Abstract

In the calcium-activated photoprotein aequorin, light is produced by the oxidation of coelenterazine, the luciferin used by at least seven marine phyla. However, despite extensive research on photoproteins, there has been no evidence to indicate the origin of coelenterazine within the phylum Cnidaria. Here we report that the hydromedusa Aequorea victoria is unable to produce its own coelenterazine and is dependent on a dietary supply of this luciferin for bioluminescence. Although they contain functional apophotoproteins, medusae reared on a luciferin-free diet are unable to produce light unless provided with coelenterazine from an external source. This evidence regarding the origins of luciferin in Cnidaria has implications for the evolution of bioluminescence and for the extensive use of coelenterazine among marine organisms.

Bioluminescence of the hydromedusa Aequorea victoria has been studied more thoroughly than that of any other marine invertebrate. These jellyfish, readily collected from the waters of Puget Sound, Washington, have been the source of the first purified and cloned green-fluorescent protein, and the first calcium-regulated photoprotein. This photoprotein, aequorin, has been extensively studied since its discovery nearly 40 years ago (1, 2). It is a complex of an apoprotein joined with oxygen and a light-emitting luciferin called coelenterazine. Because they are triggered by Ca2+ ions to produce light, photoproteins have been widely used as calcium reporters (3–5). The high level of interest in these molecules has led to detailed studies of their chemistry and molecular biology: photoprotein genes have been cloned from several species of hydromedusae (6–10), and recently the tertiary structures of two photoproteins have been resolved (11, 12). If the gene for apoaequorin is introduced into an organism, however, no light will be emitted unless luciferin is provided exogenously. As a result, there is great interest in finding the pathways and genes responsible for the production of luciferin.

Photoproteins similar to aequorin have been found in ctenophores, radiolarians, and other hydromedusae. In addition, coelenterazine, the imidazolopyrazine luciferin of these photoprotein systems, is also used by fish, squid, some crustaceans, and a chaetognath (13–15) and is found in many nonluminous organisms as well (16, 17). Despite its occurrence in a variety of phyla, and recent interest in its antioxidative properties (18, 19), there has been little experimental evidence to indicate the origins of this light-emitting molecule in nature. There are two examples from crustacea: a dietary requirement for coelenterazine has been demonstrated for the lophogastrid shrimp Gnathophausia ingens (20), whereas the decapod shrimp Systellaspis debilis appears to have the ability to synthesize the molecule (21).

In some hydromedusae, including the genus Aequorea, a green-fluorescent protein (GFP) accepts energy from the photoprotein system and emits it as longer-wavelength light. In GFP, the chromophore is produced through the modification of a peptide precursor encoded within the gene (22), so that functional GFP can be made even in a heterologous system such as recombinant bacteria (23). It has been suggested that coelenterazine, the luciferin which is the chromophore of a photoprotein system, may be synthesized from a preprotein in a similar manner (22), but the hypothesized gene has never been found.

In a series of chemical and whole-organism experiments, we have examined the ability of A. victoria to produce coelenterazine.

Materials and Methods

Experiments were conducted on a unique population of Aequorea victoria that had been kept in culture through several generations at the Monterey Bay Aquarium, California. In nature, these medusae subsist mainly on gelatinous prey, but the cultured population was reared on a luciferin-free diet of the brine shrimp Artemia. Positive controls consisted of luminous, wild-caught medusae from waters off Friday Harbor, Washington, which was the original source of the cultured population. The observation that cultured medusae did not produce bioluminescence led to a series of experiments to determine the causes.

During whole-animal assays, light output was measured with a custom-built integrating sphere using a Hamamatsu HC-124 photomultiplier tube. Mechanical stimulation was accomplished by briefly and repeatedly pressing a small mesh manipulator against the upper bell of the medusa through a light-tight port. Medusae were stimulated no more than once per day, so that they would remain in good condition for subsequent trials. The values reported are relative measures of the total integrated light produced during a 20-sec stimulation period.

