Abstract

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are non-hematopoietic progenitor cells, which can be isolated from different types of tissues including bone marrow, adipose tissue, tooth pulp, and placenta/umbilical cord blood. There isolation from adult tissues circumvents the ethical concerns of working with embryonic or fetal stem cells, whilst still providing cells capable of differentiating into various cell lineages, such as adipocytes, osteocytes and chondrocytes. An important feature of MSCs is the low immunogenicity due to the lack of co-stimulatory molecules expression, meaning there is no need for immunosuppression during allogenic transplantation. The tropism of MSCs to damaged tissues and tumor sites makes them a promising vector for therapeutic agent delivery to tumors and metastatic niches. MSCs can be genetically modified by virus vectors to encode tumor suppressor genes, immunomodulating cytokines and their combinations, other therapeutic approaches include MSCs priming/loading with chemotherapeutic drugs or nanoparticles. MSCs derived membrane microvesicles (MVs), which play an important role in intercellular communication, are also considered as a new therapeutic agent and drug delivery vector. Recruited by the tumor, MSCs can exhibit both pro- and anti-oncogenic properties. In this regard, for the development of new methods for cancer therapy using MSCs, a deeper understanding of the molecular and cellular interactions between MSCs and the tumor microenvironment is necessary. In this review, we discuss MSC and tumor interaction mechanisms and review the new therapeutic strategies using MSCs and MSCs derived MVs for cancer treatment.

Keywords: mesenchymal stem cells, tumor microenvironment, membrane vesicles, cytokines, suppressor genes, oncolytic viruses, chemotherapy resistance

Introduction

Due to their tropism to the tumor niche, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are promising vectors for the delivery of antitumor agents. The isolation of MSCs from adult tissues poses circumvents many of the ethical and safety concerns which surround the use of embryonic or fetal stem cells, as these have been comprehensively discussed elsewhere (Herberts et al., 2011; Volarevic et al., 2018), this review focuses on the anti-tumor and therapeutic potential of MSCs. It is believed that the migration of MSCs toward the tumor is determined by inflammatory signaling similar to a chronic non-healing wound (Dvorak, 1986). It has been shown that MSCs are actively attracted to hepatic carcinoma (Xie et al., 2017), breast cancer (Ma et al., 2015), glioma (Smith et al., 2015) and pre-metastatic niches (Arvelo et al., 2016). However, the mechanism and factors responsible for the targeted tropism of MSCs to wounds and tumors microenvironments remain unclear. MSCs can migrate to sites of trauma and injury following the gradient of chemo-attractants in the extracellular matrix (ECM) and peripheral blood (Son et al., 2006) and local factors, such as hypoxia, cytokine environment and Toll-like receptors ligands, where upon arrival these local factors promote MSCs to express growth factors that accelerate tissue regeneration (Rustad and Gurtner, 2012).

It is believed, that following accumulation at the sites of tumor formation and growth, MSCs differentiate into pericytes or tumor-associated fibroblasts (TAF) thereby forming a growth supporting microenvironment and secreting such trophic factors as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), interleukin 8 (IL-8), transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), epidermal growth factor (EGF), and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF). (Nwabo Kamdje et al., 2017). For example, it has been shown that MSCs stimulate tumor growth and vascularization within the colorectal cancer xenograft model in vivo and can also induce activation of Akt and ERK in endothelial cells, thereby increasing their recruitment and angiogenic potential (Huang et al., 2013). Whilst in co-culture in vitro experiments, MSCs stimulated the invasion and proliferation of breast cancer cells (Pinilla et al., 2009).

However, besides tumor progression, MSCs can also supress tumor growth by cell cycle arrest and inhibition of proliferation, as well as blocking of PI3K/AKT pathway and tumor suppressor gene expression (Ramdasi et al., 2015). Anti-tumor properties are described for MSCs isolated from various sources in experiments both in vitro and in vivo of various tumor models (different tumor models are discussed in (Blatt et al., 2013a,b). For instance, MSCs injected into an in vivo model of Kaposi’s sarcoma suppressed tumor growth (Khakoo et al., 2006). Similar results have been reported for hepatoma (Qiao et al., 2008), pancreatic cancer (Cousin et al., 2009; Doi et al., 2010), prostate cancer (Chanda et al., 2009) and melanoma (Otsu et al., 2009) in both in vitro and in vivo models.

Thus, there are contradictory reports about the role of MSCs in tumor formation and development. The differences in the anticancer activity of MSCs reported by different group might be due to their activation status, which is discussed elsewhere (Rivera-Cruz et al., 2017). Nevertheless, there is a consensus that MSCs have enhanced tropism toward tumors which make them ideal vector candidates for targeted anti-tumor therapy.

MSCs Migrate Toward Irradiated Tumors

Mesenchymal stem cells migration in the context of radiation therapy may also be very promising for cancer therapy. In fact, MSCs migrate better to irradiated 4T1 mouse mammary tumor cells in comparison to non-irradiated 4T1 cells (Klopp et al., 2007). Irradiated 4T1 cells are characterized by increased expression levels of TGF-β1, VEGF, and PDGF-BB. The activation of chemokine receptor CCR2 in MSCs interacting with irradiated 4T1 cells was also observed, as well as higher expression of MCP-1/CCL2 in the tumor parenchyma of 4T1 mice. Thus, MCP-1/CCL2/CCR2 signaling is important in the attraction of MSCs to irradiated tumor cells. Furthermore, CCR2 inhibition resulted in a significant decrease in MSC migration in vitro (Klopp et al., 2007). In irradiated glioma cells Kim et al. (2010) reported increased IL-8 expression, which led to an upregulation of IL-8 receptor by MSCs and an increase in their migration potential and tropism to glioma cells.

Once at the irradiated tumor site, MSCs can suppress immune cell activation directly through cell-cell interactions by binding the membrane protein PD-1 with PD-L1 and PD-L2 ligands on the T-lymphocyte surface. Moreover, MSCs can induce T-lymphocyte agonism by suppressing the expression of CD80 and CD86 on antigen-presenting cells (Yan et al., 2014a,b). Thus, the increased MSCs tropism to irradiated tumors may have the opposite effect in cancer therapy.

The described data clearly illustrate the correlation between tissue damage and MSCs recruitment. Due to an increase in tropism to the tumor, genetically modified MSCs can be an effective therapeutic tool. However, such therapeutic strategies can be risky for cancer patients since MSCs can potentially stimulate cancer progression within certain contexts.

MSCs Chemotaxis Mediating Factors

Mesenchymal stem cells migrate to damaged tissue, trauma or sites of inflammation in response to secreted cytokines. Similarly, the tumor environment consists of a large number of immune cells, which alongside tumor cells, secrete soluble factors such as VEGF, PDGF, IL-8, IL-6, basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF or FGF2), stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1), granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF), monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP1), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), TGF-β and urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (UPAR), attracting MSCs (Ponte et al., 2007).

