Abstract

Physical activity levels are related through algorithms to the energetic demand, with no information regarding the integrity of the multiple physiological systems involved in the energetic supply. Longitudinal analysis of the oxygen uptake (V̇o2) by wearable sensors in realistic settings might permit development of a practical tool for the study of the longitudinal aerobic system dynamics (i.e., V̇o2 kinetics). This study evaluated aerobic system dynamics based on predicted V̇o2 data obtained from wearable sensors during unsupervised activities of daily living (μADL). Thirteen healthy men performed a laboratory-controlled moderate exercise protocol and were monitored for ≈6 h/day for 4 days (μADL data). Variables derived from hip accelerometer (ACCHIP), heart rate monitor, and respiratory bands during μADL were extracted and processed by a validated random forest regression model to predict V̇o2. The aerobic system analysis was based on the frequency-domain analysis of ACCHIP and predicted V̇o2 data obtained during μADL. Optimal samples for frequency domain analysis (constrained to ≤0.01 Hz) were selected when ACCHIP was higher than 0.05 g at a given frequency (i.e., participants were active). The temporal characteristics of predicted V̇o2 data during μADL correlated with the temporal characteristics of measured V̇o2 data during laboratory-controlled protocol ( = 0.82, P < 0.001, n = 13). In conclusion, aerobic system dynamics can be investigated during unsupervised activities of daily living by wearable sensors. Although speculative, these algorithms have the potential to be incorporated into wearable systems for early detection of changes in health status in realistic environments by detecting changes in aerobic response dynamics.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY The early detection of subclinical aerobic system impairments might be indicative of impaired physiological reserves that impact the capacity for physical activity. This study is the first to use wearable sensors in unsupervised activities of daily living in combination with novel machine learning algorithms to investigate the aerobic system dynamics with the potential to contribute to models of functional health status and guide future individualized health care in the normal population.

Keywords: aerobic fitness, kinetics, machine learning, oxygen uptake, smart devices

INTRODUCTION

The oxygen uptake (V̇o2) dynamics (i.e., V̇o2 kinetics) during transition to a new metabolic demand require the complex integration between cardiovascular, respiratory, and muscular systems (6), and thus any alteration in V̇o2 dynamics may suggest a compromise in these systems. The study of the V̇o2 dynamics during unsupervised activities of daily living (μADL) has never been attempted. Recent algorithms have used various strategies to predict V̇o2 or to assess cardiorespiratory fitness in the laboratory and during free-living conditions. One approach incorporated nonlinear multivariable modeling and achieved good prediction of V̇o2 during randomly varying treadmill walking (31) but did not quantify dynamic responses and did not apply the model to μADL. Another approach relied on context-specific categorization of V̇o2 responses during simulated ADL (2). These previous models enabled the precise evaluation of physical activity (PA) levels through prediction of V̇o2 () data (2, 31). Although PA levels relate to the energetic demand throughout the day, they do not provide information regarding the integrity of the multiple physiological systems involved in the energetic supply. The longitudinal study of the aerobic system dynamics through data analysis in realistic settings may permit development of a practical tool with direct physiological significance to clinical outcomes (12, 23).

Wearable sensors (e.g., accelerometers) are often used to estimate PA levels based on V̇o2 steady-state response for each specific PA type (30). There is an association between the O2 cost (steady-state V̇o2) and the energetic demand that allows the energy expenditure estimation based on wearable sensors. However, during PA transitions, the aerobic response and, consequently, the V̇o2 dynamic lag behind the energetic demand (3). Nonetheless, it is during PA transitions, periods of high homeostatic perturbation, that the aerobic system demonstrates its integrity for the interactions with the external work. Classically, it is hypothesized that a faster aerobic adjustment to a new energetic demand is associated with a better aerobic fitness (24, 27, 28), whereas slower adjustments are associated with disease prognosis (8, 25, 29). The energetic supply during PA transitions relies more on anaerobic high-energy phosphate stores and glycolysis with lactate production when the aerobic responses are slower (14, 22), which might be associated with an increased perception of effort with consequences on functional mobility and performance (1).

The main objective of this study was to evaluate the aerobic system dynamics based on data obtained from wearable sensors during μADL. Specifically, data acquired from accelerometer, heart rate monitor, and respiratory bands during μADL were processed by a previously validated machine learning (ML) algorithm that predicts data (5). The aerobic system dynamics were characterized based on a parameter mean normalized gain (MNG) derived from frequency domain analysis of (6, 7) and compared with the MNG calculated from laboratory testing with directly measured V̇o2. The hypothesis of this study was that aerobic system dynamics based on data and derived from wearable sensors during μADL will be significantly correlated with directly measured aerobic system dynamics.

METHODS

Study design.

Thirteen healthy active men (26 ± 5.6 yr old, 179 ± 9 cm and 79 ± 13 kg) participated in this study. Written, informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was approved by the University of Waterloo Research Ethics Committee (ORE no. 20931), and the procedures were consistent with the Declaration of Helsinki. This longitudinal study was divided in two parts. The first part was comprised of data collection without supervision (μADL), where the participants wore sensors during their normal daily routine for 4 consecutive days. One participant wore the wearables for only 3 days. The researchers briefly met with the participant twice a day, at 9:52 ± 1:17 AM and 4:11 ± 1:21 PM, to install and remove the wearable sensors, respectively. Therefore, participants wore the sensors for 6.3 ± 1.4 h/day. Three additional participants (26 ± 1.2 yr old, 178 ± 4 cm and 89 ± 7 kg) started the protocol, but due to technical problems related to the respiratory bands and ECG electrodes, they were excluded from further analysis. From the 13 participants who completed the μADL analysis, 1.16 billion samples for each variable were analyzed.

