Abstract

Sequencing technology has facilitated a new era of cancer research, especially in cancer genomics. Using next-generation sequencing, thousands of long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) have been identified as abnormally altered in the cancer genome or differentially expressed in tumor tissues. These lncRNAs are associated with imbalanced gene regulation and aberrant biological processes that contribute to malignant transformation. The functions and therapeutic potential of cancer-related lncRNAs have attracted considerable interest in the past few years. Although few lncRNAs have been well-characterized, researchers have recently made impressive progress in understanding lncRNAs and their novel functions, such as regulation of gene expression, metabolism and DNA repair. These latest findings reinforce the crucial roles of lncRNAs in cancer initiation and development, as well as their possible clinical applications.

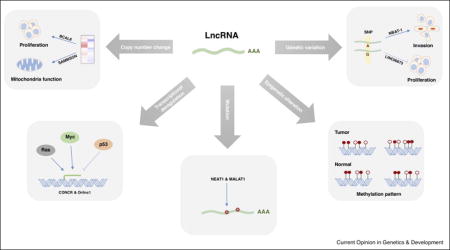

Graphical abstract

Introduction

The human genome contains thousands of noncoding regions, which were considered “junk DNA” for decades because of a lack of evidence for their transcription and failure to encode proteins. Recent technological advances, like tiling arrays and next-generation sequencing, revealed that the human genome, including the noncoding regions, is pervasively transcribed. Up to 75% of the human genome can be transcribed into RNAs, whereas less than 2% encodes proteins [1]. Much of the human transcriptome is composed of noncoding RNAs, including long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs), one of the major subtypes. RNA transcripts >200 nucleotides without apparent protein-coding potential are considered lncRNAs. After the initial cloning of lncRNA genes such as H19 and Xist from cDNA libraries, a large number of lncRNA genes have been identified genome-wide [2,3]. According to the latest GENCODE consortium release (version 26), 15,787 lncRNA genes have been identified in the human genome, yielding 27,720 lncRNA transcripts. Although lncRNAs are widely expressed in human tissues, they are under weaker selective constraints during evolution, and are less abundant and more tissue-specific than protein-coding genes [4].

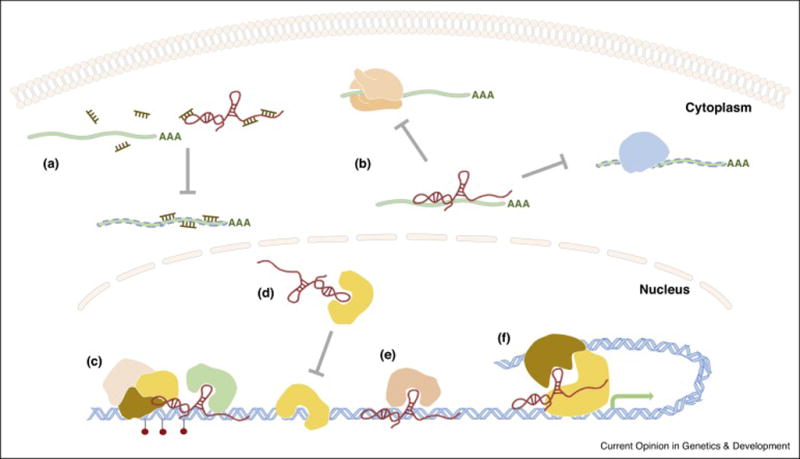

Once known as genomic “dark matter,” current evidence indicates that lncRNAs participate in several biological processes (Figure 1). Acting as transcription signal activators, decoys, guides, or scaffolds for their binding partners are typical molecular mechanisms of lncRNAs [5]. They can regulate transcriptional activity in a cis or trans manner, by recruiting transcription factors or epigenetic modification complexes [6]. LncRNAs are also important for posttranscriptional regulation. They can modulate alternative splicing [7], undergo processing to small RNAs [8], regulate mRNA degradation and translation [9,10], or act as microRNA sponges (competitive endogenous RNAs) [11]. Moreover, a special subset of lncRNAs, enhancer RNAs, are transcribed from enhancer region or a gene neighboring locus and influence gene transcription [12]. In addition to their physiologic roles, lncRNAs are associated with diseases especially with cancer. For example, HOTAIR [13], PCAT1 [14], MALAT1 [15] and FAL1 [16] have been implicated in a variety of human cancers.

Figure 1. The major molecular mechanisms of lncRNAs.

A. LncRNA as competitive endogenous RNAs. B. LncRNA binds to mRNA, represses translation and degradation of targeted mRNA. C. LncRNA serves as scaffold, e.g. recruits chromatin modification complex. D. LncRNA acts as decoy. E. LncRNA guides protein to specific location. F. LncRNA (e.g. enhancer RNA) tethers transcription factors to promoter region.

