Abstract

ΔFosB is a member of the activator protein-1 family of transcription factors. ΔFosB has low constitutive expression in the central nervous system and is induced after exposure of rodents to intermittent hypoxia (IH), a model of the arterial hypoxemia that accompanies sleep apnea. We hypothesized ΔFosB in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) contributes to increased mean arterial pressure (MAP) during IH. The NTS of 11 male Sprague-Dawley rats was injected (3 sites, 100 nl/site) with a dominant negative construct against ΔFosB (ΔJunD) in an adeno-associated viral vector (AAV)-green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter. The NTS of 10 rats was injected with AAV-GFP as sham controls. Two weeks after NTS injections, rats were exposed to IH for 8 h/day for 7 days, and MAP was recorded using telemetry. In the sham group, 7 days of IH increased MAP from 99.8 ± 1.1 to 107.3 ± 0.5 mmHg in the day and from 104.4 ± 1.1 to 109.8 ± 0.6 mmHg in the night. In the group that received ΔJunD, IH increased MAP during the day from 95.9 ± 1.7 to 101.3 ± 0.4 mmHg and from 100.9 ± 1.7 to 102.8 ± 0.5 mmHg during the night (both IH-induced changes in MAP were significantly lower than sham, P < 0.05). After injection of the dominant negative construct in the NTS, IH-induced ΔFosB immunoreactivity was decreased in the paraventricular nucleus (P < 0.05); however, no change was observed in the rostral ventrolateral medulla. These data indicate that ΔFosB within the NTS contributes to the increase in MAP induced by IH exposure.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY The results of this study provides new insights into the molecular mechanisms that mediate neuronal adaptations during exposures to intermittent hypoxia, a model of the hypoxemias that occur during sleep apnea. These adaptations are noteworthy as they contribute to the persistent increase in blood pressure induced by exposures to intermittent hypoxia.

Keywords: ΔFosB, intermittent hypoxia, nucleus of the solitary tract

INTRODUCTION

Sleep apnea is associated with repeated periods where respiratory airflow ceases or is reduced and is associated with cardiovascular and metabolic diseases (1, 35, 40), including systemic hypertension (14, 19). Hypoxemia activates arterial chemoreceptors, and chemoreceptor afferents release the excitatory amino acid neurotransmitter glutamate at synapses with nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) neurons that project to and activate other regions such as the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN) (28, 34) and rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) (11) to increase sympathetic nervous discharge (SND) and mean arterial pressure (MAP). To study sleep apnea-induced pathologies, many laboratories have used a rodent model of intermittent hypoxia (IH), which mimics the repetitive arterial hypoxemia seen in patients with sleep-disordered breathing including obstructive sleep apnea (7, 8). Like sleep apnea patients, rats exposed to IH show elevated arterial pressure and SND as well as increases in both the basal activity and hypoxic sensitivity of the arterial chemoreflex, all of which contribute to systemic hypertension (7–10, 36, 37). IH elevates MAP and SND not only during IH exposures during the rats’ subjective night or inactive period but also throughout the rest of the diurnal cycle when the animals are under normoxic conditions (1, 4, 13, 16, 36). This persistent increase in MAP and SND in the absence of a hypoxic stimulus suggests that alterations occur in the chemoreflex pathway that facilitate sustained hypertension.

Chemoreceptor afferent discharge is elevated after exposures to IH (30–32); however, the central mechanisms that might also contribute to this persistent increase of SND and hypertension induced by IH are currently unclear. One factor that could contribute to the sustained hypertension observed after exposures to IH is the transcription factor FosB or its more stable splice variant ∆FosB. ∆FosB has been used as an indicator of chronic or intermittent activation of central neurons in response to drug addiction (23–26), and ∆FosB immunoreactivity is increased in major cardiovascular regulatory regions of the central nervous system (CNS) after 7-day exposure to IH (1, 16, 18). The functional role of ∆FosB in both drug addiction and IH has been studied using viral contructs that express ∆JunD, a dominant negative construct that functionally antagonizes ∆FosB. ∆JunD binds to ∆FosB and prevents the complex from binding to activator protein-1 (AP-1) sites on DNA, thus inhibiting the transcriptional function of ∆FosB. Using this dominant negative construct, Cunningham et al. (4) demonstrated that ∆FosB in the median preoptic nucleus (MnPO) contributes to the sustained hypertension resulting from IH. IH increases the number of ΔFosB-immunoreactive neurons in the NTS (16); therefore, experiments using the ∆JunD construct were performed to examine the role of ∆FosB in the NTS on IH-induced hypertension. To examine if IH-induced ∆FosB in the NTS impacts the activity of neurons in two major sympathoexcitatory sites downstream from NTS, ∆FosB immunoreactivity in the PVN and RVLM were also examined.

The goal of the present study was to test the hypothesis that functional antagonism of ΔFosB function in NTS neurons during IH will attenuate the elevated blood pressure observed during exposure to IH and that this reduced blood pressure will be associated with reduced transcriptional activation of neurons in the PVN and RVLM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (200–250 g) from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) were individually housed in a thermostatically regulated room with a 12:12-h light-dark cycle (on at 7 AM, off at 7 PM) and supplied with food and water ad libitum. All experiments were performed in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines and with the approval of Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of North Texas Health Science Center (Fort Worth, TX).