In the second part of this study, the same participants that completed the first part of the study and that were reported elsewhere (5) walked and performed prescribed, simulated ADL while wearing the wearable sensors and a portable metabolic measurement system. The test protocol included two identical pseudorandom ternary sequence (PRTS) (21) over-ground walking protocols. Briefly, the PRTS protocol was generated by an algorithm composed by a shift register and an addition module, as described elsewhere (7, 26). The PRTS consisted of units that were 30 s in duration and three levels of walking cadence: 75, 105, or 135 steps/min. A metronome audio file was generated in Audacity 2.0.5 software (Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA) and used to control the walking cadence during the PRTS. The selected cadences were within the range of normal walking expected during ADL (5, 33). Between the two PRTSs, participants performed simulated ADL composed of sitting (≈10 min), organizing the shelf (≈5 min), carrying an object (≈5 min), stairs (≈5 min), and self-paced over-ground walking in different environments (≈15 min). From the PRTS and simulated ADL, wearable sensor data and directly measured V̇o2 were used to build an algorithm to obtain with a ML algorithm, as described previously (5) and further below. All 13 participants and three additional participants completed this part of the study.

Data collection.

For both study parts, participants wore the hip accelerometer, three-lead ECG electrodes, and two respiration bands that were integrated into a smart shirt (Hexoskin; Carré Technologies, Montréal, QC, Canada). From the sensor raw signals, previously validated (34) proprietary algorithms were used to obtain second-by-second heart rate (HR), minute ventilation (V̇e), breathing frequency (BF), total hip acceleration (ACCHIP), and walking cadence (CAD) data. Briefly, HR data were derived from an embedded smart shirt ECG system that collects signals from three electrodes at 256 Hz. The HR was averaged every 16 beats. A secondary variable, named ΔHR, was obtained by the difference between the current HR value and the previous value to capture the magnitude of changes in cardiac activity every second. Two strain gauge bands (abdomen and chest) based on inductance plethysmography were used to monitor respiration at 128 Hz. The V̇e was estimated from the magnitude of stretch of the gauge bands, and the BF was based on a peak detection algorithm. Both variables, V̇e and BF, were calculated as the average of the last seven respiration cycles. The ACCHIP was based on triaxial accelerometer signals located close to the hip. The triaxial signals (from the x-, y-, and z-axes) collected at 64 Hz, with a range of ± 16 g and resolution of 0.004 g, were combined by calculating the total vector magnitude following the equation as an indicator of the total hip acceleration. The feature CAD was also derived from the triaxial accelerometer signals by a proprietary step detection algorithm. All variables from this smart shirt were linearly interpolated on a second-by-second basis, recorded internally, and then uploaded for further analysis.

These features were considered in the algorithm described below to obtain at 1 Hz. For the simulated ADL part of this study, the V̇o2 data were measured breath by breath by a portable metabolic system (K4b2; COSMED) and expressed relative to each participant’s body mass in kilograms. Before each test, the air volume/flow and gas concentrations of the metabolic system were calibrated following manufacturer’s specifications.

Prediction algorithm.

The ML algorithms provide the technical basis to better identify nontrivial patterns in complex and intensive longitudinal data (37). The ML algorithm built to estimate was based on a random forest regression model (9). The HR data were also used to derive another feature, ΔHR, calculated as the difference between the current and previous HR values, with the intent of encoding temporal HR dynamics (5). All features (HR, ΔHR, V̇e, BF, ACCHIP, and CAD) and the V̇o2 data collected during the second part of this study were time aligned, low-pass filtered at 0.01 Hz, and processed in Matlab R2016a (MathWorks, Natick, MA). The V̇o2 predictor based on the features used in this study was described previously elsewhere (5). Briefly, this predictor was validated by leave-one-participant-out cross-validation (4), and the ensemble of random forest models was trained for optimal V̇o2 dynamics prediction using the mean response across all individual participant random forest predictions. Thus, the predictor algorithm differed from the previous report that investigated only individual predictive ability (5) in that the group ensemble was used to predict for all participants during μADL. The ML algorithm successfully predicted (high agreement and low bias) V̇o2 data during the PRTS and simulated ADL (part 2), allowing the further investigation of aerobic system dynamics. The Pearson coefficient () indicated a strong linear correlation between measured and predicted data for all 13 participants (r = 0.88 ± 0.03 and P < 0.001 for all participants). The mean of samples evaluated for each participant was 3,973 ± 215, and the prediction error bias was −0.007 ± 1.180 ml·min−1·kg−1. Figure 1 illustrates the ACCHIP, V̇o2, and (with error of estimation) obtained during part 2 (PRTS and simulated ) in a representative participant.

Fig. 1.

Hip acceleration (ACCHIP) and measured and predicted oxygen uptake (V̇o2) response of representative participants during 2 pseudorandom ternary sequence protocols (PRTS) separated by simulated activities of daily living (ADL). The error of estimation shows a small positive bias when predicted V̇o2 for this participant was derived on the basis of the ensemble averaged predictor algorithm.

