Abstract

Background

Ensuring appropriate cancer screenings among low-income persons with chronic conditions and persons residing in long-term care (LTC) facilities presents special challenges. This study examines the impact of having chronic diseases and of LTC residency status on cancer screening among adults enrolled in Medicaid, a joint state-federal government program providing health insurance for certain low-income individuals in the U.S.

Methods

We used 2000–2003 Medicaid data for Medicaid-only beneficiaries and merged 2003 Medicare-Medicaid data for dually-eligible beneficiaries from four states to estimate the likelihood of cancer screening tests during a 12-month period. Multivariate regression models assessed the association of chronic conditions and LTC residency status with each type of cancer screening.

Results

LTC residency was associated with significant reductions in screening tests for both Medicaid-only and Medicare-Medicaid enrollees; particularly large reductions were observed for receipt of mammograms. Enrollees with multiple chronic comorbidities were more likely to receive colorectal and prostate cancer screenings and less likely to receive Papanicolaou (Pap) tests than were those without chronic conditions.

Conclusions

LTC residents have substantial risks of not receiving cancer screening tests. Not performing appropriate screenings may increase the risk of delayed/missed diagnoses and could increase disparities; however, it is also important to consider recommendations to appropriately discontinue screening and decrease the risk of overdiagnosis. Although anecdotal reports suggest that patients with serious comorbidities may not receive regular cancer screening, we found that having chronic conditions increases the likelihood of certain screening tests. More work is needed to better understand these issues and to facilitate referrals for appropriate cancer screenings.

Keywords: Neoplasms, Medicaid, Mass Screening, Healthcare Disparities, Nursing Homes

INTRODUCTION

Ensuring appropriate receipt of cancer screens among low-income persons with chronic medical conditions and persons residing in long-term care (LTC) facilities presents special challenges. These populations may be at risk of both too few and too many screenings. For cancer screening, “overdiagnosis” refers to the detection of tumors that would have not developed into symptomatic disease during the screened individuals’ lifetimes [1]. This may result from continued cancer screening among individuals older than recommended ages. In contrast, underscreening reflects inadequate testing for cancer among individuals who could potentially benefit from early diagnosis. Previous reports have indicated that individuals with comorbidities are less likely to receive cancer screenings [2–4]. For individuals with chronic conditions, health care providers may focus on the most severe problems and may not address preventive care needs [5].

Health care providers treating patients in LTC environments may also be more likely to focus on day-to-day issues than on recommended cancer screenings. In surveys using hypothetical clinical case vignettes, physicians were significantly less likely to recommend mammography for women residing in nursing homes compared with those residing at home [6,7]. Although cancer screening may not be appropriate for some LTC residents based on remaining life expectancy, the expected benefit of early detection may be sufficiently large among other residents to justify routine screening.

Medicaid, a joint state-federal government program providing health insurance for certain low-income individuals in the U.S., pays for medical care for a substantial proportion of the U.S. population. Individuals enrolled in Medicaid, compared with those having private insurance, receive less cancer screening and thus are already potentially at risk for delayed cancer diagnosis [8]. For this study, we analyzed claims data from Medicaid enrollees to assess the association of chronic conditions and LTC residence with receipt of cancer screening services.

METHODS

Data Sources

For this study, we used Medicaid Analytic eXtract (MAX) data for four states: Georgia, Illinois, Louisiana, and Maine. MAX is a uniform Medicaid enrollment, utilization, and payment dataset created by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) [9]. Both individuals with Medicaid coverage only and dually-eligible Medicaid-Medicare enrollees were included in the study populations. Analyses of the Medicaid-only population used 2000–2003 MAX data, which were the most current years available when the study began. Analyses of the dual-eligible Medicare-Medicaid population used 2003 MAX data merged with 2003 Medicare claims and enrollment data. The study protocol was approved by RTI International’s Institutional Review Board and the CMS Privacy Review Board.

