Abstract

Background

This article about the emerging field of cardio-oncology highlights typical side effects of oncological therapies in the cardiovascular system, cardiovascular complications of malignancies itself, and potential preventive or therapeutic modalities.

Methods

We performed a selective literature search in PubMed until September 2016.

Results

Cardiovascular events in cancer patients can be frequently attributed to oncological therapies or to the underlying malignancy itself. Furthermore, many patients with cancer have pre-existing cardiovascular diseases that can be aggravated by the malignancy or its therapy. Cardiovascular abnormalities in oncological patients comprise a broad spectrum from alterations in electrophysiological, laboratory or imaging tests to the occurrence of thromboembolic, ischemic or rhythmological events and the impairment of left ventricular function or manifest heart failure.

Discussion

A close interdisciplinary collaboration between oncologists and cardiologists/angiologists as well as an increased awareness of potential cardiovascular complications could improve clinical care of cancer patients and provides a basis for an improved understanding of underlying mechanisms of cardiovascular morbidity.

Keywords: Cardiotoxicity, Side effects, Cardio-oncology, Onco-cardiology

Introduction

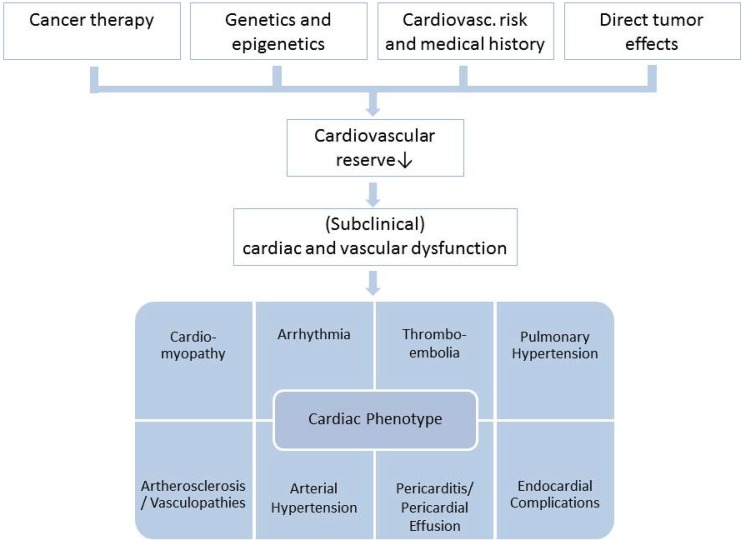

Scientific advances have led to a steady increase in survival rates of many oncologic entities within in the last decades. With more patients surviving their cancer, long-term side effects of oncologic therapies warrant consideration. In particular, cardiotoxic side effects following cancer therapy account for a relevant decrease in quality of life and mortality. On the other hand, a hasty withdrawal or de-escalation of oncologic therapy with the first appearance of cardiovascular side effects might worsen long-term prognosis. Combined chemotherapy or adjuvant radiotherapy can have synergistic or additive effects on the risk for cardiac complications and increase the cardiotoxic potential [1]. Cardiotoxicity of a certain therapy is difficult to predict for the individual patient as multiple factors contribute to an unknown extent (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Multifactorial cardiovascular risk model for the occurrence of cardiotoxic effects in oncologic patients

Patients with increased cardiovascular risk profiles are more prone to chemotherapy-associated cardiac dysfunction and deterioration of pre-existing cardiovascular diseases [2, 3]. However, even when adjusting for cardiovascular risk, there is still a high variability regarding the individual susceptibility to cardiotoxic effects. Subsequently, genetics and genotyping have gained more attention within the last decade [4, 5]. Aside from iatrogenic cardiotoxicity, there is also some evidence for the cancer itself affecting cardiac function and exercise performance, measured by peak oxygen consumption [6]. Accordingly, different preclinical models have described cancer-related myocardial atrophy, cardiac remodeling and cellular dysfunction, which are summarized as cardiac cachexia [7].

Distinguishing tumor associated or iatrogenic cardiotoxicity from inherent cardiac diseases is one of the tasks of the still young field of cardio-oncology. Further tasks include the interdisciplinary management of patients with cardiac tumors or metastases, myocardial, endocardial or pericardial complications, therapy-induced ischemia or arrhythmias, vascular complications, and venous thromboembolism. This review gives an overview of major cardiovascular implications of oncologic diseases and therapies.

Myocardial dysfunction

Myocardial dysfunction is a frequent complication of various oncologic therapies. Although there is no generally accepted definition of therapy-induced cardiotoxicity, echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) is still the most commonly used parameter to diagnose toxic cardiomyopathy [8, 9]. A symptomatic or asymptomatic decrease in LVEF of more than 10% to less than 50% is considered clinically relevant [10, 11]. In patients with symptoms or signs of heart failure but with preserved ejection fraction, echocardiographic assessment of diastolic function should be performed and natriuretic peptide should be measured [11]. Recent data do also suggest that strain and strain rate analysis might be important alone or in combination with biomarkers, to assess the individual course of cardiotoxicity in oncological patients [12].

In recent years, two distinct forms of cardiotoxicity have been described—a dose-dependent, cumulative, mostly irreversible form and a reversible, dose-independent type; see Table 1. The dose-independent type of cardiotoxicity is usually not associated with structural damage of cardiomyocytes, thus, chemotherapy can often be resumed after a short pause or in mild forms be continued [13, 14].

Table 1.

Characteristics of type-1 and type-2-cardiotoxicity.

Modified from [15]

| Drugs | Histopathology | Reversibility | Dose-dependency | Prognostic value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doxorubicin Daunorubicin Epirubicin Idarubicin Mitoxantrone Cyclophosphamide |

Apoptosis, necrosis-damaged sarcomeres | No (partially responsive to heart failure therapy) | Yes | Associated with increased mortality |

| Trastuzumab Sunitinib Lapatinib Imatinib |

Myocyte dysfunction | Yes (in most cases) | No | Not associated with increased mortality |

This classification might facilitate therapeutic decisions, but has limitations when it comes to the individual patient’s prognosis regarding cardiac function. In addition, chemotherapeutic drugs are often applied as combination therapies or are administered sequentially. Thus, the interaction of diverse toxic effects makes it difficult to distinguish between different pathomechanisms.