Therefore, the single predictor algorithm was used to obtain based on the wearables-derived features during μADL, as illustrated for a single participant in Fig. 2 and displayed for all test sessions in Supplemental Figs. S1–S13 (Supplemental Material for this article is available at the Journal of Applied Physiology web site). When appropriate, the predicted metabolic equivalents () were estimated by the ratio/3.5.

Fig. 2.

The first 5 graphs (top to bottom) show representative responses of the features obtained from wearable sensors during the 1st day of unsupervised activities of daily living. The features derived from these sensors were heart rate (HR; A), ventilation minute (V̇e; B), breathing frequency (BF; C), hip acceleration (ACCHIP; D), and walking cadence (CAD; E). The predicted oxygen uptake (; F) was obtained by a machine learning algorithm based on these features streamed from wearable sensors throughout the day.

Data analysis.

Throughout the μADL, when the ACCHIP was >0.05 g, data were labeled as “active;” otherwise, they were “inactive.” When data were labeled as “active,” PA levels were classified as light, moderate, or vigorous in intensity when were <3, between 3.1 and 6, or >6.1, respectively (10). The time spent in each PA level was also computed.

Aerobic system analysis.

Previous analyses of aerobic system dynamics during randomly varying exercise loads under controlled laboratory conditions were based on the relationship between system input (i.e., PA) and the aerobic response inferred by V̇o2 data (i.e., system output) at different frequencies (6, 7, 18). Application of similar frequency domain methods to extract system dynamics during μADL requires some modifications and application of specific criteria. Following previous literature (17, 38), the amplitude (Amp) of the ACCHIP (system input) and the outputs (V̇o2 and ) were computed by fast Fourier transformation for a selected range of frequencies. The system gain was obtained by the (input Amp)/(output Amp) ratio. The selection of satisfactory energy delivered to the aerobic system for frequency domain analysis was also based on ACCHIP data. Low-energy stimulus does not allow the correct identification of the aerobic system gain, since the observed output response cannot be discerned from non-exercise-related factors that confound system analysis (7, 17). Because the focus of the frequency domain approach was aerobic system analysis, only ACCHIP Amp responses >0.05 g at a given frequency (7) were classified as “satisfactory” for system analysis; otherwise, they were “unsatisfactory” (as further described).

The selection of the frequency range of interest was based on previous studies (11, 13). To adhere to the linearity principle, the analyzed frequencies were limited to periods >100 s (i.e., ≤ 0.01 Hz). For frequencies >0.01 Hz, the V̇o2 dynamics complexity/noise appears to increase considerably (13), decreasing the physiological significance of the system responses. In addition to the detailed responses at different frequencies, the overall aerobic system temporal dynamics were assessed by the mean normalized gain (MNG), as reported previously (6, 7). Briefly, the MNG was calculated as the average of the gain Amp of all tested frequencies previously normalized by gain Amp of the very first frequency (11). Like time constants obtained in time domain analysis (15), MNG is an indicator of the overall aerobic system temporal dynamics, which seem to be related to aerobic power (7).

The data window length (wl) selected for the frequency domain analysis will define the number of harmonics (H) included within the selected frequency range (<0.01 Hz), since the fundamental frequency (f1) is the inverse of wl (21). Therefore, the frequency analyzed is defined by the product H × f1. Higher wl means a better frequency domain resolution due to a lower f1; therefore, more H can be included into the frequency interval. However, higher wl decreases the chance of having “satisfactory” samples for all tested frequencies (i.e.,ACCHIP <0.05 g) since the input energy is dissipated between H (21), which compromise the aerobic system analysis (17). In this study, the relationship between wl, H, f1, and the number of “satisfactory” samples will be further explored.

The ACCHIP response during PRTS was initially inspected as the stimulus signal in response to an optimized exercise protocol for frequency domain analysis. For this optimized protocol, the wl was equal to the exercise protocol duration (i.e, 780). Thus the f1 was 0.001 Hz. Figure 3 displays the ACCHIP group response in frequency domain during the PRTS protocol. As a characteristic of the PRTS protocol, and as we expected to observe in completely random stimulus (e.g., μADL), some input Amps in the PRTS protocol were below the satisfactory amount of energy necessary for system analysis. In the case of PRTS, even-numbered H presented “unsatisfactory” energy for system analysis (Fig. 3). In addition, PRTS protocols also stimulated the system with satisfactory energy in frequencies outside of the interval of interest (>0.01 Hz). From the PRTS ACCHIP responses in frequency domain, only the first four odd H could be labeled as “satisfactory” for system analysis between all participants.

Fig. 3.

Group response (means ± SD) of frequency domain amplitude (Amp) of the total hip acceleration (ACCHIP) during pseudorandom ternary sequence protocol. As a characteristic of this protocol, the stimulus energy decreases to values close to zero at even harmonics. For the correct system analysis, a range of frequencies and Amp was established (see gray area). Amp <0.05 g were considered unsatisfactory for system analysis. Frequencies >0.01 Hz were considered as nonlinear, and therefore, they were excluded from further analysis (see text).

In contrast to the first four odd H in PRTS protocols, the system input during μADL is not optimal for system analysis at these same frequencies. Therefore, further analysis was carried on to optimize the frequency domain analysis during μADL. With the minimal stimulus level (0.05 g) and frequency range (<0.01 Hz) established, the only variable that could be arbitrarily altered to optimize system analysis was wl. The f1 and H will change as a consequence of wl variations. Accordingly, the search for an optimal wl aimed to fit as many H as possible (higher resolution) within the frequency interval of interest, but at the same time all tested H needed to have “satisfactory” energy for system analysis.