Despite the large number of lncRNAs in the human genome, few have been well-characterized. The majority of lncRNA genes, especially cancer-related lncRNAs, need to be annotated and further explored. Here, we review recent research into the roles of lncRNAs in cancer (Table 1), and provide an overview of newly annotated lncRNAs and their potential in cancer diagnosis and therapy.

Table 1.

Selected cancer-related lncRNAs

| LncRNA | Cancer type | Function in cancer | Mechanism | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCAL8 | Breast/Ovarian/Endometrial | Promotes proliferation, associated with survival of breast cancer patients | Induces G1 cell cycle arrest by affecting target genes like cyclinE2 | 18 |

| SAMMSON | Melanoma | Promotes survival, sensitizes melanoma to MAPK-targeting therapy when knocking down | Regulates mitochondrial function by binding to p32, increases its pro-oncogenic function | 19 |

| CCAT2 | Colorectal | Regulates metabolism in allele-specific manner | Binds to Cleavage Factor I complex, then regulates alternative splicing of GLS | 20 |

| LINC00673 | Pancreatic | Inhibits cell proliferation | Promotes PTPN11 degradation, regulates SRC–ERK and STAT1 signaling | 24 |

| CONCR | multiple | Required for cell division, proliferation and sister chromatid cohesion | Interacts with DDX11 and enhances the ATPase activity of DDX11 | 31 |

| LINP1 | Breast | Regulates NHEJ activity, modulates sensitivity of radiotherapy response | Links Ku80 and DNA-PKcs, increases activity of NHEJ pathway and enhances DSB repair | 33 |

| SLNCR1 | Melanoma | Increases Melanoma Invasion, associated with survival | Increases the binding of AR to MMP9 promoter | 35 |

| NKILA | Breast | Suppresses metastasis, represses cancer-associated inflammation | Binds to NF-kB/IkB complex, masks the phosphorylation sites of IkB and stabilizs the complex | 36 |

| MAYA | Breast | Promotes metastasis, correlate with poor outcome | Mediates ROR1–HER3 and the Hippo–YAP pathway crosstalk | 37 |

| GClnc1 | Gastric | Promotes proliferation and metastasis | Acted as scaffold for WDR5 and KAT2A complexes, modulates histone modification of target genes | 38 |

| LINK-A | Breast | Promotes tumor growth and glycolysis | Mediates HIF1 phosphorylation, leading to normoxic HIF1 stabilization | 39 |

| Breast | Confers resistance to AKT inhibitors | Binds to AKT, promotes AKT–PIP3 interaction and the enzymatic activation of AKT | 52 | |

| NRCP | Ovarian | Promotes proliferation, metastasis and glycolysis | Enhances interaction of STAT1 and RNA pol II, increasing STAT1 transcriptional activity | 40 |

| SNHG5 | Colorectal | Upregulated in colorectal cancer, promotes survival | Stabilizes target transcripts through blocking their degradation induced by STAU1 | 41 |

| lnc-EGFR | Hepatocellular | Promotes hepatocellular carcinoma immune evasion | Binds to and stabilizes EGFR, increases activities of EGFR/AP1/NF-AT1 | 43 |

| NEAT1 | multiple | Predicts chemotherapy response | Promotes ATR signaling and engaged in negative feedback loop for p53 activity | 49 |

| IncARSR | Renal | Promotes sunitinib resistance, transfers to sensitive cells through exosomes | Act as ceRNA of AXL and c-MET by binding miR-34/miR-449 | 51 |

LncRNAs in the cancer genome

Cancer is primarily a genetic disease involving multiple alternations in the genome, including copy number changes, somatic or germline variations, and changes in epigenetic modifications. Such alterations occur not only in protein-coding genes, but also in noncoding regions [17]. They may cause dysregulation of some lncRNA genes, which contributes to tumorigenesis, making them candidate cancer genes. A comprehensive study analyzing lncRNA alterations in 5,860 tumor samples from 13 cancer types from the Cancer Genome Atlas project revealed somatic copy number alterations (SCNAs) of lncRNAs in cancer [18]. On average, 13.16% and 13.53% of lncRNA genes have high-frequency gains and losses, respectively. Ovarian and lung squamous cell carcinomas have the most lncRNAs with high-frequency SCNAs. In addition to the genome-wide landscape, individual lncRNAs with copy number changes have also been identified and characterized. In melanoma, focal amplifications are observed at chromosome 3p13 and 3p14. At this locus, lncRNA SAMMSON is consistently co-gained with the melanoma-specific oncogene MITF, but the expression of SAMMSON is controlled by the lineage-specific transcription factor SOX10, instead of MITF. SAMMSON controls mitochondrial function and is critical for melanoma growth and survival; knockdown of SAMMSON dramatically decreases melanoma cell viability, regardless of BRAF, NRAS, or TP53 mutational status [19]. CCAT2, which resides in the 8q24 amplicon and harbors a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), can modulate energy metabolism in colon cancer cells in an allele-specific manner [20].

