Abstract

Background/Aims

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) is a severe blinding condition. We investigated whether retinal metabolism, measured by retinal oximetry, may predict PDR activity after panretinal laser photocoagulation (PRP).

Methods

We performed a prospective, interventional, clinical study of patients with treatment-naive PDR. Wide-field fluorescein angiography (OPTOS, Optomap) and global and focal retinal oximetry (Oxymap T1) were performed at baseline (BL), and 3 months (3M) after PRP. Angiographic findings were used to divide patients according to progression or non-progression of PDR after PRP. We evaluated differences in global and focal retinal oxygen saturation between patients with and without progression of PDR after PRP treatment.

Results

We included 45 eyes of 37 patients (median age and duration of diabetes were 51.6 and 20 years). Eyes with progression of PDR developed a higher retinal venous oxygen saturation than eyes with non-progression at 3M (global: +5.9% (95% CI –1.5 to 12.9), focal: +5.4%, (95% CI –4.1 to 14.8)). Likewise, progression of PDR was associated with a lower arteriovenular (AV) oxygen difference between BL and 3M (global: –6.1%, (95% CI –13.4 to –1.4), focal: –4.5% (95% CI –12.1 to 3.2)). In a multiple logistic regression model, increment in global retinal venular oxygen saturation (OR 1.30 per 1%-point increment, p=0.017) and decrement in AV oxygen saturation difference (OR 0.72 per 1%-point increment, p=0.016) at 3M independently predicted progression of PDR.

Conclusion

Development of higher retinal venular and lower AV global oxygen saturation independently predicts progression of PDR despite standard PRP and might be a potential non-invasive marker of angiogenic disease activity.

Keywords: neovascularisation, treatment lasers, imaging

Introduction

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a leading cause of blindness in the working-age population globally.1–3 Proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) is an ischaemic end-stage complication characterised by new retinal vessels (proliferations) that often lead to vitreous haemorrhage and/or tractional retinal detachment. The Diabetic Retinopathy Study demonstrated that panretinal laser photocoagulation (PRP) reduces the risk of severe visual loss by 57% in patients with high-risk PDR.4 The purported mechanism of PRP has been debated for decades, but a general hypothesis is that energy delivered by the laser is absorbed by the retinal pigment epithelium and transformed to heat energy conducted to the neurosensory part of the retina, leading to thermic destruction of the affected retinal areas, which reduces the hypoxic load.4–6 While PRP is now considered standard of care for PDR, PRP is a global retinal treatment with little intra-individual variation. The inability to accurately predict progression of disease after PRP is partly because all patients are given the same amount of laser treatment. Some patients may have insufficient treatment while excessive treatment has been given to others. Hence, some might have disease progression with recurrent vitreous haemorrhage, and others may develop side effects like visual field loss, night blindness or diabetic macular oedema.5–7

The level of retinal metabolism may be an indicator of disease activity after PRP. This can be non-invasively measured by retinal oxygen saturation using a spectrophotometric retinal oximeter,8 and increasing levels of DR has been associated with increased retinal venular oxygen saturation.9–12 Hence, retinal oxygen saturation could act as an early indicator of PRP treatment response, and thereby be a valuable tool in the individualised patient management. In order to test if optimal levels of PRP can be assessed preoperatively, the main aim of this study was to investigate if retinal oximetry prior to PRP could be used as a non-invasive marker of postoperative PDR activity.

Materials and methods

We carried out a 3-month prospective, interventional study of 45 treatment-naive eyes with PDR referred to Odense University Hospital, Denmark between 1 August 2014 and 31 October 2015. We excluded patients with clinical significant macular oedema, previous PRP in the study eye, treatment-demanding cataract, age <18 years or pregnancy.

At baseline (BL), all patients provided a full medical history (including type of diabetes) and underwent a standard ophthalmic examination including slit lamp examination performed in mydriasis with tropicamide 10 mg/mL (Mydriacyl) and Phenylephedrine 10% (Metaoxedrin), optical coherence tomography (OCT) by 3D OCT-2000 Spectral domain OCT (Topcon, Tokyo, Japan), and widefield fluorescein angiography (Optomap; Optos, Dunfermline, Scotland, UK). All examinations were done by trained personnel.