The timeline for the proposed experiments was as follows. Animals were allowed to acclimate in the vivarium for at least 1 wk before receiving an NTS microinjection of a sham viral construct or a viral construct containing a dominant negative construct (ΔJunD). At least 1 wk after NTS microinjection, a telemetry transmitter was implanted. At least 1 wk elapsed between telemetry implantation and data collection. Data were collected for a 7-day control period followed by a 7-day exposure to IH. On the day after the seventh day of exposure to IH, rats were anesthetized and brains were harvested.

NTS microinjections.

With the use of aseptic conditions, rats were kept on a heating pad placed in a stereotaxic frame with the head flexed to 45° and ventilated using a nose cone with room air supplemented with O2 and isoflurane (2%) for inhalation anesthesia. The elimination of the withdrawal reflex to a hindpaw pinch was used as a sign of adequate anesthesia. A limited occipital craniotomy was performed to expose the hindbrain at the level of calamus scriptorius. Injections of 100 nl were made over a 5-min period at three sites 0.5 mm below the surface of the brain (midline, 0.5 mm caudal to the calamus, and bilaterally 0.5 mm rostral to the calamus and 0.5 mm lateral to the midline) using a glass micropipette (tip diameter: 50 μm) connected to pneumatic picopump (PV 800, WPI, Sarasota, FL). An adeno-associated viral (serotype 2) construct expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) and ΔJunD (AAV-GFP-ΔJunD) or an adeno-associated viral construct expressing GFP only as a control (AAV-GFP) was injected. The titer of the vectors averaged 2.0 × 107 infectious units/ml. The dominant negative construct ΔJunD is a truncated form of JunD that binds with Fos proteins, but the resultant heterodimers lack transcriptional activity. It also does not distinguish ΔFosB from FosB, but ΔFosB is the predominant form with the longest half-life (21, 23–26, 42) so for the sake of simplicity we refer to ΔFosB throughout this article. All viral constructs were kindly provided by Dr. Eric J. Nestler (Mount Sinai Medical Center). The presence of GFP fluorescence identifies neurons that were successfully transfected and the construct incorporated to enable expression of GFP. After surgery, rats were placed in cages warmed by a radiant light and monitored while recovering from anesthesia. Rimadyl (0.5 mg, bacon-flavored tablet) was placed in the cage for postoperative analgesia.

Telemetry implantation.

One week after CNS microinjections, rats were implanted with an abdominal aortic catheter attached to a TA11PA-C40 radiotelemetry transmitter while they were under isoflurane (2%) inhalation anesthesia with the use of an aseptic technique. The transmitter was secured to the abdominal muscle with sterile suture and was maintained in the abdominal cavity during entire postsurgical recovery, normoxia, and IH condition. The Dataquest A.R.T 2.2 telemetry system (Data Sciences, St. Paul, MN) monitored MAP, heart rate (HR), respiratory frequency, and activity as previously described (1, 13, 16, 18). Rats were allowed to recover from all surgical procedures for 1 wk before the data collection began. Baseline data were collected for 7 days before the IH exposure and during 7 days of exposure to IH. Arterial pressure (AP) measurements obtained during a 10-s sampling period (500 Hz) were averaged and recorded in 10-min intervals. Pulse interval and fluctuations obtained from the AP waveform were used to calculate HR and respiratory frequency, respectively. MAP, HR, and respiratory frequency were averaged for every hour in the 24-h period, and the 1-h averages were then averaged during the period of exposure to IH (8 AM to 4 PM) and during the dark period (7 PM to 7 AM).

IH protocol.

Rats were individually housed in cages for a week after arrival. After surgery and recovery, rats were placed in custom-built Plexiglas chambers connected to the IH system. The IH system has been previously described (2, 14, 15). Briefly, the fraction of inspired O2 was reduced from 21% to 10% in 105 s, held at 10% for 75 s, returned to 21% in 105 s, and then held at 21% for 75 s. Each complete cycle lasted 6 min; therefore, there were 10 periods of IH per hour. Rats were exposed to IH for 8 h during the light period (8 AM to 4 PM), so they were exposed to a total of 80 IH cycles/day. Chambers were maintained at room air (21% O2) throughout the remaining 4 h of the light period and the entire dark period (12 h).

Immunohistochemistry.

