Abstract

The expression of the phosphate transporter Pho84 in fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe is repressed in phosphate-rich medium and induced during phosphate starvation. Two other phosphate-responsive genes in S. pombe (pho1 and tgp1) had been shown to be repressed in cis by transcription of a long noncoding (lnc) RNA from the upstream flanking gene, but whether pho84 expression is regulated in this manner is unclear. Here, we show that repression of pho84 is enforced by transcription of the SPBC8E4.02c locus upstream of pho84 to produce a lncRNA that we name prt2 (pho-repressive transcript 2). We identify two essential elements of the prt2 promoter, a HomolD box and a TATA box, mutations of which inactivate the prt2 promoter and de-repress the downstream pho84 promoter under phosphate-replete conditions. We find that prt2 promoter inactivation also elicits a cascade effect on the adjacent downstream prt (lncRNA) and pho1 (acid phosphatase) genes, whereby increased pho84 transcription down-regulates prt lncRNA transcription and thereby de-represses pho1. Our results establish a unified model for the repressive arm of fission yeast phosphate homeostasis, in which transcription of prt2, prt, and nc-tgp1 lncRNAs interferes with the promoters of the flanking pho84, pho1, and tgp1 genes, respectively.

Keywords: transcription regulation, RNA polymerase II, transcription factor, promoter, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, long noncoding RNA, Pho84, phosphate homeostasis, phosphate transporter

Introduction

Fungi respond to phosphate starvation by inducing the transcription of phosphate acquisition genes (1). The phosphate regulon in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe comprises three genes that specify, respectively, a cell-surface acid phosphatase Pho1, an inorganic phosphate transporter Pho84, and a glycerophosphate transporter Tgp1 (2). Expression of pho1 and tgp1 is actively repressed during growth in phosphate-rich medium by the transcription in cis of a long noncoding (lnc)3 RNA from the 5′-flanking genes prt and nc-tgp1 (3–8). The prt lncRNA initiates 1147 nucleotides (nt) upstream of the pho1 mRNA transcription start site (Fig. 1A). The nc-tgp1 lncRNA initiates 1823 nt upstream of the tgp1 mRNA start site.

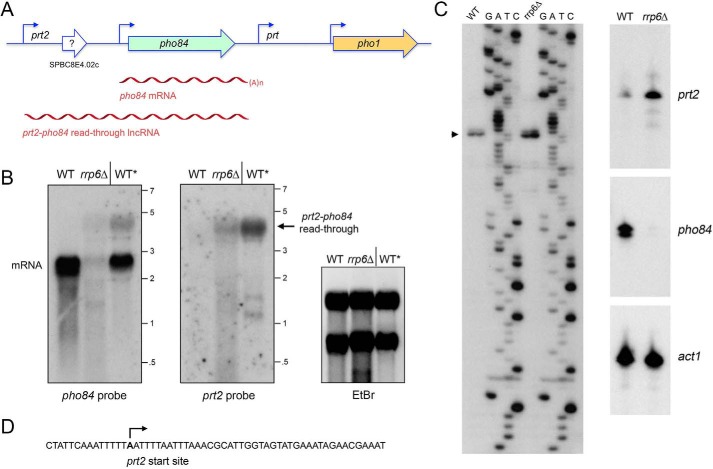

Figure 1.

Characterization of a prt2 lncRNA initiating from the SPBC8E4.02c locus. A, schematic illustration of the S. pombe chromosome II locus spanning genes SPBC8E4.02c (prt2), pho84, prt, and pho1. The pho84 and pho1 open reading frames are denoted by green and gold horizontal arrows, respectively, in the direction of mRNA synthesis. An annotated ORF in the middle of SPBC8E4.02c is depicted as a blank arrow with ? indicating the dubiousness of the predicted polypeptide. Experimentally determined 5′ ends of the pho84 and pho1 mRNAs and the prt2 and prt lncRNAs are indicated by bent arrows. The pho84 mRNA and prt2-pho84 read-through lncRNA are depicted as red wavy lines below their respective loci. B, Northern blot analysis of RNA from exponentially growing wildtype (WT) and rrp6Δ cells and from stationary phase wildtype cells (WT*). The RNA was resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis and stained with ethidium bromide to visualize 28S and 18S rRNA (right panel) prior to transfer to membrane and hybridization with 32P-labeled pho84 (left panel) or prt2 (middle panel) probes. Annealed probes were visualized by autoradiography. The positions and sizes (kb) of single-stranded RNA markers are indicated on the right. C, left panel, to map the 5′ end of the prt2 RNAs, we analyzed the reverse transcriptase primer extension products templated by total RNA from either WT or rrp6Δ cells in parallel with a series of DNA-directed primer extension reactions that contained mixtures of standard and chain-terminating nucleotides (the chain terminator is specified above the lanes). The primer extension products were analyzed by electrophoresis through a 42-cm denaturing 8% polyacrylamide gel and visualized by autoradiography of the dried gel. The 5′ RNA end is denoted by ▶. Right panel, 32P-labeled oligonucleotide primers complementary to prt2 lncRNA, and pho84 and act1 mRNAs were annealed to total RNA from WT or rrp6Δ strains and extended with reverse transcriptase. The reaction products were analyzed by denaturing PAGE and visualized by autoradiography. D, sense strand DNA sequence flanking the prt2 transcription start site is shown, with the start site denoted by bent arrow.

pho1 expression from the prt-pho1 locus and tgp1 expression from the nc-tgp1-tgp1 locus are both inversely correlated with the activity of the lncRNA promoters. Transcription of the prt and nc-tgp1 lncRNAs is driven by distinctive bi-partite promoters, consisting of a HomolD box and a TATA box located sequentially within a 100-nt segment preceding the start sites (6, 8). Mutations in the HomolD and TATA boxes of the prt or nc-tgp1 genes result in de-repression of the downstream pho1 or tgp1 promoters in phosphate-replete cells. The ensuing synthesis of the pho1 and tgp1 mRNAs (as well as their induction during phosphate starvation) depends on the DNA-binding transcription factor Pho7 (2, 9), which recognizes a 12-nt sequence motif (5′-TCG(G/C)(A/T)XXTTXAA) present in the pho1 and tgp1 promoters (10). A simple model for the repressive arm of fission yeast phosphate homeostasis is that transcription of the upstream lncRNA interferes with expression of the downstream genes encoding Pho1 or Tgp1 by displacing Pho7 from the pho1 and tgp1 promoters (6–8).

The basal level of pho1 expression is also governed by the phosphorylation state of the carboxyl-terminal domain (CTD) of the Rpb1 subunit of RNA polymerase II (pol II). For example, CTD mutations that prevent installation of the Ser7-PO4 or Ser5-PO4 marks de-repress pho1 in phosphate-replete cells. By contrast, prevention of the Thr4-PO4 mark hyper-represses pho1 under phosphate-rich conditions (5). Because such CTD mutations do not affect the activity of the prt or pho1 promoters per se, it is proposed that CTD status affects pol II termination during prt lncRNA synthesis and thus the propensity to displace Pho7 from the pho1 promoter (6). Absence of CTD Ser7-PO4 or limitation of Ser5-PO4 elicits a similar de-repression of transcription from the tgp1 promoter in phosphate-replete cells, without affecting the activity of the nc-tgp1 promoter (8). tgp1 de-repression by limiting Ser5-PO4 entails a switch in nc-tgp1 poly(A) site utilization to generate a short nc-tgp1 RNA that does not interfere with the tgp1 promoter (8).

The third gene in the fission yeast phosphate regulon, pho84, is situated immediately upstream of the prt-pho1 locus (Fig. 1A). Previously, we mapped the 5′ ends of the pho84 mRNA to a pair of sites located 151 and 149 nt upstream of the start codon of the pho84 open reading frame (Fig. 1A) (5). We noted concordant effects of CTD phospho-site mutations on the levels of pho1 and pho84 mRNAs in phosphate-replete cells (5). Also, the induction of both pho1 and pho84 during phosphate starvation was delayed in rrp6Δ cells that accumulate high levels of prt lncRNA (5). These results raised the prospect that the prt lncRNA might act as a repressor of both upstream and downstream protein-coding genes. Alternatively, there could be another regulatory RNA, distinct from prt but also increased in rrp6Δ cells, that controls pho84 expression.