The best-known example of cardiotoxicity is anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy. Similar effects, however, have also been shown for other chemotherapeutic agents like cyclophosphamide [16]. Anthracyclines may infrequently cause acute, dose-independent, and reversible cardiac dysfunction directly following infusion, which is to be distinguished from dose-dependent chronic cardiomyopathy. Reactive oxygen species and oxidative stress seem to play an important role in its pathomechanism leading to a decrease in myocardial mass, cardiac remodeling and ultimately cardiac dysfunction [17, 18]. Approximately 5% of patients treated with a cumulative dose of 400–450 mg/m2 doxorubicin develop heart failure; the proportion increases to 10% in elderly patients [19, 20]. Once a cumulative dose of more than 300 mg/m2 doxorubicin has been administered, the addition of dexrazoxane can be considered to decrease toxicity [17, 21]. However, a general recommendation for dexrazoxane cannot be given as it might decrease the efficacy of anthracycline therapy. Other cardioprotective measures include the usage of liposomal formulas and prolonged infusions (more than 30 min). However, a potential decrease in efficacy is also assumed for these measures.

Heart failure therapy in oncologic patients follows the same principles as in other patients and has shown some reversibility even in chronic anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy when initiated early [22]. In contrast, preventive heart failure therapy accompanying chemotherapy or radiation in the absence of heart failure is discussed controversially [23–25]. There might be, however, beneficial effects in high-risk populations, namely, patients undergoing high-dose chemotherapy with anthracyclines [26, 27]. Accordingly, current recommendations consider a preventive cardioprotective therapy for patients at high-risk cardiac complications [10].

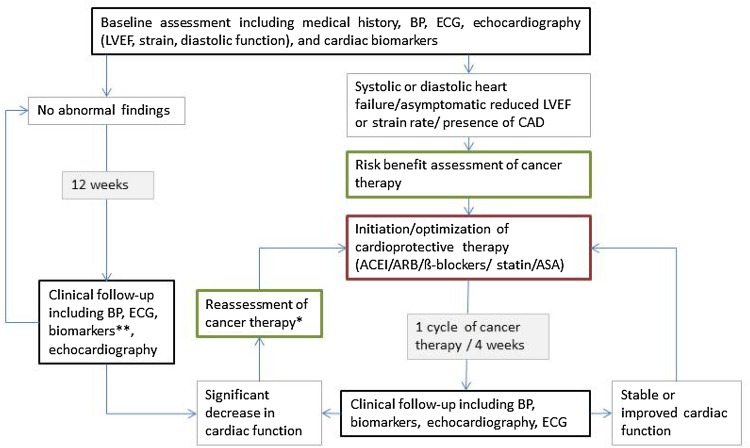

In order to monitor patients with pre-existing cardiac dysfunction as well as to identify patients with an increased cardiac risk, echocardiography, ECG, and measurement of biomarkers such as natriuretic peptide (BNP or nt-proBNP) or (high-sensitive) troponin are recommended (Fig. 2). The value of routine measurements of cardiac biomarkers to monitor asymptomatic patients without any pre-existing cardiac conditions is still uncertain as the clinical significance of minor changes is yet to be elucidated. With this in mind, cardiac biomarkers can still be useful to track minor subclinical changes in cardiac function, which might influence decisions on oncologic treatment strategies or preventive measures [10].

Fig. 2.

Cardiac monitoring of patients during potentially cardiotoxic cancer therapy. *Reassessment with discontinuation of cardiotoxic therapy vs. dose reduction vs. change of chemotherapeutic drug vs. unmodified continuation of oncologic treatment. **Optional. BP blood pressure measurement, ECG electrocardiogram, LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction, ACEI angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, ARB angiotensin receptor blockers, ASA acetylsalicylic acid

Venous thromboembolism

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a frequent complication in cancer patients. The risk for VTE is 4–7 times increased in cancer patients compared to persons without malignancy [28]. The risk for VTE depends on the type of malignancy, the stage of disease, the oncologic treatment, and patient-specific factors (Table 2). Suspected VTE in cancer patients is usually clarified by diagnostic imaging, i.e., compression ultrasound for deep vein thrombosis, and CT-angiography for pulmonary embolism, respectively [29]. d-dimers are often unspecifically increased and should not be used to rule out VTE in cancer patients [29]. Low molecular heparins (LMH) are first-line therapy during the first 3–6 months after diagnosis and are usually followed by long-term anticoagulation as long as the cancer is active [29]. This also applies to catheter-associated intravenous thrombosis as long as the catheter is functional, in use, and shows no signs of bacterial infection.

Table 2.

Thromboembolic risk factors in oncologic patients

| Risk | Description |

|---|---|

| Individual risk | Age [30] Positive anamnesis or family history for VTE [31] Hereditary thrombophilia (e.g., factor-V-Leiden mutation) [32] Life style (obesity, lack of physical exercise, smoking) [30, 33] Oral contraceptive therapy Ethnicity (increased risk in Afro-Americans) [34] |

| Risk of tumor entity and stage | Tumor entity (high risk with pancreatic, gastric, renal, lung or ovarian cancer as well as lymphoma and malign brain tumors) [30, 32–34] Metastasized disease stage [30, 32, 34] First 3–6 months following diagnosis [32, 34] Thrombocytosis before initiation of chemotherapy [33] Increased inflammatory markers Increased d-dimers |

| Oncologic therapy | Surgery [35] Radiation Chemotherapy [28, 31] Hormone therapy [36] Immune therapy Antiangiogenic therapy [37, 38] |

| Other risk factors | Blood transfusions Drugs stimulating erythropoiesis (e.g., erythropoietin) [33] Central venous catheter (e.g., port systems) [39] Immobilization, hospitalization [30, 31] Dehydration due to vomiting or diarrhea |

An increased incidence of VTE has been described for cisplatin, bevacizumab (angiogenesis inhibitor), tamoxifen (selective estrogen receptor blocker), and sunitinib and sorafenib (tyrosine kinase inhibitors) [36–38, 40]. Routine prophylactic anticoagulation, however, is not recommended in cancer patients, even when the above-mentioned drugs are administered [29, 41]. Aside from the lack of clinical data, the increased risk for major bleedings and the comparatively low incidence of VTEs in an outpatient setting support this recommendation [42]. In contrast, the benefit of a prolonged thrombosis prophylaxis following major abdominal or pelvic tumor surgery is well-described [35]. Furthermore, patients suffering from multiple myeloma and who are treated with lenalidomide or thalidomide should routinely receive anticoagulation therapy [41, 43, 44]. Prophylactic therapy is also recommended for hospitalized cancer patients with active disease [41]. Other situations (e.g., bed-ridden patients) need individual decisions.

