Abstract

Objective

To evaluate associations between iron supplementation and iron deficiency (ID) in infancy and internalizing, externalizing, and social problems in adolescence.

Study design

The study is a follow-up of infants as adolescents from working-class communities around Santiago, Chile who participated in a preventive trial of iron supplementation at 6 months. Inclusionary criteria included birth weight >3.0 kg, healthy singleton term birth, vaginal delivery, and a stable caregiver. Iron status was assessed at 12 and 18 months. At 11–17 years, internalizing, externalizing, and social problems were reported by 1,018 adolescents with the Youth Self Report (YSR) and by parents with the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL).

Results

Adolescents who received iron supplementation in infancy had greater self-reported attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) but lower parent-reported conduct disorder symptoms than those who did not (Ps < .05). ID with or without anemia at 12 or 18 months predicted greater adolescent behavior problems compared with iron sufficiency: more adolescent-reported anxiety and social problems, and parent-reported social, PTSD, ADHD, oppositional defiant, conduct, aggression, and rule breaking problems (Ps < .05). The threshold was ID with or without anemia for each of these outcomes.

Conclusion

ID with or without anemia in infancy was associated with increased internalizing, externalizing, and social problems in adolescence.

Keywords: Iron deficiency anemia, behavior problems, adolescence, Chile

Iron deficiency (ID) in infancy is associated with poorer cognitive functioning, behavioral disturbances, emotional difficulties, and lower motor scores (1), with long-term effects despite iron therapy at diagnosis (2). The longest follow-up study of early ID assessed young adults in Costa Rica who were treated for ID that was identified in the 2nd year of life (termed “chronic” ID). When participants were 11–14 years of age, parents and teachers reported increased anxiety/depression, attention and social problems for those with chronic ID in infancy (3). At 25 years, these young adults reported poorer emotional health, including more negative emotions and greater dissociation/detachment than those who did not have chronic ID in infancy (2). In this study, behavior problems in early adolescence were an important mediator of emotional health at 25 years (2), indicating the persistence of problems following ID in infancy.

It is unknown whether associations between infant ID and emotion/behavior problems generalize to other populations or apply to infants with less chronic ID. To address these questions, we analyzed data from a large cohort of Chilean adolescents who participated as infants in an iron deficiency anemia (IDA) preventive trial. At 10 years, children who received iron supplementation in the trial showed more adaptive behaviors, such as greater cooperation, confidence, persistence, and positive affect (4). In adolescence, we predicted that iron supplementation in infancy would also be associated with more adaptive behaviors. We expected that individuals with ID in infancy would report more behavior problems than those who were iron-sufficient (IS) in infancy. However, we did not have a prediction about whether IDA or ID without anemia would be the threshold for symptoms.

Methods

This study was a follow-up of a project in Chile that included a clinical trial of preventing IDA in infancy. Infants were enrolled from 1991–1996 at clinics in 4 working-class communities outside of Santiago, Chile. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were chosen to enroll healthy infants without common risk factors for developmental or behavioral problems. Inclusion criteria include birth weight ≥ 3.0 kg, singleton term birth, vaginal delivery, stable caregiver, and residence in the communities. Exclusion criteria included major congenital anomaly, birth complications, phototherapy, hospitalization longer than 5 days, illness, or iron therapy, another infant less than 12 months of age in the household, day care for the infant, or a caregiver who was illiterate or psychotic (5).

