Abstract

Studying human hepatotropic pathogens such as hepatitis B and C viruses and malaria will be necessary for understanding host-pathogen interactions, and developing therapy and prophylaxis. Unfortunately, existing in vitro liver models typically employ either cell lines that exhibit aberrant physiology, or primary human hepatocytes in culture configurations wherein they rapidly lose their hepatic functional phenotype. Stable, robust, and reliable in vitro primary human hepatocyte models are needed as platforms for infectious disease applications. For this purpose, we describe the application of micropatterned co-cultures (MPCCs), which consist of primary human hepatocytes organized into 2D islands that are surrounded by supportive cells. Using this system, we demonstrate how to recapitulate in vitro liver infection by the hepatitis B and C viruses and Plasmodium pathogens. In turn, the MPCC platform can be used to uncover aspects of host-pathogen interactions, and has the potential to be used for medium-throughput drug screening and vaccine development.

INTRODUCTION

Liver pathogens collectively mount an enormous global burden on human health; hepatitis B virus (HBV) chronically infects the livers of >250 million people worldwide, hepatitis C virus (HCV) chronically infects the livers of 130-170 million more, and the Plasmodium protozoan underlying malaria matures within the liver during its infection of over 250 million individuals globally. Although the two viruses exhibit very distinct genome structures and life cycles, HCV and HBV both utilizes parenteral transmission, after which they establish chronic infection in the hepatocyte, the main parenchymal cell type of the liver. Infection gradually mounts in the liver, leading to fibrosis and ultimately end-stage liver diseases such as cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma1,2 Malaria is transmitted by Plasmodium sporozoites after they are injected into a human host via a mosquito vector. These uninucleate sporozoites invade hepatocytes, where they establish exoerythrocytic forms (EEFs) that mature and multiply to form schizonts which eventually release thousands of pathogenic merozoites into the blood. Merozoites invade erythrocytes and lead to the major clinical symptoms, signs, and pathology of malaria. While clinical management of these hepatotropic pathogens has made strides in recent years, there is much room for improvement. While a safe and effective HBV vaccine exists, incomplete penetrance of immunization allows disease burden to grow, and current antivirals for HBV cannot cure chronically infected patients. Prophylactic options for HCV remain unavailable, and current therapeutic regimens are subject to emergence of resistance, side effects, and high costs3. For malaria, limited options for prophylaxis are available, only a few drugs target liver-stage parasites, resistance is a growing problem, and only one licensed drug eliminates the dormant hypnozoite form of the pathogen which causes clinical relapses4–6.

An improved understanding of the biology of HBV, HCV and the Plasmodium pathogens, and their pathogenesis within human hosts, will drive improvements in the clinic. However, despite impressive advances in our understanding of these pathogens and their infection of human hosts, much remains unknown due to limitations in existing model systems available for their study. Due to the narrow species tropism of HBV and HCV, the only robust animal model is the chimpanzee, which is costly and often inaccessible. While exciting progress is being made in the development of liver-humanized mouse models of hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and malaria, these tools are still generally restricted to a small number of research labs7,8, and their reproducibility and reliability need to be further demonstrated. As such, the majority of research programs tackling these diseases typically employ in vitro models of the liver9.

While conventional in vitro liver models utilizing confluent hepatocyte monolayers and extracellular matrix (ECM) manipulations (such as collagen and Matrigel) do exist10–12, they suffer from a variety of limitations as described below. Thus, there is need for an updated in vitro liver model of functionally stable primary human hepatocytes that can be used to evaluate the chronic aspects of the aforementioned diseases. In this paper, we discuss the development and use of an in vitro culture technology called micropatterned co-cultures (MPCCs), which we have developed, optimized, and applied to various problems in human health over the last 10 years13–16. This co-culture system of primary human hepatocytes and J2-3T3 murine embryonic fibroblasts is robust, reproducible, and easy-to-use in a standard multi-well plate format, sustaining hepatocytes for 4-6 weeks in culture. Primary human hepatocytes can be sourced both fresh and cryopreserved from many human donors and are then qualified for use in downstream applications. We have successfully used MPCCs to study the infection and drug response for HBV, HCV, and malaria, as well as uncover novel infection biology.

Development of the protocol

The development of MPCCs was inspired by early work focused on the role of physical homotypic (hepatocyte-hepatocyte) and heterotypic (hepatocyte-stromal) cell-cell interactions modulating hepatocyte functions in vitro. In particular, pioneering studies by Guguen-Guillouzo and colleagues demonstrated transient induction of some functions in primary human hepatocytes co-cultivated with an epithelial cell type, also derived from the liver17. However, in these early studies, the two cell types were randomly distributed onto planar surfaces, which did not allow exploration of the role of controlled cell-cell interactions on the hepatic phenotype without the confounding variable of cell seeding density. To circumvent this limitation, Bhatia and colleagues employed photolithography adapted from the semiconductor industry to physically position defined, 2D islands of primary rat hepatocytes on adsorbed collagen surrounded by supportive J2-3T3 murine embryonic fibroblasts13. Such micropatterning allowed tuning of the relative levels of homo- and heterotypic interactions while keeping cell numbers and ratios between the two cell types constant across the various patterned configurations. These experiments revealed that defining various levels of homotypic cell-cell interactions alone played a critical role in modulating hepatocyte functions by several fold. Functions of micropatterned hepatocyte colonies were then significantly augmented in both magnitude and longevity by contact co-culture with stromal cells13. In particular, a functional screen revealed that the J2 sub-clone of 3T3 murine embryonic fibroblasts (J2-3T3) induced optimal functions in hepatocytes from multiple species (rat, human) as compared to other available 3T3 clones (i.e. NIH-3T3, Swiss-3T3, L1-3T3)18.

Given significant differences between animals and humans in liver functions19–21, Khetani and Bhatia then applied the aforementioned micropatterning configurations to freshly isolated primary human hepatocytes. Interestingly, a different balance of homotypic and heterotypic interactions was needed to induce optimal functions in human hepatocytes co-cultivated with J2-3T3 fibroblasts as compared to their rat counterparts14. Another significant advance was to develop soft-lithographic techniques that allowed for rapid creation of MPCCs in miniaturized formats for higher throughput screening than afforded by the serial process of photolithography for direct seeding of cells14. Furthermore, MPCC creation protocols were optimized by investigators at Hepregen Corporation (Medford, MA) to leverage advances in production of cryopreserved primary human hepatocytes by multiple vendors (i.e. Life Technologies, BioreclamationIVT, Corning). The use of cryopreserved hepatocytes affords several advantages which include: convenient on-demand experimentation as opposed to the unpredictability in procurement of fresh cells; longitudinal studies in the same donor when required as opposed to significant inter-experimental variability observed with use of fresh hepatocytes from different donors; and comparisons across responses in multiple donors for specific downstream applications. All of the aforementioned advances have culminated in modern day MPCCs which have been optimized for human hepatocyte functions in industry-standard 24- and 96-well formats (Figure 1, Figure 2). Current ‘best practice’ cultures consist of 500 μm islands (~200 hepatocytes per island), spaced 900-1200 μm apart center-to-center, with supportive murine J2-3T3 fibroblasts in the remaining spaces. Such architectures remain intact in both fidelity of patterning and hepatic morphology and functions for several weeks.

Figure 1. Schematic of MPCC fabrication, seeding, culture, and application for in vitro hepatotropic pathogen infection.

Left, fabrication of micro-patterned collagen islands inside wells of a 24- or 96-well plate. Center, MPCCs are formed by sequential seeding of primary human hepatocytes onto collagen islands and J2-3T3 fibroblasts onto intervening space around islands. Top right, quality control of MPCCs using integrated functional readouts. Bottom right, infection of MPCCs with various hepatotropic pathogens under different experimental perturbations to discover new biology and/or screen compounds for drug development.

Figure 2. Micropatterned co-cultures of hepatocytes and supportive fibroblasts.

Brightfield imaging of MPCCs constructed inside individual wells of a 96-well plate to facilitate medium-throughput screening. From left to right, progressively higher-magnification images of hepatocyte islands (H) surrounded by fibroblasts (J). Note the maintenance of hepatocyte morphology with small, bright circular nuclei, dark cytoplasm, and numerous bile canaliculi presenting as thin, white branches. Additional images can be seen in Khetani et al.36.

MPCCs have been used to study basic mechanisms underlying hepatocyte-stromal co-cultures, drug metabolism and toxicity22–26, and most recently, the life cycle of HCV15 and human Plasmodium16,27 pathogens. As MPCCs recapitulate the life cycle of these pathogens, they open the door to studying infection pathophysiology and drug response, as we will discuss below.

Applications of the method

One of the first applications of MPCCs was for preclinical evaluation of therapeutic drug candidate toxicity14,23. For instance, MPCCs have been shown to be ~70-75% predictive of clinical outcomes for drug metabolite and drug-induced liver toxicity profiling as opposed to <50% sensitivity in standard culture systems22. A more recent application of MPCCs has been the study of hepatotropic pathogens15,16,27,28. While the present report focuses on the use of MPCCs to study HBV, HCV and Plasmodium infection (Figure 1), this coculture platform can also be utilized to study hepatotropic pathogens broadly. Indeed, in our ongoing studies we have confirmed that it is possible to achieve dengue virus infection of MPCCs, and while to date we have not used the platform to study infection with HAV and HEV, these are interesting areas for future study. Following the demonstration that MPCCs support a pathogen’s life cycle, a natural extension of this in vitro system is its use in candidate drug and vaccine screening to determine efficacy against the target pathogen. In this case, data derived from the study of these drugs in MPCCs is likely to be more representative of the human population when using primary human hepatocytes from multiple donors rather than single transformed donors. Additionally, due to stable activities of drug metabolism enzymes (i.e. cytochrome P450s) and drug transporters, MPCCs allow simultaneous evaluation of drug metabolism/toxicity and efficacy of candidate compounds in the same hepatocytes15.

