Abstract

Objective

To evaluate prospectively the association between male sleep duration and fecundability.

Design

Pregnancy Online Study (PRESTO), a web-based prospective cohort study of North American couples enrolled during the preconception period (2013–2017).

Setting

United States and Canada.

Patients

Male participants were aged ≥21 years; female participants were aged 21–45 years.

Interventions

None.

Main outcome measures

At enrollment, men reported their average nightly sleep duration in the previous month. Pregnancy status was updated on female follow-up questionnaires every 8 weeks for up to 12 months or until conception. Analyses were restricted to 1,176 couples who had been attempting to conceive for ≤6 cycles at enrollment. Proportional probabilities regression models were used to estimate fecundability ratios (FRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), adjusting for potential confounders.

Results

Relative to 8 hours per night of sleep, multivariable-adjusted FRs for <6, 6, 7, and ≥9 hours/night of sleep were 0.62 (95% CI: 0.45–0.87), 1.06 (95% CI: 0.87–1.30), 0.97 (95% CI: 0.81–1.17), and 0.73 (95% CI: 0.46–1.15), respectively. The association between short sleep duration (<6 hours/night) and fecundability was similar among men not working night or rotating shifts (FR=0.60, 95% CI: 0.41–0.88) and among men without a history of infertility (FR=0.62, 95% CI: 0.44–0.87), and was stronger among fathers (FR=0.46, 95% CI: 0.28–0.76).

Conclusions

Short sleep duration in men was associated with reduced fecundability. As male factor accounts for 50% of couple infertility, identifying modifiable determinants of infertility could provide alternatives to expensive fertility workups and treatments.

Keywords: sleep, fertility, time-to-pregnancy, preconception, cohort studies

INTRODUCTION

Sleep deprivation is prevalent and increasing in North America. The Institute of Medicine has estimated that 50–70 million adults in the United States (U.S.) have chronic sleep and wakefulness disorders. The percentage of U.S. adults reporting <7 hours of sleep on average nearly doubled from 1985 to 2012, reaching approximately 33% (1). Previous studies have reported U-shaped associations between sleep duration and obesity (2), cardiovascular disease (3), and all-cause mortality (4), with those sleeping 7–9 hours per night exhibiting the lowest risk of adverse health outcomes (5). Most epidemiologic studies have focused on the health effects of sleep duration, rather than sleep quality, although some evidence indicates that poor sleep quality is associated with higher mortality (6).

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine and the Sleep Research Society released a Consensus Statement in 2015 on the recommended amount of sleep to promote optimal health (5). Experts concluded that 7.0–9.0 hours of sleep were optimal for health in adults (aged 18–60 years), while fewer than 6.0 hours of sleep was insufficient (5). About 50% of experts agreed that sleep duration in the 6.0–7.0 hour range was suboptimal, but no consensus was reached on the value or harm of sleeping more than 9.0 hours (5).

The extent to which sleep duration influences male fecundity is unclear, but ecologic data suggest that the increase in sleep deprivation over the last several decades (1) has coincided with declining sperm counts among Western men (7). In addition, epidemiologic studies have shown a positive association between sleep quality and testosterone (8), which is critical for male sexual behavior and reproduction. In men, most testosterone released daily occurs during sleep (9–11). Some, but not all (12), studies have indicated that shorter sleep duration (13–15) and poor sleep quality (as measured by sleep fragmentation or obstructive sleep apnea)(8) are associated with reduced testosterone levels. An experimental study reported a 10–15% decrease in serum testosterone levels among college-aged men exposed to sleep restriction (5 hours of sleep for 8 consecutive nights) relative to a rested sleep pattern (10 hours of sleep for 3 consecutive nights) (16).

Regarding semen quality, a cross-sectional study of 953 Danish men reported that sleep disturbance, as measured by the Karolinska Sleep Questionnaire, was associated with lower sperm concentration, total sperm count, and percentage of normal morphological spermatozoa (17). In a longitudinal study of 592 Japanese college-aged men, an inverted U-shaped pattern was observed between sleep duration and both semen volume and total sperm count (18). No clear association was observed between sleep and serum reproductive hormones in either study (17, 18).

Given the recent trend toward reduced total sleep duration among Americans, the potential importance of sleep to testosterone production, and the dearth of prospective data on sleep and fertility, we evaluated the association of male sleep duration with fecundability in a prospective cohort study of North American pregnancy planners. Fecundability, the average probability of conception in a given menstrual cycle of regular unprotected intercourse, provides a direct measure of couple fecundity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Pregnancy Study Online (PRESTO) is an ongoing web-based preconception cohort study of pregnancy planners. The study methods have been described in detail elsewhere (19). Briefly, women aged 21–45 years residing in the U.S. or Canada, who are in a stable relationship with a male partner, and who are not using contraception or fertility treatment are eligible for participation. Female participants complete an online baseline questionnaire with items on demographics, behavioral factors, medical and reproductive histories, and medication use. After completion of the baseline questionnaire, females are given the option to invite their male partners to participate. Males aged ≥21 years are eligible. Male participation involves completion of a baseline questionnaire similar to the female baseline questionnaire. Females complete follow-up questionnaires every 8 weeks for up to 12 months to update pregnancy status. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Boston Medical Center, and online informed consent was obtained from all participants.

