Abstract

Diabetes is a complex immune disorder that requires extensive medical care beyond glycemic control. Recently, the prevalence of diabetes, particularly type 1 diabetes (T1D), has significantly increased from 5% to 10%, and this has affected the health-associated complication incidences in children and adults. The 2012 statistics by the American Diabetes Association reported that 29.1 million Americans (9.3% of the population) had diabetes, and 86 million Americans (age ≥20 years, an increase from 79 million in 2010) had prediabetes. Personalized glucometers allow diabetes management by easy monitoring of the high millimolar blood glucose levels. In contrast, non-glucose diabetes biomarkers, which have gained considerable attention for early prediction and provide insights about diabetes metabolic pathways, are difficult to measure because of their ultra-low levels in blood. Similarly, insulin pumps, sensors, and insulin monitoring systems are of considerable biomedical significance due to their ever-increasing need for managing diabetic, prediabetic, and pancreatic disorders. Our laboratory focuses on developing electrochemical immunosensors and surface plasmon microarrays for minimally invasive insulin measurements in clinical sample matrices. By utilizing antibodies or aptamers as the insulin-selective biorecognition elements in combination with nanomaterials, we demonstrated a series of selective and clinically sensitive electrochemical and surface plasmon immunoassays. This review provides an overview of different electrochemical and surface plasmon immunoassays for insulin. Considering the paramount importance of diabetes diagnosis, treatment, and management and insulin pumps and monitoring devices with focus on both T1D (insulin-deficient condition) and type 2 diabetes (insulin-resistant condition), this review on insulin bioassays is timely and significant.

Graphical abstract

1. Diabetes

Diabetes is caused either by the impairment of insulin-producing β-cells leading to insulin deficiency (type 1 diabetes; T1D) or by the ineffective nature of available insulin due to cellular resistance to insulin’s action in metabolizing sugar (type 2 diabetes; T2D).1 Diabetes results in hyperglycemia that can eventually lead to dysfunction and failure of various organs. Long-term effects of diabetes can be severe and may cause retinopathy with potential blindness, renal failure, foot ulcers and amputations, and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. Although diabetes is broadly classified as T1D and T2D, there are other forms worth mentioning. A third type of diabetes called gestational diabetes occurs in pregnant women.2 Another form of diabetes, namely, latent autoimmune diabetes, in adults involves a slow destruction of β-cells leading to insufficient insulin production, but it does not require insulin treatment at the time of diagnosis.3

T1D and T2D have affected a large number of global populations. The latest reports by public health organizations have shown that diabetes is now becoming increasingly prevalent in children and young adults. Insulin being the primary hormone for maintaining glucose homeostasis serves as a valuable biomarker for diabetes management. While diabetes is a chronic disorder, adapting healthy lifestyle can slow its progression to clinical onset. The World Health Organization (WHO) has estimated that 422 million people are affected with diabetes worldwide. Additionally, WHO has predicted diabetes to be the seventh leading cause of death worldwide in 2030.4 Therefore, it is imperative to develop simple, sensitive, and selective diagnostic methods for measuring ultra-low levels of blood insulin for applications in insulin assays and monitoring systems.

A number of transduction methods have been employed for insulin measurements. Recently, the need for new bioanalytical tools for reliable measurements of picomolar concentrations of insulin in body fluids became significant for eventual biomedical applications in insulin pumps and artificial pancreas. Therefore, we focused on developing reliable and ultrasensitive bioanalytical methodologies to measure serum and whole blood insulin levels. In particular, our insulin assay methods were based on a multimodal approach to increase reliability and obtain complementing analytical and molecular binding insights based on electrochemical and surface plasmon assays. These two methodologies are reviewed in this articlefollowing notable contributions by otherresearchers in the field .

2. Insulin biosensors

Electrochemical glucose biosensors have been successful in personalized diabetes management by monitoring millimolar blood glucose concentrations. However, non-glucose biomarkers have gained significance in diabetes diagnosis and treatment prognosis. Insulin (molecular weight = 5808 Da) hormone consists of two polypeptide chains, an A-chain with 21 amino acids and a B-chain with 30 amino acids, linked by two disulfide bridges.5 It is a vital hormone secreted by pancreatic β-cells that regulates glucose metabolism. Any imbalance in glucose levels (low level: hypoglycemia and high level: hyperglycemia) can lead to severe health problems.6 Hence, it is important to maintain normal insulin levels to regulate glucose metabolism.

Normal insulin concentration in blood serum under a fasting condition is ~50 pM,7 and concentrations of <50 pM and >70 pM signify T1D and onset of T2D, respectively.8–10 The fasting concentration of blood glucose in healthy individuals is in the range of 2.5–7.3 mM11, and diabetes is diagnosed with a glucose level of >7.3 mM (130 mg/dL).12 Unlike the high glucose concentrations (millimolar), detecting the relatively lower insulin concentrations (picomolar; concentration with 9-orders of magnitude lower than glucose) in blood poses a considerable analytical challenge in attaining the required sensitivity with selectivity to overcome interferences from the presence of coexisting serum proteins and other biological components (calledthe sample matrix effect).

Insulin or insulin analogs are required to control the progression of T1D and T2D. Insulin pumps are computerized medical devices that are programmed to rapidly deliver insulin as a continuous (basal) or surge (bolus or additional) dose around mealtime to control the increase in blood glucose level and maintain homeostasis. A traditional insulin pump includes a pump (with controls and batteries), a reservoir for insulin, and a disposable infusion set with a plastic tube connection called the catheter. The pumps can be worn as a waistband or armband to deliver insulin through the catheter inserted with the aid of a needle in fatty tissues of the skin. The pumps are expensive but more accurate and offer better management than manual injections. However, these pumps are not affordable by a majority of patients due to high cost, and hence, self-monitoring remains inaccessible to a large population worldwide. This is a key impediment in diabetes management.

Diagnosing insulin in the clinically relevant picomolar concentrations has been a challenge; therefore, we explored the usefulness of nanomaterials in insulin biosensing by either modifying the transduction surfaces or conjugating the detection analyte with different nanomaterials to offer high sensitivity. Analytical methods such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), chemiluminescence, radioactive, and column immunoassays for detection of insulin have been reported.13,14 Radioactive labels are toxic and need special safety procedures and facility. Chromatographic methods involve optimization of separation conditions for each biomarker and require standards to identify the biomarker along with expensive mass spectrometry identification of compounds based on their m/z values. Often method optimization is a tedious task, and the mass spectrometry instrument needs systematic, full-time maintenance, and dedicated technicians. Hence, we identified the need for simple, less-expensive, and highly sensitive methods that can measure insulin in complex clinical matrices, such as serum and whole blood, thus facilitating the development of insulin assays and real-time monitoring devices.

