Abstract

Exosomes are one of the most potent intercellular communicators, which are able to communicate with adjacent or distant cells. Exosomes deliver various bioactive molecules, including membrane receptors, proteins, mRNA and microRNA, to target cells and serve roles. Recent studies have demonstrated that exosomes may regulate the functions and diseases of the skin, which is the largest organ of the human body. The abnormal functions of the skin lead to the progression of scleroderma, melanoma, baldness and other diseases. A previous study has demonstrated that epithelial progenitor cells are rich in several subunits of exosomes that may maintain the proliferative capacity of these epithelial progenitor cells, which is essential for the development of the epidermis. Exosomes derived from human adipose mesenchymal stem cells accelerate skin wound healing by optimizing fibroblast properties; this is beneficial for the recovery of postoperative and other wounds. Exosomes derived from adipocytes promote melanoma migration and invasion through fatty acid oxidation; therefore, in the clinic, it may be possible to improve the prognosis of patients with melanoma by reducing their body fat content. Exosomes derived from keratinocytes modulate melanocyte pigmentation, which has been utilized as a novel mechanism for the regulation of pigmentation in conditions including Moynahan syndrome and albinism. Meanwhile, scleroderma patients with vascular abnormalities may experience decreased serum exosome levels; it may therefore be possible to detect the exosome content in sera in order to diagnose and treat scleroderma. In addition, the use of exosomes has been suggested to promote or enhance hair growth, which has been demonstrated to be highly effective. These studies have provided new opportunities and therapeutic strategies for understanding how exosomes regulate intercellular communication in pathological processes of the skin.

Keywords: exosomes, skin, function, disease

1. Introduction

Skin refers to an organization of tissues on the surface of the body and is the largest organ of the human body, accounting for 16% of the body weight (1). Skin is the physical, chemical and immunological barrier of organisms. Thus, skin prevents the loss of useful substances from an organism. Skin also undertakes various functions, including repairing itself, perspiring, detecting temperature and pressure, and providing additional structural support (2–4). The development and function of the skin are affected by multiple factors, including environmental factors and hormones (5). Recently, exosome studies have indicated that some exosomes are involved in the physiological and pathological processes of the skin (6,7). Such findings have provided a novel perspective for the understanding of the molecular mechanisms involved in these processes.

Exosomes are small cell-derived vesicles (~100 nm in diameter) that are found in the majority of, if not all, biological fluids (8). Exosomes originate from endosomes and deliver various bioactive molecules to target cells (9). The recognition of exosomes by target cells is a specific, and involves the following events: i) Recognition between surface receptors; ii) direct fusion of the exosome with target cell membrane; and iii) ingestion by the target cell through endocytosis (10). They are important mediators of cell-to-cell communication, which is involved in multiple processes, including the immune response, apoptosis, angiogenesis and inflammation (11). Cells secrete exosomes that present signal molecules to nearby or distant tissues or cells, serving a regulatory role (12). To date, the mechanism of action of exosomes is poorly understood. Therefore, further studies are required to determine how exosomes regulate skin diseases and functions.

To date, studies on exosomes have become gradually applicable in clinical practice. For instance, exosome mRNA may be used as a diagnostic marker for lung cancer (13), exosome-derived glutathione peroxidase 1 may restore hepatic oxidant injury (14), and exosomal glypican 1 and its regulatory miRNAs may be specific markers for the detection and targeted therapy of colorectal cancer (15). With further study, the clinical applications of exosome markers may be increased.

2. Skin

The skin is a complex structure composed of multiple cell types and proteins, which comprise the epidermis, dermis and subcutaneous tissue (3). Skin is the indispensable barrier between the organism and the environment. Barrier function is an irreplaceable function of the skin (16), and the skin contains various accessory organs (17). There are multiple types of cells that secrete exosomes in the skin, for example keratinocytes, fibroblasts and adipocytes secrete exosomes into other cells or body fluids to participate in biological activity (6,18,19).

Skin diseases, including viral dermatosis, fungal dermatosis, connective tissue disease, pigmented dermatosis and skin tumors, are among the most common diseases in humans (20,21). Damage to the physiological function and normal structure of the skin may lead to skin diseases (22). Understanding the pathogenesis of various types of skin diseases may contribute to the establishment of effective therapeutics. Therefore, more research should focus on ways to prevent and treat skin diseases. Various studies have identified an association between exosomes and skin diseases (23–25). For instance, melanoma cells secrete exosomes, which are abundant in the tumor microenvironment, to impact on the pathological process (26).

3. Biological characteristics of exosomes

Exosomes are a kind of 40–100-nm biological membrane-bound structure, which are secreted by a variety of cells, including hematopoietic cells, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), adipocytes, keratinocytes and tumor cell lines, and released into the extracellular environment (27). Exosomes are widely distributed in body fluids (blood, urine and breast milk) (28). In 1983, Pan and Johnstone (29) first discovered exosomes in mammalian reticulocytes from mature sheep.