Study Population

The study population included adult Medicaid beneficiaries in the four study states who were age- and sex-eligible for the cancer screening tests. Only Medicaid enrollees in fee-for-service programs were included in the study population; those in Medicaid managed-care programs were excluded due to incomplete claims data. Dually-eligible enrollees were identified using MAX variables that indicate the presence of Medicare claims, enrollment, or eligibility records for a Medicaid enrollee. The age- and sex-eligibility requirements for the cancer screening tests used in this study were:

Mammography: female, age 40 and older;

Papanicolaou (Pap) test: female, age 21 and older;

Colorectal cancer (CRC) screening: age 50 and older; and

Prostate cancer screening: male, age 50 and older.

Each observation in the analysis represented a period of up to 12 months of Medicaid coverage. For dually-eligible beneficiaries, the observation corresponded to the calendar year 2003. Medicaid-only beneficiaries, for whom we had up to four years of data, could have multiple observations in the study data beginning with the first month of fee-for-service Medicaid enrollment in the data and continuing for up to 12 months. Use of 12 month observation periods decreases the likelihood that observed rates of cancer screening will be biased by differential length of Medicaid enrollment. It is important to note that these analyses examined the likelihood of receiving each type of cancer screening in an observation period, and did not assess concordance with guideline-recommended screening practices.

We excluded an observation if any of the following were true during the 12-month period:

the beneficiary was pregnant, observations excluded=578,078;

the beneficiary had cancer, observations excluded=141,025; or

the beneficiary had less than 4 months of fee-for-service enrollment, observations excluded=531,027.

We included part-year enrollees (with at least 4 months of enrollment) because they are a significant portion of the Medicaid population; excluding them could bias estimates if they differ systematically from full-year enrollees. Among dually-eligible beneficiaries and Medicaid-only beneficiaries included in our analyses, 21.1% and 37.3% (respectively) had less than 12 months of enrollment during an observation period.

This study population (Medicaid enrollees eligible to receive cancer screenings) was classified based on LTC residency status (yes/no) and number of serious comorbidities (0, 1, 2–3 or 4+). If an individual was eligible for a particular screening test, he/she was included in analyses of both LTC status and comorbidities.

Study Variables

The dependent variable in analyses indicated whether a beneficiary received an indicated cancer screening test during an observation period, based on having at least one claim with a procedure code for that test during the observation period. An individual was considered to have received CRC screening if they had a claim for barium enema, colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy, or fecal occult blood test (FOBT). An individual with a claim for either prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test or digital rectal exam (DRE) was considered to have received prostate cancer screening.

Analyses of chronic disease impacts compared individuals with 1, 2–3, and 4 or more of 16 selected chronic diseases to those with none of these diseases. The selected chronic diseases included: Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), renal failure, arthritis, hypertension, congestive heart failure, hepatitis, obesity, asthma, coronary heart disease (CHD), degenerative diseases of the central nervous system (CNS), depression, diabetes, mental retardation, organic psychoses, and stroke. Individuals were identified as having diseases based on claims with an International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis code (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd9cm.htm). Individuals with at least one inpatient or long-term care claim with an ICD-9-CM diagnosis were classified as having that disease. For other services (physician, hospital outpatient, clinic, laboratory, radiology, therapies, and home health), in order to avoid “rule out” claims, individual were required to have at least two claims on different dates with the diagnosis code.

Analyses of the impact of LTC residence on cancer screenings compared individuals with 0 days vs. those with 120 more or days of residence in a Medicaid-covered facility during an observation period. Individuals with 1–120 days of residence in a Medicaid-covered facility were excluded from the LTC study population because their service use is less likely to be influenced by LTC facility residence. The count of long-term care days was obtained from Medicaid LTC facility claims, including nursing facilities, intermediate care facilities for the mentally retarded, and mental hospitals for the aged. In each state, at least 85% of the long-term care facility claims were associated with nursing facilities.