BL examinations included blood pressure (BP) on the upper arm using BP measuring equipment (Omron 705CP, Hoofdrop, The Netherlands), haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) and retinal oximetry (Oxymap model T1, Oxymap, software V.2.4.2, Reykjavik, Iceland).

Patients then received PRP in two sessions, 1 week apart by a navigated laser system (Navilas, OD-OS GmbH, Berlin, Germany). The patients were given a local anaesthetic (oxybuprocaine hydrochloride 0.4%), and a Navilas 34 mm or 38 mm contact lens was used. All treatments were given by certified personnel (TLT and JG), and treatment specifications were automatically provided by the laser system after each session.

Follow-up was performed 3 months (3M) after PRP. Progression of PDR were defined as formation of new retinal proliferations, increased area of one or more proliferations or increased area of fluorescein leakage on angiography, as defined by clinical guidelines. Eyes with progression received supplementary PRP as needed, after follow-up examinations had been performed.

Retinal oxygen saturation

Oxymap T1 was used to assess the retinal oxygen saturation (figure 1). The equipment and technique are described elsewhere.13 All gradings were masked according to the PDR activity at follow-up and done by a single trained grader (TLT) in accordance with a prespecified grading protocol. Optic disc centred images were used for grading. Two rings were semi-automatically placed around the optic disc. The inner ring was manually placed between 20 and 30 pixels from the edge of the optic disc to avoid erroneous measurements due to reflection from the optic disc and the surrounding nerve fibre layer. The outer ring was automatically placed at three times the diameter of the inner ring. The oximetry measurements were done between the inner and outer ring. One larger arteriole and venule in each quadrant were automatically traced at a length of 50–200 pixels. If the length of the vessel was less than 50 pixels proximal to the first branching point, the first branch vessel was chosen for tracing. Measurements at follow-up were done on the same vessel segment. Two methods were used: Global measurements were defined as the mean retinal arteriolar and venular oxygen saturation of all four quadrants, and focal measurements were calculated as the retinal arteriolar and venular oxygen saturation of the affected retinal quadrant in patients with only one neovascularisation elsewhere. In addition to the arteriolar and venular measurements, the arteriovenular (AV) difference was included in the analysis.

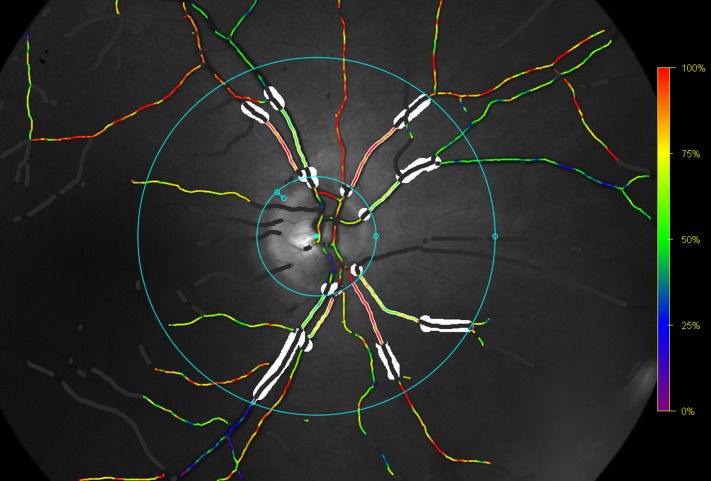

Figure 1.

Retinal oxygen saturation. Oxymap T1 image showing traced vessels with overlaying colour map indicating oxygen saturation by colour on right eye. The oxygen saturation is measured in traced vessels, seen as white lines on either side of the vessels, between the blue rings. Retinal vessels covered in white areas are excluded vessel segments.

Approvals

The study was approved by the Regional Scientific Ethics Committee (ID S-20140046), The Danish Data Protection Agency (ID 14/16546), registered at Clinical Trials on the fourth of June 2014 (ID NCT02157350), and performed in accordance with the criteria of the Helsinki II Declaration and good clinical practice. All patients gave informed consent before inclusion in the study. Furthermore, we attest that we have obtained appropriate permissions and paid any required fees for use of copyright-protected materials.

