Abstract

BACKGROUND:

If anxiety and depression do not detect in pregnant women, they may cause complications for the mother, child, and family, including postpartum depression. With regard to the administrative capability of relaxation in health centers, this study was conducted to determine the effect of progressive muscle relaxation and guided imagery on stress, anxiety, and depression in pregnant women.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

This randomized clinical trial was conducted on pregnant women in the city of Kashan at 28–36 weeks. At the onset of the study, demographic questionnaire, Edinburgh Depression Scale, and Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21) were completed. Providing obtaining score of mild-to-moderate in the stress, anxiety, and depression scale and score of 10 or higher in Edinburgh Depression Scale, individuals were divided randomized to the intervention group (n = 33) and control group (n = 33). DASS-21 was again completed in the 4th–7th weeks of beginning of the study by all women.

RESULTS:

Analysis of variance with repeated measures indicated significant differences in mean of scores of stress, anxiety, and depression at three different times in relaxation group (P < 0.05) whereas found no significant differences in the mean of scores of stress, anxiety, and depression in the control group.

CONCLUSIONS:

In this study, relaxation could reduce stress, anxiety, and depression in pregnant women during six sessions. Due to the simplicity and low cost of this technique, it can be used to reduce stress and anxiety in pregnant women and improve pregnancy outcomes.

Keywords: Anxiety, depression, guided imagery, pregnancy, relaxation therapy, stress

Introduction

Pregnancy for most women is a stressful experience because mothers must adapt to the new situation; for this reason, pregnancy is a time of increased vulnerability for the onset or relapse of a mental disorder.[1] Perinatal period is especially important as a maternal mood, and stress and anxiety problems are associated with adverse outcomes in pregnancy including parenting, disturbance in behavioral regulation, and unsafe attachment in children.[2] Around the world, around 10% of women during pregnancy and 13% of women after childbirth experience mental disorders, especially depression.[3] The past studies showed that a significant portion of pregnant women experience prenatal anxiety.[4] Mohammad Yusuff et al. reported that women experiencing anxiety during pregnancy are at a threefold risk of being depressed compared to women without anxiety.[5]

Depression in pregnancy is a major threat to the health of the mother and has serious implications for the mother and the fetus so should be identified and treated. Mild and moderate depression identified by screening tools can be assessed and treated in the primary care.[6,7] For mild-to-moderate depression, nondrug therapies should be used. The small numbers of therapists are available to provide this treatment, as against the high prevalence of depressive disorder, is a limiting factor. Primary care centers do not provide more than 30-min sessions, and usually, these centers do not employ people with mental health skills. There is a big gap between the proposed intervention and what people actually get there, so trying to find new and simpler solution is necessary to create beneficial effects and fewer side effects for the mother and infant. Regarding the time-consuming and costly of psychotherapy methods in the treatment of anxiety and depression, simpler procedures should be considered such as complementary medicine in the treatment of depression.

Recently, complementary medicine has been widely used in the prevention of disease and in health promotion.[8] Three common approaches of complementary medicine in the treatment of depression are relaxation, exercise, and plant therapy. Relaxation techniques such as methods of coping with stress, anxiety, and depression are simple psychotherapeutic methods and can be performed after brief training.[9,10] Jacobson progressive muscle relaxation is common. This technique is very easy to learn and serves as one of the best complementary therapies due to ease of learning and cost-savings and because it does not require special equipment, allowing easy implementation.[11,12]

A study of Rafiee et al. showed that in pregnant women with rate of low and intermediate anxiety, both methods reduce the anxiety score, but there was no difference between the two methods.[13] Malekzadegan et al. stated that progressive muscle relaxation increases the calmness of pregnant women. Increased levels of relaxation were caused decreased stress and adjustment of mental distress in individuals.[14]

Chambers’ study found that the effect of progressive muscle relaxation in reducing the negative mood in pregnant women with stress is not more than self-care. In fact, there was no change in the mood of pregnant women with stress by relaxation over time.[15] The study of Ahmadi Nejad et al. showed that depression, anxiety, and stress of the pregnant women were significantly lower in the progressive muscle relaxation group than those of the control group.[16]

The first-line treatment for postpartum depression is drug therapy with interpersonal psychotherapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy run by experts, while there are more simple methods that could be used with brief training by health professionals, including relaxation training. Relaxation techniques are complementary and noticed in the treatment of mood disorders due to control of self-care and have less side effects than other interventions. According to the contradiction of the results of the previous studies about the effects of this method on mental disorders, we decided to perform the study with the aim of measuring the effect of progressive muscle relaxation and guided imagery on stress, anxiety, and depression in pregnant women referred to health centers.