From June 2013 through July 2017, 5,601 eligible women completed the baseline questionnaire. We excluded 149 women whose baseline date of last menstrual period (LMP) was >6 months before study entry, 47 women who were pregnant at study entry, and 41 women with missing/implausible LMP data. We then excluded 1,019 women who had been trying to achieve pregnancy for more than 6 cycles at enrollment, to reduce potential for differential exposure misclassification (i.e., subfertility causing changes in behavior). Of the 4,345 remaining female participants, 2,393 (55%) invited their male partners to participate; 1,176 males (49%) enrolled.

Assessment of exposure

On the male baseline questionnaire, participants were asked, “In the last month, on average how many hours of sleep did you get each night? (If you work a night shift and sleep during day, please think about the amount of sleep you get in a given 24-hour period).” Response categories were <5, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10 or more hours. In addition, an item in the Major Depression Inventory (MDI) asked male participants how often they had “trouble sleeping at night” during the past 2 weeks. Response categories were: “all the time,” “most of the time,” “slightly more than half the time,” “slightly less than half the time,” “some of the time,” and “at no time.” The MDI was added to the male questionnaire in January 2015.

Assessment of outcome

At baseline, females reported their LMP date, usual menstrual cycle length, and the number of cycles they had attempted conception. On each follow-up questionnaire, they reported their most recent LMP date and whether they had become pregnant since the previous questionnaire. Total discrete cycles at risk were calculated as follows: cycles of attempt at study entry + [(LMP from most recent follow-up questionnaire - date of baseline questionnaire completion)/usual cycle length] +1. Females contributed observed cycles to the analysis from baseline until reported conception, loss to follow-up, withdrawal, initiation of fertility treatment or 12 cycles, whichever came first. Assessment of covariates. At enrollment, both partners reported their age, race/ethnicity; education; use of multivitamins or folate supplements; height; weight; smoking history; physical activity; intakes of alcohol, coffee, tea, and soda; reproductive history; history of physician-diagnosed medical conditions (major depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and gastroesophageal reflux disease); employment status; average work-hours per week; daily number of hours of laptop use on one’s lap; and stress using the 10-item version of the perceived stress scale (PSS-10).(20) Males were asked: “What time of day do you mainly work?” with response options of: “daytime,” “evening,” “night,” or “changing or rotating.” Females additionally reported their last method of contraception, intercourse frequency, and the couple’s annual household income. We calculated male caffeine intake by assigning a value for caffeine content per serving to each individual beverage (135 mg for coffee, 5.6 mg for decaffeinated coffee, 40 mg for black tea, 20 mg for green tea, 15 mg for white tea, 23–69 mg for individual brands of soda, and 48–280 mg for individual types of energy drinks), and then summing caffeine content across all beverages. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Total Metabolic Equivalents of Task (METs) of physical activity were calculated by multiplying the average number of hours per week engaged in various activities by metabolic equivalents estimated from the Compendium of Physical Activities (21).

Data analysis

Sleep duration was grouped into the following categories: <6, 6, 7, 8, or ≥9 hours per night, with 8 hours serving as the reference. Responses to the MDI’s item on “trouble sleeping at night” were grouped into three categories as follows: 1) at no time (reference); 2) less than half the time (includes “some of the time” and “slightly less than half the time”); and 3) more than half the time (includes “slightly more than half the time,” “most of the time,” and “all the time”). We used proportional probabilities regression models to estimate fecundability ratios (FRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between sleep measures and fecundability. The FR represents the ratio of the per-cycle probability of conception (i.e., fecundability) in each exposure category compared with the reference category. This model incorporates the baseline decline in fecundability over time and allows for left truncation due to delayed entry into the risk set. To evaluate the possibility for non-linear associations, we fit restricted cubic splines, transforming the categorical sleep duration variable into a continuous variable and assigning values of 4 to “<5 hours” and 10 to “10 or more hours.”

We selected potential confounders a priori based on the available literature and assessment of a causal diagram. Results were adjusted for male age (<25, 25–29, 30–34, ≥35 years); female age (<25, 25–29, 30–34, ≥35 years); male BMI (<25, 25–29, 30–34, ≥35 kg/m2); female BMI (<25, 25–29, 30–34, ≥35 kg/m2); female sleep duration (<6, 6, 7, 8, ≥9 hours/night); intercourse frequency (<1, 1, 2–3, ≥4 times/week); and the following male covariates: education (<16, 16, or ≥17 years); race/ethnicity (White non-Hispanic, other); smoking (current regular, current occasional, past, never); intakes of caffeine (mg/day), alcohol (drinks/week), sugar-sweetened sodas (drinks/week); PSS-10 score (continuous); folate and/or multivitamin supplement use (yes, no); previously fathered a child (yes, no); physician-diagnosed major depressive disorder (ever, never), anxiety disorder (ever, never), hypertension (ever, never), type 2 diabetes, and gastroesophageal reflux disease (ever, never); employment status (employed, unemployed); work duration (hours/week); and laptop use on one’s lap (hours/day). Additional multivariable models were constructed in which we mutually adjusted for sleep duration and sleep quality, to assess their independent effects. Additional female factors including smoking, alcohol intake, depression, and PSS-10 score made little difference in the associations and were omitted from the final models.