Rats were anesthetized with thiobutabarbital (100 mg/kg ip Inactin, catalog no. MFCD00214068, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and were transcardially perfused with 0.1 M PBS followed by 300–500 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS in the morning after the last IH exposure. Brains were postfixed in PFA at room temperature for 1–2 h and then transferred into 30% sucrose at 4°C for dehydration until submerged. Each brain was embedded in cutting compound (Tissue TEK OCT, Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA), and coronal 40-μm sections were cut using a cryostat microtome (Leica CM1950, Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL). All sections were stored in cryoprotectant at −20°C (16) until processed for immunohistochemistry. Brain stem sections were incubated in goat polyclonal anti-FosB (1:5,000, sc-48-G, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) at 4°C for 48 h. The anti-FosB antibody does not discriminate full-length FosB from the splice variant ΔFosB. Sections were then processed with biotinylated horse anti-goat IgG (1:100, BA-9500, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and reacted with an avidin-peroxidase conjugate (Vectastain ABC Kit, PK-4000, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 1 h and then treated with PBS containing 0.04% nickel ammonium sulfate and 0.04% 3,3′-diaminobenzidine hydrochloride for 11 min. Brain stem sections (−13.68 to −14.60 from the bregma) were also processed with mouse anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) primary antibody (1:1,000, MAB318, Millipore) and CY3-labeled donkey anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:1,200, no. 715-165-150, Jackson ImmunoResearch). Forebrain sections were processed for FosB/ΔFosB staining as described above. Sections were mounted on gelatin-coated slides, air dried for 2 days, and then coverslipped with Permount. Sections were visualized under an Olympus microscope (BX41) equipped for epifluorescence and an Olympus DP70 digital camera with DP manager software (version 2.2.1). Images were uniformly adjusted for brightness and contrast. The rat brain stereotaxic atlas of Paxinos and Watson (29) was used to identify specific regions. All counts were performed using ImageJ software (version 1.44, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Sections double labeled for TH-FosB were used to count FosB/ΔFosB immunoreactivity in the RVLM (−11.8 to −12.72 from the bregma). ΔFosB-immunoreactive neurons were counted in 9−10 sections of the NTS, 9−10 sections of the RVLM, and 5−6 sections of the PVN (−1.30 to −2.12 from the bregma) (2−3 sections per rat/subnuclei dorsal parvocellular, medial parvocellular, lateral parvocellular, and posterior magnocellular) from each rat. The number of immunoreactive neurons in the RVLM and PVN subnuclei per section was averaged for each rat, and these were then averaged to obtain group means. Neurons with immunoreactivity for both ΔFosB and TH were also counted in the RVLM.

Data analysis and statistics.

Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA and Student-Neuman-Keuls posthoc analysis were used to compare the difference between absolute values of baseline and daily measurements of MAP, HR, respiratory frequency, and activity over the 7 days of IH. Responses during 8-h exposure to IH and the dark phase were analyzed separately. FosB/ΔFosB immunoreactivity counts in the PVN and RVLM across different groups were compared by one-way ANOVA with the Student-Neuman-Keuls test for post hoc analysis. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Effects of dominant negative ΔFosB construct on responses to IH in conscious rats.

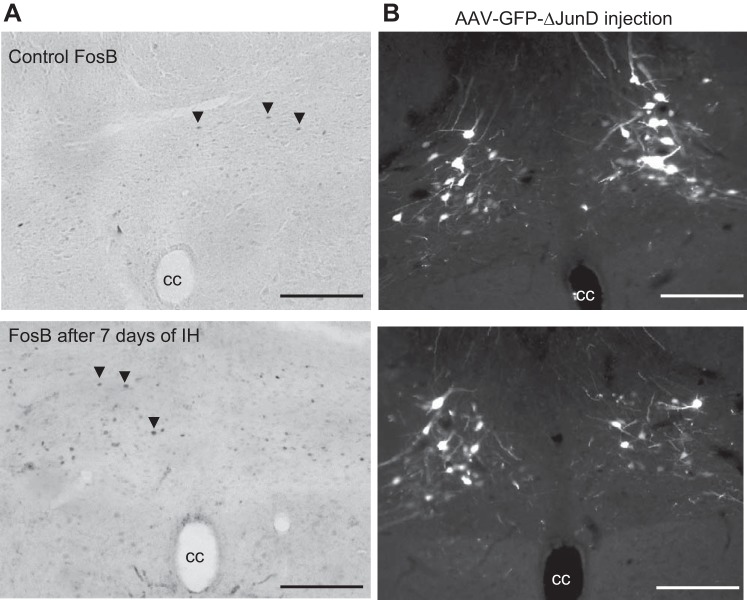

Histological examination of the injection sites showed that the AAV construct produced intense GFP labeling in the NTS (Fig. 1B). GFP labeling generally overlapped NTS regions that expressed ΔFosB immunoreactivity after a 7-day exposure to IH (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

A: ΔFosB immunoreactivity in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) under control conditions (top) and after a 7-day exposure to intermittent hypoxia (IH; bottom). B: examples of green fluorescent protein (GFP)-labeled NTS neurons after injection of a dominant negative construct (ΔJunD). Note the overlap with neurons expressing ΔFosB in A. Sections are from 13.68 to 14.60 posterior to the bregma. cc, Central canal. Scale bars = 100 μm.