As illustrated in Fig. 4, a certified (no. 100-314-4110) LabView-associated developer (National Instruments, Austin, TX) programmed an iterative algorithm that continuously computed Amp from multiple fast Fourier transformations on each of the 4 days separately from ACCHIP μADL data for each arbitrarily selected wl of 200 to 1,000 s incrementing by 100 s. The stepwise of each iteration was given by wl. The frequency range of interest was also maintained below 0.01 Hz. This program classified the samples at each frequency (H × f1) as “satisfactory” for system analysis when the ACCHIP Amp was >0.05 g. The Amp was simultaneously computed. Between each iteration, if more than one “satisfactory” Amp was found for the same frequency, the final Amp value was taken as the average between these Amp.

Fig. 4.

Illustration of 1 iteration of the computer program used to optimize the oxygen uptake dynamics assessment by frequency domain analysis during unsupervised activities of daily living of a representative participant (same as displayed in Fig. 1). A: data set of the system input [i.e., hip acceleration (ACCHIP)] during the 1st day of data collection. The gray area in A has a duration defined by the window length (wl) variable and defines the data window plotted in B and C. This data selector scrolls through the entire data plotted in A (demonstrated by the arrow). B: selected time series data of ACCHIP. C: selected time series data of the system output (i.e., predicted oxygen uptake). D and E: data from B and C displayed in the frequency domain. F: system gain in frequency domain calculated by the ratio between the data displayed in D and E. ●, Satisfactory samples for frequency domain analysis in D–F; ○, unsatisfactory samples. Satisfactory samples were selected according to the value of the data displayed in D, where samples with amplitude >0.05 g (dashed line) were classified as satisfactory for system analysis (see text).

Figure 5A displays the mean group response ( = 13 for each data point) of the number of “satisfactory” samples (z-axis) at each tested frequency (x-axis) as a function of wl (y-axis). The plot was superimposed by a mesh plot for better pattern visualization. As the wl increased, the number of analyzed frequencies (i.e., resolution) increased (more data in x-axis); however, the number of samples with enough energy for system analysis decreased (z-axis). On the other hand, shorter wl presented more “satisfactory” samples for system analysis but at the same time less resolution (fewer frequencies analyzed). In addition, for all selected wl, more “satisfactory” samples are located at lower frequencies.

Fig. 5.

A: mean group response (n = 13 for each data point) of the no. of satisfactory samples for system analysis in frequency domain (z-axis) at each tested frequency (x-axis) as a function of data window length (wl; y-axis) during 4 days of unsupervised activities of daily living. B: no. of participants who did not present a satisfactory stimulus for system analysis in at least 1 tested frequency as a function of wl.

Figure 5B demonstrates the number of participants who did not present “satisfactory” Amp for system analysis in at least one tested frequency, thus precluding a comparable aerobic system analysis. Below a wl of 600 s, all participants presented “satisfactory” ACCHIP Amp for all tested H. Therefore, based on ACCHIP data, the wl of 600 s was selected as an optimal wl for system analysis during μADL. For the sake of data comparison between μADL and PRTS stimulus, the final Amp responses were linearly interpolated to a common frequency bandwidth of 0.0022 to 0.0088 Hz with a step increment of 0.0002 Hz, totaling 35 interpolated H for μADL and PRTS. The MNG was also calculated during μADL and PRTS considering this interval.

Statistical analysis.

Data were represented as means ± SD. To test the influence of PA over the variables, the variable value was taken as the mean values at each condition (“active” or “inactive”) for each participant. Paired t-test was used to compare variables between conditions. Student’s t-test was used to compare the MNG computed from V̇o2 or from during the PRTS protocol (part 2). The MNG estimated from V̇o2 or from during PRTS was also compared with the MNG estimated from during μADL by Student’s t-test. When appropriate, Pearson correlation r, linear regression, Bland-Altman plot, and 95% confidence interval (CI95) were used to compute the level of agreement between variables.