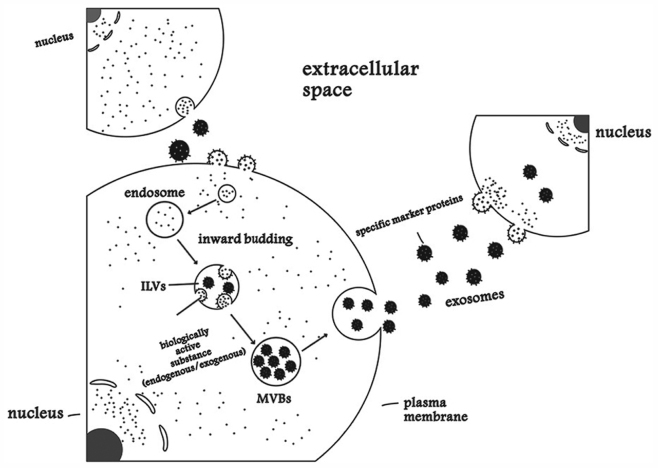

The origin of the exosomes is endocytosis (30). The inward budding of endosomes produces intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) that accumulate to form multivesicular bodies (MVBs). MVBs fuse with the plasma membrane, then release ILVs into the extracellular space or biological fluids (31,32). This process of exosome formation is depicted in Fig. 1. Exosomes may be internalized by target cells to participate in various physiological or pathological processes (33). Exosomes have multiple specific marker proteins, including membrane transport and fusion proteins (GTPases, annexins and flotillin), tetraspannins (34), heat shock proteins (Hsps; heat shock cognate 70 and Hsp90), proteins involved in MVB biogenesis (Alix and tumor susceptibility gene 101 protein), as well as lipid-related proteins and phospholipases (35).

Figure 1.

Process of exosome formation. ILVs, intraluminal vesicles; MVBs, multivesicular bodies.

Exosomes derived from different cells or tissues have varying functions. A previous study on exosomes demonstrated that they were associated with cellular functions and disease states (36). Research has investigated the relationship between exosomes and the immune response (37). For example, exosomes released by stem cells have been indicated to contribute to the treatment of autoimmune diseases (38). Alloreactive T cells may be activated by the exosomes secreted by donor dendritic cells (39). Furthermore, the roles of exosomes in cancer have been reported. Cancer-associated fibroblast-derived exosomes have been demonstrated to alter the metabolic mechanism of tumor cells (40). High-grade ovarian cancer cells secrete effective exosomes that serve an influential role in tumor angiogenesis (41). Tumor cell-derived exosomes are involved in tumor progression by multiple mechanisms, including proliferation, invasion, immunosuppression and formation of the premetastatic niche (42). For instance, tumor cell-derived exosomes are able to destroy the host immune system, and enhance tumor cell survival, growth and migration (43).

In addition, exosomes contain biologically active substances, including proteins, mRNA, microRNA (miRNA), cytokines and transcription factors (44). miRNA, single-chain and non-coding RNA with a length of 18–25 nt, regulate gene expression at the post-transcriptional level (45). miRNA interact with mRNA and have been indicated to degrade target mRNA or inhibit target mRNA translation (7). A single miRNA may regulate several target mRNA, and multiple miRNA may also bind to one target mRNA (46). Increasing evidence suggests that miRNA serve a critical role in multiple biological functions (47). Exosomes derived from MSCs attenuate renal fibrosis via miRNA let7c (48). Adipose tissue-derived MSC exosomes enhance hepatocellular carcinoma chemosensitivity by delivering miRNA-122 to the tumor cells (49). miRNA-9 and miRNA-124 of exosomes released into the serum may be utilized as biomarkers for acute ischemic stroke and to evaluate the degree of damage caused by ischemic injury (50). However, in the present review, the predominant focus will be on the regulation of skin functions and diseases by exosomes. These physiological and pathological processes in which exosomes are involved are outlined in Table I.

Table I.

Functions of exosomes in skin physiological and pathological processes.

| Author, year | Process | Function | Source of exosomes | Mechanism of action | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mistry et al, 2012 | Skin development | Epidermal growth | Epidermal progenitor cells | Decrease expression of grainyhead like transcription factor 3 | (53) |

| Lim et al, 2013 | Skin development | Hair growth | Stem cells | Prepare pharmaceutical composition | (59) |

| Lo Cicero et al, 2015 | Skin pigmentation | Pigmentation of melanocyte | Keratinocyte | Carry miRNA target to melanocytes | (6) |

| Liu et al, 2016 | Skin pigmentation | Vitiligo pathogenesis | Serum of patients | miRNA carried by exosomes induce differential expression | (23) |

| Li et al, 2016 | Skin wound healing | Skin wound healing | Human endothelial progenitor cells | Enhance proliferation, migration, tube formation and angiogenesis | (64) |

| Zhang et al, 2015 | Skin wound healing | Skin wound healing | Human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived MSCs | Enhance proliferation, migration, tube formation and angiogenesis | (63) |

| Hu et al, 2016 | Skin wound healing | Skin wound healing | Adipose MSCs | To obtain excellent fibroblasts | (24) |

| Zhao et al, 2017 | Skin wound healing | Skin wound healing | Human amniotic epithelial cells | Promote proliferation and migration of fibroblasts | (66) |

| Zhang et al, 2015 | Skin wound healing | Skin wound healing | Human umbilical cord MSCs | Activation of β-catenin via the Wnt4 pathway | (67) |

| Nakamura et al, 2016 | Skin wound healing | Skin wound healing | Serum | Impact on collagen synthesis | (68) |

| Hood et al, 2011 | Skin cancer | Melanoma pathogenesis | Melanoma cells | Encourage angiogenesis to promote growth of the tumor | (75) |

| Ekström et al, 2014 | Skin cancer | Melanoma pathogenesis | Melanoma cells | Mediated by Wnt signaling to enhance tumor invasion and migration | (76) |