Since approximately 80% of disease-associated SNPs are located in noncoding regions [21], overlap between lncRNAs and cancer-associated SNPs is common [18,22]. NBAT-1, an lncRNA that contains a high-risk neuroblastoma-associated SNP in its intron, controls cell proliferation and invasion, and predicts the clinical outcome of neuroblastoma. This SNP contributes to the differential expression of NBAT-1 in neuroblastoma [23]. Notably, the potential tumor suppressor lncRNA LINC00673, the germline variation of which is associated with pancreatic cancer risk, inhibits pancreatic cancer cell proliferation by promoting PTPN11 degradation in an allele-specific manner. The germline variation of LINC00673 creates a binding site for miR-1231, which diminishes LINC00673 activity and confers susceptibility to tumorigenesis [24]. Germline variations can also affect lncRNAs by modulating their distal regulatory elements. A prostate cancer risk-associated SNP located in a distal enhancer of lncRNA PCAT1 increases the binding of transcription factors ONECUT2 and AR to the enhancer and the PCAT1 promoter, thereby upregulating PCAT1 expression. PCAT1 then recruits AR and LSD1 to the enhancers of GNMT and DHCR24, two genes implicated in prostate cancer development and progression [25].

In addition to SCNAs and genetic variation, the DNA methylation patterns in the promoter regions of lncRNAs are also distinct in tumor and normal samples, suggesting that DNA methylation-mediated epigenetic alterations occur at lncRNA gene promoter regions during tumorigenesis [18]. Evidence of copy number and methylation pattern changes supports the finding that lncRNAs are differentially expressed in many cancer types. Another large-scale study analyzed lncRNA expression using data from 7,256 RNA-seq from tumors, normal tissues, and tumor cell lines [22]. This approach identified approximately 8,000 lineage- or cancer-associated lncRNAs, providing resources for future cancer biomarker identification.

Although the consequences of somatic mutations at noncoding regions are not well understood, growing evidence suggests that they may play an important role in human cancer. A genome-wide landscape of mutations in noncoding regions has been reported in chronic lymphocytic leukemia [26] and liver cancer patients [27]. Six lncRNA genes, including NEAT1 and MALAT1, are recurrently mutated in liver cancer [27]. The efforts of the Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes project, which aims to identify mutations in more than 2,800 cancer whole genomes, will help us further understand the roles of mutations in noncoding elements.

Annotation and characterization of lncRNAs in cancer

Although our knowledge about lncRNAs expands rapidly, the identification and characterization of functional lncRNAs in cancer remains challenging. Researchers are trying to annotate more functional lncRNAs by integrating computational and experimental approaches. Using a CRISPR–Cas9 single guide RNA library that targets regions involved in melanoma drug resistance, researchers have identified functional noncoding elements that contribute to gene regulation and chemotherapeutic resistance [28]. Similarly, a CRISPR–Cas9 paired guide RNA library has been applied to generate lncRNA deletions and perform “loss-of-function” screenings [29]. This high-throughput CRISPR-based approach identified 51 lncRNAs, 9 of which have been functionally validated, that positively or negatively regulate human cancer cell growth. Cancer type-specific lncRNAs associated with particular functions have also been identified. By combining global run-on sequencing and RNA-seq data from ER-treated MCF7 cells, researchers identified lncRNAs that regulate cell cycle gene expression and proliferation in breast cancer cells [30].

In addition to modulating gene regulation, lncRNAs are themselves subjected to regulation, directly or indirectly, by important cancer genes, such as TP53 and MYC. The expression of lncRNA CONCR is negatively regulated by TP53 and activated by MYC. CONCR binds its neighboring gene, DDX11, and enhances the ATPase activity of DDX11, thereby impairing sister chromatid cohesion, cell division, and proliferation [31]. TP53 also regulates lncRNAs involved in DNA damage. DINO is induced by DNA damage in a TP53-dependent manner. Conversely, DINO stabilizes TP53 by binding the protein and regulates TP53-dependent gene expression, cell cycle arrest, and apoptosis in response to DNA damage [32]. The lncRNA LINP1 is indirectly regulated by TP53. Interestingly, LINP1 expression can be activated by EGFR signaling and blocking LINP1 increases triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) sensitivity to radiotherapy. LINP1 enhances double-strand DNA break repair via the non-homologous end joining pathway by linking Ku80 and DNA-PKcs. [33]. Furthermore, a recent study shows that RAS signaling regulates the expression of a group of lncRNAs. One of the targeted lncRNAs, Orilnc1, is highly expressed in BRAF-mutant melanoma and acts as a mediator of RAS/RAF activation [34].