RESULTS

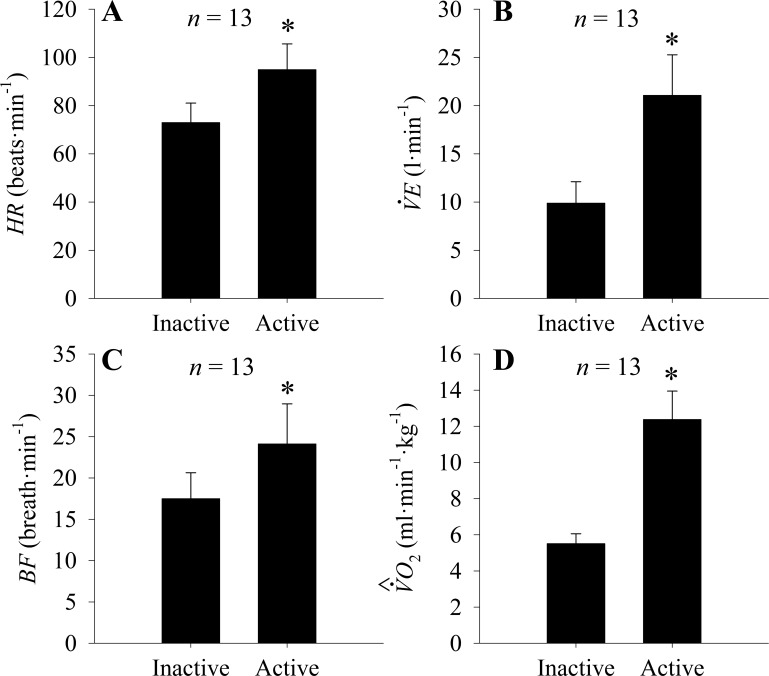

The mean ± SD of the variables HR, V̇e, BF, and when “active” or “inactive” during μADL are displayed in Fig. 6. The HR (Fig. 6A) increased from 72.9 ± 8.1 beats/min while inactive to 94.9 ± 10.6 beats/min during active periods (P < 0.05). Likewise, V̇e (Fig. 6B) increased with activity from 9.8 ± 2.2 to 21.0 ± 4.1 l/min, and BF (Fig. 6C) increased from 17.4 ± 3.1 breaths/min to 24.1 breaths/min during PA (P < 0.05). The more than doubled from 5.5 ± 0.5 to 12.3 ± 1.5 ml·min−1·kg−1 during active periods of μADL (P < 0.05; Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6.

Means ± SD of heart rate (HR; A), ventilation minute (V̇e; B), breathing frequency(BF; C), and predicted oxygen uptake (; D) during unsupervised activity of daily living. Data were clustered between inactive and active groups based on hip accelerometer.

The average walking bout duration was 24 ± 7 s. Participants spent ≈80% of the time being inactive (Fig. 7). When active, ≈90% of the μADL was light- or moderate-intensity PA (<6 ). In 50% of the active time, participants were walking as categorized by the cadence detection algorithm of the wearable sensor. The majority of the walking bouts (≈80%) were contained in moderate-intensity domain.

Fig. 7.

Identification of physical activity patterns during 4 days of unsupervised activities of daily living. A: %time spent being active or inactive. B: when active, %time spent within each physical activity intensity domain (light, moderate, or vigorous).

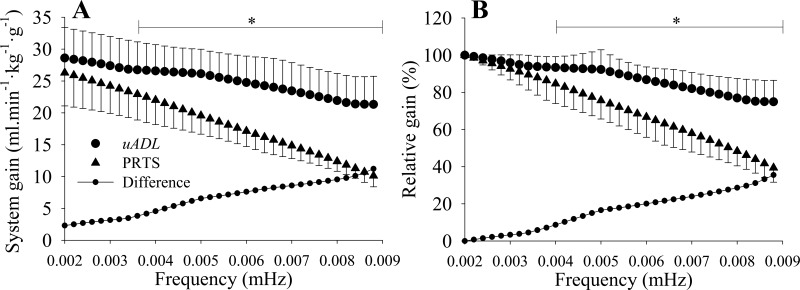

The frequency domain analysis during μADL considered a wl of 600 s. For a better comparison between μADL and PRTS, the responses from both inputs were interpolated at a common bandwidth of 0.0020 to 0.0088 Hz (period of 113 to 500 s). Figure 8A displays the system gain analyzed during μADL and PRTS and the difference between them at each frequency. After frequencies >0.0036 Hz (or H = 9), the system gains were statistically (P < 0.05) higher during μADL in comparison with PRTS. When the system was normalized by the first analyzed frequency (H = 1 or 0.0020 Hz) that isolated the temporal dynamics of the system (6, 7, 13), the normalized gains (Fig. 8B) were statistically (P < 0.05) higher at frequencies >0.004 Hz (H = 11). Notice that the difference between the system of absolute or normalized gain during μADL and PRTS linearly increased as the frequency increased.

Fig. 8.

A: aerobic system gains assessed as aerobic power per unit of hip acceleration (ml·min−1·kg−1·g−1) at different frequencies based on predicted oxygen uptake in the same 13 participants during unsupervised activities of daily living (μADL) and based on measured oxygen uptake during pseudorandom ternary sequence (PRTS) walking protocol. The gain during μADL was statistically higher than the gain during PRTS after 0.0036 Hz. B: aerobic system normalized gain (see text). The normalized gain during μADL was statistically higher than the gain during PRTS after 0.004 Hz. *P < 0.05.

The MNG, an index of overall aerobic system temporal dynamics (6), was calculated based on data presented in Fig. 8B by the average between all Amp gains previously normalized by the Amp gain of the first frequency. The MNG computed from measured V̇o2 during PRTS was not statistically different (P = 0.53) from but was correlated (r = 0.68, P = 0.01, n = 13) with MNG estimated from during PRTS. As depicted in Fig. 9A, the MNGs calculated from V̇o2 during PRTS (ideal protocol) and from during μADL were strongly correlated (r = 0.82, P < 0.001 and n = 13), but the MNG was statistically (P < 0.001) higher (i.e., faster) when calculated from during μADL. However, the linear regression between the MNG obtained from the V̇o2 during PRTS and the MNG obtained from during μADL had a slope of 1.003, which was similar to the expected slope of the equality line, indicating a linear bias of ≈16%. The CI95 of the difference between the MNG obtained from the V̇o2 data during PRTS and the MNG obtained from during μADL was 8% (Fig. 9B).

Fig. 9.

A: linear correlation between the mean normalized gain (MNG) calculated from predicted oxygen uptake data () during unsupervised activities of daily living (μADL) and calculated from measured oxygen uptake (V̇o2) data during pseudorandom ternary sequence (PRTS) walking protocol. The difference between the estimates of MNG with the 2 methods (16%) was consistent across the participants characterized by a similar linear regression slope in comparison to the equality line. B: Bland-Altman plot of the data displayed in A with the bias and the confidence interval (CI95) between the 2 methods used to estimate MNG.