Endocardial complications/endocarditis

Thrombotic endocarditis

Thrombotic endocarditis (TE) is a form of non-bacterial endocarditis affecting mainly patients with advanced cancer stages [45]. Often patients remain asymptomatic as long as no arterial embolization occurs. Distinguishing TE form infectious endocarditis (IE) can be challenging. A disseminated embolic distribution pattern and low inflammatory markers are indicative of TE [46]. TE is also likely if echocardiographic criteria of endocarditis are met but blood cultures remain negative or if there is no clinical response to antibiotic therapy. Other causes of blood culture-negative endocarditis should be ruled out. Vegetations are most commonly located to left ventricular valves, specifically at the ventricular side of the aortic valve and atrial side of the mitral valve [47]. Surgical therapy is rarely needed. Besides treating the underlying disease, systemic anticoagulation therapy is indicated to prevent thromboembolic complications [48, 49].

Infectious endocarditis

Intravascular foreign bodies (e.g., catheter-systems) as well as an altered immune response enable the development of IE in cancer patients. Due to a lack of data regarding the incidence of IE in cancer patients, IE prophylaxis, diagnosis, and therapy follows the same guidelines as in other patients with IE [50]. Every diagnosed catheter-associated infection in combination with at least one positive peripheral blood culture should be considered for further evaluation by transthoracic echocardiography (TTE), and transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) if indicated. Lack of adequate clinical response (e.g., persistent fever or persistent positive blood cultures) or the presence of additional risk factors (e.g., artificial heart valves, pace-maker or implantable cardioverter defibrillator) warrant echocardiographic evaluation.

As cancer patients are prone to IE, IE might also be the first complication of undiagnosed cancer. IE is associated with an increased risk for cancer, in particular hematologic or intraabdominal malignancies [51]. For example, due to a strong association with colorectal cancer, guidelines recommend to perform a colonoscopy if S. bovis or S. gallolyticus has been detected in blood cultures [50].

Hedinger’s syndrome

Paraneoplastic processes might also favor valvulopathy. Patients suffering from certain types of neuroendocrine tumors, carcinoids, gradually develop right ventricular endocardial fibrosis. This paraneoplastic process eventually leads to Hedinger’s syndrome which is characterized by a degeneration and restriction of the tricuspid and pulmonary valve. Therapy focuses primarily on the treatment of the underlying disease [52]. The valvulopathy and subsequent right ventricular failure is treated primarily with diuretics and in some cases with surgical valve replacement [53].

Pericardial complications

A newly diagnosed pericardial effusion might represent the first sign of an underlying malignancy. Cytological analysis of the pericardial effusion and peri-/epicardial biopsies should be pursued [54–56]. Almost 2/3 of pericardial effusions in cancer patients, however, are not caused by direct tumor infiltration, but are due to paraneoplastic processes, former radiation, or due to an opportunistic infection [56]. If cardiac tamponade is imminent, pericardiocentesis should be performed promptly. Pericardial effusions often re-occur in these patients and are difficult to manage. Radiotherapy might likely lead to a reduction of the associated pericardial effusion in the presence of radiation sensitive tumors. However, radiotherapy itself is also associated with pericardial effusion although the use of modern protocols has reduced its occurrence [57]. Pericardial fenestration might provide symptomatic control with frequently recurring pericardial effusions [54, 58]. In some cases, intrapericardial application of cytostatic or sclerosing agents might represent the only feasible therapy [54, 56, 59, 60]. As pericardial involvement often implies a palliative stage, control of symptoms and improving quality of life should be the primary focus of any therapy.

Arterial hypertension

Arterial hypertension has been associated with various chemotherapeutic agents [61]. Drugs modifying the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) pathway frequently increase systemic blood pressure [62]. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors are also associated with an increase in systemic blood pressure, which occurs often as early as a few hours after initiation of treatment [62]. A disturbance in endothelial function and alterations on the capillary level are likely pathomechanisms linked to this effect [63]. Patients receiving chemotherapeutic agents associated with arterial hypertension should be screened on a weekly basis for arterial hypertension during the first cycle [61]. The interval can be prolonged to 2 or 3 weeks in time [61]. Discontinuation of the chemotherapeutic drug should be considered in patients with a hypertensive crisis or a persistent systolic blood pressure over 180 mmHg despite adequate antihypertensive therapy [61]. In general, blood pressure therapy in cancer patients follows the same principles as in other patients with the exception that diuretics should be used with particular caution because of potential electrolyte impairments in cancer patients. In addition, drug interactions require particular care in choosing the most appropriate antihypertensive therapy as some chemotherapeutic and antihypertensive drugs share the same metabolic pathways.

Arteriosclerosis and complications

Atherosclerotic processes usually evolve over several years before symptoms occur. This latency might contribute to the fact that the effect of chemotherapeutic agents on blood vessels is still not well understood. Furthermore, cancer and atherosclerosis share the most potent risk factor: smoking [64]. The co-prevalence of different cancers and clinical manifestations of atherosclerosis complicates the distinction between toxic side effects of chemotherapy and pre-existing cardiovascular risk. However, for some chemotherapeutic agents, such as cisplatin, bleomycin, and etoposide, an increased long-term risk for cardiovascular and atherosclerotic complications has been confirmed [65, 66]. These long-term effects have to be distinguished from acute vascular events caused by arterial thrombosis, which might lead to thrombotic occlusion of coronary vessels in the absence of coronary artery disease [67]. Substances such as 5-FU and capecitabine, or paclitaxel, gemcitabine, rituximab, and sorafenib have been linked to vascular spasm and Raynaud phenomenon, angina pectoris, and even myocardial infarction [68–70].