Here, we report that the latter model is correct. We find that the fission yeast SPBC8E4.02c gene located upstream of pho84 (Fig. 1A) specifies a lncRNA that represses pho84 expression. We named this locus prt2 (pho-repressive transcript 2). Here, we characterize the prt2 lncRNA, define the prt2 promoter, and show that inactivation of the prt2 promoter up-regulates the pho84 promoter in phosphate-replete cells. We describe a cascade effect of prt2 promoter inactivation on the downstream prt-pho1 locus, whereby increased pho84 transcription down-regulates prt and thereby de-represses pho1.

Results

Characterization of a prt2 lncRNA initiating from the SPBC8E4.02c locus

Given the precedents of prt and nc-tgp1 lncRNAs regulating their 3′-flanking protein-coding genes, we inspected the genomic region upstream of pho84 as a potential source of a candidate pho84-regulatory RNA. As annotated in PomBase (www.pombase.org),4 the pho84 gene is flanked by a co-oriented gene SPBC8E4.02c (Fig. 1A), spanning 1618 nt and abutting the 5′ end of pho84. In the center of the SPBC8E4.02c locus is a 387-nt ORF (indicated by the arrow in Fig. 1A) with the potential to encode a 129-amino acid polypeptide, annotated as an “uncharacterized S. pombe-specific protein.” Our search of the NCBI database retrieved no hits, even from closely related species in the genus Schizosaccharomyces. The lack of homology, and the presence of upstream AUG elements in the putative 5′-UTR, led us to suspect that SPBC8E4.02c is not a coding gene. Our hypothesis was that SPBC8E4.02c specifies a lncRNA with a regulatory function vis à vis pho84, akin to how prt regulates pho1. Thus, we designated the SPBC8E4.02c gene as prt2.

Northern analysis of total RNA from logarithmically growing phosphate-replete wildtype S. pombe cells using a pho84 probe detected an ∼2.3-kb transcript corresponding to the pho84 mRNA (Fig. 1B). By contrast, we did not detect a discrete prt2 transcript in wildtype cells (Fig. 1B). This is consistent with genome-wide RNAseq data (11) showing that the pho84 transcript is present in log-phase cells, while there are scant sequence reads derived from the SPBC8E4.02c (prt2) locus (Fig. S1). However, RNAseq analysis of stationary phase fission yeast cells revealed that the entirety of the prt2-pho84 locus is transcribed into RNA (Fig. S1). In light of these data, we performed Northern analysis of RNA from stationary phase wildtype S. pombe (lanes WT* in Fig. 1B). Now, the prt2 probe highlighted an ∼4.3-kb transcript that was also detected by the pho84 probe (which also detected the pho84 mRNA in stationary-phase cells). We surmise that the predominant transcript derived from prt2 in stationary phase is a prt2-pho84 read-through lncRNA. (Two minor transcripts of about 1.2 and 1.4 kb were detected in stationary-phase cells by the prt2 probe but not the pho84 probe (Fig. 1B); these RNAs were not characterized further.)

Further insights were gleaned from Northern analysis of RNA from log-phase rrp6Δ cells, in which the prt2-pho84 read-through lncRNA was present, but the pho84 mRNA was reduced sharply (Fig. 1B).

We employed reverse-transcriptase (RT) primer extension analysis to map the 5′ end of the prt2 RNA. A 32P-labeled DNA primer complementary to nt −1642 to −1665 upstream of the pho84 ORF was annealed to total yeast RNA from wildtype or rrp6Δ cells and then subjected to reverse transcription. The RT primer extension products were analyzed by denaturing PAGE in parallel with a chain-terminated sequencing ladder generated by DNA polymerase-catalyzed extension of the same 32P-labeled primer annealed to a DNA template extending from nt −1951 to −1482 upstream of the pho84 ORF (Fig. 1C). A predominant 5′ end initiating with adenosine was thereby located 1559 nt upstream of the pho84 transcription start site (Fig. 1, A, C, and D). A minor 1-nt longer RT primer extension product was also detected (Fig. 1C), which signified either (i) transcription initiation at the 5′-flanking T or (ii) an extra RT nucleotide addition opposite a 5′ cap guanosine of the prt2 RNA. Identical prt2 RNA ends were detected using a different primer complementary to nt −1597 to −1624 upstream of the pho84 ORF (not shown). The presence of 10 ATG triplets in the interval between the prt2 start site and the annotated ATG of the putative SPBC8E4.02c ORF is consistent with prt2 being a lncRNA rather than an mRNA. In support of this conclusion, deep analyses by mass spectrometry of the protein contents of the fission yeast cell have failed to detect any peptides derived from the putative SPBC8E4.02c ORF (12, 13), while readily detecting the Pho84 polypeptide at a level of ∼12,000 molecules per cell (13).

A salient point was that the intensity of the primer extension signal for prt2 was greater when the analysis was performed with total RNA from rrp6Δ cells versus wildtype rrp6+ cells (Fig. 1C, right panels; the internal control being that the primer extension signal for actin mRNA was virtually the same when using the equivalent amounts of RNA from rrp6Δ and rrp6+ cells). By contrast, the primer extension signal for pho84 mRNA was nearly effaced in rrp6Δ cells, suggesting that basal prt2 and pho84 expressions are anti-correlated (Fig. 1C, right panels).

How might we reconcile the observation that the pho84 mRNA is present by Northern analysis in stationary phase WT cells, but not in log-phase rrp6Δ cells, notwithstanding that the prt2-pho84 read-through transcript was present in both cases. We would speculate that the presence of the prt2-pho84 read-through RNA in stationary phase reflects an absence of termination of prt2 transcription prior to reaching the pho84 poly(A) site that occurs when cells enter into stationary phase. A parsimonious explanation for the presence of pho84 mRNA in stationary phase cells is that this pho84 mRNA was synthesized during the period of logarithmic growth that preceded entry into stationary phase and that the pho84 mRNA persists in the cells at the time we harvested them. The situation is different in log-phase rrp6Δ cells, as follows. The increased level of prt2 transcript detected by primer extension likely reflects increased prt2 stability when the nuclear exosome is defective. Yet, as shown previously for prt and pho1, it is not simply the steady-state level of the lncRNA that elicits repression of the downstream mRNA, it is the process of lncRNA synthesis across the mRNA promoter that counts. Evidence that the nuclear exosome promotes non-canonical pol II transcription termination in fission yeast (14) has prompted the suggestion that the exosome thereby mitigates read-through RNA synthesis that would interfere with expression of neighboring genes (4, 14–16). In this vein, we envision that an increase in read-through prt2 transcription in log-phase rrp6Δ cells accounts for the observed effacement of pho84 mRNA.

Insertional inactivation of prt2 de-represses pho84 transcription

We made two versions of a prt2-inactivating chromosomal insertion (Fig. 2A). The prt2-Δ1 strain deletes the chromosomal segment from 217 nt upstream of the prt2 transcription start site to 14 nt downstream of the start site and replaces it with a hygromycin resistance marker (hygR) in reverse orientation to pho84. Primer extension analysis with a prt2 antisense primer corresponding to nt +61 to +38 affirmed that the properly initiated prt2 transcript was present in the wildtype prt2 strain but absent in prt2-Δ1 (Fig. 2B). The prt2-Δ2 strain has the hygR marker in lieu of the segment from 217 nt upstream of the prt2 transcription start site to 532 nt downstream of the start site (Fig. 2A). (In this case, no prt2 primer extension product was detectable, because the sequence to which the antisense primer anneals was part of the deleted prt2 DNA.) The instructive findings were that the level of the pho84 mRNA, as gauged by primer extension, was increased by 3-fold in the prt2-Δ1 and prt2-Δ2 strains versus the wildtype strain (Fig. 2B). Thus, prt2 transcription down-regulates pho84 expression and cessation of prt2 transcription de-represses pho84 under phosphate-replete conditions.

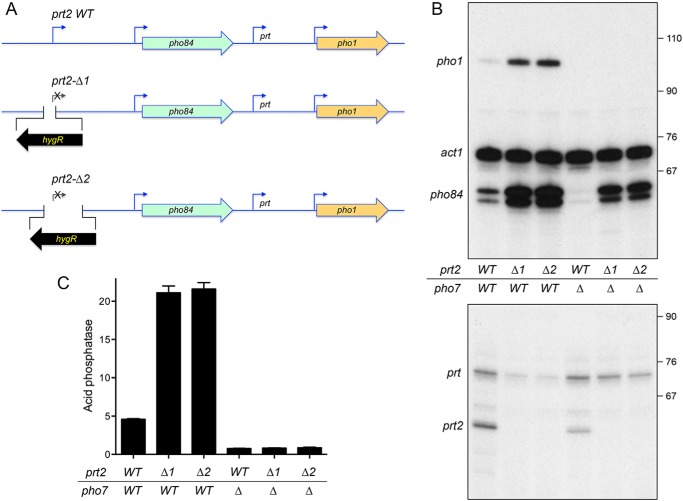

Figure 2.