| Hood, 2016 | Skin cancer | Melanoma pathogenesis | Melanoma cells | Damage tumor immune surveillance function in lymph nodes | (77) |

| Felicetti et al, 2016 | Skin cancer | Melanoma pathogenesis | Melanoma cells | miRNA-222 activates the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AKT pathway to promote tumorigenesis | (7) |

| Alegre et al, 2014 | Skin cancer | Melanoma pathogenesis | Melanoma cells | miRNA-125b regulates the expression of c-Jun protein | (81) |

| Languino et al, 2016 | Skin cancer | SCC | SCC tumor microenvironment | Re-activate TGF-β signal | (84) |

| Jelonek et al, 2015 | Skin cancer | SCC | Head and neck SCC cells | Have a response to ionizing radiation | (85) |

| Nakamura et al, 2016 | Other skin diseases | Scleroderma | Serum of patients | Disturb exosome transport | (68,87) |

| Gutiérrez-Ramos et al, 2008 | Other skin diseases | Dermatomyositis and scleroderma syndrome | Serum of patients | Acts as an autoantigenic complex | (89) |

| Ferrante et al, 2015 | Other skin diseases | Obesity | Adipocytes | Regulate TGF-β and Wnt/β-catenin signaling | (92) |

| Lazar et al, 2016 | Other skin diseases | Obesity | Adipocytes | Involved in fatty acid oxidation | (95) |

| Zhang et al, 2017 | Other skin diseases | Obesity | Adipose tissue | Induce adipogenesis | (93) |

miRNA, microRNA; MSC, mesenchymal stem cell; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β; SSC, squamous cell carcinoma.

4. Exosomes and skin development

The development of the skin, particularly the epidermis, is essential for the survival of organisms. If the epidermis cannot be sufficiently self-renewed and differentiated, it may lead to a variety of skin diseases (51). Balance between this self-renewal and differentiation needs to be regulated by progenitor and stem cells (52). A previous study demonstrated that subunits of the exosomes (EXOSC7, EXOSC9 and EXOSC10) are abundant in epidermal progenitor cells, and are essential to avoid premature differentiation of progenitor cells (53), the mechanism for which may involve reduced production of grainyhead like transcription factor 3, a transcription factor essential for epidermal differentiation, through targeted degradation of its mRNA (53,54).

Wnt signaling pathways serve an important role in various developmental processes, such as the self-renewal of mammalian skin or tissue (55). A previous study identified that Wnt proteins are transported through the exosomes (56). Wnt induces the activation of β-catenin in endothelial cells by exosomes, thus promoting skin repair (57).

Hair of humans is the role of necessity and metabolism, and its predominant function is for warmth in mammals. Androgenetic alopecia is a common chronic skin condition that leads to hair loss in humans (58). A patented clinical study suggested that a pharmaceutical composition prepared by using exosomes may promote or enhance hair growth, making the hair thicker and longer. The exosomes were secreted by stem cells, such as MSCs (59).

5. Exosomes and skin pigmentation

The occurrence and mechanisms of skin and hair color development in mammals and humans are complicated and affected by multiple factors. Pigmentation is the core of the process, and is predominantly regulated by α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone/melanocortin 1 receptor, mitogen-activated protein kinase (stem cell factor/c-Kit), eosinophil-derived neurotoxin and the Wnt signaling pathway (60). Skin pigmentation requires close communication between cells. In the skin epidermis, melanocytes and keratinocytes form the epidermal melanin unit (6). Ultraviolet B is able to induce melanin production in melanoma cells (6). The difference in skin color is controlled by the melanin content (61). Abnormal skin pigmentation may lead to hyper and hypopigmentation disorder; a study by Lo Cicero et al (6) recently indicated that human keratinocyte-derived exosomes carry specific miRNA (miRNA-3196 and miRNA-203) and target melanocytes to regulate pigmentation, through the alteration of gene expression and the activation of key enzymes.

Vitiligo is a common pigmentation disorder of the skin, caused by the loss of functional melanocytes (62). The data presented in a previous study demonstrated that exosomes isolated from sera of active vitiligo patients differentially expressed 47 miRNA compared with healthy controls (23). This indicated a difference in the miRNAs between the serum exosomes of patients with vitiligo and those of healthy individuals, and contributed to understanding the role of melanocytes in the pathogenesis of vitiligo. Such research may allow for the development of a novel approach to manipulate pigmentation via exosomes, including crosstalk between melanocytes and keratinocytes, and the pathogenesis of abnormal pigment disorders.

6. Exosomes and skin wound healing

Previous studies, listed below, have indicated that exosomes promote skin wound healing through a paracrine mechanism, and suggest that the principal mechanism depends on the source of the exosomes. However, cells derived from different sources, including adipose mesenchymal cells and human amniotic epithelial cells, have demonstrated similar characteristics to MSCs (63). Exosomes of endothelial progenitor cells from human umbilical cord blood may also accelerate skin wound healing (64). Exosomes released from human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived MSCs have the ability of tissue repair by promoting collagen synthesis and angiogenesis (63). Similarly, exosomes secreted by cardiosphere-derived cells contribute to scar reduction (65).