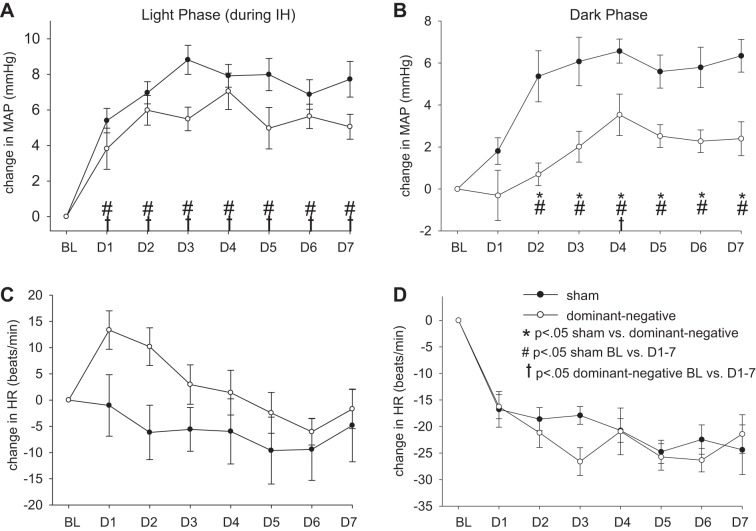

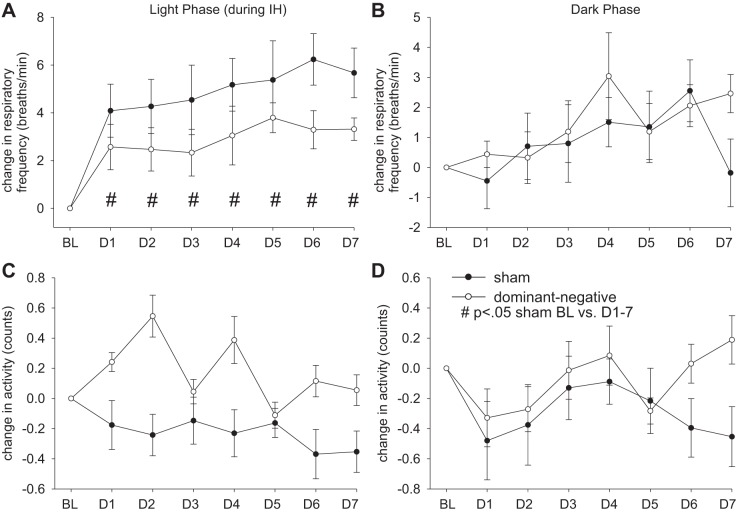

Figures 2 and 3 show averaged changes in MAP, HR, respiratory frequency, and activity before and during exposure to IH from 8 AM to 4 PM and during the dark from 7 PM to 7 AM in conscious rats that received an NTS injection of sham (AAV-GFP, n = 10) or dominant negative (AAV-GFP-ΔJunD, n = 11) construct. Three days of control baseline values were averaged to obtain a control value in both groups of rats. The change from baseline was plotted for each day of exposure to IH. For all parameters measured, there was no significant difference between the baseline control values between the sham and dominant negative groups during the same time of day as exposure to IH (8 AM to 4 PM) or the dark phase (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Effect of dominant negative inhibition of ΔFosB in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) on changes in mean arterial pressure (MAP; A and B) and heart rate (HR; C and D) during the 8-h exposure to intermittent hypoxia (IH; A and C) and during the 12 h of dark (B and D). ●, rats that received injections of adeno-associated viral vector (AAV)-green fluorescent protein (GFP) (sham; n = 10); ○, rats that received injections of AAV-GFP-ΔJunD (dominant negative; n = 11). Normoxic baseline (BL) values were averaged for the 3 days before exposure to IH; the change in MAP and HR for each day of IH is plotted for days 1–7 (D1–D7). Marked significances represent results of statistical comparisons of absolute values. *P < 0.05 for sham vs. dominant negative; #P < 0.05 for sham BL vs. D1–7; †P < 0.05 dominant negative BL vs. D1–7.

Fig. 3.

Effect of dominant negative inhibition of ΔFosB in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) on changes in respiratory frequency (A and B) and activity (C and D) during the 8-h exposure to intermittent hypoxia (IH; A and C) and during the 12 h of dark (B and D). ●, rats that received injections of adeno-associated viral vector (AAV)-green fluorescent protein (GFP) (sham; n = 10); ○, rats that received injections of AAV-GFP-ΔJunD (dominant negative, n = 11). Normoxic baseline (BL) values were averaged for the 3 days before exposure to IH; the change in respiratory frequency and activity for each day of IH is plotted for days 1–7 (D1–D7). Marked significances represent results of statistical comparisons of absolute values. #P < .05 for sham BL vs. D1–7.

Table 1.

Baseline values of mean arterial pressure, heart rate, respiratory frequency, and activity

| Light, During Intermittent Hypoxia |

Dark |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham | Dominant negative | Sham | Dominant negative | |

| Mean arterial pressure, mmHg | 100 ± 1 | 96 ± 2 | 104 ± 1 | 101 ± 2 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 324 ± 6 | 313 ± 6 | 380 ± 6 | 370 ± 6 |

| Respiratory frequency, breaths/min | 98 ± 2 | 91 ± 3 | 100 ± 2 | 94 ± 2 |

| Activity, counts/mn | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 3.3 ± 0.3 | 3.2 ± 0.3 |

Values are means ± SE. There were no differences between sham versus dominant negative values for any parameter compared during intermittent hypoxia and in the dark.

There was an interaction for MAP during IH (treatment × day interaction, P < 0.05). Followup analysis of the interaction indicated that MAP during IH was significantly higher on all days of IH compared with baseline in both sham and dominant negative groups (P < 0.001; Fig. 2A). There was also an interaction for MAP during the dark (treatment × day interaction, P < 0.05). MAP in the sham group was significantly higher compared with baseline on all days of IH (P < 0.001) with the exception of IH day 1 but was only significantly elevated on IH day 4 (P < 0.05) in the dominant negative group. The dominant negative group showed a significantly reduced IH-induced increase in MAP compared with the sham group during the dark (P < 0.001; Fig. 2B). During IH, the dominant negative group also showed an attenuation of the elevated MAP compared with the sham group (P < 0.05; Fig. 2B).

