Abstract

Introduction

Interpersonal violence affects millions of people worldwide, often has lifelong consequences, and is gaining recognition as an important global public health problem. There has been no assessment of measures countries are taking to address it. This report aims to assess such measures and provide a baseline against which to track future progress.

Methods

In each country, with help from a government-appointed National Data Coordinator, representatives from six to ten sectors completed a questionnaire before convening in a consensus meeting to decide on final country data; 133 of 194 (69%) WHO Member States participated. The questionnaire covered data, plans, prevention measures, and victim services. Data were collected between November 2012 and June 2014, and analyzed between June and October 2014. Global and country-level homicides for 2000–2012 were also calculated for all 194 Members.

Results

Worldwide, 475,000 people were homicide victims in 2012 and homicide rates declined by 16% from 2000 to 2012. Data on fatal and, in particular, non-fatal forms of violence are lacking in many countries. Each of the 18 types of surveyed prevention programs was reported to be implemented in a third of the 133 participating countries; each law was reported to exist in 80% of countries, but fully enforced in just 57%; and each victim service was reported to be in place in just more than half of the countries.

Conclusions

Although many countries have begun to tackle violence, serious gaps remain, and public health researchers have a critical role to play in addressing them.

Introduction

Interpersonal violence, which includes child maltreatment, youth violence, intimate partner violence, sexual violence, and elder abuse,1 is gaining recognition as an important global public health problem. This is largely due to its magnitude, far-reaching health consequences, and high costs to the health system and wider society. The Global Status Report on Violence Prevention 2014, published by WHO, the UN Development Programme, and the UN Office on Drugs and Crime, assesses, for the first time, national efforts to address interpersonal violence.2

Almost half a million people die every year of homicide, with rates in most low- and middle-income countries, particularly in Latin America and the Caribbean and Southern Africa, higher than in richer countries.3–7 Victims and perpetrators of homicide are disproportionately male (79% of victims and some 95% of perpetrators) and young (almost half of homicide victims are aged 15–29 years).7 One of the few existing recent estimates of global trends in homicide rates found that the homicide rate fell by 9.2% globally, by 47.9% in developed countries, and 3.1% in developing countries between 2000 and 2010.4

Though regarded as one of the most comparable and accurate indicators for measuring violence,1,7 homicides represent only a fraction of the health and social burden arising from violence. A quarter of adults report having been physically abused as children, one in five women and one in 13 men reports having been sexually abused as a child, and one in three women has been a victim of intimate partner violence at some point in her life.8–10

Interpersonal violence has serious and often lifelong consequences on mental and physical health, reproductive health, academic performance, and social functioning.11–16 Victims are at higher risk of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicidal behavior throughout their lives.10,15,17–21 Exposure to violence is strongly associated with high-risk behaviors such as alcohol and drug abuse and smoking, key risk factors for leading causes of death such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, liver disease, and other noncommunicable diseases.11,12 Exposure to violence in childhood—whether witnessing or experiencing violence in the home or community—increases the risk for later victimization and perpetration, including violence toward intimate partners and children.16,22–26

Violence thus places a heavy strain on health and criminal justice systems and social and welfare services.27 The cost of child maltreatment, for instance, has been estimated to be US$206 billion in the East Asia and Pacific region, or 1.9% of the region’s gross domestic product,28 and US$3.59 trillion globally, or 4.21% of the world’s gross domestic product.29

Interpersonal violence entered the global public health agenda in 1996 when the WHO adopted a resolution declaring violence a leading worldwide public health problem. As part of its core functions of monitoring and assessing health trends, WHO publishes global status reports, repeated every few years, on a variety of health issues, such as non-communicable diseases,30 alcohol and health,31,32 road safety,33,34 and, now, violence prevention.2 These aim to set baselines and monitor progress toward the achievement of the targets and the implementation of recommendations in WHO global plans of action and other documents. By identifying gaps in how the governments are addressing the health problem, these reports also help stimulate action at national, regional, and international levels.