Apoproteins and calcium-activated photoproteins, when present, were extracted by homogenization of 0.5 ml of bell-margin tissue in 1.0 ml of 100 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.1/50 mM EDTA. Light output from aliquots was triggered by the addition of an equal volume of 200 mM CaCl2.

Apophotoprotein regeneration (charging of a spent inactive photoprotein by the addition of luciferin) was achieved by addition of synthesized coelenterazine (0.5 μg/μl in methanol) to extracts in the presence of 0.1% gelatin and 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol.

Natural feeding experiments were conducted by presenting individual medusae with portions of wild-caught ctenophores or hydromedusae. Prey included the nonluminous ctenophore Hormiphora californensis and the scyphomedusa Aurelia aurita. Luminous prey consisted of the hydromedusa Mitrocoma cellularia and the lobate ctenophore Bathocyroe fosteri. Two individual medusae were used in each feeding treatment, except in the case of Mitrocoma, which was fed to four A. victoria.

Experimental medusae were also fed Aurelia aurita that had been injected with coelenterazine, coelenteramide, or methanol alone. Scyphozoa used in feeding experiments and as negative controls in injection experiments had been reared in captivity on Artemia nauplii.

All results were consistent across treatments, and during each follow-up measurement over the weeks of experimentation. Because of differences in medusa size, sensitivity, and amounts ingested in feeding experiments, results should be interpreted for presence/absence of luminescence, rather than relative to each other.

Treatments involving direct injection into A. victoria consisted of injection with 5 μl of 0.1 μg/μl in methanol for coelenterazine, coelenteramide, and Cypridina-type luciferin. Substrates were injected into the tissue near the mouth or at the bell margin. Two medusae were subjected to each negative control, and six were used in the coelenterazine injection.

Results and Discussion

To study the origin of coelenterazine in Cnidaria, we examined a population of Aequorea victoria (Fig. 1) that had been cultured through several generations in captivity at the Monterey Bay Aquarium. Originally collected from the waters of Puget Sound, Washington, these hydrozoa were reared on a luciferin-free diet of enriched, cultured Artemia nauplii. In contrast to wild-collected A. victoria, the cultured medusae did not produce light during mechanical stimulation. Extracts in a Ca2+-chelating buffer did not produce light upon the addition of excess calcium, although extracts from wild-caught specimens did.

Figure 1.

The hydromedusa Aequorea victoria. In bioluminescent specimens, light is produced by photoproteins and associated green-fluorescent protein localized around the bell margin (not shown). The photograph, taken under white light, shows the medusa in its natural state, but does not show luminescence or fluorescence.

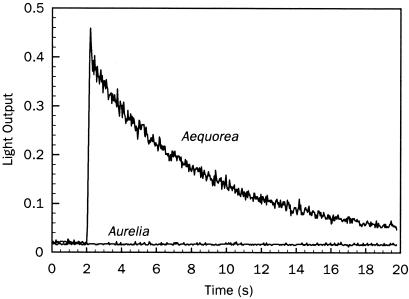

To determine whether the nonluminous medusae contained photoproteins that were functionally intact but lacked coelenterazine (i.e., “apophotoproteins”), we incubated extracts with coelenterazine, using extracts of the nonluminous scyphomedusa Aurelia aurita as a negative control. Luminescence was produced in regenerated extracts from A. victoria, but not from Aurelia aurita (Fig. 2), indicating that a functional apoprotein, lacking coelenterazine, was present in the cultured A. victoria.

Figure 2.

Regeneration of extracted apophotoprotein from nonluminous Aequorea victoria. Extracts incubated with coelenterazine produced light upon the addition of Ca2+. The negative control consisted of extracts of aquarium-reared, nonluminous scyphomedusa Aurelia aurita, from which protoprotein could not be regenerated.