Soluble factors CCL21 (Sasaki et al., 2008), IL-8 (Birnbaum et al., 2007), CXC3L1 (Sordi et al., 2005), IL-6 (Liu et al., 2011), macrophage inflammatory protein 1δ (MIP-1δ) and MIP-3α (Lejmi et al., 2015) directly mediate MSCs chemotaxis and recruitment to damaged tissues. IL-6 mediates chemotaxis, which facilitates MSC attraction into the main tumor growth sites (Rattigan et al., 2010). Ringe et al. (2007) observed the dose-dependent chemotactic activity of bone marrow-derived MSCs in relation to SDF-1α and IL-8. IL-8 dependent recruitment of MSCs was also detected in glioma. A multitude of angiogenic cytokines secreted by glioma cells, including IL-8, actively attract MSCs to tumor tissue (Ringe et al., 2007). Experiments with conditioned medium from Huh-7 hepatoma cell (Huh-7 CM) showed that MIP-1δ and MIP-3α induced MSC migration. Moreover, after cultivation of MSCs in Huh-7 CM the expression of matrix metalloproteinase 1 (MMP-1), necessary for migration, was significantly increased (Lejmi et al., 2015). It was also shown that PDGF-BB, VEGF and TGF-β1 can induce MSC migration (Schar et al., 2015). Experiments using MSCs modified with CXCR4, showed that increased expression of the CXCR4 receptor enhances MSC migration toward tumor cells in both in vitro and in vivo models (Kalimuthu et al., 2017). In osteosarcoma models, it was described that SDF-1α is involved in MSCs recruitment to tumor areas. MSCs in turn stimulate the migration of osteocarcinoma cells by CCL5/RANTES secretion (Xu et al., 2009), thereby promoting tumor invasion and metastatic colonization by providing metastatic osteosarcoma cells with a suitable microenvironment (Tsukamoto et al., 2012).

Genetically Engineered MSCs With Anticancer Activity

In early studies MSCs genetically modified with interferon β (IFN-β) were injected into human melanoma mouse xenotransplantation models which resulted in decreased tumor growth and increased (2-times) survival of mice in comparison with controls (Studeny et al., 2002). In addition, it was shown in a melanoma xenograft mouse model that additional loading of IFN-β-modified canine MSCs with low amounts of cisplatin significantly increased the effectiveness of the antitumor therapy (Ahn et al., 2013).

Currently, besides IFN-β there are several other cytokines and tumor-suppressor genes with anticancer activity which are used for genetic modification of MSCs (Table 1). One of the most promising therapeutic pro-apoptotic cytokines is tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL), which selectively induces apoptosis in cancer cells. The antitumor effect of TRAIL-modified MSCs has been described for different types of tumors, within which TRAIL has not been found to be cytotoxic for normal mammalian cells and tissues (Szegezdi et al., 2009; Yuan et al., 2015). It is interesting that recombinant TNF-α-activated MSCs in combination with radiation exposure are able to significantly increase expression level of endogenous TRAIL (Mohammadpour et al., 2016). Long-lasting expression of endogenous TRAIL can also be observed in IFN-γ-modified MSCs (Yang X. et al., 2014). To increase the therapeutic potential of TRAIL-modified MSCs, it has been suggested they could be used in combination with chemotherapeutic agents, such as cisplatin (Zhang et al., 2012). However, some tumors have mechanism of TRAIL resistance through overexpression of X-linked inhibitory of apoptosis protein (XIAP), which inhibits caspase 3 and 9 activation. Anti-apoptotic properties of XIAP are under control of the second mitochondria-derived activator of caspase (Smac), which prevents physical interaction of XIAP and caspases thereby preventing apoptosis inhibition (Srinivasula et al., 2001). Khorashadizadeh et al. (2015) used MSCs for the delivery and simultaneous expression of novel cell penetrable forms of Smac and TRAIL. The effectiveness of this approach was shown in TRAIL-resistant breast cancer cell line MCF-7 (Khorashadizadeh et al., 2015).

Table 1.

The usage of genetically engineered Mesenchymal stem cells for target delivery of therapeutic agents with anti-tumor activity.

| Agent | Mechanism of action | Model | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| IFN-α | Immunostimulation, apoptosis induction, angiogenesis suppression | Immunocompetent mouse model of metastatic melanoma | Ren et al., 2008a |

| IFN-β | Increased activity of NK cells, inhibition of | Mouse 4T1 breast tumor model | Ling et al., 2010 |

| Stat3 signaling | Mouse prostate cancer lung metastasis model | Ren et al., 2008b | |

| PC-3 (prostate cancer) xenograft model | Wang et al., 2012 | ||

| PANC-1 (pancreatic carcinoma) xenograft model | Kidd et al., 2010 | ||

| IFN-γ | Immunostimulation, apoptosis induction | In vitro human leukemia cell line K562 | Li et al., 2006 |

| TRAIL | Caspase activation, apoptosis induction | Orthotopic model of Ewing sarcoma | Guiho et al., 2016 |

| Subcutaneous model of lung cancer | Mohr et al., 2008; Yan et al., 2016 | ||

| Xenograft model of human malignant mesothelioma | Sage et al., 2014; Lathrop et al., 2015 | ||

| Colo205 (colon cancer) xenograft tumor model | Marini et al., 2017 | ||

| Xenograft model of human myeloma | Cafforio et al., 2017 | ||

| Xenograft model of human tongue squamous cell carcinoma (TSCC) | Xia et al., 2015 | ||

| Eca-109 (esophageal cancer) xenograft model | Li et al., 2014 | ||

| Xenograft model of human glioma |

Kim et al., 2010; Choi et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2017 |

||

| IL-2 | Immunostimulation | Rat glioma model | Nakamura et al., 2004 |

| IL-12 | Immune system cell activation | Liver cancer H22 and MethA ascites models | Han et al., 2014 |

| Mouse model bearing subcutaneous SKOV3 (ovarian carcinoma) tumor explants | Zhao et al., 2011 | ||

| Xenograft model of human glioma | Hong et al., 2009; Ryu et al., 2011 | ||

| IL-21 | Immunostimulation | Mouse model of B-cell lymphoma | Kim et al., 2015 |

| A2780 (ovarian cancer) xenograft model | Hu et al., 2011 | ||

| PTEN | Induction of G(1)-phase cell cycle arrest | In vitro glioma cell line | Yang Z.S. et al., 2014; Guo et al., 2016 |

| CX3CL1 | Cytotoxic T cells and NK cells activation | Mice bearing lung metastases of C26 (colon carcinoma) and B16F10 (skin melanoma) cells | Xin et al., 2007 |

| HSV-TK/GCV | Drug precursors transformation | 9L (glioma) xenograft model | Uchibori et al., 2009 |

| In vitro glioma cell lines 8-MG-BA, 42-MG-BA and U-118 MG | Matuskova et al., 2010 | ||

| CD/5-FC | Drug precursors transformation | Subcutaneous model of melanoma or colon cancer | Kucerova et al., 2007, 2008 |

| Cal72 (osteosarcoma) xenograft model | NguyenThai et al., 2015 | ||

| NK4 | Apoptosis induction, angiogenesis and | C-26 lung metastasis model | Kanehira et al., 2007 |

| lymphangiogenesis suppression | Nude mice bearing gastric cancer xenografts | Zhu et al., 2014 | |

| MHCC-97H (liver carcinoma) xenograft model | Cai et al., 2017 | ||

| Oncolytic viruses | Tumor destruction by virus replication | Orthotopic breast and lung tumors | Hakkarainen et al., 2007 |

| Mouse glioblastoma multiforme models | Duebgen et al., 2014 | ||

| A375N (melanoma) tumor xenografts | Bolontrade et al., 2012 | ||

| PEDF | Inhibiting tumor angiogenesis, inducing apoptosis, | Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) xenograft model | Chen et al., 2012 |

| and restoring the VEGF-A/sFLT-1 ratio | Mice bearing U87 gliomas | Su et al., 2013 | |

| CT26 CRPC model | Yang et al., 2016 | ||

| Apoptin | Tumor destruction, caspase 3 activation | HepG2 (hepatocellular carcinoma) tumor xenografts | Zhang et al., 2016 |

| Lung carcinoma xenograft model | Du et al., 2015 | ||

| HNF4-α | Wnt/β-catenin pathway inhibition | SK-Hep-1 (hepatocellular carcinoma) tumor xenografts | Wu et al., 2016 |

| miR-124 | Increase the differentiation of glioma stem cells | Glioma tumor cells in a spheroid cell culture system | Lee et al., 2013 |

| by targeting SCP-1 or CDK6 | In vitro human glioblastoma multiforme cell line | Sharif et al., 2017 | |

| miR-145 | Sox2 and Oct4 expression inhibition | Glioma tumor cells in a spheroid cell culture system | Lee et al., 2013 |