Statistical analyses

All statistical calculations were performed using STATA V.14.1 (StataCorp), and p values under 0.05 were considered statistically significant. At BL, categorical data are presented as percentage and continuous data as median with interquartile range (9IQR. Differences between patients with progression and non-progression of PDR were compared by the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous data and χ2 for categorical data. Multiple logistic regression was performed with retinal oximetry measurements as predictors for progression of PDR (with adjustments for sex, age, duration of diabetes, HbA1c, systolic and diastolic BP and retinal laser energy). A standard power calculation on the arteriolar and venular oxygen saturation stated the inclusion of minimum 27 patients in the study (arteriolar: α 5%, β 20%, mean 92.2, difference 2, spread 3.7, n=27, venular: α 5%, β 20%, mean 55.6, difference 3.5, spread 6.3, n=26).

Results

A total of 45 eyes (37 patients) were examined. Nineteen patients had type 1 and 18 had type two diabetes. At BL, there was no significant difference in the retinal oxygen saturation between patients with type 1 and type two diabetes (arteriolar 96.1% vs 97.0%, p=0.79 venular 64.4% vs 67.9%, p=0.17), and therefore the data was merged.

The age and duration of diabetes (median and IQR) was 51.6±15 and 20±11 years, and 64% were male. HbA1c was 7.9%±1.5% (63±16 mmol/mol), and the median and IQR BP was 153±37/83.5±21 mm Hg. Retinal arteriolar and venular oxygen saturation was 96.3%±7.2% and 67.2%±13.6%, respectively.

At baseline in global as well as focal analysis, patients with and without progression of PDR did not differ according to age, duration of diabetes, HbA1c, BP, total laser energy delivered, retinal oximetry image quality or retinal oxygen saturation (arteriolar, venular and arteriovenular difference) (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics according to activity of proliferative diabetic retinopathy at follow-up month 3

| Baseline characteristics | Global (median±IQR) | Focal (median±IQR) | ||||

| PDR progression | PDR non-progression | p value | PDR progression | PDR non-progression | p value | |

| Eyes, n | 12 | 30 | 7 | 17 | ||

| Sex (men/women), n | 6/6 | 22/8 | 0.15 | 3/4 | 14/3 | 0.05 |

| Age, years | 51.3±18.0 | 53.8±26.0 | 0.47 | 51.1±31.7 | 42.3±21.8 | 0.97 |

| Diabetes duration, years | 15.5±22.5 | 20±12.0 | 0.28 | 12±8.0 | 20±12.0 | 0.07 |

| HbA1c, % | 8.2±2.4 | 7.9±1.5 | 0.96 | 8.4±2.8 | 7.8±1.2 | 0.43 |

| HbA1c, mmol/mol | 66.5±26.5 | 63±16.0 | 0.96 | 68±31.0 | 62±13.0 | 0.43 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 159.5±29.5 | 153±39.0 | 0.99 | 146±37.0 | 140±29.0 | 0.97 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 77.5±28.0 | 83.5±12.0 | 0.44 | 83±28.0 | 82±14.0 | 0.82 |

| Amount of laser energy, Joule | 13.8±5.0 | 13.2±4.6 | 0.56 | 13.6±6.7 | 11.5±4.1 | 0.68 |

| Oximetry image quality, 0–10 | 8.4±1.2 | 8.0±1.0 | 0.51 | 8.3±1.2 | 8.1±0.9 | 0.85 |

| Arteriolar oxygen saturation, % | 96.1±7.8 | 95.3±7.8 | 0.43 | 93.6±8.1 | 97.6±9.0 | 0.32 |

| Venular oxygen saturation, % | 65.2±16.3 | 67.2±13.4 | 0.96 | 62.0±18.6 | 68.2±14.2 | 0.59 |

| Arteriovenular oxygen difference saturation, % | 31.9±14.1 | 30.2±11.1 | 0.58 | 28.5±24.0 | 34.6±20.6 | 0.36 |

Baseline characteristics in global and focal measurements according to activity of proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) 3 months after panretinal laser photocoagulation. Continuous data are presented as median with IQR. Differences between groups were compared with the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous data and χ2 test for categorical. Oximetry image quality ranged from 0=poor to 10=excellent.