Materials and Methods

This study is a randomized clinical trial of pregnant women with the gestational age of 28–36 weeks in the health centers from September 2013 to November 2014. This protocol complies with the guidelines of Declarations of Helsinki and Tokyo, for humans and approved by ethics committee of the University of Medical Science. The researcher has been trained by a Master of Clinical Psychology in performing relaxation techniques. Cluster sampling was used to determine the health centers in Kashan. Five centers were selected. After explaining the purpose of the study by the researcher, the women provided informed consent form. Sociodemographic questionnaires were completed through interviews. The inclusion criteria were literate women, 18–35 years old, singleton pregnancy, gestational age 28–36 weeks, and body mass index between 19.8 and 29 of the first trimester, and the exclusion criteria were smoker, drugs and alcohol abuse, medication or hospitalization due to mental health problems, abortion more than twice, infertility, pregnancy complications, pain, or bleeding.

At first, the Edinburgh Depression Scale and Scale of Stress, Anxiety, and Depression (DASS-21) were completed by pregnant women. Women who scored 15–25 on stress or 8–14 on anxiety or 10–20 on depression and scored 10 or above on Edinburgh Depression Scale were randomly assigned into two groups: relaxation and control. Interventions in the relaxation group were performed for 6 weeks. In the relaxation group, the first two sessions of relaxation were performed in the health center. In the first session of relaxation training, the causes of postpartum depression and the ways of controlling it were discussed, and the relaxation purposes were explained. Furthermore, women were trained about how to contract and relax their 16 groups of muscles. Then, the practice was repeated once in the presence of a researcher by a training mother.

In the second session, progressive muscle relaxation technique was performed once again by a mother in the presence of the researcher, and after correction and ensuring the accuracy of the technique, a CD of progressive muscle relaxation was given to the women to perform the exercise daily at home. In the next four sessions, in addition to the exercises of relaxation performed at home, imagery techniques were performed by a researcher. The relaxation exercise was performed by the women at home for about 20 min daily.

In the control group, based on the manual of national safe motherhood, care of pregnancy was routine. DASS-21 again was completed by the mothers in the 4th week of study and 7 weeks after beginning of the study in two groups: control and relaxation.

After collecting and coding data, data were entered into SPSS version 16 and statistical analysis was performed. Using paired t-test, the changes in each group were compared to the base. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures (repeated measurement) was used for the study of the effect of time and group therapy on stress, anxiety, and depression. By Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, the normality of quantitative variables was determined. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

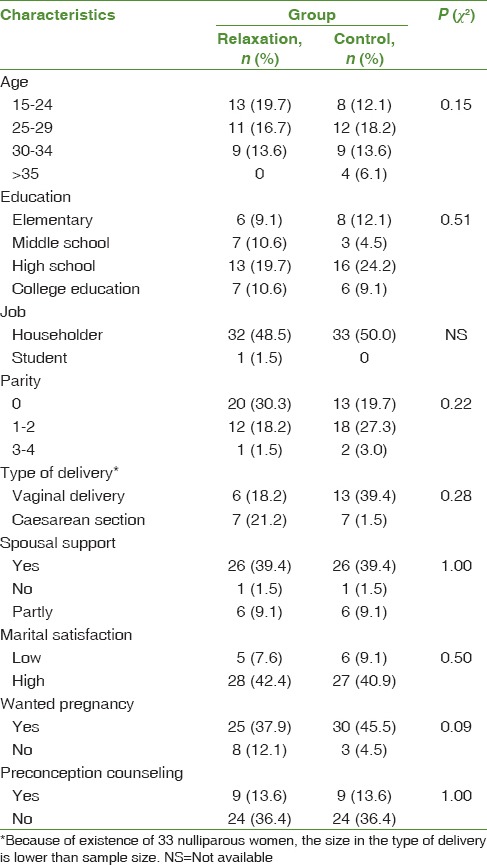

The findings showed there were no significant statistical differences in variables of demographics and perinatal situation, including age, education, job, income, parity and type, spousal support, and preconception counseling between the relaxation and control groups [Table 1]. t-test results indicated that the two groups in the social support (P = 0.869) and Edinburgh Depression Scale score (P = 0.812) were similar at baseline.