How insertional inactivation of prt2 affects the expression of downstream genes. A, schematic depiction of the wildtype prt2-pho84-prt-pho1 gene cluster on chromosome II and two prt2-inactivating mutants (Δ1 and Δ2) in which the bracketed segments flanking the prt2 transcription start site were deleted and replaced with an oppositely oriented gene that confers hygromycin resistance (hygR). B, total RNA from fission yeast cells with the indicated prt2 and pho7 genotypes was analyzed by reverse transcription primer extension using a mixture of radiolabeled primers complementary to the pho84, act1, and pho1 mRNAs (top panel) or the prt and prt2 lncRNAs (bottom panel). The reaction products were resolved by denaturing PAGE and visualized by autoradiography. The positions and sizes (nt) of DNA markers are indicated on the right. C, acid phosphatase activity of the indicated strains grown in rich medium was assayed by conversion of p-nitrophenyl phosphate to p-nitrophenol. The y axis specifies the phosphatase activity (A410) normalized to input cells (A600). The error bars denote S.E.

Cascade effect of prt2 inactivation on downstream prt and pho1 gene expression

Primer extension analysis with a pho1-specific antisense primer revealed that insertional inactivation of prt2 in the Δ1 or Δ2 strains elicited a 5-fold increase in the level of pho1 mRNA compared with wildtype prt2 (Fig. 2B). This induction of pho1 mRNA expression was also evident at the protein level as a 4-fold increase in cell-surface Pho1 acid phosphatase activity in the prt2-Δ strains compared with wildtype (Fig. 2C). Primer extension with a prt-specific antisense primer showed that pho1 induction by prt2-Δ correlated with a decrease in the level of the repressive upstream prt transcript (Fig. 2B). These experiments unveiled an unexpected long-range cascade effect of perturbing prt2-pho84 on the neighboring prt-pho1 locus. To wit: shutting off prt2 de-represses pho84; increased pho84 transcription down-regulates prt; and reducing prt transcription de-represses pho1.

Parallel analysis of the wildtype prt2 and prt2-Δ RNA levels in a pho7Δ genetic background revealed differential dependences of pho1 and pho84 on the Pho7 transcription factor, whereby the induction of pho1 transcription and acid phosphatase activity via prt2-Δ was eliminated in the absence of Pho7 (Fig. 2, B and C). By contrast, there was substantial residual pho84 mRNA expression in pho7Δ prt2-Δ cells (Fig. 2B).

pho84 mRNA polyadenylation sites

To better define the prt2-pho84-prt-pho1 gene cluster, we mapped the sites of polyadenylation of the pho84 mRNA by 3′-RACE using as templates total RNA isolated from phosphate-replete and phosphate-starved wildtype cells. Sequencing of 16 independent cDNA clones revealed six different poly(A) sites clustered within a 62-nt segment of the pho84 3′UTR. 6/16 cDNA clones had the identical junction to a poly(A) tail at a site 230 nt downstream of the pho84 translation stop codon (Fig. S2). 4/16 cDNA clones had a poly(A) site 234 nt downstream of the pho84 stop codon. These two predominant pho84 poly(A) sites are located 16 and 20 nt downstream of a fission yeast AAUAAA polyadenylation signal (PAS) (Fig. S2) (17). In addition, two cDNA clones had poly(A) sites 13 nt downstream of this PAS, and one cDNA clone was polyadenylated 30 nt downstream of this PAS. The remaining three cDNA clones defined two other poly(A) sites 183 and 185 nt downstream of the pho84 stop codon (Fig. S2). These poly(A) sites are located 18 and 20 nt downstream of a separate AAUAAA polyadenylation signal (Fig. S2). The major pho84 poly(A) site is 158 nt upstream of the transcription start site of the flanking prt lncRNA and 83 nt upstream of the HomolD box of the prt promoter. pol II elongation complexes synthesizing the pho84 mRNA will undergo nascent strand 3′ cleavage at the poly(A) sites and (in all likelihood) ensuing transcription termination (18) within the downstream DNA region that overlaps the prt promoter, thereby suggesting a scenario for how increased pho84 transcription could interfere with prt transcription.

prt2 transcription: What comprises a prt2 promoter?

To address this question, we constructed a plasmid reporter in which the pho1 ORF and its native 3′-flanking DNA was fused immediately downstream of a genomic DNA segment containing nt −733 to +9 of the prt2 transcription unit (Fig. 3A). Because this plasmid generated vigorous acid phosphatase activity when introduced into a strain that was deleted for the entire prt2-pho84-prt-pho1 gene cluster (Fig. 3A), we surmised that the 733-nt segment embraces a prt2 promoter. To demarcate cis-acting elements, we serially truncated the 5′-flanking DNA to positions −429, −241, −134, −62, and −32 upstream of the prt2 transcription start site. The acid phosphatase activity of the plasmid-bearing [prt2-pho84-prt-pho1]Δ cells indicated that the 5′-flanking 62-nt segment sufficed for prt2 promoter-driven expression (Fig. 3A). Further truncation to −32 effaced acid phosphatase activity (Fig. 3A). Primer extension analysis using a pho1 antisense primer revealed correct initiation at the prt2 start site in the plasmid reporter and virtually equivalent levels of the prt2-driven pho1 mRNA from the −733, −241, and −62 promoters, but no detectable prt2-driven pho1 RNA from the −32 reporter strain (Fig. 3B).

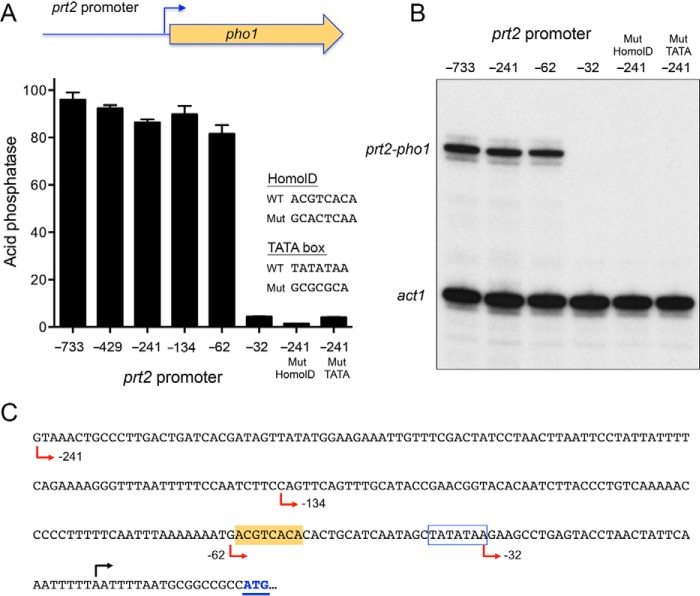

Figure 3.

Delineation of the prt2 promoter. A, plasmid reporter of prt2 promoter activity, wherein the pho1 ORF was fused to a genomic DNA segment containing nucleotides −733 (or truncated variants as indicated) to +9 of the prt2 transcription unit. Serial truncations of the upstream margin of the 5′-flanking prt2 DNA were made at −429, −241, −134, −62, and −32 relative to the prt2 transcription start site. The indicated mutations in the HomolD-like and TATA box elements were made in the context of the −241 prt2 promoter. The prt2·pho1 reporter plasmids were placed into [prt2-pho84-prt-pho1]Δ cells. Acid phosphatase activity in phosphate-replete cells was assayed and plotted in bar graph format. B, primer extension analysis of the prt2-driven pho1 transcript and act1 mRNA control was performed with total RNA isolated from cells bearing the indicated reporter plasmids. C, nucleotide sequence of the prt2 promoter reporter is shown from positions −241 to the ATG start codon of the pho1 ORF. The pho1 ATG start codon is in blue and underlined. The prt2 transcription start site is indicated by black arrow above the DNA sequence. Margins of promoter truncations are indicated by red arrows below the DNA sequence. A putative TATA element is outlined by a blue box. A putative HomolD-like element is shaded gold.