The regulatory network between lncRNAs and protein-coding genes suggests their key roles in cancer development. Like their protein-coding counterparts, lncRNAs can act as oncogenes or tumor suppressors. They appear to participate in almost every cancer-related process, including cell proliferation, differentiation, metastasis, immune responses, metabolism, apoptosis, and genome stability. Novel cancer-associated lncRNAs have recently been characterized for different cancer phenotypes. Several lncRNAs with diverse molecular mechanisms modulate metastasis in melanoma [35], breast [36,37] and gastric cancers [38]. The lncRNAs LINK-A [39] and NRCP [40], which are highly expressed in TNBC and ovarian cancer, respectively, promote glycolysis and tumor growth. Depletion of the lncRNA SNHG5 induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells [41]. By acting as a molecular decoy, the DNA damage-induced lncRNA NORAD regulates genome stability by sequestering PUMILIO and inhibiting PUMILIO-mediated mRNA degradation. Identification of this lncRNA provides evidence for an unexplored role of lncRNAs in modulating genome stability [42]. Although lncRNAs can influence the immune system, little is known about immune-related lncRNAs in cancer. One recent example, lnc-EGFR, is upregulated in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. High lnc-EGFR expression leads to regulatory T cell differentiation and cytotoxic T lymphocyte inhibition in an EGFR-dependent manner, thus promoting hepatocellular carcinoma immune evasion [43].

LncRNAs for cancer diagnosis and therapy

Their aberrant expression in cancer, striking tissue specificity, and versatile regulation network, in combination with their sheer quantities, suggest that lncRNAs could represent a new class of diagnostic markers and therapeutic targets for cancer. The first prominent example of an lncRNA as a cancer biomarker is PCA3 [44]. The Food and Drug Administration has approved the testing of patient urine samples for PCA3 for the detection of prostate cancer. Compared to the widely used serum PSA testing, the noninvasive PCA3 test is more specific and accurate. Other lncRNA biomarkers have been identified in hepatocellular carcinoma [45] and gastric cancer [46] patients.

In addition to their use as diagnostic markers, lncRNAs are being targeted for cancer therapy. One of the main strategies is using small interfering RNAs to inhibit lncRNA expression. This method is limited by the intracellular localization of some lncRNAs. For those located in the nucleus, modified antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), which induce RNase H-dependent degradation or sterically block lncRNA activity, can be applied. Unlike siRNAs, ASOs can be subjected to more extensive chemical modifications, such as the addition of 2′-O-methyl and locked nucleic acids at both their 5′ and 3′ ends, to increase their stability. A recent preclinical study demonstrated the use of an ASO in a mouse breast cancer model. The ASO-induced reduction of lncRNA MALAT1 in this metastatic luminal B breast cancer model slowed tumor growth and, remarkably, induced a cystic, poorly metastatic tumor phenotype [47]. Additionally, ribozymes or deoxyribozymes can be utilized when siRNAs or ASOs cannot be designed (due to short length or secondary structure) [48]. These RNA-based therapeutic technologies are promising, but remain limited currently. Particularly, targeting lncRNAs in vivo is challenging because of the relatively poor stability and intracellular uptake of siRNAs and ASOs. New technologies, including biocompatible nanoparticle-based delivery, should be developed to overcome these problems [49]. Alternatively, since massive lncRNAs are capable of protein binding, especially with the chromatin modification complex, disrupting the interactions of lncRNAs with their binding partners is also a therapeutic strategy.

A group of lncRNAs has also been reported to be related to drug responses and resistance. The expression of NEAT1 isoform 2 predicts responses to chemotherapy in ovarian cancer patients. Targeting it sensitizes cancer cells to chemotherapy [50]. Another lncRNA, lncARSR, promotes sunitinib resistance in renal cell carcinoma and correlates with poor sunitinib responses in patients. Intriguingly, this lncRNA can be incorporated into exosomes, through which it disseminates sunitinib resistance to sensitive cells [51]. In addition, CCAT1 predicts BET inhibitor sensitivity in colorectal cancer [52], and LINK-A sensitizes breast cancer cells to AKT inhibitors [53]. These findings indicate the potential of using lncRNAs to predict drug responses and guide patient selection in clinic. Furthermore, the combination of chemotherapy and lncRNA targeting can be “synthetic lethal,” thereby providing advantages for cancer therapy.