Table 1.

Distribution of demographic and perinatal variables in relaxation and control groups

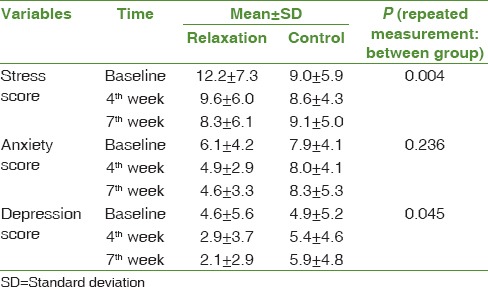

Paired t-test showed that scores of stress, anxiety, and depression in pregnant women before and after the intervention in the relaxation group had a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05). Means of scores for stress, anxiety, and depression after relaxation exercises for pregnant women showed a significant decline. Paired t-test results showed that stress (P = 0.874), anxiety (P = 0.609), and depression (P = 0.053) scores had no significant difference at the beginning and end of the study in the control group.

Independent t-test results did not show a significant difference in the mean of stress score (P = 0.056) and anxiety score (P = 0.093) between the two groups at baseline. The mean score of stress significantly decreased in the relaxation group in the 4th week and at the end of the treatment, while the mean of score of stress had no significant change in the control group at three time points before and after the study and in the 4th week of the study. ANOVA with repeated measures showed that measuring stress score at three different times are significantly different (P = 0.004). In other words, over time, stress scores in the two groups had changed (P = 0.002). These results show the effectiveness of relaxation to reduce stress in pregnant women from 4th to 7th weeks [Table 2].

Table 2.

The comparison of changes of mean of stress, anxiety, and depression scores in baseline and the 4th and 7th week in relaxation and control groups

The mean of anxiety scores in the 4th week of relaxation and after the end of the treatment significantly decreased, while the mean score of anxiety had no significant change in the control group before and end of the study and the 4th week of the study. ANOVA with repeated measures showed that there is no significant difference in the measure of anxiety scores at three different times (P = 0.236). In other words, over time, anxiety scores in the two groups had no significant change.

The Mann–Whitney test showed no significant difference in mean of depression scores between the two groups at baseline (P = 0.857). The mean of depression score significantly decreased in the 4th week and after the end of treatment in the relaxation group, while the mean of depression scores in the control group at three time points before and after and the 4th week of the study had no significant change. ANOVA with repeated measures showed that measuring depression score had significant differences with each other at three different times (P = 0.045). In other words, over time, depression scores in the two groups changed. These results show that the effectiveness of relaxation for reducing depression is maintained in pregnant women during 7 weeks.

Discussion

The results showed that the stress, anxiety, and depression in pregnant women at 4 and 7 weeks through exercises of progressive muscle relaxation and guided imagery can be reduced. Furthermore, the findings showed that the mean of scores of stress, anxiety and depression before and after the intervention had significant differences in the relaxation group, whereas in the control group, the mean scores of stress, anxiety, and depression showed no significant difference beginning and end of the study. Mean of scores reduced for stress, anxiety, and depression in the relaxation group was respectively, 31.9, 24.5, and 54.3%; while in the control group, not only did scores of stress, anxiety, and depression not decrease but also scores increased compared with baseline.

Akbarzadeh et al. (2013) in Shiraz studied the effect of relaxation and attachment behavior training on anxiety in nulliparous women. The study of three groups (relaxation, training of attachment behaviors, and control) was performed for 4 weeks (once a week). At the end of the study, there were significant differences between anxiety scores in the intervention group and the control group.[17] The results of the present study are consistent with the Akbarzadeh study. In the current study, relaxation exercises were performed on a daily basis for 6 weeks at home, and guided imagery sessions were held at the health center, once a week; while in the Akbarzadeh study, exercises were performed only once a week for 4 weeks. The tool used in the Akbarzadeh study was a Spielberger Anxiety Inventory questionnaire and this study was used DASS-21.