While more clinical research is needed to understand long-term arterial complications of chemotherapy, long-term effects of radiotherapy on blood vessels is comparatively well studied. Inflammatory processes lead to atherosclerotic lesions in irradiated vessels [71]. Patients with pre-existing coronary artery disease or a high cardiovascular risk profile are particularly prone to cardiovascular events following radiation [71]. Accordingly, adults that underwent radiotherapy of the chest during childhood have a significantly elevated risk for myocardial infarction, even in the absence of other cardiovascular risk factors [72, 73]. Radiation of the head and neck increases the cerebrovascular event rate and radiation of the pelvis might trigger the development of peripheral artery disease [74]. Apart from a few exceptions, there are no differences with regard to therapy and secondary prophylaxis when compared to non-irradiated patients [75]. As an example, carotid artery stenting might be preferred over carotid endarterectomy in patients with prior radical neck dissection and radiation therapy who require treatment for carotid stenosis, because of an increased rate of wound complications and kidney failure in patients undergoing surgery [76].

Pulmonary hypertension

The exact prevalence of pulmonary hypertension (PH) in cancer patients is unknown. Initial, mostly exercise-induced symptoms such as dyspnea, fatigue, dizziness, and infrequently angina are unspecific. In addition to chronic thrombembolia, PH is frequently caused by drug-induced chemotoxicity. Especially alkylating agents (e.g., cyclophosphamide) have been associated with PH. Furthermore, radiotherapy of the chest has been associated with veno-occlusive PH. Most often, however, the development of PH in cancer patients has a multifactorial etiology. Post-capillary PH due to left ventricular dysfunction should be distinguished from pulmonary tissue disease or chronic thromboembolic PH as treatment and prognosis vary. Diagnostic workup should take into account the patient’s individual prognosis [77]. Echocardiography often provides the first clues for the presence of PH. To diagnose PH and distinguish post-capillary from other forms of PH, right heart catheterization should be performed. In the presence of right heart failure and volume overload, diuretics provide symptomatic relieve. PH therapy depends on the underlying processes and should follow current guidelines [77]. However, adaptations might be necessary due to altered life expectancy and drug interactions.

Arrhythmias

As more attention is paid to cardiotoxic side effects, more and more oncologic treatment regimens are being linked to a wide variety of electrophysiological changes and arrhythmias [78]. Although associated with an increased overall long-term mortality, arrhythmias related to chemotherapy are mostly transient and not life-threatening [79]. The diagnostic workup should include a 12 lead ECG, Holter monitoring, echocardiography and a laboratory workup with serum electrolytes and renal function tests.

Chemotherapy-induced arrhythmia has been documented for anthracyclines, taxanes, and cyclophosphamide. A short infusion duration of anthracyclines increases the likelihood for transient supraventricular arrhythmia and ventricular premature beats (VPB) following administration [80]. Taxane therapy might lead to sinus bradycardia and first-degree atrioventricular block in some patients, which usually do not require any further therapy [81]. Up to 10% of all patients receiving high-dose cyclophosphamide develop supraventricular or ventricular arrhythmia within the first 3 days after administration [78, 82]. Patients with perimyocarditis or other chemotoxic side effects are at increased risk [78, 82].

In addition, many chemotherapeutic drugs can lead to QT-prolongation. Chemotoxic side effects like diarrhea or vomiting as well as antiemetic drugs and psychotropic medication can enhance QT-prolongation [82]. Susceptibility to torsades de pointes tachycardia with potential conversion to ventricular fibrillation depends on the chemotherapeutic drug used [83–85]. Therefore, there is no general recommendation concerning a QTc-interval, at which chemotherapy should be suspended [85].

While the above-mentioned transient arrhythmias are mostly direct side effects and resolve when chemotherapy is suspended, chronic or recurrent arrhythmias are often due to structural myocardial damage caused by chemotherapeutic agents (e.g., anthracyclines) [80]. Myocardial scarring of the cardiac conduction system caused by chest radiotherapy leads to atrioventricular blocks [86, 87]. Rarely, myocardial tumor infiltration or pericardial metastasis might be the cause of arrhythmia, which are usually associated with a poor prognosis and should be treated symptomatically.

Beside arrhythmias, recent data indicate that resting heart rate alone could serve as a predictive marker for patients with colorectal, pancreatic, and non-small cell lung cancer [88].

Conclusion

The challenge of cardio-oncology is getting the right diagnosis from merely unspecific symptoms in order to balance the urgent and often life-saving oncologic therapy against cardiotoxic side effects limiting quality of life and long-term survival. Thus, a close collaboration between oncologists/hematologists and cardiologists is crucial. Cancer patients should, therefore, be seen by a cardiologist before, during and after a potentially cardiotoxic chemotherapy. Further research is needed to improve our understanding of cancer-related cardiovascular risks and to develop parameters for a better cardiovascular risk stratification of cancer patients.