Besides IFN-β and TRAIL as anti-tumor agents, interleukins are also under consideration because they regulate inflammation and immune responses For instance, IL-12-modified MSCs decrease metastasis and induce cancer cell apoptosis in mice with melanoma, lung cancer and hepatoma by 75, 83, and 91%, respectively. The activation of immune cells [cytotoxic T-lymphocytes and natural killers (NK)] was also reported (Chen et al., 2008). You et al. (2015) showed that injection of genetically modified amniotic fluid-derived MSCs expressing IL-2 resulted in induction of apoptosis in ovarian cancer cells in an in vivo mouse model.

PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10) is one of the main human tumor-suppressors. Yang Z.S. et al. (2014) showed that PTEN expressing MSCs are able to migrate toward DBTRG (brain glioblastoma) tumor cells in vitro. PTEN-modified MSCs anti-cancer activity in co-culture with U251 glioma cells in vitro was also described (Guo et al., 2016). MSC-mediated delivery and anti-tumor properties were described for other proteins (IFN-α, IFN-γ, CX3CL1, apoptin, PEDF) and ncRNAs (miR-124 and miR-145) (Table 1). Modification of MSCs for the co-expression of several therapeutic proteins can increase their anti-cancer potential. It was shown that TRAIL and herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (HSV-TK) modified MSCs in the presence of ganciclovir (GCV) significantly reduced tumor growth and increased survival of mice with highly malignant glioblastoma multiform (GBM) (Martinez-Quintanilla et al., 2013).

The effect of direct administration of many of these agents in cancer treatment is often limited due to their short half-life in the body and pronounced toxicity in relation to normal, non-cancerous cells. The use of MSCs for delivery of the above mentioned therapeutic proteins can help to minimize such problems because MSCs can selectively migrate to tumor sites and exert therapeutic effects locally thereby significantly increasing the concentration of the agent in the tumor and reducing its systemic toxicity.

Another promising approach is delivery of oncolytic viruses with MSCs. For instance, Du et al. (2017) used MSCs as a vector for the delivery of oncolytic herpes simplex virus (oHSV) [approved by Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for melanoma treatment] in human brain melanoma metastasis models in immunodeficient and immunocompetent mice. Authors noted that the introduced MSCs-oHSV migrated to the site of tumor formation and significantly prolonged the survival of mice. In the immunocompetent model a combination of MSCs-oHSV and PD-L1 blockade increases IFNγ-producing CD8+ tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes and results in a significant increase of the median survival of treated animals (Du et al., 2017).

MSCs Primed With Anticancer Drugs

Mesenchymal stem cells relative resistance to cytostatic and cytotoxic chemotherapeutic drugs and migration ability opens new ways to use them for targeted delivery of therapeutic drugs directly to tumor sites. Pessina et al. (1999) showed that SR4987 BDF/1 mouse bone marrow stromal cells can be a reservoir for doxorubicin (DOX) which can subsequently be released not only in the form of DOX metabolites but also in its original form. It was further shown that MSCs efficiently absorb and release paclitaxel (PTX) in an active form (Pascucci et al., 2014), DOX, and gemcitabine (GCB), all having an inhibitory effect on tongue squamous cell carcinoma (SCC154) cells growth in vitro (Cocce et al., 2017b).

Pessina et al. (2013) found that the maximum concentration of PTX which did not affect MSC viability was 10 000 ng/mL. The concentration is sufficient to decrease the viability of certain types of tumor cells, for example, human leukemia cells. In vivo investigations show that PTX-primed MSCs (MSCs-PTX) demonstrate strong antitumor activity inhibiting the growth of tumor cells and vascularization of the tumor in a MOLT-4 (leukemia) xenograft mouse model (Pessina et al., 2013). The anti-tumor activity of primed MSCs is currently being investigated on the different types of tumor cells. For instance, Bonomi et al. (2017b) showed that MSCs-PTX suppress the proliferation of human myeloma cells RPMI 8226 in in vitro 3D dynamic culture system. The anti-cancer activity of MSCs-PTX has been further shown in relation to pancreatic carcinoma cells in vitro (Brini et al., 2016).

Nicolay et al. (2016) showed that cisplatin (CDDP) had no significant effect on cell morphology, adhesion or induction of apoptosis in MSCs, nor does it affect their immunophenotype or differentiation potential of MSCs once primed with CDDP. This has been confirmed using CDDP at concentrations of 2.5 μg/ml and 5.0 μg/ml (Gilazieva et al., 2016). Thus, MSCs are promising vectors for CDDP delivery toward the tumor sites.

Beside chemical drugs in soluble form, MSCs can absorb nanomaterials containing chemotherapeutic agents. For instance, MSCs primed with silica nanoparticle-encapsulated DOX promoted a significant increase in the apoptosis of U251 glioma cells in vivo (Li et al., 2011).

Bonomi et al. (2017a) in their work used MSCs from two sources: dog adipose tissue and bone marrow, to study MSCs-PTX antitumor activity on human glioma cells (T98G and U87MG). The investigation once again showed the pronounced antitumor effect of MSCs-PTX and opens new perspectives for oncological disease therapy not only in humans but also in animals (Bonomi et al., 2017a).

MSC-Derived Microvesicles

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) [microvesicles (MVs) and exosomes] released by a large number of cells play an important role in intercellular communication. MVs from different cell types contain biologically active functional proteins, and nucleic acids including mRNA and microRNA (Pokharel et al., 2016). It was shown that MSC-derived MVs can promote progression of various types of tumors. For instance, MSC-derived MVs have been found to facilitate the migration of MCF7 breast cancer cells by activating the Wnt signaling pathway (Lin et al., 2013), promote the progression of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells (Shi et al., 2016) and increase the proliferation and metastatic potential of gastric cancer cells (Gu et al., 2016). MSC-derived MVs can also increase tumor cell resistance to drugs. For example, MSC-derived MVs can induce resistance to 5-fluorouracil in gastric cancer cells by activating the CaM-Ks/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway (Ji et al., 2015). Bliss et al. (2016) showed that a possible cause of increased resistance to chemotherapy are micro-RNAs which are included in MVs, such as miR-222/223, which support the resistance of the breast cancer cells in the bone marrow. However, there are conflicting results, for example Del Fattore et al. (2015) reported that MVs isolated from bone marrow and cord blood-derived MSCs suppressed division and induced apoptosis in glioblastoma cells. However, MVs isolated from adipose tissue-derived MSCs showed the opposite effect and stimulated tumor cell proliferation (Del Fattore et al., 2015). As mentioned above, such differences might be explained by activation status of parental MSCs from which the MVs are generated.