HomolD-like and TATA boxes are essential for prt2 promoter activity

The 241-nt DNA segment flanking the prt2 start site is shown in Fig. 3C. The promoter deletion analysis suggested the presence of essential transcriptional elements between −62 and −32. Our inspection of this segment disclosed a potential HomolD-like box (shaded yellow in Fig. 3C). The consensus HomolD element 5′-CAGTCAC(A/G) functions as a pol II promoter signal in fission yeast genes encoding ribosomal proteins (19–21) and in the prt and nc-tgp1 lncRNA genes that control phosphate homeostasis (6, 8). The prt2 HomolD-like sequence (−61ACGTCACA−54) deviates by two nucleobases from the consensus. The prt2 promoter also contains a TATA box sequence −38TATATAA−32. To query the role of the HomolD and TATA elements in prt2 function, we introduced a HomolD mutant (GCACTCAA) or a TATA mutant (GCGCGCA) into the −241 prt2·pho1 reporter. Both mutations effaced acid phosphatase activity (Fig. 3A) and expression of the prt2·pho1 reporter RNA (Fig. 3B). Thus, the prt2 lncRNA promoter shares the bi-partite HomolD/TATA architecture of the prt and nc-tgp1 lncRNA genes.

Plasmid-based reporter to study expression of pho84

As depicted in Fig. 4A, we isolated a fragment of the prt2-pho84 locus, spanning from 1800 nt upstream of the pho84 transcription initiation site (and encompassing the prt2 promoter) to 151 nt downstream of the pho84 transcription start site (representing the complete 5′-UTR of the pho84 mRNA) and fused it to the pho1 ORF and its native 3′-flanking DNA. To gauge the impact of upstream prt2 activity on the downstream pho84 promoter, we introduced the prt2 promoter-inactivating HomolD and TATA box mutations into the −1800 prt2-pho84·pho1 reporter. We also deleted the prt2 promoter by truncating the upstream margin to −1545 relative to the pho84 transcription start site (Fig. 4A). The reporter plasmids were introduced into [prt2-pho84-prt-pho1]Δ cells, and Pho1 acid phosphatase activity was measured under phosphate-replete conditions. The basal level of Pho1 expression from the −1800 reporter was increased 2-fold by deletion of the prt2 promoter (as in the −1545 construct) or by mutations of the HomolD or TATA boxes in the context of the −1800 reporter (Fig. 4B). We surmise that the prt2-pho84·pho1 reporter recapitulates prt2 lncRNA repression of transcription from the pho84 promoter.

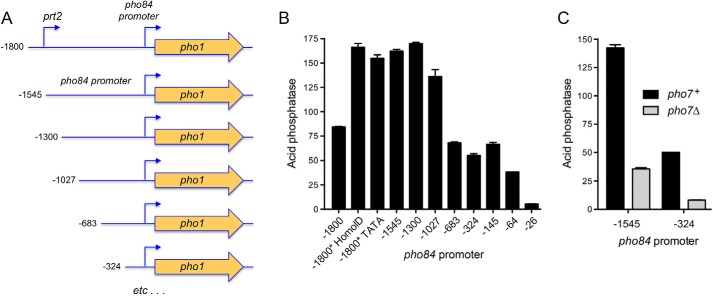

Figure 4.

Demarcation of the pho84 promoter. A, plasmid reporters of pho84 promoter, in which the pho1 ORF was fused to a genomic DNA segment containing nucleotides −1800 (or truncated variants as indicated) to +151 of the pho84 transcription unit. The −1800 construct includes the prt2 promoter; prt2 HomolD and TATA box mutations (as per Fig. 3) were made in the context of the −1800 pho84·pho1 reporter plasmid. B, acid phosphatase activity of [prt2-pho84-prt-pho1]Δ cells bearing the indicated pho84 promoter reporter plasmids. C, acid phosphatase activity of pho7+ and pho7Δ cells bearing the −1545 or −324 pho84 promoter reporters.

To further define the pho84 promoter, we serially truncated the 5′ margins of the pho84·pho1 reporter constructs to positions −1300, −1027, −683, −324, −145, −64, and −26 upstream of the pho84 transcription start site (Fig. 4A). High Pho1 activity was maintained for the −1545, −1300, and −1027 promoters, followed by a step down to intermediate Pho1 activity for the −683, −324, and −145 promoters (i.e. activity of the −683 and −145 reporters was 41% of the −1545 construct) (Fig. 4B). Truncations to −64 and −26 reduced Pho1 expression to 23 and 3% of the −1545 reporter, respectively. The essential segment between −64 and −26 includes a TATA box (−33TATATATA−26).

In light of the RNA analyses suggesting that pho84 expression is incompletely reliant on Pho7 (Fig. 2B), we compared Pho1 activity driven by the −1545 and −324 pho84 promoters in pho7+ and pho7Δ strain backgrounds. Absent Pho7, the −1545 and −324 promoters were 25 and 16% as active as in the presence of Pho7 (Fig. 4C). The residual Pho7-independent activity of the pho84 promoter echoes that of the tgp1 promoter, i.e. acid phosphatase activity driven by the tgp1 promoter was reduced by 85% in a pho7Δ strain background (10).

Pho7-binding sites in the pho84 promoter

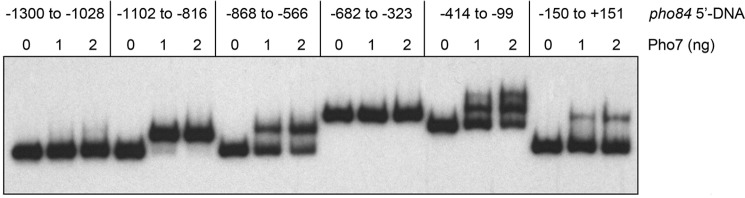

To locate Pho7 site(s), a series of overlapping 32P-labeled DNA fragments spanning the genomic region from nt −1300 to +151 relative to the pho84 transcription start site was prepared and tested by EMSA for binding to purified recombinant Pho7-DBD (DNA-binding domain; amino acids 279–368) (10). Whereas there was no protein-DNA complex formed on a DNA fragment spanning from −1300 to −1028, the DNA fragment from −1102 to −816 was bound by Pho7-DBD to form a single protein–DNA complex of slower electrophoretic mobility (Fig. 5). Pho7-DBD also formed a single protein–DNA complex on DNA fragments from −868 to −566 and −150 to +151, albeit with lower affinity than for the −1102 to −816 fragment, as gauged by the amount of shifted complex formed as a function of input Pho7-DBD (Fig. 5). The DNA segment from −414 to −99 formed two sequentially shifted complexes with Pho7-DBD, again with lower apparent affinity than the −1102 to −816 fragment (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Pho7-binding sites in the pho84 promoter. EMSAs using 32P-labeled DNA fragments embracing the indicated sequences upstream of the pho84 transcription start site (defined as +1). The nucleotide margins of the DNA segments are indicated at the top. Reaction mixtures (10 μl) containing 0.05 pmol of labeled DNA, 340 ng of poly(dI-dC), and 0–2 ng of Pho7-DBD were incubated for 10 min at room temperature. The mixtures were analyzed by native PAGE. An autoradiograph of the gel is shown.

