Abstract

Brain function can be best studied by simultaneous measurements and modulation of the multifaceted signaling at the cellular scale. Extensive efforts have been made to develop multifunctional neural probes, typically involving highly specialized fabrication processes. Here, we report a novel multifunctional neural probe platform realized by applying ultra-thin nanoelectronic coating (NEC) on the surfaces of conventional microscale devices such as optical fibers and micropipettes. We fabricated the NECs by planar photolithography techniques using a substrate-less and multi-layer design, which host arrays of individually addressed electrodes with an overall thickness below 1 μm. Guided by an analytic model and taking advantage of the surface tension, we precisely aligned and coated the NEC devices on the surfaces of these conventional micro-probes, and enabled electrical recording capabilities on par with the state-of-the-art neural electrodes. We further demonstrated optogenetic stimulation and controlled drug infusion with simultaneous, spatially resolved neural recording in a rodent model. This study provides a low-cost, versatile approach to construct multifunctional neural probes that can be applied to both fundamental and translational neuroscience.

Keywords: Multifunctional neural probes, ultra-thin nanoelectronic coating, optogenetic stimulation, controlled drug infusion

TOC image

Interrogation and manipulation of specific neurons in behaving animals are crucial to improve the understanding of the highly convoluted neural circuits. These studies can be enabled by implanted multifunctional neural probes that combine electrical recording in awake animals with modulation functionalities such as optical stimulation1–5 afforded by optogenetics6, or controlled infusion of pharmacological agents7. Previous strategies of fabricating multifunctional probes include attaching conventional electrical probes to optical fibers3, and stacking different functional units on rigid8,9 or flexible substrates10. These approaches significantly increased probe dimensions to accommodate additional functionalities, which produces additional tissue damage upon implantation. Alternative approaches such as accommodating recording and microfluidic channels in fibers successfully integrated multimodality, but typically afforded one or only a few recording sites only at the probe tip1,5,11. As the effect of the stimuli is typically not localized12, better understanding of neural activities often demands simultaneous recording of a group of neurons with spatial distributions determined by the problem of interests. Therefore, a new approach that conveniently offers versatile distribution of electrical recording sites in multifunctional neural probes is highly desirable.

Here we present a strategy to create multifunctional neural probes by conformal attachment of nanoelectronic coating (NEC) devices on the surfaces of conventional non-electrical probes (Fig. 1). We demonstrated that the NEC devices provided state-of-the-art multi-channel neural recording capabilities, which were easily transferred to a number of widely used non-electrical micro-probes in neuroscience such as optical fibers and micropipettes. Because the NEC devices were ultra-flexible and typically had thickness below 1 μm, they added minimal volume to the host probes and enabled multifunctional neural probes with diameters as small as 30 μm. We further showed that these devices simultaneously recorded spatially resolved unit activities and stimulated neural activities through optogenetics and drug infusion in a mouse model. By combining conventional, off-the-shelf tools with NEC devices that can be mass-fabricated by planar photo-lithography with high resolution, we demonstrated a new approach for low cost, versatile multifunctional neural probes.

Fig. 1. Schematics of the NEC device enabled multifunctional probe.

NEC devices were fabricated separately and attached onto the surface of conventional optical fibers and glass pipettes.

NEC enabled multifunctional probes

In the efforts of developing NEC enabled multifunctional probes, the thickness and width of the NEC devices are the key design parameters. First, in order for NEC devices to readily conform to the micro-curvatures of these probes with negligible increase in the total volume, the NEC devices need to be sufficiently thin and flexible, which imposes stringent requirements on the thickness and material choice for the NEC devices. In addition, because the circumference of the hosting conventional probes spans from tens to a few hundreds of microns (Fig. 1), the width of the NEC devices and the electrode array size change accordingly. We chose to use SU8 photoresist as the insulating layers and adapted an unconventional substrate-less, multi-layer layout similarly to previously reported13,14. We incorporated high level of integration to enable multi-channel recording with diverse design patterns to accommodate various applications.