One of the possible approaches to use MSCs-isolated MVs in therapy is via the priming/loading of these structures with therapeutic agents. Pascucci et al. (2014) demonstrated that the antitumor activity of MSCs-PTX may be due to the release of a large number of MVs by the MScs. Loaded with PTX MSCs demonstrate vacuole-like structures and accumulation of MVs in extracellular space without significant change in cell morphology. Presence of PTX in MVs was confirmed by Fourier spectroscopy. The release of PTX containing MVs were found to exert anti-cancer activity which was confirmed using the human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell line CFPAC-1 in vitro (Pascucci et al., 2014). This finding was supported by the recent studies of Cocce et al. (2017a) which showed antitumor activity of MVs derived from MSCs-PTX and MSCs-GCB on pancreatic cancer cells in vitro.

Yuan et al. (2017) investigated antitumor activity of MSC-derived MVs carrying recombinant TRAIL (rTRAIL) on their surface. Cultivation of M231 breast cancer cells in the presence of MVs led to the induction of apoptosis in cancer cells. At the same time, MVs did not induce apoptosis in normal human bronchial epithelial cells (HBECs). The use of MSC-derived MVs bearing rTRAIL on their surface proved to be more effective than using pure rTRAIL (Yuan et al., 2017).

Kalimuthu et al. (2016) developed bioluminescent EVs using Renilla luciferase (Rluc)-expressing MSCs (EV-MSC/Rluc) and showed that these vesicles migrate at tumor sites in the Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) model in vivo. Significant cytotoxic effect of EV-MSC/Rluc on LLC and 4T1 cells in vitro was also noticed. Moreover, EV-MSC/Rluc inhibited LLC tumor growth in vivo (Kalimuthu et al., 2016).

Conclusion

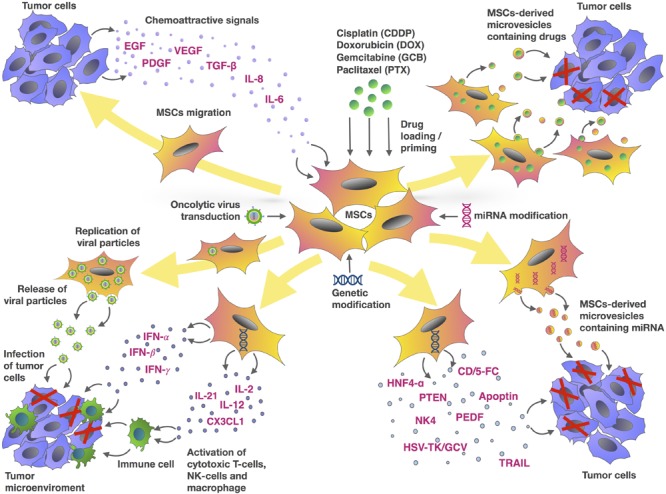

Tumor development and response to therapy depends not only on tumor cells, but also on different cell types which form the stroma and microenvironment. These include immune cells, vascular endothelial cells and tumor-associated stromal cells such as TAF and MSCs. Due to tropism to the tumor microenvironment, MSCs can be considered as promising vectors for the delivery of antitumor agents (Figure 1). To date, there are large number of experimental studies that confirm the anti-oncogenic potential of MSCs modified with therapeutic genes and/or loaded with chemotherapeutic drugs. Thus, the approach of therapeutic agent delivery to the tumor sites using MSCs is promising. However, since it is known that native MSCs can exhibit not only anticancer but also pro-oncogenic properties, further research is needed to improve the safety of this approach. An alternative to using intact MSCs to deliver anti-tumor agents, is the use of MSC-derived MVs which can also be loaded with the same antitumor agents. Further research is needed to evaluate the safety and efficiency of the different therapeutic approaches described in this review to harness the promising potential of MSCs as therapeutic vectors.

FIGURE 1.

Mesenchymal stem cells and tumor cells interaction as an MSC-based approach for cancer therapy. The chemotactic movement of MSCs toward a tumor niche is driven by soluble factors, such as VEGF, PDGF, IL-8, IL-6, bFGF or FGF2, SDF-1, G-CSF, GM-CSF, MCP1, HGF, TGF-β, and UPAR. Genetic modification of MSCs can be used to deliver a range of tumor-suppressing cargos directly into the tumor niche. These cargos include tumor suppressor (TRAIL, PTEN, HSV-TK/GCV, CD/5-FC, NK4, PEDF, apoptin, HNF4-α), oncolytic viruses, immune-modulating agents (IFN-α, IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-12, IL-21, IFN-β, CX3CL1), and regulators of gene expression (miRNAs and other non-coding RNAs). MSCs are also capable of delivering therapeutic drugs such as DOX, PTX, GCB, and CDDP within the tumor site. In addition to using MSCs directly, microvesicles (MVs) isolated from MSCs represent an alternative approach to delivering these agents.

Author Contributions

DC wrote the manuscript and made the table. KK and VJ collected the data of homing of MSCs. LT collected the information of MSCs priming. KK made the figure. DC, VS, and AR conceived the idea and edited the manuscript, figure, and table.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This study was supported by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research grant 16-34-60201. The work was performed according to the Russian Government Program of Competitive Growth of Kazan Federal University. AR was supported by state assignment 20.5175.2017/6.7 of the Ministry of Education and Science of Russian Federation.

References

- Ahn J., Lee H., Seo K., Kang S., Ra J., Youn H. (2013). Anti-tumor effect of adipose tissue derived-mesenchymal stem cells expressing interferon-beta and treatment with cisplatin in a xenograft mouse model for canine melanoma. PLoS One 8:e74897. 10.1371/journal.pone.0074897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvelo F., Sojo F., Cotte C. (2016). Tumour progression and metastasis. Ecancermedicalscience 10:617 10.3332/ecancer.2016.617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum T., Roider J., Schankin C. J., Padovan C. S., Schichor C., Goldbrunner R., et al. (2007). Malignant gliomas actively recruit bone marrow stromal cells by secreting angiogenic cytokines. J. Neurooncol. 83 241–247. 10.1007/s11060-007-9332-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatt N. L., Mingaleeva R. N., Khaiboullina S. F., Kotlyar A., Lombardi V. C., Rizvanov A. A. (2013a). In vivo screening models of anticancer drugs. Life Sci. J. 10 1892–1900. [Google Scholar]