The Global Status Report on Violence Prevention 2014 aims to evaluate the extent to which the recommendations of the 2002 World Report on Violence and Health1 (Appendix A, available online) are being implemented by assessing measures countries are taking to address violence. The report also includes homicide estimates for all 194 WHO Member States.

Methods

Study Sample

Countries were the units of analysis, and the study population was the 194 WHO Member States; 133 WHO Member States participated, for a response rate of 69%. These 133 countries cover 6.1 billion people or 88% of the world’s population. Response rates varied by WHO region and covered 63% of the population in the Eastern Mediterranean Region, 70% in the African Region, 83% in the European Region, 88% in the Region of the Americas, and 97% in the South-East Asian and Western Pacific Regions. Reasons countries did not participate include, for instance, that the Ministry of Health, WHO’s official counterpart in this project, did not nominate a National Data Coordinator (NDC) despite reminders; that the NDCs once nominated were unable to participate in one of the many offered training webinars; or that the country was in a state of war. Neither IRB approval nor informed consent was sought for this project as no data from human subjects were obtained.

Measures

The questionnaire covered four content areas:

data on homicide from vital statistics and police, and non-fatal interpersonal violence from population-based surveys;

national action plans, information exchange systems, and agencies/departments responsible for overseeing or coordinating violence prevention;

prevention policies, programs, and laws; and

health, social, and legal services for victims of violence.

Prevention programs and services included in the questionnaire were based on systematic reviews of the evidence and other guidance published by WHO and its partners.35–39 Appendix B (available online) provides details on the questionnaire.

Process

Data collection took place in five steps between November 2012 and June 2014. First, government-appointed NDCs in each country were trained through a series of webinars delivered in multiple languages. The training focused on a detailed examination of the content of the questionnaire and the process to be followed (identification of respondents, holding of consensus meeting, uploading of final data into online database). Second, within each country, a self-administered questionnaire was completed by respondents from ministries of health, justice, education, gender and women, law enforcement and police, children, social development and the interior, and, where relevant, nongovernmental organizations and research institutions. Respondents from the different sectors were identified by the NDCs based on their subject matter expertise and knowledge of violence prevention activities in the country, often in consultation with other parts of the government and with WHO Country and Regional Office staff. Third, these respondents held a consensus meeting and agreed on the final country submission best representing violence prevention programs, laws, and services in their country. Fourth, WHO staff validated the final submission for each country by checking the information against independent databases and other sources and sometimes suggested to NDCs that they take into account key studies that had been overlooked. Appendix C (available online) has more information on the databases that were used. Finally, permission to include the final data in the status report was obtained from country government officials. No countries refused permission.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics—such as proportion of countries implementing a particular policy, program, or victim service on a large scale or fully enforcing a law—were computed using SPSS, version 22.

To estimate homicide rates for the 194 WHO Member States,a countries were grouped into two main estimation categories. For countries with ≥8 years of data on homicide between 2000 and 2012, estimates were computed directly using either vital registration or police data based on decision rules developed on the basis of an in-depth analysis of the quality of homicide data from both sources. For countries without long time series of data, regression modeling was used to project national homicide rates, combining information on observed levels of homicide rates across regions and countries with covariates associated with levels of homicide (e.g., Gini index, infant mortality index, percentage of urban population). For each country, three main sources of homicide data were examined: data provided by countries from police and vital registration sources, data from the UN Office on Drugs and Crime’s global studies on homicide,6,7 and data from WHO’s Mortality Database.40

Results

Data on Fatal and Non-fatal Violence and National Action Plans

In 2012, some 475,000 people worldwide were victims of homicide, for an overall rate of 6.7 per 100,000 population. Rates in high-income countries (3.8 homicides per 100,000) were generally lower than rates in low- and middle-income countries (7.2 homicides per 100,000). Within low- and middle-income countries, the highest estimated rates occur in the Region of the Americas, with 28.5 homicides per 100,000 population, followed by the African Region with 10.9 homicides per 100,000 population. The lowest estimated rate of homicide is in the low- and middle-income countries of the Western Pacific Region, with 2.1 per 100,000 population.