Contributor Information

Lorenz H. Lehmann, Phone: +49 6221 5638448, Email: Lorenz.Lehmann@med.uni-heidelberg.de

Oliver J. Müller, Phone: +49 431 500-22950, Email: Oliver.Mueller@uksh.de

References

- 1.Schlitt A, Jordan K, Vordermark D, Schwamborn J, Langer T, Thomssen C. Cardiotoxicity and oncological treatments. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2014;111(10):161–168. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2014.0161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kravchenko J, Berry M, Arbeev K, Kim Lyerly H, Yashin A, Akushevich I. Cardiovascular comorbidities and survival of lung cancer patients: medicare data based analysis. Lung Cancer. 2015;88(1):85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hershman DL, McBride RB, Eisenberger A, Tsai WY, Grann VR, Jacobson JS. Doxorubicin, cardiac risk factors, and cardiac toxicity in elderly patients with diffuse B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(19):3159–3165. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deng S, Wojnowski L. Genotyping the risk of anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2007;7(2):129–134. doi: 10.1007/s12012-007-0024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhatia S. Role of genetic susceptibility in development of treatment-related adverse outcomes in cancer survivors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2011;20(10):2048–2067. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cramer L, Hildebrandt B, Kung T, Wichmann K, Springer J, Doehner W, Sandek A, Valentova M, Stojakovic T, Scharnagl H, Riess H, Anker SD, von Haehling S. Cardiovascular function and predictors of exercise capacity in patients with colorectal cancer. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(13):1310–1319. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.07.948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy KT. The pathogenesis and treatment of cardiac atrophy in cancer cachexia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2016;310(4):H466–H477. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00720.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aleman BM, Moser EC, Nuver J, Suter TM, Maraldo MV, Specht L, Vrieling C, Darby SC. Cardiovascular disease after cancer therapy. EJC Suppl. 2014;12(1):18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcsup.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin M, Esteva FJ, Alba E, Khandheria B, Perez-Isla L, Garcia-Saenz JA, Marquez A, Sengupta P, Zamorano J. Minimizing cardiotoxicity while optimizing treatment efficacy with trastuzumab: review and expert recommendations. Oncologist. 2009;14(1):1–11. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zamorano JL, Lancellotti P, Rodriguez Munoz D, Aboyans V, Asteggiano R, Galderisi M, Habib G, Lenihan DJ, Lip GY, Lyon AR, Lopez Fernandez T, Mohty D, Piepoli MF, Tamargo J, Torbicki A, Suter TM, Authors/Task Force M, Guidelines ESCCfP 2016 ESC Position Paper on cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity developed under the auspices of the ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines: the task force for cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JG, Coats AJ, Falk V, Gonzalez-Juanatey JR, Harjola VP, Jankowska EA, Jessup M, Linde C, Nihoyannopoulos P, Parissis JT, Pieske B, Riley JP, Rosano GM, Ruilope LM, Ruschitzka F, Rutten FH, van der Meer P. 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2016;69(12):1167. doi: 10.1016/j.recesp.2016.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thavendiranathan P, Poulin F, Lim KD, Plana JC, Woo A, Marwick TH. Use of myocardial strain imaging by echocardiography for the early detection of cardiotoxicity in patients during and after cancer chemotherapy: a systematic review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 Pt A):2751–2768. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.01.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ewer MS, Lippman SM. Type II chemotherapy-related cardiac dysfunction: time to recognize a new entity. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(13):2900–2902. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keefe DL. Trastuzumab-associated cardiotoxicity. Cancer. 2002;95(7):1592–1600. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ewer MS, Ewer SM. Cardiotoxicity of anticancer treatments: What the cardiologist needs to know. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2010;7(10):564–575. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2010.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dhesi S, Chu MP, Blevins G, Paterson I, Larratt L, Oudit GY, Kim DH. Cyclophosphamide-induced cardiomyopathy: a case report, review, and recommendations for management. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2013;1(1):2324709613480346. doi: 10.1177/2324709613480346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wouters KA, Kremer LC, Miller TL, Herman EH, Lipshultz SE. Protecting against anthracycline-induced myocardial damage: a review of the most promising strategies. Br J Haematol. 2005;131(5):561–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Minotti G, Cairo G, Monti E. Role of iron in anthracycline cardiotoxicity: new tunes for an old song? FASEB J. 1999;13(2):199–212. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wojnowski L, Kulle B, Schirmer M, Schluter G, Schmidt A, Rosenberger A, Vonhof S, Bickeboller H, Toliat MR, Suk EK, Tzvetkov M, Kruger A, Seifert S, Kloess M, Hahn H, Loeffler M, Nurnberg P, Pfreundschuh M, Trumper L, Brockmoller J, Hasenfuss G. NAD(P)H oxidase and multidrug resistance protein genetic polymorphisms are associated with doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Circulation. 2005;112(24):3754–3762. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.576850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swain SM, Whaley FS, Ewer MS. Congestive heart failure in patients treated with doxorubicin—a retrospective analysis of three trials. Cancer. 2003;97(11):2869–2879. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hensley ML, Hagerty KL, Kewalramani T, Green DM, Meropol NJ, Wasserman TH, Cohen GI, Emami B, Gradishar WJ, Mitchell RB, Thigpen JT, Trotti A, 3rd, von Hoff D, Schuchter LM. American Society of Clinical Oncology 2008 clinical practice guideline update: use of chemotherapy and radiation therapy protectants. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(1):127–145. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.2627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cardinale D, Colombo A, Bacchiani G, Tedeschi I, Meroni CA, Veglia F, Civelli M, Lamantia G, Colombo N, Curigliano G, Fiorentini C, Cipolla CM. Early detection of anthracycline cardiotoxicity and improvement with heart failure therapy. Circulation. 2015;131(22):1981–1988. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Georgakopoulos P, Roussou P, Matsakas E, Karavidas A, Anagnostopoulos N, Marinakis T, Galanopoulos A, Georgiakodis F, Zimeras S, Kyriakidis M, Ahimastos A. Cardioprotective effect of metoprolol and enalapril in doxorubicin-treated lymphoma patients: a prospective, parallel-group, randomized, controlled study with 36-month follow-up. Am J Hematol. 2010;85(11):894–896. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bosch X, Rovira M, Sitges M, Domenech A, Ortiz-Perez JT, de Caralt TM, Morales-Ruiz M, Perea RJ, Monzo M, Esteve J. Enalapril and carvedilol for preventing chemotherapy-induced left ventricular systolic dysfunction in patients with malignant hemopathies: the OVERCOME trial (preventiOn of left Ventricular dysfunction with Enalapril and caRvedilol in patients submitted to intensive ChemOtherapy for the treatment of Malignant hEmopathies) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(23):2355–2362. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.02.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dessi M, Madeddu C, Piras A, Cadeddu C, Antoni G, Mercuro G, Mantovani G. Long-term, up to 18 months, protective effects of the angiotensin II receptor blocker telmisartan on Epirubin-induced inflammation and oxidative stress assessed by serial strain rate. Springerplus. 2013;2(1):198. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-2-198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yun S, Vincelette ND, Abraham I. Cardioprotective role of beta-blockers and angiotensin antagonists in early-onset anthracyclines-induced cardiotoxicity in adult patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Postgrad Med J. 2015;91(1081):627–633. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2015-133535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gulati G, Heck SL, Ree AH, Hoffmann P, Schulz-Menger J, Fagerland MW, Gravdehaug B, von Knobelsdorff-Brenkenhoff F, Bratland A, Storas TH, Hagve TA, Rosjo H, Steine K, Geisler J, Omland T. Prevention of cardiac dysfunction during adjuvant breast cancer therapy (PRADA): a 2×2 factorial, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial of candesartan and metoprolol. Eur Heart J. 2016 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heit JA, Silverstein MD, Mohr DN, Petterson TM, O’Fallon WM, Melton LJ., 3rd Risk factors for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a population-based case-control study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(6):809–815. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.6.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.S2-Leitlinie: Diagnostik und Therapie der Venenthrombose und der Lungenembolie (2015)