3. Biosensord esignconsideration

The word “biosensor” has been defined in different ways in the literature depending on the field of application.15–17 Typically, a biosensor is an analytical device that integrates a biological recognition element specific to the target analyte and a physicochemical transducer. The transducer converts the biological recognition event into a measurable signal output with respect to the concentration (quantitative) or presence (qualitative) of the target analyte. The schematic representation of the components of a biosensor is illustrated in Fig. 1 with the listed transducers of relevance to our research.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of a typical insulin (PDB: 3V19) biosensor. In our work, we used different transduction methods, such as cyclic voltammetry (CV), square wave voltammetry (SWV), amperometry, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), quartz crystal microbalance (QCM), and surface plasmon resonance (SPR) microarray imager.

In biosensors, specific molecules from the sample bind to the bioreceptor. The interface gives a signal when such a biological interaction occurs, which is followed by the conversion of the biochemical signal into an electronic signal by the transducer. The signal processor then generates a physical parameter by converting the electronic signal into a numeric value. Finally, the results are displayed by the interface. Leyland C. Clark first elucidated the basic concept of biosensors in 1962 with the development of enzyme electrodes for glucose monitoring.18 Since then researchers from various fields gained interests in developing new sensing devices for the diagnosis and treatment of various diseases. The field of biosensors is, thus an excellent example of a multi and interdisciplinary research area. Different combinations of biomolecules and transducers can help in developing biosensors that can be used for a variety of applications including, medical diagnostics, drug delivery, environmental monitoring, food safety, and bioterrorism detection and prevention.

The analytical figures of merit, which define the performance characteristics of a biosensor, are selectivity to the target analyte, sensitivity, and dynamic range of detection. The combination of selectivity with low cost, portability, reusability, low sample volume requirement, and rapid analytical procedure has garnered immense commercial interest for biosensors. The “glucose pen” by Exatech launched in 1987 has been one of the successful commercial biosensors. Development of subcutaneously implantable needle-type electrodes for continuous glucose monitoring from Minimed. Inc.19 and a non-invasive GlucoWatch biographer from Cygnus Inc.20 are representative examples ofglucose biosensors.

4. Benchmarks for a successful biosensor development

A key factor involved in the construction of biosensor is the design of appropriate surface immobilization strategies for tethering biorecognition elements. To achieve practicability of abiosensor, it is important to fulfillthe following criteria:

the biorecognition element should retain its activity when attached to the sensor surface,

it should be tightly attached on to the sensor surface (should not desorb from the surface before measurements of target analytes) and should preferably be stable under a range of pH values, temperatures, ionic strengths, and chemical compositions,

the immobilized film should have long-term stability and durability,

the biorecognition element should be highly specific to the target biomolecule being detected, and

the binding sites of both the surface and target molecules should be accessible to each other to the maximum extent possible to yielda reasonably sensitive detection .

For a biosensor, the three required features are sensitivity, wide dynamic range, and selectivity. Sensitivity defines the extent of the sensor signal response with an increase in concentration of the analyte under measurement. Selectivity defines the ability of the sensor to distinguish between closely related molecules in the sample, and selectively detect the desired analyte in the presence of other related or unrelated molecules. While sensitivity of a sensor can increase with an increase in surface loading and accessibility of the analyte-capturing molecules, achieving a good dynamic range of detection is equally essential to facilitate measurements of a large number of real samples with varying range of concentrations. Although nanomaterial-based signal amplification strategies have improved the sensitivity of biosensors, the compromise on the dynamic range remains to be a bottleneckand has been only currently addressed by researchers.

Another common problem in the construction of biosensor is the interference from non-specific binding (NSB) of analytes and other molecules present in the sample upon binding on the free sensor surface, which affects the limit of detection (LOD) due to large background control signals. For example, if a specific analyte is to be detected in a complex matrix, such as serum or whole blood, there can be interferences from other non-specific biomolecules and biological components present in these sample matrices. Therefore, minimizing non-specific signals by using reagents such as detergent blockers (e.g., tween-20), protein blockers [e.g., bovine serum albumin (BSA) and casein], or polymer blockers (e.g., polyethylene glycol and ethanolamine) is important to increase the sensitivity and accuracy of biosensors. These agents should minimize NSB signals by saturating the free sensor surface without taking part in the assay. Thus, developing reliable and practically useful biosensors for detecting ultra-low concentrations of biomarkers in clinical samples with high selectivity and a wide range exhibits a considerable challenge.

5. Immobilization methods for designing biosensors

The common biomolecule immobilization chemistry used in designing biosensors include: (a) physical adsorption on a surface, (b) covalent binding to a surface, (c) entrapment within a polymer or a membrane, and (d) cross-linking between molecules.

Physical adsorption involves ionic bonding, van der Waals interactions, or hydrophobic forces. This is the simplest approach that can be performed under mild conditions; however, the stability of the immobilized molecules on surfaces is moderate. Biomolecules if physically adsorbed can display random orientations on the sensor surface, which can affect the extent of exposed fraction of binding sites available for target molecules to bind.21 For example, immunoglobulins can be adsorbed onto a sensor surface through various groups. This produces a random arrangement of protein molecules on the surface that can lead to a high degree of inaccessible binding sites for antigens, and thus, affects the sensitivity of the biosensor.

Chemisorption involves formation of a chemical bond between the surface and the molecule immobilized. Covalent attachment is the most preferred method for immobilizing biomolecules, which offers better surface stability than physisorption and a minimal loss of biological activity with time.22–25 These features enhance the reproducibility of the sensor. Functional groups of amino-acid side chains, such as amine (e.g., from lysine), carboxyl groups (from aspartic acid and glutamic acid), sulfhydryl groups (from free cysteine), and imidazole groups (from histidine) present in biomolecules can be exploited for covalent immobilization onto a biosensor surface. However, care should be taken to verify that the surface tethering groups are not a part of the analyte binding sites or enzyme active sites, which could hinder or disable the sensor function.