During IH, HR was significantly influenced by the treatments (treatment × day interaction, P < 0.05). On IH days 1−4, there was no significant difference from the baseline level, whereas on IH days 5−7, HR significantly decreased compared with baseline in the AAV-GFP group (P < 0.05; Fig. 2C). On IH days 1 and 2, HR was significantly increased in the dominant negative group compared with baseline (P < 0.05; Fig. 2C) but was not significantly different on the other IH days. In the dark, HR was not significantly influenced by the treatments (treatment × day interaction, P > 0.05; Fig. 2D). There was no significant difference in HR between the two groups in either the light phase or dark phase (Fig. 2, C and D).

During exposures to IH, respiratory frequency was increased in the sham group but not in the dominant negative group (Fig. 3A). There were no significant interactions for respiratory frequency both during IH and in the dark (treatment × day interaction, P > 0.05). There was no significant difference in respiratory frequency between two groups in either the light phase or dark phase (Fig. 3, A and B).

Activity in the light period was significantly influenced by interactions (treatment × day interaction, P < 0.05). Activity significantly decreased on all IH days compared with baseline in the light phase in sham rats (P < 0.001; Fig. 3C) but significantly increased in dominant negative rats (P < 0.05; Fig. 3C). No significant interactions existed in the dark (treatment × day interaction, P > 0.05). There was no significant difference between sham and dominant negative groups in either the light phase or dark phase (Fig. 3, C and D).

Effects of the dominant negative construct in the NTS on ΔFosB immunoreactivity in the RVLM and PVN.

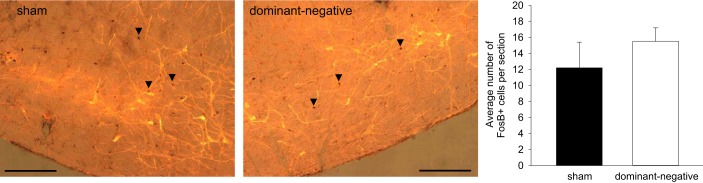

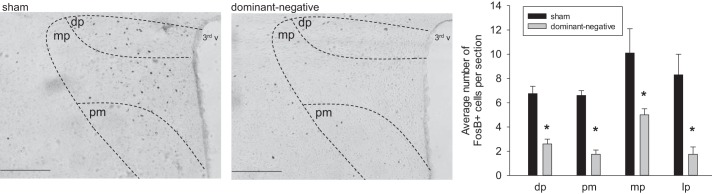

To further determine the effects of dominant negative inhibition of NTS ΔFosB on the chronic transcriptional activation of autonomic regulatory regions of the CNS during IH, ΔFosB immunoreactivity was examined in the RVLM and PVN. There was no difference in the number of ΔFosB-immunoreactive neurons in the RVLM after a 7-day exposure to IH after injection of the dominant negative construct into the NTS (Fig. 4). While ΔFosB staining in the RVLM was intermingled with TH-positive neurons, there was no significant colocalization of ΔFosB with TH (sham: 0.1 ± 0.04 and dominant negative: 0.4 ± 0.1). Injection of the dominant negative construct in the NTS significantly decreased the number of ΔFosB-immunoreactive neurons in the PVN compared with the sham group (sham: 21.0 ± 4.7 and dominant negative: 10.8 ± 1.8, n = 7 in each group; Fig. 5). Analysis of the PVN subregions revealed significant reductions in dorsal parvocellular, medial parvocellular, lateral parvocellular, and posterior magnocellular subnuclei (P < 0.05; Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Superimposed images of ΔFosB immunoreactivity (brown circles; arrows indicate examples of ΔFosB-immunoreactive nuclei) and tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactivity (yellow neurons and fibers) in the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) region from a rat that received injection of adeno-associated viral vector (AAV)-green fluorescent protein (GFP) (sham; left) and from a rat that received injection of AAV-GFP-ΔJunD (dominant negative; right). Both rats were exposed to 7 days of intermittent hypoxia (IH). The histogram at the bottom shows the mean number of ΔFosB-immunoreactive cells counted in the RVLM (11.80 to 12.72 posterior to the bregma). Scale bars = 100 um. n = 7 sham and 7 dominant negative.

Fig. 5.

ΔFosB immunoreactivity in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN) from a rat that received injection of adeno-associated viral vector (AAV)-green fluorescent protein (GFP) (sham; left) and from a rat that received injection of AAV-GFP-ΔJunD (dominant negative; right). Both rats were exposed to 7 days of intermittent hypoxia (IH). Sections are from 1.30 to 2.12 posterior to the bregma. The histogram at the bottom shows the mean number of ΔFosB-immunoreactive cells counted in various subnuclei of the PVN [dorsal parvocellular (dp), medial parvocellular (mp), posterior magnocellular (pm), and lateral parvocellular (lp)]. Scale bars = 200 μm. n = 7 sham and 7 dominant negative.