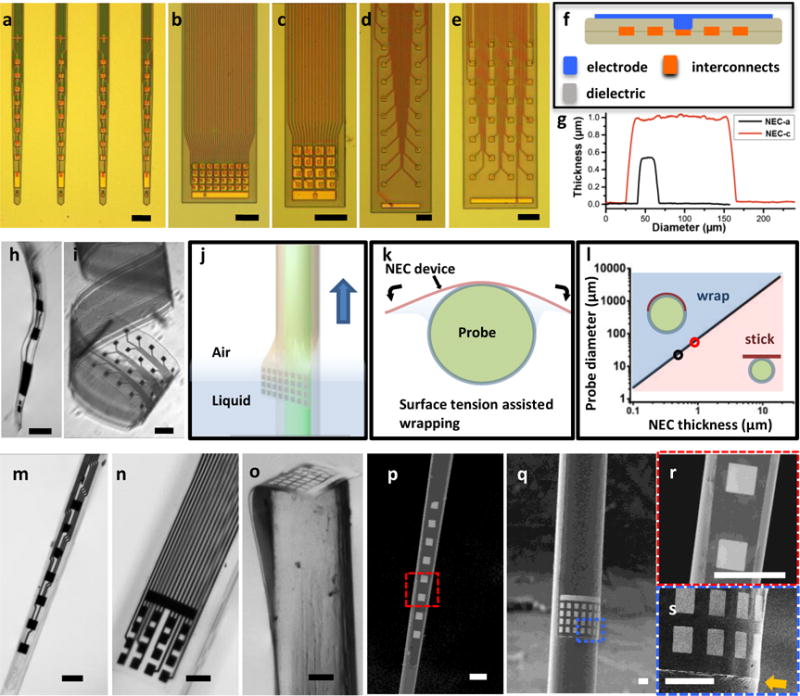

Figure 2a – e highlights a collection of as-fabricated NEC devices on substrate and demonstrated the versatile design of electrode arrays. NEC-a (Fig. 2a) hosts a linear array of 8 electrodes with minimal width of 30 μm and is designed for coating microscale probes such as micropipettes. The other NEC devices are designed for larger host probes. NEC-b and -c (Fig. 2b,c) have closely spaced electrode arrays (40 μm center to center separation) with overlapping detection range, which are designed to detect and resolve a cluster of neurons near the electrode array15,16. NEC-d and -e (Fig. 2 d,e) host multiple linear arrays along the probe, which can be used to study neural activity across cortical layers and beyond. All NEC devices have the same 4-layer structure as shown in Fig. 2f with total thickness of and below 1 μm, which is mainly determined by the thickness of insulating SU-8 layers (Fig. 2g).

Fig. 2. Fabrication and characterization of NEC devices enabled multifunctional probes.

a – e: photographs of as fabricated NEC devices type a – e on substrate, showing versatile design patterns for broad applications, including linear array of electrodes(a), 2D arrays of 32(b) and 16(c) closely spaced electrodes, 2D arrays of 2×16 electrodes(d) and 4×8 electrodes(e). Scale bar: 100 μm. f: sketch of NEC device cross-section showing the 4-layer substrate-less architect. g: Atomic force microscopy (AFM) measurements across two NEC devices showing the width and thickness. h,i: released NEC device type-a (h) and type-e (i) in water, showing the ultra-flexibility. scale bar: 100 μm. j,k: Sketch illustrating that surface tension facilitates wrapping of a NEC device on the surface of a probe as both are pulled out of water. l: Color-coded dimension dependence of the surface tension and the bending force of the NEC device, marking two regimes: blue, where the surface tension is larger than the bending force so NEC devices readily wraps on the probe surface; pink, where the surface tension is smaller than the bending force so that NEC devices do not fully comply with the probe surface. Critical probe diameters at thickness 0.5 μm and 1 μm are marked by open circles. m – o: photographs of multifunctional probes made of NEC-a wrapped on a glass micropipette (m), NEC-c wrapped on the sidewall (n) and cross-section (o) of optical fibers. scale bar: 100 μm. p,q: scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the devices in m and n. scale bar: 100 μm. r,s: zoom-in SEM images in the dashed box in p and q. The arrow highlights the edge of the NEC device and its compliance to the surface of the hosting optical fiber. Scale bar: 50 μm.

To facilitate attaching onto host probes, the NEC devices were released from substrates by etching off the sacrificial layer (Methods). The submicron thickness led to ultra-flexibility that can allow microscale deformation without damaging the embedded electronics (Fig. 2h,i). Inspired by Langmuir-Blodgett coating method17, we designed a surface tension assisted mechanism18,19 to attach the NEC devices on the surface of host probes. As illustrated in Fig. 2j, this coating process was achieved by aligning the NEC device with the host probe in water and slowly lifting both devices across the water-air interface while keeping them in contact. Surface tension forced the ultra-flexible NEC devices to form conformal adhesion on the host probe’s curved surface (Fig. 2k). We chose distilled water as the medium liquid for its high surface tension (γ = 72.0 mN/m20) and minimal residue after evaporation. By analytically modeling the interplay between surface tension at the water-air interface and the bending force of SU-8 films as detailed in Supplementary information (SI)18,21, we concluded that the sub-micron thickness of the NEC devices was necessary for the surface tension to surmount the flexural rigidity and facilitate conformal wrapping in micro-scale (Fig. 2l).