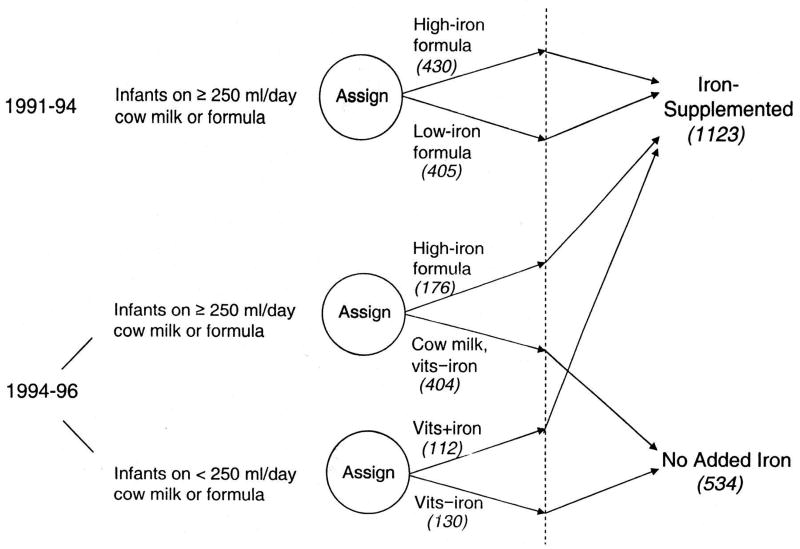

At 6 months of age, qualifying infants were randomized in the double-blind preventive trial to receive high-iron formula (12 mg/L) or low-iron formula (2.3 mg/L) in the initial years of the study. Infants needed to be consuming at least 250 mL of formula or cow milk per day to be entered in the trial. From 1994–1996, this requirement was dropped, as national campaigns greatly increased breastfeeding rates. In addition, a no-added-iron group replaced the low-iron group, as originally planned (5). Infants consuming ≥ 250 mL/day of cow milk or formula were randomized to high-iron formula or cow milk without added iron. Infants who were taking < 250 mL/day of cow milk or formula were randomized to liquid vitamins with iron (10 mg/day) or without iron (study diagram shown in Figure 1 [available at www.jpeds.com]). A total of 1,657 infants completed the preventive trial. Supplementation significantly reduced ID and IDA at 12 months and improved social behavior in infancy and at 10 years of age (4, 5). More details on study design and preventive trial results are described elsewhere (4). Written informed consent was obtained at each assessment, and child assent was obtained from 10 years on. A flowchart of the timeline and measures related to the current analyses is included in Figure 2 (available at www.jpeds.com). The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the corresponding universities.

Figure 1.

(online). Changes in study design. Attrition after group assignment (dotted line) was 7.8%. Of the final sample of 1657 infants who completed the study, 835 were enrolled in the initial phase, and 822 were enrolled thereafter. Analyses of outcomes compared all infants who received iron (the iron-supplemented group) with those who did not (the no-added-iron group). Further analyses compared the high-iron and low-iron supplemented groups. N’s in each original group and the final analysis are shown in parentheses. Reproduced with permission from Pediatrics, 112, 846-54, Copyright ©2003 by the AAP.

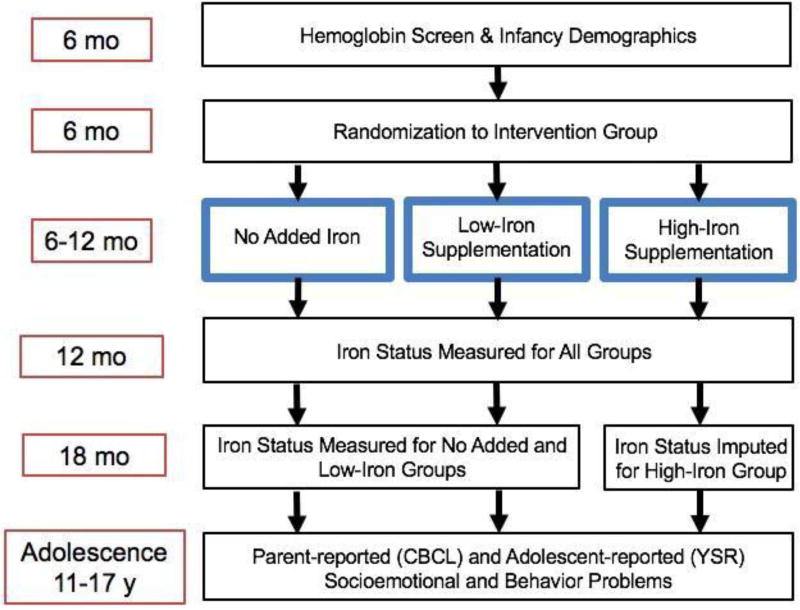

Figure 2.

(online). Flowchart of timeline with measures relevant to the current study. The left side indicates the time point for the measure or intervention, and the blue boxes indicate the iron supplementation group to which individuals were assigned. The only difference in measures between the 3 intervention groups is that the high-iron supplementation group did not have iron status measured at 18 months and instead had this data imputed.

Iron status

All infants received a capillary hemoglobin (Hb) screening at 6 months. Infants with screening Hb ≤ 103 g/L and the next non-anemic infant received a venipuncture. Infants with IDA at 6 months (venous Hb ≤ 100 g/L (6) and 2 out of 3 abnormal measures as detailed below) and the next infant with venous Hb > 115 g/L were excluded from the preventive trial and followed in a separate study. At 12 months, a venous blood sample was collected for all participants in the preventive trial. At 18 months, participants in the low-iron and no-added-iron groups received another venipuncture. Missing iron measures at 18 months for individuals who did not receive a venipuncture were imputed using multiple imputation techniques (7). Anemia at 12 and 18 months was defined as Hb < 110 g/L (8). ID was defined as 2 of 3 iron measures in the abnormal range (9): mean corpuscular volume (MCV) < 70 fL (10), free erythrocyte protoporphyrin (FEP) > 100 µg/dL red blood cells (11), and ferritin < 12 µg/L (11). Infants with IDA at any age received iron therapy. Based on each individual’s poorest iron status at 12 or 18 months, we classified iron status as IDA, ID without anemia, or iron-sufficient (IS, i.e., not having IDA or ID without anemia at 12 and 18 months). We could not do so at 6 months because only 321 infants had an iron status assessment based on venipuncture. By 18 months, IDA was greatly reduced due to supplementation, slower growth, and a more diverse diet. After infancy, IDA was uncommon in the sample, with less than 1% IDA at the 5- and 10-year follow-ups and 2.5% at the adolescent assessment.