Furthermore, MPCCs can be used for basic biological explorations of host-pathogen interactions that are not easily recapitulated in cancerous and abnormal hepatic cell lines used in the field. As an example, we have recently used MPCCs to study the interplay between HBV/HCV/Plasmodium and the interferon axis present in hepatocytes, an inquiry which was previously challenging given the defective innate immune signaling exhibited by cell lines (manuscript in preparation). Another advantage of MPCCs is that hepatocytes exhibit polarized morphology over several weeks with appropriate localization of entry receptors and bile canaliculi, which in turn permit studies of cell-cell direct spread of HCV, for example14. Additionally, beyond rodents and humans, MPCCs have been established using hepatocytes from other species, including non-human primates 29,30. In the case of some pathogens, such as Plasmodium, the human-tropic species can be challenging to source. One approach that has been taken in some laboratories is to evaluate the biology of another malaria species, Plasmodium Cynomolgi, as a surrogate for Plasmodium vivax 31,32.

Liver research programs over the past few decades have been stymied by poor access to in vitro models with stable liver functional phenotype and appropriate polarization. Thus, beyond infection, MPCCs can also be used to study more broad questions of liver physiology and pathophysiology (e.g. cholesterol trafficking, carbohydrate regulation, production of serum components)33. Further, as exemplified by studying infection and other assessments of drug toxicity (e.g. acetaminophen)23, MPCCs allow the study of primary human hepatocytes under backgrounds of specific disease states. This capacity makes it likely that MPCCs will assist in studies of fatty liver, fibrosis, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency (particularly by collecting hepatocytes from genetic mutant backgrounds), and aspects of hepatocellular carcinoma.

Comparison with other methods

Several in vitro liver models have been used over the last two decades including perfused whole organs, wedge biopsies, liver slices, microsomes, cell lines, and primary hepatocytes (either in suspension or in adherent culture)11,34–36. Although whole livers, biopsies and slices retain in vivo cytoarchitecture and liver-specific hepatocyte-stromal interactions, they have limited viability (usually <48 hours, although some reports demonstrate limited hepatic functions for up to 10 days37), require complex logistics to work with successfully, and do not allow medium- to high-throughput screening (HTS) due to donor organ shortages. Microsomes are used in HTS to identify enzymes involved in drug metabolism but lack the gene expression and cellular machinery required for investigating complex cellular responses. There have been some advances in culture of liver slices in microfluidic devices to prolong their lifetime38; even this short-term extension of viability (<72 hours) still precludes the possibility of chronic drug dosing over several weeks. Furthermore, each experiment using slices by necessity is from a different liver donor, which can make data difficult to interpret across experiments due to donor-to-donor variability in responses. Slices also do not allow investigators to create culture platforms on-demand from the “bottom-up” using cryopreserved cells from the same donor, customized for specific applications and at the level of throughput required. Although hepatocarcinoma-derived cell lines and immortalized hepatocytes provide inexpensive and plentiful cell sources for experimentation, they are known to display abnormal liver-specific functions such as uncontrolled proliferation, dysregulated gene expression, altered host responses to infection, inadequate drug metabolism capacity, dysfunctional mitochondria, and abnormal endocytic functions39,40. The HepaRG carcinoma-derived cell line differentiates spontaneously into hepatocyte-like and cholangiocyte-like cells in vitro and displays higher liver functions relative to HepG2 and other cell lines41. The utility of HepaRG in assessing drug-mediated CYP450 enzyme induction, drug-transporter interactions, and drug clearance as a complementary tool to primary human hepatocytes has been well documented39,42–45. However, the sensitivity for detecting toxicity of drugs was significantly lower in HepaRG than primary human hepatocytes (16% vs. 44%)39. Furthermore, as with all cell lines, HepaRG provide information on drug behavior in a single liver donor, thereby necessitating the use of primary human hepatocytes to obtain data in multiple donors in a more physiological (i.e. non cancerous) context.

While the advent of induced pluripotency has opened the door to the generation of hepatocyte-like cells from numerous genetic backgrounds, such cells do not yet exhibit a fully mature adult phenotype46. Nonetheless, similar to their primary human hepatocyte counterparts, micropatterning strategies can be used to further mature stem cell-derived human hepatocyte-like cells. Notably, Berger et al. have recently shown that, when combined with a Matrigel™ overlay (i.e. ECM sandwich), the MPCC platform can further mature iPSC-derived human hepatocyte-like cells (iHLCs) towards adult primary human hepatocytes and maintain functions for at least 4 weeks in vitro relative to conventional pure iHLC monolayers47. These so-called ‘iMPCCs’ produced high levels of albumin and urea, displayed high activities of major CYP450 and Phase II drug metabolism enzymes, and were sensitive to effects of drugs (induction, toxicity) with in vivo-relevant trends. Moreover, the capacity for the MPCC assay to populated with iPS-derived cells offers the potential to model rare genotypes, as well as access to an expandable cell population, although – despite improvements in hepatocyte-derivation protocols – iPS-derived hepatocyte-like cells remain an imperfect proxy for adult cells46,48, and often require significant culture expertise.

Of the aforementioned cell sources, dispersed primary hepatocytes are considered the “gold standard” for creating liver models because they are relatively simple to use and their cytoarchitecture remains intact; however, these cells require adherence to extracellular matrices (ECM) to survive for longer than the few hours possible with suspension cultures11. Furthermore, in conventional adherent formats that require seeding of primary hepatocytes at very high densities to provide fully confluent monolayers on collagen, hepatic functions rapidly decline over a handful of days, which makes these cultures only suitable for short-term (<48 hours) culture and investigations12,35,49. Longer studies require the supplementation of culture medium with soluble factors that prolong culture survival but can influence hepatocyte differentiation, and/or the use of ECM sandwich or 3D culture that maintain hepatocyte morphology and function to a greater extent than simple monolayer cultures on collagen12,50. In contrast to hepatocytes in monolayer configuration, hepatocytes in sandwich cultures re-establish polarity, express functional transporters in culture, and constitute a useful tool to predict hepatobiliary transport in vivo12,50,51. However, historically, sandwich cultures have been shown to display a sharp decline in liver functions and are only useful for studies that seek to investigate acute phenomena (hours to days)14,49,52. Certainly, for longitudinal studies of hepatotropic pathogens such as HBV, HCV, and Plasmodium, the aforementioned models have not provided significant benefits15,16. Notably, a very recent approach has combined the sandwich culture method with use of Matrigel and HepaRG cells and has been shown to be stable and infectible with P. falciparum, and can maintain P. cynomolgi infection for up to 40 days31. This prolonged culture period opens the door for the system to be suitable for P. vivax studies, and offers a complementary platform for experiments aimed at achieving reactivation of hypnozoites. Nonetheless, given the abnormal cancerous nature of the HepaRG cells, it may well be that the cultures established via this method achieve a random co-culture of primary human hepatocytes and the cholangiocytes, which while undoubtedly useful for certain malaria infection applications, is likely to suffer from batch-to-batch and experiment to experiment variability as we have previously observed with HCV studies in randomly-distributed co-cultures15. Next generation culture models apply engineering methods to impart nonstandard modifications into culture systems11,52,53. MPCC is one such model that maintains high and stable hepatic functions, as well as polarity, for weeks in culture.

To date, the in vitro study of hepatotropic pathogens most commonly employs cell lines. The HCV community has typically relied on the Huh-7 and Huh-7.5 hepatoma cell lines, along with other subclones, to study infection. HBV work has relied upon the HepG2 hepatoblastoma cell line and variants containing integrated viral sequences, and DMSO-differentiated cultures of the HCC line, HepaRG54. These lines may exhibit numerous morphologic and functional abnormalities, meaning that findings obtained using these models, especially those relating to host-virus interactions55, often deviate from those observed in vivo. We have also shown that other classic primary human hepatocyte culture models – such as hepatocytes on rigid collagen, collagen gel sandwich, Matrigel spheroids, and even randomly distributed co-cultures of the same two cell types used in MPCCs – do not sustain HBV or HCV infection as robustly as MPCCs15,28. Other groups have developed primary human hepatocyte models that permit HBV infection56 and, more recently, HCV infection57–59. Nonetheless, while they do offer initial exciting results, it remains to be determined whether these models offer the stability in hepatic phenotype, reproducibility, and robustness that is routinely observed with MPCCs.

As is the case with HBV and HCV, our current understanding of the liver stages of P. falciparum and P. vivax, the major species of human malaria parasites, is also based in large part on the infection of human hepatoma cell lines60–64. In addition to the drawbacks of cell lines discussed above, the observation of parasite or virus development in liver cell lines is challenging after 6 days in culture, as the infected cells continue to proliferate65. There are examples of cultured primary human hepatocytes that can support the development of the liver forms of P. falciparum and P. vivax66–70. However, the use of primary hepatocyte systems in the liver-stage malaria field has been minimal, likely in part due to the difficulty in translating these cells into reproducible formats for screening, limited cell availability, as well as challenges in maintaining phenotypic function over extended periods in vitro13.

Experimental design

MPCC infection experiments consist of three main phases – building the model, characterization of the components, and using MPCCs to interrogate infection (Figure 1).