- Blatt N. L., Mingaleeva R. N., Khaiboullina S. F., Lombardi V. C., Rizvanov A. A. (2013b). Application of cell and tissue culture systems for anticancer drug screening. World Appl. Sci. J. 23 315–325. 10.5829/idosi.wasj.2013.23.03.13064 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bliss S. A., Sinha G., Sandiford O. A., Williams L. M., Engelberth D. J., Guiro K., et al. (2016). Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes stimulate cycling quiescence and early breast cancer dormancy in bone marrow. Cancer Res. 76 5832–5844. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolontrade M. F., Sganga L., Piaggio E., Viale D. L., Sorrentino M. A., Robinson A., et al. (2012). A specific subpopulation of mesenchymal stromal cell carriers overrides melanoma resistance to an oncolytic adenovirus. Stem Cells Dev. 21 2689–2702. 10.1089/scd.2011.0643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonomi A., Ghezzi E., Pascucci L., Aralla M., Ceserani V., Pettinari L., et al. (2017a). Effect of canine mesenchymal stromal cells loaded with paclitaxel on growth of canine glioma and human glioblastoma cell lines. Vet. J. 223 41–47. 10.1016/j.tvjl.2017.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonomi A., Steimberg N., Benetti A., Berenzi A., Alessandri G., Pascucci L., et al. (2017b). Paclitaxel-releasing mesenchymal stromal cells inhibit the growth of multiple myeloma cells in a dynamic 3D culture system. Hematol. Oncol. 35 693–702. 10.1002/hon.2306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brini A. T., Cocce V., Ferreira L. M., Giannasi C., Cossellu G., Gianni A. B., et al. (2016). Cell-mediated drug delivery by gingival interdental papilla mesenchymal stromal cells (GinPa-MSCs) loaded with paclitaxel. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 13 789–798. 10.1517/17425247.2016.1167037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cafforio P., Viggiano L., Mannavola F., Pelle E., Caporusso C., Maiorano E., et al. (2017). pIL6-TRAIL-engineered umbilical cord mesenchymal/stromal stem cells are highly cytotoxic for myeloma cells both in vitro and in vivo. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 8:206. 10.1186/s13287-017-0655-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai C., Hou L., Zhang J., Zhao D., Wang Z., Hu H., et al. (2017). The inhibitory effect of mesenchymal stem cells with rAd-NK4 on liver cancer. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 183 444–459. 10.1007/s12010-017-2456-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanda D., Isayeva T., Kumar S., Hensel J. A., Sawant A., Ramaswamy G., et al. (2009). Therapeutic potential of adult bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in prostate cancer bone metastasis. Clin. Cancer Res. 15 7175–7185. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q., Cheng P., Yin T., He H., Yang L., Wei Y., et al. (2012). Therapeutic potential of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells producing pigment epithelium-derived factor in lung carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Med. 30 527–534. 10.3892/ijmm.2012.1015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Lin X., Zhao J., Shi W., Zhang H., Wang Y., et al. (2008). A tumor-selective biotherapy with prolonged impact on established metastases based on cytokine gene-engineered MSCs. Mol. Ther. 16 749–756. 10.1038/mt.2008.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S. A., Hwang S. K., Wang K. C., Cho B. K., Phi J. H., Lee J. Y., et al. (2011). Therapeutic efficacy and safety of TRAIL-producing human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells against experimental brainstem glioma. Neuro Oncol. 13 61–69. 10.1093/neuonc/noq147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocce V., Balducci L., Falchetti M. L., Pascucci L., Ciusani E., Brini A. T., et al. (2017a). Fluorescent immortalized human adipose derived stromal cells (hASCs-TS/GFP+) for studying cell drug delivery mediated by microvesicles. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 17 1578–1585. 10.2174/1871520617666170327113932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocce V., Farronato D., Brini A. T., Masia C., Gianni A. B., Piovani G., et al. (2017b). Drug loaded gingival mesenchymal stromal cells (GinPa-MSCs) inhibit in vitro proliferation of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 7:9376. 10.1038/s41598-017-09175-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousin B., Ravet E., Poglio S., De Toni F., Bertuzzi M., Lulka H., et al. (2009). Adult stromal cells derived from human adipose tissue provoke pancreatic cancer cell death both in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One 4:e6278. 10.1371/journal.pone.0006278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Fattore A., Luciano R., Saracino R., Battafarano G., Rizzo C., Pascucci L., et al. (2015). Differential effects of extracellular vesicles secreted by mesenchymal stem cells from different sources on glioblastoma cells. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 15 495–504. 10.1517/14712598.2015.997706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doi C., Maurya D. K., Pyle M. M., Troyer D., Tamura M. (2010). Cytotherapy with naive rat umbilical cord matrix stem cells significantly attenuates growth of murine pancreatic cancer cells and increases survival in syngeneic mice. Cytotherapy 12 408–417. 10.3109/14653240903548194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J., Zhang Y., Xu C., Xu X. (2015). Apoptin-modified human mesenchymal stem cells inhibit growth of lung carcinoma in nude mice. Mol. Med. Rep. 12 1023–1029. 10.3892/mmr.2015.3501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du W., Seah I., Bougazzoul O., Choi G., Meeth K., Bosenberg M. W., et al. (2017). Stem cell-released oncolytic herpes simplex virus has therapeutic efficacy in brain metastatic melanomas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114 E6157–E6165. 10.1073/pnas.1700363114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duebgen M., Martinez-Quintanilla J., Tamura K., Hingtgen S., Redjal N., Wakimoto H., et al. (2014). Stem cells loaded with multimechanistic oncolytic herpes simplex virus variants for brain tumor therapy. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 106:dju090. 10.1093/jnci/dju090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak H. F. (1986). Tumors: wounds that do not heal. Similarities between tumor stroma generation and wound healing. N. Engl. J. Med. 315 1650–1659. 10.1056/NEJM198612253152606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilazieva Z. E., Tazetdinova L. G., Arkhipova S. S., Solovyeva V. V., Rizvanov A. A. (2016). Effect of cisplatin on ultrastructure and viability of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells. BioNanoScience 6 534–539. 10.1007/s12668-016-0283-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gu H., Ji R., Zhang X., Wang M., Zhu W., Qian H., et al. (2016). Exosomes derived from human mesenchymal stem cells promote gastric cancer cell growth and migration via the activation of the Akt pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 14 3452–3458. 10.3892/mmr.2016.5625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guiho R., Biteau K., Grisendi G., Taurelle J., Chatelais M., Gantier M., et al. (2016). TRAIL delivered by mesenchymal stromal/stem cells counteracts tumor development in orthotopic Ewing sarcoma models. Int. J. Cancer 139 2802–2811. 10.1002/ijc.30402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X. R., Hu Q. Y., Yuan Y. H., Tang X. J., Yang Z. S., Zou D. D., et al. (2016). PTEN-mRNA engineered mesenchymal stem cell-mediated cytotoxic effects on U251 glioma cells. Oncol. Lett. 11 2733–2740. 10.3892/ol.2016.4297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakkarainen T., Sarkioja M., Lehenkari P., Miettinen S., Ylikomi T., Suuronen R., et al. (2007). Human mesenchymal stem cells lack tumor tropism but enhance the antitumor activity of oncolytic adenoviruses in orthotopic lung and breast tumors. Hum. Gene Ther. 18 627–641. 10.1089/hum.2007.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J., Zhao J., Xu J., Wen Y. (2014). Mesenchymal stem cells genetically modified by lentivirus-mediated interleukin-12 inhibit malignant ascites in mice. Exp. Ther. Med. 8 1330–1334. 10.3892/etm.2014.1918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herberts C. A., Kwa M. S., Hermsen H. P. (2011). Risk factors in the development of stem cell therapy. J. Transl. Med. 9:29. 