Analytic Methods

Analyses used multivariate logistic regressions, controlling for age (expressed as a continuous variable), age squared, sex, race/ethnicity (Black, Hispanic, and other, with White omitted), metropolitan residence status, and state fixed effects for each observation period. Individuals with chronic diseases may see a doctor more frequently, which could increase the likelihood of receiving cancer screening tests. Chronic disease regressions therefore also controlled for the number of office visits (0, 1–3, 4–6, 7–9, 10 or more) identified by CPT codes 99201–99215. Office visits on the same date as a cancer screening test were not included in the count. The LTC regressions also controlled for number of chronic diseases.

Analyses were weighted by months of fee-for-service enrollment during the 12-month period. Standard errors in analyses of the Medicaid-only population were adjusted to account for multiple observations for the same individual. Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Table 1 presents characteristics for Medicaid coverage-only enrollees (i.e., non-dual enrollees) while Table 2 presents characteristics for dual Medicare/Medicaid enrollees. Among the Medicaid-only population, LTC residents were only 2.1% of the total study population, while LTC residents were almost 15% of the dually-eligible enrollees. The majority of Medicaid-only enrollees (61.8%) had no chronic conditions; only 3.5% had four or more chronic conditions. In contrast, 21.2% of Medicare-Medicaid enrollees had no chronic conditions while a similar proportion (20.1%) had four or more conditions.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Medicaid Only (Non-Dual) Enrollee Study Populationsa

| LTC Status | Chronic Condition Status by # of Chronic Conditions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LTC Resident | Non-LTC Resident | 0 | 1 | 2–3 | 4+ | ||

| N | 50,134 | 2,329,367 | 1,482,022 | 470,640 | 362,890 | 84,184 | |

| % of study population | 2.1 | 97.9 | 61.8 | 19.6 | 15.1 | 3.5 | |

| Age: mean (standard deviation) | 54.4 (15.6) | 40.2 (14.3) | 35.3 (12.7) | 44.3 (14.3) | 51.1 (12.8) | 54.5 (11.2) | |

| Sex (%) | |||||||

| Female | 65.8 | 89.8 | 93.0 | 87.1 | 80.8 | 76.7 | |

| Male | 34.2 | 10.2 | 7.0 | 12.9 | 19.3 | 23.3 | |

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | |||||||

| White | 54.1 | 41.7 | 41.9 | 43.0 | 40.8 | 42.6 | |

| Black | 39.3 | 46.9 | 47.7 | 45.5 | 45.5 | 44.3 | |

| Hispanic | 2.3 | 5.7 | 6.2 | 4.5 | 5.0 | 5.0 | |

| Other | 4.3 | 5.7 | 4.2 | 7.0 | 8.7 | 8.0 | |

| Number (%) of Study Population Eligible for Each Cancer Screening Test | |||||||

| CRC Screening, Any (N) | 35,670 | 599,864 | 198,404 | 169,143 | 217,026 | 61,620 | |

| % | 71.1% | 25.8% | 13.4% | 35.9% | 59.8% | 73.2% | |

| Mammography (N) | 24,484 | 758,285 | 297,680 | 213,988 | 224,215 | 57,117 | |

| % | 48.8% | 32.6% | 20.1% | 45.5% | 61.8% | 67.8% | |

| Pap Test (N) | 32,846 | 2,102,490 | 1,383,097 | 411,115 | 292,550 | 64,125 | |

| % | 65.5% | 90.3% | 93.3% | 87.4% | 80.6% | 76.2% | |

| Prostate Cancer Screening, Any (N) | 17,288 | 226,877 | 98,925 | 59,525 | 70,340 | 20,059 | |

| % | 34.5% | 9.7% | 6.7% | 12.6% | 19.4% | 23.8% | |

All differences between LTC and non-LTC residents and between enrollees with zero chronic conditions and those with 1, 2–3, or 4+ chronic conditions are statistically significant at p<0.0001.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Dual Medicare-Medicaid Enrollee Study Populationsa

| LTC Status | Chronic Condition Status by # of Chronic Conditions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LTC Resident | Non-LTC Resident | 0 | 1 | 2–3 | 4+ | ||

