (e.g., Gallagher, Prinstein, Simon & Spirito, 2014; Jones, Schinka, van Dulmen, Bossarte, & Swahn, 2011; Wichstrøm, 2000). Bivariate prospective models demonstrate a significant relationship over time, but multivariate prospective models suggest that the effect of loneliness on suicidal thoughts and behaviours during adolescence may be mediated by psychopathology (Jones et al., 2011; Lasgaard, Goossens, & Elklit, 2011). There may be select cases where loneliness plays a more central role, such as mediating the relationship between social anxiety and subsequent suicidal ideation during adolescence (Gallagher et al., 2014), or the prediction of suicide attempt later in life, specifically early adulthood (Johnson et al., 2002). Related to loneliness, specific aspects of the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide (Joiner, 2005) such as thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness have been shown to predict suicidal thoughts and behaviours in youth. Specifically, thwarted belongingness has been shown to interact with acquired capability to predict suicide attempt in female adolescents, and perceived burdensomeness has been shown to interact with acquired capability to predict suicide attempt in males (Czyz, Berona, & King, 2015). Continued exploration of gender-specific effects, and the interaction between social and other psychological processes, is encouraged.

Social communication and response processes are critical to maintaining interpersonal relationships. Innovative work has been initiated in this area, although most of it has been through cross-sectional studies and remains tentative. As one example in the area of social communication, distinct patterns of prosodic and voice quality-related features (e.g., breathy voice quality) have been detected among adolescent suicide attempters compared to non-attempters (Scherer, Pestian, & Morency, 2013). This has been possible through the application of machine learning techniques to the dynamic components of prosody and vocalizations (Pestian et al., 2017). As another example in the area of social response processes, adolescents who have experienced suicidal ideation or attempt have been shown to demonstrate atypical (i.e., hypo- or hyper-responsive) patterns of cortisol response to social stress compared to non-suicidal adolescents (Giletta et al., 2015; Melhem et al., 2016), although findings remain mixed in directionality and depending on context (e.g., baseline cortisol vs. cortisol reactivity to interpersonal stressors; Mathew et al., 2003; Young, 2010) and method of data collection (e.g., salivary vs. hair cortisol; Melhem et al., 2017).

Biological correlates

Below we discuss several types of biological correlates (intentionally not labelled as “risk factors” as most studies reviewed here are cross-sectional in nature). They are organized according to circuits, molecules, and genes. Biological processes are advantageous to study as they can corroborate findings based on behavioural and self-report measures, expand etiological understanding of suicide risk, and introduce potentially malleable targets of intervention. This work therefore remains tentative overall, but marks one of the most innovative and rapidly evolving areas of the literature. Compared to the body of literature on environmental and psychological risk factors and correlates, there are fewer studies within the youth suicide literature. Therefore, each study here is described in relatively more detail. Substantial efforts have been made to control for potential confounds such as psychiatric diagnoses, which are noted throughout and offer relatively stronger evidence in support of these biological mechanisms.

Circuits

Using measures of resting state functional connectivity—an index of the pattern of neural activation across interconnected structures while participants are not performing a specific task—several research groups have identified key brain circuits that appear to be atypical in suicidal youth. For example, Chinese adolescent suicide attempters, free of other psychopathology, showed differences in functional connectivity between several neural regions, relative to healthy controls (Cao et al., 2015). The regions with significantly lower functional coupling included the left fusiform gyrus, left hippocampus, left inferior frontal gyrus, right angular gyrus, bilateral posterior lobes of the cerebellum, bilateral parahippocampal gyrus, and bilateral middle frontal gyrus, suggesting that the connectivity between these regions appears to be aberrant in those who are suicidal. The suicide attempt group had significantly higher functional coupling of the right inferior parietal lobe, left praecuneus, and right middle frontal gyrus. Importantly, these effects were independent of age, sex, level of education, and clinical characteristics, but should be considered preliminary given a small sample size.