Transducer surfaces can also have end functional groups for effective covalent binding (e.g., hydroxyl groups on silica) or those modified to introduce specific reactive chemical groups to bind with the biomolecule. Metal surfaces such as gold (Au) and silver (Ag) can be treated with bifunctional alkanes to generate hydroxyl, carboxyl, or amino groups which can then be activated by carbodiimide chemistry or glutaraldehyde reagent to form linkage with biomolecules.26,27 Activated polysaccharides or polymer sensor chips have alsobeen used for coupling biomolecules. 28

Entrapping biological components in polymer gel, membrane, or surfactant matrices has been successfully implemented.29,30 Entrapment of proteins by photo- or irradiation-polymerization of a solution containing one (e.g., polyvinyl alcohol, polyvinyl chloride, polycarbonate, and polyacrylamide) or two (for preparing copolymers) monomers has been demonstrated.31 Semipermeable membrane NafionTM (a negatively charged perfluorinated sulfonate polymer) can entrap enzymes and reduce the contributions of interfering agents through charge repulsion. A drawback of entrapment method is the likelihood of the entrapped biological molecules leaching into the solution, which can affect the sensor performance during operation and the resultingreproducibility.

Cross-linking of biomolecules by a multifunctional reagent enhances the stability of covalently bound enzymes or proteins onto a surface. For example, glutaraldehyde links lysine amino groups of biomolecules onto a surface. This technique offers selective recognition and sensing of molecules and regulates signal transduction through surfaces.32 The cross-linking is stable under extreme pH values and temperatures. However, the concentration of glutaraldehyde should be optimal for the enzyme under use to prevent any structuraldistortion and biological activityof the enzyme .33

6. Transduction methods for measurements of insulin levels

The following transduction methods were employed by us: (a) electrochemical transducers such as cyclic voltammetry, square wave voltammetry (SWV), flow-injection microfluidics amperometric it curve, and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) (Fig. 2a, i to iv); (b) a mass-sensitive transducer such as quartz crystal microbalance (QCM) (Fig. 2b), and (c) an optical transducer such as surface plasmon resonance imaging (SPRi) (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2.

(a) Electrochemical methods showing (i) a representative cyclic voltammogram, (ii) a square wave voltammogram, (iii) an amperometric i-t curve at an applied constant potential, and (iv) the Nyquist plot representation of a faradaic impedance spectrum for a diffusion controlled interfacial charge-transfer process between an electrode and electrolyte interface containing a dissolved redox probe. (b) Schematic of oscillation frequency decrease monitored in real-time upon addition of a mass onto a gold disk infused quartz crystal measured by QCM. (c) Surface plasmon resonance monitoring of an antigen-antibody interaction with binding kinetics in a microarray format.

6.1 Electrochemical transducers

Electrochemistry is one of the oldest branches of chemistry used for studying heterogeneous electron transfer kinetics at a metal/solution interface.34 Applications in metallurgy,35 corrosion science,36 fuel cells,37 catalysis, and sensors have been recognized.38 The advantages of using electrochemistry are its inexpensive potentiostat, simple-to-design electrochemical cells, and features for miniature geometry, automation, sensitivity, and simplicity of detection and analysis procedures. Electrochemical cells consist of a working electrode (WE), where the redox process of interest occurs, a reference electrode (RE) that provides the reference potential readout of the redox processes occurring at the WE, and a counter electrode that balances the current flow on the WE and minimizes the effect of current from altering the standard reference potential scale at the RE. After the WE is placed in an electrolyte solution, a range of potentials is applied to determine the potential at which interfacial electron transport between the electrode and electrolyte interface occurs, and this event is measured as a faradaic current (i.e., current from an oxidation/reduction process).

Electrochemical insulin biosensors

The pioneering work in insulin sensing started with the development of electrochemical insulin biosensors. Electrochemical detection of insulin has been one of the most attractive ways of measuring insulin because of its unique methodological advantages, such as simplicity in electrode fabrication, portable instrumentation, sensitivity, low cost, automation features, and fast detection and analysis. Despite these advantages, the slow kinetics of insulin oxidation required various chemically modified electrodes to mediate the electron transfer between the electrode and insulin and facilitate a kinetically faster insulin oxidation for detection as oxidation currents. Early reports on electrochemical insulin biosensors were based on mediated oxidation of purified insulin by redox mediators that followed an EC′ mechanism as shown below.39–42

Where E is the electrochemical step, and C′ is the catalytic regeneration of the reduced form of the mediator in proportion to the insulin concentration and the associated increase in oxidation currents.

Electrochemical detection of insulin was first started by Cox and Gray using ruthenium (Ru)-modified films in acidic conditions (pH 2).43 These modified films were later tested for insulin detection in physiological buffer (pH 7.4) by a flow-injection analysis (FIA).44 This was the first study initiated to mimic the human physiological pH conditions. Thus, the stable electrode developed was further modified using iridium (Ir)45 and Ru-metallodendrimer multilayers46 to yield a linear dynamic range from micromolar to nanomolar concentrations of insulin in buffer (pH 7.4) and set a pathway for in vitro measurements of insulin. Although these modified electrodes facilitated insulin detection, they had practical limitations from the need for electron transfer mediators, which are not stable under physiological conditions along with the problem of fouling the electrode surface. Moreover, measurements of picomolar insulin levels in blood by selective oxidation are not possible due to the parallel oxidation of several other coexisting proteins and biological components.

Taking advantage of the catalytic activity of Ru-modified electrodes developed by Gorski and Cox for insulin oxidation39,40, Wang et al. designed a needle-type dual microsensor that integrated a ruthenium oxide (RuOx)-modified carbon paste microelectrode with a metalized(rhodinized) carbon paste glucose oxidase electrode to simultaneously detect nanomolar concentrations of insulin and millimolar concentrations of glucose in buffer by amperometry.47 Later, Wang et al. utilized carbon nanotubes (CNTs) for effective catalytic oxidation of insulin in buffer.48 CNTs possess unique mechanical, electronic, optical, and chemical properties that make them suitable for electrochemical sensing. The CNT-modified electrodes were better than the prior redox mediator-modified electrodes in terms of electrode fabrication and robustness, overpotential reduction, and minimizing surface fouling. These features enabled sensitive and stable amperometric signals of insulin inpH 7.4 buffer.

Bulk electrolysis and direct insulin oxidation on a chitosan (CHIT)-CNT-modified electrode confirmed the oxidation of tyrosine residues of insulin at 0.7 V vs Ag/AgCl.49 Direct electrochemical detection is very promising for the development of in vitro diagnostic sensors that can diagnose the desired biomarker levels in a rapid fashion. Synergistic effects from a RuOx/CNT-modified electrode led to an enhanced electrochemical activity toward insulin oxidation, but the exact mechanism was not fully understood with this modified electrode.50

A CNT/Nafion-modified surface coated with a film of mixed nickel (Ni) and cobalt oxides detected insulin in the nanomolar range in buffers (pH 7.4) but with a large background current in the absence of insulin (i.e., a high non-specific voltammetric signal from the CNT-NiCoO2/Nafion electrode in the absence of insulin).44 In addition, nickel oxide nanoparticles-modified Nafion-multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWNTs) coating on screen-printed electrodes (NiONPs/Nafion-MWNTs/SPE) were unable to provide a high sensitivity (1.8 μA/μM) in 0.1 M NaOH solution.46 Cliffel et al. designed a MWNT-dihydropyran (MWNT/DHP) composite electrode for electrochemical detection of insulin secreted by pancreatic islets using a microfluidicsset -up.51

An electrochemical sensor made from MWNT with molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) could detect insulin in blood serum as well as in pharmaceutical samples by differential pulse anodic stripping voltammetry (DPASV) with no false positive signals.52 However, the major drawback of this sensor was the time-consuming, tedious synthesis of monomer, which required 16 h, and subsequentsynthesis of the MWNT-MIP adductfrom the monomer that needed another 10 h.