| N | 99,784 | 569,936 | 145,390 | 163,022 | 239,073 | 138,063 | |

| % of study population | 14.9 | 85.1 | 21.2 | 23.8 | 34.9 | 20.1 | |

| Age: Mean (standard deviation) | 78.3 (13.9) | 69.2 (14.5) | 67.4 (15.9) | 69.5 (15.3) | 71.6 (14.2) | 74.1 (13.0) | |

| Sex (%) | |||||||

| Female | 73.2 | 74.9 | 68.8 | 76.7 | 76.4 | 74.9 | |

| Male | 26.8 | 25.1 | 31.2 | 23.3 | 23.6 | 25.1 | |

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | |||||||

| White | 75.7 | 61.3 | 64.7 | 64.4 | 61.9 | 64.1 | |

| Black | 22.2 | 33.2 | 29.6 | 29.8 | 33.3 | 32.6 | |

| Hispanic | 0.6 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.3 | |

| Other | 1.5 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 4.2 | 3.3 | 2.0 | |

| Number (%) of Study Population Eligible for Each Cancer Screening Test | |||||||

| CRC Screening, Any (N) | 95,973 | 511,956 | 124,702 | 144,599 | 221,630 | 132,301 | |

| % | 96.2% | 89.8% | 85.8% | 88.7% | 92.7% | 95.8% | |

| Mammography (N) | 71,733 | 398,010 | 88,092 | 116,263 | 175,491 | 100,817 | |

| % | 71.9% | 69.8% | 60.6% | 71.3% | 73.4% | 73.0% | |

| Pap Test (N) | 73,014 | 424,321 | 99,454 | 124,609 | 181,898 | 102,512 | |

| % | 73.2% | 74.5% | 68.4% | 76.4% | 76.1% | 74.3% | |

| Prostate Cancer Screening, Any (N) | 26,770 | 145,615 | 45,936 | 38,413 | 57,175 | 35,551 | |

| % | 26.8% | 25.5% | 31.6% | 23.6% | 23.9% | 25.7% | |

All differences between LTC and non-LTC residents and between enrollees with zero chronic conditions and those with 1, 2–3, or 4+ chronic conditions are statistically significant at p<0.0001.

Among Medicaid-only enrollees, LTC residents and those with more chronic conditions were older and more likely to be male, although a majority of enrollees in all groups were female. Whites constituted approximately 40% of the non-LTC and chronic disease enrollees but more than half of the LTC enrollees. Table 1 also presents the proportion of Medicaid only enrollees in each LTC or chronic condition group who were eligible for the indicated cancer screening based on age and sex. Proportions ranged from approximately 7% of enrollees with no chronic conditions being eligible for prostate cancer screening to 93% of the same group (enrollees with no chronic conditions) being eligible for Pap tests. Among enrollees with chronic conditions, all chronic conditions except HIV were associated with increased likelihood of receiving any CRC screening. Enrollees with arthritis, asthma, CHD, depression, diabetes, hypertension, mental retardation, or obesity were more likely to receive mammograms. Enrollees with depression or HIV were more likely to receive Pap tests, while enrollees with arthritis, CHD, COPD, depression, diabetes, hypertension, or mental retardation were more likely to receive PSA tests (data not shown). All difference between LTC vs. non-LTC enrollees and for enrollees with zero versus 1, 2–3, or 4 or more chronic conditions are statistically significant at p<0.0001.

Similar relationships between demographic characteristics and LTC status or number of chronic conditions were observed among the dual Medicaid-Medicare enrollees (Table 2). Among dually-eligible individuals, LTC residents and those with more chronic conditions were older. The proportion of White enrollees among the dual population was greater than that among the Medicaid-only population, with more than three-quarters of LTC enrollees being White. The proportion of dually-eligible enrollees eligible for each screening test (based on age and sex) was greatest for CRC screening and least for prostate cancer screening. Among enrollees with chronic conditions, all chronic conditions except HIV, degenerative diseases of the CNS, organic psychoses, or stroke were associated with increased likelihood of receiving any CRC screening. Enrollees with asthma, HIV, or mental retardation were more likely to receive mammograms. Enrollees with asthma, depression, HIV, mental retardation, or obesity were more likely to receive Pap tests, while enrollees with arthritis, hypertension, or mental retardation were more likely to receive PSA tests (data not shown). All differences between LTC vs. non-LTC enrollees and for enrollees with zero versus 1, 2–3, or 4 or more chronic conditions are statistically significant at p<0.0001.