Within this complex network of interconnected brain regions, the hippocampus and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC; a component of which is the middle frontal gyrus), stand out as particularly relevant. The hippocampus, which is connected with the body’s stress response system and important in mood regulation and memory, has been found to be structurally abnormal in suicide attempters (Gosnell et al., 2016). Similarly, the dlPFC is involved in goal-directed behaviour, decision-making and emotion regulation, and is also found to be structurally abnormal in suicide attempters (Gosnell et al., 2016).

Another set of interconnected brain regions, known as the default mode network (DMN), has been implicated in conditions relevant to suicide, such as depression, in adolescents (Ho et al., 2015). The DMN has been shown to be engaged when participants are not occupied by a specific task (i.e., by “default”), although abnormal function of the DMN may reflect an altered capacity to integrate important information to create mental simulations that are useful for a wide range of mental processes (Buckner, Andrews-Hanna, & Schacter, 2008). Zhang and colleagues (2016) found that the DMN can be abnormally connected among adolescent suicide attempters, as demonstrated through their increased connectivity in the cerebellum, and decreased connectivity in the right posterior cingulate cortex (PCC). Further, compared to depressed non-attempter peers, adolescent suicide attempters showed increased connectivity in the cerebellum and left lingual gyrus, and decreased connectivity in the right praecuneus. None of the groups differed significantly in age, sex, education, or IQ. Although sample size was limited, these results are the first to indicate that DMN abnormalities may be a biomarker for suicide risk, and are especially important in that they highlight altered DMN function as an index for suicide attempt in depressed, at-risk adolescents (Zhang et al., 2016). The exact implications on suicidal thoughts and behaviours of abnormal functional connectivity in brain networks like the DMN remain unclear. However, these results represent an important starting point for continued neuroimaging research.

Molecules

Alterations in serotonin function are among the most widely cited molecular correlates of suicidal behaviour, and provide moderate-to-strong evidence given efforts to control for psychiatric diagnoses. Early research suggested a possible link between suicide and reduced levels of serotonin (5-hytdroxytryptomine; 5-HT) and its primary metabolite, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) levels by comparing the cerebrospinal fluid of adults who had died by suicide and controls (e.g., Lloyd, Farley, Deck, & Hornykiewicz, 1974). Studies of serotonin and suicide are relatively rare in adolescents, but some indicate that serotonergic abnormalities may be associated with increased suicide risk. For instance, Pandey and colleagues (2002) found higher binding to 5HT2A receptors in the post-mortem brains of adolescents who had died by suicide, compared to adolescents who died from other causes. This effect was found to be most prominent in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus, and was independent of psychiatric illness.

Emerging evidence also suggests that proinflammatory markers may play a role in suicide risk. Pandey et al. (2012) found increased levels of the gene and protein expression of two of such markers, tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interluken-1 beta, in the prefrontal cortices of a small sample of teenagers who had died by suicide relative to non-suicidal controls. Importantly, control analyses revealed that these effects were not due to age, gender, pH of the brain, time between death and analysis, or antidepressant treatment. Melhem and colleagues (2017) similarly found that TNF-α and C-reactive protein, were elevated in teens and young adults who had attempted suicide, relative to those who had suicide ideation and healthy controls. Of course, these results may be confounded by the injurious nature of these attempts (e.g., hanging, gunshot, ingestion of toxic substance), and should be interpreted with caution. Furthermore, the exact pathways between proinflammatory cytokines and suicidal thoughts and behaviours have not been established. However, chronic early-life stress can result in reduced levels of cortisol, which may fail to suppress the body’s immune response, leading to increased inflammation (Danese et al., 2008). It may be that chronic stressors such as early adversity, which is related to both suicide and inflammation (Baumeister et al., 2016), could drive the relationship between suicide and inflammation among youth. These two studies indicating elevated inflammation in suicidal teens may be a promising area of continued research. Additional considerations when exploring inflammation as a biomarker include contextual factors such as sleep duration (Patel et al., 2009) and body fat mass (Festa et al., 2001).

Brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is an important protein responsible for the protection and development/proliferation of various neurons. BDNF appears to be negatively impacted by stress, as well as by the functioning of the aforementioned 5HT2A receptor (Vaidya, Terwilliger, & Duman, 1999), and low levels of BDNF have been widely implicated in affective disorders (e.g., Karege et al., 2005). The only study to date that has examined BDNF in youth suicide found significantly lower levels of BDNF protein expression in the prefrontal cortex (PFC), but not the hippocampus of youth suicide victims relative to controls (Pandey et al., 2008). Further, they found lower mRNA expression of BDNF in both the PFC and hippocampus of youth suicide victims relative to controls (Pandey et al., 2008). Importantly, the authors found no confounding effects of age, gender, brain pH, time between death and analysis, or antidepressant treatment. Although this study should be considered preliminary evidence as it is a small sample and the first study to examine these relationships among youth, its results match those found with adults (Salas-Magaña et al., 2017), and dovetail nicely with studies on the relationship between stress and suicide among youth (e.g., Giletta et al., 2015).

Genes

Familial transmission of suicidal behaviour is well established (e.g., Roy, 1983; Brent et al., 2015). The exact role of genetic heritability in suicidal behaviour is less clear, although convincing studies do suggest there is a heritable component of suicidal behaviour. For example, recent meta-analytic data have demonstrated that across a range of studies, there are significant differences in suicide rates between mono- (MZ) and dizygotic (DZ) twins, with overall concordance rates for registry-based studies of 24%MZ and 2.8%DZ (Voracek & Loibl, 2007). In a very large (n = 85,000) study of twins in Sweden, researchers found concordance rates of 5.8%MZ and 1.8%DZ (Pedersen & Fiske, 2010). However, when concordance rates were examined separately for females and males, they found female rates of 11%MZ/0%DZ, and male rates of 3%MZ/2%DZ (Pedersen & Fiske, 2010). Thus, it appears sex may be a relevant moderator when considering the heritability of suicide, and could perhaps help clarify mixed findings within this area of the literature.

There remain several areas in need of greater attention within the realm of genetic risk for suicide. First, the field is sorely lacking genome-wide association studies (GWAS) to identify genetic variants of suicide-related outcome among youth (Mirkovic et al., 2016). To date, research has examined the contribution of specific candidate genes in suicide risk among youth. Although less convincing, this approach has allowed researchers to examine genetic markers of behavioural traits in relation to certain outcomes, such as suicide attempt. The most extensively studied genetic markers for suicide risk in youth are those associated with the serotonergic system, likely as a function of a large number of findings (reviewed above) implicating serotonin dysfunction in suicidal thoughts and behaviours. In adults, suicidal behaviour is linked with the genetic basis of serotonin function. However, the relationship between serotonin-related genes and youth suicidal behaviour is tenuous. For instance, Zalsman and colleagues (2001) found that a polymorphism in the promoter region of the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR) is associated with aggressive behaviour in a sample of adolescent suicide attempters, but not associated with suicidal attempt, per se. One distinct possibility is that genes influence suicidal behaviours via other risk factors such as impulsive aggression, as described above.

The possibility of a gene-by-environment interaction producing increased risk for suicide has also been examined, although results have not demonstrated consistent results. Although some studies have reported these interactions (e.g., Caspi et al., 2003), a recent collaborative meta-analysis including 31 datasets suggests that these interactions do seem to exist at least for depression (Culverhouse et al., 2017).

Finally, epigenetic alterations to genetic expression early in life could be relevant for later suicide risk. McGowan and colleagues (2009) recently found that suicide victims who had histories of childhood abuse had lower hippocampal glucocorticoid mRNA expression than either suicide victims without histories of abuse, or control subjects, an effect that was independent of psychiatric diagnosis. Such a result suggests that severe early-life adverse experiences have epigenetic effects that may increase the likelihood of suicide by altering the body’s stress response system (McGowan et al., 2009).