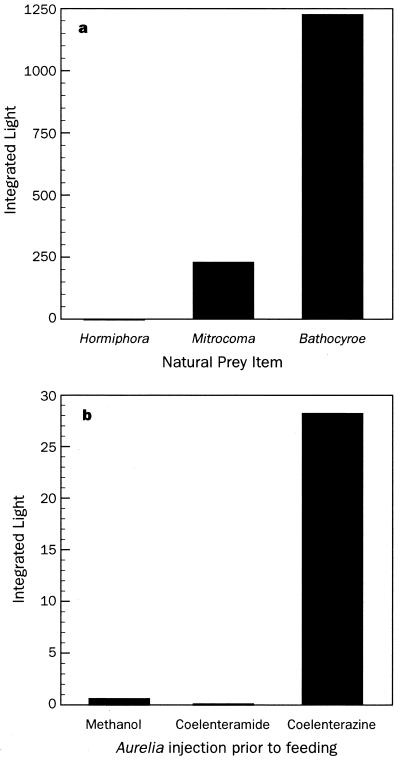

Nonluminous Aequorea were then fed a variety of wild-caught luminous and nonluminous prey to see whether luminescence could be induced through the diet. Consumption of the nonbioluminescent ctenophore Hormiphora californensis (24) did not initiate luminescence, but both the bioluminescent ctenophore Bathocyroe fosteri and pieces of the hydromedusa Mitrocoma cellularia did (Fig. 3a). Light was produced within 8 h of ingestion, and although it never reached the levels of wild-caught individuals, the ability to emit light persisted for more than 2 weeks on a single feeding, even after repeated stimulation.

Figure 3.

Induction of bioluminescence by feeding. (a) Feeding with natural prey induced luminescence only when the prey was originally bioluminescent, as with the hydromedusa Mitrocoma cellularia and the lobate ctenophore Bathocyroe fosteri. Nonluminous prey such as the cydippid ctenophore Hormiphora californensis did not cause nonluminous A. victoria to become bioluminescent. (b) A. victoria fed on the nonluminescent scyphomedusa Aurelia aurita became luminescent only if the prey had been injected with coelenterazine before feeding.

For a more specific test of whether coelenterazine itself or some other nutrient (25) was responsible for the onset of bioluminescence, nonluminous A. victoria were fed aquarium-reared Aurelia aurita that had been injected with methanol alone, coelenteramide (the oxidized, nonluminous form of coelenterazine), or coelenterazine in methanol. In all cases, only a diet that provided coelenterazine was able to impart luminescence. A similar requirement for exogenous luciferin (Cypridina-type, not coelenterazine) has been found in the midshipman fish, Porichthys notatus, which must ingest the ostracod Vargula to become luminescent (26). It also appears likely that euphausiid shrimp obtain their luciferin (dinoflagellate-type) by grazing on dinoflagellates (27).

Aequorea victoria eat other gelatinous plankton, and these prey in turn may also obtain coelenterazine through their diet, so while the ultimate source of the coelenterazine in hydromedusae remains unknown, we believe that crustaceans are the most likely sources. The transfer of coelenterazine also remains unresolved. In prey such as Mitrocoma cellularia, ≈97% of the coelenterazine is bound to a photoprotein (28), and at present it is unclear how (or whether) this coelenterazine is transferred intact to the photoprotein of A. victoria.