Figure 2m – s depicts several NEC enabled multifunctional brain probes, including a micropipettes (diameter < 30 μm) coated with a NEC-a device to provide a linear array of electrodes along the probe (Fig. 2m), and optical fibers (diameters 150 μm to 200 μm) coated with NEC-c and NEC-b devices (Fig. 2n,o) for different neural recording requirements. We also demonstrated aligning the electrode arrays onto the end of the host probe to provide multichannel electrical recording at the tip (Fig. 2o), which has similar geometry as previously demonstrated multifunctional probes1,5,11. As shown in the scanning electron microscope (SEM) images (Fig. 2p – q), attaching NEC devices made negligible change to the host probe volume. The NEC device was held in position by van der Waals interactions after drying in air. The bonding between NEC film and the hosting probe was enhanced by thermal curing (Methods) and was sufficient to survive multiple implantation procedures (SFig. 1,2).

In vivo recording by NEC enabled multifunctional probes

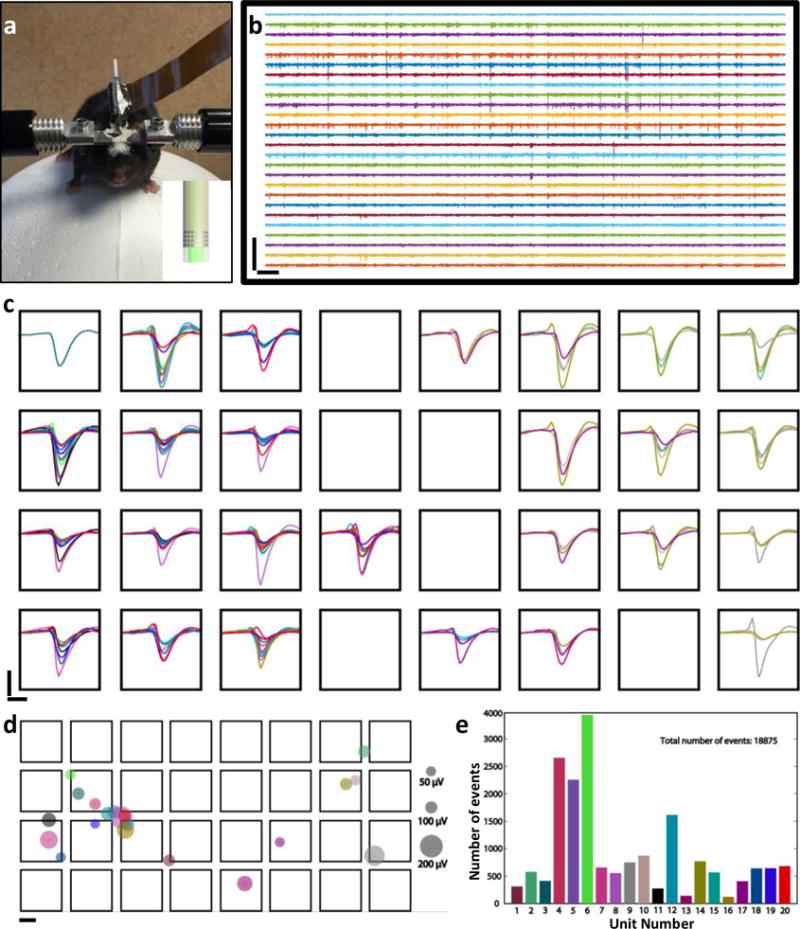

To evaluate the electrical recording performance, we implanted NEC enabled multifunctional probes into somatosensory cortex of wild-type mice and recorded from awake, behaving mice while the animals ran on a custom made treadmill similar as previous reported22 (Methods, an example of post-surgery mice is shown in Fig. 3a). Fig. 3b – e shows an example recording using a NEC-b device wrapped on an optical fiber with diameter of 250 μm, in which 26 out of 32 electrodes were functional (typical fabrication yield of this type is ~ 80%). We detected extracellular action potential (AP) waveforms from all 26 functional electrodes (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3. Demonstration of the NEC device’s electrical recording capacity.