Treatment of suicidal behaviour

How do we reduce risk of suicide early in life? What are the best psychological intervention and prevention strategies for children and adolescents? Here we primarily draw from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to outline the efficacy of psychotherapeutic approaches intended to treat and prevent suicidal thoughts and behaviours among youth.

Psychological treatment

Overall, psychological treatments with the strongest preliminary support of efficacy for reducing suicidal thoughts and behaviours among youth emphasize behaviour change, skill-enhancement, and strengthening of interpersonal bonds. Several different formats of psychological treatment are described below5

Individual and family therapy

The combination of individual and family therapy has been shown to be efficacious for treating suicidal youth. Integrated Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (I-CBT), for instance, combines individual and family CBT techniques as well as a parent training component (Esposito-Smythers, Spirito, Kahler, Hunt, & Monti, 2011). Similarly, Attachment-based Family Therapy (ABFT) aims to enhance the quality of attachment bonds via an interpersonal approach to individual and family therapy, as well as parent skills training (Diamond et al., 2010). Initial evidence from RCTs suggests positive immediate and short-term post-intervention effects for I-CBT and ABFT compared to an active control condition (Diamond et al., 2010; Esposito-Smythers et al., 2011). Adolescents receiving six months of I-CBT had significantly fewer suicide attempts over an 18-month study period (Esposito-Smythers et al., 2011). ABFT was also found superior to an active control at reducing suicidal ideation, and the differences were maintained at 6 month follow-up (Diamond et al., 2010). These findings are promising because the intervention effects were maintained after delivery of treatment. Similarly, ABFT is one of the few modalities to evidence positive outcomes in a predominantly ethnic minority sample (Diamond et al., 2010). However, the findings for both trials are limited due to low rates of treatment completion in the control condition. It is difficult to determine what I-CBT and ABFT were compared to because adolescents and families in the control condition did not receive adequate dosage of treatment.

Several forms of individual treatment that teach psychological and interpersonal skills have been shown to decrease the risk of suicidal behaviour among youth. For instance, Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT), a treatment focused on strengthening skills in interpersonal effectiveness, as well as mindfulness, distress tolerance, and emotion regulation, has been adapted for adolescents (DBT-A; Miller, Rathus, Linehan, Wetzler, & Leigh, 1997) by adding family therapy, and multifamily skills training. Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT) for youth in school settings (IPT-A-IN) is another approach that addresses the social and interpersonal context of symptoms with a focus on developmentally appropriate interpersonal problems (Tang, Jou, Ko, Huang, & Yen, 2009). Preliminary evidence shows that DBT-A (Mehlum et al., 2014) and IPT-A-IN (Tang et al., 2009) are superior to active control conditions for reducing severity of suicidal ideation in youth over the course of treatment. Longer-term, posttreatment effects are more select, as DBT-A has been shown to reduce (suicidal and nonsuicidal) self-harm at one-year follow-up but not suicidal ideation (Mehlum et al., 2016), and the IPT-A-IN trial did not report longer-term data. Additional research is needed to continue assessing the long-term effects of these interventions and to determine whether DBT-A is efficacious for reducing non-suicidal forms of self-harm, suicidal forms of self-harm, or both.

Brief interventions during high-risk periods

Interventions implemented post-discharge from emergency departments (ED) or acute care settings are another important part of suicide treatment efforts gaining empirical support. Some of the interventions that have been evaluated include components that address crisis management (e.g., safety planning), youth and parent psychoeducation and skills-training, as well as linkage and compliance with follow-up care (Asarnow, Hughes, Babeva, & Sugar, 2017). There is initial evidence that speaks to the acceptability and utility of safety planning as a stand-alone intervention to help patients identify effective coping strategies for suicidal crises (Kennard et al., 2015; Stanley & Brown, 2012). Additionally, multiple-component post-ED interventions have been found superior to routine care for improving outpatient treatment compliance (Asarnow et al., 2011). Initial evidence from a small RCT indicates these interventions may also be efficacious for reducing suicide attempts (SAFETY Program; Asarnow et al., 2017). The promising effects observed on suicide behaviour outcomes remain to be replicated since the initial trial was limited by high drop-out rates in the control group.