- 30.Khorana AA, Francis CW, Culakova E, Fisher RI, Kuderer NM, Lyman GH. Thromboembolism in hospitalized neutropenic cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(3):484–490. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.8877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kroger K, Weiland D, Ose C, Neumann N, Weiss S, Hirsch C, Urbanski K, Seeber S, Scheulen ME. Risk factors for venous thromboembolic events in cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2006;17(2):297–303. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdj068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blom JW, Doggen CJ, Osanto S, Rosendaal FR. Malignancies, prothrombotic mutations, and the risk of venous thrombosis. JAMA. 2005;293(6):715–722. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.6.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khorana AA, Francis CW, Culakova E, Lyman GH. Risk factors for chemotherapy-associated venous thromboembolism in a prospective observational study. Cancer. 2005;104(12):2822–2829. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chew HK, Wun T, Harvey D, Zhou H, White RH. Incidence of venous thromboembolism and its effect on survival among patients with common cancers. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(4):458–464. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.4.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bergqvist D, Agnelli G, Cohen AT, Eldor A, Nilsson PE, Le Moigne-Amrani A, Dietrich-Neto F, Investigators EI. Duration of prophylaxis against venous thromboembolism with enoxaparin after surgery for cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(13):975–980. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petrelli F, Cabiddu M, Borgonovo K, Barni S. Risk of venous and arterial thromboembolic events associated with anti-EGFR agents: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(7):1672–1679. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choueiri TK, Schutz FA, Je Y, Rosenberg JE, Bellmunt J. Risk of arterial thromboembolic events with sunitinib and sorafenib: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(13):2280–2285. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.2757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nalluri SR, Chu D, Keresztes R, Zhu X, Wu S. Risk of venous thromboembolism with the angiogenesis inhibitor bevacizumab in cancer patients: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300(19):2277–2285. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cortelezzi A, Moia M, Falanga A, Pogliani EM, Agnelli G, Bonizzoni E, Gussoni G, Barbui T, Mannucci PM, Group CS. Incidence of thrombotic complications in patients with haematological malignancies with central venous catheters: a prospective multicentre study. Br J Haematol. 2005;129(6):811–817. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moore RA, Adel N, Riedel E, Bhutani M, Feldman DR, Tabbara NE, Soff G, Parameswaran R, Hassoun H. High incidence of thromboembolic events in patients treated with cisplatin-based chemotherapy: a large retrospective analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(25):3466–3473. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.5669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lyman GH, Khorana AA, Falanga A, Clarke-Pearson D, Flowers C, Jahanzeb M, Kakkar A, Kuderer NM, Levine MN, Liebman H, Mendelson D, Raskob G, Somerfield MR, Thodiyil P, Trent D, Francis CW, American Society of Clinical O American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline: recommendations for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis and treatment in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(34):5490–5505. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haas SK, Freund M, Heigener D, Heilmann L, Kemkes-Matthes B, von Tempelhoff GF, Melzer N, Kakkar AK, Investigators T. Low-molecular-weight heparin versus placebo for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in metastatic breast cancer or stage III/IV lung cancer. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2012;18(2):159–165. doi: 10.1177/1076029611433769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bennett CL, Angelotta C, Yarnold PR, Evens AM, Zonder JA, Raisch DW, Richardson P. Thalidomide- and lenalidomide-associated thromboembolism among patients with cancer. JAMA. 2006;296(21):2558–2560. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.21.2558-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zangari M, Anaissie E, Barlogie B, Badros A, Desikan R, Gopal AV, Morris C, Toor A, Siegel E, Fink L, Tricot G. Increased risk of deep-vein thrombosis in patients with multiple myeloma receiving thalidomide and chemotherapy. Blood. 2001;98(5):1614–1615. doi: 10.1182/blood.V98.5.1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.el-Shami K, Griffiths E, Streiff M. Nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis in cancer patients: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Oncologist. 2007;12(5):518–523. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-5-518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Singhal AB, Topcuoglu MA, Buonanno FS. Acute ischemic stroke patterns in infective and nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis: a diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging study. Stroke. 2002;33(5):1267–1273. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000015029.91577.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reagan TJ, Okazaki H. The thrombotic syndrome associated with carcinoma. A clinical and neuropathologic study. Arch Neurol. 1974;31(6):390–395. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1974.00490420056006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rogers LR, Cho ES, Kempin S, Posner JB. Cerebral infarction from non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis. Clinical and pathological study including the effects of anticoagulation. Am J Med. 1987;83(4):746–756. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90908-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lopez JA, Ross RS, Fishbein MC, Siegel RJ. Nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis: a review. Am Heart J. 1987;113(3):773–784. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(87)90719-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Habib G, Lancellotti P, Antunes MJ, Bongiorni MG, Casalta JP, Del Zotti F, Dulgheru R, El Khoury G, Erba PA, Iung B, Miro JM, Mulder BJ, Plonska-Gosciniak E, Price S, Roos-Hesselink J, Snygg-Martin U, Thuny F, Tornos Mas P, Vilacosta I, Zamorano JL, Document R, Erol C, Nihoyannopoulos P, Aboyans V, Agewall S, Athanassopoulos G, Aytekin S, Benzer W, Bueno H, Broekhuizen L, Carerj S, Cosyns B, De Backer J, De Bonis M, Dimopoulos K, Donal E, Drexel H, Flachskampf FA, Hall R, Halvorsen S, Hoen B, Kirchhof P, Lainscak M, Leite-Moreira AF, Lip GY, Mestres CA, Piepoli MF, Punjabi PP, Rapezzi C, Rosenhek R, Siebens K, Tamargo J, Walker DM. 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: the task force for the management of infective endocarditis of the european society of cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: European association for cardio-thoracic surgery (EACTS), the European association of nuclear medicine (EANM) Eur Heart J. 2015;36(44):3075–3128. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thomsen RW, Farkas DK, Friis S, Svaerke C, Ording AG, Norgaard M, Sorensen HT. Endocarditis and risk of cancer: a Danish nationwide cohort study. Am J Med. 2013;126(1):58–67. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shen C, Shih YC, Xu Y, Yao JC. Octreotide long-acting repeatable use among elderly patients with carcinoid syndrome and survival outcomes: a population-based analysis. Cancer. 2014;120(13):2039–2049. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Connolly HM, Schaff HV, Abel MD, Rubin J, Askew JW, Li Z, Inda JJ, Luis SA, Nishimura RA, Pellikka PA. Early and late outcomes of surgical treatment in carcinoid heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(20):2189–2196. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Adler Y, Charron P. The 2015 ESC Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(42):2873–2874. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maisch B, Ristic A, Pankuweit S. Evaluation and management of pericardial effusion in patients with neoplastic disease. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2010;53(2):157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vaitkus PT, Herrmann HC, LeWinter MM. Treatment of malignant pericardial effusion. JAMA. 1994;272(1):59–64. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03520010071035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stewart JR, Fajardo LF, Gillette SM, Constine LS. Radiation injury to the heart. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31(5):1205–1211. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)00656-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, Badano L, Baron-Esquivias G, Bogaert J, Brucato A, Gueret P, Klingel K, Lionis C, Maisch B, Mayosi B, Pavie A, Ristic AD, Sabate Tenas M, Seferovic P, Swedberg K, Tomkowski W, Achenbach S, Agewall S, Al-Attar N, Angel Ferrer J, Arad M, Asteggiano R, Bueno H, Caforio AL, Carerj S, Ceconi C, Evangelista A, Flachskampf F, Giannakoulas G, Gielen S, Habib G, Kolh P, Lambrinou E, Lancellotti P, Lazaros G, Linhart A, Meurin P, Nieman K, Piepoli MF, Price S, Roos-Hesselink J, Roubille F, Ruschitzka F, Sagrista Sauleda J, Sousa-Uva M, Uwe Voigt J, Luis Zamorano J, European Society of C 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Pericardial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Endorsed by: The European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) Eur Heart J. 2015;36(42):2921–2964. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bishiniotis TS, Antoniadou S, Katseas G, Mouratidou D, Litos AG, Balamoutsos N. Malignant cardiac tamponade in women with breast cancer treated by pericardiocentesis and intrapericardial administration of triethylenethiophosphoramide (thiotepa) Am J Cardiol. 2000;86(3):362–364. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(00)00937-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kunitoh H, Tamura T, Shibata T, Imai M, Nishiwaki Y, Nishio M, Yokoyama A, Watanabe K, Noda K, Saijo N, Jcog Lung Cancer Study Group TJ A randomised trial of intrapericardial bleomycin for malignant pericardial effusion with lung cancer (JCOG9811) Br J Cancer. 2009;100(3):464–469. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Herrmann J, Yang EH, Iliescu CA, Cilingiroglu M, Charitakis K, Hakeem A, Toutouzas K, Leesar MA, Grines CL, Marmagkiolis K. Vascular toxicities of cancer therapies: the old and the new—an evolving avenue. Circulation. 2016;133(13):1272–1289. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Izzedine H, Ederhy S, Goldwasser F, Soria JC, Milano G, Cohen A, Khayat D, Spano JP. Management of hypertension in angiogenesis inhibitor-treated patients. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(5):807–815. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Small HY, Montezano AC, Rios FJ, Savoia C, Touyz RM. Hypertension due to antiangiogenic cancer therapy with vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors: understanding and managing a new syndrome. Can J Cardiol. 2014;30(5):534–543. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hansen ES. International Commission for Protection Against Environmental Mutagens and Carcinogens. ICPEMC Working Paper 7/1/2. Shared risk factors for cancer and atherosclerosis—a review of the epidemiological evidence. Mutat Res. 1990;239(3):163–179. doi: 10.1016/0165-1110(90)90004-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Haugnes HS, Wethal T, Aass N, Dahl O, Klepp O, Langberg CW, Wilsgaard T, Bremnes RM, Fossa SD. Cardiovascular risk factors and morbidity in long-term survivors of testicular cancer: a 20-year follow-up study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(30):4649–4657. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.9362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Meinardi MT, Gietema JA, van der Graaf WT, van Veldhuisen DJ, Runne MA, Sluiter WJ, de Vries EG, Willemse PB, Mulder NH, van den Berg MP, Koops HS, Sleijfer DT. Cardiovascular morbidity in long-term survivors of metastatic testicular cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(8):1725–1732. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.8.1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Samuels BL, Vogelzang NJ, Kennedy BJ. Severe vascular toxicity associated with vinblastine, bleomycin, and cisplatin chemotherapy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1987;19(3):253–256. doi: 10.1007/BF00252982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Arima Y, Oshima S, Noda K, Fukushima H, Taniguchi I, Nakamura S, Shono M, Ogawa H. Sorafenib-induced acute myocardial infarction due to coronary artery spasm. J Cardiol. 2009;54(3):512–515. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gemici G, Cincin A, Degertekin M, Oktay A. Paclitaxel-induced ST-segment elevations. Clin Cardiol. 2009;32(6):E94–E96. doi: 10.1002/clc.20291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shah K, Gupta S, Ghosh J, Bajpai J, Maheshwari A. Acute non-ST elevation myocardial infarction following paclitaxel administration for ovarian carcinoma: a case report and review of literature. J Cancer Res Ther. 2012;8(3):442–444. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.103530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Darby SC, Ewertz M, Hall P. Ischemic heart disease after breast cancer radiotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(26):2527. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1305687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Castellino SM, Geiger AM, Mertens AC, Leisenring WM, Tooze JA, Goodman P, Stovall M, Robison LL, Hudson MM. Morbidity and mortality in long-term survivors of Hodgkin lymphoma: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Blood. 2011;117(6):1806–1816. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-278796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Swerdlow AJ, Higgins CD, Smith P, Cunningham D, Hancock BW, Horwich A, Hoskin PJ, Lister A, Radford JA, Rohatiner AZ, Linch DC. Myocardial infarction mortality risk after treatment for Hodgkin disease: a collaborative British cohort study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(3):206–214. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cheng SW, Ting AC, Ho P, Wu LL. Accelerated progression of carotid stenosis in patients with previous external neck irradiation. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39(2):409–415. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2003.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.AWMF (Stand: 08.08.2012) S3-Leitlinie zur Diagnostik, Therapie und Nachsorge der extracraniellen Carotisstenose