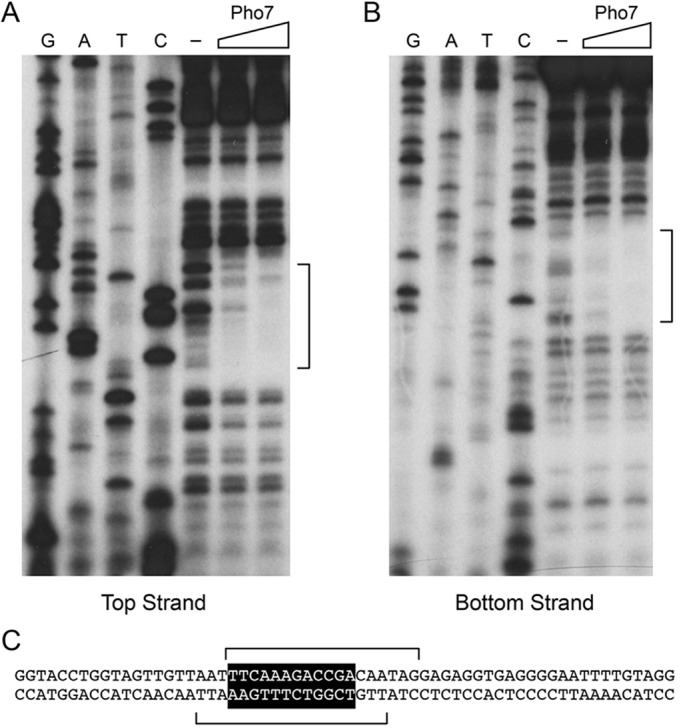

To map the high-affinity site within the −1102 to −816 segment, we conducted DNase I footprinting experiments. Initial tests using the entire 287-nt fragment located a single region of protection from DNase I between approximately −995 and −962 (data not shown). To better resolve the footprint margins, we exploited a shorter DNA probe, from nt −1039 to −907, that was 5′ 32P-labeled on the top strand or the bottom strand. A single region of protection from DNase I cleavage spanned nt −988 to −971 on the top strand (Fig. 6A) and nt −974 to −991 on the bottom strand (Fig. 6B). The footprint is denoted by brackets over the DNA sequence in Fig. 6C, and it embraces a 12-mer sequence 5′-(−977TCGGTCTTTGAA−988) (on the bottom strand) that is identical at 8/12 positions to Pho7-binding “site 2” in the pho1 promoter (5′-TCGGAAATTAAA) and at 9/12 positions to the Pho7-binding “site 1” in the pho1 promoter (5′-TCGCTGCTTGAA). It is worth noting that the Pho7-binding motif that we define here in the pho84 promoter is on the bottom DNA strand and oriented away from the pho84 transcription unit, whereas the two Pho7 sites in the pho1 promoter are spaced closely on the top DNA strand and oriented toward the pho1 transcription unit (10).

Figure 6.

Footprinting of a high-affinity Pho7 site in the pho84 promoter. DNase I footprinting analyses of the top strand (A) and bottom strand (B) of the pho84 promoter fragment from −1039 to −907 nt upstream of the transcription start site are shown along with the respective sequencing ladders. Binding reaction mixtures contained 0.25 pmol of 5′ 32P-labeled DNA and either no added Pho7-DBD (lanes −) or increasing amounts of Pho7-DBD (5 or 10 ng). The margins of the footprints are indicated by brackets. DNA sequence from −1008 to −947 upstream of the pho84 transcription start site is shown in C. The Pho7-binding motif is shown in white font on black background. The brackets denote the DNase I footprints on the top and bottom strands.

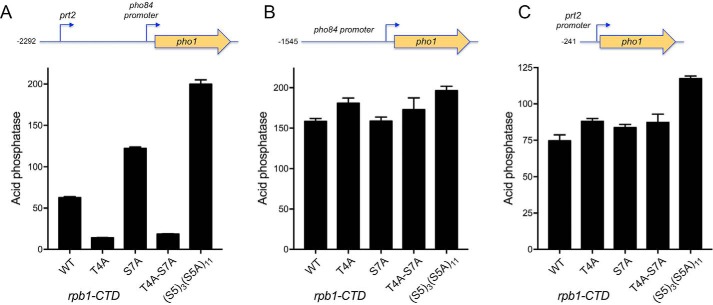

Effect of CTD phospho-site mutations on prt2 regulated pho84 expression

Previous studies had shown that repression of pho1 expression from the prt-pho1 locus (in either chromosomal or plasmid contexts) in phosphate-replete cells is affected by pol II CTD phosphorylation status, as gauged by the impact of CTD mutations that eliminate particular phosphorylation marks (5, 6, 22). For example, the inability to place a Ser7-PO4 mark in S7A cells de-repressed pho1. Limiting the number of serine 5 CTD sites to three consecutive Ser5-containing CTD heptads also de-repressed pho1. By contrast, the inability to place a Thr4-PO4 mark in T4A cells hyper-repressed pho1 under phosphate-replete conditions. Here, to test the impact of these CTD mutations on prt2-regulated pho84 promoter-driven gene expression, we introduced a −2292 prt2-pho84·pho1 reporter plasmid (Fig. 7A) into [prt2-pho84-prt-pho1]Δ cells in which the rpb1 chromosomal locus was replaced by alleles rpb1-CTD-WT, -CTD-T4A, -CTD-S7A, -CTD-T4A·S7A, or -CTD-S53S5A11 (23, 24). Whereas the T4A allele hyper-repressed Pho1 expression by 4-fold in phosphate-replete cells, the S7A and S53S5A11 CTD variants elicited 2- and 3-fold increases in activity compared with the rpb1-CTD-WT (Fig. 7A). The de-repression of the prt2-pho84·pho1 reporter by S7A was eliminated in a rpb1-CTD-T4A·S7A strain in which acid phosphatase activity was instead hyper-repressed, thereby phenocopying the T4A single mutant (Fig. 7A).

Figure 7.

Effect of CTD phospho-site mutations on prt2-regulated pho84 expression and individual prt2 and pho84 promoter activities. [prt2-pho84-prt-pho1]Δ rpb1-CTD strains with wildtype or mutated heptad arrays as specified were transformed with reporter plasmids prt2-pho84·pho1 (A), pho84·pho1 (B), or prt2·pho1 (C) and assayed for acid phosphatase activity.

prt2 and pho84 promoter activities are not affected by pol II CTD mutations

To query whether CTD mutations influence prt2 promoter-driven transcription, we introduced the −241 prt2·pho1 reporter plasmid into the [prt2-pho84-prt-pho1]Δ rpb1-CTD strains and measured acid phosphatase expression (Fig. 7C). prt2-promoted Pho1 activity was similar in the WT, T4A, S7A, and T4A·S7A strains and was 50% higher in the S53S5A11 strain. From these results, we conclude the following: (i) the de-repression of the prt2-pho84·pho1 reporter in S7A and S53S5A11 cells (Fig. 7A) was not caused by a decrease in transcription from the prt2 lncRNA promoter; and (ii) hyper-repression of the prt2-pho84·pho1 reporter in T4A and T4A·S7A cells (Fig. 7A) was not caused by an increase in transcription from the prt2 lncRNA promoter.

To interrogate the pho84 promoter, we placed the −1545 pho84·pho1 reporter plasmid in the [prt2-pho84-prt-pho1]Δ rpb1-CTD strains and measured acid phosphatase activity (Fig. 7B), which was similar in the WT, T4A, S7A, T4A·S7A, and S53S5A11 backgrounds. Thus, the de-repression or hyper-repression of the prt2-pho84·pho1 reporter by the CTD phospho-site mutant is not reflective of increased or decreased activity of the pho84 promoter per se.

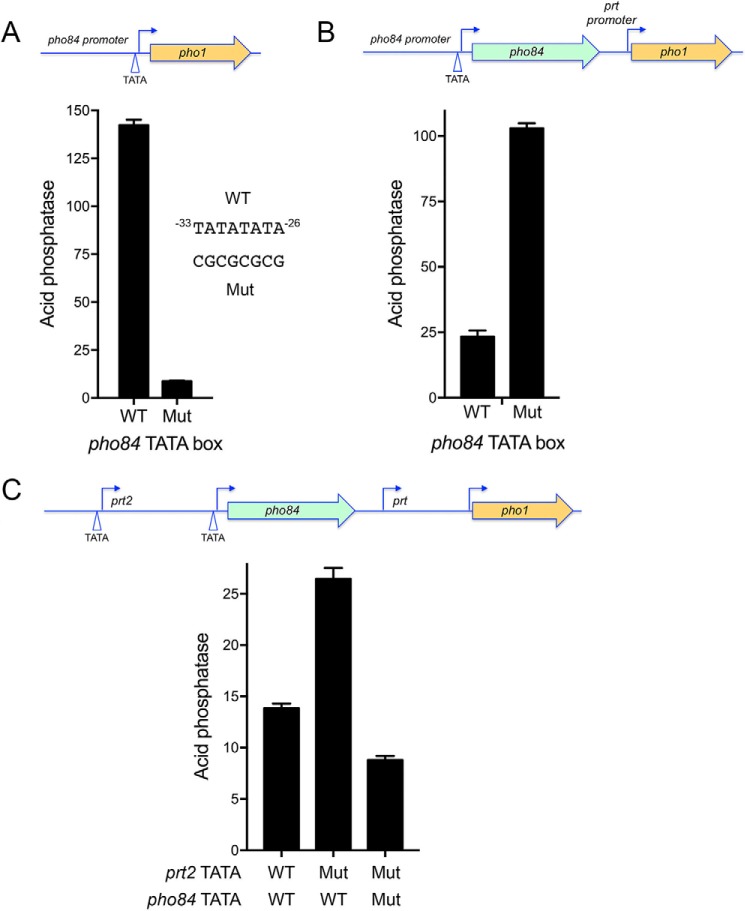

Fleshing out the cascade model for prt2 action at a distance on the pho1 promoter