Missingness for covariates ranged from 0.1% (smoking, physical activity) to 1.7% (employment status); there were no missing values for age, BMI, caffeine consumption, depression, or sleep duration. Because we added the MDI and PSS-10 scales to the male questionnaire nearly two years after study initiation, the percentage of missing data for sleep quality and perceived stress was 45%, but the pattern of missingness for these variables was not appreciably related to other study variables. We used multiple imputation to handle missing data on exposure, covariates, and pregnancy status. Using SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC), we created five imputed datasets with PROC MI and combined coefficient and standard error estimates from the five data sets with PROC MIANALYZE.

RESULTS

The 1,176 couples studied contributed 754 pregnancies during 4,821 observed menstrual cycles of attempt time. At baseline, median male sleep duration was 7 hours (10th and 90th percentiles were 6 and 8 hours, respectively; mean: 6.8 hours, standard deviation: ±0.98 hours). Thirty-four percent of men reported 6 or fewer hours of sleep per night on average during the previous month. Thirty-five percent of men reported having no trouble sleeping in the previous 2 weeks whereas 16.1% reported sleep difficulty more than half the time.

Baseline characteristics of the 264 men (22%) whose female partners did and did not complete follow-up were roughly similar with respect to mean male sleep duration (hours/night: 6.7 vs. 6.8), age (years: 31.8 vs. 31.6), female partner’s age (years: 29.6 vs. 29.9), caffeine intake (mg/day: 181 vs. 178), depressive symptoms (MDI score: 10.2 vs. 9.2), and perceived stress (PSS-10 score: 15.4 vs. 14.7). Men whose partners did not complete follow-up had slightly higher BMI (28.5 vs. 27.4 kg/m2), less education (15.2 vs 15.7 years), smoked more (current smoker: 16% vs. 10%), consumed more alcohol (drinks/week: 7.0 vs. 5.9) and sugar-sweetened soda (2.9 vs. 2.4 drinks/week), worked fewer hours (42.8 vs. 44.6 hours/week), and were less likely to identify as White non-Hispanic (82% vs. 88%) than those whose partners did complete follow-up.

Total sleep duration among male partners was positively associated with White non-Hispanic race/ethnicity and being employed, and inversely associated with male age, caffeine intake, current smoking, BMI, PSS-10 score, MDI score, hypertension, and trouble sleeping (Table 1). A U-shaped relation was observed between total sleep duration and use of multivitamins or folate supplements, low educational attainment, low household income, depression, having previously fathered a child, and infertility history. Trouble sleeping at night among males was positively associated with low education, low household income, caffeine and soda intake, current smoking, having previously fathered a child, infertility history, clinical depression, anxiety, hypertension, and PSS-10 and MDI scores, and inversely associated with male sleep duration, being employed, and weekly work-hours. Female sleep duration was weakly correlated with male sleep duration (weighted kappa=0.13; Spearman r=0.19).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 1,176 male pregnancy planners according to sleep duration and trouble sleeping, PRESTO, 2013–2017.

| Average sleep duration during past month (hours/night)

|

Trouble sleeping at night during past two weeks

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <6 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ≥9 | No | Less than 50% of time | More than 50% of time | |

| Number of participants | 91 | 307 | 536 | 207 | 35 | 406 | 581 | 189 |

| Age at baseline (years), median | 32.0 | 31.0 | 31.0 | 31.0 | 30.0 | 31.0 | 31.0 | 31.0 |

| Female partner’s age at baseline (years), median | 30.0 | 30.0 | 29.0 | 30.0 | 29.0 | 30.0 | 30.0 | 29.0 |

| White, non-Hispanic, % | 86.8 | 83.4 | 87.1 | 88.4 | 94.3 | 87.0 | 86.4 | 86.2 |

| Household income <$50,000 USD, % | 18.7 | 17.3 | 14.0 | 15.9 | 28.6 | 11.8 | 15.8 | 25.4 |

| Household income ≥$150,000 USD, % | 19.8 | 14.0 | 23.9 | 19.8 | 14.3 | 21.2 | 21.3 | 13.2 |

| Less than a college degree, % | 50.6 | 34.5 | 20.7 | 25.1 | 57.1 | 26.4 | 25.7 | 41.8 |

| Employed, % | 90.1 | 92.2 | 95.3 | 93.7 | 88.6 | 96.1 | 94.2 | 86.8 |

| Hours per week of work on job, median | 40.0 | 40.0 | 42.0 | 40.0 | 40.0 | 42.0 | 40.0 | 40.0 |