IQR, interquartile range; PDR, proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

Between BL and 3M, three eyes were excluded due to vitrectomy (n=2) or death (n=1), leaving a total of 42 eyes for global measurements and 24 for focal measurements. At 3M for global measurements, 12 eyes had progression of PDR as opposed to 30 eyes that did not progress. Correspondingly, in focal measurements, progression and non-progression of PDR was found for seven and 17 eyes, respectively.

Retinal arteriolar oxygen saturation

In global as well as focal measurements, there was no difference in retinal arteriolar oxygen saturation between the two groups, neither at BL, 3M or in the differences between BL and 3M (figure 2, figure 3, figure 4, figure 5 and table 2).

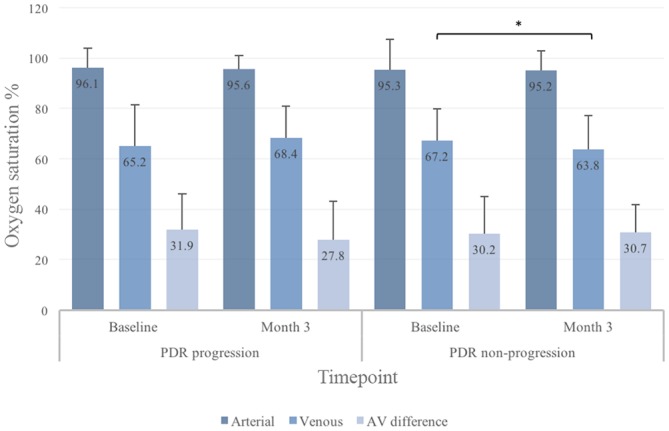

Figure 2.

Global retinal oxygen saturation in eyes with progression or non-progression of proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) before and after panretinal laser photocoagulation. All values are given as median with inter quartile range (IQR). AV, arteriovenular. *Statistically significant.

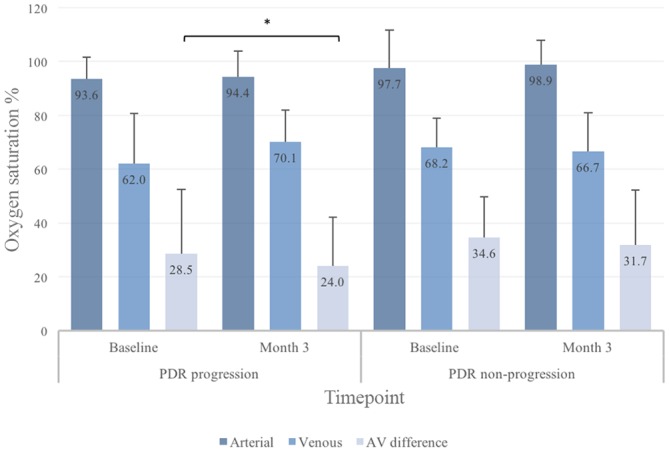

Figure 3.

Focal retinal oxygen saturation in eyes with progression or non-progression of proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) before and after panretinal laser photocoagulation. All values are given as median with interquartile range (IQR). AV, arteriovenular. *Statistically significant.