In addition, adipose MSC-derived exosomes (ASCs-Exos) are internalized by fibroblasts to influence cell migration, proliferation and collagen synthesis (24). Histological analyses have indicated that the effect of ASCs-Exos on collagen is different between the early and later stages of wound healing, with increased collagen I and III synthesis at early stages and decreased collagen synthesis at later stages (24). ASCs-Exos may also promote cutaneous wound healing via optimizing the properties of fibroblasts (24). Human amniotic epithelial cell-derived exosomes have been demonstrated to expedite wound healing and inhibit scar formation by promoting proliferation and migration of fibroblasts (66). Human umbilical cord MSC-derived exosomes (hucMSC-Exos) through the Wnt4 pathway are also involved in skin wound healing. HucMSC-Exos facilitate the function of endothelial cells; various studies have demonstrated that the hucMSC-Exo-mediated Wnt4 pathway induced β-catenin activation in endothelial cells and enhanced vascular regeneration (57,67). Furthermore, research has suggested that exosomes from the serum may accelerate wound healing in mice, predominantly due to the impact on collagen synthesis (68).

At present, the most notably obstacle in the treatment of skin wounds is how to prolong healing, particularly in the cases of wound recovery in diabetic patients and patients who have received surgery. Therefore, exosomes may provide a promising approach for skin wound repair.

7. Exosomes and skin cancer

Skin cancer is a common disease and the morbidity is increasing dramatically, particularly in Caucasians. For example, the incidence of skin cancer among Caucasians in America reached 165 per 10,000 individuals in 2015 (69,70). Skin cancers include melanoma, basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC); the latter two diseases are non-melanoma (69). Tumor cell-derived exosomes are abundant in the tumor microenvironment; they contribute to the formation of the premetastatic niche and attack the host's immune system (26). Exosomes may be used as an effective tool in cancer diagnosis and prognosis due to their particular pro-tumorigenic characteristics (25).

Melanoma, also known as malignant melanoma, forms through malignant transformation of melanocytes and often occurs in the skin. Melanoma is the most malignant tumor of the skin tumors (71). Due to the aggressiveness, ease of distant metastasis and treatment resistance, melanoma has a high mortality rate (72–74). Early diagnosis and treatment is therefore particularly important.

A study by Hood et al (75) demonstrated that melanoma exosomes induced different patterns in the sentinel lymph node genes, which was dependent on the establishment of the angiogenesis mode of the matrix structure. This was conducive to the growth of the tumor. In melanoma cells, Wnt5A strengthens the capacity of invasion and metastasis by inducing the immunomodulatory and pro-angiogenic factors released from exosomes (76). Melanoma exosomes may promote the ability of lymph node tumor tolerance mediated by myeloid-derived suppressor cells and lymphatic endothelial cells, which leads to damage to the function of tumor immune surveillance in lymph nodes (77).

Previous studies have indicated that miRNA are also closely related to melanoma (7,78–80). For instance, melanoma cells secrete exosomes carrying miR-222 to promote tumorigenesis by activating the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AKT pathway (7). The expression level of miRNA-125b was downregulated in serum exosomes of patients with melanoma compared with the levels in healthy individuals. miRNA-125b is a characteristic miRNA from melanoma-derived exosomes, which may directly inhibit the expression of c-Jun protein and control the development of melanoma (81). miRNA-17, −19a, −21, −126 and −149 were highly expressed in the exosomes of patients with metastatic sporadic melanoma compared with the levels in patients with familial melanoma and normal controls. Notably, there was no significant difference in the miRNA expression level between the healthy controls and the patients with familial melanoma (82).

Non-melanoma, predominantly SCC, may use exosomes to increase crosstalk between tumor cells and the tumor microenvironment (83). Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signaling is important for cancer occurrence and development. It has been demonstrated that exosomes in the tumor microenvironment have the ability to re-activate TGF-β signaling in SSC (84). Exosomes secreted from head and neck SCC cells change their protein composition in response to ionizing radiation, which may induce changes in translation or transcription (85). Relevant research data has indicated that the exosomes of head and neck SCC cells also promote the survival of recipient cells (83).

In summary, exosomes serve an important role in the occurrence and development of tumors. Full elucidation of the mechanism of exosome function is conducive to the diagnosis and treatment of skin cancer.

8. Exosomes and other skin diseases

Scleroderma is a connective tissue disease, and its main features include endothelial cell dysfunction, immune activation and excessive skin fibrosis (86). A previous study demonstrated that patients with scleroderma had a reduced level of exosomes in their serum, which was predominantly due to vascular abnormalities disrupting the transportation of exosomes derived from the fibrocytes of skin tissue (68,87). However, in dermatomyositis and scleroderma overlap syndrome, exosomes exist as an autoantigenic complex (88,89).

Another disease associated with skin is obesity. Obesity is a common metabolic syndrome and a systemic inflammatory state that affects almost every organ system in the body (90). Adipocytes of people with obesity may induce inflammation (91). Fortunately, adipocyte-derived exosomes may carry miRNA to regulate end-organ TGF-β and Wnt/β-catenin signaling, which are inflammatory and fibrotic signaling pathways (92). A recent study supports this view; the exosome-like vesicles secreted by adipose tissues carry ~one third of miRNA relevant to adipogenesis to induce adipogenesis of adipose tissue-derived stem cells (93). A study by Skowron et al (94) suggested that obesity increased the risk of melanoma malignant metastasis. Recently, a mechanism by which exosomes are linked to obesity and melanoma was identified. It was revealed that adipocyte exosomes carried the majority of proteins involved in lipid metabolism, primarily for fatty acid oxidation. Crucially, this feature contributed to the migration and invasion of melanoma cells (19,95). These results may explain why patients with obesity and melanoma have a poor prognosis, and may lead to a novel strategy for the treatment of melanoma by reducing body fat content or inhibiting fatty acid oxidation.