Ni powder-doped-modified renewable carbon composite electrodes prepared by a sol-gel technique,40 guanine and electrodeposited nickel oxide (NiOx),53 and silicon carbide (SiC) nanoparticles-modified glassy carbon electrodes54 offered improvements over the unstable redox mediator-modified electrodes in terms of shorter response time, longer electroactive stability, decrease in overpotential for insulin oxidation, and higher sensitivity under alkaline and physiological pH solutions. Similarly, a silica gel-modified carbon paste electrode detected insulin at picomolar levels; nevertheless, the detection in a simple buffer medium( pH 2)does not represent the complexity ofclinical sample matrices.39

Despite notable contributions from prior studies, lack of biological selectivity and use of non-clinical sample matrix for insulin detection did not prove useful for clinical application. To address this bottleneck issue and mitigate assay limitations, our laboratory focused on developing electrochemical bioassays for measuring insulin in human serum. Our electrochemical approach was later translated to surface plasmon assays to obtain an image-based output and measurements in whole blood with insights into binding kinetics of insulin immunoassay platformsdesigned by us .

We explored the use of specific insulin biorecognition elements, such as monoclonal insulin antibodies (Ab) or aptamers, in our assays. Using a simple approach of insulin-antibody immobilization on carboxylate thiol modified gold (Au) coated quartz crystals, we achieved selective detection of serum insulin (2-fold diluted in phosphate buffer). In this assay, to minimize non-specific background signals from the serummatrix, we isolated serum insulin by capturing onto magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs), and then detected the binding of this MNP-insulin material onto the surface immobilized insulin antibody. We obtained LOD of 5 pM by using electrochemical QCM technique that combined the measurements of oscillation frequency changeby QCM and charge -transfer resistance by EIS (Fig. 3a,3b).55

Fig. 3.

(a) Representative electrochemical mass sensor designed for insulin detection based on quartz crystal microbalance followed by faradaic impedance signals. (b) A: oscillation frequency change, and B: increase in charge-transfer resistance for a 2-fold diluted serum insulin captured onto polyacrylic acid functionalized MNPs (100 nm hydrodynamic diameter) and bound onto the surface immobilized insulin antibody. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 55, The Royal Society of Chemistry.

We then designed a voltammetric immunosensor using 1-pyrenebutyric acid (Py) molecules that were pi-pi stacked with MWNTs to immobilize monoclonal insulin antibody (Abinsulin) and detection of serum insulin captured onto the MNPs (Fig. 4a, 4b).56 In these bioelectrodes, direct oxidation of tyrosine residues of insulin was difficult to observe because of the presence of amino acids from other interfering serum proteins and the surface immobilized insulin antibody. Hence, we adopted an indirect detection approach in which a decrease in current signal of a cost-effective redox probe, [Fe(CN)6]3−/4−, was achieved for an increase in serum insulin concentration binding to surface insulin antibody.

Fig. 4.

(a) Representative voltammetric MWNT/Py/Abinsulin immunosensor designed to monitor current signals, and (b) A: square wave voltammograms for measuring 2-fold diluted serum insulin concentration captured onto MNPs (increasing concentration from a to f), and B: the calibration plot of sensor response. T1D and T2D denote type 1 and type 2 diabetes patient serum samples and the designed voltammetric sensor correlated with the standard ELISA method. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 56. Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society.

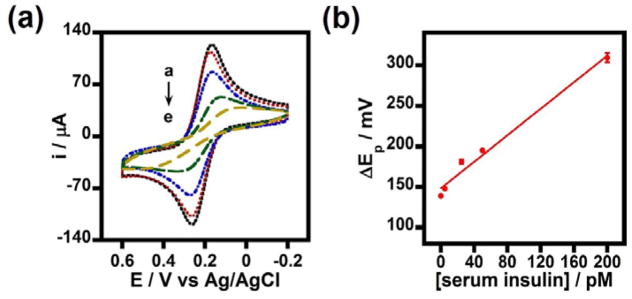

Application of MNPs allowed efficient isolation of insulin from the bulk serum solution and decreased the non-specific signals upon binding to the surface insulin antibody.55,56 This together resulted in the clinically required picomolar sensitivity of insulin detection. We observed a quasi-reversible electron transfer process for the designed voltammetric immunosensor upon the binding of serum insulin with the insulin antibody-immobilized, MWNT/Py-modified, pyrolytic graphite edge (PGE) electrodes (PGE/MWNT/Py/Abinsulin) (Fig. 5).56

Fig. 5.

(a) Cyclic voltammograms in Fe(CN)63−/4− mixture for PGE/MWNT/Py/Abinsulin/BSA electrodes treated with 0 (insulin unspiked 50% serum), 5, 25, 50, and 200 pM insulin spiked serum samples (a-e) captured onto MNPs; and (b) the corresponding increase in peak separation (ΔEp) values for the insulin concentration dependent binding of serum insulin-MNPs onto the surface insulin antibody on PGE/MWNT/Py/Abinsulin/BSA electrodes. Scan rate 0.1 Vs−1. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 56. Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society.

Following the demonstration of our electrochemical mass sensing and voltammetric immunosensing platforms for serum insulin, we advanced further by developing a flow-injection amperometric insulin immunosensor. Although, the flow-injection amperometry is an established methodology, application of this method for pyrenyl-carbon nanostructure-modified electrodes for serum insulin immunosensing is novel. In the flow-injection assay, we additionally discovered the favorable effect of combining chemically carboxylated MWNTs with non-covalent pi-pi stacked pyrene butyric acid units to enrich surface -COOH groups. This enrichment procedure allowed greater immobilization of insulin-antibody molecules on the surface and increased serum insulin detection sensitivity (by ~3-fold) than the immunosensorbased on only the chemically carboxylated MWNTs.