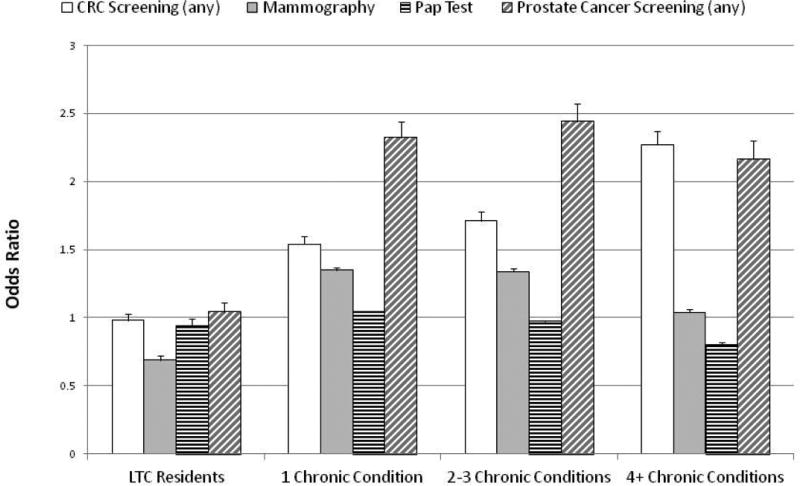

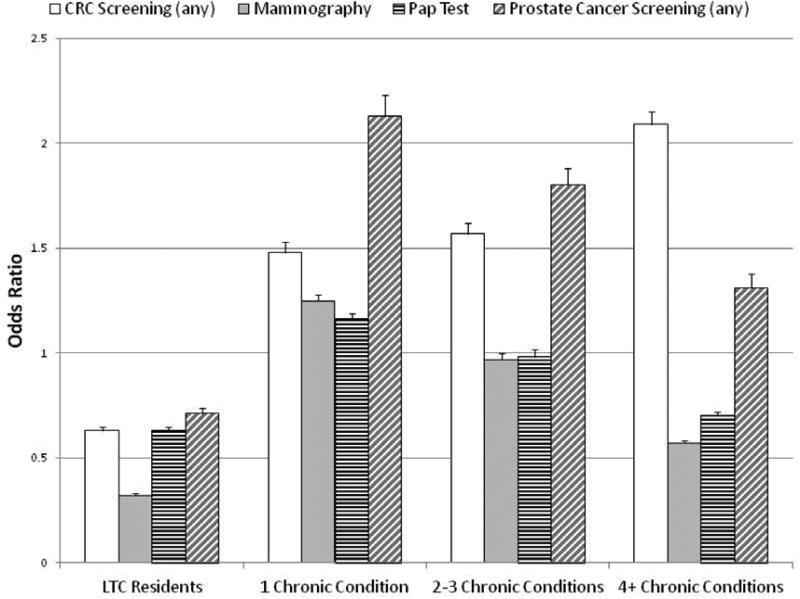

Figures 1 and 2 present results from multivariate logistic regression analyses of the rates of cancer screening tests among the study populations. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals are presented; as noted in the Methods sections, the odds ratios indicate the likelihood of receiving each screening test during an observation period of up to 12 months, not of receiving guideline-concordant cancer screenings. Odds ratios are determined with non-LTC residents as the reference group for the LTC study population and enrollees with zero chronic conditions as the reference group for the chronic condition study population.

Figure 1. Logistic Regression Analysis of Rates of Cancer Screening Tests for Medicaid Only (Non-Dual) Enrollees (Odds Ratios and Upper 95% Confidence Intervals).