The cascade effect of perturbing prt2 on the downstream pho84, prt, and pho1 transcription units suggested by the prt2-Δ experiments (Fig. 2) is amenable to further testing in light of the implementation of reporter assays and initial functional mapping of the prt2 and pho84 promoters. For example, having defined a mutation of the prt2 TATA box that eliminates prt2 transcription (Fig. 3), we introduced the prt2 TATA mutation into a prt2-pho84-prt-pho1 reporter plasmid that contains the complete 4-gene phosphate regulon (Fig. 8C), thereby allowing us to gauge prt2 long-range action on pho1 expression via assay of acid phosphatase activity. We found that the prt2 TATA mutation elicited a 2-fold increase in pho1 expression (Fig. 8C). Whereas this effect of prt2 TATA mutation on the pho1 gene correlated nicely with the 2-fold increase it exerts on the activity of the pho84 promoter (Fig. 4B), we thought it important to test whether intervening pho84 transcription is essential for prt2-TATA's effect on pho1. To do so, we needed to interdict pho84 transcription by inactivating its promoter. This was achieved by mutating the pho84 TATA box element −33TATATATA−26 to CGCGCGCG (Fig. 8A). The pho84 TATA mutation in the context of the −1545 pho84·pho1 reporter reduced pho84 promoter activity to 4% of the wildtype control (Fig. 8A). The salient finding was that the pho84 TATA mutation in the context of the prt2-pho84-prt-pho1 locus blocked the de-repression of pho1 expression elicited by the prt2 TATA mutation (Fig. 8C), thereby showing that pho84 transcription is necessary for the cascade effect.

Figure 8.

Testing a cascade model for prt2 action at a distance on the pho1 promoter. A, acid phosphatase activity expressed from a pho84·pho1 reporter in which the pho84 TATA box was either wildtype (WT) or mutated (Mut) as indicated. B, acid phosphatase activity expressed from a pho84-prt·pho1 reporter in which the pho84 TATA box was either wildtype or mutated. C, acid phosphatase activity expressed from a prt2-pho84-prt-pho1 reporter in which the prt2 and pho84 TATA boxes were either wildtype or mutated as specified.

A key missing link in the model is to establish whether pho84 transcription influences the activity of the flanking prt promoter. To address this issue, we employed a reporter in which the genomic DNA segment spanning the pho84 gene and the prt promoter was fused to the pho1 ORF (Fig. 8B). Into this construct, we introduced the pho84 TATA mutation. The instructive finding was that the prt promoter-driven acid phosphatase activity was increased 4-fold by the pho84 TATA mutation. This result affirms that pho84 transcription interferes with the downstream flanking prt promoter.

Discussion

Fission yeast phosphate homeostasis entails repressing the pho84, pho1, and tgp1 genes during phosphate-replete growth and inducing/de-repressing them under conditions of phosphate starvation. This study extends and consolidates a shared basis for repression of all three genes of the phosphate regulon, in which transcription of lncRNAs from the upstream prt2, prt, and nc-tgp1 genes interferes with the downstream pho84, pho1, and tgp1 promoters. The simplest model for interference is that pol II synthesizing the lncRNA displaces transcription factor Pho7 from its binding sites in the pho1, pho84, and tgp1 promoters that overlap the lncRNA transcription unit. In the case of nc-tgp1 repression of tgp1, the cleavage/poly(A) site of the nc-tgp1 lncRNA (5′-UCGGA↓) is located 187 nt upstream of the tgp1 transcription start site, exactly within the Pho7 DNA-binding site of the tgp1 promoter (5′-TCGGA↓CATTCAA) (8). The situation is different for prt2 and prt lncRNAs, for which the predominant species detected are a prt2-pho84 read-through RNA (Fig. 1) and a prt-pho1 read-through RNA (3, 4), respectively.

Here, we show that the bi-partite HomolD/TATA-box architecture described previously for the prt and nc-tgp1 promoters (6, 8) is also applicable to the prt2 promoter. We envision that this distinctive promoter arrangement somehow couples lncRNA transcription to phosphate availability, whereby the prt2, prt, and nc-tgp1 promoters are active in phosphate-replete cells and turned off in response to phosphate starvation. The mechanism of HomolD-dependent pol II transcription and its regulation are largely uncharted. Inositol polyphosphate IP7 is a signaling molecule that controls the level of pho1 and pho84 expression in phosphate-replete cells, such that IP7 phosphatase mutants unable to degrade IP7 are de-repressed and IP6 kinase mutants unable to synthesize IP7 are hyper-repressed (9, 25). Whether and how IP7 affects the synthesis of the phosphate-regulatory lncRNAs are unknown.

Our studies here of the effects of pol II CTD phospho-site mutations on prt2-responsive pho84 transcription echo previous findings for prt-pho1 and nc-tgp1-tgp1, viz. the pho84 promoter in the tandem prt2-pho84 array is de-repressed by S7A and S53S5A11, implicating the Ser5-PO4 and Ser7-PO4 marks as important for enforcement of the repressive status. The de-repressive CTD mutations do not affect the activity of the prt2 lncRNA or pho84 mRNA promoters per se, suggesting that they exert their effects via an increased propensity to terminate lncRNA synthesis prior to the Pho7 sites in the pho84 promoter, as invoked initially for prt-pho1 (6). As with prt-pho1, we see that CTD T4A mutation hyper-represses the pho84 promoter in the tandem prt2-pho84 array (conceivably by decreasing the lncRNA transcription termination) and that hyper-repression is maintained in a T4A/S7A double mutant. It is worth noting that S7A and T4A exert similar up and down effects on the PHO regulon in phosphate-replete cells as do the IP7 phosphatase and IP6 kinase mutants, raising the speculation that CTD-dependent transactions might be a target of IP7 signaling.

The tightly clustered arrangement of the prt2, pho84, prt, and pho1 transcription units in the fission yeast genome is intriguing, insofar as lncRNA genes alternate with mRNA genes in service of the same biological response pathway. Whereas studies here and previously show that the prt-pho1 and prt2-pho84 gene pairs are “autonomous” in their suppression of downstream mRNA synthesis by upstream lncRNA transcription under phosphate-replete conditions and their induction of mRNA synthesis during phosphate starvation, the experiments here highlight an unexpected (at least to us) facet of the four-gene cluster arrangement, whereby permutation of prt2 expression exerts a cascade effect on the downstream prt and pho1 loci. Specifically, the inactivation of prt2 lncRNA transcription, via deletion or mutation of the prt2 promoter (in the native chromosomal locus or on a reporter plasmid), elicits up-regulation of both pho84 and pho1. The interesting new wrinkle to this cascade effect is that transcription of an upstream mRNA gene (pho84) represses the expression of a downstream flanking lncRNA gene (prt), which is, in effect, a role reversal for mRNA transcription as the agent of repression by transcriptional interference rather than the target of such transcriptional interference.

Experimental procedures

Insertional inactivation of prt2

We constructed two prt2Δ cassettes, Δ1 and Δ2. The 5′- and 3′-flanking homology arms were cloned upstream and downstream of a hygromycin resistance gene (hygMX) in the pMJ696 vector. The 5′ homology flank of both cassettes extended from nt −733 to −218 upstream of the prt2 transcription start site. The 3′ homology arm of prt2Δ-1 extended from nt +15 to +532 downstream of the prt2 transcription start site. The 3′ homology arm of prt2Δ-2 extended from nt +533 to +1083. The prt2Δ-1 and prt2Δ-2 knock-out cassettes were excised from the plasmid and transformed into wildtype S. pombe diploids. Hygromycin-resistant diploids were checked by Southern blot analysis for a correct insertion-deletion event and subsequently sporulated on Malt plates to obtain hygromycin-resistant haploid prt2Δ-1 and prt2Δ-2 strains.