Since primary hepatocytes need adsorbed ECM (i.e. collagen) to adhere to culture surfaces, the first protocol step details the precise culture specifications to achieve seeding of the cultures. MPCCs have been adapted successfully to both industry-standard 24- and 96-well plate formats, to suit varying experimental requirements; 96-well layouts are typically used when greater throughput is sought, such as screening drug candidates, or when some aspect of the infection protocol is limiting (e.g. novel drugs, pathogen). The other primary specification to consider is the selection of MPCC island diameter and spacing; these parameters can influence essential experimental criteria, such as hepatocyte function, infection efficiency, and the total number of target cells available for infection. In addition, we have recently found that the density of hepatocyte islands can also influence infection dynamics27.

Once these culture specifications are determined, a mold using elastomeric polymers (usually polydimethylsiloxane, or ‘PDMS’) can be made using standard photo- and soft-lithographic techniques71. The mold then serves as the reusable instrument with which to micropattern collagen simultaneously into each well of multi-well plates. Briefly, well plates are coated with collagen; a PDMS mold is then placed on the well plate to serve as a mask that will protect collagen-coated islands to which hepatocytes will selectively attach. At this point, oxygen plasma gas is used to eliminate collagen-coated surfaces that are not protected by the mask, leaving only the array of evenly spaced, equally-sized collagen islands. The micropatterned plates can immediately be used for cell seeding or refrigerated for a few months in a desiccator without noticeable loss of cell attachment capacity. Each well of the plate is seeded with primary human hepatocytes (from fresh or cryopreserved sources) and shaken 3-4 times per hour to ensure uniform seeding of hepatocytes onto all ECM islands in the well. Once the islands are greater than 85% filled with hepatocytes over 3-5 hours, the cells which have not adhered are removed by washing the wells with culture medium to prevent non-specific attachment of hepatocytes to bare plastic areas due to adsorption of serum proteins from culture medium. Adhered hepatocytes are then allowed 18-24 hours to fully spread onto the islands to make fully confluent clusters. Stromal cells (i.e. murine J2-3T3 fibroblasts) are seeded onto the hepatocyte cultures the following day, and are left to attach onto the remaining spaces not occupied by the hepatocytes. If desired for the particular application, additional cell types can be seeded at this second stage intermixed with the J2-3T3 fibroblasts. For example, Kupffer macrophages have been selected as an immune environment-modifying population (manuscript in preparation); however, by themselves, these macrophages (and other liver-derived stromal cell types) do not stabilize hepatic functions, thereby necessitating the continued use of the J2-3T3 cells. The controlled nature of the cultures achieves reproducibility between batches, especially with use of pre-qualified cryopreserved human hepatocyte lots, and allows for the testing of hypotheses related to the impact of specific cell types.

Biomarkers for characterizing an MPCC can be used to optimize selection of a candidate hepatocyte cell source (i.e. specific donors), confirm that cultures are highly functional while maintaining longevity of functions for the time-period required, and subsequently assess the impact of pathogen infection and/or therapeutic intervention. Secretion of hepatocyte biosynthetic products (albumin, urea), CYP450 activity, and morphology (including appropriate polarization with appearance of bile canaliculi) are standard biomarkers used at various time points during the culture lifespan. Typically, we screen several human hepatocyte donors/lots in parallel using the aforementioned biomarkers to select those donors which display stable phenotypic functions for several weeks in MPCCs. Cryopreserved hepatocyte lots sold under the label of “plateable” by various vendors (i.e. BioreclamationIVT, Life Technologies, Triangle Research Labs) typically attach to collagen islands in MPCCs and display stable phenotype for 4-6 weeks in vitro. Hepatocytes from younger donors (<10 years of age) have been found to function for 6 weeks and longer in limited instances14.

MPCCs that successfully maintain longevity can then be used for infection experiments. Such experiments can be tweaked as per the needs of the researcher. The typical approach is to infect with the pathogen of interest and then use assays specific to that pathogen. Below, we will discuss details of this process for HCV, HBV, and Plasmodium infection. Assays can be used to monitor infection, for example in the context of drug screening or other perturbations in basic biology studies.

Limitations

Compared to classic seeding of a cell line on well plates, establishment of MPCCs is more involved when the process for patterning the plates as well as seeding of multiple cell types are taken into account. However, the ability to store collagen patterned plates for several months at 4°C decouples the batch patterning process in multi-well plates from the seeding of the cell types on two separate days. Regardless, the added effort to create MPCCs affords the researcher the ability to evaluate chronic aspects of liver diseases and drug dosing regimens on stable primary hepatocytes, which otherwise may require time consuming and far more challenging investigations in vivo.

Depending on the context of the desired experiment, the current MPCC format can present a problem in that it requires use of mouse fibroblasts as the supportive cell type. For instance, mouse fibroblasts may represent a confounding detail in certain immunologic studies that require cells with an exclusively human background. Additionally, any time a non-hepatocyte-specific biomarker is assessed in MPCCs, fibroblast only controls typically need to be carried out to ascertain hepatocyte-specific responses. However, since the MPCCs are a 2D monolayer of cells, high content imaging has been successfully employed to determine effects of perturbations on hepatocytes and fibroblasts, allowing assessment of both hepatocyte-specific and non-hepatocyte-specific effects, in the same well, a key advantage of MPCCs25,48. Ultimately, it would be ideal to replace the fibroblasts altogether with their molecules that stabilize the hepatic phenotype. While efforts are being made for such fibroblast replacement using defined microenvironment cues like small molecules, proteoglycans, cadherins and biomaterials, the complete temporal and spatial combinatorial sequence of fibroblast-derived molecules has not yet been determined18,48,72,73.

MPCCs are also currently limited by their finite lifespan, although these cultures do persist far longer than other hepatocyte systems (i.e. hours to days vs. 4-6 weeks). As such, infection experiments cannot be monitored over the course of many months (e.g. in the study of fibrosis related to HCV or HBV infection, or for the purposes of assaying for hypnozoite reactivation in long latency P.vivax strains). Currently, MPCCs are better suited for the study of initial infection and acute disease progression, whereas it is challenging to apply this model for the study of true “chronic” HCV or HBV infection. While we do see a decline in viral protein production coupled to maintenance of cccDNA level at time points after 2 weeks post HBV infection28, which may be indicative of a switch from an acute to a chronic phase of infection, there are other explanations for this phenomenon – such as innate immune stimulation limiting host and viral translation. Overall, the inability to maintain MPCC function indefinitely is likely due to some component of in vivo physiology (e.g. certain non-parenchymal cell types) and/or aspects of three-dimensional architecture that are missing in vitro. Related to this limitation is the finding that, as in other in vitro systems used in the community, infection is not as robust in MPCCs as it is in vivo. Recent preliminary data suggests that innate immune signaling is relatively more active in the in vitro cultures than has been predicted in vivo, and may contribute to the dampened HCV infection efficiency observed in this platform (data not shown). Nonetheless, since MPCCs are built “bottom-up” from individual components, they can be used as a base platform on which to engineer additional liver-specific microenvironmental cues in order to better mimic liver physiology and disease states36.

Regarding Plasmodium parasite growth, the sizes reported in our system are similar to what have been previously observed in other in vitro systems at day 532,66,74, but smaller than those observed observed in vivo at day 575,76 or in humanized mouse models77. It is possible that conformational cues may be important for parasite growth (e.g., two-dimensional versus three-dimensional contexts), or that EEF size is impacted by hepatocyte packing density. Notably, we recently reported that in vitro parasite growth can be increased in MPCCs by modulating the cell surface oxygen tension experienced by the hepatocytes27.

MATERIALS

REAGENTS

Culturing fibroblasts

J2-3T3 fibroblasts (courtesy of Howard Green, Harvard Medical)78

High glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM with L-glutamine) (CORNING, Cellgro, cat.no. 10-017-CV)

BS (Bovine serum) (Life Technologies, Gibco, cat.no. 16170-078)

Penicillin-streptomycin (CORNING, Cellgro, cat.no.300-002-Cl)

Trypsin-EDTA, 0.05-0.25% (wt/vol) (CORNING, Cellgro, cat.no. 25-053-Cl)

Fibroblast medium: DMEM, 10% BS, 1% P/S

Seeding and culturing human primary hepatocytes in MPCC

Cryopreserved Primary Human Hepatocytes (BioreclamationIVT, Lot NON; Invitrogen, Lot Hu4151 and Lot Hu8085)

ITS+ (Insulin/human transferrin/selenous acid and linoleic acid) premix (BD Biosciences, cat. no. 354352)

Dexamethasone (Sigma, cat.no. D8893)

Absolute ethanol (Sigma, cat.no. E7023)

DMEM with L-glutamine (CORNING, Cellgro, cat.no. 10-017-CV)

FBS (Fetal Bovine Serum)(Gibco, cat.no. 1600-044)

HEPES, 1M, pH7.6 (Gibco, cat.no. 15630-080)

Penicillin-streptomycin (CORNING, Cellgro, cat.no.300-002-Cl)

Glucagon:(Sigma, cat.no. G2044)

Trypan blue (Sigma, cat.no. T8154)

Pathogen sources

Both fresh and cryopreserved P. falciparum and P.vivax sporozoites were provided by Sanaria (Maryland, USA)

De-identified HBV+ human plasma (tested negative for HIV, HCV) was obtained from the Red Cross

HCV stocks for infection were generated by electroporation of HCV RNA into Huh7.5.1 cells, followed by harvesting, purification and concentration of secreted infectious virions

Making MPCC masters

CAD files for Teflon mold

PDMS (Sylgard 184 kit, Dow Corning)

Arch punch (13 mm for 24 well plate, 5 mm for 96 well plate; McMaster Carr)

Silicon master; micro-domain of 500 μm diameter islands. 1200 μm center-to-center island spacing in a 24 well format or 900 μm spacing in a 96 well format.