In our flow-injection assay, we monitored current signals with increase in serum insulin concentration by a sandwich immunoassay format (Fig. 6a, 6b).57 Insulin from serum was selectively captured by horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled insulin antibody covalently attached to MNPs, and detected upon binding to the surface immobilized second insulin antibody. The designed flow-injection immunosensor offered a linear detection range of 2–125 pM insulin prepared in a 20-fold diluted human serum. The LOD was1.35 pM.

Fig. 6.

(a) Amperometric flow-injection immunosensor designed for insulin detection in 20-fold diluted human serum, and (b) current signals with insulin concentration presented with a patient sample data validating the applicability of such sensors for patient serum samples. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 57, The Royal Society of Chemistry.

An electrochemical aptamer-based insulin sensor with insulin-linked polymorphic region forming a G-quadruplex upon insulin binding from a buffer solution has been reported.58 Although this study demonstrated the feasibility of using aptamers in the fabrication of folding-based electrochemical sensor development, the LOD of this sensor in buffer was in the nanomolar range making it clinically less relevant. An electrochemical aptasensor modified by Au nanoparticles/Orange II functionalized graphene (AuNPs/O-GNs) with anchored insulin binding aptamer (IBA) has recently been demonstrated for insulin detection in buffer by DPV.59 Although the integration of Au nanoparticles with graphene led to the construction of a highly conductive and sensitive electrochemical insulin sensor with a LOD of 6 fM, the major limitation was the requirement for 100-times dilution of serum samples.

Davis et al.developed a sensitive label -free electrochemical immunosensor for insulin present in 50% serum with a LOD of 1.2 pM by EIS using a polyethylene glycol monolayer-modified Au surface.60 Their subsequent work derived even a lower concentration detection of insulin at subpicomolar levels in serum and in patient samples based on a chemisorbed poly(carboxybetaine methacrylate) (PCBMA) surface with non-faradaic impedance detection.61 Interestingly, their findings on phase angle change in the low frequency (0.1–10 Hz) regime for picomolar neat serum insulin concentrations were notable. However, their sensor surface construction involved a relatively longer time-consuming surface designs before the sample could be detected. On a technical note, for a non-faradaic impedimetric sensor with a calibration plot lying within a small overall phase angle change, the probability for sources of false positive signals is a potential concern when dealing with complex clinical samples. Overall, the electrochemical detection remains to be attractive due to its simplicity and cost-effectiveness. Table 1 provides an overview of various reported modified electrodes and electrochemical approaches for detection of insulin in a simple buffer solution or serum medium.

Table 1.

Different modified electrodes for electrochemical insulin detection.

| Electrode surface | Method | Limit of detection (LOD) | Sensitivity | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ru-modified glassy carbon electrode | FIA | 5 ng in 7.5 μL (pH 2) | 0.42 nA/ng | [39] |

| RuOx-modified carbon fiber microelectrode | FIA | 23 nM (pH 7.4) | 0.072 nA/μM | [40] |

| IrOx-modified glassy carbon electrode | Amperometry | 20 nM (pH 7.4) | 35.2 nA/μM | [41] |

| Ru-metallodendrimer multi-Layer modified carbon electrode | FIA | 2 nM (pH 7.0) | 225 nA/μM | [42] |

| RuOx-modified carbon paste rhodenized carbon paste glucose oxidase microsensor | Amperometry | 50 nM (pH 7.4) for insulin 0.4 mM (pH 7.4) for glucose |

875 pA/μM 245 pA/mM |

[47] |

| CNT-modified glassy carbon electrode | FIA | 14 nM (pH 7.4) | 48 nA/μM | [48] |

| CHIT-CNT-modified glassy carbon electrode | Amperometry | ~30 nM (pH 7.4) | 135 nA/μM | [49] |

| RuOx/CNT-modified carbon electrode | FIA | 1 nM (pH 7.4) | 541 nA/μM | [50] |

| Ni doped carbon composite electrode | Amperometry FIA |

40 pM (pH 13) 2pM |

29.8 pA/pM 271.9 pA/pM |

[45] |

| MWNT/DHP-modified glassy carbon electrode | Amperometry | 1 μM (pH 7.4) | - | [51] |

| MIP-MWCNT-modified pencil graphite electrode | DPASV | 0.0186 nM (pH 7.4) | - | [52] |

| Guanine/NiOx-modified glassy carbon electrode | Amperometry | 22 pM (pH 7.4) | 100.9 pA/pM | [53] |

| SiC nanoparticles-modified glassy carbon electrode | DPV FIA |

20 nM (pH 7.4) 3.3 pM |

954.3 nA/μM 710 pA/pM |

[54] |

| CNT-Ni-CoO/Nafion-modified screen-printed electrode | Amperometry | 38 nM (pH 7.4) | 3.9 nA/μM | [44] |

| NiONPs/Nafion-MWCNTs/SPE | Amperometry | 6.1 nM (0.1M NaOH) | 1.83 μA/μM | [46] |

| Silica gel-modified carbon paste electrode | Amperometry | 36 pM (pH 2) | 107.3 pA/pM | [43] |

| Au-insulin Ab-BSA-modified electrode (immunosensor) | QCM EIS |

5 pM (50% blood serum) | 3.3 Hz/pM 16 Ohm/pM |

[55] |

| PGE/MWNT-Py/insulin Ab-BSA-modified electrode (immunosensor) | SWV | 5 pM (50% blood serum) | - | [56] |

| MWNT-COOH/Py-COOH/Absurface/BSA/MNP-AbHRP-insulin-modified Au SPE(immunosensor) | Amperometry (flow-injection) | 1.35 pM (5% serum) | 11.79 nA/pM | [57] |

| Au-insulin aptamer methylene blue-modified electrode | ACV [phosphate buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4] | 10 nM | - | [58] |

| AuNPs/O-GNs/SH-IBA-modified GCE (aptasensor) | DPV | 6 fM (PBS, pH 7.4) | - | [59] |

| Au-insulin Ab-BSA-modified electrode (immunosensor) | EIS | 1.2 pM (pH 7.4) 4.77 pM (50% blood serum) |

- | [60] |

| Au-PCBMA-insulin Ab-BSA modified electrode (immunosensor) | EIS | 42.6 fM (neat serum) | - | [61] |

6.2 SPRtransducers

Combining new electrochemical bioassays with other complementing methods can offer assay validation and additional insights. In this regard, combination of electrochemical assays with SPRi offers the unique advantages of binding strength assessment of biomolecular interactions. Optimization of assays by the surface plasmon method for the best performance conditions and transfer to a low-cost throughput electrochemical platform is possible, provided the surface chemistry designs are compatible in both methods.