Technology-based interventions

Recent studies have begun to identify cognitive and affective markers of increased suicide behaviour risk, which may serve as new treatment targets. As just one example, prior studies have demonstrated that people who engage in suicidal or non-suicidal self-injurious behaviours have positive implicit associations with the concepts of death, suicide, or self-injury (e.g., Franklin, Puzia, Lee, & Prinstein, 2014; Nock & Banaji, 2007). Following up on this finding, in one recent study investigators used an evaluative conditioning procedure delivered via a game-like smartphone app to create in some adult participants an aversion to death/suicide/self-injury. They found across three RCTs that online-recruited individuals receiving this intervention had reduced engagement in suicidal and self-injurious behaviour (e.g., self-cutting, suicidal behaviours; Franklin et al., 2016). These results are promising but preliminary, since intervention effects did not generalize to suicidal ideation and did not persist one month later. These caveats aside, the continued development and improvement of these types of interventions are encouraged given the low-cost and easily disseminable intervention format. Future research is needed to continue testing the efficacy of these approaches, as their novel mode of treatment delivery fits the preferences of technologically-savvy youth and holds potential for overcoming barriers to care.

Prevention

The development of prevention strategies is critical, given the enormous increases in the prevalence of suicidal thoughts and behaviours that occur during adolescence, coupled with our poor ability to predict suicidal behaviour. Suicide prevention strategies include universal programs addressed at entire youth populations to educate about risk and identify cases, selective prevention strategies countering a risk factor shared within a specific subgroup, and indicated prevention interventions addressed at symptomatic individuals who are not formally diagnosed or in-treatment.

Universal prevention

Many suicide prevention efforts focus on school-wide education and screening to educate about suicide signs and symptoms and identify those at-risk in the general population. The strongest preliminary evidence for the ability of these programs to reduce suicidal behaviour stems from a recent multisite RCT across European countries. Schools assigned to The Youth Aware of Mental Health Programme showed reductions in self-reported suicidal ideation and attempts in comparison to those assigned to only poster-versions of suicide-education materials (Wasserman et al., 2015). Additionally, a high school-based RCT found significantly fewer self-reported suicide attempts and increased knowledge about suicide at three-months post-intervention among adolescents assigned to the Signs of Suicide program in comparison to the regular school curriculum (Aseltine, James, Schilling, & Glanovsky, 2007). However, there were no differences in suicidal ideation or help-seeking behaviours for students in the intervention group versus those in the lagged control group. Replication of findings is needed to strengthen empirical support for the aforementioned programs.

Screening interventions similarly aim to identify cases of adolescents at risk by conducting formal mental health assessments in daily-life settings (e.g., in school). To date, there is modest evidence of improved rates of referral to mental health services and completion of referrals among high-school students from a small RCT evaluating screening with an adapted version of the Columbia TeenScreen versus routine school procedures (Husky et al., 2011). Similarly, there is preliminary evidence for improved attendance to mental health services associated with adding an optional online counselling component to online screening for college students (eBridge; King et al., 2015). However, replication of these findings with larger samples and longer time frames are necessary to determine the robustness of these effects. Additionally, available evidence does not support the superiority of screening interventions for reducing suicidal thoughts and behaviours (Wasserman et al., 2015). More work is required to translate the improved referral and attendance rates into clinically-meaningful effects for suicidal thoughts and behaviours. Gatekeeper programs train individuals in helping-roles with strategies to respond effectively to youth who are at-risk for suicide. Available evidence does not support the superiority of gatekeeper programs for reducing suicidal thoughts and behaviours in comparison to minimal intervention (i.e. suicide-education posters in classrooms; Wasserman et al., 2015). More evidence is needed regarding effects on intermediate outcomes (e.g., mental health referrals) and gatekeeper behavioral outcomes (e.g. approaching students to ask about suicide) (Wyman et al., 2008, 2010). Well-known gatekeeper programs such as Question, Persuade, Refer (QPR), as well as emerging approaches testing school-based peer gatekeeper programs such as Sources of Strength (Wyman et al., 2008, 2010), have not shown reductions in suicidal thoughts and behaviors despite reported improvement in some intermediate outcomes (e.g., perceptions of adult support and help-seeking attitudes). Data available from youth healthcare settings are also insufficient to determine the benefits of screening or gatekeeper programs for reducing suicidal thoughts and behaviors, but suggest that the programs would be acceptable to families and have promising potential for referral rates (Ballard et al., 2012; Wissow et al., 2013).