Trichloro(1H,1H,2H,2H-perfluorooctyl)silane (Sigma, cat.no. 448931)

Glass petri dish (150 mm diameter; Fisher, cat.no. S00056)

Plastic Petri dishes (150 mm diameter; Sigma, cat.no CLS430597)

Hexane, mixture of isomers (Sigma, cat.no 650544)

Preparing micropatterned co-cultured plates

96 or 24 tissue culture plates. (For high magnification fluorescence microscopy use glass bottom plates.)

96 well Glass bottom plates (Greiner Bio-One, cat.no. 655892)

24 well Glass bottom plates (Greiner Bio-One, cat.no. 662892).

Coverslips, 12mm circle (VWR, cat.no. 48366-251)

PDMS (Sylgard 184 kit, Dow Corning) master. Micro-domain of 500 μm diameter islands. 1200 μm center-to-center island spacing in a 24 well format or 900 μm spacing in a 96 well format. Production is described in the protocols.

Rat tail collagen solution type I (BD Biosciences, cat.no. 354236)

Sterile deionized H2O (ddH2O)

Functional characterization of hepatocytes

Human Albumin ELISA Quantitation Set (Bethyl, cat.no. E80-129)

Urea Nitrogen BUN Test (Stanbio, cat.no. 0580-250)

CYP3A4 Activity Assay (Promega, cat.no. V9002)

Bile canaliculi live stain (Life Technologies, cat.no. C1165)

Immunofluorescence staining of malaria-infected MPCCs

Primary Antibodies: a) For P.falciparum: anti-PfHSP70 clone 4C9 and anti-PMSP1 b) for P.vivax: antiPvCSP (247 or 2A10).

Secondary antibodies: Alexa Fluor 594 donkey anti mouse IgG (Invitrogen, cat.no. A21203) or Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti mouse IgG (Invitrogen, cat no. A11029)

Methanol (MeOH) (Sigma, cat.no. 179337)

Paraformaldehyde (PFA) (Electron microscopy Sciences, cat.no. 15714)

Hoescht 33342 (Life Technologies, cat.no. H3570)

Aqua Mount Fluorescent mounting medium (Lerner Laboratories, cat.no. 13800)

Fluoromount G (Southern Biotech, cat.no.17984-25)

Dulbecco’s PBS with CaCl2 and MgCl2 (Life Technologies, cat.no. 14040)

Bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma-Aldrich, cat.no. A7906)

HCV infection analysis

-

HCV RNA quantification

-

○

Eragen MultiCode RTx HCV kit (Luminex Corp., Madison, WI)

-

○

-

HCV luciferase reporter assay

-

○

Promega Luciferase Assay system (Promega, cat.no. E1501)

-

○

96-well white assay plates (e.g. Corning, cat.no. 3600)

-

○

-

HCV NS5A staining

-

○

Poly-L-lysine (Sigma, cat.no. P8920)

-

○

96 well tissue-culture treated plates (e.g. Corning)

-

○

HCV NS5A Antibody 9E1079

-

○

Goat-anti-mouse HRP secondary antibody (ImmPress kit, Vector Labs)

-

○

DAB+ substrate (Dako)

-

○

HCV stock generation

Huh-7.5 or Huh-7.5.1 cells

HCV RNA for electroporation

2 mm gap cuvettes

100K MWCO Millipore Amicon ultracentifugal filters (Millipore, cat.no. EW-29968-28)

Cryovials (e.g. Corning)

HBV stock preparation

HBV-positive patient plasma (tested HIV-, HCV-) from Red Cross

1.25M CaCl2 solution

Sterile 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes

IPS-1 reporter lentivirus preparation and transduction

pTRIP-RFP-NLS-IPS reporter plasmid DNA80

VSV-G and HIV gag-pol plasmid DNA80

HEK 293T cells (e.g. ATCC)

Poly-L-lysine (Sigma, cat.no. P8920)

Tissue culture-treated well plates or flasks

Transfection reagent (XtremeGene9, Lipofectamine, etc.)

HEPES (Life Tech., cat.no. 15630-80)

Polybrene (Sigma, cat.no. 107689)

Drug controls

Dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma, cat.no. D8418)

2′-C-Methyladenosine (Santa Cruz, cat.no. 15397-12-3)

HBV infection analysis

-

HBsAg ELISA

-

○

GS HBsAg EIA 3.0 kit (Bio-Rad, cat.no. 32591)

-

○

-

HBeAg ELISA

-

○

HBeAg and HBeAg Ab ELISA kit (AbNova, cat.no. KA0290)

-

○

3,3′,5,5′- tetramethyl-benzidine substrate (Pierce, cat.no. 34029)

-

○

-

HBV 3.5kb RNA and total RNA quantification

-

○

Qiagen RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen, cat.no. 74134)

-

○

Qiagen, RNase-free DNase kit (Qiagen, cat.no. 79254)

-

○

SuperScript III First-strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen, cat.no. 18080)

-

○

Primers (detailed in methods)

-

○

SYBR Premix Ex Taq kit (TaKaRa, cat.no. RR820)

-

○

-

HBV DNA/cccDNA quantification

-

○

QIAamp DNA blood mini kit (Qiagen, cat.no. 51104)

-

○

QIAamp Minelute Virus spin kit (Qiagen, cat.no. 57704)

-

○

TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, cat.no. 4391128)

-

○

Primers (detailed in methods)

-

○

2× HBV plasmid (known quantities for standard curve)

-

○

-

Southern blotting for HBV DNA forms

-

○

Qiagen Proteinase K (Qiagen, cat.no. 19131)

-

○

LE-Agarose (Ambion, cat.no. AM9040)

-

○

TAE buffer (e.g. Thermo, cat.no. B49)

-

○

Hybond-N+ (GE Healthcare Life Science, cat.no. RPN119B)

-

○

Prime-It II Random Primer Labeling Kit (Agilent, cat.no. 300385)

-

○

-

Immunofluorescent staining of HBV core protein

-

○

32% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences, cat.no. 15714)

-

○

Senso-Plate Glass-bottom tissue culture plates (Greiner bio-one, cat.no. 662892)

-

○

Triton-X 100 (Sigma, cat.no. X100)

-

○

Rabbit polyclonal anti-HBV core antibody (Dako, cat.no. B0586)

-

○

Donkey anti-rabbit DyLight 594/Alexa 594 conjugate (Jackson Immunoresearch, cat.no. 712-585-153)

-

○

Hoechst 33342 dye (Thermo, cat.no. 66249)

-

○

EQUIPMENT

Culturing fibroblasts

Tissue culture flask

Tissue culture centrifuge

Microscope

Fibroblast medium

Seeding and culturing human primary hepatocytes

Collagen micropatterned plates

Tissue culture centrifuge

Preparing micropatterned co-cultures plates

PDMS masks

Collagen type I

Plasma chamber (e.g. SPI Plasma Prep III, Plasma-Etch PE-50 or PE-75)

Tissue culture (TC) hood with UV light

HCV stock generation

Electroporator

Ultracentrifuge for virus concentration

HBV stock preparation

Benchtop centrifuge

HCV infection analysis

Luminometer (machine capable of reading Gaussia luciferase luminescence)

Light microscope (for HRP+ quantification of NS5A staining)

HBV infection analysis

Luminometer

Plate reader

ABI 7500 or Light Cycler 480 (for RT-PCR)

Gel box

Phosphorimager

Epifluorescent microscope

REAGENT SETUP

Hepatocyte medium preparation

Prepare ITS stock as follows: 20ml ITS+ + 30ml HEPES 1M + 20ml Penicillin-streptomycin. ITS stock should be used within 3 weeks when it is stored at 4°C.

Prepare dexamethasone stock at 20 μg/ml as follows: Add 1 ml absolute ethanol to 1 mg dexamethasone, gently swirl to dissolve, add 49 ml sterile DMEM medium. Aliquots can be stored at −20°C.

Prepare glucagon stock at 0.1mg/ml. Aliquots can be stored at −80C.

Prepare 200 mL of hepatocyte medium by combining and subsequently sterile filtering the following quantities: 7.2 mL ITS stock, 172.8 mL DMEM, 20 mL FBS, 400 μL dexamethasone, 14 μL glucagon stock.

Hepatocyte full medium should be used within 2 weeks when it is stored at 4°C. Do not warm and rewarm the entire volume of medium for use; remove aliquots as needed for the experiment.

Sporozoites

Mosquitoes were fed on P.falciparum- and P.vivax-infected blood using membrane feeding. For P.vivax Chesson strain, mosquitoes were fed directly on infected monkeys81,60,61.

Sporozoites were extracted from infected mosquitoes by dissection of their salivary glands and passing the glands back and forth though a 26G needle fitted to a 1 ml syringe.

Further purification and cryopreservation are optional.

PROCEDURE

Steps 1-14: Preparing PDMS etch mask. ● TIMING 3-5 days (only needs to be completed once)

Machine Teflon pieces that contain base and pillars for 24- or 96-well plate formats.

Screw two Teflon layers together tightly to prevent leakage of PDMS between Teflon layers.

Mix PDMS base and curing agent at 10:1 ratio, and place in vacuum desiccator under vacuum to degas the PDMS mixture.

