Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to determine the effects of melatonin on insulin resistance in obese patients with acanthosis nigricans (AN).

Methods

A total of 17 obese patients with acanthosis nigricans were recruited in a 12-week pilot open trial. Insulin sensitivity, glucose metabolism, inflammatory factors, and other biochemical parameters before and after the administration of melatonin were measured.

Results

After 12 weeks of treatment with melatonin (3 mg/day), homeostasis model assessment insulin resistance index (HOMA-IR) (8.99 ± 5.10 versus 7.77 ± 5.21, p < 0.05) and fasting insulin (37.09 5 ± 20.26 μU/ml versus 32.10 ± 20.29 μU/ml, p < 0.05) were significantly decreased. Matsuda index (2.82 ± 1.54 versus 3.74 ± 2.02, p < 0.05) was significantly increased. There were also statistically significant declines in the AN scores of the neck and axilla, body weight, body mass index, body fat, visceral index, neck circumference, waist circumference, and inflammatory markers.

Conclusions

It was concluded that melatonin could improve cutaneous symptoms in obese patients with acanthosis nigricans by improving insulin sensitivity and inflammatory status. This trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02604095.

1. Introduction

Melatonin is a hormone secreted by the pineal gland. The synthesis and secretion of melatonin are regulated by light intensity [1]. Investigations found that melatonin has multiple effects and acts as an antioxidant [2, 3], has anti-inflammatory properties [4, 5], regulates circadian rhythms [6], regulates immunity [7] and has antineoplastic effects [8]. Research also found that melatonin can regulate lipid metabolism [9], increase insulin sensitivity [10], regulate glucose metabolism [11], and reduce body weight [12].

Acanthosis nigricans (AN) is a disease characterized by skin pigmentation, hyperkeratosis, and velvet hyperplasia. Increased pigmentation commonly occurs in the posterior neck, axilla, and groin, and it can also be seen on the cubital fossa, labia, face, and other locations throughout the body [13]. AN can be divided into two categories: benign and malignant [14]. Studies have found that benign AN is closely related to hyperinsulinemia, insulin resistance (IR), and obesity [15, 16]. Many different topical and oral treatments have been attempted for AN. Studies reported that treatment with both metformin and rosiglitazone are useful in AN characterized by IR [17, 18]. Low-calorie diet, increasing physical activity, and weight reduction also can relieve symptoms of AN by improving the IR [19]. However, no safe and effective therapy exists especially when considering young patients with euglycemia. Patients with AN also are at increased risk of developing metabolic disorders such as diabetes and dyslipidemia.

Melatonin can regulate internal biological clocks and energy metabolism [20]. Melatonin influences insulin secretion mediated by Gi-protein-coupled melatonin receptors MT1 and MT2 [21]. It was found that melatonin treatment for one year could reduce fat mass and increase lean mass in postmenopausal women [22]. So this study was designed to determine whether treatment with melatonin is an effective treatment for AN as well as insulin resistance and metabolic disturbances.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

A total of 17 patients (6 males and 11 females, age 27.35 ± 6.50) were enrolled in the 12-week pilot open trial with no placebo group included. The study was approved by the ethical committee of the Shanghai Tenth People's Hospital, Tongji University, Shanghai, China, and registered by ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02604095). Inclusion criteria included (1) aging from 18 to 60 years old, (2) having acanthosis nigricans, and (3) body mass index (BMI) exceeding 28 kg/m2. Exclusion criteria included (1) malignant acanthosis nigricans; (2) serious renal, adrenal, or hepatic dysfunction; (3) taking medications chronically for systemic illness; (4) lactation; (5) pregnancy; (6) active cancer; (7) taking weight-loss drugs; and (8) history of stomach reduction surgery. Each patient gave written informed voluntary consent before participating in the study.

2.2. Study Design

After the initial screening, age, gender, and height of each participant were recorded. Weight, BMI, and visceral index were measured with light clothes and without shoes using an Omron HBF-358 (Q40102010L01322F, Japan), with the same controlling of water, food, diuretics, alcohol and coffee intake, and urination. Neck circumference (NC), waist circumference (WC), hip circumference (HC), blood pressure (BP), and heart rate (HR) were measured twice, and the average was used for analysis.

Scores of AN were calculated as described previously [23]. There are four degrees from 0 to 4 on the AN scales, which are strongly associated with fasting insulin and BMI.