Regression analyses controlled for age, age squared, sex, race/ethnicity, urban-rural residence status, state, number of chronic conditions (LTC study regressions only) and number of outpatient physician visits (chronic condition study regressions only). LTC regressions utilized non-LTC residents as the reference group; chronic condition regressions utilized individuals with zero chronic conditions as the reference group. All odds ratios are statistically significant at p<0.0001 except for CRC screening among LTC residents (not significant), Pap test among LTC residents (p=0.0006), prostate cancer screening among LTC residents (not significant) and mammography among enrollees with four or more chronic conditions (p=0.01).

Figure 2. Logistic Regression Analysis of Rates of Cancer Screening Tests for Dual Medicare-Medicaid Enrollees (Odds Ratios and Upper 95% Confidence Intervals).

Regression analyses controlled for age, age squared, sex, race/ethnicity, urban-rural residence status, state, number of chronic conditions (LTC study regressions only) and number of outpatient physician visits (chronic condition study regressions only). LTC regressions utilized non-LTC residents as the reference group; chronic condition regressions utilized individuals with zero chronic conditions as the reference group. All odds ratios are statistically significant at p<0.0001 except for mammography among enrollees with 2–3 chronic conditions (p=0.03) and Pap test among enrollees with 2–3 chronic conditions (not significant).

As illustrated in Figure 1, Medicaid-only LTC residents were significantly less likely to receive mammography or Pap tests than were non-LTC residents after controlling for the specified patient characteristics; no significant difference was observed for CRC and prostate cancer screening. Those with chronic conditions were significantly more likely to receive CRC screening, mammography, or prostate cancer screening. While the likelihood of receiving Pap tests was significantly (although only slightly) greater among Medicaid-only enrollees with one (vs. zero) chronic condition, Pap test rates were significantly lower among Medicaid-only enrollees with two or more chronic conditions.

Figure 2 presents the corresponding odds ratios for dual Medicare-Medicaid enrollees. Among this population, LTC residents were significantly less likely to receive all four cancer screenings compared with non-LTC residents. This reduction was especially large for mammography: dual LTC residents in this group had only one-third the likelihood of receiving mammography as did non-LTC residents. Similar to results for Medicaid-only enrollees, the likelihoods of CRC and prostate cancer screening among dual Medicaid-Medicare enrollees with chronic conditions were increased compared with those without chronic conditions. However, while dually-eligible enrollees with one chronic condition were also significantly more likely to receive mammography, those with two or more chronic conditions were significantly less likely to receive mammography. Similarly, dual enrollees with one chronic condition were more likely than those without chronic conditions to receive Pap tests, but those with 4 or more chronic conditions were significantly less likely to receive Pap tests.

DISCUSSION

This study assessed the association of LTC residency and multiple chronic conditions with the likelihood of receiving recommended cancer screening services among Medicaid enrollees. Our results indicated that all examined cancer screening tests are less likely to be performed among dual Medicaid-Medicare enrollees residing in long-term care facilities, while mammography and Pap tests are less likely to be performed among Medicaid-only enrollees in LTC facilities. Approximately 1.8 million individuals in the U.S. reside in nursing homes and the total number of nursing facility residents may increase in the future due to aging of the U.S. population. Ensuring appropriate cancer screening services among this large population presents additional challenges, due to their limited interactions with physicians and higher risk of developing certain types of cancer. For example, in a small study (95 individuals) of women age 75 and older residing in a skilled nursing facility, almost half (45%) of the performed mammograms involved abnormal findings that required clinical follow-up [10].

While underuse of screening may increase the risk of delayed or missed diagnoses, it is also important to consider the observed differences in cancer screening rates among LTC residents in the context of recommendations to appropriately discontinue screening. Welch & Black estimated that approximately 25% of breast cancers identified by mammography and 60% of prostate cancers detected by PSA may reflect overdiagnosis [1]. In addition, certain guidelines indicate that cancer screening may not always be indicated for individuals with short life expectancy. Previous reports have indicated that a substantial proportion of nursing home residents have relatively short life expectancies [11,12]. As such, lower rates of screening among certain LTC residents may be appropriate. Unfortunately, Medicaid claims data lack information on severity of comorbidities and life expectancy, so we were unable to control for these factors in our analyses.