| Laptop use on one’s lap (hours/day), mean | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.8 |

| BMI (kg/m2), median | 28.2 | 27.4 | 26.2 | 25.1 | 27.4 | 25.9 | 26.4 | 28.0 |

| Female partner BMI (kg/m2), median | 25.9 | 25.0 | 24.3 | 23.4 | 27.5 | 24.6 | 24.2 | 26.0 |

| Female partner sleep duration (hours/night), median | 7.0 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 8.0 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 7.0 |

| Male sleep duration (hours/night), median | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 7.0 | 7.0 | 6.0 |

| Trouble sleeping: >1/2, most, or all of time, % | 42.9 | 21.8 | 11.2 | 8.2 | 17.1 | -- | -- | -- |

| Physical activity (MET-hours/week), median | 25.0 | 26.7 | 29.9 | 29.9 | 19.4 | 29.7 | 29.1 | 25.9 |

| Multivitamin or folic acid supplement intake, % | 40.7 | 36.5 | 33.0 | 36.2 | 40.0 | 34.7 | 34.8 | 38.1 |

| Current regular or occasional smoker, % | 18.7 | 15.6 | 9.5 | 6.3 | 14.3 | 9.1 | 11.5 | 15.9 |

| Former smoker, % | 22.0 | 18.6 | 18.3 | 12.1 | 20.0 | 17.0 | 17.2 | 20.1 |

| Caffeine intake (mg/day), median | 163.5 | 159.4 | 144.3 | 135.7 | 137.1 | 149.0 | 147.6 | 156.0 |

| Alcohol intake (drinks/week), median | 3.0 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 3.5 |

| Sugar-sweetened soda intake (drinks/week), mean | 7.8 | 3.0 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 6.5 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 5.9 |

| Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) score, median | 18.0 | 16.0 | 14.0 | 14.0 | 12.0 | 13.0 | 15.0 | 19.0 |

| Major Depression Inventory (MDI) score, median | 13.0 | 10.0 | 7.0 | 6.0 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 9.0 | 17.0 |

| Major Depressive Disorder (ever), % | 9.9 | 10.1 | 8.8 | 11.6 | 20.0 | 7.1 | 10.3 | 15.3 |

| Anxiety disorder (ever), % | 13.2 | 5.9 | 7.1 | 9.7 | 11.4 | 6.4 | 7.4 | 12.2 |

| Hypertension (ever), % | 15.4 | 9.1 | 7.5 | 3.4 | 5.7 | 6.4 | 6.9 | 13.2 |

| Type 2 diabetes (ever), % | 1.1 | 3.9 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 2.2 | 1.1 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease (ever), % | 4.4 | 3.3 | 5.2 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 4.7 | 2.9 | 5.8 |

| History of infertility, % | 12.1 | 7.8 | 7.5 | 5.8 | 17.1 | 6.9 | 6.2 | 15.3 |

| Previously fathered a child, % | 53.9 | 47.2 | 40.7 | 35.8 | 48.6 | 43.6 | 40.1 | 49.2 |

| Intercourse frequency <1 time/week, % | 17.6 | 21.2 | 22.0 | 15.5 | 17.1 | 18.5 | 20.3 | 23.3 |

| Intercourse frequency ≥4 times/week, % | 14.3 | 15.0 | 13.8 | 19.8 | 14.3 | 16.8 | 15.0 | 12.7 |

| Attempt time at study entry <3 cycles, % | 68.1 | 66.8 | 68.7 | 74.4 | 60.0 | 69.2 | 70.1 | 64.6 |

Abbreviations: USD=United States’ dollars, BMI=body mass index, MET=metabolic equivalent of task.

Relative to 8 hours per night of sleep, multivariable-adjusted FRs for <6, 6, 7, and ≥9 hours/night of sleep were 0.62 (95% CI: 0.42–0.87), 1.06 (95% CI: 0.87–1.30), 0.97 (95% CI: 0.81–1.30), and 0.73 (95% CI: 0.46–1.15), respectively (Table 2). Compared with men who had no trouble sleeping, the FR for men who had trouble sleeping less than half the time was 1.06 (95% CI: 0.85–1.31) and the FR for men who had trouble sleeping more than half the time was 0.93 (95% CI: 0.72–1.20). Respective FRs for trouble sleeping based on the complete case method were similar to those based on multiple imputation (0.98, 95% CI: 0.80–1.20 and 0.84, 95% CI: 0.60–1.18). Mutual control for each sleep variable made little difference in the FRs for each sleep variable. Non-adjustment for possible causal intermediates (e.g., intercourse frequency, depression, anxiety), produced comparable results. Results were similar among men not working night or rotating/changing shifts, men without a history of infertility, and couples with <3 cycles of attempt time at study entry (Table 2). To reduce potential for misclassification of sleep over time, we restricted to the first observed cycle of pregnancy attempt for all couples; results were stronger, but less precise (<6 vs. 8 hours: FR=0.50, 95% CI: 0.26–0.98; ≥9 vs. 8 hours: FR= 0.36, 95% CI: 0.10–1.22).