After overnight fasting, serum glucose, insulin, C-peptide (C-p), lipid profiles, free fatty acids (FFA), uric acid (UA), inflammation factors (c-reactive protein (CRP), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin 6 (IL-6), and interleukin 8 (IL-8)), superoxide dismutase (SOD), alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST), creatinine (Cr), urea nitrogen (UN), free triiodothyronine (fT3), free thyroxine (fT4), and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) were measured. Participant also underwent a standard 75 g oral glucose-tolerance test (OGTT) after fasting overnight. Samples were collected at 0, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min, and glucose, insulin, and C-p were measured. All these measurements were performed before and after 12 weeks of treatment.

Each patient received 3 mg/day melatonin (Schiff Nutrition Group: each tablet contains melatonin 3 mg, vitamin B6 5 mg, and calcium 52 mg) given orally at bedtime for 12 weeks.

2.3. Statistics and Calculations

All data were analyzed using SPSS 21.0 software (Chicago, IL). The data are presented as the means ± SD or medians (interquartile range) for skewed variables or proportions for categorical variables. Student's t-tests were used to compare the difference between measured variables. p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Insulin resistance and sensitivity were assessed by the homeostasis model assessment insulin resistance index (HOMA-IR; fasting insulin × fasting glucose/22.5) [24] and Matsuda index {1000/(Glu0 × Ins0 × mean-glucose × mean-insulin)1/2} [25].

3. Results

3.1. Insulin Resistance and Sensitivity

As shown in Table 1, melatonin treatment significantly decreased the HOMA-IR (8.99 ± 5.1047 versus 7.77 ± 5.2169, p < 0.05) and fasting insulin (37.0935 ± 20.26215 versus 32.1018 ± 20.29752 μU/ml, p < 0.05) levels and induced the Matsuda index (2.82 ± 1.54 versus 3.74 ± 2.02, p < 0.05). There was no statistically significant change in fasting glucose and fasting C peptide levels.

Table 1.

Effects of melatonin on various biochemical indices.

| Parameters | Baseline | After 12 weeks of treatment | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| HOMA-IR | 8.99 ± 5.1047 | 7.77 ± 5.2169 | 0.027∗ |