DISCUSSION

The current study has shown that aerobic system dynamics could be successfully mined from wearable sensors that provide continuous data for physical activity, breathing, and heart rate during unsupervised activities of daily living. Consistent with the hypothesis, the temporal characteristics extracted from the predicted oxygen uptake data () during activities of daily living were strongly correlated with the temporal characteristics of the measured oxygen uptake data (V̇o2) during a controlled protocol. In addition, the provided sensitive assessments of light-, moderate-, and vigorous-intensity physical activities throughout daily activities. That is, the combined information from has the potential to evaluate daily levels of physical activity as a reflection of a healthy lifestyle (32) and assess changes in aerobic system dynamics as an index of cardiorespiratory fitness and overall health (12, 23). Further studies should extend this approach to different populations, such as unhealthy subjects, to test whether the estimated MNG can be used as a reliable index of aerobic system kinetics. This study demonstrated the methods that might be used to extract information with clinical relevance from wearable technologies, but more experiments are necessary to predict and test health status.

Previous research (2) demonstrated that V̇o2 can be estimated during exercise transitions based on wearable sensors. However, the aerobic system dynamics were not systematically evaluated or validated. More recently, we reported (5) the ability of machine learning algorithms to predict the aerobic system temporal dynamics from wearable sensors during an exercise protocol composed exclusively by transitions as in the PRTS testing in part 2 of the current study. The novel aspect of the current study was the development of a methodology to accurately predict V̇o2 signals during transitions encountered in μADL and utilize these data to extract aerobic system temporal dynamics, increasing the potential for clinical applications of wearable sensors. It is well known that the temporal characteristics of the aerobic system have clinical significance (8, 19, 35), and for the first time, it was evaluated outside of laboratory confinements without controlled protocols.

In contrast to step-work rate laboratory-based studies, the randomness characteristics of PA patterns during μADL complicates the process of obtaining information with clinical significance. Time domain V̇o2 data modeling is not practical during μADL due to the lack of steady-state responses, which decreases the signal-to-noise ratio, thus preventing calculation of the system temporal dynamics (15).

The first critical step in the analysis was determination of the data window size (wl) for frequency domain analysis. For the young healthy participants of the current study, we found that a data window of 600 s can be used to extract information regarding the aerobic system temporal dynamics based on predicted data. Because the system analysis quality also depends on the number of analyzed frequencies, the data window size (wl) should be as large as possible. However, the larger the data window size, the greater the chance to present unreliable samples for system analysis. As depicted in Fig. 4, a window size of 600 s was found to be ideal for aerobic system analysis.

The observed higher percent MNG during the μADL, as opposed to the PRTS protocol (Fig. 9), technically reflects faster kinetics of the overall aerobic system dynamics (6, 7). It is important to consider the origin of the different responses of the dynamics indicators in the same individuals with the different exercise conditions. The strong linear correlation between MNG values for the two conditions could originate from the prediction algorithm or from biological variability. There are a few observations that allow us to rule out the first possibility. First, for data from the PRTS protocol, the MNG computed from was strongly correlated with and not statistically different from the MNG based on measured V̇o2 during the same PRTS testing session. In addition, the MNG computed from during PRTS was correlated with the MNG calculated from during μADL, but they were statistically different, suggesting that the observed difference did not originate from the predictor but from biological variability between PRTS and μADL.

The origin of the biological variability for system analysis during μADL might relate to the frequent occurrence of rest-to-exercise transitions. Previous research has shown faster kinetics for V̇o2 during transitions from rest to exercise (16). Although a contributing factor to the faster V̇o2 kinetics is the more rapid increase in heart rate from a resting baseline (16), there is a corresponding metabolic basis, as indicated by corresponding muscle phosphocreatine kinetics (20). Significantly for rest-to-exercise transitions in the analysis of MNG in the current study, the frequency range investigated was constrained to frequencies <0.01 Hz to exclude so-called cardiodynamic contributions at the onset of exercise (36). In this study, the MNG during PRTS was used only as a reference to check whether the MNG estimated from μADL was also able to detect different aerobic system temporal dynamics, which was the case. Therefore, participants who presented faster aerobic dynamics during PRTS also presented a faster adjustment during μADL.

The MNG is an index composed of an amalgamated response of components with variable speeds (6) that translated the overall aerobic system temporal dynamic and seemed to have clinical relevance (7). The MNG obtained during μADL was calculated based on the mean of multiple “satisfactory” samples at each frequency, whereas the MNG estimated from during PRTS was based on a single sample for each frequency, which might explain why the MNG calculated from data during μADL was better correlated with the MNG estimated from during PRTS in comparison with the MNG estimated from during PRTS.

Our novel methodology is a combination of four main components. 1) Machine learning was used for V̇o2 data prediction based on wearable sensors to address the complexities of the V̇o2 response to ADL. 2) fast Fourier transformation was used for aerobic system analysis, as it has intrinsic noise reduction characteristics and allows for a detailed investigation of the aerobic response during different stimulus periods. 3) The MNG calculation was used to obtain the temporal dynamics of the aerobic system based on the fast Fourier transformation results. 4) An iterative algorithm was developed to search for the best data window for the investigation of the aerobic system dynamics during completely random physical activities.