10.1186/1479-5876-9-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong X., Miller C., Savant-Bhonsale S., Kalkanis S. N. (2009). Antitumor treatment using interleukin- 12-secreting marrow stromal cells in an invasive glioma model. Neurosurgery 64 1139–1146; discussion 1146–1147. 10.1227/01.NEU.0000345646.85472.EA [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W., Wang J., He X., Zhang H., Yu F., Jiang L., et al. (2011). Human umbilical blood mononuclear cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells serve as interleukin-21 gene delivery vehicles for epithelial ovarian cancer therapy in nude mice. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 58 397–404. 10.1002/bab.63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W. H., Chang M. C., Tsai K. S., Hung M. C., Chen H. L., Hung S. C. (2013). Mesenchymal stem cells promote growth and angiogenesis of tumors in mice. Oncogene 32 4343–4354. 10.1038/onc.2012.458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji R., Zhang B., Zhang X., Xue J., Yuan X., Yan Y., et al. (2015). Exosomes derived from human mesenchymal stem cells confer drug resistance in gastric cancer. Cell Cycle 14 2473–2483. 10.1080/15384101.2015.1005530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalimuthu S., Gangadaran P., Li X. J., Oh J. M., Lee H. W., Jeong S. Y., et al. (2016). In Vivo therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles with optical imaging reporter in tumor mice model. Sci. Rep. 6:30418. 10.1038/srep30418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalimuthu S., Oh J. M., Gangadaran P., Zhu L., Lee H. W., Rajendran R. L., et al. (2017). In vivo tracking of chemokine receptor CXCR4-engineered mesenchymal stem cell migration by optical molecular imaging. Stem Cells Int. 2017:8085637. 10.1155/2017/8085637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehira M., Xin H., Hoshino K., Maemondo M., Mizuguchi H., Hayakawa T., et al. (2007). Targeted delivery of NK4 to multiple lung tumors by bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Cancer Gene Ther. 14 894–903. 10.1038/sj.cgt.7701079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khakoo A. Y., Pati S., Anderson S. A., Reid W., Elshal M. F., Rovira I. I., et al. (2006). Human mesenchymal stem cells exert potent antitumorigenic effects in a model of Kaposi’s sarcoma. J. Exp. Med. 203 1235–1247. 10.1084/jem.20051921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khorashadizadeh M., Soleimani M., Khanahmad H., Fallah A., Naderi M., Khorramizadeh M. (2015). Bypassing the need for pre-sensitization of cancer cells for anticancer TRAIL therapy with secretion of novel cell penetrable form of Smac from hA-MSCs as cellular delivery vehicle. Tumour Biol. 36 4213–4221. 10.1007/s13277-015-3058-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd S., Caldwell L., Dietrich M., Samudio I., Spaeth E. L., Watson K., et al. (2010). Mesenchymal stromal cells alone or expressing interferon-beta suppress pancreatic tumors in vivo, an effect countered by anti-inflammatory treatment. Cytotherapy 12 615–625. 10.3109/14653241003631815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim N., Nam Y. S., Im K. I., Lim J. Y., Lee E. S., Jeon Y. W., et al. (2015). IL-21-expressing mesenchymal stem cells prevent lethal B-cell lymphoma through efficient delivery of IL-21, which redirects the immune system to target the tumor. Stem Cells Dev. 24 2808–2821. 10.1089/scd.2015.0103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. M., Oh J. H., Park S. A., Ryu C. H., Lim J. Y., Kim D. S., et al. (2010). Irradiation enhances the tumor tropism and therapeutic potential of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-secreting human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells in glioma therapy. Stem Cells 28 2217–2228. 10.1002/stem.543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klopp A. H., Spaeth E. L., Dembinski J. L., Woodward W. A., Munshi A., Meyn R. E., et al. (2007). Tumor irradiation increases the recruitment of circulating mesenchymal stem cells into the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res. 67 11687–11695. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucerova L., Altanerova V., Matuskova M., Tyciakova S., Altaner C. (2007). Adipose tissue-derived human mesenchymal stem cells mediated prodrug cancer gene therapy. Cancer Res. 67 6304–6313. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucerova L., Matuskova M., Pastorakova A., Tyciakova S., Jakubikova J., Bohovic R., et al. (2008). Cytosine deaminase expressing human mesenchymal stem cells mediated tumour regression in melanoma bearing mice. J. Gene Med. 10 1071–1082. 10.1002/jgm.1239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lathrop M. J., Sage E. K., Macura S. L., Brooks E. M., Cruz F., Bonenfant N. R., et al. (2015). Antitumor effects of TRAIL-expressing mesenchymal stromal cells in a mouse xenograft model of human mesothelioma. Cancer Gene Ther. 22 44–54. 10.1038/cgt.2014.68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. K., Finniss S., Cazacu S., Bucris E., Ziv-Av A., Xiang C., et al. (2013). Mesenchymal stem cells deliver synthetic microRNA mimics to glioma cells and glioma stem cells and inhibit their cell migration and self-renewal. Oncotarget 4 346–361. 10.18632/oncotarget.868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejmi E., Perriraz N., Clement S., Morel P., Baertschiger R., Christofilopoulos P., et al. (2015). Inflammatory chemokines MIP-1delta and MIP-3alpha are involved in the migration of multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells induced by hepatoma cells. Stem Cells Dev. 24 1223–1235. 10.1089/scd.2014.0176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Guan Y., Liu H., Hao N., Liu T., Meng X., et al. (2011). Silica nanorattle-doxorubicin-anchored mesenchymal stem cells for tumor-tropic therapy. ACS Nano 5 7462–7470. 10.1021/nn202399w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Li F., Tian H., Yue W., Li S., Chen G. (2014). Human mesenchymal stem cells with adenovirus-mediated TRAIL gene transduction have antitumor effects on esophageal cancer cell line Eca-109. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 46 471–476. 10.1093/abbs/gmu024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Lu Y., Huang W., Xu H., Chen X., Geng Q., et al. (2006). In vitro effect of adenovirus-mediated human Gamma Interferon gene transfer into human mesenchymal stem cells for chronic myelogenous leukemia. Hematol. Oncol. 24 151–158. 10.1002/hon.779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin R., Wang S., Zhao R. C. (2013). Exosomes from human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells promote migration through Wnt signaling pathway in a breast cancer cell model. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 383 13–20. 10.1007/s11010-013-1746-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling X., Marini F., Konopleva M., Schober W., Shi Y., Burks J., et al. (2010). Mesenchymal stem cells overexpressing IFN-beta inhibit breast cancer growth and metastases through Stat3 signaling in a syngeneic tumor model. Cancer Microenviron. 3 83–95. 10.1007/s12307-010-0041-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Ginestier C., Ou S. J., Clouthier S. G., Patel S. H., Monville F., et al. (2011). Breast cancer stem cells are regulated by mesenchymal stem cells through cytokine networks. Cancer Res. 71 614–624. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma F., Chen D., Chen F., Chi Y., Han Z., Feng X., et al. (2015). Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells promote breast cancer metastasis by interleukin-8- and interleukin-6-dependent induction of CD44+/CD24- cells. Cell Transplant. 24 2585–2599. 10.3727/096368915X687462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marini I., Siegemund M., Hutt M., Kontermann R. E., Pfizenmaier K. (2017). Antitumor activity of a mesenchymal stem cell line stably secreting a tumor-targeted TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand fusion protein. Front. Immunol. 8:536. 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Quintanilla J., Bhere D., Heidari P., He D., Mahmood U., Shah K. (2013). Therapeutic efficacy and fate of bimodal engineered stem cells in malignant brain tumors. Stem Cells 31 1706–1714. 10.1002/stem.1355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matuskova M., Hlubinova K., Pastorakova A., Hunakova L., Altanerova V., Altaner C., et al. (2010). HSV-tk expressing mesenchymal stem cells exert bystander effect on human glioblastoma cells. Cancer Lett. 290 58–67. 