| Matsuda index | 2.822 ± 1.5423 | 3.744 ± 2.0238 | 0.017∗ |

| FPG, mmol/l | 5.365 ± 0.8645 | 5.341 ± 0.8307 | 0.839 |

| Glucose 30, mmol/l | 9.853 ± 1.9872 | 9.259 ± 1.8416 | 0.044∗ |

| Glucose 60, mmol/l | 10.794 ± 2.8203 | 10.247 ± 2.7405 | 0.156 |

| Glucose 120, mmol/l | 8.341 ± 3.1071 | 8.071 ± 3.2299 | 0.340 |

| Glucose 180, mmol/l | 5.835 ± 2.4392 | 5.812 ± 1.6605 | 0.939 |

| Fasting insulin, μU/ml | 37.0935 ± 20.26215 | 32.1018 ± 20.29752 | 0.010∗ |

| Insulin 30, μU/ml | 149.8935 ± 54.80039 | 116.8088 ± 54.59683 | <0.01∗ |

| Insulin 60, μU/ml | 170.45 ± 83.12034 | 143.9794 ± 63.21096 | 0.006 |

| Insulin 120, μU/ml | 160.4506 ± 85.95451 | 135.0529 ± 92.32970 | 0.018 |

| Insulin180, μU/ml | 80.2476 ± 64.86455 | 73.1259 ± 67.18857 | 0.416 |

| Fasting CP, ng/ml | 4.8776 ± 1.5665 | 4.5759 ± 1.4895 | 0.130 |

| TC, mmol/l | 4.9312 ± 0.7684 | 4.7671 ± 0.7834 | 0.212 |

| TG, mmol/l | 1.9094 ± 0.7576 | 1.7824 ± 0.8641 | 0.338 |

| HDL-C, mmol/l | 1.1029 ± 0.2911 | 1.0741 ± 0.2430 | 0.422 |

| LDL-C, mmol/l | 3.0282 ± 0.6262 | 2.9218 ± 0.4897 | 0.221 |

| FFA, mmol/l | 0.588 ± 0.2233 | 0.506 ± 0.1600 | 0.084 |

| UA, μmol/l | 443.518 ± 132.5464 | 432.635 ± 111.2079 | 0.400 |

| CRP, mg/l | 4.6159 ± 3.27755 | 3.6429 ± 2.89784 | 0.014∗ |

| IL-6, pg/ml | 15.3318 ± 13.84451 | 13.8276 ± 10.09683 | 0.527 |

| IL-8, pg/ml | 221.1482 ± 321.43527 | 177.6976 ± 241.08857 | 0.328 |

| TNF-α, pg/ml | 28.0594 ± 25.81318 | 16.9288 ± 14.92093 | 0.040∗ |

| SOD, U/ml | 154.06 ± 15.262 | 173.35 ± 55.623 | 0.166 |

| ALT, U/l | 47.224 ± 23.7542 | 42.929 ± 25.7068 | 0.391 |

| AST, U/l | 32.400 ± 16.5831 | 30.918 ± 13.5636 | 0.625 |

| Tbil, μmol/l | 10.376 ± 5.3582 | 10.476 ± 5.2538 | 0.903 |

| ALP, U/l | 77.347 ± 38.9236 | 73.018 ± 37.5913 | 0.217 |

| Cr, μmol/l | 59.641 ± 14.6798 | 60.959 ± 14.6248 | 0.312 |

| UN, mmol/l | 4.647 ± 1.1906 | 4.924 ± 1.3796 | 0.118 |

| fT3, pmol/l | 5.1976 ± 0.50209 | 5.0829 ± 0.55324 | 0.203 |

| fT4, pmol/l | 15.3112 ± 1.32976 | 15.0959 ± 1.85283 | 0.515 |

| TSH, pmol/l | 2.75288 ± 1.389337 | 2.43759 ± 1.174457 | 0.092 |

∗ p < 0.05.

3.2. Physiological Measures

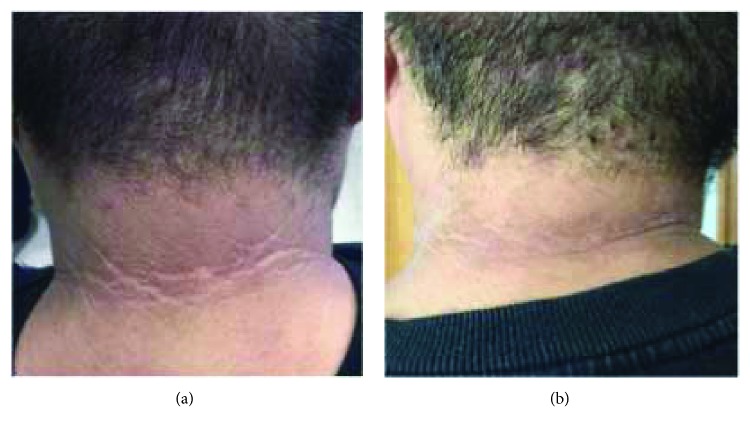

After 12 weeks of treatment with melatonin, there were statistically significant changes in the AN scores of the neck (3.35 ± 0.862 versus 2.59 ± 0.712, p < 0.01) and axilla (3.53 ± 0.717 versus 2.65 ± 0.702, p < 0.01) (Table 2). There were also significant reductions in BMI (35.741 ± 4.7844 versus 34.524 ± 4.7278 kg/m2, p < 0.01), body weight (100.912 ± 22.9884 versus 97.453 ± 21.8012 kg, p < 0.01), body fat (37.206 ± 5.3743% versus 35.488 ± 6.6078%, p < 0.05), and visceral index (17.41 ± 6.510 versus 15.82 ± 6.085, p < 0.01) (Table 2). Pigmentation in patients with AN was improved after treatment (Figure 1). Melatonin also decreased NC (40.718 ± 4.1652 versus 40.118 ± 4.1213 cm, p < 0.05), WC (111.471 ± 13.7184 versus 107.853 ± 14.2607 cm, p < 0.01), and HC (114.818 ± 10.6647 versus 113.488 ± 10.5441 cm, p < 0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Physiological measures.