DISCUSSION

The results of the present study provide the first evidence showing that, in the NTS, the transcription factor ΔFosB plays an important role in IH-induced hypertension. Functional antagonism of ΔFosB in the NTS did not reduce IH-induced increased MAP during the period of the day when rats were exposed to IH. However, the persistent increase in MAP during the dark, when rats were in normoxic environmental conditions, was significantly reduced by functional antagonism of ΔFosB in the NTS. These results indicate that ∆FosB acting within the NTS is necessary for the persistent hypertensive response to IH during normoxia.

We studied rats exposed to IH for 7 days to determine factors that play an important role in the initiation of the pathological responses to IH. Such studies are virtually impossible in sleep apnea patients, who typically seek assistance only after months to years after the onset of the condition.

The persistent increase in MAP observed during the dark averaged 5–8 mmHg. This should not be considered a trivial increase in MAP as the Framingham study found that long-term reduction of diastolic blood pressure by only 5–6 mmHg reduced the risk of stroke by 35–40% and risk of coronary artery disease by 20–25% (39). Furthermore, the magnitude of the increase in MAP after a 7-day exposure to IH is similar to the reduction in MAP that occurs when sleep apnea patients are treated with continuous positive airway pressure (2, 22, 27). It is important to note that blood pressure responses to systemic hypoxia ultimately represent the combination of disparate factors competing at the level of the neurovascular unit. Arterial chemoreceptor-evoked increases in SND interact with the direct vasodilator effects of hypoxia. Increased SND is certainly a significant factor, in addition to increased MAP and MAP lability, in the overall pathology of sleep apnea (38).

There are some technical limitations to consider. The viral construct may have been expressed in NTS neurons that are not involved in the responses to IH. However, since ΔFosB is only expressed in neurons with chronic, intermittently increased discharge, we do not consider this a major limitation. There may be effects on NTS neurons that do not necessarily receive arterial chemoreceptor inputs. For example, NTS neurons receiving baroreceptor afferent inputs might be affected as exposure to IH increases AP. It is difficult to determine the extent to which this might influence our results; however, we have previously reported that after a 7-day exposure to IH, baroreflex regulation of renal sympathetic nerve discharge and HR were shifted toward higher pressures with no change in maximal gain, suggesting that 7 days of IH was associated with a resetting of the operating pressure range but no change in sensitivity of the arterial baroreflex (41). A further limitation is that we could not determine the degree of ΔFosB inhibition as the dominant negative construct is a functional antagonist, not a knockdown. ΔFosB is still produced, but the construct results in dimerization to produce a heterodimer incapable of binding to the AP-1 site.

IH and obstructive sleep apnea alter both the peripheral (32, 33) and central (6, 15, 33, 43) components of the arterial chemoreflex and lead to increased sympathetic nerve activity and hypertension. A 7-day exposure to IH increases AP (1, 4, 13, 16, 18, 36) during both the daytime and nighttime and also increases ΔFosB immunoreactivity in CNS autonomic and endocrine regulatory regions such as the NTS, PVN, and RVLM (16), suggesting a causal link between ΔFosB expression and IH-induced hypertension. Our study demonstrates that after inhibition of ΔFosB function in the NTS by the dominant negative construct, IH-induced hypertension was reduced during the nighttime when rats were exposed to room air. Therefore, ΔFosB in the NTS plays a role in IH-induced hypertension.

A previous study used dominant negative inhibition of ΔFosB in the MnPO to test how transcriptional activation in this region associated with IH influenced downstream targets such as the PVN and RVLM (3). We used a similar functional anatomical mapping approach to investigate how dominant negative inhibition of ΔFosB in the NTS during IH affects the same regions. Inhibition of NTS ΔFosB reduced ΔFosB immunoreactivity in the PVN but not in the RVLM. This suggests that at least some ΔFosB in the PVN induced by IH is dependent on ΔFosB in the NTS, whereas ΔFosB in the RVLM is not. The lack of change in the RVLM is surprising as it is known glutamatergic inputs from the NTS to RVLM play an important role in chemoreflex sympathoexcitation (12). However, our dominant negative injections did not totally abolish the increases in blood pressure that were observed during the IH exposures from 8 AM to 4 PM. It is possible that the increases in blood pressure during the IH are mediated by the RVLM through a ΔFosB-independent mechanism. In our previous study, shRNA knockdown of TH in the NTS produced similar effects on IH-induced hypertension and ΔFosB staining in the PVN and RVLM (1). This suggests that TH and ΔFosB may contribute to a common mechanism at the level of the NTS associated with IH. This substrate would be necessary for IH-mediated ΔFosB staining in the PVN but not the RVLM. Blood pressure increases during the diurnal, IH component of the protocol would also be independent of NTS TH and ΔFosB, whereas it is necessary for the sustained increase in blood pressure that carries through the normoxic dark phase. It is also important to remember that ΔFosB is one of the transcription factors that can alter neuronal function. Functional blockade of ΔFosB in the MnPO reduced IH-induced hypertension and ΔFosB immunoreactivity in the PVN and RVLM (4), so perhaps during IH ΔFosB in the RVLM is driven by PVN inputs. Alternatively, ΔFosB in the RVLM may be generated in response to local tissue hypoxia during IH. Consistent with our previous studies, we found little evidence of colocalization of ΔFosB and TH within the RVLM (1, 16). Perhaps non-TH RVLM neurons exhibiting ΔFosB after IH might be involved in other aspects of the response to IH, e.g., respiration, upper airway patency, insulin resistance, etc.