Adolescent follow-up

Youth Self Report and Child Behavior Checklist

All parents reported their adolescent’s symptoms using the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (12). All adolescents reported symptoms using the Youth Self Report (YSR), the self-report version of the Child Behavior Checklist. Both were administered in Spanish. The YSR and CBCL are widely-used, valid, and reliable instruments for assessing symptoms in children and adolescents (12, 13). Internalizing symptoms were assessed by the following scales: depressive problems, anxiety problems, and post-traumatic stress (PTSD) problems. Externalizing problems were assessed with the oppositional defiant problems, conduct problems, rule breaking, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) problems, and aggressive behavior scales. Social problems were assessed using the social problems scale. Correlations between the parent and adolescent report for each subscale ranged from r = 0.16 for anxiety problems to r = 0.42 for rule breaking (ps < 0.001). T-scores were used in analyses. Scales that were skewed (skewness value > 1) were log-transformed prior to analysis; specifically, parent-reported rule breaking and conduct problems and adolescent-reported social, depressive, PTSD, aggressive, ADHD, and oppositional defiant problems were log-transformed.

Potential covariates

To consider socioeconomic status (SES) effects, SES was measured in infancy using a modified Graffar Index (14). Maternal age (in years), number of life stressors in the past year, birth weight and length, gestational age, and growth from 0–6 months in height and weight were also reported at the infancy assessment (15). The Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment (HOME) measured home support for child development (16). Because exclusion criteria changed during enrollment regarding breastfeeding, we controlled for feeding in infancy by including the mean daily formula/milk consumption (mL/day) between 6 and 12 months as a covariate. This variable was inversely correlated with all breastfeeding measures, i.e., weaning age (if weaned), nursing at one year, and age at first bottle. Data on formula/milk consumption and breastfeeding was obtained from mothers at weekly home visits. Family stress in infancy was measured by a modified Social Readjustment Rating Scale (17). Some participants were enrolled at 12 or 18 months in a study component examining neuromaturation in IDA compared with IS infants; they all received medicinal iron (9). Participation (with receipt of medicinal iron) was coded as 0 = not in neuromaturation study, 1 = in neuromaturation study. For control variables, missing values were imputed using multiple imputation techniques (7).

Statistical analyses

Analyses were conducted using SPSS version 24. To test for group differences in background characteristics that might require covariate control, t-tests and analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were used to examine continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) were conducted to test for differences in socioemotional functioning and behavior by 1) iron supplementation (any iron supplementation vs. no added iron; high- vs. low-iron supplementation) and 2) severity of ID at 12–18 months (IS, ID, IDA). First, analyses compared iron supplementation vs. no added iron on each of the dependent variables: depressive, anxiety, post-traumatic stress, aggressive, oppositional defiant, conduct, rule breaking, ADHD, and social problems. Secondary analyses compared the high-iron and low-iron groups on outcomes. Next, differences in the dependent variables by iron status in infancy were tested. Planned comparisons tested whether the threshold for effects was ID (ID or IDA vs IS) or IDA (IDA vs ID or IS). Follow-up analyses were conducted to assess whether effects were stronger for the composite variable considering 12- and 18-month iron status jointly or 12- or 18-month iron status separately. Covariates that differed by group were added to models, and the backward elimination procedure was used, excluding covariates with p > 0.05 until the most parsimonious model was obtained. Alpha level was set at .05 for statistical significance.

Results

In adolescence, 1018 participants (49.0% female) completed the YSR, and 893 parents completed the CBCL. Adolescents who completed this session did not differ from cohort participants who did not on infant iron status, sex, breastfeeding, family stress, HOME score, maternal age, weight or length at birth, gestational age, or growth in weight or length between 0–6 months of age, Ps > 0.05. However, adolescents who participated in this follow-up were more likely have higher socioeconomic status than non-participants, Ps < 0.05. Individuals in the no-added-iron group and those who participated in the neuromaturation study were more likely to participate in adolescence, Ps < 0.05. Participants averaged 14.3 years of age (SD = 1.6): 31.5% 11–13 years, 54.7% 14–15 years, and 19.8% 16–17 years. There were 410 adolescents from the high-iron group, 227 from the low-iron group, and 361 from the no-added-iron group. A total of 135 adolescents had IDA at 12 or 18 months, and 310 had ID without anemia at one age or the other; 545 were IS at both time points in infancy. Iron supplementation groups (any supplementation vs. no added iron) differed by age at testing in adolescence, sex, birth weight, birth length, maternal stress, SES in infancy, formula intake, and breastfeeding at 12 months (Table I; available at www.jpeds.com). Iron status groups differed by age at testing in adolescence, sex, SES in infancy, maternal age at child’s birth, formula intake, breastfeeding at 12 months, and iron supplementation group.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics.