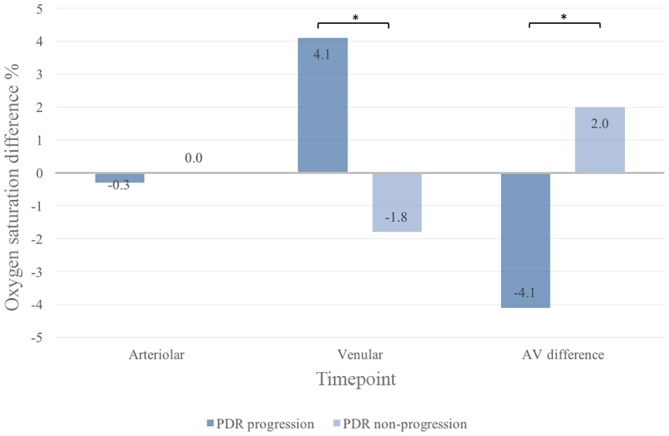

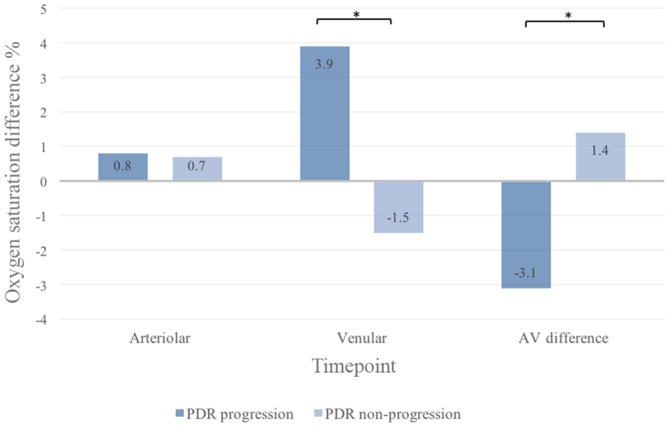

Figure 4.

Difference in global retinal oxygen saturation from baseline to follow-up in eyes with proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) according to disease activity at follow-up. All values are given as median. AV, arteriovenular. *Statistically significant.

Figure 5.

Difference in focal retinal oxygen saturation from baseline to follow-up in eyes with proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) according to disease activity at follow-up. All values are given as median. AV, arteriovenular. *Statistically significant.

Table 2.

Risk of progression of proliferative diabetic retinopathy after panretinal laser photocoagulation according to global and focal retinal oxygen saturation

| Month 3 | Baseline | Month 3 | Difference (month 3–baseline) | ||||

| Increment | OR (95% CI) | p value | OR (95% CI) | p value | OR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Global (n=42) | |||||||

| Arteriolar | 1.0% | 1.07 (0.92 to 1.24) | 0.376 | 1.08 (0.91 to 1.27) | 0.386 | 0.98 (0.77 to 1.26) | 0.892 |

| Venular | 1.0% | 0.99 (0.89 to 1.10) | 0.885 | 1.12 (0.98 to 1.28) | 0.087 | 1.30 (1.05 to 1.62) | 0.017* |

| Arteriovenular | 1.0% | 1.05 (0.94 to 1.18) | 0.390 | 0.95 (0.85 to 1.05) | 0.320 | 0.72 (0.55 to 0.94) | 0.016* |

| Focal (n=24) | |||||||

| Arteriolar | 1.0% | 0.86 (0.65 to 1.14) | 0.285 | 0.98 (0.83 to 1.15) | 0.768 | 1.30 (0.81 to 2.01) | 0.274 |

| Venular | 1.0% | 0.90 (0.75 to 1.09) | 0.290 | 1.00 (0.86 to 1.16) | 0.980 | 1.33 (0.88 to 1.99) | 0.173 |

| Arteriovenular | 1.0% | 1.02 (0.88 to 1.19) | 0.756 | 0.99 (0.86 to 1.13) | 0.835 | 0.89 (0.68 to 1.15) | 0.360 |

Multiple logistic regression model (adjusted for age, sex, duration of diabetes, HbA1c, and amount of laser energy) indicating risk of progression of proliferative diabetic retinopathy 3 months after panretinal laser photocoagulation according to level of retinal oxygen saturation at baseline, follow-up and between baseline and follow-up. Risk indicated as odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). *Statistically significant.

Retinal venular oxygen saturation

There was a decrease in global retinal venular oxygen saturation between BL and 3M in patients without progression of PDR (67.2% vs 63.8%, p=0.04) (figure 2). Likewise, at 3M, patients with progression of PDR had developed a higher difference in retinal venular oxygen saturation than patients without progression of PDR (+4.1% vs −1.8%, p=0.02) (figure 4). In a multiple logistic regression model, an increase in global retinal venular oxygen saturation between BL and 3M was independently associated with progression of PDR (OR 1.30 per 1%-point increment, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.62, p=0.02) (table 2).

In the focal retinal venular oxygen measurements, there were no differences between BL and 3M between groups (figure 3), but at 3M, patients with progression of PDR had a higher increment from BL than patients without progression (+3.9% vs −1.5%, p=0.04) (figure 5).

Retinal AV oxygen difference

In the global measurements, the retinal oxygen saturation AV difference between patients with progression and non-progression of PDR differed at 3M (progression −4.1% vs non-progression +2.0, p<0.01) (figure 4). This was confirmed in the multiple logistic regression analysis (OR for progression of PDR 0.72 per 1.0%-point increment in AV difference, 95% CI 0.55 to 0.94, p=0.02) (table 2).