Deletion of the prt2-pho84-prt-pho1 gene cluster

The deletion of the entire prt2-pho84-prt-pho1 four-gene locus was constructed by cloning 5′ prt2-flanking and 3′ pho1-flanking homology arms upstream and downstream of hygMX in the pMJ696 vector. The 5′ homology flank extended from −733 to −218 nucleotides upstream of the prt2 transcription start site. The 3′ homology flank extended from nt +1336 to +2009 downstream of the pho1 start codon. The [prt2-pho84-prt-pho1]Δ cassette was excised from the plasmid and transformed into wildtype S. pombe diploids. Correct replacement of the prt2-pho84-prt-pho1 locus by the hygromycin-resistance marker was confirmed by Southern blot analysis, and the heterozygous diploid was sporulated to obtain hygromycin-resistant [prt2-pho84-prt-pho1]Δ haploids.

Reporter plasmids

We constructed five sets of pho1-based reporter plasmids, marked with a kanamycin-resistance gene (kanMX), in which the expression of Pho1 acid phosphatase was driven by either (i) a prt2(promoter) element (Fig. 3); (ii) a pho84(promoter) element (Fig. 4); (iii) a tandem prt2(promoter + lncRNA)–pho84(promoter) element (Fig. 4A); (iv) a tandem pho84(promoter + mRNA)–prt(promoter) element (Fig. 8B); or (v) a native prt2-pho84-prt-pho1 gene array (Fig. 8C). Plasmids i–iv are derivatives of pKAN-(pho1) described previously (6) that were generated by insertion of various genomic sequences flanking pho1, as specified under “Results” and figure legends. Serial truncations from the 5′ ends of the prt2 and pho84 promoters were made at the margins depicted in the figures. Nucleotide substitutions in HomolD or TATA promoter elements were made as depicted in the figures. The inserts of all plasmids were sequenced to exclude unwanted mutations.

Reporter assays

Reporter plasmids were transfected into [prt2-pho84-prt-pho1]Δ cells. kanMX transformants were selected on YES (yeast extract with supplements) agar medium containing 150 μg/ml G418. Single colonies of transformants (≥20) were pooled and grown at 30 °C in plasmid-selective liquid medium. To quantify acid phosphatase activity, reaction mixtures (200 μl) containing 100 mm sodium acetate, pH 4.2, 10 mm p-nitrophenyl phosphate, and cells (ranging from 0.005 to 0.1 A600 units) were incubated for 5 min at 30 °C. The reactions were quenched by adding 1 ml of 1 m sodium carbonate; the cells were removed by centrifugation, and the absorbance of the supernatant was measured at 410 nm. Acid phosphatase activity is expressed as the ratio of A410 (p-nitrophenol production) to A600 (cells). Each datum in the graphs is the average (±S.E.) of phosphatase assays using cells from at least three independent cultures.

RNA analyses

Total RNA was extracted via the hot phenol method from 15 A600 units of yeast cells that had been grown to mid log-phase (A600 of 0.3 to 0.8) at 30 °C in YES or YES + G418 (for selection of kanMX plasmids). RNA was also isolated from stationary phase cells grown in YES medium at 30 °C to A600 of 3.7. The RNAs were extracted serially with phenol/chloroform and chloroform, and then precipitated with ethanol. The RNAs were resuspended in 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 1 mm EDTA. For Northern blotting, equivalent amounts (15 μg) of total RNA were resolved by electrophoresis through a 1.2% agarose/formaldehyde gel. After photography under UV illumination to visualize ethidium bromide-stained 18S and 28S rRNAs, the gel contents were transferred to an Amersham Biosciences Hybond-XL membrane (GE Healthcare). [32P]dAMP-labeled hybridization probes were prepared by random-priming radiolabeling of DNA fragments of the pho84 gene (spanning nucleotides +916 to +1840 relative to pho84 transcription start site) or the prt2 gene (spanning nucleotides −1545 to −99 relative to pho84 transcription start site). Hybridization was performed as described (26), and the hybridized probes were visualized by autoradiography.

Aliquots (10 or 20 μg) of total RNA were used as templates for Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase-catalyzed extension of 5′ 32P-labeled oligodeoxynucleotide primers complementary to the pho84, pho1, or act1 mRNAs and the prt2 or prt lncRNAs. The primer extension reactions were performed as described previously (27), and the products were analyzed by electrophoresis of the reaction mixtures through a 22-cm 8% polyacrylamide gel containing 7 m urea in 80 mm Tris borate, 1.2 mm EDTA. The 32P-labeled primer extension products were visualized by autoradiography of the dried gel. The primer sequences were as follows: act1 5′-GATTTCTTCTTCCATGGTCTTGTC; pho1 5′-GTTGGCACAAACGACGGCC; pho84 5′-AATGAAGTCCGAATGCGGTTGC; prt2 5′-TCTCATCCTCTATGACTTATTTCG; and prt 5′-TTTGCATGCCTAGTTTTCCTTGAC. The primer for detection of the prt2 promoter-driven pho1 mRNA (in Fig. 3B) was 5′-GGAAGTCAAATGTTCCTTG.

To precisely map the 5′ end of the prt2 RNA, we used a 32P-labeled primer complementary to prt2 (5′-TAATTCTATCTCATCCTCTATGAC) for RT primer extension templated by total RNA isolated from wildtype or rrp6Δ cells. The RT products were then analyzed by electrophoresis through a 42-cm denaturing 8% polyacrylamide gel in parallel with a series of DNA-directed primer extension reactions (using the same labeled prt2 primer) that contained mixtures of standard and chain-terminating nucleotides, as described (17).

3′-RACE

To map the poly(A) site of the pho84 mRNA, we employed the 3′-RACE kit (Invitrogen). Total RNA was isolated from phosphate-replete cells and from cells harvested 6 h after transfer to phosphate-free medium. 2 μg of RNA was used as template for first strand cDNA synthesis by SuperScript II RT and an oligo(dT) adapter primer. The RNA template was removed by digestion with RNase H, and the cDNA was then diluted 10-fold for amplification by PCR using three different pho84-specific forward primers (5′-CTGTTGGCGTTGGTTGCTCG; 5′-CGTGGTACTGCTCATGG; and 5′-GATAGCAAGTGGAAGAGCTG) and an abridged universal reverse primer. The PCR products were gel-purified and cloned into a pCRII TOPO vector by using the TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen). Plasmid DNAs isolated from individual bacterial transformant colonies were sequenced. cDNAs were deemed to be “independent” when they contained different lengths of poly(dA) at the cloning junction.

DNA binding by EMSA

32P-Labeled DNA fragments were generated by PCR amplification of pho84 promoter segments using 5′ 32P-labeled forward primers (prepared with [γ-32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase and then separated from [γ-32P]ATP by Sephadex G-25 gel filtration) and non-labeled reverse primers. The PCR fragments were purified by electrophoresis through a native 8% polyacrylamide gel in 1× TBE buffer (80 mm Tris borate, 1.2 mm EDTA, 2.5% glycerol), eluted from an excised gel slice, ethanol-precipitated, and resuspended in 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1 mm EDTA at a concentration of 0.25 μm. EMSA reaction mixtures (10 μl) containing 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 10% glycerol, 340 ng of poly(dI-dC) (Sigma), 0.05 pmol of 32P-labeled DNA, and 2 μl of Pho7-DBD (purified as described in Ref. 10) and serially diluted in buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 250 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.1% Triton X-100) were incubated for 10 min at room temperature. The mixtures were analyzed by electrophoresis through a native 6% polyacrylamide gel containing 2.5% (v/v) glycerol in 0.25× TBE buffer. 32P-Labeled DNAs (free and Pho7-bound) were visualized by autoradiography.

DNase I footprinting

32P-Labeled DNA fragments of the pho84 promoter were generated by PCR amplification and purified as described above, using either a 5′ 32P-labeled forward primer and non-labeled reverse primer (to label the top strand) or a 5′ 32P-labeled reverse primer and non-labeled forward primer (to label the bottom strand). Footprinting reaction mixtures (10 μl) containing 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 10% glycerol, and 32P-labeled DNA and Pho7-DBD as specified were incubated for 10 min at room temperature. The mixtures were then adjusted to 2.5 mm MgCl2 and 0.5 mm CaCl2 and reacted with 0.01 units of DNase I (New England Biolabs) for 90 s at room temperature. The DNase I reaction was quenched by adding 200 μl of STOP solution (50 mm sodium acetate, pH 5.2, 1 mm EDTA, 0.1% SDS, 30 μg/ml yeast tRNA). The mixture was phenol/chloroform-extracted, ethanol-precipitated, and resuspended in 90% formamide, 50 mm EDTA. The samples were heated at 95 °C and then analyzed by urea-PAGE. 32P-Labeled DNAs were visualized by autoradiography.