Inhibition of FosB function in the NTS did not significantly alter the IH-induced increase in MAP during the day when rats were exposed to IH but did lower MAP during the dark when rats were at normoxic levels. This suggests that the NTS input to the PVN might have a greater contribution to the dark phase elevation of blood pressure, whereas the NTS input to the RVLM might be more involved during the light phase period of IH exposure. To this point, there is evidence that the NTS input to the PVN during acute hypoxia is primarily involved in activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and not sympathetic outflow (3).

In conclusion, ΔFosB in the NTS contributes to IH-induced hypertension, although the underlying mechanisms whereby ΔFosB might alter NTS neuronal function are yet to be determined. AP-1 DNA-binding sites regulate a number of cellular processes, and it is reasonable to suggest that the effects of ΔFosB are mediated by processes that enhance NTS neuronal excitability such as increased responsivity to excitatory transmitters and/or reduced responsivity to inhibitory transmitters (20, 21). Any or all of these adaptations could increase the sympathoexcitatory and pressor drive originating from NTS neurons receiving arterial chemoreceptor inputs.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant P01-HL-088052 and American Heart Association Pre-Doctoral Fellowship 13PRE16970013.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.W.M. conceived and designed research; Q.W. and S.W.M. performed experiments; Q.W. and S.W.M. analyzed data; Q.W., J.T.C., and S.W.M. interpreted results of experiments; Q.W. and S.W.M. prepared figures; Q.W. and S.W.M. drafted manuscript; Q.W., J.T.C., and S.W.M. edited and revised manuscript; Q.W., J.T.C., and S.W.M. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Eric Nestler (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai) for providing the dominant negative viral construct.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bathina CS, Rajulapati A, Franzke M, Yamamoto K, Cunningham JT, Mifflin S. Knockdown of tyrosine hydroxylase in the nucleus of the solitary tract reduces elevated blood pressure during chronic intermittent hypoxia. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 305: R1031–R1039, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00260.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Becker HF, Jerrentrup A, Ploch T, Grote L, Penzel T, Sullivan CE, Peter JH. Effect of nasal continuous positive airway pressure treatment on blood pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Circulation 107: 68–73, 2003. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000042706.47107.7A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coldren KM, Li D-P, Kline DD, Hasser EM, Heesch CM. Acute hypoxia activates neuroendocrine, but not presympathetic, neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus: differential role of nitric oxide Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 312: R982–R995, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00543.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cunningham JT, Knight WD, Mifflin SW, Nestler EJ. An essential role for deltaFosB in the median preoptic nucleus in the sustained hypertensive effects of chronic intermittent hypoxia. Hypertension 60: 179–187, 2012. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.193789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Paula PM, Tolstykh G, Mifflin S. Chronic intermittent hypoxia alters NMDA and AMPA-evoked currents in NTS neurons receiving carotid body chemoreceptor inputs. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 292: R2259–R2265, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00760.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fletcher EC. Sympathetic over activity in the etiology of hypertension of obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep 26: 15–19, 2003. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fletcher EC, Lesske J, Behm R, Miller CC 3rd, Stauss H, Unger T. Carotid chemoreceptors, systemic blood pressure, and chronic episodic hypoxia mimicking sleep apnea. J Appl Physiol 72: 1978–1984, 1992. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.72.5.1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fletcher EC, Lesske J, Qian W, Miller CC 3rd, Unger T. Repetitive, episodic hypoxia causes diurnal elevation of blood pressure in rats. Hypertension 19: 555–561, 1992. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.19.6.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenberg HE, Sica A, Batson D, Scharf SM. Chronic intermittent hypoxia increases sympathetic responsiveness to hypoxia and hypercapnia. J Appl Physiol 86: 298–305, 1999. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.86.1.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guyenet PG. Neural structures that mediate sympathoexcitation during hypoxia. Respir Physiol 121: 147–162, 2000. doi: 10.1016/S0034-5687(00)00125-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guyenet PG. The sympathetic control of blood pressure. Nat Rev Neurosci 7: 335–346, 2006. doi: 10.1038/nrn1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hinojosa-Laborde C, Mifflin SW. Sex differences in blood pressure response to intermittent hypoxia in rats. Hypertension 46: 1016–1021, 2005. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000175477.33816.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kapa S, Sert Kuniyoshi FH, Somers VK. Sleep apnea and hypertension: interactions and implications for management. Hypertension 51: 605–608, 2008. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.106.076190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kline DD, Ramirez-Navarro A, Kunze DL. Adaptive depression in synaptic transmission in the nucleus of the solitary tract after in vivo chronic intermittent hypoxia: evidence for homeostatic plasticity. J Neurosci 27: 4663–4673, 2007. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4946-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knight WD, Little JT, Carreno FR, Toney GM, Mifflin SW, Cunningham JT. Chronic intermittent hypoxia increases blood pressure and expression of FosB/DeltaFosB in central autonomic regions. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 301: R131–R139, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00830.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knight WD, Saxena A, Shell B, Nedungadi TP, Mifflin SW, Cunningham JT. Central losartan attenuates increases in arterial pressure and expression of FosB/ΔFosB along the autonomic axis associated with chronic intermittent hypoxia. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 305: R1051–R1058, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00541.