a: Photo of a mouse on the treadmill for awake measurement. The mouse was implanted with two multifunctional probes made of NEC-c devices wrapped optical fibers. Inset shows the sketch of the implanted probe. b: 5 s recording traces (300 Hz high-pass filter applied) from the 4 × 8 electrode array (left) of on a multifunctional probe showed in a. Scale bar: 500 μV (vertical) and 0.2s (horizontal). c: Color-coded waveforms from all 20 sorted single-units plotted on the recording electrodes. Waveforms were averaged from all events recorded in 12 mins. Scale bar: 100 μV (vertical) and 1 ms (horizontal). d: Color-coded dots showing the location of neurons inferred from triangulation, where the size of the dots was scaled to the largest peak amplitude in waveforms of the corresponding unit. Same color codes as in c; electrode dimension and separation were drawn to scale. scale bar: 10 μm. e: Numbers of single unit events detected for each unit in 12 minutes recording period. Same color codes as in c and d.

As the electrodes were closely spaced with overlapping detection range, each individual neuron was detected by multiple neighboring electrodes, resulting in temporally correlated spikes from multiple recording channels. As a result, the yield and accuracy of spike sorting was greatly increased, because the identification of single units was realized not only by the characteristics of the spike waveforms but also by the spatial-temporal correlation among multiple recording sites23. We used a recently developed open-source platform, KlustaViewa24, which provides semi-automatic spike sorting for large, dense electrode array. We resolved 20 single units, the waveforms of which were color-coded and showed on the recording electrodes individually in SFig. 3 and collectively in Fig. 3c (Methods). Taking advantage of multiple recording sites for each unit, we estimated the positions of all sorted units relative to the 2D electrode array by triangulation25 using the weighted center of the detection electrodes (Fig. 3d, Methods). The oversampling capacity also allows for reliable detection and sorting of temporally sparse neural activity, e.g. unit 13 and unit 16 in Fig. 3e and SFig. 3, which is challenging for individual electrodes26. Built on the spike sorting results, we generated a real-time firing sequence in which the active neurons were highlighted for every event to visualize the spatiotemporal pattern of firing (SMovie 1). These results demonstrated that the NEC enabled multifunctional probes have electrical recording capacities on par with the state-of-art high-density neural electrical probes27,28.

Simultaneous recording and stimulation in vivo

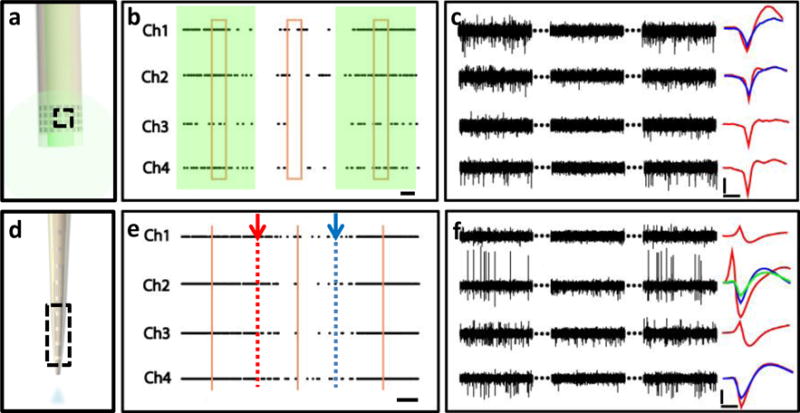

We demonstrated the multifunctional neural probes enabled by NEC devices in awake, behaving mice. We delivered optical fibers coated by NEC devices (Fig. 4a) to medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) of genetically engineered mice Thy1-mhChR2-YFP, where illuminating mhChR2-expressing neurons with blue light (450-490 nm) leads to rapid and reversible photostimulation of AP firing in these cells29. By simultaneous optical stimulation and electrical recording, we observed evoked neural activities from multiple electrodes by optical stimuli (Fig. 4b, c). The reliability of the optical stimulation was confirmed by the significant increase in AP firing rate consistently observed both from multiple electrodes (Fig. 4b, 7±2 fold averaged from 4 electrodes) and in multiple repetitions of the duty cycles (10s/10s laser on/off).