| Parameters | Baseline | After 12 weeks of treatment | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| SBP, mmHg | 134.18 ± 10.690 | 131.88 ± 10.787 | 0.085 |

| DBP, mmHg | 87.53 ± 10.967 | 87.00 ± 11.292 | 0.478 |

| HR, bmp | 85.35 ± 7.533 | 82.35 ± 9.096 | 0.174 |

| Weight, kg | 100.912 ± 22.9884 | 97.453 ± 21.8012 | 0.001∗ |

| Body fat, % | 37.206 ± 5.3743 | 35.488 ± 6.6078 | 0.038∗ |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 35.741 ± 4.7844 | 34.524 ± 4.7278 | 0.001∗ |

| Visceral index | 17.41 ± 6.510 | 15.82 ± 6.085 | 0.001∗ |

| NC, cm | 40.718 ± 4.1652 | 40.118 ± 4.1213 | 0.045∗ |

| WC, cm | 111.471 ± 13.7184 | 107.853 ± 14.2607 | 0.002∗ |

| HC, cm | 114.818 ± 10.6647 | 113.488 ± 10.5441 | 0.028∗ |

| AN score, neck | 3.35 ± 0.862 | 2.59 ± 0.712 | <0.01∗ |

| AN score, axilla | 3.53 ± 0.717 | 2.65 ± 0.702 | <0.01∗ |

∗ p < 0.05.

Figure 1.

Effects of melatonin on acanthosis of neck: a typical case. (a) Baseline. (b) After 12 w treatment.

3.3. Lipid and Inflammatory Parameters

As shown in Table 1, there were no significant decreases in serum lipids (TC, TG, LDL-C, and HDL-C). CRP (4.6159 ± 3.27755 versus 3.6429 ± 2.89784 mg/l, p < 0.05) and TNF-α (28.0594 ± 25.81318 versus 16.9288 ± 14.92093, p < 0.05) were decreased significantly, but IL-6 and IL-8 did not decrease significantly. There were also no changes in serum SOD, ALT, AST, Cr, UN, fT3, fT4, and TSH (Table 2). The baseline of participants is showed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Baseline of participants.

(a).

| Number | Sex (1: male; 2: female) | Age (year) | SBP (mmHg) | DBP (mmHg) | HR (bpm) | Height (cm) | Weight (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 18 | 134 | 78 | 89 | 182 | 131.4 |

| 2 | 2 | 19 | 111 | 66 | 69 | 154 | 66.4 |

| 3 | 2 | 37 | 126 | 91 | 103 | 156 | 69 |

| 4 | 2 | 30 | 125 | 90 | 84 | 158 | 86.7 |

| 5 | 1 | 29 | 146 | 110 | 86 | 166 | 86.2 |

| 6 | 2 | 19 | 130 | 89 | 78 | 152 | 73.7 |

| 7 | 2 | 39 | 142 | 94 | 86 | 155.5 | 88.6 |

| 8 | 1 | 34 | 145 | 95 | 82 | 172 | 119.8 |

| 9 | 2 | 29 | 128 | 80 | 89 | 160 | 93.9 |

| 10 | 1 | 28 | 120 | 90 | 89 | 182 | 127.6 |

| 11 | 2 | 24 | 132 | 86 | 92 | 174 | 100.2 |

| 12 | 2 | 25 | 138 | 86 | 78 | 167 | 121 |

| 13 | 2 | 28 | 135 | 79 | 86 | 165 | 93.8 |

| 14 | 2 | 35 | 136 | 78 | 87 | 160 | 99.1 |

| 15 | 2 | 22 | 149 | 94 | 94 | 178 | 104.6 |

| 16 | 1 | 18 | 132 | 76 | 83 | 175 | 103.5 |

| 17 | 1 | 31 | 152 | 106 | 89 | 183 | 150 |

(b).

| Number | Fat (%) | BMI (kg/m2) | Visceral index | NC (cm) | WC (cm) | HC (cm) | AN score, neck | AN score, axilla |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 35.5 | 39.7 | 24 | 45.5 | 120.5 | 131.2 | 4 | 4 |