In the focal analysis, a decrease in AV difference was seen between BL and 3M in patients with progression of PDR (28.5% vs 24.0%, p=0.03) (figure 3). There was also a different AV difference between patients with and without progression of PDR from BL to 3M (−3.1% vs +1.4, p<0.04) (figure 5).

Discussion

In this prospective study of patients with treatment-naive PDR, prelaser retinal oxygen saturation was not able to predict postoperative disease activity. However, the study also demonstrates postoperative changes in the retinal oxygen metabolism that were closely linked to disease activity 3 months after PRP. In fact, each 1% increase in retinal venular oxygen saturation was independently associated with a 30% higher risk of increased PDR activity despite laser treatment.

It has consistently been demonstrated that patients with DR have higher retinal venular oxygen saturation as compared with healthy controls.9 11 12 14 Likewise, the retinal arteriolar and venular oxygen saturation increases with increasing levels of DR.10 11 The paradoxical difference between the high intravascular oxygen saturation and the ischaemic retinal tissue has been hypothesised to be caused by oxygen entrapment due to capillary closure, blood shunting around non-perfused retinal areas, thickening of the capillary vessel walls, and greater affinity of haemoglobin for oxygen in patients with diabetes.11 An earlier study by Hammer et al demonstrated a trend towards lower retinal venular oxygen saturation in patients with PDR previously treated with PRP as compared with treatment-naive patients.12 In the present study, we demonstrated that this finding was only present in patients who were stabilised after PRP. This identifies retinal oxygen saturation as a non-invasive marker of disease activity, and might be of assistance to clinicians in the postoperative phase.

The retinal AV oxygen difference is considered as a pseudo-indicator of retinal oxygen consumption.11 In the present study, each 1%-point increase in the retinal AV oxygen difference between BL and 3M independently reduced the risk of progression of PDR by 28%, thereby indicating higher retinal oxygen use for those patients with a favourable treatment response. One explanation to the differences in retinal venular and AV oxygen saturation seen may be found in the hypoxic areas of the retina. These areas represent oxygen deficit tissue that react by increasing their retinal oxygen demand. This increase in oxygen demand causes the retinal oxygen saturation to increase, which unfortunately does not aid the hypoxic areas due to the overall poor condition of the capillaries. When successful PRP treatment is obtained, the hypoxic tissue is adequately decreased in area, thereby decreasing the retinal oxygen demand and lowering the venous and AV oxygen saturation.

We did not find the same differences in the arteriolar oxygen saturation. Earlier studies have shown a large difference in reported retinal arteriolar oxygen saturation as compared with the venules,11 12 15 and this was the case despite a general higher retinal arteriolar oxygen saturation in patients with PDR.9 10 16 This variation in reported retinal arteriolar oxygen saturation could be due to variance in laser treatment or oxygen saturation measurement protocols or equipment. Likewise, there could be a ceiling effect for arteriolar values that would not be present for venular measurements.

DR has traditionally been considered a global retinal ischaemic disease. However, some patients only have local lesions and may represent more focal phenotypes. In the present study, 24 patients only had a single proliferation elsewhere. For these patients, we were able to replicate the global oximetry findings with higher retinal venular oxygen saturation and lower AV differences at follow-up for patients with progression of PDR. Even though these findings are limited by a low number of patients in this subgroup, the focal findings should raise the question of a possible retained ischaemic overdrive in the retinal quadrant with the proliferation. Previous studies on healthy individuals have found regional differences in the retinal oxygen saturation, although the same difference has not been shown in patients with PDR.17 18 These regional differences could explain why we did not find a difference in the oxygen saturation between the quadrant containing a proliferation and the oxygen saturation of the three adjacent quadrants (data not shown). Upcoming studies should address the possibility of a more focal treatment for patients with focal ischaemia.