Selective prevention

Some programs aim to pre-empt the development of common risk factors for suicidal behaviours and other mental health outcomes by teaching adaptive skills such as problem solving and self-regulation, and enhancing social support. Despite the lack of evidence to support the efficacy of these interventions in school settings (Eggert, Thompson, Randell, & Pike, 2002; Thompson, Eggert, Randell, & Pike, 2001) there are encouraging preliminary findings for family-based risk prevention and resilience programs. A number of interventions targeting sources of family conflict or stress (e.g., parental loss, parent-child acculturation gaps, military deployment) with the aim to prevent substance abuse, internalizing, and externalizing disorders, have also been evaluated for their impact on suicidal thoughts and behaviours (e.g., Connell, McKillop, & Dishion, 2016; Gewirtz, DeGarmo, & Zamir, 2016; Sandler, Tein, Wolchick & Ayers, 2016; Vidot et al., 2016). RCTs testing the long-term effects of the Family Check-Up and the Family Bereavement interventions evidenced reductions in a composite score of suicide ideation and behaviour in youth at follow-up, up to 10- and 15-years after delivery of the intervention (Connell et al., 2016; Sandler et al., 2016). Important avenues remain for future study of the long-term effects of family-based prevention programs on youth suicidal thoughts and behaviours.

Indicated prevention and crisis support

Indicated prevention strategies such as suicide hotlines respond to the immediate needs of suicidal individuals during a crisis. Crisis support services such as school postvention programs address the needs of the surrounding community after a suicide-related event. The benefits of crisis lines for reducing suicidal behaviour have not been studied in suicidal youth and results are mixed for adult callers (Gould, Cross, Pisani, Munfakh, & Kleinman, 2013; Gould, Kalafat, Munfakh, & Kleinman, 2007; Gould, Munfakh, Kleinman, & Lake, 2012). Additionally, there is a gap in formal evidence for the efficacy of school postvention programs for reducing suicide risk (Hazell & Lewin, 1993; Poijula, Wahlberg, & Dyregrov, 2001).

Future directions

Throughout the review, we have highlighted knowledge gaps within specific content areas. But there remain several overarching caveats and limitations of the present review, which reflect those of the literature broadly. We highlight these below, and recommend ways for future research to address existing conceptual and methodological challenges. These challenges and proposed future directions pertain to the topics of: (1) Taxonomy and Operationalization; (2) Etiology: Improving “What” We Study; (3) Etiology: Improving “How” We Study; (4) Developmental Sensitivity; and (5) Diversity.