Table 2.

Male sleep duration and trouble sleeping in relation to fecundability, PRESTO, 2013–2017.

| Number of conceptions | Number of cycles | Unadjusted FR (95% CI) | Adjusted FR (95% CI)a | Adjusted FR (95% CI)b | Adjusted FR (95% CI)c | Adjusted FR (95% CI)d | Adjusted FR (95% CI)e | Adjusted FR (95% CI)f | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep duration (hours) | |||||||||

| <6 | 48 | 436 | 0.68 (0.50–0.93) | 0.62 (0.45–0.87) | 0.63 (0.45–0.90) | 0.62 (0.44–0.87) | 0.60 (0.41–0.88) | 0.50 (0.26–0.98) | 0.58 (0.40–0.86) |

| 6 | 202 | 1,225 | 1.02 (0.84–1.24) | 1.06 (0.87–1.30) | 1.06 (0.87–1.31) | 1.02 (0.83–1.25) | 1.03 (0.83–1.28) | 1.04 (0.76–1.42) | 1.09 (0.87–1.38) |

| 7 | 340 | 2,142 | 0.97 (0.81–1.16) | 0.97 (0.81–1.17) | 0.97 (0.80–1.17) | 0.97 (0.81–1.17) | 0.96 (0.79–1.16) | 1.00 (0.76–1.32) | 0.97 (0.79–1.20) |

| 8 | 144 | 841 | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) |

| ≥9 | 20 | 177 | 0.75 (0.48–1.17) | 0.73 (0.46–1.15) | 0.72 (0.46–1.13) | 0.69 (0.42–1.14) | 0.76 (0.46–1.26) | 0.36 (0.10–1.22) | 0.72 (0.41–1.26) |

| Trouble sleeping | |||||||||

| None of the time | 256 | 1,681 | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) | 1.00 (Referent) |

| <50% of the time | 397 | 2,320 | 1.04 (0.85–1.25) | 1.06 (0.85–1.31) | 1.05 (0.85–1.20) | 1.07 (0.83–1.36) | 1.05 (0.82–1.34) | 1.03 (0.76–1.40) | 1.12 (0.87–1.45) |

| >50% of the time | 101 | 820 | 0.87 (0.69–1.09) | 0.93 (0.72–1.20) | 0.94 (0.73–1.22) | 0.94 (0.71–1.25) | 0.92 (0.71–1.20) | 0.89 (0.55–1.42) | 0.93 (0.68–1.27) |

FR=fecundability ratio, CI=confidence interval.

Adjusted for male and female age, male and female BMI, female partner’s sleep duration, intercourse frequency, and the following factors for males: depression, anxiety disorder, hypertension, diabetes, gastroesophageal reflux disease, race/ethnicity, education, use of multivitamins or folate supplements, smoking history, employment status, hours of work, hours of laptop use on one’s lap, physical activity, caffeine intake, alcohol intake, sugar-sweetened soda intake, perceived stress scale (PSS-10), and previously fathered a child.

Mutually adjusted for each sleep variable.

Restricted to 1,083 males (92% of cohort) without history of infertility.

Restricted to 1,018 males (87% of cohort) not working nights (N=39) or rotating/changing (N=119) shifts.

Restricted to first observed cycle of pregnancy attempt (N=294 conceptions during 1,176 cycles of attempt).

Restricted to 810 males (69% of cohort) with attempt time at study entry <3 cycles.

The association for short sleep duration (<6 hours) was stronger among men who had previously fathered a child (FR=0.46) but weaker among those who had not fathered a child (FR=0.92). In contrast, the association for long sleep duration (≥9 hours) was weaker among fathers (FR=0.85) but stronger among non-fathers (FR=0.59). These results were based on small numbers.

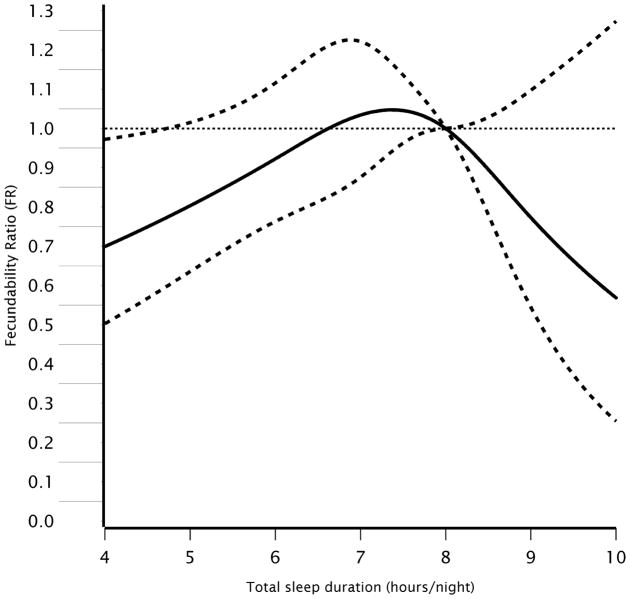

Figure 1 presents the results from restricted cubic spline models predicting fecundability from male sleep duration. Consistent with the categorical analysis, there was an inverted U-shaped pattern in which the FR was most strongly associated with reduced fecundability at the extremes of the sleep duration distribution, though numbers of men in the upper range were small.