9. Conclusion

The discovery and confirmation of the role of exosomes has had a profound influence on the understanding of organism physiology and pathological processes. Exosomes not only carry pathological or physiological marker proteins/RNA of donor cells, but may also act as a vehicle for the transfer of drugs and other molecules to lesion sites. Furthermore, exosomes also have the potential to be modified and processed. In the present review, exosomes involved in skin development, function and diseases were discussed. Further in-depth studies of exosomes are required to determine whether they may be utilized as high-performance tools and as a novel pathway for regulating skin development and diseases in the future.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 81700650 and 31772690).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

YL drafted the article, HW revised the article and JW provided ideas and helped to improve language accuracy.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Ng KW, Lau WM. Skin Deep: The Basics of Human Skin Structure and Drug Penetration. Springer-Verlag; Berlin Heidelberg, New York: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Menon GK. Lipids and Skin Health. Springer International Publishing; Switzerland: 2015. Skin basics; structure and function; pp. 9–23. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barbieri JS, Wanat K, Seykora J, editors. Pathobiology of Human Disease. Academic Press; 2014. Skin: Basic structure and function; pp. 1134–1144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mcgrath JA, Eady RAJ, Pope FM. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 7th. Wiley; 2008. Anatomy and organization of human skin; pp. 45–128. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hay RJ, Johns NE, Williams HC, Bolliger IW, Dellavalle RP, Margolis DJ, Marks R, Naldi L, Weinstock MA, Wulf SK, et al. The global burden of skin disease in 2010: An analysis of the prevalence and impact of skin conditions. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1527–1534. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lo Cicero A, Delevoye C, Gilles-Marsens F, Loew D, Dingli F, Guéré C, André N, Vié K, van Niel G, Raposo G. Exosomes released by keratinocytes modulate melanocyte pigmentation. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7506. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Felicetti F, De Feo A, Coscia C, Puglisi R, Pedini F, Pasquini L, Bellenghi M, Errico MC, Pagani E, Carè A. Exosome-mediated transfer of miR-222 is sufficient to increase tumor malignancy in melanoma. J Transl Med. 2016;14:56. doi: 10.1186/s12967-016-0811-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin J, Li J, Huang B, Liu J, Chen X, Chen XM, Xu YM, Huang LF, Wang XZ. Exosomes: Novel biomarkers for clinical diagnosis. Sci World J. 2015;2015:657086. doi: 10.1155/2015/657086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Properzi F, Logozzi M, Fais S. Exosomes: The future of biomarkers in medicine. Biomarkers Med. 2013;7:769–778. doi: 10.2217/bmm.13.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cocucci E, Racchetti G, Meldolesi J. Shedding microvesicles: Artefacts no more. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bach DH, Hong JY, Park HJ, Lee SK. The role of exosomes and miRNAs in drug-resistance of cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2017;141:220–230. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lai RC, Chen TS, Lim SK. Mesenchymal stem cell exosome: A novel stem cell-based therapy for cardiovascular disease. Regen Med. 2011;6:481–492. doi: 10.2217/rme.11.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rabinowits G, Gerçel-Taylor C, Day JM, Taylor DD, Kloecker GH. Exosomal microRNA: A diagnostic marker for lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2009;10:42–46. doi: 10.3816/CLC.2009.n.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yan Y, Jiang W, Tan Y, Zou S, Zhang H, Mao F, Gong A, Qian H, Xu W. hucMSC exosome-derived GPX1 is required for the recovery of hepatic oxidant injury. Mol Ther. 2017;25:465–479. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2016.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li J, Chen Y, Guo X, Zhou L, Jia Z, Peng Z, Tang Y, Liu W, Zhu B, Wang L, Ren C. GPC1 exosome and its regulatory miRNAs are specific markers for the detection and target therapy of colorectal cancer. J Cell Mol Med. 2017;21:838–847. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Proksch E, Brandner JM, Jensen JM. The skin: An indispensable barrier. Exp Dermatol. 2008;17:1063–1072. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2008.00786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forslind B, Lindberg M, editors. Skin, Hair, and Nails: Structure and Function. CRC Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bang C, Batkai S, Dangwal S, Gupta SK, Foinquinos A, Holzmann A, Just A, Remke J, Zimmer K, Zeug A, et al. Cardiac fibroblast-derived microRNA passenger strand-enriched exosomes mediate cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:2136–2146. doi: 10.1172/JCI70577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holmes D. Adipose tissue: Adipocyte exosomes drive melanoma progression. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2016;12:436. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2016.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bickers DR, Athar M. Oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of skin disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:2565–2575. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akita N, Sawamura D, Matsumura K, Nomura K. Clinical study of diflorasone diacetate ointment (Diflal® ointment) in various types of skin diseases. Skin Res. 2010;29:115–119. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balato N, Megna M, Ayala F, Balato A, Napolitano M, Patruno C. Effects of climate changes on skin diseases. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2014;12:171–181. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2014.875855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu L, Song P, Yi X, Li C, Gao T. 067 Serum-derived exosomes contribute to abnormal melanocyte function in patients with active vitiligo. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136:S12–S12. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.02.092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu L, Wang J, Zhou X, Xiong Z, Zhao J, Yu R, Huang F, Zhang H, Chen L. Exosomes derived from human adipose mensenchymal stem cells accelerates cutaneous wound healing via optimizing the characteristics of fibroblasts. Sci Rep. 2016;6:32993. doi: 10.1038/srep32993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goedert L, Koya R, Hu-Lieskovan S, Ribas A. Exosomes as a predictor tool of acquired resistance to melanoma treatment; BMC Proc; 2014; p. P28. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiao D, Barry S, Kmetz D, Egger M, Pan J, Rai SN, Qu J, McMasters KM, Hao H. Melanoma cell-derived exosomes promote epithelial-mesenchymal transition in primary melanocytes through paracrine/autocrine signaling in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Lett. 2016;376:318–327. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.03.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simpson RJ, Jensen SS, Lim JW. Proteomic profiling of exosomes: Current perspectives. Proteomics. 2008;8:4083–4099. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vlassov AV, Magdaleno S, Setterquist R, Conrad R. Exosomes: Current knowledge of their composition, biological functions, and diagnostic and therapeutic potentials. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1820:940–948. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pan BT, Johnstone RM. Fate of the transferrin receptor during maturation of sheep reticulocytes in vitro: Selective externalization of the receptor. Cell. 1983;33:967–978. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mathivanan S, Ji H, Simpson RJ. Exosomes: Extracellular organelles important in intercellular communication. J Proteomics. 2010;73:1907–1920. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simpson RJ, Lim JW, Moritz RL, Mathivanan S. Exosomes: Proteomic insights and diagnostic potential. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2009;6:267–283. doi: 10.1586/epr.09.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lakkaraju A, Rodriguez-Boulan E. Itinerant exosomes: Emerging roles in cell and tissue polarity. Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:199–209. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Niel G, Porto-Carreiro I, Simoes S, Raposo G. Exosomes: A common pathway for a specialized function. J Biochem. 2006;140:13–21. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvj128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Segura MF, Hanniford D, Menendez S, Reavie L, Zou X, Alvarez-Diaz S, Zakrzewski J, Blochin E, Rose A, Bogunovic D, et al. Aberrant miR-182 expression promotes melanoma metastasis by repressing FOXO3 and microphthalmia-associated transcription factor; Proc Natl Acad Sci USA; 2009; pp. 1814–1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Conde-Vancells J, Rodriguez-Suarez E, Embade N, Gil D, Matthiesen R, Valle M, Elortza F, Lu SC, Mato JM, Falcon-Perez JM. Characterization and comprehensive proteome profiling of exosomes secreted by hepatocytes. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:5157–5166. doi: 10.1021/pr8004887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou H, Cheruvanky A, Hu X, Matsumoto T, Hiramatsu N, Cho ME, Berger A, Leelahavanichkul A, Doi K, Chawla LS, et al. Urinary exosomal transcription factors, a new class of biomarkers for renal disease. Kidney Int. 2008;74:613–621. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Théry C, Ostrowski M, Segura E. Membrane vesicles as conveyors of immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:581–593. doi: 10.1038/nri2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ichim T, Bogin V. US Patent 20160361399 A1. Therapeutic immune modulation by stem cell secreted exosomes. 2016 Aug 4; issued December 15, 2016.