However, not all individuals in LTC facilities have short life expectancies that might suggest appropriate discontinuation of cancer screening; Spillman & Lubitz estimated that among community residents age 65 and older who enter a nursing home, approximately 20% will spend five years or longer there [13]. In addition, Medicaid-enrolled nursing home residents may not receive appropriate cancer screening that could diagnose cancers at early stages. Bradley et al. reported that the majority (62%) of cancers among a Medicaid nursing home population were diagnosed with a SEER summary stage of distant or invasive but unknown [14]. A late stage or unstaged cancer diagnosis limits options for potentially curative treatment, particularly among those LTC residents who may have had longer life expectancies.

Further, appropriate cancer screening may lead to earlier diagnosis and therefore earlier initiation of needed supportive or palliative care for LTC residents with cancer [14]. Clement et al., examining Medicaid claims and tumor registry data for nursing home residents diagnosed with cancer after admission, found that 25% of these individuals were diagnosed at death or within one month of death [15]. With this late diagnosis, there was reduced opportunity for provision of palliative care. As early initiation of supportive/palliative care has been shown to decrease pain and improve quality of life among individuals diagnosed with cancer [16,17], Medicaid enrollees in long term care setting would likely benefit from earlier diagnosis.

Among the study population, the presence of chronic medical conditions was associated with mixed effects on the likelihood for cancer screening. We had expected that individuals with more comorbidities would be less likely to be screened for cancer. Some reports have indicated that individuals with severe comorbidities are less likely to receive cancer screenings [18,19]; however, other studies have reported mixed associations between comorbidities and screening [20–23].

There are a number of limitations associated with this study. Medicaid enrollees tend to have lower socioeconomic status than do individuals not enrolled in Medicaid, and include a higher proportion of individuals from racial/ethnic minority groups compared with the overall U.S. population. These factors may limit the generalizability of these results beyond the Medicaid population. In addition, the relatively short period of enrollment in Medicaid for many individuals, particularly non-duals, makes assessment of longitudinal patterns of medical care resource utilization (including cancer screening) difficult [24]. Our rates for certain cancer screening tests therefore almost certainly underestimate the actual proportion of enrollees receiving appropriate screening. However, this underestimate is likely to apply to all patient groups (i.e., LTC vs. non-LTC residents and individuals with varying numbers of chronic conditions) in a similar manner, as all screening rates are based on 12-month observation periods. Also, these analyses of receipt of a screening test during a 12-month period do not indicate whether guidelines for cancer screening were met, since guideline periods varied by screening test.

We were also unable to differentiate between cancer screening tests and similar procedures performed for other purposes (e.g., colonoscopies performed for evaluation of individuals with ulcerative colitis or similar conditions). However, since tests or procedures performed for the diagnosis of non-cancer conditions or for treatment purposes would likely have identified neoplastic lesions even if that was not their main purpose, inclusion of such tests is appropriate. It is also possible that patients received screening services not captured by the claims data. However, it is unlikely that a substantial proportion of Medicaid enrollees received cancer screening that was not covered by their state’s Medicaid (or in the case of dual enrollees, Medicare and Medicaid) program. We are also unable to determine whether missed cancer screening opportunities resulted in delayed or missed cancer diagnoses. Finally, the data used for this study are also at least eight years old; screening patterns may have changed in subsequent years.