In SPRi and electrochemical assays, the application of nanoparticles for signal amplification to achieve ultra-low detection limits and high sensitivity has been one of the attractive strategies. It is worth noting that the nanoparticle-based amplification labels are generally more robust than chemical or enzymatic labels in view of exposure to light, air, and solvent, and storage stability. Our laboratory has developed SPRi based sensitive serum/whole blood insulin and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) microarrays.

SPRi is an optical technique which utilizes visible to near infrared (NIR) light-excited surface plasmon polaritons (SPPs) to detect and measure molecular binding interactions on a metal surface (usually Au or Ag) from refractive index changes at the metal-dielectric interface.62,63 SPP is an evanescent electromagnetic wave generated when light excites the free electrons on the metal surface.64,65 Its propagation along the metal/dielectric interface creates an electromagnetic field that decays exponentially. SPRi can probe refractive index changes up to a distance of 200 nm above the metal surface, and hence is considered to be a highly sensitive surface analytical technique.66 Signal enhancements by use of plasmon enhancing metallic nanoparticles has been an established approach in the SPR field.

Conventionally, the incident angle or wavelength of SPR source is fixed and a single element detector detects the reflected light. In SPRi, the incident wavelength is constant, and the angle required for maximum change in binding interaction of biomolecules can also be fixed. This procedure allows direct monitoring of the reflectivity changes in real-time, which can be followed with the imaging of pixel intensity changes across the Au array chip by a charge-coupled-device.67 The capturing of images before and after specific binding events (e.g., antigen-antibody, aptamer-antigen, DNA-DNA hybridization, receptor-protein, receptor-ligand, and protein-ligand interactions) on the surface provides the net difference in pixel intensities.

SPRinsulin assays

SPRibein g a versatile technique has opened opportunities for analysis of a wide range of analytes relevant to food, environment, and health.68–70 With regard to SPR insulin assays, Bae et al. demonstrated the detection of insulin in a simple buffer solution using an imaging ellipsometry.71 The ellipsometric images of insulin binding to its antibody were acquired, and the mean optical intensities of this binding gave a detection range from 10 ng/mL (2 pM) to 100 μg/mL (20 nM) in buffer. Later Gobi et al. demonstrated insulin detection in buffer (pH 7.2) using a heterobifunctional oligo(ethyleneglycol)-dithiocarboxylic acid derivatized Au film.72 With a 1:1 antigen-antibody binding ratio, an indirect approach for detection of immobilized insulin on the derivatized surface was accomplished by binding an insulin antibody prepared in solution, which allowed measurable SPR signals as the insulin antibody is much larger in size than insulin and hence, produces a greater signal change. This approach yielded LOD of 1 ng/mL (0.2 pM).

Using a similar indirect competitive immunoassay, a multifunctional Au nanoparticle-based SPR sensor detected insulin in a 10-times diluted serum with a LOD of 0.5 pM.73 In this report, Au nanoparticles encapsulated bifunctional hydroxyl/thiol-functionalized fourth-generation polyamidoamide dendrimer was immobilized onto a self-assembled monolayer of Au surface. This approach allowed for the assay to be highly stable and sensitive with good binding affinities toward antibodies, and with minimized non-specific adsorptions. This SPR immunosensor was the first of its kind, which paved a way for label-free insulin detection in a clinical matrix with reduced non-specific protein adsorption but on a conventional SPR setup. Not an optical device, but a field effect transistor with multiple silicon nanochannels detected insulin down to 10 fM in a diluted human serum.74 However, the serum was diluted 10,000-fold in order to probably reduce the salt concentration suitable for the functioning of the detector.

With the prior aforementioned knowledge from contributions by researchers in the field, our laboratory examined the influence of serum matrix in affecting the detection sensitivity of insulin by SPRi. For this, we prepared spiked insulin standards in serum diluted for 2, 4, and 8-fold in PBS. As control, we used insulin dissolved in phosphate buffer (0% serum). We captured the spiked insulin standards prepared in these solutions by MNPs (100 nm hydrodynamic diameter, polyacrylic acid functionalized, and COOH groups activated by a carbodiimide). MNPs can covalently attach insulin via its two-surface lysine residues. Nonetheless, any strong non-covalent interactions cannot be ruled out. Moreover, other serum proteins along with insulin can also get attached to MNPs. However, the co-immobilization of non-insulin serum proteins did not affect the picomolar insulin detection. This is probably due to the large number of particles present in a milligram of MNPs (~1.8 × 1012 particles/mg) to capture serum proteins and insulin and still allow sensitive detection.

Based on the ELISA estimation of free serum insulin present in solution before and after binding onto the MNPs, successful capturing of the insulin onto MNPs was confirmed and quantitated.56,75 The insulin-captured MNPs were allowed to bind insulin antibody immobilized on Au microarray for measurement by the SPR imager (Fig. 7a, 7b). We additionally determined the SPRi responses for direct (serum insulin directly captured by COOH-activated MNPs) and sandwich insulin assay formats (serum insulin captured by insulin antibodythat was already covalently attached toMNPs ).

Fig. 7.

(a) SPRi microarray immunosensor developed for insulin detection in human serum, and (b) SPRi responses inferring the serum matrix effect and the performance of direct vs. sandwiched 50% serum insulin immunoassay. Reprinted with permission from Ref. Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society.

Our results suggested that 2-fold diluted serum insulin-MNP conjugates exhibited higher SPRi responses because of the larger hydrodynamic particle size than the more diluted serum solutions. As expected, the SPRi response was the highest for serum-free buffer insulin samples because of the absence of non-specific signals from the serum proteins. Moreover, the sandwich format involving the binding of second antibody-mediated capturing of serum insulin onto MNPs (selective insulin isolation) for binding onto the surface immobilized insulin antibody showed greater signals than the direct MNP-captured serum insulin (not a selective isolation). Nonetheless, both the direct and sandwich immunoassay formats offered picomolar level serum insulin detectionin the designed SPR microarrayplatform (Fig. 7b).

Our subsequent study focused on a much more complex matrix such as whole blood to detect two biomarkers, insulin and HbA1c, in one assay by an aptamer-surface antibody sandwich array format.76 Sensitive detection was achieved by decorating magnetic NPs with dual quantum dots (QDs; one for insulin and the second for HbA1c) to simultaneously accomplish both the surface plasmon and fluorescence imaging of the two biomarkers with binding kinetics analysis (Fig. 8a, 8b). In this study, amine-functionalized MNPs were electrostatically adsorbed with two types of carboxylated QDs of emission wavelengths 565 and 800 nm. Then, aptamers specific for insulin or HbA1c were covalently attached to the carbodiimide-activated COOH groups of QDs; these conjugates were used for capturing insulin and HbA1c present in whole blood diluted 20-times in buffer. These conjugates were magnetically separated and washed in PBS and were mixed in 1:1 v/v ratio for detection using SPR microarray spots immobilized with insulin antibody or HbA1c-antibody. Detection limits of 4 pM insulin and 1% HbA1c were achieved by this novel dual biomarker immunoarray format. In addition to the image output of insulin and HbA1c levels, we obtained binding constants for the MNP-QDot-aptamer-insulin or MNP-QDot-aptamer-HbA1c binding to their respective surface antibodies from the SPR signals monitored with the time of binding.