- 39.Liu Q, Rojas-Canales DM, Divito SJ, Shufesky WJ, Stolz DB, Erdos G, Sullivan ML, Gibson GA, Watkins SC, Larregina AT, et al. Donor dendritic cell-derived exosomes promote allograft-targeting immune response. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:2805–2820. doi: 10.1172/JCI84577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao H, Yang L, Baddour J, Achreja A, Bernard V, Moss T, Marini JC, Tudawe T, Seviour EG, San Lucas FA, et al. Tumor microenvironment derived exosomes pleiotropically modulate cancer cell metabolism. Elife. 2016;5:e10250. doi: 10.7554/eLife.10250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yi H, Ye J, Yang XM, Zhang LW, Zhang ZG, Chen YP. High-grade ovarian cancer secreting effective exosomes in tumor angiogenesis. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:5062–5070. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tickner JA, Urquhart AJ, Stephenson SA, Richard DJ, O'Byrne KJ. Functions and therapeutic roles of exosomes in cancer. Front Oncol. 2014;4:127. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saleem SN, Abdel-Mageed AB. Tumor-derived exosomes in oncogenic reprogramming and cancer progression. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;72:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1710-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chevillet JR, Kang Q, Ruf IK, Briggs HA, Vojtech LN, Hughes SM, Cheng HH, Arroyo JD, Meredith EK, Gallichotte EN, et al. Quantitative and stoichiometric analysis of the microRNA content of exosomes; Proc Natl Acad Sci USA; 2014; pp. 14888–14893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bi S, Wang C, Jin Y, Lv Z, Xing X, Lu Q. Correlation between serum exosome derived miR-208a and acute coronary syndrome. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:4275–4280. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang H, Wang B. Extracellular vesicle microRNAs mediate skeletal muscle myogenesis and disease. Biomed Rep. 2016;5:296–300. doi: 10.3892/br.2016.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Humphries B. Dissecting the mechanism by which microRNA-200b inhibits breast cancer metastasis. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang B, Yao K, Huuskes BM, Shen HH, Zhuang J, Godson C, Brennan EP, Wilkinson-Berka JL, Wise AF, Ricardo SD. Mesenchymal stem cells deliver exogenous microRNA-let7c via exosomes to attenuate renal fibrosis. Mol Ther. 2016;24:1290–1301. doi: 10.1038/mt.2016.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lou G, Song X, Yang F, Wu S, Wang J, Chen Z, Liu Y. Exosomes derived from miR-122-modified adipose tissue-derived MSCs increase chemosensitivity of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hematol Oncol. 2015;8:122. doi: 10.1186/s13045-015-0220-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ji Q, Ji Y, Peng J, Zhou X, Chen X, Zhao H, Xu T, Chen L, Xu Y. Increased brain-specific miR-9 and miR-124 in the serum exosomes of acute ischemic stroke patients. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0163645. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jackson SJ, Zhang Z, Feng D, Flagg M, O'Loughlin E, Wang D, Stokes N, Fuchs E, Yi R. Rapid and widespread suppression of self-renewal by microRNA-203 during epidermal differentiation. Development. 2013;140:1882–1891. doi: 10.1242/dev.089649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nijhof JG, van Pelt C, Mulder AA, Mitchell DL, Mullenders LH, de Gruijl FR. Epidermal stem and progenitor cells in murine epidermis accumulate UV damage despite NER proficiency. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:792–800. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mistry DS, Chen Y, Sen GL. Progenitor function in self-renewing human epidermis is maintained by the exosome. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Noiret M, Mottier S, Angrand G, Gautier-Courteille C, Lerivray H, Viet J, Paillard L, Mereau A, Hardy S, Audic Y. Ptbp1 and Exosc9 knockdowns trigger skin stability defects through different pathways. Dev Biol. 2016;409:489–501. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Clevers H. Wnt/β-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell. 2006;127:469–480. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gross JC, Chaudhary V, Bartscherer K, Boutros M. Active Wnt proteins are secreted on exosomes. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:1036–1045. doi: 10.1038/ncb2574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang B, Wang M, Gong A, Zhang X, Wu X, Zhu Y, Shi H, Wu L, Zhu W, Qian H, Xu W. HucMSC-exosome mediated-Wnt4 signaling is required for cutaneous wound healing. Stem Cells. 2015;33:2158–2168. doi: 10.1002/stem.1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Varothai S, Bergfeld WF. Androgenetic alopecia: An evidence-based treatment update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:217–230. doi: 10.1007/s40257-014-0077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lim SK, Yeo MSW, Chen TS, Lai RC, inventors. EP Patent 2629782 A1. Use of exosomes to promote or enhance hair growth. 2011 Oct 17; issued August 28, 2013.