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Konecny T, Kara T, Somers VK. Obstructive sleep apnea and hypertension: an update. Hypertension 63: 203–209, 2014. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.00613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McClung CA, Nestler EJ. Neuroplasticity mediated by altered gene expression. Neuropsychopharmacology 33: 3–17, 2008. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McClung CA, Ulery PG, Perrotti LI, Zachariou V, Berton O, Nestler EJ. DeltaFosB: a molecular switch for long-term adaptation in the brain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 132: 146–154, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mills PJ, Kennedy BP, Loredo JS, Dimsdale JE, Ziegler MG. Effects of nasal continuous positive airway pressure and oxygen supplementation on norepinephrine kinetics and cardiovascular responses in obstructive sleep apnea. J Appl Physiol 100: 343–348, 2006. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00494.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nestler EJ. Is there a common molecular pathway for addiction? Nat Neurosci 8: 1445–1449, 2005. doi: 10.1038/nn1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nestler EJ. Molecular basis of long-term plasticity underlying addiction. Nat Rev Neurosci 2: 119–128, 2001. doi: 10.1038/35053570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nestler EJ. Molecular neurobiology of addiction. Am J Addict 10: 201–217, 2001. doi: 10.1080/105504901750532094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nestler EJ, Barrot M, Self DW. DeltaFosB: a sustained molecular switch for addiction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 11042–11046, 2001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191352698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Norman D, Loredo JS, Nelesen RA, Ancoli-Israel S, Mills PJ, Ziegler MG, Dimsdale JE. Effects of continuous positive airway pressure versus supplemental oxygen on 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure. Hypertension 47: 840–845, 2006. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000217128.41284.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olivan MV, Bonagamba LG, Machado BH. Involvement of the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus in the pressor response to chemoreflex activation in awake rats. Brain Res 895: 167–172, 2001. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(01)02067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates (6th ed.). New York: Academic, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peng YJ, Prabhakar NR. Effect of two paradigms of chronic intermittent hypoxia on carotid body sensory activity. J Appl Physiol 96: 1236–1242, 2004. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00820.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peng YJ, Prabhakar NR. Reactive oxygen species in the plasticity of respiratory behavior elicited by chronic intermittent hypoxia. J Appl Physiol 94: 2342–2349, 2003. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00613.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peng Y, Kline DD, Dick TE, Prabhakar NR. Chronic intermittent hypoxia enhances carotid body chemoreceptor response to low oxygen. Adv Exp Med Biol 499: 33–38, 2001. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1375-9_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramirez JM, Garcia AJ 3rd, Anderson TM, Koschnitzky JE, Peng YJ, Kumar GK, Prabhakar NR. Central and peripheral factors contributing to obstructive sleep apneas. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 189: 344–353, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reddy MK, Patel KP, Schultz HD. Differential role of the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus in modulating the sympathoexcitatory component of peripheral and central chemoreflexes. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 289: R789–R797, 2005. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00222.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shamsuzzaman AS, Gersh BJ, Somers VK. Obstructive sleep apnea: implications for cardiac and vascular disease. JAMA 290: 1906–1914, 2003. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.14.1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharpe AL, Calderon AS, Andrade MA, Cunningham JT, Mifflin SW, Toney GM. Chronic intermittent hypoxia increases sympathetic control of blood pressure: role of neuronal activity in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 305: H1772–H1780, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00592.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Silva AQ, Schreihofer AM. Altered sympathetic reflexes and vascular reactivity in rats after exposure to chronic intermittent hypoxia. J Physiol 589: 1463–1476, 2011. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.200691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spaak J, Egri ZJ, Kubo T, Yu E, Ando S, Kaneko Y, Usui K, Bradley TD, Floras JS. Muscle sympathetic nerve activity during wakefulness in heart failure patients with and without sleep apnea. Hypertension 46: 1327–1332, 2005. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000193497.45200.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Staessen JA, Wang JG, Birkenhäger WH. Outcome beyond blood pressure control? Eur Heart J 24: 504–514, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S0195-668X(02)00797-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xie W, Zheng F, Song X. Obstructive sleep apnea and serious adverse outcomes in patients with cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease: a PRISMA-compliant systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 93: e336, 2014. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamamoto K, Eubank W, Franzke M, Mifflin S. Resetting of the sympathetic baroreflex is associated with the onset of hypertension during chronic intermittent hypoxia. Auton Neurosci 173: 22–27, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zachariou V, Bolanos CA, Selley DE, Theobald D, Cassidy MP, Kelz MB, Shaw-Lutchman T, Berton O, Sim-Selley LJ, Dileone RJ, Kumar A, Nestler EJ. An essential role for DeltaFosB in the nucleus accumbens in morphine action. Nat Neurosci 9: 205–211, 2006. doi: 10.1038/nn1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang W, Carreño FR, Cunningham JT, Mifflin SW. Chronic sustained and intermittent hypoxia reduce function of ATP-sensitive potassium channels in nucleus of the solitary tract. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 295: R1555–R1562, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90390.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]