- 76.Tallarita T, Oderich GS, Lanzino G, Cloft H, Kallmes D, Bower TC, Duncan AA, Gloviczki P. Outcomes of carotid artery stenting versus historical surgical controls for radiation-induced carotid stenosis. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53(3):629–636. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Galie N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL, Gibbs S, Lang I, Torbicki A, Simonneau G, Peacock A, Vonk Noordegraaf A, Beghetti M, Ghofrani A, Gomez Sanchez MA, Hansmann G, Klepetko W, Lancellotti P, Matucci M, McDonagh T, Pierard LA, Trindade PT, Zompatori M, Hoeper M, Aboyans V, Vaz Carneiro A, Achenbach S, Agewall S, Allanore Y, Asteggiano R, Paolo Badano L, Albert Barbera J, Bouvaist H, Bueno H, Byrne RA, Carerj S, Castro G, Erol C, Falk V, Funck-Brentano C, Gorenflo M, Granton J, Iung B, Kiely DG, Kirchhof P, Kjellstrom B, Landmesser U, Lekakis J, Lionis C, Lip GY, Orfanos SE, Park MH, Piepoli MF, Ponikowski P, Revel MP, Rigau D, Rosenkranz S, Voller H, Luis Zamorano J. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) Eur Heart J. 2016;37(1):67–119. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tamargo J, Caballero R, Delpon E. Cancer chemotherapy and cardiac arrhythmias: a review. Drug Saf. 2015;38(2):129–152. doi: 10.1007/s40264-014-0258-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jurczak W, Szmit S, Sobocinski M, Machaczka M, Drozd-Sokolowska J, Joks M, Dzietczenia J, Wrobel T, Kumiega B, Zaucha JM, Knopinska-Posluszny W, Spychalowicz W, Prochwicz A, Drohomirecka A, Skotnicki AB. Premature cardiovascular mortality in lymphoma patients treated with (R)-CHOP regimen—a national multicenter study. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168(6):5212–5217. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kilickap S, Barista I, Akgul E, Aytemir K, Aksoy S, Tekuzman G. Early and late arrhythmogenic effects of doxorubicin. South Med J. 2007;100(3):262–265. doi: 10.1097/01.smj.0000257382.89910.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Arbuck SG, Strauss H, Rowinsky E, Christian M, Suffness M, Adams J, Oakes M, McGuire W, Reed E, Gibbs H et al. (1993) A reassessment of cardiac toxicity associated with Taxol. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr (15):117–130 [PubMed]