Conclusions

The discovery of noncoding RNAs, especially lncRNAs, profoundly advanced our knowledges of cancer biology and the strategies for developing cancer diagnosis and therapy. Here, we discussed the current findings on the annotation and functional characterization of cancer-associated lncRNAs, their genomic alterations and differential expression in the context of cancer, and their applications in the clinic. Nonetheless, our understanding of lncRNAs is still in the early stages. Their huge variety and low abundance make it difficult to infer the functions of lncRNAs by dissecting individual examples. Recently, using FANTOM5, Hon et al. [54] generated a comprehensive atlas of human lncRNAs with high-confidence 5′ ends and their expression profiles across 1,829 samples from the major human primary cell types and tissues. It further elucidates the functional potential of lncRNAs and is a valuable resource for future lncRNA research. LncRNAs hold great promise for novel therapeutic applications and, therefore, should be more thoroughly investigated in future studies. For example, given that the secondary structures of lncRNAs are crucial to their functions, investigations into lncRNAs structures require attention. Moreover, although lncRNA genes are less conserved than protein-binding genes, the development of genetic animal models, like knockout mouse models of lncRNAs [55], will help us better understand their functions in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We apologize to colleagues whose work was not discussed or cited in this review due to the space limitation. This work was supported, in whole or in part, by the US Department of Defense (PC140683 to CVD), the US National Institutes of Health (R01CA142776 to LZ, R01CA190415 to LZ, P50CA083638 to LZ, P50CA174523 to LZ, P50CA083639 to AKS, P50CA098258 to AKS), the Breast Cancer Alliance (LZ and CVD), the Frank McGraw Memorial Chair in Cancer Research (AKS), the American Cancer Society Research Professor Award (AKS), the Marsha Rivkin Center for Ovarian Cancer Research (LZ), the Basser Center for BRCA (LZ), the Harry Fields Professorship (LZ), the Kaleidoscope of Hope Ovarian Cancer Foundation (LZ), the Ovarian Cancer Research Fund (XH), and the Foundation for Women’s Cancer (XH).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Djebali S, Davis CA, Merkel A, Dobin A, Lassmann T, Mortazavi A, Tanzer A, Lagarde J, Lin W, Schlesinger F, et al. Landscape of transcription in human cells. Nature. 2012;489:101–108. doi: 10.1038/nature11233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orom UA, Derrien T, Beringer M, Gumireddy K, Gardini A, Bussotti G, Lai F, Zytnicki M, Notredame C, Huang Q, et al. Long noncoding RNAs with enhancer-like function in human cells. Cell. 2010;143:46–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khalil AM, Guttman M, Huarte M, Garber M, Raj A, Rivea Morales D, Thomas K, Presser A, Bernstein BE, van Oudenaarden A, et al. Many human large intergenic noncoding RNAs associate with chromatin-modifying complexes and affect gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:11667–11672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904715106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Derrien T, Johnson R, Bussotti G, Tanzer A, Djebali S, Tilgner H, Guernec G, Martin D, Merkel A, Knowles DG, et al. The GENCODE v7 catalog of human long noncoding RNAs: analysis of their gene structure, evolution, and expression. Genome Res. 2012;22:1775–1789. doi: 10.1101/gr.132159.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang KC, Chang HY. Molecular mechanisms of long noncoding RNAs. Mol Cell. 2011;43:904–914. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsai MC, Manor O, Wan Y, Mosammaparast N, Wang JK, Lan F, Shi Y, Segal E, Chang HY. Long noncoding RNA as modular scaffold of histone modification complexes. Science. 2010;329:689–693. doi: 10.1126/science.1192002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonzalez I, Munita R, Agirre E, Dittmer TA, Gysling K, Misteli T, Luco RF. A lncRNA regulates alternative splicing via establishment of a splicing-specific chromatin signature. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015;22:370–376. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilusz JE, Freier SM, Spector DL. 3′ end processing of a long nuclear-retained noncoding RNA yields a tRNA-like cytoplasmic RNA. Cell. 2008;135:919–932. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoon JH, Abdelmohsen K, Srikantan S, Yang X, Martindale JL, De S, Huarte M, Zhan M, Becker KG, Gorospe M. LincRNA-p21 suppresses target mRNA translation. Mol Cell. 2012;47:648–655. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gong C, Maquat LE. lncRNAs transactivate STAU1-mediated mRNA decay by duplexing with 3′ UTRs via Alu elements. Nature. 