Pour degassed PDMS into Teflon molds, making sure to fill in entirety the “pillars” that extend into the well plates, and maintaining a flat rectangular base of PDMS on top of pillars (this section needs to be at least ~2 mm thick to ensure flatness along the PDMS).

Cure the PDMS base piece in Teflon mold in oven overnight at 65°C.

Carefully pull PDMS off the Teflon piece after casting, being sure to peel slowly to avoid tearing the PDMS. If large defects arise during this process, the PDMS should be recast and cured.

Design and produce high-resolution transparencies containing the island patterns for MPCCs. Standard island sizes are circles with 500 μm diameter, with 900-1200 μm center-to-center spacing between islands.

Order patterned silicon masters using standard foundry services (e.g. Trianja technologies, SimTech, FlowJem), ensuring that island regions are recessed in the master with a feature height of 150-250 μm.

Upon receiving the silicon master, glue wafer into a glass Petri dish of appropriate size by smearing a few drops of PDMS (again 10:1 base to curing agent) onto Petri dish and pressing wafer onto these drops. Ensure a tight seal such that the wafer remains flat on the Petri dish surface (i.e. by using a weight), and cure overnight at 65°C.

Silanize master by dropping a few drops of trichloro(1H,1H,2H,2H-perfluorooctyl)silane (Sigma-Aldrich, cat.no. 448931) into a plastic weighing dish and suspending the master upside down, directly above this weighing dish in a vacuum desiccator for 2 hours. Replace the trichloro(1H,1H,2H,2H-perfluorooctyl)silane and repeat the 2 hour treatment.

Slowly pour degassed PDMS mixture (10:1 base to curing agent) over the silicon master until a uniform layer of PDMS coats the glass dish into which the master is glued. Degas PDMS in vacuum desiccator again after it is poured, and note the exact volume of PDMS used to fill the dish so that future casts are performed with the same volume. After degassing mixture, cure PDMS overnight at 65°C.

Carefully cut the cured PDMS from the outside edge of the glass dish using a scalpel. Then, peel cured PDMS layer off the silicon master by gently loosening the PDMS from the outside edge of the glass dish and then slowly peeling the entire PDMS layer off. Be careful not to bend PDMS too far, or else PDMS may tear. The PDMS layer that was on top of the silicon master now has the negative replica of the features present on the master.

Use metal punches (McMaster Carr) to core out individual “buttons” (for each well of the multi-well plate) from the PDMS with the relevant features. In particular, use 14 mm punch for 24 well plate and 6 mm punch for 96 well plate formats.

Attach the PDMS buttons to the large PDMS base layer (cast on the Teflon mods) to create the final two-part PDMS etch mask. First, mix a 10:1 ratio of PDMS base to curing agent, and adding 1:1 v/v hexanes to this mixture to create ‘PDMS glue.’ Then, flip PDMS base layer such that the pillars for each well are facing up, cover each pillar surface with PDMS glue using a spatula or brush, and firmly place one cored-out PDMS buttons containing raised islands onto each pillar. Ensure that each button is firmly attached to the pillar below, and then cure the entire assembly overnight at 65°C to complete fabrication of the PDMS etch mask. Placing a weight (i.e. glass with metal weight) on the entire assembly will ensure that all the buttons glued onto the base structure are at the same height and leveled.

Steps 15-24: Preparing micropatterning plates. ● TIMING 2h

15. Prepare 25-50 μg/mL collagen solution. Dilute stock collagen with ddH2O. PBS can be used; however, since it leaves a salt residue in each well, numbers of washings (iv) below need to be increased to 5X to remove the salt that can affect patterning.

16. Fill each well of 24-or 96-well plate with 250-400 μL or 50-100 μL, respectively, collagen solution.

17. Incubate for 60-120 min at room temperature or 30-60 minutes at 37°C.

18. Rinse 3 times with ddH2O.

19. Dry plates thoroughly – bang plates onto paper towels and let them dry in back of culture hoods near the air vent for at least 2 hours, though overnight drying is also acceptable. ■ PAUSE POINT the plates can be stored for up to 3 months sealed in a plastic bag with desiccant pack at 4°C.

20. Clamp etch mask to plate. Tighten such that the pattern is evenly visible on the bottom of the plate. Do not over-tighten; columns may bend, exposing those regions that are to be shielded from plasma ablation. ▲ CRITICAL STEP

21. Insert into plasma chamber and close it.

22. Expose to 50-100W oxygen plasma for 30-120 seconds (this may need to be optimized to obtain optimal protein patterning depending on the plasma system used).

23. Release vacuum, open the plasma chamber and remove the device. Unclamp the mask from plate.

24. Sterilize the plate in a TC hood under UV light for 15 minutes. If UV light is used, it is important to use an appropriate meter to ensure that the UV intensity in the bulb of the TC hood has not diminished significantly. If UV is not available, wells can be incubated with 70% ethanol in ddH20 (300 μL per well) for 20 minutes followed by 3X rinses with sterile ddH20. ■ PAUSE POINT the plates can be stored for up to 3 months sealed in a plastic bag with desiccant pack at 4°C.

Steps 25-35: Handling of primary human hepatocytes

If cryopreserved hepatocytes are used, follow option A; if fresh hepatocytes cells provided suspended in preservation buffer are used, follow option B.

(A) Thawing cryopreserved primary human hepatocytes ● TIMING 30m

25. If a cryopreserved vial is taken out of a liquid nitrogen dewar, loosen the cap very slightly (half a turn on a thread should be sufficient) to let any nitrogen gas out in order to prevent the vial from bursting open upon thawing in the next step. Then, tighten the cap prior to thawing.

26. Thaw the vial in the water bath at 37°C. Typically 2 minutes are sufficient to thaw the vial such that a small ice crystal is still visible. However, the thawing time should be optimized depending on the volume in the vial and vendor instructions.

27. Spray the vial with 70% ethanol and wipe clean quickly to ensure that the potentially contaminated water from the water bath is removed prior to step (v).

28. While the vial is still tightly closed, invert a few times in the TC hood to mix the contents as hepatocytes often settle to the bottom of the vial.

29. Uncap the vial in the TC hood and immediately add the contents of the vial on top of 40 mL of pre-warmed (in 37°C water bath for 15-30 minutes) culture medium (DMEM with 1% P/S without serum) in a 50 mL conical. It is important not to use serum in the medium in order to achieve specific patterning on collagen islands in subsequent steps without non-specific attachment to the plastic regions due to adsorption of serum proteins. It is also important to execute steps (iii) to (v) as quickly as possible (<1 min) to avoid injury to hepatocytes due to higher temperatures and presence of concentrated cryoprotectant in the vial. Thus, thawing no more than 1-2 vials at once is recommended. ▲ CRITICAL STEP

30. Spin down cells at 100×g for 6 minutes. Given differences in centrifuge models and radii of the rotors, conversion of RPM to the g force given is recommended.

31. Carefully remove the supernatant with an aspirator ensuring not to disturb the hepatocyte pellet. It is acceptable to leave ~0.25-0.5 mL of medium in the conical if the hepatocyte pellet begins to move.

32. Resuspend cells in DMEM with 1% P/S (without serum).

33. Count cells. The trypan blue exclusion method and manual counting using a hand tally counter works well. Hepatocytes are much larger than non-parenchymal cells and red blood cells that may be present in very small quantities. Thus, it is relatively straight-forward to tell a hepatocyte apart under the microscope.

(B) Fresh isolated primary human hepatocytes

34. Execute steps 30 through 32 to remove the preservation buffer fresh cells are typically suspended in and wash with warm culture medium.

35. Execute steps 30 through 33 to obtain cell suspension for seeding.

Steps 36-39: Seeding cells in ECM micropatterned plates

36. Plate cells in each well. For a 24 well plate, seed 250,000 hepatocytes in a final volume of 300ul per well; for a 96 well plate, seed 70,000 hepatocytes in a final volume of 70 μl per well. These seeding densities can be optimized depending on attachment efficiency of the hepatocyte lot. We have used as low as 150,000 hepatocytes and 30,000 hepatocytes in 24- and 96-well formats, respectively.

37. Put the cultures in the incubator. Then, 3-4 times each hour, take the plate out of the incubator and shake 3X by hand twice in both horizontal and vertical perpendicular planar axes (not circular) to homogenize the cells in each well since hepatocytes settle to the edges of the wells given their size distribution. The plate should be out of the incubator no more than 30 seconds each time and ensure that shaking is not done so vigorously so as to splash the cell suspension out of the well and into the space between wells. The cells start seeding onto the islands in 15-20 minutes and such is visible from the bottom of the plate macroscopically under appropriate lighting. ▲ CRITICAL STEP

38. Every 2 hours post seeding, inspect island-filling density under the microscope. When 85-90% of the islands are covered with hepatocytes, proceed to the next step. ● TIMING 2-4h, depending on the hepatocyte lot chosen. ? TROUBLESHOOTING.

39. Rinse unattached cells away by gentle aspiration from each well. Next, rinse 2-3 times with culture medium (DMEM with 1% P/S without serum) in immediate succession until a clear pattern is observed and minimal cells are observed under the microscope between the hepatocytes islands. Approximately 1-5% of the cells will likely still be in suspension in each well even after the washings. These cells typically do not attach well onto the plastic and are washed away the next day upon fibroblast seeding.