| Iron- Supplemented |

No-Added-Iron | P-value | Iron Sufficiency |

ID without Anemia |

IDA | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N(%) | 657 | 361 | 545 (55.1%) | 310 (31.3%) | 135 (13.3%) | ||

| Participant age (y) | 14.9 (1.5) | 13.3 (1.4) | <0.001 | 14.5 (1.6) | 14.3 (1.6) | 13.7 (1.5) | <0.001 |

| Sex (% female) | 342 (52.1%) | 157 (43.5%) | 0.01 | 285 (52.3%) | 159 (51.3%) | 41 (30.4%) | <0.001 |

| Birth weight (g) | 3530.0 (352.0) | 3591.4 (385.8) | 0.01 | 3564.8 (351.7) | 3530.8 (377.4) | 3531.2 (379.7) | 0.35 |

| Birth length (cm) | 50.6 (1.7) | 50.9 (1.6) | 0.004 | 50.7 (1.7) | 50.7 (1.8) | 50.8 (1.7) | 0.93 |

| Maternal age (y) | 26.4 (6.0) | 25.9 (6.1) | 0.22 | 26.8 (6.1) | 26.0 (5.9) | 24.7 (5.9) | 0.001 |

| Mother’s education (y) | 9.4 (2.8) | 9.6 (2.6) | 0.48 | 9.5 (2.7) | 9.5 (2.8) | 9.1 (2.7) | 0.32 |

| Graffar (SES) | 27.6 (6.2) | 26.8 (6.5) | 0.049 | 27.0 (6.1) | 27.4 (6.5) | 28.8 (6.8) | 0.01 |

| HOME score | 30.5 (4.7) | 30.3 (4.8) | 0.55 | 30.5 (4.7) | 30.2 (4.6) | 30.6 (4.9) | 0.54 |

| Maternal stress | 4.8 (2.6) | 4.5 (2.8) | 0.049 | 4.7 (2.6) | 4.6 (2.8) | 4.9 (2.6) | 0.50 |

| Formula/milk intake (average mL/day) | 566.9 (232.9) | 404.3 (241.0) | <0.001 | 530.6 (240.6) | 515.1 (256.4) | 447.9 (235.3) | 0.002 |

| Breastfeeding at 12 months | 182 (28.6%) | 155 (43.5%) | <0.001 | 162 (30.6%) | 101 (33.3%) | 57 (42.5%) | 0.02 |

| Supplementation group | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| High iron | 430 (65.4%) | 0 (0%) | 302 (55.4%) | 101 (32.6%) | 16 (11.9%) | ||

| Low iron | 227 (34.6%) | 0 (0%) | 124 (22.8%) | 85 (27.4%) | 18 (13.3%) | ||

| No added iron | 0 (0%) | 361 (100%) | 119 (21.8%) | 124 (40.0%) | 101 (74.8%) |

Note. Values are n (%) for categorical variables and mean (SD) for continuous variables. Percentages calculated for those with non-missing data on each variable. P-values derived by ANOVA or chi-square tests indicate whether there were significant differences by infant iron supplementation or iron status group. Differences in groups by breastfeeding were due to the change in inclusion criteria during the study.

Effects of iron supplementation in infancy

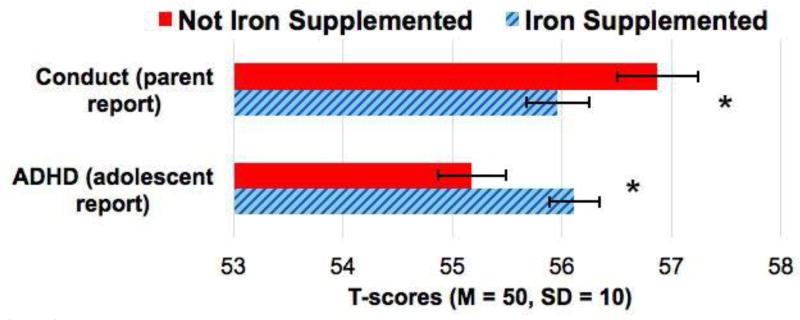

Parent report

Conduct problems were significantly lower in the iron-supplemented vs. no-added-iron group, F(1, 869) = 3.92, P = 0.048. Other scales were not associated with supplementation, Ps > 0.05 (Table 2 and Figure 3). Following the approach in analyzing 10-year outcomes (18), we considered whether Hb levels at 6 months moderated the effect of iron supplementation on behavior problems. The interaction between 6-month Hb and iron supplementation did not predict conduct problems, t(892) = 0.07, P = 0.95.

Table 2.

T-scores for Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) and Youth Self-Report (YSR) subscales by infancy iron supplementation

| Infancy Iron Supplementation |

Parent Report: CBCL Mean |

CBCL 95% CI |

Youth Report: YSR Mean |

YSR 95% CI |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social problems | Iron | 61.7 | 61.1, 62.3 | 56.9 | 56.4, 57.4 |