Author contributions

A. G., A. M. S., S. S., and B. S. conceptualization; A. G., A. M. S., S. S., and B. S. formal analysis; A. G., A. M. S., S. S., and B. S. investigation; A. G., A. M. S., S. S., and B. S. writing-review and editing; S. S. and B. S. supervision; S. S. and B. S. funding acquisition; S. S. writing-original draft; S. S. and B. S. project administration.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM52470 (to S. S. and B. S.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains Figs. S1 and S2.

Please note that the JBC is not responsible for the long-term archiving and maintenance of this site or any other third party hosted site.

- lncRNA

- long noncoding RNA

- nt

- nucleotide

- DBD

- DNA-binding domain

- CTD

- carboxyl-terminal domain

- pol

- polymerase

- PAS

- polyadenylation signal

- RACE

- rapid amplification of cDNA ends.

References

- 1. Tomar P., and Sinha H. (2014) Conservation of PHO pathway in ascomycetes and the role of Pho84. J. Biosci. 39, 525–536 10.1007/s12038-014-9435-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Carter-O'Connell I., Peel M. T., Wykoff D. D., and O'Shea E. K. (2012) Genome-wide characterization of the phosphate starvation response in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. BMC Genomics 13, 697 10.1186/1471-2164-13-697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lee N. N., Chalamcharla V. R., Reyes-Turcu F., Mehta S., Zofall M., Balachandran V., Dhakshnamoorthy J., Taneja N., Yamanaka S., Zhou M., and Grewal S. I. (2013) Mtr4-like protein coordinates nuclear RNA processing for heterochromatin assembly and for telomere maintenance. Cell 155, 1061–1074 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shah S., Wittmann S., Kilchert C., and Vasiljeva L. (2014) lncRNA recruits RNAi and the exosome to dynamically regulate pho1 expression in response to phosphate levels in fission yeast. Genes Dev. 28, 231–244 10.1101/gad.230177.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schwer B., Sanchez A. M., and Shuman S. (2015) RNA polymerase II CTD phospho-sites Ser5 and Ser7 govern phosphate homeostasis in fission yeast. RNA 21, 1770–1780 10.1261/rna.052555.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chatterjee D., Sanchez A. M., Goldgur Y., Shuman S., and Schwer B. (2016) Transcription of lncRNAprt, clustered prt RNA sites for Mmi1 binding, and RNA polymerase II CTD phospho-sites govern the repression of pho1 gene expression under phosphate-replete conditions in fission yeast. RNA 22, 1011–1025 10.1261/rna.056515.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ard R., Tong P., and Allshire R. C. (2014) Long non-coding RNA-mediate transcriptional interference of a permease gene confers drug tolerance in fission yeast. Nat. Commun. 5, 5576 10.1038/ncomms6576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sanchez A. M., Shuman S., and Schwer B. (2018) Poly(A) site choice and pol II CTD Serine-5 status govern lncRNA control of phosphate-responsive tgp1 gene expression in fission yeast. RNA 24, 237–250 10.1261/rna.063966.117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Henry T. C., Power J. E., Kerwin C. L., Mohammed A., Weissman J. S., Cameron D. M., and Wykoff D. D. (2011) Systematic screen of Schizosaccharomyces pombe deletion collection uncovers parallel evolution of the phosphate signal pathways in yeasts. Eukaryot. Cell 10, 198–206 10.1128/EC.00216-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schwer B., Sanchez A. M., Garg A., Chatterjee D., and Shuman S. (2017) Defining the DNA binding site recognized by the fission yeast Zn2Cys6 transcription factor Pho7 and its role in phosphate homeostasis. mBio 8, e01218–17 10.1128/mBio.01218-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rhind N., Chen Z., Yassour M., Thompson D. A., Haas B. J., Habib N., Wapinski I., Roy S., Lin M. F., Heiman D. I., Young S. K., Furuya K., Guo Y., Pidoux A., Chen H. M., et al. (2011) Comparative functional genomics of the fission yeasts. Science 332, 930–936 10.1126/science.1203357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gunaratne J., Schmidt A., Quandt A., Neo S. P., Saraç O. S., Gracia T., Loguercio S., Ahrné E., Xia R. L., Tan K. H., Lössner C., Bähler J., Beyer A., Blackstock W., and Aebersold R. (2013) Extensive mass spectrometry-based analysis of the fission yeast proteome. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 12, 1741–1751 10.1074/mcp.M112.023754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Carpy A., Krug K., Graf S., Koch A., Popic S., Hauf S., and Macek B. (2014) Absolute proteome and phosphoproteome dynamics during the cell cycle of Schizosaccharomyces pombe (fission yeast). Mol. Cell. Proteomics 13, 1925–1936 10.1074/mcp.M113.035824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lemay J. F., Larochelle M., Marguerat S., Atkinson S., Bähler J., and Bachand F. (2014) The RNA exosome promotes transcription termination of backtracked RNA polymerase II. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 21, 919–926 10.1038/nsmb.2893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chalamcharla V. R., Folco H. D., Dhakshnamoorthy J., and Grewal S. I. (2015) Conserved factor Dhp1/Rat1/Xrn2 triggers premature transcription termination and nucleates heterochromatin to promote gene silencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 15548–15555 10.1073/pnas.1522127112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Touat-Todeschini L., Shichino Y., Dangin M., Thierry-Mieg N., Gilquin B., Hiriart E., Sachidanandam R., Lambert E., Brettschneider J., Reuter M., Kadlec J., Pillai R., Yamashita A., Yamamoto M., and Verdel A. (2017) Selective termination of lncRNA transcription promotes heterochromatin silencing and cell differentiation. EMBO J. 36, 2626–2641 10.15252/embj.201796571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mata J. (2013) Genome-wide mapping of polyadenylation sites in fission yeast reveals widespread alternative polyadenylation. RNA Biol. 10, 1407–1414 10.4161/rna.25758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Loya T. J., and Reines D. (2016) Recent advances in understanding transcription termination by RNA polymerase II. F1000Res. 2016 5, 1478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Witt I., Straub N., Käufer N. F., and Gross T. (1993) The CAGTCACA box in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe functions like a TATA element and binds a novel factor. EMBO J. 12, 1201–1208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Witt I., Kwart M., Gross T., and Käufer N. F. (1995) The tandem repeat AGGGTAGGGT is, in the fission yeast, a proximal activation sequence and activates basal transcription mediate by the sequence TGTGACTG. Nucleic Acids Res. 23, 4296–4302 10.1093/nar/23.21.4296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gross T., and Käufer N. F. (1998) Cytoplasmic ribosomal protein genes of the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe display a unique promoter type: a suggestion for nomenclature of cytoplasmic ribosomal proteins in databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 26, 3319–3322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schwer B., Bitton D. A., Sanchez A. M., Bähler J., and Shuman S. (2014) Individual letters of the RNA polymerase II CTD code govern distinct gene expression programs in fission yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 4185–4190 10.1073/pnas.1321842111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schwer B., and Shuman S. (2011) Deciphering the RNA polymerase II CTD code in fission yeast. Mol. Cell 43, 311–318 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.05.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schwer B., Sanchez A. M., and Shuman S. (2012) Punctuation and syntax of the RNA polymerase II CTD code in fission yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 18024–18029 10.1073/pnas.1208995109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Estill M., Kerwin-Iosue C. L., and Wykoff D. D. (2015) Dissection of the PHO pathway in Schizosaccharomyces pombe using epistasis and the alternate repressor adenine. Curr. Genet. 61, 175–183 10.1007/s00294-014-0466-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Herrick D., Parker R., and Jacobson A. (1990) Identification and comparison of stable and unstable RNAs in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10, 2269–2284 10.1128/MCB.10.5.2269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schwer B., Mao X., and Shuman S. (1998) Accelerated mRNA decay in conditional mutants of yeast mRNA capping enzyme. Nucleic Acids Res. 26, 2050–2057 10.1093/nar/26.9.2050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.