Steps 40-45: Hepatocyte selection/evaluation (functional assays and infectibility) [Figure 3]

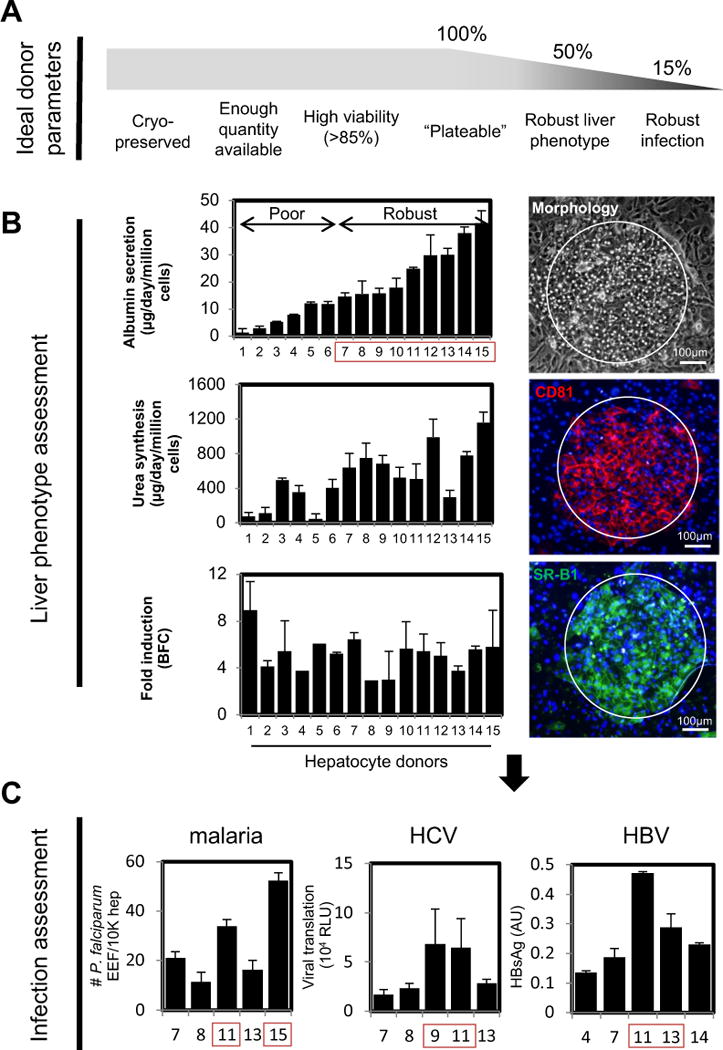

Figure 3. Selecting cryopreserved primary human hepatocyte sources for hepatotropic pathogen infection.

(A) Schematic of sequential criteria filters used to select optimal human cryopreserved hepatocyte donors (lots) for infection with hepatotropic pathogens. (B) Functional characterization of plateable hepatocyte lots to assess their liver phenotype. Left, plots of albumin production, urea synthesis, and cytochrome P450 activity (top to bottom). Right, representative images of optimal donor lots depicting hepatocyte morphology, CD81 expression, and SR-BI expression (top to bottom); CD81 and SR-BI are entry receptors for malaria and HCV. (C) Assessment of hepatocytes with robust liver phenotype for permissiveness to infection by malaria using fresh sporozoites and assessing infection at day 3 post-infection (left), HCV (middle), and HBV (right).

40. Request vials of cryopreserved primary human hepatocytes of different donors from vendors permitted to sell products derived from human organs procured in the United States by federally designated Organ Procurement Organizations. Hepatocyte vendors include Life Technologies, Lonza, BioreclamationIVT, Corning Life Sciences, and Triangle Research Labs.

41. Seed cryopreserved hepatocytes as detailed in steps 25-35 and 36-39. 24 h after seeding hepatocytes, seed J2-3T3 murine embryonic fibroblasts (40,000 total cells in 300-400μL volume per well of a 24-well plate and 7,000 total cells in 50-70μL per well of a 96 well plate) in hepatocyte culture medium.

42. Collect supernatant from MPCCs and store at −20°C or −80°C until further use. Add fresh hepatocyte medium to MPCCs every 24-48 h.

43. As a first step to ensure suitability of candidate hepatocytes for use in long-term infection experiments (e.g. HCV persistence and Plasmodium vivax hypnozoite biology), keep MPCC cultures for at least 3 weeks. During this period, perform microscopic observations every 2-4 days to monitor maintenance of morphological traits associated with differentiated primary adult human hepatocytes, such as a polygonal shape, distinct nuclei and nucleoli, presence of bile canaliculi (bright borders between cells with rough edges) and absence of dark granularity in the hepatocyte cytoplasm. While these features are qualitative and take some practice to detect, hepatocytes have a very distinct prototypical morphology that is clearly distinguishable from the surrounding fibroblasts and when compared to spread out de-differentiated hepatocytes cultured for a few days in the absence of stromal support cells.

44. During the three-week test period, assay collected MPCCs supernatant for levels of human albumin and urea secretion. Ideally, a hepatocyte lot that is eventually used for either malaria or HCV infection will exhibit stable (within 25%) albumin secretion and urea production for at least 3 weeks in culture in order to enable chronic infection and drug dosing studies (specific kits that can be used for this purpose were mentioned in the reagents above). The levels of these markers can vary across human hepatocyte donors. Typical ranges are provided in our publications13,15.

45. Functional maintenance of a particular lot of hepatocytes is necessary but not sufficient to ensure infectibility by either malaria parasites or HCV. As such, it is recommended that hepatocyte lots that pass the functional screening described above be further assayed for their capacity to support infection by either pathogen (see steps 6A and 6B). Typically, 5-10 hepatocyte lots/donors are screened for each application to bank 1-3 “qualified” lots for continued and on-demand use in infection studies.

Steps 46-82: Infection of MPCC with hepatotropic pathogens [Figure 3]

Infection conditions have been optimized for each pathogen. If MPCC are infected with Plasmodium sporozoites, follow choice (A), and if infected with Hepatitis C virus (HCV), or Hepatatis B (HBV), follow choices (B) or (C), respectively.

(Choice A; steps 46-51) Infecting MPCC with Plasmodium sporozoites. [Figure 4]

Figure 4. Application of MPCC for in vitro infection by Plasmodium parasites.

(A) Malaria life cycle schematic depicting the obligate, initial liver-stage expansion prior to egress to the blood. (B) Left, Representative images of P. falciparum (top) and P. vivax (bottom) in human MPCCs. The scale, antibody used for immunohistochemistry (blue, DAPI), and day of infection is indicated on each image. Middle, Size distribution of P. falciparum (top) and P. vivax (bottom) parasites in MPCCs over time. Right, Representative images of P. falciparum (top) and P.vivax (bottom) in human MPCCs stained on the indicated day of culture, and with the indicated fluorescent antigen (blue, DAPI). (C) Merozoites released from P. falciparum infected MPCC infect red blood cells; Geimsa stain reveals ring stage. (D-G) Suitability of MPCCs for drug screening, based on (D) sensitivity to primaquine drug treatment, (E) expression of drug metabolizing genes, (F) capacity to distinguish live versus attentuated sporozoites in a candidate vaccine method, and (G) applicability to image analysis automation for medium throughput screening. March et al. (2013) Cell Host Microbe.

Optimal infection rates are achieved if infections are conducted one day after hepatocyte seeding. However, infections remain possible, albeit diminished, for at least three weeks after establishing MPCCs, offering flexibility with the timing of sporozoite seeding and experimental schedules. ● TIMING 4h

- 46. Prior to step 41 (before J2-3T3 seeding), prepare a suspension of sporozoites at a ratio of 1:5 to 1:10 (attached hepatocytes:infectious sporozoites) using hepatocyte culture medium. The optimal infection volume is 50μl and 375μl per well of a 96- or 24-well plate, respectively. ▲ CRITICAL STEP The number of infective sporozoites is indirectly defined using a sporozoite gliding motility assay. For cryopreserved sporozoites, sporozoite motility depends on the source material and freezing protocol used. Typically, about 30% of cryopreserved sporozoites demonstrate gliding motility after thawing, whereas 80-90% of sporozoites freshly obtained via dissection of mosquito salivary glands demonstrate gliding motility.

Sporozoite source Total spz dose Gliding motility 96 format (hepatocyte/well) Infectious spz based on gliding assay Ratio cryopreserved 150,000 33% 10,000 50,000 1:5 fresh 75,000 85% 10,000 63,000 1:6 47. Remove culture medium and add the suspension of sporozoites to the relevant wells. Shake plates in a perpendicular axis within the same plane, two times in each direction.

48. Centrifuge the plate at 600×g for 5 minutes at room temperature.

49. Incubate the infected plates at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 3 h.

50. After 3 h, wash the wells 3 times with hepatocyte culture medium (50μl and 300μl per well of a 96- or 24-well plate, respectively).

51. As in steps 41-42, seed J2-3T3 murine embryonic fibroblasts in hepatocyte culture medium. Replace medium 24 h after the fibroblast seeding and subsequently daily. ▲ CRITICAL STEP If non-aseptic mosquitoes are used, increase the concentration of penicillin/streptomycin to 3% during and after the 3h infection period. Supplement the hepatocyte medium with Amphotericin B, also called Fungizone (1:1000), only after the 3 h infection period, i.e. with the addition of the J2-3T3 fibroblasts.

(Choice B; steps 52-69) Infecting MPCC with HCV [Figure 5]

Figure 5. Application of MPCC for in vitro infection by HCV.