Fig. 4. Demonstration of simultaneous modulation and recording of the neural activities.

a: sketch of a multifunctional probe composed of an optical fiber and NEC-b device. Dashed box marks the electrodes used in b and c. b: Example recording from 4 channels marked in a implanted in a transgenic optogentic mouse (Thy1-mhChR2-EYFP) in mPFC. Shade marks the presence of optical stimulation using a 473 nm continuous laser excitation. Dots indicate the occurrence of APs. Box marks the region shown in c. Histograms of firing rates from individual channels are shown in SFig. 4. Horizontal bar: 2 s. c: 4 channel recording trace of 2 × 3 s (300 Hz high-pass filter applied) selected from 10 × 3 s recording as marked in b. Sorted single-unit waveforms (averaged over 200 spikes) are shown on the right. Scale bar: 50 μV (vertical) and 0.5 ms (horizontal). d: Sketch of a multifunctional probe composed of a glass pipettes and NEC-a device. Dashed box marks the electrodes used in e and f. e: Example recording from 4 channels marked in d implanted in a wild-type mouse in mPFC cortex. Arrows mark the start and finish of the controlled infusion of CNQX at 50 nL/s. Dots mark the occurrence of APs, showing lagged decrease in firing rate with CNQX infusion. Vertical lines mark the region shown in f. Histograms of firing rates in individual channels are shown in SFig. 5. Scale bar: 1 min. f: 4 channel recording trace of 2 × 3 s (300 Hz high-pass filter applied) selected from e as marked. Sorted single-unit waveforms (averaged over 1000 spikes) are shown on the right. Scale bar: 50 μV (vertical) and 0.5 ms (horizontal).

We then tested the drug delivery modality by implanting multifunctional probes in the mPFC of wild-type mice (Fig. 4d). For this purpose we fabricated multifunctional probes from pulled glass micropipettes wrapped with NEC-a, NEC-b, and NEC-d devices (depending on the pipettes’ diameter). During awake experiments, we injected CNQX at rates of 5 – 50 nl/s while recording neural activity (Methods). We observed a delayed suppression of firing rates from multiple electrodes (Fig. 4e,f). The firing rate became suppressed ~50 s after the drug infusion began and recovered ~60 s after the drug infusion was stopped. Consistent patterns were observed for repetition of drug infusion in the same mouse and on other mice under the same procedure, confirming the effectiveness of the drug delivery modality.

Discussion

The diameters of the NEC-enabled multifunctional probes in this study ranged from 30 – 200 μm, and were mainly determined by the host probes4,11. As small implant dimensions are correlated with reduced tissue damage and more stable neural recordings30, our study provides an approach to improved biocompatibility while achieving multi-functionality. The electrode pattern and the position of the NEC devices on the host probes can be adjusted according to the application to provide customized recording site arrangements, as demonstrated in Fig. 2n,o. The alignment was performed manually in this study with accuracy of 50 μm or less. We note that the surface-tension assisted wrapping mechanism is effective only for a small range of device thickness because the elastic rigidity increase sharply with thickness, e.g. only devices thinner than 2 μm can attach onto a surface with curvature of 100 μm. This stringent requirement precludes similar applications of previous flexible electronic devices with larger thicknesses4. The smallest thickness of NECs we have demonstrated is 0.5 μm (Fig. 2g), which can be coated on a probe with diameters less than 30 μm (Fig. 2l).

The ultra-thin NEC devices contain the following three functional components, similar to other multi-channel micro-fabricated neural electrical probes31: (i) electrodes, working as local recording sites; (ii) interconnects, metal leads individually connecting the electrodes and the contact pads for external electronics; (iii) insulating protection, a thin layer of insulating material protecting the interconnects. The fabrication resolution demonstrated in this study is ca. 1 μm, which is approaching the diffraction limit in research-grade photolithography. The fabrication yield is ~80% with loss mostly due to fabrication defects on the interconnects layer. We choose to use photoresist SU-8 as the insulating layers for its wide range of tunable thickness in spin coating, excellent tensile strength32 and biocompatibility33, the ease of photo-patterning, and extensive prior experience with fabrication using this material13,14.

The excellent tensile strength of SU-832 provides sufficient durability of the NEC devices despite their sub-micron thickness. Our previous studies using neural implants of similar architect demonstrated that these devices maintained functional and structural integrity for at least four months in-vivo14. In addition, we enhanced the bonding strength between NEC devices and the hosting probe by hard baking the assembled probe before implantation (Methods). We tested the durability of these devices in-vitro by performing 50 insertion-extraction cycles in hydrogel, which has similar mechanical properties as brain tissue34. We observed that the NEC devices maintained conformal adhesion on the host probe (SFig. 1). Moreover, we compared the impedance of NEC devices before and after wrapping onto hosting probes, as well as after up to 50 insertion-extraction cycles in hydrogel. Both the impedance and the yield of connected electrodes remained unchanged during these procedures (SFig. 2). These results suggest sufficient durability of NEC enabled multifunctional probes for experiments that require long-term implantation.