Fig. 8.

(a) Dual SPRi microarray imager developed for insulin and HbA1c detection in an unprocessed whole blood diluted 20-times in buffer, and (b) the respective difference images, line profiles, and real-time SPRi responses (from left to right) for various concentrations of insulin and HbA1c. Reproduced with permission from Ref. Copyright 2017 American Chemical Society.

In an earlier report, a NIR fluorescence resonance energy transfer study using NIR QD and oxidized carbon nanoparticles with aptamers as the biorecognition element to insulin obtained a linear range of detection from 1 pM to 2 nM in human plasma with a LOD of 0.6 pM.77 Our SPRi with fluorescence imaging assay is advantageous over prior methods to accomplish dual biomarker detection within the clinically relevant range in a complex whole blood sample along with binding kinetics analysis. Additionally, our methodology can be easily scaled-up to a throughput microarray format with low sample volume requirements making it applicable for analyzing a largenumber of patient samples.

7. Summary and future outlook

Establishing reliable diagnostic methods with non-invasive and minimally invasive features for sensitive and selective measurements of ultra-low levels of predictive biomarkers in clinical matrices will strengthen the diagnosis, treatment, and management of diabetes. The current trend of integrating nanotechnology with electrochemical and SPRi as detection tools with molecular binding insights holds great promise in the development of ultrasensitive, reliable, and useful diabetes biomarker devices. Current state-of-the-art multiplexed detection, microfluidics with automation, and throughput sensing are promising for developing diagnostic assays for health applications. While one area of research is device fabrication (e.g., micro and nano fluidics, bioengineering, and automation), fundamental quantitative understanding of the intricacies of nano surface chemistry designs still remains largely unexplored. New surface chemistry approaches can be constantly updated into sensor devices for improvements in performance. Combating the limitations of high-throughput microarray detection for a panel of biomarkers with minimal NSB by electrochemical and optical means can further push the development of clinical diabetes biosensors.

Another area of significance is the development of implantable glucose and insulin biosensors in which a biocompatible micro or nano sensor is surgically inserted under the subcutaneous tissue that is able to continuously monitor glucose or insulin levels and provide digital readouts into a device (preferably cellphones) by a wireless technology. While, there has been a remarkable progress in designing such biosensors, they do lack continuous performance over a long period of time due to “foreign body reactions” with implanted biomaterials. Senseonics EversenseTM 90-day implantable continuous glucose monitoring sensor was recently approved in Europe. Glysens IGGM® has developed an implantable sensor that can function for over a year in preclinical studies, which is an impressive success for any implantable biosensor, and further research and development is required to make notable improvements.78 Another specific area that has been explored is the non-invasive measurement of glucose and insulin level. There are abundant research opportunities and challenges that are to be overcome for researchers and biomedical laboratories to devise methods for early prediction, prevention, and user-friendly monitoring and successful management of growing diabetic disorders.

Acknowledgments

Research findings of the authors, including contributions from collaborators, presented in this review article were supported partly by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health, MD, USA (Award Number R15DK103386), and partly by the Oklahoma State University. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors, and it does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We thank Jinesh Niroula for the insightful discussions.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest.

There are no conflicts to declare.