Results from our work have suggested specific methods for the use of our model in evaluating aerobic system temporal dynamics during μADL. Standard algorithms need to be developed to transform the raw signals from wearable sensors into the initial model input variables (e.g., HR). These variables then feed the machine learning algorithm (random forests) that will generate the predicted V̇o2. The input (ACCHIP) and the output (predicted V̇o2) can then be used to calculate the aerobic system gain based on fast Fourier transformation calculations. As shown for healthy active men recruited for this study, the most appropriate data window length used for each fast Fourier transformation was 600 s, and gain should be computed and recorded only when the ACCHIP is >0.05 g. The frequency range should be limited to 0.01 Hz. The average is calculated if more than one reading is made for the same frequency. After 4 days, the MNG is computed based on the normalized system gain. This 4-day data processing cycle can be repeated as often as necessary to account for changes in MNG.

Further epidemiological studies are necessary to investigate the relationship between the aerobic system temporal dynamics with different PA patterns during realistic settings. These investigations would enable the identification of sedentary or active behaviors that are correlated with different aerobic system dynamics that might impact PA recommendations.

Conclusion.

For the first time, this study has shown that aerobic system dynamics can be investigated during unsupervised activities of daily living by wearable sensors. The longitudinal frequency domain analysis of predicted oxygen uptake derived from wearables allowed the characterization of the temporal dynamics of the aerobic system during realistic activities, thus demonstrating the effectiveness of our method to track changes in aerobic fitness, such as might happen with physical training or detraining, illness, or aging during μADL by wearable sensors. We identified reliable samples for aerobic system analysis from the 20% of the data when the participants were active during μADL.

Deployment of nonintrusive technologies in conjunction with the algorithms developed in the current study into large scale epidemiological investigations may offer the unique opportunity of investigating relationships between patterns of daily physical activity and health/fitness indicators.

GRANTS

This study was funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) to R. L. Hughson (RGPIN-6473), the Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation/Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico to T. Beltrame (202398/2011-0), NSERC CGSD3-441805-2013 and AGE-WELL NCE (AW-HQP2015-23) to R. Amelard, and in part by the Canada Research Chairs program to A. Wong.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

T.B., R.A., A.W., and R.L.H. conceived and designed research; T.B., R.A., A.W., and R.L.H. performed experiments; T.B., R.A., A.W., and R.L.H. analyzed data; T.B., R.A., A.W., and R.L.H. interpreted results of experiments; T.B., R.A., A.W., and R.L.H. prepared figures; T.B., R.A., A.W., and R.L.H. drafted manuscript; T.B., R.A., A.W., and R.L.H. edited and revised manuscript; T.B., R.A., A.W., and R.L.H. approved final version of manuscript.