Despite these limitations, this study provides important information related to cancer screening among a low socioeconomic status, underserved population. Given the significantly lower cancer screening rates among LTC residents, new interventions targeting patients, physicians, and LTC facility administrators are needed to highlight the importance of such screenings for appropriate individuals. Future efforts in these areas could involve both provider-level interventions, including training for health professionals in LTC environments on the importance of screenings among appropriate residents, and system-level interventions, such as reminders for screenings occurring automatically in electronic medical records and modification or expansion of mammography and colonoscopy facilities to facilitate screenings for LTC residents.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Lisa Richardson for her comments on this manuscript. This work was funded by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Welch HG, Black WC. Overdiagnosis in cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:605–13. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq099. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djq099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Castellano PZ, Wenger NK, Graves WL. Adherence to screening guidelines for breast and cervical cancer in postmenopausal women with coronary heart disease: an ancillary study of volunteers for hers. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2001;10:451–61. doi: 10.1089/152460901300233920. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/152460901300233920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heflin MT, Pollak KI, Kuchibhatla MN, Branch LG, Oddone EZ. The impact of health status on physicians' intentions to offer cancer screening to older women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:844–50. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.8.844. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/gerona/61.8.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McBean AM, Yu X. The underuse of screening services among elderly women with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1466–72. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2233. http://dx.doi.org/10.2337/dc06-2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaen CR, Stange KC, Nutting PA. Competing demands of primary care: a model for the delivery of clinical preventive services. J Fam Pract. 1994;38:166–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamblin JE. Physician recommendations for screening mammography: results of a survey using clinical vignettes. J Fam Pract. 1991;32:472–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marwill SL, Freund KM, Barry PP. Patient factors associated with breast cancer screening among older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:1210–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ward E, Halpern M, Schrag N, Cokkinides V, DeSantis C, Bandi P, et al. Association of insurance with cancer care utilization and outcomes. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:9–31. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0011. http://dx.doi.org/10.3322/CA.2007.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicaid Data Sources – General Information. Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2012. [cited 2013 January 25]. [monograph on the internet]. 2012 Available from http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Computer-Data-and-Systems/MedicaidDataSourcesGenInfo/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kerins G, Gruman C, Schwartz R, Rauch EA, Curry L, Fogel D. Mammography utilization in a skilled nursing facility. Conn Med. 2000;64:595–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wallace JB, Prevost SS. Two methods for predicting limited life expectancy in nursing homes. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2006;38:148–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2006.00092.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2006.00092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flacker JM, Kiely DK. Mortality-related factors and 1-year survival in nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:213–21. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51060.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spillman BC, Lubitz J. New estimates of lifetime nursing home use: have patterns of use changed? Med Care. 2002;40:965–75. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200210000-00013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005650-200210000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradley CJ, Clement JP, Lin C. Absence of cancer diagnosis and treatment in elderly Medicaid-insured nursing home residents. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:21–31. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm271. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djm271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clement JP, Bradley CJ, Lin C. Organizational characteristics and cancer care for nursing home residents. Health Serv Res. 2009;44:1983–2003. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.01024.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.01024.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bandieri E, Sichetti D, Romero M, Fanizza C, Belfiglio M, Buonaccorso L, et al. Impact of early access to a palliative/supportive care intervention on pain management in patients with cancer. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:2016–20. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds103. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mds103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kahi CJ, van Ryn M, Juliar B, Stuart JS, Imperiale TF. Provider recommendations for colorectal cancer screening in elderly veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:1263–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1110-x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11606-009-1110-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shokar NK, Nguyen-Oghalai T, Wu H. Factors associated with a physician's recommendation for colorectal cancer screening in a diverse population. Fam Med. 2009;41:427–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nosek MA, Howland CA. Breast and cervical cancer screening among women with physical disabilities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;78:S39–44. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(97)90220-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0003-9993(97)90220-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pirraglia PA, Sanyal P, Singer DE, Ferris TG. Depressive symptom burden as a barrier to screening for breast and cervical cancers. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2004;13:731–8. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2004.13.731. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2004.13.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lord O, Malone D, Mitchell AJ. Receipt of preventive medical care and medical screening for patients with mental illness: a comparative analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:519–43. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.04.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fisher DA, Galanko J, Dudley TK, Shahee NJ. Impact of comorbidity on colorectal cancer screening in the Veterans Healthcare System. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:991–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.04.010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2007.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Short PF, Graefe DR, Schoen C. Churn, Churn, Churn: How Instability of Health Insurance Shapes America’s Uninsured Problem. New York: The Commonwealth Fund; 2003. [cited 2013 January 25]. [monograph on the internet]. Available from http://www.allhealth.org/briefingmaterials/688Shortchurnchurnchurnhowinstabilityofhltinsuranceissuebrief-320.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]