In this study, we presented a new approach for multifunctional neural probes by combining conventional microscale tools, such as optical fibers and pipettes, with conformally coated ultra-thin nanoelectronic devices. Because the NEC devices were fabricated separately, we can achieve high resolution, high level of integration and design versatility without being limited by the geometry and materials of the host probes. Unlike unconventional fabrication approaches that often require a specialized setup, the fabrication of NEC devices uses widely available planar photolithography techniques on silicon substrate that are optimal for massive production. More importantly, as the thickness of NEC devices are typically below 1 μm, the additional volume induced by the coating is minimal, which leads to significantly reduced tissue damage compared with conventional approaches.

Methods

NEC device fabrication and multifunctional probe preparation

The NEC devices were fabricated using planar photolithography fabrication methods similar to that previously reported13,14. After a nickel metal release layer was deposited on a silicon substrate (600 nm SiO2, n-type 0.005 V·cm, University Wafer), SU-8 photoresist (MicroChem Inc, SU-8 2000.5) was used to construct the bottom insulating layer. Then interconnects were patterned by depositing 100 nm gold. After a second insulating layer of SU8, electrodes with dimension of 30 μm × 30 μm were patterned by depositing 100 nm platinum or gold, electrically connected with the interconnects through “via”s on the top SU8 layer. After fabrication, a connector (33-pin FFC/FPC, Molex) was mounted on the matching contact pads on the Si substrate. The flexible section of the devices was then released from the substrate by soaking in nickel etchant (TFB, Transene Company) for 2 – 4 hours at 25°C, whereas the contact region remained attached to the substrate. The substrate was cleaved in water to the desired length to facilitate conformal attachment on conventional probes. The flexible section of the NEC devices was then aligned and attached to the surface of conventional probes by surface tension as discussed in the main text. The resultant probes were dried in air or in vacuum, followed by baking at 60°C in oven for 30 mins to improve the adhesion. Optional baking at 190°C in oven can further improve the adhesion, but was not required for experiments performed in this study.

Animal care and surgery procedure

Wild type male mice (C57BJ/6, 8 weeks old, Taconic) and transgenic strain Thy1-mhChR2-EYFP Line 20 (12 weeks old, The Jackson Laboratory) were used in the experiments. Mice were housed at the animal research center, UT Austin on a 12 h light/dark cycle, 22°C, with food and water available ad libitum. All procedures complied with the National Institute of Health guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals and were approved by the University of Texas Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

For surgery mice were anesthetized using isoflurane (3% for induction and maintained at 1-2%) in medical grade oxygen. The skull was exposed and prepared by scalping the crown and removing the fascia, and then was scored with the tip of a scalpel blade. A 1.5 mm × 1.5 mm square opening was drilled using a 0.7 mm spherical stainless steel burr on a surgical drill over the medial prefrontal or somatosensory cortex. The multifunctional probes were then stereotaxically inserted into the brain at the target depth at 200 – 500 μm. After implantation, Kwik-Sil (World Precision Instruments) was filled into the cranial opening. After the skull was cleaned and dried, a layer of low viscosity cyanoacrylate was applied over the skull. An initial layer of Metabond (Parkell) was applied over the cyanoacrylate and the Kwiksil, and additional Metabond was used to cement the carrier chip and the head plate to the skull. The head plate will be used for head-fixation during awake recording.

Awake electrophysiological recording

Mice were allowed a 1 – 2 weeks to recovery after surgery. For recording, mice were head constrained on a custom made air supported spherical treadmill to allow walking and running, similarly to the setup previously used for optical imaging22. The treadmill was made of an 8 inch diameter Styrofoam ball (Floracraft) levitated by a thin cushion of air between the ball and a casting containing air jets. Voltage signals from the NEC devices were amplified and digitized using a 32-channel RHD 2132 evaluation system (Intan Technologies) with a bare Ag wire inserted into the contralateral hemisphere of the brain as the grounding reference. The sampling rate was 20 kHz, and a 300 Hz high -pass and a 60 Hz notch filter were applied for single-unit recording. Mice and the amplifier were placed in a noise-attenuated, electrically shielded chamber.

Spike sorting

Spike sorting was performed automatically using open-source KlustaViewa (https://github.com/klusta-team/klustaviewa). For automatic sorting, continuous raw recording data were imported into KlustaViewa and a 300 Hz high-pass filter was applied. Spikes were detected at the strong threshold of 6 std (~ 50 μV) and the weak threshold at 3 std. Electrode spatial configuration was imported into KlustaViewa for automatic clustering at the maximum cluster number of 50. Obvious noise clusters were excluded. Pairwise cluster similarity was computed to guide semiautomatic verification and adjustment at the final step. Mask vectors with values ranging from 0 to 1 were computed from KlustaViewa for each sorted unit using rescaled peak spike amplitude on recording channels. The averaged mask vectors for all events from the same unit were used for further screening of the sorted units so that only clusters with more than 3 channels having mask values above 0.1 were selected as valid units to present in Fig. 3 and SFig. 3. In addition, only waveforms with mask values above 0.1 were used in triangulation, in which the locations of the firing neurons were estimated using weighted mean center method by weighing the coordinates of the recording channels with the peak-valley amplitude times the mask vector value.