A study of Chambers showed that relaxation training and self-care act similarly in reducing the negative mood in women with high stress in gestational age of 14–28 weeks. Perhaps, due to training of women how to deal with stress and to overcome the difficulties, the stress and anxiety scores reduced in a self-care approach.[15] In this study, only routine care was performed in the control group, so, fear, stress, and disturbing thoughts increased stress and anxiety and even depression in the control group. In addition, in Chambers’ study, women were in the second trimester of pregnancy, which is usually a safe trimester, while they were included in the current study in the third trimester of pregnancy. Due to the approach to birth time, the stress and anxiety of pregnant women increase, which is evident in the control group.

Nasiri compared two methods of problem-solving and relaxation on the severity of depressive symptoms of postpartum period. They found that both methods can reduce the scores of depression in the postpartum period although problem-solving was more effective than relaxation. Furthermore, the symptoms of depression reduced in the control group. Researchers reported that the reason for the decline of symptoms in women was a weekly visit to health centers.[18] Any intervention that had aspects of support and advice and attention by the midwife can reduce the incidence of anxiety and depression in women. In this study, midwives focused on physical complaints such as nausea and vomiting, and so, women have less psychological support, for this reason, concerns of women doubles. In the Nasiri's study, the reduction in depression scores of women in the postpartum period was 76.9% in the relaxation group, while in the current study in pregnancy, depressive symptoms were reduced by relaxation by 54.3%. Perhaps, various stressors during pregnancy caused relaxation less able to reduce depression.

With regard to the relationship between stress, anxiety, and depression, it can be said that the more stress is reduced; anxiety and depression are expected to decrease in the same proportion. As the results show, the mean of stress score reduces only 31.9% in the relaxation group. Smith et al. compared the effects of yoga and relaxation to reduce stress and anxiety and concluded that both yoga and relaxation can reduce stress and anxiety in people. However, the two groups showed no significant difference in the levels of stress and anxiety after the treatment. The study was done in patients with mild to moderate levels of stress in South Australia. The intervention lasted 10 weeks.[19] Although the present study was conducted for 6 weeks of relaxation, the results showed the effectiveness of relaxation on stress, anxiety, and depression. The findings also showed that the stress, anxiety, and depression significantly decreased in the relaxation group compared to the control group during the 6 weeks. Despite the decrease in anxiety scores in the relaxation group, in the 4th week, the process of change in anxiety scores was not significant at the time. Women participating in the study were in the third trimester. Perhaps, because of the approaching birth time, concerns about the unborn child, what happens during labor or after delivery, women's anxiety increases and disturbing thoughts do not allow the mother to optimally perform relaxation exercises.[20,21] It also has been shown the increasing of the number of training sessions for relaxation to 12 sessions increases the effectiveness of this method. Therefore, it is recommended that if relaxation is implemented for pregnant women, preferably it should continue until the delivery and postpartum period.

The Urech et al.'s study found that both guided imagery and progressive muscle relaxation can reduce heart rate, but guided visualization alone was significantly more effective for raising the comfort levels among pregnant women. In this study, it was found that a variety of relaxation techniques can have different effects on biological systems and psychological stress of individuals.[22] In the current study, the positive effects of two methods of progressive muscle relaxation and guided imagery were combined in raising the comfort level.

Limitations

The limitations of this study were that it evaluated the effect of relaxation within a short period (6 weeks) because pregnant women during childbirth suffer more than other times from anxiety and stress, it is suggested that future studies be done over a longer time until birth. The possible effect of individual differences in research on depression, anxiety, and stress was another limitation. The attempt was made for controlling the issue by randomly assigning research units to groups.

Conclusions

The results of this study indicate that relaxation reduces stress, anxiety, and depression in pregnant women, and due to the ease of implementation of this method in health centers and at home, it could be part of the training in routine care during pregnancy that women can improve their performance by this method against environmental stressors.

Financial support and sponsorship

The study was supported by the Research Deputy of Kashan University of Medical Sciences.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The study is parts of a research project approved by Vice Chancellor for Research at Kashan University of Medical Sciences, Kashan, Iran (code: 91130). We would like to thank the Research Deputy of Kashan University of Medical Sciences for financially supporting this project and all who sincerely cooperated in the study. We also express our deepest gratitude to the subjects, who participated in this study.