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.08.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadpour H., Pourfathollah A. A., Nikougoftar Zarif M., Shahbazfar A. A. (2016). Irradiation enhances susceptibility of tumor cells to the antitumor effects of TNF-alpha activated adipose derived mesenchymal stem cells in breast cancer model. Sci. Rep. 6:28433. 10.1038/srep28433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr A., Lyons M., Deedigan L., Harte T., Shaw G., Howard L., et al. (2008). Mesenchymal stem cells expressing TRAIL lead to tumour growth inhibition in an experimental lung cancer model. J. Cell Mol. Med. 12 2628–2643. 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00317.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K., Ito Y., Kawano Y., Kurozumi K., Kobune M., Tsuda H., et al. (2004). Antitumor effect of genetically engineered mesenchymal stem cells in a rat glioma model. Gene Ther. 11 1155–1164. 10.1038/sj.gt.3302276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NguyenThai Q. A., Sharma N., Luong do H., Sodhi S. S., Kim J. H., Kim N., et al. (2015). Targeted inhibition of osteosarcoma tumor growth by bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells expressing cytosine deaminase/5-fluorocytosine in tumor-bearing mice. J. Gene Med. 17 87–99. 10.1002/jgm.2826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolay N. H., Lopez Perez R., Ruhle A., Trinh T., Sisombath S., Weber K. J., et al. (2016). Mesenchymal stem cells maintain their defining stem cell characteristics after treatment with cisplatin. Sci. Rep. 6:20035. 10.1038/srep20035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nwabo Kamdje A. H., Kamga P. T., Simo R. T., Vecchio L., Seke Etet P. F., Muller J. M., et al. (2017). Mesenchymal stromal cells’ role in tumor microenvironment: involvement of signaling pathways. Cancer Biol. Med. 14 129–141. 10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2016.0033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsu K., Das S., Houser S. D., Quadri S. K., Bhattacharya S., Bhattacharya J. (2009). Concentration-dependent inhibition of angiogenesis by mesenchymal stem cells. Blood 113 4197–4205. 10.1182/blood-2008-09-176198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascucci L., Cocce V., Bonomi A., Ami D., Ceccarelli P., Ciusani E., et al. (2014). Paclitaxel is incorporated by mesenchymal stromal cells and released in exosomes that inhibit in vitro tumor growth: a new approach for drug delivery. J. Control. Release 192 262–270. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.07.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessina A., Cocce V., Pascucci L., Bonomi A., Cavicchini L., Sisto F., et al. (2013). Mesenchymal stromal cells primed with Paclitaxel attract and kill leukaemia cells, inhibit angiogenesis and improve survival of leukaemia-bearing mice. Br. J. Haematol. 160 766–778. 10.1111/bjh.12196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessina A., Piccirillo M., Mineo E., Catalani P., Gribaldo L., Marafante E., et al. (1999). Role of SR-4987 stromal cells in the modulation of doxorubicin toxicity to in vitro granulocyte-macrophage progenitors (CFU-GM). Life Sci. 65 513–523. 10.1016/S0024-3205(99)00272-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinilla S., Alt E., Abdul Khalek F. J., Jotzu C., Muehlberg F., Beckmann C., et al. (2009). Tissue resident stem cells produce CCL5 under the influence of cancer cells and thereby promote breast cancer cell invasion. Cancer Lett. 284 80–85. 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokharel D., Wijesinghe P., Oenarto V., Lu J. F., Sampson D. D., Kennedy B. F., et al. (2016). Deciphering cell-to-cell communication in acquisition of cancer traits: extracellular membrane vesicles are regulators of tissue biomechanics. OMICS 20 462–469. 10.1089/omi.2016.0072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponte A. L., Marais E., Gallay N., Langonne A., Delorme B., Herault O., et al. (2007). The in vitro migration capacity of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells: comparison of chemokine and growth factor chemotactic activities. Stem Cells 25 1737–1745. 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao L., Xu Z., Zhao T., Zhao Z., Shi M., Zhao R. C., et al. (2008). Suppression of tumorigenesis by human mesenchymal stem cells in a hepatoma model. Cell Res. 18 500–507. 10.1038/cr.2008.40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramdasi S., Sarang S., Viswanathan C. (2015). Potential of mesenchymal stem cell based application in cancer. Int. J. Hematol. Oncol. Stem Cell Res. 9 95–103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattigan Y., Hsu J. M., Mishra P. J., Glod J., Banerjee D. (2010). Interleukin 6 mediated recruitment of mesenchymal stem cells to the hypoxic tumor milieu. Exp. Cell Res. 316 3417–3424. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren C., Kumar S., Chanda D., Chen J., Mountz J. D., Ponnazhagan S. (2008a). Therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells producing interferon-alpha in a mouse melanoma lung metastasis model. Stem Cells 26 2332–2338. 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren C., Kumar S., Chanda D., Kallman L., Chen J., Mountz J. D., et al. (2008b). Cancer gene therapy using mesenchymal stem cells expressing interferon-beta in a mouse prostate cancer lung metastasis model. Gene Ther. 15 1446–1453. 10.1038/gt.2008.101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringe J., Strassburg S., Neumann K., Endres M., Notter M., Burmester G. R., et al. (2007). Towards in situ tissue repair: human mesenchymal stem cells express chemokine receptors CXCR1, CXCR2 and CCR2, and migrate upon stimulation with CXCL8 but not CCL2. J. Cell. Biochem. 101 135–146. 10.1002/jcb.21172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Cruz C. M., Shearer J. J., Figueiredo Neto M., Figueiredo M. L. (2017). The immunomodulatory effects of mesenchymal stem cell polarization within the tumor microenvironment niche. Stem Cells Int. 2017:4015039. 10.1155/2017/4015039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rustad K. C., Gurtner G. C. (2012). Mesenchymal stem cells home to sites of injury and inflammation. Adv. Wound Care 1 147–152. 10.1089/wound.2011.0314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu C. H., Park S. H., Park S. A., Kim S. M., Lim J. Y., Jeong C. H., et al. (2011). Gene therapy of intracranial glioma using interleukin 12-secreting human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Hum. Gene Ther. 22 733–743. 10.1089/hum.2010.187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage E. K., Kolluri K. K., McNulty K., Lourenco Sda S., Kalber T. L., Ordidge K. L., et al. (2014). Systemic but not topical TRAIL-expressing mesenchymal stem cells reduce tumour growth in malignant mesothelioma. Thorax 69 638–647. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-204110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki M., Abe R., Fujita Y., Ando S., Inokuma D., Shimizu H. (2008). Mesenchymal stem cells are recruited into wounded skin and contribute to wound repair by transdifferentiation into multiple skin cell type. J. Immunol. 180 2581–2587. 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schar M. O., Diaz-Romero J., Kohl S., Zumstein M. A., Nesic D. (2015). Platelet-rich concentrates differentially release growth factors and induce cell migration in vitro. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 473 1635–1643. 10.1007/s11999-015-4192-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharif S., Ghahremani M. H., Soleimani M. (2017). Delivery of exogenous miR-124 to glioblastoma multiform cells by Wharton’s jelly mesenchymal stem cells decreases cell proliferation and migration, and confers chemosensitivity. Stem Cell Rev. 10.1007/s12015-017-9788-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi S., Zhang Q., Xia Y., You B., Shan Y., Bao L., et al. (2016). Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes facilitate nasopharyngeal carcinoma progression. Am. J. Cancer Res. 6 459–472. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C. L., Chaichana K. L., Lee Y. M., Lin B., Stanko K. M., O’Donnell T., et al. (2015). Pre-exposure of human adipose mesenchymal stem cells to soluble factors enhances their homing to brain cancer. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 4 239–251. 