(A) HCV life cycle. (B) Time course of infection and drug treatment. (C) Live-cell imaging of reporter nuclear translocation upon HCV infection (arrowheads). (D) Multiple antiviral drugs with unique mechanisms of action show dose responsiveness. (E) Antibodies against either HCV entry factors or HCV virions decrease viral infection. Ploss, Khetani, et al. (2010) Nature Biotechnology.

While it is possible to infect cells with HCV before or after J2-3T3 seeding, we typically infect soon after fibroblast seeding. Waiting to infect for too long post fibroblast seeding typically reduces subsequent infection rates. The steps listed below outline the protocol for infecting 48 hours post hepatocyte seeding. Materials in contact with HCV should be decontaminated after use according to the appropriate safety protocols followed in your research environment.

Generation of HCV stocks

Electroporation of HCV RNA ● TIMING Complete in <2h to promote high electroporation efficiency

52. Grow Huh-7.5 or Huh-7.5.1 cells to 80% confluency by plating them 48h prior to electroporation at 5×106 cells per P150. Use cells between passage 25-45 grown in DMEM/10% FBS/0.1mM NEAA.

53. Trypsinize cells, pass through a 100 μm cell strainer and transfer to a 50ml conical tube. Spin, 5min at 514g (1500 rpm) at 4°C.

54. Remove supernatant and resuspend in 10ml ice-cold PBS (w/o Ca2+, Mg2+). Bring volume up to 30ml with PBS and spin, 5min at 514g (1500 rpm) at 4°C. ▲ CRITICAL STEP: Keep bottle of PBS on ice between uses. Do all centrifugation steps at 4°C.

55. Remove supernatant and repeat step 54, reserving an aliquot for cell counting on a hemocytometer or using a Coulter counter. ▲ CRITICAL STEP: Homogenize cells well and use a sufficiently large sample size to achieve an accurate cell count.

56. Remove supernatant and resuspend cell pellet in ice-cold PBS at 1.5×107 cells/ml. Keep cells on ice.

57. Add 400μl cell suspension to a microcentrifuge tube containing HCV RNA (5 μg RNA in 10μl sterile water is recommended). RNA should be stored at −80°C in single-use aliquots prior to use. Pipette up and down 3× and immediate transfer entire volume to 2mm gap cuvette. ▲ CRITICAL STEP: To minimize exposure of RNA to residual RNases in the cell suspension, pulse immediately after RNA addition.

58. Secure capped cuvette in electroporator and pulse. (Settings for the BTX ElectroSquare Porator ECM 830 are: 860V, 5 pulses, 99us, 1.1s interval, high voltage setting. However, settings must be optimized for each electroporator make and model.)

59. Repeat for each electroporation. ▲ CRITICAL STEP: Ensure cell suspension remains homogenous during this process.

60. Set cuvettes aside and let cells rest at room temperature for 10min. ▲ CRITICAL STEP: Plate as quickly as possible (within 30min).

61. Per P150, pool 3 electroporations. Add the electroporations to be pooled using plastic dropper provided with cuvette to transfer cells to 50ml conical tube containing 20ml pre-warmed DMEM/10%FBS/0.1mM NEAA. Invert to mix. Remove entire volume to each P150.

Harvesting viral stock ● TIMING 5 days

62. 24hrs post-electroporation, the cells should be ~50-70% confluent. Remove the medium and add 20ml fresh DMEM/10%FBS/0.1mM NEAA.

63. 48hrs post-electroporation, change medium to 15ml DMEM/0.15%BSA.

64. Collect 4 times per 24hrs (7-8am; noon; 4-5pm; 10-11pm). Store pooled supernatant at 4°C protected from light.

65. At, or just before 120hpe, the cells should begin to look unhealthy and collection should cease.

66. Clarify supernatant by centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 5-10min. Stock can be concentrated using Millipore Amicon 100K MWCO. Spin 2200 rpm until the sample has been concentrated to less than 1ml. Refill tube several times in order to concentrate initial volume 25X. Aliquot into cryovials. Slow freezing by placing at −80°C. (Long-term storage at 4 or 20°C will result in decreased titer). Avoid repeat freeze-thaw. Thaw by placing virus at room temperature or on ice rather than at 37°C.

67. Seed J2-3T3 murine embryonic fibroblasts (40,000 cells per well of a 24-well plate) in fibroblast medium, 24 h after seeding hepatocytes.

68. Inoculate cells with HCV JFH-1-based stocks (typically final concentration TCID50/mL > 10ˆ6 as titered on permissive Huh-7.5 hepatoma cells is ideal, diluted in hepatocyte medium). Infection is typically done by incubating MPCCs with virus for 24 hours.

69. Wash cultures 5 times and replace with fresh medium.

Every 48 hours, save supernatants (if desired – see Infection Analysis, steps 128, 142-158) and wash cultures 3 times with medium to remove leftover luciferase. Collection/wash frequency can be increased if daily samples are desired.

(Choice C; steps 70-82) Infecting MPCC with HBV [Figure 6]

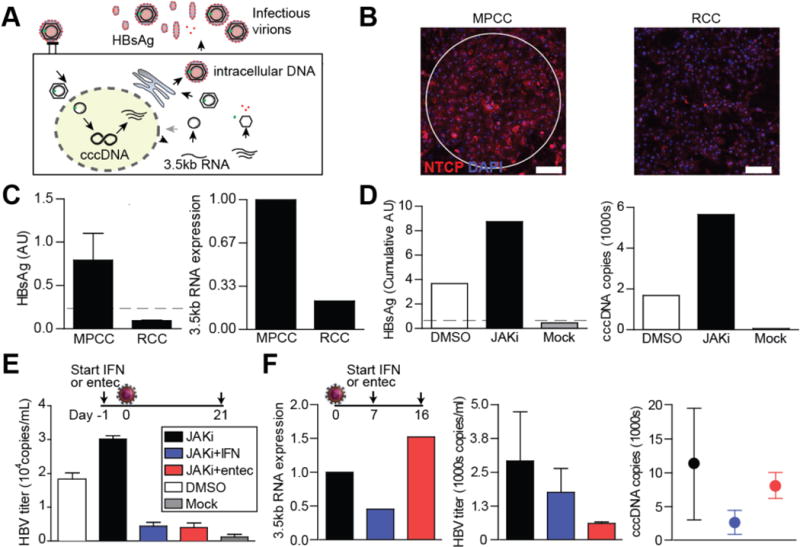

Figure 6. Application of MPCC for in vitro infection by Plasmodium parasite by HBV.

(A) HBV life cycle. (B) Immunofluorescent images of NTCP staining in MPCCs vs. random cocultures (RCCs); NTCP is the entry receptor for HBV. (C) HBV infection of MPCCs vs. RCCs shows that micropatterning is required for robust infection. (D) Robust infection based on multiple measures of viral life cycle is enhanced by inhibition of innate antiviral signaling. (E) Prophylactic drug treatment regimen prevents viral expansion. (F) Therapeutic drug treatment regimen abrogates established infection. Shlomai, Schwartz, Ramanan, et al. (2014) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Images reprinted courtesy of PNAS.

While it is possible to infect cells with HBV before or after 3T3-J2 seeding, we typically infect soon after fibroblast seeding. Infection can be performed up to at least 5 days after J2-3T3 seeding, depending on the application, although infection rates may decrease. The steps listed below outline the protocol for infecting 48 hours post hepatocyte seeding. Materials in contact with HBV should be decontaminated after use according to the appropriate safety protocols followed in your research environment.

Infection option 1: Infect with patient-derived HBV

70. Obtain de-identified patient plasma (Red Cross) that is HBV+, HCV−, HIV−

Genotype virus stocks ● TIMING 4h

71. Extract DNA from plasma.

72. Perform PCR using the following primers:

(F) 5′CTCCACCAATCGGCAGTC3′

(R) 5′AGTCCAAGAGTCCTCTTATGTAAGACCTT3′

73. Sequence PCR products using the following primer: 5′CCTCTGCCGATCCATACTGCGGAAC3′

74. Determine genotype using NCBI online genotyping tool. (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/genotyping/formpage.cgi)

Prepare viral stocks for infection ● TIMING 2-3h

75. Incubate HBV+ patient plasma with 25mM CaCl2 for 30 min at 37°C.

76. Spin gelled plasma at 14,000 × g for 5 min, then remove supernatant and transfer to new tube.

77. Repeat steps 75-76 until no visible clot remains at the end of the 5 minute spin. ▲ CRITICAL STEP: Ensure that no clot remains in the final viral stocks, or else clots may form over cells in culture upon infection. ■ PAUSE POINT Viral stocks can be frozen down at −80 °C at this step, although a decrease in viral titer may occur.

78. Because HBV derived from the plasma of different patients can vary widely in viral titer, it is important to test the supernatant from initial infectious inoculums for viral titer in each experiment. To maintain consistency across several experiments, it is also possible to pool viral stocks generated from plasma across many patients, and freeze down aliquots at this step.

Infection option 2: Infect with HBV from HepG2.2.15 cells ● TIMING 30 min for infection, length varies for supernatant collection

As an alternative to using HBV+ patient plasma, HBV virions can be produced and concentrated from the supernatant of HepG2.2.15 cells, as for example in82. The advantage to using HepG2.2.15-derived viral stocks is that virions can be set to a standard titer beforehand, and are additionally free of other plasma factors, antibodies to HBV, etc. that may compromise infection or affect the health of the MPCCs. Our initial experiments used HBV+ patient plasma because we were interested in infection with patient-derived virus, but this decision can be made on a case by case basis.

79. If desired, pre-incubate MPCCs for 24h with 10μM JAKi prior to infection; in our hands this step boosts HBV infection.