Homicide is not distributed evenly among sex and age groups. Men and boys account for 82% of all homicide victims and have estimated rates of homicide that are more than four times those of women and girls (10.8 and 2.5, respectively, per 100,000). The highest estimated rates of homicide in the world are found among boys and men aged 15–29 years (18.2 per 100,000), followed closely by men aged 30–44 years (15.7 per 100,000). The disproportionate impact of homicide on youth is a consistent pattern across all levels of country income.

Globally, one in every two homicides is committed with a firearm, and one in four with a sharp instrument such as a knife, although the mechanism of homicide varies by region. Although firearms account for 75% of all homicides in the low- and middle-income countries of the Region of the Americas, they account for only 25% of homicides in the low- and middle-income countries of the European Region, where 37% of homicides involve sharp instruments.

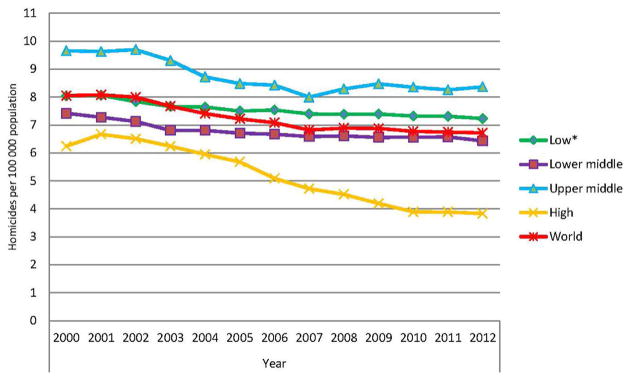

From 2000 to 2012, homicide rates declined by 16% globally (from 8.0 to 6.7 per 100,000 population), and in high-income countries by 39% (from 6.2 to 3.8 per 100,000 population). Homicide rates in low- and middle-income countries showed less decline: For both upper and lower middle–income countries, the estimated decline was 13%, and for low-income countries it was 10% (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Trends in estimated rates of homicide by country income status,* 2000–2012, world.

*Low–income: $1,025 or less; lower middle–income: $1,026 to $4,035; upper middle–income: $4,036 to $12,475; high–income: $12,476 or more (World Bank).

For the 133 countries participating in the report, gaps in the availability of homicide data from the two sources the report examined—police and civil or vital registration data—were identified. Some 12% of countries report lacking homicide data from police sources, 60% did not have usable homicide data from civil or vital registration sources, and 9% report having neither.

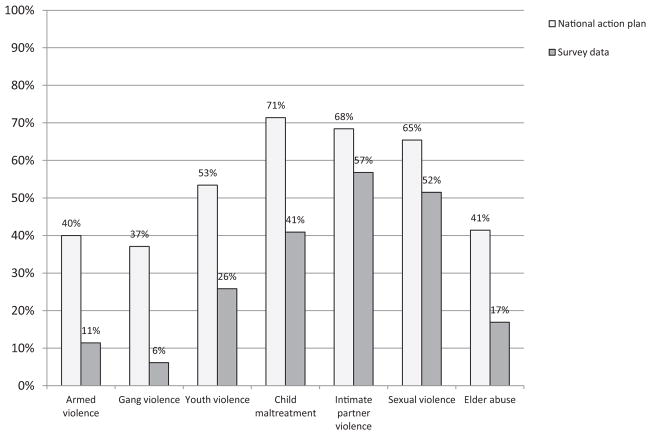

Differing survey methods and case definitions precluded comparisons of prevalence rates for the different types of non-fatal violence across countries. Less than half of countries reported having conducted nationally representative population-based surveys on most types of non-fatal violence, and many more countries reported that they had plans of action to reduce violence than population-based prevalence surveys (Figure 2). This suggests that national planning and policymaking is often being carried out without nationally representative data that provide a full perspective on the prevalence of violence.