10.5966/sctm.2014-0149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son B. R., Marquez-Curtis L. A., Kucia M., Wysoczynski M., Turner A. R., Ratajczak J., et al. (2006). Migration of bone marrow and cord blood mesenchymal stem cells in vitro is regulated by stromal-derived factor-1-CXCR4 and hepatocyte growth factor-c-met axes and involves matrix metalloproteinases. Stem Cells 24 1254–1264. 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sordi V., Malosio M. L., Marchesi F., Mercalli A., Melzi R., Giordano T., et al. (2005). Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells express a restricted set of functionally active chemokine receptors capable of promoting migration to pancreatic islets. Blood 106 419–427. 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasula S. M., Hegde R., Saleh A., Datta P., Shiozaki E., Chai J., et al. (2001). A conserved XIAP-interaction motif in caspase-9 and Smac/DIABLO regulates caspase activity and apoptosis. Nature 410 112–116. 10.1038/35065125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studeny M., Marini F. C., Champlin R. E., Zompetta C., Fidler I. J., Andreeff M. (2002). Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells as vehicles for interferon-beta delivery into tumors. Cancer Res. 62 3603–3608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su H., Li J., Osinska H., Li F., Robbins J., Liu J., et al. (2013). The COP9 signalosome is required for autophagy, proteasome-mediated proteolysis, and cardiomyocyte survival in adult mice. Circ. Heart Fail. 6 1049–1057. 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szegezdi E., O’Reilly A., Davy Y., Vawda R., Taylor D. L., Murphy M., et al. (2009). Stem cells are resistant to TRAIL receptor-mediated apoptosis. J. Cell Mol. Med. 13 4409–4414. 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00522.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto S., Honoki K., Fujii H., Tohma Y., Kido A., Mori T., et al. (2012). Mesenchymal stem cells promote tumor engraftment and metastatic colonization in rat osteosarcoma model. Int. J. Oncol. 40 163–169. 10.3892/ijo.2011.1220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchibori R., Okada T., Ito T., Urabe M., Mizukami H., Kume A., et al. (2009). Retroviral vector-producing mesenchymal stem cells for targeted suicide cancer gene therapy. J. Gene Med. 11 373–381. 10.1002/jgm.1313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volarevic V., Markovic B. S., Gazdic M., Volarevic A., Jovicic N., Arsenijevic N., et al. (2018). Ethical and safety issues of stem cell-based therapy. Int. J. Med. Sci. 15 36–45. 10.7150/ijms.21666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G. X., Zhan Y. A., Hu H. L., Wang Y., Fu B. (2012). Mesenchymal stem cells modified to express interferon-beta inhibit the growth of prostate cancer in a mouse model. J. Int. Med. Res. 40 317–327. 10.1177/147323001204000132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. J., Xiang B. Y., Ding Y. H., Chen L., Zou H., Mou X. Z., et al. (2017). Human menstrual blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells as a cellular vehicle for malignant glioma gene therapy. Oncotarget 8 58309–58321. 10.18632/oncotarget.17621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu N., Zhang Y. L., Wang H. T., Li D. W., Dai H. J., Zhang Q. Q., et al. (2016). Overexpression of hepatocyte nuclear factor 4alpha in human mesenchymal stem cells suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma development through Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway downregulation. Cancer Biol. Ther. 17 558–565. 10.1080/15384047.2016.1177675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia L., Peng R., Leng W., Jia R., Zeng X., Yang X., et al. (2015). TRAIL-expressing gingival-derived mesenchymal stem cells inhibit tumorigenesis of tongue squamous cell carcinoma. J. Dent. Res. 94 219–228. 10.1177/0022034514557815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie C., Yang Z., Suo Y., Chen Q., Wei D., Weng X., et al. (2017). Systemically infused mesenchymal stem cells show different homing profiles in healthy and tumor mouse models. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 6 1120–1131. 10.1002/sctm.16-0204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin H., Kanehira M., Mizuguchi H., Hayakawa T., Kikuchi T., Nukiwa T., et al. (2007). Targeted delivery of CX3CL1 to multiple lung tumors by mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells 25 1618–1626. 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W. T., Bian Z. Y., Fan Q. M., Li G., Tang T. T. (2009). Human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) target osteosarcoma and promote its growth and pulmonary metastasis. Cancer Lett. 281 32–41. 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan C., Song X., Yu W., Wei F., Li H., Lv M., et al. (2016). Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells delivering sTRAIL home to lung cancer mediated by MCP-1/CCR2 axis and exhibit antitumor effects. Tumour Biol. 37 8425–8435. 10.1007/s13277-015-4746-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Z., Zhuansun Y., Chen R., Li J., Ran P. (2014a). Immunomodulation of mesenchymal stromal cells on regulatory T cells and its possible mechanism. Exp. Cell Res. 324 65–74. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Z., Zhuansun Y., Liu G., Chen R., Li J., Ran P. (2014b). Mesenchymal stem cells suppress T cells by inducing apoptosis and through PD-1/B7-H1 interactions. Immunol. Lett. 162(1 Pt A) 248–255. 10.1016/j.imlet.2014.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Zhang Y., Cheng L., Yue D., Ma J., Zhao D., et al. (2016). Mesenchymal stem cells engineered to secrete pigment epithelium-derived factor inhibit tumor metastasis and the formation of malignant ascites in a murine colorectal peritoneal carcinomatosis model. Hum. Gene Ther. 27 267–277. 10.1089/hum.2015.135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X., Du J., Xu X., Xu C., Song W. (2014). IFN-gamma-secreting-mesenchymal stem cells exert an antitumor effect in vivo via the TRAIL pathway. J. Immunol. Res. 2014:318098. 10.1155/2014/318098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. S., Tang X. J., Guo X. R., Zou D. D., Sun X. Y., Feng J. B., et al. (2014). Cancer cell-oriented migration of mesenchymal stem cells engineered with an anticancer gene (PTEN): an imaging demonstration. Onco Targets Ther. 7 441–446. 10.2147/OTT.S59227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You Q., Yao Y., Zhang Y., Fu S., Du M., Zhang G. (2015). Effect of targeted ovarian cancer therapy using amniotic fluid mesenchymal stem cells transfected with enhanced green fluorescent protein-human interleukin-2 in vivo. Mol. Med. Rep. 12 4859–4866. 10.3892/mmr.2015.4076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Z., Kolluri K. K., Gowers K. H., Janes S. M. (2017). TRAIL delivery by MSC-derived extracellular vesicles is an effective anticancer therapy. J. Extracell. Vesicles 6:1265291. 10.1080/20013078.2017.1265291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Z., Kolluri K. K., Sage E. K., Gowers K. H., Janes S. M. (2015). Mesenchymal stromal cell delivery of full-length tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand is superior to soluble type for cancer therapy. Cytotherapy 17 885–896. 10.1016/j.jcyt.2015.03.603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B., Shan H., Li D., Li Z. R., Zhu K. S., Jiang Z. B. (2012). The inhibitory effect of MSCs expressing TRAIL as a cellular delivery vehicle in combination with cisplatin on hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Biol. Ther. 13 1175–1184. 10.4161/cbt.21347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Hou L., Wu X., Zhao D., Wang Z., Hu H., et al. (2016). Inhibitory effect of genetically engineered mesenchymal stem cells with Apoptin on hepatoma cells in vitro and in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 416 193–203. 10.1007/s11010-016-2707-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W. H., Cheng J. X., Shi P. F., Huang J. Y. (2011). Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells with adenovirus-mediated interleukin 12 gene transduction inhibits the growth of ovarian carcinoma cells both in vitro and in vivo. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao 31 903–907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y., Cheng M., Yang Z., Zeng C. Y., Chen J., Xie Y., et al. (2014). Mesenchymal stem cell-based NK4 gene therapy in nude mice bearing gastric cancer xenografts. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 8 2449–2462. 10.2147/DDDT.S71466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]