The trial is registered at IRCT.ir, number IRCT2014112220035N1.

References

- 1.Smith MV, Shao L, Howell H, Lin H, Yonkers KA. Perinatal depression and birth outcomes in a healthy start project. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15:401–9. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0595-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunkel Schetter C, Tanner L. Anxiety, depression and stress in pregnancy: Implications for mothers, children, research, and practice. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2012;25:141–8. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283503680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Maternal Mental Health. 2016b. [Last accessed on 2016 Apr 01]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/maternal-child/maternal_mental_health/en/

- 4.Dunkel Schetter C. Psychological science on pregnancy: Stress processes, biopsychosocial models, and emerging research issues. Annu Rev Psychol. 2011;62:531–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.031809.130727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohamad Yusuff AS, Tang L, Binns CW, Lee AH. Prevalence and risk factors for postnatal depression in Sabah, Malaysia: A cohort study. Women Birth. 2015;28:25–9. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woods SM, Melville JL, Guo Y, Fan MY, Gavin A. Psychosocial stress during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(61):e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Musters C, McDonald E, Jones I. Management of postnatal depression. BMJ. 2008;337:a736. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Close C, Sinclair M, Liddle SD, Madden E, McCullough JE, Hughes C, et al. A systematic review investigating the effectiveness of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) for the management of low back and/or pelvic pain (LBPP) in pregnancy. J Adv Nurs. 2014;70:1702–16. doi: 10.1111/jan.12360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jorm AF, Morgan AJ, Hetrick SE. Relaxation for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008 Oct;8(4):CD007142. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007142.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alwan M, Zakaria A, Abdul Rahim M, Abdul Hamid N, Fuad M. Comparison between two relaxation methods on competitive state anxiety among college soccer teams during pre-competition stage. Int J Adv Sport Sci Res. 2013;1:90–104. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Varvogli L, Darviri C. Stress management techniques: Evidence-based procedures that reduce stress and promote health. Health Sci J. 2011;5:74–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chuang LL, Lin LC, Cheng PJ, Chen CH, Wu SC, Chang CL, et al. Effects of a relaxation training programme on immediate and prolonged stress responses in women with preterm labour. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68:170–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rafiee B, Akbarzadeh M, Asadi N, Zare N. Comparing the effects of educating of attachment and relaxation on anxiety in third trimester of pregnancy and postpartum depression in the primipara women. Hayat. 2013;19:76–88. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malekzadegan A, Moradkhani M, Ashayeri H, Haghani H. Effect of relaxation on insomnia during third trimester among pregnant women. IJN. 2010;23:52–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chambers A. Relaxation during Pregnancy to Reduce Stress and Anxiety and Their Associated Complications. Degree of Doctor of Philosophy: The University of Arizona. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahmadi Nejad FS, Golmakani N, Asghari Pour N, Shakeri M. Effect of progressive muscle relaxation on depression, anxiety, and stress of primigravid women. Evid Based Care. 2015;5:67–76. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akbarzadeh M, Toosi M, Zare N, Sharif F. Effect of relaxation and attachment behaviors training on anxiety in first-time mothers in Shiraz city, 2010: A randomized clinical trial. Qom Univ Med Sci J. 2013;6:14–23. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nasiri S. “Comparing the Effects of Problem-Solving Skills and Relaxation on the Severity of Depression Symptoms in the Postpartum Period.”. Degree of Master of Science: The University of Mashhad. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith C, Hancock H, Blake-Mortimer J, Eckert K. A randomized comparative trial of yoga and relaxation to reduce stress and anxiety. Complement Ther Med. 2007;15:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vélez RR. Pregnancy and health-related quality of life: A cross sectional study. Colomb Med. 2011;42:476–81. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ryan A. Interventions to reduce anxiety during pregnancy: An overview of research. NCT's. 2013;19:16–20. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Urech C, Fink NS, Hoesli I, Wilhelm FH, Bitzer J, Alder J, et al. Effects of relaxation on psychobiological wellbeing during pregnancy: A randomized controlled trial. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35:1348–55. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]