Figure 2.

Proportion of countries with national survey data and national action plans, by type of violence (n=133 countries).

Prevention Programs, Policies, and Laws

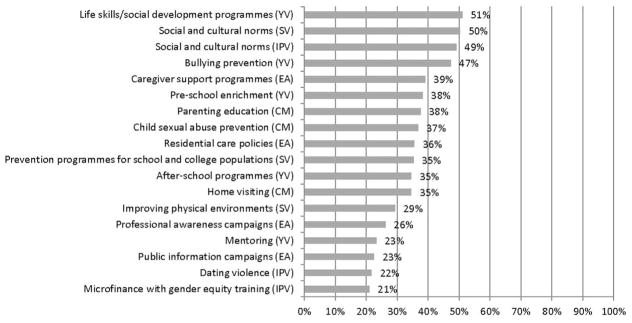

On average, each of the 18 types of surveyed prevention programs was reported to be implemented on a large scale in about a third of the countries (Figure 3). Life skills training and bullying prevention to address youth violence and social and cultural norm change strategies to address intimate partner violence and sexual violence were the strategies most commonly reported by countries.

Figure 3.

Proportion of countries implementing violence prevention programs on a large scale by type of program (n=133 countries).

Note: Although each program is shown as relevant to a particular type of violence, some of the programs listed in the figure have shown preventive effects on several types of violence.

CM, child maltreatment; EA, elder abuse; IPV, intimate partner violence; SV, sexual violence; YV, youth violence.

About 40% of countries reported having national policies providing incentives for youth at risk of violence to complete secondary schools and less than a quarter as having policies to prevent violence by reducing concentrations of poverty. Most countries report laws that reduce harmful alcohol use and nearly all countries have measures in place to regulate access to firearms, although the laws themselves and the populations covered vary widely.

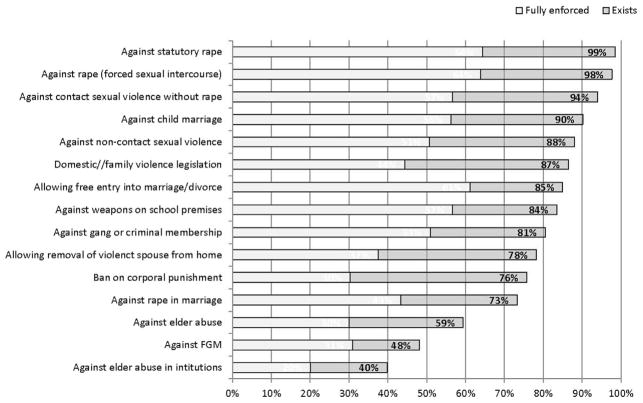

On average, the surveyed laws were reported to exist by 80% of countries, but to be fully enforced by just 57%. The biggest gaps between the existence and enforcement of laws related to bans on corporal punishment and to domestic/family violence legislation (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Proportion of countries with laws to prevent violence and extent of full enforcement (n=133 countries).

FGM, female genital mutilation.

Services for Victims

The report surveyed six health and social services for victims, selected because evidence suggests they are either effective or promising and because they were assumed to be widely implemented. It found that 69% of countries surveyed had child protection services in place; 67%, medicolegal services for sexual violence victims; 59%, identification and referral services for child maltreatment; 53%, identification and referral services for intimate partner violence and sexual violence; 49%, mental health services; and 34% of countries had adult protective services in place.