1. Taxonomy and operationalization

This review used a broad definition of suicidal thoughts and behaviours, and reflects the lack of consistent taxonomy and operational definitions throughout the suicide literature. There appears to be a new taxonomy for suicidal thoughts and behaviours introduced every several years—some that recognize certain phenomenological distinctions, and some that do not (e.g., active vs. passive ideation; suicide attempt with vs. without injury; aborted vs. interrupted suicide attempt; O’Carroll et al., 1996; Posner, Oquendo, Gould, Stanley & Davies, 2007). This is not an inherent limitation of the literature, but it becomes one when it is unclear which empirical study subscribes to which taxonomy and set of operational definitions. It is not uncommon for papers featuring a case-control design to describe a sample consisting of “suicidal patients” without further information about whether this refers to suicidal ideation or suicide attempt, severity of the outcome, or time frame—threatening the internal validity of the study given “diffusion” of cases between case and control groups (Kazdin, 2003). Relatedly, it is not uncommon for a suicide-related outcome to be measured using a single-item assessment, which may also threaten validity of findings and be more prone to misclassification of cases (Millner, Lee, & Nock, 2015).

Recommendations

Future studies are encouraged to, at minimum, provide sufficient detail regarding the operationalization of suicidal thoughts and behaviours. These details should specify whether or not a standard suicide measure was used (e.g., drawing from resources such as the PhenX Toolkit; Hamilton et al., 2011), and if not, a clear operational definition specifying severity of suicidal intent, method, presence or absence of physical injury, should be provided. These suicidal thoughts and behaviours should ideally be measured using multi-item assessments to avoid misclassifications and potentially false conclusions. Furthermore, future research efforts are encouraged to examine the clinical significance of operational definitions emerging from existing taxonomies to inform the evolving taxonomy of suicidal thoughts and behaviours. As a final note—beyond the focus on individual suicidal thoughts and behaviours—greater emphasis on the transition and timing across these outcomes (i.e., pathway toward suicide; Millner, Lee, & Nock, 2016) is encouraged.

2. Etiology: Improving “what” we study

There are several types of correlates and risk factors within the literature that are relevant to, but do not directly test, etiology. First—while it is not reflected in the present review—a substantial portion of the suicide literature has focused on diagnostic risk factors (Franklin et al., 2017). Psychiatric diagnoses help identify high-risk populations, but are often times too heterogeneous to explain precisely how and why suicide risk emerges. The claim that depression is a risk factor for suicidal ideation and attempt, while true, is minimally helpful in elucidating etiology due to multiple combinations of depressive symptoms, subtypes, trajectories and comorbidities (Chen, Eaton, Gallo, & Nestadt, 2000). A more granular or symptom-based approach to identifying potential etiological mechanisms is needed.

Second, much of the suicide literature has focused on correlates and risk factors that are either assumed to be static, or have not otherwise been tested for their malleability. It is relatively rare to test whether a change in mechanism corresponds with change in suicidal thoughts and behaviours. This leaves open the question of what can truly cause an increase or decrease in suicide risk.

Recommendations

First, future research pertaining to etiology is encouraged to focus on psychologically- or biologically-based mechanisms that resemble symptoms of or vulnerabilities to psychiatric diagnoses, but that are ultimately agnostic to existing diagnostic classification systems. The current paper highlights work aligned with this approach. For sake of organization, frameworks such as the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) of the National Institute of Mental Health (e.g., Cuthbert & Kozak, 2013) may be helpful.6 The RDoC approach aims to understand the psychological constructs, which are organized into five general “domains” that lead to the development of mental disorders: Negative Valence Systems, Positive Valence Systems, Cognitive Systems, Social Processes System, and Arousal and Regulatory Systems. Frameworks such as RDoC offer a standardized way to tease apart individual symptoms (e.g., anhedonia vs. depressed mood; Auerbach et al., 2015) and highlight understudied domains (e.g., sleep disturbance via Arousal and Regulatory Domain; Liu & Buysse, 2006), which can ultimately be used to explore promising interactions across domains and units of analyses to better understand and predict suicidal thoughts and behaviours.

Second, we encourage the identification of risk factors that are not only granular, but also are potentially malleable. This means prioritizing mechanisms whose change can be observed, and in turn assessing change in relation to change in suicide-related outcomes. By prioritizing the identification of such variable or causal risk factors (Kraemer et al., 1997), the field may improve etiological understanding and identify viable targets of intervention.