References

- 1.Alberti KGMM, Zimmet PZ. Diabetic Med. 1998;15:539–553. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199807)15:7<539::AID-DIA668>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reece EA, Moore T. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;208:255–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.10.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stenström G, Gottsäter A, Bakhtadze E, Berger B, Sundkvist G. Diabetes. 2005;54:S68–S72. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.suppl_2.s68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mathers CD, Loncar D. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowsher RR, Nowatzke WL. Bioanalysis. 2011;3:883–898. doi: 10.4155/bio.11.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fukumori Y, Takeda H, Fujisawa T, Ushijima K, Onodera S, Shiomi N. The Journal of Nutrition. 2000;130:1946–1949. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.8.1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freckmann G, Hagenlocher S, Baumstark A, Jendrike N, Gillen RC, Rössner K, Haug C. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2007;1:695–703. doi: 10.1177/193229680700100513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muoio DM, Newgard CB. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:193–205. doi: 10.1038/nrm2327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weyer C, Hanson RL, Tataranni PA, Bogardus C, Pratley RE. Diabetes. 2000;49:2094–2101. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.12.2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goetz FC, French LR, Thomas W, Gingerich RL, Clements JP. Metabolism. 1995;44:1371–1376. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(95)90045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alberti KM, Dornhorst A, Rowe AS. Isr J Med Sci. 1975;11:571–580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:51–580. doi: 10.2337/diacare.2951150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manley SE, Stratton IM, Clark PM, Luzio SD. Clin Chem. 2007;53:922–932. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.077784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shen H, Aspinwall CA, Kennedy RT. J Chromatogr, Biomed Appl. 1997;689:295–303. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(96)00336-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buerk DG. Biosensors Theory and Applications. Technomic Publishers; Lancaster: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perumal V, Hashim U. J Appl Biomed. 2014;12:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirsch J, Siltanen C, Zhou Q, Revzin A, Simonian A. Chem Soc Rev. 2013;42:413–440. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60141b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clark L, Jr, Lyons C. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1962;102:29–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1962.tb13623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bindra D, Zhang Y, Wilson G, Sternberg R, Trevenot D, Reach G, Moatti D. Anal Chem. 1991;63:1692–1696. doi: 10.1021/ac00017a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tierney M, Kim H, Tamada J, Potts R. Electroanalysis. 2000;12:666–671. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zull JE, Reed-Mundell J, Lee YW, Vezenov D, Ziats NP, Anderson JM, Sukenik CN. J Ind Microbiol. 1994;13:137–143. doi: 10.1007/BF01583997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muramatsu H, Kajiwara K, Tamiya E, Karube I. Anal Chem. 1986;188:257–261. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson M, Arthur CL, Dhaliwal GK. Anal Chem. 1986;58:1206–1209. doi: 10.1021/ac00297a051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prusak-Sochaczewski E, Loung JHT. Anal Lett. 1990;23:401–409. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leggett GJ, Roberts CJ, Williams PM, Davies MC, Jackson DE, Tendler SJB. Langmuir. 1993;9:2356–2362. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caruso F, Rodda E, Furlong DN. J Colloid Interface Sci. 1995;178:104–115. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geddes NJ, Paschinger EM, Furlong DN, Caruso F, Hoffman CL, Rabolt JF. Thin Solid Films. 1995;260:192–199. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Löfås S, Johnsson B, Tegendal K, Rönnberg I. Colloid Surf B. 1993;1:83–89. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Updike SJ, Hicks GP. Nature. 1967;214:986–988. doi: 10.1038/214986a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang J, Hooijmans CM, Briasco CA, Geraats SGM, Luyben KCAM, Thomas D, Barbotin JN. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1990;33:619–623. doi: 10.1007/BF00604925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hall EAH, Hall CE, Marttens N, Mustan MN, Datta D. In: Uses of immolibizedBiological Compounds. Guilbault CG, editor. Dordrecht: Kluwer; 1993. pp. 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ojida A, Inoue M–A, Mito-oka Y, Hamachi I. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:10184–10185. doi: 10.1021/ja036317r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chui WK, Wan LS. J Microencapsulation. 1997;14:51–61. doi: 10.3109/02652049709056467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andrieux CP, Hapiot P, Saveant JM. Chem Rev. 1990;90:723–738. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xiao W, Wang D. Chem Soc Rev. 2014;43:3215–3228. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60327j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adriaens A, Dowsett M. Acc Chem Res. 2010;43:927–935. doi: 10.1021/ar900269f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xiang Y, Lu S, Jiang SP. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:7291–7321. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35048c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Choi K, Ng AHC, Fobel R, Wheeler AR. Annu Rev Anal Chem. 2012;5:413–440. doi: 10.1146/annurev-anchem-062011-143028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jaafariasl M, Shams E, Amini MK. Electrochim Acta. 2011;56:4390–4395. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salimi A, Roushani M, Soltanian S, Hallaj R. Anal Chem. 2007;79:7431–7438. doi: 10.1021/ac0702948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arvinte, Westermann AC, Sesay AM, Virtanen V. Sens Actuators B. 2010;150:756–763. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rafiee, Fakhari AR. Biosens Bioelectron. 2013;46:130–135. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2013.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cox JA, Gray T. Anal Chem. 1989;61:2462–2464. doi: 10.1021/ac00196a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gorski W, Aspinwall CA, Lakey T, JR, Kennedy RT. J Electroanal Chem. 1997;425:191–199. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pikulski M, Gorski W. Anal Chem. 2000;72:2696–2702. doi: 10.1021/ac000343f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cheng L, Pacey GE, Cox JA. Anal Chem. 2001;73:5607–5610. doi: 10.1021/ac0105585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang J, Zhang X. Anal Chem. 2001;73:844–847. doi: 10.1021/ac0009393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang J, Musameh M. Anal Chim Acta. 2004;511:33–36. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang M, Mullens C, Gorski W. Anal Chem. 2005;77:6396–6401. doi: 10.1021/ac0508752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang J, Tangkuaram T, Loyprasert S, Vazquez-Alvarez T, Veerasai W, Kanatharana P, Thavarungkul P. Anal Chim Acta. 2007;581:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2006.07.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Snider RM, Ciobanu M, Rue AE, Cliffel DE. Anal Chim Acta. 2008;609:44–52. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2007.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Prasad B, Madhuri R, Tiwari MP, Sharma PS. Electrochim Acta. 2010;55:9146–9156. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Salimi A, Noorbakhash A, Sharifi E, Semnani A. Biosens Bioelectron. 2008;24:792–798. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2008.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Salimi, Mohamadi L, Hallaj R, Soltanian S. Electrochem Commun. 2009;13:1116–1119. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Singh V, Krishnan S. Analyst. 2014;139:724–728. doi: 10.1039/c3an01542d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Singh V, Krishnan S. Anal Chem. 2015;87:2648–2654. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Niroula J, Premaratne G, Ali Shojaee S, Lucca DA, Krishnan S. Chem Commun. 2016;52:13039–13042. doi: 10.1039/c6cc07022a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gerasimov JY, Schaefer CS, Yang W, Grout RL, Lai RY. Biosens Bioelectron. 2013;42:62–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2012.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li T, Liu Z, Wang L, Guo Y. RSC Adv. 2016;6:30732–30738. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xu M, Luo X, Davis JJ. Biosens Bioelectron. 2013;39:21–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Luo X, Xu M, Freeman C, James T, Davis JJ. Anal Chem. 2013;85:4129–4134. doi: 10.1021/ac4002657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liedberg, Nylander C, Lundstrom I. Biosens Bioelectron. 1995;10:1–9. doi: 10.1016/0956-5663(95)96965-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Markey F. Bia J. 1999;6:14–17. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ritchie RH. Phys Rev. 1957;106:874–881. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Otto A. Zeitschrift fur Physik A Hadrons and Nuclei. 1968;216:398–410. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Homola J, Yee SS, Gauglitz G. Sens Actuators, B. 1999;54:3–15. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Steiner G. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2008;391:1509–1519. doi: 10.1007/s00216-008-1911-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sciacca, Francois A, Hoffmann P, Monro TM. Sens Actuators, B. 2013;183:454–458. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shabani A, Tabrizian M. Analyst. 2013;138:6052–6062. doi: 10.1039/c3an01374j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zeidan E, Li S, Zhou Z, Miller J, Sandros MG. Scientific Reports. 2016;6:36348. doi: 10.1038/srep36348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bae YM, Oh B–K, Lee W, Lee WH, Choi J–W. Biosens Bioelectron. 2004;20:895–902. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2004.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gobi KV, Iwasaka H, Miura N. Biosens Bioelectron. 2007;22:1382–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fransconi M, Tortolini C, Botrè F, Mazzei F. Anal Chem. 2010;82:7335–7342. doi: 10.1021/ac101319k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Regonda S, Tian R, Gao J, Greene S, Ding J, Hu W. Biosens Bioelectron. 2013;45:245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2013.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Singh V, Rodenbaugh C, Krishnan S. ACS Sens. 2016;1:437–443. doi: 10.1021/acssensors.5b00273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Singh V, Nerimetla R, Yang M, Krishnan S. ACS Sens. 2017;2:909–915. doi: 10.1021/acssensors.7b00124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang Y, Gao D, Zhang P, Gong P, Chen C, Gao G, Cai L. Chem Commun. 2014;50:811–813. doi: 10.1039/c3cc47649a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gough DA, Kumosa LS, Routh TL, Lin JT, Lucisano JY. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:42ra53. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]