Limitations of the study need to be considered. This includes a limited number of patients, which could affect the outcome of the study, although the power calculation was respected. An untreated observation group would have strengthened the study, but this was not possible due to ethical reasons. Furthermore, a trend towards a skewed distribution of women was seen in the focal measurements at 3M. This may have confounded the interpretation of the focal results. Finally, retinal blood flow analyses were not included in the study.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that in patients with treatment-naive PDR, the retinal oxygen saturation cannot be used as a preoperative indicator of treatment outcome, but that the postoperative retinal oxygen metabolism closely reflects the disease activity and, hence, may be used to assess the need of adjunctive laser therapy. Upcoming studies should address if less invasive treatment of patients with focal PDR have the same efficacy but fewer side effects than standard-of-care PRP.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Velux foundation and the Region of Southern Denmark for the financial support for this study. We also thank the Department of Ophthalmology, Odense University Hospital for providing the facilities and equipment necessary.

Footnotes

Contributors: JG conceived the aims and overall design of the study. TLT acquired the data and did the writing of the different sections, tables and figures. JG and TLT did the literature search and statistical analyses. All authors were involved in the study design, data analyses, data interpretation and revision of the paper. The following authors had access to the full raw dataset: TLT and JG. The corresponding author had the final responsibility to submit for publication.

Funding: The funders (the Velux Foundation and the Region of Southern Denmark) had no influence on the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation of the data or writing of the report.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The Regional Scientific Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Ting DS, Cheung GC, Wong TY. Diabetic retinopathy: global prevalence, Major risk factors, screening practices and public health challenges: a review. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2016;44:260–77. 10.1111/ceo.12696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Klein R, Lee KE, Gangnon RE, et al. The 25-year incidence of visual impairment in type 1 diabetes mellitus the Wisconsin epidemiologic study of diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmology 2010;117:63–70. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.06.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Liew G, Michaelides M, Bunce C. A comparison of the causes of blindness certifications in England and Wales in working age adults (16-64 years), 1999-2000 with 2009-2010. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004015 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Preliminary report on effects of photocoagulation therapy. the Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group. Am J Ophthalmol 1976;81:383–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Early photocoagulation for diabetic retinopathy. ETDRS report number 9. early treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group. Ophthalmology 1991;98(5 Suppl):766–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Photocoagulation treatment of proliferative diabetic retinopathy. clinical application of Diabetic Retinopathy Study (DRS) findings, DRS Report Number 8. the Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group. Ophthalmology 1981;88:583–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ferris FL, Podgor MJ, Davis MD. Macular edema in Diabetic Retinopathy Study patients. Diabetic Retinopathy Study Report Number 12. Ophthalmology 1987;94:754–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hardarson SH, Harris A, Karlsson RA, et al. Automatic retinal oximetry. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2006;47:5011–6. 10.1167/iovs.06-0039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jørgensen CM, Hardarson SH, Bek T. The oxygen saturation in retinal vessels from diabetic patients depends on the severity and type of vision-threatening retinopathy. Acta Ophthalmol 2014;92:34–9. 10.1111/aos.12283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Khoobehi B, Firn K, Thompson H, et al. Retinal arterial and venous oxygen saturation is altered in diabetic patients. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2013;54:7103–6. 10.1167/iovs.13-12723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hardarson SH, Stefánsson E. Retinal oxygen saturation is altered in diabetic retinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol 2012;96:560–3. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hammer M, Vilser W, Riemer T, et al. Diabetic patients with retinopathy show increased retinal venous oxygen saturation. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2009;247:1025–30. 10.1007/s00417-009-1078-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Geirsdottir A, Palsson O, Hardarson SH, et al. Retinal vessel oxygen saturation in healthy individuals. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2012;53:5433–42. 10.1167/iovs.12-9912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rilvén S, Torp TL, Grauslund J. Retinal oximetry in patients with ischaemic retinal diseases. Acta Ophthalmol 2017;95 10.1111/aos.13229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Man RE, Sasongko MB, Xie J, et al. Associations of retinal oximetry in persons with diabetes. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2015;43:124–31. 10.1111/ceo.12387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jørgensen C, Bek T. Increasing oxygen saturation in larger retinal vessels after photocoagulation for diabetic retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2014;55:5365–9. 10.1167/iovs.14-14811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jørgensen CM, Bek T. Lack of differences in the regional variation of oxygen saturation in larger retinal vessels in diabetic maculopathy and proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol 2017;101 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2016-308894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Heitmar R, Safeen S. Regional differences in oxygen saturation in retinal arterioles and venules. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2012;250:1429–34. 10.1007/s00417-012-1980-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]