| 2 | 30.5 | 28 | 8 | 36 | 90.3 | 99.5 | 4 | 4 |

| 3 | 34.4 | 28.4 | 9 | 39.7 | 98 | 96 | 3 | 2 |

| 4 | 38.7 | 34.7 | 16 | 42 | 106.5 | 119.2 | 4 | 4 |

| 5 | 25 | 31.3 | 16 | 41.5 | 100.2 | 105 | 4 | 4 |

| 6 | 34.2 | 31.9 | 10 | 38.5 | 98.5 | 103 | 4 | 4 |

| 7 | 42.5 | 36.6 | 21 | 38 | 110 | 117 | 4 | 4 |

| 8 | 37.7 | 40.5 | 30 | 48.5 | 130 | 121 | 4 | 4 |

| 9 | 41.9 | 36.7 | 19 | 39 | 115 | 109 | 2 | 3 |

| 10 | 34.4 | 38.5 | 25 | 45 | 129 | 116 | 4 | 4 |

| 11 | 40.7 | 33.1 | 13 | 37 | 108 | 118 | 4 | 4 |

| 12 | 43.6 | 43.4 | 27 | 36 | 108 | 132 | 4 | 4 |

| 13 | 41 | 34.5 | 15 | 43 | 105 | 120 | 2 | 2 |

| 14 | 43.2 | 38.7 | 22 | 41.5 | 115 | 104 | 3 | 3 |

| 15 | 38.9 | 33 | 12 | 35 | 105 | 116 | 3 | 4 |

| 16 | 29.1 | 33.8 | 14 | 38 | 110 | 117 | 2 | 3 |

| 17 | 41.2 | 44.8 | 15 | 48 | 146 | 128 | 2 | 3 |

4. Discussion

In 2000, AN was established as a formal risk factor for the development of diabetes in children by the American Diabetes Association [16]. Insulin resistance commonly occurs in association with AN.

The cutaneous manifestations of AN are caused by hyperinsulinemia and the stimulation of keratinocytes and dermal fibroblasts by growth factors [26, 27]. Patients with hyperinsulinemia have increased IGF-1 levels [28]. Hyperinsulinemia is able to reduce IGF binding protein- (IGFBP-) 1 and IGFBP-2, which regulate levels of IGFs. Reduced IGFBP-1 and IGFBP-2 levels could increase free IGF-1, thereby promoting the development of papillomatosis and hyperkeratosis observed in AN [29]. There are two membrane receptors of melatonin called MT1 and MT2, which are G-protein-coupled receptors, in the periphery [30]. Both receptors are expressed in the islets of Langerhans and are involved in the regulation of glucagon secretion from α-cells and insulin secretion from β-cells [10]. Numerous studies support that activation of MT1 or MT2 leads to a reduction in second messenger 3′,5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) or 3′,5′-cyclic guano-sine monophosphate (cGMP) accompanied by reduced insulin secretion [31, 32]. Picinato et al. [33] found the effects of melatonin on the phosphorylation of IGF and insulin receptors triggering their signalization cascade. Therefore, the effect of melatonin on insulin secretion and IGF may explain the mechanism of action behind the utility of treating AN with melatonin.

Most patients with AN also have severe obesity. Accumulating evidence shows that obesity is a clinical indicator for the risk of cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, and the associated metabolic syndrome [34, 35]. Somewhat surprisingly, we found that treatment with melatonin for only 12 weeks significantly decreased body weight, BMI, body fat, and visceral index of obese participants. Previous studies have shown that NC is associated with the metabolic disorders related to insulin resistance, cardiovascular diseases, metabolic syndrome, and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome [36, 37]. Melatonin was also found to decrease NC and WC, which are commonly considered as risk factors for metabolic syndrome.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that melatonin has antioxidant [2, 3] and anti-inflammatory [4] functions. In our study, serum CRP and TNF-α were decreased. Some investigators have suggested that the inflammation induced by metabolic surplus is different from classical inflammation [38]. TNF-α was the first inflammatory marker discovered in adipose tissue of obese mice [39]. As another inflammatory marker, CRP has been shown to be associated with an increased risk for development of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [40]. We consider the anti-inflammatory function of melatonin as one of the possible mechanisms by which it improves AN.

This study had several limitations. Firstly, recruitment to diabetes trials has long been associated with placebo-mediated improvements in glycemic control and associated metabolic parameters [41]. But because of the lack resources to perform additional placebo arm studies, we do not have enough ability to recruit placebo-controlled subjects. Secondly, the sample size of the present study was relatively small. Because of the individual difference, we could not see significant changes in lipid metabolism and antioxidation functions. Secondly, we could not measure the overnight urinary 6-sulfatoxymelatonin excretion (UME), which can reflect the level of internal melatonin, of the outpatients. Further studies are necessary to prove these conclusions.