| No iron | 62.2 | 61.4, 63.0 | 56.2 | 55.5, 56.8 | |

| Depressive | Iron | 61.9 | 61.2, 62.7 | 57.0 | 56.4, 57.5 |

| No iron | 61.6 | 60.7, 62.6 | 57.0 | 56.3, 57.7 | |

| Anxiety | Iron | 62.6 | 61.9, 63.3 | 57.6 | 57.1, 58.1 |

| No iron | 63.1 | 62.2, 64.0 | 56.9 | 56.3, 57.6 | |

| Post-traumatic stress | Iron | 61.5 | 60.9, 62.2 | 57.2 | 56.7, 57.8 |

| No iron | 61.6 | 60.7, 62.5 | 56.6 | 55.9, 57.3 | |

| ADHD | Iron | 58.8 | 58.2, 59.4 | 56.1** | 55.7, 56.6 |

| No iron | 59.0 | 58.2, 59.8 | 55.2 | 54.6, 55.8 | |

| Oppositional defiant | Iron | 58.0 | 57.3, 58.6 | 56.1 | 55.6, 56.6 |

| No iron | 58.5 | 57.8, 59.3 | 55.4 | 54.7, 56.1 | |

| Conduct | Iron | 56.0* | 55.4, 56.5 | 57.4 | 56.8, 58.0 |

| No iron | 56.9 | 56.2, 57.6 | 57.8 | 57.0, 58.5 | |

| Aggressive | Iron | 59.5 | 58.8, 60.2 | 57.2 | 56.7, 57.8 |

| No iron | 60.3 | 59.4, 61.2 | 56.6 | 55.8, 57.3 | |

| Rule breaking | Iron | 56.2 | 55.6, 56.7 | 56.8 | 56.3, 57.3 |

| No iron | 56.4 | 55.7, 57.0 | 56.3 | 55.7, 57.0 |

Note. Means and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for T-scores by iron supplementation in infancy. The supplementation group included the high-iron and low-iron groups while the no supplementation group contained only the no added iron group. Significance values were calculated using the log-transformed values for skewed variables but presented as T-scores here.

p≤0.05,

p≤0.01,

p≤0.001.

Figure 3.

T-scores for the self-reported ADHD and parent-reported conduct scales by supplementation group (iron supplementation vs. no added iron). *P<0.05.

Adolescent report

Adolescents who received iron supplementation in infancy reported higher ADHD symptoms, F(1, 1015) = 6.10, P = 0.01, than adolescents who did not receive iron supplementation. Other scales were not associated with supplementation, Ps > 0.05 (Table 2). The interaction between 6-month Hb and iron supplementation did not predict ADHD symptoms, t(1017) = −1.20, P = 0.23.

High-iron vs. low-iron

There were no differences by high- vs. low-iron supplementation for any of the parent- or adolescent-reported scales, Ps > 0.05 (Table 3; available at www.jpeds.com).

Table 3.

T-scores for Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) and Youth Self-Report (YSR) subscales by high iron vs. low iron supplementation in infancy

| Iron supplementation level in infancy |

Parent Report: CBCL Mean |

CBCL 95% CI |

Youth Report: YSR Mean |

YSR 95% CI |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social problems | High | 61.9 | 61.2, 62.7 | 56.9 | 56.3, 57.5 |

| Low | 61.6 | 60.5, 62.7 | 56.8 | 56.0, 57.7 | |

| Depressive | High | 62.1 | 61.2, 62.9 | 57.3 | 56.6, 57.9 |

| Low | 62.6 | 61.4, 63.9 | 57.3 | 56.4, 58.2 | |

| Anxiety | High | 62.6 | 61.7, 63.5 | 57.4 | 56.9, 58.0 |

| Low | 62.8 | 61.6, 64.1 | 57.8 | 57.0, 58.6 | |

| Post-traumatic stress | High | 61.3 | 60.4, 62.1 | 57.2 | 56.6, 57.8 |

| Low | 62.2 | 61.0, 63.4 | 57.3 | 56.4, 58.1 | |

| ADHD | High | 59.0 | 58.3, 59.7 | 56.1 | 55.6, 56.7 |

| Low | 58.8 | 57.8, 59.8 | 56.1 | 55.3, 56.9 | |

| Oppositional defiant | High | 57.6 | 56.9, 58.3 | 56.3 | 55.6, 56.9 |

| Low | 58.8 | 57.7, 59.8 | 56.0 | 55.1, 56.9 | |

| Conduct | High | 56.0 | 55.3, 56.7 | 57.7 | 57.0, 58.3 |

| Low | 56.5 | 55.5, 57.4 | 57.6 | 56.6, 58.6 | |

| Aggressive | High | 59.2 | 58.4, 60.1 | 57.5 | 56.8, 58.2 |

| Low | 60.3 | 59.1, 61.5 | 57.2 | 56.3, 58.2 | |

| Rule breaking | High | 56.2 | 55.6, 56.8 | 56.9 | 56.3, 57.5 |

| Low | 56.7 | 55.7, 57.6 | 57.4 | 56.5, 58.2 |

Note. Means and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for T-scores by iron supplementation level in infancy: high-iron or low-iron. Significance values were calculated using the log-transformed values for skewed variables but presented as T-scores here.

p≤0.05,

p≤0.01

p≤0.001.