Controlled drug infusion

Multifunctional probes composed of pulled glass pipettes and NEC devices were tested in vitro before implantation. The glass pipette (Drummond Scientific) coated with an NEC device as previously described was connected through a needle (gauge 30, BD) to a syringe controlled by an injection system (PHD 2000, Havard Apparatus) through ethylene-vinyl acetate tubing (0.5 mm inner diameter, McMaster-Carr). The injection rates were calibrated by injecting water and measuring the time and the output weight at the target rates of 1, 10, 20 and 50 nl/s. Before implantation, the needle was filled with 10 μL sterile PBS and sealed by a PDMS cap. Mice were allowed to recover for a week after surgical implantation of the probes. For drug infusion tests, the pre-filled PBS was exchanged by the same volume of 0.1 mM α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic acid (AMPA) receptor antagonist 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX), followed by the injection of the same drug at 5 – 50 nl/s for 3 mins. Awake electrical recording were performed simultaneously to monitor the suppression and recovery of neural activities. The infusion was repeated after the neural activities recovered to the base line for multiple cycles.

Optogenetic stimulation

Transgenic strain Thy1-mhChR2-EYFP Line 20 (Male, 12 weeks old, The Jackson Laboratory) was used for optogenetic stimulation of neurons. Multimode optical fibers (Ø200 μm) were used as the host probe. One end of the fiber was cleaved, inserted into a Ø1.25 mm ceramic ferrule (Thorlabs), glued in place and polished. The other end of the fiber was wrapped by NEC devices. The ferrule was mounted on the animal skull after surgical implantation. For measurements and stimulation, the ferrule was connected through a ceramic split mating sleeve to a ferrule patch cable (Thorlabs). Continuous laser excitation was presented at 473 nm at 10 mW (LRS-0473 DPSS, Laserglow) for 10s followed by 10 s laser off during neural recordings.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributions

C.X., L.L. and Z.Z. conceived and designed the study. Z.Z., L.L., S. L. and C.X. designed the NEC devices. Z.Z., and X.W. fabricated the NEC devices; Z.Z. assembled and characterized the multifunctional probes, and performed the surgical implantation. Z.Z., L.L., X.L., S.L and C.X. performed in vivo recording. J.S. and R.C. designed the optical fiber connectors used in the study. Z.Z., L.L, H.Z. and C.X analyzed the data. Z.Z., L.L. and C.X wrote the manuscript. All authors agreed on the manuscript.

Competing financial interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supporting Information

Calculation of critical radius for surface-tension assisted conformal coating, in-vitro test of NEC devices adhesion, characterization of the mechanical and electrical integrity of the NEC devices, waveforms of Individual units and their estimated location, histogram of the firing rate change in response of optical stimuli and controlled drug infusion. (PDF)

Real-time firing sequence of the sorted units (AVI)