Figure 1.

Restricted cubic spline of the association between total sleep duration and fecundability among 1,176 male PRESTO participants, 2013–2017. Reference value for spline is 8 hours of sleep per night, with knot points at 6, 7, 8, and 9 hours/night. Solid line represents the fecundability ratio (FR) and dotted lines represent the 95% confidence interval. Adjusted for male and female age, male and female BMI, female partner’s sleep duration, intercourse frequency, and the following factors among males: depression, anxiety disorder, hypertension, diabetes, gastroesophageal reflux disease, race/ethnicity, education, use of multivitamins or folate supplements, smoking history, employment status, hours of work per week, hours of laptop use on one’s lap, physical activity, caffeine intake, alcohol intake, sugar-sweetened soda intake, perceived stress scale (PSS-10) score, and previously fathered a child.

DISCUSSION

In this preconception cohort study, short sleep duration was associated with reduced fecundability. Long sleep duration was also associated with reduced fecundability, but the association was weaker and imprecise. Control for factors known or suspected to cause both sleep disturbance and subfertility (e.g., caffeine and sugar sweetened soda intake), as well as potential causal intermediates (e.g., intercourse frequency), did not appreciably affect the associations. Our results are not readily explained by night or rotating shift work, or infertility history, because exclusion of men with such histories yielded similar results. The effect of short sleep duration on fecundability was slightly stronger among men with proven fertility. Difficulty sleeping at night, as measured by the MDI, showed little association with fecundability after control for covariates including sleep duration. These associations agree with findings from previous studies showing an influence of sleep duration on testosterone levels and sperm quality (8, 12–17).

Sleep duration is the most widely-studied and most straightforward sleep measure to assess in relation to health (5). Subjective reports of sleep duration are moderately correlated with actigraph-measured sleep (22–24), with correlations ranging from 0.43 (23) to 0.47 (24), and within-subject year-to-year correlation of sleep duration, as measured by wrist actigraphy, is high (r=0.76) (25). Although sleep duration in PRESTO was consistent with national data (5, 26), some exposure misclassification was possible. We collected data on only two measures of sleep, and neither measure was validated. The calendar-time window to which the sleep questions referred was the 2–4-week period before baseline, so we could not account for changes in sleep over time. When the analysis was restricted to the first observed cycle of attempt for all couples, however, results were similar. In addition, the prospective assessment of sleep patterns relative to subfertility should produce non-differential exposure misclassification.

Unmeasured comorbid medical conditions related to both sleep patterns and fecundability could have introduced confounding, but we controlled for a wide range of comorbidities including depression, anxiety, stress, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and gastroesophageal reflux disease. In PRESTO, we found little evidence that long sleepers had more trouble sleeping or had more medical conditions (e.g., depression) at baseline, in agreement with other studies of men (27).

If couples with longer attempt times at study enrollment were more likely to have sleep disturbances, our findings could reflect reverse causation. However, results were similar among couples with fewer than 3 cycles of attempt time at enrollment, indicating that reverse causation does not explain our results. Insofar as male sleep duration was similar for couples that did and did not complete the study, differential loss to follow-up is unlikely to have introduced substantial bias.

Study strengths include enrollment of men during the preconception period to evaluate pregnancy prospectively across the entire range of the fertility spectrum. The large and geographically-diverse study population enhances generalizability. The study of fecundability is a strength because semen quality does not always correlate well with fecundability (28–30). The enrollment of couples near the beginning of their pregnancy attempts (66% within the first 3 cycles) reduces potential for selection bias and reverse causation. This is one of the few studies to enroll both partners and examine the effects of male exposure while controlling for several male and female covariates.

Regardless of the recruitment method used in a cohort study (e.g., web-based vs. inclinic), recruitment of volunteers should not affect validity of results based on internal comparisons unless the association between the study factors differs between those who do and do not volunteer. It seems unlikely that the relation between sleep and fecundability would differ between web-recruited volunteers and non-volunteers. Furthermore, our study (31) and others (32, 33) have shown that even when participation at cohort entry differs by characteristics such as age, parity, or smoking, measures of association are not biased due to self-selection.

Mechanisms by which restricted, excessive, or poor quality sleep can reduce male fecundity, are unclear. The testosterone hypothesis is supported by several studies showing that men with shorter sleep duration (13–15, 18), longer sleep duration (18), or poor sleep quality (8, 16, 17) have reduced semen quality and/or testosterone levels. However, given that little association was observed between sleep and testosterone levels in two studies that found strong associations with semen quality (17, 18), additional mechanisms might be at play. The circadian system, which is regulated by the solar light/dark cycle, modulates daily rhythms in alertness, core body temperature, heart rate, blood pressure, and hormone secretion (34). Misalignment of endogenous circadian rhythms with the sleep-wake cycle can disrupt melatonin and cortisol secretion, decrease leptin levels, and increase glucose and insulin levels (34). Melatonin, in turn, influences the secretion of gonadotropins and testosterone, enhances testicular maturation, and is a potent free radical scavenger that prevents testicular damage (35).