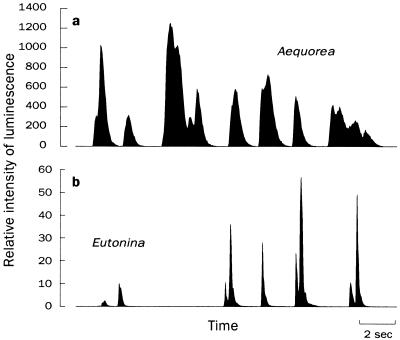

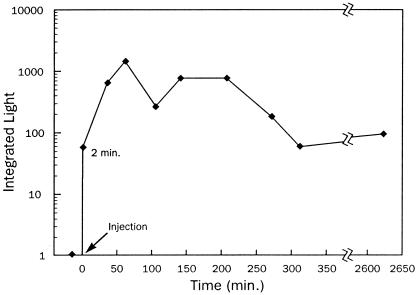

The most direct test of coelenterazine as the missing component in the luminescence system was the injection of coelenterazine, coelenteramide, or methanol into nonluminous A. victoria, again using Aurelia aurita as negative controls. As expected, only the coelenterazine injection was successful at inducing bioluminescence (Fig. 4a), and injection of coelenterazine into Aurelia aurita produced no light. The inefficacy of coelenteramide indicates that the medusae are unable to recycle coelenterazine once it is used. Therefore, to maintain bioluminescence, Aequorea must consume as much coelenterazine as it uses. The onset of bioluminescence in injected organisms was rapid: within 2 min, light production was detected, and luminescence increased to a stable level after ≈30 min (Fig. 5). Interestingly, bioluminescence was also induced by adding coelenterazine to the water in which A. victoria were being kept.

Figure 4.

Mechanical stimulation of medusae after direct injection. (a) Nonluminescent A. victoria became luminescent upon injection of coelenterazine, but not after equal treatments of methanol, coelenteramide, or Cypridina-type luciferin alone (not shown). Nonluminous Aurelia aurita did not produce light under any treatments. (b) Captive-reared Eutonina indicans produced flashes upon stimulation after direct injection with coelenterazine but not with Cypridina-type (ostracod) luciferin.

Figure 5.

Light production could be stimulated soon after injection of coelenterazine into nonluminous A. victoria and persisted for several days. Data show integrated light from periodic trials of an individual medusa.

Cultured nonluminous Aequorea, therefore, express apophotoprotein genes in the absence of coelenterazine. Fluorescence microscopy also showed that they contain functional green-fluorescent protein, so that both luminescence-related proteins are present even when they are not being used for bioluminescence.

Our results do not conflict with reports of bioluminescence in eggs and larvae of hydrozoa (4) and in ctenophore larvae (29). In these nonfeeding developing stages, there is likely to be a maternal transfer of bioluminescent substrates, including a sulfonated storage form of coelenterazine that is difficult to detect in chemical assays. Our findings also support the suggestion that bioluminescence has evolved relatively recently (30–32), possibly with arthropods rather than with early Cnidaria. Coupled with knowledge of the specialized diets of gelatinous organisms, these results may help explain the seemingly unpredictable (33) distribution of bioluminescence among species, as nonluminous species may not have ready access to luciferin-bearing prey.

While these experiments dealt with one species of hydromedusa, there are indications that the results may apply to other cnidarians as well. We were able to induce luminescence in a cultured population of the hydromedusa Eutonina indicans that had become nonluminous in captivity. The injection of coelenterazine brought on light production (Fig. 4b), but injection of methanol or Cypridina luciferin was ineffectual. Others have noted that the hydroid Obelia sp. has reduced luminescence when it is unable to feed (34). In addition, young medusae of the genera Bythotiara and Cunina, which are naturally bioluminescent (S.H.D.H, unpublished observations), are nonluminescent when reared on a diet of Artemia (K. A. Raskoff, personal communication). If this is indeed the case, and jellies are unable to synthesize their own luciferin, then the name “coelenterazine” itself may be a misnomer, as the only evidence for production of this molecule in the ocean comes from crustaceans.

Acknowledgments

J. F. Case provided the integrating sphere system, designed by C. Johnson, used in these studies. D. Wrobel and K. Cross of the Monterey Bay Aquarium maintained the cultures of Aurelia aurita and nonluminous A. victoria, which were initiated by Freya Sommer. C. E. Mills collected wild luminescent medusae from Friday Harbor, Washington. The crew of the research vessel Point Lobos and the remotely operated vehicle Ventana of the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute captured the medusae and ctenophores that were used as prey. Coelenterazine, synthesized by S. Inoue, coelenteramide, synthesized by Y. Kishi, and Cypridina luciferin were kindly provided by O. Shimomura. The manuscript was improved by the suggestions of two anonymous reviewers. Research was supported by the David and Lucile Packard Foundation.