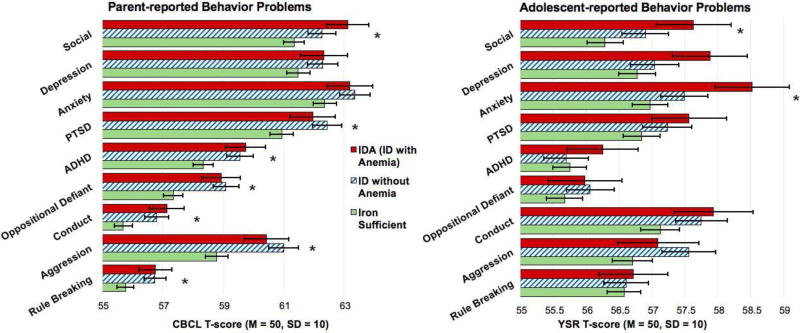

Severity of ID in infancy

Parent report

ID in infancy was associated with greater parent-reported social problems in adolescence, with ID as the threshold for problems, contrast estimate = 2.71, 95% CI: 0.58–4.85, P = 0.01 (Figure 4 and Table 4). ID was also the threshold for greater ADHD problems, estimate = 2.63, 95% CI: 0.60–4.67, P = 0.010, oppositional defiant problems, estimate = 3.33, 95% CI: 1.35–5.31, P = 0.001, conduct problems, estimate = 0.05, 95% CI: 0.02–0.08, P = 0.004, aggressive problems, estimate = 3.86, 95% CI: 1.56–6.16, P = 0.001, rule breaking problems, estimate = 0.04, 95% CI: 0.01–0.07, P = 0.02, and PTSD symptoms, estimate = 2.52, 95% CI: 0.22–4.83, P = 0.03. Iron status in infancy was not associated with parent-reported depressive or anxiety symptoms, Ps > 0.05.

Figure 4.

T-scores for each problem scale by infant iron status group. ID = iron deficiency, IDA = iron deficiency anemia. *P<0.05.

Table 4.

T-scores for Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) and Youth Self-Report (YSR) subscales by infancy ID

| Infancy Iron Status | Parent Report: CBCL Mean |

CBCL 95% CIa |

Youth Report: YSR Mean |

YSR 95% CI |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social problems | IS | 61.3* | 60.7, 62.0 | 56.3* | 55.7, 56.8 |

| ID | 62.3 | 61.4, 63.2 | 56.9 | 56.2, 57.6 | |

| IDA | 63.1 | 61.8, 64.5 | 57.6 | 56.5, 58.7 | |

| Depressive | IS | 61.5 | 60.7, 62.2 | 56.8 | 56.2, 57.3 |

| ID | 62.3 | 61.3, 63.3 | 57.0 | 56.3, 57.8 | |

| IDA | 62.3 | 60.8, 63.8 | 57.9 | 56.8, 59.0 | |

| Anxiety | IS | 62.4 | 61.6, 63.1 | 57.0* | 56.4, 57.5 |

| ID | 63.4 | 62.4, 64.4 | 57.5 | 56.8, 58.2 | |

| IDA | 63.2 | 61.7, 64.7 | 58.5 | 57.4, 59.6 | |

| Post-traumatic stress | IS | 60.9* | 60.2, 61.7 | 56.8 | 56.3, 57.4 |

| ID | 62.4 | 61.5, 63.4 | 57.2 | 56.5, 58.0 | |

| IDA | 62.0 | 60.5, 63.4 | 57.6 | 56.4, 58.7 | |

| ADHD | IS | 58.3** | 57.7, 59.0 | 55.7 | 55.2, 56.3 |

| ID | 59.6 | 58.7, 60.4 | 55.7 | 55.0, 56.4 | |

| IDA | 59.7 | 58.4, 61.0 | 56.3 | 55.2, 57.3 | |

| Oppositional defiant | IS | 57.4*** | 56.7, 58.0 | 55.7 | 55.1, 56.2 |

| ID | 59.1 | 58.3, 59.9 | 56.1 | 55.3, 56.8 | |

| IDA | 58.9 | 57.7, 60.2 | 56.0 | 54.9, 57.1 | |

| Conduct | IS | 55.7** | 55.1, 56.3 | 57.1 | 56.5, 57.7 |

| ID | 56.8 | 56.0, 57.6 | 57.7 | 57.0, 58.5 | |

| IDA | 57.1 | 56.0, 58.3 | 57.9 | 56.8, 59.1 | |

| Aggressive | IS | 58.8*** | 58.0, 59.5 | 56.7 | 56.1, 57.3 |

| ID | 61.0 | 60.0, 62.0 | 57.6 | 56.8, 58.4 | |

| IDA | 60.4 | 59.0, 61.9 | 57.1 | 55.9, 58.3 | |

| Rule breaking | IS | 55.8* | 55.2, 56.3 | 56.6 | 56.1, 57.1 |

| ID | 56.7 | 56.0, 57.5 | 56.8 | 56.1, 57.5 | |

| IDA | 56.8 | 55.7, 57.8 | 56.5 | 55.5, 57.5 |

Note. Means and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for T-scores by iron status.

IS = iron sufficient. ID = iron deficiency without anemia. IDA = iron deficiency anemia. Significance values were calculated using the log-transformed values for skewed variables but presented as T-scores here.

IS group differs from the combined IDA and non-anemic ID group,

p≤0.05,

p≤0.01

p≤0.001.