Supplemental Data

Supplemental Figures S1-S13

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexander NB, Dengel DR, Olson RJ, Krajewski KM. Oxygen-uptake (VO2) kinetics and functional mobility performance in impaired older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 58: M734–M739, 2003. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.8.M734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altini M, Penders J, Amft O. Estimating oxygen uptake during nonsteady-state activities and transitions using wearable sensors. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform 20: 469–475, 2016. doi: 10.1109/JBHI.2015.2390493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barstow TJ, Buchthal S, Zanconato S, Cooper DM. Muscle energetics and pulmonary oxygen uptake kinetics during moderate exercise. J Appl Physiol (1985) 77: 1742–1749, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beltrame T, Amelard R, Villar R, Shafiee MJ, Wong A, Hughson RL. Estimating oxygen uptake and energy expenditure during treadmill walking by neural network analysis of easy-to-obtain inputs. J Appl Physiol (1985) 121: 1226–1233, 2016. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00600.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beltrame T, Amelard R, Wong A, Hughson RL. Prediction of oxygen uptake dynamics by machine learning analysis of wearable sensors during activities of daily living. Sci Rep 7: 45738, 2017. doi: 10.1038/srep45738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beltrame T, Hughson RL. Linear and non-linear contributions to oxygen transport and utilization during moderate random exercise in humans. Exp Physiol 102: 563–577, 2017. doi: 10.1113/EP086145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beltrame T, Hughson RL. Aerobic system analysis based on oxygen uptake and hip acceleration during random over-ground walking activities. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 312: R93–R100, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00381.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borghi-Silva A, Beltrame T, Reis MS, Sampaio LMM, Catai AM, Arena R, Costa D. Relationship between oxygen consumption kinetics and BODE Index in COPD patients. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 7: 711–718, 2012. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S35637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Breiman L. Random forests. Mach Learn 45: 5–32, 2001. doi: 10.1023/A:1010933404324. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crouter SE, Dellavalle DM, Horton M, Haas JD, Frongillo EA, Bassett DR Jr. Validity of the Actical for estimating free-living physical activity. Eur J Appl Physiol 111: 1381–1389, 2011. doi: 10.1007/s00421-010-1758-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eβfeld D, Hoffmann U, Stegemann J. A model for studying the distortion of muscle oxygen uptake patterns by circulation parameters. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 62: 83–90, 1991. doi: 10.1007/BF00626761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guazzi M, Adams V, Conraads V, Halle M, Mezzani A, Vanhees L, Arena R, Fletcher GF, Forman DE, Kitzman DW, Lavie CJ, Myers J; European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation; American Heart Association . EACPR/AHA Scientific Statement. Clinical recommendations for cardiopulmonary exercise testing data assessment in specific patient populations. Circulation 126: 2261–2274, 2012. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31826fb946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffmann U, Eβfeld D, Wunderlich HG, Stegemann J. Dynamic linearity of VO2 responses during aerobic exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 64: 139–144, 1992. doi: 10.1007/BF00717951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hughson RL. Exploring cardiorespiratory control mechanisms through gas exchange dynamics. Med Sci Sports Exerc 22: 72–79, 1990. doi: 10.1249/00005768-199002000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hughson RL. Oxygen uptake kinetics: historical perspective and future directions. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 34: 840–850, 2009. doi: 10.1139/H09-088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hughson RL, Morrissey MA. Delayed kinetics of VO2 in the transition from prior exercise. Evidence for O2 transport limitation of VO2 kinetics: a review. Int J Sports Med 4: 31–39, 1983. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1026013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hughson RL, Winter DA, Patla AE, Swanson GD, Cuervo LA. Investigation of VO2 kinetics in humans with pseudorandom binary sequence work rate change. J Appl Physiol (1985) 68: 796–801, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hughson RL, Xing HC, Borkhoff C, Butler GC. Kinetics of ventilation and gas exchange during supine and upright cycle exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 63: 300–307, 1991. doi: 10.1007/BF00233866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones AM, Mark B. Oxygen uptake kinetics: an underappreciated determinant of exercise performance. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 4: 524–532, 2009. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.4.4.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones AM, Wilkerson DP, Fulford J. Muscle [phosphocreatine] dynamics following the onset of exercise in humans: the influence of baseline work-rate. J Physiol 586: 889–898, 2008. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.142026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kerlin TW. Frequency Response Testing in Nuclear Reactors. New York: Academic Press, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koskolou MD, Calbet JA, Rådegran G, Roach RC. Hypoxia and the cardiovascular response to dynamic knee-extensor exercise. Am J Physiol 272: H2655–H2663, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newman AB, Simonsick EM, Naydeck BL, Boudreau RM, Kritchevsky SB, Nevitt MC, Pahor M, Satterfield S, Brach JS, Studenski SA, Harris TB. Association of long-distance corridor walk performance with mortality, cardiovascular disease, mobility limitation, and disability. JAMA 295: 2018–2026, 2006. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norris SR, Petersen SR. Effects of endurance training on transient oxygen uptake responses in cyclists. J Sports Sci 16: 733–738, 1998. doi: 10.1080/026404198366362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pessoa BV, Beltrame T, Di Lorenzo VA, Catai AM, Borghi-Silva A, Jamami M. COPD patients’ oxygen uptake and heart rate on-kinetics at cycle-ergometer: correlation with their predictors of severity. Braz J Phys Ther 17: 152–162, 2013. doi: 10.1590/S1413-35552012005000073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peterka RJ. Sensorimotor integration in human postural control. J Neurophysiol 88: 1097–1118, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Phillips SM, Green HJ, MacDonald MJ, Hughson RL. Progressive effect of endurance training on VO2 kinetics at the onset of submaximal exercise. J Appl Physiol (1985) 79: 1914–1920, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Powers SK, Dodd S, Beadle RE. Oxygen uptake kinetics in trained athletes differing in VO2max. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 54: 306–308, 1985. doi: 10.1007/BF00426150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Regensteiner JG, Bauer TA, Reusch JE, Brandenburg SL, Sippel JM, Vogelsong AM, Smith S, Wolfel EE, Eckel RH, Hiatt WR. Abnormal oxygen uptake kinetic responses in women with type II diabetes mellitus. J Appl Physiol (1985) 85: 310–317, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Staudenmayer J, Pober D, Crouter S, Bassett D, Freedson P. An artificial neural network to estimate physical activity energy expenditure and identify physical activity type from an accelerometer. J Appl Physiol (1985) 107: 1300–1307, 2009. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00465.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Su SW, Celler BG, Savkin AV, Nguyen HT, Cheng TM, Guo Y, Wang L. Transient and steady state estimation of human oxygen uptake based on noninvasive portable sensor measurements. Med Biol Eng Comput 47: 1111–1117, 2009. doi: 10.1007/s11517-009-0534-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tremblay MS, Warburton DER, Janssen I, Paterson DH, Latimer AE, Rhodes RE, Kho ME, Hicks A, Leblanc AG, Zehr L, Murumets K, Duggan M. New Canadian physical activity guidelines. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 36: 36–46, 2011. doi: 10.1139/H11-009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tudor-Locke C, Rowe DA. Using cadence to study free-living ambulatory behaviour. Sports Med 42: 381–398, 2012. doi: 10.2165/11599170-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Villar R, Beltrame T, Hughson RL. Validation of the Hexoskin wearable vest during lying, sitting, standing, and walking activities. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 40: 1019–1024, 2015. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2015-0140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Whipp BJ, Ward SA. Pulmonary gas exchange dynamics and the tolerance to muscular exercise: effects of fitness and training. Ann Physiol Anthropol 11: 207–214, 1992. doi: 10.2114/ahs1983.11.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Whipp BJ, Ward SA, Lamarra N, Davis JA, Wasserman K. Parameters of ventilatory and gas exchange dynamics during exercise. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol 52: 1506–1513, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Witten IH, Frank E. Data Mining: Practical machine learning tools and techniques. San Francisco, CA: Elsevier, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoshida T, Abe D, Fukuoka Y, Hughson RL. System analysis for oxygen uptake kinetics with step and pseudorandom binary sequence exercise in endurance athletes. Meas Phys Educ Exerc Sci 12: 1–9, 2008. doi: 10.1080/10913670701715133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figures S1-S13