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Shimomura O, Johnson F H, Saiga Y. J Cell Comp Physiol. 1962;59:223–239. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1030590302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shimomura O. Biol Bull. 1995;189:1–5. doi: 10.2307/1542194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell A K. Essays Biochem. 1989;24:41–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freeman G, Ridgway E B. Zool Sci. 1991;8:225–233. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell A K, Hallett M B, Daw R A, Ryall M E T, Hart R C, Herring P J. In: Bioluminescence and Chemiluminescence. DeLuca M A, McElroy W D, editors. New York: Academic; 1981. pp. 601–607. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prasher D C, McCann R O, Cormier M J. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1985;126:1259–1268. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(85)90321-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inouye S, Noguchi M, Sakaki Y, Takagi Y, Miyata T, Iwanaga S, Tsuji F I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:3154–3158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.10.3154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fagan T F, Ohmiya Y, Blinks J R, Inouye S, Tsuji F I. FEBS Lett. 1993;333:301–305. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80675-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Illarionov B A, Bondar V S, Illarionova V A, Vysotski E S. Gene. 1995;153:273–274. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)00797-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inouye S, Tsuji F I. FEBS Lett. 1993;315:343–346. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81191-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu Z-J, Vysotski E S, Chen C-J, Rose J P, Lee J, Wang B-C. Protein Sci. 2000;9:2085–2093. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.11.2085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Head J F, Inouye S, Teranishi K, Shimomura O. Nature (London) 2000;405:372–376. doi: 10.1038/35012659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell A K, Herring P J. Mar Biol. 1990;104:219–225. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shimomura O, Inoue S, Johnson F H, Haneda Y. Comp Biochem Physiol. 1980;65B:435–437. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haddock S H D, Case J F. Nature (London) 1994;367:225–226. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shimomura O. Comp Biochem Physiol. 1987;86B:361–363. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomson C M, Herring P J, Campbell A K. J Biolumin Chemilumin. 1997;12:87–91. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1271(199703/04)12:2<87::AID-BIO438>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rees J F, de Wergifosse B, Noiset O, Dubuisson M, Janssens B, Thompson E M. J Exp Biol. 1998;201:1211–1221. doi: 10.1242/jeb.201.8.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Devillers I, de Wergifosse B, Bruneau M P, Tinant B, Declercq J P, Touillaux R, Rees J F, Marchand-Brynaert J. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 2. 1999;7:1481–1487. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frank T M, Widder E A, Latz M I, Case J F. J Exp Biol. 1984;109:385–389. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomson C M, Herring P J, Campbell A K. J Mar Biol Assoc UK. 1995;75:165–171. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ward W W, Davis D F, Cutler M W. In: Bioluminescence and Chemiluminescence: Fundamentals and Applied Aspects. Campbell A K, Kricka L J, Stanley P E, editors. New York: Wiley; 1994. pp. 131–134. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chalfie M, Tu Y, Euskirchen G, Ward W W, Prasher D C. Science. 1994;263:802–805. doi: 10.1126/science.8303295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haddock S H D, Case J F. Biol Bull. 1995;189:356–362. doi: 10.2307/1542153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Båmstedt U, Ishii H, Martinussen M B. Sarsia. 1997;82:269–273. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsuji F I, Barnes A T, Case J F. Nature (London) 1972;237:515–516. doi: 10.1038/237515a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dunlap J, Shimomura O, Hastings J W. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:1394–1397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.3.1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shimomura O, Johnson F H. Comp Biochem Physiol. 1979;64B:105–107. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freeman G, Reynolds G T. Dev Biol. 1973;31:61–100. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(73)90321-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCapra F. In: Light and Life in the Sea. Herring P J, Campbell A K, Whitfield M, Maddock L, editors. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge Univ. Press; 1990. pp. 265–278. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hastings J W. Photochem Photobiol. 1995;62:599–600. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buck J B. In: Bioluminescence in Action. Herring P J, editor. London: Academic; 1978. pp. 419–460. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harvey E N. Bioluminescence. New York: Academic; 1952. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomson C M, Herring P J, Campbell A K. In: Bioluminescence and Chemiluminescence: Fundamentals and Applied Aspects. Campbell A K, Kricka L J, Stanley P E, editors. New York: Wiley; 1994. pp. 135–138. [Google Scholar]