Adolescent report

ID in infancy was associated with greater self-reported anxiety symptoms, contrast estimate = 2.07, 95% CI: 0.31–3.82, P = 0.02, and greater social problems, contrast estimate = 0.03, 95% CI: 0.003–0.06, P = 0.03, with the threshold at ID without anemia. ID in infancy was not associated with depressive, PTSD, ADHD, oppositional defiant, conduct, aggressive, or rule breaking problems, Ps > 0.10.

Follow-up analyses

The composite measure of 12- and 18-month iron status was a better overall predictor of adolescent parent- and self-reported outcomes than 12- or 18-month iron status alone.

Discussion

This study confirms in a much larger cohort what was found in the earlier Costa Rican study (3). Specifically, results indicate that ID in infancy is associated with increased behavior problems later on. In this Chilean cohort, participants with ID in infancy were reported to have greater social, anxiety, ADHD, PTSD, aggressive, conduct, oppositional defiant, and rule breaking problems in adolescence. These adverse effects are not driven solely by IDA—the associations were significant for ID, with or without anemia. This observation is concerning, because ID without anemia is not usually detected. Compared with the Costa Rican cohort (3), Chilean participants were iron-supplemented or treated earlier in infancy and thus had less chronic ID, indicating that effects can still be observed with less chronic ID and earlier treatment.

In line with the more adaptive behaviors we observed at 10 years for those who received iron supplementation in infancy (4), the iron-supplemented group in the current analyses had lower parent-reported conduct problems than the no-added-iron group. However, unlike the 10-year assessment, adolescents who received iron supplementation in infancy reported greater ADHD symptoms than adolescents who did not receive iron supplementation in infancy. These effects were not moderated by 6-month Hb status. These results could suggest opposing effects of iron supplementation on different domains or by different reporters. As there were only two scales that were associated with iron supplementation, and their effects were not consistent, these results need to be replicated and should be considered cautiously.

In contrast to adolescence, at 10 years there were no associations between ID in infancy and total problems, internalizing, withdrawn, anxious/depressed, and aggressive problems after covariate control (4). Those results differ from our current findings of greater parent- and adolescent-reported problems for those who were ID in infancy after covariate control. It is possible that associations between early ID and behavior/emotional problems strengthen or become more apparent in adolescence.

Adolescence is the first time period in this longitudinal study that participants reported their own mental health and behavior problems. Self-report was not obtained prior to adolescence, as earlier waves relied on parent and observer reports. It is particularly interesting that socioemotional and behavioral outcomes that were reported by caregivers or observed by experimenters at other time points (4, 5) were now being observed by the adolescents themselves. It is important to note, however, that parents reported more externalizing problems like aggression in their adolescents following infant ID, and adolescents themselves reported more internalizing problems, such as anxiety. These differences could be due to parents being better able to assess their adolescents’ externalizing behaviors and adolescents being better able to assess their own internal states. Adolescents could also consider externalizing behaviors to be more normative and thus underreport them, and parents might be more bothered by externalizing behaviors than the adolescents, leading to discrepancies. Interestingly, both parents and adolescents reported greater social problems for those who had ID at either 12 or 18 months, controlling for covariates.

ID in infancy may influence socioemotional development in adolescence through neurobiological and psychosocial pathways. Alterations in the synthesis and function of several neurotransmitter systems, particularly monoamines, may contribute to socioemotional and behavioral problems (19). A related potential mechanism that could account for the long-term alterations reported here involves critical or sensitive periods of brain development (20). The concept is that insults during specific periods of development permanently change brain structure and/or the functioning of associated circuitry. The functional isolation hypothesis should also be considered, that is, infants with ID are warier and engage less with caregivers, and caregivers in turn give them less developmentally supportive interaction (21–23). Over time, these children receive less environmental and social stimulation, which exacerbates problems later in life (23). These mechanisms are not mutually exclusive. Each may contribute to the socioemotional and behavioral problems reported in adolescents who experienced ID in infancy.

This study had strengths and limitations to be considered in interpreting the results. This large adolescent cohort has been followed since 6 months of age with repeated measurements of iron status, behavior, and socioemotional functioning. Although many mother- and family-related factors were measured, unmeasured variables may also contribute to group differences, such as other environmental exposures. Likewise, prenatal and postnatal stressors that were not captured by our measures may have influenced early brain development and nutritional status, which could be another factor associated with both ID and socioemotional development. Iron status was measured in detail, but co-occurring micronutrient deficiencies cannot be ruled out and could have contributed to the current findings. Iron status at birth was unknown, and fetal-neonatal ID could contribute to observed outcomes (24). Likewise, iron status at 6 months was not determined for most infants. The sample was limited to healthy, well-nourished term infants with good access to health care and literate parents. Because our sample was advantaged in a number of ways, results may not generalize to other settings. Although the infants were healthy at the time of the iron assessment, we did not collect any markers of infection or inflammation, so we cannot be certain that these factors did not contribute to the results. The study sample is not ideal for understanding specific timing of associations with ID during infancy. As infants with IDA at any time point were treated with iron and the iron-supplemented groups received iron from 6–12 months, there were few infants with chronic ID. Future studies are needed to better address questions of timing and chronicity. The analyses included extensive covariate control, but a causal connection cannot be inferred. Our findings may not generalize to other populations due to the intensive nature of the intervention in infancy and the greater likelihood for those of lower SES to drop out of the study. In addition, Chile has undergone a nutrition transition coinciding with its improved economy, which has lowered its rate of undernutrition and increased its rate of obesity (25). Due to this socioeconomic and cultural transition, caution is needed when assessing applicability to other settings. Likewise, the sample was relatively homogenous in race/ethnicity and geographic area, which limits generalizability to other samples. Thus, replication in other large, diverse samples is needed.