5. Conclusion

In summary, treatment with melatonin can decrease weight, adipose tissues, and cutaneous symptoms in obese patients with AN. It may act through improvement of insulin resistance and decreasing inflammation. However, further work must be done to elucidate its complete mechanism of action.

Acknowledgments

The present study would not have been possible without the participation of the patients. The abstract of this research has been published in ADA in 2016. This study is supported by the Program for Outstanding Medical Academic Leader, Central University Cross Fund, and Chinese Medical Association Fund (nos. 12020550355 and 22120170145).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

Hang Sun, Xingchun Wang, and Jiaqi Chen contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Skene D. J., Arendt J. Human circadian rhythms: physiological and therapeutic relevance of light and melatonin. Annals of Clinical Biochemistry: International Journal of Laboratory Medicine. 2006;43(5):344–353. doi: 10.1258/000456306778520142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang H. M., Zhang Y. Melatonin: a well-documented antioxidant with conditional pro-oxidant actions. Journal of Pineal Research. 2014;57(2):131–146. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manchester L. C., Coto-Montes A., Boga J. A., et al. Melatonin: an ancient molecule that makes oxygen metabolically tolerable. Journal of Pineal Research. 2015;59(4):403–419. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mauriz J. L., Collado P. S., Veneroso C., Reiter R. J., González-Gallego J. A review of the molecular aspects of melatonin’s anti-inflammatory actions: recent insights and new perspectives. Journal of Pineal Research. 2013;54(1):1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2012.01014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borges Lda S., Dermargos A., da Silva Junior E. P., Weimann E., Lambertucci R. H., Hatanaka E. Melatonin decreases muscular oxidative stress and inflammation induced by strenuous exercise and stimulates growth factor synthesis. Journal of Pineal Research. 2015;58(2):166–172. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vriend J., Reiter R. J. Melatonin feedback on clock genes: a theory involving the proteasome. Journal of Pineal Research. 2015;58(1):1–11. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee J. S., Cua D. J. Melatonin lulling Th17 cells to sleep. Cell. 2015;162(6):1212–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Di Bella G., Mascia F., Gualano L., Di Bella L. Melatonin anticancer effects: review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2013;14(2):2410–2430. doi: 10.3390/ijms14022410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun H., Huang F. F., Qu S. Melatonin: a potential intervention for hepatic steatosis. Lipids in Health and Disease. 2015;14(1):p. 75. doi: 10.1186/s12944-015-0081-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peschke E., Bahr I., Muhlbauer E. Melatonin and pancreatic islets: interrelationships between melatonin, insulin and glucagon. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2013;14(4):6981–7015. doi: 10.3390/ijms14046981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Espino J., Pariente J. A., Rodriguez A. B. Role of melatonin on diabetes-related metabolic disorders. World Journal of Diabetes. 2011;2(6):82–91. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v2.i6.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Srinivasan V., Ohta Y., Espino J., et al. Metabolic syndrome, its pathophysiology and the role of melatonin. Recent Patents on Endocrine, Metabolic & Immune Drug Discovery. 2013;7(1):11–25. doi: 10.2174/187221413804660953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwartz R. A. Acanthosis nigricans. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1994;31(1):1–19. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(94)70128-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phiske M. M. An approach to acanthosis nigricans. Indian Dermatology Online Journal. 2014;5(3):239–249. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.137765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kobaissi H. A., Weigensberg M. J., Ball G. D., Cruz M. L., Shaibi G. Q., Goran M. I. Relation between acanthosis nigricans and insulin sensitivity in overweight Hispanic children at risk for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(6):1412–1416. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.6.1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kutlubay Z., Engin B., Bairamov O., Tuzun Y. Acanthosis nigricans: a fold (intertriginous) dermatosis. Clinics in Dermatology. 2015;33(4):466–470. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bellot-Rojas P., Posadas-Sanchez R., Caracas-Portilla N., et al. Comparison of metformin versus rosiglitazone in patients with acanthosis nigricans: a pilot study. Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. 2006;5:884–889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freemark M., Bursey D. The effects of metformin on body mass index and glucose tolerance in obese adolescents with fasting hyperinsulinemia and a family history of type 2 diabetes. Pediatrics. 2001;107(4, article E55) doi: 10.1542/peds.107.4.e55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hermanns-Le T., Scheen A., Pierard G. E. Acanthosis nigricans associated with insulin resistance: pathophysiology and management. American Journal of Clinical Dermatology. 2004;5(3):199–203. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200405030-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szewczyk-Golec K., Wozniak A., Reiter R. J. Inter-relationships of the chronobiotic, melatonin, with leptin and adiponectin: implications for obesity. Journal of Pineal Research. 