80. Dilute HBV stocks 1:10-1:20 in culture medium, and infect MPCCs for 24h.

81. After 24h, collect initial inoculums supernatant (to determine initial viral titer), wash MPCCs 5× with DMEM, and replace standard culture medium.

82. Collect and replace medium every 2 days, and store at −80 °C until collected medium is used for analysis of HBsAg, HBeAg, and secreted viral DNA. (Note: even with rigorous washing, HBsAg, HBeAg, and viral DNA from initial viral stocks may remain for up to 5 days post infection; thus, measurements taken before this time are subject to false positives).

Steps 83-184: Infection analysis

Infection analysis methods vary for each pathogen. If MPCC are infected with Plasmodium sporozoites, follow choice (A), and if infected with Hepatitis C virus (HCV), or Hepatatis B (HBV), follow choices (B) or (C), respectively.

(Choice A; steps 83-127) Plasmodium infection analysis [Figure 3, Figure 4]

Both fresh and cryopreserved Plasmodium sporozoites may demonstrate significant batch-to-batch variability in gliding motility16. Therefore, it may be helpful to quantify the percentage of gliding sporozoites as an indicator of sporozoite infectivity in parallel with the actual MPCC infection so as to allow the comparison of data from independent experiments, if such comparisons are desired. This sporozoite gliding assay, which is conceptually like a sandwich ELISA for sporozoites, is described in steps 83-96. Another sporozoite quality control assay measures sporozoite traversal of hepatocytes, which involves the use of a cell-impermeable fluorescent dextran in a cell membrane wounding and repair assay as described in steps 97-100. Depending on the goal of the experiment (e.g. testing the efficacy of a Plasmodium-specific blocking antibody), it may also be important to determine the efficiency of sporozoite invasion of hepatocytes at a very early time point after infection. This can be done using a double staining assay for sporozoite entry at 3h after infection (see steps 101-115). Routine analysis of productive liver-state malaria infection in MPCCs at various time points after infection is carried out using a standard immunofluorescence assay to detect various Plasmodium antigens expressed during the liver stage, including heat shock protein 70 (HSP70, pan-liver stage), merozoites surface protein-1 (MSP-1, mid-late liver stage) and erythrocyte-binding antigen-175 (EBA-175, late liver stage), as described in steps 116-127. For the following assays, use 50 μL and 300 μL per well of a 96- or 24-well plate, respectively. Typically, MPCCs are fabricated in glass-bottomed 96-well plates or on 12 mm glass coverslips in the wells of plastic 24-well plate.

Sporozoite gliding assay ● TIMING 4h

83. Prepare a solution of monoclonal antibody against Plasmodium circumsporozoite protein (anti-CSP, clone 2A10 for P. falciparum) in PBS.

84. Coat 12mm glass coverslips or glass-bottomed multi-well plates with the anti-CSP solution for 30 min at 37°C.

85. Wash coverslips or wells twice with PBS.

86. Add 20,000 sporozoites in DMEM to each coverslip, centrifuge at 600× g for 5 min, and incubate at 37°C for 40 min to allow motile sporozoites to glide.

87. Wash twice with PBS, add 4% PFA and incubate for 10-15 min at RT.

88. Wash thrice with PBS. ■ PAUSE POINT Samples can be stored at 4°C in PBS for 2 weeks.

89. Block with blocking solution (PBS + BSA 2% w/v) for 30 min at RT.

90. Add anti-CSP in blocking solution and incubate for 1h at RT.

91. Wash thrice with PBS.

92. Add the desired secondary antibody conjugated to a suitable fluorophore at 5 μg/mL in blocking solution and incubate for 1 hour at RT.

93. Wash thrice with PBS.

94. Place one drop of Aqua Mount into each well of the 96 well-plate. For MPCCs fabricated on 12 mm glass coverslips in the wells of plastic 24 well-plates, the glass coverslips should be mounted with Fluoromount G (~20 μL per coverslip) on glass slides for immunofluorescence imaging.

95. Place the mounted coverslips or the 96-well plates at 4°C overnight. Seal the 96-well plates with plate sealers to allow for a longer-term storage of the samples at 4°C.

96. Image the coverslips or the plates using an inverted fluorescence microscope, and quantify the percentage of gliding sporozoites. A gliding sporozoite is defined as one that leaves a CSP trail of at least one circle.

Cell membrane wounding and repair assay ● TIMING 3.5 h

97. Infect MPCCs with sporozoites in the presence of 1 mg/ml of 10,000 Da tetramethylrhodamine-dextran (lysine-fixable) (Sigma).

98. At 3 hours post-infection, wash wells twice with PBS, add 1% PFA and incubate for 20 min at RT.

99. Wash thrice with PBS, and mount samples as described above.

100. Image the coverslips or the plates using an inverted fluorescence microscope. Migration of sporozoites through cells is quantified by the number of dextran-positive hepatocytes per island.

Double-staining assay for sporozoite entry ● TIMING 5h

101. At 3 hours post-infection, wash wells twice with PBS, add 4% PFA and incubate for 10 – 15 min at RT.

102. Wash thrice with PBS. ■ PAUSE POINT Samples can be stored at 4°C in PBS for 2 weeks.

103. Block with blocking solution (PBS + BSA 2% w/v) for 30 min at RT.

104. Add anti-CSP in blocking solution and incubate for 1h at RT.

105. Wash thrice with PBS.

106. Add secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 at 5 μg/mL in blocking solution and incubate for 1 hour at RT.

107. Wash thrice with PBS.

108. Permeabilize samples with −20°C methanol for 10 min at 4°C. This allows the subsequent steps to label intracellular sporozoites.

109. Wash thrice with PBS.

110. Add anti-CSP in blocking solution and incubate for 1h at RT.

111. Wash thrice with PBS.

112. Add secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 594 at 5 μg/mL in blocking solution and incubate for 1 hour at RT.

113. Wash thrice with PBS, counterstain with Hoechst and mount samples as described above.

114. Image the coverslips or the plates using an inverted fluorescence microscope. Sporozoites that successfully entered hepatocytes should stain only with Alexa Fluor 594 (red), whereas sporozoites that remain extracellular stain with both Alexa Fluor 594 and Alexa Fluor 488 (green) and hence appear yellow.

Immunofluorescence staining of Plasmodium infected MPCCs ● TIMING 3h

116. At the desired terminal time point, aspirate the medium completely and wash the wells two times with PBS.

117. Add cold methanol (stored at −20°C) to each well and incubate the wells at 4°C for 10 min.

118. Completely aspirate methanol and wash the wells three times with PBS. ■ PAUSE POINT Samples can be stored at 4°C in PBS for 2 weeks.

119. Block each well with blocking solution (PBS + BSA 2% w/v) for 30 min at RT.

120. Add the desired primary antibody diluted in blocking solution and incubate for 1 hour at RT.

121. Aspirate the primary antibody solution and wash the samples twice with PBS.

122. Add the desired secondary antibody conjugated to a suitable fluorophore in blocking solution (Invitrogen; diluted 1:400 or at 5 μg/mL), and incubate for 50 min at RT.

123. Without washing, add the desired nuclear stain (DAPI or Hoechst 33342) at a final dilution of 2 ug/mL to the secondary antibody solution and incubate for an additional 10 minutes at RT.

124. Aspirate the secondary antibody and nuclear stain, and wash each well three times with PBS.

125. Place one drop of Aqua Mount into each well of the 96 or 24 well-plate. For MPCCs fabricated on 12 mm glass coverslips in the wells of plastic 24 well-plates, the glass coverslips should be mounted with Fluoromount G (~20 μL per coverslip) on glass slides for immunofluorescence imaging.

126. Place the mounted coverslips or the 96-well plates at 4°C overnight. Seal the 96-well plates with plate sealers to allow for a longer-term storage of the samples at 4°C.

127. Image the coverslips or the plates using an inverted fluorescence microscope. The identification of liver-stage malaria parasites, also known as exoerythrocytic forms (EEFs), is discussed in the section on anticipated results.

(Choice B; steps 128-158) HCV Infection analysis [Figure 3, Figure 5]

While RT-PCR kits are available for the assessment of viral content in supernatants or cell lysates (eg. See Eragen), we typically utilize a sensitive Gaussia luciferase (Gluc)-based viral reporter prepared as previously described85. This reporter expresses luciferase that is secreted into the culture medium, permitting viral quantitation by taking supernatant samples. Our other standard tool is the use of a fluorescent reporter that permits real-time evaluation of infection in single cells80. Use of both of these assays is described below.

Gaussia luciferase-HCV assay

128. Using the infection protocol described above, when cells are infected with Gluc-expressing HCV, supernatants collected throughout the course of the experiment can be assayed as described in the Kit. ▲ CRITICAL STEP: lysis buffer is essential to inactivate virus and stabilize luciferase activity. ● TIMING 2h

Viral (NS5B) polymerase inhibitor usage ● TIMING 15 min to add inhibitor

129. To ensure that luciferase detected in MPCC supernatants after infection with a Gluc-based reporter virus is indicative of active viral replication and not residual inoculum, we utilize a viral polymerase inhibitor control (2′-C-methyladenosine (2′CMA). 2′ CMA is used at approximately 50× IC50 (2.16mM) and should be applied after the HCV inoculum is removed. DMSO (0.1%) acts as a vehicle control and both 2′ CMA and DMSO are added fresh with media changes over the course of the experiment.

Generation of IPS-1 reporter-expressing lentivirus ● TIMING 4 days