- 60.Lin JY, Fisher DE. Melanocyte biology and skin pigmentation. Nature. 2007;445:843–850. doi: 10.1038/nature05660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rawlings AV. Ethnic skin types: Are there differences in skin structure and function? Int J Cosmet Sci. 2006;28:79–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2494.2006.00302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Whitton M, Pinart M, Batchelor JM, Leonardi-Bee J, Gonzalez U, Jiyad Z, Eleftheriadou V, Ezzedine K. Evidence-based management of vitiligo: Summary of a Cochrane systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:962–969. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang J, Guan J, Niu X, Hu G, Guo S, Li Q, Xie Z, Zhang C, Wang Y. Exosomes released from human induced pluripotent stem cells-derived MSCs facilitate cutaneous wound healing by promoting collagen synthesis and angiogenesis. J Transl Med. 2015;13:49. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0417-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li X, Jiang C, Zhao J. Human endothelial progenitor cells-derived exosomes accelerate cutaneous wound healing in diabetic rats by promoting endothelial function. J Diabetes Complications. 2016;30:986–992. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2016.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gallet R, Dawkins J, Valle J, Simsolo E, de Couto G, Middleton R, Tseliou E, Luthringer D, Kreke M, Smith RR, et al. Exosomes secreted by cardiosphere-derived cells reduce scarring, attenuate adverse remodelling, and improve function in acute and chronic porcine myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:201–211. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhao B, Zhang Y, Han S, Zhang W, Zhou Q, Guan H, Liu J, Shi J, Su L, Hu D. Exosomes derived from human amniotic epithelial cells accelerate wound healing and inhibit scar formation. J Mol Histol. 2017;48:121–132. doi: 10.1007/s10735-017-9711-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang B, Wu X, Zhang X, Sun Y, Yan Y, Shi H, Zhu Y, Wu L, Pan Z, Zhu W, et al. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell exosomes enhance angiogenesis through the Wnt4/β-catenin pathway. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2015;4:513–522. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2014-0267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nakamura K, Jinnin M, Fukushima S, Ihn H. Exosome expression in the skin and sera of systemic sclerosis patients, and its possible therapeutic application against skin ulcer. J Dermatol Sci. 2016;84:e97–e98. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2016.08.295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Diepgen TL, Mahler V. The epidemiology of skin cancer. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146(Suppl 61):1–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.146.s61.2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wernli KJ, Henrikson NB, Morrison CC, Nguyen M, Pocobelli G, Blasi PR. Screening for skin cancer in adults: Updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;316:436–447. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.5415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, Gonzalez R, Robert C, Schadendorf D, Hassel JC, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Alegre E, Zubiri L, Perez-Gracia JL, González-Cao M, Soria L, Martín-Algarra S, González A. Circulating melanoma exosomes as diagnostic and prognosis biomarkers. Clin Chim Acta. 2016;454:28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2015.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gray-Schopfer V, Wellbrock C, Marais R. Melanoma biology and new targeted therapy. Nature. 2007;445:851–857. doi: 10.1038/nature05661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gajos-Michniewicz A, Duechler M, Czyz M. miRNA in melanoma-derived exosomes. Cancer Lett. 2014;347:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hood JL, San RS, Wickline SA. Exosomes released by melanoma cells prepare sentinel lymph nodes for tumor metastasis. Cancer Res. 2011;71:3792–3801. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ekström EJ, Bergenfelz C, von Bülow V, Serifler F, Carlemalm E, Jönsson G, Andersson T, Leandersson K. WNT5A induces release of exosomes containing pro-angiogenic and immunosuppressive factors from malignant melanoma cells. Mol Cancer. 2014;13:88. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-13-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hood JL. Melanoma exosomes enable tumor tolerance in lymph nodes. Med Hypotheses. 2016;90:11–13. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2016.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shoshan E, Mobley AK, Braeuer RR, Kamiya T, Huang L, Vasquez ME, Salameh A, Lee HJ, Kim SJ, Ivan C, et al. Reduced adenosine-to-inosine miR-455-5p editing promotes melanoma growth and metastasis. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:311–321. doi: 10.1038/ncb3110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhou J, Xu D, Xie H, Tang J, Liu R, Li J, Wang S, Chen X, Su J, Zhou X, et al. miR-33a functions as a tumor suppressor in melanoma by targeting HIF-1α. Cancer Biol Ther. 2015;16:846–855. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2015.1030545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bhattacharya A, Schmitz U, Raatz Y, Schönherr M, Kottek T, Schauer M, Franz S, Saalbach A, Anderegg U, Wolkenhauer O, et al. miR-638 promotes melanoma metastasis and protects melanoma cells from apoptosis and autophagy. Oncotarget. 2015;6:2966–2980. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Alegre E, Sanmamed MF, Rodriguez C, Carranza O, Martín-Algarra S, González A. Study of circulating microRNA-125b levels in serum exosomes in advanced melanoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138:828–832. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2013-0134-OA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pfeffer SR, Grossmann KF, Cassidy PB, Yang CH, Fan M, Kopelovich L, Leachman SA, Pfeffer LM. Detection of exosomal miRNAs in the plasma of melanoma patients. J Clin Med. 2015;4:2012–2027. doi: 10.3390/jcm4121957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mutschelknaus L, Peters C, Winkler K, Yentrapalli R, Heider T, Atkinson MJ, Moertl S. Exosomes derived from squamous head and neck cancer promote cell survival after ionizing radiation. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0152213. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Languino LR, Singh A, Prisco M, Inman GJ, Luginbuhl A, Curry JM, South AP. Exosome-mediated transfer from the tumor microenvironment increases TGFβ signaling in squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Transl Res. 2016;8:2432–2437. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jelonek K, Wojakowska A, Marczak L, Muer A, Tinhofer-Keilholz I, Lysek-Gladysinska M, Widlak P, Pietrowska M. Ionizing radiation affects protein composition of exosomes secreted in vitro from head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Acta Biochim Pol. 2015;62:265–272. doi: 10.18388/abp.2015_970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Toki S, Motegi S, Yamada K, Uchiyama A, Kanai S, Yamanaka M, Ishikawa O. Clinical and laboratory features of systemic sclerosis complicated with localized scleroderma. J Dermatol. 2015;42:283–287. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nakamura K, Jinnin M, Harada M, Kudo H, Nakayama W, Inoue K, Ogata A, Kajihara I, Fukushima S, Ihn H. Altered expression of CD63 and exosomes in scleroderma dermal fibroblasts. J Dermatol Sci. 2016;84:30–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2016.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Brouwer R, Pruijn GJ, van Venrooij WJ. The human exosome: An autoantigenic complex of exoribonucleases in myositis and scleroderma. Arthritis Res. 2001;3:102–106. doi: 10.1186/ar147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gutiérrez-Ramos R, Gonz Lez-Díaz V, Pacheco-Tovar MG, López-Luna A, Avalos-Díaz E, Herrera-Esparza R. A dermatomyositis and scleroderma overlap syndrome with a remarkable high titer of anti-exosome antibodies. Reumatismo. 2008;60:296–300. doi: 10.4081/reumatismo.2008.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Barkai L, Paragh G. Metabolic syndrome in childhood and adolescence. Orv Hetil. 2006;147:243–250. (In Hungarian) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rajala MW, Scherer PE. Minireview: The adipocyte - at the crossroads of energy homeostasis, inflammation, and atherosclerosis. Endocrinology. 2003;144:3765–3773. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ferrante SC, Nadler EP, Pillai DK, Hubal MJ, Wang Z, Wang JM, Gordish-Dressman H, Koeck E, Sevilla S, Wiles AA, Freishtat RJ. Adipocyte-derived exosomal miRNAs: A novel mechanism for obesity-related disease. Pediatr Res. 2015;77:447–454. doi: 10.1038/pr.2014.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhang Y, Yu M, Dai M, Chen C, Tang Q, Jing W, Wang H, Tian W. miR-450a-5p within rat adipose tissue exosome-like vesicles promotes adipogenic differentiation by targeting WISP2. J Cell Sci. 2017;130:1158–1168. doi: 10.1242/jcs.197764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Skowron F, Bérard F, Balme B, Maucort-Boulch D. Role of obesity on the thickness of primary cutaneous melanoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:262–269. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lazar I, Clement E, Dauvillier S, Milhas D, Ducoux-Petit M, LeGonidec S, Moro C, Soldan V, Dalle S, Balor S, et al. Adipocyte exosomes promote melanoma aggressiveness through fatty acid oxidation: a novel mechanism linking obesity and cancer. Cancer Res. 2016;76:4051–4057. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.