Discussion

The homicide estimates calculated for all 194 WHO Member States are broadly in agreement with other recent estimates. This report estimates that the global number of homicides is 475,000 for 2012; the UN Office on Drugs and Crime estimate7 is 437,000, also for 2012; and the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation estimate4 is 456,000 for 2010. All three sources find higher rates in low- and middle-income countries, particularly in the Americas and Southern Africa, than in high-income countries. This convergence, which extends to the sex and age distribution and mechanisms of homicide, may in part be due to the different estimates largely drawing from the same data sources. The only other global estimate of trends in homicide rates, from the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation,4 also found rates to be declining rapidly in high-income countries since 2000, and more slowly elsewhere. Explaining this decline and differences in homicide rates across time and countries has been the focus of a rapidly growing body of scientific literature.41–46

The report also reveals that national action plans for violence prevention are often present when national survey data are not. It shows that countries are starting to invest in prevention, but not on a scale commensurate with the burden, and that policies addressing the social determinants of violence, such as poverty and education, should be strengthened. It also makes clear that enforcement of laws relevant to violence prevention, critical for establishing non-violent norms and deterring violence, remains weak in many countries and that important types of services for victims of violence—for instance, to reduce psychological trauma—are not widely implemented in many parts of the world.

To address these gaps, the report makes several recommendations relevant to national, regional, and global violence prevention efforts.2 The first is to scale up prevention programs, ensuring that they address all forms of violence, that programs targeting multiple types of violence are simultaneously prioritized, and that they are informed by evidence. The quality of the prevention programs identified through the survey should be assessed to ensure that their content and mode of delivery conform as closely as possible to evidence-based best practices. The second recommendation is to ensure that existing laws are fully enforced to close the gap between existence and enforcement of laws, and that the quality of laws is reviewed against internationally recognized standards and strengthened if required. The third recommendation is to ensure that services to identify, refer, and protect victims are comprehensive and sensitive, informed by evidence, and widely available and accessible. Particular attention should be paid to further developing mental health and adult protective services in the many countries where they remain weak. The fourth recommendation is to strengthen data collection to reveal the true extent of the problem and to develop and monitor national action plans, programs, and services. The last main recommendation is to set national, regional, and international baselines and targets for violence prevention and track progress toward their achievement.

The Global Status Report on Violence Prevention 2014 for the first time provides data on national efforts to address interpersonal violence. It has four strengths. First, the report includes recent, high-quality, and comparable homicide estimates, which draw on multiple sources of data. These provide rates by country, region, and globally; time trends; and breakdowns by sex and mechanism. Second, its coverage is comprehensive: It addresses all the main types of interpersonal violence and prevention measures and covers 133 countries, accounting for 88% of the world’s population. Third, it uses a standardized method, which included multisectoral input and consensus meetings in countries. Fourth, almost all included data have been endorsed by the governments of the countries concerned, ensuring recognition by government of the problem as described in the report, a prerequisite for governments taking responsibility for addressing interpersonal violence.

Limitations

The first limitation is that the prevalence data on non-fatal violence reported by countries varied in the definitions of violence and time frames used, precluding comparison across countries. Second, it is possible that countries overestimated the extent and quality of national violence prevention activities, particularly in determining the degree of program implementation and enforcement of laws. Third, although the survey provided an assessment of the existence and extent of implementation of measures to prevent and respond to violence, it was not designed to assess their quality or effectiveness. Fourth, efforts other than those surveyed may be taking place in countries, so it is possible that more prevention work is under way in those countries. Viewed in the context of WHO global status reports on other topics, features of the method used for this report—particularly the multisectoral input, the consensus meetings, and the process of data validation—lead the authors to have some confidence in these findings.

Conclusions

The Global Status Report on Violence Prevention 2014 shows that many countries have begun to take measures to tackle violence. Yet, it also highlights the many gaps that remain and the effort required to address them. The public health system can play a critical role in advancing government efforts to address violence. It can, for instance, make a major contribution to improving the collection of homicide data, to gathering systematic, population-based data to assess the prevalence of non-fatal violence, and to carrying out evaluation research to ensure that the programs and services being implemented are effective and make good use of scarce resources. As this report and other recent research shows,47 greater attention must be given to developing research and prevention capacity in low- and middle-income countries where it is lacking and the burden of violence is highest. For without such capacity, the potential of evidence-based violence prevention to reduce all forms of violence is unlikely to be realized.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the UBS Optimus Foundation, the Government of Belgium; the Bernard van Leer Foundation; the UN Development Programme; and CDC.