References

- 1.Zhang J, Laiwalla F, Kim JA, Urabe H, Van Wagenen R, Song YK, Connors BW, Zhang F, Deisseroth K, Nurmikko AV. J Neural Eng. 2009;6(5):055007. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/6/5/055007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rubehn B, Wolff SB, Tovote P, Schuettler M, Luthi A, Stieglitz T. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2011;2011:2969–72. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2011.6090815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anikeeva P, Andalman AS, Witten I, Warden M, Goshen I, Grosenick L, Gunaydin LA, Frank LM, Deisseroth K. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15(1):163–70. doi: 10.1038/nn.2992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim TI, McCall JG, Jung YH, Huang X, Siuda ER, Li Y, Song J, Song YM, Pao HA, Kim RH, Lu C, Lee SD, Song IS, Shin G, Al-Hasani R, Kim S, Tan MP, Huang Y, Omenetto FG, Rogers JA, Bruchas MR. Science. 2013;340(6129):211–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1232437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.LeChasseur Y, Dufour S, Lavertu G, Bories C, Deschenes M, Vallee R, De Koninck Y. Nat Methods. 2011;8(4):319–25. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang F, Aravanis AM, Adamantidis A, de Lecea L, Deisseroth K. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8(8):577–81. doi: 10.1038/nrn2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeong JW, McCall JG, Shin G, Zhang YH, Al-Hasani R, Kim M, Li S, Sim JY, Jang KI, Shi Y, Hong DY, Liu YH, Schmitz GP, Xia L, He ZB, Gamble P, Ray WZ, Huang YG, Bruchas MR, Rogers JA. Cell. 2015;162(3):662–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rubehn B, Wolff SB, Tovote P, Luthi A, Stieglitz T. Lab Chip. 2013;13(4):579–88. doi: 10.1039/c2lc40874k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho IJ, Baac HW, Yoon E. IEEE Micr Elect. 2010:995–998. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu Y, Li Y, Pan J, Wei P, Liu N, Wu B, Cheng J, Lu C, Wang L. Biomaterials. 2012;33(2):378–94. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.09.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canales A, Jia X, Froriep UP, Koppes RA, Tringides CM, Selvidge J, Lu C, Hou C, Wei L, Fink Y, Anikeeva P. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(3):277–84. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee JH, Durand R, Gradinaru V, Zhang F, Goshen I, Kim DS, Fenno LE, Ramakrishnan C, Deisseroth K. Nature. 2010;465(7299):788–792. doi: 10.1038/nature09108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xie C, Liu J, Fu TM, Dai X, Zhou W, Lieber CM. Nat Mater. 2015;14(12):1286–92. doi: 10.1038/nmat4427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luan L, Wei X, Zhao Z, Siegel JJ, Potnis O, Tuppen AC, Lin S, Kazmi S, Fowler AR, Holloway S, Dunn KA, Chitwood AR, Xie C. Sci Adv. 2017;3(2):e1601966. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1601966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blanche TJ, Spacek MA, Hetke JF, Swindale NV. J Neurophysiol. 2005;93(5):2987–3000. doi: 10.1152/jn.01023.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Du J, Blanche TJ, Harrison RR, Lester HA, Masmanidis SC. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e26204. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aoki A, Miyashita T. Adv Mater. 1997;9(4):361–&. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Py C, Reverdy P, Doppler L, Bico J, Roman B, Baroud CN. Phys Rev Lett. 2007;98(15) doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.156103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roman B, Bico J. J Phys-Condens Mat. 2010;22(49) doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/22/49/493101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franklin K. Introduction to biological physics for the health and life sciences. Wiley; Chichester, West Sussex: 2010. p. 455. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pericet-Camara R, Best A, Butt HJ, Bonaccurso E. Langmuir. 2008;24(19):10565–10568. doi: 10.1021/la801862m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dombeck DA, Khabbaz AN, Collman F, Adelman TL, Tank DW. Neuron. 2007;56(1):43–57. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewicki MS. Network. 1998;9(4):R53–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rossant C, Kadir SN, Goodman DF, Schulman J, Hunter ML, Saleem AB, Grosmark A, Belluscio M, Denfield GH, Ecker AS, Tolias AS, Solomon S, Buzsaki G, Carandini M, Harris KD. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19(4):634–41. doi: 10.1038/nn.4268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gray CM, Maldonado PE, Wilson M, McNaughton B. J Neurosci Methods. 1995;63(1–2):43–54. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(95)00085-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamel EJ, Grewe BF, Parker JG, Schnitzer MJ. Neuron. 2015;86(1):140–59. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.03.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buzsaki G. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7(5):446–51. doi: 10.1038/nn1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Csicsvari J, Henze DA, Jamieson B, Harris KD, Sirota A, Bartho P, Wise KD, Buzsaki G. J Neurophysiol. 2003;90(2):1314–23. doi: 10.1152/jn.00116.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arenkiel BR, Peca J, Davison IG, Feliciano C, Deisseroth K, Augustine GJ, Ehlers MD, Feng G. Neuron. 2007;54(2):205–18. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kozai TD, Langhals NB, Patel PR, Deng X, Zhang H, Smith KL, Lahann J, Kotov NA, Kipke DR. Nat Mater. 2012;11(12):1065–73. doi: 10.1038/nmat3468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kipke DR, Vetter RJ, Williams JC, Hetke JF. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2003;11(2):151–5. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2003.814443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robin CJ, Vishnoi A, Jonnalagadda KN. J Microelectromech Syst. 2014;23(1):168–180. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nemani KV, Moodie KL, Brennick JB, Su A, Gimi B. Mater Sci Eng, C. 2013;33(7):4453–9. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pomfret R, Miranpuri G, Sillay K. Ann Neurosci. 2013;20(3):118–22. doi: 10.5214/ans.0972.7531.200309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.