3. Etiology: Improving “how” we study

Beyond the concern of what potential etiological mechanisms are studied, we also recommend an evolution in how these are studied. First, there remains a palpable disconnect between mechanisms that can be observed at the level of genes, cells, molecules, circuits, and physiology, and those that can be observed at the level of behaviours or self-report measures. Even in healthy and well-studied populations, brain structure and neuroendocrine indices have been difficult to link to behaviours. This is reflected in the youth suicide literature, which mostly indicates group differences on discrete and largely isolated constructs. A different but equally important disconnect is that between mechanisms and environmental impact, with very few studies exploring epigenetic mechanisms among youth. More work is needed to close these gaps.

Second, much of the suicide literature focuses on relatively long-term effects. Fewer than 1% of all prospective studies have follow-ups shorter than 1 month (Franklin et al., 2017), which eliminates our ability to see if new or previously studied factors tell us anything about the rapidly changing nature of suicidal ideation. Retrieving short-term, prospective data through these means marks a critical step to improving prediction of suicidal thoughts and behaviours (Glenn & Nock, 2014).

Recommendations

First, future research efforts are encouraged to integrate findings along multiple units of analyses. This can be done by engaging in cross-disciplinary collaborations, particularly those that integrate across disciplines of genetics, molecular biology, neuroscience, physiology, psychology, and psychiatry. Frameworks such as RDoC may be helpful in guiding potentially fruitful intersections. The field of youth suicide research would also benefit from reaching beyond traditional tools used in psychology research, such as the integration of computer science and engineering approaches (e.g., machine learning), as some researchers have already begun to do (e.g. Kessler et al., 2015; Pestian et al., 2016; Walsh, Ribeiro, & Franklin, 2017). Machine learning may be particularly helpful with meaningfully integrating the many small to modest effects from risk factors and correlates observed in the field (Franklin et al., 2017).

Second, we encourage greater emphasis on the short-term prediction of suicidal thoughts and behaviours. There are several ways to achieve this, whether that is through sampling (e.g., large representative samples) or through the implementation of real-time monitoring with smaller high-risk samples (Glenn & Nock, 2014). Relevant to the latter, recent work in Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) suggests that monitoring suicidal thoughts multiple times a day shows the high variability and shown-term volatility of this clinical outcome, and the importance of monitoring risk factors within similar short-term time frames (Kleiman et al., 2017). The ubiquity of smartphone and mobile technology use introduces a rich source of real-time data that may also help identify a variety of short-term behavioural signatures of suicide risk (i.e., digital phenotyping; Torous, Staples, & Onnela, 2015).

4. Developmental sensitivity

Although many of the reviewed studies have examined the correlates of suicide risk among youth, they mostly fail to consider the developmental nature of suicide risk itself. Most of the studies reviewed here include either individuals under or over 18 years of age. This approach of grouping individuals into age categories obscures the contribution of normative developmental shifts to suicide risk. There is little to be said about patterns observed within a specific developmental period if not compared to or studied alongside comparison age groups. Practical issues such as subject recruitment severely limit progress that could be made by conducting studies examine risk that occurs as a function, in part, of the biopsychosocial transitions that accompany development.

Recommendations

First and foremost, more longitudinal studies that study novel psychobiological processes are needed. Within-person studies that emphasize variables which change over time may allow for a clearer understanding of the complex, interacting roles of biology and the environment in their prediction of suicide. Second, cross-sectional samples should include wider age ranges, preferably encompassing the typical developmental shifts that occur across age. The timing of pubertal transitions is a potentially critical consideration during adolescence, since for instance late puberty has been linked to greater likelihood of self-injury and suicide attempt even after adjusting for age and grade level (Patton et al., 2007). How or why this is the case (e.g., brain, endocrinological, physical changes) remains poorly understood (Patton & Viner, 2007).

5. Diversity