Appendix. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.10.007.

Footnotes

A detailed description of the methodology is provided in the full report, available online.2

CM wrote the first draft; AB, LD, and EK reviewed and added to it; all authors were involved in carrying out the study.

The findings of the report are presented in full in the WHO publication entitled Global Status Report on Violence Prevention 2014 (WHO, 2014).

The findings and conclusions in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of CDC.

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

References

- 1.Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R. The World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva: WHO; 2002. www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/world_report/en/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. Global Status Report on Violence Prevention 2014. Geneva: WHO; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;385(9963):117–171. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation. [Accessed August 15, 2015];GBD cause patterns—intentional injuries. http://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-cause-patterns/. Published 2015.

- 5.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2095–2128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.UN Office on Drugs and Crime. Global Study on Homicide 2011: Trends, Contexts, Data. Vienna: UN Office on Drugs and Crime; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.UN Office on Drugs and Crime. Global Study on Homicide 2013: Trends, Contexts, Data. Vienna: UN Office on Drugs and Crime; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stoltenborgh M, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van Ijzendoorn MH, Alink LRA. Cultural-geographical differences in the occurrence of child physical abuse? A meta-analysis of global prevalence. Int J Psychol. 2013;48(2):81–94. doi: 10.1080/00207594.2012.697165. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00207594.2012.697165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stoltenborgh M, van Ijzendoorn MH, Euser EM, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ. A global perspective on child sexual abuse: meta-analysis of prevalence around the world. Child Maltreat. 2011;16(2):79–101. doi: 10.1177/1077559511403920. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1077559511403920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.WHO. Global and Regional Estimates of Violence Against Women: Prevalence and Health Effects of Intimate Partner Violence and Non-partner Sexual Violence. Geneva: WHO; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bellis MA, Hughes K, Leckenby N, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and associations with health-harming behaviours in young adults: surveys in eight eastern European countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92(9):641–655. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.129247. http://dx.doi.org/10.2471/BLT.13.129247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Danese A, Moffitt TE, Harrington H, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and adult risk factors for age-related disease: depression, inflammation, and clustering of metabolic risk markers. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(12):1135–1143. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.214. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults—the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245–258. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller GE, Chen E, Parker KJ. Psychological stress in childhood and susceptibility to the chronic diseases of aging: moving toward a model of behavioral and biological mechanisms. Psychol Bull. 2011;137(6):959. doi: 10.1037/a0024768. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0024768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, Vos T. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2012;9(11):e1001349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Widom CS. Longterm consequences of child maltreatment. In: Korbin JE, Krugman RD, editors. Handbook of Child Maltreatment. New York: Springer; 2014. pp. 225–247. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Black MC. Intimate partner violence and adverse health consequences: implications for clinicians. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2011;5(5):428–439. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1559827611410265. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leeb RT, Lewis T, Zolotor AJ. A review of physical and mental health consequences of child abuse and neglect and implications for practice. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2011;5(5):454–468. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1559827611410266. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andrews G, Corry J, Slade T, Issakadis C, Swanston H. Child sexual abuse. In: Ezzati M, Lopez AD, Rodgers A, Murray CJL, editors. Comparative Quantification of Health Risks: Global and Regional Burden of Disease Attributable to Selected Major Risk Factors. Vol. 2. Geneva: WHO; 2004. pp. 1851–1940. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ttofi MM, Farrington DP, Lösel F, et al. Do the victims of school bullies tend to become depressed later in life? A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J Aggress Confl Peace Res. 2011;3(2):63–73. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/17596591111132873. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Comijs HC, Penninx B, Knipscheer KPM, van Tilburg W. Psychological distress in victims of elder mistreatment: the effects of social support and coping. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1999;54(4):P240–P245. doi: 10.1093/geronb/54b.4.p240. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geronb/54B.4.P240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coid J, Petruckevitch A, Feder G, Chung W-S, Richardson J, Moorey S. Relation between childhood sexual and physical abuse and risk of revictimisation in women: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2001;358(9280):450–454. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)05622-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05622-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim J, Cicchetti D. Longitudinal pathways linking child maltreatment, emotion regulation, peer relations, and psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;51(6):706–716. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02202.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02202.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maker AH, Kemmelmeier M, Peterson C. Child sexual abuse, peer sexual abuse, and sexual assault in adulthood: a multi-risk model of revictimization. J Trauma Stress. 2001;14(2):351–368. doi: 10.1023/A:1011173103684. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1011173103684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manly JT, Kim JE, Rogosch FA, Cicchetti D. Dimensions of child maltreatment and children’s adjustment: contributions of developmental timing and subtype. Dev Psychopathol. 2001;13(4):759–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Widom CS, Czaja SJ, Dutton MA. Childhood victimization and lifetime revictimization. Child Abuse Negl. 2008;32(8):785–796. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.12.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.WHO. Manual for Estimating the Economic Costs of Injuries Due to Interpersonal and Self-Directed Violence. Geneva: WHO; 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fang X, Fry DA, Brown DS, et al. The burden of child maltreatment in the East Asia and Pacific region. Child Abuse Negl. 2015;42:146–162. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fearon J, Hoeffler A. Benefits and Costs of the Conflict and Violence Targets for the Post-2015 Development Agenda. Copenhagen: Copenhagen Consensus Center; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30.WHO. Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2010. Geneva: WHO; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 31.WHO. Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health 2011. Geneva: WHO; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32.WHO. Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health 2014. Geneva: WHO; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 33.WHO. Global Status Report on Road Safety: Time for Action. Geneva: WHO; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 34.WHO. WHO Global Status Report on Road Safety 2013: Supporting a Decade of Action. Geneva: WHO; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 35.WHO. Violence Prevention: The Evidence. Geneva: WHO; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 36.WHO. Preventing Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Against Women: Taking Action and Generating Evidence. Geneva: WHO; 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.WHO. Preventing Child Maltreatment: A Guide to Taking Action and Generating Evidence. Geneva: WHO; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mikton C, Butchart A. Child maltreatment prevention: a systematic review of reviews. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87(5):353–361. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.057075. http://dx.doi.org/10.2471/BLT.08.057075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ploeg J, Fear J, Hutchison B, MacMillan H, Bolan G. A systematic review of interventions for elder abuse. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2009;21(3):187–210. doi: 10.1080/08946560902997181. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08946560902997181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.WHO. [Accessed March 30, 2015];WHO mortality database. www.who.int/healthinfo/mortality_data/en/

- 41.Baumer EP, Wolff KT. The breadth and causes of contemporary cross-national homicide trends. Crime Justice. 2014;43:231–287. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/677663. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eisner M. What causes large-scale variation in homicide rates? In: Heinze J, Kortuem H, editors. Aggression in Humans and Primates. Boston: De Gruyter; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eisner M. From swords to words: does macro-level change in self-control predict long-term variation in levels of homicide? Crime Justice. 2014;43:65–134. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/677662. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eisner M, Nivette A. How to reduce the global homicide rate to 2 per 100,000 by 2060. In: Loeber R, Welsh BC, editors. The Future of Criminology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012. pp. 219–228. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199917938.001.0001. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lappi-Seppala T, Lehti M. Cross-comparative perspectives on global homicide trends. Crime Justice. 2014;43:135–230. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/677979. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pinker S. The Better Angels of Our Nature: The Decline of Violence in History and Its Causes. London: Penguin; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hughes K, Bellis MA, Hardcastle KA, et al. Global development and diffusion of outcome evaluation research for interpersonal and self-directed violence prevention from 2007 to 2013: a systematic review. Aggress Violent Behav. 2014;19(6):655–662. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2014.09.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.