2011;470:284–288. doi: 10.1038/nature09701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Du Z, Sun T, Hacisuleyman E, Fei T, Wang X, Brown M, Rinn JL, Lee MG, Chen Y, Kantoff PW, et al. Integrative analyses reveal a long noncoding RNA-mediated sponge regulatory network in prostate cancer. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10982. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orom UA, Shiekhattar R. Long noncoding RNAs usher in a new era in the biology of enhancers. Cell. 2013;154:1190–1193. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta RA, Shah N, Wang KC, Kim J, Horlings HM, Wong DJ, Tsai MC, Hung T, Argani P, Rinn JL, et al. Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR reprograms chromatin state to promote cancer metastasis. Nature. 2010;464:1071–1076. doi: 10.1038/nature08975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prensner JR, Iyer MK, Balbin OA, Dhanasekaran SM, Cao Q, Brenner JC, Laxman B, Asangani IA, Grasso CS, Kominsky HD, et al. Transcriptome sequencing across a prostate cancer cohort identifies PCAT-1, an unannotated lincRNA implicated in disease progression. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:742–749. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gutschner T, Hammerle M, Diederichs S. MALAT1 – a paradigm for long noncoding RNA function in cancer. J Mol Med (Berl) 2013;91:791–801. doi: 10.1007/s00109-013-1028-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu X, Feng Y, Zhang D, Zhao SD, Hu Z, Greshock J, Zhang Y, Yang L, Zhong X, Wang LP, et al. A functional genomic approach identifies FAL1 as an oncogenic long noncoding RNA that associates with BMI1 and represses p21 expression in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2014;26:344–357. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khurana E, Fu Y, Chakravarty D, Demichelis F, Rubin MA, Gerstein M. Role of non-coding sequence variants in cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 2016;17:93–108. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2015.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18••.Yan X, Hu Z, Feng Y, Hu X, Yuan J, Zhao SD, Zhang Y, Yang L, Shan W, He Q, et al. Comprehensive Genomic Characterization of Long Non-coding RNAs across Human Cancers. Cancer Cell. 2015;28:529–540. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.09.006. This study comprehensively analyzed alternations of lncRNA genes in multi cancer types. Providing the example of how to systematically identify cancer driver lncRNAs. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19•.Leucci E, Vendramin R, Spinazzi M, Laurette P, Fiers M, Wouters J, Radaelli E, Eyckerman S, Leonelli C, Vanderheyden K, et al. Melanoma addiction to the long non-coding RNA SAMMSON. Nature. 2016;531:518–522. doi: 10.1038/nature17161. This study identified a melanoma-specific lncRNA SAMMON, which bind to p32 to increase its mitochondrial targeting and pro-oncogenic function. Inhibiting SAMMON can distrupt mitochondrial functions in a cancer-cell-specific manner thus has antimelanoma potential. Most importantly, targeting SAMMON sensitizes melanoma to MAPK-targeting therapeutics. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Redis RS, Vela LE, Lu W, Ferreira de Oliveira J, Ivan C, Rodriguez-Aguayo C, Adamoski D, Pasculli B, Taguchi A, Chen Y, et al. Allele-Specific Reprogramming of Cancer Metabolism by the Long Non-coding RNA CCAT2. Mol Cell. 2016;61:520–534. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freedman ML, Monteiro AN, Gayther SA, Coetzee GA, Risch A, Plass C, Casey G, De Biasi M, Carlson C, Duggan D, et al. Principles for the post-GWAS functional characterization of cancer risk loci. Nat Genet. 2011;43:513–518. doi: 10.1038/ng.840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iyer MK, Niknafs YS, Malik R, Singhal U, Sahu A, Hosono Y, Barrette TR, Prensner JR, Evans JR, Zhao S, et al. The landscape of long noncoding RNAs in the human transcriptome. Nat Genet. 2015;47:199–208. doi: 10.1038/ng.3192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pandey GK, Mitra S, Subhash S, Hertwig F, Kanduri M, Mishra K, Fransson S, Ganeshram A, Mondal T, Bandaru S, et al. The risk-associated long noncoding RNA NBAT-1 controls neuroblastoma progression by regulating cell proliferation and neuronal differentiation. Cancer Cell. 2014;26:722–737. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zheng J, Huang X, Tan W, Yu D, Du Z, Chang J, Wei L, Han Y, Wang C, Che X, et al. Pancreatic cancer risk variant in LINC00673 creates a miR-1231 binding site and interferes with PTPN11 degradation. Nat Genet. 2016;48:747–757. doi: 10.1038/ng.3568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25•.Guo H, Ahmed M, Zhang F, Yao CQ, Li S, Liang Y, Hua J, Soares F, Sun Y, Langstein J, et al. Modulation of long noncoding RNAs by risk SNPs underlying genetic predispositions to prostate cancer. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1142–1150. doi: 10.1038/ng.3637. By integrating data from lncRNA transcriptome, GWAS and genomic data, this study identified lncRNAs with prostate cancer susceptibility. By elucidating the top hit PCAT1, the authors demostrated that genetic variation can affect lncRNA expression through its distal regulatory element. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Puente XS, Bea S, Valdes-Mas R, Villamor N, Gutierrez-Abril J, Martin-Subero JI, Munar M, Rubio-Perez C, Jares P, Aymerich M, et al. Non-coding recurrent mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Nature. 2015;526:519–524. doi: 10.1038/nature14666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fujimoto A, Furuta M, Totoki Y, Tsunoda T, Kato M, Shiraishi Y, Tanaka H, Taniguchi H, Kawakami Y, Ueno M, et al. Whole-genome mutational landscape and characterization of noncoding and structural mutations in liver cancer. Nat Genet. 2016;48:500–509. doi: 10.1038/ng.3547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanjana NE, Wright J, Zheng K, Shalem O, Fontanillas P, Joung J, Cheng C, Regev A, Zhang F. High-resolution interrogation of functional elements in the noncoding genome. Science. 2016;353:1545–1549. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf7613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29•.Zhu S, Li W, Liu J, Chen CH, Liao Q, Xu P, Xu H, Xiao T, Cao Z, Peng J, et al. Genome-scale deletion screening of human long non-coding RNAs using a paired-guide RNA CRISPR-Cas9 library. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34:1279–1286. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3715. This study utilizes CRISPR-Cas9 with paired-guide RNA to produce functional deletion of lncRNA. The genome-wide screening approach can be applied to identify functional non-coding elements. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun M, Gadad SS, Kim DS, Kraus WL. Discovery, Annotation, and Functional Analysis of Long Noncoding RNAs Controlling Cell-Cycle Gene Expression and Proliferation in Breast Cancer Cells. Mol Cell. 2015;59:698–711. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marchese FP, Grossi E, Marin-Bejar O, Bharti SK, Raimondi I, Gonzalez J, Martinez-Herrera DJ, Athie A, Amadoz A, Brosh RM, Jr, et al. A Long Noncoding RNA Regulates Sister Chromatid Cohesion. Mol Cell. 2016;63:397–407. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schmitt AM, Garcia JT, Hung T, Flynn RA, Shen Y, Qu K, Payumo AY, Peres-da-Silva A, Broz DK, Baum R, et al. An inducible long noncoding RNA amplifies DNA damage signaling. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1370–1376. doi: 10.1038/ng.3673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Y, He Q, Hu Z, Feng Y, Fan L, Tang Z, Yuan J, Shan W, Li C, Hu X, et al. Long noncoding RNA LINP1 regulates repair of DNA double-strand breaks in triple-negative breast cancer. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2016;23:522–530. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang D, Zhang G, Hu X, Wu L, Feng Y, He S, Zhang Y, Hu Z, Yang L, Tian T, et al. Oncogenic RAS Regulates Long Noncoding RNA Orilnc1 in Human Cancer. Cancer Res. 2017 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmidt K, Joyce CE, Buquicchio F, Brown A, Ritz J, Distel RJ, Yoon CH, Novina CD. The lncRNA SLNCR1 Mediates Melanoma Invasion through a Conserved SRA1-like Region. Cell Rep. 2016;15:2025–2037. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu B, Sun L, Liu Q, Gong C, Yao Y, Lv X, Lin L, Yao H, Su F, Li D, et al. A cytoplasmic NF-kappaB interacting long noncoding RNA blocks IkappaB phosphorylation and suppresses breast cancer metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:370–381. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li C, Wang S, Xing Z, Lin A, Liang K, Song J, Hu Q, Yao J, Chen Z, Park PK, et al. A ROR1-HER3-lncRNA signalling axis modulates the Hippo-YAP pathway to regulate bone metastasis. Nat Cell Biol. 2017;19:106–119. doi: 10.1038/ncb3464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun TT, He J, Liang Q, Ren LL, Yan TT, Yu TC, Tang JY, Bao YJ, Hu Y, Lin Y, et al. LncRNA GClnc1 Promotes Gastric Carcinogenesis and May Act as a Modular Scaffold of WDR5 and KAT2A Complexes to Specify the Histone Modification Pattern. Cancer Discov. 2016;6:784–801. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin A, Li C, Xing Z, Hu Q, Liang K, Han L, Wang C, Hawke DH, Wang S, Zhang Y, et al. The LINK-A lncRNA activates normoxic HIF1alpha signalling in triple-negative breast cancer. Nat Cell Biol. 2016;18:213–224. doi: 10.1038/ncb3295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rupaimoole R, Lee J, Haemmerle M, Ling H, Previs RA, Pradeep S, Wu SY, Ivan C, Ferracin M, Dennison JB, et al. Long Noncoding RNA Ceruloplasmin Promotes Cancer Growth by Altering Glycolysis. Cell Rep. 2015;13:2395–2402. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.11.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Damas ND, Marcatti M, Come C, Christensen LL, Nielsen MM, Baumgartner R, Gylling HM, Maglieri G, Rundsten CF, Seemann SE, et al. SNHG5 promotes colorectal cancer cell survival by counteracting STAU1-mediated mRNA destabilization. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13875. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42••.Lee S, Kopp F, Chang TC, Sataluri A, Chen B, Sivakumar S, Yu H, Xie Y, Mendell JT. Noncoding RNA NORAD Regulates Genomic Stability by Sequestering PUMILIO Proteins. Cell. 2016;164:69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.017. This study uncovered the essential role of lncRNAs in maintaining genome stability and reinforce the implication of lncRNAs in cancer initiation and progression. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jiang R, Tang J, Chen Y, Deng L, Ji J, Xie Y, Wang K, Jia W, Chu WM, Sun B. The long noncoding RNA lnc-EGFR stimulates T-regulatory cells differentiation thus promoting hepatocellular carcinoma immune evasion. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15129. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bussemakers MJ, van Bokhoven A, Verhaegh GW, Smit FP, Karthaus HF, Schalken JA, Debruyne FM, Ru N, Isaacs WB. DD3: a new prostate-specific gene, highly overexpressed in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5975–5979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Panzitt K, Tschernatsch MM, Guelly C, Moustafa T, Stradner M, Strohmaier HM, Buck CR, Denk H, Schroeder R, Trauner M, et al. Characterization of HULC, a novel gene with striking up-regulation in hepatocellular carcinoma, as noncoding RNA. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:330–342. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shao Y, Ye M, Jiang X, Sun W, Ding X, Liu Z, Ye G, Zhang X, Xiao B, Guo J. Gastric juice long noncoding RNA used as a tumor marker for screening gastric cancer. Cancer. 2014;120:3320–3328. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47•.Arun G, Diermeier S, Akerman M, Chang KC, Wilkinson JE, Hearn S, Kim Y, MacLeod AR, Krainer AR, Norton L, et al. Differentiation of mammary tumors and reduction in metastasis upon Malat1 lncRNA loss. Genes Dev. 2016;30:34–51. doi: 10.1101/gad.270959.115. This article describes a preclinical study that using ASO to target highly expressed MALAT1 in a metastasis breast cancer mouse model. Inhibition of MALAT1 by ASO promotes cystic differentiation and decreases cancer cell migration. This study strongly supports the application of MALAT1 inhibitor in breast cancer treatment. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ling H, Fabbri M, Calin GA. MicroRNAs and other non-coding RNAs as targets for anticancer drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:847–865. doi: 10.1038/nrd4140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu SY, Lopez-Berestein G, Calin GA, Sood AK. RNAi therapies: drugging the undruggable. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:240ps247. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Adriaens C, Standaert L, Barra J, Latil M, Verfaillie A, Kalev P, Boeckx B, Wijnhoven PW, Radaelli E, Vermi W, et al. p53 induces formation of NEAT1 lncRNA-containing paraspeckles that modulate replication stress response and chemosensitivity. Nat Med. 2016;22:861–868. doi: 10.1038/nm.4135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qu L, Ding J, Chen C, Wu ZJ, Liu B, Gao Y, Chen W, Liu F, Sun W, Li XF, et al. Exosome-Transmitted lncARSR Promotes Sunitinib Resistance in Renal Cancer by Acting as a Competing Endogenous RNA. Cancer Cell. 2016;29:653–668. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McCleland ML, Mesh K, Lorenzana E, Chopra VS, Segal E, Watanabe C, Haley B, Mayba O, Yaylaoglu M, Gnad F, et al. CCAT1 is an enhancer-templated RNA that predicts BET sensitivity in colorectal cancer. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:639–652. doi: 10.1172/JCI83265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lin A, Hu Q, Li C, Xing Z, Ma G, Wang C, Li J, Ye Y, Yao J, Liang K, et al. The LINK-A lncRNA interacts with PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 to hyperactivate AKT and confer resistance to AKT inhibitors. Nat Cell Biol. 2017;19:238–251. doi: 10.1038/ncb3473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54••.Hon CC, Ramilowski JA, Harshbarger J, Bertin N, Rackham OJ, Gough J, Denisenko E, Schmeier S, Poulsen TM, Severin J, et al. An atlas of human long non-coding RNAs with accurate 5′ ends. Nature. 2017;543:199–204. doi: 10.1038/nature21374. This study provides a great resource of lncRNA expression profies and potentially functional lncRNAs in major human primary cell types and tissues. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sauvageau M, Goff LA, Lodato S, Bonev B, Groff AF, Gerhardinger C, Sanchez-Gomez DB, Hacisuleyman E, Li E, Spence M, et al. Multiple knockout mouse models reveal lincRNAs are required for life and brain development. Elife. 2013;2:e01749. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]