2015;59(3):277–291. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peschke E., Bahr I., Muhlbauer E. Experimental and clinical aspects of melatonin and clock genes in diabetes. Journal of Pineal Research. 2015;59(1):1–23. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amstrup A. K., Sikjaer T., Pedersen S. B., Heickendorff L., Mosekilde L., Rejnmark L. Reduced fat mass and increased lean mass in response to 1 year of melatonin treatment in postmenopausal women: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Clinical Endocrinology. 2016;84(3):342–347. doi: 10.1111/cen.12942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burke J. P., Hale D. E., Hazuda H. P., Stern M. P. A quantitative scale of acanthosis nigricans. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(10):1655–1659. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.10.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haffner S. M., Kennedy E., Gonzalez C., Miettinen H., Kennedy E., Stern M. P. A prospective analysis of the HOMA model. The Mexico City Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care. 1996;19(10):1138–1141. doi: 10.2337/diacare.19.10.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsuda M., DeFronzo R. A. Insulin sensitivity indices obtained from oral glucose tolerance testing: comparison with the euglycemic insulin clamp. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(9):1462–1470. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.9.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sinha S., Schwartz R. A. Juvenile acanthosis nigricans. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2007;57(3):502–508. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hud J. A., Jr., Cohen J. B., Wagner J. M., Cruz P. D., Jr. Prevalence and significance of acanthosis nigricans in an adult obese population. Archives of Dermatology. 1992;128(7):941–944. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1992.01680170073009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higgins S. P., Freemark M., Prose N. S. Acanthosis nigricans: a practical approach to evaluation and management. Dermatology Online Journal. 2008;14:p. 2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rudman S. M., Philpott M. P., Thomas G. A., Kealey T. The role of IGF-I in human skin and its appendages: morphogen as well as mitogen? The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 1997;109(6):770–777. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12340934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Legros C., Devavry S., Caignard S., et al. Melatonin MT1 and MT2 receptors display different molecular pharmacologies only in the G-protein coupled state. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2014;171(1):186–201. doi: 10.1111/bph.12457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacKenzie R. S., Melan M. A., Passey D. K., Witt-Enderby P. A. Dual coupling of MT1 and MT2 melatonin receptors to cyclic AMP and phosphoinositide signal transduction cascades and their regulation following melatonin exposure. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2002;63(4):587–595. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(01)00881-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sartori C., Dessen P., Mathieu C., et al. Melatonin improves glucose homeostasis and endothelial vascular function in high-fat diet-fed insulin-resistant mice. Endocrinology. 2009;150(12):5311–5317. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Picinato M. C., Hirata A. E., Cipolla-Neto J., et al. Activation of insulin and IGF-1 signaling pathways by melatonin through MT1 receptor in isolated rat pancreatic islets. Journal of Pineal Research. 2008;44(1):88–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2007.00493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organization Technical Report Series. 2000;894:i–xii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tan D. X., Manchester L. C., Fuentes-Broto L., Paredes S. D., Reiter R. J. Significance and application of melatonin in the regulation of brown adipose tissue metabolism: relation to human obesity. Obesity Reviews. 2011;12(3):167–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Onat A., Hergenc G., Yuksel H., et al. Neck circumference as a measure of central obesity: associations with metabolic syndrome and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome beyond waist circumference. Clinical Nutrition. 2009;28(1):46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ben-Noun L. L., Laor A. Relationship between changes in neck circumference and cardiovascular risk factors. Experimental & Clinical Cardiology. 2006;11(1):14–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hotamisligil G. S. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature. 2006;444(7121):860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature05485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hotamisligil G. S., Arner P., Caro J. F., Atkinson R. L., Spiegelman B. M. Increased adipose tissue expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in human obesity and insulin resistance. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1995;95(5):2409–2415. doi: 10.1172/JCI117936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pradhan A. D., Manson J. E., Rifai N., Buring J. E., Ridker P. M. C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 2001;286(3):327–334. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gale E. A., Beattie S. D., Hu J., Koivisto V., Tan M. H. Recruitment to a clinical trial improves glycemic control in patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(12):2989–2992. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]