In this North American preconception cohort study, short sleep duration in men was associated with reduced fecundability. Results were weaker and less precise for long sleep duration, but they also suggest an association with reduced fecundability. Our results lend support to the hypothesis that sleep duration is important for male fertility.

Table 3.

Male sleep duration and trouble sleeping in relation to fecundability, stratified by fatherhood status, PRESTO, 2013–2017.

| Previously fathered a child

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (N=503)

|

No (N=673)

|

|||||

| Number of conceptions | Number of cycles | Adjusted FR (95% CI)a | Number of conceptions | Number of cycles | Adjusted FR (95% CI)a | |

| Sleep duration (hours) | ||||||

| <6 | 25 | 253 | 0.46 (0.28–0.76) | 23 | 183 | 0.92 (0.57–1.49) |

| 6 | 109 | 499 | 1.10 (0.81–1.51) | 93 | 726 | 1.02 (0.76–1.36) |

| 7 | 146 | 813 | 0.84 (0.62–1.14) | 194 | 1,329 | 1.04 (0.82–1.33) |

| 8 | 54 | 266 | 1.00 (Referent) | 90 | 575 | 1.00 (Referent) |

| ≥9 | 12 | 82 | 0.85 (0.43–1.69) | 8 | 95 | 0.59 (0.29–1.19) |

| Trouble sleeping | ||||||

| None of the time | 116 | 717 | 1.00 (Reference) | 140 | 964 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| <50% of the time | 176 | 806 | 1.12 (0.82–1.54) | 221 | 1,514 | 0.95 (0.70–1.30) |

| >50% of the time | 54 | 390 | 0.96 (0.68–1.35) | 47 | 430 | 0.90 (0.59–1.35) |

FR=fecundability ratio, CI=confidence interval.