Acknowledgments

Funded by R01HD14122 (PI: B.L.), R01HD33487 (PI: B.L. and S.G.), R01DA021181 (PI: J.D.), R01HL088530 (PI: S.G.), T32DK071212 to J.D., and F32HD088029 (PI: J.D.).

Abbreviations

- Hb

hemoglobin

- ADHD

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

- PTSD

post-traumatic stress disorder

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Lozoff B, Beard J, Connor J, Felt B, Georgieff M, Schallert T. Long-lasting neural and behavioral effects of iron deficiency in infancy. Nutrition Reviews. 2006;64:S34–S43. doi: 10.1301/nr.2006.may.S34-S43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lozoff B, Smith JB, Kaciroti N, Clark KM, Guevara S, Jimenez E. Functional significance of early-life iron deficiency: outcomes at 25 years. J Pediatr. 2013;163:1260–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lozoff B, Jimenez E, Hagen J, Mollen E, Wolf AW. Poorer behavioral and developmental outcome more than 10 years after treatment for iron deficiency in infancy. Pediatrics. 2000;105:E51–E. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.4.e51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lozoff B, Castillo M, Clark KM, Smith JB, Sturza J. Iron supplementation in infancy contributes to more adaptive behavior in 10-year-old children. Journal of Nutrition. 2014;144:838–45. doi: 10.3945/jn.113.182048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lozoff B, De Andraca I, Castillo M, Smith J, Walter T, Pino P. Behavioral and developmental effects of preventing iron-deficiency anemia in healthy full-term infants. Pediatrics. 2003;112:846–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nathan D, Orkin S. Nathan & Oski's hematology of infancy and childhood. 5. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. Iron deficiency anaemia: assessment, prevention and control: a guide for programme managers. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roncagliolo M, Garrido M, Walter T, Peirano P, Lozoff B. Evidence of altered central nervous system development in infants with iron deficiency anemia at 6 mo: delayed maturation of auditory brainstem responses. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 1998;68:683–90. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/68.3.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dallman PR, Reeves JD, Driggers DA, Lo YE. Diagnosis of iron deficiency: the limitations of laboratory tests in predicting response to iron treatment in 1-year-old infants. The Journal of pediatrics. 1981;99:376–81. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(81)80321-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deinard A, Schwartz S, Yip R. Developmental changes in serum ferritin and erythrocyte protoporphyrin in normal (nonanemic) children. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 1983;38:71–6. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/38.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Achenbach T, Edelbrock C. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/42013;18 and Revised Child Behavior Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Achenbach T, Rescorla L. Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms and profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alvarez M, Muzzo S, Ivanovic D. Escala para la medicion del nivel socioeconomico en el area de la salud. Revista Medica de Chile. 1985;113:243–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weinraub M, Wolf B. Stress, social supports and parent-child interactions: Similarities and differences in single-parent and two-parent families. In: Boukydis I, Zachariah CF, editors. Research on support for parents and infants in the postnatal period. Norwood, New Jersey; Ablex Publishing Corporation; 1987. pp. 114–35. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caldwell BM, Bradley RH. Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment (Revised Edition) Little Rock: University of Arkansas; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holmes TH, Rahe RH. The Social Readjustment Rating Scale. J Psychosom Med. 1967;11:213–8. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(67)90010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lozoff B, Castillo M, Clark KM, Smith JB. Iron-fortified vs low-iron infant formula: developmental outcome at 10 years. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2012;166:208–15. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beard JL, Connor JR. Iron status and neural functioning. Ann Rev Nutr. 2003;23:41–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.23.020102.075739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hensch TK. Critical period regulation. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:549–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lozoff B, Klein NK, Nelson EC, McClish DK, Manuel M, Chacon ME. Behavior of infants with iron deficiency anemia. Child development. 1998;69:24–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lozoff B, Clark KM, Jing Y, Armony-Sivan R, Angelilli ML, Jacobson SW. Dose-response relationships between iron deficiency with or without anemia and infant social-emotional behavior. Journal of Pediatrics. 2008;152:696–702. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.09.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.East P, Lozoff B, Blanco E, Delker E, Delva J, Encina P, et al. Infant iron deficiency, child affect, and maternal unresponsiveness: Testing the long-term effects of functional isolation. Dev Psychopathol. doi: 10.1037/dev0000385. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lozoff B, Georgieff MK. Iron Deficiency and Brain Development. Seminars in Pediatric Neurology. 2006;13:158–65. doi: 10.1016/j.spen.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Albala C, Vio F, Kain J, Uauy R. Nutrition transition in Chile: determinants and consequences. Public health nutrition. 2002;5:123–8. doi: 10.1079/PHN2001283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]