- 82.Ando M, Yokozawa T, Sawada J, Takaue Y, Togitani K, Kawahigashi N, Narabayashi M, Takeyama K, Tanosaki R, Mineishi S, Kobayashi Y, Watanabe T, Adachi I, Tobinai K. Cardiac conduction abnormalities in patients with breast cancer undergoing high-dose chemotherapy and stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2000;25(2):185–189. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Barbey JT, Pezzullo JC, Soignet SL. Effect of arsenic trioxide on QT interval in patients with advanced malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(19):3609–3615. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Westervelt P, Brown RA, Adkins DR, Khoury H, Curtin P, Hurd D, Luger SM, Ma MK, Ley TJ, DiPersio JF. Sudden death among patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia treated with arsenic trioxide. Blood. 2001;98(2):266–271. doi: 10.1182/blood.V98.2.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kantarjian H, Giles F, Wunderle L, Bhalla K, O’Brien S, Wassmann B, Tanaka C, Manley P, Rae P, Mietlowski W, Bochinski K, Hochhaus A, Griffin JD, Hoelzer D, Albitar M, Dugan M, Cortes J, Alland L, Ottmann OG. Nilotinib in imatinib-resistant CML and Philadelphia chromosome-positive ALL. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(24):2542–2551. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Larsen RL, Jakacki RI, Vetter VL, Meadows AT, Silber JH, Barber G. Electrocardiographic changes and arrhythmias after cancer therapy in children and young adults. Am J Cardiol. 1992;70(1):73–77. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(92)91393-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jaworski C, Mariani JA, Wheeler G, Kaye DM. Cardiac complications of thoracic irradiation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(23):2319–2328. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.01.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Anker MS, Ebner N, Hildebrandt B, Springer J, Sinn M, Riess H, Anker SD, Landmesser U, Haverkamp W, von Haehling S. Resting heart rate is an independent predictor of death in patients with colorectal, pancreatic, and non-small cell lung cancer: results of a prospective cardiovascular long-term study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18(12):1524–1534. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]