Adjusted for male and female age, male and female BMI, female partner’s sleep duration, intercourse frequency, and the following for males: depression, anxiety disorder, hypertension, diabetes, gastroesophageal reflux disease, race/ethnicity, education, use of multivitamins or folate supplements, smoking history, employment status, hours of work per week, hours of laptop use on one’s lap, physical activity, caffeine intake, alcohol intake, sugar-sweetened soda intake, and perceived stress scale (PSS-10).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NICHD (R21-HD072326, R01-HD086742, R03-HD090315, T32-HD052458). We acknowledge the contributions of PRESTO participants and staff. We thank Mr. Michael Bairos for technical support in developing the study’s web-based infrastructure. All authors made significant contributions to the manuscript in accordance with the Vancouver group guidelines: LAW, EEH, KJR, EMM, and HTS designed the research; LAW, EEH, KJR, EMM, HTS, AKW, and CJM conducted the research; LAW analyzed the data; LAW, AKW, and CJM coded the outcome and covariate data; LAW took the lead in writing the manuscript; LAW had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. None of the authors is affiliated with any organization having a direct or indirect financial interest in the subject matter discussed in the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ford ES, Cunningham TJ, Croft JB. Trends in Self-Reported Sleep Duration among US Adults from 1985 to 2012. Sleep. 2015;38(5):829–32. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Theorell-Haglow J, Lindberg E. Sleep Duration and Obesity in Adults: What Are the Connections? Curr Obes Rep. 2016;5(3):333–43. doi: 10.1007/s13679-016-0225-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cepeda MS, Stang P, Blacketer C, Kent JM, Wittenberg GM. Clinical Relevance of Sleep Duration: Results from a Cross-Sectional Analysis Using NHANES. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12(6):813–9. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.5876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cappuccio FP, D'Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA. Sleep Duration and All-Cause Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Sleep. 2010;33(5):585–592. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.5.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Consensus Conference P, Watson NF, Badr MS, Belenky G, Bliwise DL, Buxton OM, et al. Joint Consensus Statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society on the Recommended Amount of Sleep for a Healthy Adult: Methodology and Discussion. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11(8):931–52. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.4950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rod NH, Vahtera J, Westerlund H, Kivimaki M, Zins M, Goldberg M, et al. Sleep Disturbances and Cause-Specific Mortality: Results From the GAZEL Cohort Study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2011;173(3):300–309. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levine H, Jørgensen N, Martino-Andrade A, Jaime Mendiola J, Weksler-Derri D, Mindlis I, et al. Temporal trends in sperm count: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Human Reproduction Update. 2017 doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmx022. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andersen ML, Alvarenga TF, Mazaro-Costa R, Hachul HC, Tufik S. The association of testosterone, sleep, and sexual function in men and women. Brain Res. 2011;1416:80–104. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.07.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faiman C, Winter JS. Diurnal cycles in plasma FSH, testosterone and cortisol in men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1971;33(2):186–92. doi: 10.1210/jcem-33-2-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piro C, Fraioli F, Sciarra F, Conti C. Circadian rhythm of plasma testosterone, cortisol and gonadotropins in normal male subjects. J Steroid Biochem. 1973;4(3):321–9. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(73)90056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Axelsson J, Ingre M, Åkerstedt T, Holmbäck U. Effects of Acutely Displaced Sleep on Testosterone. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2005;90(8):4530–4535. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ponholzer A, Plas E, Schatzl G, Struhal G, Brossner C, Mock K, et al. Relationship between testosterone serum levels and lifestyle in aging men. Aging Male. 2005;8(3–4):190–3. doi: 10.1080/13685530500298154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Penev PD. Association between sleep and morning testosterone levels in older men. Sleep. 2007;30(4):427–32. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goh VH, Tong TY. Sleep, sex steroid hormones, sexual activities, and aging in Asian men. J Androl. 2010;31(2):131–7. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.109.007856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reynolds AC, Dorrian J, Liu PY, Van Dongen HP, Wittert GA, Harmer LJ, et al. Impact of five nights of sleep restriction on glucose metabolism, leptin and testosterone in young adult men. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e41218. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leproult R, Van Cauter E. Effect of 1 week of sleep restriction on testosterone levels in young healthy men. JAMA. 2011;305(21):2173–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jensen TK, Andersson A-M, Skakkebæk NE, Joensen UN, Jensen MB, Lassen TH, et al. Association of Sleep Disturbances With Reduced Semen Quality: A Cross-sectional Study Among 953 Healthy Young Danish Men. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2013;177:1027–1037. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen Q, Yang H, Zhou N, Sun L, Bao H, Tan L, et al. Inverse U-shaped Association between Sleep Duration and Semen Quality: Longitudinal Observational Study (MARHCS) in Chongqing, China. Sleep. 2016;39(1):79–86. doi: 10.5665/sleep.5322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wise LA, Rothman KJ, Mikkelsen EM, Stanford JB, Wesselink AK, McKinnon C, et al. Design and Conduct of an Internet-Based Preconception Cohort Study in North America: Pregnancy Study Online. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2015;29(4):360–71. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, Irwin ML, Swartz AM, Strath SJ, et al. Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(9 Suppl):S498–504. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200009001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lemola S, Ledermann T, Friedman EM. Variability of sleep duration is related to subjective sleep quality and subjective well-being: an actigraphy study. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e71292. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cespedes EM, Hu FB, Redline S, Rosner B, Alcantara C, Cai J, et al. Comparison of Self-Reported Sleep Duration With Actigraphy: Results From the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos Sueno Ancillary Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;183(6):561–73. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lauderdale DS, Knutson KL, Yan LL, Liu K, Rathouz PJ. Self-reported and measured sleep duration: how similar are they? Epidemiology. 2008;19(6):838–45. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318187a7b0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knutson KL, Rathouz PJ, Yan LL, Liu K, Lauderdale DS. Intra-individual daily and yearly variability in actigraphically recorded sleep measures: the CARDIA study. Sleep. 2007;30(6):793–6. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.6.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Unhealthy sleep-related behaviors--12 States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(8):233–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patel SR, Blackwell T, Ancoli-Israel S, Stone KL. Osteoporotic Fractures in Men-Mr OSRG, Sleep characteristics of self-reported long sleepers. Sleep. 2012;35(5):641–8. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bonde JP, Ernst E, Jensen TK, Hjollund NH, Kolstad H, Henriksen TB, et al. Relation between semen quality and fertility: a population-based study of 430 first-pregnancy planners. Lancet. 1998;352(9135):1172–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)10514-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buck Louis GM, Sundaram R, Schisterman EF, Sweeney A, Lynch CD, Kim S, et al. Semen quality and time to pregnancy: the Longitudinal Investigation of Fertility and the Environment Study. Fertil Steril. 2014;101(2):453–62. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loft S, Kold-Jensen T, Hjollund NH, Giwercman A, Gyllemborg J, Ernst E, et al. Oxidative DNA damage in human sperm influences time to pregnancy. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(6):1265–72. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hatch EE, Hahn KA, Wise LA, Mikkelsen EM, Kumar R, Fox MP, et al. Evaluation of Selection Bias in an Internet-based Study of Pregnancy Planners. Epidemiology. 2016;27(1):98–104. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nohr EA, Frydenberg M, Henriksen TB, Olsen J. Does low participation in cohort studies induce bias? Epidemiology. 2006;17(4):413–8. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000220549.14177.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nilsen RM, Vollset SE, Gjessing HK, Skjaerven R, Melve KK, Schreuder P, et al. Self-selection and bias in a large prospective pregnancy cohort in Norway. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2009;23(6):597–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2009.01062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eckel-Mahan K, Sassone-Corsi P. Metabolism and the circadian clock converge. Physiol Rev. 2013;93(1):107–35. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00016.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li C, Zhou X. Melatonin and male reproduction. Clin Chim Acta. 2015;446:175–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2015.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]